Abstract

Carotid atherosclerosis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the carotid arterial wall, which is very important in terms of the occurrence of cerebral vascular accidents. Studies have demonstrated that microRNAs (miRNAs) and their target genes are involved in the formation of atherosclerosis and that atorvastatin might reduce atherosclerotic plaques by regulating the expression of miRNAs. However, the related mechanism is not yet known. In this study, we first investigated the effects of atorvastatin on miR-126 and its target gene, i.e., vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in apolipoprotein E-knockout (ApoE−/−) mice with carotid atherosclerotic plaque in vivo. We compared the expressions of miR-126 and VCAM-1 between the control, atherosclerotic model and atorvastatin treatment groups of ApoE−/− mice using RT-PCR and Western blot. We found the miR-126 expression was significantly down-regulated, and the VCAM-1 expression was significantly up-regulated in the atherosclerotic model group, which accelerated the progression of atherosclerosis in the ApoE−/− mice. These results following atorvastatin treatment indicated that miR-126 expression was significantly up-regulated, VCAM-1 expression was significantly down-regulated and atherosclerotic lesions were reduced. The present results might explain the mechanism by which miR-126 is involved in the formation of atherosclerosis in vivo. Our study first indicated that atorvastatin might exert its anti-inflammatory effects in atherosclerosis by regulating the expressions of miR-126 and VCAM-1 in vivo.

Keywords: Carotid atherosclerosis, miR-126, VCAM-1, Atorvastatin, Apolipoprotein E-knockout mice

Introduction

Carotid atherosclerosis is defined by the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in any segment of the carotid artery that could lead to the occurrence of a cerebral vascular accident (Li et al. 2013). In recent years, the rapid progress of molecular biology and molecular immunology and the improved understanding of the cytokines and chemical factors involved in atherosclerotic lesion formation have led to the general acceptance that atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease. However, the exact mechanisms have not been clearly explained (Jiang et al. 2013; Meister and Schmidt 2010). Studies have shown that the adhesions of mononuclear cells and endothelial cells are key links in the development of AS.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of short, non-protein coding, single-stranded small RNA molecules of approximately 22 nucleotides in length that can regulate the mRNA expressions of target genes and the activation of signaling pathways to influence cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis by binding to complementary sequences in the 3′-untranslated region (He and Hannon 2004; Shyu et al. 2008). Approximately one-third of human genes are regulated by miRNAs (Mendell 2008). Growing evidence suggests that miRNAs play important roles in diverse aspects of human diseases, such as metabolism, differentiation, apoptosis and atherosclerosis (Kosik 2006; Ying and Lin 2009). miR-126 is a type of specifically expressed miRNA in endothelial cells that can promote endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis (Harris et al. 2008; Deregibus et al. 2007), vascular integrity and endothelial repair (Wang et al. 2008; Fish et al. 2008). It has been found that the intravenous injection of miR-126 can inhibit the formation of AS in mice and decrease the areas of the atherosclerotic plaques (Zernecke et al. 2009).

VCAM-1 is the target gene of miR-126 that can be inhibited by miR-126 (Raitoharju et al. 2011). VCAM-1 is a major adhesion molecule among the vascular endothelial cell adhesion molecules and can promote leukocytes to adhere to endothelial cells, and the over-expression of VCAM-1 is a key step in the formation of AS (Kasper et al. 1996). In atherosclerotic diseases, low expression of miR-126 may reduce the inhibitory effect on VCAM-1 expression, which therefore cannot inhibit the accumulation of inflammatory cells, which in turn leads to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques (Harris et al. 2008; Schmitz et al. 2013). However, studies of the relationship between miR-126 and VCAM-1 in atherosclerotic diseases in vivo are rare.

It has been gradually recognized that statins have lipid-lowering and plaque stabilizing effects (Schmidt-Lucke et al. 2010). Furthermore, the effects that might inhibit inflammatory reactions have drawn wide attention in recent years (Holmberg et al. 2011; Zheng et al. 2010). Many studies have found that atorvastatin could be anti-inflammatory in terms of many mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 and NF-κB (Mendell 2008; Bespalova et al. 2014; Chu et al. 2015; Ekstrand et al. 2015; Pathak et al. 2015). Previous studies have shown that atorvastatin can affect the expressions of the endothelial cell adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular endothelial-cadherin (Li et al. 2014; Khanicheh et al. 2013; Ajamieh et al. 2012). Recently, many studies have also shown that atorvastatin can alter the expression of miRNAs in atherosclerotic mice with cardiac hypertrophy and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Niesor et al. 2015; Tu et al. 2013; Minami et al. 2009). However, there are no reports about the effects of atorvastatin on miR-126 and VCAM-1 in vivo.

In our study, we chose the ApoE−/− mouse model, which is widely used, targets the deletion of the ApoE gene and subsequently leads to the development of initial fatty streaks to complex lesions over time and accelerates the development of AS following the administration of a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet (Breslow 1996; Scalia et al. 2001). This model has been widely used to assess the anti-atherogenic properties of statins (Sparrow et al. 2001; Ekstrand et al. 2015). A perivascular collar was placed around the carotid artery to form atherosclerotic vascular lesions. This method has been widely used to establish the atherosclerotic models (Li et al. 2015; Cai et al. 2015). In the present study, we investigated the following issues: (1) whether miR-126 affects atherosclerotic lesions by regulating VCAM-1 expression in ApoE−/− mice in vivo, and (2) whether the anti-inflammatory mechanism of atorvastatin is mediated by the regulation of the expressions of miR-126 and VCAM-1 in vivo. These experiments were necessary to explore the anti-atherosclerotic mechanism of atorvastatin.

Materials and Methods

Animal Models

Thirty-six 8-week-old male ApoE−/− C57BL/6J mice (weighing 18 to 22 g) were purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd. All ApoE−/− mice were housed in the Qingdao University laboratory (12-h light/12-h dark cycle, 22 °C room temperature). All the experimental procedures in our study involving animals were designed to minimize suffering and were in accordance with the ethical standards of Qingdao University.

The mice were randomly divided into one of the following three groups (n = 12 per group): (i) the control group (C), (ii) the model group (M), and (iii) the atorvastatin group (A). At the first week, all of the ApoE−/− mice were fed with normal food. From the second week, the ApoE−/− mice were fed with normal food in the control group, and the others were fed with a high-fat diet (0.25 % cholesterol, 15 % cocoa butter and basic diet, License No.: SCXK-Beijing-2014-0008, China) in the model and atorvastatin groups (van der Sluis et al. 2014; Cai et al. 2015). At the third week, the ApoE−/− mice in the model and atorvastatin groups underwent operations in which a perivascular collar was placed around right common carotid artery as described previously (von der Thusen et al. 2001). The ApoE−/− mice in the control group underwent sham operations. From the seventh week, the ApoE−/− mice were gavaged with atorvastatin (10 mg/kg*days) once per day, and the ApoE−/− mice in the model group were gavaged with physiological saline once per day (Delsing et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2015). All of the ApoE−/− mice had free access to water. Atorvastatin was provided by Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals (New York, USA). After 8 weeks of operation, all of the ApoE−/− mice were sacrificed, and the right common carotid arteries and blood were collected for further analysis.

Lipid Analysis

Blood was collected from the femoral artery. The serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) were determined in each of the three groups.

Histopathological Analysis

In all mice, successive transverse cryosections of 5 µm in thickness from the right common carotid arteries were obtained and selectively stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) at 50-µm intervals. The size of the patch area was determined with a pathological image analyzer. The ratios of the atherosclerotic plaque area to the lumen area were analyzed with Pro-Plus-6 imaging software.

Total RNA Extraction and RT-PCR Analysis

The total RNA was extracted from the right common carotid arteries of the ApoE−/− mice with Trizol (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Real time-polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCRs) were performed to determine the gene expression of miR-126, VCAM-1 and GAPDH. The primer sequences were as follows: miRNA-126-5p (71 bp):5′-CCG GCA TTA TTA CTT TTG GTA CG-3′; VCAM-1(118 bp):forward, 5′-CCC AAA CAG AGG CAG AGT GT-3′, reverse 5′-AGC AGG TCA GGT TCA CAG GA-3′; the internal reference of miR-126 was U6; and the internal reference for VCAM-1 was GAPDH: forward, 5′-AAC AGC CTC AAG ATCATC AGC AA-3′, reverse, 5′-GAC TGT GGT CAT GAG TCC TTC CA-3′. The reaction conditions were as follows: miR-126; initial denaturation step for 30 s at 95 °C, denaturing at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing and elongation 30 s at 60 °C for 45 cycles. VCAM-1; initial denaturation step for 30 s at 95 °C, denaturing at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55 °C for 20 s, and elongation 20 s at 55 °C for 35 cycles. The method was applied to compare the relative expression results.

Western Blot Analysis

The carotid arteries (0.1 g) were homogenized in lysis buffer on an ice-bath until the tissue was completely uniform. The lysate was centrifuged at 1.2 kr/min for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. The total protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid method. The total protein was added to 2× SDS buffer solution and denatured by heating at 100 °C for 10 min. The protein samples (20 µg) were separated by 10 % sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5 % nonfat milk for 2.5 h at room temperature, followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with the following appropriate primary antibodies: anti-β-actin antibody (1:3500; Boster, Wuhan, China) and anti-VCAM-1 antibody (1:1500; Abcam). After incubation with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature, the membranes were determined with chemiluminescent substrate (Boster, Wuhan, China).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 19.0 software. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistically significant differences between groups were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the ApoE−/− Mice and Lipid Levels in the Three Groups

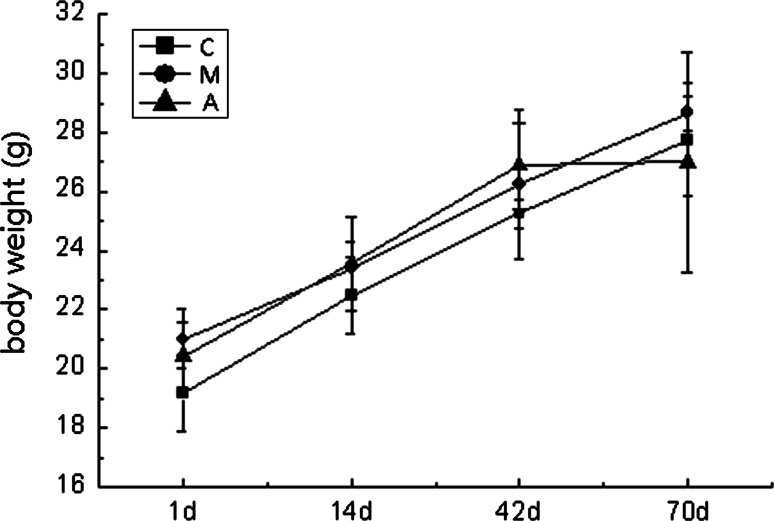

There were no significant differences in terms of body weight between the three groups at time points. After 9 weeks of consuming a high-fat diet, the TC, TG and LDL-c levels in the model group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.05), but the levels of HDL-c were not significantly different (P > 0.05). Compared with the model group, the levels of TC, TG, LDL-c and HDL-c were not significantly different in the atorvastatin group (P > 0.05) (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the ApoE−/− mice and lipid levels in the three groups ()

| Body weight (g) | TC | TG | LDL-c | HDL-c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day | 14 days | 42 days | 70 days | (mmol/L) | (mmol/L) | (mmol/L) | (mmol/L) | |

| Control group | 19.20 ± 1.30 | 22.50 ± 1.29 | 25.25 ± 0.50 | 27.75 ± 1.89 | 13.06 ± 1.72 | 2.19 ± 0.11 | 1.03 ± 0.12 | 1.77 ± 0.37 |

| Model group | 21.00 ± 1.00 | 23.40 ± 0.89 | 26.25 ± 2.52 | 28.67 ± 0.58 | 24.72 ± 2.30* | 2.73 ± 0.23* | 4.62 ± 0.14* | 1.34 ± 0.18 |

| Statin group | 20.43 ± 1.13 | 23.56 ± 1.59 | 26.88 ± 1.46 | 27.00 ± 3.74 | 24.59 ± 0.73 | 2.61 ± 0.17 | 3.87 ± 0.59 | 1.59 ± 0.26 |

* P < 0.05 versus the value of the control group

Fig. 1.

Body weight of the ApoE−/− mice in the three groups at time points. Mean ± SD for the body weight was measured. The body weight between the three groups were not significantly different (P > 0.05)

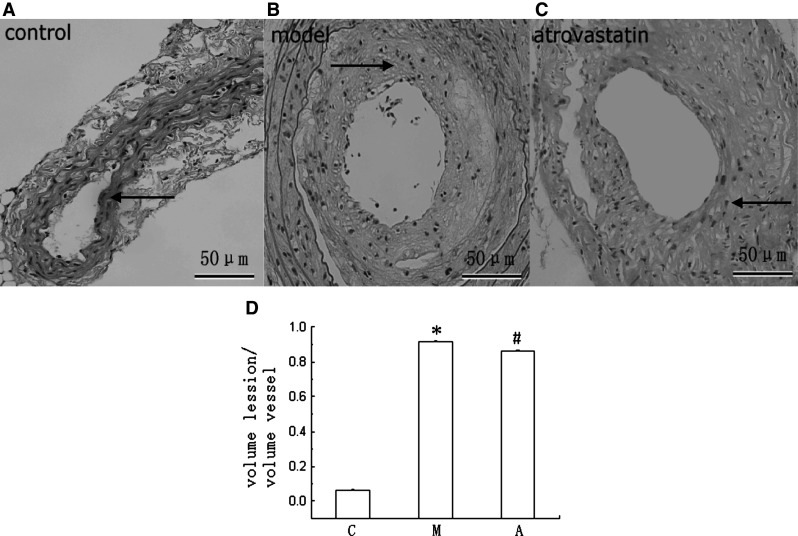

Pathological Diagnosis of the Carotid Arteries in the ApoE−/− Mice

Pathological diagnosis of vascular tissue was significantly different between the three groups. After 8 weeks of operation, no significant plaques were observed in the control group, and significant plaques were observed near the intima in the model group. However, the intima was significantly thickened and relatively complete in the atorvastatin group. The degree of lesioning in the atorvastatin group was significantly lower than that in the model group. The ratios of the atherosclerotic plaque area to the lumen area were significantly different between the three groups. Compared with the control group, the ratio was markedly increased in the model group (P < 0.05); however, the ratio was markedly decreased in the atorvastatin group compared with the model group (P < 0.05). These results indicated that atorvastatin could reduce atherosclerotic progression in the atherosclerotic plaques of the ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pathological diagnosis of the vascular tissue and comparison of the ratios in the atherosclerotic plaque area to the lumen area. The presence of AS was confirmed by pathological analysis of the vascular tissue. Representative images are shown (×400 magnification). Scale bars 50 μm. In the control group, there was no significant plaque, and vascular intima was complete (a). In the model group, there were numerous necrotic tissues, foam cells, and cholesterol crystals under the incomplete intima, and the intimal integrity was destroyed (b). In the atorvastatin group, there were small numbers of foam cells and relatively complete intima (c). The ratios of the atherosclerotic plaque area to the lumen area were analyzed with the Pro-Plus-6 software, which were significantly different between the three groups (d). *P < 0.01 versus the value of the control group. # P < 0.01 versus the value of the model group

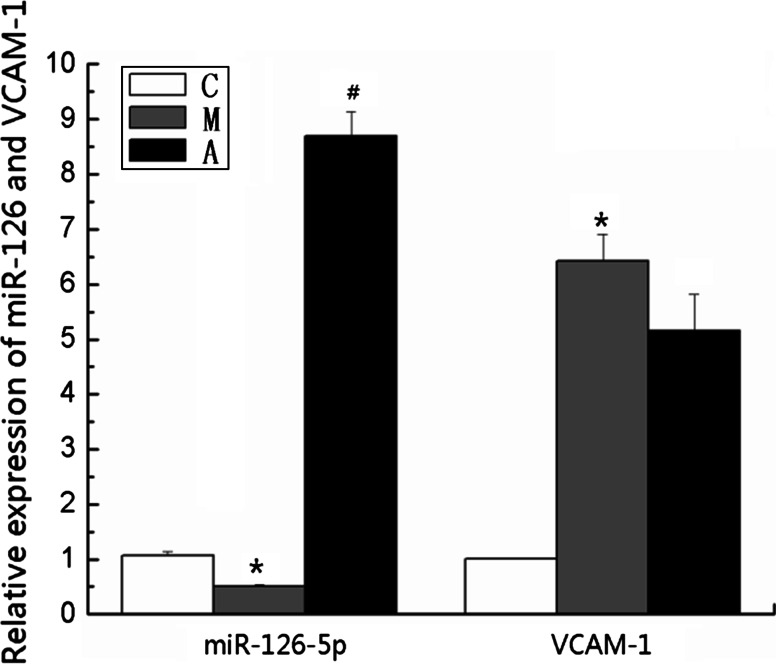

RT-PCR Analyses of miR-126 and VCAM-1 mRNA Expressions

The results revealed that the miR-126 mRNA expression decreased significantly, and the VCAM-1 mRNA expression increased significantly compared with the control group (control group vs. model group: miR-126, 1.07 ± 0.07 vs. 0.50 ± 0.03, P < 0.01; VCAM-1, 1.01 ± 0.01 vs. 6.42 ± 0.49, P < 0.01). The miR-126 mRNA expression was significantly up-regulated, and the VCAM-1 mRNA expression was not significantly down-regulated compared with the model group (model group vs. atorvastatin group: miR-126, 0.50 ± 0.03 vs. 8.69 ± 0.44, P < 0.01; VCAM-1, 6.42 ± 0.49 vs. 5.15 ± 0.66, P > 0.05). These data indicated that the down-regulated expression of miR-126 and the up-regulated expression of VCAM-1 were involved in atherosclerotic formation and that treatment with atorvastatin regulated the level of miR-126 mRNA expression (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Expressions of miR-126 and VCAM-1 mRNAs. The expressions of miR-126 and VCAM-1 mRNAs were analyzed by RT-PCR in the three groups. Values are presented as mean ± SD, n = 6. *P < 0.01 versus the value of the control group. # P < 0.01 versus the value of the model group

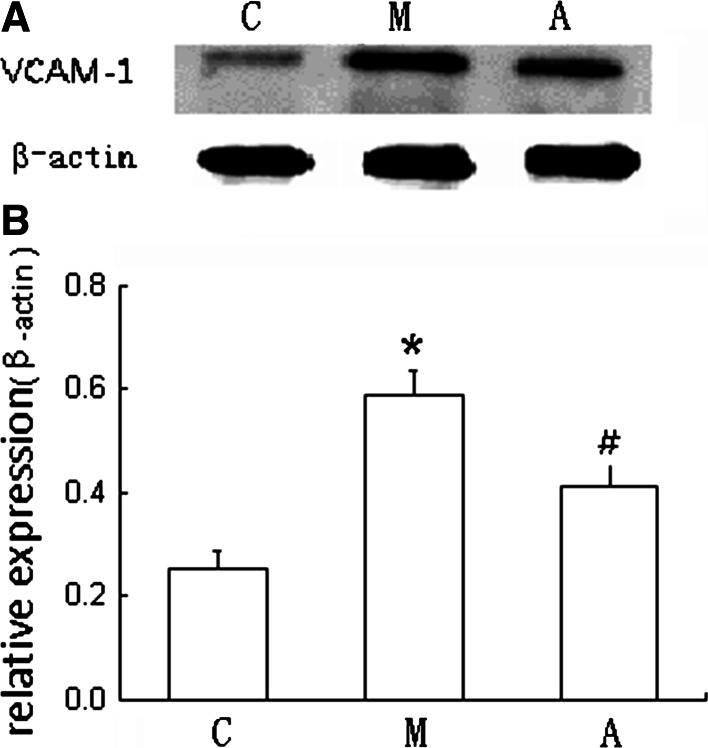

Western Blot Analysis of VCAM-1 Protein Expression

Compared with the control group, the level of VCAM-1 protein expression was significantly increased in the model group (P < 0.01). Compared with the model group, the VCAM-1 protein expression was significantly decreased in the atorvastatin group (P < 0.01). These data revealed that miR-126 could eventually inhibit VCAM-1 expression at the level of translation. Treatment with atorvastatin decreased the level of VCAM-1 expression and reduced the atherosclerotic lesions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

VCAM-1 protein expression was measured by Western blot. Fusion FX (Vilber, France) was used to acquire the images, and the results were analyzed with Image J. The target proteinases were expressed as the ratio of the integrated densities of the target gene and the β-actin band. Values are presented as mean ± SD, n = 6. a Densitometric measurements of VCAM-1 from the Western blots. The β-actin was performed as a control; b One representative result of the Western blots of VCAM-1 was shown. *P < 0.01 versus the value of the control group. # P < 0.01 versus the value of the model group

Discussion

Recently, increasing numbers of studies have demonstrated that miRNAs are important in the occurrence of AS; however, the mechanisms of miRNA-mediated pathological processes remain unclear. miR-126 can play an important role in the process of angiogenesis (Urbich et al. 2008; Jansen et al. 2013). In our previous study, we found that the expression of miR-126 was significantly lower in the large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) stroke patients than that in the healthy checkup subjects (Zhong et al. 2015). Studies have suggested that miR-126 plays a critical role in the formation of AS (Sun et al. 2012; Tian et al. 2015). However, studies of the relationship between miR-126 and VCAM-1 in atherosclerotic diseases in vivo are very rare.

Our results demonstrated that the carotid atherosclerotic plaque areas in the model group were significantly greater than those in the control group. In the model group, miR-126 expression was significantly decreased, and VCAM-1 expression was significantly increased. Therefore, we speculate that miR-126 might promote the development of AS by regulating the expression of VCAM-1. A previous study demonstrated that high-fat feeding in a rabbit atherosclerotic model resulted in a significant reduction in the miR-126 expression and an elevation of VCAM-1 expression, which indicates that low expression of miR-126 could lead to the over-expression of VCAM-1; therefore, these factors are related to the development of atherosclerotic plaques (Tian et al. 2015). Our results also indicated that VCAM-1, which is a target gene of miR-126, was up-regulated by the down-regulation of the expression of miR-126 in the carotid atherosclerotic ApoE−/− mice in vivo. Moreover, one study found that in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, decreases in the level of expression miR-126 result in significant increases in the expression level of VCAM-1. In contrast, increases in the expression of miR-126 lead to significant decreases in the expression level of VCAM-1; therefore, miR-126 might regulate VCAM-1 expression and control the inflammatory response of vascular endothelial cells in vitro (Harris et al. 2008). Another study also found that in human endothelial cells, miR-126 is over-expressed following long-term laminar shear stress, and this over-expression has a role in down-regulation of VCAM-1, which is involved in AS (Mondadori dos Santos et al.2015). These studies demonstrated that miR-126 and VCAM-1 are involved in the development of AS in vivo and in vitro and might promote the endothelial cell inflammatory reaction and the progression of AS.

Statins are 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors that can limit synthesis of endogenous cholesterol. In addition to lipid lowering effects, statins also have non-lipid regulating functions, such as protecting endothelial cell function, inhibiting inflammatory reactions, oxidation resistance, etc. (Elewa et al. 2010; Zhou and Liao 2010; Antoniades et al. 2011; Schmidt-Lucke et al. 2010). However, the anti-inflammatory properties mechanisms of statins have not yet been explained clearly. This study was the first to investigate the effects of atorvastatin on the expressions of miR-126 and VCAM-1 in vivo, which was very necessary to explore the mechanisms of statins action in the anti-inflammatory reaction of AS.

In this study, we found that the carotid atherosclerotic lesions were significantly reduced in the atorvastatin group. Simultaneously, we also found that there was a significant up-regulation of miR-126 expression and a significant down-regulation of VCAM-1 protein expression in the atorvastatin group. Our data indicated that miR-126 eventually inhibited VCAM-1 expression at the level of translation. One study has also found that endogenous miR-126 inhibited VCAM-1 protein expression but not mRNA levels in endothelial cells (Harris et al. 2008). We conclude that atorvastatin might increase the expression of miR-126 to inhibit the expression of VCAM-1 and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. One study of statins and miR-126 revealed that in the atherosclerotic model of ApoE-null mice on a high-fat diet, the expression of miR-126 was significantly increased, and the vascular endothelial tissues improved in the simvastatin treatment group compared with the control group (Wu et al. 2014). Another study of statins and miR-126 found that the expression of miR-126 was significantly decreased in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) from coronary artery disease (CAD) patients; however, this expression level was not affected by atorvastatin treatment (Zhang et al. 2011). The difference between these two observations might be explained by the different in vivo and in vitro experimental designs and particularly by the different methods of atorvastatin administration. The metabolic products following the oral administration of atorvastatin might also affect intracellular miRNA levels (Black et al. 1999).

Our study also found that the blood lipid levels were not significantly different between the atorvastatin and model groups. It is important to note that the plasma cholesterol-lowering effect of statins results mainly from an enhanced hepatic uptake of LDL via upregulation of LDL receptor expression and to a lesser extent from a reduced endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis (Miida et al. 2004; Zadelaar et al. 2007). ApoE has an important role in LDL receptor function, which is lack to cause a decrease in LDL receptors; thus, the blood lipid levels in the atorvastatin group did not decrease significantly. ApoE−/− mice were used in our study, which sought to investigate the anti-atherogenic effects of atorvastatin despite the absence of a hypocholesterolemic effect. Simvastatin treatment of ApoE−/− mice also has no effect on plasma lipids (Sparrow et al. 2001).

In conclusion, our study found that the decreased expression of miR-126 might lead to an increase in the expression of VCAM-1 and promote the formation of AS in ApoE−/− mice with carotid atherosclerotic plaques in vivo, which suggests that miR-126 might play an important role in the development of AS. Our study first found that atorvastatin had positive effects on the up-regulation of miR-126 expression and the down-regulation of VCAM-1 expression, which might decrease the adhesion between leukocytes and endothelial cells and might therefore reduce the formation of AS. Our study demonstrated for the first time that atorvastatin might exert its anti-inflammatory effects by increasing miR-126 expression and decreasing VCAM-1 expression in vivo, which will be a great aid in illustrating the manner in which atorvastatin works to treat atherosclerosis in the human body.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (No. 81571112).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could have inappropriately influenced our work. There are no professional or other personal interests of any nature or type in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the positions presented in this manuscript.

References

- Ajamieh H, Farrell G, Wong HJ et al (2012) Atorvastatin protects obese mice against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by Toll-like receptor-4 suppression and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27(8):1353–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades C, Bakogiannis C et al (2011) Rapid, direct effects of statin treatment on arterial redox state and nitric oxide bioavailability in human atherosclerosis via tetrahydrobiopterin-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling. Circulation 124(3):335–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bespalova ID, Riazantseva NV et al (2014) Effect of atorvastatin on pro-inflammatory status (in vivo and in vitro) in patients with essential hypertension and metabolic syndrome. Kardiologiia 54(8):37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black AE, Hayes RN et al (1999) Metabolism and excretion of atorvastatin in rats and dogs. Drug Metab Dispos 27(8):916–923 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow JL (1996) Mouse models of atherosclerosis. Science 272(5262):685–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Li X et al (2015) Adiponectin reduces carotid atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE−/− mice: roles of oxidative and nitrosative stress and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Mol Med Rep 11(3):1715–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu LW, Chen JY et al (2015) Atorvastatin prevents neuroinflammation in chronic constriction injury rats through nuclear NFkappaB downregulation in the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord. ACS Chem Neurosci 6(6):889–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delsing DJ, Jukema JW et al (2003) Differential effects of amlodipine and atorvastatin treatment and their combination on atherosclerosis in ApoE*3-Leiden transgenic mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 42(1):63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V et al (2007) Endothelial progenitor cell derived microvesicles activate an angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of mRNA. Blood 110(7):2440–2448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand M, Gustafsson Trajkovska M et al (2015) Imaging of intracellular and extracellular ROS levels in atherosclerotic mouse aortas ex vivo: effects of lipid lowering by diet or atorvastatin. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0130898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elewa HF, El-Remessy AB et al (2010) Diverse effects of statins on angiogenesis: new therapeutic avenues. Pharmacotherapy 30(2):169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JE, Santoro MM et al (2008) miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev Cell 15(2):272–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TA, Yamakuchi M et al (2008) MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(5):1516–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Hannon GJ (2004) MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet 5(7):522–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg R, Refai E et al (2011) Lowering apolipoprotein CIII delays onset of type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(26):10685–10689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen F, Yang X et al (2013) Endothelial microparticle-mediated transfer of MicroRNA-126 promotes vascular endothelial cell repair via SPRED1 and is abrogated in glucose-damaged endothelial microparticles. Circulation 128(18):2026–2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Ge X et al (2013) MicroRNA-281 regulates the expression of ecdysone receptor (EcR) isoform B in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 43(8):692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper HU, Schmidt A et al (1996) Expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM, VCAM, and ELAM in the arteriosclerotic plaque. Gen Diagn Pathol 141(5–6):289–294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanicheh E, Mitterhuber M, Xu L et al (2013) Noninvasive ultrasound molecular imaging of the effect of statins on endothelial inflammatory phenotype in early atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 8(3):e58761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik KS (2006) The neuronal microRNA system. Nat Rev Neurosci 7(12):911–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LX, Zhao CC et al (2013) Prevalence and clinical characteristics of carotid atherosclerosis in newly diagnosed patients with ketosis-onset diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 12:18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Wu XW, Lu WH et al (2014) Effect of atorvastatin on the expression of gamma-glutamyl transferase in aortic atherosclerotic plaques of apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14:145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wang Z, Wang C et al (2015) Perivascular adipose tissue-derived adiponectin inhibits collar-induced carotid atherosclerosis by promoting macrophage autophagy. PLoS ONE 10(5):e0124031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister J, Schmidt MH (2010) miR-126 and miR-126*: new players in cancer. ScientificWorldJournal 10:2090–2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JT (2008) miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell 133(2):217–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miida T, Hirayama S et al (2004) Cholesterol-independent effects of statins and new therapeutic targets: ischemic stroke and dementia. J Atheroscler Thromb 11(5):253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami Y, Satoh M et al (2009) Effect of atorvastatin on microRNA 221/222 expression in endothelial progenitor cells obtained from patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest 39(5):359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondadori dos Santos A, Metzinger L et al (2015) miR-126 is involved in vascular remodeling under laminar shear stress. Biomed Res Int 2015:497280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesor EJ, Schwartz GG, Perez A et al (2015) Statin-induced decrease in ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression via microRNA33 induction may counteract cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoprotein. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 29(1):7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak NN, Lingaraju MC et al (2015) Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects of atorvastatin in a cartilage explant model of osteoarthritis. Inflamm Res 64(3–4):161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitoharju E, Lyytikainen LP et al (2011) miR-21, miR-210, miR-34a, and miR-146a/b are up-regulated in human atherosclerotic plaques in the Tampere vascular study. Atherosclerosis 219(1):211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalia R, Gooszen ME et al (2001) Simvastatin exerts both anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 103(21):2598–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Lucke C, Fichtlscherer S et al (2010) Improvement of endothelial damage and regeneration indexes in patients with coronary artery disease after 4 weeks of statin therapy. Atherosclerosis 211(1):249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz B, Vischer P et al (2013) Increased monocyte adhesion by endothelial expression of VCAM-1 missense variation in vitro. Atherosclerosis 230(2):185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu AB, Wilkinson MF et al (2008) Messenger RNA regulation: to translate or to degrade. EMBO J 27(3):471–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow CP, Burton CA et al (2001) Simvastatin has anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic activities independent of plasma cholesterol lowering. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21(1):115–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Alkhoury K et al (2012) IRF-1 and miRNA126 modulate VCAM-1 expression in response to a high-fat meal. Circ Res 111(8):1054–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian HS, Zhou QG et al (2015) Relationship between arterial atheromatous plaque morphology and platelet-associated miR-126 and miR-223 expressions. Asian Pac J Trop Med 8(4):309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Wan L et al (2013) MicroRNA-22 downregulation by atorvastatin in a mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy: a new mechanism for antihypertrophic intervention. Cell Physiol Biochem 31(6):997–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbich C, Kuehbacher A et al (2008) Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res 79(4):581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis RJ, van den Aardweg T et al (2014) Prolactin receptor antagonism uncouples lipids from atherosclerosis susceptibility. J Endocrinol 222(3):341–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Thusen JH, van Berkel TJ et al (2001) Induction of rapid atherogenesis by perivascular carotid collar placement in apolipoprotein E-deficient and low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation 103(8):1164–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Aurora AB et al (2008) The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell 15(2):261–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XD, Zeng K et al (2014) Effect of aerobic exercise on miRNA-TLR4 signaling in atherosclerosis. Int J Sports Med 35(4):344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZR, Li JY et al (2015) Apple polyphenols decrease atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis in ApoE−/− mice through the ROS/MAPK/NF-kappaB pathway. Nutrients 7(8):7085–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying SY, Lin SL (2009) Intron-mediated RNA interference and microRNA biogenesis. Methods Mol Biol 487:387–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadelaar S, Kleemann R et al (2007) Mouse models for atherosclerosis and pharmaceutical modifiers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(8):1706–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K et al (2009) Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2(100):ra81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Kandic I et al (2011) Dysregulation of angiogenesis-related microRNAs in endothelial progenitor cells from patients with coronary artery disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 405(1):42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Khoo C et al (2010) Apolipoprotein C-III and the metabolic basis for hypertriglyceridemia and the dense low-density lipoprotein phenotype. Circulation 121(15):1722–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong QW, Ma AJ, Pan XD, Yang SN, Wang L, Zhang Z, Pang M (2015) Analysis of plasma miRNAs expression profile in different subtypes of ischemic stroke. Chin J Neurol 2015:114–119. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7876.2015.02.009 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Liao JK (2010) Pleiotropic effects of statins. Basic research and clinical perspectives. Circ J 74(5):818–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]