Abstract

The leaves of Cyclocarya paliurus (Batalin) Iljinskaja, an endemic tree with a scattered distribution in subtropical China, are rich in flavonoids with beneficial, health-promoting properties. To understand the impact of environment and genetic similarity on the variation pattern of flavonoids in this species, we analyzed C. paliurus germplasm resources from 26 different populations previously sampled from the main distribution area. Environmental, genetic and biochemical data was associated by genetic structure analysis, non-parametric tests, correlation analysis and principal component analysis. We found that populations with higher flavonoid contents were distributed at higher elevations and latitudes and fell into two groups with similar genetic diversities. Significant accumulations of isoquercitrin and kaempferol 3-O-glucoside were detected in the higher flavonoid-content resources. In addition, the genetic clusters with higher flavonoid contents exhibited broader environmental-adaptive capacities. Even in the presence of environmental factors promoting C. paliurus flavonoid accumulation, only those populations having a specific level of genetic similarity were able to exploit such environments.

Keywords: Flavonoid variation, Association analysis, Genetic similarity, Cyclocarya paliurus, Environment

Subject terms: Natural variation in plants, Secondary metabolism

Introduction

Cyclocarya paliurus (Batalin) Iljinskaja, a tree species restricted to scattered locations in subtropical China1, has leaves containing abundant, human health-promoting compounds, including phenolics, triterpenoids, and polysaccharides. For example, the leaves of this tree are rich in beneficial secondary metabolites, mainly flavonoids and triterpenoids, that help inhibit conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipemia2–4. Studies focused on the bioactivity and accumulation of flavonoids in C. paliurus leaves, which are exploited for these compounds, have revealed that flavonoid contents of C. paliurus resources vary greatly. Despite this finding, the relationship between genetic similarity and the variation pattern of flavonoids in this species remains unclear.

Studies of the mechanisms underlying flavonoid accumulation in plants have shown that environmental factors, especially temperature and UV radiation, play important roles in this process. For instance, the concentration of non-anthocyanidin flavonoids in leaves of Silene vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae) varies by elevation, and fruit flavonol levels in grape increase with increasing water stress5. In C. paliurus, our earlier research found that UV radiation and low temperature significantly promote flavonoid accumulation6. In addition to environmental factors, we have also previously analyzed genotypic influence contributing to the regulation of C. paliurus flavonoid accumulation4, but the relative role of these two competing factors in C. paliurus has not yet been resolved. In particular, one investigation found that environmental effects were more important than the influence of genotype7, whereas another determined that flavonoids were mainly affected by genotype and genotype × environment8. Consensus has thus not been achieved on the importance of genotype–environment interactions on the variation pattern of secondary metabolites in C. paliurus.

In the present study, we therefore aimed to explore the effect of genotype × environment on the pattern of C. paliurus flavonoid accumulation. To achieve this objective, we carried out an association analysis of genetic similarity, environmental distribution, and flavonoid composition using C. paliurus germplasm resources collected in our previous studies from the main distribution area of the species.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

According to our previous work, C. paliurus leaf samples were collected from 12 provinces in southern China, which covered most of the natural distribution area of the species C.4,8. With the support of local research institutions, 316 accessions of 26 different populations were collected across a wide expanse of southern China in 2014 (24.46–33.36°N, 103.78–121.22°E; 400–1,770 m elevation). Mature leaves were sampled in October from dominant or subdominant branches of trees (> 20 years old) and then processed (dried and ground) for determination of flavonoids. Besides, the samples for further DNA analysis were transferred in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C4. The germplasm resources were preserved in C. paliurus germplasm resources garden of Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province. The leave samples were preserved in the public herbarium of Nanjing Forestry University and other researchers were able to access the samples by applying for permission from the research team. The voucher number for all samples were referred to Li et al.4 including H29, JY2, SS1, JY3, NH22, YW21, BT24, BL23, GL25, GZ26, JQ6, QJ4, SW5, QL9, QJ10, TS7, FS13, LF14, LF14(2), PK11, SM12, JX17, JJ18, FD16, M20, GQ19. The germplasms were identified by Caowen Sun and relevant permissions to collect the germplasms were provided by Forestry Bureau of Jiangsu Province.

Determination of flavonoids

Leaf powder (2 g per sample) was subjected to Soxhlet extraction for 2 h at 90 °C with 80% ethanol and condensed to 10 mL. The mixture was then fully shaken and centrifuged using a refrigerated centrifuge (3-18KS; Sigma, Aachen, Germany) for 15 min at 8,000 r/min. The supernatants were filtered by 0.22 µm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter and detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent 1200 series, Waldbronn, Germany)9,10. The detector, 2489 ultraviolet detector, the wavelength, 205 nm. Volume injected, 10 uL. The mobile phase contained 0.01% formic acid in acetonitrile and 0.01% formic acid in water, and the gradient program was set according to Liu et al.11. Concentration of the standard samples, 0.8mg/mL. The standard samples were used according to previous researches on flavonids of C. paliurus9,10. An X-Bridge C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm) was used for flavonoid determination (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), and a stepwise elution program was applied as described previously9,10. Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, isoquercitrin, and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside reference standards were obtained from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co. (Shanghai, China), and a kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside reference standard was obtained from China Pharmaceutical University (Nanjing, China)10. The content of individual flavonoids was calculated using external calibration curves according to Cao et al., (2017), and total flavonoids were determined as the sum of these individuals9,10.

Environmental data

The longitude, latitude, and elevation of each sampling plot were measured with a GPS instrument (JUNO SCSD, Trimble, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Other environmental data, including rainfall, temperature, sunlight, and number of frost-free days, were obtained from ClimateAP (http://climateap.net/)11.

Genetic similarity analysis

According to the protocol described in our previous study4, total genomic DNA was extracted and then PCR amplified using nine inter-simple sequence repeat primers and six simple sequence repeat primers4. The PCR results were checked by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Genetic diversity data were obtained in our previous study according to Li et al.4, and STRUCTURE 2.3.4. was used to cluster the C. paliurus populations into groups based on genetic similarity4,12.

Analysis of suitable growing areas based on genetic similarity

Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to explain the environmental distribution of C. paliurus populations. In addition, different genetic clusters were marked separately on the PCA biplot. Non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis) was then conducted between genetic clusters to identify significant environmental differences.

Variation in individual flavonoids

Another PCA was performed using data on seven flavonoids from 316 accessions. The clusters were then marked separately on the PCA biplot according to genetic similarity. Multiple comparisons and non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis) were conducted between genetic clusters to analyze differences in flavonoid composition.

Interaction analyses between genotype and environmental factors

According to the results of the correlation analysis (Pearson) conducted between environmental factors and flavonoid composition, we performed another PCA using correlated environmental, genetic cluster, and flavonoid data to describe the interaction of genotype and environment on flavonoid variation patterns. Statistical analyses, including variance and PCA association analyses, were performed with SPSS 19.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Accumulation pattern of individual flavonoids

We measured the contents of seven flavonoid compounds in the 316 C. paliurus accessions (Table 1). Median contents of quercetin-3-O-glucuronide (1.52 mg/g), kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide (1.26 mg/g), and kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside (1.37 mg/g) were much higher than those of quercetin-3-O-galactoside (0.47 mg/g), isoquercitrin (0.29 mg/g), kaempferol 3-O-glucoside (0.2 mg/g), and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside (0.17 mg/g). Isoquercitrin and kaempferol 3-O-glucoside had the highest coefficients of variation—1.02 and 1.43, respectively. Variation coefficients of all other flavonoids were less than 0.8, and the coefficient for total flavonoid content was 0.51. Agreed with previous researches, all these flavonoids were previously identified and exhibited similar variation pattern in C. paliurus9,10.

Table 1.

Flavonoid contents of leaves of 316 Cyclocarya paliurus accessions (dry weight).

| Flavonoids | Limit of quantitation (ng/ml) | Minimum (mg/g) | Maximum (mg/g) | SD | Coefficient of variation | Median (Quartile) (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin-3-O-Glucuronide | 128.74 | 0 | 5.97 | 1.28 | 0.71 | 1.52(0.78 ~ 2.64) |

| Quercetin-3-O-Galactoside | 174.17 | 0.03 | 2.65 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.47(0.25 ~ 0.76) |

| Quercetin-3-O-Rhamnoside | 199.32 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 0.17(0.1 ~ 0.28) |

| Isoquercitrin | 192.52 | 0.01 | 2.97 | 0.43 | 1.02 | 0.29(0.15 ~ 0.5) |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Glucuronide | 153.14 | 0.12 | 6.87 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.26(0.86 ~ 1.83) |

| Kaempferol 3-O-Glucoside | 187.37 | 0 | 3.98 | 0.60 | 1.43 | 0.2(0.14 ~ 0.41) |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Rhamnoside | 211.81 | 0 | 4.84 | 0.98 | 0.64 | 1.37(0.69 ~ 2.21) |

| Total Flavonoid | – | 0.57 | 18.06 | 3.26 | 0.51 | 5.89(3.72 ~ 8.28) |

SD = standard deviation

A PCA was carried out on the flavonoid contents of 316 C. paliurus leaf samples. As shown in Table 2, seven individual flavonoids were responsible for 72.3% of the variation in total flavonoid content (52.41% and 19.93% from principal components 1 and 2, respectively). Most information on variation in flavonoid content was included in the PCA model in which extracted coefficients were higher than 0.7. A PCA plot was accordingly constructed to visualize the structure of the data (Fig. 1). According to this plot, six flavonoid compounds exhibited the same variation pattern as that of total flavonoids; the exceptions were isoquercitrin and kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, which had higher coefficients of variation (Table 2).

Table 2.

PCA explaining variation in total flavonoid content.

| Extract coefficient | PCA1 | PCA2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaempferol-3-O-Rhamnoside | 0.72 | 0.83 | − 0.19 |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Glucuronide | 0.53 | 0.64 | − 0.34 |

| Kaempferol 3-O-Glucoside | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.85 |

| Quercetin-3-O-Glucuronide | 0.80 | 0.80 | − 0.41 |

| Quercetin-3-O-Galactoside | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.21 |

| Quercetin-3-O-Rhamnoside | 0.67 | 0.81 | − 0.10 |

| Isoquercitrin | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| Total Flavonoid | 0.98 | 0.99 | − 0.04 |

| Total variance of interpretation (%) | 52.41 | 19.93 |

Fig. 1.

PCA biplot of C. paliurus flavonoid contents.

F1, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide; F2, quercetin-3-O-galactosideisoquercitrin;F3, kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide; F4, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside;F5, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside; F6, kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside;FALL, total flavonoids.

Distributional characteristics of C. paliurus populations

To analyze the association between genotype and population distribution, we used our previous genetic similarity clusters according to Li et al. (2017) with the screening primers4. Genetic diversity data from 26 C. paliurus populations was processed by a model-based Bayesian analysis to obtain the most appropriate genotype clusters4. As shown in Table 3, all C. paliurus populations were clustered into four groups on the basis of genetic similarity. Genetic cluster 1 comprised 10 C. paliurus populations from Shanxi, Hunan, Hubei, and Guangxi provinces. Six C. paliurus populations, from Anhui and Guizhou provinces, were grouped into genetic cluster 2, and eight natural populations from Jiangxi, Zhejiang, and Fujian provinces constituted genetic cluster 3. Genetic cluster 4 contained only two populations, both from Sichuan Province.

Table 3.

Genetic clustering and environmental characteristics of C. paliurus populations.

| Genetic clusters | Code | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation | Annual mean temperature | Annual precipitation | Annual sunlight | Frost-free days(day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°N) | (°E) | (m) | (°C) | (mm) | (hour) | |||

| 1 | H29 | 33.36 | 105.87 | 1200 | 13 | 714 | 1558.3 | 236 |

| 1 | JY2 | 28.88 | 110.33 | 670 | 14.8 | 1492 | 1306 | 286 |

| 1 | SS1 | 26.37 | 110.13 | 1000 | 16.7 | 1320 | 1348.9 | 304 |

| 1 | JY3 | 24.92 | 112.03 | 845 | 17.4 | 1502 | 1758 | 308 |

| 1 | NH22 | 29.88 | 110.42 | 1125 | 11.3 | 1499 | 1342 | 245 |

| 1 | YW21 | 30.19 | 110.9 | 969 | 12.6 | 1650 | 1533 | 240 |

| 1 | BT24 | 24.46 | 106.34 | 1448 | 15.6 | 1364 | 1906.6 | 357 |

| 1 | BL23 | 24.61 | 104.95 | 1770 | 16.7 | 1212 | 1569.3 | 357 |

| 1 | GL25 | 25.62 | 109.89 | 606 | 14.5 | 1629 | 1309 | 314 |

| 1 | GZ26 | 25.92 | 110.38 | 850 | 15.5 | 1580 | 1275 | 300 |

| 2 | JQ6 | 30.15 | 118.89 | 730 | 12.1 | 1726 | 1920 | 233 |

| 2 | QJ4 | 30.23 | 118.45 | 610 | 13.8 | 1657 | 1784.1 | 240 |

| 2 | SW5 | 31.02 | 116.54 | 770 | 12.3 | 1606 | 1969 | 224 |

| 2 | QL9 | 26.34 | 109.24 | 727 | 16.1 | 1311 | 1317.9 | 277 |

| 2 | QJ10 | 26.37 | 108.38 | 1240 | 15.1 | 1265 | 1236.3 | 300 |

| 2 | TS7 | 27.35 | 108.11 | 1239 | 13.3 | 1256 | 1232.9 | 316 |

| 3 | FS13 | 29.76 | 121.22 | 715 | 14 | 1527 | 1850 | 232 |

| 3 | LF14 | 27.91 | 119.19 | 1200 | 11.8 | 2119 | 1849.8 | 263 |

| 3 | LF14(2) | 27.88 | 119.79 | 915 | 13.9 | 1913 | 1764.4 | 285 |

| 3 | PK11 | 27.93 | 118.76 | 930 | 15.8 | 1998 | 1900 | 254 |

| 3 | SM12 | 26.57 | 116.93 | 564 | 17.4 | 1821 | 1788.6 | 261 |

| 3 | JX17 | 28.16 | 114.52 | 827 | 13.5 | 1655 | 1600.4 | 247 |

| 3 | JJ18 | 26.51 | 114.1 | 967 | 13.2 | 1816 | 1511 | 241 |

| 3 | FD16 | 27.63 | 114.53 | 565 | 15.3 | 1691 | 1251 | 270 |

| 4 | M20 | 28.97 | 103.78 | 1200 | 17.3 | 1332 | 968 | 332 |

| 4 | GQ19 | 32.42 | 104.86 | 1570 | 14.1 | 1027 | 1292 | 243 |

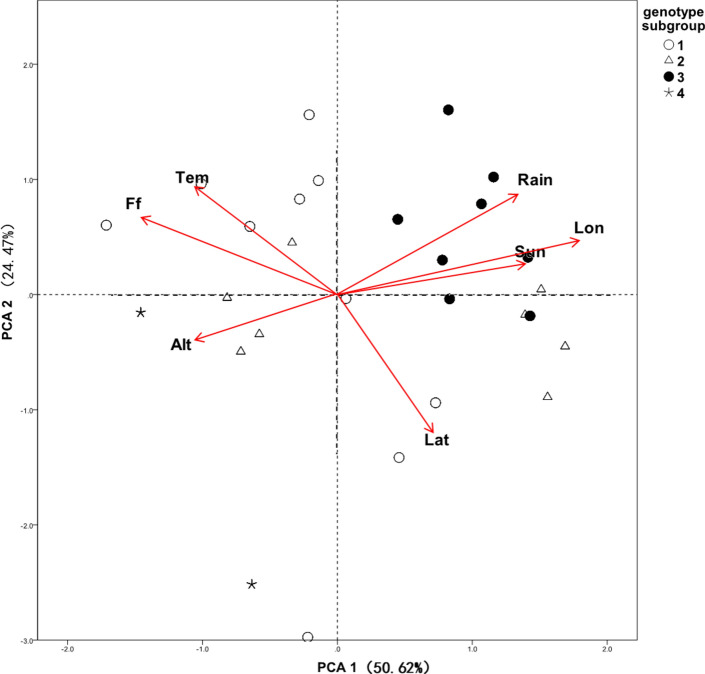

To look for differences in the environmental adaptability of C. paliurus genetic clusters, we performed PCA modeling on the population geographical data. Information on variation was successfully extracted from all environmental variables (Table 3). The first two principal components explained 75.09% of the environmental variation, and the extracted variation coefficients of most environmental variables were greater than 0.7 (Table 4). As shown in the PCA biplot in Fig. 2, the four C. paliurus genetic clusters had obviously different distributional characteristics. Members of genetic cluster 3 were almost exclusively distributed in more eastern locations with high annual mean rainfall. The two populations in genetic cluster 4 inhabited high elevations. The remaining populations, in clusters 1 and 2, were distributed in relatively moderate environments.

Table 4.

PCA explaining variation in environment variables.

| Extract coefficient | PCA1 | PCA2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | 0.83 | 0.33 | − 0.85 |

| Longitude | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.28 |

| Elevation | 0.58 | − 0.67 | − 0.34 |

| Annual mean temperature | 0.70 | − 0.63 | 0.55 |

| Annual precipitation | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.54 |

| Annual sunlight | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.15 |

| Annual frost free days | 0.90 | − 0.85 | 0.42 |

| Total variance of interpretation (%) | 50.62 | 24.47 |

Fig. 2.

PCA biplot of C. paliurus distributional environments.

Tem, annual mean temperature; Rain, annual precipitation; Lat, latitude; Lon, longitude; sun, annual hours of sunlight; Alt, elevation; Ff, number of frost-free days.

Non-parametric testing was performed to verify relationships between genetic clusters and environmental variables (Table 5). This test revealed that the longitude of distribution and annual precipitation were significantly different among genetic clusters (P < 0.01). Compared with the locations of genetic cluster 1 (106.34°E–110.42°E), populations from genetic cluster 3 were almost all distributed in more eastern longitudes (114.52°E–119.08°E), a difference that was significant at the P < 0.01 level. Members of genetic cluster 2 were distributed somewhere in between, at a median longitude of 109.24°E (108.38–116.54°E), and not significantly different from genetic clusters 1 or 3. Genotype cluster 4 was located in westernmost areas (103.9–104.86°E). In regard to rainfall, members of genetic cluster 3 were located in areas of higher annual rainfall (1,816 mm) compared with genetic cluster 1 (1,495 mm) (P < 0.01), but rainfall in these two clusters was not statistically significantly different from that experienced by genetic cluster 2. Areas occupied by populations in genetic cluster 4 had the lowest annual rainfall (1,027–1,332 mm).

Table 5.

Non-parametric tests of differences in environmental variables among genetic clusters.

| Environment factors | Sig | Genetic cluster 1 | Genetic cluster 2 | Genetic cluster 3 | Genetic cluster 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | 0.30 | ||||

| Longitude | 0.00 | 110.13(106.34 ~ 110.42)Aa | 109.24(108.38 ~ 116.54)ABab | 116.93(114.52 ~ 119.08)Bb | 103.9 ~ 104.86 |

| Elevation | 0.11 | ||||

| Annual mean temperature | 0.57 | ||||

| Annual mean rainfall | 0.00 | 1495.5(1293 ~ 1592.25) Aa | 1311(1256 ~ 1657) ABa | 1818(1664 ~ 1976.75) Bb | 1027 ~ 1332 |

| Annual sunlight | 0.07 | ||||

| Frost-free days | 0.20 |

Different lowercase and uppercase letters indicate a significant difference in an environmental factor among genotypes at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 levels, respectively.

Correlation analysis between genetic similarity and environment

To further study the pattern of flavonoid variation among C. paliurus germplasm resources, we marked genetic clusters on the flavonoid PCA biplot shown in Fig. 3. We observed that C. paliurus populations with higher kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside contents were all members of genetic clusters 1 and 4, whereas total flavonoid content did not differ significantly among the four genetic clusters (Fig. 3). We thus inferred that flavonoid composition was more variable than total flavonoid content among genetic clusters.

Fig. 3.

PCA biplot of flavonoid contents of C. paliurus genetic clusters.

F1, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide; F2,quercetin-3-O-galactosideisoquercitrin;F3, kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide; F4, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside;F5, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside;F6, kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside;FALL, total flavonoids.

Next, a non-parametric test was conducted to assess differences in flavonoid composition among genetic clusters (Table 6). The contents of four flavonoids, namely, isoquercitrin, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, and kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside, were all significantly different among genetic clusters, whereas quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, and kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide accumulations could not be differed based on genetic groups. Genetic cluster 4 had the highest total flavonoid content (median 8.27 mg/g), which was significantly different from that of the other clusters (P < 0.05). In regard to individual flavonoids, isoquercitrin (median 0.44 mg/g), kaempferol 3-O-glucoside (median 0.92 mg/g), and kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside (median 2.33 mg/g) contents of genetic cluster 4 were all significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in other groups. In addition, kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside was more abundant in cluster 1 (median 1.78 mg/g; 1.06–2.35 mg/g) than in clusters 2 and 3. Clusters 2 and 3 had the lowest total flavonoid contents: 5.31 mg/g (3.74–7.59 mg/g) and 5.1 mg/g (3.34–7.18 mg/g), respectively. Isoquercitrin, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, and kaempferol-3-O-rhamnosidepterocaryoside contents of clusters 2 and 3 were generally lower as well.

Table 6.

Non-parametric tests of differences in C. paliurus flavonoid contents among genetic clusters.

| Flavonoids | Significance | Median (Quartile) (mg/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic cluster 1 | Genetic cluster 2 | Genetic cluster 3 | Genetic cluster 4 | ||

| Quercetin-3-O-Glucuronide | 0.07 | 1.51(0.8 ~ 2.78) | 1.72(1.02 ~ 2.71) | 1.13(0.74 ~ 1.77) | 1.8(0.4 ~ 3.11) |

| Quercetin-3-O-Galactoside | 0.14 | 0.43(0.2 ~ 0.66) | 0.52(0.32 ~ 0.77) | 0.54(0.23 ~ 0.87) | 0.39(0.26 ~ 0.62) |

| Isoquercitrin | 0 | 0.25(0.12 ~ 0.49) ABa | 0.26(0.13 ~ 0.43)Aa | 0.27(0.15 ~ 0.5) ABa | 0.44(0.27 ~ 1.01) Bb |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Glucuronide | 0.62 | 1.23(0.86 ~ 1.91) | 1.29(0.91 ~ 1.79) | 1.17(0.8 ~ 1.72) | 1.29(0.81 ~ 2.33) |

| Kaempferol 3-O-Glucoside | 0 | 0.19(0.13 ~ 0.44) Aa | 0.17(0.13 ~ 0.23)Aa | 0.2(0.14 ~ 0.31) Aa | 0.92(0.21 ~ 1.38) Bb |

| Quercetin-3-O-Rhamnoside | 0 | 0.2(0.13 ~ 0.29) Aab | 0.16(0.07 ~ 0.26)Aa | 0.13(0.08 ~ 0.23)Aab | 0.22(0.16 ~ 0.3) Ab |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Rhamnoside | 0 | 1.78(1.06 ~ 2.35) Bb | 1.05(0.51 ~ 1.97)Aa | 0.98(0.58 ~ 1.72) Aa | 2.33(1.22 ~ 3.18) Bc |

| Total Flavonoid | 0 | 6.69(4.01 ~ 8.78) ABa | 5.37(3.74 ~ 7.59)Aa | 5.1(3.34 ~ 7.18) Aa | 8.27(6.1 ~ 10.57) Bb |

Different lowercase and uppercase letters indicate a significance difference in flavonoid content among genotypes at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 levels, respectively.

We also performed a correlation analysis, which revealed some weak correlations between flavonoid contents and various environmental factors (Table 7). Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside content was significantly correlated with several environmental factors, including latitude (R = 0.45, P < 0.01), longitude (R = − 0.33, P < 0.01), elevation (R = 0.32, P < 0.01), and annual rainfall (R = − 0.41, P < 0.01). A weak correlation was also uncovered between total flavonoid content and latitude (R = 0.30, P < 0.01). Absolute values of all other correlation coefficients were less than 0.25.

Table 7.

Correlations between environmental factors and flavonoid contents of C. paliurus accessions.

| Lat | Lon | Alt | Tem | Rain | Sun | Ff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin-3-O-Glucuronide | 0.16** | − 0.02 | 0.04 | − 0.15** | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Quercetin-3-O-Galactoside | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | − 0.12* | − 0.01 | 0.07 | − 0.07 |

| Isoquercitrin | 0.21** | − 0.25** | 0.19** | − 0.02 | − 0.24** | − 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Glucuronide | 0.21** | − 0.05 | 0.05 | − 0.17** | − 0.03 | − -0.07 | − 0.06 |

| Kaempferol 3-O-Glucoside | 0.45** | − 0.33** | 0.32** | − 0.05 | − 0.41** | − 0.16** | − 0.11 |

| Quercetin-3-O-Rhamnoside | 0.18** | − 0.10 | 0.06 | − 0.09 | − 0.02 | − 0.05 | − 0.05 |

| Kaempferol-3-O-Rhamnoside | 0.18** | − 0.23** | 0.09 | 0.05 | − 0.07 | − 0.18** | 0.13* |

| Total Flavonoid | 0.30** | − 0.19** | 0.15** | − 0.12* | − 0.12* | − 0.10 | 0.01 |

Asterisks indicate significant correlations (*, P < 01; **, P < 0.01).

To analyze the effect of environment–genetic interactions on flavonoid variation in detail, we conduct two additional PCAs (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4a, the first PCA, which covered four environmental variables and the two most variable flavonoids (kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside), revealed that latitude, longitude, elevation, and annual number of frost-free days explained 81.6% of the total variation in flavonoid content. According to this analysis, C. paliurus resources with higher kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside contents mainly inhabited higher-latitude, higher-elevation sites and mostly belonged to genetic clusters 1 and 4, corresponding to the second quadrant. The C. paliurus resources with higher kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside contents also had higher total flavonoid contents (Fig. 4b). This result confirms that higher latitudes and elevations promote flavonoid accumulation. Furthermore, C. paliurus accessions in genetic cluster 1 with low total flavonoid contents were collected from sites at relatively low latitudes and elevations, whereas high-flavonoid members of genetic cluster 1 inhabited higher latitudes and elevations. Similarly, most high-flavonoid resources from cluster 4 were collected from higher-latitude, higher-elevation sites, and accessions with low flavonoid contents in genetic clusters 2 and 3 came from sites at lower latitudes and elevations.

Fig. 4.

PCA biplot of C. paliurus flavonoid contents and environmental distributions, (a) PCA biplot of F3, F5, and environmental factors. (b) PCA biplot of FALL and environmental factors.

Discussion

In this study, C. paliurus resources were grouped by genetic similarity, and these clusters were found to be well correlated with their geographical distributions. Li (2017) previously analyzed the genetic diversity of 26 C. paliurus populations and attempted to divide them into groups by UPGMA and Bayesian clustering methods4. In the present study, we analyzed the relationships of these 26 populations by Bayesian clustering, which resulted in four groups based on genetic similarity, and subjected them to further analysis4. An association analysis between environmental factors and genetic clusters clearly explained the distributional characteristics of the four C. paliurus clusters. Genetic clusters 1 and 2 had the widest distributional range. Accessions in genetic cluster 3 were collected from sites at more eastern longitudes with higher rainfall, whereas members of genetic cluster 4 were mostly located at higher elevations.

We found that the pattern of flavonoid accumulation was significantly different among genetic clusters. In particular, genetic cluster 4 and some accessions from genetic cluster 1 had the highest isoquercitrin, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, and kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside contents. Flavonoid contents of the C. paliurus accessions ranged from 0.57 to 18.06 mg/g, thus requiring the evaluation and screening of these germplasm resources. Fang et al. (2011) previously reported that genotype has a significant influence on flavonoid accumulation in C. paliurus in homogeneous environments13. Likewise, Cao et al. (2018) detected significant differences in flavonoid composition among 33 C. paliurus families9. Liu et al. (2016) also found that flavonoid accumulation was significantly different among C. paliurus samples of different provenance14. Research on kale, potato, and wheat has also uncovered genotypic effects on flavonoid accumulation15–17 .

In contrast to the above-mentioned genotypic effects, significant correlations between high flavonoid contents and environmental factors have been detected in some plant species. In the present study, despite correlation between environmental factors and flavonoid contents of general populations was very limited, accessions with high flavonoid contents were collected from higher elevations at higher latitudes, which means that the combination of UV radiation and low temperature might promote flavonoid accumulation in C. paliurus leaves. Our findings are consistent with the results of Bhatia (2018), who reported that light and low temperature induce flavonol synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana18. In addition, Li et al. (2013) found that phenylalanine and flavonoid biosynthesis are promoted in sun-exposed apple peels19. Berardi (2016) uncovered a strong positive correlation between leaf non-anthocyanidin flavonoid concentration and elevation in Silene vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae)20. Furthermore, Sampaio et al. (2016) have concluded that levels of phenolics (including flavonoids) in Tithonia diversifolia are influenced by rainfall and temperature21. We also previously found that environmental factors significantly regulate C. paliurus flavonoid accumulation6. In the present study, only genetic clusters 1 and 4 were located in regions of higher elevation and latitude, thus indicating that genotype adaptability to environmental stress also needs to be considered.

Studies on the relative roles of genotype and environment in the regulation of flavonoid accumulation in C. paliurus have yielded conflicting results. In a field trial across four sites with 12 genotypes, Deng (2015) found that environment had a stronger effect than genotype on the flavonoid accumulation of C. paliurus families7. In a field trial of 13 C. paliurus families, however, Zhou (2021) determined that C. paliurus leaf flavonoid and triterpenoid contents, despite environmental regulation, were mainly affected by family-level genotype and genotype × environment8. Most of these studies investigated genotypic differences between populations or families, whereas we tried to uncover a general correlation between flavonoid variation patterns and genetic similarity. Although high elevation and latitude promote flavonoid accumulation in C. paliurus, only genetic clusters 1 and 4 were found to be distributed at higher elevations and latitudes. We thus speculate that genetic clusters 1 and 4 had higher environmental adaptive capacities and thus higher flavonoid contents in specific environments.

Differences in flavonoid accumulation between C. paliurus genotypes may be due to the differential expression of enzymes regulating flavonoid metabolic pathways. In previous research, Wang et al. (2017) discovered that wild, red-fleshed apples had much higher flavonoid contents than cultivated ones, which was possibly due to MYB transcription factors of wild, red-fleshed apples promoting proanthocyanidin and flavonol synthesis22. Differences in glucosyltransferase expression between genotypes may also be responsible for flavonoid natural variation patterns. Xie et al. (2022) have identified a flavonol 3-O-glucosyltransferase, PpUGT78T3, which promotes flavonol glycosylation in peach in response to UV-B irradiation23. Liang et al. (2018) have found that melatonin regulates flavonoid biosynthesis and enhances the expression of the flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase24. Finally, Zenoni et al. (2017) have reported that 3-O-glucosyltransferase is upregulated during fruit maturation in grape. More research is thus needed to identify the mechanism regulating differences in flavonoid content among C. paliurus genotypes25,26.

Conclusions

In this study, four genetic clusters of C. paliurus germplasm resources exhibited significantly different geographical distribution patterns. The four C. paliurus genetic clusters also had contrasting flavonoid compositions and accumulation patterns. In regard to specific flavonoids, significant accumulations of kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside were detected in high-flavonoid genetic clusters. Even though a higher flavonoid content was significantly correlated with environmental factors, only certain genetic clusters accumulated more flavonoids. In those clusters, a wider distributional range and a stronger adaptability to stress might be responsible for their higher flavonoid contents.

Author contributions

Caowen Sun wrote the main manuscript text. Yanni Cao, Xiaochun Li, Shengzuo Fang, Wanxia Yang and Xulan Shang provided experimental materials. Yanni Cao and Xiaochun Li finished the experiment.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32201541), the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangsu Province (BE2019388), Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and the Doctorate Fellowship Foundation of Nanjing Forestry University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due follow-up studies are ongoing but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. paliurus collecting statement, We have permission to collect C. paliurus resources. And the permissions were obtained from local forestry institutions. The collecting resources were deposited in the silviculture laboratory in Nanjing Forestry University and identified by Yanni Cao and Xiaochun Li.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Caowen Sun and Yanni Cao.

References

- 1.Manchester, S. R., Chen, Z.-D., An-Ming, Lu. & Uemura, K. Eastern Asian endemic seed plant genera and their paleogeographic history throughout the Northern Hemisphere. J. Syst. Evol. 47 (1), 42. 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2009.00001.x (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurihara, H., Asami, S., Shibata, H., Fukami, H. & Tanaka, T. Hypolipemic effect of Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja in lipid-loaded mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 26, 383–385. 10.1248/bpb.26.383 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie, M, Y., Li, L., Nie, S, P., Wang, X, R., Lee, F, S, C. Determination of speciation of elements related to blood sugar in bioactive extracts from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves by FIA-ICP-MS. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 223 (2), 202-209. 10.1007/s00217-005-0173-0, (2006).

- 4.Li, X, C., Fu, X, X., Shang, X, L., Yang, W, X., Fang, S, Z.,. Natural population structure and genetic differentiation for heterodicogamous plant: Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja (Juglandaceae). Tree Genetics & Genomes, 13, 80. 10.1007/s11295-017-1157-5, (2017).

- 5.Teixeira, A., Eiras-Dias, J., Castellarin, S. D. & Geros, H. Phenolics of grapevine under challenging environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (9), 18711–18739. 10.3390/ijms140918711 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun, C., Zhou, Y., Fang, S. & Shang, X. Ecological gradient analysis and environmental interpretation of Cyclocarya paliurus Communities. Forests 12, 146 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng, B. et al. Variation and stability of growth and leaf flavonoid content in Cyclocarya paliurus across environments. Indus. Crops Prod. 76, 386–393. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.07.011 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou, M. M., Chen, P., Shang, X. L., Yang, W. X. & Fang, S. Z. Genotype Environment Interactions for Tree Growth and Leaf Phytochemical Content of Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal.) Iljinskaja. Forests 10.3390/f12060735 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao, Y. N. et al. Genotypic variation in tree growth and selected flavonoids in leaves of Cyclocarya paliurus. Southern Forests 10.2989/20702620.2016.1274862 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao, Y, N., Fang, S, Z., Yin, Z, Q., Fu, X, X., Shang, X, L., Yang, W, X., Yang, H, M. Chemical fingerprint and multicomponent quantitative analysis for the quality evaluation of Cyclocarya paliurus leaves by HPLC-Q-TQF-MS. Molecules. 22 (11), 1927-1942. 10.3390/molecules22111927, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Y Liu Y Cao N., Fang, S, Z., Wang, T, L., Yin, Z, Q., Shang, X, L., Yang, W, X., Fu, X, X. Antidiabetic effect of Cyclocarya paliurus leaves depends on the contents of antihyperglycemic flavonoids and antihyperlipidemic flavonoids Molecules. 10.3390/molecules23051042, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Molecular Ecol 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang, S. Z., Yang, W. X., Chu, X. L., Shang, X. & L., She, C, Q., Fu, X, X.,. Provenance and temporal variations in selected flavonoids in leaves of Cyclocarya paliurus. Food Chem. 124, 1382–1386. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.07.095 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, Y. et al. Effect of light regime and provenance on leaf characteristics, growth and flavonoid accumulation in Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja coppices. Bot. Stud. 57 (1), 28. 10.1186/s40529-016-0145-7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adom, K. K., Sorrells, M. E. & Liu, R. H. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activity of wheat varieties. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 51 (26), 7825–7834. 10.1021/jf030404l (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.André, C. M. et al. Gene expression changes related to the production of phenolic compounds in potato tubers grown under drought stress. Phytochemistry 70, 1107–1116 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt, S. et al. Genotypic and climatic influences on the concentration and composition of flavonoids in kale (Brassica oleracea var sabellica). Food Chem. 119 (4), 1293–1299 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia, C., Pandey, A., Gaddam, S. R., Hoecker, U. & Trivedi, P. K. Low Temperature-Enhanced Flavonol Synthesis Requires Light-Associated Regulatory Components in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant And Cell Physiology 10.1093/pcp/pcy132 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, P. M., Ma, F. W. & Cheng, L. L. Primary and secondary metabolism in the sun-exposed peel and the shaded peel of apple fruit. Physiologia Plantarum 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01692.x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berardi, A. E., Fields, P. D., Abbate, J. L. & Taylor, D. R. Elevational divergence and clinal variation in floral color and leaf chemistry in Silene vulgaris. Am. J. Bot. 103, 1508–1523. 10.3732/ajb.1600106 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampaio, B. L., Edrada-Ebel, R. & Da Costa, F. B. Effect of the environment on the secondary metabolic profile of Tithonia diversifolia: a model for environmental metabolomics of plants. Sci. Rep. 10.1038/srep29265 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, N. et al. MYB12 and MYB22 play essential roles in proanthocyanidin and flavonol synthesis in red-fleshed apple (Malus sieversii f. niedzwetzkyana). Plant J. 10.1111/tpj.13487 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie, L. F. et al. Unravelling the consecutive glycosylation and methylation of flavonols in peach in response to UV-B irradiation. Plant Cell Environ. 10.1111/pce.14323 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang, D. et al. Exogenous melatonin application delays senescence of kiwifruit leaves by regulating the antioxidant capacity and biosynthesis of flavonoids. Front. Plant Sci. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00426 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zenoni, S. et al. Transcriptional Responses to Pre-flowering Leaf Defoliation in Grapevine Berry from Different Growing Sites, Years, and Genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 8 (630), 1–21. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00630 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun, C. W., Fang, S. Z. & Shang, X. L. Transcriptomic and Non-Targeted Metabolomic Analyses Reveal Changes in Metabolic Networks during Leaf Coloration in Cyclocarya paliurus (Batalin) Iljinsk. Forests 10.3390/f14101948 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due follow-up studies are ongoing but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. paliurus collecting statement, We have permission to collect C. paliurus resources. And the permissions were obtained from local forestry institutions. The collecting resources were deposited in the silviculture laboratory in Nanjing Forestry University and identified by Yanni Cao and Xiaochun Li.