Abstract

Background

The occurrence of suspended cords of the left atrium (SCLA) is rare and has seldom been described. The purpose of this study was to summarize the cases of SCLA accidentally detected by coronary CT angiography (CCTA), describe their imaging features, conduct a preliminary analysis of their clinical significance, and review relevant literature.

Methods

A total of 10,796 patients who underwent CCTA examinations from July 2020 to November 2021 were consecutively selected. The original and three-dimensional reconstruction images were reviewed to identify patients with SCLA. A control group was selected in a 1:2 ratio based on age, BMI, sex, and education level. The imaging characteristics and clinical data of the two groups were collected and compared. The case group was divided into two subgroups based on the starting and ending positions of the SCLA: Group 1 with the SCLA between the free wall and free wall, and Group 2 with the SCLA between the septum wall and free wall. The clinical features of these subgroups were compared. Furthermore, a review of literature on SCLA published in the past fifteen years that includes its clinical and imaging features was conducted.

Results

In this study, a total of 35 patients were found to have SCLA, resulting in an incidence rate of approximately 0.32%. After excluding 1 patient for whom clinical features could not be obtained, the case group included a total of 18 males and 16 females, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1 and a median age of 57.00 (52.00–64.00) years. It was found that 19 (55.88%) cases of SCLA were located near the right superior pulmonary vein ostia, while no SCLA was found near the left lower pulmonary vein orifice. A significant difference in the incidence of atrial arrhythmia between the two groups was observed (p = 0.009). Additionally, 3 patients (8.82%) in the SCLA group had a history of transient cerebral ischemic attack (TIA), which was significantly different from that in the control group (p = 0.035). The anteroposterior and transverse diameters of the left atrium were longer in the case group than in the control group (p < 0.05), but there was no significant change in left atrial volume. Subgroup analyses found no significant difference in the incidence of cerebral infarction, atrial arrhythmia, or other intracardiac structural malformations, although there was a significant difference in cord length (p = 0.013), with the length of SCLA in Group 1 and Group 2 being 2.64 ± 0.99 cm and 3.39 ± 0.68 cm, respectively. Notably, only 1 of these 34 patients was diagnosed based on echocardiography, whereas all cases were perfectly visualized using CCTA.

Conclusion

SCLA is rare. CCTA can accurately detect and depict this abnormal structure as compared to echocardiography. SCLA may be linked to a higher incidence of atrial arrhythmias or transient ischemic attacks. It is important for radiologists and cardiovascular experts to recognize this structure, and further investigation is necessary to determine its clinical significance.

Keywords: Suspended cord of left atrium, Coronary CT angiography, Atrial arrhythmias, Transient cerebral ischemia

Introduction

The presence of a suspended cord in the left atrium (SCLA) is a rare but clinically significant finding. SCLA was initially reported in 1897 [1], and autopsy data indicated its occurrence in approximately 2% of patients [2]. So far, reports on SCLA have been limited and mostly comprised of echocardiography case reports or autopsy data. However, the presentation of SCLA in cadaver specimens may differ from that in living individuals, and the existing ultrasound literature is also limited, lacking clear three-dimensional images to facilitate better understanding of this structure. The pattern of SCLA occurrence and its relationship with the pulmonary vein, left atrial appendage, and mitral valve remains unclear. With the widespread use of multirow helical CT and the extensive development of electro-cardio-gated (ECG) cardiac scanning technology, high-spatial-resolution thin-layer heart images are now readily available. By capturing images while the heart is at rest, the depiction of the heart’s intricate structure is exceptionally clear and closely reflects its living state. Our extensive patient population and advanced spiral CT equipment have enabled us to systematically collect and summarize the imaging features of this rare structure and its clinical significance. Simultaneously, relevant literature was systematically searched and summarized to enhance our understanding of the structure and its clinical significance.

Methods

Study population and clinical information collection

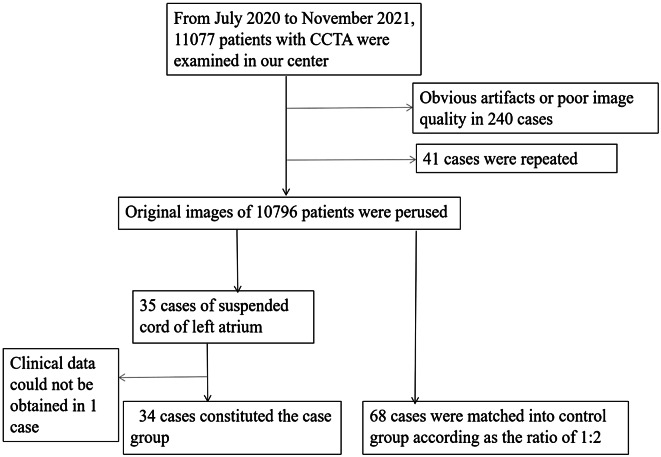

The picture archiving and communication system was retrospectively accessed, and all patients who underwent CCTA examinations at our institution from July 2020 to November 2021 were consecutively enrolled. Images containing more pronounced respiratory motion or pulsation artifacts that interfered with observation were excluded. For patients with multiple examinations, the one with the best image quality was selected for observation. Patients with SCLA (see Sect. 1.3 below for relevant definitions) were screened to form a case group. A control group was established in the same CCTA examination group according to the sex, age, BMI, and education of the enrolled observers according to the 1:2 matching principle, and information on the imaging and some available clinical characteristics of the control group was collected at the same time (Fig. 1). The study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution (approval number: 2022-R089), and informed consent was waived. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study

Clinical information was collected mainly by logging into the hospital inpatient electronic medical record system and outpatient electronic medical record system as well as by telephone interview, focusing on the following aspects: (1) arrhythmias, including persistent atrial fibrillation, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, premature atrial beats, and other arrhythmias; (2) heart valve status, especially the presence or absence and degree of mitral stenosis or insufficiency; (3) history of previous embolism in the body circulation, including TIA, parenchymal organ embolism, such as those of the spleen and kidney, and the presence or absence of myocardial infarction; (4) if the patient had a history of left atrial intervention, concomitant procedural disorders were recorded.

Instrumentation and scanning plan

A Philips 256-layer spiral CT scanner (Brilliance 256 iCT, Philips Health Care, The Netherlands) was utilized to conduct the examination following the CCTA scanning protocol. Prior to the examination, heart rate variability was monitored. A prospective cardiac gated scanning protocol was implemented for patients with low heart rates (< 70 beats/min) and stable rhythms, while a retrospective cardiac gated scanning protocol was utilized for patients with fast heart rates (> 70 beats/min) or arrhythmias. All patients underwent respiratory training before the scan. Patients were positioned in the supine position, and a nonionic contrast agent, iohexol (350 mg/ml, 0.8 ml/kg), was administered intravenously using a double-barrel high-pressure syringe. The flow volume and flow rate were adjusted based on the patient’s weight and vascular condition, and the contrast concentration tracking technique was employed to detect CT values at the level of the aortic root by selecting the area of interest, triggered at more than 110 HU, from 0.5 cm below the tracheal bifurcation to the diaphragmatic surface of the heart scanning. The scan parameters were set as follows: tube voltage 120 kV, tube current 600–800 mAs/revolution, collimation 128 × 0.625, matrix 512 × 512, pitch 0.18, rotation time 330 ms, and scan field 250 mm. All scans were conducted in the automatic tube current adjustment mode during the cardiac cycle to minimize radiation exposure.

Image analysis and measurement

All raw images and post-processed CCTA visualization images were transferred to the PACS system. The syngo. viaVB20 (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) workstation was used to perform multiplanar reconstruction (MPR), volume reconstruction (VR), and related feature evaluation and parameter measurement of the original image. The left atrial volume parameters were manually outlined and calculated using the area growth function. The following features were evaluated and documented when reading the image: left atrial diameter, left atrial volume, SCLA start and end point, length, relationship to the pulmonary venous ostia (near or away from), and the presence of other cardiac structural abnormalities, including atrial septal defects, patent foramen ovale, and atrial septal pouch.

Based on the spatial location of SCLA, the case groups were divided into two subgroups: an SCLA connecting the free wall and free wall (Group 1) and an SCLA connecting the septum wall and free wall (Group 2). The demographic characteristics, imaging features, and clinical features were compared between the two groups.

The relevant concepts and definitions are as follows: (1) SCLA definition: The starting and ending points of the cord in the left atrium are connected to different left atrial walls, and the suspending distance is at least 1 cm; (2) SCLA near the pulmonary vein ostia: At least one of the two endpoints is less than 2 cm away from the left atrial pulmonary vein ostia, and at least two perpendicular reference surfaces are needed to determine the left atrial pulmonary vein ostia; (3) Left atrium enlargement was defined as a left atrial anterior-posterior diameter above 4 cm [3].

After training by a senior cardiovascular radiologist with 20 years of work experience, all images were analyzed and evaluated by two researchers with more than 2 years of work experience. The two investigators were not aware of the patient’s clinical information. When the qualitative results were inconsistent, the final diagnosis was based on the judgment of the senior radiologist, and the mean of two quantitative indicators was taken as the final result.

Statistical analysis

Research data were manually entered into Excel. Statistical analyses were conducted using Empower Stats software (http://www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts). Continuous data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and the independent samples t-test was used to compare the two groups. Data not conforming to a normal distribution are presented as the median or interquartile range, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the two groups. Categorical data are expressed as frequencies or percentages, and differences between groups were assessed using the chi-square test. A p-value of < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference.

Results

After screening 10,796 consecutive patients who had undergone CCTA examination, 35 patients with SCLA were detected, corresponding to an incidence of 0.32%. One patient whose clinical data could not be obtained due to loss of contact was excluded, leaving 34 patients with a median age of 57.00 years (interquartile range: 52.00–64.00) included in the study. There were 18 males and 16 females, with no significant difference in incidence between genders (p = 0.992). These patients underwent CCTA for various reasons including arrhythmias, suspected coronary artery disease, chest tightness, hypertension, migraine, cerebral infarction, or routine physical examination. Among them, 14 patients underwent CCTA examination due to suspected coronary artery disease, which was the most common reason for consultation.

Data showed that the left atrial transverse diameter and anteroposterior diameter of the case group were larger than those of the control group, but there was no significant difference in volume between the two groups. In 31 cases (91.17%), SCLA was found close to the pulmonary vein orifice, while only 3 cases (8.82%) were far away from the pulmonary vein orifice. Among them, the SCLA near the right upper pulmonary vein orifice accounted for 55.88%, which was overwhelmingly dominant. No SCLA was found near the left inferior pulmonary vein ostia. There was a significant difference in the incidence of atrial arrhythmia between the two groups (p = 0.009), including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, persistent atrial fibrillation, and premature atrial contractions. Three patients in the SCAL group had a history of TIA, and the incidence of TIA was significantly different from that of the control group (p = 0.035) (Table 1). According to medical records of two patients with SCLA, the process of atrial fibrillation radiofrequency ablation surgery was disturbed by the cord. One patient had an embolization of the left circumflex branch of the coronary artery.

Table 1.

The demographic, anatomical, and clinical characteristics of the case and control groups

| Characteristics | Case groups | Control group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 34 | 68 | |

| Age (years, Q1-Q3) | 57.00(52.00–64.00) | 57.00(56.00–58.00) | 0.960 |

| Gender | 0.779 | ||

| Male | 18(52.94%) | 34(50.00%) | |

| Female | 16(47.06%) | 34(50.00%) | |

| BMI | 24.75(23.03–27.04) | 24.75(22.99–27.04) | 1.000 |

| Educational level (years) | 12.00(10.00–14.00) | 12.00(10.00–14.00) | 1.000 |

| Anterior-posterior diameter of LA (cm, SD) | 4.11(0.51) | 3.87(0.59) | 0.042 |

| Transverse diameter of LA (cm, SD) | 6.84(0.79) | 6.26(0.58) | < 0.001 |

| LA volume (cm3,Q1-Q3) | 78.24(62.85–92.84) | 72.19(60.95–82.53) | 0.184 |

| SCLA location | |||

| Near right superior pulmonary vein ostia | 19(55.88%) | ||

| Near right inferior pulmonary vein ostia | 3(8.82%) | ||

| Near left superior pulmonary vein ostia |

9(26.47%) 47) |

||

| Away from pulmonary vein ostia | 3(8.82%) | ||

| Atrial arrhythmias | 0.009 | ||

| None | 24(70.59%) | 64(94.12%) | |

| Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 3(8.82%) | 1(1.47%) | |

| Persistent atrial fibrillation | 2(5.88%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Premature atrial contractions | 5(14.71%) | 3(4.41%) | |

| Disorders of LA intervention operation | 2(5.88%) | 0(0.00%) | 0.109 |

| Mitral valve insufficiency | 4(11.76%) | 2(2.94%) | 0.094 |

| Cardiogenic embolism | 1(2.94%) | 0(0.00%) | 0.333 |

| Transient cerebral ischemic attack | 3(8.82%) | 0(0.00%) | 0.035 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1(1.47%) | 1 (1.47%) | 1.000 |

SCLA = suspended cord of the left atrium, LA = left atrium

The demographic, anatomical, and clinical features were compared between the two subgroups. It was found that there was no significant difference in the incidence of cerebral infarction, atrial arrhythmia, or other intracardiac structural malformations between the two subgroups, although there was a significant difference in cord length (p = 0.013), with the length of SCLA in group 1 and group 2 being 2.64 ± 0.99 cm and 3.39 ± 0.68 cm respectively. Another minor finding was that Group 1 included more male patients than Group 2, which bears unclear clinical significance at present (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with different locations of SCLA

| Free wall to free wall (Group 1) | Atrial septum to free wall (Group 2) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 18 | |

| Age (years, SD) | 58.00(11.49) | 57.17(8.21) | 0.808 |

| Gender | 0.015 | ||

| Female | 4(25.00%) | 12(66.67%) | |

| Male | 12(75.00%) | 6(33.33%) | |

| Length of SCLA (cm, SD) | 2.64(0.99) | 3.39(0.68) | 0.013 |

| Cerebral infarction | 3(18.75%) | 2(11.11%) | 0.648 |

| Atrial arrhythmias | 0.195 | ||

| None | 10 (62.50%) | 14 (77.78%) | |

| Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 2 (12.50%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Persistent atrial fibrillation | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Premature atrial contractions | 4 (25.00%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Combine other structure anomalies | |||

| Patent foramen ovale | 2 | 2 | |

| Atrial septal pouch | 5 | 9 | |

| Incomplete septum below the aortic valve | 0 | 1 | |

| Left atrial enlargement | 8 | 16 |

SCLA = suspended cord of the left atrium

Discussion

As far as we know, this work represents the largest sample-size observational study of SCLA based on helical CT to date. Being a rare structural abnormality, the incidence, imaging features, and clinical significance of SCLA have rarely been reported in the literature. This study screened a group of 34 SCLA patients from more than ten thousand patients who underwent CCTA examination at our hospital in the past two years. The incidence of this structure in this cohort was calculated, and the imaging characteristics were summarized. Furthermore, this study preliminarily discussed the clinical significance of this structure and provided a relatively large sample size observational study.

The relevant literature [2–16] in the past 15 years was reviewed, and the clinical features related to SCLA were summarized in Table 3. SCLA connecting the mitral valve, aortic ring, or even crossing the mitral opening to connect the ventricular septum were not found in this group, despite being reported in the literature. It is supposed that valve-related lesions may be preferentially detected by echocardiography, but the observation of the overall condition of the left atrium may be limited by the acoustic window and the surrounding structure. Although CCTA is better than echocardiography in identifying structural heart disease due to its high spatial resolution, unfortunately, there have been very few studies of CCTA on SCLA to date, which may limit the understanding of SCLA to some extent. More relevant research is needed to understand the reasons for this inconsistency.

Table 3.

Review and summary of SCLA literature in the last 15 years

| Authors | published Year | Patient age(years) | Gender | examination method |

SCLA Location | complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sherif et al. [4] | 2008 | 72 | female | Echocardiography |

dome-anterior leaflet of MV |

dyspnea, atrial fibrillation, mitral regurgitation |

| Irwin et al. [2] | 2011 | 75 | male |

Echocardiography, MRI |

roof wall-anterior leaflet of MV | mitral regurgitation |

| Shin et al. [5] | 2014 | 6 | male | Echocardiography |

atrial septum-MV orifice-ventricular septum |

|

| Kim et al. [6] | 2014 | 67 | male | Echocardiography | dome/atrial septum-anterior leaflet of MV | dyspnea, mitral regurgitation |

| Liou et al. [7] | 2014 | 44 | male | Echocardiography | near mitral annulus | unstable angina |

| Alsaid et al. [8] | 2016 | Echocardiography | atrial septum-MV | mitral valves prolapse, regurgitation | ||

| D’Onghia et al. [9] | 2018 | 85 | female | Echocardiography | anterior wall-MV | atrial fibrillation, mitral regurgitation |

| Hurtado-Sierra et al. [10] | 2018 | 10 | Echocardiography | atrial septum-MV | mitral valves prolapse, regurgitation | |

| Arroyo Rivera et al. [11] | 2019 | 70 | male | Echocardiography | roof wall-posterior leaflet of MV | atrial fibrillation, rheumatic mitral valve disease |

| Nnaoma et al. [12] | 2019 | 55 | male | Echocardiography | atrial septum-MV | mitral valves prolapse, regurgitation |

| Abe et al. [13] | 2020 | 79 | female |

Echocardiogram, CT |

atrial septum - left inferior pulmonary vein ostia | palpitation, atrial fibrillation |

| Vega et al. [14] | 2021 | 34 | male |

Echocardiography, MRI |

anterior wall-posterior leaflet of MV | chest tightness, mitral regurgitation |

| Omidi et al. [15] | 2021 | 27 | female | Echocardiography |

anterior wall-anterior leaflet of MV |

mitral valves prolapse, regurgitation, stroke |

| Ku et al. [16] | 2022 | 39 | female |

Echocardiography, CT |

atrial septum-left inferior pulmonary vein ostia | heart palpitations for 10 years |

MV = mitral valve

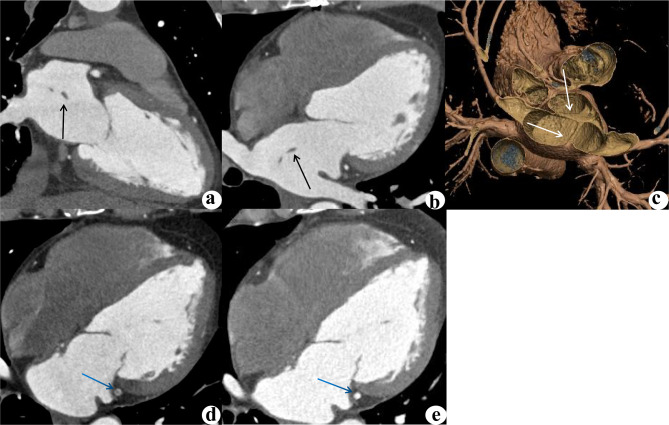

SCLA has been reported to be composed of fibrous muscle tissue [12], and the left atrium was speculated to be partially fused to the common pulmonary vein trunk, resulting in residual structural variation of the cord [17]. Due to the lack of acknowledgment, the exact incidence of SCLA in the population is unknown, and racial predispositions to SCLA have also yet to be identified. In this study, the incidence of SCLA was 0.32%, which was significantly lower than the 2% reported in previous autopsy data. The majority of the data in this study were obtained from suspected or confirmed coronary heart disease patients, and the incidence of cardiovascular-related clinical problems may consequently be higher in this dataset than in general autopsy data. Therefore, the incidence rate of 2% reported in the past may be overestimated, while the incidence rate of 0.32% in this study is closer to the real population incidence. In the past, most SCLA cases were discovered by autopsy, and the medical history was then retrospectively analyzed and evaluated. Under the circumstances tracing SCLA and its impact on living bodies was difficult. This study suggested that atrial arrhythmias and transient cerebral ischemia were more likely to occur in the SCLA group; the incidence rates of these conditions significantly differed from those in the control group. One SCLA patient exhibited concomitant embolization of the left circumflex branch of the coronary artery (Fig. 2), suggesting that this structure is associated with systemic embolization that cannot be ignored.

Fig. 2.

A 46-year-old male, who was admitted to the hospital with chest tightness and chest pain for more than 20 days, which worsened for 4 days. The SCLA was identified by CCTA, but not detected by echocardiography. Two-chamber (a), four-chamber (b) multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) images and a 3D volume rendering (VR) image (c) revealed SCLA (black arrow). CCTA examination of the same patient revealed embolism in the left circumrotatory branch (d, blue arrow). Considering an exogenous embolus, the patient was given anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapy, and 4 months later, the lesion on the left circumrotatory branch had disappeared (e)

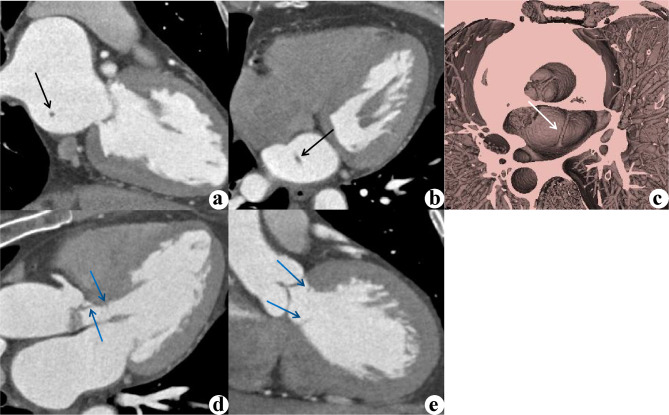

SCLA without valve connection was previously not considered to have pathological significance, but it has been associated with cardiac embolism and other serious complications [12, 18]. The length of the cord may be a feature that requires attention, as a longer SCLA is more likely to interfere with hemodynamics or impede atrial intervention [8]. Structural abnormalities of the left atrium and enlargement of the left atrium are traditionally believed to be risk factors for stroke. When the left atrium is enlarged to a certain extent, the drag caused by the remodeling of the left atrium on SCLA may cause cardiac discomfort. Additionally, it is suggested that SCLA is more prone to occur around the pulmonary vein ostia, especially near the right superior pulmonary vein ostia. Many triggers of atrial fibrillation have been thought to originate from abnormal sites in the myocardial sleeve at the junction of the pulmonary vein or vena cava with the left atrial chamber. The incidence of atrial arrhythmias also significantly differs between the case and control groups in this study. Experience and evidence on how to manage SCLA during radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation may be lacking, which warrants further research. One SCLA patient had an incomplete septum below the aortic valve (Fig. 3), suggesting that SCLA may coexist with other cardiac structural abnormalities, but the results showed that the more common structural abnormalities were a patent foramen ovale and atrial septal pouch. As mentioned in the literature, SCLA may coexist with a Chiari network, supraventricular arrhythmia, and abnormal valve development [19], none of which were observed in this study.

Fig. 3.

A 50-year-old female presented with intermittent chest tightness for several months. CCTA examination revealed an incomplete diaphragm under the aortic valve and the presence of SCLA. Two-chamber (a), four-chamber (b) MPR images and a 3D VR image (c) revealed SCLA (black arrow), which was not detected by echocardiography. A three-chamber MPR image (d) and a coronal MPR image (e) of the same patient showed concomitant subaortic incomplete membrane (blue arrows), which was mistaken by ultrasound for moderate stenosis of the aortic valve

SCLA should be differentiated from cor triatriatum in imaging diagnosis. The incidence of both structures was similar (0.1–0.4% vs. 0.32%) [20, 21]. In cor triatriatum patients, the left atrium is divided into two parts by an incomplete diaphragm. The true left atrium connects to the mitral orifice and left atrial appendage, and the secondary atrium receives bilateral pulmonary venous blood flow and communicates with the true left atrium through a narrow orifice. The SCLA is not a membrane-like structure, but a cable-strip structure connected to different walls of the left atrium, which can be clearly distinguished by 3D reconstruction and postprocessing technology. Because an SCLA does not cause regional segmentation of the left atrium, there is little or no serious hemodynamic change.

One potential future research direction could be to conduct a prospective cohort study to further investigate the impact of SCLA variations on cardiac function and patient prognosis. By following a group of patients with this anomaly over time, researchers can assess whether it is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation, stroke, or other cardiovascular events. Additionally, studying the hemodynamic effects of SCLA variations through advanced imaging techniques such as echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may provide valuable insights into its impact on left atrial function and blood flow dynamics. Another important avenue for future research could involve intracardiac electrophysiology and genetic studies to explore the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the development of SCLA. By investigating potential genetic markers or mutations associated with this anomaly, researchers may uncover novel pathways involved in cardiac development and function, ultimately leading to a better understanding of its pathophysiology. Furthermore, collaborative studies involving multi-center databases or international registries could help elucidate the global prevalence and clinical relevance of SCLA variations. By pooling data from various institutions and countries, researchers can gather a larger sample size and improve the generalizability of their findings, ultimately enhancing our knowledge of this rare cardiac anomaly.

This study has certain limitations. First, the incidence of SCLA was too low, and the impact of this abnormal structure on patients may be masked by other accompanying diseases or symptoms. Second, this study simply compared the differences between the case group and the control group and did not control for other confounding factors with the multivariate regression model. The exact clinical significance needs larger cohort studies and long-term follow-up. Third, the sample originated from a single institution, and selection bias was consequently inevitable. Furthermore, the underlying mechanism of differences between subgroups needs to be further explored and verified. This study demonstrates that CCTA can accurately identify this structure, laying a foundation for future in-depth research and exploration of its hidden value.

Conclusion

In summary, while SCLA is rare, CCTA can accurately detect and delineate this abnormal structure compared to echocardiography. SCLA may lead to systemic embolism or be associated with atrial arrhythmia, and can increase the difficulty of left atrial interventional surgery. Radiologists need to accurately describe and diagnose this rare structural abnormality to improve its management and reduce potential complications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SCLA

Suspended cord of the left atrium

- CCTA

Coronary CT angiography

- ECG

Electro cardio-gated

- MPR

Multiplanar reconstruction

- VR

Volume reconstruction

Author contributions

HT, YW and BW conceived and planned the study. HT wrote the manuscript. YW and BW carried out the research. YL, YL and YH contributed to data preparation. YW and BW provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the medical research project of Hebei Health Commission (No. 20221053). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by institutional review board of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (number: 2022-R089) and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and it’s later amendments. Due to the nature of retrospective study, informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bailin Wu and Yankai Wu contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-corresponding authors.

Contributor Information

Yankai Wu, Email: 1061382709@qq.com.

Bailin Wu, Email: wubailins@163.com.

References

- 1.Saade W, Baldascino F, De Bellis A, et al. Left atrial anomalous muscular band as incidental finding during video-assisted mitral surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(7):E538–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin RB, Schmitt M, Ray S. Left atrial fibrous band, an unexpected mechanism of mitral regurgitation. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12(7):552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Halloran L, O’Brien J. The use of computed tomography pulmonary angiography in the diagnosis of heart failure in the acute setting. Ir J Med Sci. 2020;189(4):1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherif HM, Banbury MK. Accessory left atrial chordae: an unusual cause of mitral valve insufficiency. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(2):e3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin HJ, Park HK, Jung JW, et al. Abnormal fibrous band from the left atrium to the left ventricle causing mitral regurgitation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47(4):748–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim TS, Cho KR, Lim DS. Double accessory left atrial chordae tendineae resulting in mitral regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(1):e5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liou K, Premaratne M, Mathur G. Left atrial band: a rare congenital anomaly. Ann Card Anaesth. 2014;17(4):318–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsaid A, Cawley PJ, Bauch TD, et al. Hanging by a thread, severe mitral regurgitation due to accessory left atrial cord. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(8):943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Onghia G, Martin M, Mancini MT, et al. A late presentation of congenital cardiac anomaly: accessory chordae from the left atrium causing severe mitral regurgitation. Echocardiography. 2018;35(5):750–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurtado-Sierra D, Fernández-Gómez Ó, Manrique-Rincón F, et al. Cuerda auricular izquierda accesoria: causa infrecuente de insuficiencia mitral en niños [Accessory left atrial chordae: an unusual cause of mitral regurgitation in children]. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2018;88(2):156–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arroyo Rivera B, Cortes M, Tuñon J. An accessory chord in a wrong place. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2019;4(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nnaoma C, Sandhu G, Sossou C, et al. A Band that causes leaky valves: severe mitral regurgitation due to Left Atrial Fibrous Band-A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Cardiol. 2019;2019:2458569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abe Y, Ebesu C, Matsumura Y, et al. Anomalous fibromuscular cord of the left atrium. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(10):1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vega C, Papasozomenos G, Marvaki A, et al. Left atrial accessory chord causing inverse tethering of the posterior mitral leaflet and severe regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;23(1):e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omidi F, Sheibani M, Salimi E, et al. Accessory Left Atrial Mitral Chordae Tendineae presenting as a particle on the mitral leaflet in a Young Woman with Stroke. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2021;31(2):122–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ku L, Lv H, Ma X. A rare congenital anomaly: anomalous fibromuscular cord of the left atrium. J Card Surg. 2022;37(7):2107–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D, Kwon BS, Kim DH, et al. Surgical outcomes of Cor Triatriatum Sinister: a single-center experience. J Chest Surg. 2022;55(2):151–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozer O, Sari I, Davutoglu V, et al. Cryptogenic stroke in two cases with left atrial band: coincidence or cause? Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(2):360–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma M, Pandey NN, Kumar S, et al. Incidentally detected anomalous left atrial fibromuscular band. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(1):e248402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Işık O, Akyüz M, Ayık MF, et al. Cor triatriatum sinister: a case series. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2016;44(1):20–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bardia A, Montealegre-Gallegos M, Owais K, et al. Mitral regurgitation secondary to infective endocarditis of the mitral valve in a patient with cor triatriatum sinistrum. Ann Card Anaesth. 2014;17(3):240–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.