Abstract

Stevia rebaudiana is associated with the production of calorie-free steviol glycosides (SGs) sweetener, receiving worldwide interest as a sugar substitute for people with metabolic disorders. The aim of this investigation is to show the promising role of endophytic bacterial strains isolated from Stevia rebaudiana Egy1 leaves as a biofertilizer integrated with Azospirillum brasilense ATCC 29,145 and gibberellic acid (GA3) to improve another variety of stevia (S. rebaudiana Shou-2) growth, bioactive compound production, expression of SGs involved genes, and stevioside content. Endophytic bacteria isolated from S. rebaudiana Egy1 leaves were molecularly identified and assessed in vitro for plant growth promoting (PGP) traits. Isolated strains Bacillus licheniformis SrAM2, Bacillus paralicheniformis SrAM3 and Bacillus paramycoides SrAM4 with accession numbers MT066091, MW042693 and MT066092, respectively, induced notable variations in the majority of PGP traits production. B. licheniformis SrAM2 revealed the most phytohormones and hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production, while B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 was the most in exopolysaccharides (EPS) and ammonia production 290.96 ± 10.08 mg/l and 88.92 ± 2.96 mg/ml, respectively. Treated plants significantly increased in performance, and the dual treatment T7 (B. paramycoides SrAM4 + A. brasilense) exhibited the highest improvement in shoot and root length by 200% and 146.7%, respectively. On the other hand, T11 (Bacillus cereus SrAM1 + B. licheniformis SrAM2 + B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 + B. paramycoides SrAM4 + A. brasilense + GA3) showed the most elevation in number of leaves, total soluble sugars (TSS), and up-regulation in the expression of the four genes ent-KO, UGT85C2, UGT74G1 and UGT76G1 at 2.7, 3.3, 3.4 and 3.7, respectively. In High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis, stevioside content showed a progressive increase in all tested samples but the maximum was exhibited by dual and co-inoculations at 264.37% and 289.05%, respectively. It has been concluded that the PGP endophytes associated with S. rebaudiana leaves improved growth and SGs production, implying the usability of these strains as prospective tools to improve important crop production individually or in consortium.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-73470-0.

Keywords: Stevia rebaudiana, Gibberellic acid, Plant growth promoting bacteria, Endophytic bacteria, Azospirillum brasilense, UDP glycosyltransferases (UGTs).

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Agriculture is the most critical resource for the worldwide market and environmental systems face several challenges. The global consumption of chemical fertilizers has increased and played a vital role in crop yields1. However, plants grown in this way do not have enough time to grow and mature properly, and therefore do not acquire excellent plant attributes2. Moreover, highly harmful toxic compounds will build up in the human body and soil3. Thus, developing eco-friendly and sustainable solutions that could reduce the need for chemical fertilizers is a demand. Beneficial microbes could be a significant source of bioactive natural compounds4.

Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) have three main functions: producing essential metabolites for plants, enabling the uptake of nutrients from the soil, and reducing disease in plants5,6. The majority of investigations have focused on bacteria found in the plant rhizosphere, and one of them is plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR)7. However, a subgroup of bacteria from the rhizosphere can enter and colonize plants as endophytes, creating a mutualistic relationship with the plants without harmful effect8. Endophytes can promote plant growth directly through phosphate solubilization, nitrogen fixation9, and phytohormone production such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and gibberellic acid (GA)10, and indirectly through exopolysaccharide (EPS) production11and inhibiting phytopathogens by hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and hydrolyzing enzymes12.

Endophytic communities in leaves vary depending on the host plant species or genotype, plant growth stage, and plant morphology13. Several studies have reported that the genera Azospirillum, Bacillus, Azotobacter, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacter have the potential to promote plant growth14. Furthermore, Bacillus and Azospirillum are the most well-studied genera of PGPB, improving plant growth and yield15. Co-inoculation of legumes with Azospirillum brasilense and Bradyrhizobium has been shown to boost grain yield in maize, wheat, soybean and common bean16,17. It has been demonstrated that inoculating Salicornia bigelovii with Bacillus licheniformis and other PGPB can work together to improve plant growth and nutrient uptake18. A. brasilense Sp7 and Bacillus spharecus UPMB10 improved root growth in dessert-type banana19. Similar to this, fennel seeds struggle to establish themselves due to their poor vegetative growth and poor seedling emergence, particularly in drought-stressed environments20. By boosting antioxidant activity and defense mechanisms, seed inoculation treatments with Pseudomonas fluorescens bacteria and Trichoderma harzianum fungus improved the early growth of fennel seedlings under drought-stress conditions21. In Stevia, research has been conducted to assess the impact of mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on the organism’s ability to grow, accumulate secondary metabolites, and express genes involved in biosynthesis. According to studies by Rahi, et al.22 inoculating plants with distinct PGPR enhanced their growth, photosynthetic indices, and stevioside and rebaudioside A accumulation. On the other hand, inoculation of Stevia with plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus stimulate plant height, stevioside, minerals, and pigments content23. Oviedo-Pereira, et al.24 reported that the stimulating endophytes Enterobacter hormaechei H2A3 and H5A2 increased the SG content, stimulated the density of trichomes in the leaves, and encouraged the accumulation of specialized metabolites in trichomes; nevertheless they did not promote plant growth.

Egypt’s economy is challenged by a shortfall of 0.843 million tons between sugar supply and demand25. Accordingly, alternative biotechnology approaches can be employed in the large-scale cultivation of perennial shrub Stevia rebaudiana, which has been utilized as a non-caloric natural sweetener for those with metabolic disorders26. Its leaves contain steviol glycosides (SGs), a class of tetracyclic diterpenoid compounds estimated to be 300 times sweeter than sucrose27.

Stevioside and rebaudioside A are the two main sweetening components, while rebaudioside C, D, E, and F, dulcoside A, and steviolbioside are minor28. SGs are produced in the chloroplast via the non-mevalonate pathway of methyl-erythritol phosphate (MEP)27. The structures of both SGs and GA are tetracyclic diterpenes and share the same biosynthetic pathway derived from the synthesis of ent-kaurenoic acid29. Several glycosylation reactions catalyzed by UDP glycosyltransferases (UGTs) make up the biosynthetic pathway for different SGs30.

GA3 is one of the most essential and bioactive gibberellin-like proteins31. Exogenous GA3 treatment in S. rebaudianahas increased stem elongation and flowering32. On the other side, several studies reported that GA3 as an elicitor which stimulates secondary metabolite production in plants such as antioxidants and pigments as well as a defense mechanism33.

Sequels to these different microbe bio-formulations with A. brasilense and GA3 were designed to test and compare their effects on S. rebaudiana Shou-2 plant growth performance, bioactive compounds such as stevioside production, and up-regulation of the genes responsible for the SGs pathway (Table 1).

Table 1.

Design of treatments.

| Code | Treatments | Code | Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | Control | T6 | A.brasilense + B.paralicheniformis SrAM3 |

| T1 | Bacillus licheniformis SrAM2 | T7 | A.brasilense + B.paramycoids SrAM4 |

| T2 | Bacillus paralicheniformis SrAM3 | T8 | A.brasilense + GA3 |

| T3 | Bacillus paramycoides SrAM4 | T9 | B. cereus SrAM1 + B. licheniformis SrAM2 + B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 + B. paramycoides SrAM4 |

| T4 | Gibberellic acid (GA3) | T10 | B. cereus SrAM1 + B. licheniformis SrAM2 + B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 + B. paramycoides SrAM4 + A. brasilense |

| T5 | Azospirillum brasilense + B. licheniformis SrAM2 | T11 | B. cereus SrAM1 + B. licheniformis SrAM2 + B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 + B. paramycoides SrAM4 + A. brasilense + GA3 |

Results

Isolation, selection, and identification of endophytic bacteria

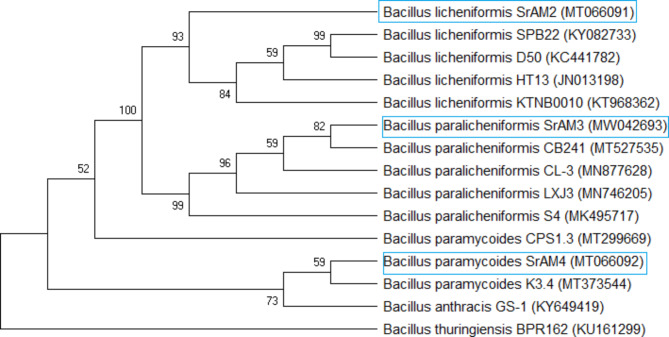

Three strains from S. rebaudiana Egy1 leaves were isolated, purified, colonies described, and given SrAM2, SrAM3, and SrAM4 codes. In SrAM2, the colonies were buff powdery flat punctiform with irregular and filamentous margins. SrAM3 exhibited white powdery raised large colonies with irregular and lobate margins, while SrAM4 revealed creamy convex moderate colonies with round and entire round margins. All of the bacteria were gram-positive and formed spores. Isolates were molecularly identified as Bacillus licheniformis SrAM2 (100%), Bacillus paralicheniformis SrAM3 (100%), and Bacillus paramycoides SrAM4 (99.79%) with accession numbers MT066091, MW042693, and MT066092, respectively, based on sequence identity (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of isolated strains relative to other type strains. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses.

Plant growth-promoting characteristics of endophytic bacteria

It can be observed that all strains produce a high amount of GA3 compared with IAA. Still, the elevated IAA and GA3 syntheses were conducted by B. licheniformis SrAM2 at 52.97 and 186.23 µg/mL, respectively (Table 2). The potential of bacteria to fix nitrogen is indicated by their growth on a nitrogen-free medium, and all strains were able to do so. Positive P solubilization, on the other hand, revealed clear zones around the colonies of B. licheniformis SrAM2 and B. paralicheniformis SrAM3, but no clear zones surrounding B. paramycoides SrAM4 colonies. All strains produced EPS and ammonia, but B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 displayed the maximum production. HCN production was observed in B. licheniformis SrAM2 864.86 mg/L, whereas B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 and B. paramycoides SrAM4 were not detected, as represented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Determination of phenotypic characterization of in vitro plant growth-promoting criteria of isolated strains.

| Plant growth-promoting traits (PGP) | B. licheniformis SrAM2 | B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 | B. paramycoides SrAM4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Characterization | |||

| Indole acetic acid (IAA) (mg/mL) | 52.97 ± 1.03a | 17.46 ± 4.77b | 31.51 ± 6.14b |

| Gibberellic acid (GA) (mg/mL) | 186.23 ± 6.45a | 167.15± 3.86b | 133.92 ± 3.09c |

| Exopolysacchrides (EPS) (mg/L) | 169.07 ± 3.91b | 290.96 ± 10.08a | 131.36 ± 3.79c |

| Ammonia production (mg/mL) | 62.32 ± 2.15b | 88.92 ± 2.96a | 49.47 ± 4.94c |

| Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) (mg/L) | 864.86 ± 29.96a | - | - |

| Qualitative Characterization | |||

| Nitrogen fixation | + | + | + |

| Phosphate Solubilization | + | + | - |

| Amylase | - | + | + |

| Cellulase | + | - | + |

| Protease | - | + | + |

| Lipase | - | + | + |

The results were recorded as mean of triplicates ± (SE). Different superscript letters refer to significant differences (P ≤ 0.05).

Extracellular hydrolytic enzymes activity

Amylase, cellulase, and protease activity were detected as clear zone surrounding a colony, whereas a white precipitation around colonies indicated lipase activity. As illustrated in Table 2, B. paramycoides SrAM4 could produce all hydrolytic enzymes, but B. paralicheniformis SrMA3 had the ability to produce of all enzymes except cellulase, whereas B. licheniformis SrAM2 produced cellulase only.

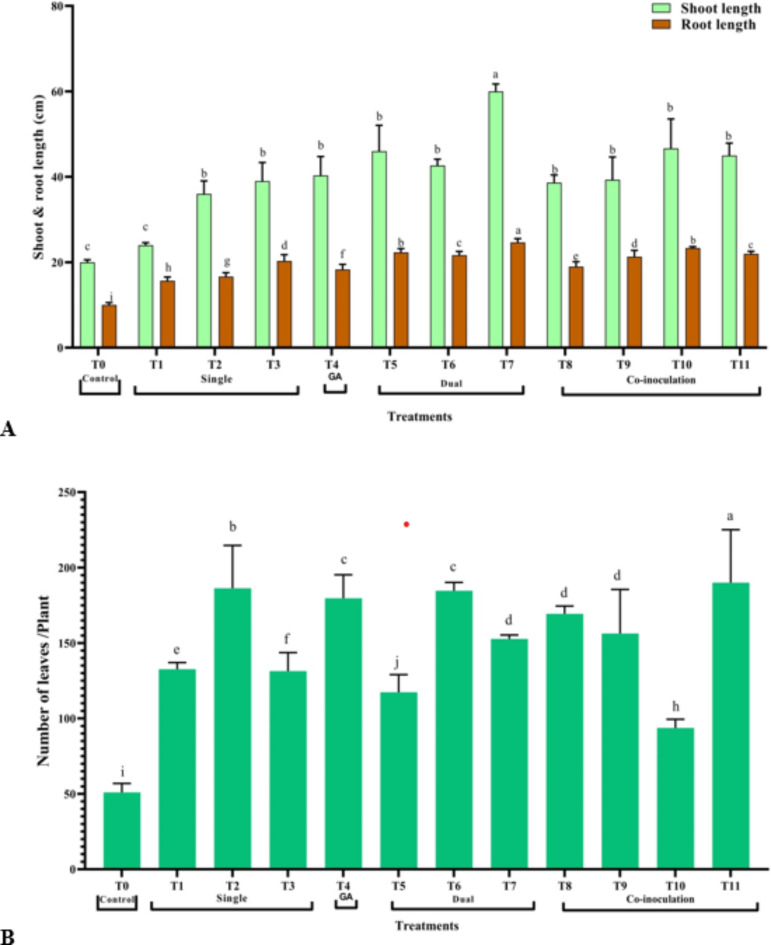

Effect of treatments on growth parameters

Results showed that plants treated with dual inoculations showed higher growth parameters than those with individual and co-culture treatments. The maximum increase in plant growth was observed in the dual treatment T7, resulting in an increase of 200% and 146.7% in shoot and root length, respectively (Fig. 2A). Number of leaves showed the maximum in co-culture treatment T11, followed by T2, with an increase of 272.55% and 264.71%, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of treatments on morphological parameters of S. rebaudiana Shou-2 plantlets (A) Shoot and root length and (B) Number of leaves. Bar indicated ± SE. Different lower-case letters indicated significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 [Duncan’s test].

Effect of treatments on pigment content

The highest chl a and chl b, carotenoids, and total pigment content were observed in plants treated with individual treatments as illustrated in Table 3, but the maximum chl a and chl b and total pigment content were achieved by T4 at 2.43, 2.88, and 5.97 mg/g f.wt., respectively. Carotenoids content of 0.79 mg/g f.wt. was the maximum in T3.

Table 3.

Effect of treatments on chl a, chl b, carotenoids, and total pigments of S. Rebaudiana Shou-2.

| Treatments | Chlorophyll a (mg/g) | Chlorophyll b (mg/g) | Carotenoids (mg/g) | Total pigment (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 0.44 ± 0.02k | 0.63 ± 0.04f | 0.35 ± 0.07g | 1.43 ± 0.05k |

| T1 | 1.70 ± 0.02b | 1.07 ± 0.03c | 0.75 ± 0.00b | 3.51 ± 0.04b |

| T2 | 1.31 ± 0.06e | 0.87 ± 0.16d | 0.52 ± 0.06e | 2.70 ± 0.18e |

| T3 | 1.59 ± 0.01c | 0.61 ± 0.01f | 0.79 ± 0.00a | 2.99 ± 0.01c |

| T4 | 2.43 ± 0.10a | 2.88 ± 0.22a | 0.65 ± 0.03c | 5.97 ± 0.29a |

| T5 | 1.41 ± 0.03d | 1.17 ± 0.02b | 0.51 ± 0.03e | 3.08 ± 0.03c |

| T6 | 0.98 ± 0.07i | 0.60 ± 0.25f | 0.48 ± 0.17f | 2.06 ± 0.18i |

| T7 | 1.41 ± 0.05d | 0.87 ± 0.17d | 0.61 ± 0.11d | 2.89 ± 0.02d |

| T8 | 0.86 ± 0.01j | 0.42 ± 0.07g | 0.44 ± 0.03f | 1.73 ± 0.03j |

| T9 | 1.02 ± 0.07h | 0.74 ± 0.01e | 0.49 ± 0.02e | 2.25 ± 0.05h |

| T10 | 1.17 ± 0.20g | 0.87 ± 0.16d | 0.49 ± 0.13e | 2.54 ± 0.16f |

| T11 | 1.22 ± 0.02f | 0.59 ± 0.07f | 0.61 ± 0.06d | 2.42 ± 0.03g |

The results were recorded as mean of triplicates ± standard error (SE). Different superscript letters refer to significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) (Duncan’s multiple range test).

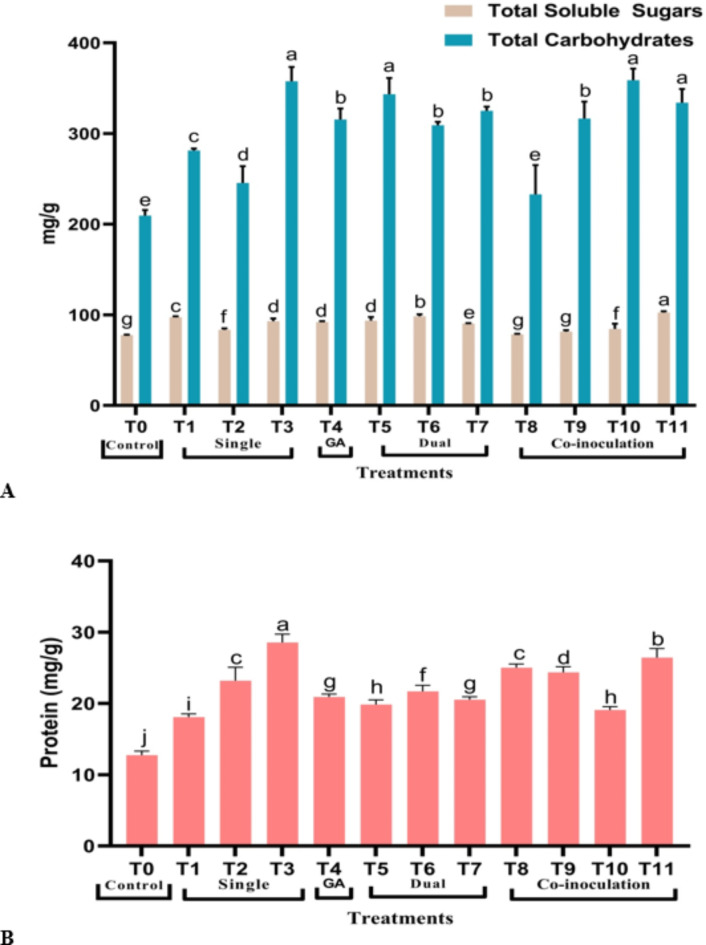

Effect of treatments on total soluble sugars, carbohydrates, and protein

Compared to the control, all treatments showed elevations in TSS, total carbohydrates (Fig. 3A), and protein (Fig. 3B). The treatment T11 showed the maximum content of total soluble sugars at 102.56 mg/g d.wt. On the contrary, total carbohydrates represented the highest by T10 (358.96) mg/g d.wt, whereas T3 outlined the maximum protein content at 28.55 mg/g f.wt.

Fig. 3.

Variation in biochemical parameters in S. rebaudiana Shou-2 (A) TSS, total carbohydrates contents in dry leaves and (B) Total protein content in fresh leaves. Bar indicated ± SE. Different lower-case letters indicated significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 [Duncan’s test].

Effect of treatment on non-enzymatic antioxidants

In Table 4, T5 revealed highest TPC content at 55.34 mg (GAEs)/g. TFC was the highest by T4 at 9.63 mg (QE)/g. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was significantly reduced by T11 (55.24%). Additionally, maximum TAC was induced by T2 at 34.55 mg (AA)/g.

Table 4.

Effect of treatments on non-enzymatic antioxidants activity of S. Rebaudiana Shou-2.

| Treatments | Total phenolics (mg (GAEs)/g) | Total flavonoids (mg (QE)/g) | Total antioxidant capacity (mg (A.A)/g) | DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 21.72 ± 0.72j | 4.53 ± 0.05h | 8.05 ± 0.22h | 78.12 ± 1.31a |

| T1 | 30.13 ± 0.84h | 5.96 ± 0.14g | 17.39 ± 0.49f | 77.17 ± 1.78b |

| T2 | 34.03 ± 0.95f | 7.07 ± 0.16f | 34.55 ± 3.34a | 71.55 ± 1.18c |

| T3 | 30.30 ± 0.92h | 5.97 ± 0.10g | 26.84 ± 4.51b | 71.83 ± 2.13c |

| T4 | 39.47 ± 1.23b | 9.63 ± 0.10a | 21.35 ± 1.04d | 66.66 ± 1.97e |

| T5 | 55.34 ± 1.60a | 6.65 ± 0.23f | 19.05 ± 0.26e | 61.64 ± 2.20f |

| T6 | 37.04 ± 1.23d | 8.79 ± 0.34d | 17.74 ± 0.85e | 67.27 ± 2.40e |

| T7 | 34.68 ± 1.08e | 9.35 ± 0.12b | 16.76 ± 1.48f | 70.80 ± 2.10d |

| T8 | 30.00 ± 1.28h | 5.83 ± 0.05g | 13.39 ± 0.64g | 61.38 ± 2.19f |

| T9 | 33.01 ± 1.03g | 7.61 ± 0.15e | 23.88 ± 2.24c | 66.21 ± 1.10e |

| T10 | 29.19 ± 0.90i | 5.92 ± 0.13g | 20.96 ± 0.97d | 69.57 ± 2.48d |

| T11 | 37.87 ± 1.27c | 8.87 ± 0.24c | 21.35 ± 0.63d | 55.24 ± 1.97g |

The results were recorded as mean of triplicates ± standard error (SE). Different superscript letters refer to significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) (Duncan’s multiple range test).

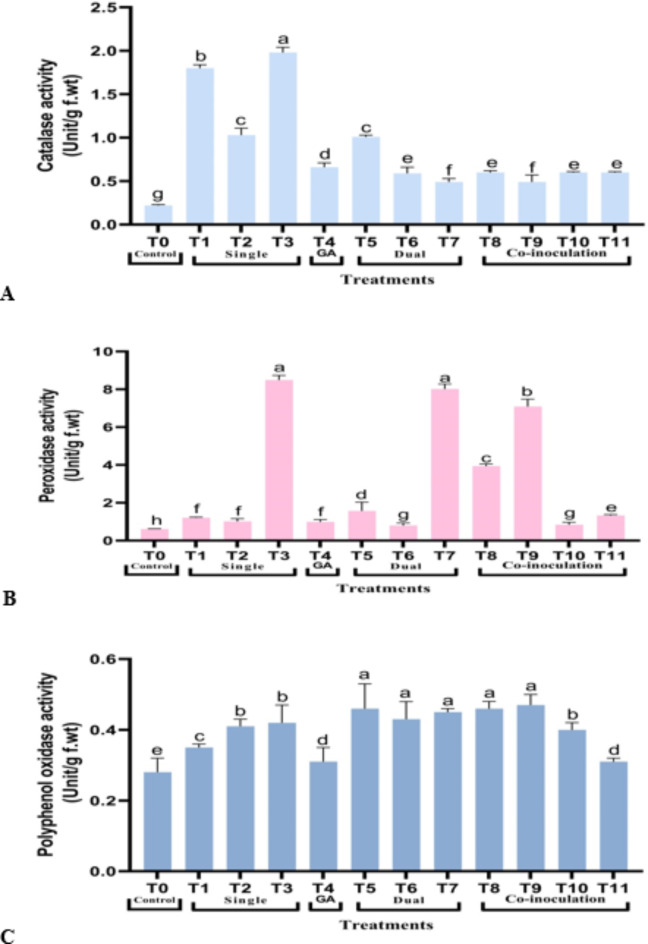

Effect of treatments on enzymatic antioxidants

As shown in Fig. 4, all enzymatic antioxidant activities were increased compared to control. For example, treatment T3 showed the highest CAT and POD activities, 1.98 and 8.49 Unit/g f.wt., respectively. Conversely, PPO activity showed the highest at T9 (0.47 Unit/g f.wt.).

Fig. 4.

Changes in the activities of (A) Catalase, (B) Peroxidase, and (C) Polyphenol oxidase of S. rebaudiana Shou-2 leaves expressed as Unit/g f.wt. Bar indicated ± SE. Different lower-case letters indicated significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 [Duncan’s test].

Effects of treatments on the transcription of SGs-related genes

The evaluation of transcription patterns in the regulatory SGs-related genes under the effect of treatments is shown in Fig. 5; the results illustrated that all applications up-regulated the transcription of the SGs genes relative to control, varying with different treatments. Various treatments significantly impacted ent-KO, UGT85C2, UGT74G1, and UGT76G1 transcription. Still, the treatment T11 had the highest relative gene expression at 2.7, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.7, respectively.

Fig. 5.

The genes expression levels of S. rebaudiana Shou-2 plantlets (A) ent-KO, (B) UGT85C, (C) UGT74G1 and (D) UGT76G1. Bar indicated ± SE. Different lower-case letters indicated significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 [Duncan’s test].

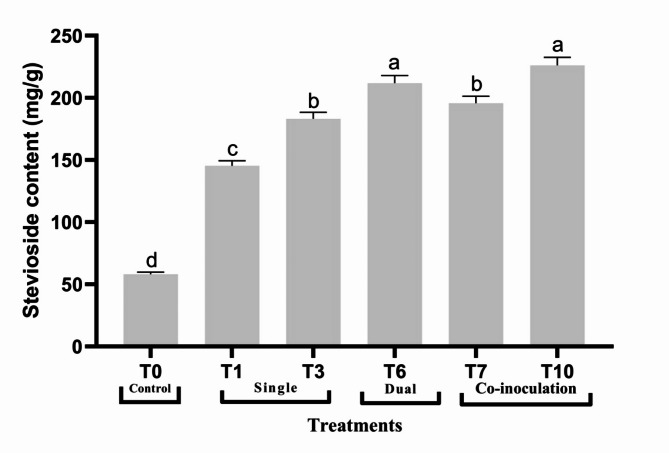

Effect of treatments on stevioside content by HPLC analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 6, stevioside analysis of some selective samples was performed by HPLC using different concentrations of the standard solution illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. The maximum stevioside content at 226.09 mg/g, as shown in the chromatogram was represented by T10, with an increase of 3.9 times more than the minimum concentration (control) at 58.11 mg/g. (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 6.

Effect of some treatments on stevioside content, selected according to the elevation in some biochemical attributes. Bar indicated ± SE. Different lower-case letters indicated significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 [Duncan’s test].

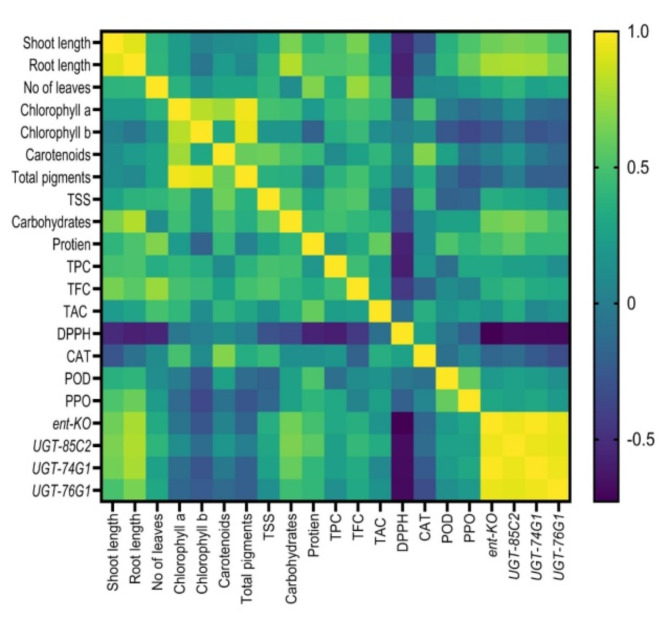

Intercorrelation between different treatments

Pearson’s test was used to assess the possible correlation between morphological and biochemical parameters and gene transcription levels (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 2). Shoot length (SHL) had a significantly positive correlation with root length (RL), carbohydrates content, TFC, and the expression of ent-KO, UGT85C2, and UGT74G1 genes (0.923, 0.655, 0.641, 0.620, 0.659, and 0.631, respectively). In contrast, SHL was negatively correlated with DPPH and CAT by − 0.525 and − 0.275, respectively. Similarly, RL was significantly positively correlated with carbohydrates content, PPO, and the four transcribed genes 0.801, 0.608, 0.779, 0.791, 0.774, and 0.644, respectively. Conversely, RL negatively correlated with chlb, DPPH, and CAT at − 0.056, − 0.575, and − 0.090, respectively. Correspondingly, the number of leaves was significantly positively correlated with protein and TFC (0.674 and 0.737, respectively), whereas it was negatively correlated with DPPH (− 0.547). In the same manner, total pigments were positive with chla, chlb, and carotenoids (0.964, 0.938, and 0.599, respectively). In addition, carotenoids were significantly positive correlated with TSS and CAT (0.617 and 0.677, respectively). Carbohydrates significantly positively correlated with the expression of three relative genes (ent-KO, UGT85C2, and UGT74G1). Moreover, the expression of relative four genes was significantly positively correlated with each other (0.959, 0.989, 0.943, 0.950, 0.928, and 0.957). Conversely, DPPH was negatively significantly correlated with TPC, ent-KO, UGT85C2, UGT74G1, and UGT76G1 (− 0.588, − 0.728, − 0.678, − 0.681, and − 0.689), respectively.

Fig. 7.

Heatmap of the simple linear Pearson correlation coefficient between growth parameters, biochemical attributes, and the expression of genes involved in steviol glycosides production. The colours reflect significant correlation values in each treatment, yellow for high intensities and blue for low intensities (follow scale at right).

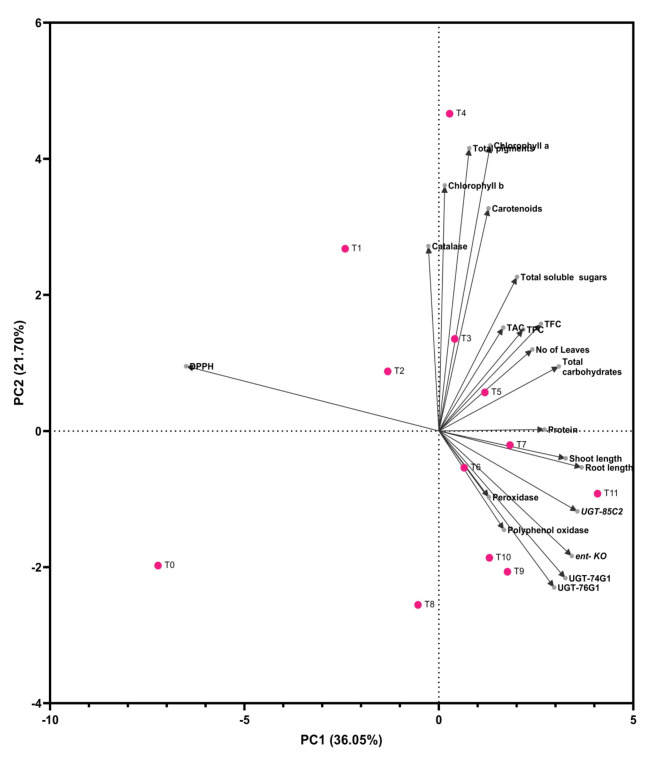

Multivariate principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all examined parameters, accounting for 57.75% of the total variance in the data set, with the first principal component (PC1) accounting for 36.05% and the second accounting for 21.70% (PC2) as constructed in Fig. 8. PC1 was associated with parameters except for DPPH and CAT and associated with PC2, and treatments were divided into three groups through the vector and cosine. PCA results show that group 1 treated T0, T1, T2, and T8 samples with frequent vectors of DPPH and CAT. Group 2 treated T3, T4 and T5 samples with frequent vectors (chla, chlb, carotenoids, total pigments, number of leaves, carbohydrates TSS, TPC, TFC, TAC and protein). Group 3 treated T6, T7, T9, T10 and T11 with the frequent vectors SHL, RL, POD, PPO, ent-KO, UGT85C2, UGT74G1, and UGT76G1. The length of the vector showed the discrimination power of the parameter. In this study, vector of SHL, RL, number of leaves, carbohydrates, protein, CAT, POD, PPO, TPC, TFC, and TAC were of shorter length, which showed poor discrimination power for these traits. On the contrary, the longer vector showed strengthened discrimination of traits such as DPPH, chla, chlb, carotenoids, total pigment, SHL, RL, ent-KO, UGT85C2, UGT74G1, and UGT76G1.

Fig. 8.

Perceptual mapping (Biplot) analysis showing results of morphological, physiological parameters and expression of steviols glycosides gene. Pink dots enclosed each treatment separated by parameters. TAC, Total antioxidants capacity; TPC, Total phenolics content; TFC, Total flavonoids content.

Discussion

Beneficial microorganisms can improve plant nutrient uptake, modify soil health, boost plant defense, and ensure agricultural sustainability34. In the same manner, increasing plant length, the number of leaves, and/or SGs content can overcome the scarcity of S. rebaudiana production. The primary sources of SGs are leaves, which may include unique endophytic bacteria and provide a better environment for bacteria than other plants used as bio-inoculants35. This investigation characterized three endophytic bacterial strains isolated from surface sterilized leaves of S. rebaudiana Egy1. The molecular identification illustrated that these isolates belong to the phylum Firmicutes, which have excellent activity of PGP. Thus far, only one metagenomic study of the microbiome in leaves has confirmed our findings. It revealed that Proteobacteria dominated the endophytic bacteria in S. rebaudiana leaves, followed by Firmicutes and Bacillus species in the core microbiome of leaves13.

IAA increases number, length, and volume of adventitious roots, allowing them to transport nutrients36. Conversely, GA plays a role in stem elongation, seed dormancy reduction, and flowering31. B. licheniformis SrAM2 produced the most IAA, as B. licheniformis M16 and B. licheniformis GL174 were isolated from a corn rhizosphere and Vitis vinifera internal tissues37,38. Moreover, B. paralicheniformis SrAM3 produced the least quantity of IAA, similar to B. paralicheniformis TRQ65 from wheat39, whereas B. paramycoides SrAM4 represents higher levels than typically seen in other bacteria, B. paramycoides CSL3, isolated from Camellia spp40. Similarly, B. licheniformis SrAM2 had the maximum GA3 production and was higher than B. licheniformis DS3 isolated from banana rhizosphere41. However, B. paralicheniformis promoted plant growth and screened for PGP traits, but there was no evidence about GA3 production42. B. paramycoides SrAM4 production of GA3 was the highest between the similar strains isolated from the root of cultivated rice (Oryza sativa) and wild rice (Oryza rufipogon)43.

Nitrogen and phosphate are essential elements for plant growth and development44. Despite the availability of nitrogen in the atmosphere as well as phosphate in soil, it is nonetheless unavailable to plants45. In this study, the three strains can fix nitrogen and solubilize phosphate, except B. paramycoides SrAM4, which was not able to solubilize phosphate. Borah, et al.40 did not support our findings; they found that B. paramycoides strains could solubilize phosphate. On the other hand, the presence of the nif gene in Bacillus species46. Our results confirmed the fact that most bacteria were able to fix nitrogen and were able to produce ammonia, which provided nitrogen to the host plant, supported plant biomass production, and contributed to plant defense47. Furthermore, all isolates produced ammonia, which was consistent with the study proving that Bacillus species have the higher ammonia production than other species isolated from chickpea plants48. Furthermore, ammonia might be produced by B. licheniformis S26 and B. paramycoides R5 that were isolated from sugarcane as well as B. paralicheniformis AB330 that was isolated from the tea rhizosphere11. Pseudomonas florescences which has promote plant growth criteria increase Arachis hypogaea L. growth as described by Nithyapriya, et al.49.

On the other hand, B. licheniformis SrAM2 was the only strain able to produce HCN, and the result supported B. licheniformis QA1 isolated from Chenopodium quinoa and B. licheniformis PC-41 isolated from Zea mays50,51. EPS production is essential for protecting plants from stress and root from desiccation52. Bacillus appears to have formed biofilms in response to specific environmental changes, including salt stress, nutrients, and oxygen availability53. Several studies have shown that Bacillusspecies can produce much more EPS than other species54. Additionally, B. licheniformis SrAM3 produced higher EPS than B. licheniformis B3-15 55.

Since hydrolytic enzymes contribute to organic matter decomposition, protect plants against phytopathogens, and aid bacteria in penetrating plant roots56. Hazarika, et al.8 investigated the ability of Bacillus sp. to produce amylase and protease enzymes but the inability of producing cellulase. B. licheniformis SrAM2 and B. licheniformis H7 were matched in their ability to produce cellulase only57. In this investigation, all enzymes except cellulase were produced by B. paralicheniformis SrAM3, consistent with tea rhizobacteria B. paralicheniformis AB330 11. B. paramycoides SrAM4 produced all of the enzymes found in B. paramycoides Vb6, isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Vicia faba58.

As a result, a better understanding of the relationships between plant-associated bacterial communities is vital in managing crops more effectively. In the present study morphological and physiological traits and expression of SGs genes were lower in non-inoculated plants than inoculated. Our findings confirmed that endophytic bacteria could increase S. rebaudiana biomass which was supported by Finkel, et al.59. Ye, et al.60 study on S. rebaudiana inoculated with Bacillus endophytic bacteria isolated from Polygonum hydropiper showed a significant increase in the number of leaves, SHL, and RL. The increase in plant performance found in dual inoculations and co-inoculations contained A. brasilense in corroboration with the effects of (A) brasilense and Bradyrhizobium spp. co-inoculation on soybean61. The number of leaves showed that the highest treatment contains (B) paralicheniformis SrAM3 which had the most PGP traits. Similarly, the isolate B. subtilis NA-108 increased the number of leaves on strawberries62.

In contrast, chlorophyll showed the maximum in plants treated with GA3,which was in agreement with other studies of Oat cultivars63. Similarly, Datta, et al.64 reported that GA3treatment boosted chlorophyll and photosynthetic rate in soybean. Modi, et al.65 supported our findings as the highest chlorophyll content was observed in 60 mM of GA application. In a comparable manner it was discovered that the foliar application of GA3improved plant length, lateral shoot length, lateral shoot number, fruit number, root length, root wet weight, and stem wet weight, total chlorophyll, pigment content, and reducing sugar66. Furthermore, chlorophyll content was enhanced and showed maximum after foliar and irrigation with purple phototrophic bacteria (PPB)67. It can be due to the ability of bacteria for nitrogen fixation and solubilize phosphate, which is the main element in chlorophyll and photosynthesis68. After bacterial inoculation, carotenoids showed improvement in rice as well as alfalfa plants after the application of exogenous hormones compared with control69.

As a result, GA3 and bacterial treatment played a critical role in boosting carbohydrate and TSS content of plants that is wholly supported with effects of Phaseolus vulgaris after treatments with IAA, BA, and endophytic bacteria70. TSS were significantly increased after treatments stimulation which was consistent with the content in S. rebaudiana treated with PPB67. These stimulations may correlate with pigments content as photosynthesis increases, stimulating plant growth and increasing bioactive compounds26. Total protein increased in all treated plants mainly co-inoculated, supported with chickpea plant co-inoculated with B. subtilis and Mesorhizobium ciceri IC53 71. Pandey, et al.72 found that dual inoculation of B. pumilus and B. subtilis significantly boosted different proximate constituents and essential amino acids in Amaranth grains. The increased protein and carbohydrate levels of Amaranthus hypochondriacus could be explained that the Bacillus isolates facilitated resource acquisition73.

A diversity of important microbial genera have been linked to increased secondary metabolite synthesis in medicinal and aromatic plants74. All enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants significantly increased in S. rebaudiana Shou-2 compared with control; a positive effect of PGPB on TPCs in rice has also been described by Chamam, et al.75. Furthermore, our finding agreed with the results of TPCs, TFCs, and DPPH in S. rebaudiana due to the combined effect of Piriformospora indica and Azotobacter chroococcum76. In comparison to untreated plants, Ocimum basilicum plants treated with microorganisms had considerably greater TPC and TFC77. Additionally, the increase of antioxidants may be interpreted by two reasons stimulate the plant’s inducible defense mechanisms in the same way pathogenic microorganisms do as a result of hydrolytic enzymes until the plant adapts to bacterial colonization78. Secondly, PGPB may act as priming elicitors which induce these bioactive compounds that formed via the shikimate pathway in higher plants and microorganisms79.

We supposed that up-regulation in the antioxidant was associated with the activation of the shikimate pathway may be followed by up-regulation in the MEP pathway, which supported by our results that transcription of SGs pathways genes up-regulated all relative gene expression in treated samples. The common factor between all treatments was GA3availability, whether from bacteria secretions or exogenous80. The up-regulation of the gene results entirely supported the gene expression results of the same genes in S. rebaudiana treated with GA3foliar spray81,82. The study of Kumar, et al.83 supported our results, which showed up-regulation of the gene’s transcription after GA3 treatments. Interestingly, the relationship between SGs content and the transcription of some critical genes involved in the SGs production pathway was affected. Our results supported the fact that there was a correlation between ent-KO transcription and the accumulation of SGs, which was also confirmed by Kumar, et al.83 and our previous study84. As the highest stevioside content among the selected samples was compatible with relative gene expression results which supported the study of Ahmad, et al.33. It might be described as the uptake of GA3 foliar spray producing an excess in GA3 in plant cells, which caused the GA3biosynthesis pathway to be diverted to SGs biosynthesis65. In addition, the increase in stevioside content was supposed to be correlated with carbohydrates and especially TSS content as the glucose units enrichment in SGs chemical structure.

The findings demonstrated a synergistic relationship between the number of leaves, gene expression, and SG production in response to co-inoculations with multiple strains. On the other hand, dual inoculation outperformed single inoculation in terms of plant growth and performance.

Materials and methods

Plant samples and isolation of endophytic bacteria

S. rebaudiana Egy1 plantlets obtained from the Sugars Crops Research Institute (SCRI), Agriculture Research Center (ARC), Giza, Egypt. Healthy S. rebaudiana Egy1 leaves were randomly collected from different pots, washed under running water, and then surface sterilized according to Zhou, et al.85. Leaves were cut into small pieces and plated on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar at 28 °C for 24 h; morphologically distinct colonies were selected, described, and bacteria examined under an oil immersion lens86,87.

Identification of isolates by 16s rRNA

Genomic DNA of bacteria was extracted using SolGent purification kits (SolGent, Daejeon, Korea). After 15 min of incubation at 95 °C, PCR amplified 16s rRNA gene using forward primer (27f) 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′′ and 1492 reverse primer R 5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′′88. PCR conditions were 30 cycles at 95 °C for 20 s, 50 °C for 40 s, 72 °C for 1 min and 30 s, and 72 °C for 5 min. The product was purified using SolGent cleanup kit, checked with 1% agarose gel, and then sequenced on AB1 3730XL DNA Analyzer (ABI, CA, USA). The sequences were identified using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) and compared with National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The phylogenetic relationships were constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replications by Mega X software89.

Screening for plant growth-promoting traits of endophytic bacterial strains

Quantitative evaluation of IAA and ga3 production

Isolated strains inoculated in LB broth medium supplemented with 1-tryptophan (1.02 g/L) and incubated in orbital shaking incubator (JSR-100 C/Korea) at 28 °C for 3 days at 150 rpm for IAA determination as Bric, et al.90 described. The culture centrifuged for 3 min at 7000 rpm, and the supernatant was used to determine IAA concentrations according to Naveed, et al.91.

GA3was assessed according to Holbrook, et al.92 using LB broth media inoculated with endophytic bacteria and incubated for 7 days at 150 rpm in an orbital shaking incubator, centrifuged at 5000 rpm and then 2 mL zinc acetate reagent was added to 15 mL supernatant. After 2 min, 2 mL 10.6% potassium ferrocyanide was added and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 254 nm (Jenway spectrophotometer model 7315) after adding 5 mL 30% HCl to 5 mL supernatant followed by incubation for 75 min at 25 ºC. GA3 concentrations were calculated using GA3as a standard in amounts ranging from (100–1000 µg/mL)93.

Potentiality for nitrogen fixation and phosphate solubilization

N2fixation was determined by streaking strains on Jensen’s nitrogen-free medium for 4–7 days at 28ºC94, although phosphate capability was detected using Pikovskaya agar medium95.

Quantitative determination of ammonia, EPS and HCN production

Ammonia was determined according to Cappuccino and Sherman96 by inoculating water peptone broth medium with strains, incubated for 4 days in an orbital shaking incubator at 150 rpm at 28 ºC. Ammonia detected using Nessler’s reagent, the development of color ranging from yellow to brown indicated ammonia production and measured at 450 nm.

EPS were determined using phenol sulfuric method and concentrations were calculated by a glucose solution standard97. Finally, HCN was assessed by inoculating King’s B agar medium supplemented with 4.4 g/l glycine with bacteria. Filter paper saturated with 0.5% picric acid and 2% sodium carbonate solution was deposited on top of the plate, sealed with parafilm and incubated for 48 h at 28 ºC98. A change in color of indicator paper from deep yellow to reddish-brown confirmed production of HCN and the concentration quantitatively assayed according to Reetha, et al.99.

Extracellular hydrolytic enzymes activities

Hydrolytic enzymes were detected after inoculation of bacteria on agar media containing indicative substrate and incubated at 28 °C for 2–5 days. Amylase activity was detected using iodine solution after streaking of bacteria on a starch agar medium100. The cellulase activity was detected according to Khianngam, et al.101 using 0.2% aqueous Congo red reagent. Protease activity was observed through a clear zone around colonies inoculated on skimmed milk agar medium described by Cui, et al.102. On the other hand, lipase was detected after inoculation on a Tween agar medium100.

Pot experiment using S. rebaudiana Shou-2 plantlets

The experiments were conducted at the garden of Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Dakahlia, Egypt, under 12/12 h light/dark natural light conditions at 28 ± 2 ºC. The plantlets S. rebaudiana Shou-2 obtained from SCRI aged 45 days, which were transferred to plastic pots filled with 3.5 kg of soil composed of peat moss, clay, and sand 1:1:1.

A preliminary experiment was conducted to evaluate the synergistic and antagonistic interactions between the strains involved in the microbe bio-formulations, which include of A. brasilense ATCC 29,145 obtained from Microbial Resource Center (Cairo Mircen). Bacillus cereus SrAM1 MW042692 was previously isolated from S. rebaudiana84 as well as the three isolated endophytic bacteria (SrAM2, SrAM3, and SrAM4) of this study. GA3was prepared in concentration of 60 mM according to Modi, et al.65 with modification.

The experiment had 12 treatments that were described in Table 1, applied by foliar spray and irrigation of bacterial suspension every 2 days on 45 days old plantlets for 30 days, while GA3 was only foliar sprayed twice with the distance of 2 weeks. The harvesting time was after being treated for 10 days at 85 days old of plant.

Bacterial suspension was prepared by inoculating 108 CFU/mL in 450 mL LB broth, incubated at 28 °C ± 2 °C for 24 h at 150 rpm, centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min, then pellet was resuspended in distilled water and adjusted to OD600. Treatments were applied via irrigation of 100 mL bacterial suspension around the root and foliar spray starting with 10 mL at the early stage of the plant and increased until reaching to 25 mL at later stages according to Wu, et al.67 with some modifications.

Assessment of plant growth measurements and pigments

Growth parameters such as number of leaves and shoot and root length. Additionally, chlorophyll a (chl a) and chlorophyll b (chl b) were determined by homogenization of (0.1 g) fresh leaves in 10 mL 80% acetone, the absorbance of homogenate was measured at 470, 645 and 663 nm according to Arnon103, whereas carotenoids were according to Lichtenthaler and Wellburn104.

Determination of total soluble sugars (TSS), carbohydrate, and protein content

TSS were determined using the method of Yemm and Willis105. Total carbohydrates content was determined according to Hedge, et al.106. Finally, protein content in fresh leaves was estimated according to Bradford107.

Measurements of total phenolics (TPC), total flavonoids (TFC), total antioxidants capacity (TAC), and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical assay (DPPH)

Using methanolic extract, non-enzymatic antioxidants were assessed. The Folin-Ciocalteu method determined TPC of the extracts was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry weight108. An aluminum chloride colorimetric test was used to measure TFC and was represented as mg quercetin (QE) equivalents per gram of dry weight109. TAC was estimated by phosphomolybdenum assay and expressed as mg ascorbic acid per gram of dry weight110. Finally, DPPH was used to assess antioxidant activity by measuring the radical scavenging percentage of the extracts using the following equation111.

|

Where A0 = control absorbance and A1 = extracts absorbance.

Determination of enzymatic antioxidant activity

For enzymes assays, the extract was prepared by macerating 0.2 g of fresh leaves in a cold 3 mL (0.05 M) phosphate buffer (pH = 7), the homogenate was filtrated, and the filtrate was made up to 5 mL. Using the method provided by Aebi112, the catalase (CAT) activity was determined. In contrast, the polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD) activity assay were determined using the method reported by Kar and Mishra113.

Real-time-qPCR analysis of transcript levels of specific genes associated with the biosynthesis of SGs

Total RNA was extracted from frozen leaves using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden,Germany); the first-strand cDNA was generated with the Qiagen Reverse Transcription kit. The QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit technique was used to perform RT-qPCR; SYBR green binds to double-stranded DNA, and the amplification products quantify the development of the target transcript compared with the housekeeping gene transcript. RT-qPCR was performed in a 96-well plate in a total volume of 10 µL, with 1.5 µL of cDNA (4 ng/µL), 0.1 µL of each primer (10 pm/µL), and 5 µL SYBER Green qPCR master mix (Qiagen, Hilden,Germany). PCR amplification conditions were 95 °C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 62 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a melting cycle from 65 °C to 95 °C to validate amplicon specificity. Amplification was performed using Hajihashemi and Geuns114 gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). In this investigation, the housekeeping gene β-Actin was used, and the relative expression levels were measured using a 2−ΔΔCtassay115.

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of stevioside

Twenty mg of dried leaves was extracted three times by boiling for 15 min in 3 mL deionized water. The extracts were centrifuged, and the supernatant was decanted, cooled, and made up to 15 mL with deionized water. According to Ceunen, et al.116, the quantity of stevioside was determined. In the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Water 2960 Alliance HPLC system), 100 µL of the extract was injected in C18 columns Xterra: 4.6 × 100 mm, 5 μm; UV detection was 210 nm. The solvent flow rate was 1 mL/min, and the acetonitrile: 1.0 mM phosphoric acid gradient.

Statistical analysis

All experiments used a randomized complete block design with three biological and technical experimental replications. Statistical calculations were carried out with SPSS (version 16; SPSS, New York, NY, USA). The results were presented as mean values with standard errors (±). The mean values were subjected to one-way analysis of variance ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range tests117. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered as significant using superscripted letters. Perceptual mapping (Biplot) analysis, heatmap of simple linear Pearson correlation coefficient between parameters and histograms were plotted using Sigma Plot 14 software and GraphPad Prism9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Conclusions

S. rebaudiana endophytic bacteria demonstrated potency for plant growth promotion in single, dual, or mixed bio-formulations. As a result, PGPB tends to play an important role in the development of plant vigour and health by delivering vital nutrients, bioactive substances, and gene expression in S. rebaudiana Shou-2. When compared to control, the treatments increased all parameters, but co-inoculations were the most effective on stevioside content, which was supported by an elevation in the expression of SGs related genes. Furthermore, an increase in carbohydrate and TSS contents was thought to be associated with the elevated in SGs, particularly the stevioside content. The activation of the shikimate pathway is associated with increases in antioxidant content, which is thought to be an indication of MEP pathway activation. From the foregoing, several characteristics produced by endophytic bacteria and exogenously applied strains work together to improve plant performance and the development of promising bioactive compounds.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mansoura and Tanta Universities for supports.

Abbreviations

- CAT

Catalase

- Chla

Chlorophyll a

- Chlb

Chlorophyll b

- DPPH

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- EPS

Exopolysaccharides

- GA

Gibberellic acid

- GAE

Gallic acid

- HCN

Hydrogen cyanide

- HPLC

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

- IAA

Indole-3-acetic acid

- LB

Luria–Bertani

- MEP

C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate

- PGP

Plant growth promoting

- PGPB

Plant growth-promoting bacteria

- PGPR

Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria

- POD

Peroxidase

- PPO

Polyphenol oxidase

- QE

Quercetin

- RL

Root length

- SE

Standard error

- SGs

Steviol glycosides

- SHL

Shoot length

- TAC

Total antioxidants capacity

- TFC

Total flavonoid content

- TPC

Total phenolic content

- TSS

Total soluble sugars

- UGTs

UDP glycosyltransferases

Author contributions

M.A.E., Y.M.H. and A.M.A. carried out the molecular genetic experiments. A.M.A. and Y.M.H. carried out the physiological experimental work. A.M.A. and A.E. performed the microbiological experimental work. Y.M.H. and A.M.A. carried out all statistical analysis. All authors wrote the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are presented in the paper and/or the supplementary materials.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

All the authors declare that plant collection and use were in accordance with all the relevant guidelines.

Plant material permission

All authors state appropriate permissions and/or licenses for collection of plant or seed specimens used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van Dijk, M., Morley, T., Rau, M. L. & Saghai, Y. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050. Nat. Food. 2, 494–501 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar, R., Kumar, R. & Prakash, O. (February, 2019).

- 3.Zhang, J. et al. Harnessing the plant microbiome to promote the growth of agricultural crops. Microbiol. Res.245, 126690 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty, M. et al. Inhibitory effects of linear lipopeptides from a marine Bacillus subtilis on the wheat blast fungus Magnaporthe Oryzae Triticum. Front. Microbiol.11, 665 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayat, R., Ali, S., Amara, U., Khalid, R. & Ahmed, I. Soil beneficial bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion: a review. Ann. Microbiol.60, 579–598 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parray, J. A., Egamberdieva, D., Abd-Allah, E. F. & Sayyed, R. Vol. 7, 1251054. (Frontiers Media SA, 2023).

- 7.Kumar, S., Sindhu, S. S., Kumar, R. & Biofertilizers An ecofriendly technology for nutrient recycling and environmental sustainability. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci.3, 100094 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazarika, S. N., Saikia, K., Borah, A. & Thakur, D. Prospecting endophytic Bacteria endowed with Plant Growth promoting potential isolated from Camellia sinensis. Front. Microbiol.12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Mohanty, P., Singh, P. K., Chakraborty, D., Mishra, S. & Pattnaik, R. Insight into the role of PGPR in sustainable agriculture and environment. Front. Sustainable Food Syst.5 (2021).

- 10.Hardoim, P. R. et al. The hidden world within plants: ecological and evolutionary considerations for defining functioning of microbial endophytes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.79, 293–320 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhattacharyya, C. et al. Evaluation of plant growth promotion properties and induction of antioxidative defense mechanism by tea rhizobacteria of Darjeeling, India. Sci. Rep.10, 1–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanna, K. et al. Antioxidants in Plant-Microbe Interaction 339–379 (Springer, 2021).

- 13.Yu, X., Yang, J., Wang, E., Li, B. & Yuan, H. Effects of growth stage and fulvic acid on the diversity and dynamics of endophytic bacterial community in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni leaves. Front. Microbiol.6, 867 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma, M., Mishra, J. & Arora, N. K. Environmental Biotechnology: For Sustainable Future 129–173 (Springer, 2019).

- 15.Cassán, F. & Diaz-Zorita, M. Azospirillum sp. in current agriculfrom: From the laboratory to the field. Soil Biol. Biochem.103, 117–130 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukami, J., Nogueira, M. A., Araujo, R. S. & Hungria, M. Accessing inoculation methods of maize and wheat with Azospirillum brasilense. Amb Express. 6, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hungria, M., Nogueira, M. A. & Araujo, R. S. Soybean seed co-inoculation with Bradyrhizobium spp. and Azospirillum brasilense: A new biotechnological tool to improve yield and sustainability. Embrapa Soja-Artigo em periódico Indexado (ALICE) 6 (2015).

- 18.Bashan, Y., Moreno, M. & Troyo, E. Growth promotion of the seawater-irrigated oilseed halophyte Salicornia bigelovii inoculated with mangrove rhizosphere bacteria and halotolerant Azospirillum spp. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 32, 265–272 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mia, M. Bacilli in Agrobiotechnology 151–168 (Springer, 2022).

- 20.Yaldiz, G. & Camlica, M. Variation in the fruit phytochemical and mineral composition, and phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the fruit extracts of different fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) genotypes. Ind. Crops Prod.142, 111852 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosseini-Moghaddam, M. et al. Seed coating with minerals and plant growth-promoting bacteria enhances drought tolerance in fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol.58, 103202 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahi, P. et al. Stimulatory effect of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria on plant growth, stevioside and rebaudioside-A contents of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. Appl. Soil. Ecol.46, 222–229 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vafadar, F., Amooaghaie, R. & Otroshy, M. Effects of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on plant growth, stevioside, NPK, and chlorophyll content of Stevia rebaudiana. J. Plant Interact.9, 128–136 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oviedo-Pereira, D. G. et al. Enhanced specialized metabolite, trichome density, and biosynthetic gene expression in Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) Bertoni plants inoculated with endophytic bacteria enterobacter hormaechei. PeerJ. 10, e13675 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashem, M. M., AbdelHamid, R. I., AbuelMaaty, S., Elassal, S. S. & ElDoliefy, A. E. A. Differential UGT76G1 and start codon-based characterization of six stevia germlines in Egypt. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol.33, 101981 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain, P., Kachhwaha, S. & Kothari, S. Improved micropropagation protocol and enhancement in biomass and chlorophyll content in Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.) Bertoni by using high copper levels in the culture medium. Sci. Hort.119, 315–319 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav, S. K. & Guleria, P. Steviol glycosides from Stevia: biosynthesis pathway review and their application in foods and medicine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.52, 988–998 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czinkóczky, R. & Németh, Á. Enrichment of the rebaudioside A concentration in Stevia rebaudiana extract with cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13. Eng. Life Sci.22 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Humphrey, T. V., Richman, A. S., Menassa, R. & Brandle, J. E. Spatial organisation of four enzymes from Stevia rebaudiana that are involved in steviol glycoside synthesis. Plant Mol. Biol.61, 47–62 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoneda, Y., Shimizu, H., Nakashima, H., Miyasaka, J. & Ohdoi, K. Effect of treatment with gibberellin, gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitor, and auxin on steviol glycoside content in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. Sugar Tech.20, 482–491 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baliyan, N. et al. Optimization of Gibberellic Acid production in Endophytic Bacillus cereus using response surface methodology and its Use as Plant Growth Regulator in Chickpea. J. Plant Growth Regul.41, 1–11 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karimi, M. et al. Opposing effects of external gibberellin and Daminozide on Stevia growth and metabolites. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.175, 780–791 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad, A. et al. Effect of gibberellic acid on production of biomass, polyphenolics and steviol glycosides in adventitious root cultures of Stevia rebaudiana (Bert). Plants. 9, 420 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain, P. & Pundir, R. K. Potential role of endophytes in sustainable agriculture-recent developments and future prospects. Endophytes Biol. Biotechnol.15, 145–169 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelsattar, A. M., Elsayed, A., El-Esawi, M. A. & Heikal, Y. M. Enhancing Stevia rebaudiana growth and yield through exploring beneficial plant-microbe interactions and their impact on the underlying mechanisms and crop sustainability. Plant Physiol. Biochem.198, 107673 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazumdar, D., Saha, S. P. & Ghosh, S. Isolation, screening and application of a potent PGPR for enhancing growth of Chickpea as affected by nitrogen level. Int. J. Vegetable Sci.26, 333–350 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldan, E. et al. Beneficial bacteria isolated from grapevine inner tissues shape Arabidopsis thaliana roots. PLoS ONE10, e0140252 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Márquez, R., Blanco, E. L. & Aranguren, Y. Bacillus strain selection with plant growth-promoting mechanisms as potential elicitors of systemic resistance to gray mold in pepper plants. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.27, 1913–1922 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valenzuela-Aragon, B., Parra-Cota, F. I., Santoyo, G., Arellano-Wattenbarger, G. L. & de los Santos-Villalobos, S. Plant-assisted selection: a promising alternative for in vivo identification of wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. Durum) growth promoting bacteria. Plant. Soil.435, 367–384 (2019).

- 40.Borah, A., Das, R., Mazumdar, R. & Thakur, D. Culturable endophytic bacteria of Camellia species endowed with plant growth promoting characteristics. J. Appl. Microbiol.127, 825–844 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silpa, D., Rao, P. B., Kumar, G. K. & Raghu, R. Studies on gibberellic acid production by Bacillus Licheniformis DS3 isolated from banana field soils. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol.4, 1106–1112 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahu, P. K. et al. Inter-genera colonization of Ocimum tenuiflorum endophytes in Tomato and their complementary effects on Na+/K + balance, oxidative stress regulation, and Root Architecture under elevated soil salinity. Front. Microbiol.12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Borah, M., Das, S., Bora, S. S., Boro, R. C. & Barooah, M. Comparative assessment of multi-trait plant growth-promoting endophytes associated with cultivated and wild Oryza germplasm of Assam, India. Arch. Microbiol.203, 2007–2028 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rilling, J. I., Acuña, J. J., Sadowsky, M. J. & Jorquera, M. A. Putative nitrogen-fixing bacteria associated with the rhizosphere and root endosphere of wheat plants grown in an andisol from southern Chile. Front. Microbiol.9, 2710 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, Z. et al. Isolation and characterization of a phosphorus-solubilizing bacterium from rhizosphere soils and its colonization of Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis). Front. Microbiol.8, 1270 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, H. B. et al. Genetic diversity of nitrogen-fixing and plant growth promoting Pseudomonas species isolated from sugarcane rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol.8, 1268 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marques, A. P., Pires, C., Moreira, H., Rangel, A. O. & Castro, P. M. Assessment of the plant growth promotion abilities of six bacterial isolates using Zea mays as indicator plant. Soil Biol. Biochem.42, 1229–1235 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brígido, C. et al. Diversity and functionality of culturable endophytic bacterial communities in chickpea plants. Plants8, 42 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nithyapriya, S. et al. Purification and characterization of desferrioxamine B of Pseudomonas fluorescens and its application to Improve Oil Content, Nutrient Uptake, and Plant Growth in Peanuts. Microb. Ecol.87, 1–13 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahdi, I., Fahsi, N., Hafidi, M., Allaoui, A. & Biskri, L. Plant growth enhancement using rhizospheric halotolerant phosphate solubilizing bacterium Bacillus licheniformis QA1 and Enterobacter asburiae QF11 isolated from Chenopodium quinoa willd. Microorganisms. 8, 948 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marag, P. S. & Suman, A. Growth stage and tissue specific colonization of endophytic bacteria having plant growth promoting traits in hybrid and composite maize (Zea mays L). Microbiol. Res.214, 101–113 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morcillo, R. J. & Manzanera, M. The effects of plant-associated bacterial exopolysaccharides on plant abiotic stress tolerance. Metabolites. 11, 337 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiwari, S., Prasad, V., Chauhan, P. S. & Lata, C. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens confers tolerance to various abiotic stresses and modulates plant response to phytohormones through osmoprotection and gene expression regulation in rice. Front. Plant Sci.8, 1510 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, K. et al. Structural characterization and bioactivity of released exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus plantarum 70810. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.67, 71–78 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maugeri, T. L. et al. A halophilic thermotolerant Bacillus isolated from a marine hot spring able to produce a new exopolysaccharide. Biotechnol. Lett.24, 515–519 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Deeb, B., Bazaid, S., Gherbawy, Y. & Elhariry, H. Characterization of endophytic bacteria associated with rose plant (Rosa Damascena trigintipeta) during flowering stage and their plant growth promoting traits. J. Plant Interact.7, 248–253 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohammad, B. T., Daghistani, A., Jaouani, H. I., Abdel-Latif, A. & Kennes, C. S. Isolation and characterization of thermophilic bacteria from Jordanian Hot Springs: Bacillus licheniformis and Thermomonas hydrothermalis isolates as potential producers of thermostable enzymes. Int. J. Microbiol.2017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.El-Sersawy, M. M., Hassan, S. E. D., El-Ghamry, A. A., El-Gwad, A., Fouda, A. & A. M. & Implication of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria of Bacillus spp. as biocontrol agents against wilt disease caused by Fusarium Oxysporum Schlecht. In Vicia faba L. Biomol. Concepts. 12, 197–214 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finkel, O. M., Castrillo, G., Paredes, S. H., González, I. S. & Dangl, J. L. Understanding and exploiting plant beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol.38, 155–163 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ye, D. et al. Characteristics of endophytic bacteria from Polygonum hydropiper and their use in enhancing P-phytoextraction. Plant. Soil.448, 647–663 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Felici, C. et al. Single and co-inoculation of Bacillus subtilis and Azospirillum brasilense on Lycopersicon esculentum: effects on plant growth and rhizosphere microbial community. Appl. Soil. Ecol.40, 260–270 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Pereira, M., Magalhães, G. V., Lorenzetii, K. T., Souza, E. R., Schwan, R. & T. P. & F. A multiphasic approach for the identification of endophytic bacterial in strawberry fruit and their potential for plant growth promotion. Microb. Ecol.63, 405–417 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chauhan, A., Rajput, N., Kumar, A., Verma, J. & Chaudhry, A. Interactive effects of gibberellic acid and salt stress on growth parameters and chlorophyll content in oat cultivars. J. Environ. Biol.39, 639–646 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Datta, J., Nag, S., Banerjee, A. & Mondai, N. Impact of salt stress on five varieties of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars under laboratory condition. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag.13 (2009).

- 65.Modi, A. R., Shukla, Y. M., Litoriya, N. S., Patel, N. J. & Narayan, S. Effect of gibberellic acid foliar spray on growth parameters and stevioside content of ex vitro grown plants of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. Med. Plants-Int. J. Phytomed. Relat. Ind.3, 157–160 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salehi-Sardoei, A. et al. Hybrid method of Gibberellic Acid Applications: A Sustainable and Reliable Way for improving Jerusalem Cherry. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol., 103253 (2024).

- 67.Wu, J., Wang, Y. & Lin, X. Purple phototrophic bacterium enhances stevioside yield by Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni via foliar spray and rhizosphere irrigation. PloS One. 8, e67644 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thuynsma, R., Kleinert, A., Kossmann, J., Valentine, A. J. & Hills, P. N. The effects of limiting phosphate on photosynthesis and growth of Lotus japonicus. South. Afr. J. Bot.104, 244–248 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar, A., Singh, S., Mukherjee, A., Rastogi, R. P. & Verma, J. P. Salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting Bacillus pumilus strain JPVS11 to enhance plant growth attributes of rice and improve soil health under salinity stress. Microbiol. Res.242, 126616 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ismail, M. A. et al. Comparative study between Exogenously Applied Plant Growth Hormones versus metabolites of Microbial endophytes as Plant Growth-promoting for Phaseolus vulgaris L. Cells10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Egamberdieva, D., Wirth, S. J., Shurigin, V. V., Hashem, A. & Abd-Allah, E. F. Endophytic bacteria improve plant growth, symbiotic performance of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and induce suppression of root rot caused by Fusarium solani under salt stress. Front. Microbiol.8, 1887 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pandey, C., Bajpai, V. K., Negi, Y. K., Rather, I. A. & Maheshwari, D. Effect of plant growth promoting Bacillus spp. on nutritional properties of Amaranthus hypochondriacus grains. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.25, 1066–1071 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Emmanuel, O. C. & Babalola, O. O. Productivity and quality of horticultural crops through co-inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth promoting bacteria. Microbiol. Res.239, 126569 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gupta, R., Anand, G. & Pandey, R. Bioactive Natural Products in Drug Discovery 687–711 (Springer, 2020).

- 75.Chamam, A. et al. Plant secondary metabolite profiling evidences strain-dependent effect in the Azospirillum–Oryza sativa association. Phytochemistry87, 65–77 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kilam, D., Saifi, M., Abdin, M., Agnihotri, A. & Varma, A. Combined effects of Piriformospora indica and Azotobacter chroococcum enhance plant growth, antioxidant potential and steviol glycoside content in Stevia rebaudiana. Symbiosis66, 149–156 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ordookhani, K., Sharafzadeh, S. & Zare, M. Influence of PGPR on growth, essential oil and nutrients uptake of sweet basil. Adv. Environ. Biology. 5, 672–677 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Loon, L. New Perspectives and Approaches in Plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria Research 243–254 (Springer, 2007).

- 79.Rahman, M. et al. Plant probiotic bacteria bacillus and Paraburkholderia improve growth, yield and content of antioxidants in strawberry fruit. Sci. Rep.8, 1–11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brandle, J. & Telmer, P. Steviol glycoside biosynthesis. Phytochemistry68, 1855–1863 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hajihashemi, S., Geuns, J. M. & Ehsanpour, A. A. Gene transcription of steviol glycoside biosynthesis in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni under polyethylene glycol, paclobutrazol and gibberellic acid treatments in vitro. Acta Physiol. Plant.35, 2009–2014 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hajihashemi, S. & Geuns, J. M. Steviol glycosides correlation to genes transcription revealed in gibberellin and paclobutrazol-treated Stevia rebaudiana. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol.26, 387–394 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumar, H., Kaul, K., Bajpai-Gupta, S., Kaul, V. K. & Kumar, S. A comprehensive analysis of fifteen genes of steviol glycosides biosynthesis pathway in Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni). Gene492, 276–284 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elsayed, A., Abdelsattar, A. M., Heikal, Y. M. & El-Esawi, M. A. Synergistic effects of Azospirillum brasilense and Bacillus cereus on plant growth, biochemical attributes and molecular genetic regulation of steviol glycosides biosynthetic genes in Stevia rebaudiana. Plant Physiol. Biochem.189, 24–34 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou, J. et al. Isolation, characterization and inoculation of cd tolerant rice endophytes and their impacts on rice under cd contaminated environment. Environ. Pollut.260, 113990 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oktari, A., Supriatin, Y., Kamal, M. & Syafrullah, H. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 012066 (IOP Publishing).

- 87.Claus, D. A standardized Gram staining procedure (1992). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Xu, J. X. et al. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus subtilis strain 1-L-29, an endophytic bacteria from Camellia oleifera with antimicrobial activity and efficient plant-root colonization. PLoS ONE15, e0232096 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: a justification. Evolution39, 783–791 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bric, J. M., Bostock, R. M. & Silverstone, S. E. Rapid in situ assay for indoleacetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.57, 535–538 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Naveed, M. et al. L-Tryptophan-dependent biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) improves plant growth and colonization of maize by Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN. Ann. Microbiol.65, 1381–1389 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Holbrook, A. A., Edge, W. & Bailey, F. Vol. 28 Ch. 18, 159–167 (ACS Publications, 1961).

- 93.Sharma, S., Sharma, A. & Kaur, M. Extraction and evaluation of gibberellic acid from Pseudomonas Spp. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochem.7, 2790–2795 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ahmad, F., Ahmad, I. & Khan, M. Screening of free-living rhizospheric bacteria for their multiple plant growth promoting activities. Microbiol. Res.163, 173–181 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pikovskaya, R. Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with vital activity of some microbial species. Mikrobiologiya. 17, 362–370 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cappuccino, J. & Sherman, N. Biochemical activities of microorganisms. Microbiology, A Laboratory Manual. The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Co. California, USA, 188–247 (1992).

- 97.Wang, X. et al. Optimization, partial characterization and antioxidant activity of an exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum KX041. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.103, 1173–1184 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bakker, A. W. & Schippers, B. Microbial cyanide production in the rhizosphere in relation to potato yield reduction and Pseudomonas spp-mediated plant growth-stimulation. Soil Biol. Biochem.19, 451–457 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reetha, A. K., Pavani, S. L. & Mohan, S. Hydrogen cyanide production ability by bacterial antagonist and their antibiotics inhibition potential on Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi.) Goid. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci.3, 172–178 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hankin, L. & Anagnostakis, S. The use of solid media for detection of enzyme production by fungi. Mycologia. 67, 597–607 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khianngam, S., Pootaeng-on, Y., Techakriengkrai, T. & Tanasupawat, S. Screening and identification of cellulase producing bacteria isolated from oil palm meal. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci.4, 90 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cui, H., Wang, L. & Yu, Y. Production and characterization of alkaline protease from a high yielding and moderately halophilic strain of SD11 marine bacteria. J. Chem. (2015).

- 103.Arnon, D. Copper enzyme in isolated chloroplast and chlorophyll expressed in terms of mg per gram. Plant Physiol.24, 1–15 (1949). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Wellburn, A. R. Vol. 11 (Portland Press Ltd., 1983).

- 105.Yemm, E. & Willis, A. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J.57, 508–514 (1954). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hedge, J., Hofreiter, B. & Whistler, R. Carbohydrate chemistry, 17 (Academic Press, 1962).

- 107.Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ikram, E. H. K. et al. Antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content of Malaysian underutilized fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal.22, 388–393 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 109.Baba, S. A. & Malik, S. A. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid content, antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of a root extract of Arisaema Jacquemontii Blume. J. Taibah Univ. Sci.9, 449–454 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 110.Prieto, P., Pineda, M. & Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem.269, 337–341 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chu, Y. H., Chang, C. L. & Hsu, H. F. Flavonoid content of several vegetables and their antioxidant activity. J. Sci. Food. Agric.80, 561–566 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 112.Aebi, H. Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 105, 121–126 (Elsevier, 1984). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Kar, M. & Mishra, D. Catalase, peroxidase, and polyphenoloxidase activities during rice leaf senescence. Plant Physiol.57, 315–319 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hajihashemi, S. & Geuns, J. M. Gene transcription and steviol glycoside accumulation in Stevia rebaudiana under polyethylene glycol-induced drought stress in greenhouse cultivation. FEBS Open. Bio. 6, 937–944 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Ceunen, S., Werbrouck, S. & Geuns, J. M. Stimulation of steviol glycoside accumulation in Stevia rebaudiana by red LED light. J. Plant Physiol.169, 749–752 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Duncan, D. B. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics11, 1–42 (1955). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are presented in the paper and/or the supplementary materials.