Abstract

Little is known about the assembly pathway and structure of hepatitis C virus (HCV) since insufficient quantities of purified virus are available for detailed biophysical and structural studies. Here, we show that bacterially expressed HCV core proteins can efficiently self-assemble in vitro into nucleocapsid-like particles. These particles have a regular, spherical morphology with a modal distribution of diameters of approximately 60 nm. Self-assembly of nucleocapsid-like particles requires structured RNA molecules. The 124 N-terminal residues of the core protein are sufficient for self-assembly into nucleocapsid-like particles. Inclusion of the carboxy-terminal domain of the core protein modifies the core assembly pathway such that the resultant particles have an irregular outline. However, these particles are similar in size and shape to those assembled from the 124 N-terminal residues of the core protein. These results provide novel opportunities to delineate protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions critical for HCV assembly, to study the molecular details of HCV assembly, and for performing high-throughput screening of assembly inhibitors.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis and has been shown to be a causative agent in hepatocellular carcinoma. With nearly 3% of the world's population infected with HCV, this disease has emerged as a serious global health problem since the virus was first identified in 1989 (10). HCV is an enveloped single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus of the Flaviviridae family. The ∼9.6-kb viral genome is flanked by untranslated regions (UTRs) at its 5′ and 3′ ends and encodes a ∼3,000-amino-acid polypeptide (11, 14). This polyprotein is posttranslationally cleaved by host cellular peptidases to yield HCV core and E1 and E2 structural proteins, while viral proteases cleave the HCV polyprotein to generate the five HCV nonstructural proteins (15, 19). The initial polyprotein cleavage generates P23, an immature core protein of 191 amino acids, which then undergoes additional processing to yield P21 (15, 17, 19). The role of these core proteins in HCV replication and assembly is largely unknown. The C terminus of P21 has been reported to occur between residues 172 and 182 (22, 26, 35, 36, 43). Both P23 and P21 core proteins have been reported in all HCV strains examined (in some early citations, P23 and P21 core products have been termed P21 and P19, respectively), and an additional cleavage yielding a 16-kDa product has also been found in HCV genotype 1 (HCV-1) (26). Expression studies in mammalian cells indicated that P21 is the major core product formed (26, 35). Core protein isolated from infectious sera corresponds to P21, suggesting that P21 is the mature core protein present in viral particles (43).

The HCV core protein appears to be multifunctional, having been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis, lipid metabolism, transcription, immune presentation, and cell transformation (30). Sequence comparisons between the highly basic HCV core protein and related flavivirus proteins suggest that the core protein also functions to encapsidate the viral genome within a nucleocapsid particle (24). The HCV core protein contains three conserved clusters of highly basic residues in the first 120 amino acids (6), and the ability of the core protein to bind RNA has been localized to amino acids 1 to 75 (35). Core protein has been observed to bind to the HCV 5′UTR core, E1, and E2 gene sequences, to tRNA, and to 60S rRNA (13, 35, 38). The 5′UTR is highly conserved among HCV sequences and contains an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) important for the initiation of cap-independent translation of the genome. The 5′UTR is predicted to contain extensive secondary and tertiary structure (4, 5, 20, 21). Interactions between the core protein and defined regions of the 5′UTR, including loops I and IIId, and nucleotides (nt) 23 to 41 have been reported. RNA secondary structure, as well as the presence of G-rich sequences, has been proposed as a factor mediating interactions between core protein and RNA (40). The finding of oligomerization of the core protein upon binding to the 5′UTR (13, 38) suggests that core protein multimerization and binding to viral RNA may be interdependent functions that play a role in assembly of the HCV nucleocapsid and virus.

Little is known about the in vivo assembly pathway or structure of the HCV nucleocapsid and virion. Analogous to other flaviviruses, HCV core proteins likely interact with viral RNA to form nucleocapsid particles either in the host cell's cytoplasm or on the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). These particles interact with viral envelope proteins that traverse the ER membrane and subsequently form enveloped virions by budding into the ER lumen. Immunogenic virus-like particles have been detected in infectious sera and mammalian, insect, and yeast cell culture systems (1, 12, 23, 37). These virus-like particles form 30- to 80-nm-diameter spheres as estimated by electron microscopy (EM) and filtration studies (18, 23, 31, 37). In addition, 30- to 40-nm spherical particles have been detected in infectious sera treated with detergent and enriched for core protein (39). Unfortunately, particle counts in these systems are too low for detailed analysis of virus structure.

For many RNA viruses, assembly is believed to be initiated by the binding of the core protein to a unique encapsidation sequence within the viral genome, often a UTR with stem-loop structure (9, 13). This interaction facilitates oligomerization of the core protein and the sequential formation of an assembled virus particle. In vitro systems have been established to assemble nucleocapsid-like (NCL) particles in vitro from recombinant alphavirus capsid proteins and nucleic acid (S. J. Watowich, unpublished data; 41) and from recombinant human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins and RNA (3, 7, 16). In this study, we use recombinant HCV core proteins and defined oligonucleotides to self-assemble NCL particles in vitro. Our results delineate core protein and oligonucleotide structural elements necessary for self-assembly and show that efficient self-assembly of core proteins into NCL particles requires structured RNA molecules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and expression of HCV core proteins.

A pET28a plasmid (Novagen) containing cDNA encoding core, E1, and E2 proteins for HCV (genotype 1a, isolate AG94) was used to generate two core constructs. HCVC 124 (HCV core residues 1 to 124) was amplified by PCR with primers 5′-GGGAAATCCATATGAGCACGAATCCTAAACCTCAAAGAAAA-3′ and 5′-CCGGAATTCTCATTAATCGATGACCTTACCCAAATTGCGCGA-3′. HCVC 179 (HCV core residues 1 to 179) was amplified by PCR with the same sense primer used to generate HCVC 124 and the antisense primer 5′-CCGGAATTCTCATTACAGAAGGAAGATAGAGAAAGAGCAACC-3′. Both PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes NdeI and EcoRI (Promega) and separately cloned in a pET30a expression vector (Novagen). The fidelity of the cloned core sequences was confirmed by DNA sequencing (T. Woods, University of Texas Medical Branch [UTMB]). Escherichia coli-expressing BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with core-expressing pET30a constructs and maintained in 2× YT medium.

HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 were expressed from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells grown at 37°C in the presence of kanamycin (30 μg/ml). Protein expression was initiated with the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when the optical density at 600 nm reached ∼0.7 and ∼1.0 for cultures containing the HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 constructs, respectively. Induction was continued for 3 h at 25°C.

Purification of HCV core proteins.

Recombinant HCVC 124 was solubilized from bacterial pellets using ice-cold urea buffer (25 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 7.0], 8 M urea, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) and mild sonication. HCVC 179 was solubilized from bacterial pellets using a series of ice-cold lysis buffers (buffer 1, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.0] plus 2 mM DTT; buffer 2, 20 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 7.0] plus 8 M urea; buffer 3, 20 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 6.5], 500 mM NaCl, and 8 M urea). Solutions of HCVC 179 in buffer 3 were diluted twofold with 8 M urea and incubated overnight at 4°C with 50 mM DDT. Core protein in the clarified lysate was applied to a cation-exchange column (Poros 20 CM; Perseptive Biosystems) equilibrated with denaturing cation buffer (0.25 M HEPES [pH 7.0], 8 M urea, 1.5 M NaCl). Core protein was eluted with a linear NaCl gradient. Fractions containing core protein were subsequently applied to a reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography column (YMC) and eluted with a linear 20 mM sodium phosphate–methanol (pH 3.0) gradient. Eluted fractions containing core protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against refolding buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 100 mM NaCl) and concentrated by ultrafiltration (Centricon filtration units; Amicon). The homogeneity of the purified core proteins was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and confirmed by Western immunoblot analysis using rabbit polyclonal antibodies generated against HCVC 179 (Watowich, unpublished).

Generation of nucleic acid templates.

Yeast tRNAPhe was obtained from commercial preparations (Boehringer Mannheim). Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotides (oligo-A, oligo-B, and oligo-C; sequences shown in Fig. 3C) were synthesized commercially (Keystone Laboratories) and used without additional purification. Oligo-A and oligo-C had no sequence similarity to the HCV genome. The 3′ region of oligo-B corresponded to the first 30 nt of HCV core cDNA.

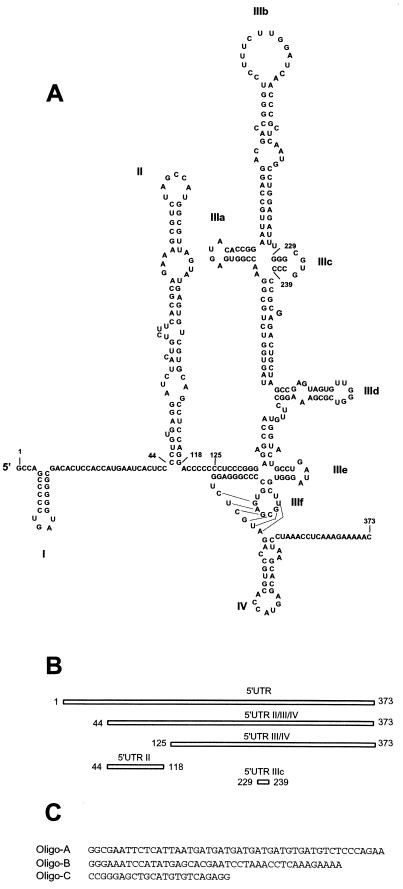

FIG. 3.

Sequences and secondary structure of nucleic acids used for assembly. (A) Secondary structure within the complete 5′UTR of HCV and immediately downstream open reading frame (20). Numbered nucleotides indicated boundaries of the RNA constructs used in the assembly reactions. (B) Linear representation showing extents and locations of the RNA constructs used in the assembly reactions. (C) Sequences of ssDNA oligonucleotides used in the assembly reactions.

Double-stranded DNA-A (dsDNA-A) was the PCR-amplified HCVC 179 product described above. dsDNA-B contained nt 1 to 420 of the HCV core sequence and was amplified from pET28a containing the HCV core, E1, and E2 genes of HCV AG94, using primers 5′-G GGAAATCCATATGAGCAATCCTAAACCTCAAAGAAAA-3′ and 5′-CCGGAATTCTCATTAGACGAGCGGTATGTACCCCATGAGGTC-3′.

PCR products were used as templates for in vitro transcription (Ambion MEGAshortscript kit) of HCV UTR RNAs. The plasmid used for template generation of all 5′UTR constructs contained the full-length 5′UTR of HCV (Hutchinson strain, genotype 1a) and 32 nt of core coding sequence, fused at the 5′ end to a T7 promoter and at the 3′ end to a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene (R. Rijnbrand, P. C. Bredenbeek, P. C. Haasnoot, W. J. M. Spaan, and S. M. Lemon, submitted for publication). Primer 3′-GTGTTAGGTACCGTTTTTCTTTGAGG-5′ was used for the 3′ ends of three of the 5′UTR templates. The extended 5′-end genome, including the full-length 5′UTR and the first 32 nt of core coding sequence (nt 1 to 373), was amplified from the 5′ end with a T7 promoter (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATA-3′). The 5′-end primer for 5′UTR II/III/IV (nt 44 to 373) was 5′-CGGA ATTCTAATACGACTCACCTATAGGCCCTGTGAGGATCTAC-3′, and the 5′-end primer for 5′UTR III/IV (nt 125 to 373) was 5′-TCCGGATCCTAATAC GACTCACTATAGGCCTCCCGGG-3′. 5′UTR II (nt 44 to 118) was generated with primers 5′-CGGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCCCTGTGAG GATCTAC-3′ and 3′-CGCGGATCCGGGCCCTGGAGGCTGCACGACAC-5′. 5′UTR IIIc (nt 229 to 238) was generated with primers 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′ and 3′-GATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCGCACGGG-5′. The template for the full-length genomic transcription (Ambion MEGAscript kit) was an infectious clone from the HCV-1b Japanese strain (2).

RNA folding and unfolding.

All RNA transcripts were DNase treated before assembly experiments. RNA unfolding experiments were carried out by heating either tRNA or 5′UTR II at 95°C for 5 min in 100 mM EDTA, followed by quenching on ice for 10 min. RNA unfolding reactions were monitored by UV spectroscopy measuring absorption at 260 nm and by gel electrophoresis. Two percent agarose gels were prepared in 20 mM Tris-acetate–0.5 mM EDTA electrophoresis buffer. A 0.24- to 9.5-kb RNA ladder (GibcoBRL) was used as a marker, and samples were loaded with a 0.25% bromophenol blue–40% (wt/vol) sucrose in water buffer that included 10 μg of ethidium bromide/ml.

In vitro assembly reactions.

In vitro assembly reactions were carried out using purified core proteins HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 and nucleic acid substrates. Ten micromolar core protein in assembly buffer (1.7 mM magnesium acetate, 100 mM potassium acetate, 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]) was mixed with an equal volume of nucleic acid under RNase-free conditions. The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 10 min followed by 15 min on ice. The nucleic acid concentration was varied to create different protein/nucleic acid molar ratios. To determine relative amounts of core protein and RNA assembled into particles, assembly reactions were digested with 100:1 (wt/wt) trypsin (Pierce) in assembly buffer with 20 mM CaCl2 at room temperature. Proteolytic digestion of the core protein was monitored with Coomassie blue-stained 16% polyacrylamide gels run under denaturing conditions. Unincorporated RNA was monitored by ethidium bromide staining in 2% agarose gels as described above.

EM.

Samples (10 μl) of each assembly reaction were adsorbed to 400-mesh carbon-Formvar grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 10 min. Grids were washed three times with 100 mM ammonium acetate or deionized H2O and stained for 1 to 2 min with filtered 1 to 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate. Grids were then wick dried with filter paper, air dried for at least 5 min, and examined on a Philips EM201 electron microscope with an acceleration voltage of 60 kV at a magnification of ×94,000. Images were captured on Kodak 4489 EM film.

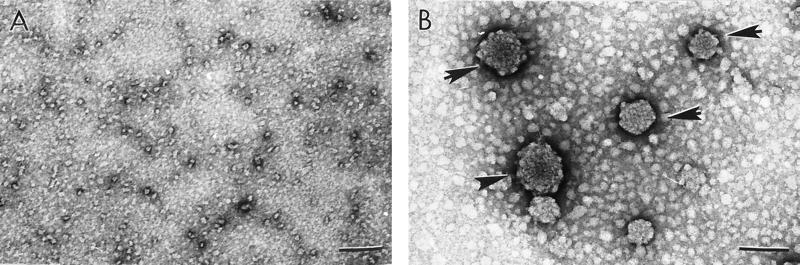

Immunogold-labeled EM.

Carbon-Formvar grids were floated for 10 min on a 10-μl sample of assembly reaction. Grids were incubated with anti-HCVC 179 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:100 in 1% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin–phosphate-buffered saline [BSA-PBS]) for 30 min at room temperature in a wet chamber. Grids were washed four times with 1% (wt/vol) BSA-PBS and then incubated for 30 min with anti-rabbit antibody (Amersham Auroprobe Ab labeled with 15-nm gold particles) diluted 1:20 in 1% (wt/vol) BSA-PBS at room temperature in a wet chamber. Grids were then washed with deionized H2O and stained as described above.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of HCV core proteins.

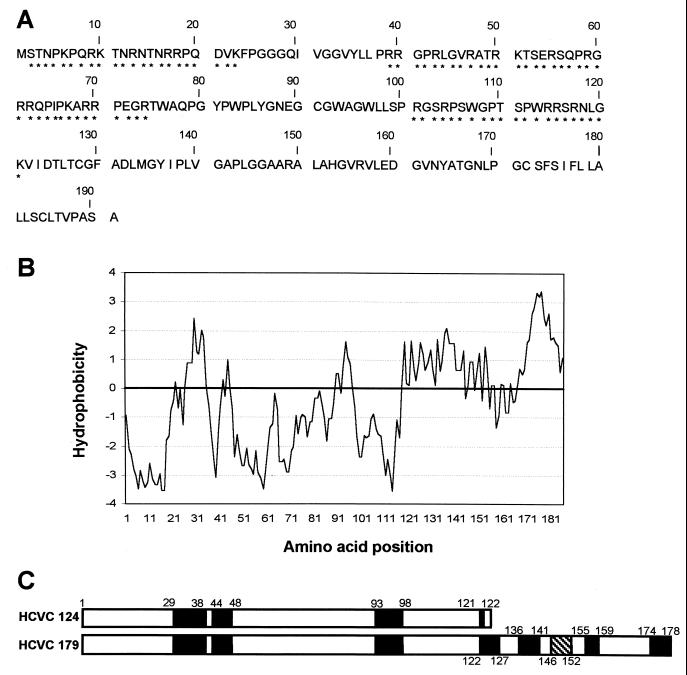

HCVC 124 encompasses the highly basic amino terminus of the core protein that is responsible for RNA binding and excludes the highly hydrophobic sequences in the carboxy terminus of the protein. This construct was designed to minimize potential solubility problems associated with expressing proteins containing highly hydrophobic regions. HCVC 179 corresponds to one of the largest core proteins identified in the literature as P21 (22), the mature core protein product of posttranslational cleavage (Fig. 1). Although the carboxy terminus of HCVC 179 is hydrophobic and includes the first seven residues of the putative peptidase signal sequence for the E1 glycoprotein (Fig. 1), milligram quantities of purified soluble HCVC 179 could be generated. Thus, HCVC 179 was used in subsequent assembly reactions, with the recombinant HCVC 179 protein containing all potential interaction sites that might exist in the mature core protein. Analysis of the HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 primary sequences predicts that these proteins contain few alpha helix and extended-strand secondary structures.

FIG. 1.

Sequence analysis of HCV-1a core protein. (A) Amino acid sequence of full-length core protein, highlighting conserved basic, positively charged clusters (∗) at residues 2 to 23, 39 to 74, and 101 to 121. (B) Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity plot of core residues 1 to 191, using ProtScale tool (24). (C) Schematic of HCV core constructs HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 with predicted secondary structure determined using the PHD method (33, 34). □, random coil; ■, extended strand;  , alpha helix.

, alpha helix.

Expression protocols were optimized to produce high levels of expressed core protein. Core protein expression was induced with IPTG toward the end of the exponential growth phase of the bacterial culture, since bacterial growth was severely impeded following induction. Typical yields of purified core protein from a 1-liter bacterial culture are ∼10 and ∼5 mg for HCVC 124 and HCVC 179, respectively. Plasmids containing HCVC residues 1 to 191, corresponding to the immature core protein P23 and containing the 19-residue hydrophobic E1 peptidase signal sequence, were constructed but did not show significant protein expression in bacterial culture.

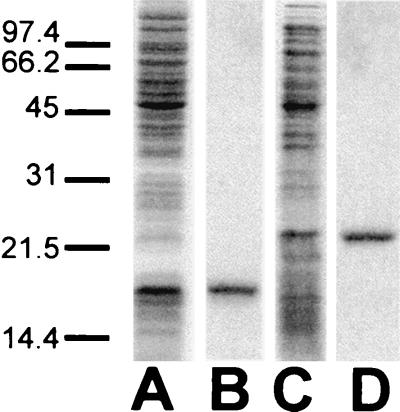

Both HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 were purified to electrophoretic homogeneity (Fig. 2) and confirmed by Western immunoblot analysis (data not shown). Separate N-terminal peptide sequencing (S. Smith, UTMB) of the first five residues of HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 yielded the sequence Ser-Thr-Ans-Pro-Lys, which corresponds to amino acids 2 to 6 of the core protein. The initial methione residue is presumably removed during posttranslational processing events during expression in bacterial cell culture. Ion spray (A. Huiker, UTMB) and matrix-assisted laser desorption (core laboratory, Louisiana State University) mass spectrometry indicated that the experimental masses of HCVC 179 and HCVC 124, respectively, were consistent with the masses predicted from the amino acid sequence.

FIG. 2.

HCV core expression and purification. All samples were resolved on an SDS–16% polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions and visualized by Coomassie blue stain. Lanes: A, expression of HCVC 124 in lysed bacterial cell pellets; B, purified HCVC 124; C, expression of HCVC 179 in lysed bacterial cell pellets; D, purified HCVC 179. Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons.

Denaturing conditions were necessary during cell lysis and core protein purification to ensure the removal of all bound nucleotides. Denatured proteins were refolded in a Tris-NaCl buffer at neutral pH. As judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2), HCVC 124 and HCVC 179 have apparent molecular masses of 16 and 21 kDa, respectively. In the absence of DTT in the loading buffer, a small fraction of each protein (<10%) ran as a disulfide-linked dimer on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (data not shown).

Oligonucleotide structure.

Core protein has been shown to bind nonviral RNA and RNA corresponding to segments of the HCV genome. Different regions of the 5′UTR have been reported to selectively bind core protein. Therefore, RNA oligonucleotides corresponding to the 5′UTR, and containing predicted secondary structural elements, were tested for the ability to assemble into NCL particles.

Figure 3A shows the predicted secondary structure of the 5′UTR for HCV (20); the 5′ and 3′ ends that define the different constructs are numbered. The four stem-loops within the 5′UTR are labeled I through IV, and nt 44 to 353 (stem-loops II to IV) form the IRES (21). Figure 3B shows the position of each RNA construct within the 5′UTR. The major products produced from transcription reactions of full-length 5′UTR, 5′UTR II/III/IV, and 5′UTR II were single folded species. Only a small population of unfolded product was produced in each transcription reaction, as visualized on agarose gels (data not shown). Transcription reactions from 5′UTR III/IV cDNA produced a mixture of folded and unfolded products in an approximate 1:1 ratio as visualized on agarose gels (data not shown). Agarose gel electrophoresis could readily discriminate between folded and unfolded RNA molecules produced by the transcription reactions (Fig. 4).

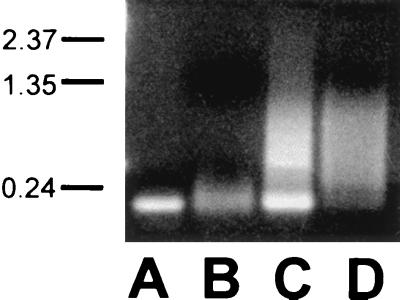

FIG. 4.

Two percent agarose gel showing folded or unfolded state of nucleic acids. Samples were loaded with 10 μg of ethidium bromide/ml in gel loading buffer. Marker hatches on left are in kilobases. Lanes: A, folded tRNA in H2O; B, unfolded tRNA in 100 mM EDTA; C, folded 5′UTR II in H2O; D, unfolded 5′UTR II in 100 mM EDTA.

Significant stem-loop secondary structure is predicted to occur in the cloverleaf structure of tRNAPhe (29, 43). The presence of secondary structure in tRNA was confirmed using agarose gels electrophoresis and tRNA samples loaded in native and denaturing buffers (Fig. 4). The sequences of the ssDNA oligonucleotides (Fig. 3C) are predicted to contain no stable secondary structure, although oligo-B is predicted to adopt a marginally stable stem-loop structure consisting of a 4-bp stem and a 15-nt loop (29, 44). The structures of the dsDNA substrates are predicted to be helical.

In vitro self-assembly of NCL particles and particle morphology.

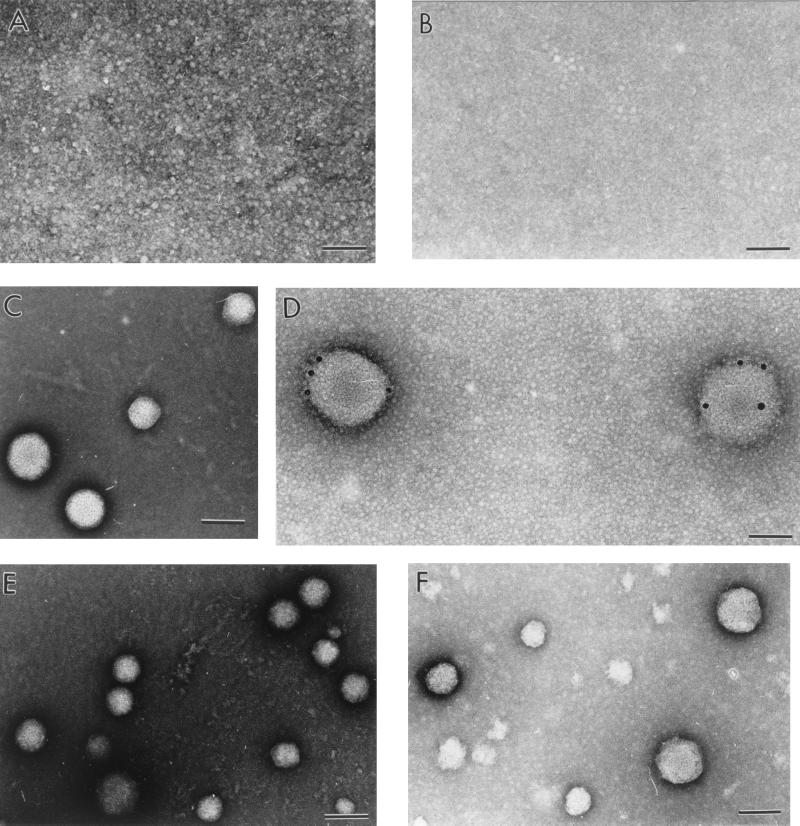

The addition of structured RNAs to purified recombinant core protein preparations resulted in the formation of NCL particles (Fig. 5E). In vitro self-assembly reactions were adapted from protocols established to assemble NCL particles from purified Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus capsid protein (Watowich, unpublished). Self-assembly was analyzed by negative-staining EM. Successful assembly reactions produced a large population of regular, spherical particles at a modal size. These NCL particles had a smooth appearance and showed a fine granularity. The diameter of these particles ranged from 30 to 120 nm, and the average modal diameter was ∼60 nm. Successful self-assembly reactions resulted in large numbers of NCL particles that covered the EM grids. However, these successful assembly reactions always contained a few particles present that were smaller and larger than the dominant species; in several instances, particularly in HCVC 179 assembly reactions, only irregular particles were observed. At low magnification, these particles resembled NCL particles in size, shape, and distribution on the EM grid. As magnification was increased, it was clear that the particles had a jagged outline, which differed from particle to particle. Though lacking any symmetrical appearance, these irregular particles had dimensions similar to those of the NCL particles. Techniques such as sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis or gel assays would have been unable to distinguish NCL particles from the irregular particles.

FIG. 5.

Micrographs of negatively stained samples. All samples were incubated as described in Materials and Methods. (A) HCVC 124; (B) tRNA; (C) HCVC 124 and tRNA in 10:1 ratio; (D) immunogold-labeled HCVC 124 and tRNA particles from 10:1 ratio sample; (E) HCVC 124 and 5′UTR II/III/IV in 10:1 ratio; (F) HCVC 124 and 5′UTR in 10:1 ratio. Bars, 100 nm.

The formation of these irregular particles was readily distinguishable from general aggregation. Nonspecific aggregation resulted in large masses of protein or weblike clusters of nucleic acid that were very different in appearance from discrete assembled particles. In some of the unsuccessful assemblies, neither irregular particle formation nor aggregation occurred, and the grids appeared blank. These grids were similar to grids of protein alone or nucleic acid alone.

Oligonucleotide requirements for self-assembly of NCL particles with viral RNAs.

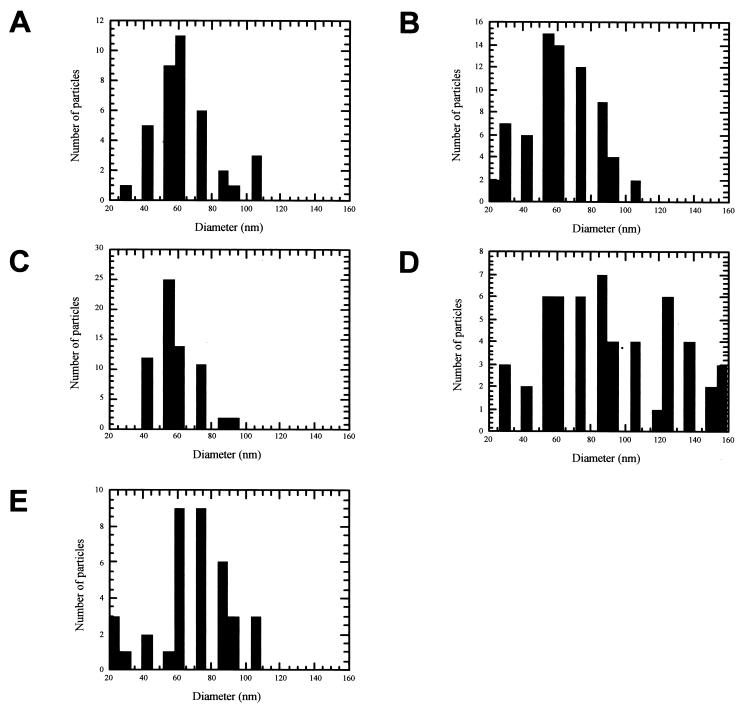

As summarized in Table 1, HCVC 124 could self-assemble into regular, spherical NCL particles with the addition of 5′UTR, 5′UTR II/III/IV, 5′UTR III/IV, and 5′UTR II RNAs (Fig. 5). Figure 6 shows the frequency distribution of particle diameters for each RNA tested, and Table 2 gives the average diameters of these particles. NCL particle morphology and size distribution were independent of the HCVC 124/RNA molar ratio used in the assembly reaction. Self-assembly occurred between HCVC 124 and either 5′UTR, 5′UTR II/III/IV, or 5′UTR III/IV at all molar ratios tested, implying that assembly was supported with an excess of either protein or RNA. In contrast, self-assembly between HCVC 124 and 5′UTR II was observed only at a 5:1 molar ratio. NCL particles ranged in size from ∼30 to 160 nm and formed a modal population centered at ∼60-nm diameter (Fig. 6; Table 2). The one exception was NCL particles assembled with 5′UTR III/IV that did not show a unique dominant particle diameter. 5′UTR III/IV migrated as a broad diffuse band on nondenaturing agarose gels (data not shown), implying that the RNA did not fold into a stable structured molecules during the in vitro transcription process. Thus, self-assembly may have occurred with a heterogeneous population of differently folded RNAs. HCVC 124 did not form NCL particles with 5′UTR IIIc, and these grids were indistinguishable grids containing either core protein alone or nucleic acid alone.

TABLE 1.

HCV core self-assembly

| Nucleic acid | Type | Size | Assembly | Core protein, nucleic acid molar ratio(s)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempteda | Successful | ||||

| HCVC 124 | |||||

| HCV 1b genome | ssRNA | 9,616 nt | No | 1,000:1, 500:1, 400:1, 200:1, 100:1 | |

| 5′UTR HCV | ssRNA | 397 nt | Yes | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 |

| 5′UTR II/III/IV | ssRNA | 329 nt | Yes | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 |

| 5′UTR III/IV | ssRNA | 248 nt | Yes | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 |

| 5′UTR IIIc | ssRNA | 10 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | |

| 5′UTR II | ssRNA | 74 nt | Yes | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | 5:1 |

| 5′UTR II (unfolded) | ssRNA | 74 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | |

| tRNA | ssRNA | 75 nt | Yes | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1 |

| tRNA (unfolded) | ssRNA | 75 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | |

| Oligo-A | ssDNA | 60 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | |

| Oligo-B | ssDNA | 41 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | |

| Oligo-C | ssDNA | 23 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | |

| dsDNA-A | dsDNA | 537 bp | No | 100:1, 10:1 | |

| dsDNA-B | dsDNA | 420 bp | IPa | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1 |

| None | No | ||||

| HCVC 179 | |||||

| HCV 1b genome | ssRNA | 9,616 nt | No | 1,000:1, 500:1, 400:1, 200:1, 100:1 | |

| 5′UTR HCV | ssRNA | 397 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 |

| 5′UTR II/III/IV | ssRNA | 329 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 |

| 5′UTR III/IV | ssRNA | 248 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 100:1, 1:1 |

| 5′UTR IIIc | ssRNA | 10 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | |

| 5′UTR II | ssRNA | 74 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | 5:1 |

| 5′UTR II (unfolded) | ssRNA | 74 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | 10:1, 5:1 |

| tRNA | ssRNA | 75 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1 |

| tRNA (unfolded) | ssRNA | 75 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, 1:10 | 100:1, 10:11 |

| Oligo-A | ssDNA | 60 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | |

| Oligo-B | ssDNA | 41 nt | IP | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | 10:1 |

| Oligo-C | ssDNA | 23 nt | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1 | |

| dsDNA-A | dsDNA | 537 bp | No | 100:1, 10:1 | |

| dsDNA-B | dsDNA | 420 bp | No | 100:1, 10:1, 5:1 | |

| None | No | ||||

IP, Irregular particles which resemble NCL particles in size and number but do not have symmetrical appearance.

FIG. 6.

Histograms representing the frequency distribution of particle diameters in assembly experiments of HCVC 124 with various nucleic acids. (A) 5′UTR HCV; (B) 5′UTR HCV II/III/IV; (C) 5′UTR HCV II; (D) 5′UTR HCV III/IV; (E) tRNA.

TABLE 2.

Diameters of NCL particles assembled with HCVC 124

| RNA | No. of measurements | Avg diam (nm) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| 5′UTR HCV | 40 | 65.3 ± 21.2 |

| 5′UTR II/III/IV | 73 | 61.7 ± 21.3 |

| 5′UTR III/IV | 56 | 90.7 ± 37.6 |

| 5′UTR II | 68 | 58.9 ± 14.6 |

| tRNA | 38 | 70.1 ± 22.7 |

HCVC 179 was unable to self-assemble NCL particles with any of the 5′UTR oligonucleotides tested (Table 1). Instead HCVC 179 self-assembled into irregular particles with 5′UTR, 5′UTR II/III/IV, 5′UTR III/IV, and 5′UTR II (Fig. 7). Particle morphology and size distribution were independent of the HCVC 179/RNA molar ratio used in assembly reactions. These results, shown in Table 1, indicate that HCVC 179 formed irregular particles under the same conditions that produced NCL particles for HCVC 124. One exception to this phenomenon occurred in the unfolded 5′UTR II assembly reactions. 5′UTR II was unfolded to determine if secondary structure in the nucleic acid was required for successful assembly. The unfolded state of the 5′UTR II was confirmed by electrophoretic analysis (Fig. 4). HCVC 124 did not form NCL particles with unfolded 5′UTR II but instead produced large (>400-nm), aggregated masses that were distributed sparsely across the grids. HCVC 179 formed irregular particles with unfolded 5′UTR II under the same conditions.

FIG. 7.

Micrographs of negatively stained samples of HCVC 179 incubated as described in Materials and Methods. (A) HCVC 179; (B) HCVC 179 and tRNA in 10:1 ratio, showing irregular particle formation. Bars, 100 nm.

RNA corresponding to the entire HCV genome was synthesized to test whether core protein and the full-length HCV RNA could self-assemble a homogeneous population of NCL particles. We also wanted to determine if a viral sequence outside the 5′UTR region and HCVC 179 could self-assemble into NCL particle. In vitro transcription from an infectious cDNA clone produced RNA that migrated on an agarose gel as a single band of approximately 9.6 kb. Neither HCVC 179 nor HCVC 124 assembled with the full-length genome. All samples showed significant aggregation of protein and nucleic acid. It is possible that the viral genome is not folded properly in vitro and thus cannot serve as a substrate for core protein self-assembly.

Oligonucleotide requirements for NCL particle assembly with nonviral nucleic acids.

The oligonucleotide requirements for in vitro self-assembly were further analyzed by testing the ability of the core protein to assemble with nonviral nucleic acids. tRNA was chosen as a representative nonviral RNA because it had been used successfully as a substrate for in vitro assembly reactions of other viruses (Watowich, unpublished; 41), and HCV core has been shown to bind tRNA (13). Like the 5′UTR, tRNA possesses significant stem-loop structure, which allowed for an examination of the role of secondary structure in NCL particle assembly. Assembly reactions of HCVC 124 and tRNA generated large amounts of regular, spherical NCL particles. These particles were not observed with tRNA alone or with core protein alone (Fig. 5C). HCVC 124/tRNA molar ratios from 100:1 to 1:10 were tested for self-assembly, and molar ratios of 100:1, 10:1, and 5:1 formed NCL particles.

NCL particles formed when a fivefold molar excess of core protein relative to tRNA was present in solution. RNA amounts in excess of this level could not bind sufficient core protein to self-assemble complete NCL particles. As demonstrated by electrophoretic gel shift experiments, all tRNA present in 5:1 and 10:1 assembly reactions were incorporated into NCL particles (data not shown). In addition, the resulting particles contained a molar equivalent of HCVC 124 to tRNA, even when the assembly reaction initially contained a molar excess of core protein relative to tRNA (data not shown).

Ratios of 1:1 and 1:10 yielded small numbers of large, aggregated masses (>400 nm). HCVC 179 and tRNA formed irregular particles at the same molar ratios that HCVC 124 and tRNA formed NCL particles. The outcomes of these experiments were not affected by performing the in vitro assembly reactions under reducing conditions (50 mM DTT).

Unfolded tRNA could not support core assembly at any ratio. The unfolded state of the tRNA was confirmed by electrophoretic analysis (Fig. 4). All samples with unfolded tRNA looked similar to grids with only protein or only RNA except at the 1:10 ratio, in which large (>400 nm) particles were formed.

DNAs were also tested as substrates to further delineate the specificity of the assembly reactions. Full-length core protein has been reported to bind oligomeric DNAs and RNAs with similar affinity (40). In this study, assembly of NCL particles was not seen with either HCVC 124 or HCVC 179 and ssDNA (oligo-A, oligo-B, and oligo-C). All grids resembled negative controls with the exception of HCVC 179 with oligo-B, which produced irregular particles similar in size and number to irregular particles assembled with structured RNA. It is possible that the marginally stable stem-loop structure in oligo-B is stabilized by the hydrophobic carboxy-terminal residues of HCVC 179, and this structure promotes core self-assembly. dsDNA-A and dsDNA-B oligonucleotides did not form NCL particles with either core protein. However, HCVC 124 and dsDNA-B produced irregular particles (Table 1).

Experimental parameters and conditions.

A number of experimental parameters were examined to further define the conditions that supported core protein self-assembly. Phosphate buffers at neutral pH could support self-assembly of NCL particles, and so it appears that NCL assembly is not strictly confined to the conditions of the acetate buffer described in Methods and Materials. Using successful protein/tRNA molar ratios (Table 1), NCL particles assembled with core concentrations ranging from 10 μg/ml to 1 mg/ml without precipitation of assembly components. A core protein concentration of 10 μM was the lowest that consistently produced large amounts of NCL particles and thus was chosen as the standard concentration for the in vitro assembly reactions. At high protein and nucleic acid concentrations, successful assembly reactions resulted in an easily visualized turbid solution. Using a core protein concentration of 10 μM, the self-assembly reactions were sufficiently dilute so as not to have a readily identified turbid appearance. Changing the assembly reaction volume from 25 μl to 1 ml did not affect the results of the core self-assembly reactions, in contrast to observations in other systems (41). All reactions were kept at 50 μl, which allowed a minimal expenditure of materials with enough sample to prepare multiple EM grids.

DISCUSSION

The study of HCV assembly and structure is severely limited by the lack of a stable replicating cell culture system. Current methods of generating virus-like particles do not yield sufficient particles for detailed studies. We have shown that HCV core proteins can be expressed from a bacterial system and purified to homogeneity. These recombinant core proteins efficiently self-assemble in vitro into NCL particles with a regular, spherical morphology. These particles have a modal diameter centered around 60 nm. Core protein is capable of assembling into NCL particles in the presence of structured RNAs. The first 124 amino acids of the core protein contain the necessary structural elements for self-assembly. Inclusion of the carboxy-terminal domain of the core protein modifies the self-assembly pathway such that the resultant particles have an irregular, jagged outline. However, HCVC 179 self-assembly is similar in efficiency and produces particles similar in size and shape those produced by HCVC 124 self-assembly.

The formation of NCL particles by HCVC 124 occurred with structured full-length 5′UTR, 5′UTR II/III/IV, 5′UTR III/IV, 5′UTR II, and tRNA. NCL particle formation was not observed in the absence of nucleic acid, which indicates the interaction between the core protein and nucleic acid is critical for self-assembly. The experiments with 5′UTR II and tRNA demonstrate that secondary stem-loop structures within the nucleic acid substrate are crucial to the formation of NCL particles. HCVC 124 and folded 5′UTR II efficiently formed NCL particles at a 5:1 molar ratio, but only a few large, aggregated irregular particles were observed when unfolded 5′UTR II was used as an assembly substrate. Similarly, HCVC 124 and folded tRNA efficiently formed NCL particles. However, unfolded tRNA was unable to support HCVC 124 self-assembly. At a core/unfolded tRNA ratio of 1:10, a few very large particles were formed, which might have been produced due to the presence of small amounts of folded tRNA in the assembly reactions. The HCV 5′UTR construct is predicted to contain significant stem-loop structure, which likely contributed to their ability to form particles with HCVC 124, as other nucleic acids of similar size but lacking stem-loop structure were unable to support assembly.

A previous study reported that core does not have strong affinity for the 5′UTR stem-loops IIIc and II (40). However, 5′UTR II RNA was able to support self-assembly of NCL particles under a limited range of conditions. This implies that the core protein can undergo self-assembly with some weak binding RNA molecules. The failure of 5′UTR IIIc to form NCL particles might be explained by unfolding of the small oligonucleotide at the temperature used in the assembly reaction or by very weak binding between core and 5′UTR IIIc, or the core protein may require a RNA substrate larger than 10 nt to initiate self-assembly. In contrast, ssDNA and dsDNA did not support core self-assembly, although binding between core protein P23 and DNA has been reported (40). This could be due to weak affinity between the different core protein and DNA sequences used in the self-assembly reaction or to a decoupling between binding and self-assembly, implying that nucleotides that serve as substrates for core protein binding do not necessarily function as substrates for core protein self-assembly.

It is interesting that core product HCVC 179 was able to self-assemble into only irregular particles, while HCVC 124, predicted to be largely unstructured, forms regular, spherical NCL particles with a number of structured RNA substrates. It is clear that the amino terminus of the core protein is capable of binding RNA (13, 35, 38). In addition, structural elements in the amino terminus of the protein likely participate in extensive and defined core-core interactions in the NCL particle, which support earlier studies that concluded residues 36 to 91 and 82 to 102 were involved in homotypic association (28, 32). It is possible that the HCVC 179 protein is larger than the posttranslationally processed P21 core protein involved in in vivo nucleocapsid assembly and this larger size interferes with self-assembly of NCL particles. This phenomenon has been observed in retrovirus self-assembly, where particle morphology is dependent on the size of the Gag protein used in the assembly reaction (16). However, it cannot be ruled out that the carboxy terminus of the core protein functions as a regulatory domain to modulate nucleocapsid formation by changing the interaction between core protein and nucleic acid or homotypic interactions among core subunits. A reported homotypic interaction for the carboxy terminus of the core (42) suggests that this region could affect its self-associative properties.

The number of protein subunits that form a viral capsid is correlated with capsid diameter (8). Icosahedral viruses with diameters in the range of 60 to 70 nm typically have triangulation number equal to or greater than 7 (8). Thus, NCL particles may contain at least 420 core subunits. Given the 1:1 stoichiometry observed between HCVC 124 and tRNA, the NCL particles may also contain at least 32 kb of RNA.

The NCL particles formed in this in vitro system resemble nucleocapsids derived from infectious sera in their regular, spherical morphology (23, 37). However, NCL particles isolated from infected hosts are ∼30 to 40 nm in diameter (39), and the NCL particles assembled in vitro are typically 60 nm in diameter with a standard deviation of 20 nm. There are several possible explanations for this size discrepancy and heterogeneity. It may be that incubation and staining conditions must be further optimized to yield NCL particles that are homogeneous in size and more closely approximate the expected size of in vivo-derived nucleocapsids. It is also possible that we are using different core protein or nucleic acid fragments relative to the situation in vivo. The size heterogeneity observed with in vitro-assembled particles implies that the assembled particles are plastic, similar to other RNA viruses (i.e., reovirus, cowpea mosaic viruses, and retroviruses). A specific virus-derived encapsidation sequence may be required to stabilize the core protein and limit its conformational and/or orientational flexibility in the assembled NCL particle, thereby reducing size heterogeneity of the in vitro-assembled particles. Another possibility is that a crucial element of the assembly machinery is missing. Interactions between the core protein and host cellular factors or other viral components, such as the HCV E1 protein (27), may play a critical role in the assembly process.

This in vitro system reproduces many of the essential elements of in vivo HCV nucleocapsid assembly. Thus, this approach shows tremendous potential as a means to study the mechanism of HCV assembly and to map interactions critical for assembly. In addition, the ease and efficiency with which the NCL particles are produced makes this system applicable for high-throughput screening for HCV assembly inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a pilot project grant (S.J.W.) under Hepatitis C Cooperative Research Center grant U19-AI0035 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a fellowship from the Blowitz-Ridgeway/American Liver Foundation (R.R.), and the Sealy Center for Structural Biology.

We thank Li-Hua Ping for providing cDNA of core protein, V. Popov for assistance with EM, K. Kaluarachchi for providing 5′UTRIIIc RNA, and Justin McElhanon for the initial subcloning of HCVC 124 and HCVC 179. We thank W. Chiu, J. Lee, A. Paredes, K. Rajarathman, and T.-H. Wang for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumert T F, Ito S, Wong D T, Liang T J. Hepatitis C virus structural proteins assemble into viruslike particles in insect cells. J Virol. 1998;72:3827–3836. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3827-3836.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard M, Abell G, Honda M, Carroll A, Gartland M, Clarke B, Susuki K, Lanford R, Sangar D V, Lemon S M. An infectious clone of a Japanese genotype 1.b. hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1999;30:316–324. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bothner B, Schneemann A, Marshall D, Reddy V, Johnson J E, Siuzdak G. Crystallographically identical virus capsids display different properties in solution. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:114–116. doi: 10.1038/5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown E A, Zhang H, Ping L-H, Lemon S M. Secondary structure of the 5′ nontranslated regions of hepatitis C virus and pestivirus genomic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5041–5045. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukh J, Purcell R H, Miller R H. Sequence analysis of the 5′ noncoding region of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4942–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukh J, Purcell R H, Miller R H. Sequence analysis of the core gene of 14 hepatitis C virus genotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8239–8243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell S, Vogt V. Self-assembly in vitro of purified CA-NC proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:6487–6497. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casjens S. An introduction to virus structure and assembly. In: Casjens S, editor. Virus structure and assembly. Boston, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc.; 1985. pp. 30–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casjens S. Principles of virion structure, function, and assembly. In: Chiu W, Burnett R M, Garcea R L, editors. Structural biology of viruses. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choo Q L, Kuo G, Weiner A J, Overby L R, Bradley D W, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choo Q-L, Richman K H, Han J H, Berger K, Lee C, Dong C, Gallegos C, Croit D, Medina-Selby A, Barr P J, Weiner A J, Bradley D W, Kuo G, Houghton M. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2451–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falcon V, Garcia C, de la Rosa M C, Menendez I, Seoane J, Grillo J M. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical evidences of core-particle formation in the methylotrophic Pichia pastoris yeast when expressing HCV structural proteins (core-E1) Tissue Cell. 1999;31:117–125. doi: 10.1054/tice.1999.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan Z, Yang Q R, Twu J-S, Sherker A H. Specific in vitro association between the hepatitis C viral genome and core protein. J Med Virol. 1999;59:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francki R I B, Fauquet C M, Knudson D L, Brown F, editors. Classification and nomenclature of viruses: fifth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology, suppl. 2. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grakoui A, Wychowski C, Lin C, Feinstone S, Rice C M. Expression and identification of hepatitis C virus polyprotein cleavage products. J Virol. 1993;67:1385–1395. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1385-1395.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Huckhagel C, Krausslich H-G. N-terminal extension of human immunodeficiency virus capped protein converts the in vitro assembly phenotype form tubular to spherical particles. J Virol. 1998;72:4798–4810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4798-4810.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harada S, Watanabe Y, Takeuchi K, Susuki T, Katayama T, Takebe Y, Saito I, Miyamura T. Expression of processed core protein of hepatitis C virus in mammalian cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3015–3021. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3015-3021.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He L-F, Alling D, Popkin T, Shapiro M, Alter H J, Purcell R H. Determining the size of non-A, non-B hepatitis virus by filtration. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:636–640. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hijikata M, Kato N, Ootsuyama Y, Nakagawa M, Shimotohno K. Gene mapping of the putative structural region of the hepatitis C virus genome by in vitro processing analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda M, Ping L-H, Rijnbrand R C A, Amphlett E, Clarke B, Rowlands D, Lemon S M. Structural requirements for initiation of translation by internal ribosome entry within genome-length hepatitis C virus RNA. Virology. 1996;222:31–42. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honda M, Beard M R, Ping L-H, Lemon S M. A phylogenetically conserved stem-loop structure at the 5′ border of the internal ribosome entry site of hepatitis C virus required for cap-independent viral translation. J Virol. 1999;73:1165–1174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1165-1174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hüssy P, Langen H, Mous J, Jacobsen H. Hepatitis C virus core protein: carboxy-terminal boundaries of two processed species suggest cleavage by a signal peptidase. Virology. 1996;224:93–104. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaito M, Watanabe S, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Yamaguchi K, Kobayashi Y, Konishi M, Yokoi M, Ishida S, Susuki S, Kohara M. Hepatitis C virus particles detected by immunoelectron microscopic study. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1755–1760. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-7-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato N, Hijikata M, Ootsuyama Y, Nakagawa M, Ohkoshi S, Sugimura T, Shimotohno K. Molecular cloning of the human hepatitis C virus genome from Japanese patients with non-A, non-B hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9524–9528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo S-Y, Masiarz F, Hwang S B, Lai M M C, Ou J-H. Differential subcellular localization of hepatitis C virus core gene products. Virology. 1995;213:455–461. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo S-Y, Selby M, Ou J-H. Interaction between hepatitis C virus core protein and E1 envelope protein. J Virol. 1996;70:5177–5182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5177-5182.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto M, Hwang S B, Jeng K-S, Zhu N, Lai M M C. Homotypic interaction and multimerization of hepatitis C virus core protein. Virology. 1996;218:43–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews D H, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner D H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLauchlan J. Properties of the hepatitis C virus core protein: a structural protein that modulates cellular processes. J Viral Hepatol. 2000;7:2–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizuno M, Yamada G, Tanaka T, Shimotohno K, Takatani M, Tsuji T. Virion-like structures in HeLa G cells transfected with the full-length sequence of the hepatitis C virus genome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1933–1940. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolandt O, kern V, Müller H, Pfaff E, Theilmann L, Welker R, Kräusslich H-G. Analysis of hepatitis C virus core protein interaction domains. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1331–1340. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rost B, Sander C. Combining evolutionary information and neural networks to predict protein secondary structure. Proteins. 1994;19:55–72. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santolini E, Migliaccio G, La Monica N. Biosynthesis and biochemical properties of the hepatitis C virus core protein. J Virol. 1994;68:3631–3641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3631-3641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selby M J, Choo Q-L, Berger K, Kuo G, Glazer E, Eckart M, Lee C, Chien D, Kuo C, Houghton M. Expression, identification and subcellular localization of the proteins encoded by the hepatitis C viral genome. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1103–1113. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-6-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu Y K, Feinstone S M, Kkohara M, Purcell R H, Yoshikkura H. Hepatitis C virus: detection of intracellular virus particles by electron microscopy. Hepatology. 1996;23:205–209. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimoike T, Mimori S, Tani H, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T. Interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with viral sense RNA and suppression of its translation. J Virol. 1999;73:9718–9725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9718-9725.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi K, Kishimoto S, Yoshizawa H, Okamoto H, Yoshikawa A, Mishiro S. p26 protein and 33-nm particle associated with nucleocapsid of hepatitis C virus recovered from the circulation of infected hosts. Virology. 1992;191:431–434. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka Y, Shimoike T, Ishii K, Susuki R, Susuki T, Ushijima H, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T. Selective binding of hepatitis C virus core protein to synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to the 5′ untranslated region of the viral genome. Virology. 2000;270:229–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tellinghuisen T, Hamburger A E, Fisher B R, Ostendorp R, Kuhn R J. In vitro assembly of alphavirus cores by using nucleocapsid protein expressed in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1999;73:5309–5319. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5309-5319.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan B-S, Tam M H, Syu W. Self-association of the C-terminal domain of the hepatitis C virus core protein. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:100–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasui K, Wakita T, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Funahashi S-I, Ichikawa M, Kajita T, Morapour D, Wands J R, Kohara M. The native form and maturation process of hepatitis C virus core protein. J Virol. 1998;72:6048–6055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6048-6055.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuker M, Matthews D H, Turner D H. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: A practical guide. In: Barciszewski J, Clark BFC, editors. RNA biochemistry and biotechnology NATO ASI series. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]