Abstract

Background:

Next generation sequencing studies have revealed an ever-increasing number of causes for genetic disorders of central nervous system white matter. A substantial number of disorders are identifiable from their specific pattern of biochemical and/or imaging findings for which single gene testing may be indicated. Beyond this group, the causes of genetic white matter disorders are unclear and a broader approach to genomic testing is recommended.

Aim:

This study aimed to identify the genetic causes for a group of individuals with unclassified white matter disorders with suspected genetic aetiology and highlight the investigations required when the initial testing is non-diagnostic.

Methods:

Twenty-six individuals from 22 families with unclassified white matter disorders underwent deep phenotyping and genome sequencing performed on trio, or larger, family groups. Functional studies and transcriptomics were used to resolve variants of uncertain significance with potential clinical relevance.

Results:

Causative or candidate variants were identified in 15/22 (68.2%) families. Six of the 15 implicated genes had been previously associated with white matter disease (COL4A1, NDUFV1, SLC17A5, TUBB4A, BOLA3, DARS2). Patients with variants in the latter two presented with an atypical phenotype. The other nine genes had not been specifically associated with white matter disease at the time of diagnosis and included genes associated with monogenic syndromes, developmental disorders, and developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (STAG2, LSS, FIG4, GLS, PMPCA, SPTBN1, AGO2, SCN2A, SCN8A). Consequently, only 46% of the diagnoses would have been made via a current leukodystrophy gene panel test.

Discussion:

These results confirm the importance of broad genomic testing for patients with white matter disorders. The high diagnostic yield reflects the integration of deep phenotyping, whole genome sequencing, trio analysis, functional studies, and transcriptomic analyses.

Conclusions:

Genetic white matter disorders are genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous. Deep phenotyping together with a range of genomic technologies underpin the identification of causes of unclassified white matter disease. A molecular diagnosis is essential for prognostication, appropriate management, and accurate reproductive counseling.

Keywords: Brain diseases, Phenotype, Genetic testing, High-throughput nucleotide sequencing, Genomics

1. Introduction

Genetic disorders of white matter include the leukodystrophies, which are primary disorders of white matter due to glial cell pathology, and the genetic leukoencephalopathies in which the CNS white matter is affected as a secondary phenomenon with the primary disorder being neuronal, vascular or systemic in origin.(Parikh et al., 2015; van der Knaap and Bugiani, 2017; Vanderver et al., 2020). Unclassified white matter disorders are those conditions for which a specific cause cannot be recognized by the pattern of white matter abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a pathognomonic biochemical or molecular abnormality. Owing to the genetic heterogeneity of this group, broad genetic testing is recommended early in the diagnostic work up (van der Knaap et al., 2019; Vanderver et al., 2020) rather than single gene sequencing or panel testing.

The reported diagnostic yield from genomic sequencing for individuals with presumed genetic white matter disorders ranges from 80% with exome sequencing (ES)(Vanderver et al., 2016) to 85% with genome sequencing (GS)(Helman et al., 2020; Vanderver et al., 2020). MRI pattern recognition and biochemical tests play an important role in diagnosing certain white matter disorders early but should otherwise not delay a genomic sequencing test (Vanderver et al., 2020). Clinical phenotyping is important for identifying this group of disorders, prioritising and interpreting candidate variants, and in guiding the next steps if genomic testing is not informative (Stark et al., 2017).

Collaboration between neurologists, neuroradiologists, clinical and laboratory genetic services as well as researchers contributes to the diagnostic process for individuals with white matter disease via the facilitation of timely genomic testing, phenotyping of patients with atypical or complex phenotypes, and ongoing investigation when initial genomic testing is non-diagnostic. Pathways to diagnosis for patients with unclassified disorders of white matter when initial testing is uninformative include deep phenotyping to re-prioritise variants for curation, extended bioinformatic analysis, transcriptomic analysis, functional studies, data-sharing to resolve variants of uncertain significance, and reanalysis of genomic data over time (Azzariti and Hamosh, 2020; Cummings et al., 2017; Eratne et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2020). These processes and emerging technologies, supported by international research collaboration, play a critical role in improving diagnostic rates for patients with genetic white matter disorders. A timely diagnosis is essential for accurate prognostication, diagnosis and management of comorbidities, psychological adjustment to a condition, reproductive counseling, and delivery of precision therapies.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient phenotyping

Children and adults with white matter disease of presumed genetic aetiology (living and deceased) were referred by Australian and New Zealand neurology and genetic specialists to a leukodystrophy gene discovery project at the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH), Melbourne. Affected individuals or their parents/guardians provided informed consent and the project was approved by the RCH Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Project Number 28097). Individuals attended RCH for clinical review where possible. The following test results were reviewed before enrollment to exclude diagnoses not requiring genomic testing: very long chain fatty acids, lysosomal enzymes, urine organic acids, chromosome microarray and, if relevant to the individual’s phenotype, cytomegalovirus PCR from a neonatal dried blood sample. Some individuals had more extensive investigation prior to referral including tissue biopsies and single gene testing. Two individuals had previous singleton exome sequencing (ES) which was uninformative. Clinical details and MRI images were reviewed for each patient by at least two neurologists (RJL, AV) and a geneticist (CAS). MRI brain and spine images were reviewed for diagnostic patterns using established pattern recognition guidelines (Schiffmann and van der Knaap, 2009; van der Knaap et al., 2019). 36 individuals were initially referred for assessment. Those with a recognizable pattern of MRI abnormalities specific for a monogenic disorder were included if the suspected disorder had been excluded with single gene or genomic testing, as were those with clinical features of a leukodystrophy or genetic leukoencephalopathy and non-specific white matter abnormalities. Ten individuals were excluded as their clinical presentation was consistent with an acquired or genetic static developmental disorder, one of whom was subsequently diagnosed with HNRNPU-related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy from ES and one tested positive for congenital cytomegalovirus from their newborn screening card. A total of 26 individuals from 22 families were enrolled in the study. A case summary for each of these families is provided in Supplementary file 1.

2.2. Genome sequencing (GS)

GS analysis was performed for the proband±affected sibling and both parents as a trio or quad analysis to identify the causative variant (s). For two individuals, only one parent was available, and the analysis was performed as a duo. GS was performed using 2 × 150 nt paired end reads on an Illumina × (Illumina Cambridge Ltd, Little Chesterford UK). Read alignment was performed using BWA-mem; variant calling of the nuclear genome was performed using GATK HaplotypeCaller v3.7, BCFtools was used to call mtDNA variants (Li et al., 2009; McKenna et al., 2010). SnpEff was used for variant annotation, and a custom script was utilized for variant filtration and prioritization (Cingolani et al., 2012). Prioritized variants were curated using the ACMG/AMP guidelines (Richards et al., 2015a,b) and variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were subclassified according to their clinical relevance into ‘uncertain significance: favor benign’ (VUS:FB) or ‘uncertain significance: favor pathogenic’ (VUS:FP) (McLaughlin et al., 2014a,b). Only VUS:FP were included as candidate variants for further study.

3. Results

3.1. Genome sequencing

Causative or candidate variants were identified in 15/22 (68.2%) families. Of the 15 genes implicated, all have a Mendelian disease association, seven associated with autosomal recessive inheritance (LSS, SLC17A5, BOLA3, DARS2, PMPCA, FIG4, NDUFV1); seven with autosomal dominant inheritance (COL4A1, TUBB4A, AGO2, SCN2A, SCN8A, GLS, SPTBN1) and one with X-linked dominant inheritance (STAG2). Six of the eight dominantly inherited variants were confirmed to have occurred de novo but, for two, only one parent was available for testing. For 11/15 families, the phenotype was within the spectrum previously associated with the gene; four of these were genes previously associated with leukodystrophy (COL4A1, NDUFV1, SLC17A5 and TUBB4A) and seven were genes associated with monogenic syndromes and developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (STAG2, LSS, SCN2A, SCN8A, AGO2, SPTBN1, GLS). For 4/15 families, the clinical presentation expanded the phenotypic spectrum associated with the gene, two of which were leukodystrophy-associated genes: BOLA3 (MIM# 614299) (Nikam et al., 2018) and DARS2 (MIM# 611105)(Scheper et al., 2007), and two were associated with other neurological disease at the time of variant identification: FIG4 (MIM# 611228)(Zhang et al., 2008) and PMPCA (MIM# 213200)(Choquet et al., 2016). A summary of the genotypes and phenotypes for the diagnosed individuals is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular diagnoses.

| Family ID | Sexa | MRI abnormalities | Additional clinical features | Gene | Genetic variant(s) | Zygosity | Variant classification (ACMG)^ | OMIM phenotype for gene | Previously published |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| RL_0006 | M (M) | Hypomyelination | Peripheral neuropathy, myopia | FIG4 | NM_014845.5(FIG4) c.2459+1G > A ClinVar: VCV000246120.2 | Hom | P | Charcot Marie Tooth, type 4J (CMT4J) MIM#611228 | Lenk et al. (2019) |

| RL_0007 | F | Subcortical hypomyelination and white matter atrophy | Syndromic intellectual disability | STAG2 | NM_001042750.2 (STAG2):c.3097C > T (p.Arg1033*) ClinVar: VCV000996008.2 | Het De novo | P | Mullegama-Klein-Martinez syndrome MIM#301022 | |

| RL_0008 | M | Diffuse dysmyelination with incomplete resolution | Acute regression with recovery | BOLA3 | NM_212552.3 (BOLA3):c.176G >A (p.Cys59Tyr) ClinVar: VCV001189446.1 | Het Maternal | LP | Multiple mitochondrial dysfunctions syndrome 2 (MMDS2) MIM#614299 | Stutterd et al. (2019) |

| NM_212552.3 (BOLA3):c.136C > T (p.Arg46*) ClinVar: VCV000224514.5 | Het Paternal | P | |||||||

| RL_0010 | M | Diffuse dysmyelination with cystic degeneration and late spinal cord involvement and normal MRS. | Slowly progressive spasticity | DARS2 | NM_018122.5 (DARS2):c.562C > T (p.Arg188*) ClinVar: VCV001256059.1 | Het Maternal | P | Leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation (LBSL) MIM#611105 | Stellingwerff et al. (2021) |

| NM_018122.5 (DARS2):c.1762C > G (Leu588Val) ClinVar: VCV000427120.2 | Het Paternal | LP | |||||||

| Rl_0012 | M | Multifocal dystrophic white matter with calcifications and porencephaly | Diplegia | COL4A1 | NM_001845.6 (COL4A1):c.2494G > A (p.Gly832Arg) ClinVar: VCV000208663.1 | Het De novo | P | Brain small vessel disease with or without ocular anomalies MIM#175780 | |

| RL_0013 | F | Diffuse dysmyelination | GDD | NDUFV1 | NM_007103.4 (NDUFV1):c.1156C > T (p.Arg386) ClinVar: VCV000419230.2 | Hom | LP | Mitochondrial complex 1 deficiency, nuclear type 4 MIM#618225 | |

| RL_0016 | F | Hypomyelination | GDD | TUBB4A | NM_006087.4 (TUBB4A):c.796T > A (p.Phe266Ile) ClinVar: VCV001256060.1 | Het De novo | LP | Leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 6 (HLD6) MIM#612438 | |

| RL_0017 | F | Multifocal, slowly progressive dysmyelination | Mild ID, hypotonia and lower limb hyporeflexia | AGO2 | NM_012154.5 (AGO2) c.1070C > T (p.Thr357Met) ClinVar: VCV000995792.2 | Het Unknown | LP | Lessel-Kreienkamp syndrome MIM#619149 | |

| RL_0019 | F | Dysmyelination | Severe ID, quadriplegia, epilepsy, skin lesions | GLS | NM_014905.5(GLS): c.866A > T (p. Lys289Ile) ClinVar: VCV001256052.1 | Het De novo | LP | Infantile cataract, skin abnormalities, glutamate excess, and impaired intellectual development MIM#618339 | |

| RL_0020 | M | Hypomyelination | Severe ID, quadriplegia | PMPCA | chr9:139316429G >A NM_015160.1 (PMPCA): c.1408+1G > A ClinVar: VCV001256053.1 | Het Maternal | P | Spinocerebellar ataxia, autosomal recessive 2 MIM#213200 | |

| chr9:139311137T >G NM_015160.1 (PMPCA): c.634-266T > G ClinVar: VCV001256054.1 | Het Paternal | LP | |||||||

| RL_0021 | M | Cerebral atrophy with abnormal signal of affected white matter | Severe ID, quadriplegia, dysmorphic features | SPTBN1 | NM_003128.2 (SPTBN1):c.469T > G (p.Phe157Val) ClinVar: VCV001256058.1 | Het Unknown | VUS:LP | Developmental delay, impaired speech, and behavioural abnormalities MIM#619475 |

|

| RL_0024 | F | Diffuse T2 hyperintensity with restricted diffusion suggestive of myelin oedema | Severe GDD, epilepsy | SCN8A | NM_001330260.2 (SCN8A):c.2549G > A (p.Arg850Gln) ClinVar: VCV000135651.4 | Het De novo | P | SCN8A-related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy MIM#614558 | |

| RL_0025 | F | Diffuse dysmyelination, cortical atrophy | Severe GDD, epilepsy | SCN2A | NM_001040142.2 (SCN2A): c.2588C > A (p.Ser863Tyr) ClinVar: VCV001256055.1 | Het De novo | P | Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 11 MIM#613721 | |

| RL_0026 | F (F) | Hypomyelination | Mod-severe ID, quadriplegia, | SLC17A5 | NM_012434.5 (SLC17A5):c.918T > G (p.Tyr306*) ClinVar: VCV000440272.3 | Het Maternal | P | Sialic acid storage disorder, infantile MIM#269920 |

|

| NM_012434.5 (SLC17A5):c.115C > T (p.Arg39Cys) ClinVar: VCV000005615.5 | Het Paternal | P | |||||||

| RL_0029 | F | Diffuse dysmyelination, cortical atrophy | Severe GDD, epilepsy, hypotrichosis | LSS | NM_002340.6(LSS): c.857A > G (p. Tyr286Cys) Clinvar: VCV001256056.1 | Het Maternal | LP | Hypotrichosis 14 MIM#818275 | |

| NM_002340.6(LSS): c.647G > A; p. (Trp216*) Clinvar: VCV001256057.1 | Het Paternal | P | |||||||

(Richards et al., 2015).

M = Male; F = Female; Hom = Homozygous; Het = Heterozygous; P=Pathogenic; LP = Likely pathogenic; VUS:LP = Variant of uncertain significance:Favours pathogenic(McLaughlin et al., 2014).

Sex of proband (affected sibling).

3.2. Additional investigations

For seven of the 15 families with causative or candidate variants, the diagnosis was identified from the initial trio or quad GS analysis. For the remaining eight families, additional clinical or genomic analysis was required to either confirm the pathogenicity of a candidate variant or identify the causative or candidate variant. This included research collaboration to identify a cohort of patients with a new gene-disease association (LSS) (Besnard et al., 2019), functional studies (BOLA3) (Stutterd et al., 2019a,b), RNA sequencing (PMPCA)(Takahashi et al., 2021), literature review of recently described novel gene-disease association (GLS)(Rumping et al., 2019), data reanalysis including recently discovered genes (AGO2, SPTBN1)(Cousin et al., 2021; Lessel et al., 2020), repeated clinical assessments for deeper phenotyping (FIG4) (Lenk et al., 2019a,b), and repeated MRI brain (DARS2)(Stellingwerff et al., 2021a,b). For seven families, trio GS reanalysis has been uninformative and they remain undiagnosed.

4. Discussion

Genetic disorders of the CNS white matter are a genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous group of diseases. In this study, which applied deep phenotyping, whole genome sequencing and functional studies to the diagnosis of unclassified CNS white matter disorders, a causative or candidate variant was identified in 15/22 (68.2%) families. All causative or candidate variants were absent from the population dataset gnomAD (Lek et al., 2016) or present at a low frequency if recessive, reflecting the typically rare nature and complete penetrance of these severe disorders. Previously published diagnostic yields from genomic studies of white matter disorders have varied, depending on the phenotypic homogeneity of the patient cohorts and the extent of pre-genomic investigations. A comparable study to this, by Vanderver et al., utilized trio ES to investigate a cohort of 71 patients with unclassified white matter disease and identified clinical diagnoses in 30 (42%) (Vanderver et al., 2016). Studies that have included patients diagnosed by non-genomic tests (‘standard of care’) and genomic tests (ES or GS) provide a more accurate reflection of the current clinical diagnostic yield for white matter disorders which has ranged from 75% (Mahdieh et al., 2021) to 76.5% (Vanderver et al., 2020) and 85% (Helman et al., 2020).

4.1. Utility of genome sequencing

All but one of the causative or candidate variants were within coding regions or canonical splice sites of genes with a reported disease association and therefore potentially detectable via ES, which is a more cost-effective genomic test. However, for one patient, the causative variant in SCN8A was in a coding region but was not identified by ES prior to this study due to the low coverage of the gene. Detection of this variant by GS highlights one of the advantages of GS over ES, being the uniformity of sequence coverage, which is especially helpful for G-C rich regions (Helman et al., 2020; Posey, 2019). GS is ideal for investigating novel intronic variants, though it is a significant challenge to recognise a pathogenic non-coding variant as compared to a coding variant. In this study, a deep intronic variant in PMPCA was identified as likely pathogenic, but recognized only by an RNAseq analysis looking for a second hit in trans with a pathogenic PMPCA variant. Therefore, the GS data, in this case, was more effectively interpreted following RNAseq. A potential advantage of GS over ES is the detection of copy number variants (CNV), though, in this study, SNP microarray was performed prior to recruitment, excluding causative variants above 10 kb in size. GS used in a study of 41 patients with unclassified white matter disease attributed five of the 14 diagnoses to the superiority of GS in detecting CNVs and variants in deep intronic and technically difficult regions (Helman et al., 2020). GS also includes analysis of mitochondrial DNA, though no causative variants were identified in mtDNA in this study.

4.2. Diagnosis of classical leukodystrophies

MRI pattern recognition is a powerful clinical tool to inform appropriate investigation of white matter disease, which, in a proportion of cases, can lead to a confirmed diagnosis via a specific biochemical test or focused genetic test (Schiffmann and van der Knaap, 2009). The purpose of expert MRI review in this study was to identify patients who would benefit from broader agnostic genomic testing due to the absence of a recognizable MRI pattern. Six of the 15 diagnosed cases implicated genes known to cause leukodystrophy, though two had atypical phenotypes (discussed below). The four cases with ‘classical leukodystrophies or genetic leukoencephalopathies’ were caused by pathogenic variants in SLC17A5, TUBB4A, NDUFV1 and COL4A1. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies, such as those associated with TUBB4A and SLC17A5, are radiologically recognizable as a group but genetically heterogeneous (Wolf, Ffrench-Constant and van der Knaap, 2021). There may be clinical and radiological clues to the molecular basis (Barkovich and Deon, 2016; Steenweg et al., 2010), though genomic testing provides the highest diagnostic yield (Vanderver et al., 2020). Likewise for white matter disorders associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, as in the case associated with NDUFV1, radiological features can distinguish this group, but genomic testing is indicated to confirm the molecular cause (Vanderver et al., 2020).

4.3. Expanded phenotypes for leukodystrophy-associated genes

Two patients had causative variants in leukodystrophy-associated genes, DARS2 (MIM# 611105)(Scheper et al., 2007) and BOLA3 (MIM# 614299)(Nikam et al., 2018), and presented with novel, atypical phenotypes, thereby expanding the phenotypic spectrum for these genes. Patient RL_0010 has bi-allelic DARS2 variants causative for leukoencephalopathy with brainstem and spinal cord involvement and elevated lactate (LBSL) but presented with cerebral white matter abnormalities without the long tract involvement that is typical for this condition. The more typical MRI features evolved over four years and were evident on repeat MRI. Subsequently, additional patients with atypical forms of LBSL have been identified and a more severe form of DARS2-associated disease has been described (Stellingwerff et al., 2021a,b). The second novel phenotype was associated with a mitochondrial leukoencephalopathy in an eight-year-old boy with compound heterozygous variants in BOLA3. RL_0008 presented with acute regression followed by near complete neurological and radiological recovery, in contrast to the expected progressive and life-limiting course associated with BOLA3-related disease. Mitochondrial functional analysis in cultured fibroblasts confirmed the pathogenicity of candidate variants in BOLA3 (Stutterd et al., 2019a,b). These cases demonstrate the need for collaborative studies of atypical phenotypes and functional studies to confirm pathogenicity of candidate variants.

4.4. White matter abnormalities in monogenic syndromes and developmental and epileptic encephalopathies

For six individuals, the cause for their white matter disease was not a primary leukodystrophy or leukoencephalopathy. These causes included genes associated with developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (SCN2A, SCN8A), an X-linked dominant cohesinopathy (STAG2), a recessive cholesterol biosynthesis disorder (LSS) and two recently described monogenic syndromes (AGO2, SPTBN1). Static white matter abnormalities are a recognized feature of several monogenic and chromosomal syndromes (Shukla et al., 2020; Vanderver et al., 2014; Vigdorovich et al., 2020). Clinically, they may be distinguishable by a static disease course and the presence of abnormal growth, dysmorphism or congenital malformation. MRI abnormalities characteristic of such developmental disorders are static, multifocal, asymmetric MRI T2 hyperintensities and non-specific abnormalities such as enlarged perivascular spaces (Vanderver et al., 2014; Vigdorovich et al., 2020). Trio analysis provides an advantage in the diagnosis as the majority have de novo dominant cause (Tan et al., 2019). A genetic diagnosis is key to informing the prognosis and management of such conditions which may differ significantly from a progressive leukodystrophy and may avoid ongoing investigation such as repeated MRI studies. Accurate clinical phenotyping can also inform the prioritization of variants for curation which increases the diagnostic yield from genomic testing (Stark et al., 2017).

4.5. Genetic causes not previously associated with white matter disease

For three families, the candidate gene had not been previously associated with white matter disease:

4.5.1. A homozygous splice variant in FIG4

A sibling pair with peripheral neuropathy and central hypomyelination were homozygous for a canonical splice variant in FIG4. Pathogenicity of the splice site variant was demonstrated with RNA analysis and subsequently, the association of bi-allelic FIG4 variants with central hypomyelination was identified in two other families and this cohort of three families was published (Lenk et al., 2019a,b). Deep phenotyping of our siblings identified skeletal abnormalities, such as thin shafts of the tubular bones with over-tubulation and thin metacarpals, overlapping the Yunis Varón syndrome which is the consequence of two FIG4 null alleles. This observation suggested a continuum of disease between Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4J (MIM#611228) and Yunis Varón syndrome (MIM#216340), and additional phenotypes on this continuum have since been reported to include Parkinsonism (Zimmermann et al., 2020). The identification of FIG4 as the cause for our patients’ phenotype was facilitated by data sharing and research collaboration. Such developments in gene-disease associations necessitate the use of dynamic gene lists, such as those provided by PanelApp, to support phenotype-driven analyses (Martin et al., 2019).

4.5.2. De novo missense variant in GLS

A de novo missense variant in GLS was identified in individual RL_0019, who had died at seven years of age with severe, progressive spastic quadriplegia, vasculitic skin rash since infancy and a heterogeneous white matter signal abnormality with diffuse atrophy on MRI. The variant NM_014905(GLS):c.866A > T (p.Lys289Ile) alters a highly conserved residue in GLS, the gene encoding glutaminase which catalyzes the conversion of glutamine into glutamate. Bi-allelic variants in GLS are associated with developmental delay, developmental and epileptic encephalopathy and elevated glutamine. However, one individual with CNS disease and vasculitic rash has been reported with a de novo heterozygous missense variant in GLS (p.Ser482Cys) (Rumping et al., 2019). This individual had normal plasma and CSF levels of glutamine and glutamate, but abnormal levels subsequently detected in urine and on magnetic resonance spectroscopic (MRS) imaging in the cortex and white matter. Functional analysis of this variant in a cell model demonstrated gain-of-function of the protein (Rumping et al., 2019). Our patient similarly had normal plasma and CSF glutamine and glutamate levels. Unfortunately, a urine sample and brain MRS imaging are not available for assessment. Given the location of this variant affecting a functional residue with multiple lines of computational evidence supporting a deleterious effect, it’s absence from controls, and de novo status, it is considered to be likely pathogenic with a suspected gain-of-function mechanism.

4.5.3. Compound heterozygous variants in PMPCA

Compound heterozygous variants in PMPCA were identified in RL_0020 who died at 17 years with progressive quadriplegia and diffuse CNS hypomyelination, cerebellar atrophy, thin corpus callosum and progressive global atrophy. PMPCA encodes one subunit of a heterodimeric protein, alpha mitochondrial processing peptidase (α-MPP), responsible for maturation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins (Geli and Glick, 1990). Bi-allelic variants cause a spinocerebellar ataxia associated with degeneration of the cerebellum with variable involvement of the brainstem and spinal cord (MIM#213200). The phenotypic spectrum has recently been expanded in association with novel mutations in two families. Two related individuals had profound global developmental delay and multisystem disease with functional studies demonstrating defective α-MPP protein (Joshi et al., 2016). A third individual had infantile-onset, severe and progressive developmental delay, cerebellar ataxia, and extrapyramidal symptoms with cerebellar atrophy and excessive brain iron accumulation in the bilateral globus pallidi and substantia nigra (Takahashi et al., 2021). For RL_0020, the initial analysis of genomic variants identified a maternally inherited heterozygous +1 splice donor variant in exon 12 of PMPCA. However, this variant was not prioritized as no paternally inherited variant was identified. This case was included in a pilot study whereby RNA sequencing was performed on RNA extracted from patient fibroblasts and analyzed to identify aberrant splicing events. The RNAseq data confirmed the exon 12 splice donor variant results in skipping of PMPCA exon 12 resulting in a loss of reading frame. Careful inspection of the RNAseq data in PMPCA resulted in the identification of a cryptic exon in intron 6 with an in-frame termination codon. The cryptic exon results from a paternally inherited variant NM_015160.1:c.634-266T>G that generates a canonical splice donor site used by the cryptic exon. Overall PMPCA expression in this patient was significantly reduced compared to a panel of similarly sequenced controls (log2 fold change: 2.15, Padj <7.8×10−8) (Wai et al., 2020).

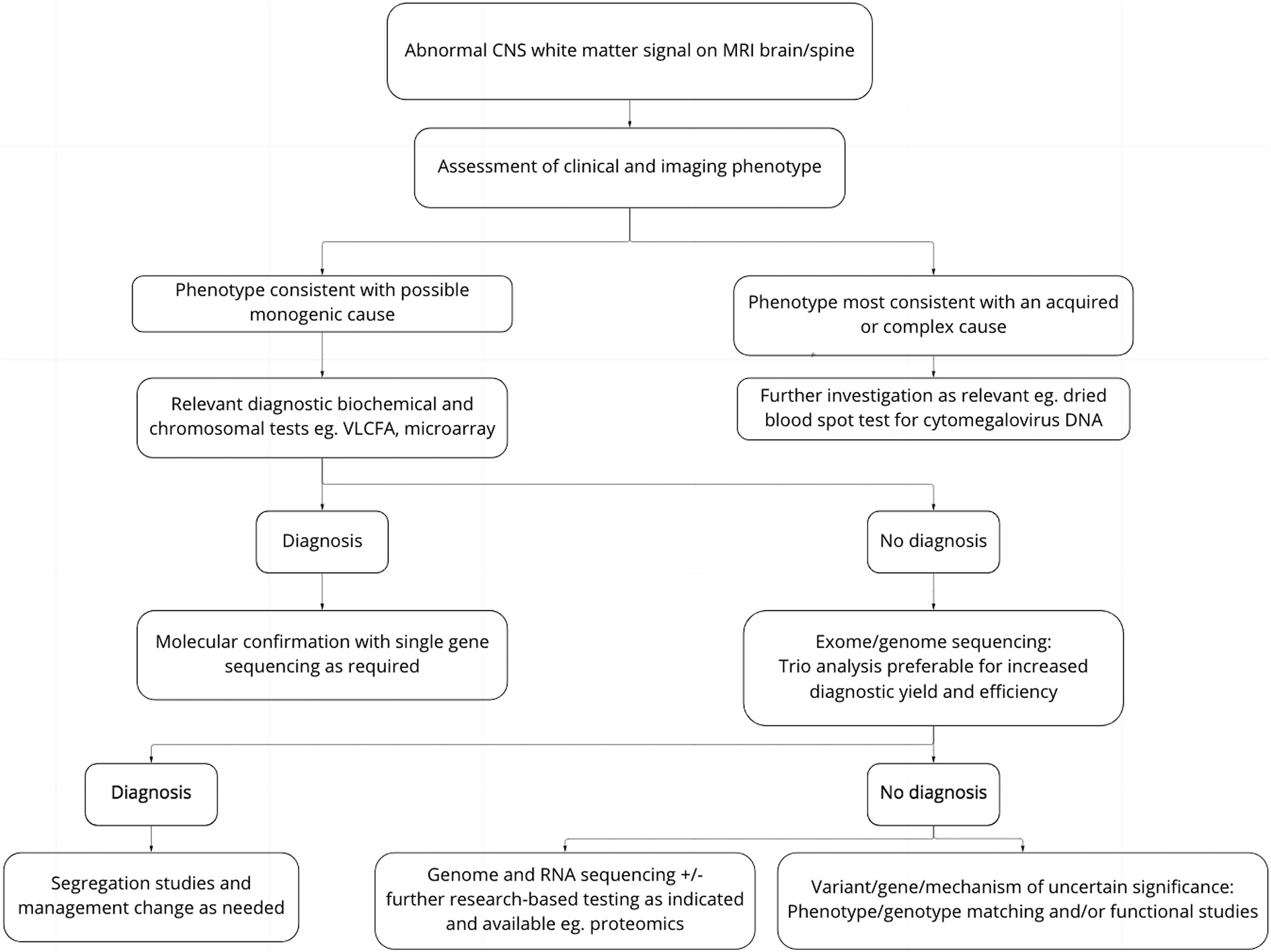

4.6. Further investigation of undiagnosed patients

Seven families remain without a diagnosis or candidate variant following family-based GS. Emerging technologies may assist in identifying variants not tractable by GS. These include RNA sequencing to detect variants affecting splicing that may be synonymous and therefore filtered out by the GS bioinformatic pipeline (Cummings et al., 2017), long-read sequencing to achieve more accurate sequencing data and improve the detection of structural variants (Amarasinghe et al., 2020), and proteomic analysis to identify cellular protein deficiencies which may be particularly useful in diagnosing mitochondrial disorders(Helman et al., 2021). Ongoing review of unclassified phenotypes and novel genotypes, in collaboration with other research groups and the use of phenotype/genotype data sharing platforms such as Matchmaker Exchange(Azzariti and Hamosh, 2020), may contribute to gene discovery, and investigation of affected sibships provide a unique opportunity in this regard (Posey et al., 2019). A schematic of this diagnostic pathway is present in Fig. 1. Regular reanalysis of GS data is important due to the discovery of new gene-disease associations and improved bioinformatic pipelines (Tan et al., 2020). For white matter diseases with suspected genetic aetiology, ongoing investigation for a precise diagnosis is indicated as it can provide significant benefits to an individual and their family (Adang et al., 2017; Splinter et al., 2018; Stavropoulos et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2018). As noted in the clinical summaries in Supplementary file 1, the differential diagnosis in some cases includes an acquired cause. These patients were included in this study as testing for a potential genetic cause was clinically indicated. In such cases however, continuation of the genetic studies may not be indicated and carries the risk of a misdiagnosis if irrelevant variants are wrongly assigned to the cause.

Fig. 1.

Approach to diagnosis of patients with suspected genetic disorder of white matter.

5. Conclusions

Genetic disorders of CNS white matter are phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous, requiring multidisciplinary collaboration for diagnosis. Genomic testing is indicated as a first-tier diagnostic test following phenotyping, including MRI pattern recognition, to assist with variant prioritization and improve diagnostic yield. Further investigation of undiagnosed cases may include the use of advanced bioinformatics, data sharing, and functional studies. The role of emerging technologies such as RNAseq, long-read sequencing and proteomics is yet to be established. In addition to the clinical benefits of a precise diagnosis, identifying the molecular basis of white matter diseases is key to understanding their pathogenesis and identifying targets for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Details of funding

CAS was supported by NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (ID: APP1133266) and the Royal Children’s Hospital/Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Flora Suttie Neurogenetics Fellowship made possible by the Thyne-Reid Foundation and the Macquarie Foundation. RJL is supported by a Melbourne Children’s Clinician Scientist Fellowship. This work was supported by the Massimo’s Mission Leukodystrophy Flagship funded by the Australian Government Medical Research Futures Fund. This work was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program and Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council Independent Research Institute Infrastructure Support Scheme (NHMRC IRIISS) and NHMRC Project Grant 1068278. AV is supported by the Kamens Chair in Translational Neurotherapeutics. MSvdK receives research support from NWO, ZonMw, European Leukodystrophy Foundation, Nederlandse Hersenstichting, Vanishing White Matter Foundation, Chloe Saxby and VWM Disease Incorporated, and VWM Families Foundation Inc. IES is supported by grants and fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. NIW receives research support from Metakids and ZonMW The authors confirm independence from the sponsors; the content of the article has not been influenced by the sponsors.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

C.A. Stutterd: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. A. Vanderver: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data. P.J. Lockhart: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data. G. Helman: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. K. Pope: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. E. Uebergang: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. C. Love: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M.B. Delatycki: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Conception and design of the study, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. D. Thorburn: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M.T. Mackay: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. H. Peters: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. A.J. Kornberg: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. C. Patel: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. V. Rodriguez-Casero: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M. Waak: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. J. Silberstein: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. A. Sinclair: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M. Nolan: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M. Field: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M.R. Davis: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. M. Fahey: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Acquisition and analysis of data. I. E. Scheffer: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. J.L. Freeman: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Acquisition and analysis of data. N.I. Wolf: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. R.J. Taft: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Conception and design of the study. M.S. van der Knaap: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. C. Simons: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. R.J. Leventer: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conception and design of the study, Acquisition and analysis of data, Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2022.104551.

References

- Adang LA, Sherbini O, Ball L, Bloom M, Darbari A, Amartino H, Global Leukodystrophy Initiative C, 2017. Revised consensus statement on the preventive and symptomatic care of patients with leukodystrophies. Mol. Genet. Metabol. 122 (1–2), 18–32. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe SL, Su S, Dong X, Zappia L, Ritchie ME, Gouil Q, 2020. Opportunities and challenges in long-read sequencing data analysis. Genome Biol. 21 (1), 30. 10.1186/s13059-020-1935-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzariti DR, Hamosh A, 2020. Genomic data sharing for novel mendelian disease gene discovery: the matchmaker Exchange. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 21, 305–326. 10.1146/annurev-genom-083118-014915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich AJ, Deon S, 2016. Hypomyelinating disorders: an MRI approach. Neurobiol. Dis. 87, 50–58. 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard T, Sloboda N, Goldenberg A, Kury S, Cogne B, Breheret F, Isidor B, 2019. Biallelic pathogenic variants in the lanosterol synthase gene LSS involved in the cholesterol biosynthesis cause alopecia with intellectual disability, a rare recessive neuroectodermal syndrome. Genet. Med. 21 (9), 2025–2035. 10.1038/s41436-019-0445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet K, Zurita-Rendon O, La Piana R, Yang S, Dicaire MJ, Care4Rare C, Tetreault M, 2016. Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia caused by a homozygous mutation in PMPCA. Brain 139 (Pt 3), e19. 10.1093/brain/awv362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Ruden DM, 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6 (2), 80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin MA, Creighton BA, Breau KA, Spillmann RC, Torti E, Dontu S, Lorenzo DN, 2021. Pathogenic SPTBN1 variants cause an autosomal dominant neurodevelopmental syndrome. Nat. Genet. 53 (7), 1006–1021. 10.1038/s41588-021-00886-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings BB, Marshall JL, Tukiainen T, Lek M, Donkervoort S, Foley AR, MacArthur DG, 2017. Improving genetic diagnosis in Mendelian disease with transcriptome sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 9 (386) 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eratne D, Schneider A, Lynch E, Martyn M, Velakoulis D, Fahey M, Berkovic SF, 2021. The clinical utility of exome sequencing and extended bioinformatic analyses in adolescents and adults with a broad range of neurological phenotypes: an Australian perspective. J. Neurol. Sci. 420, 117260 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli V, Glick B, 1990. Mitochondrial protein import. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 22 (6), 725–751. 10.1007/BF00786928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helman G, Lajoie BR, Crawford J, Takanohashi A, Walkiewicz M, Dolzhenko E, Vanderver A, 2020. Genome sequencing in persistently unsolved white matter disorders. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7 (1), 144–152. 10.1002/acn3.50957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helman G, Compton AG, Hock DH, Walkiewicz M, Brett GR, Pais L, Simons C, 2021. Multiomic analysis elucidates Complex I deficiency caused by a deep intronic variant in NDUFB10. Hum. Mutat. 42 (1), 19–24. 10.1002/humu.24135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi M, Anselm I, Shi J, Bale TA, Towne M, Schmitz-Abe K, Agrawal PB, 2016. Mutations in the substrate binding glycine-rich loop of the mitochondrial processing peptidase-alpha protein (PMPCA) cause a severe mitochondrial disease. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2 (3), a000786 10.1101/mcs.a000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, Exome Aggregation C, 2016. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536 (7616), 285–291. 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk GM, Berry IR, Stutterd CA, Blyth M, Green L, Vadlamani G, Meisler MH, 2019a. Cerebral hypomyelination associated with biallelic variants of FIG4. Hum. Mutat. 40 (5), 619–630. 10.1002/humu.23720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk GM, Berry IR, Stutterd CA, Blyth M, Green L, Vadlamani G, Warren D, Craven I, Fanjul-Fernandez M, Rodriguez-Casero V, Lockhart PJ, Vanderver A, Simons C, Gibb S, Sadedin S, Broad Center for Mendelian G, White SM, Christodoulou J, Skibina O, Ruddle J, Tan TY, Leventer RJ, Livingston JH, Meisler MH, 2019b. Cerebral hypomyelination associated with biallelic variants of FIG4. Hum. Mutat. 40 (5), 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessel D, Zeitler DM, Reijnders MRF, Kazantsev A, Hassani Nia F, Bartholomaus A, Kreienkamp HJ, 2020. Germline AGO2 mutations impair RNA interference and human neurological development. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 5797. 10.1038/s41467-020-19572-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Genome Project Data Processing S, 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25 (16), 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdieh N, Soveizi M, Tavasoli AR, Rabbani A, Ashrafi MR, Kohlschutter A, Rabbani B, 2021. Genetic testing of leukodystrophies unraveling extensive heterogeneity in a large cohort and report of five common diseases and 38 novel variants. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 3231. 10.1038/s41598-021-82778-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AR, Williams E, Foulger RE, Leigh S, Daugherty LC, Niblock O, McDonagh EM, 2019. PanelApp crowdsources expert knowledge to establish consensus diagnostic gene panels. Nat. Genet. 51 (11), 1560–1565. 10.1038/s41588-019-0528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, DePristo MA, 2010. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20 (9), 1297–1303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin HM, Ceyhan-Birsoy O, Christensen KD, Kohane IS, Krier J, Lane WJ, MedSeq P, 2014a. A systematic approach to the reporting of medically relevant findings from whole genome sequencing. BMC Med. Genet. 15, 134. 10.1186/s12881-014-0134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin HM, Ceyhan-Birsoy O, Christensen KD, Kohane IS, Krier J, Lane WJ, Lautenbach D, Lebo MS, Machini K, MacRae CA, Azzariti DR, Murray MF, Seidman CE, Vassy JL, Green RC, Rehm HL, MedSeq P, 2014b. A systematic approach to the reporting of medically relevant findings from whole genome sequencing. BMC Med. Genet. 15, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikam RM, Gripp KW, Choudhary AK, Kandula V, 2018. Imaging phenotype of multiple mitochondrial dysfunction syndrome 2, a rare BOLA3-associated leukodystrophy. Am. J. Med. Genet. 176 (12), 2787–2790. 10.1002/ajmg.a.40490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh S, Bernard G, Leventer RJ, van der Knaap MS, van Hove J, Pizzino A, Consortium G, 2015. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of patients with leukodystrophies and genetic leukoencephelopathies. Mol. Genet. Metabol. 114 (4), 501–515. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.12.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey JE, 2019. Genome sequencing and implications for rare disorders. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 14 (1), 153. 10.1186/s13023-019-1127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey JE, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Chong JX, Harel T, Jhangiani SN, Coban Akdemir ZH, Centers for Mendelian G, 2019. Insights into genetics, human biology and disease gleaned from family based genomic studies. Genet. Med. 21 (4), 798–812. 10.1038/s41436-018-0408-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Committee ALQA, 2015a. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17 (5), 405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, Committee ALQA, 2015b. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17 (5), 405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumping L, Tessadori F, Pouwels PJW, Vringer E, Wijnen JP, Bhogal AA, van Hasselt PM, 2019. GLS hyperactivity causes glutamate excess, infantile cataract and profound developmental delay. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28 (1), 96–104. 10.1093/hmg/ddy330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper GC, van der Klok T, van Andel RJ, van Berkel CG, Sissler M, Smet J, van der Knaap MS, 2007. Mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency causes leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Nat. Genet. 39 (4), 534–539. 10.1038/ng2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann R, van der Knaap MS, 2009. Invited article: an MRI-based approach to the diagnosis of white matter disorders. Neurology 72 (8), 750–759. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343049.00540.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Kaur P, Narayanan DL, do Rosario MC, Kadavigere R, Girisha KM, 2020. Genetic disorders with central nervous system white matter abnormalities: an update. Clin. Genet. 10.1111/cge.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splinter K, Adams DR, Bacino CA, Bellen HJ, Bernstein JA, Cheatle-Jarvela AM, Undiagnosed Diseases N, 2018. Effect of genetic diagnosis on patients with previously undiagnosed disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 379 (22), 2131–2139. 10.1056/NEJMoa1714458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark Z, Dashnow H, Lunke S, Tan TY, Yeung A, Sadedin S, James PA, 2017. A clinically driven variant prioritization framework outperforms purely computational approaches for the diagnostic analysis of singleton WES data. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25 (11), 1268–1272. 10.1038/ejhg.2017.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavropoulos DJ, Merico D, Jobling R, Bowdin S, Monfared N, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Marshall CR, 2016. Whole genome sequencing expands diagnostic utility and improves clinical management in pediatric medicine. NPJ Genom. Med. 1 10.1038/npjgenmed.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenweg ME, Vanderver A, Blaser S, Bizzi A, de Koning TJ, Mancini GM, van der Knaap MS, 2010. Magnetic resonance imaging pattern recognition in hypomyelinating disorders. Brain 133 (10), 2971–2982. 10.1093/brain/awq257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellingwerff MD, Figuccia S, Bellacchio E, Alvarez K, Castiglioni C, Topaloglu P, Van der Knaap MS, 2021a. LBSL: case series and DARS2 variant analysis in early severe forms with unexpected presentations. Neurol Genet. 7 (2), e559. 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellingwerff MD, Figuccia S, Bellacchio E, Alvarez K, Castiglioni C, Topaloglu P, Stutterd CA, Erasmus CE, Sanchez-Valle A, Lebon S, Hughes S, Schmitt-Mechelke T, Vasco G, Chow G, Rahikkala E, Dallabona C, Okuma C, Aiello C, Goffrini P, Abbink TEM, Bertini ES, Van der Knaap MS, 2021b. LBSL: case series and DARS2 variant analysis in early severe forms with unexpected presentations. Neurol Genet. 7 (2), e559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutterd CA, Lake NJ, Peters H, Lockhart PJ, Taft RJ, van der Knaap MS, Leventer RJ, 2019a. Severe leukoencephalopathy with clinical recovery caused by recessive BOLA3 mutations. JIMD Rep. 43, 63–70. 10.1007/8904_2018_100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutterd CA, Lake NJ, Peters H, Lockhart PJ, Taft RJ, van der Knaap MS, Vanderver A, Thorburn DR, Simons C, Leventer RJ, 2019b. Severe leukoencephalopathy with clinical recovery caused by recessive BOLA3 mutations. JIMD Rep. 43, 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Kubota M, Kosaki R, Kosaki K, Ishiguro A, 2021. A severe form of autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia associated with novel PMPCA variants. Brain Dev. 43 (3), 464–469. 10.1016/j.braindev.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TY, Lunke S, Chong B, Phelan D, Fanjul-Fernandez M, Marum JE, White SM, 2019. A head-to-head evaluation of the diagnostic efficacy and costs of trio versus singleton exome sequencing analysis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10.1038/s41431-019-0471-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan NB, Stapleton R, Stark Z, Delatycki MB, Yeung A, Hunter MF, Tan TY, 2020. Evaluating systematic reanalysis of clinical genomic data in rare disease from single center experience and literature review. Mol. Genet. Genomic. Med. 8 (11), e1508 10.1002/mgg3.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Knaap MS, Bugiani M, 2017. Leukodystrophies: a proposed classification system based on pathological changes and pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 134 (3), 351–382. 10.1007/s00401-017-1739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Knaap MS, Schiffmann R, Mochel F, Wolf NI, 2019. Diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of leukodystrophies. Lancet Neurol. 18 (10), 962–972. 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderver A, Tonduti D, Kahn I, Schmidt J, Medne L, Vento J, van der Knaap MS, 2014. Characteristic brain magnetic resonance imaging pattern in patients with macrocephaly and PTEN mutations. Am. J. Med. Genet. 164A (3), 627–633. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderver A, Simons C, Helman G, Crawford J, Wolf NI, Bernard G, Taft RJ, 2016. Whole exome sequencing in patients with white matter abnormalities. Ann. Neurol. 79 (6), 1031–1037. 10.1002/ana.24650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderver A, Bernard G, Helman G, Sherbini O, Boeck R, Cohn J, Leuko SEQW, 2020. Randomized clinical trial of first-line genome sequencing in pediatric white matter disorders. Ann. Neurol. 10.1002/ana.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigdorovich N, Ben-Sira L, Blumkin L, Precel R, Nezer I, Yosovich K, Zerem A, 2020. Brain white matter abnormalities associated with copy number variants. Am. J. Med. Genet. 182 (1), 93–103. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wai HA, Lord J, Lyon M, Gunning A, Kelly H, Cibin P, disease working, g., 2020. Blood RNA analysis can increase clinical diagnostic rate and resolve variants of uncertain significance. Genet. Med. 22 (6), 1005–1014. 10.1038/s41436-020-0766-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf NI, Ffrench-Constant C, van der Knaap MS, 2021. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies - unravelling myelin biology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17 (2), 88–103. 10.1038/s41582-020-00432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CF, FitzPatrick DR, Firth HV, 2018. Paediatric genomics: diagnosing rare disease in children. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19 (5), 253–268. 10.1038/nrg.2017.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chow CY, Sahenk Z, Shy ME, Meisler MH, Li J, 2008. Mutation of FIG4 causes a rapidly progressive, asymmetric neuronal degeneration. Brain 131 (Pt 8), 1990–2001. 10.1093/brain/awn114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M, Schuster S, Boesch S, Korenke GC, Mohr J, Reichbauer J, Schols L, 2020. FIG4 mutations leading to parkinsonism and a phenotypical continuum between CMT4J and Yunis Varon syndrome. Park. Relat. Disord. 74, 6–11. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.