Abstract

All cells must detect, interpret, and adapt to multiple and concurrent stimuli. While signaling pathways are highly specialized, different pathways often share components or have components with overlapping functions. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the high osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway has two seemingly redundant branches, mediated by Sln1 and Sho1. Both branches are activated by osmotic pressure, leading to phosphorylation of the MAPKs Hog1 and Kss1. The mating pathway is activated by pheromone, leading to phosphorylation of the MAPKs Fus3 and Kss1. Given that Kss1 is shared by the two pathways, we investigated its role in signal coordination. We activated both pathways with a combination of salt and pheromone, in cells lacking the shared MAPK and in cells lacking either of the redundant branches of the HOG pathway. By systematically evaluating MAPK activation, translocation, and transcription programs, we determined that Sho1 mediates cross talk between the HOG and mating pathways and does so through Kss1. Further, we show that Kss1 initiates a transcriptional program that is distinct from that induced by Hog1 and Fus3. Our findings reveal how redundant and shared components coordinate concurrent signals and thereby adapt to sudden environmental changes.

MAPKs are important in cell growth and differentiation, but the function of redundant and shared pathway components is poorly understood.

The yeast HOG pathway employs two osmosensing systems. The authors show that both activate the MAPK Hog1 but have opposing effects on the MAPK Kss1, which is shared with the mating pathway. Kss1 initiates a transcriptional program distinct from that of the HOG- and mating-specific MAPKs.

This work will inform mechanisms of crosstalk in mammals as well as in other fungi, including pathogenic species, having a high similarity of organization and function of key pathway components.

INTRODUCTION

All cells can sense diverse environmental signals and generate an appropriate response. Many of these inputs are interpreted by MAPK pathways, a signaling system that is conserved across the animal, plant, and fungal kingdoms. These systems share a similar architecture comprised of a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), a MAPK kinase (MAP2K) and a MAPK kinase kinase (MAP3K). Once activated, the MAPK can transmit external stimuli as distinct patterns of intracellular phosphorylation and transcription. In humans, the MAPKs p38 and JNK respond to stress signals that promote apoptosis, inflammation, and autophagy. The MAPKs ERK1 and ERK2 are activated by growth factors that initiate cell division and differentiation (Lemmon and Schlessinger, 2010).

Elucidating the mechanisms of MAPK signal transduction is crucial to understanding diseases such as cancer and inflammatory disorders, caused by mis-regulation of signals. However, due to the complexity of the mammalian MAPK systems, it remains a challenge to fully understand the molecular basis of signal regulation and pathway coordination. In comparison, the yeast MAPK signaling pathways provide a relatively simple and well characterized model for the study of these processes.

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the MAPK Fus3 (orthologue of ERK1/2) is activated by peptide pheromones that initiate fusion of haploid a- and α-type cells to form diploid cells. These pheromones bind to corresponding receptors on the surface of the opposite mating type, initiating a signal transduction cascade that consists of the MAP3K Ste11, the MAP2K Ste7 and the MAPK Fus3 (Bardwell, 2005). This cascade initiates cell cycle arrest in G1, changes in gene expression, and the formation of mating projections, or shmoos, which allow the two cells to fuse. The precise and specific action of these pheromones ensures that mating occurs only between compatible partners.

Hog1 (orthologue of p38) is activated by osmotic pressure and leads to the accumulation of cytosolic second messengers and protective osmolytes (Albertyn et al., 1994; Hounsa et al., 1998; Shellhammer et al., 2017). Upon activation, Hog1 translocates to the nucleus and modulates the expression of genes involved in osmolyte production and accumulation. For example, glycerol acts as an osmoprotectant, balancing the internal and external osmotic pressures. Additionally, osmotic stress signaling triggers a pause in cell cycle progression and changes in metabolism that, collectively, help to protect the cell from damage.

The high osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway consists of two branches (Saito and Posas, 2012); the first of these is comprised of a four-component osmosensor consisting of Sho1, Opy2, Hkr1, and Msb2, which activates the MAP3K Ste11 (Posas et al., 1996; Tatebayashi et al., 2007; Tanaka et al., 2014; Tatebayashi et al., 2015; Nishimura et al., 2016; Yamamoto et al., 2016). The second branch is a phospho-relay system comprised of Sln1, Ypd1, and Ssk1, which activates the MAP3Ks Ssk2 and Ssk22 (Maeda et al., 1994; Posas et al., 1996; Posas and Saito, 1998; Reiser et al., 2003). Both branches converge on the same MAP2K Pbs2 and MAPK Hog1.

Although the mating and HOG pathways share the MAP3K Ste11, osmotic pressure does not activate Fus3 and pheromone does not activate Hog1. Such pathway insulation is achieved at multiple points throughout the pathway, from the receptor level to the transcription level. For example, when the cells are activated by osmotic stress, the shared MAP3K Ste11 is recruited by the MAP2K and scaffold protein Pbs2 to direct signals through the Ste11-Pbs2-Hog1 circuit (O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 2004; Tatebayashi et al., 2006). Conversely, when cells are activated by pheromone, the scaffold protein Ste5 directs Ste11 to relay signals through the Ste11-Ste7-Fus3 circuit (Flatauer et al., 2005) (Figure 1). Pathway insulation is not absolute, however. It has long been known that pheromone and osmotic pressure both activate a third MAPK, Kss1 (Gartner et al., 1992; Hao et al., 2008) (Figure 1). Kss1 has an important role in the regulation of filamentous growth, a process important for adaptation and survival under nutrient-poor conditions. Its role in mating and HOG activation is poorly understood.

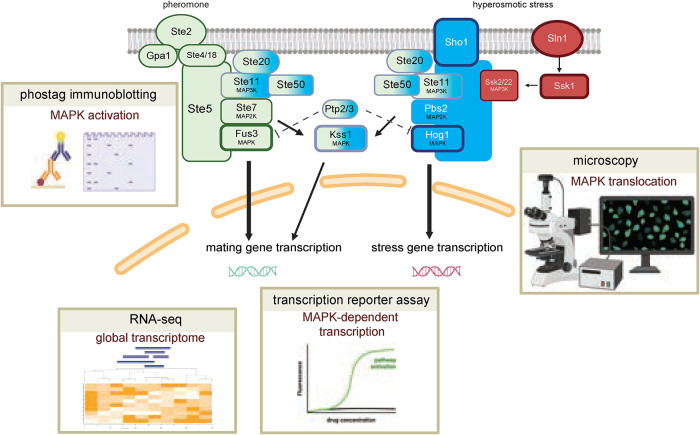

FIGURE 1:

Overview of the yeast MAPK pathways. Left, mating pathway. Right, HOG pathway. Pheromone α factor activates the mating pathway through a receptor (Ste2), G protein (Gpa1, Ste4, Ste18), and a scaffold protein Ste5 bound to the MAP3K Ste11, the MAP2K Ste7 and the MAPK Fus3. Hyperosmotic stress activates the HOG pathway through the Sho1 and Sln1 branches. The Sho1 branch activates the MAP3K Ste11, the MAP2K and scaffold protein Pbs2 and the MAPK Hog1. The Sln1 branch activates Ssk1 and the MAP3Ks Ssk2/22, MAP2K Pbs2 and MAPK Hog1. The MAP4K Ste20, Ste11 and its binding partner Ste50, the tyrosine phosphatases Ptp2/3 and the MAPK Kss1 are shared between the two pathways. Other components are omitted for brevity. Insets, summary of methods to measure signaling consequences: phos-tag immunoblotting to measure MAPK activation, RNA-seq to measure global transcriptome changes, transcription reporter assay to measure the efficacy and potency of MAPK-mediated transcription, and microscopy to track MAPK translocation.

Here we examine how signaling through Kss1 allows the mating and HOG pathways to coordinate signals in response to concurrent stimulation. To understand signal coordination, we activated the pathways using pheromone and salt, alone or in combination. To understand the individual roles of the two HOG branches, we deleted SHO1 or SSK1. Through measures of MAPK activation, translocation, and transcriptional induction, we show that the Sho1 branch sustains duration while the Sln1 branch dictates the amplitude of Hog1 activation. Further, we determine that the Sln1 branch, but not the Sho1 branch, limits Hog1-mediated transcription. When Sln1 signaling is absent, Sho1 is free to activate Kss1, and this is sufficient to partially activate the mating pathway. When Kss1 is absent, cross-pathway signaling is abrogated. Thus, there are important differences in the Sho1 and Sln1 branches, particularly at the level of transcription, and these differences are mediated through activation of Kss1. Kss1, in turn, initiates the expression of a unique set of genes.

RESULTS

The Sho1 branch induces a unique set of genes

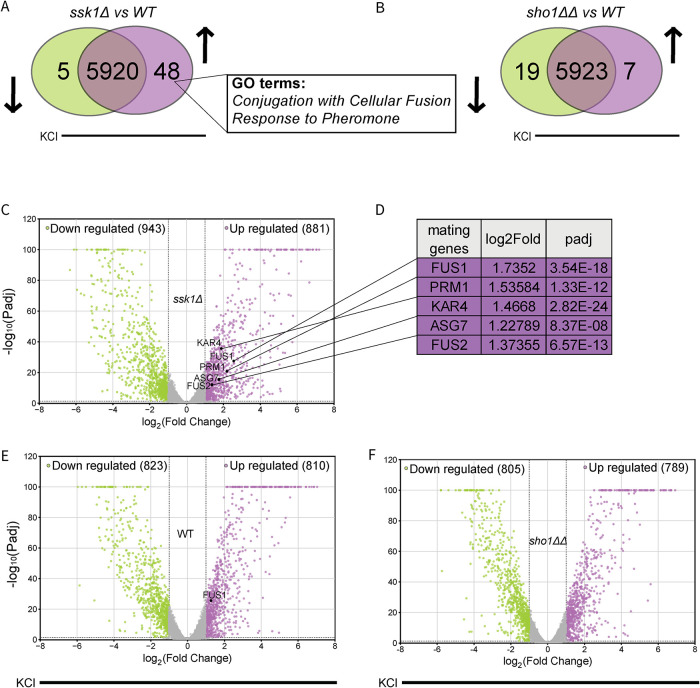

Our hypothesis was that the osmosensing system contributes to cross-pathway regulation by activating or inhibiting components that it shares with the mating pathway; in particular, the response to pheromone would be affected by osmotic stress signaling through Sho1 but not Sln1. Before determining how the two HOG branches affect the mating pathway, we compared the effects of branch deletions on the osmotic stress response. We first assessed the transcriptomes of the ssk1Δ (Sho1 branch only) and sho1ΔΔ (Sln1 branch only)1 strains treated with osmotic stress. For these experiments, we used an intermediate concentration (350 mM) of KCl. We do not use NaCl because at high concentrations it inhibits nucleotidase activity, reducing adenine nucleotide pools and slowing cell division (Murguía et al., 1996). We measured expression after 15 min of treatment with KCl. This timepoint represents the peak of the transient transcription response and is early enough to avoid measures of secondary effects, for example those arising from cell cycle arrest (Gasch et al., 2000; Rep et al., 2000; Causton et al., 2001; O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 2004; Capaldi et al., 2008). Then, we evaluated the differentially expressed genes (DEGs, defined as those with log2(fold change) >1 and adjusted P value < 0.05), comparing genes that are induced by salt in ssk1Δ but not wild type and sho1ΔΔ but not wild type, respectively (Figure 2, A and B). Most of the genes were unaffected by deletion of SSK1 or SHO1 (Figure 2, A and B) (Tables 1–4). The 48 genes induced with salt treatment in ssk1Δ cells (Table 1) are enriched in mating response processes such as Conjugation with Cellular Fusion, Response to Pheromone, and Reproductive Processes (Table 2). On the other hand, the seven genes induced in sho1ΔΔ cells (Table 3) are enriched in Siderophore and Iron Ion Transport (Table 4). Additionally, out of the 881 salt-induced genes in ssk1Δ cells (Figure 2C), five are well known to be induced in response to mating pheromones (Figure 2D). Indeed, these are among the 10 transcripts most strongly induced by treatment with pheromone. Conversely, none of the salt-induced transcripts in wild type or sho1ΔΔ cells are related to mating (Figure 2, B, E, and F). In conclusion, these data show that either of the two branches is sufficient to sustain the HOG transcription response. Of the small number of genes uniquely affected by deletion of SSK1 however, many are also induced by mating pheromone. Thus, when directed through the Sho1 branch of the HOG pathway, osmotic stress partially activates the mating response.

FIGURE 2:

High-confidence transcriptome evaluation using RNA-seq. (A) Salt-induced transcriptome of wild type compared with ssk1Δ. Green, genes down-regulated in mutant but not in wild type. Purple, genes upregulated in mutant but not in wild type. Overlap, unaffected genes. The two most significantly enriched GO terms are shown. (B) Salt-induced transcriptome of wild type compared with sho1ΔΔ, as in (A). (C) Volcano plot of genes up- or down-regulated in ssk1Δ cells after treatment with 350 mM KCl. Highlighted are those with |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1 and adjusted P ≤ 0.05. (D) Genes of interest, five out of the top 10 genes most up-regulated in response to α factor. (E) Volcano plot of genes up- or down-regulated in wild type (WT) cells after treatment with KCl. (F) Volcano plot of genes up- or down-regulated in sho1ΔΔ cells after treatment with KCl. Statistical significance, Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P value, calculated from three independent experiments.

TABLE 1:

Genes up-regulated comparing wild type and ssk1Δ cells, treated with 350 mM KCl.

| ID | log2fold | Padj |

|---|---|---|

| tR(ACG)L | 2.331325259 | 3.49E-06 |

| tR(UCU)G3 | 2.237354189 | 0.0020 |

| AAD15 | 2.154882652 | 0.0004 |

| CSN9 | 1.949884589 | 0.0009 |

| tH(GUG)E2 | 1.889031387 | 0.0008 |

| FUS1 | 1.735204285 | 3.54E-18 |

| SPR28 | 1.661148355 | 3.98E-06 |

| snR57 | 1.558772513 | 0.0027 |

| tA(AGC)P | 1.54614246 | 0.0025 |

| PRM1 | 1.535836072 | 1.33E-12 |

| tL(CAA)N | 1.532026669 | 0.0350 |

| CDA1 | 1.503543825 | 1.43E-05 |

| KAR4 | 1.466801483 | 2.82E-24 |

| ANB1 | 1.455976063 | 0.0033 |

| AGA1 | 1.409526429 | 1.71E-26 |

| MFA2 | 1.375625424 | 1.95E-05 |

| NVJ3 | 1.368014848 | 7.78E-09 |

| IRC18 | 1.337976602 | 6.01E-05 |

| HST4 | 1.318790362 | 1.59E-17 |

| FIT3 | 1.294831715 | 0.0008 |

| FIT2 | 1.275439252 | 0.0060 |

| CAB5 | 1.257088391 | 3.22E-11 |

| PLP1 | 1.253985135 | 6.20E-17 |

| BAR1 | 1.238823112 | 1.99E-31 |

| ASG7 | 1.227893601 | 8.37E-08 |

| DCV1 | 1.194700526 | 6.32E-08 |

| YOL164W-A | 1.180276633 | 0.0028 |

| ERR3 | 1.17164921 | 0.0451 |

| NME1 | 1.171256008 | 0.0012 |

| SPC19 | 1.147450075 | 3.00E-21 |

| SAS4 | 1.145647854 | 8.06E-37 |

| snR49 | 1.12815756 | 0.0074 |

| snR30 | 1.117927324 | 0.0039 |

| FAR1 | 1.111846717 | 5.58E-14 |

| MFA1 | 1.091314102 | 0.0060 |

| TEC1 | 1.077655215 | 1.61E-27 |

| VPS64 | 1.064499742 | 3.02E-41 |

| RKM2 | 1.041809898 | 1.04E-05 |

| SFG1 | 1.040667946 | 8.78E-08 |

| ZEO1 | 1.025951284 | 0.0060 |

| YER053C-A | 1.022586573 | 0.0179 |

| SND1 | 1.018969362 | 4.95E-25 |

| CDC1 | 1.018386359 | 2.02E-19 |

| NGG1 | 1.014161333 | 1.40E-22 |

| YER138W-A | 1.013263198 | 0.0035 |

| YOR343C | 1.012668455 | 0.0019 |

| snR10 | 1.0080169 | 0.0202 |

| MSS116 | 1.005220778 | 1.75E-16 |

TABLE 4:

Enrichment of GO terms for genes listed in Table 3.

| Gene ontology term | Cluster frequency | Genome frequency | Corrected P-value | FDR | False positive | Genes annotated to the term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| siderophore transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 8 of 7166 genes, 0.1% | 7.01E-07 | 0.00% | 0 | FIT3, FIT2, ARN2 |

| iron coordination entity transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 18 of 7166 genes, 0.3% | 1.01E-05 | 0.00% | 0 | ARN2, FIT2, FIT3 |

| iron ion transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 32 of 7166 genes, 0.4% | 6.15E-05 | 0.00% | 0 | ARN2, FIT2, FIT3 |

| transition metal ion transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 54 of 7166 genes, 0.8% | 0.0003 | 0.00% | 0 | FIT3, ARN2, FIT2 |

| metal ion transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 84 of 7166 genes, 1.2% | 0.00115 | 0.40% | 0.02 | FIT3, FIT2, ARN2 |

| monoatomic cation transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 93 of 7166 genes, 1.3% | 0.00156 | 0.67% | 0.04 | FIT3, ARN2, FIT2 |

| monoatomic ion transport | 3 of 7 genes, 42.9% | 97 of 7166 genes, 1.4% | 0.00178 | 0.86% | 0.06 | FIT3, FIT2, ARN2 |

TABLE 2:

Enrichment of GO terms for genes listed in Table 1.

| Gene ontology term | Cluster frequency | Genome frequency | Corrected P-value | FDR | False positive | Genes annotated to the term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conjugation with cellular fusion | 11 of 48 genes, 22.9% | 114 of 7166 genes, 1.6% | 2.89E-08 | 0.00% | 0 | BAR1, MFA2, FUS1, CSN9, AGA1, FAR1, PRM1, MFA1, KAR4, VPS64, ASG7 |

| cellular response to pheromone | 8 of 48 genes, 16.7% | 75 of 7166 genes, 1.0% | 5.49E-06 | 0.00% | 0 | CSN9, VPS64, MFA1, MFA2, AGA1, FAR1, BAR1, PLP1 |

| response to pheromone | 8 of 48 genes, 16.7% | 76 of 7166 genes, 1.1% | 6.10E-06 | 0.00% | 0 | VPS64, CSN9, PLP1, MFA1, MFA2, BAR1, FAR1, AGA1 |

| sexual reproduction | 14 of 48 genes, 29.2% | 395 of 7166 genes, 5.5% | 3.39E-05 | 0.00% | 0 | BAR1, MFA2, FUS1, CSN9, SPR28, IRC18, CDA1, AGA1, FAR1, PRM1, MFA1, KAR4, VPS64, ASG7 |

| reproductive process | 14 of 48 genes, 29.2% | 462 of 7166 genes, 6.4% | 0.00023 | 0.00% | 0 | BAR1, MFA2, IRC18, CDA1, FUS1, CSN9, SPR28, FAR1, AGA1, PRM1, MFA1, VPS64, KAR4, ASG7 |

| cellular response to organic substance | 8 of 48 genes, 16.7% | 164 of 7166 genes, 2.3% | 0.00227 | 0.00% | 0 | CSN9, VPS64, PLP1, FAR1, BAR1, AGA1, MFA1, MFA2 |

| response to pheromone triggering conjugation with cellular fusion | 5 of 48 genes, 10.4% | 54 of 7166 genes, 0.8% | 0.00557 | 0.00% | 0 | VPS64, MFA1, MFA2, AGA1, FAR1 |

TABLE 3:

Genes up-regulated comparing wild type and sho1ΔΔ cells, treated with 350 mM KCl.

| ID | log2fold | Padj |

|---|---|---|

| HXT14 | 1.8954463 | 0.0159 |

| FIT2 | 1.3324466 | 1.10E-05 |

| FIT3 | 1.1932816 | 3.90E-05 |

| ANB1 | 1.1259897 | 0.001 |

| ARN2 | 1.1253093 | 5.17E-05 |

| snR56 | 1.1107093 | 0.045 |

| YJL047C-A | 1.1014688 | 0.010 |

The Sln1 branch ensures normal amplitude while the Sho1 branch maintains normal duration of Hog1 activation

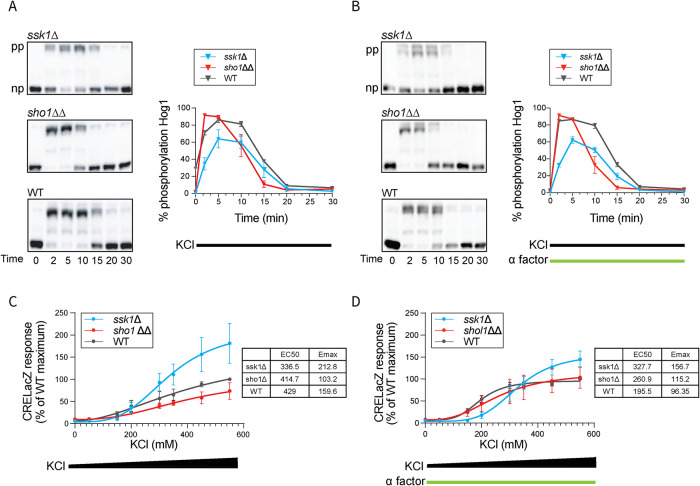

From our RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) results, we established that the Sho1 and Sln1 branches regulate most, but not all, of the same transcripts. For the transcripts induced by KCl in the ssk1Δ strain but not in the sho1ΔΔ strain, many are also induced by pheromone stimulation. To determine the molecular basis for the differences observed, we first evaluated the effect of each branch on the upstream MAPK Hog1. Like other MAPKs, Hog1 is activated through phosphorylation of two activation loop residues (Thr-174 and Tyr-176). To that end, we measured the phosphorylation of Hog1 over time, using Hog1 antibodies and phos-tag immunoblotting. Phos-tag gel electrophoresis is a specialized method that can separate the activated dual-phosphorylated species (top band, Figure 3A) from unactivated nonphosphorylated species (bottom band, Figure 3A). Thus, we can measure the proportion of total Hog1 that is phosphorylated in response to osmotic stress. In sho1ΔΔ, Hog1 was fully activated at the earliest timepoint, but was less activated at the later timepoints relative to wild type. In ssk1Δ, Hog1 activation was dampened at all timepoints (Figure 3A). As expected, Hog1 phosphorylation was largely unaffected by the coaddition of pheromone (Figure 3B). We conclude that the Sln1 branch (sho1ΔΔ) ensures the normal amplitude of Hog1 activation while the Sho1 branch (ssk1Δ) maintains the normal duration of Hog1 activation.

FIGURE 3:

HOG pathway activation. (A) Hog1 activation dynamics. Left, Hog1 dual phosphorylation (pp) over time in response to 350 mM KCl in ssk1Δ, sho1ΔΔ or wild type (WT), resolved using the phos-tag method. np, nonphosphorylated. Right, quantification of blots. (B) Same as A but in response to 350 mM KCl and 3 µM α factor. Error bars, SD, calculated from the mean of three independent experiments with three replicates each. (C) Osmotic stress transcription reporter (CRE-lacZ), 0–550 mM KCl. (D) Same as C but with 30 µM α factor. Insets, efficacy (Emax) and half maximal effective concentration (EC50). Error bars, SD, calculated from the mean of five independent experiments with three replicates each.

Hog1-mediated transcription is amplified by the Sho1 branch and is dampened by the Sln1 branch

The two branches of the HOG pathway had distinct effects on a small subset of all transcripts regulated by salt stress (Figure 2). At the level of the MAPK, the mutations yielded distinct and complementary effects on the amplitude and duration of Hog1 activation (Figure 3). We next considered whether the differences in Hog1 activation would affect the amplitude of Hog1-mediated transcription, and whether any such differences were dependent on the amplitude of the initiating stimulus. To that end, we used an osmotic stress–dependent promoter fused with the β-galactosidase gene (CRE-LacZ), and stimulated the cells with 0–550 mM KCl. This concentration range was selected because it is below that which dampens and delays the mating response through global (Hog1-independent) processes (Nagiec and Dohlman, 2012). As shown in Figure 3C, both branches showed dose-dependent gene induction; at the highest concentrations of KCl, the ssk1Δ strain responded more than wild type while the sho1ΔΔ strain responded slightly less than wild type. Thus, the Sho1 and Sln1 branches have distinct and complementary effects on the amplitude of transcription (O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 2004). Paradoxically, attenuated activation of Hog1 confers greater induction of Hog1-dependent transcription, possibly due to a delay in Hog1-mediated phosphorylation, and consequent inhibition, of Ste50 and Sho1 (Hao et al., 2007; Hao et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2010). For reasons detailed below, our focus here is on components acting later in the pathway.

Given that the Sho1 branch shares signaling components with the mating pathway, we also examined whether treatment with mating pheromone affects Hog1-mediated transcription. As noted above, transcription through the Sho1 branch was elevated in comparison to the other strains, particularly at higher concentrations of KCl. When we costimulated the cells with pheromone, the differences narrowed substantially (Figure 3D). These results show that, while Sho1 and Sln1 branches have distinct and complementary effects on osmotic stress–dependent transcription (Figure 3C), these differences are masked upon costimulation with pheromone. Because these differences were not evident at the level of Hog1 activation, the effect of pheromone was most likely downstream of, or parallel to, the MAPK. Another possibility, considered in the next section, is that the two branches have distinct effects on translocation of Hog1 into the nucleus.

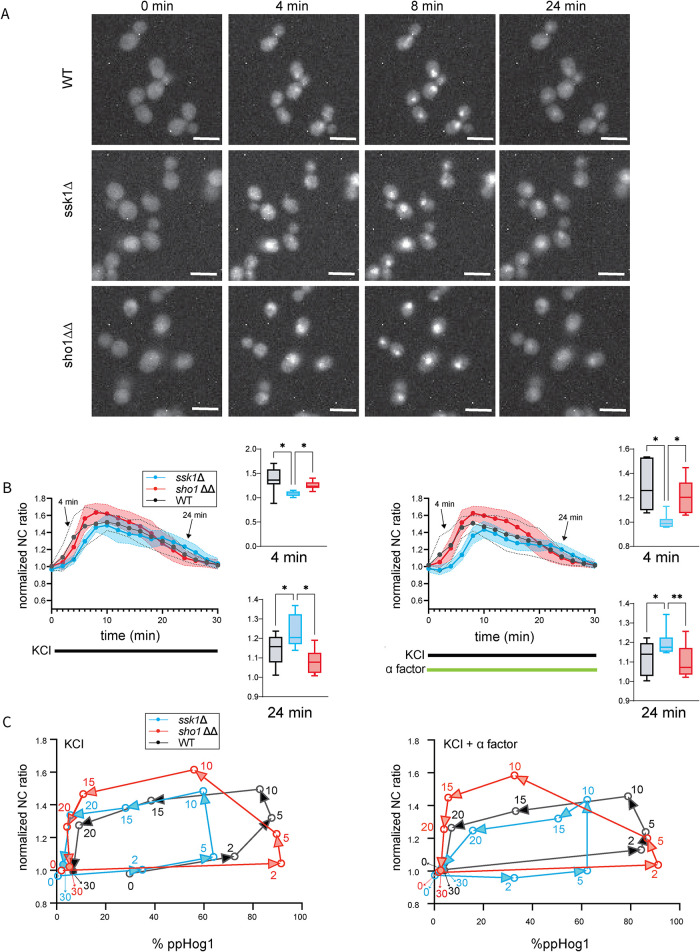

The Sho1 branch promotes Hog1 retention in the nucleus

Above we show that the Sho1 and Sln1 branches regulate the amplitude of Hog1 activation and Hog1-mediated transcription, and do so in distinct and complementary ways. In addition, we show that pheromone has no effect on Hog1 activation but it does affect Hog1-dependent transcription (Figure 3). We postulated that these differences might be attributed to differences in Hog1 localization. Upon activation, Hog1 translocates into the nucleus (Ferrigno et al., 1998). If Hog1 is retained in the nucleus when activated by the Sho1 branch, or exits the nucleus more quickly in cells costimulated with pheromone, these differences could account for the differences in transcription. To test the hypothesis, we labeled Hog1 by fusing it to a red fluorescent protein (mRuby2) and labeled the nuclear protein Htb2 with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Huh et al., 2003). Then we activated the HOG pathway with osmotic stress and tracked Hog1 translocation in live cells by fluorescence microscopy. Compared with wild type, translocation of Hog1 into and out of the nucleus was delayed in the ssk1Δ cells relative to the other strains (Figure 4, A and B). While increased phosphorylation correlated with nuclear localization (compare Figures 3A and 4B left, and Figures 3B and 4B right) there was a substantial lag between Hog1 activation and nuclear entry, as well as between Hog1 inactivation and nuclear exit (Figure 4C). In contrast, changes in translocation do not appear responsible for cross-talk, since the presence or absence of pheromone yielded similar patterns of Hog1 translocation (compare left and right panels of Figure 4, B and C). Overall, our results are consistent with the model that longer retention of Hog1 in the nucleus might lead to elevated Hog1-mediated transcription. Moreover, the difference of Hog1 translocation between the two branches mirrors that of Hog1 activation. On the other hand, costimulation with pheromone had no effect on Hog1 activation (Figure 3, A and B) or translocation (Figure 4, B and C), but diminished the differences in transcription exhibited by the two mutant strains (compare Figure 3, C and D). We conclude that pheromone acts not on Hog1, but more likely on another pathway component to regulate salt-induced transcription.

FIGURE 4:

Hog1 translocation dynamics. (A) Cells expressing the integrated histone gene product Htb2-GFP and Hog1-mRUBY2, treated with 350 mM KCl. Images of Hog1-mRUBY2 were taken pretreatment (0 min), as well as 4 min, 8 min, and 24 min after treatment, demonstrating Hog1 translocation in and out of the nucleus. Top, wild type (WT); middle, ssk1Δ; bottom, sho1ΔΔ. Scale bars, 5 µm. (B) Left, Hog1 translocation with 350 mM KCl, quantified as the ratio of nuclear and cytoplasmic mRUBY2 signal; data collected every 2 min for 30 min. Right, same as the left panel except cells were treated with 350 mM KCl and 30 µM α factor. Error bars, SD calculated from the mean of three independent experiments with three replicates each. ANOVA comparing the two mutants and wild type at 4 min and 24 min. *, P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; other comparisons, not significant. (C) Comparison of Hog1 activation (% phosphorylated Hog1) versus Hog1 translocation (NC ratio). Each point is plotted as the mean of activated Hog1 and the mean of nuclear Hog1 in the population at the indicated timepoints (min). Left, Hog1 activation versus Hog1 nuclear translocation with 350 mM KCl. Right, with 350 mM KCl and 30 µM α factor.

The Sho1 branch activates mating pathway transcription

In our analysis of the HOG pathway, we observed discrepancies in MAPK activation and transcription responses. Whereas addition of pheromone had no effect on Hog1 activation or translocation the same treatment diminished the differences in transcription, particularly when comparing the wild type and ssk1Δ mutant strains (Figure 3, C and D). Addition of KCl to wild-type cells had no effect on mating pathway transcription, but the same treatment in ssk1Δ cells led to significant induction of genes known to be induced by mating pheromone (Figure 2). Accordingly, we considered different ways that osmotic stress might affect the mating pathway, particularly in ssk1Δ cells where signaling is directed through Sho1.

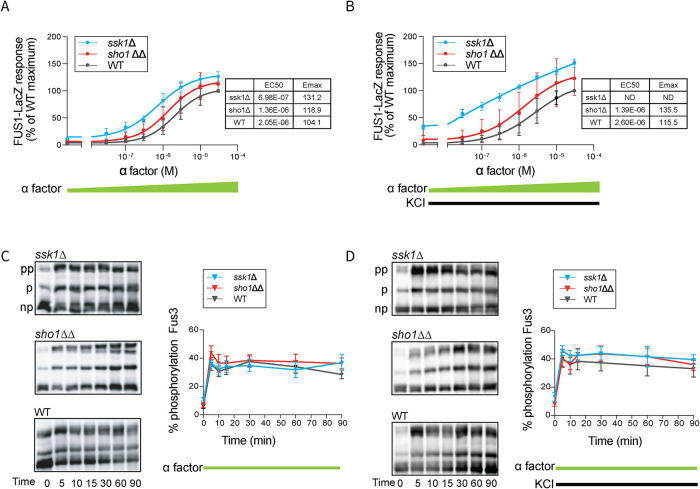

We first treated cells with a full range of pheromone concentrations (0–30 µM) and measured the response with a mating pathway reporter, comprised of the FUS1 promoter driving the β-galactosidase gene LacZ. As shown in Figure 5, there were minimal differences when comparing wild type, ssk1Δ and sho1ΔΔ cells (Figure 5A). However, with addition of KCl, we observed a substantial induction in ssk1Δ cells relative to wild type or the sho1ΔΔ mutant (leftmost datapoint, Figure 5B). These data mirror our RNA-seq results (Figure 2), where a subset of mating genes is up-regulated in ssk1Δ cells in response to osmotic stress. These differences are not reflected in activation of the MAPK Fus3 however, as determined by phos-tag immunoblotting (Figure 5, C and D). In all three strains, Fus3 reached peak activation within 5 min of pheromone treatment (Figure 5C), and the pattern was the same when we treated the cells with both osmotic stress and pheromone (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5:

Mating pathway activation. (A) Mating transcription reporter (FUS1-lacZ), 0–30 µM α factor. (B) Same as A but with the addition of 350 mM KCl. (C) Fus3 activation dynamics. Left, Fus3 dual phosphorylation (pp) over time in response to 3 µM α factor in ssk1Δ, sho1ΔΔ or wild type, resolved using the phos-tag method. p, monophosphorylated; np, nonphosphorylated. Right, Quantification of blots. (D) Same as C but in response to 350 mM KCl and 3 µM α factor. Insets, efficacy (Emax) and half maximal effective concentration (EC50); ND, not determined. Error bars, SD, calculated from the mean of three independent experiments with three replicates each.

Kss1, but not Fus3, is activated by the Sho1 branch of the HOG pathway

Our analysis revealed that cross-pathway regulation is bidirectional in the ssk1Δ strain; whereas pheromone dampens the response to salt (Figure 3, C and D), salt amplifies the response to pheromone (Figure 5, A and B). These effects of deleting SSK1 are evident at the level of transcription but not at the level of Hog1 or Fus3 activation. We next considered alternative mechanisms of cross-pathway regulation. Of the two branches in the HOG pathway, only the Sho1 branch shares components with the mating pathway (Figure 1). Many of the shared components are upstream of the MAPKs, and several of these are known targets of feedback phosphorylation by Hog1 (Hao et al., 2007; Hao et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2010; Nagiec and Dohlman, 2012; Mosbacher et al., 2023); but since Fus3 is poorly activated by salt stress even in the absence of Hog1 (Hao et al., 2008; Nagiec and Dohlman, 2012) and is unaffected by loss of SSK1 (Figure 5), we considered other components shared by the mating and HOG pathways and narrowed our focus on Kss1. Like Hog1, Kss1 is activated by salt stress (Hao et al., 2008). Like Fus3, Kss1 is activated by pheromone and can sustain the mating transcription program when Fus3 is absent (Gartner et al., 1992). Under these circumstances Kss1 activation is transient (Sabbagh et al., 2001; Hao et al., 2008; Winters and Pryciak, 2018), and so does not lead to invasive growth as occurs during nutrient limitation (Madhani et al., 1997; Cook et al., 1997; Bardwell et al., 1998; Maleri et al., 2004). Thus, Kss1 fits our criteria of a shared component acting at, or below, the level of the other MAPKs.

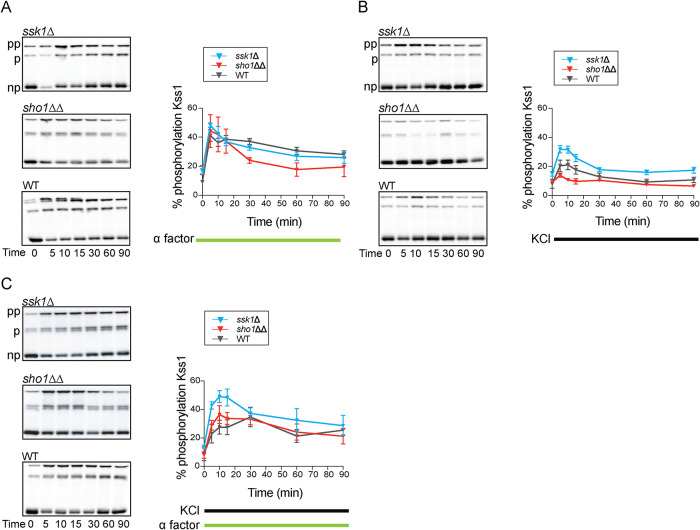

Accordingly, we investigated whether Kss1 was responsible for Sho1-mediated cross-pathway regulation. With pheromone treatment, Kss1 reached peak activation within the first 5 min and in all three strains tested (wild type, sho1ΔΔ, ssk1Δ; Figure 6A). With osmotic stress treatment, Kss1 reached peak activation at 5–10 min. In this case, the response was elevated in the ssk1Δ strain and was substantially diminished in the sho1ΔΔ cells, relative to wild type (Figure 6B). Whereas loss of SSK1 amplified phosphorylation of Kss1 it dampened phosphorylation of Hog1 (compare Figures 3A and 6B). Thus, while neither branch of the HOG pathway appreciably affects Kss1 activation in response to pheromone, signaling through Sho1 increases while Sln1 limits Kss1 activation in response to salt (Figure 6B); Sln1 also limits the response to salt plus pheromone (Figure 6C). The differences in Kss1 activity mirror the differences we observed using the mating pathway reporter (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 6:

Kss1 activation dynamics. (A) Left, Kss1 dual phosphorylation (pp) over time in response to 3 µM α factor in ssk1Δ, sho1ΔΔ or wild type (WT), resolved using the phos-tag method. p, monophosphoryalted; np, nonphosphorylated. Right, Quantification of blots. (B) Same as A but in response to 350 mM KCl. (C) Same as A but with 350 mM KCl and 3 µM α factor. Error bars, SD, calculated from the mean of three independent experiments with three replicates each.

The data presented above demonstrate that the mating transcription program is also induced by osmotic stress, but only when signaling is directed through Sho1 (ssk1Δ) (Figure 5B). In addition, we showed that HOG pathway transcription responds to mating pheromone, but again only when signaling is mediated by Sho1 (Figure 3, C and D). Both pathways activate Kss1, and full activation of this MAPK requires expression of Sho1 (Figure 6, A and B, ssk1Δ). Therefore, cross-talk is bidirectional at the level of transcription and Kss1 activation.

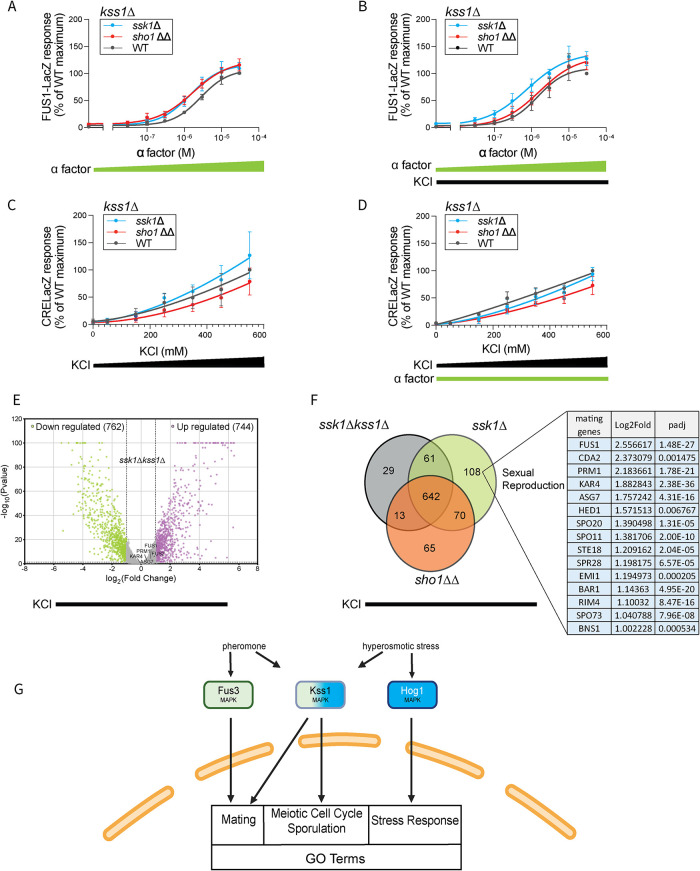

Kss1 mediates cross-talk between the two MAPK pathways

To test the importance of Kss1 activation, we repeated all three measures of transcription, comparing wild type and kss1Δ, and in cells lacking SSK1 or SHO1. We treated these cells with KCl, pheromone, or a combination of both, and measured the response with our FUS1-LacZ and CRE-LacZ assays. In every case, deletion of KSS1 eliminated the cross-pathway regulation seen in the absence of SSK1 (Sho1 branch only). The FUS1-lacZ response was no longer affected by the addition of KCl (compare the leftmost datapoints in Figure 7, A and B with Figure 5, A and B); the CRE-lacZ response was less affected by the addition of pheromone (compare the rightmost datapoints in Figure 7, C and D with Figure 3, C and D). The effects of KSS1 deletion were also reflected in the transcriptomics data. Mating pathway genes were no longer induced by KCl (compare Figures 7E and 2C). In conclusion, Kss1 mediates cross-talk between the two MAPK pathways.

FIGURE 7:

The mating and the HOG transcription responses in cells lacking Kss1. (A) Mating transcription reporter, 0–30 µM α factor. (B) Same as A but with the addition of 350 mM KCl. (C) Osmotic stress transcription reporter, 0–550 mM KCl. (D) Same as C but with the addition of 30 µM α factor. Efficacy and half maximal effective concentration, not determined. Error bars, SD. Error bars, SD, calculated from the mean of three independent experiments with three replicates each. (E) Volcano plot of genes up- or down-regulated in ssk1Δkss1Δ cells treated with 350 mM KCl. Highlighted are those with |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05. (F) Unique salt induced transcriptome of ssk1Δkss1Δ, ssk1Δ, and sho1ΔΔ cells, in response to 350 mM KCl. List of mating related genes with log2fold change and adjusted P value are displayed in the table. Statistical significance, Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P value, calculated from three independent experiments. (G) Cartoon listing the newly identified Kss1-specific GO terms.

Given the importance of Kss1 in cross-pathway regulation, we evaluated genes that are up-regulated when Kss1 is activated. In doing so, we extracted and combined the lists of genes that were regulated by salt in ssk1Δ and ssk1Δkss1Δ cells. We also filtered out genes induced in sho1ΔΔ cells since Kss1 is not activated by the Sho1 branch (Figure 7F). According to this analysis, we found that there are 108 DEGs when Kss1 is activated (Table 5). These genes are enriched in mating-related processes as well as processes under the gene ontology (GO) term Modified Amino Acid Transport (Table 6). Among the 15 genes enriched in pheromone-related processes (Figure 7F, right table), eight are induced by pheromone only in the presence of Kss1 (CDA2, HED1, SPO20, STE18, EMI1, RIM4, SPO73, BNS1). The remaining seven are induced by pheromone in the presence or absence of KSS1 (FUS1, PRM1, KAR4, ASG7, SPO11, SPR28, and BAR1). The eight Kss1-induced genes have as GO terms Sexual Reproduction, Meiotic Cell Cycle and Sporulation (Supplemental Table S3). In conclusion, Kss1 activation leads to a transcriptional program that is partially overlapping with Fus3 but distinct from Hog1, and one that is complementary to the cell growth-related genes regulated by the mating and the HOG pathways (Figure 7G).

TABLE 5:

Genes selectively induced by Kss1; genes up-regulated in ssk1Δ cells, but not in ssk1Δ kss1Δ cells or in sho1ΔΔ cells, treated with 350 mM KCl.

| Gene induced by kss1 activation | log2fold | Padj | Gene induced by kss1 activation | log2fold | Padj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tA(AGC)H | 4.1708989 | 6.03E-06 | BAR1 | 1.1436297 | 4.95E-20 |

| tR(ACG)L | 3.8537665 | 1.16E-10 | OCH1 | 1.1435083 | 5.39E-14 |

| tH(GUG)E2 | 3.6450963 | 3.62E-13 | YGR161W-C | 1.1408111 | 5.06E-08 |

| tG(GCC)P2 | 3.3023263 | 4.20E-05 | RGC1 | 1.1395979 | 5.47E-18 |

| FUS1 | 2.5566166 | 1.48E-27 | ELO1 | 1.1389929 | 2.78E-12 |

| CDA2 | 2.3730789 | 0.0014754 | FMP46 | 1.1376637 | 3.29E-11 |

| PRM1 | 2.183661 | 1.78E-21 | OSW5 | 1.1362377 | 5.12E-10 |

| SUF7 | 2.0777733 | 4.76E-06 | APD1 | 1.1344562 | 1.90E-12 |

| tA(AGC)P | 2.0371585 | 1.44E-07 | YOR011W-A | 1.1302885 | 0.0349305 |

| YER135C | 2.0229276 | 6.85E-05 | CAT2 | 1.1117949 | 4.05E-05 |

| YLR296W | 1.9903386 | 0.0003315 | MNN4 | 1.1084893 | 9.00E-10 |

| YMR175W-A | 1.9291227 | 6.65E-05 | YBL039W-A | 1.102614 | 3.31E-09 |

| KAR4 | 1.8828429 | 2.38E-36 | RIM4 | 1.10032 | 8.47E-16 |

| ASG7 | 1.7572425 | 4.31E-16 | MET28 | 1.0958 | 0.0007828 |

| tK(UUU)L | 1.7257316 | 0.0027961 | PEX27 | 1.0941917 | 1.56E-10 |

| YLR456W | 1.6366162 | 2.73E-06 | ARR2 | 1.0932108 | 0.0001766 |

| TGA1 | 1.6139742 | 0.0076652 | JEN1 | 1.0899823 | 1.57E-06 |

| YKL107W | 1.5907527 | 9.05E-09 | YET3 | 1.0862444 | 6.60E-07 |

| HED1 | 1.5715127 | 0.006767 | FLO11 | 1.0832116 | 2.07E-08 |

| YIL086C | 1.4693027 | 0.0002468 | PEX9 | 1.0822863 | 0.0004574 |

| YPR108W-A | 1.4417738 | 0.0289661 | SCS22 | 1.0771363 | 3.87E-11 |

| YBR209W | 1.4402674 | 0.0009669 | YPL264C | 1.0731233 | 6.82E-07 |

| SPO20 | 1.3904975 | 1.31E-05 | IML2 | 1.0729437 | 4.03E-11 |

| SPO11 | 1.3817056 | 2.00E-10 | tL(UAG)L1 | 1.0722984 | 2.10E-05 |

| YFL040W | 1.3352169 | 4.07E-08 | YLR281C | 1.0722403 | 2.44E-05 |

| PHO23 | 1.3122248 | 5.82E-28 | PBN1 | 1.0717121 | 8.65E-18 |

| YKU70 | 1.3092492 | 1.55E-07 | LPP1 | 1.0715161 | 2.79E-14 |

| YGR050C | 1.3040968 | 1.86E-06 | RMI1 | 1.0701997 | 6.51E-10 |

| WIP1 | 1.3033271 | 0.0001059 | YJR011C | 1.0685881 | 0.0090815 |

| HXT6 | 1.2909954 | 0.0024815 | YGL230C | 1.067546 | 0.0190732 |

| DAL4 | 1.2836711 | 2.22E-10 | YHR180W | 1.0610996 | 8.80E-08 |

| SDD1 | 1.2708218 | 2.31E-06 | YPL060C-A | 1.0575971 | 0.0390114 |

| YHR054C | 1.2695696 | 5.53E-05 | YEL014C | 1.0544735 | 0.0006101 |

| PIR5 | 1.2679679 | 0.0005466 | KEG1 | 1.0510359 | 6.13E-05 |

| tK(UUU)P | 1.2460022 | 0.0184187 | PEX29 | 1.0469406 | 1.05E-17 |

| LSB5 | 1.2167549 | 3.17E-26 | SPO73 | 1.0407879 | 7.96E-08 |

| MATALPHA2 | 1.2159332 | 0.0013187 | YIL082W-A | 1.0377157 | 1.03E-13 |

| HMRA1 | 1.2126029 | 0.0010577 | YOR343C | 1.0291711 | 0.0004591 |

| STE18 | 1.2091624 | 2.04E-05 | COX7 | 1.0205492 | 0.0019373 |

| MDM31 | 1.2008456 | 1.72E-27 | YEL009C-A | 1.0184729 | 0.0033053 |

| PLM2 | 1.1984114 | 1.21E-08 | PEX22 | 1.017867 | 0.0043155 |

| SPR28 | 1.1981751 | 6.57E-05 | tV(AAC)O | 1.0176917 | 0.0217544 |

| GEX2 | 1.1979436 | 7.85E-09 | SKN1 | 1.0152587 | 3.16E-05 |

| EMI1 | 1.1949726 | 0.0002045 | COQ6 | 1.0151778 | 3.66E-17 |

| COQ11 | 1.1923294 | 2.61E-14 | ETP1 | 1.0142717 | 1.44E-10 |

| snR17a | 1.1893315 | 0.0023669 | YDL009C | 1.0124019 | 0.0085531 |

| YIL166C | 1.1739644 | 2.00E-07 | MST1 | 1.0116936 | 5.32E-15 |

| YAR023C | 1.1699005 | 0.0214896 | RSB1 | 1.010971 | 1.40E-15 |

| tK(UUU)D | 1.1656688 | 0.0478947 | YDR286C | 1.0086972 | 6.18E-11 |

| SDH8 | 1.1584218 | 8.83E-12 | YMR31 | 1.0073502 | 9.98E-08 |

| YPR003C | 1.1497148 | 3.66E-12 | UBA3 | 1.0059366 | 8.37E-12 |

| YNL019C | 1.1492374 | 2.02E-06 | YEF1 | 1.0045428 | 5.35E-08 |

| tH(GUG)M | 1.1457046 | 0.0450168 | HEM25 | 1.003729 | 1.15E-11 |

| ERS1 | 1.1438957 | 1.57E-05 | BNS1 | 1.0022277 | 0.0005341 |

TABLE 6:

Enrichment of GO terms for genes listed in Table 5.

| Gene ontology term | Cluster frequency | Genome frequency | Corrected P-value | FDR | False positive | Genes annotated to the term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sexual reproduction | 14 of 108 genes, 14.8% | 395 of 7166 genes, 5.5% | 0.07116 | 46.00% | 0.46 | STE18, CDA2, RIM4, SPO20, EMI1,PRM1, SPO73, KAR4, BNS1, BAR1, SPR28,HED1, ASG7, FUS1, SPO11 |

| modified amino acid transport | 3 of 108 genes, 2.8% | 9 of 7166 genes, 0.1% | 0.0733 | 24.00% | 0.48 | ERS1, YIL166C, GEX2 |

DISCUSSION

Here, we have assessed the impact of signaling cross-talk on MAPK activation, translocation, and transcription. Specifically, we examined the role of shared and redundant signaling components in cells exposed to two simultaneous inputs. To assess the contributions of the Sln1 and Sho1 branches of the HOG pathway, we determined how each branch affects activation of all three MAPKs, in response to pheromone and salt. We first determined that the Sho1 branch dictates the timing, while the Sln1 branch dictates the amplitude, of Hog1 activation by salt. After a delay, Hog1 is translocated into the nucleus. Further, we determined that the Sln1 branch, but not the Sho1 branch, limits Hog1-mediated transcription. Thus, there are functional differences between the two branches of the HOG pathway, and these differences are most evident at the level of gene expression. We also evaluated the effect of cross-talk between the HOG and mating pathways. When we simultaneously activated the mating pathway and the Sho1 branch of the HOG pathway, Kss1 up-regulated mating pathway transcription and down-regulated HOG pathway transcription. Thus, Sho1 promotes, and Ssk1 limits, cross-pathway signaling by Kss1.

Having established that Kss1 links the two MAPK pathways, we undertook an analysis of Kss1-dependent transcription. A previous genome-wide comparison of fus3Δ and kss1Δ cells revealed that the transcriptomic profiles of the two mutants are highly similar after pheromone induction (Breitkreutz et al., 2001). However, later work revealed that Kss1 and Fus3 are partitioned differently in the cell; whereas Kss1 is concentrated in the nucleus, Fus3 is distributed throughout the cell and nucleus; moreover, upon pheromone induction, Kss1 translocates into the cytoplasm while Fus3 becomes concentrated at the mating projection (Choi et al., 1999; Van Drogen and Peter, 2001; Pelet, 2017). Collectively, these studies showed that Kss1 and Fus3 have different spatial distributions and patterns of activation, raising the possibility that these MAPKs have distinct roles in transcription regulation. Our evaluation of the Kss1-dependent transcriptome revealed induction of a subset of genes related to meiotic cell cycle and sporulation as well as mating, which are crucial to both pathways. This finding reveals that Kss1 has a unique role in signal transduction, and in this way contributes to fundamental biological processes needed to help yeast cells adapt to environment changes.

Given the importance of pathway integration, it is essential to distinguish processes that are specific to the signaling pathways under investigation. To that end, our analysis was informed by past studies of costimulation. A previous study used GFP and RFP reporters to simultaneously monitor transcription in response to mating pheromone and the osmolyte sorbitol, respectively (McClean et al., 2007); however, it was later determined that sorbitol in combination with pheromone causes substantial cell death, and the resulting autofluorescence was misinterpreted as signal coming from the RFP reporter (Patterson et al., 2010). We avoided this artifact by using KCl, which is far less toxic than sorbitol in the presence of pheromone (Nagiec and Dohlman, 2012).

Our focus on cross-pathway coordination complements prior efforts to understand the mechanisms of pathway fidelity. It has long been known that Hog1 transmits the osmostress signal, and when it is absent allows inappropriate activation of the mating response by salt stress (Hall et al., 1996; O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 1998; Westfall and Thorner, 2006; Patterson et al., 2010). This could result from a loss of pathway insulation, for example by allowing an upstream kinase to bind to, and activate, components of an alternative pathway. One recent study showed an important role of upstream kinases in limiting such cross-pathway activation. In that analysis, Saito and colleagues showed that the MAP3Ks unique to the HOG pathway (Ssk2/22) phosphorylate the two sites in Pbs2 necessary for full activation, while the shared MAP3K Ste11 phosphorylates only one of the two sites in Pbs2. Only upon osmotic stress is the monophosphorylated form of Pbs2 competent to transmit the signal to Hog1 (Tatebayashi et al., 2020). Thus, even if pheromone triggers phosphorylation of Pbs2 by Ste11, osmotic stress is still needed for HOG pathway activation.

Another way that Hog1 limits cross-talk is through feedback phosphorylation of components in other pathways. Indeed, one early study showed that Hog1 activation dampens the pheromone response through feedback phosphorylation of the shared component Ste50, leading to diminished activation of the mating pathway (Hao et al., 2008). Conversely, phosphorylation of Ste50 by Fus3 down-regulates the HOG pathway, by dissociating Ste50 from the osmosensor Opy2 (Yamamoto et al., 2010).

Another study used untargeted metabolomics to show that salt stress leads to an increase in 2-hydroxy carboxylic acid derivatives of branched chain amino acids, and that the production of these “second messenger” metabolites requires Hog1 catalytic activity. Activation of Hog1, or addition of the Hog1-regulated metabolites, promotes the phosphorylation of the mating pathway G protein (Shellhammer et al., 2017), which in turn leads to attenuated signaling through the effector MAPK, Fus3 (Hao et al., 2012; Clement et al., 2013; Isom et al., 2013).

Collectively, past and present studies indicate that there are multiple targets of cross-pathway communication, acting throughout the signal transduction cascade. The work presented here reveals a new and unappreciated role for Kss1 in coordinating the response to pheromone and salt stress. Due to the similarities in MAPK networks and functional conservation of these kinase proteins, our work is likely to inform mechanisms of cross-talk in mammals as well as in other fungi, including pathogenic species, all having a high similarity of organization and function of key pathway components.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Request a protocol through Bio-protocol.

Strain construction

All strains were derived from BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0; “wild type”) and transformed by the lithium acetate method (Gietz and Woods, 2002). The ssk1Δ strain was created using primer-guided PCR amplification of the G418 drug resistance gene and homologous recombination as described previously (Janke et al., 2004), in which the SSK1 open reading frame was replaced by the KanMX6 marker, originating from the pFA6a-KanMX6 plasmid (Janke et al., 2004). We elected to delete SSK1 because SLN1 is an essential gene. The sho1ΔΔ strain was created using primer-guided PCR and homologous recombination to replace SHO1, on both copies of chromosome V, with URA3, originating from the pCORE-UK (COunterselectable marker and REporter gene, KlURA3 and KanMX4) (Addgene; # 72231) plasmid.

The strains for phos-tag immunoblotting Kss1-9xMyc and Fus3-9xMyc were derived from BY4741, ssk1Δ, and sho1ΔΔ. The 9xMyc-tagged strains were generated by homologous recombination of a PCR-amplified 9xMyc cassette at the C-terminus of the KSS1 or FUS3 ORF. This cassette contains the hygromycin B resistance gene, originating from the plasmid pYM20 (pYM20-9xMyc-hphNT1) (Janke et al., 2004).

The strains for single-cell microscopy were derived from BY4741, ssk1Δ and sho1ΔΔ, expressing HTB2-GFP (Huh et al., 2003) and HOG1-mRUBY2 (this work). GFP was introduced by homologous recombination following PCR amplification of the HTB2 ORF from the GFP-tagged library strain (Huh et al., 2003). HOG1-mRUBY2 was introduced by homologous recombination following PCR amplification of the mRUBY-hphMX6 cassette containing the hygromycin B resistance gene, originating from the mRUBY-hphMX6 fragment (Li et al., 2018).

All strains were validated using PCR and Sanger sequencing or Oxford Nanopore Technology with custom analysis and annotation (performed by Azenta, Chelmsford, MA or Plasmidsaurus, Eugene, OR). All primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Yeast cell culture

Strains were cultured using standard methods and media. Briefly, strains were struck out on SCD (synthetic complete or without amino acids for selection, 2% dextrose and 10% agar) or YPD (yeast extract, peptone, 2% dextrose, and 10% agar) plates and grown at 30°C for 3–4 d. Individual colonies were picked and cultured overnight in 3 ml selection medium or YPD medium (without agar) to saturation. Cells were diluted 1:100, grown for 8 h, and diluted to OD600nm = 0.001 for overnight growth. The following day, experiments were conducted once the cell culture reached OD600nm ∼0.8–1.

Phos-tag sample collection, gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotting

Cells expressing Hog1, Fus3-9xMYC, and Kss1-9xMYC were collected and total protein was quantified as described previously (English et al., 2015; Shellhammer et al., 2019). Briefly, cells were grown in SCD medium to OD600nm ∼0.9 and 5 ml of cells were collected and quenched in 5% (vol/vol) TCA on ice. The remaining cells were subjected to 3 µM α-factor pheromone, 350 mM KCl or a combination of the two treatments. Then, 9 ml of cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 2 min at 4°C, washed once with 10 mM NaN3, and recollected by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 2 min. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C until use.

The cell lysates were prepared using conditions optimized for phos-tag SDS–PAGE as described previously (English et al., 2015). Briefly, cell pellets were thawed on ice and resuspended in ice-cold TCA buffer (Lee and Dohlman, 2008) without EDTA (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10% TCA, 25 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.0). Cells were vortexed quickly until completely dissolved, then collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Pellets were reconstituted in resuspension buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 3% SDS, pH 11.0), heated at 99°C for 10 min, cooled to room temperature for 10 min, and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 1 min. Supernatants were then transferred to new tubes and 5 µl were used in a Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad; # 5000112) carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance values were compared against BSA standards prepared in resuspension buffer.

Lysates were normalized with resuspension buffer to 1.5 µg/µl, mixed 1:1 with 2x SDS sample buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 200 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, pH 8.5), and used immediately or stored at −80°C. Samples were heated at 70°C for 10 min prior to loading.

The dual phosphorylated (activated) and nonphosphorylated (inactive) kinases were resolved and visualized by their different mobility states using 8% acrylamide Bis-Tris SDS–PAGE gels containing 20–50 nM phos-tag acrylamide reagent (Fujifilm; # AAL107). Hog1 was detected using a Hog1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; # sc-165978; 1:5000) and a donkey-anti mouse horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch; # 715-035-150; 1:10,000). Fus3-9xMyc and Kss1-9xMyc phosphorylation was detected by Myc antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; # 9B11; 1: 5000), and a donkey-anti mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Promega; # W4021; 1:10,000). Secondary antibodies were visualized using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad; # 1705061) and a Bio-Rad Chemidoc Touch Imaging System. Band intensities were normalized and quantified using the ImageLab software (Bio-Rad, version 6.0.1). Because each lane was quantified as the proportion of total detected protein that is phosphorylated, a loading control is not needed.

Population-based transcriptional reporter assay

To monitor MAPK-mediated transcription, we utilized a reporter system consisting of LacZ expressed from an osmostress-induced promoter (from CRE) for the HOG pathway (Tatebayashi et al., 2006), and the pheromone-induced promoter (from FUS1) for the mating pathway (Hoffman et al., 2002). Wild-type, ssk1Δ, sho1ΔΔ, kss1Δ, ssk1Δkss1Δ and sho1ΔΔkss1Δ strains were transformed with pRS423-PFUS1-LacZ or pRS423-PCRE-LacZ. Three colonies from each transformation were grown at 30°C to saturation overnight in selection medium, then diluted to 1:100 the following day and grown to OD600nm ∼1–1.5. These cultures were again diluted to OD600nm = 0.002–0.004 and grown overnight to OD600nm ∼0.8–1. Ninety or 75 µl of cells were added per well, in duplicate rows, to black clear-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning Costar; # 3599) containing 10 µl of 10x stocks of serially diluted α factor mating pheromone prepared in selection media, or 25 µl of 4x stocks of diluted KCl prepared in selection media, with one well per row containing 10 or 25 µl of selection media only. PFUS1-LacZ and PCRE-LacZ assays were carried out as described previously (Hoffman et al., 2002). Briefly, samples were incubated for 1.5 h at 30°C. The OD600 for each well was measured to determine cell density after which 100 µM fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside (FDG) solution (135 mM PIPES, 0.25% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 0.5 mM FDG, pH 7.2) was added to each well. After 1.5 h (PFUS1-LacZ) or 4.5 h (PCRE-LacZ) at 37°C, fluorescence was measured using a Molecular Devices Spectramax i3x plate reader or a CLARIOstar Plus microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm, and emission wavelength of 580 nm.

For data analysis and presentation, raw fluorescence values from each well were normalized to the number of cells in that well (represented by the OD600nm) using the shorthand Taylor Series 1/(1+x) where x = OD600. Normalized values of each technical duplicate were averaged. Finally, each well was normalized as a percent of the average fluorescence value in the wild-type strain. Dose–response curves were fitted to the data using a nonlinear Boltzmann function with least squares regression in GraphPad Prism 8.

Single-cell microscopy assay and analysis

As a high-throughput screening method, we measured and tracked mRuby fluorescence in individual cells treated with KCl or mating pheromone on 96-well glass bottom black plates (Cellvis; # P96-1.5H-N). The 96-well plate was coated in 100 µl filter-sterilized concanavalin A (ConA) (1 mg/ml in water) for 1.5 h at room temperature to adhere cells to the bottom of the well. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer and the number of cells per ml was calculated using the formula of (cell number) * 5 * dilution factor * 1000. Approximately 30,000 cells were plated in each well and centrifuged at 500 × g for 2 min. Cells were maintained at 30°C for the duration of the experimental set up and imaging. The cells were imaged with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-2 inverted microscope with a 20x air objective, an integrated perfect focus system, and an ORCA-Flash 4.0 camera (Hamamatsu). Image acquisition was performed using the automatic ND acquisition program in the NIS-elements Advanced Research software (Nikon, NIS-Elements AR 5.30.05 Build 1560). An LED light source (Lumencor, SPECTRA iii 8-nii-xs) was used to acquire bright field images with an exposure time of 6 ms. The LED light with excitation filters excited GFP at 460 nm for 100 ms and mRuby at 565 nm for 1 s at 100% laser power. One round of cell images was taken as time = 0 before stimuli were added. Upon addition of stimuli (350 mM KCl or costimulation of 350 mM KCl and 30 µM pheromone), images were taken every 2 min. Images were processed using Cellprofiler (version 4.2.5, Windows) with a customized pipeline (this work, Supplemental Materials). Specifically, bright field images were used to define the total area of the cell, and GFP images were used to define the nucleus. Then, mRuby images were used to track the location of Hog1. The fraction of nuclear Hog1 was calculated using the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic mRuby signal. Background signal was corrected by subtracting lowest fluorescent signals (mRuby channel) on the perimeter of the defined cell area. All processed images were pooled and analyzed using a customized R script (this work, Supplemental Materials). Fluorescent signal at every timepoint was normalized against pretreatment fluorescent signal. Three-way ANOVA was performed to determine the significance between different strains and treatments.

Sample preparation for RNA-seq

Cells were grown from a single colony to saturation overnight. Next day, cells were diluted and grown to OD600nm = 0.7 (∼107 cells/ml). Then, cells were treated with 350 mM KCl, 30 µM mating pheromone or the combination of both for 15 min. At the 13-min mark, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 2 min and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored on dry ice. Frozen cell pellets were submitted to Azenta Life Science on dry ice for RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing (150 × 2 bp) and data analysis. Briefly, RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit/DNase digestion kit from Qiagen. RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and RNA integrity was checked using Agilent TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #4456740), was added to normalized total RNA prior to library preparation following manufacturer's protocol.

The RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina, using manufacturer's instructions (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Briefly, mRNAs were initially enriched with Oligo d(T) beads. Enriched mRNAs were fragmented for 15 min at 94°C. First strand and second strand cDNA were subsequently synthesized. cDNA fragments were end repaired and adenylated at 3′ ends, and universal adapters were ligated to cDNA fragments, followed by index addition and library enrichment by PCR with limited cycles. The sequencing libraries were validated on the Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and quantified by using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as well as by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA).

The sequencing libraries were clustered on one flowcell lane. After clustering, the flowcell was loaded on the Illumina instrument according to manufacturer's instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2 × 150 bp Paired End (PE) configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the Control software. Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from the sequencer were converted into fastq files and de-multiplexed using Illumina's bcl2fastq 2.17 software. One mismatch was allowed for index sequence identification.

Sequence reads were trimmed to remove possible adapter sequences and nucleotides with poor quality using Trimmomatic v.0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014). The trimmed reads were mapped to the S. cerevisiae S288c reference genome available on ENSEMBL using the STAR aligner v.2.5.2b (Dobin et al., 2013). The STAR aligner is a splice aligner that detects splice junctions and incorporates them to help align the entire read sequences. BAM files were generated as a result of this step. Unique gene hit counts were calculated by using featureCounts from the Subread package v.1.5.2 (Liao et al., 2014). The hit counts were summarized and reported using the gene_name feature in the annotation file. Only unique reads that fell within exon regions were counted. If a strandspecific library preparation was performed, the reads were strand-specifically counted. After extraction of gene hit counts, the gene hit counts table was used for downstream differential expression analysis. Using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014), a comparison of gene expression between the customer-defined groups of samples was performed. The Wald test was used to generate P-values and log2 fold changes. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > 1 were called as DEGs for each comparison.

The volcano plot of DEGs were generated by using SRplot, at https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en (Tang et al., 2023) Genetic ontology analysis was done using GO Term Finder tool at https://www.yeastgenome.org/goTermFinder (GO: biological processes, false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.01, corrected P value < 0.05).

Code availability

Customized R script for analysis of microscopy data is provided in Supplemental Materials.

Data availability

All RNA-seq data are available on Gene Expression Omnibus with reference number GSE270781.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funded by NIH grants R35-GM118105 (H.G.D.), DP2-GM136653 (W.R.L.), and T32-GM008570 (S.Z). W.R.L. acknowledges additional support from the Searle Scholars program, the Beckman Young Investigator Program, and the Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering. The authors thank Pengda Liu for feedback on the manuscript.

Abbreviations used:

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- FDG

fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GO

gene ontology

- HOG

high osmolarity glycerol

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SCD

synthetic complete dextrose

- YPD

yeast extract, peptone, dextrose.

Footnotes

1The standard lab strain BY4741 contains two copies of chromosome V, necessitating deletion of two copies of SHO1.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www .molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E24-06-0270) on July 31, 2024.

REFERENCES

- Albertyn J, Hohmann S, Prior BA (1994). Characterization of the osmotic-stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: osmotic stress and glucose repression regulate glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase independently. Curr Genet 25, 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell L (2005). A walk-through of the yeast mating pheromone response pathway. Peptides (NY) 26, 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell L, Cook JG, Voora D, Baggott DM, Martinez AR, Thorner J (1998). Repression of yeast Ste12 transcription factor by direct binding of unphosphorylated Kss1 MAPK and its regulation by the Ste7 MEK. Genes Dev 12, 2887–2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz A, Boucher L, Tyers M (2001). MAPK specificity in the yeast pheromone response independent of transcriptional activation. Curr Biol 11, 1266–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi AP, Kaplan T, Liu Y, Habib N, Regev A, Friedman N, O'Shea EK (2008). Structure and function of a transcriptional network activated by the MAPK Hog1. Nat Genet 40, 1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causton HC, Ren B, Koh SS, Harbison CT, Kanin E, Jennings EG, Lee TI, True HL, Lander ES, Young RA (2001). Remodeling of yeast genome expression in response to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell 12, 323–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RE, Thorner J (2007). Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways: Lessons learned from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773, 1311–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K-Y, Kranz JE, Mahanty SK, Park K-S, Elion EA (1999). Characterization of Fus3 localization: Active Fus3 localizes in complexes of varying size and specific activity. Mol Biol Cell 10, 1553–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement ST, Dixit G, Dohlman HG (2013). Regulation of yeast G protein signaling by the kinases that activate the AMPK homolog Snf1. Sci Signal 6, ra78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JG, Bardwell L, Thorner J (1997). Inhibitory and activating functions for MAPK Kss1 in the S. cerevisiae filamentous-growth signalling pathway. Nature 390, 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English JG, Shellhammer JP, Malahe M, McCarter PC, Elston TC, Dohlman HG (2015). MAPK feedback encodes a switch and timer for tunable stress adaptation in yeast. Sci Signal 8, ra5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrigno P, Posas F, Koepp D, Saito H, Silver PA (1998). Regulated nucleo/cytoplasmic exchange of HOG1 MAPK requires the importin beta homologs NMD5 and XPO1. EMBO J 17, 5606–5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatauer LJ, Zadeh SF, Bardwell L (2005). Mitogen-activated protein kinases with distinct requirements for Ste5 scaffolding influence signaling specificity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 25, 1793–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner A, Nasmyth K, Ammerer G (1992). Signal transduction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires tyrosine and threonine phosphorylation of FUS3 and KSS1. Genes Dev 6, 1280–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G, Botstein D, Brown PO (2000). Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell 11, 4241–4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA (2002). Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol 350, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JP, Cherkasova V, Elion E, Gustin MC, Winter E (1996). The osmoregulatory pathway represses mating pathway activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae : Isolation of a FUS3 mutant that is insensitive to the repression mechanism. Mol Cell Biol 16, 6715–6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao N, Behar M, Parnell SC, Torres MP, Borchers CH, Elston TC, Dohlman HG (2007). A systems-biology analysis of feedback inhibition in the Sho1 osmotic-stress-response pathway. Curr Biol 17, 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao N, Yildirim N, Nagiec MJ, Parnell SC, Errede B, Dohlman HG, Elston TC (2012). Combined computational and experimental analysis reveals mitogen-activated protein kinase–mediated feedback phosphorylation as a mechanism for signaling specificity. Mol Biol Cell 23, 3899–3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao N, Zeng Y, Elston TC, Dohlman HG (2008). Control of MAPK specificity by feedback phosphorylation of shared adaptor protein Ste50. J Biol Chem 283, 33798–33802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman GA, Garrison TR, Dohlman HG (2002). Analysis of RGS proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol 344, 617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsa C-G, Brandt EV, Thevelein J, Hohmann S, Prior BA (1998). Role of trehalose in survival of Saccharomyces cerevisiae under osmotic stress. Microbiology (N Y) 144, 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh W-K, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O'Shea EK (2003). Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425, 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom DG, Sridharan V, Baker R, Clement ST, Smalley DM, Dohlman HG (2013). Protons as second messenger regulators of G protein signaling. Mol Cell 51, 531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, Moreno-Borchart A, Doenges G, Schwob E, Schiebel E, et al. (2004). A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21, 947–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Dohlman HG (2008). Coactivation of G protein signaling by cell-surface receptors and an intracellular exchange factor. Curr Biol 18, 211–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J (2010). Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 141, 1117–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Giardina DM, Siegal ML (2018). Control of nongenetic heterogeneity in growth rate and stress tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by cyclic AMP-regulated transcription factors. PLoS Genet 14, e1007744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W (2014). featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani HD, Styles CA, Fink GR (1997). MAP kinases with distinct inhibitory functions impart signaling specificity during yeast differentiation. Cell 91, 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Saito H (1994). A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature 369, 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleri S, Ge Q, Hackett EA, Wang Y, Dohlman HG, Errede B (2004). Persistent activation by constitutive Ste7 promotes Kss1-mediated invasive growth but fails to support Fus3-dependent mating in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 24, 9221–9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean MN, Mody A, Broach JR, Ramanathan S (2007). Cross-talk and decision making in MAP kinase pathways. Nat Genet 39, 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbacher M, Lee SS, Yaakov G, Nadal-Ribelles M, de Nadal E, van Drogen F, Posas F, Peter M, Claassen M (2023). Positive feedback induces switch between distributive and processive phosphorylation of Hog1. Nat Commun 14, 2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murguía JR, Bellés JM, Serrano R (1996). The yeast HAL2 nucleotidase is an in vivo target of salt toxicity. J Biol Chem 271, 29029–29033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagiec MJ, Dohlman HG (2012). Checkpoints in a yeast differentiation pathway coordinate signaling during hyperosmotic stress. PLoS Genet 8, e1002437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A, Yamamoto K, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H, Saito H, Tatebayashi K (2016). Scaffold protein Ahk1, which associates with Hkr1, Sho1, Ste11, and Pbs2, inhibits cross talk signaling from the Hkr1 osmosensor to the Kss1 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol 36, 1109–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke SM, Herskowitz I (1998). The Hog1 MAPK prevents cross talk between the HOG and pheromone response MAPK pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 12, 2874–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke SM, Herskowitz I (2004). Unique and redundant roles for HOG MAPK pathway components as revealed by whole-genome expression analysis. Mol Biol Cell 15, 532–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JC, Klimenko ES, Thorner J (2010). Single-cell analysis reveals that insulation maintains signaling specificity between two yeast MAPK pathways with common components. Sci Signal 3, ra75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelet S (2017). Nuclear relocation of Kss1 contributes to the specificity of the mating response. Sci Rep 7, 43636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas F, Saito H (1998). Activation of the yeast SSK2 MAP kinase kinase kinase by the SSK1 two-component response regulator. EMBO J 17, 1385–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas F, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Maeda T, Witten EA, Thai TC, Saito H (1996). Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the SLN1-YPD1-SSK1 “two-component” osmosensor. Cell 86, 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser V, Raitt DC, Saito H (2003). Yeast osmosensor Sln1 and plant cytokinin receptor Cre1 respond to changes in turgor pressure. J Cell Biol 161, 1035–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rep M, Krantz M, Thevelein JM, Hohmann S (2000). The transcriptional response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to osmotic shock. Hot1p and Msn2p/Msn4p are required for the induction of subsets of high osmolarity glycerol pathway-dependent genes. J Biol Chem 275, 8290–8300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh W, Flatauer LJ, Bardwell AJ, Bardwell L (2001). Specificity of MAP kinase signaling in yeast differentiation involves transient versus sustained MAPK activation. Mol Cell 8, 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Posas F (2012). Response to hyperosmotic stress. Genetics 192, 289–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellhammer JP, Morin-Kensicki E, Matson JP, Yin G, Isom DG, Campbell SL, Mohney RP, Dohlman HG (2017). Amino acid metabolites that regulate G protein signaling during osmotic stress. PLoS Genet 13, e1006829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellhammer JP, Pomeroy AE, Li Y, Dujmusic L, Elston TC, Hao N, Dohlman HG (2019). Quantitative analysis of the yeast pheromone pathway. Yeast 36, 495–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Tatebayashi K, Nishimura A, Yamamoto K, Yang H-Y, Saito H (2014). Yeast osmosensors Hkr1 and Msb2 activate the Hog1 MAPK cascade by different mechanisms. Sci Signal 7, ra21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Chen M, Huang X, Zhang G, Zeng L, Zhang G, Wu S, Wang Y (2023). SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS One 18, e0294236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi K, Tanaka K, Yang H-Y, Yamamoto K, Matsushita Y, Tomida T, Imai M, Saito H (2007). Transmembrane mucins Hkr1 and Msb2 are putative osmosensors in the SHO1 branch of yeast HOG pathway. EMBO J 26, 3521–3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi K, Yamamoto K, Nagoya M, Takayama T, Nishimura A, Sakurai M, Momma T, Saito H (2015). Osmosensing and scaffolding functions of the oligomeric four-transmembrane domain osmosensor Sho1. Nat Commun 6, 6975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi K, Yamamoto K, Tanaka K, Tomida T, Maruoka T, Kasukawa E, Saito H (2006). Adaptor functions of Cdc42, Ste50, and Sho1 in the yeast osmoregulatory HOG MAPK pathway. EMBO J 25, 3033–3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi K, Yamamoto K, Tomida T, Nishimura A, Takayama T, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H, Adachi-Akahane S, Tokunaga Y, Saito H (2020). Osmostress enhances activating phosphorylation of Hog1 MAP kinase by mono-phosphorylated Pbs2 MAP2K. EMBO J 39, e103444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Drogen F, Peter M (2001). MAP kinase dynamics in yeast. Biol Cell 93, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall PJ, Thorner J (2006). Analysis of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling specificity in response to hyperosmotic stress: Use of an analog-sensitive HOG1 allele. Eukaryot Cell 5, 1215–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters MJ, Pryciak PM (2018). Analysis of the thresholds for transcriptional activation by the yeast MAP kinases Fus3 and Kss1. Mol Biol Cell 29, 669–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortzel I, Seger R (2011). The ERK cascade: Distinct functions within various subcellular organelles. Genes Cancer 2, 195–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Tatebayashi K, Saito H (2016). Binding of the extracellular eight-cysteine motif of Opy2 to the putative osmosensor Msb2 is essential for activation of the yeast high-osmolarity glycerol pathway. Mol Cell Biol 36, 475–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Tatebayashi K, Tanaka K, Saito H (2010). Dynamic control of yeast MAP kinase network by induced association and dissociation between the Ste50 scaffold and the Opy2 membrane anchor. Mol Cell 40, 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All RNA-seq data are available on Gene Expression Omnibus with reference number GSE270781.