Abstract

Background:

Black women and Latinas in their thirties continue to be at risk for HIV transmission via heterosexual intercourse.

Methods:

Informed by the Theory of Gender and Power, this study investigated a longitudinal path model linking experiences of ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence to sexual risk behaviors in adulthood among 492 Black women and Latinas. We also tested whether ethnic-racial identity exploration served as a resilience asset protecting women against the psychological impact of ethnic-racial discrimination. Survey data from female participants in the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, which has followed a cohort of New York City Black and Latinx youth since 1990, were analyzed. Data for this analysis were collected at four time points when participants were on average 19, 24, 29, and 32 years of age. Structural equation modeling was used to examine a hypothesized pathway from earlier ethnic-racial discrimination to later sexual risk behaviors and the protective role of ethnic-racial identity exploration.

Results:

Results confirmed that ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence was linked with sexual risk behaviors in the early thirties via increased levels of affective distress in emerging adulthood, experiences of victimization in young adulthood, and substance use in the early thirties among women low in ethnic-racial identity exploration. We also found that ethnic-racial identity served as a resilience asset, as the association between discrimination in late adolescence and affective distress in emerging adulthood was not significant among women with higher levels of ethnic-racial identity exploration.

Conclusions:

The results provide important preliminary evidence that ethnic-racial identity exploration may serve as a resilience asset among Black women and Latinas confronting racial discrimination. Further, we suggest that ethnic-racial identity exploration may constitute an important facet of critical consciousness.

Keywords: Ethnic-racial identity, Ethnic-racial discrimination, Resilience, Women’s sexual health, Critical consciousness

1. Introduction

There are persistent racial disparities in women’s sexual and reproductive health in the United States (McCree et al., 2020; Sales et al., 2020). According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021), women made up 19% of new HIV infections in the U.S. in 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Among these newly diagnosed women, 55% were Black and 18% were Latina (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). These racial disparities are exacerbated in urban contexts: in New York City in 2019, 63% of women newly diagnosed with HIV were Black, 28% were Latina, and 6% were White (HIV Epidemiology Program, 2021).

Heterosexual transmission contributed to 91% of new HIV diagnoses among Black women and 87% among Latinas in the U.S. women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) (and remains the largest contributor to new HIV diagnoses among Black women and Latinas in New York City (HIV Epidemiology Program, 2021) highlighting the importance of examining factors related to sexual risk behaviors (SRBs) among Black women and Latinas. In this manuscript, we use the term “Black” to include both African American and Caribbean American women and “Latina” to encompass women of Spanish-speaking Caribbean, Central or South American descent. When referring to people of a variety of genders, we employ the term “Latinx” to be most inclusive.

Despite the high prevalence of HIV transmission to Black women and Latinas through heterosexual sex (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021), little longitudinal research exists on the individual, interpersonal and structural risk factors for SRBs in this population, especially racial discrimination (Roberts et al., 2012). Identifying such longitudinal determinants in early adulthood could aid in the development of resources to protect women against SRBs and the associated risks.

1.1. Theoretical framework: Theory of Gender and Power

In this study, we used longitudinal data to examine the pathways to SRBs in Black women and Latinas in their early thirties. Our work is informed by the Theory of Gender and Power, a social-structural theory developed by Connell (1987) and adapted for studying SRBs among women of color by Wingood and DiClemente (2000, 2002) and DePadilla et al. (2011). According to the Theory of Gender and Power, three overlapping social structures influence women’s risk of engaging in SRBs: (1) the Sexual Division of Labor, (2) the Sexual Division of Power, and (3) Affective Attachments and Social Norms. All three structures operate at the societal, interpersonal, and individual levels via social mechanisms that uphold gender inequities to generate risks for women to engage in SRBs (Wingood and DiClemente, 2002; DePadilla et al., 2011; Pahl et al., 2019, 2021a). The current study examines several constructs defined by this theory, including contextual, behavioral, and personal risk factors and exposures (i.e., risks that are acquired, external to, and out of the control of the individual), as described below.

1.2. The sexual division of labor and SRBs

This theory conceptualizes that the Sexual Division of Labor structure generates socioeconomic exposures, such as poverty and low-paying jobs, which facilitate situations in which women must rely on men for survival. Ethnic and/or racial minoritized status is considered a socioeconomic risk factor in this domain (Wingood and DiClemente, 2000; Pahl et al., 2021a).

Although not explored in prior research, ethnic-racial discrimination is best situated within the Sexual Division of Labor, as it gives rise to socioeconomic exposures and risk factors. Ethnic-racial discrimination is a common experience for women of color. It is generally understood as unfair treatment based on a person’s ethnicity and/or race and manifests at multiple social levels (i.e., interpersonal, institutional, structural). It can take the form of overt or subtle interactions (i.e., microaggressions; Sue et al., 2007) that are more difficult to document (e.g., not receiving adequate service, being underestimated). Some acts of ethnic-racial discrimination may not be interpreted as such by the persons experiencing them, underscoring the subjective nature of the phenomenon. Noh and colleagues (1999, p.194) define perceived ethnic-racial discrimination as the “subjective perception of unfair treatment of racial/ethnic groups or members of the groups, based on racial prejudice and ethnocentrism, which may manifest at individual, cultural, or institutional levels”. While we sometimes use the term “perceived ethnic-racial discrimination” to emphasize its subjective nature, we also refer to ethnic-racial discrimination (without the modifier “perceived”) to acknowledge the reality of discrimination that people of color experience across at multiple levels of the environment.

Studies have linked perceived ethnic-racial discrimination to a host of adverse mental health outcomes, including lower levels of satisfaction with life and less general happiness, as well as anxiety and depression. (Ahmed et al., 2007; Soto et al., 2011; Budhwani et al., 2015; Chun et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Respress et al., 2018; Williams, 2018; Williams et al., 2019). Ethnic-racial discrimination is also related to engaging in health-risk behaviors, such as substance use and SRBs (Kwate et al., 2003; Gibbons et al., 2004; Ahmed et al., 2007; Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009). For example, a study found that Black and Latinx drug users who experienced more racial discrimination had more sex ties, which placed them at higher risk for sexually transmitted HIV acquisition (Crawford et al., 2014). Another study found that Black women and Latinas exposed to higher levels of racism engaged in riskier sexual behaviors (Rosenthal and Lobel, 2020).

1.3. The sexual division of power and SRBs

The Sexual Division of Power structure creates circumstances in which women lack power vis-à-vis men in interpersonal relationships. Examples of risk exposures related to this structure are a history of coerced sex, being a survivor of violence, and engaging in substance use (Wingood and DiClemente, 2000). Whereas interpersonal physical violence and injury may occur due to power imbalances between two individuals, this abuse is inscribed within a broader system of inequality that particularly affects racially/ethnically minoritized women (Ayón et al., 2017; Corcoran and Stark, 2019). Ayón et al. (2017), for example, described how the social structures of inequality result in powerlessness, exploitation, and violence against Latinas in the U.S. The national prevalence of physical violence against women is higher among Black women but lower among Latinas, compared to Whites (Smith et al., 2017; Lauritsen and Rezey, 2018), but differences appear to be largely explained by other socioeconomic indicators (Chou et al., 2012). Further, a systematic review of violence against Latinas found important variability in prevalence rates, ranging from 8% to 68% (Gonzalez et al., 2020). An abundant body of literature among Black women and Latinas has documented inextricable associations between alcohol and marijuana use, violence, and SRBs in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Wingood and DiClemente, 2000; Brook et al., 2004; Adimora et al., 2011; Seth et al., 2015).

Experiencing coercion to engage in sex and being a survivor of violence are both associated with HIV risk behaviors, including substance use and SRBs (Logan et al., 2002; Sanders-Phillips, 2002; Capasso and DiClemente, 2019). Women exposed to traumatic experiences, such as coerced sex and violence, often use substances to cope with the traumatogenic effects of these exposures (Kilpatrick et al., 1998; Curtis-Boles and Jenkins-Monroe, 2000; Gibson and Leitenberg, 2001; Stevens-Watkins et al., 2012). This, in turn, increases their likelihood of engaging in SRBs as substance use has been identified as an individual-level risk factor for SRBs (Ellickson et al., 2005; Khan et al., 2009; Adimora et al., 2011; Seth et al., 2011). Despite this, most research in this area is cross-sectional and/or focuses specifically on adolescents. Little research has examined whether violent victimization experiences in emerging adulthood (early 20s) are a significant predictor of future substance use and SRBs among Black women and Latinas.

1.4. The structure of affective attachments and social norms and SRBs

The Structure of Affective Attachments and Social Norms encompasses social exposures that influence women’s intimate relationships with men and facilitate men’s dominance over women in relationships (Wingood and DiClemente, 2002). Having a history of depression and/or psychological distress are personal risk factors associated with this third structure that operate at the individual level (Wingood and DiClemente, 1998; Khan et al., 2009).

Community studies of adult mental health have found links between depression and HIV risk behaviors (Orr et al., 1994; Brown et al., 2006). Hutton et al. (2004) showed that depression was linked to SRBs in a sample of Black adults. Depression has also been associated with increased risk of experiencing intimate partner violence and engaging in hazardous drinking among Latinas and Black women (Senn et al., 2010; McCabe et al., 2018).

The intersection of the structures of the Theory of Gender and Power.

The three structures of power intersect to generate vulnerability to SRBs among women of color (Wingood and DiClemente, 2002), as illustrated below. First, ethnic-racial discrimination can contribute to psychological distress, particularly when its tenets are internalized by the targeted group (Ahmed et al., 2007; Collins, 2000). If members of oppressed groups internalize the inferiority espoused by racist ideologies (consciously or unconsciously), they are more vulnerable to the psychological effects of ethnic-racial discrimination (Ahmed et al., 2007; Graham et al., 2016). Ensuing feelings of worthlessness and depressive mood may make Black women and Latinas more likely to engage and remain in power-imbalanced relationships with potentially violent and coercive partners (Messman-Moore and Long, 2003; Iverson et al., 2011). Research has found that women who suffer from psychological distress are at increased risk of experiencing violence (Anastario et al., 2008; Senn et al., 2010).

A study among Latinx college students found that students who reported higher levels of ethnic discrimination (a stressor) were more likely to develop posttraumatic stress symptoms and unhealthy alcohol use (Cheng and Mallinckrodt, 2015). Psychological distress, violence, and substance use often co-occur among women of color (Jané-Llopis and Matytsina, 2006; Capasso et al., 2021). For example, Werner et al. (2016) found that Black women diagnosed with major depression were at increased risk of having an alcohol use disorder compared to those without depression. Further, the experience of stress and trauma, such as ethnic-racial discrimination, is associated with higher odds of depression and substance use disorders among Black women (Merrick et al., 2019). The current study sought to examine how these interrelated risks and exposures formed a sequence from late adolescence to the early thirties.

1.5. Ethnic-racial identity exploration as a resilience asset

Dimensions of ethnic-racial identity may act as resilience assets (Zimmerman et al., 2013) mitigating the relationship between psychosocial risk factors, including ethnic-racial discrimination, and health behaviors (Belgrave et al., 1994; Scheier et al., 1997; Brook et al., 1998; Sellers and Shelton, 2003; Sellers et al., 2003; Brook and Pahl, 2005; Pahl et al., 2021a,b; Umaña-Taylor, 2011). While ethnicity and race denote different constructs, there is some overlap in the constructs of ethnic and racial identity with regard to their function as a resilience asset. Therefore, we use the hybrid term ethnic-racial identity (ERI) (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Affective dimensions of ERI, such as ethnic pride or affirmation, have repeatedly demonstrated resilience-enhancing effects against depression and loss of self-esteem under conditions of discrimination (Mossakowski, 2003; Wong et al., 2003; Greene et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014).

ERI exploration, the process of examining the personal and social meanings of one’s ethnic-racial group membership within social and structural contexts (Phinney, 1990), promotes well-being among youth primarily via ERI resolution/commitment, that is, the sense of clarity regarding one’s ERI that is gained following exploration (Umaña-Taylor, 2018; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2018). However, when examined as a resilience-enhancing factor in the context of ethnic-racial discrimination, this construct has not always been found to be protective (e.g., Greene et al., 2006; Torres and Ong, 2010; but see Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014 for online racial discrimination). According to some, ERI exploration without resolution can intensify the salience of race and/or ethnicity for the self-concept (Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Phinney, 1989, 1990; Cross, 1991) and thereby render individuals more vulnerable to ethnic-racial discrimination (Sellers and Shelton, 2003; Greene et al., 2006; Yip, 2018). This may be especially true among younger adolescents for whom the exploration of their race and/or ethnicity is part of a normative developmental process contributing to the consolidation of their emerging personal identities (Umaña-Taylor, 2018; Yip, 2018).

However, the meaning of exploring one’s ERI changes depending on the age of the explorer and as part of evolving social contexts (Yip, 2018). Exploration, especially in contemporary emerging and young adults, can also be understood as a questioning attitude towards hegemonic social meanings surrounding ethnicity and race (and racism). Reflecting upon the implications of belonging to an oppressed ethnic and/or racial group creates an awareness of racism and of ethnic-racial discrimination (Phinney, 1993; Cross, 1995; Cross et al., 1998; Pahl and Way, 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2018). This awareness, in turn, can protect a person’s (mental) health, because they can ascribe unfair treatment to racism rather than to a personal characteristic (Sellers et al., 2003). We therefore suggest that ERI exploration in young adults can be conceived of as a dimension of critical consciousness, which includes an awareness of racial and other forms of oppression (Freire, 1973; Watts et al., 2011).

Critical consciousness has been defined as the awareness of oppressed and marginalized groups of the social and structural nature of their oppression (Freire, 1973; Watts et al., 2011). Contributing to this consciousness, ERI exploration may protect young women against the harmful effects of ethnic-racial discrimination, because it explicates the structural nature of racism and can thus prevent the internalization of stereotypical “controlling images” (Collins, 2000). Controlling images are negative stereotypes, which are used to justify and normalize the oppression of subjugated people by locating the source of their unequal treatment in the individuals themselves (Collins, 1991). Internalization of controlling images by members of subjugated groups undermines self-worth and political resistance (Collins, 1991, 2000).

1.6. Contributions to the literature and hypotheses

This paper extends prior research in important ways. First, we examine a longitudinal sequence of exposures and risk factors that develop from late adolescence through young adulthood and assess how they precede SRBs in the early thirties, thus adding a temporal dimension to sexual and reproductive health research. Second, we include ethnic-racial discrimination as an exposure that affects women’s levels of affective distress. Third, we extend research on the predictors of SRBs by examining ERI identity exploration as a resilience asset in the pathway between perceived ethnic-racial discrimination and affective distress.

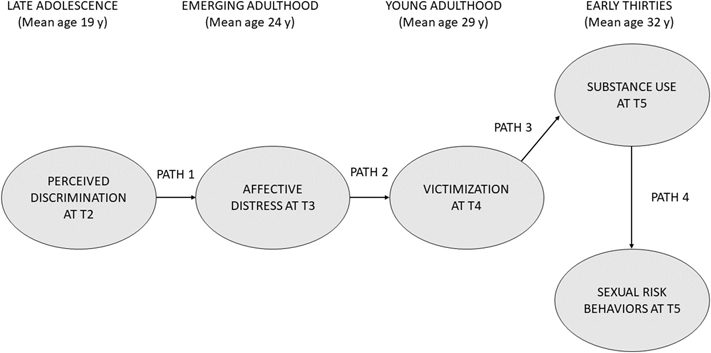

Our primary hypothesis is that ethnic-racial discrimination (a structural, institutional, and interpersonal exposure) during late adolescence impacts Black women’s and Latinas’ future vulnerability to victimization (an interpersonal exposure) via its association with affective distress (a personal risk factor). Exposure to victimization in young adulthood, over time, is hypothesized to influence substance use (a behavioral risk factor) in the early thirties, which is hypothesized to be related to SRBs (see Fig. 1). We further hypothesize that the association between ethnic-racial discrimination and affective distress is moderated by ERI exploration, such that women who engage in ERI exploration at relatively high levels over time will experience less affective distress associated with ethnic-racial discrimination than women reporting lower levels of ERI exploration.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized Structural Equation Model from Perceived Ethnic-Racial Discrimination to Sexual Risk Behaviors among Black women and Latinas, n = 492, Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, New York City, 1994–2013.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Data for this research were collected as part of the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study (HLDS). The HLDS follows a cohort of Black and Latinx young adults who were recruited from 11 high schools in the East Harlem neighborhood of New York City in the 1990s. The Institutional Review Boards of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the New York University School of Medicine approved the study procedures. Detailed descriptions of recruitment, consent, and study procedures, as well as retention strategies and attrition rates at baseline or time 1 (T1) can be found in Brook and Hamburg, (1992) and Brook and Whiteman (1992). To summarize, at T1 surveys were self-administered in classrooms with no teachers present (T1; 1990; N = 1332). Approximately 80% of students recruited at baseline completed the T1 survey (Brook and Whiteman, 1992). At time 2 (T2; 1994–1996; N = 1190), the participants were interviewed in person or by phone. At time 3 (T3; 2000–2001; N = 662), participants were interviewed in person. At time 4 (T4; 2004–2006; N = 838) and time 5 (T5; 2011–2013; N = 674), the data were collected via mailed questionnaires. Mean ages and standard deviations (in years) at each timepoint are the following: T1 – 14.2 (1.3), T2 – 19.2 (1.5), T3 – 24.4 (1.3), T4 – 29.2 (1.3), and T5 – 32.1 (1.5). The percent female at each time-point are as follows: T1 – 53.5%, T2 – 54.5%, T3 – 50.6%, T4 – 59.4% and T5 – 60.7%.

To examine the longitudinal antecedents of SRB among Black and Latina women in their early thirties, we utilized survey data collected from female participants between 1994 and 2013, representing developmental periods of late adolescence (T2, 19 years), emerging adulthood (T3, 24 years), young adulthood (T4, 29 years), and the early thirties (T5, 32 years). To be included in these analyses, the participants had to have data on our outcome of interest, SRBs, at T5. This resulted in a sample of 492 Black women (54.3%) and Latinas (45.7%). Of the 492 participants who participated at T5, 63.2% had data on all four waves used in this study (T2 – T5), 29.5% had data on three waves, and 7.3% had data on two waves. The structural equation algorithm in Mplus dealt with missing data by using full maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén and Muthén, 2010).

2.2. Measures

The outcome measure for this study was a latent construct measuring SRBs in the early thirties (T5). This construct included three indicator variables: Multiple partners – participants were asked if they had had two or more sexual partners in the past 6 months (0 = no, 1 = yes); Sex with just met partner – participants were asked “have you had sex with someone you just met?” (0 = no, 1 = yes); and Sex with untested partner – participants were asked “do you refuse to have sex unless your partner has been tested for HIV?” (1 = yes, 0 = no). The third item was reverse coded so that a higher sum score reflected greater risk behavior. We hypothesized that experiencing ethnic-racial discrimination during late adolescence (T2) would be related to SRBs via affective distress and victimization during emerging (T3) and young (T4) adulthood and substance use in the early thirties (T5). We further hypothesized that the relationship between ethnic-racial discrimination and affective distress would differ by level of ERI exploration (high vs. low).

The ethnic-racial discrimination domain included two scales: experiences of discrimination (original), a 3-item scale measured on a 4-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) “not at all” to (4) “very much” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.64; sample item: “How much have you experienced discrimination by security guards or the police?“); and anger at discrimination (original), a 3-item scale with corresponding items, also measured on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) “not at all” to (5) “very much” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83; sample item: “How angered are you by discrimination at school/work?“).

The affective distress domain included three scales that were adapted from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Derogatis and Savitz, 1999): depressive mood, an 8-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80; e.g., “Over the last few years, how much were you bothered by occasional thoughts of death or dying?“); anxiety, a 3-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77; e. g., “Over the last few years, how much were you bothered by feeling fearful?“); and interpersonal sensitivity, a 4-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76; sample item: “Over the last few years, how much were you bothered by feeling easily annoyed or irritated?“). The answer options for depressive mood, anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “not at all” to (5) “extremely.”

The victimization domain included one scale and one single item. The scale, violent victimization (Chavez and Oetting, 1994), had 5 items with the following answer options: (1) once, (2) twice, (3) 3 or 4 times, and (4) 5 or more times. A sample item read “How often have you experienced that someone held a weapon (gun, club, or knife) to you?” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.73. The single item measure, sexual coercion, was measured by a question that asked whether the participant had been “pushed by someone to have sex” (0 = no, 1 = yes).

The substance use domain included three items: alcohol use – participants were asked how frequently they had used alcohol in the past 5 years. The answer options were: (0) not at all, (1) 1 or 2 drinks a few times a week or less, (2) 1 or 2 drinks a day, (3) 3 or 4 drinks a day, (4) 5 or 6 drinks a day, and (5) more than 6 drinks a day; tobacco use – participants were asked how many cigarettes they smoked on average in the past 5 years. The answer options were: (0) none, (1) a few cigarettes or less a week, (2) 1–5 cigarettes a day, (3) about half a pack a day, (4) about one pack a day, and (5) more than one pack a day; and marijuana use – participants were asked how often they used marijuana in the past 5 years. The answer options were: (0) never, (1) a few times a year or less, (2) about once a month, (3) several times a month, and (4) once a week or more.

Finally, ERI exploration was measured using three items measuring identity search from the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992; Phinney and Ong, 2007): 1) “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic-racial group, such as its history, traditions, and customs; ” 2) “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic-racial group membership; ” and 3) “In order to learn more about my ethnic-racial background, I have often talked to other people about my ethnic/racial group.” The answer options were measured on a 4-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) “strongly disagree” to (4) “strongly agree.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.68, 0.72, 0.73, and 0.72 at the four respective timepoints. Participants were divided into two groups based on whether their mean ERI exploration score from late adolescence (T2) through the early thirties (T5) was at/below (low) or above (high) the median ERI exploration mean score.

Control variables included race/ethnicity (Black or Latina); parental socioeconomic disadvantage in late adolescence or T2 (i.e., sum of four indicators of having less than high school education and being unemployed for mother and father); and SRBs at emerging adulthood or T3 (i. e., multiple sex partners in the last month, sex with someone just met/did not know, and sex with untested partners).

2.3. Analytic plan

As a first step, we examined the distribution of key measures of interest in the overall sample and stratified by ERI exploration group and assess bivariate associations using independent samples t-test and chi-squared test of association, as appropriate. Then, to examine the hypothesized pathway from perceived ethnic-racial discrimination to SRBs in EIE exploration, we used Mplus (Version 6) to perform multigroup structural equation modeling (Muthén and Muthén, 2010) and obtain coefficient estimates, test statistics, and associated significance values. For each latent construct of perceived ethnic-racial discrimination, affective distress, victimization, substance use, and SRBs, we simultaneously assessed how well the stated scales or items load onto each domain. The Mplus Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were used to assess the fit of the model (Byrne, 1998; Kelloway, 1998; Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, 2000; Muthén and Muthén, 2010) To determine if pathways between the high and low ERI exploration groups were significantly different, we tested a series of models with constraints on each path and compared the difference in the chi-squared test statistic from the constrained and unconstrained models with a single-df chi-squared test.

We additionally examined alternative models with direct pathways from perceived ethnic-racial discrimination, affective distress, and victimization to SRBs and perceived ethnic-racial discrimination to victimization, as well as reciprocal effects for the path from affective distress to victimization.

3. Results

Our analytic sample included 492 women. Fifty-four percent (n = 267) of the participants self-identified as Black; the remaining 46.7% (n = 225) self-identified as Latina. With respect to the study outcome, SRBs in the early thirties (T5), 8.9% (n = 44) reported having had more than one sexual partner in the past 6 months, 28.0% (n = 138) reported having had sex with someone they had just met, and 39.6% (n = 195) reported having had sex with someone whose HIV status they did not know. Around half of the 492 women (n =257) were classified as having high ERI exploration.

The distribution of all measures in model are provided in Table 1 for the overall sample as well as stratified by ERI exploration. Several differences by ERI exploration emerged. Women with higher levels of ERI exploration reported higher levels of experiences of discrimination (p = 0.003) and anger at discrimination (p = 0.006) at T2 and higher levels of coerced sex (p = 0.018) at T4 when compared with lower levels of ERI exploration. In contrast, they reported lower levels of depressive mood (p = 0.037) at T3, lower rates of sex with untested partner (p = 0.010) at T5, and lower parental socioeconomic disadvantage (p < 0.001) at T2 than women with low ERI exploration. Finally, Black women were more prevalent in the high ERI exploration group and Latinas were more prevalent in the low ERI exploration group, relative to their composition in the overall sample (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Distribution of study measures overall and stratified by ERI exploration among Black and Latina women, n = 492, Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, New York City, 1994–2013.

| Measures | All, mean (SD) | ERI Exploration, mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| (n = 492) | Low (n = 235) | High (n = 257) | TS | |

|

| ||||

| ERI Exploration | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.3) | – |

| Perceived discrimination (T2) | ||||

| Experiences of discrimination | 4.9 (2.0) | 4.7 (1.8) | 5.2 (2.2) | 2.94† |

| Anger at discrimination | 6.8 (3.6) | 6.3 (3.4) | 7.2 (3.8) | 2.75† |

| Affective distress (T3) | ||||

| Depressive mood | 14.9 (4.2) | 15.3 (4.6) | 14.5 (3.9) | −2.09* |

| Anxiety | 6.0 (2.4) | 6.1 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.3) | −0.95 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 8.3 (2.8) | 8.5 (3.0) | 8.1 (2.7) | −1.61 |

| Victimization (T4) | ||||

| Violent victimization | 2.0 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.5) | −0.59 |

| Experienced coerced sex, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 40 (13.4) | 14 (9.0) | 26 (18.3) | 5.57* |

| No | 258 (86.6) | 142 (91.0) | 116 (81.7) | |

| Substance use in past 5 years (T5) | ||||

| Alcohol use | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | −0.62 |

| Tobacco use | 0.7 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.4) | −0.52 |

| Marijuana use | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.9) | −1.14 |

| Sexual risk behaviors (T5) | ||||

| Multiple partners in past 6 months, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 44 (8.9) | 23 (9.8) | 21 (8.2) | 0.39 |

| No | 448 (91.1) | 212 (90.2) | 236 (91.8) | |

| Sex with just met partner, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 138 (28.0) | 61 (26.0) | 77 (30.0) | 0.98 |

| No | 354 (72.0) | 174 (74.0) | 180 (70.0) | |

| Sex with untested partner, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 195 (39.6) | 107 (45.5) | 88 (34.2) | 6.54† |

| No | 297 (60.4) | 128 (54.5) | 169 (65.8) | |

| Control measures | ||||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 23.10‡ | |||

| Black | 267 (54.3) | 101 (43.0) | 166 (64.6) | |

| Latina | 225 (45.7) | 134 (57.0) | 91 (35.4) | |

| Parental socioeconomic disadvantage (T2), count (range 0–4) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.2) | −3.91‡ |

| Prior sexual risk behaviors (T3), count (range 0–3) | 0.9 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | −1.79 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

We tested the measurement model, as well as the structural model controlling for the race/ethnicity, parental socioeconomic disadvantage, and prior SRBs. All factor loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.05), except sex with untested partner, p = 0.08. The decision to retain this variable in the measurement model hinged on theoretical considerations. The parameter estimates for the hypothesized multigroup SEM (see Fig. 1) are presented in Table 2. The CFI was 0.93, the RMSEA was 0.03, and the SRMR was 0.09, which indicated a good model fit.

Table 2.

Results from Multigroup Structural Equation Model Estimating Pathway from Perceived Ethnic-Racial Discrimination to Sexual Risk Behaviors among Black women and Latinas, n = 492, Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, New York City, 1994–2013.

| ERI exploration | Model Estimates, β (z-score) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Path 1 | Path 2 | Path 3 | Path 4 | Indirect Effect | |

|

| |||||

| High | 0.17 (1.60) | 0.09 (3.78)‡ | 0.59 (2.98)† | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.00 (0.18) |

| Low | 0.68 (4.64)‡ | 0.09 (3.56)‡ | 0.42 (2.16)* | 1.06 (3.47)‡ | 0.03 (2.17)* |

| Moderation effect | 16.31‡ | 1.50 | 1.16 | 2.37 | – |

Notes.

p < 0.05

p<0.01

p < 0.001.

Paths 1–3 adjusted for ethnicity and parental socioeconomic disadvantage.

Path 4 adjusted for ethnicity, parental socioeconomic disadvantage, and prior sexual risk behavior.

CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.09.

For the participants who scored low on ERI exploration, all four paths were statistically significant. Perceived ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence (T2) was related to increased affective distress (β = 0.68, z = 4.64, p < 0.001) in emerging adulthood (T3), which was, in turn, related to more experiences of victimization (β = 0.09, z = 3.56, p < 0.01) in young adulthood (T4). Victimization was associated with greater use of substances (β = 0.42, z = 2.16, p < 0.05) in the early thirties (T5). Substance use in the early thirties was associated with more SRBs (β = 1.06, z = 3.47, p < 0.001) in the early thirties (T5). The indirect effect of ethnic-racial discrimination (T2) on SRBs (T5) via affective distress (T3), victimization (T4), and substance use (T5) was statistically significant among women low on ERI exploration (β = 0.03, z = 2.17, p < 0.05).

On the other hand, among those high on ERI exploration, only paths 2 and 3 were statistically significant. Perceived ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence (T2) was not related to increased affective distress in emerging adulthood (T3) and substance use in the early thirties (T5) was not associated with SRBs in the early thirties. However, affective distress in emerging adulthood (T3) was related to more experiences of victimization (β = 0.09, z = 3.78, p < 0.01) in young adulthood (T4). Also, victimization in young adulthood was associated with greater use of substances (β = 0.59, z = 2.98, p < 0.01) in the early thirties (T5). The indirect effect of ethnic-racial discrimination (T2) on SRBs (T5) via affective distress (T3), victimization (T4), and substance use (T5) was not statistically significant among women high on ERI exploration.

With respect to the modification effect of ERI exploration on the path from ethnic-racial discrimination to affective distress, our hypothesis was confirmed (χ2 =16.31, df =1, p < 0.001). For participants with high ERI exploration, ethnic-racial discrimination did not have a significant relationship with their levels of affective distress, while those with low ERI exploration experienced greater affective distress in emerging adulthood (T3) from exposure to ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence (T2). ERI exploration level was not a significant modifier for any other pathways.

We also examined alternative models with direct pathways from perceived ethnic-racial discrimination to SRBs, affective distress to SRBs, and victimization to SRBs. None of these pathways were statistically significant. The model examining reciprocal effects for the path from affective distress to victimization (i.e., putting victimization as an antecedent to affective distress) did not converge.

4. Discussion

The current study examined a longitudinal sequence of exposures and risk factors for SRBs from late adolescence to the early thirties among Black women and Latinas who reported higher vs. lower levels of ERI exploration, operationalized via stratification of the sample into high and low ERI exploration scores using a median split. The study employed constructs and hypotheses derived from the Theory of Gender and Power (Wingood and DiClemente, 2000, 2002; Wingood et al., 2011) and added ethnic-racial discrimination as an important exposure for Black women and Latinas.

The results supported our hypotheses by suggesting a pathway from exposure to ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence to SRBs in the early thirties among young Black women and Latinas at lower levels of ERI exploration. Also, as hypothesized, ERI moderated the association between ethnic-racial discrimination and affective distress: among women at higher levels of ERI exploration the path between the two constructs was not statistically significant. An additional finding was that the path between substance use and SRBs was not statistically significant among women with higher ERI exploration.

The findings suggest that, among Black women and Latinas low in ERI exploration, ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence may trigger a sequence of exposures and risk factors (i.e., affective distress, victimization, and substance use) over the course of emerging and young adulthood that is followed by a greater engagement in SRBs in the thirties. The results thus contribute to the empirical literature on how constructs within the Theory of Gender and Power (both distal and proximal to SRBs) are related to one another and to SRBs over time.

Importantly, this analysis adds ethnic-racial discrimination to the Theory of Gender and Power. Ethnic-racial discrimination can be considered an exposure within the Sexual Division of Labor, as it is external to individuals and operates at the structural, institutional, as well as at the interpersonal levels and influences access to socioeconomic opportunities for Black women and Latinas (Browne, 1999; Williams et al., 2010; Phelan and Link, 2015). This is a critical addition, as ethnic-racial discrimination is ubiquitous in the lives of Black women and Latinas (Moradi and Risco, 2006; Lewis et al., 2017; American Psychological Association, 2019; Williams et al., 2019). Furthermore, this research illuminates a pathway of exposures preceding SRBs among Black women and Latinas low in ERI exploration, thus adding a longitudinal dimension to the theory, as well as suggesting possible foci for prevention and intervention within this “chain of risks” (Kuh et al., 2009; Harris and Schorpp, 2018).

The identified pathway between perceived ethnic-racial discrimination and affective distress among Black women and Latinas low on ERI exploration is consistent with previous research, which has found that perceived ethnic-racial discrimination is related to elevated levels of psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety in Black women and Latinas (Kwate et al., 2003; Moradi and Risco, 2006; Soto et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2015). Experiencing psychological distress, in turn, can render women, including Black women and Latinas, vulnerable to experiencing violence, especially in the context of intimate partner violence (Finkelhor and Asdigian, 1996; Maldonado et al., 2022). Perceived weakness, psychological or physical, is a characteristic that renders women more vulnerable to sexual and violent victimization (Himelein, 1995; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen and Livingston, 2007; Iverson et al., 2011). For example, Cougle et al. (2009) found that emotional reactions to traumatic events are risk factors for later exposure to other traumatic events in women. Women who are depressed may also be less able to detect risky situations because their cognitive and affective capacities are compromised by depression (Pahl et al., 2020). Previous research on this association has not focused much on Black women and Latinas; this study is beginning to address this gap. Importantly, future research should examine the specific gendered and racialized dynamics involved in the associations of psychological distress and exposure to violence among Black women and Latinas (Szymanski and Stewart, 2010).

Exposure to violence in young adulthood (the late 20s) was associated with greater substance use in the early thirties, replicating previous research that finds a relationship between violent victimization and substance use among Black women and Latinas (Hankin et al., 2010; Meyers et al., 2018). Extant research suggests that the links between violence exposure and substance use may, in part, be explained by posttraumatic stress and the resulting need to regulate negative emotions (Curtis-Boles and Jenkins-Monroe, 2000; Hankin et al., 2010; Miranda et al., 2002; Stevens-Watkins et al., 2012; Ullman et al., 2013). Our findings confirm this relationship between violence exposure (a traumatic experience) and substance use in Black women and Latinas. However, we did not assess posttraumatic stress in this study. Future research should examine how posttraumatic stress may link these two domains among Black women and Latinas who are exposed to a myriad of expressions of gendered racism, including violence (Lewis et al., 2017; Vance et al., 2022; Rosenthal and Lobel, 2020).

Substance use, in turn, has been identified as a behavioral risk factor for SRBs by the Theory of Gender and Power (Wingood and DiClemente, 1998; Pahl et al., 2019). While Black women and Latinas generally engage in less substance use than, for example, White women, the associated consequences tend to be more severe due to structural factors, such as gendered racism (Zapolski et al., 2014). The sexually disinhibiting effects of alcohol and drug use are contributing factors in the transmission and acquisition of HIV and other STIs (Stall et al., 1986; Flavin and Frances, 1987; Buffum, 1988).

Our finding that ERI exploration attenuated the longitudinal association between exposure to ethnic-racial discrimination in late adolescence and affective distress in young adulthood confirms that ERI exploration may constitute a resilience asset in Black women and Latinas during young adulthood. It also offers some explanation for why some women who are exposed to ethnic-racial discrimination experience extremely negative consequences, while others seem better able to cope with this negative influence on their lives. Ethnic-racial discrimination at various levels (e.g., personal, interpersonal, institutional) is a fact of life for people of color, particularly Black people, living in the U.S. (Ahmed et al., 2007; Chae et al., 2017; Williams, 2018). Not only has the severity and frequency of perceived ethnic-racial discrimination been found to vary by ethnic-racial groups, gender, and individuals, its consequences also seem to vary considerably (Chou et al., 2012; Otiniano Verissimo et al., 2014; Chae et al., 2017). Our findings provide preliminary evidence that ERI exploration is likely introducing variability into this relationship.

While most research on the protective effect of ERI has focused on its affective dimensions (but see Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), we chose to focus on exploration because it implies a questioning of ethnic-racial stereotypes or “controlling images” (Collins, 2000, p.5) about one’s group(s) (e.g., Cross, 1995). Young adult Black women and Latinas who think about the social and structural implications of their ethnic-racial group memberships are likely conscious of the prevalence of racism (and sexism) and gendered racist stereotypes about their groups (Cross et al., 1998). This awareness may make these women less likely to internalize the devaluation implied in ethnic-racial discrimination and, thereby, make them more resilient to experiencing affective distress as a result of discrimination (Freire, 1973).

Research among adolescents has found a relationship between high levels of ERI exploration and increased vulnerability to ethnic-racial discrimination (e.g., Greene et al., 2006). From a developmental perspective, it is possible that during adolescence, when individuals first engage in an identity search (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1980; Umaña-Taylor, 2018), high levels of ERI exploration can introduce a sense of insecurity for some, because resolution has not yet been achieved (Marcia, 1980; Phinney, 1990). However, among emerging and young adults, ERI exploration may reflect critical consciousness, which implies the awareness of the social and structural nature of oppression (including sexism and racism) that enables people to question the status quo and take action against oppressive political and social forces (Freire, 1973; Watts et al., 2011). This state of consciousness, which in contemporary culture is often referred to as being “woke” (Steinmetz, 2017; Whitaker, 2017; Wilson, 2017) may insulate Black women and Latinas against internalizing racist discrimination (Freire, 1973). More research exploring the potential protective impact of ERI exploration and critical consciousness over the life course is needed, given the higher morbidity and mortality burden shouldered by Black women and Latinas (Petersen et al., 2019).

Latinas in our sample reported higher levels of ethnic-racial discrimination and anger at discrimination than Black women. Several structural and cultural factors may have contributed to this finding. First, Black women in this study may have underreported incidents of ethnic-racial discrimination, possibly as a coping mechanism to minimize its impact on mental health (Liao et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2017). Second, many Latinas are immigrants and may face a compounded burden of discrimination due to their immigration and ethnic-racial minoritized statuses, as well as language barriers (Otiniano Verissimo et al., 2014). Third, the majority of the women in this study identified as Puerto Rican. Research documents that Puerto Rican-born persons residing in the U.S. experience greater structural adversity than other Latinx groups, including socioeconomic disadvantage and poverty (Suro, 1999; Suarez-Orozco and Páez, 2002), acculturative stress, and health problems, including depression, which we also found in this research (Dominguez et al., 2015; Aranda and Rivera, 2016; Arroyo-Johnson et al., 2016; Burgos et al., 2017; Cuevas et al., 2019). In addition, Puerto Ricans in the U.S. have long been stereotyped as living within a “culture of poverty” (Burgos et al., 2017) and have been portrayed both by research and in popular culture as overly emotional, irrational, and impulsive, especially Puerto Rican women (Suro, 1999). These gendered racist stereotypes are particularly salient in the Northeast, where our sample was drawn (Aranda and Rivera, 2016). In sum, Latinas in this sample may have experienced discrimination related to the intersection of their minoritized and racialized statuses and other dimensions of structural adversity (Bekteshi et al., 2015).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our research examined constructs from three interrelated domains of the Theory of Gender and Power. To our knowledge, this is the first study informed by this theory to examine a longitudinal pathway to SRBs in Black women and Latinas. Another strength of this study is the integration of interpersonal, institutional, and structural ethnic-racial discrimination, an important exposure that is ubiquitous in the lives of Black women and Latinas, into the Theory of Gender and Power. Not including this phenomenon among the exposures assessed in the model would have been an important oversight of this social determinant of Black women’s and Latinas’ health. Third, our model illuminates a temporal sequence of mechanisms through which ethnic-racial discrimination may precede SRBs among Black and Latina women, thus pointing to a range of potential targets for intervention along this sequence. Further, our results suggest that higher levels of ERI exploration may be useful in mitigating the deleterious effects of ethnic-racial discrimination on women’s mental health.

One limitation of this research concerns the self-report nature of our measures. Experiencing violence, in particular sexual coercion, is underreported in community-based studies (Conway et al., 1994; Sable et al., 2006). Thus, it is likely that there is a greater prevalence of victimization among young urban Black women and Latinas than what is reported. However, this would not necessarily have altered the relationships we identified in this study. Further, we were not able to assess changes in measures over time and their lagged effects on the relationships of interest due to data and sample size limitations. This is an important area for future work. Another limitation is the lack of control of discrimination measured contemporaneously, which may also have affected sexual risk behaviors contemporaneously. Finally, our existing measures did not allow us to assess Black women’s and Latinas’ experiences of discrimination in an intersectional way (Collins, 1991; Crenshaw, 1989). Black women and Latinas’ lived experiences are influenced simultaneously by racism and sexism that pervades all social spheres. These interlocking forms of oppression, namely, gendered racism, therefore, need to be measured explicitly and examined in relationship to Black women’s and Latinas’ health and health behaviors (Cole, 2009; Lewis et al., 2017).

5. Conclusions

This study makes an important contribution to theory by incorporating ethnic-racial discrimination, a ubiquitous exposure for Black women and Latinas in the U.S., to the Theory of Gender and Power. This research further sheds light on the mechanisms by which experiences throughout young adulthood explain observed disparities in the prevalence of HIV and STIs among Black women and Latinas. The study findings underscore the “long arm” of ethnic-racial discrimination, as this adolescent exposure triggered a chain of risk that led to SRBs in adulthood in Black women and Latinas low in ERI exploration. Importantly, high ERI exploration appeared to disrupt this chain of risk, possibly as it may reflect critical consciousness and an increased awareness of systems of oppression. Our findings, therefore, highlight a need for further research into the mechanisms through which ERI exploration and, potentially, critical consciousness, as protective factors, can impact health behaviors and outcomes. Additionally, study results are important to applied practice as they could inform the development and/or improvement of SRB prevention programs among Black women and Latinas. Fostering the exploration of women’s ethnic-racial identities along with encouraging ethnic-racial pride and raising consciousness about the social and structural nature of racism (and sexism) throughout young adulthood may help shield against experiences of ethnic-racial discrimination to which young women of color are exposed at high levels.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the following grants from the NIH, awarded to Drs. Judith Brook and Kerstin Pahl: research grant R01 DA035408 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and research grant R01 CA084063 from the National Cancer Institute. We would like to thank our colleagues at the Center for Research on Cultural and Structural Equity in Behavioral Health (CCASE.org) and at the Disparities Research Collective of the Department of Psychiatry at NYU Grossman School of Medicine for their intellectual supoprt of this research.

Footnotes

Declarations of competing interest

None.

Credit

KP: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; SW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; AC: Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; CFL: Writing - review & editing; HML: Writing - review & editing.

References

- Adimora AA, et al. , 2011. Concurrent partnerships, nonmonogamous partners, and substance use among women in the United States. Am. J. Publ. Health 101 (1), 128–136. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AT, Mohammed SA, Williams DR, 2007. Racial discrimination & health: pathways & evidence. Indian J. Med. Res. 126 (4), 318–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, 2019. ‘Stress in America: Stress and Current events.’, Stress in America™ Survey (November), pp. 1–47. Available at: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2013/stress-report.pdf.

- Anastario MP, Larrance R, Lawry L, 2008. Using mental health indicators to identify postdisaster gender-based violence among women displaced by hurricane Katrina. J. Wom. Health 17 (9), 1437–1444. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0694. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda E, Rivera FI, 2016. Puerto Rican families in central Florida: prejudice, discrimination, and their implications for successful intergration. Women, Gend. Fam. Color 4, 57–85. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Johnson C, et al. , 2016. Racial and ethnic heterogeneity in self-reported diabetes prevalence trends across hispanic subgroups, national health interview survey, 1997–2012. Prev. Chronic Dis. 13, E10. 10.5888/pcd13.150260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, et al. , 2017. The oppression of Latina mothers: experiences of exploitation, violence, marginalization, cultural imperialism, and powerlessness in their everyday lives’, violence against women. SAGE Publ. Inc; 24 (8), 879–900. 10.1177/1077801217724451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekteshi V, Van Hook M, Matthew L, 2015. Puerto Rican-born women in the United States: contextual approach to immigration challenges. Health Soc. Work 40 (4), 298–306. 10.1093/hsw/hlv070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave FZ, et al. , 1994. The influence of africentric values, self-esteem, and black identity on drug attitudes among african American fifth graders: a preliminary study. J. Black Psychol. 20 (2), 143–156. 10.1177/00957984940202004. Inc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, et al. , 1992. ‘African-American and Puerto Rican Drug Use: Personality, Familial, and Other Environmental Risk factors.’, Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, pp. 417–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Hamburg BA, et al. , 1992. ‘Sequences of Drug Involvement in African-American and Puerto Rican adolescents.’, Psychological Reports. US: Psychological Reports, pp. 179–182. 10.2466/PR0.71.5.179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, et al. , 1998. Drug use among African Americans: ethnic identity as a protective factor. Psychol. Rep. 83 (3 Pt 2), 1427–1446. 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3f.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, et al. , 2004. Illicit drug use and risky sexual behavior among african American and Puerto Rican urban adolescents: the longitudinal links. J. Genet. Psychol.: Res. Theor. Hum. Develop. 203–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Pahl K, 2005. The protective role of ethnic and racial identity and aspects of an Africentric orientation against drug use among African American young adults. J. Genet. Psychol. 166 (3), 329–345. 10.3200/GNTP.166.3.329-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, et al. , 2006. Depressed mood as a risk factor for unprotected sex in young people. Australas. Psychiatr. : Bull. Roy. Australi. New Zealand College Psychiat. 14 (3), 310–312. 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne I, 1999. Introduction: Latinas and african American women in the U.S. Labor market. In: Browne I. (Ed.), Latinas and African American Women at Work. Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 1–32 (Race, Gender, and Economic Inequality). http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610440943.4. [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani H, Hearld KR, Chavez-Yenter D, 2015. Generalized Anxiety Disorder in racial and ethnic minorities: a case of nativity and contextual factors. J. Affect. Disord. 175, 275–280. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffum J, 1988. Substance abuse and high-risk sexual behavior: drugs and sex: the dark side. J. Psychoact. Drugs 20 (2), 165–168. 10.1080/02791072.1988.10524489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos G, Rivera FI, Garcia MA, 2017. Contextualizing the relationship between culture and Puerto Rican health: towards a place-based framework of minority health disparities. Centro J. 29 (3), 36–73. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, 1998. Structural Equation Modeling with Lisrel, Prelis, and Simplis: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, first ed. Psychology Press. 10.4324/9780203774762 . Available at: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso A, et al. , 2021. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: the effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S. Prev. Med. 145, 106422. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso A, DiClemente RJ, 2019. Factors associated with alcohol use disorder among urban non-Hispanic Black women. In: APHA’s 2019 Annual Meeting and Expo (Philadelphia, PA). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021. HIV surveillance report vol.32. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, et al. , 2017. The role of racial identity and implicit racial bias in self-reported racial discrimination: implications for depression among african American men. J. Black Psychol. 43 (8), 789–812. 10.1177/0095798417690055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez EL, Oetting ER, 1994. Dropout and delinquency: Mexican-American and Caucasian non-Hispanic youth. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 23 (1), 47–55. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2301_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H-L, Mallinckrodt B, 2015. Racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol problems in a longitudinal study of Hispanic/Latino college students. J. Counsel. Psychol. 38–49. 10.1037/cou0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T, Asnaani A, Hofmann SG, 2012. Perception of racial discrimination and psychopathology across three U.S. ethnic minority groups. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 18 (1), 74–81. 10.1037/a0025432, 2011/10/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun H, et al. , 2015. Does the experience of discrimination affect health? A cross-sectional study of Korean elders. Asia Pac. J. Publ. Health 27 (2), NP2285–N2295. 10.1177/1010539513506602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, et al. , 2015. Everyday discrimination and mood and substance use disorders: a latent profile analysis with African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Addict. Behav. 40, 119–125. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER, 2009. Intersectionality and Research in Psychology. ‘, American Psychologist, pp. 170–180. 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH, 1991. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH, 2000. Gender, black feminism, and black political economy. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 568, 41–53. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1049471. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Conway T, et al. , 1994. Prevalence of violence victimization among patients seen in an urban public hospital walk-in clinic. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 9 (8), 430–435. 10.1007/BF02599057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KE, Stark R, 2019. Regional, structural, and demographic predictors of violent victimization: a cross-national, multilevel analysis of 112 countries. Int. Rev. Vict. 26 (2), 234–252. 10.1177/0269758019869108. SAGE Publications Ltd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ND, et al. , 2014. Community impact of pharmacy-randomized intervention to improve access to syringes and services for injection drug usersNo Title. Health Educ. Behav. 41 (4), 397–405. 10.1177/1090198114529131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW, 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine. Femin. Theor. Antiracist Polit. 1, 139–167. University of Chicago Legal Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Resnick H, Kilpatrick DG, 2009. A prospective examination of PTSD symptoms as risk factors for subsequent exposure to potentially traumatic events among women. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118 (2), 405–411. 10.1037/a0015370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE Jr., 1991. Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American Identity. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE Jr., 1995. In search of Blackness and Afrocentricity: the psychology of Black identity change. In: Harris HW., Blue HC., Griffith EEH. (Eds.), Racial and Ethnic Identity: Psychological Development and Creative Expression, pp. 53–72. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Parham TA, Helms JE, 1998. Nigrescence revisited: theory and research. In: African American Identity Development. Cobb & Henry; Hampton, VA, p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, et al. , 2019. The association between perceived discrimination and allostatic load in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Psychosom. Med. 81 (7), 659–667. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis-Boles H, Jenkins-Monroe V, 2000. Substance abuse in African American women. J. Black Psychol. 450–469. 10.1177/0095798400026004007. US: Sage Publications. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DePadilla L, et al. , 2011. Condom use among young women: modeling the theory of gender and power. Health Psychol. 310–319. 10.1037/a0022871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Savitz KL, 1999. The SCL-90-R, brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In: Maruish ME. (Ed.), The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 679–724. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos A, Siguaw J, 2000. ‘Introducing LISREL’, London 10.4135/9781849209359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez K, et al. , 2015. Vital signs: leading causes of death, prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and use of health services among Hispanics in the United States - 2009–2013. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Week. Rep. 64 (17), 469–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, et al. , 2005. Scope of HIV risk and co-occurring psychosocial health problems among young adults: violence, victimization, and substance use. J. Adolesc. Health 36 (5), 401–409. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH, 1968. Identity and identity diffusion. In: Gordon C., Gergen K. (Eds.), The Self in Social Interaction. Vol. I: Classic and Contemporary Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Asdigian NL, 1996. Risk factors for youth victimization: beyond a lifestyles/routine activities theory approach. Violence Vict. 11 (1), 3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavin DK, Frances RJ, 1987. Risk-taking behavior, substance abuse disorders, and the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Adv. Alcohol Subst. Abuse 6 (3), 23–32. 10.1300/J251v06n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P, 1973. Education for Critical Consciousness, vol. 1. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, et al. , 2004. Perceived discrimination and substance use in african American parents and their children: a panel study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86 (4), 517–529. 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson LE, Leitenberg H, 2001. The impact of child sexual abuse and stigma on methods of coping with sexual assault among undergraduate women. Child Abuse Negl. 25 (10), 1343–1361. 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00279-4. England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez FR, Benuto LT, Casas JB, 2020. Prevalence of interpersonal violence among Latinas: a systematic review.’, trauma, violence & abuse. United States 21 (5), 977–990. 10.1177/1524838018806507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JR, et al. , 2016. The mediating role of internalized racism in the relationship between racist experiences and anxiety symptoms in a Black American sample. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 22 (3), 369–376. 10.1037/cdp0000073. Educational Publishing Foundation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K, 2006. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Dev. Psychol. 42 (2), 218–236. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin A, et al. , 2010. Correlation between intimate partner violence victimization and risk of substance abuse and depression among african-American women in an urban emergency department. West. J. Emerg. Med. 11 (3), 252–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Schorpp KM, 2018. Integrating biomarkers in social stratification and health research’, annual Review of sociology. Ann. Rev. 44 (1), 361–386. 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelein MJ, 1995. Risk factors for sexual victimization in dating: a longitudinal study of college women. Psychol. Women Q. 19 (1), 31–48. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00277.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton HE, et al. , 2004. Depression and HIV risk behaviors among patients in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Am. J. Psych. USA 161 (5), 912–914. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV Epidemiology Program, 2021. HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2020. New York, NY. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/hiv-surveillance-annualreport-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, et al. , 2011. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 79 (2), 193–202. 10.1037/a0022512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jané-Llopis E, Matytsina I, 2006. Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: a review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug Alcohol Rev. Australia 25 (6), 515–536. 10.1080/09595230600944461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK, 1998. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling : a Researcher’s Guide. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, et al. , 2009. Depression, sexually transmitted infection, and sexual risk behavior among young adults in the United States. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 163 (7), 644–652. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, et al. , 1998. Victimization, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use/abuse among women. In: Wetherington CL., Roman AB. (Eds.), Drug Addiction Research and the Health of Women. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, pp. 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben Shlomo Y, Ezra S, 2009. A life course approach to chronic disease Epidemiology. Oxford Schol. Online. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198578154.001.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwate NOA, et al. , 2003. Experiences of racist events are associated with negative health consequences for African American women’, Journal of the National Medical Association. Natl. Med. Assoc. 95 (6), 450–460. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12856911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL, Rezey ML, 2018. Victimization trends and correlates: macro- and microinfluences and new directions for research’, annual Review of criminology. Ann. Rev. 1 (1), 103–121. 10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Neblett EW Jr., Jackson V, 2015. The role of optimism and religious involvement in the association between race-related stress and anxiety symptomatology. J. Black Psychol. 41 (3), 221–246. 10.1177/0095798414522297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, et al. , 2017. Applying intersectionality to explore the relations between gendered racism and health among Black women. J. Counsel. Psychol. USA 64 (5), 475–486. 10.1037/cou0000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KYH, Wei M, Yin M, 2020. The misunderstood schema of the strong black woman: exploring its mental health consequences and coping responses among african American women. Psychol. Women Q. 44 (1), 84–104. 10.1177/0361684319883198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C, 2002. ‘Women, sex, and HIV: social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychol. Bull. 851–885. 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado AI, et al. , 2022. Racial discrimination, mental health symptoms, and intimate partner violence perpetration in Black adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 10.1037/ccp0000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia J, 1980. Identity in adolescence. In: Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe BE, et al. , 2018. Childhood abuse and adulthood IPV, depression, and high-risk drinking in Latinas. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 39 (12), 1004–1009. 10.1080/01612840.2018.1505984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCree DH, et al. , 2020. Exploring changes in racial/ethnic disparities of HIV diagnosis rates under the “ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for America” initiative’, public health reports. SAGE Publ. Inc; 135 (5), 685–690. 10.1177/0033354920943526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, et al. , 2019. Vital signs: estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention - 25 states, 2015–2017’, MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Centers Disease Contr. Prevent. 68 (44), 999–1005. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ, 2003. The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: an empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 23 (4), 537–571. 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers JL, et al. , 2018. Childhood Interpersonal Violence and Adult Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Disorders: Variation by Race/ethnicity?, pp. 1540–1550. 10.1017/S0033291717003208. Psychological Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda RJ, et al. , 2002. Sexual assault and alcohol use: exploring the self-medication hypothesis.’, Violence and victims. United States 17 (2), 205–217. 10.1891/vivi.17.2.205.33650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Risco C, 2006. Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o american persons. J. Counsel. Psychol. 53 (4), 411–421. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski K, 2003. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J. Health Soc. Behav. 44, 318–331. 10.2307/1519782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2010. Mplus User’s Guide, sixth ed. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, et al. , 1999. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of southeast asian refugees in Canada. J. Health Soc. Behav. 40 (3), 193–207. 10.2307/2676348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr ST, et al. , 1994. Depressive symptoms and risk factors for HIV acquisition among Black women attending urban health centers in Baltimore. AIDS Educ. Prev. 6 (3), 230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otiniano Verissimo AD, et al. , 2014. Discrimination and substance use disorders among Latinos: the role of gender, nativity, and ethnicity. Am. J. Publ. Health 104 (8), 1421–1428. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, et al. , 2019. Sexual risk behaviors among Black and Puerto Rican women in their late thirties: a brief report. J. Immigr. Minority Health 21 (6), 1432–1435. 10.1007/s10903-019-00877-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, et al. , 2021a. Longitudinal predictors of male sexual partner risk among Black and Latina women in their late thirties: ethnic/racial identity commitment as a protective factor. J. Behav. Med. 44 (2), 202–211. 10.1007/s10865-020-00184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N, 2006. Longitudinal Trajectories of Ethnic Identity Among Urban Black and Latino Adolescents. ‘, Child Development, pp. 1403–1415. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, et al. , 2020. Trajectories of violent victimization predicting PTSD and comorbidities among urban ethnic/racial minorities. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 39–47. 10.1037/ccp0000449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, et al. , 2021b. The lasting effects of racism-related stress: a qualitative study. In: APHA Annual Meeting and Expo. Available at: https://apha.confex.com/apha/2021/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/505660. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L, 2009. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 135 (4), 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen EE, et al. , 2019. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths - United States, 2007–2016. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Week. Rep. 68 (35), 762–765. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, 2015. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health?’, annual Review of sociology. Ann. Rev. 41 (1), 311–330. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, 1989. Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 9 (1–2), 34–49. 10.1177/0272431689091004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, 1990. Ethnic Identity in Adolescents and Adults: Review of Research. Psychological Bulletin. Association, pp. 499–514. 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, 1992. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: a new scale for use with diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 7 (2), 156–176. 10.1177/074355489272003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, 1993. A Three-Stage Model of Ethnic Identity Development in adolescence.’, Ethnic identity: Formation and Transmission Among Hispanics and Other Minorities. State University of New York Press (SUNY series, United States Hispanic studies.), Albany, NY, pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong AD, 2007. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: current status and future directions. J. Counsel. Psychol. 54 (3), 271–281. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Respress BN, Amutah-Onukagha NN, Opara I, 2018. The effects of school-based discrimination on adolescents of color sexual health outcomes: a social determinants approach.’, Social work in public health. United States 33 (1), 1–16. 10.1080/19371918.2017.1378953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, et al. , 2012. From racial discrimination to risky sex: prospective relations involving peers and parents. Dev. Psychol. 48 (1), 89–102. 10.1037/a0025430, 2011/09/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, Lobel M, 2020. Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethn. Health 25 (3), 367–392. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1439896. England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, et al. , 2006. Barriers to reporting sexual assault for women and men: perspectives of college students. J. Am. Coll. Health : J ACH 55 (3), 157–162. 10.3200/JACH.55.3.157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Newton-Levinson A, Swartzendruber AL, 2020. In: Hussen SA. (Ed.), Racial Disparities in STIs Among Adolescents in the USA BT - Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 31–42. 10.1007/978-3-030-20491-4_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K, 2002. Factors influencing HIV/AIDS in women of color. Publ. Health Rep. 117, S151–S156. Washington, D.C. : 1974. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12435839. Suppl(Suppl 1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LM, et al. , 1997. Ethnic identity as a moderator of psychosocial risk and adolescent alcohol and marijuana use: concurrent and longitudinal analyses. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse 6 (1), 21–47. 10.1300/J029v06n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, et al. , 2003. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 44 (3), 302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN, 2003. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1079–1092. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, 2010. The intersection of violence, substance use, depression, and STDs: testing of a syndemic pattern among patients attending an urban STD clinic. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 102 (7), 614–620. 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]