Summary

Addressing disparities is crucial for enhancing population health, ensuring health security, and fostering resilient health systems. Disparities in acute care surgery (trauma, emergency general surgery, and surgical critical care) have been well documented and the magnitude of inequities demand an intentional, organized, and effective response. As part of its commitment to achieve high-quality, equitable care in all aspects of acute care surgery, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma convened an expert panel at its eigty-second annual meeting in September 2023 to discuss how to take action to work towards health equity in acute care surgery practice. The panel discussion framed contemporary disparities in the context of historic and political injustices, then identified targets for interventions and potential action items in health system structure, health policy, the surgical workforce, institutional operations and quality efforts. We offer a four-pronged approach to address health inequities: identify, reduce, eliminate, and heal disparities, with the goal of building a healthcare system that achieves equity and justice for all.

Keywords: Healthcare disparities, Multiple Trauma, general surgery

Introduction

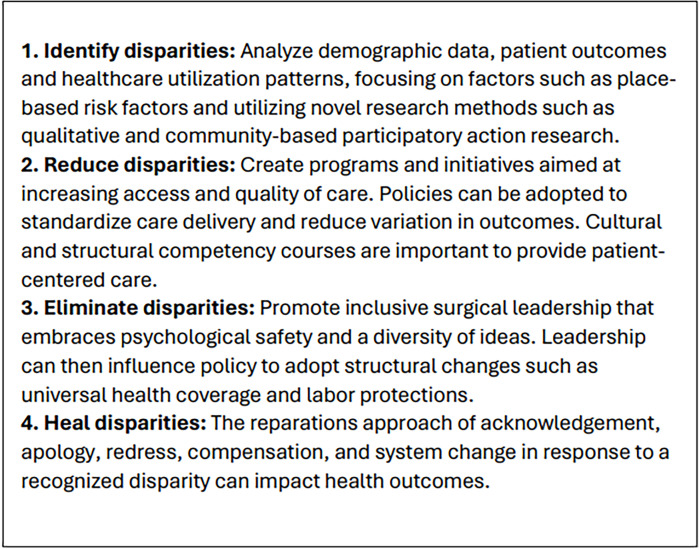

Surgical disparities manifest in diverse populations' access to, availability, and quality of surgical care and are significantly influenced by race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and geographic location.1,3 As part of its commitment to achieve high-quality, equitable care in all aspects of acute care surgery, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) convened an expert panel at its eighty-second annual meeting in September 2023 (Anaheim, California) to discuss how to take action to work towards health equity in acute care surgery practice. This panel discussion was a follow-up to prior work introducing the concept of ‘quality care as equitable care’ within acute care surgery.4 The objective of this discussion was to frame contemporary disparities in the context of historic and political injustices, then identify targets for interventions and potential action items in health system structure, health policy, the surgical workforce, institutional operations, and quality efforts. We invite readers to consider a four-pronged approach to addressing surgical disparities as they read each section: ‘Identify disparities, Reduce disparities, Eliminate disparities, and Heal disparities’ (figure 1).

Figure 1. The four-pronged approach to identify, reduce, eliminate, and heal surgical disparities.

Historical and political context

Understanding the complex historical roots and systemic barriers that perpetuate societal inequalities in the USA is necessary for repairing and fostering resilient and equitable health systems. The legacies of settler-colonial violence, slavery, racial capitalism and systemic racism have deeply affected the Indigenous and African American populations, both of which disproportionately experience poor health outcomes and reduced life expectancy.5,10 Forced displacement and cultural assimilation policies (the Dawes and Indian Civilization Acts, respectively) rapidly erased indigenous populations for land accumulation, and chattel slavery and the ‘one-drop-rule’ (of African blood) expanded the pool of exploitable human beings governed by state-sanctioned violence.10 11 The historic trauma derived from these policies as well as persistent patterns of physical, sexual, and psychological violence, have led to an increased allostatic load, chronic health issues, and disparities in surgical outcomes among Indigenous peoples and African Americans and become foundational for the structural racism and racial capitalism of today.612,14

The ongoing policies of systemic racist exclusion, from Jim Crow Laws to redlining, further contribute to the racial wealth gap, surgical disparities, and preventable mortality. This gap is primarily ascribed to limited access to postsecondary education and homeownership for African American and Latinx families; however, many marginalized groups and individuals with overlapping, intersectional identities have also faced exclusion from health insurance policies, further impacting their access to basic healthcare .15 It is estimated that 74 000 African Americans die prematurely each year due to systemic racism.16 17

Acknowledging and addressing the profound healthcare disparities that have disproportionately affected marginalized communities are critical steps towards healing and achieving equity in healthcare. Healing through reparations plays a pivotal role in this process by offering redress for historical injustices, eliminating wealth gaps linked to structural racism and enhancing the health and economic well-being of affected populations.18 19 Legal advocacy with medical-legal partnerships represent a novel approach by blending healthcare and legal advocacy to address structural determinants directly impacting patient health, eliminating surgical disparities.20,22 Ultimately, a multifaceted approach involving reparations, policy changes, education, and systemic reforms with legal advocacy is crucial for healing the wounds of historical injustices and building a healthcare system that promotes equity and justice for all.

Health system targets and strategies to advance health equity in acute care surgery

Due to the time-sensitive nature of acute care surgery, geographic health system structure is a fundamental determinant of access to care. Unfortunately, geographic access to emergency surgical care in the USA is inequitable, with distribution and capacity of hospitals not aligned with population needs.23 Minoritized, low-income and rural populations disproportionately face structural barriers in accessing emergency surgical care.23 24 Proposed contributors to these disparities include the outsized influence of economic forces in the healthcare environment which has prompted hospital closures in underserved neighborhoods despite demonstrated need, and the challenges of adapting the built healthcare environment to population shifts.25,29 We offer three key targets for intervention to improve equity in health systems for acute care surgery.

1. Prehospital care

The prehospital system plays a critical role in patient care. Beyond the initial resuscitation and transport of critically ill and injured patients, prehospital transport has important downstream effects on patients, including determining the location and availability of resources at the initial hospital and the quality of care the patient will receive. Unfortunately, studies have shown differences in ED destination for critically injured trauma patients on the basis of sex and race/ethnicity.30 31 Structural barriers to care, including increasing ED closures and frequency of ambulance diversion also disproportionately affect minoritized communities, increasing prehospital time to definitive care.32 There remains a pressing need to understand the mechanisms through which structural discrimination in trauma and health system structure affects prehospital care processes to design effective interventions to correct these inequities.

2. Interhospital transfers

Interhospital transfers (IHTs) are a critical mechanism through which patients who initially present at smaller community and non-trauma centers access life-saving specialized resources at tertiary institutions, including level-1 trauma centers. Despite policies like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act and trauma triage guidelines intended to standardize care and ensure patients are transferred to appropriate institutions, IHT is not applied equally. In trauma, severely injured patients who are privately insured have repeatedly been shown to have a lower likelihood of transfer to a trauma center.33 34 Proposed reasons for this include potential financial benefits to the index hospital for reimbursement of substantial charges associated with complex multitrauma admissions (and conversely the risk of non-reimbursement for admitting uninsured or publicly insured patients), as well as the role of patient preference. In contrast, racial and ethnic disparities have been more prominent in the emergency general surgery (EGS) population, where minoritized patients with complex EGS disease experience lower odds of transfer from community to tertiary hospitals.35 The factors underlying the differences in IHT patterns between the two populations has not yet been directly examined, however billing practices, reimbursement policies, availability of specialized services, and patient/caregiver preferences may play a role.34 36 Opportunities for improving equity within the IHT system include (A) developing state-level transfer coordination centers or regional medical operation centers with standardized pathways and protocols for resource utilization,37 (B) ensuring representation from minority-serving, Indigenous, and rural hospitals in groups leading health system planning at the state and interstate levels,38 and (C) examination of equity as a key metric of IHT performance.

3. Regional health systems

Addressing the role of structural barriers in access to emergency surgical care will require evaluating system structure and performance with a broader, equity-focused lens. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma has led the way in the development of regional systems for trauma care; however, opportunities exist to expand this model to non-traumatic surgical emergencies. First, we must assess and track equity in population outcomes for trauma and EGS patients across regions, and not only within individual hospitals. Further, inherent to the concept of a regional system is that all components work together to ensure high-quality care and equitable outcomes for the entire population in the region. To accomplish this, states should consider adopting policies that incentivize cooperation and communication among hospitals, and use disaggregated data to ensure high-quality outcomes for rural, minoritized, and low-income populations.39

Health policy strategies to advance health equity among acute care surgery patients

There are numerous policy opportunities at both the in-hospital and postdischarge phases of care to impact patients’ health trajectories and improve health equity. Central to policy considerations surrounding equity is the concept of equitable access to care that encompasses the entire care continuum from prehospital through acute and postdischarge care. We must consider not only patients’ in-hospital clinical recoveries, but also their trajectories after discharge. Action-oriented health strategies to advance health equity should incorporate patients’ longitudinal trajectories through the healthcare system.

1. Leverage in-hospital opportunities to help patients improve health access

Whereas much work in this area remains to be done, there are policies and programs that already exist and are aimed at improving equity in healthcare access. One such program is an in-hospital Emergency Medicaid program, called Hospital Presumptive Eligibility (or HPE), whereby uninsured patients who become emergently ill can be screened and qualify for Medicaid coverage which will help to both alleviate the financial burden of costs of care and increase access to any needed postdischarge services (eg, rehabilitation, home health, mental healthcare services.)40 Knowlton et al demonstrated that nearly 70% of patients enrolled in HPE at the time of hospitalization are successful in sustaining Medicaid insurance coverage in that year.41 The successful implementation of this program critically relies on hospital personnel such as financial counselors, social workers, and case managers who play an important role in educating patients and, in many instances, advocating for their successful enrollment. It is imperative for surgeons and physicians to understand the potential of these and other such programs and take an active role in such education.

2. Mandate improved tracking of patient-reported outcomes postdischarge and integrate into health equity reporting metrics

Prioritization of accurate capture and reporting of equity metrics within organizations is imperative. This should also be aimed at better capturing longitudinal patient data including patient-reported outcomes that reflect patient experience. This requires additional qualitative research to understand the true barriers in access and equity that patients experience, to better capture risk factors. For example, long-term functional and patient-reported quality of life and financial outcomes are now being incorporated in certain local trauma registries (eg, work from the Functional Outcomes and Recovery after Trauma Emergencies [FORTE] project).42 These include considerations such as sociodemographic barriers, food insecurity, medical debt, and the financial impact of healthcare.43 The target would be to incorporate these equity metrics at the institutional level, and to have them integrate with larger national data sets for tracking and comparative analysis of longitudinal outcomes across health systems.

3. Engage and leverage local communities to facilitate prehospital and postdischarge transition

Finally, beyond the hospital, understanding a patient’s community is central to designing high-quality surgical systems capable of meeting their needs. Health equity driven policy should be driven not only by institutional leadership and staff, but also by engaging community resources to increase the likelihood of success of any intervention posthospital discharge. Individual and community-based patient education can be implemented through outpatient case managers/social workers who interface with trusted community health workers to improve resources and access.

Equity in workforce and leadership

There is a clear need to increase diversity in healthcare and surgery, with evidence supporting benefits to patients including improved access to care, better communication, and enhanced patient-centered care and decision making.39,43 Structural racism and discrimination is pervasive in the US healthcare system—including academic medicine—with wide-ranging impact on medical school admissions, through residency training programs and faculty career progression.6 44 45 From the influence of implicit biases in faculty evaluations and selection processes, to unequal access to mentorship, professional networks and opportunities that are crucial for career development and advancement, structural discrimination has a profound effect on who is welcomed into the surgical profession, and who leads our community.46 During the past 5 years, numerous national surgical organizations including the American Surgical Association, the AAST and the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) have evaluated the current state of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in our profession, as well as strategies to improve in each of these domains.

In 2020, Tseng et al in the EAST Equity, Quality and Inclusion in Trauma Surgery Practice Ad Hoc Committee published the first large-scale survey of acute care surgeons that examined the demographics of the workforce and incidence of exclusionary behaviors witnessed. As expected, the majority of respondents identified as white/non-Hispanic (71%), male (60%), and heterosexual (87%).47 Underrepresentation of women was further found to extend to leadership in acute care surgery professional organizations including committee chairs and executive leadership from all three major organizations (AAST, EAST, and Western Trauma Association).48

Inequities have also been identified in career progression for academic surgeons. In examining surgical residents, Haruno et al found that black/African American residents were noted to be at ‘disproportionate risk for attrition and unintended attrition compared with all other residents’.49 In a broader evaluation of academic surgery leadership (not exclusive to acute care surgery) using census data from the Association of American Medical Colleges faculty roster, Riner et al found the ‘greatest magnitude of underrepresentation along the surgical pipeline has been among Black and Hispanic/Latinx full professors’.50 Improving diversity in our profession will therefore require critical evaluation of the barriers to progression at each step of the training and career pathway.

Surveys of trainees and practicing surgeons have also raised alarm regarding the prevalence of biased and discriminatory behavior. In the aforementioned 2020 EAST Survey, perceptions of bias in the workplace were prevalent, with approximately half of female respondents and surgeons of color having respectively experienced or witnessed sexual or racial/ethnic discrimination in the prior year.47 A 2019 survey of surgical residents found discrimination, sexual harassment and bullying were all more common in LGBTQ+ residents.51 Education regarding the types of behavior that constitute discrimination and bullying, and bystander training to provide surgeons with ways to intervene is essential to create a safe and supportive work environment for all.

The AAST DEI committee has published a conversation with discrete actions that can begin to combat many of the these inequities. Taking a data-driven approach to equity, bias training, support for those doing equity work, sponsoring underrepresented groups and individuals, committing funding to the initiatives, and being intentional are among some actions mentioned.52 Overall, focusing on the progression of individuals from undergraduate education to medical school, surgical residency, and their choice of career seems to be an area ripe for intervention. Ensuring equitable treatment of the acute care surgery community and maintaining focus in this arena should help recruit individuals that will ensure our profession more accurately mirrors the patients we treat.

Equity in quality standards

Hospitals are held to quality standards from a variety of accrediting organizations, including the Joint Commission, Det Norske Veritas, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). In surgery, the ACS has a long-standing history of setting standards to optimize patient safety and quality, as well as a number of verification programs including the Emergency General Surgery Verification Program and the Trauma Verification, Review, and Consultation Program.

Modest evidence exists to support improved quality of care with compliance and accreditation standards.53 As data mount regarding continued inequities in surgical care and healthcare overall, there are increasing efforts to incorporate equity metrics into quality programs. For example, in 2022, CMS released their framework for health equity, designed to guide their efforts for reducing inequities through 2032.54 However, there needs to be a balance between implementing comprehensive measures to drive improvement and overburdening clinicians and hospitals with regulatory requirements. In consideration of this tension, CMS has proposed a Universal Foundation, or core measure set, to streamline and align measures.55 The Universal Foundation aims not only to focus quality efforts on measures that pertain to broad segments of the population but also to advance equity.

Data from the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, as an example, support the adage that ‘What gets measured, gets improved’.56 Despite the importance of measurement, there remains a lack of infrastructure for standardized collection of variables to evaluate equity across populations using stratified analyses—that is, race, ethnicity, and language, and sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data.57 Furthermore, although CMS has implemented measures around screening for social determinants of health (SDOH), there remains a lack of consensus on how to measure SDOH or the impact of SDOH interventions on patient outcomes.58 59

Research also suggests that measurement, although necessary, is not sufficient in itself to improve outcomes.60,62 Strategies must be developed to address identified inequities and analyze if those strategies are effective.57 The latter is especially important in the setting of increased expenditures by multiple stakeholders, including CMS and industry, to address SDOHs.58 Rudy et al suggest that measures to evaluate SDOH interventions should: (A) Use validated proxy measures, (B) Be feasibly implemented and measured, (C) Be easily understood and applied longitudinally for comparison across different entities, and (D) Measure the range of patient perspectives.59

In summary, organizations are increasingly developing and promoting frameworks for health equity to guide improvement efforts.54 63 64 These frameworks form the basis for measures and standards that can help to obtain provider and hospital buy-in and accountability. As with quality improvement in general, reducing disparities will require all stakeholders to work together, from the leadership to the frontline provider, and to incorporate principles of equity into all of their patient care activities.

Advancing health equity within your institution

Ensuring timely, safe, and effective surgical care is paramount for major academic centers, and careful attention to quality and safety performance measures is vital to delivering the best patient outcomes. The New York University Langone Hospital (NYULH) has been a leader in the integration of health equity in quality metrics to ensure that equitable care is provided across the healthcare system. The following three principles have been fundamental to achieving this goal in the NYULH academic health system.

-

Decide on the governance of health equity.

The institution must analyze who will lead the advancement of health equity work. This can be the chief quality officer, chief health equity officer, or a population health expert.

-

Design a process to disaggregate your race and ethnicity data and other demographic data.

Existing disparities are hidden when broad racial and ethnic categories and smaller demographics are not included.65 The lack of accurate and comprehensive data on marginalized populations limits our understanding of and ability to address disparities.66

Understanding which populations are currently being collected and how complete your data sets are is essential. Next, evaluate how the information is presently being collected. Who collects this information from the patient? How much demographic information is collected through the electronic medical record? How is this being messaged to your patients?

-

Development of data transparency and visualization.

Once the level of disaggregation has been established, it is essential to develop a mechanism by which access to the disaggregated data is available to members of the health system. Standardized tools for reporting of sex, gender, race, ethnicity have been proposed for health research in surgery.67 68 Policies requiring collection of SOGI and SDOH will help facilitate organization and dissemination of this data.54 69

Dashboards have been widely utilized in the NYULH health system to review quality metrics. As the disaggregation of race and ethnicity categories was underway, the design of a clinical health equity dashboard was implemented to allow the hospital leadership, department chairs, quality officers, and other stakeholders to review the dashboard, look for signals, and design processes to reduce disparities in care.

By making health equity a priority and integrating equity into an institution’s quality and safety performance improvement plan, health equity becomes integrated into the culture of the institution. This furthers our mission to improve quality and safety across the care continuum.

Conclusion

Addressing disparities is crucial for enhancing population health, ensuring health security, and fostering resilient health systems. Identifying, reducing, eliminating, and healing disparities represent a comprehensive approach to surgical disparities (figure 1). Although increasing efforts are being made to identify and reduce disparities, opportunities still exist for expansion of equity metrics to include long-term patient-oriented data and for incorporation of equity metrics into hospital accreditation standards. Further attention must be focused on eliminating and healing disparities, both of which require leadership commitment, health system re-design, and policy-level change. Stakeholders at all levels, including national organizations such as the AAST, need to be engaged and aligned to advance health equity.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Marta L McCrum, Email: marta.mccrum@hsc.utah.edu.

Tanya L Zakrison, Email: tzakrison@bsd.uchicago.edu.

Lisa Marie Knowlton, Email: drlmk@stanford.edu.

Brandon Bruns, Email: Brandon.Bruns@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Lillian S Kao, Email: lillian.s.kao@uth.tmc.edu.

Kathie-Ann Joseph, Email: Kathie-ann.joseph@nyulangone.org.

Cherisse Berry, Email: cherisse.berry@nyulangone.org.

References

- 1.Haider AH, Chang DC, Efron DT, Haut ER, Crandall M, Cornwell EE. Race and Insurance Status as Risk Factors for Trauma Mortality. Arch Surg . 2008;143:945. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haider AH, Weygandt PL, Bentley JM, Monn MF, Rehman KA, Zarzaur BL, Crandall ML, Cornwell EE, Cooper LA. Disparities in trauma care and outcomes in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1195–205. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828c331d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowlton LM, Harris AHS, Tennakoon L, Hawn MT, Spain DA, Staudenmayer KL. Interhospital variability in time to discharge to rehabilitation among insured trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86:406–14. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowlton LM, Zakrison T, Kao LS, McCrum ML, Agarwal S, Jr, Bruns B, Joseph K-A, Berry C. Quality care is equitable care: a call to action to link quality to achieving health equity within acute care surgery. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open . 2023;8:e001098. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2023-001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenhauer J, Christensen EF, Mainz J, Valentin JB, Foss NB, Svenningsen PO, Johnsen SP. Disparities in prehospital and emergency surgical care among patients with perforated ulcers and a history of mental illness: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg . 2024;50:975–85. doi: 10.1007/s00068-023-02427-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet . 2017;389:1453–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowker SL, Williams K, Volk A, Auger L, Lafontaine A, Dumont P, Wingert A, Davis A, Bialy L, Wright E, et al. Incidence and outcomes of critical illness in Indigenous peoples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care . 2023;27:285. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livergant RJ, Fraulin G, Stefanyk K, Binda C, Maleki S, Joharifard S, Hillier T, Joos E. Postoperative morbidity and mortality in pediatric indigenous populations: a scoping review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2023;39:129. doi: 10.1007/s00383-023-05377-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McVicar JA, Poon A, Caron NR, Bould MD, Nickerson JW, Ahmad N, Kimmaliardjuk DM, Sheffield C, Champion C, McIsaac DI. Postoperative outcomes for Indigenous Peoples in Canada: a systematic review. CMAJ . 2021;193:E713–22. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abella M, Lee AY, Kitamura RK, Ahn HJ, Woo RK. Disparities and Risk Factors for Surgical Complication in American Indians and Native Hawaiians. J Surg Res. 2023;288:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2023.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreiro AE. One drop of blood: the American misadventure of race. [Review of: Malcomson, S.L. One drop of blood: the American misadventure of race. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000] Chron Okla. 2000;79:501–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duru OK, Harawa NT, Kermah D, Norris KC. Allostatic load burden and racial disparities in mortality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30120-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Dyke ME, Baumhofer NK, Slopen N, Mujahid MS, Clark CR, Williams DR, Lewis TT. Pervasive Discrimination and Allostatic Load in African American and White Adults. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:316–23. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shadlow JO, Kell PA, Toledo TA, Huber FA, Kuhn BL, Lannon EW, Hellman N, Sturycz CA, Ross EN, Rhudy JL. Sleep Buffers the Effect of Discrimination on Cardiometabolic Allostatic Load in Native Americans: Results from the Oklahoma Study of Native American Pain Risk. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:1632–47. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boston FRB of The color of wealth in boston. [10-Mar-2024]. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/one-time-pubs/color-of-wealth.aspx Available. Accessed.

- 16.Benjamins MR, Silva A, Saiyed NS, De Maio FG. Comparison of All-Cause Mortality Rates and Inequities Between Black and White Populations Across the 30 Most Populous US Cities. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2032086. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards F, Lee H, Esposito M. Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race-ethnicity, and sex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:16793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821204116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassett MT, Galea S. Reparations as a Public Health Priority - A Strategy for Ending Black-White Health Disparities. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2101–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2026170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Himmelstein KEW, Lawrence JA, Jahn JL, Ceasar JN, Morse M, Bassett MT, Wispelwey BP, Darity WA, Jr, Venkataramani AS. Association Between Racial Wealth Inequities and Racial Disparities in Longevity Among US Adults and Role of Reparations Payments, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2240519. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alur R, Hall E, Smith MJ, Zakrison T, Loughran C, Cosey-Gay F, Kaufman EJ. What medical-legal partnerships can do for trauma patients and trauma care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024;96:340–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall EC, Current JJ, Sava JA, Rosen JE. The Case for Integrating Medical-Legal Partnerships Into Trauma Care. J Surg Res. 2022;274:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2021.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evaluating the impact of medical-legal partnerships on health and health inequities. [9-Apr-2022]. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-research/health-equity/medical-legal-partnerships Available. Accessed.

- 23.McCrum ML, Wan N, Han J, Lizotte SL, Horns JJ. Disparities in Spatial Access to Emergency Surgical Services in the US. JAMA Health Forum . 2022;3:e223633. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarman MP, Castillo RC, Carlini AR, Kodadek LM, Haider AH. Rural risk: Geographic disparities in trauma mortality. Surgery. 2016;160:1551–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsia RY, Zagorov S. Structural Discrimination in Emergency Care: How a Sick System Affects Us All. Med . 2022;3:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsia RY, Kellermann AL, Shen YC. Factors associated with closures of emergency departments in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:1978–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen YC, Hsia RY, Kuzma K. Understanding the risk factors of trauma center closures: do financial pressure and community characteristics matter? Med Care. 2009;47:968–78. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsia RYJ, Shen YC. Rising closures of hospital trauma centers disproportionately burden vulnerable populations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1912–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz A, Schoenbrunner A, Pawlik TM. Trends in the Geospatial Distribution of Inpatient Adult Surgical Services across the United States. Ann Surg. 2021;273:121–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanchate AD, Paasche-Orlow MK, Baker WE, Lin MY, Banerjee S, Feldman J. Association of Race/Ethnicity With Emergency Department Destination of Emergency Medical Services Transport. JAMA Netw Open . 2019;2:e1910816. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escobar N, DiMaggio C, Frangos SG, Winchell RJ, Bukur M, Klein MJ, Krowsoski L, Tandon M, Berry C. Disparity in Transport of Critically Injured Patients to Trauma Centers: Analysis of the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235:78–85. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsia RY, Sarkar N, Shen YC. Impact Of Ambulance Diversion: Black Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Had Higher Mortality Than Whites. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1070–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zogg CK, Schuster KM, Maung AA, Davis KA. Insurance Status Biases Trauma-system Utilization and Appropriate Interfacility Transfer: National and Longitudinal Results of Adult, Pediatric, and Older Adult Patients. Ann Surg. 2018;268:681–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delgado MK, Yokell MA, Staudenmayer KL, Spain DA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wang NE. Factors associated with the disposition of severely injured patients initially seen at non–trauma center emergency departments: disparities by insurance status. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:422–30. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iantorno SE, Bucher BT, Horns JJ, McCrum ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in interhospital transfer for complex emergency general surgical disease across the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94:371–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz MH, Wei EK. EMTALA-A Noble Policy That Needs Improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:693–4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epley EE, Stewart RM, Love P, Jenkins D, Siegworth GM, Baskin TW, Flaherty S, Cocke R. A regional medical operations center improves disaster response and inter-hospital trauma transfers. Am J Surg. 2006;192:853–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartlett E, Greenwood-Ericksen M. Indigenous Health Inequities Arising From Inadequate Transfer Systems for Patients With Critical Illness. JAMA Health Forum . 2022;3:e223820. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carr BG, Kilaru AS, Karp DN, Delgado MK, Wiebe DJ. Quality Through Coopetition: An Empiric Approach to Measure Population Outcomes for Emergency Care-Sensitive Conditions. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72:237–45. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knowlton LM, Tran LD, Arnow K, Trickey AW, Morris AM, Spain DA, Wagner TH. Emergency Medicaid programs may be an effective means of providing sustained insurance among trauma patients: A statewide longitudinal analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94:53–60. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knowlton LM, Logan DS, Arnow K, Hendricks WD, Gibson AB, Tran LD, Wagner TH, Morris AM. Do hospital-based emergency Medicaid programs benefit trauma centers? A mixed-methods analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg . 2024;96:44–53. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rios-Diaz AJ, Herrera-Escobar JP, Lilley EJ, Appelson JR, Gabbe B, Brasel K, deRoon-Cassini T, Schneider EB, Kasotakis G, Kaafarani H, et al. Routine inclusion of long-term functional and patient-reported outcomes into trauma registries: The FORTE project. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:97–104. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haider AH, Herrera-Escobar JP, Al Rafai SS, Harlow AF, Apoj M, Nehra D, Kasotakis G, Brasel K, Kaafarani HMA, Velmahos G, et al. Factors Associated With Long-term Outcomes After Injury: Results of the Functional Outcomes and Recovery After Trauma Emergencies (FORTE) Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2020;271:1165–73. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lett E, Murdock HM, Orji WU, Aysola J, Sebro R. Trends in Racial/Ethnic Representation Among US Medical Students. JAMA Netw Open . 2019;2:e1910490. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shim RS. Dismantling Structural Racism in Academic Medicine: A Skeptical Optimism. Acad Med. 2020;95:1793–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kibbe MR. There Are Enough Qualified Women—Intentionality Overcomes Implicit Bias. JAMA Surg. 2024;4 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tseng ES, Zakrison TL, Williams B, Bernard AC, Martin MJ, Zebib L, Soklaridis S, Kaafarani HM, Zarzaur BL, Crandall M, et al. Perceptions of Equity and Inclusion in Acute Care Surgery: From the #EAST4ALL Survey. Ann Surg. 2020;272:906–10. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foster SM, Knight J, Velopulos CG, Bonne S, Joseph D, Santry H, Coleman JJ, Callcut RA. Gender distribution and leadership trends in trauma surgery societies. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open . 2020;5:e000433. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haruno LS, Chen X, Metzger M, Lin CA, Little MTM, Kanim LEA, Poon SC. Racial and Sex Disparities in Resident Attrition Among Surgical Subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:368–76. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.7640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riner AN, Herremans KM, Neal DW, Johnson-Mann C, Hughes SJ, McGuire KP, Upchurch GR, Jr, Trevino JG. Diversification of Academic Surgery, Its Leadership, and the Importance of Intersectionality. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:748–56. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heiderscheit EA, Schlick CJR, Ellis RJ, Cheung EO, Irizarry D, Amortegui D, Eng J, Sosa JA, Hoyt DB, Buyske J, et al. Experiences of LGBTQ+ Residents in US General Surgery Training Programs. JAMA Surg. 2022;157:23. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brasel K, Berry C, Williams BH, Henry SM, Upperman J, West MA. Lofty goals and strategic plans are not enough to achieve and maintain a diverse workforce: an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee conversation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open . 2021;6:e000813. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2021-000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hussein M, Pavlova M, Ghalwash M, Groot W. The impact of hospital accreditation on the quality of healthcare: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1057. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07097-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McIver DL. CMS Framework for Health Equity 2022–2032

- 55.Jacobs DB, Schreiber M, Seshamani M, Tsai D, Fowler E, Fleisher LA. Aligning Quality Measures across CMS — The Universal Foundation. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:776–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2215539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hall BL, Hamilton BH, Richards K, Bilimoria KY, Cohen ME, Ko CY. Does surgical quality improve in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: an evaluation of all participating hospitals. Ann Surg. 2009;250:363–76. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4148f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bailit M, Kanneganti D. A Typology For Health Equity Measures. Health Aff Forefr. doi: 10.1377/forefront.20220318.155498. n.d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goldberg ZN, Nash DB. For Profit, but Socially Determined: The Rise of the SDOH Industry. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25:392–8. doi: 10.1089/pop.2021.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rudy ET, McNamara KC, Goldberg ZN, Parker A, Nash DB. A Call for Consistent Measurement Across the Social Determinants of Health Industry Landscape. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25:698–701. doi: 10.1089/pop.2022.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berwick DM. Measuring Surgical Outcomes for Improvement. JAMA. 2015;313:469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Etzioni DA, Wasif N, Dueck AC, Cima RR, Hohmann SF, Naessens JM, Mathur AK, Habermann EB. Association of hospital participation in a surgical outcomes monitoring program with inpatient complications and mortality. JAMA. 2015;313:505–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osborne NH, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Association of Hospital Participation in a Quality Reporting Program With Surgical Outcomes and Expenditures for Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA. 2015;313:496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin JS, Webber EM, Bean SI, Evans CV. Development of a Health Equity Framework for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA Netw Open . 2024;7:e241875. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Achieving health equity: a guide for health care organizations | institute for healthcare improvement. [5-Apr-2024]. https://www.ihi.org/resources/white-papers/achieving-health-equity-guide-health-care-organizations Available. Accessed.

- 65.Wilson B, Mendez J, Newman L, Lum S, Joseph KA. Addressing Data Aggregation and Data Inequity in Race and Ethnicity Reporting and the Impact on Breast Cancer Disparities. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:42–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-14432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kauh TJ, Read JG, Scheitler AJ. The Critical Role of Racial/Ethnic Data Disaggregation for Health Equity. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2021;40:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11113-020-09631-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stey AM, Ghneim M, Gurney O, Santos AP, Rattan R, Abahuje E, Baskaran A, Nahmias J, Richardson J, Zakrison TL, et al. Creation of standardized tools to evaluate reporting in health research: Population Reporting Of Gender, Race, Ethnicity & Sex (PROGRES) PLOS Glob Public Health . 2023;3:e0002227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nahmias J, Zakrison TL, Haut ER, et al. Call to Action on the Categorization of Sex,Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in Surgical Research. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:316–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Becker T, Chin M, Bates N, editors. measuring sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. National Academies Press (US); 2022. National academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine; division of behavioral and social sciences and education; committee on national statistics; committee on measuring sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]