Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) neutralization occurs when specific antibodies, mainly those directed against the envelope glycoproteins, inhibit infection, most frequently by preventing the entry of the virus into target cells. However, the precise mechanisms of neutralization remain unclear. Previous studies, mostly with cell lines, have produced conflicting results involving either the inhibition of virus attachment or interference with postbinding events. In this study, we investigated the mechanisms of neutralization by immune sera and compared the inhibition of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) infection by HIV-1 primary isolates (PI) with the inhibition of T-cell line infection by T-cell line-adapted (TCLA) strains. We followed the kinetics of neutralization to determine at which step of the viral cycle the antibodies act. We found that neutralization of the TCLA strain HIV-1MN/MT-4 required an interaction between antibodies and cell-free virions before the addition of MT-4 cells, whereas PI were neutralized even after adsorption onto PBMC. In addition, the dose-dependent inhibition of HIV-1MN binding to MT-4 cells was strongly correlated with serum-induced neutralization. In contrast, neutralizing sera did not reduce the adhesion of PI to PBMC. Postbinding inhibition was also detected for HIV-1MN produced by and infecting PBMC, demonstrating that the mechanism of neutralization depends on the target cell used in the assay. Finally, we considered whether the different mechanisms of neutralization may reflect the recognition of qualitatively different epitopes on the surface of PI and HIV-1MN or whether they reflect differences in virus attachment to PBMC and MT-4 cells.

Humoral immunity is efficient against many infectious pathogens, including viruses, and contributes to successful vaccination. Protection can be obtained through neutralization, defined as a loss of infectivity after the binding of antibodies to specific epitopes on the surface of the virus particle. This interaction may impair specific steps of the viral cycle, such as attachment of the virus to target cells, entry, or even later stages. It results in the inhibition of infection.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is taken up into cells via a complex process including specific protein-protein interactions and conformational changes (8). The env-encoded proteins, gp120 and gp41, are key determinants in this process. The surface glycoprotein, gp120, initiates the viral cycle by binding specifically to the high-affinity cellular receptor CD4. Following this initial contact, gp120 undergoes conformational changes (44, 45) that create the high-affinity configuration of a conserved binding site for a coreceptor (50, 56), most commonly CCR5 for macrophagetropic isolates or CXCR4 for T-cell line-adapted (TCLA) strains (14). Interaction with both receptor and coreceptor leads to the adsorption of viral particles onto cells, probably assisted by cell adhesion molecules incorporated into virions during budding (48). Upon adsorption, additional conformational changes expose the amino-terminal peptide of gp41, resulting in fusion of the viral membrane with the target cell membrane. Most neutralizing antibodies are directed against gp120 or gp41 and may therefore interfere with one of these steps, thereby inhibiting target cell infection.

The general characteristics of antibody-mediated HIV-1 neutralization have been determined from studies of immune sera obtained from naturally infected people or after the specific immunization of humans and animals (7, 32). One of the most important findings of these studies was that clinically relevant primary isolates (PI) from infected patients are much more refractory to neutralization than TCLA strains (9, 25, 32). Indeed, although infected individuals often display a strong and sustained antibody response, they rarely generate antibodies able to neutralize PI. Neutralizing activity against autologous or heterologous PI is usually weak and detectable only late after seroconversion (29, 42). Moreover, PI are poorly, if at all, neutralized by immune sera obtained in response to recombinant envelope glycoprotein subunit-based vaccines (3, 11, 24). It has been suggested that this difference in sensitivity to neutralization is due to qualitative differences in the epitopes involved in the neutralization of PI from those involved in the neutralization of TCLA strains. In particular, as in other studies (4, 54), we have demonstrated that, in contrast to what is observed for TCLA strains, sequential epitopes of the V3 loop are not critical neutralizing targets for PI (46). There is some evidence that binding of antibodies to oligomeric forms, but not to the soluble monomeric form, of gp 120 is the factor most strongly correlated with PI neutralization (17, 33). Thus, discontinuous epitopes present on the correctly folded proteins, rather than linear epitopes, may be the relevant targets for efficient neutralizing antibodies. Antibodies to such conformational epitopes have been detected in HIV-positive sera (31) but not in vaccinated volunteers (53) in whom immunogens elicit antibodies that recognize linear epitopes, even with diverse specificities, and neutralize TCLA viruses but not PI (3, 21).

In addition, the epitopes involved in the neutralization of PI may be largely inaccessible. Indeed, several clusters of epitopes defined by antibody mapping (7, 32, 34) have been found to be exposed on several TCLA strains but occluded or masked on PI (5, 47). Epitopes on PI are nevertheless recognized by potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) such as IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5, which are capable of cross-clade neutralization (6, 10, 36, 49), but antibodies with these specificities are rarely induced. Structural data have recently provided new insight into the sites on the whole native protein that are accessible (57), demonstrating that the target epitopes for neutralizing antibodies occupy a limited space forming a neutralizing face on gp 120. A conserved bridging sheet involved in coreceptor binding is exposed once CD4 is bound. This site comprises the CD4-induced epitopes, poorly recognized on cell-free viruses but exposed upon binding to receptors and subsequent conformational changes. These epitopes include that recognized by the MAb 17b (19). Additional evidence for a role of such induced epitopes are provided by induction by fusion-competent complexes of antibodies neutralizing a broad spectrum of PI (20). This opens up new possibilities for the identification of crucial neutralization epitopes and characterization of their exposure during the infection process. The accessibility of such epitopes is likely to affect the mechanism of antibody-mediated neutralization.

In contrast to what was initially thought, steric inhibition of contact with target cells occurs only rarely and may not be a common mechanism of neutralization for enveloped viruses (12). For HIV, contradictory results have been obtained concerning the way in which antibodies inhibit infection. Postattachment neutralization phenomena, such as the inhibition of fusion, have been described (1, 2, 26). In such cases, the neutralizing antibodies react with the virus after it has become attached to the cell but before it is internalized. In contrast, other studies have suggested that inhibition of attachment is the principal mechanism of neutralization (51). These differences in results cannot be attributed to the antibodies used, as the MAbs used were identical in some of these studies. Moreover, the viruses analyzed in these studies were TCLA strains and not PI. However, there were differences in the experimental conditions and methods used to detect the binding of the virus.

As PI are probably more clinically relevant, we investigated the mechanism of PI neutralization. We carried out kinetics experiments that enabled us to discriminate preattachment from postbinding mechanisms of inhibition to determine which steps of the viral cycle, including attachment and entry, were impaired. Further binding assays were then done to analyze early entry events. We also carried out a parallel analysis in which PI were used to infect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or the TCLA virus HIV-1MN to infect MT-4 cells, to facilitate the comparison of our results with published data. We found that the mechanism of neutralization differed according to the virus and the cells considered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, sera, and antibodies.

The human T4 lymphoblastoid cell line MT-4, the CD4+ T-cell clone PM1 (22), an HLA-DR-/CD4+ line A3.01 stably expressing CCR5 coreceptor (kind gift from Q. Sattentau), and primary PBMC, isolated by Ficoll gradient purification and stimulated for 3 days with 2 μg of phytohemagglutinin A (PHA; Sigma) per ml, were used as target cells for the replication and the neutralization of different HIV-1 strains. All cell types were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and, for PBMC, with 20 IU of interleukin-2 (Roche) per ml.

Strain HIV-1MN was used as a prototype of TCLA viruses. This strain was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and amplified both on the MT-4 cell line and on PBMC to constitute the viral stocks HIV-1MN/MT-4 and HIV-1MN/PBMC as previously described (46).

Sera and PI were collected from the same patients. PI Bx26 and Bx17 were kindly provided by the laboratory of virology of H. Fleury, Bordeaux, France. They were isolated, early after seroconversion, by coculture of the patient's PBMC with PHA-stimulated PBMC from healthy seronegative donors as described elsewhere (42). They were propagated once or twice exclusively on PHA-stimulated PBMC to obtain viral stocks. Bx26, a subtype B virus, and Bx17, subtype A, both replicate in GHOST cells expressing CCR5 but not in GHOST cells expressing CXCR4 and therefore have an R5 phenotype.

Sera were collected at various times after infection. In a previous study, the autologous and heterologous neutralizing activities were determined in sequential serum samples, and those demonstrating the highest neutralizing titers were selected for this study. Serum 2, available through the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and provided by the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA, was collected from an asymptomatic subject by repeated bleeding over a 10-month course (55). This serum is commonly used as reference serum because of its broad neutralizing activity. The well-known MAb IgG1b12, which recognizes a conformational CD4 binding site (CD4bs) epitope (6), was kindly provided by Paul W. H. I. Parren (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, Calif.).

Purification of IgG on protein A columns.

Sera were fractionated by chromatography on protein A-Sepharose columns (Pharmacia). The flowthrough fraction containing soluble seric factors that could influence the outcome of the neutralization was removed, whereas purified immunoglobulins (Ig) retained on the columns were collected after elution with a low-pH buffer (0.1 M glycine [pH 3]). To assess the efficacy of Ig separation, the presence of Ig from different classes was assessed in all the fractions collected during the purification procedure using an in-house specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, microtitration plates were coated with anti-human IgA, IgG, and IgM at 1/1,000 (The Binding Site, Birmingham, United Kingdom) in 50 mM bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) overnight at 4°C. After a 2-h blocking step with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% nonfat milk, successive dilutions of fractions were incubated for 2 h, and retained Ig were subsequently revealed using an anti-human Ig-horseradish peroxidase conjugate at 1/10,000 (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.). A standardization of the purification protocol allowed us to elute and collect a single fraction containing IgG, fivefold diluted with respect to the serum. This fraction was filtered through a 45-μm-pore-size Costar filter and used in the neutralization assay at IgG concentrations corresponding to that present in the serum.

Neutralization assays and kinetics of neutralization.

In vitro assays allowing detection of a neutralizing activity in sera are described elsewhere (28, 46). Two neutralization protocols were used to study either TCLA viruses replicating in transformed T-cell lines or PI multiplying in PBMC. For both assays, extensive washings were performed to eliminate unbound viruses and excess antibodies.

The neutralization test performed on PBMC (pool of five donors) was described in detail elsewhere (29). The characteristics of this assay are that it combines serial dilutions of virus with serial dilutions of sera, instead of using a single defined viral input, and is based on detecting a 10-fold virus titer reduction in the presence of immune sera or IgG. The main advantages are that the influence of the amount of virus used in the assay on the antibody titer, as well as the effect of differences in the efficacy of virus replication in PBMC from different donors, is minimized.

Briefly, 50-μl aliquots of four fourfold dilutions of virus, beginning with about 800 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50)/ml, were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 50 μl of serial serum or IgG dilutions in a 96-well filtration plate (Durapor-Dv, 1.25-μm pore size; Millipore, Molsheim, France), before addition of 105 PHA-stimulated PBMC (pool of five seronegative donors). After 2 h at 37°C, extensive washings (thrice with 200 μl of RPMI 1640) were done to remove unbound virus and antibodies. Cells were then cultured in 200 μl of RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum and 20 IU of interleukin-2 per ml. Half of the medium was changed at 4 days postinfection, and viral production was measured at 7 days postinfection or sometimes later if the viral replication was weak. For each serum dilution, the assay was performed in quadruplicate and HIV-positive wells were identified by the level of p24 antigens (ELISA kit; Du-Pont or Innogenetics, Zwijndrecht, Belgium) in the culture supernatants. This allowed the viral titer (TCID50) to be calculated, in the presence (Vn) and in the absence (Vo), of the serum, by the Reed and Muench method. Fifty percent neutralization corresponds to inhibition of virus replication in two wells which is insufficient to obtain a reproducible determination of the titer (29). Thus, the neutralization titer of the serum was defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that resulted in a 10-fold decrease in the viral titer (Vn/Vo = 0.1). For a given dilution of serum, a neutralization percentage was also defined as 100 − (Vn/Vo × 100).

For HIV-1MN/MT-4, the neutralizing activity of the serum was detected by its ability to inhibit the cytopathic effect (CPE) induced by virus replication in MT-4 cells and/or by the inhibition of reverse transcriptase (RT) activity detected in the culture supernatants. According to the protocol, 50 μl of HIV-1MN virus stock containing 4 TCID50 was preincubated for 1 h at 37°C with 50 μl of serial serum dilutions. Subsequently, 105 MT-4 cells were added for an additional hour at 37°C. As for the assay with PBMC, the use of 96-well filtration plates allowed extensive washings to be done. After 5 days of culture, cell viability was measured by a colorimetric assay described before (41). The absorbance measured at a wavelength of 540 nm was correlated with the number of living cells, and percentage of protection in the presence of the sera was calculated according to the Pauwels formula (41). The neutralization titer of the serum was defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that allows 50% protection against the virus-induced CPE.

Viral production could also be assessed by measurement of the RT activity associated with virions released in culture supernatants (30) taken at various times postinfection. A 50% inhibition of RT activity, chosen as the criterion to define the serum neutralization titer, gave similar results.

Kinetics of infection.

Kinetics of infection were tested to ascertain the time needed by the virus to bind to and undergo irreversible fusion and entry into target cells. Assays of infection were carried out as for neutralization assays in 96-well filtration plates except that no immune serum was added. For various periods of time (up to 4 h), TCLA HIV-1MN/MT-4 or PI were put in contact with target cells, MT-4 or PBMC, respectively. Washings were then performed, either three times with 200 μl of RPMI 1640 to remove nonattached virus or with 200 μl of RPMI 1640 followed by 200 μl of trypsin (1:250; Gibco BRL) for 5 min at room temperature and additional 200 μl of RPMI 1640, which eliminated the majority of adsorbed but noninternalized virus.

Assays were performed at two temperatures (37 and 4°C) to distinguish viruses just adsorbed onto cells (at 4°C) from viruses that had undergone fusion and penetrated into cells (at 37°C). Viral production was assessed at 5 or 6 days postinfection by RT activity in the culture supernatants. Assays were performed in quadruplicate.

Assays for attachment of free HIV-1 virions or neutralized HIV-1 particles onto target cells.

Aliquots of 500 μl containing 100 TCID50 of HIV-1MN/MT-4 or 150 TCID50 of PI were added to target cells (5 × 106 cells in 500 μl of medium) and incubated for 1 h with MT-4 cells or 2 h with PBMC at 4°C. At this temperature, virus attaches to the target cells with minimal entry. Unbound virus was removed by extensive washings (three cycles of 10 min of centrifugation at 1,200 rpm and at 4°C) with cold RPMI 1640. The amount of HIV attached to cells was determined, after lysis of virus-cell complexes with 10% NP-40 lysis buffer, by quantitation of p24 antigens by ELISA. The binding of neutralized HIV-1 was determined in the same way except that dilutions of serum or purified Ig fractions were preincubated with the virus before addition to the cells. Percentage of association was defined as the ratio of p24 associated with cells in the presence of neutralizing sera to the p24 detected in the absence of neutralizing sera. Trypsin treatment of cells was included during washings to remove the absorbed virus. For this purpose, the cells were treated with 5 ml of trypsin (1:250; Gibco BRL) for 5 min at room temperature before the first and second washes.

Neutralization in each sample was determined by removing one-fifth of the infected cells after the washing step and culturing them in 200 μl for measuring single-round production of virus. For this purpose, virus multiplication was determined as the amount of p24 antigens released in culture supernatants 32 h after infection. A control, done by culturing an aliquot of infected cells in the presence of 10−6 M Zidovudine (AZT), was included to measure the amount of residual input p24 in the culture supernatants. We measured p24 antigens produced in cells infected in the presence (p24 with serum) or absence (p24 control) of neutralizing serum and deducted the residual p24 detected in wells containing AZT. Percentage of neutralization was determined as (p24 with serum − p24 with serum (AZT)/p24 control − p24 control (AZT)) × 100.

Detection of virus entry.

The assay was carried out in the same way as for analysis of virus attachment except that incubations were done at 37°C for 2.5 h to allow the occurrence of fusion and entry. Levels of p24 obtained without trypsin treatment represent the total amount of cell-associated HIV, including fixed and internalized virus, whereas the virus that has penetrated into the cells is given by the amount of p24 measured after incubation with trypsin.

Entry into cells was assessed by PCR detection of proviral DNA. Infection of cells was performed at 4 and 37°C in the presence and in the absence of immune serum or in the presence of 10−6 M AZT. After 20 h of culture, DNA was extracted from 106 cells using a commercial kit (QIAamp tissue kit; Qiagen). The gag gene fragment, delineated by PCR primers SK38 (5′-ATAATCCACCTATCCACGTAGGAGAAAT-3′) and SK39 (5′-TTTGGTCCTTGTCTTATGTCCAGAATGC-3′), was amplified by 35 cycles consisted of 92°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and were revealed under UV as products of 112 bp.

U1 cells are HIV-1 chronically infected cells derived from the promonocyte U937 cells. They contain two copies of the HIV-1 genome and were used as a positive control for DNA amplification.

RESULTS

Kinetics of neutralization.

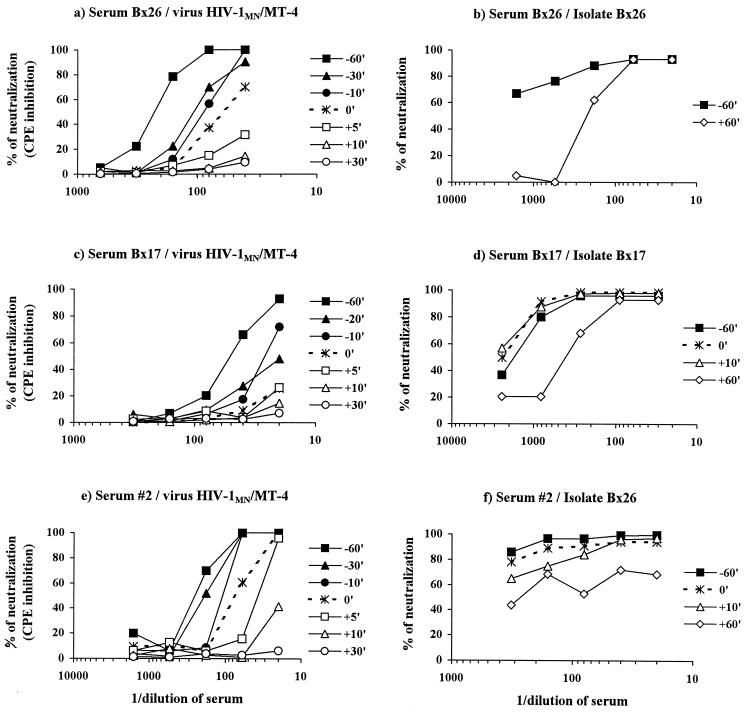

The aim of these experiments was to determine whether antibodies neutralized the virus before or after the viral particle becomes associated with the cell. We added sera to viruses at various times before and after adsorption onto target cells. We assessed neutralization of the TCLA virus HIV-1MN amplified in MT-4 cells and of PI replicating in PBMC (Fig. 1). For the TCLA strain, prior incubation of the immune serum with the virus before its addition to target cells gave the highest level of neutralization. Indeed, if virus and serum were incubated together for 1 h before being added to MT-4 cells, high titers of neutralizing antibodies were obtained. Neutralization was defined as 50% inhibition of the virus-induced CPE, and the titers of neutralizing antibodies obtained were 50, 250, and 250, respectively, for sera Bx17, Bx26, and 2. Incubation of the three components (cells, virus, and sera) together gave markedly lower titers of neutralizing antibodies: <20, 60, and 50, respectively, for sera Bx17, Bx26, and 2. Adding sera after the cells and viruses had been mixed together resulted in even lower levels of neutralizing activity. Therefore, for this TCLA strain, neutralization appears to require the interaction of neutralizing antibodies with the cell-free virions before binding of the virus to MT-4 cells, suggesting inhibition of very early steps of infection. In contrast, different neutralization kinetics were observed for PI, whether autologous or heterologous. The superimposed curves indicate that neutralization was similar whether the Bx17 serum was incubated for 1 h with the autologous PI Bx17 before being added to cells, added at the time of adsorption, or added 10 min after initial contact of the virus with PBMC. Furthermore, although weak, neutralizing activity against the corresponding autologous virus was nonetheless detected if Bx26 or Bx17 serum was added up to 1 h after virus and cells were mixed. The lower level of neutralization if sera were added 1 h after the initial virus-cell interaction, rather than 1 h before, may indicate the escape from neutralization of viruses that had already penetrated into the cells. It may also indicate the presence of various antibodies mediating neutralization by different mechanisms.

FIG. 1.

Neutralization of the TCLA strain HIV-1MN/MT-4 (a, c, and e) and primary isolates (b, e, and f) by whole sera Bx26 (a and b), Bx17 (c and d), and 2 (e and f). Sera were incubated with virus for 60, 30, 20, or 10 min before addition to cells (closed symbols), incubated simultaneously with virus and cells (dotted line), or added 5, 10, 30, or 60 min after cells and viruses were mixed (open symbols). Experiments with HIV-1 MN/MT-4 used the MT-4 cell line, and inhibition of virus-induced cytotoxicity was assessed. Neutralization of primary isolates was assessed using PBMC and reduction in infectivity.

We assessed the neutralization of a heterologous virus, Bx26, by serum 2 and of the autologous virus by serum Bx26 or Bx17. The level of neutralization was slightly lower if the serum was added 10 min after the initial virus-cell contact. However, serum added 1 h after the initial contact was unable to neutralize virus Bx26 completely (at least 90% inhibition), although 60% neutralization was repeatedly achieved. The incomplete inhibition observed with serum 2 may therefore be attributed to less specific antibodies and/or antibodies neutralizing by different mechanisms. The neutralization kinetics of PI Bx26 by serum 2 differed from those for the neutralization of TCLA HIV-1MN on MT-4 cells.

Other evidence consistent with the inhibition of different steps of the viral cycle was provided by further kinetics assays. Sera were added to the neutralization assay after viruses and cells had been incubated together for 1 h at either 4 or 37°C (Table 1). We aimed in these experiments to dissociate adsorption, which occurs at both temperatures, from the penetration process mediated by fusion of the virus with cell membranes, which occurs at 37°C only. Neutralization was compared to that obtained in the standard test if serum and virus were incubated together for 1 h before addition to cells (protocol 1). For the TCLA strain HIV-1MN, the addition of sera after virus-cell adsorption (1 h at 4°C; protocol 2) or after adsorption and penetration (1 h at 37°C; protocol 3) gave similar results, i.e., a more than 10-fold decrease in neutralizing titer if virus and serum were incubated together before addition to cells, demonstrating that antibodies neutralize before attachment (Table 1). Conversely, the primary autologous isolate adsorbed at 4°C onto PBMC (protocol 2) was highly susceptible to neutralization, as indicated by a neutralization titer similar to that measured if virus and serum were incubated together before addition to cells (protocol 1). If cells and viruses were incubated together at 37°C 1 h before the addition of serum (protocol 3), the neutralization titer was six times lower than that measured with protocol 1. These data confirm previous observations and suggest that PI are neutralized after virus adsorption but before entry into the cell.

TABLE 1.

Neutralization with HIV-positive sera using different protocols

| Virus | Serum | Neutralization titera

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol 1b | Protocol 2c | Protocol 3d | ||

| HIV-1MN/MT-4 | Bx17 | 400 | <40 | <40 |

| HIV-1MN/MT-4 | Bx26 | 750 | 50 | 60 |

| Bx17/PBMC | Bx17 | 360 | 590 | 60 |

Reciprocal of serum dilution inducing 50% inhibition of the virus-induced cytotoxicity on MT-4 cells or a 10-fold decrease in TCID50 on PBMC.

Preincubation of virus plus serum for 1 h at 37°C before infection of cells.

Addition of immune serum after incubation of virus and cells for 1 h at 4°C.

Addition of immune serum after incubation of virus and cells for 1 h at 37°C.

Kinetics of infection.

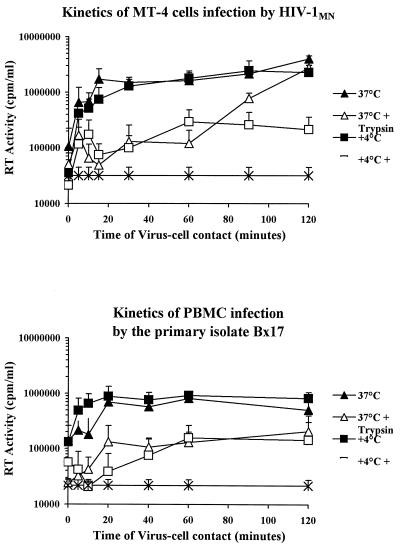

As a lower rate of infection of PBMC could contribute to the observed difference in neutralization kinetics, we compared the infection rates of transformed MT-4 cells and PBMC. Target cells were incubated in the presence of virus preparations for various periods of time. Experiments were performed at either 4 or 37°C, and the cells were treated with trypsin after incubation to remove attached virions that had not penetrated the cell. Virus production was assessed in cultures of untreated cells and cells treated with trypsin.

We found that adsorption onto cells was rapid and efficient for both cell types and at both temperatures. Indeed, as indicated by the steep slope of the curves, maximal infection was achieved within the first 15 to 20 min (Fig. 2). To assess virus entry into the cells, we treated cells incubated at 4 or 37°C with trypsin. This treatment did not remove all adsorbed virus that did not penetrate into cells, as indicated by the low level of virus replication in cells treated with trypsin after adsorption at 4°C (Fig. 2). Following incubation at 37°C, viruses remained sensitive to trypsin treatment for more than an hour, suggesting that the fusion process was slow for both cell types. Differences in infection rates between MT-4 cells and PBMC therefore cannot account for the observed differences in neutralization kinetics in the first hour.

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of infection of MT-4 cells by the TCLA strain HIV-1 MN/MT-4 and of PBMC by the PI Bx17. Virus and cells were incubated for various times at 4 or 37°C to distinguish virus adsorption from virus internalization. After various times of virus-cell contact, the cells were washed and not treated or treated with trypsin to remove adsorbed virus that had not undergone fusion and penetrated into cells. Virus production was assessed after 5 to 6 days of culture by determining RT activity in the supernatant. Each point is the mean ± standard error of RT activity for four independent replicates.

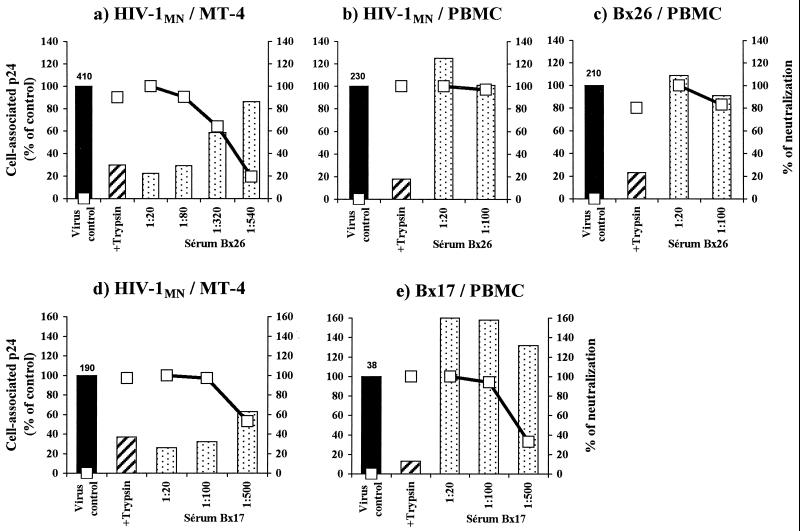

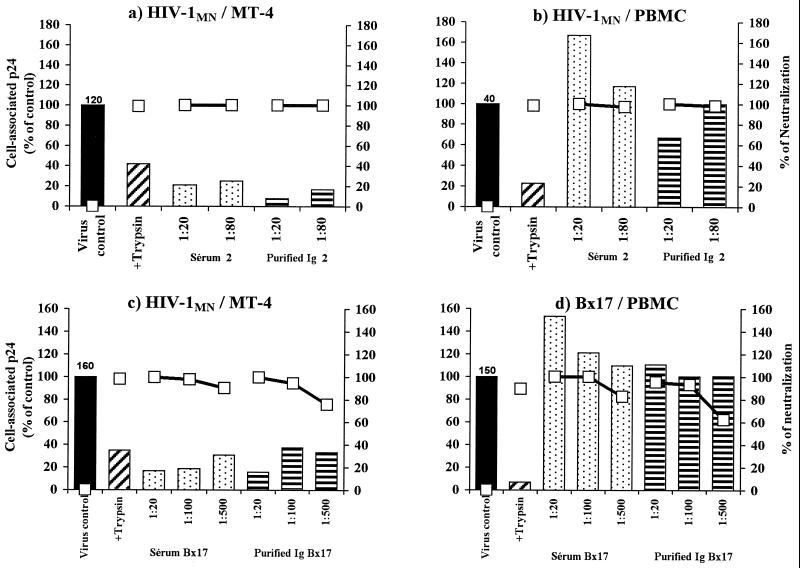

Inhibition of adsorption onto target cells: correlation with neutralization?

We assessed the effect of the immune serum on virus adsorption onto cells by measuring the amount of p24 antigen associated with target cells. The percentage of virus association in the presence of serum was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. We evaluated neutralization in parallel by determining the amount of virus released into culture supernatants after 32 h. For MT-4 cells infected with HIV-1MN/MT-4, dose-dependent inhibition of cell-associated p24 and dose-dependent neutralization were observed for all sera tested (Fig. 3a and d and 4c). However, if PBMC were infected with HIV-1MN produced in MT-4 cells or PBMC, serum treatment did not inhibit the association of virus and cell, even at the highest concentration, but nonetheless neutralized the virus (Fig. 3b and 4b). The efficient neutralization observed indicates that viruses attached to cells did not progress to productive infection of PBMC (Fig. 3). If sera were sufficiently diluted, neutralization was dose dependent (Fig. 3e and data not shown). For PI Bx17, an increase in associated p24 antigens was detected on addition of serum Bx17 (Fig. 4). A 1.5- to 2.7-fold increase in associated p24 was consistently observed if this serum was incubated with Bx17 PI. This phenomenon was not observed using protein A-purified IgG from this serum (Fig. 4d) but was due to components present in the flowthrough fraction (data not shown). The IgG fraction, retained and eluted from the column, gave 100% neutralization but did not decrease the amount of virus adsorbed onto the cells (Fig. 4), indicating that these antibodies act after virus attachment to PBMC.

FIG. 3.

Detection of adsorption and neutralization in the presence of immune sera Bx26 (a to c) and Bx17 (d and e). Dilutions of sera were incubated with either HIV-1 MN/MT-4, HIV-1 MN/PBMC, or the corresponding autologous PI. Virus-serum mixtures incubated for 1 h were added to target cells (MT-4 cells [a and d] or PBMC [b, c, and e]) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h to allow attachment. The cells were then thoroughly washed, and viruses attached to cells were detected by p24 ELISA. Attachment (bars) is expressed as the percentage of virus bound in the presence of serum versus the amount of virus bound without serum (black bar; the amount [picograms] of p24 associated with cells is indicated at the top). Neutralization was determined by culturing a sample of cells removed from mixtures after the washing procedure. p24 production, determined in the culture supernatant after 32 h of culture (open squares), ranged from 1.5 to 10 ng/ml. Trypsin treatment, which eliminates adsorbed viruses, was included to assess the residual p24 associated with the cells. Curves show percentages of neutralization for the various serum dilutions, calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Human serum from an HIV-seronegative donor did not neutralize the virus or affect its attachment to cells (data not shown). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

FIG. 4.

Detection of adsorption at 4°C and neutralization in the presence of IgG purified from serum 2 (a and b) or Bx17 (c and d). The viruses used were HIV-1 MN/MT-4 to infect MT-4 cells (a and c) or HIV-1 MN/PBMC (b) and the primary isolate Bx17 (d) to infect PBMC. See the legend to Fig. 3 for details of the methods used. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Thus, the interaction of virus and cell is inhibited with MT-4 cells but not with PBMC used as target cells. We investigated further the role of target cells by carrying out experiments with other cell lines (CEM-SS, CEM174, or cell lines expressing the CCR5 coreceptor, such as PM1 and A3/CCR5). Cell lines that express the CCR5 coreceptor can be infected with PI of the R5 type, but virus adaptation to the cell line was necessary to measure neutralization. Regardless of the cell line used, neutralizing sera inhibited the interaction of virus and cell (data not shown). Thus, in contrast to what was observed for PBMC, neutralizing sera inhibit virus-cell interaction with these cell lines.

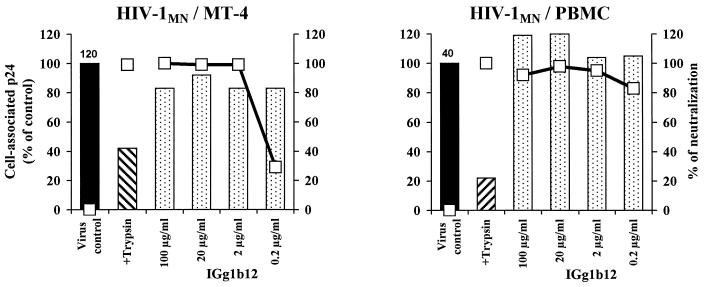

We used the CD4bs MAb IgG1b12 as a reference antibody in our study (Fig. 5). The addition of up to 100 μg of this antibody per ml to either HIV-1MN/MT-4 or HIV-1MN/PBMC with MT-4 cells or PBMC, respectively, as target cells did not affect virus-cell association. However, IgG1b12 at a concentration of 2 μg/ml was sufficient to neutralize these viruses. Isolates Bx26 and Bx17 were not used in these experiments as they were not neutralized by IgG1b12. For two other PI (Bx08 and Bx19) neutralized by IgG1b12, the level of p24 association was not found to be lower with PBMC (data not shown). Unlike the neutralizing Ig purified from HIV-infected individuals, MAb IgG1B12 does not inhibit the association of HIV-1MN with MT-4 target cells.

FIG. 5.

Detection of adsorption at 4°C and neutralization in the presence of the anti-CD4bs MAb IgG1b12. Association (bars) and neutralization (open squares) experiments were done with either HIV-1 MN/MT-4 or HIV-1 MN/PBMC on MT-4 cells or PBMC, respectively, using different concentrations of antibody as indicated (see legend to Fig. 3).

Assessment of viral entry.

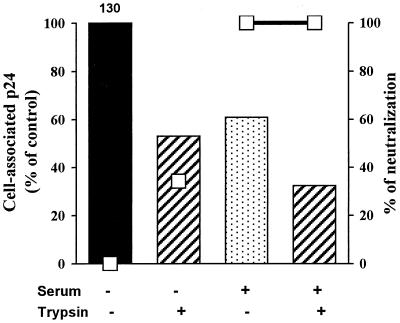

We performed association experiments with an incubation for 2 h at 37°C to allow the virus to enter the cell. In these conditions, the residual p24 measured after trypsin treatment reflects internalized virus that became resistant to trypsin because it penetrated into cells. In the presence of immune serum, about 50% less p24 was found to be associated with PBMC at 37°C after trypsin treatment (Fig. 6 and data not shown). This suggests that the immune serum decreased virus entry into PBMC, although no inhibition of virus association with cells was observed (experiments at 4°C in Fig. 3 and 4). However, although the serum led to 100% neutralization, treatment with trypsin removed only about 70% of cell-associated p24. The residual p24 detected may, in part, correspond to viruses that have entered the cell by endocytosis. As about 55% of viral p24 has been shown to penetrate lymphoblastoid cells by this route (23), this process may not be inhibited by neutralizing sera.

FIG. 6.

Detection of adsorption at 37°C (bars) and neutralization (open squares) of virus Bx26 on PBMC in the presence of serum Bx26. The experimental conditions were identical to those described in the legend of Fig. 3 except that the 2-h incubation allowing association was done at 37°C, after which cells were assayed directly or treated with trypsin. The histograms are representative of three independent experiments.

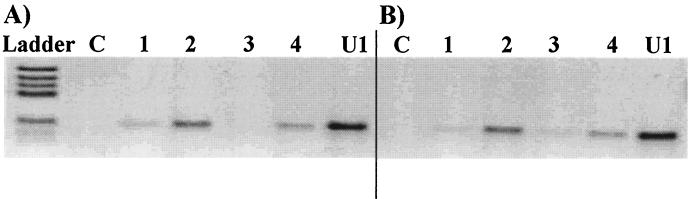

We detected proviral DNA by PCR to determine if reverse transcription, an early step in the replicative cycle, had occurred. We showed that the presence of immune neutralizing sera prevented the detection of amplified products to a greater extent than did AZT (Fig. 7). Reverse transcription of the genomic RNA therefore did not occur, probably due to the inhibition of entry into cells. Neutralization experiments carried out in parallel confirmed that antibodies had inhibited virus replication.

FIG. 7.

Detection of a PCR-amplified fragment of HIV-1 DNA after infection of PBMC by PI Bx26 in various conditions. Lanes C, DNA from uninfected PBMC; lanes U1, DNA from chronically HIV-infected U1 cells (positive control). The neutralizing sera analyzed were serum 2 (A) and serum Bx26 (B). A fragment of the gag gene was amplified by 35 cycles of PCR with DNA from PBMC incubated with Bx26 at 4°C (lanes 1), 37°C (lanes 2), 37°C in the presence of neutralizing serum diluted 1/20 (lane 3), or 37°C in the presence of 10−6 M AZT (lane 4).

DISCUSSION

We investigated the antibody-mediated neutralization of HIV-1 PI by studying the mechanisms involved in the inhibition of infection of permissive cells in vitro. In a parallel study of the TCLA strain HIV-1MN infecting MT-4 cells and PI multiplying in PBMC, we showed that the steps of the viral cycle impaired by antibodies are different for TCLA strains and PI. We found that the inhibition of adsorption was the predominant mechanism leading to the neutralization of HIV-1MN on MT-4 cells. This was shown both by the requirement for neutralizing antibodies to interact with cell-free virus prior to addition to cells and by the high, dose-dependent correlation between the inhibition of virus attachment and neutralization. In contrast, a different mechanism of action was found to operate for antibodies neutralizing PI on PBMC. Indeed, we showed that PI neutralization occurred with identical (for serum Bx17) or similar (serum 2) efficiencies whether the immune sera were incubated with the virus before, concomitantly with, or soon after its addition to PBMC. Similar levels of neutralization were observed if the serum was incubated with the virus previously adsorbed onto target cells for 1 h at 4°C. Immune sera did not decrease PI adsorption onto PBMC, although they led to a loss of infectivity. More rapid entry of HIV-1MN into MT-4 cells cannot totally account for the difference in mechanisms of neutralization observed, as more than 1 h is required to achieve the maximum infection of these cells, as for PI in PBMC.

The nonspecific association of viruses with target cells may account for the postbinding neutralization of HIV-1 on PBMC. The effect of such target cell interaction in the neutralization mechanism has been described for many viruses (13). For HIV-1, interaction with heparan sulfates has been reported to be involved in attachment (26). Although this nonspecific attachment has been well documented for some cell lines, such as MT-4 (37, 40), no such heparan binding phenomena have been detected for PBMC and X4- or R5-type virus interactions (18). It is therefore unlikely that nonspecific binding of virus to heparan could account for the postbinding mechanism observed with PBMC. Recent studies have shown that polyanions present on the H9 cells interact with X4 or R5X4 gp 120 but interact only very weakly if at all with R5 gp120 (35). The authors suggested that the positive charges in the V3 loop of TCLA strains are involved in polyanion binding. Thus, antibodies directed against the sequential V3 loop, which we have previously shown to play a key role in inhibition of HIV-1MN infection in MT-4 cells (46), may interfere with polyanion binding. This would contribute to the inhibition of attachment and neutralization that we detected on MT-4 cells. As PBMC express lower levels of heparan sulfate than MT-4 cells (37), the postbinding neutralization mechanism observed in the case of HIV-1MN infection of PBMC may result from a decrease in the interaction of HIV-1MN with polyanions. Thus, the various types of polyglycan expressed on these two cell types may affect the way in which gp120 attaches to the cell, thereby affecting the mechanism of neutralization.

Other nonspecific virus-cell interactions have been described (38). Interaction between adhesion molecule 1 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 on target cells has been shown to render HIV-1 more refractory to neutralization (16). This nonspecific virus-cell interaction may be actively involved in the mechanism of neutralization.

We were unable to rule out the possibility that PI bind to PBMC via adhesion molecules because we were unable to inhibit the binding of PI to PBMC by adding anti-CD4 antibody to a concentration of 25 μM (clone SK3; Becton Dickinson) (data not shown). However, this concentration of anti-CD4 antibody did not prevent virus replication (data not shown), suggesting that higher concentrations may be required to inhibit PI infection of PBMC. Whether or not virus-PBMC association was mediated by interactions with receptor and coreceptor only, neutralizing antibodies present in the sera of infected individuals were able to inhibit infection after the virus (PI or HIV-1MN) had become attached to target cells. This was not the case for HIV-1MN attached to MT-4 cells.

Another explanation of the differences in neutralization mechanism may be that different antibodies directed against different epitopes are involved in the neutralization of viruses infecting PBMC and MT-4. As this study dealt with only whole serum or purified IgG, multiple antibodies with various specificities coexist in the samples tested and may neutralize HIV via different mechanisms.

We found that antibodies were able to neutralize PI that had already attached to cells but had not yet been internalized. This postattachment mechanism may involve an increased in the elution of attached virions, inhibition of fusion, or any event interfering with the pathway of virus entry and infection such as uncoating of the virus or interference with cell signaling. There is some evidence that sequential events after binding to CD4 are necessary for the initiation of fusion and HIV-1 entry. These events include secondary binding to the coreceptor and conformational changes. Studies of interactions of gp120 with CD4 and coreceptor have suggested that the gp120-CD4 complex formed is relatively stable (15) and leads to exposure of the coreceptor binding site. MAbs that block the binding of gp120-CD4 complexes to the coreceptor CCR5 have been reported to neutralize HIV (50, 56). In addition, the impairment of normal conformational changes or the induction of aberrant conformational changes may render the envelope fusion incompetent and prevent entry. The epitopes involved in PI neutralization may be occluded on the free virion and only accessible during fusion events. Obviously, for antibodies directed against such epitopes, postattachment inhibition is the only type of inhibition likely to occur. This is consistent with reports that neutralizing antibodies directed against a fusion-competent complex cross-neutralized a wide range of PI (20).

For HIV-1MN infecting MT-4 cells, the impairment of HIV adsorption observed may also result from steric inhibition of virus receptor binding by neutralizing antibodies directed against the CD4bs that are able to interfere with soluble gp120-CD4 binding. Experiments using a large panel of CD4bs MAbs and derivative Fabs have shown this to be the case (43, 51, 52). For the well-known MAb IgG1b12, directed against the CD4bs, conflicting results have been published. Ugolini et al. reported inhibition of attachment (51), whereas McInerney et al. showed inhibition of fusion by the whole antibody and an effect at an unidentified postfusion step for its Fab (26). In our hands, this antibody did not inhibit adsorption for either HIV-1MN or PI. Moreover, the kinetics of neutralization of HIV-1MN infecting MT-4 cells confirmed a postbinding mechanism for this antibody (data not shown).

Ugolini et al. extended their conclusion to antibodies binding to epitopes other than the CD4bs including V2, V3, and complex gp120 epitopes. Apart from the gp41-specific antibody 2F5, the neutralizing MAbs that they tested inhibited the attachment of TCLA viruses (51). They suggested that because the face of gp120 subjected to antibody attack is limited in size, antibodies may cause physical hindrance whether the epitope is close to or distant from the CD4bs. This is consistent with the observation that neutralization is correlated with antibody occupancy irrespective of the epitopes recognized, neutralization being efficient if a critical number of receptor binding sites are blocked (39). This mechanism of inhibition may predominate for TCLA strains if MT-4 cells are used as target cells, but this steric mechanism may not operate if PBMC are used.

Overall, conflicting data have been reported concerning the neutralization mechanism of TCLA strains infecting T-cell lines. The differences in the results published may be attributed to the experimental conditions used. We found that the mechanism of neutralization was also largely dependent on the target cell used. The various levels of expression of receptor and coreceptor, but also of other adhesion molecules, may modify the way in which viruses attach to cells and are neutralized. These results may have implications for the choice of virus and target cell for neutralization assays in vitro designed to characterize the antibodies involved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sandrine Haessig and Virginie Roques for technical assistance and Renaud Burrer for fruitful discussion.

This work was supported by a grant from l'Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA and Synthélabo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong S J, Dimock N J. Varying temperature dependence of post attachment neutralization of HIV-1 by monoclonal antibodies to gp120: identification of a very early fusion independent event as a neutralization target. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1397–1402. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong S J, McInerny T L, McLain L, Wahren B, Hinkula J, Levi M, Dimock N J. Two neutralizing anti-V3 monoclonal antibodies act by affecting different functions of HIV-1. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2931–2941. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beddows S, Lister S, Cheingsong-Popov R, Bruck C, Weber J. Comparison of antibody repertoire generated in healthy volunteers following immunization with a monomeric recombinant gp120 construct derived from CCR5/CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate with sera from naturally infected individuals. J Virol. 1998;73:1740–1745. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1740-1745.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beddows S, Louisirirotchanakul S, Cheingsong-Popov R, Easterbrook P J, Simmonds P, Weber J. Neutralization of primary and T-cell line adapted isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: role of V3-specific antibodies. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:77–82. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-1-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bou-Habib D C, Roderiquez G, Oravecz T, Berman P W, Lusso P, Norcross M A. Cryptic nature of envelope V3 region epitopes protects primary monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from neutralization. J Virol. 1994;68:6006–6013. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6006-6013.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton D R, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp S J, Thornton G B, Parren P W H I, Sawyer L S W, Hendry R M, Dunlop N, Nara P L, Lamacchia M, Garratty E, Stiehm E R, Bryson Y J, Cao Y, Moore J P, Ho D D, Barbas C F., III Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton D R, Montefiori D C. The antibody response in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1997;11:S87–S98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan D C, Kim P S. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J. Jitters jeopardize AIDS vaccine trials. Science. 1993;262:6574–6578. doi: 10.1126/science.8235635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conley A J, Kessler J, Boots L J, Tung J S, Arnold B A, Keller P M, Shaw A R, Emini E A. Neutralization of divergent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants and primary isolates by IAM-41-2F5, an anti-gp41 human monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3348–3352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor R, Korber N T M, Graham B S, Han B H, Ho D D, Walker B D, Neumann A U, Vermund S H, Mesteckly J, Jackson S, Fenamore E, Cao Y, Gao F, Kalams S, Kunstman K L, McDonald D, McWilliams N, Trkola A, Moore J P, Wolinski S M. Immunological and virological analyses of persons infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 while participating in trials of recombinant gp 120 subunit vaccines. J Virol. 1998;72:1552–1576. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1552-1576.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimmock N J. Neutralization of animal viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1993;183:1–149. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimmock N J. Update on the neutralization of animal viruses. Rev Med Virol. 1995;5:165–179. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doms R W, Peipert S C. Unwelcomed guests with master keys: how HIV use chemokine receptors for cellular entry. Virology. 1997;235:179–190. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doranz B J, Baik S S W, Doms R W. Use of a gp120 binding assay to dissect the requirements and kinetics of the human immunodeficiency virus fusion events. J Virol. 1999;73:10346–10358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10346-10358.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin J F, Cantin R, Bergeron M G, Tremblay M J. Interaction between virion-bound host intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and the high-affinity state of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 on target cells renders R5 and X4 isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 more refractory to neutralization. Virology. 2000;268:493–503. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouts T R, Binley J M, Trkola A, Robinson J E, Moore J P. Neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate JR-FL by human monoclonal antibodies correlates with antibody binding to the oligomeric form of the envelope glycoprotein complex. J Virol. 1997;71:2779–2785. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2779-2785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim J, Griffin P, Coombe D R, Ridera C C, James W. Cell surface heparan sulfate facilitates HIV-1 entry into some cell lines but not primary lymphocytes. Virus Res. 1999;60:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaCasse R A, Follis K E, Trahey M, Scarborough J D, Littman D R, Nunberg J H. Fusion-competent vaccines: broad neutralization of primary isolates of HIV. Science. 1999;283:357–362. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loomis L D, Deal C D, Kersey K S, Burke D S, Redfield R R, Birx D L. Humoral responses to linear epitopes on the HIV-1 envelope in seropositive volunteers after vaccine therapy with rgp160. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;10:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lusso P, Cocchi F, Balotta C, Markham P D, Louie A, Farci P, Pal R, Gallo R C, Reitz M S., Jr Growth of macrophage-tropic and primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolates in a unique CD4+ T-cell clone (PM1): failure to downregulate CD4 and to interfere with cell-line-tropic HIV-1. J Virol. 1995;69:3712–3730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3712-3720.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marechal V, Clavel F, Heard J-M, Schwartz O. Cytosolic Gag p24 as an index of productive entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:2208–2212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2208-2212.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mascola J R, Snyder S W, Weislow O S, Belay S M, Belshe R B, Schwartz D H, Clements M L, Dolin R, Graham B S, Gorse G J, Keefer M C, McElrath M J, Walker M C, Wagner K F, McNeil J G, McCuthan F E, Burke D S for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Evaluation Group. Immunization with envelope subunit vaccine products elicits neutralizing antibodies against laboratory-adapted but not primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:340–348. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews T J. Dilemma of neutralization resistance of HIV-1 field isolates and vaccine development. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;6:631–632. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInerney T L, McLain L M, Armstrong S J, Dimmock N J. A human IgG1 (b12) specific for the CD4 binding site of HIV-1 neutralizes by inhibiting the virus fusion entry process, but Fab neutralizes by inhibiting a postfusion event. Virology. 1997;233:313–326. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mondor I, Ugolini S, Sattentau Q J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 attachment to HeLa CD4 cells is CD4 independent and gp120 dependent and requires cell surface heparans. J Virol. 1998;72:3623–3634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3623-3634.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moog C, Fleury H J A, Pellegrin I, Kirn A, Aubertin A M. Autologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody responses following initial seroconversion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1997;71:3734–3741. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3734-3741.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moog C, Spenlehauer C, Fleury H J A, Heshmati F, Saragosti S, Letourneur F, Kirn A, Aubertin A M. Neutralization of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: a study of parameters implicated in neutralization in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:19–27. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moog C, Wick A, Le Ber P, Kirn A, Aubertin A N. Bicyclic imidazo derivatives, a new class of highly selective inhibitors for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antivir Res. 1994;24:275–288. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore J P, Ho D D. Antibodies to discontinuous or conformational sensitive epitopes on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are highly prevalent in sera of infected humans. J Virol. 1993;67:863–875. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.863-875.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore J P, Ho D D. HIV-1 neutralization: the consequences of viral adaptation to growth on transformed T-cells. AIDS. 1995;9:S117–S136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore J P, Cao Y, Qing L, Sattentau Q J, Pyati J, Koduri R, Robinson III J, Barbas C F, Burton D, Ho D D. Primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are relatively resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies and their neutralization is not predicted by studies with monomeric gp120. J Virol. 1995;69:101–109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.101-109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore J P, Sattentau Q J, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Probing the structure of the human immunodeficiency virus surface glycoprotein gp120 with a panel of monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1994;68:469–484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.469-484.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moulard M, Lortat-Jacob H, Mondor I, Roca G, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Zhao L, Olson W, Kwong P D, Sattentau Q. Selective interactions of polyanions with basic surfaces on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120. J Virol. 2000;74:1948–1959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1948-1960.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Rüker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohshiro Y, Murakami T, Matsuda K, Nishioka K, Yoshida K, Yamamoto N. Role of cell surface glycosaminoglycans of human T cells in HIV-1 infection. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:827–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orentas R J, Hildreth J E K. Association of host cell surface adhesion receptors and other membrane proteins with HIV and SIV. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;11:1157–1165. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parren P W H I, Mondor I, Naniche D, Ditzel H J, Klasse P J, Burton D R, Sattentau Q J. Neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by antibody to gp120 is determined primarily by occupancy of sites on the virion irrespective of epitope specificity. J Virol. 1998;72:3512–3519. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3512-3519.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pastel M, Yanagishita M, Roderiquez G, Bou-Habib D C, Oravecz T, Hascall V C, Norcross M A. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates HIV-1 infection of T-cell lines. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;9:167–174. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pauwels R, Balzarini J, Baba M, Snoeck R, Schols D, Herderwijn P, Desmyter J, De Clerck E. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorometric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. J Virol Methods. 1988;20:309–321. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(88)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pellegrin I, Legrand E, Neau D, Bonot P, Masquelier B, Pellegrin J L, Ragnaud J-M, Bernard N, Fleury H J A. Kinetics of appearance of neutralizing antibodies in 12 patients with primary or recent HIV-1 infection and relationship with plasma and cellular viral loads. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1996;11:438–447. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posner M R, Hideshima T, Cannon T, Mukherjee M, Mayer K H, Byrn R A. An IgG monoclonal antibody that reacts with HIV-1/gp120 inhibits virus binding to cells and neutralizes infection. J Immunol. 1991;146:4325–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J Exp Med. 1991;174:407–415. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P, Vignaux F, Traincard F, Poignard P. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J Virol. 1993;67:7383–7393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7383-7393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spenlehauer C, Saragosti S, Fleury H J A, Kirn A, Aubertin A M, Moog C. Study of the V3 loop as target epitope for antibodies involved in the neutralization of primary isolates versus T-cell-line-adapted strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:9855–9864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9855-9864.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stamatatos L, Cheng-Mayrer C. Structural modulation of the envelope gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon oligomerization and differential V3 loop epitope exposure of isolates displaying distinct tropism upon virion-soluble receptor binding. Virology. 1995;69:6191–6198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6191-6198.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tremblay M J, Fortin J F, Cantin R. The acquisition of host-encoded proteins by nascent HIV-1. Immunol Today. 1998;19:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trkola A, Pomales A B, Yuan H, Korber B, Maddon P J, Allaway G P, Katinger III H, Barbas C F, Burton D R, Ho D D, Moore J P. Cross-clade neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by human monoclonal antibodies and tetrameric CD4-IgG. J Virol. 1995;69:6609–6617. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6609-6617.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley J M, Olson W C, Allaway G P, Cheng-Meyer C, Robinson J, Maddon P J, Moore J P. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its coreceptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ugolini S, Mondor I, Parren P W H I, Burton D R, Tilley S A, Klasse P J, Sattentau Q J. Inhibition of virus attachment to CD4+ target cells is a major mechanism of T cell line-adapted HIV-1 neutralization. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1287–1298. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valenzuela A, Blanco J, Krust B, Franco R, Hovanessian A G. Neutralization antibodies against the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 block the CD4-dependent and -independent binding of virus to cells. J Virol. 1997;71:8289–8298. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8289-8298.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vancott T C, Bethke F R, Burke D S, Redfield R R, Birx D L. Lack of induction of antibodies specific for conserved, discontinuous epitopes of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins by candidate AIDS vaccines. J Immunol. 1995;155:4100–4110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vancott T C, Polonis V R, Loomis L D, Michael N L, Nara P L, Birx D L. Differential role of V3-specific antibodies in neutralization assays involving primary and laboratory-adapted isolates of HIV type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:1379–1391. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vujcic L K, Quinnan G V. Preparation and characterization of human HIV type 1 neutralizing reference sera. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:783–787. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induces interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoprotein with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wyatt R, Kwong P D, Desjardins E, Sweet R W, Robinson J, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J G. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]