Abstract

Background:

The study of psychological wellbeing and related resilient outcomes is of increasing focus in cardiovascular research. Despite the critical importance of psychological wellbeing and related resilient outcomes in promoting optimal cardiac health, there have been very few psychological interventions directed towards pediatric patients with heart disease. This paper describes the development and theoretical framework of the WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program, a group-based psychoeducation and coping skills training intervention designed to improve psychological wellbeing and resilience in adolescents with pediatric heart disease.

Methods:

Program development was informed by patient and family needs and input gathered via large, international survey methods as well as qualitative investigation, a theoretical framework, and related resilience intervention research.

Results:

An overview of the WE BEAT intervention components and structure of the program is provided.

Conclusions:

The WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program was developed as one of the first resiliency-focused interventions in pediatric heart disease with an overall objective to foster positive psychological wellbeing and resilient outcomes through a health promotion and prevention lens in an accessible format while providing access to safe, peer-to-peer community building. Feasibility pilot results are forthcoming. Future directions include mobile-app based delivery and larger scale efficacy and implementation trials.

Keywords: resilience, wellbeing, mental health, intervention, CHD

Introduction

Psychological wellbeing has been of increasing focus in the prevention of cardiovascular disease over recent decades.1–3 Psychological wellbeing is not only the absence of negative psychological factors, such as anxiety or depression, but also the presence of positive psychological indicators, such as optimism and sense of purpose, which together increase healthy behaviors and improve cardiovascular function.1,2,4 Resiliency is a related facet of psychological wellbeing and is defined as the process by which an individual harnesses internal, external and learned resources to maintain wellbeing amidst a stressor,5 such as chronic or critical illness.

Resiliency is a construct of growing importance in cardiovascular clinical care and research. In a large sample of nearly 1,000 adults with heart disease, multisystem resiliency, defined in the study as encompassing emotion regulation skills, social connectedness, and positive health behaviors, was associated with longer telomere length,6 a biomarker of cellular aging7 that has been shown to be associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes.8–10 Resiliency has been shown to be correlated with important outcomes in pediatric chronic illness populations as well, including improved health-related quality of life and decreased psychological distress in pediatric cancer patients,11 better glycemic control in adolescents with diabetes,12 decreased depressive symptoms in youth with congenital heart disease (CHD)13 and better transition readiness in a pediatric chronic illness group.14 In a recent study of over 300 individuals with CHD, higher resilience was correlated with fewer hospital admissions, lack of mental health diagnosis, increased exercise, and participation in peer support groups or disease-specific camps.15 Causal pathways between resilience and health outcomes in pediatric heart disease are not well understood and bi-directional relationships are very possible, however, interventions targeting resilience across other pediatric chronic medical conditions11,16,17 and adult CHD (ACHD) groups have shown promise.18,19 These interventions have also underscored potential areas for adaption and improvement to meet the specific needs of pediatric heart disease populations. Taken together, the literature suggests that resiliency is associated with important psychological and physical-health related outcomes and is a modifiable intervention target.

Despite the critical importance of psychological wellbeing and related resilient outcomes in promoting optimal cardiac health, there have been very few psychological interventions directed towards pediatric patients with heart disease.20 In a recent systematic review, only four adolescent-directed psychological interventions in young people with CHD were identified, and the efficacy of these interventions was inconsistent.21 As such, the development, implementation and testing of psychological interventions in pediatric heart disease has been identified as high priority by various organizations and stakeholders,20,22,23 including patient and parent advocacy groups.24 This paper describes the development and theoretical framework of the WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program, a group-based psychoeducation and coping skills training intervention designed to improve psychological wellbeing and resilient outcomes in individuals with pediatric heart disease. Program development was informed by patient and family needs and input, a theoretical framework, and intervention research. An overview of the WE BEAT intervention components and structure of the program is provided and future directions are detailed.

Methods

A series of patient-focused research studies led by our team over recent years, in addition to a theoretical guiding framework and relevant intervention research informed WE BEAT intervention design.

Patient-Informed Intervention Components

Previously published patient-focused research by our team and others helped to inform WE BEAT intervention design. Specifically, a large, international psychosocial needs assessment, a single-center needs assessment, and a qualitative-mixed methods study informed overall need and patient-driven components of the intervention. In a previously published international survey of 1,200 patients with CHD and their caregivers across 25 countries (patient median age = 10 years, IQR=4–28 years; 48% single-ventricle CHD), we sought to characterize the psychosocial support needs of children, adolescents and young adults with heart disease. Among respondents, 1 in 3 stated additional psychoeducation specific to promoting their own mental health/coping would be helpful.25 Although this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, findings are similar to that reported in ACHD, where 1/3 of patients stated interest in stress management and/or coping with heart disease interventions.26 In a more recent survey-based single-center needs assessment of 19 adolescents (13–18 years old) with single-ventricle CHD, 84% believed access to cardiology-specific counseling services would be helpful. Approximately a quarter of our large international sample desired increased access to peer support/connection opportunities,25 while 63% of adolescents who provided input through our single center needs assessment stated that having peer support for the issues they face with CHD would be helpful, consistent with others’ findings regarding the importance of peer support.26–28

Lastly, our team recently completed federally funded semi-structured interview study conducted with young people of diverse backgrounds ages 12–24 years with advanced heart disease and their caregivers. This larger study included aims beyond WE BEAT intervention development, including communication and medical decision-making needs in advanced heart disease, however, also included questions specific to resilience and psychosocial needs which subsequently helped to inform WE BEAT intervention development. Patients most commonly defined resiliency as one’s ability to “bounce back” and/or to “keep fighting.” When asked what helps young people with heart disease build resilience, a majority spoke to the importance of maintaining optimism and positivity, as well as social support, which is consistent with qualitative findings in ACHD.29 Similarly, when asked to give advice to peers with similar heart conditions, key themes centered around self-identity beyond one’s heart disease (e.g., “don’t let heart disease define you”), maintaining optimism and positivity (e.g., “it gets easier”; Glenn et al., manuscript under review).

Through the large-scale international survey research, single-center needs assessment, and qualitative interview study, we ascertained that a meaningful subset of adolescent and young adult patients with heart disease 1) desire psychoeducation specific to coping with heart disease and 2) find value in peer-based social support. As such, the WE BEAT intervention was designed with emphasis on teaching coping skills through group-based peer-supported delivery.

Theory-Informed Intervention Components

Although there are many definitions of resilience,30,31 the one used by our team focuses on fostering and developing several promotive and protective factors and processes as opposed to a specific outcome.5,32 Process-focused definitions emphasize that resilience is derived from multiple resources, both internal and external, and that one’s resiliency is dynamic and changing.33 It is not simply a trait, although innate characteristics and neurobiological factors can influence one’s capacity to harness their resources and adapt.33

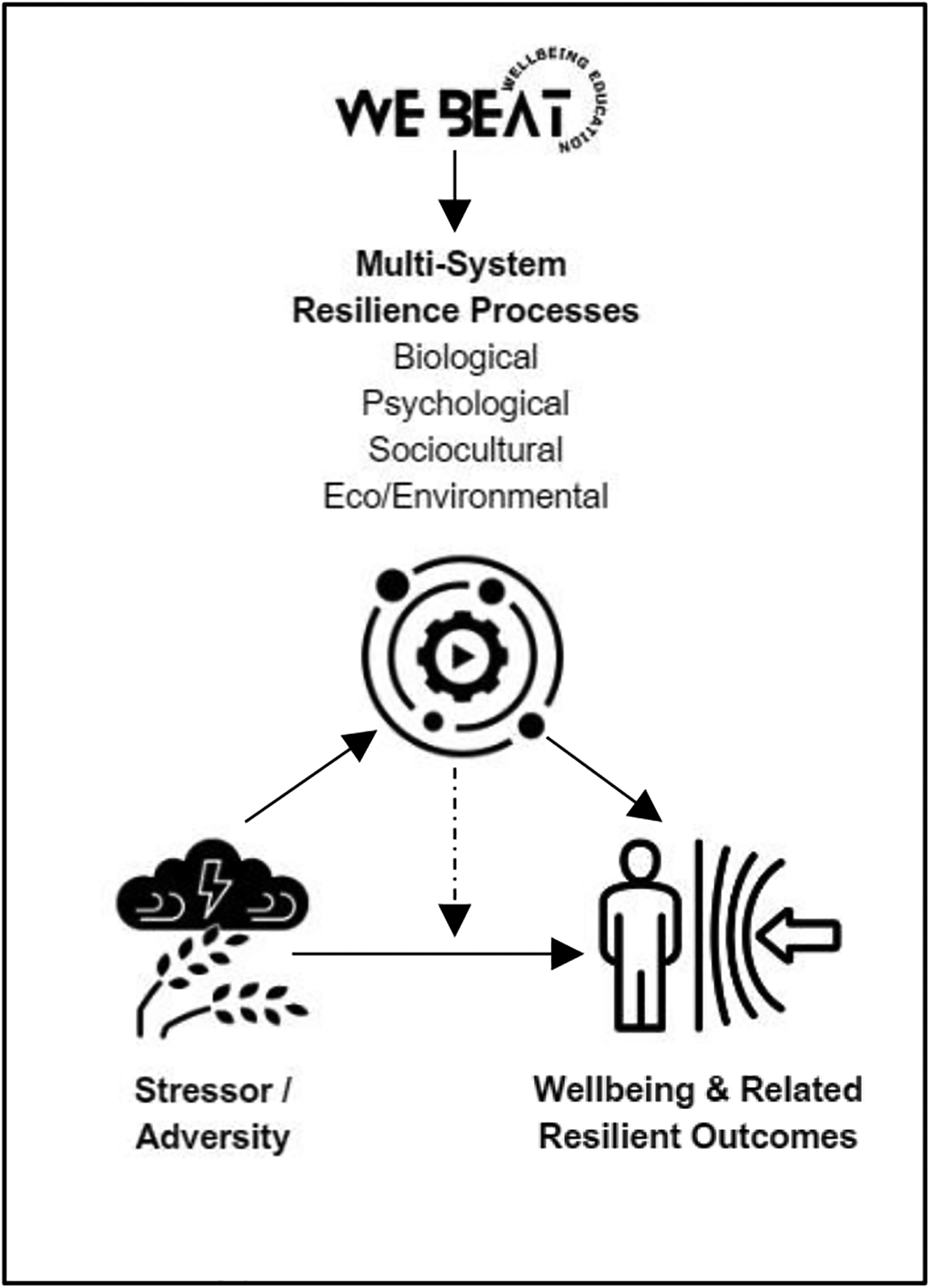

As such, resiliency is best understood through a multifaceted lens with biological, psychological, social, and ecological influences interacting across these systems.34 The relationship between a stressor and the experience of resilient outcomes, such as reduced mental health symptoms, can be impacted by one’s abilities to harness these resiliency resources across these interacting systems. Interventions aimed at increasing access to resiliency resources is one way of further promoting resilient outcomes in the face of adversity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program Theoretical Framework.

The theoretical framework for the WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program, including moderation and mediation pathways.

Many have identified various internal and external promotive and protective factors and processes important to resilience and positive development. Our WE BEAT intervention theoretical framework (Figure 1) is largely informed by the work of Masten31,35–37 and Ungar et al.34,38 Masten’s well-known “shortlist” of promotive and protective factors and processes36,39 includes: attachment, self-regulation, meaning making, agency and mastery, intelligence and problem solving, and self- and collective-efficacy. Ungar and colleagues underscore relationships, control and efficacy, social justice, access to basic resources, identity and sense of cohesion as important resilience resources.34 Informed by these various potential sources of resiliency, multi-systemic resilience emphasizes a “network” of available promotive and protective factors and processes when coping under stress.38

Core promotive and protective factors fostered in WE BEAT include self-regulation, identity, sense of cohesion, self-efficacy, and meaning making, as well as collective efficacy and relationships, reflecting a mixture of both internal and external psychological and social resources. The group format is purposeful to further target social-level resilience resources. Lastly, accessibility and scalability has been considered critical to design from the outset, including intervention delivery via telemedicine and free participation, recognizing that socioeconomic, environmental, and cultural factors influence access to internal and external resilience resources (i.e., eco-environmental processes). As Ungar and Theron wrote, “Resilience it not solely a quality within individuals; it grows from access to and use of the resources needed to support mental health and wellbeing.”34

Research-Informed Intervention Components

In addition to patient and parent/caregiver-stakeholder engagement through formal qualitative research and patient/family advisory council input, program design was informed by extensive review of the resilience intervention research, with particular focus on interventions within pediatric chronic illness and CHD. The Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) intervention, originally piloted within the context of pediatric and young adult cancer and diabetes,16 focuses on teaching four skills: stress management, goal setting, cognitive restructuring, and benefit finding. This brief intervention is delivered via four 30–60 minute individual sessions.16 Using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design in pediatric and young adult cancer, PRISM participation was shown to be associated with improved resilience and disease-specific quality of life, increased benefit finding and hope, and reduced psychological distress.11,40 In the initial pilot sample of inpatients and outpatients with cancer or diabetes, enrollment rates were 68% and 58% respectively with 80% of enrolled participants completing all sessions.16 In the larger cancer-specific RCT, 77% of eligible patients enrolled in the intervention study and 90% of participants received all intervention sessions.11 Notably, in the larger RCT, all sessions were delivered in-person within the context of a hospital admission or pre/post oncology clinic visit.

The ACHD-CARE pilot randomized controlled trial was designed to improve resilience and quality of life in adults with CHD. This 8-session in-person group intervention was delivered to 42 participants. Core intervention components included relaxation, cognitive behavioral, and social skills training. ACHD-CARE was found to be acceptable and valued by participants with a medium effect size for decreasing depressive symptoms. Of note, only half of the participants attended all 8 study sessions, yet 71% attended at least 4 sessions. It was reported that enrollment (~32% enrollment rate) was impacted by barriers to in-person attendance, including transportation and time.18

The Stress Management and Resiliency Training Program- Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (SMART-3RP) was recently piloted in a sample of 12 adults with CHD.19 This 8-week telemedicine-based, psychologist-led, group program focused on mind-body, cognitive behavioral, and positive psychology skills. Among those who enrolled in the study (45% enrollment rate), group session attendance was excellent (≥80%). Results demonstrated intervention feasibility and a medium effect size for improvements in health-related anxiety and resiliency 3-months post-intervention. Participants noted that shorter sessions (i.e., 60 minutes compared to 90 minutes) would be welcomed, as well as more heart disease specific content.19

These successful intervention research programs further informed our design. Specifically, similar to PRISM,11,16 we aimed to develop a brief intervention, but sought to incorporate a social community component through a group-based offering much like ACHD-CARE18 and SMART-3RP19 given the importance of peer support identified by our patients and through larger scale research with the pediatric heart disease population.15,25 Moreover, similarly to SMART-3RP, we sought to make the program as accessible as possible via telemedicine delivery.19

Results

WE BEAT Intervention Delivery

The WE BEAT program was initially designed for delivery via telemedicine-based group format. Adolescent-aged group cohorts consist of approximately 4–10 similarly aged peers with analogous cardiac diagnoses. Groups are conducted via HIPAA-compliant video conferencing technology and facilitated by a licensed psychologist or psychology trainee working under the direct supervision of a licensed psychologist. The intervention program includes five weekly 45-minute sessions. The five modules are detailed below. Each session follows the same outline: (I) Welcome/Check-In, (II) Evidence, (III) Skill Building, (IV) Goal Setting. During the Welcome/Check-In, participants are invited to share via audio or text skills they tried or practiced during the week prior (5 minutes). Research evidence specific to the module theme (5–10 minutes) is then described in a developmentally appropriate way. The Evidence is shared via teen-friendly graphics and media, building “buy-in” for skill development. Participants then learn three evidence-based Skill Building activities specific to the module. In session practice of each skill is facilitated (15 minutes). The group session ends with each participant sharing via audio or text what they liked/disliked and engaging in Goal Setting regarding skill practice.

Mixed media is utilized throughout the program (e.g., videos, audio, polls). Content is specific to the chronic illness and/or heart disease journey. For example, evidence is reviewed regarding mindfulness practice and health impact. A heart journey gratitude story is shared by a pediatric cardiologist with CHD themselves. An accompanying WE BEAT workbook is also provided to participants ahead of the first session. It is recommended that participants use the workbook to set goals, track practice, and keep notes related to sessions as helpful.

WE BEAT Intervention Modules

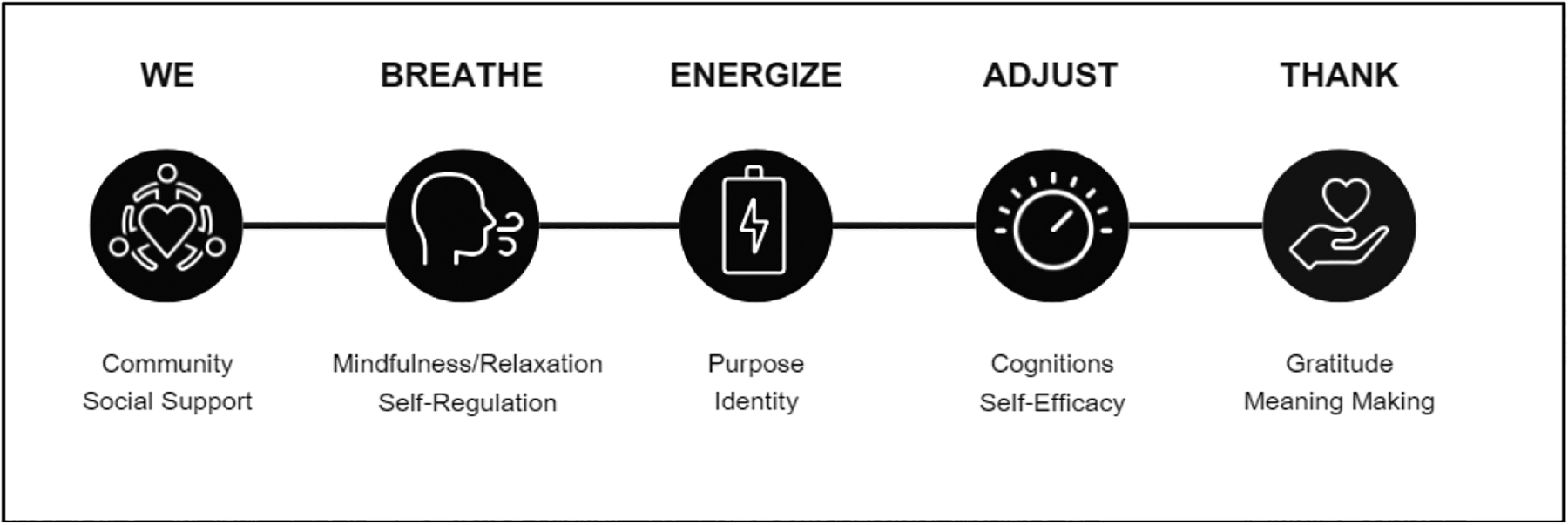

Building upon patient-focused research, resilience theory and successful intervention design, the five WE BEAT modules include: (1) Wellbeing Education, Introduction and Community Building, (2) Breathe, Mindfulness and Relaxation-Based Skills, (3) Energize, Positive Psychology Skills, (4) Adjust, Cognitive Skills Training, and (5) Thank, Gratitude Practice (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overview of WE BEAT Program Modules.

Core components and modules of the WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program.

Wellbeing Education (Module 1).

Peer support has been shown to correlate with higher quality of life41 and resilience.15 While peer support is regularly noted as important to the CHD experience, there is research across other pediatric chronic illness groups to suggest that adolescents do not find disease-specific online forums/pages to be relevant.42 Those who engage in more formalized disease-specific mentoring report high satisfaction.43 As such, the WE BEAT program is centralized on group-based wellbeing education to provide disease-specific peer connection, while also socializing resilience skill-building and processes. Module 1 activities include baseline survey completion, group icebreaker/community building activity, and group sharing on meaning of resilience.

Breathe (Module 2).

Mindfulness is a state of consciousness involving paying attention in the present moment, purposefully and in a non-judgmental way.44,45 Relaxation strategies are one method of scaffolding towards and developing the skill of mindfulness. The mechanism of action through which mindfulness leads to improved wellbeing is thought to be through the shift in perspective or reperceiving that comes with attending in the moment with openness and a non-judgmental attitude. This perspective shift can subsequently contribute to further mechanisms for change, which include values clarification, improved self-regulation, and increased cognitive and emotional flexibility.46 The benefits of mindfulness for children with physical medical conditions have been demonstrated through systematic review, specifically in decreasing depressive and anxiety symptoms.47 Recent meta-analyses have indicated positive influences of mindfulness-based interventions among those with cardiovascular diseases across ages, including moderate to large effects in reducing anxiety, depression, stress, and blood pressure.48 Specifically among adolescents with CHD, a mindfulness-based stress reduction group intervention was associated with decreased illness-related stress and anxiety and improvements in application of skills to real-life stressors.49 Module 2 skill-building activities include instruction and practice in diaphragmatic breathing, a guided imagery experience, and a mindfulness exercise (i.e., word focus).

Energize (Module 3).

Positive psychology principles center on understanding and promoting the conditions, traits, and individual strengths to enhance wellbeing and life satisfaction while also buffering against future distress.50 These principles include, but are not limited to, optimism, self-compassion, and life’s purpose. Efforts to promote these and other positive psychology principles are thought to impact outcomes through mechanisms of both improved intrinsic wellbeing, such as decreasing depression, anxiety, and stress51 as well as promotion of extrinsic wellbeing associated with social relationships, community building, and relationship with broader embedded systems, such as cultural, political, or economic systems.50 Specific to cardiology and heart disease, the benefits of positive psychology in cardiovascular disease include both direct impacts on neurobiological process (e.g., reducing blood pressure) and indirect impacts on health behaviors and utilization of psychological resources, such as likelihood of seeking social support, greater emotion regulation, and uptake of exercise recommendations.1 Module 3 skill-building activities include reflections and group sharing on purpose and passions, as well as brainstorming specific to increasing daily movement.

Adjust (Module 4).

Cognitive behavioral therapy centers on the core premise that dysfunctional thoughts lead to psychological disturbances, and modification of such thoughts can produce improvements in behaviors and emotions.52,53 Through instruction in specific cognitive skills, such as cognitive restructuring, an individual is taught to identify, evaluate, and modify unhelpful or inaccurate cognitions, ultimately improving psychological wellbeing.52 In recent years, therapeutic approaches within the cognitive behavioral tradition (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy) have shifted to include a focus on acceptance-based strategies as well.54 Among children with a chronic medical condition, cognitive behavioral therapy is an effective treatment for anxiety and depression.55 Specific to youth with CHD, a psychosocial intervention incorporated strategies to build cognitive flexibility, including acceptance and cognitive reappraisal, resulted in improved resiliency among adolescents in South Korea.56 Module 4 skill-building activities include introductory instruction in thought challenging, self-talk, and radical acceptance.

Thank (Module 5).

While gratitude can be conceptualized in different ways, dispositional gratitude refers to the “generalized tendency to respond with grateful emotion, by noticing and appreciating one’s positive experiences and achievements.”57 In a recent meta-analysis, dispositional gratitude was found to be moderately positively correlated with aspects of positive wellbeing, including happiness, life satisfaction, and positive affect.57 The impact of gratitude on wellbeing is thought to occur via multiple mechanisms, including positive interpretive biases when appraising benefit,58 improved coping,59 and building positive resources for use in future times of stress.59,60 A recent systematic review found that gratitude-focused interventions are potentially promising for improving several physical health conditions, including subjective sleep quality and glycemic control.61 while another review concluded that gratitude interventions may improve some aspects of cardiovascular health and markers of inflammation.62 Additionally, gratitude may improve health behaviors important to the development and progression of cardiovascular disease, including physical exercise, diet, and medication adherence.63,64 Module 5 activities focus on the practices of self-gratitude, others gratitude and heart-related gratitude

Discussion

The WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program was developed as one of the first resiliency-focused interventions in pediatric heart disease with an overall objective to foster positive psychological wellbeing through a health promotion and prevention lens in an accessible, digital health format while providing access to safe, peer-to-peer community building. A single center feasibility pilot trial of the WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program in telemedicine group-format is currently underway in a sample of 13–18-year-olds with Fontan-palliated CHD. Acceptability results are very encouraging thus far and pilot study results are forthcoming. In addition to pilot research, we envision future directions of this intervention program to include digital-health delivery options, larger scale implementation, effectiveness and mechanistic trials, and age-based and multi-language adaptations.

There has been an increasing call for digital mental health interventions developed via human-centered design to increase accessibility and reduce disparities in care.65 Adolescent use of smartphones is nearly ubiquitous in the United States, with average age of mobile phone acquirement around 11–12 years of age, even among youth from lower-income households.66 Recent 2022 national survey data from the Pew Research Center approximate 95% of U.S. teens have access to a smartphone and 97% of U.S. teens report using the Internet daily (www.pewresearch.org). As such, a WE BEAT responsive website was developed as a first step in expanding this intervention program beyond the telemedicine group format. Initial user co-design, input, and testing of the responsive website with diverse stakeholders is nearly complete. Technical specification design for a WE BEAT app based upon data gathered from the website feedback are underway. Ultimately, the goal of the app would be to reach more patients and families in need, while also aiding in the group-based intervention delivery or allowing users to independently complete the program in a self-directed way via the app.

In addition to larger scale effectiveness and implementation trial research, future mechanistic studies will be needed to better understand change agents within this multicomponent, multi-systemic intervention. This will require large samples of participants followed longitudinally and the use of advanced statistical modeling. Further, the impact of WE BEAT program participation on biomarkers and health outcomes is an exciting future phase of this work. Building upon the multi-system resiliency framework, this would enable investigation of biological processes also at play, as well as improved understanding of correlational and causal pathways between resilience and health outcomes.

Continued co-design with patient and family stakeholders will remain a cornerstone of this program as adaptations are made across diverse age, disease and cultural/language groups. We firmly believe that interventions of this nature are only successful if able to reach across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic strata, especially given demonstrated disparities in mental health diagnosis and treatment among Black and Hispanic youth with CHD.67,68 As such, community-based participatory research practices will be foundational to propelling future iterations of this intervention forward.69

It is important to acknowledge barriers encountered, lessons learned and limitations inherent to this intervention design. Intervention design is often done through a clearly defined and delineated program of research. The ORBIT model, which is regularly referenced by the NIH for the design and optimization of behavioral health interventions, is one such example.70While our approach builds upon some guiding principles of this model, we acknowledge that this intervention was spurred first and foremost by clinical need. The guiding research, while related to resilience, was not solely focused on this intervention design. While these could be appreciated as limitations, we also have learned lessons in the importance of flexibility, responsiveness to patient/family needs, and real-world responsiveness and applicability when developing patient-focused interventions. It has been estimated that it takes 17 years for research to reach patients in clinical settings.71 This is simply too long to wait to address the psychosocial needs of young people living with heart disease. Additionally, for some young people, the group format and telemedicine-based delivery may not be ideal. Scheduling challenges will likely be additional limitations. Further, funding to sustain WE BEAT will likely depend on in-kind support and continued advocacy as current insurance reimbursement standards do not regularly cover preventative, psychoeducation-based mental health care such as this, particularly in the absence of a mental health diagnosis. Despite these limitations, the WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Program begins to address the considerable need for psychosocial health-focused interventions in pediatric heart disease through a positive psychological wellbeing lens as informed by patients, theory, and past research. This initial program design manuscript sets the stage for forthcoming pilot studies, larger multi-site trials and future adaptations.

Financial Support.

This work was supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (M.C., K23HL145096) as well as philanthropic support provided to the University of Michigan Congenital Heart Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. None.

Ethical Standards. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (Common Rule, United States of America) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional committees (University of Michigan).

References

- 1.Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, et al. Positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular disease: JACC health promotion series. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;72(12):1382–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart’s content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological bulletin. 2012;138(4):655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1995;69(4):719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine GN, Cohen BE, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(10):e763–e783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg AR, Yi-Frazier JP. Commentary: Resilience Defined: An Alternative Perspective. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2016;41(5):506–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puterman E, Epel ES, Lin J, et al. Multisystem resiliency moderates the major depression–Telomere length association: Findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2013;33:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epel ES. Psychological and metabolic stress: a recipe for accelerated cellular aging? Hormones. 2009;8:7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Cawthon RM, Freiberg JJ, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Short telomere length, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and early death. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32(3):822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh J-K, Lin M-H, Wang C-Y. Telomeres as therapeutic targets in heart disease. JACC: Basic to Translational Science. 2019;4(7):855–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huzen J, van der Harst P, de Boer RA, et al. Telomere length and psychological well-being in patients with chronic heart failure. Age and ageing. 2010;39(2):223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, McCauley E, et al. Promoting resilience in adolescents and young adults with cancer: Results from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2018;124(19):3909–3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi-Frazier JP, Yaptangco M, Semana S, et al. The association of personal resilience with stress, coping, and diabetes outcomes in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Variable-and person-focused approaches. Journal of health psychology. 2015;20(9):1196–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon JR, Huh J, Kang I-S, Park SW, June T-G, Lee HJ. Relationship between depression and resilience in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Am Heart Assoc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma T, Rohan J. Examination of transition readiness, medication adherence, and resilience in pediatric chronic illness populations: a pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(6):1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glenn T, Cousino MK, Wernovsky G, Schuchardt EL. Resilient Hearts: Measuring Resiliency in Young People With Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2023:e029847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg AR, Yi-Frazier JP, Eaton L, et al. Promoting Resilience in Stress Management: A Pilot Study of a Novel Resilience-Promoting Intervention for Adolescents and Young Adults With Serious Illness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015;40(9):992–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steineck A, Bradford MC, Lau N, Scott S, Yi-Frazier JP, Rosenberg AR. A psychosocial intervention’s impact on quality of life in AYAs with cancer: a post hoc analysis from the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) randomized controlled trial. Children. 2019;6(11):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs AH, Grace SL, Kentner AC, Nolan RP, Silversides CK, Irvine MJ. Feasibility and outcomes in a pilot randomized controlled trial of a psychosocial intervention for adults with congenital heart disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2018;34(6):766–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luberto CM, Wang A, Li R, Pagliaro J, Park ER, Bhatt A. Videoconference-delivered Mind-Body Resiliency Training in Adults with congenital heart disease: A pilot feasibility trial. International Journal of Cardiology Congenital Heart Disease. 2022;7:100324. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacs AH, Brouillette J, Ibeziako P, et al. Psychological outcomes and interventions for individuals with congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2022;15(8):e000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Psychological interventions for people affected by childhood-onset heart disease: A systematic review [press release]. US: American Psychological Association2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassidy AR, Butler SC, Briend J, et al. Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial interventions for individuals with CHD: a research agenda and recommendations from the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative. Cardiology in the Young. 2021:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opotowsky AR, Allen KY, Bucholz EM, et al. Pediatric and Congenital Cardiovascular Disease Research Challenges and Opportunities: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2022;80(23):2239–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickles DM, Lihn SL, Boat TF, Lannon C. A roadmap to emotional health for children and families with chronic pediatric conditions. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cousino MK, Pasquali SK, Romano JC, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on CHD care and emotional wellbeing. Cardiology in the Young. 2021;31(5):822–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs AH, Bendell KL, Colman J, Harrison JL, Oechslin E, Silversides C. Adults with congenital heart disease: psychological needs and treatment preferences. Congenital heart disease. 2009;4(3):139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendall L, Sloper P, Lewin RJ, Parsons JM. The views of young people with congenital cardiac disease on designing the services for their treatment. Cardiology in the Young. 2003;13(1):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross S, Verstappen A. The role of congenital heart disease patient organizations in advocacy, resources, and support across the lifespan. CJC Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steiner JM, Abu-Rish Blakeney E, Corage Baden A, et al. Definitions of resilience and resilience resource use as described by adults with congenital heart disease. International Journal of Cardiology Congenital Heart Disease. 2023;12:100447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chmitorz A, Kunzler A, Helmreich I, et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience – A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2018;59:78–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. European journal of psychotraumatology. 2014;5(1):25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kichler JC, Kaugars AS. Topical Review: Applying Positive Development Principles to Group Interventions for the Promotion of Family Resilience in Pediatric Psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015;40(9):978–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masten AS. 113C6Resilience in Developmental Systems: Principles, Pathways, and Protective Processes in Research and Practice. In: Ungar M, ed. Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change: Oxford University Press; 2021:0. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ungar M, Theron L. Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masten AS, Lucke CM, Nelson KM, Stallworthy IC. Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2021;17:521–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American psychologist. 2001;56(3):227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Resilience in development: Progress and transformation. Developmental psychopathology. 2016;4(3):271–333. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ungar M, Theron L, Höltge J. Multisystemic approaches to researching young people’s resilience: Discovering culturally and contextually sensitive accounts of thriving under adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 2023:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masten W, Wright M. Resilience over the lifespan. Handbook of adult resilience. 2009:213–237. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, Barton KS, et al. Hope and benefit finding: Results from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2019;66(1):e27485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luyckx K, Missotten L, Goossens E, Moons P, Investigators i-D. Individual and contextual determinants of quality of life in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51(2):122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Pelt PA, Drossaert CHC, Kruize AA, Huisman J, Dolhain RJEM, Wulffraat NM. Use and perceived relevance of health-related Internet sites and online contact with peers among young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology. 2015;54(10):1833–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stinson J, Ahola Kohut S, Forgeron P, et al. The iPeer2Peer program: a pilot randomized controlled trial in adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2016;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2003;84(4):822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabat-Zinn J Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hachette UK; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of clinical psychology. 2006;62(3):373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes O, Shelton KH, Penny H, Thompson AR. Living With Physical Health Conditions: A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Children, Adolescents, and Their Parents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2023;48(4):396–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marino F, Failla C, Carrozza C, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for physical and psychological wellbeing in cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sciences. 2021;11(6):727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freedenberg VA, Hinds PS, Friedmann E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and group support decrease stress in adolescents with cardiac diagnoses: a randomized two-group study. Pediatric cardiology. 2017;38:1415–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alex Linley P, Joseph S, Harrington S, Wood AM. Positive psychology: Past, present, and (possible) future. The journal of positive psychology. 2006;1(1):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carr A, Finneran L, Boyd C, et al. The evidence-base for positive psychology interventions: a mega-analysis of meta-analyses. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2023:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beck AT, Haigh EA. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: the generic cognitive model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beck JS, Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy : basics and beyond. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayes SC, Hofmann SG. The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):245–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bennett S, Shafran R, Coughtrey A, Walker S, Heyman I. Psychological interventions for mental health disorders in children with chronic physical illness: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(4):308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee S, Lee J, Choi JY. The effect of a resilience improvement program for adolescents with complex congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16(4):290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Portocarrero FF, Gonzalez K, Ekema-Agbaw M. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;164:110101. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wood AM, Maltby J, Stewart N, Linley PA, Joseph S. A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion. 2008;8(2):281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):890–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1367–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boggiss AL, Consedine NS, Brenton-Peters JM, Hofman PL, Serlachius AS. A systematic review of gratitude interventions: Effects on physical health and health behaviors. J Psychosom Res. 2020;135:110165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jans-Beken L, Jacobs N, Janssens M, et al. Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020;15(6):743–782. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X, Song C. The impact of gratitude interventions on patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1243598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cousin L, Redwine L, Bricker C, Kip K, Buck H. Effect of gratitude on cardiovascular health outcomes: a state-of-the-science review. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021;16(3):348–355. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stiles-Shields C, Cummings C, Montague E, Plevinsky JM, Psihogios AM, Williams KD. A call to action: using and extending human-centered design methodologies to improve mental and behavioral health equity. Frontiers in Digital Health. 2022;4:848052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun X, Haydel KF, Matheson D, Desai M, Robinson TN. Are mobile phone ownership and age of acquisition associated with child adjustment? A 5-year prospective study among low‐income Latinx children. Child development. 2023;94(1):303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gonzalez VJ, Kimbro RT, Cutitta KE, et al. Mental Health Disorders in Children With Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatrics. 2021;147(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonzalez VJ, Kimbro RT, Shabosky JC, et al. Racial Disparities in Mental Health Disorders in Youth with Chronic Medical Conditions. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2023:113411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopez KN, Baker-Smith C, Flores G, et al. Addressing social determinants of health and mitigating health disparities across the lifespan in congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2022;11(8):e025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychology. 2015;34(10):971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rubin R It Takes an Average of 17 Years for Evidence to Change Practice—the Burgeoning Field of Implementation Science Seeks to Speed Things Up. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1333–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]