Abstract

The locus coeruleus (LC)-amygdala circuit is implicated in playing a key role in responses to emotionally arousing stimuli and in the manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here, we examined changes in gene expression of a number of important mediators of the LC-amygdala circuitry in the inhibition avoidance model of PTSD. After testing for basal acoustic startle response (ASR), rats were exposed to a severe footshock (1.5 mA for 10 s) in the inhibitory avoidance apparatus. They were given contextual situational reminders every 5 day for 25 days. Controls were treated identically but with the footshock inactivated. Animals were re-tested on second ASR and decapitated 1 h later. The shock group had enhanced hyperarousal and several changes in gene expression compared to controls. In the LC, mRNA levels of norepinephrine (NE) biosynthetic enzymes (TH, DBH), NE transporter (NET), NPY receptors (Y1R, Y2R), and CB1 receptor of endocannabinoid system were elevated. In the basolateral amygdala (BLA), there were marked reductions in gene expression for CB1, and especially Y1R, with rise for corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) system (CRH, CRH receptor 1), and no significant changes in the central amygdala. Our results suggest a fast forward mechanism in the LC-amygdala circuitry in the shock group.

Keywords: Cannabinoid receptor, Corticotropin-releasing hormone, Neuropeptide Y, Neuropeptide Y1 and Y2 receptors, Norepinephrine transporter, Tyrosine hydroxylase

Introduction

It has been a great honor and pleasure to collaborate closely with Richard Kvetnansky for close to 30 years. His work on the effects of stress on the catecholaminergic system is classical, from his original papers from the 1970s with Irv Kopin until shortly before his death. His enthusiasm, organization, attention to detail, and comprehensive views on stress are legendary.

Richard Kvetnansky’s work was among the first to reveal effects of stress on tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene expression in the locus coeruleus (LC) (Mamalaki et al. 1992). Using in situ hybridization, they demonstrated that TH gene expression in the LC was rapidly elevated by single exposure to immobilization stress and that the levels were higher following seven daily consecutive exposures to immobilization stress. Among his many contributions to the field of stress research, Dr. Kvetnansky was fascinated by the way prior exposure to one stressor influenced the subsequent response to a homotypic or heterotypic stressor. Thus, we are happy to provide work to this special issue in his memory on the inhibitory avoidance with reminders post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) model and its long-term effect to enhanced startle responses and changes in gene expression in the LC-amygdala circuit by possible feed forward mechanism.

The LC is the origin of the majority of noradrenergic neurons in the brain. It plays an important role in a variety of brain functions and behaviors that include vigilance, attention, arousal, memory acquisition, locomotor control, and response to stress (Aston-Jones et al. 1996; Morilak et al. 2005; Valentino and Van Bockstaele 2008; Sara 2009; Berridge et al. 2012). These tightly clustered neurons of norepinephrine (NE)-synthesizing cells in the pons innervate much of the brain. Many LC neurons have collateralized projections to functionally diverse targets. The LC is the primary source of NE in the forebrain and the sole source of NE in the cortex and hippocampus, as well as the cerebellum [reviewed in (Valentino and Van Bockstaele 2008)].

Dysregulation of the central noradrenergic system is a core feature of PTSD. Patients with PTSD have elevated norepinephrine (NE) levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is correlated with severity of the disease (Geracioti et al. 2001). The exaggerated noradrenergic activity has been observed primarily in response to a variety of trauma-associated stimuli rather than at resting conditions (Southwick et al. 1999; Strawn and Geracioti 2008) and is suggested to be involved in hyperarousal and re-experiencing symptom clusters of PTSD. In addition, PET scans showed reduced norepinephrine transporter (NET) availability in the LC was associated with anxious and arousal symptoms, notably with hypervigilance (Pietrzak et al. 2013).

The amygdala is an important target for LC neurons in mediating fear and arousal responses. Amygdalar NE plays a key role in regulation of neuronal responses to emotionally arousing stimuli, and in memory consolidation of emotionally charged events (Flavin and Winder 2013; Kravets et al. 2015). It is major site of extra hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) with stress that can be modulated by neuropeptide Y (NPY) as well as endocannabinoids (eCB).

Our recent work demonstrates that the intranasal NPY when given after stressors in single prolonged stress model of PTSD prevented development of a wide range of behavioral and neuroendocrine response, as well as long-term activation of the LC/NE system and CRH in the amygdala (Serova et al. 2013; Laukova et al. 2014; Sabban et al. 2015). The balance between excitatory and inhibitory tone in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) with CRH and NPY is important in mediating fear and startle responses. Administration of NPY into the BLA is anxiolytic and inhibits fear-potentiated startle response, primarily via Y1 receptor (Y1R) (Gutman et al. 2008). In contrast, CRH administration into the BLA produces anxiogenic effects via CRH receptor 1 (CRHR1), which are prevented by pre-treatment with NPY (Sajdyk et al. 2004).

Several lines of evidence support the role of the eCB system as a modulator of the behavioral and physiological responses to stress (Hill and Gorzalka 2009; Ganon-Elazar and Akirav 2012; Lutz et al. 2015; Alteba et al. 2016). The eCB system consists of the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors, the eCBs [N-arachidonylethanolamine/anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)], and the enzymatic machinery for eCB degradation [fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) for AEA and the monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) for 2-AG]. Systemic or intra-BLA enhancement of eCB signaling enhances fear extinction via a CB1-dependent mechanism (Ganon-Elazar and Akirav 2012; Gunduz-Cinar et al. 2013). Here, we show increased acoustic startle and changes in gene expression of noradrenergic, NPY-ergic, CRH, and eCB systems in the LC and amygdala about a month after shock in the inhibitory avoidance with reminders model of PTSD. We discuss the possible significance within the LC-amygdala circuitry.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (55 days old, 200–220 g; Harlan, Jerusalem, Israel) were caged together (2–5 per cage) at 22 ± 2 °C under 12-h light/dark cycles (lights turned on at 7 am). Rats were allowed water and laboratory rodent chow ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the University of Haifa Ethics and Animal Care Committee and were performed in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Experimental Procedures

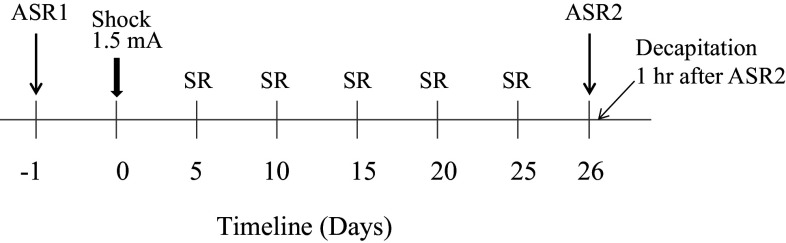

The overall experimental procedure is shown in Fig. 1. Rats (n = 24) were tested for basal acoustic startle response (ASR1). The following day, they were randomly divided into two groups. Animals in one group were subjected to inhibitory avoidance stress consisting of 1.5 mA shock for 10 s. For controls, the shock mechanism was inactivated. They were given situational reminders (SR) 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days afterward. On day 26, they were re-tested for acoustic startle response (ASR2). One hour later, animals were sacrificed, brains removed and quickly frozen in dry ice and kept at −80 °C.

Fig. 1.

The scheme of the experimental design. Rats were tested for basal response to acoustic startle (ASR1). On the next day, they received electrical shock in inhibitory avoidance apparatus. They were returned to the apparatus for 1 min 5 more times 5 days apart. On the 26th day, rats were tested again for ASR (ASR2) and sacrificed 1 h later

Acoustic Startle Response (ASR)

An acrylic animal holder (9 cm in diameter and 20 cm in length) connected to a piezoelectric accelerometer was placed in a sound proof chamber (25 × 25 × 25 cm3). A high-frequency loudspeaker inside the chamber produced both continuous background noise (68 dB) and acoustic stimuli. Illumination was provided by a white bulb located on the ceiling of the chamber. The animals were placed in the holder and a startle session started following a 5-min habituation period. Sound stimuli consisting of a 50 ms burst of 98 or 120 dB were delivered 23 times every 30 s. The background noise level of 68 dB was maintained throughout each session. The maximal amplitudes of ASR were measured during a 1-s interval and were transferred to a computer using Harvard software (Panlab, Barcelona, Spain). The maximal startle reflex response for each animal was calculated as the average of the responses to the 23 auditory stimuli.

Inhibitory Avoidance Stress with Situational Reminders

Rats were placed into the light compartment of an inhibitory avoidance apparatus (50 × 25 × 30 cm3), divided into two equal size compartments, and separated by automatic guillotine door (Korem and Akirav 2014). After 2 min of exploration, the automatic guillotine door was raised allowing access to the dark compartment. Thirty-seconds after the rat entered the dark compartment, the door closed and the rat received an inescapable continuous 1.5 mA shock for 10 s. The rat remained in the dark side for an additional 20 s, after which it was returned to the home cage. The control group received the same treatment, but with the shock mechanism inactivated. Rats were exposed to situational reminders by being placed into the lighted start chamber on days 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 (SR1–SR5) for 1 min with the gate closed to prevent it from entering the shock compartment (to avoid extinction).

Tissue Preparation

The frozen brains were sectioned; selective brain regions punched out and collected for analysis by RT-qPCR of changes in gene expression. Bilateral punches (1 mm diameter) were obtained for BLA, central amygdala (CeA) and LC [−2.3, −2.80 and −9.68 mm from the Bregma, respectively, based on (Paxinos and Watson, 1998)] and preserved in RNAlater-ICE® (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-qPCR for mRNA

Total RNA was isolated using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc, Friendswood, TX) and RNA concentration was evaluated by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The ratio of absorbance at 260–280 nm was about 2.0.

The relative mRNAs levels were determined by RT-qPCR. The RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL) was used for reverse transcription of 600 ng of RNA with an oligo dT primer at 42 °C for 60 min in MyCycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The cDNA (33.2 ng in 2 μl) was mixed with 12.5 μl of FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Rox (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and 1 μl of the appropriate primer sets to a final volume 25 μl in PCR-96-Microplate (Axygen Scientific, Union City, CA) and analyzed on an ABI7900HT Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The following primer sets (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were used: Corticotropin-releasing Hormone (CRH, cat. no. PPR44803B,), Corticotropin-releasing Hormone Receptor 1 (CRHR1, cat. no.PPR44886F), Cannabinoid Receptor 1 (CB1 cat. no. PPR52793A), Dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH, cat. no.PPR52652A), Neuropeptide Y (NPY, cat. no.PPR44428A), Neuropeptide Y Receptor 1 (Y1R, cat. no. PPR56359A), Neuropeptide Y Receptor 2 (Y2R, cat. no. PPR06816A), norepinephrine transporter (NET, cat. no.PPR06785A), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, cat. no.PPR45220F), Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; forward 5′-TGGACCACCCAGCCCAGCAAG-3′, reverse 5′-GGCCCCTCCTGTTGTTATGGGGT-3′; IDT, Newark, NJ). The melting curves were examined to verify a single amplicon at the expected melting temperature and Ct values less than 30 cycles. GAPDH served as an internal control (not altered by experimental conditions), and all values were normalized to GAPDH. The data were analyzed with SDS Software v.24 (Applied Biosystems) using the ΔΔC t method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism 4 (GraphPad) software. Following confirming normality with D’Agostino and Pearson Omnibus Normality Test, data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for repeated measurements with the main factors of treatment and days. For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t test was used. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Repeated measures ANOVA [treatment × days (2 × 2)] on the mean startle amplitude demonstrated significant effects for days [F (1,22) = 60.241, p < 0.001], interaction [F (1,22) = 17.501, p < 0.05], and treatment [F (1,22) = 7.342, p < 0.05]. The Shock group demonstrated increased startle response at the 120 dB level on ASR2 compared to the no-shock (control) group on ASR2 (p < 0.001, Table 1).

Table 1.

Acoustic startle responses in control and exposed to electrical shock group of rats

| Control | Shock | |

|---|---|---|

| ASR1 98 db | 202 ± 23 | 168 ± 13 |

| ASR1 120 db | 331 ± 23 | 298 ± 26 |

| ASR2 98 db | 264 ± 32 | 291 ± 34 |

| ASR2 120 db | 454 ± 47 | 702 ± 65*** |

Startle amplitude (mV) is shown for ASR1 and ASR2

*** p < 0.001 versus control

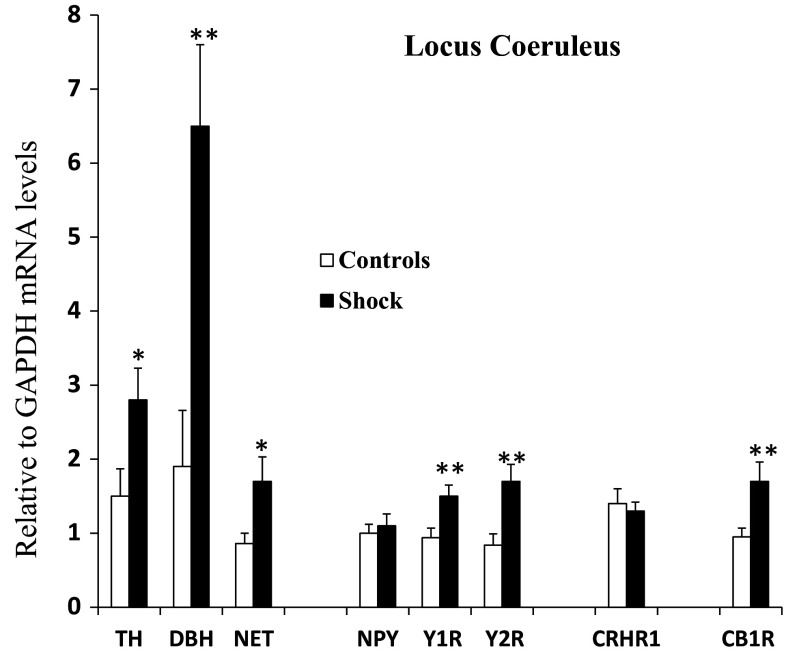

The brain samples from the LC, BLA, and CeA punched from each animal were used to determine levels of mRNA for NE-system (TH, DBH, NET), CRH system (CRH and CRHR1), NPY system (NPY, Y1R, Y2R), and CB1. The changes in the LC mRNA levels are shown in Fig. 2. There were significant elevations of about twofold in TH and NET mRNAs and about threefold in DBH mRNA. No significant changes were observed in the CRH system in the LC. Although mRNA for NPY was not changed, mRNAs for its receptors, Y1R and Y2R, were higher. Moreover, expression of the CB1 gene was also enhanced in the LC.

Fig. 2.

Changes in relative mRNA levels of NE, NPY, CRH, and eCB systems in the locus coeruleus in rats subjected to inhibitory avoidance stress with situational reminders. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 10–12 per group. Open bar is control; closed bar is shocked group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to Controls

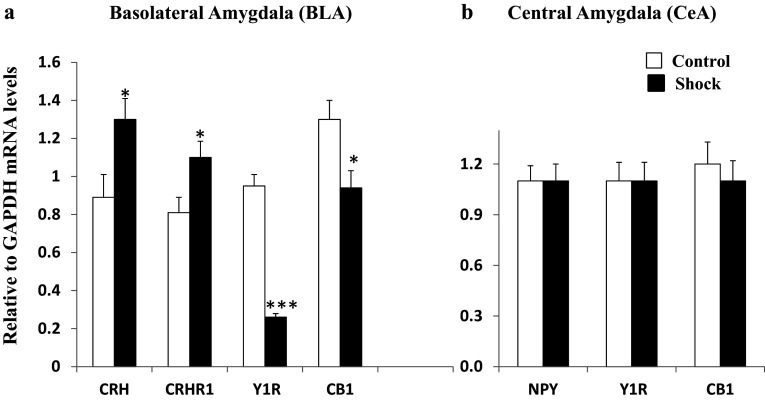

At the same time, the BLA (Fig. 3a) displayed an elevation of the CRH system, with significant increases in mRNAs for both CRH and CRHR1 as well as for CB1. The NPY system revealed an enormous decline in gene expression of the Y1R by more than 70%. The change in mRNA in CeA (Fig. 3b) differed from that of the BLA with no significant change in gene expression in the CRH, NPY, or eCB systems.

Fig. 3.

Changes in relative mRNA levels of NE, NPY, CRH, and eCB systems in the a basolateral and b central amygdala in rats subjected to inhibitory avoidance stress with situational reminders. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 10–12 per group. Open bar is control; closed bar is shocked group. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 compared to Controls

Discussion

The results show that after exposure to inhibition avoidance footshock with situational reminders, there was increased acoustic startle response. At the same time, mRNA levels for NE biosynthetic enzymes (TH and DBH) and NE transporter were significantly elevated together with increased mRNAs for Y1, Y2, and CB1 receptors in the LC. In the BLA rise in CRH and CRHR1, gene expression was accompanied by decreased Y1 and CB1 receptor mRNAs.

Approximately, two-thirds of PTSD subjects have exaggerated reactivity to internal or external trauma-associated cues [rev. in (Southwick et al. 1999)]. The weekly brief situational reminders phenomenologically mimicked the episodes of re-experiencing and perpetuated the adverse effects of the shock (Pynoos et al. 1996). In our experiment, the electrical shock with situational reminder led to hyperarousal in response to acoustic startle.

Regulation of NE biosynthetic enzymes in the LC is an important mechanism for adapting to stress to various stressors [reviewed in (Kvetnansky et al. 2009)]. Stress stimulates release of NE in terminal fields, increases activity and subsequently raises the gene expression of TH, the initial and rate limiting enzyme in NE biosynthetic (Smith et al. 1991; Wang et al. 1998). DBH, the enzyme further catalyzing formation of NE, is also induced (Serova et al. 1999). Repeated exposure to stress elicits further changes in signaling pathways in the LC and a more sustained induction of NE biosynthesis enzymes as well as NE levels in terminal fields (Mamalaki et al. 1992; Kvetnansky et al. 2009). These stress-induced changes in the gene expression of NE producing enzymes are mediated by transcriptional activation (Hebert et al. 2005; Kvetnansky et al. 2009). Here, similar to repeated stress, gene expression of NE biosynthetic enzymes, TH and DBH, and also NET was increased in the shock group in the inhibitory avoidance stress model with situational reminder. Pharmacologically blocking noradrenergic outflow or postsynaptic α1 adrenergic receptors (AR) in mice, in the same model of PTSD, normalized ASR (Olson et al. 2011). The data suggest that increased noradrenergic activation may contribute to hyperarousal associated with PTSD.

In the LC, not only was expression of the TH and DBH genes elevated, but also that of NET. It attenuates neuronal signaling by promoting rapid NE clearance from the synaptic cleft via efficient reuptake recycling 90% of synaptic NE (Blakely 2001; Schwartz et al. 2005), thereby maintaining pre-synaptic NE storage. Recently, it was found that greater NET availability in the LC of trauma survivors with PTSD is associated with increased severity of hypervigilance and exaggerated startle (Pietrzak et al. 2015) which is in line with our findings. Stress-elicited changes in NET expression have previously been observed (Zafar et al. 1997) and may be mediated by glucocorticoids. Chronic administration of corticosterone orally for 21 days led to increased NET mRNA in LC which was accompanied by elevated NET protein levels in the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and the amygdala (Fan et al. 2014).

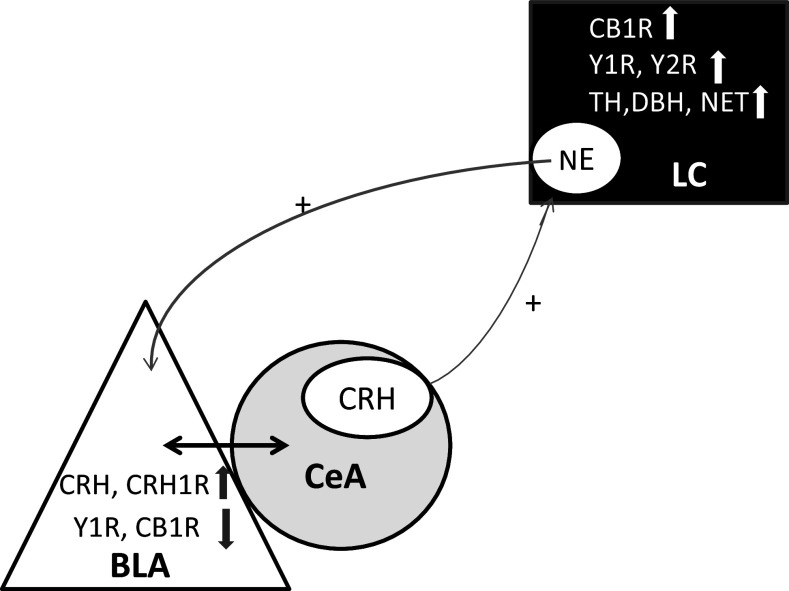

Both α1- and ß-AR are expressed in the amygdala. Excessive NE release into the BLA is proposed to desensitize the α1-AR which acts on GABAergic transmission contributing to hyper-excitability of the amygdala (Braga et al. 2004). This may in turn affect CeA activity since the BLA sends GABAergic projections to the CeA. Reduced GABA inhibitory input to the CeA then would enable enhanced CRH input to the LC in a feed forward mechanism (Kravets et al. 2015) as shown on Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of proposed feed forward mechanism and changes observed in the study. This scheme is based on Kravets and coauthors (Kravets et al. 2015)

Among the most pronounced changes, were alterations of expression of NPY receptors: up-regulation of mRNA for Y1R and Y2R in the LC with large decline for Y1R in the BLA. NPY is the most abundant and widely distributed peptide in the central nervous system with multiple physiological functions including emotional behavior, learning and memory and NPY is implicated in psychiatric disorders such as PTSD. It can act as a stress buffering system (Sah and Geracioti 2013) and intranasal infusion of NPY to rats exposed to single prolong stress prevents and reverses PTSD-related symptoms (Serova et al. 2013, 2014). In the LC, it is co-expressed in NE neurons and releases together with NE. One of NPY’s central and peripheral actions is to inhibit release of the neurotransmitter with which it is co-localized. In numerous preclinical studies, NPY has been shown to inhibit the firing rate of LC neurons and to inhibit release of NE through actions at the pre-synaptic Y2 receptor (Southwick et al. 1999; Kask et al. 2002). We speculate that in our experiments in the shock group the elevation of Y2R mRNAs may be a feedback response to increased biosynthesis of NE in the LC.

The increase of mRNA for postsynaptic Y1R most probably reflects elevated incoming NPY neurotransmission and might be induced by glucocorticoids which are increased not only in response to electrical shock but also in response to stress reminder and ASR2. The Y1R promoter contains one non-palindromic glucocorticoid responsive element (GRE) and several reverse complement non-palindromic GRE sites (Ball et al. 1995; Eva et al. 2006). The promoter of these receptors can be stimulated by dexamethasone and administration of glucocorticoids increase the density of the Y1R in adrenocortical mouse cell line (Bournat and Allen 2001).

However, in the BLA, there was an enormous reduction of expression of the Y1R. In the rat BLA, Y1R immunoreactivity is predominantly on the soma with negligible fiber staining. Y1R localized on pyramidal glutaminergic cells and thus NPY could influence BLA output by directly regulating the activity of these projections. In addition, Y1 receptor also co-localized with markers for intraneurons especially in parvalbumin-ir intraneurons which participate in feedforward inhibition of BLA pyramidal cells (Rostkowski et al. 2009). We also observed up-regulation of genes for CRH and CRHR1 in the BLA. Endogenous release of CRH in the BLA was shown to be elevated in response to conditioned fear and correlated with amount of freezing behavior (Mountney et al. 2011). NPY and CRH have opposing effects in the BLA (Giesbrecht et al. 2010). Reduced Y1R with up-regulation of CRH and CRHR1 in the BLA would push the balance in the BLA in the direction of reduced GABA inhibitory input and enhanced glutaminergic inputs to the CeA (Fig. 4).

CB1 mRNA expression in the BLA was down-regulated. This is consistent with previous studies showing that rats exposed to shock and reminders demonstrated down-regulation in CB1 receptor protein levels in the BLA (Korem and Akirav 2014). CB1 receptors may be down-regulated due to increased release of eCBs in the BLA. In support, it has been shown that glucocorticoids released during stress lead to an increase in eCB in the amygdala (Hill et al. 2005). Predator threat also resulted in down-regulation of CB1 mRNA expression in the amygdaloid complex one week after stress (Campos et al. 2012). Exposure to shock and reminders as well as predator exposure caused long-lasting anxiogenic effects (Campos et al. 2012; Korem and Akirav 2014). Systemically administration of CB1/CB2 receptor agonist WIN55,212-2 (WIN) following shock exposure prevented the shock/reminders-induced impairment in extinction, plasticity, and the enhancement in the startle response (Korem and Akirav 2014). Moreover, intra-BLA administration of the CB1/CB2 receptor agonist WIN following exposure to acute stress or to a single prolonged stress prevented the stress-induced impairment in extinction (Ganon-Elazar and Akirav 2012) and in hippocampal-accumbal plasticity (Segev and Akirav 2016).

There was no effect of the shock and reminders on CB1 in the CeA, although CB1 receptors are present within the CeA (Matsuda et al. 1993) and direct injections of tetrahydrocannabinol into CeA induced anxiety-like responses in mice (Onaivi et al. 1995). The precise role of CB1 receptor activation in the modulation of CeA neuronal activity remains to be determined.

Recent evidence shows that there is an interplay between the eCB and NE systems [rev. in (Carvalho and Van Bockstaele 2012)]. Genetic studies revealed that the CB1 receptor subtype, specifically in DBH-expressing cells, is both necessary and sufficient for stress-induced impairment of memory consolidation (Busquets-Garcia et al. 2016). CB1 receptors, which are predominantly pre-synaptic, are localized to somato-dendritic area as well as within axon terminals and some of the CB1 receptor positive neurons are noradrenergic (Scavone et al. 2010). Systemic administration of cannabinoid agonists increases spontaneous firing rates of neurons in the LC and blocks evoked inhibition (Mendiguren and Pineda 2006; Muntoni et al. 2006). In our experiments, following exposure to shock and reminders, rats exhibited increased CB1 receptor mRNA expression in the LC. In this regard, enhancement of endogenous anandamide signaling by FAAH inhibitor URB597 following forced swim stress decreased the stress-induced neuronal activation of the amygdala and increased neuronal activation in LC (Bedse et al. 2014).

There is also evidence for functional interactions between the NPY and eCB systems in mediating responses to stress. NPY signaling was found to be necessary for the stimulatory effect of CB1 blockers on corticosterone levels (Zhang et al. 2010). Also, when NPY was over-expressed in noradrenergic neurons, there were changes in AEA and especially 2-AG levels in the hypothalamus (Vähätalo et al. 2016).

Further experiments are needed to verify if the changes in these gene expressions observed are indeed reflected in functional changes in their respective protein levels, activity and/or localization by complementary western blots or immunocytochemistry since increased gene expression does not always translate into increased protein/peptide expression. However, overall, the results are consistent with enhancement of feed forward mechanism (Fig. 4) whereby increased noradrenergic input to the BLA, coupled with reduced NPY neurotransmission and enhanced CRH system to the BLA, reduce inhibition of the CeA to further activate the LC noradrenergic system leading to hyperactivity of the LC and exaggerated response to arousing stimuli.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported with funds from the NYMC/Touro Bridge Funding Program (to ES) and the Israel Science Foundation Grant 572/12 (to IA).

Author Contributions

Esther L. Sabban helped to plan experiment, discussed results, and wrote manuscript; Lidia I. Serova performed qPCR for LC, analyzed and discussed data, and participated in writing manuscript; Elizabeth Newman performed qPCR for BLA and CeA, analyzed data; Nurit Aisenberg performed the animal manipulations and isolation of the brain tissue; Irit Akirav planned the experiment, discussed data, and participated in writing the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Alteba S, Korem N, Akirav I (2016) Cannabinoids reverse the effects of early stress on neurocognitive performance in adulthood. Learn Mem 23:349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Kubiak P, Valentino RJ, Shipley MT (1996) Role of the locus coeruleus in emotional activation. Prog Brain Res 107:379–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball HJ, Shine J, Herzog H (1995) Multiple promoters regulate tissue-specific expression of the human NPY-Y1 receptor gene. J Biol Chem 270:27272–27276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedse G, Colangeli R, Lavecchia AM, Romano A, Altieri F, Cifani C, Cassano T, Gaetani S (2014) Role of the basolateral amygdala in mediating the effects of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB597 on HPA axis response to stress. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 24:1511–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Schmeichel BE, España RA (2012) Noradrenergic modulation of wakefulness/arousal. Sleep Med Rev 16:187–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely RD (2001) Physiological genomics of antidepressant targets: keeping the periphery in mind. J Neurosci 21:8319–8323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bournat JC, Allen JM (2001) Regulation of the Y1 neuropeptide Y receptor gene expression in PC12 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 90:149–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga MF, Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Manion ST, Hough CJ, Li H (2004) Stress impairs alpha(1A) adrenoceptor-mediated noradrenergic facilitation of GABAergic transmission in the basolateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquets-Garcia A, Gomis-Gonzalez M, Srivastava RK, Cutando L, Ortega-Alvaro A, Ruehle S, Remmers F, Bindila L, Bellocchio L, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Maldonado R, Ozaita A (2016) Peripheral and central CB1 cannabinoid receptors control stress-induced impairment of memory consolidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:9904–9909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos AC, Ferreira FR, Guimarães FS (2012) Cannabidiol blocks long-lasting behavioral consequences of predator threat stress: possible involvement of 5HT1A receptors. J Psychiatr Res 46:1501–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AF, Van Bockstaele EJ (2012) Cannabinoid modulation of noradrenergic circuits: implications for psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 38:59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eva C, Serra M, Mele P, Panzica G, Oberto A (2006) Physiology and gene regulation of the brain NPY Y1 receptor. Front Neuroendocrinol 27:308–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Chen P, Li Y, Cui K, Noel DM, Cummins ED, Peterson DJ, Brown RW, Zhu MY (2014) Corticosterone administration up-regulated expression of norepinephrine transporter and dopamine beta-hydroxylase in rat locus coeruleus and its terminal regions. J Neurochem 128:445–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavin SA, Winder DG (2013) Noradrenergic control of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in stress and reward. Neuropharmacology 70:324–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganon-Elazar E, Akirav I (2012) Cannabinoids prevent the development of behavioral and endocrine alterations in a rat model of intense stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:456–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geracioti TD Jr, Baker DG, Ekhator NN, West SA, Hill KK, Bruce AB, Schmidt D, Rounds-Kugler B, Yehuda R, Keck PE Jr, Kasckow JW (2001) CSF norepinephrine concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158:1227–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesbrecht CJ, Mackay JP, Silveira HB, Urban JH, Colmers WF (2010) Countervailing modulation of Ih by neuropeptide Y and corticotrophin-releasing factor in basolateral amygdala as a possible mechanism for their effects on stress-related behaviors. J Neurosci 30:16970–16982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz-Cinar O, MacPherson KP, Cinar R, Gamble-George J, Sugden K, Williams B, Godlewski G, Ramikie TS, Gorka AX, Alapafuja SO, Nikas SP, Makriyannis A, Poulton R, Patel S, Hariri AR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Kunos G, Holmes A (2013) Convergent translational evidence of a role for anandamide in amygdala-mediated fear extinction, threat processing and stress-reactivity. Mol Psychiatry 18:813–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman AR, Yang Y, Ressler KJ, Davis M (2008) The role of neuropeptide Y in the expression and extinction of fear-potentiated startle. J Neurosci 28:12682–12690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert MA, Serova LI, Sabban EL (2005) Single and repeated immobilization stress differentially trigger induction and phosphorylation of several transcription factors and mitogen-activated protein kinases in the rat locus coeruleus. J Neurochem 95:484–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MN, Gorzalka BB (2009) The endocannabinoid system and the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders. CNS Neurol Disord 8:451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MN, Ho WS, Meier SE, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ (2005) Chronic corticosterone treatment increases the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol in the rat amygdala. Eur J Pharmacol 528:99–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kask A, Harro J, von Hörsten S, Redrobe JP, Dumont Y, Quirion R (2002) The neurocircuitry and receptor subtypes mediating anxiolytic-like effects of neuropeptide Y. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26:259–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korem N, Akirav I (2014) Cannabinoids prevent the effects of a footshock followed by situational reminders on emotional processing. Neuropsychopharmacology 39:2709–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravets JL, Reyes BA, Unterwald EM, Van Bockstaele EJ (2015) Direct targeting of peptidergic amygdalar neurons by noradrenergic afferents: linking stress-integrative circuitry. Brain Struct Funct 220:541–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Sabban EL, Palkovits M (2009) Catecholaminergic systems in stress: structural and molecular genetic approaches. Physiol Rev 89:535–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukova M, Alaluf LG, Serova LI, Arango V, Sabban EL (2014) Early intervention with intranasal NPY prevents single prolonged stress-triggered impairments in hypothalamus and ventral hippocampus in male rats. Endocrinology 155:3920–3933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz B, Marsicano G, Maldonado R, Hillard CJ (2015) The endocannabinoid system in guarding against fear, anxiety and stress. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:705–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamalaki E, Kvetnansky R, Brady LS, Gold PW, Herkenham M (1992) Repeated immoiblization stress alters tyrosine hydroxylase, coricotropin-releasing hormone and corticosteroid receptor messenger ribonucleic acid levels in rat brain. J Neuroendocrinol 4:689–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Bonner TI, Lolait SJ (1993) Localization of cannabinoid receptor mRNA in rat brain. J Comp Neurol 327:535–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiguren A, Pineda J (2006) Systemic effect of cannabinoids on the spontaneous firing rate of locus coeruleus neurons in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 534:83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Barrera G, Echevarria DJ, Garcia AS, Hernandez A, Ma S, Petre CO (2005) Role of brain norepinephrine in the behavioral response to stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 29:1214–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountney C, Anisman H, Merali Z (2011) In vivo levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone and gastrin-releasing peptide at the basolateral amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex in response to conditioned fear in the rat. Neuropharmacology 60:410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni AL, Pillolla G, Melis M, Perra S, Gessa GL, Pistis M (2006) Cannabinoids modulate spontaneous neuronal activity and evoked inhibition of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci 23:2385–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson VG, Rockett HR, Reh RK, Redila VA, Tran PM, Venkov HA, Defino MC, Hague C, Peskind ER, Szot P, Raskind MA (2011) The role of norepinephrine in differential response to stress in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 70:441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES, Chakrabarti A, Gwebu ET, Chaudhuri G (1995) Neurobehavioral effects of delta 9-THC and cannabinoid (CB1) receptor gene expression in mice. Behav Brain Res 72:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1998) The rat brain in sterotaxic coordinates. Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Gallezot JD, Ding YS, Henry S, Potenza MN, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Carson RE, Neumeister A (2013) Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with reduced in vivo norepinephrine transporter availability in the locus coeruleus. JAMA Psychiatry 70:1199–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Pietrzak RH, Sumner JA, Aiello AE, Uddin M, Neumeister A, Guffanti G, Koenen KC (2015) Association of the rs2242446 polymorphism in the norepinephrine transporter gene SLC6A2 and anxious arousal symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 76:e537–e538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Ritzmann RF, Steinberg AM, Goenjian A, Prisecaru I (1996) A behavioral animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder featuring repeated exposure to situational reminders. Biol Psychiatry 39:129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostkowski AB, Teppen TL, Peterson DA, Urban JH (2009) Cell-specific expression of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor immunoreactivity in the rat basolateral amygdala. J Comp Neurol 517:166–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Laukova M, Alaluf LG, Olsson E, Serova LI (2015) Locus coeruleus response to single-prolonged stress and early intervention with intranasal neuropeptide Y. J Neurochem 135:975–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah R, Geracioti TD (2013) Neuropeptide Y and posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry 18:646–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajdyk TJ, Shekhar A, Gehlert DR (2004) Interactions between NPY and CRF in the amygdala to regulate emotionality. Neuropeptides 38:225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara SJ (2009) The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scavone JL, Mackie K, Van Bockstaele EJ (2010) Characterization of cannabinoid-1 receptors in the locus coeruleus: relationship with mu-opioid receptors. Brain Res 1312:18–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JW, Novarino G, Piston DW, DeFelice LJ (2005) Substrate binding stoichiometry and kinetics of the norepinephrine transporter. J Biol Chem 280:19177–19184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev A, Akirav I (2016) Cannabinoids and glucocorticoids in the basolateral amygdala modulate hippocampal-accumbens plasticity after stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:1066–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serova LI, Nankova BB, Feng Z, Hong JS, Hutt M, Sabban EL (1999) Heightened transcription for enzymes involved in norepinephrine biosynthesis in the rat locus coeruleus by immobilization stress. Biol Psychiatry 45:853–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serova LI, Tillinger A, Alaluf LG, Laukova M, Keegan K, Sabban EL (2013) Single intranasal neuropeptide Y infusion attenuates development of PTSD-like symptoms to traumatic stress in rats. Neuroscience 236:298–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serova LI, Laukova M, Alaluf LG, Pucillo L, Sabban EL (2014) Intranasal neuropeptide Y reverses anxiety and depressive-like behavior impaired by single prolonged stress PTSD model. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 24:142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Brady LS, Glowa J, Gold PW, Herkenham M (1991) Effects of stress and adrenalectomy on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels in the locus ceruleus by in situ hybridization. Brain Res 544:26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Bremner JD, Rasmusson A, Morgan CA 3rd, Arnsten A, Charney DS (1999) Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 46:1192–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Geracioti TD Jr (2008) Noradrenergic dysfunction and the psychopharmacology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety 25:260–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vähätalo LH, Ruohonen ST, Ailanen L, Savontaus E (2016) Neuropeptide Y in noradrenergic neurons induces obesity in transgenic mouse models. Neuropeptides 55:31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele E (2008) Convergent regulation of locus coeruleus activity as an adaptive response to stress. Eur J Pharmacol 583:194–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Kitayama I, Nomura J (1998) Tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the locus coeruleus of depression-model rats and rats exposed to short-and long-term forced walking stress. Life Sci 62:2083–2092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar HM, Paré WP, Tejani-Butt SM (1997) Effect of acute or repeated stress on behavior and brain norepinephrine system in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats. Brain Res Bull 44:289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lee NJ, Nguyen AD, Enriquez RF, Riepler SJ, Stehrer B, Yulyaningsih E, Lin S, Shi YC, Baldock PA, Herzog H, Sainsbury A (2010) Additive actions of the cannabinoid and neuropeptide Y systems on adiposity and lipid oxidation. Diabetes Obes Metab 12:591–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]