Opening Vignette

A 56-year-old woman with underlying hypertension was referred from the polyclinic for sinus tachycardia and acute-onset breathlessness of 1 day duration. She also reported a near-syncopal episode earlier. Vital signs were as follows: temperature 36.5°C, blood pressure (BP) 86/50 mmHg, pulse rate 138 beats/min, respiratory rate 40 breaths/min and peripheral oxygen saturation 80% on room air. You administered fluid boluses and oxygen therapy via a 35% venturi mask. On examination, the patient was alert but tachypnoeic with accessory muscle usage. Breath sounds were normal, and there was no calf tenderness or swelling. The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus tachycardia, and the chest X-ray did not show any consolidation or effusion. Ten minutes later, the patient’s BP dropped to 65/40 despite the fluid boluses.

DEFINITION AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a form of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and refers to the occlusion of the pulmonary artery or one of its branches by thrombus. Most frequently, it arises from a dislodged thrombus in the proximal veins of the lower extremities that migrate to the pulmonary arterial bed. Virchow’s triad describes the three factors contributing to the development of venous thrombosis: venous stasis, endothelial injury and hypercoagulability. Pulmonary embolism may be provoked by risk factors such as surgery, immobilisation and cancer, or may be seemingly unprovoked (30%–50%).[1]

Occlusion of the pulmonary vascular bed may result in ventilation–perfusion mismatch and increased pulmonary vascular resistance in the presence of a high thrombus burden. Increased pulmonary vascular resistance impairs right ventricular (RV) outflow, causing progressive RV dilatation and leftward bowing of the interventricular septum. Consequently, RV failure and impaired left ventricular filling ensue, resulting in reduced cardiac output, systemic hypotension and myocardial ischaemia due to inadequate coronary artery filling. This vicious cycle of RV failure eventually leads to circulatory collapse and death in patients with high-risk PE. Left untreated, mortality rates in these patients can be as high as 20%–59%.[2]

APPROACH TO SUSPECTED PULMONARY EMBOLISM

History and presentation

Pulmonary embolism should be suspected in a patient presenting with acute dyspnoea, chest pain, syncope or haemoptysis. The attending physician should check for risk factors such as recent surgery requiring general anaesthesia, lower extremity fractures, immobility, active malignancy, history of previous unprovoked VTE, long-haul flights and use of oral contraceptive pills in females. Clinical examination may reveal tachypnoea, hypoxaemia, haemodynamic instability or lower extremity swelling suspicious for deep venous thrombosis (DVT). An estimated 70% of patients with PE have concomitant DVT.[3] The ECG findings vary; it may be normal or may show arrhythmias (sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, atrial premature contractions), signs of RV strain (T-wave inversion in leads V1–V3, QR pattern in V1, S1Q3T3, right bundle branch block) and non-specific ST segment or T-wave changes. The following ECG changes predict RV dysfunction to varying degrees. T-wave inversion in leads V1–V3 is the most reliable, with a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 88%. Findings of S1Q3T3 and right bundle branch block, with a sensitivity of 35% and 30%, respectively, and a specificity of 90% and 83%, respectively, strongly suggest RV dysfunction, although their absence does not exclude it.[4] Chest X-ray findings are usually non-specific, revealing atelectasis, pleural effusions and/or parenchymal areas of increased opacity in the lower lung fields, but they may also be normal. Chest X-ray is usually more helpful in excluding other differential diagnoses, rather than confirming the diagnosis of PE. Findings specific for PE include the Hampton hump (well-defined pleural-based opacity with a convex medial border; sensitivity 22% and specificity 82%), Westermark sign (regional oligaemia; sensitivity 14% and specificity 92%) and Fleischner sign (prominent pulmonary artery; sensitivity 20% and specificity 80%),[5] but these are rarely seen.

Clinical prediction scores such as revised Geneva’s [Table 1][6] and Wells’ [Table 2][7] scores can aid in assessing the clinical probability of PE. In those with a low clinical probability of PE, the use of Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria[8] may obviate the need for further diagnostic tests.

Table 1.

Revised Geneva’s score.a

| Variable | Points |

|---|---|

| Age >65 years | 1 |

|

| |

| Previous deep venous thrombosis or PE | 3 |

|

| |

| Surgery or fracture within 1 month | 2 |

|

| |

| Active malignancy | 2 |

|

| |

| Unilateral lower limb pain | 3 |

|

| |

| Haemoptysis | 2 |

|

| |

| Heart rate 75–94/min | 3 |

|

| |

| Heart rate ≥95/min | 5 |

|

| |

| Pain on lower limb deep venous palpation and unilateral oedema | 4 |

aAdapted from Le Gal, et al.[6] Clinical probability of pulmonary embolism (PE): low: 0–3 points; intermediate: 4–10 points; and high: ≥11 points.

Table 2.

Well’s score.a

| Variable | Points |

|---|---|

| Previous deep venous thrombosis or PE | 1.5 |

|

| |

| Recent surgery/immobilisation | 1.5 |

|

| |

| Cancer | 1.0 |

|

| |

| Haemoptysis | 1.0 |

|

| |

| Heart rate >100/min | 1.5 |

|

| |

| Clinical signs of deep venous thrombosis | 3.0 |

|

| |

| Alternative diagnosis other than PE | 3.0 |

aAdapted from Wells, et al.[7] Clinical probability of pulmonary embolism (PE): low: 0–1 point; intermediate: 2–6 points; and high: ≥7 points.

Diagnostic evaluation

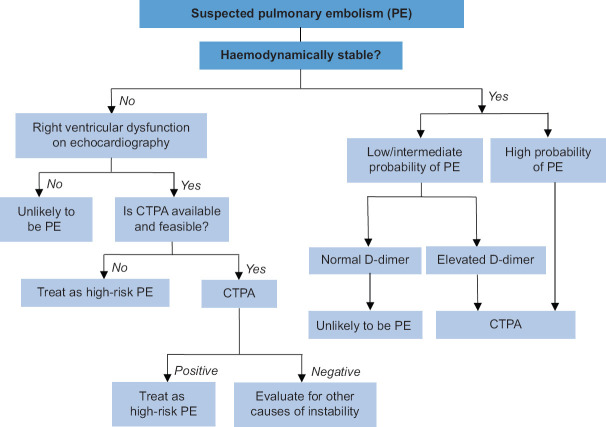

Diagnostic evaluation of suspected PE depends on the clinical pretest probability of PE, presence of haemodynamic instability as well as contraindications to various diagnostic modalities. A proposed diagnostic approach is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Approach to acute management of pulmonary embolism. Adapted and modified from Konstantinides, et al.[9] CTPA: computed tomography pulmonary angiogram

D-dimer test

A D-dimer test can help clinicians decide whether to perform a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) in patients with a low or intermediate probability of PE. A normal age-adjusted D-dimer level,[10] with a cut-off value <500 mcg/L for patients aged ≤50 years and a cut-off value <(age × 10) mcg/L for patients aged >50 years, can confidently rule out PE and eliminate the need for a CTPA due to its high negative predictive value. Those with positive D-dimer tests should proceed with a CTPA.

Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram

The imaging of choice in the diagnosis of PE is CTPA, with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 96%.[11] In the absence of PE, CTPA may provide an alternative diagnosis. Limitations include radiation exposure and the need for contrast. It is contraindicated in patients with severe renal failure and contrast allergy. It may be considered for use in pregnancy, although the use of other modalities without radiation should be considered first in consultation with the patient.

Lung ventilation perfusion scan

The lung ventilation perfusion (V/Q) scan utilises radiolabelled agents in aerosol and injectable forms to produce lung ventilation and perfusion studies, identifying areas of V/Q mismatch. Areas of PE show up as perfusion defects in areas of normal ventilation. It has a sensitivity of 77.4% and specificity of 97.7% when compared to CTPA,[12] and may be an alternative for those with contraindications to CTPA.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography may be the only investigative modality suitable for haemodynamically unstable patients who cannot be safely transported for computed tomography. The absence of RV overload on bedside echocardiography almost certainly rules out PE as the cause of hypotension. Conversely, the presence of RV dysfunction on echocardiography may be sufficient to initiate immediate reperfusion treatment in those with a high clinical suspicion of PE.[9] Other echocardiographic findings specific for PE are mobile right heart thrombi, McConnell sign (akinesis of the RV free wall with sparing of the apex) or ‘60/60’ sign (pulmonary acceleration time <60 ms and peak systolic tricuspid valve gradient <60 mmHg).[13]

Compression ultrasonography

Compression ultrasonography has a sensitivity of >90% and a specificity of 95% for proximal symptomatic DVT.[14] In patients who are contraindicated for CTPA, the presence of proximal DVT can serve as a surrogate for the diagnosis of PE without further testing, although absence of DVT does not exclude PE.

Risk stratification

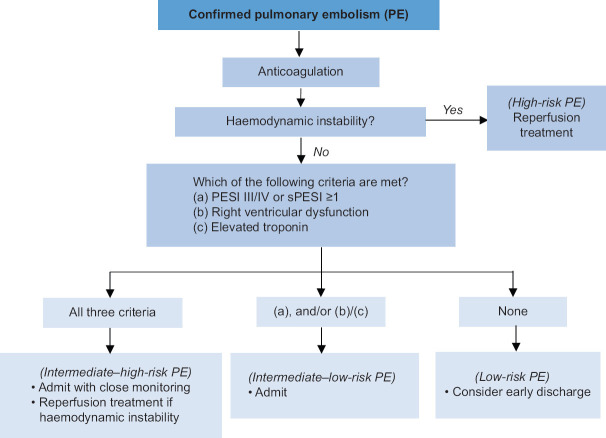

Once the diagnosis of PE is established, risk stratification is crucial to determine prognosis and guide initial management [Figure 2]. Pulmonary embolism can be risk stratified into high-, intermediate- and low-risk PE.

Figure 2.

Approach to acute management of pulmonary embolism. Adapted and modified from Konstantinides, et al.[9] PESI: Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index, sPESI: simplified PESI

High-risk PE is defined by the presence of haemodynamic instability. Haemodynamic instability is defined as (a) cardiac arrest or (b) persistent hypotension (systolic BP [SBP] <90 mmHg or SBP drop ≥40 mmHg for >15 min, not explained by arrhythmia, hypovolaemia or sepsis). Immediate reperfusion therapy is indicated, as the mortality risk is high in this group of patients.

Intermediate-risk PE is defined as having Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) class III–V[15] or simplified PESI ≥I and/or serious comorbidity. The PESI score has been extensively validated to assess overall mortality by incorporating PE severity and comorbidities. PESI class I and II have been reliable in identifying those at low risk for 30-day mortality. Patients with PESI class III–IV, concomitant RV dysfunction on echocardiography or CTPA, and elevated troponin markers are classified as having intermediate–high-risk PE. Patients with normal right ventricle on imaging and/or normal troponin levels are classified as having intermediate–low-risk PE. Those with intermediate–high-risk PE require close monitoring, as they are at risk of subsequent haemodynamic deterioration, but do not otherwise require immediate reperfusion therapy.

Low-risk PE is the absence of the aforementioned features. These patients can be considered for early discharge with anticoagulation therapy, which is as safe and effective as inpatient treatment.[16]

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT

Management of PE can be divided into acute and long-term considerations. Acute management involves resuscitation and stabilisation of the patient as well as PE-specific therapy; long-term management involves assessing the future risk of VTE recurrence, as well as ongoing bleeding risks, to guide the duration of anticoagulation. A summary of anticoagulation options is outlined in Table 3. Consultation with a multidisciplinary PE response team for patients with high-risk PE and certain groups of patients with intermediate-risk PE has been shown to improve patient outcomes.[17]

Table 3.

Anticoagulation options for pulmonary embolism.

| Example | Dose | Therapeutic target |

|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated heparin | Bolus: 80 units/kga Initial infusion rate: 18 units/kg/ha |

aPTT 1.5–2.5 times the control |

|

| ||

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BD | Not applicable |

|

| ||

| Direct oral anticoagulants | Dabigatran: 150 mg BD Apixaban: 10 mg BD for 1 week, then 5 mg BD Rivaroxaban: 15 mg BD for 3 weeks; then 20 mg OD |

Not applicable |

|

| ||

| Warfarin | Initial dose: 5 mg OD on days 1 and 2 Reduced doseb: 2.5 mg daily |

INR 2.0–3.0 |

aUsing total body weight. bConsider reduced dose in the elderly (age >70–80 years), those who are malnourished or those with history of liver or kidney disease, heart failure or on concomitant medications that increase warfarin sensitivity. aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, BD: twice daily, INR: international normalised ratio, OD: once daily

Acute management

Haemodynamic management

In patients with hypotension, careful assessment of volume status is crucial to avoid excessive fluid administration, which may worsen RV overload with resultant decrease in cardiac output. Care should also be taken to minimise RV afterload by ensuring adequate oxygenation and minimising airway pressures in ventilated patients. Patients who remain persistently hypotensive despite adequate filling status require the use of vasopressors such as noradrenaline to maintain tissue perfusion.[18] In patients with refractory hypotension or cardiac arrest, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in combination with reperfusion therapy should be considered.

Hypoxaemia management

Use of supplemental oxygen may be required to maintain an oxygen saturation of ≥90%. In some cases, escalation to high-flow nasal cannula therapy[19] or invasive mechanical ventilation is necessary. Ultimately, definitive correction of hypoxaemia requires pulmonary reperfusion therapy. Intubation and mechanical ventilation are especially challenging due to the risk of severe hypotension during induction and positive pressure ventilation. Sedative agents with less haemodynamic effects and cautious application of positive end-expiratory pressure should be considered.

Pulmonary embolism-specific treatment

Reperfusion treatment is indicated for those with high-risk PE and may be achieved via pharmacological (thrombolysis) or mechanical (thrombectomy) means. Pharmacological reperfusion involves administering thrombolytics to dissolve blood clots in the pulmonary artery, thereby restoring circulation and improving haemodynamics. Systemic thrombolysis is the first-line therapy for patients with high-risk PE without contraindications.

Mechanical thrombectomy is performed via a catheter-based or surgical approach. It is employed in cases where systemic thrombolysis is contraindicated or has failed. Catheter-based mechanical reperfusion, performed by interventional radiologists, involves the insertion of a catheter via the femoral vein into the pulmonary artery for thrombus fragmentation or aspiration; reduced-dose thrombolysis may also be concomitantly administered locally via the catheter. Surgical embolectomy is usually carried out with cardiopulmonary bypass for patients with or without cardiac arrest.

All patients with acute PE should receive anticoagulation unless contraindicated. Unfractionated heparin is usually preferred in patients with high-risk PE after reperfusion therapy, while low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is usually used in patients with intermediate–high-risk PE. Once patients are stable, they may be transitioned to oral anticoagulation agents. Oral agents are often first-line therapy in those with low-risk PE. Inferior vena cava filters are only indicated in those who are unable to receive anticoagulation.

Long-term management

Direct oral anticoagulants are the long-term anticoagulation of choice over warfarin due to their reduced bleeding risk with similar efficacy outcomes.[20] They are contraindicated in pregnancy as well as in those with severe renal impairment or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Patients initiated on warfarin should be overlapped with parenteral anticoagulation until the international normalised ratio value is stable at 2.0–3.0 for two consecutive days.

The duration of anticoagulation depends on the individual’s risk for VTE recurrence. Patients with first-onset PE secondary to a major transient risk factor require anticoagulation for 3 months. For those with weak, persistent or no identifiable risk factors, the decision on whether to extend anticoagulation beyond 3 months requires a balanced assessment of bleeding risk and risk of VTE recurrence. In certain population groups, screening for acquired or hereditary thrombophilia and occult malignancy may be appropriate.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

Clinical prediction scores, such as revised Geneva’s and Wells’ scores, can aid in assessing the clinical probability of PE.

Bedside echocardiography to evaluate for RV dysfunction is useful in haemodynamically unstable patients with suspected PE. The absence of RV overload almost certainly rules out PE as a cause for haemodynamic instability.

For haemodynamically stable patients with suspected PE, CTPA should be performed for these patients: (a) low or intermediate probability of PE with elevated D-dimer levels, and (b) high probability of PE.

High-risk PE is defined as PE with haemodynamic instability. Patients with this condition require urgent reperfusion therapy; systemic thrombolysis is the modality of choice.

The duration of anticoagulation after PE depends on the presence of risk factors, which influence the risk of VTE recurrence, as well as ongoing bleeding risks.

Closing Vignette

Further history was elicited after the patient was stabilised. Her chronic medications include amlodipine 10 mg and losartan 50 mg taken every morning. She did not undergo any recent surgery. There is no personal history of malignancy. A bedside echocardiography showed RV dysfunction. You inserted a central line and started noradrenaline for the patient and sent her for a CTPA when her haemodynamics stabilised. The CTPA revealed PE in bilateral main pulmonary arteries and a 5-cm right upper lobe lung mass. You administered thrombolysis with intravenous (IV) recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rTPA) — 10 mg bolus followed by remaining 90 mg dose infused over 2 h. Her noradrenaline requirements gradually reduced from 0.5 to 0.2 mcg/kg/min within a few hours of administration of rTPA. She was admitted to the intensive care unit for monitoring and commenced on IV unfractionated heparin. The next morning, her noradrenaline was weaned off and she was switched to subcutaneous LMWH injections. She was transferred to the general ward on day 2 of admission. Compression ultrasonography did not reveal any lower limb DVT. Contrast CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis revealed metastatic lung cancer. A transthoracic needle aspiration of the right lung mass was performed after withholding LMWH for 12 h. She was switched to rivaroxaban the next day (15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks followed by 20 mg once daily). She continued to remain haemodynamically stable in the general ward and was subsequently discharged in a stable condition on day 10 of admission with medical oncology and vascular medicine follow-up appointments.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

SMC CATEGORY 3B CME PROGRAMME

Online Quiz: https://www.sma.org.sg/cme-programme

Deadline for submission: 6 pm, 04 October 2024

| Question: Answer True or False |

|---|

| 1. The following is not a component of Virchow’s triad: |

|

|

| (a) Hypercoagulability. |

|

|

| (b) Cytokine release. |

|

|

| (c) Endothelial injury. |

|

|

| (d) Venous stasis. |

|

|

| 2. The following is a symptom of pulmonary embolism (PE): |

|

|

| (a) Cough. |

|

|

| (b) Hemiparesis. |

|

|

| (c) Syncope. |

|

|

| (d) Numbness. |

|

|

| 3. Regarding the diagnosis of PE: |

|

|

| (a) Lung ventilation perfusion (V/Q) scans can be considered for patients who are too haemodynamically unstable to be transported for computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA). |

|

|

| (b) The presence of a blood clot in the anterior tibial vein is sufficient as a surrogate diagnosis for PE if CTPA cannot be performed. |

|

|

| (c) In a patient with low suspicion of PE, a CTPA should be performed despite a normal D-dimer. |

|

|

| (d) The absence of right ventricular (RV) overload almost certainly rules out PE as the cause of hypotension in the presence of haemodynamic instability. |

|

|

| 4. High-risk PE is defined as the presence of: |

|

|

| (a) Elevated troponin. |

|

|

| (b) Oxygen desaturation. |

|

|

| (c) Right ventricular dysfunction. |

|

|

| (d) Hypotension. |

|

|

| 5. Regarding the treatment of PE: |

|

|

| (a) Excessive fluid resuscitation in hypotensive patients may worsen their blood pressure. |

|

|

| (b) Patients with low oxygen saturation should be immediately intubated. |

|

|

| (c) Patients with high-risk PE who are contraindicated for thrombolysis can be considered for surgical or catheter-based thrombectomy. |

|

|

| (d) The definitive treatment for hypoxaemia involves pulmonary reperfusion therapy. |

REFERENCES

- 1.Kearon C, Ageno W, Cannegieters SC, Cosmi B, Geersing GJ, Kyrle PA, et al. Categorization of patients as having provoked or unprovoked VTE: Guidance from the SSC of ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:1480–3. doi: 10.1111/jth.13336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, Arcelus JI, Bergqvist D, Brecht JG, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:756–64. doi: 10.1160/TH07-03-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearon C. Natural history of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107:I22–30. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078464.82671.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Punukollu G, Gowda RM, Vasavada BC, Khan IA. Role of electrocardiography in identifying right ventricular dysfunction in acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:450–2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worsley DF, Alavi A, Aronchick JM, Chen JT, Greenspan RH, Ravin CE. Chest radiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: Observations from the PIOPED Study. Radiology. 1993;189:133–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.1.8372182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy P-M, Sanchez O, Aujesky D, Bounameaux H, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: The revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: Increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Fitterman N, Schuur JD, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: Best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:701–11. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, Bueno H, Geersing GJ, Harjola VP, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douma RA, le Gal G, Sohne M, Righini M, Kamphuisen PW, Perrier A, et al. Potential of an age adjusted D-dimer cut-off value to improve the exclusion of pulmonary embolism in older patients: A retrospective analysis of three large cohorts. BMJ. 2010;340:c1475. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sostman HD, Stein PD, Gottschalk A, Matta F, Hull R, Goodman L, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism: Sensitivity and specificity of ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy in PIOPED II study. Radiology. 2008;246:941–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463070270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurzyna M, Torbicki A, Pruszczyk P, Burakowska B, Fijałkowska A, Kober J, et al. Disturbed right ventricular ejection pattern as a new Doppler echocardiographic sign of acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:507–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Hirsh J. The role of venous ultrasonography in the diagnosis of suspected deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1044–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aujesky D, Obrosky DS, Stone RA, Auble TE, Perrier A, Cornuz J, et al. Derivation and validation of a prognostic model for pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1041–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-862OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aujesky D, Roy P-M, Verschuren F, Righini M, Osterwalder J, Egloff M, et al. Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: An international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:41–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleitas Sosa D, Lehr AL, Zhao H, Roth S, Lakhther V, Bashir R, et al. Impact of pulmonary embolism response teams on acute pulmonary embolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31:220023. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0023-2022. doi:10.1183/16000617.0023-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harjola VP, Mebazaa A, Celutkiene J, Bettex D, Bueno H, Chioncel O, et al. Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: A statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:226–41. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messika J, Goutorbe P, Hajage D, Ricard JD. Severe pulmonary embolism managed with high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy. Eur J Emerg Med. 2017;24:230–2. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middeldorp S, Buller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: Evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood. 2014;124:1968–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]