Abstract

Ischemia–reperfusion (I/R)-induced spinal cord injury can cause apoptotic damage and subsequently act as a blood–spinal cord barrier damage. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) contributed to the process of I/R injury by regulating their target mRNAs. miR-199a-5p is involved in brain and heart I/R injury; however, its function in the spinal cord is not yet completely clarified. In this study, we investigated the role of miR-199a-5p on spinal cord I/R via the endothelin-converting enzyme 1, especially the apoptosis pathway. In the current study, the rat spinal cord I/R injury model was established, and the Basso Beattie Bresnahan scoring, Evans blue staining, HE staining, and TUNEL assay were used to assess the I/R-induced spinal cord injury. The differentially expressed miRNAs were screened using microarray. miR-199a-5p was selected by unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis. The dual-luciferase reporter assay was used for detecting the regulatory effects of miR-199a-5p on ECE1. In addition, neuron expression was detected by immunostaining assay, while the expressions of p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, caspase-9, Bcl-2, and ECE1 were evaluated by Western blot. The results indicated the successful establishment of the I/R-induced spinal cord injury model; the I/R induced the damage to the lower limb motor. Furthermore, 18 differentially expressed miRNAs were detected in the I/R group compared to the sham group, and miR-199a-5p protected the rat spinal cord injury after I/R. Moreover, miR-199a-5p negatively regulated ECE1, and silencing the ECE1 gene also protected the rat spinal cord injury after I/R. miR-199a-5p or silencing of ECE1 also regulated the expressions of caspase-9, Bcl-2, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 in rat spinal cord injury after I/R. Therefore, we demonstrated that miR-199a-5p might protect the spinal cord against I/R-induced injury by negatively regulating the ECE1, which could aid in developing new therapeutic strategies for I/R-induced spinal cord injury.

Keywords: Blood–spinal cord barrier, Ischemia/reperfusion, Apoptosis, MiR-199a-5p, ECE1

Introduction

Spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, if one of the major pathogenic mechanisms underlying spinal cord injury that restores blood perfusion in the ischemic spinal cord tissues post-injury (Mathew and Laden 2015; Kardes et al. 2016; Borgens and Liu-Snyder 2012; Anwar et al. 2016). Temporary aortic occlusion in surgical repair of thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurisms induces different extents of spinal cord ischemia and further nerve functional impairments in order to avoid the complications including sexual dysfunction and paraplegia (Kilany et al. 2015; Bell et al. 2015; Azzarone et al. 2016). Although numerous clinical and laboratory studies have made an attempt to reduce the risk of spinal cord I/R injury, and various refinements in surgical techniques and developments in adjunctive measures such as ischemic and chemicals preconditioning have been developed to protect the spinal cord against I/R-induced injury, it continues to affect the surgical outcomes and results in a great psychoeconomic burden to the patients (Anwar et al. 2016; Anttila et al. 2016; Yamamoto et al. 2016). The spinal cord ischemia is present in approximately 3–18% of the patients, depending on the type of aneurysm and other combined diseases (Tabayashi et al. 2004; Ikpeze and Mesfin 2017). Therefore, effective treatments and specific drugs for protection against spinal cord ischemic injury require further investigation. However, presently, the pathogenic molecular mechanism of spinal cord I/R injury is yet unclear, which is an impending hindrance to the development of effective treatments and specific drugs.

MicroRNA (miRNAs) are noncoding endogenous 18–24 nt short RNA molecules with specific mRNA translation inhibitory function (Bhalala et al. 2013). A miRNA is capable of specific binding to one or more target mRNAs and effectively regulate the gene expression at posttranscriptional level in various tissues (Zeng et al. 2015; Hinkel et al. 2013). It was demonstrated that ischemia altered the miRNA expression in cardiac tissues. The antagomirs against miRNA improved the neovascularization and augmented the functional recovery in cardiac I/R injury animals, emphasizing the critical role of miRNAs in I/R regulation (Guo et al. 2013). Recent studies have shown that several miRNAs exist in mammalian central nervous system including brain and spinal cord that are involved in the regulation of central nervous system injury and repair following the injury, and neurotraumatic pathologies (Zeng et al. 2015; Bhalala et al. 2013). Increasing evidence has shown that miRNAs are involved in traumatic spinal cord injury (Jee et al. 2012) and I/R injury (Liu et al. 2015). Emerging studies showed that miR-199a-5p can be expressed in several tissues such as the brain, liver, blood vessels, visceral smooth muscle, ovarian and testicular tissues, myocardial and endothelial cells, and spinal cord (Chan et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2015; Hashemi Gheinani et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2015; Henaoui et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2017). Another study showed that miR-199a-5p was downgraded in stroke-associated ischemia (Park et al. 2011) and participated in the heart and the mechanism underlying the cerebral I/R injury (Hu et al. 2015). However, the regulatory function of miR-199a-5p in spinal cord I/R injury is not yet clarified. Therefore, exploring the miR-199a-5p regulatory pattern in the I/R injury of spinal cord has great significance for the development of efficient treatments and novel specific drugs.

In the current study, we successfully established the model of I/R-induced spinal cord injury and explored the effects of I/R on the damage of lower limb motor. In addition, we analyzed the miRNA expression patterns in spinal cord I/R injury using miRNA arrays. Among the identified miRNAs, miR-199a-5p was the maximally dysregulated miRNA. Furthermore, miR-199a was specifically expressed in nerve tissues and participated in nerve regeneration, neurite outgrowth, and synaptic plasticity (Liu et al. 2012; Lv 2017). Next, we demonstrated the protective effect of miR-199a-5p on rat spinal cord injury after I/R. Next, the target genes of miR-199a-5p were screened, and miR-199a-5p was found to negatively regulate the endothelin-converting enzyme-1 (ECE1), a key enzyme associated with cardiac defects and autonomic dysfunction (Zeng et al. 2016; Khamaisi et al. 2015; Sui and He 2014). In addition, we explored the protective effect of ECE1 knockdown on rat spinal cord injury after I/R and demonstrated the effects of miR-199a-5p and ECE1 on the expressions of caspase-9, Bcl-2, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 in rat spinal cord injury after I/R. The findings might provide new therapeutic targets with respect to the apoptotic damage in spinal cord I/R injury.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Model of Spinal Cord I/R Injury

The male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were obtained from the Animal Center of China Medical University. All SD rats with weights of 220–280 g were allowed free food and water in standard cages. All SD rats were maintained in individual cages under controlled temperature (22–24 °C) and 12-h light/dark cycle for at least a week before surgery. All SD rats were separately housed after surgery. This study and the experimental procedures were proved by the Laboratory Animal Center of China Medical University.

The I/R-induced spinal cord injury model was performed by occluding the aortic arch for 14 min as described previously (Liu et al. 2015). After anesthetization with 4% sodium pentobarbital (Beyotime, China) at 50 mg/kg via an intraperitoneal injection, the rat aortic arch was exposed via a cervicothoracic approach. Under direct visualization, the rat aortic arch between the left common carotid artery and left subclavian artery was cross-clamped. The occlusion was confirmed using laser doppler blood flow monitor. After occlusion for 14 min, the clamps were removed. After reperfusion for 24 h, the BBB score and the integrity of the blood–spinal cord barrier (BSCB) were evaluated. The rats in the sham group were without occlusion, but with reperfusion, for 24 h. Then, the rats were sacrificed for histopathological examination, including evaluation of the wet/dry weight ratio, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histology, and TUNEL.

miRNA Microarray Analysis

After reperfusion for 24 h, the L4 − 6 segments of the spinal cord were harvested as reported previously (Liu et al. 2015). The TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) and the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, UK) were used for extracting the total RNA from samples that was estimated on Nanodrop 1000 (Thermo, USA). The RNAs were labeled and hybridized using the miRCURY Hy3/Hy5 Power labeling kit (Exiqon, Denmark) and miRCURY LNA Array (Exiqon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After washing, the slides were scanned using an Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Axon, USA), and images were processed using GenePix Pro 6.0 program (Axon). Replicated miRNAs were averaged, and the normalized factor was calculated using the miRNAs with ≥ 50 intensities. The expression data were normalized using median normalization method. The differentially expressed miRNAs were identified by Volcano Plot filtering. Finally, the differences in the miRNA expression profiles among the samples were determined by hierarchical clustering using MEV software (version 4.6; TIGR, USA).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

miRNA and mRNA expressions were evaluated on Applied Biosystems 7500 system (Applied Biosystems, USA). Total RNAs from the L4 − 6 segments were extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the PrimeScript miRNA cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa, China). PCR was performed using SYBR Green SuperMix-DUG; the primers were as follows: ECE1, 5′-TTGGTGGTATCGGGGTCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACTCGGTCTGCTGCTTGAAT-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-CCTCGTCTCATAGACAAGATGGT-3′ (forward) and 5′- GGGTAGAGTCATACTGGAACATG-3′ (reverse). All reactions were performed in triplicate and the result was analyzed using the 2−∆∆Ct method; the expression of the target genes was normalized to that of GAPDH. Furthermore, PCR was used to amplify the miR-199a-5p using SYBR Premix Ex TaqII™ (TaKaRa) and primers (forward, 5′-ACACTCCAGCTGGGCCCAGTGTTCAGACTACC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAG GAACAGGTA-3′; RiboBio, China) at 95 °C for 10 s; followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 20 s. The primers used for amplification of U6 were as follows: 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′ (reverse). The tests were performed in triplicate and data analyzed using the 2−∆∆Ct method and normalized to that of U6.

Sample Treatment and Transfection

The intrathecal pretreatment was performed as described previously (He et al. 2011). A polyethylene catheter (PE10, Portex, UK) was exposed in the upper thoracic region from T5 − 6, with 7–8 cm of the remaining of the free end. Before surgery, we intrathecally infused 10 µL of 1 × 109 TU/mL of synthetic miR-199a-5p mimic lentiviral (mimic), miR-199a-5p inhibitor lentiviral (inhibitor), negative control lentiviral (NC, GenePharma, China), or shRNA-ECE1 lentiviral (GenePharma) for 5 days. Subsequently, the specificity and efficacy were assessed by qRT-PCR.

BBB scoring and Evans Blue (EB) Extravasation Assay

The BBB scoring for the movement function of the rat lower limb was detected as described previously (Basso et al. 1995; Wang et al. 2016). In addition, the integrity of the brain vessels in the spinal cord tissue was quantitatively assessed using Evans Blue (EB) extravasation (Liu et al. 2015; Keshavarz and Dehghani 2017; Swanson et al. 1990). After preparation, EB was detected by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan).

Immunostaining Assay

To explore the change in neurons, immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously (He et al. 2011). In brief, sections (10 µm) were incubated with rabbit anti-Neuron-specific beta III Tubulin (1:200; Abcam, cat. ab229590, USA) primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with an Alexa 593-conjugated immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (1:500; Molecular Probes, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the staining was visualized using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Leica, USA) and images from five random fields were analyzed by Image J (; NIH, USA). Green fluorescent protein was used to indicate the lentiviral transfected cells.

Histopathological Analysis

Rat spinal cords were surgically removed in each group (24 h after reperfusion in the sham and I/R model groups) and tissue samples were subjected to histological analysis. The tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin wax, and sliced into 4-µm-thick sections. Subsequently, H&E staining was performed for the histological assessment of the spinal cord injury.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase Deoxyuridine Triphosphate (dUTP) Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay

10-mm-thick sections were subjected to fluorometric TUNEL assay using the commercial kit (Beyotime) to detect the apoptotic DNA strand breaks. The sections were fixed with 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde for 20 min and incubated with proteinase K for 20 min, followed by the labeling reaction for 2 h. Then, the nuclei were stained with DAPI and images captured by fluorescence microscopy.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

The wild-type and mutated 3′-UTR vectors of ECE1 were synthesized and psi-CHECK2 plasmid constructed by Fast Mutagenesis System (TransGen Biotech, China). All the vectors were ligated to pluc-Reporter luciferase vector. After DNA sequencing, 10 nmol pre-miR-199a-5p or NC and 100 ng vectors were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells in 24-well plates. After 24 h, luciferase activities were determined by Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, USA) using Glomax Luminometer (Promega, USA). The data of renilla luciferase activity were normalized to firefly luciferase activity.

Western Blot Assay

The expressions of ECE1, caspase-9, Bcl-2, JNK, p-JNK, ERK, and p-ERK in spinal cord tissues were performed by Western blot. After homogenization, total proteins were extracted from tissues using tissue protein extraction kit (KangChen, China) and resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by transfer to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 4% BSA blocking solution at 4 °C and incubated with primary antibodies against ECE1, caspase-9, Bcl-2, JNK, p-JNK, ERK, p-ERK, and GAPDH (1:200, Santa Cruz, USA) overnight. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000, Bioss, China) for 1 h at room temperature and finally detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Life Science, UK).

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 with Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Newman–Keuls post-hoc analysis. P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

I/R Induced the Damage of Lower Limb Motor

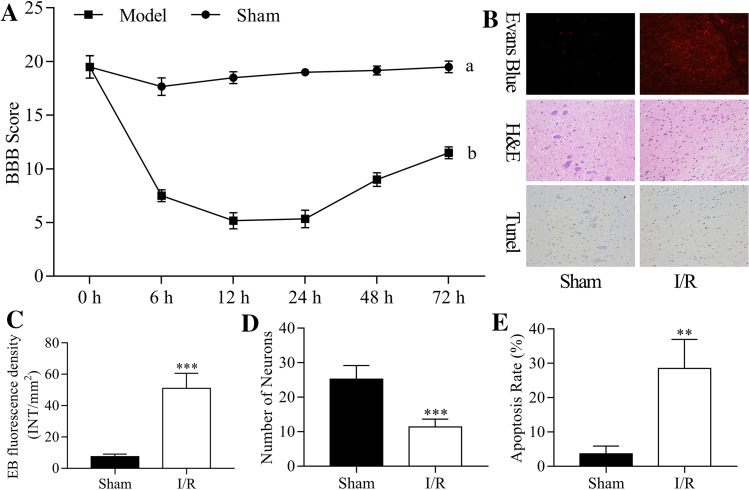

The I/R-induced rat spinal cord model was established. The BBB scoring criteria evaluated the dysfunction of lower limb motor at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after I/R injury, and the results indicated that the lower limb motor function scores were significantly decreased in I/R groups compared to the sham group (Fig. 1a). These findings suggested that I/R induced the damage of lower limb motor.

Fig. 1.

I/R-induced damage of lower limb motor. The rat spinal cord I/R injury model was established. a The lower limb motor function was assessed using BBB scoring criteria at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-injury. b EB fluorescence, number of neurons, and cell apoptosis were detected by EB, H&E, and TUNEL assays at 24 h post-injury, respectively. c EB fluorescence density was quantitatively analyzed by EB assay. d The number of neurons was counted according to H&E staining. e The rate of apoptosis was calculated according to the TUNEL assay

In addition, EB, H&E, and TUNEL assays were performed to measure EB fluorescence, the number of neurons, and cell apoptosis at 24 post-injury, respectively (Fig. 1b). Thus, we found that the EB fluorescence density was significantly increased in the I/R group (P < 0.001, Fig. 1C), the number of neurons was significantly decreased (P < 0.001, Fig. 1d), and the cell apoptosis rate was significantly increased in the I/R group compared to the sham group (P < 0.01, Fig. 1e). Therefore, we suggested that the I/R-induced spinal cord injury model was established successfully.

MiRNAs Expression in the Rat Spinal Cord After I/R

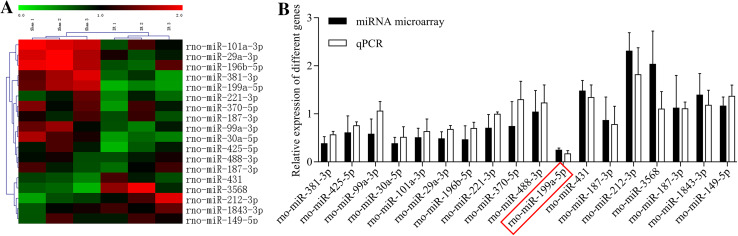

Furthermore, to explore the mechanism underlying I/R-induced spinal cord injury, we screened the differentially expressed miRNAs in I/R and sham groups using the microarray assay. As shown in Fig. 2a, clustered heatmaps of the 18 differentially expressed miRNAs were displayed according to fold-change (I/R group vs. sham group). In addition, we detected the 18 differentially expressed miRNAs in the I/R and sham group using the qRT-PCR assay.

Fig. 2.

MiRNAs expression in the rat spinal cord after I/R. The rat spinal cord I/R injury model was established. a Heat map of the differentially expressed miRNAs in the sham (n = 6) and I/R groups (n = 6). Each column indicates the expression profile of a sample; and red is high expression, green is low expression. b miR-199a-5p expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR assay in the sham and model groups

Both qRT-PCR and microarray assays indicated that miR-199a-5p was dramatically downregulated in the I/R group compared to the sham group (Fig. 2b).

miR-199a-5p Protected the Rat Spinal Cord Injury After I/R

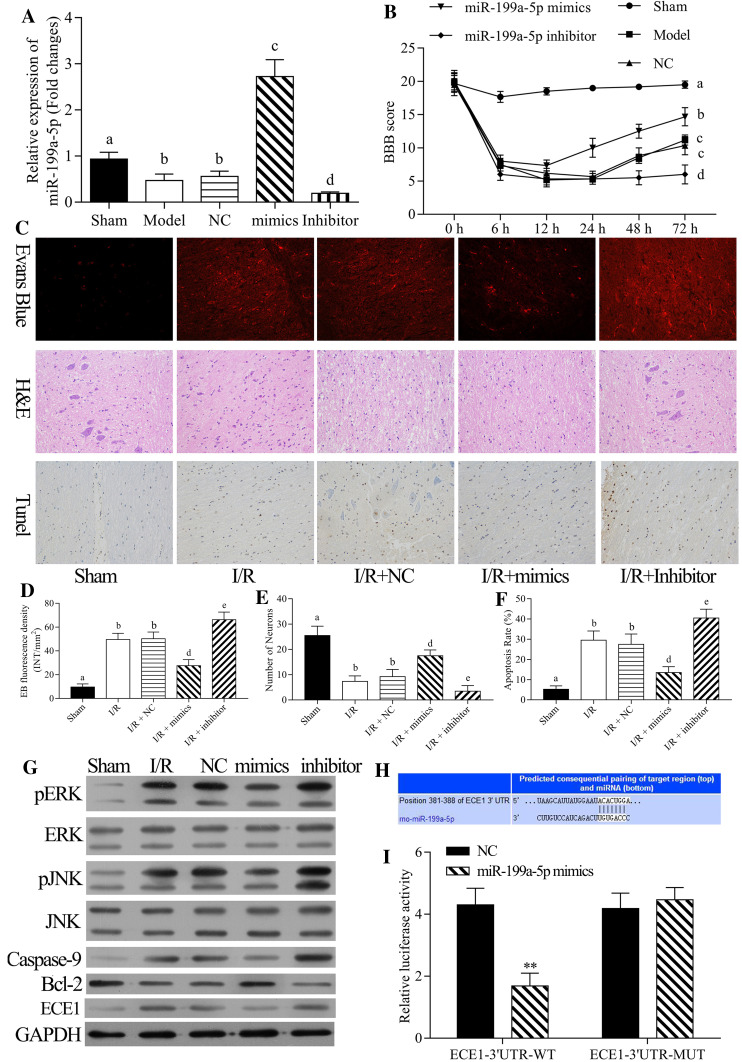

To explore the roles of miR-199a-5p in I/R-induced spinal cord injury, we intrathecally injected miR-199a-5p mimic, inhibitors, or NC in rats for 5 days. Then, the expression level of miR-199a-5p was detected using qRT-PCR assay. The results indicated that miR-199a-5p was significantly decreased in the model group compared to the sham group; miR-199a-5p was significantly increased in the miR-199a-5p mimic group compared to the negative control (NC) group; miR-199a-5p was significantly decreased in the miR-199a-5p inhibitor group compared to the NC group (P < 0.05, Fig. 3a). Next, we evaluated the lower limb motor function after I/R injury for 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. The results showed that the BBB score was significantly decreased in the model group compared to the sham group; the score was significantly increased in the miR-199a-5p mimic group compared to the NC group, while it was significantly decreased in the miR-199a-5p inhibitor group compared to the NC group (P < 0.05, Fig. 3b). Therefore, we suggested that miR-199a-5p protected the rat limb motor function against spinal cord I/R injury.

Fig. 3.

Effects of miR-199a-5p on the rat spinal cord injury after I/R. The rat spinal cord I/R injury model was established and transfected with negative control (NC), miR-199a-5p mimic, and miR-199a-5p inhibitor, respectively. a The mRNA expression level of miR-199a-5p was detected by qRT-PCR assay. b The lower limb motor function of rats was analyzed by BBB scoring criteria at spinal cord I/R injury at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-reperfusion. c EB fluorescence, number of neurons, and cell apoptosis were measured by EB, H&E, and TUNEL assays at 24 h post-injury, respectively. d EB fluorescence density, e number of neurons, and f cell apoptosis were analyzed quantitatively. g The protein expression levels of p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, caspase-9, Bcl-2, and ECE1 were measured by Western blot assay. h The putative complementary site of miR-199a-5p and ECE1 was obtained based on TargetScan prediction. Cells were transfected with wild-type ECE1 and mutant-type ECE1, and NC or miR-199a-5p mimic, respectively. The luciferase intensity was measured by dual-luciferase reporter assay. **P < 0.01 vs. NC group. a–c P < 0.05 vs. sham, I/R and NC, respectively

Moreover, EB, H&E, and TUNEL assays were performed to measure the EB fluorescence, number of neurons, and cell apoptosis at 24 post-injury, respectively (Fig. 3c). The results proved that the density of EB fluorescence was significantly increased in the I/R group compared to the sham group, and miR-199a-5p significantly reduced the EB fluorescence density, while the miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly raised the density (P < 0.05, Fig. 3d). The number of neuron was significantly decreased in the I/R group compared to the sham group, and miR-199a-5p significantly increased the number of neurons, while the miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly decreased the number of neurons (P < 0.05, Fig. 3e). The apoptosis rate was significantly increased in the I/R group compared to the sham group, and miR-199a-5p significantly inhibited the apoptosis, while miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly promoted the rate of apoptosis (P < 0.05, Fig. 3f). Thus, miR-199a-5p might protect the spinal cord against I/R injury.

miR-199a-5p Regulated Caspase-9, Bcl-2, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 Expressions in Rat Spinal Cord Injury After I/R

Furthermore, to investigate the possible mechanism of miR-199a-5p in apoptotic damage after I/R, we detected the expression levels of caspase-9, Bcl-2, JNK, p-JNK, ERK, p-ERK, and ECE1 by Western blot after miR-199a-5p mimic or inhibitor transfection. As shown in Fig. 3g, caspase-9, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 expressions were significantly upregulated in I/R group compared to the sham group, and miR-199a-5p significantly suppressed the expressions of caspase-9, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1, while miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly accelerated the expressions of caspase-9, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1. Bcl-2 expression was significantly downregulated in the I/R group compared to the sham group, and miR-199a-5p significantly promoted the Bcl-2 expression, while miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly inhibited the Bcl-2 expression. Therefore, miR-199a-5p inhibited the apoptosis of rat spinal cord injury after I/R.

miR-199a-5p Negatively Regulated ECE1

Based on the databases of TargetScan and MicroCosm Targets, we found a binding site between miR-199a-5p and ECE1 3′-UTR, and hence, adopted the luciferase reporter assay to prove the regulation of miR-199a-5p on ECE1 3′-UTR. As shown in Fig. 3h, i, the luciferase intensity of wild-type ECE1 was significantly inhibited by miR-199a-5p, while miR-199a-5p had no effect on mutated ECE1 (P < 0.01). Therefore, we hypothesized that downregulation of miR-199a-5p promotes I/R-induced apoptotic damage via upregulation of ECE1.

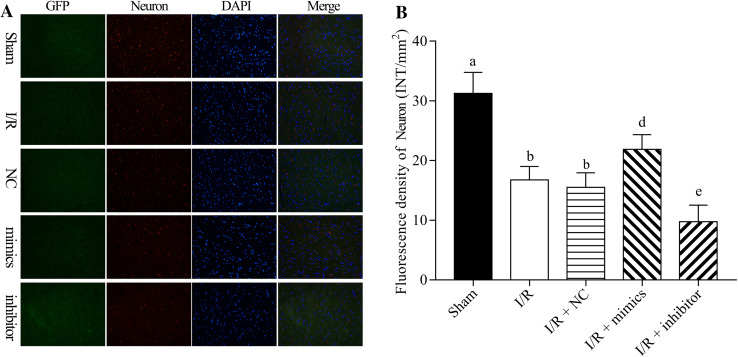

miR-199a-5p Induced Neuron Proliferation in I/R-Induced Spinal Cord Injury Rats

The protective role of miR-199a-5p in I/R injury was further detected by immunostaining (Fig. 4a). The findings indicated that I/R downregulated the proliferation of neuron and damaged the neuron cells. miR-199a-5p significantly upregulated neuron-specific beta III tubulin expression mediated by I/R, and miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly downregulated the neuron-specific beta III tubulin expression mediated by I/R (P < 0.05, Fig. 4b). Thus, we suggested that miR-199a-5p protected the spinal cord against I/R injury.

Fig. 4.

miR-199a-5p inducing neuron proliferation in I/R-induced spinal cord injury rats. The rat spinal cord I/R injury model was established and transfected with negative control (NC), miR-199a-5p mimic, and miR-199a-5p inhibitor, respectively. a The immunostaining assay was performed to assess the expression of neuron-specific beta III tubulin. b Neuron-specific beta III tubulin expression was quantified. DAPI indicates the nucleus. a–c P < 0.05 vs. sham, I/R and NC, respectively

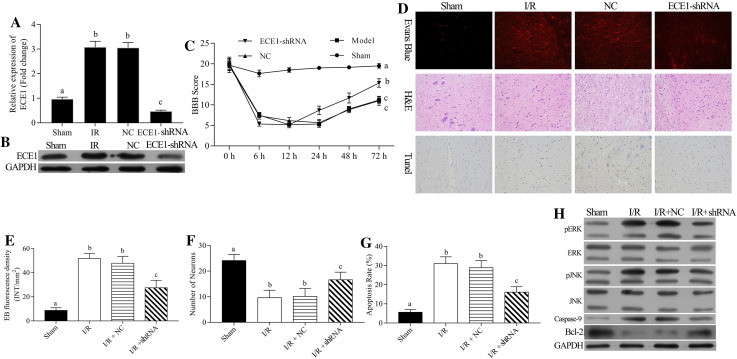

Silencing of ECE1 Protected The Rat Spinal Cord Injury After I/R

To further detect the role of ECE1 in I/R-induced spinal cord injury, we intrathecally injected the shRNA-ECE1 or NC in rats for 5 days. Then, the mRNA and protein expression level of ECE1 was detected by qRT-PCR and Western blot assays, respectively. The results demonstrated that ECE1 expression was markedly upregulated in I/R group compared to the sham group and markedly downregulated in the shRNA-ECE1 group compared to the NC group (P < 0.05, Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5.

Silencing of ECE1 exerting a protective effect on the rat spinal cord injury after I/R. The rat spinal cord I/R injury model was established and transfected with negative control (NC) and shRNA-ECE1s, respectively. (a) The mRNA expression level of ECE1 was accessed by qRT-PCR assay. b The protein expression level of ECE1 was analyzed by Western blot assay. c The lower limb motor function of rats was evaluated by BBB scoring criteria of spinal cord I/R injury at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-reperfusions. d EB fluorescence, number of neurons, and cell apoptosis were measured by EB, H&E, and TUNEL assays at 24 h post-injury, respectively. e EB fluorescence density, f number of neurons, and g cell apoptosis were analyzed quantitatively, respectively. h Expressions of p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, caspase-9, Bcl-2, and ECE1 were measured by Western blot assay. a–c P < 0.05 vs. sham, I/R and NC, respectively

Then, the effect of shRNA-ECE1 on I/R injury of rat spinal cord was determined. After spinal cord I/R injury at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-reperfusions, the lower limb motor function of rats was significantly increased in the shRNA-ECE1 group related to the NC group, indicating that ECE1 protected the limb motor function of rats against spinal cord I/R injury (P < 0.05, Fig. 5c). Silencing ECE1 reduced the I/R-mediated increase in EB extravasation, indicating that silencing of ECE1 inhibited the I/R-induced BSCB disruption (P < 0.05, Fig. 5d, e). IN addition, silencing ECE1 significantly increased the number of neurons mediated by I/R (P < 0.05, Fig. 5d, f), as well as, significantly inhibited the apoptosis mediated by I/R (P < 0.05, Fig. 4d, g). Therefore, we verified that downregulation of ECE1 protected the spinal cord against I/R injury.

Role of ECE1 in I/R-Induced Apoptotic Damage of Spinal Cord

To further explore the mechanism of ECE1 in apoptotic damage after I/R, we detected the expressions of caspase-9, Bcl-2, JNK, p-JNK, ERK, and p-ERK after shRNA-ECE1 transfection. The results indicated that the expressions of caspase-9, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 were significantly upregulated, while that of Bcl-2 was significantly downregulated. The silencing of ECE1 reversed these I/R-mediated changes. miR-199a-5p significantly promoted the Bcl-2 expression, while miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly inhibited the Bcl-2 expression. Therefore, miR-199a-5p inhibited the apoptosis of rat spinal cord injury after I/R (Fig. 4h).

Discussion

Spinal cord I/R injury is to restore blood perfusion in the ischemic spinal cord tissues after spinal cord tissue injury (Sun et al. 2017). After a specific period of ischemia, spinal cord did not appear in the improvement of neural function after reperfusion, but delay in the spinal nerve dysfunction that also led to paralysis (Fang et al. 2015; Boyaci et al. 2014). When perfusion damage occurs, the spinal cord neuronal apoptosis is the primary cause of death. The rat spinal cord ischemia area is characterized by necrosis of neurons after brief ischemia (Arsava et al. 2009), which might be attributed to apoptosis in spinal ischemia reperfusion injury (Cheng et al. 2018). Therefore, inhibition of neuronal apoptosis or reduction in delayed neuronal death is under intensive focus for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Moreover, the pathological molecular mechanisms underlying spinal cord I/R injury have not yet been elucidated, necessitating it as an urgent prerequisite in spinal cord I/R injury.

The self-adjusting ability of spinal cord blood supply is far less than the brain tissues. Ischemic injury is likely to occur in spinal cord tissue than brain tissue, and when the blood flow is restored, the rapid increase in the blood flow may further aggravate the injury.

Reportedly, the model of I/R-induced spinal cord injury was successfully established, and the effect of spinal cord I/R injury was most obvious at 24–48 h (Ubbink and Jacobs 2000). In addition, we adopted this method to establish the model of I/R-induced spinal cord injury. The current study also confirmed that the thoracic aorta between the left carotid artery and the lower subclavian artery was clipped with the appropriate artery clamp, which can successfully realize the motor dysfunction of hind limbs of rats and the injury of the lumbar segment (L4–6) spinal cord (Liu et al. 2015). Therefore, we chose the same L4–6 segments of the spinal cord.

In the current study, we established the I/R-induced spinal cord injury model by occluding the aortic arch for 14 min, followed by reperfusion for 24 h. The damage of BSCB could lead to secondary spinal cord injury, which is the underlying pathophysiological mechanism (Sharma 2005). The characteristics of spinal cord injury are necrosis, inflammation, ischemia, and changes in the permeability of the BSCB. Therefore, we observed the dysfunction of lower limb motor, BSCB disruption, number of neurons, and apoptotic cells after spinal cord I/R injury and demonstrated a successful establishment of the I/R-induced spinal cord injury model.

MiRNAs play major roles in reperfusion injury of central nervous system (Liang et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018). In the current study, the differentially expressed miRNAs were screened in the I/R and sham groups using microarray assay. Also, we found 18 differently expressed miRNAs (miR-381-3p, miR-425-5p, miR-99a-3p, miR-30a-5p, miR-101a-3p, miR-29a-3p, miR-196b-5p, miR-221-3p, miR-370-5p, miR-488-3p, miR-199a-5p, miR-431, miR-187-3p, miR-212-3p, miR-3568, miR-187-3p, miR-1843-3p, and miR-149-5p) after reperfusion. Next, we identified the screened miRNAs using qRT-PCR assay and found that miR-199a-5p showed a marked low expression in the I/R group compared to the sham group. Previous studies have also shown that miR-199a was specifically expressed in nerve tissues and participated in nerve regeneration, neurite outgrowth, and synaptic plasticity (Liu et al. 2012; Lv 2017). In addition, we found that miR-3568 was highly expressed in the I/R group compared to the sham group (fold-change > 2). However, there were inconsistencies in the miR-3568 expression by qRT-PCR and microarray. Currently, miR-3568 has been studied in vascular smooth muscle cells from rats with kidney disease (Chaturvedi et al. 2015), and none of the studies have demonstrated that miR-3568 expression was related to I/R. Therefore, miR-199a-5p was selected as the research objective.

Researches have demonstrated that miR-199a was involved in I/R injury (El et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2012). It actively repressed cardiac peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ expression, facilitating a metabolic shift from predominant reliance in myocardium (El et al. 2013). The upregulation of miR-199a inhibited Sirt1 expression in hippocampal neurons, indicating that miR-199a was involved in the brain ischemic tolerance (Xu et al. 2012). In this study, we first investigated that miR-199a-5p plays a neuroprotective role in spinal cord I/R injury, and found that miR-199a-5p protected the rat spinal cord injury after I/R.

Previous studies showed that PI3K/Akt signaling was involved in the apoptosis in brain after hypoxia ischemia, and exerts a protective role of neurons against apoptotic damage via phosphorylation of downstream substrates c-Jun N terminal kinase (JNK) (Zhao et al. 2006). The activation of JNK pathway induces the production of Bad, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xl, activating the caspase and apoptosis (Wang et al. 2007). In the current study, we demonstrated that miR-199a-5p significantly downregulated the expressions of caspase-9, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 and upregulated the expression of Bcl-2; miR-199a-5p inhibitor significantly increased the expressions of caspase-9, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 and decreased the Bcl-2 expression. Therefore, we suggested that miR-199a-5p inhibited the apoptosis of rat spinal cord injury after I/R.

ECE, a zinc-containing membrane-bound metal proteinase II, is mainly in the cardiovascular system and belongs to neutral endopeptidase (NEP) family with three isomers. ECE1 is the key rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of porcine endothelin (ET-1). Currently, studies have shown that the ECE inhibitor of intravenous injection can exert a protective effect on the cerebral cortex nerves in rats (Chang et al. 2004). The pretreatment of spinal cord I/R injury by ECE1 inhibitor via rat tail vein injection can alleviate the condition (Chou et al. 2007). Reportedly, ECE1 is widely distributed in tissues with expression higher than that of ECE 2 and ECE3(Lorenzo et al. 2001). Another study showed that hypoxia can increase the expression level of ECE1 and promote the biosynthesis rate of ET-1 in vivo (Takahashi et al. 2001). It has also been proved that histanoxia, oxidative metabolism enhancement, and increased catecholamine can stimulate the production of ECE1 (Wang et al. 2008). In the current study, we verified that miR-199a-5p negatively regulates ECE1, and silencing ECE1 exerted a protective role on the rat spinal cord injury after I/R. Also, we indicated that silencing of ECE1 regulated the expressions of caspase-9, Bcl-2, p-JNK, p-ERK, and ECE1 in rat spinal cord injury after I/R.

Conclusions

In summary, the knockdown of miR-199a-5p might regulate I/R-induced apoptotic damage via upregulation of ECE1. The current findings provided a theoretical support for relieving the secondary injury of spinal cord after thoracic and lumbar spine surgery, thereby facilitating the rehabilitation of motor and sensory functions, as well as, novel drug development.

Author Contributions

HM and NB conceived and designed the study. NB, BF, HWL, and YHJ performed the experiments. BF, FSC, and ZLW analyzed the data. NB and HM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Ning Bao, Bo Fang, Huangwei Lv, Yanhua Jiang, Fengshou Chen, Zhilin Wang, and Hong Ma declare that they have no financial and personal relationships with people or organizations that can inappropriately influence the current study; there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of the manuscript entitled “Upregulation of miR-199a-5p protects spinal cord against ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury via downregulation of ECE1 in rat.”

References

- Anttila V, Haapanen H, Yannopoulos F, Herajarvi J, Anttila T, Juvonen T (2016) Review of remote ischemic preconditioning: from laboratory studies to clinical trials. Scand Cardiovasc J 50(5–6):355–361. 10.1080/14017431.2016.1233351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar MA, Al Shehabi TS, Eid AH (2016) Inflammogenesis of secondary spinal cord injury. Front Cell Neurosci 10:98. 10.3389/fncel.2016.00098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsava EM, Gurer G, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Karatas H, Dalkara T (2009) A new model of transient focal cerebral ischemia for inducing selective neuronal necrosis. Brain Res Bull 78(4–5):226–231. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzarone M, De Troia A, Iazzolino L, Nabulsi B, Tecchio T (2016) Hybrid treatment of acute abdominal aortic thrombosis presenting with paraplegia. Ann Vasc Surg 33:228.e225-228. 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC (1995) A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma 12(1):1–21. 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MT, Puskas F, Bennett DT, Cleveland JC Jr, Herson PS, Mares JM, Meng X, Weyant MJ, Fullerton DA, Brett Reece T (2015) Clinical indicators of paraplegia underplay universal spinal cord neuronal injury from transient aortic occlusion. Brain Res 1618:55–60. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalala OG, Srikanth M, Kessler JA (2013) The emerging roles of microRNAs in CNS injuries. Nat Rev Neurol 9(6):328–339. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgens RB, Liu-Snyder P (2012) Understanding secondary injury. Q Rev Biol 87(2):89–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyaci MG, Eser O, Kocogullari CU, Karavelioglu E, Tokyol C, Can Y (2014) Neuroprotective effect of alpha-lipoic acid and methylprednisolone on the spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury in rabbits. Br J Neurosurg. 10.3109/02688697.2014.954986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YC, Roy S, Huang Y, Khanna S, Sen CK (2012) The microRNA miR-199a-5p down-regulation switches on wound angiogenesis by derepressing the v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1-matrix metalloproteinase-1 pathway. J Biol Chem 287(49):41032–41043. 10.1074/jbc.M112.413294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CZ, Yen CP, Winadi D, Wu SC, Howng SL, Lin TK, Jeng AY, Kassell NF, Kwan AL (2004) Neuroprotective effect of CGS 26303, an endothelin-converting enzyme inhibitor, on transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 44:S487–S489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi P, Chen NX, O’Neill K, McClintick JN, Moe SM, Janga SC (2015) Differential miRNA expression in cells and matrix vesicles in vascular smooth muscle cells from rats with kidney disease. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0131589. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SY, Wang SC, Lei M, Wang Z, Xiong K (2018) Regulatory role of calpain in neuronal death. Neural Regen Res 13(3):556–562. 10.4103/1673-5374.228762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou AK, Chen TI, Winardi W, Dai MH, Chen SC, Howng SL, Yen CP, Lin TK, Jeng AY, Kwan AL (2007) Functional neuroprotective effect of CGS 26303, a dual ECE inhibitor, on ischemic-reperfusion spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Biol Med 232(2):214–218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El AH, Leptidis S, Dirkx E, Hoeks J, Van BB, Brand K, Mcclellan EA, Poels E, Sluimer JC, Mm VDH (2013) The hypoxia-inducible microRNA cluster miR-199a∼214 targets myocardial PPARδ and impairs mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Cell Metab 18(3):341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang B, Li XQ, Bi B, Tan WF, Liu G, Zhang Y, Ma H (2015) Dexmedetomidine attenuates blood–spinal cord barrier disruption induced by spinal cord ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Cell Physiol Biochem 36(1):373–383. 10.1159/000430107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Liu J, Wang W, Hao F, Sun X, Wu X, Bu P, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu F, Zhang Q, Jiang F (2013) Alteration in abundance and compartmentalization of inflammation-related miRNAs in plasma after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 44(6):1739–1742. 10.1161/strokeaha.111.000835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Qiu Z, Wang Z, Wang Q, Tan N, Chen T, Chen Z, Huang S, Gu J, Li J, Yao M, Zhao Y, He X (2015) MiR-199a-5p is negatively associated with malignancies and regulates glycolysis and lactate production by targeting hexokinase 2 in liver cancer. Hepatology 62(4):1132–1144. 10.1002/hep.27929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi Gheinani A, Burkhard FC, Rehrauer H, Aquino Fournier C, Monastyrskaya K (2015) MicroRNA MiR-199a-5p regulates smooth muscle cell proliferation and morphology by targeting WNT2 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 290(11):7067–7086. 10.1074/jbc.M114.618694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Xiao J, Ren AJ, Zhang YF, Zhang H, Chen M, Xie B, Gao XG, Wang YW (2011) Role of miR-1 and miR-133a in myocardial ischemic postconditioning. J Biomed Sci 18:22. 10.1186/1423-0127-18-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henaoui IS, Cauffiez C, Aubert S, Buscot M, Dewaeles E, Copin MC, Marquette CH, Barbry P, Perrais M, Pottier N, Mari B (2013) [miR-199a-5p in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis]. Med Sci (Paris) 29(5):461–463. 10.1051/medsci/2013295006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkel R, Penzkofer D, Zühlke S, Fischer A, Husada W, Xu QF, Baloch E, Van RE, Zeiher AM, Kupatt C (2013) Inhibition of microRNA-92a protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a large-animal model. Circulation 128(10):1066–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Deng H, Xu S, Zhang J (2015) MicroRNAs regulate mitochondrial function in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Sci 16(10):24895–24917. 10.3390/ijms161024895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikpeze TC, Mesfin A (2017) Spinal cord injury in the geriatric population: risk factors, treatment options, and long-term management. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 8(2):115–118. 10.1177/2151458517696680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee MK, Jung JS, Choi JI, Jang JA, Kang KS, Im YB, Kang SK (2012) MicroRNA 486 is a potentially novel target for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Brain 135(Pt 4):1237–1252. 10.1093/brain/aws047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardes O, Civi S, Tufan K, Oz Oyar E, Omeroglu S, Aykol S (2016) Effects of atorvastatin on experimental spinal cord ischemia–reperfusion injury in rabbits. Turk Neurosurg. 10.5137/1019-5149.jtn.16627-15.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz S, Dehghani GA (2017) Cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in the hyperthyroid rat. Iran J Med Sci 42(1):48–56 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamaisi M, Toukan H, Axelrod JH, Rosenberger C, Skarzinski G, Shina A, Meidan R, Koesters R, Rosen S, Walkinshaw G, Mimura I, Nangaku M, Heyman SN (2015) Endothelin-converting enzyme is a plausible target gene for hypoxia-inducible factor. Kidney Int 87(4):761–770. 10.1038/ki.2014.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilany A, Al-Hashel JY, Rady A (2015) Acute aortic occlusion presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Case Rep Neurol Med 2015:713489. 10.1155/2015/713489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Xu J, Wang Y, Tang JY, Yang SL, Xiang HG, Wu SX, Li XJ (2018) Inhibition of MiRNA-125b decreases cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting CK2alpha/NADPH oxidase signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem 45(5):1818–1826. 10.1159/000487873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Detloff MR, Miller KN, Santi L, Houle JD (2012) Exercise modulates microRNAs that affect the PTEN/mTOR pathway in rats after spinal cord injury. Experimental neurology 233(1):447–456. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhao J, Zhang W, Gan J, Hu C, Huang G, Zhang Y (2015) lncRNA GAS5 enhances G1 cell cycle arrest via binding to YBX1 to regulate p21 expression in stomach cancer. Scientific reports 5:10159. 10.1038/srep10159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo MN, Khan RY, Wang Y, Tai SC, Chan GC, Cheung AH, Marsden PA (2001) Human endothelin converting enzyme-2 (ECE2): characterization of mRNA species and chromosomal localization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1522(1):46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv HR (2017) lncRNA-Map2k4 sequesters miR-199a to promote FGF1 expression and spinal cord neuron growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 490(3):948–954. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew B, Laden G (2015) Management of severe spinal cord injury following hyperbaric exposure. Diving Hyperb Med 45(3):210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HA, Kubicki N, Gnyawali S, Chan YC, Roy S, Khanna S, Sen CK (2011) Natural vitamin E alpha-tocotrienol protects against ischemic stroke by induction of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1. Stroke 42(8):2308–2314. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.608547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma HS (2005) Pathophysiology of blood–spinal cord barrier in traumatic injury and repair. Curr Pharm Des 11(11):1353–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui R, He Z (2014) Polymorphisms of ECE1 may contribute to susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Han Chinese of Northern China. Cell Biochem Biophys 69(2):237–246. 10.1007/s12013-013-9789-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhu J, Wu M, Sun H, Zhou C, Fu L, Xu C, Mei C (2015) Inhibition of MiR-199a-5p reduced cell proliferation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease through targeting CDKN1C. Med Sci Monit 21:195–200. 10.12659/MSM.892141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JF, Yang HL, Huang YH, Chen Q, Cao XB, Li DP, Shu HM, Jiang RY (2017) CaSR and calpain contribute to the ischemia reperfusion injury of spinal cord. Neurosci Lett 646:49–55. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson RA, Morton MT, Tsao-Wu G, Savalos RA, Davidson C, Sharp FR (1990) A semiautomated method for measuring brain infarct volume. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10(2):290–293. 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabayashi K, Takahashi G, Motoyoshi N, Kokubo H, Sakurai M, Oda K, Saiki Y, Iguchi A (2004) Spinal cord protection during most or all of descending thoracic or thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Kyobu Geka Jpn J Thoracic Surg 57(4):301–306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Soma S, Muramatsu M, Oka M, Fukuchi Y (2001) Upregulation of ET-1 and its receptors and remodeling in small pulmonary veins under hypoxic conditions. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280(6):L1104-1114. 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubbink DT, Jacobs MJ (2000) Spinal cord stimulation in critical limb ischemia. A review. Acta Chir Belg 100(2):48–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XT, Pei DS, Xu J, Guan QH, Sun YF, Liu XM, Zhang GY (2007) Opposing effects of Bad phosphorylation at two distinct sites by Akt1 and JNK1/2 on ischemic brain injury. Cell Signal 19(9):1844–1856. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yen H, Chen CH, Soni R, Jasani N, Sylvestre G, Reznik SE (2008) The endothelin-converting enzyme-1/endothelin-1 pathway plays a critical role in inflammation-associated premature delivery in a mouse model. Am J Pathol 173(4):1077–1084. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu H, Ma H (2016) Intrathecally transplanting mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) activates ERK1/2 in spinal cords of ischemia-reperfusion injury rats and improves nerve function. Med Sci Monit 22:1472–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Luo J, Wang X, Yang B, Cui L (2017) MicroRNA-199a-5p induced autophagy and inhibits the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis by modulating the mTOR signaling via directly targeting Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb). Cell Physiol Biochem 42(6):2481–2491. 10.1159/000480211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Pang QJ, Liu JT, Wu HH, Tao DY (2018) Down-regulated miR-448 relieves spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury by up-regulating SIRT1. Braz J Med Biol Res 51(5):e7319. 10.1590/1414-431X20177319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WH, Yao XY, Yu HJ, Huang JW, Cui LY (2012) Downregulation of miR-199a may play a role in 3-nitropropionic acid induced ischemic tolerance in rat brain. Brain Res 1429(1):116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Yokomizo Y, Akai T, Chiyoda T, Goto H, Masaki Y (2016) Acute aortic occlusion in a patient with chronic paralysis due to spinal cord injury: a case report. Surg Case Rep 2(1):121. 10.1186/s40792-016-0251-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Liu JX, Yan ZP, Yao XH, Liu XH (2015) Potential microRNA biomarkers for acute ischemic stroke. Int J Mol Med 36(6):1639–1647. 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Ma M, Liu B, Xia J, Xu H, Liu Y, Du X, Hu Z, Yang Q, Zhang L (2016) Association between ECE1 gene polymorphisms and risk of intracerebral haemorrhage. J Int Med Res 44(3):444–452. 10.1177/0300060516635385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK (2006) Phosphoinositide-3-kinase/akt survival signal pathways are implicated in neuronal survival after stroke. Mol Neurobiol 34(3):249–270. 10.1385/mn:34:3:249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]