Abstract

Cardiolipin, an anionic phospholipid found primarily in the inner mitochondrial membrane, has many well-defined roles within the peripheral tissues, including the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane fluidity and the regulation of mitochondrial functions. Within the central nervous system (CNS), cardiolipin is found within both neuronal and non-neuronal glial cells, where it regulates metabolic processes, supports mitochondrial functions, and promotes brain cell viability. Furthermore, cardiolipin has been shown to act as an elimination signal and participate in programmed cell death by apoptosis of both neurons and glia. Since cardiolipin is associated with regulating brain homeostasis, the modification of its structure, or even a decrease in the overall levels of cardiolipin, can result in mitochondrial dysfunction, which is a characteristic feature of many diseases. In this review, we outline the various functions of cardiolipin within the cells of the CNS, including neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. In addition, we discuss the role cardiolipin may play in the pathogenesis of the neurodegenerative disorders Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, as well as traumatic brain injury.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Glia, Mitochondria, Neurons, Parkinson’s disease, Traumatic brain injury

Introduction

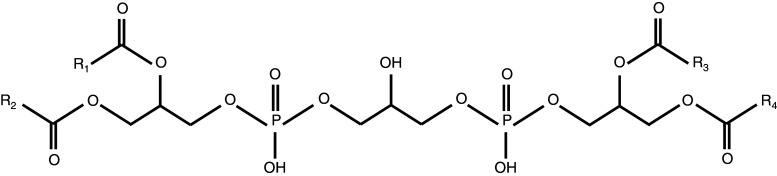

Cardiolipin is an anionic phospholipid with a distinctive structure consisting of a double glycerophosphate backbone and four fatty acid side chains (Fig. 1). This structure differs from the single glycerophosphate backbone and two fatty acid side chains found in most phospholipids that form cellular membranes (Li et al. 2015; Pope et al. 2008). Within mammalian cells, cardiolipin is primarily located in the inner leaflet of the inner mitochondrial membrane (Chicco and Sparagna 2007; Mejia et al. 2014). Due to its unique structure, cardiolipin possesses a conical shape within the lipid bilayer, a configuration that contributes to its ability to interact with a large array of proteins located both inside and outside of the mitochondria (Schlame et al. 2000). Moreover, the distinctive structure of cardiolipin has been shown to increase pressure around the fatty acid chain region of the lipid bilayer (Sathappa and Alder 2016), a characteristic feature that allows cardiolipin to participate in the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane fluidity. Cardiolipin also regulates various mitochondrial processes, including the electron transport chain and programmed cell death, otherwise known as apoptosis (Chicco and Sparagna 2007; Paradies et al. 2011; Peyta et al. 2016; Robinson 1993).

Fig. 1.

Structure of cardiolipin; R fatty acid side chains

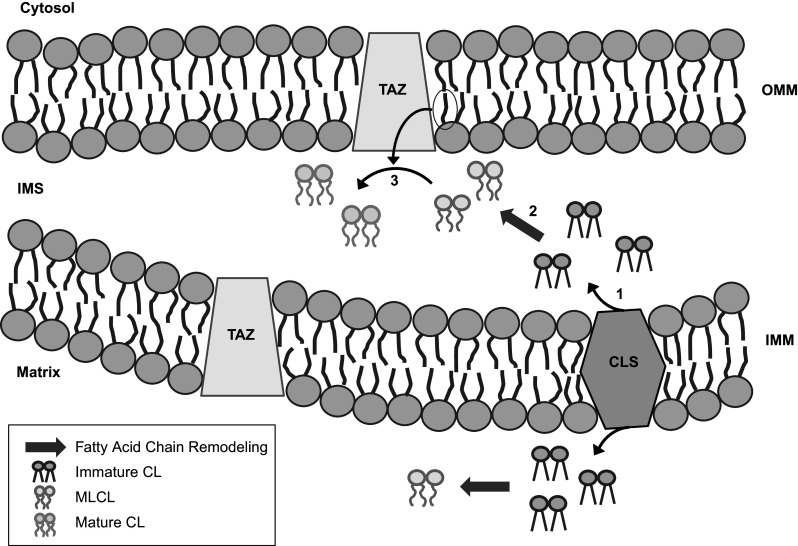

As its name suggests, cardiolipin was discovered and is most abundant in the mammalian heart, and, for this reason, has mainly been studied for its functions in the peripheral tissues (Schlame et al. 2000). In particular, cardiolipin is extensively researched with respect to Barth syndrome, a rare X-linked genetic disorder that results in cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, neutropenia, and eventually heart failure and/or death (Sandlers et al. 2016; Saric et al. 2015). Barth syndrome can be caused by a variety of mutations, including frame shift, missense, loss-of-function, and splice-site mutations (Lu et al. 2016; Whited et al. 2013), in the tafazzin (TAZ) gene. Mutations in this gene result in a deficiency in the enzyme TAZ, which acts as a cardiolipin transacylase and is responsible for the fatty acid chain remodeling that occurs during the final stages of cardiolipin biosynthesis (Saric et al. 2015; Thompson et al. 2016; Whited et al. 2013). TAZ is required for the production of mature tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin, the species found most abundantly in the heart, which is generated from nascent monolysocardiolipin (Schlame 2013). Monolysocardiolipin, a tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin precursor molecule, is synthesized following fatty acid tail remodeling of immature cardiolipin, which is originally produced by cardiolipin synthase (Lu and Claypool 2015; Fig. 2, see Mejia et al. (2014) for the full biosynthetic pathway). Without functional TAZ, alterations in the fatty acid chain structure of monolysocardiolipin do not occur, which thereby results in increased levels of monolysocardiolipin, reduced levels of mature tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin, as well as an abnormal remodeling of the fatty acid tails of cardiolipin (Ikon et al. 2015; Sandlers et al. 2016; Saric et al. 2015; Vreken et al. 2000). Reduced TAZ activity has been found to severely impact all cardiolipin-related functions, which ultimately results in the down-regulation of mitochondrial processes, including the assembly of the electron transport chain, mitophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis (Gaspard and McMaster 2015; Hsu et al. 2015; Peyta et al. 2016). Thompson et al. (2016) demonstrated that an increased ratio of monolysocardiolipin to cardiolipin, which has been measured in both blood and tissue samples, strongly impacts the clinical status and presentation of symptoms in patients with Barth syndrome. Furthermore, it was determined that an increase in the ratio of monolysocardiolipin to mature cardiolipin could be used as a biomarker for diagnostic purposes, as well as for long-term monitoring of disease progression in patients with Barth syndrome (Thompson et al. 2016).

Fig. 2.

During the final stages of cardiolipin (CL) biosynthesis, its immature form, which is produced following the activity of cardiolipin synthase (CLS), undergoes fatty acid chain remodeling, thereby resulting in the generation of monolysocardiolipin (MLCL). Following its formation, MLCL is reacylated by tafazzin (TAZ), an enzyme that utilizes acyl chains donated from surrounding phospholipids to produce the mature form of CL. IMS intermembrane space, IMM inner mitochondrial membrane, OMM outer mitochondrial membrane

In this review, we will outline the emerging roles cardiolipin may perform within the various cell types of the central nervous system (CNS), including neurons and non-neuronal glial cells. Furthermore, we will discuss possible contributions of cardiolipin to the development and progression of various brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), as well as traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Cardiolipin in the Central Nervous System

In the peripheral tissues, tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin, which contains four fatty acid side chains with 18 carbon molecules and 2 double bonds (18:2) each, is the most prevalent form of cardiolipin (Cheng et al. 2008; Schlame et al. 2000); however, this is not the case in the CNS, where there are over one hundred different molecular species of cardiolipin, each containing a unique length or degree of unsaturation in their fatty acid tails (Cheng et al. 2008; Kiebish et al. 2009). Studies have shown that the most prevalent forms of cardiolipin in the brain contain palmitic (16:0), stearic (18:0), oleic (18:1), and arachidonic (20:4) fatty acid chains (Mancuso et al. 2009; Yabuuchi and O’Brien 1968).

The various molecular forms of cardiolipin are widely distributed throughout the CNS, where they support mitochondrial functions, metabolic processes, and brain cell viability (Cheng et al. 2008). Within the brain, cardiolipin is found in two different types of mitochondria: synaptic and non-synaptic. Synaptic mitochondria are located in the axon terminals of neurons, whereas non-synaptic mitochondria are located in the cell bodies of neurons and glia. This mitochondrial heterogeneity is not only due to their distinct cellular location, but also partially due to variations in the composition of the mitochondrial lipid membrane, which result in disparities of specific mitochondrial processes (Kiebish et al. 2008; Lai et al. 1977). For example, previous studies have revealed that synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria are characterized by differences in the activity of enzymes involved in the citric acid cycle, as well as in the rates of oxidation of various substrates, including the oxidation of pyruvate and citrate (Lai et al. 1977). This disparity in mitochondrial activity may be due to differential mitochondrial membrane composition, as synaptic mitochondrial membranes are composed of approximately 8% cardiolipin, whereas non-synaptic mitochondrial membranes are composed of up to 15% cardiolipin (Ruggiero et al. 1992).

Cellular Locations of Cardiolipin in the CNS

The two main cell types within the CNS include neurons and glia. Neurons are critical for electrochemical signal transmission and information processing (Breedlove and Watson 2013). The main types of glia, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia, provide structural, chemical, and nutritional support to neurons and are critical for maintaining brain homeostasis (Jessen 2004; Lull and Block 2010). Astrocytes, which contain long processes that extend from the cell body, are involved in the formation of synapses, regulation of synaptic transmission, and recycling of neurotransmitters (Eddleston and Mucke 1993; Meyer and Kaspar 2016). These long extensions also participate in the maintenance of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and chemical homeostasis of the extracellular environment (Kettenmann and Verkhratsky 2008; Nedergaard et al. 2003). Oligodendrocytes form the myelin sheath, which is an insulating layer that surrounds neuronal axons and facilitates the propagation of nerve impulses by increasing the rate of electrical transmission (Jessen 2004). Microglia are brain mononuclear phagocytes that act as the primary immune cells of the brain. Microglia constantly survey their environment and are able to recognize a variety of stimuli, including foreign microbial invaders, toxins, and injury (Bisht et al. 2016; Lull and Block 2010). Following interaction with harmful pathogens or noxious stimuli, microglia become activated, which results in the upregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins, the secretion of signaling molecules and cytotoxins, as well as increased phagocytic activity in attempts to rid the affected area of the damage-causing agents and cellular debris (Bisht et al. 2016; Marsh et al. 2016).

Studies have demonstrated that cardiolipin can be found within neurons, as well as the three main types of glial cells (Chu et al. 2013; Fressinaud et al. 1990; Jacobson et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2011). It has been shown that the content of cardiolipin is approximately two-fold higher in glia compared to neurons, which may contribute to the differences in intracellular signaling molecules and functional activity between these two main types of brain cells (Adibhatla and Hatcher 2007; Kolomiytseva et al. 2010; Kulagina et al. 2004). This variance in cardiolipin content between glia and neurons is partially due to differential expression of a range of proteins affecting the rate of lipid synthesis, degradation, and transfer. In addition, recognition of the extracellular stimuli that affect lipid metabolism could differ between the various cell types, leading to differences in lipid composition (Kolomiytseva et al. 2010; Kulagina et al. 2004).

Role of Cardiolipin in the Cells of the CNS

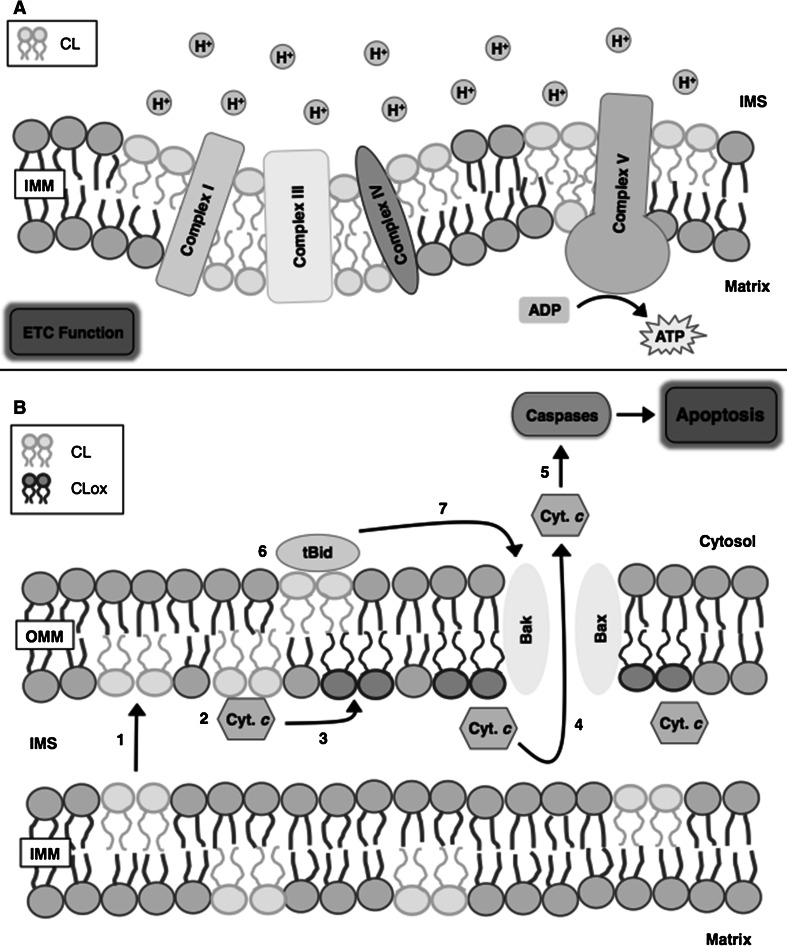

In healthy neurons and glia, cardiolipin is implicated in various biological functions within the mitochondria (Fig. 3). Cardiolipin regulates intracellular and mitochondrial signaling, and maintains the efficiency of the electron transport chain, as well as the fusion and fission of mitochondrial membranes (Mancuso et al. 2009; Petrosillo et al. 2008). Its presence in the inner mitochondrial membrane helps cardiolipin regulate cellular metabolic processes, as it plays a vital role in stabilizing the various respiratory supercomplexes formed by the aggregation of complex I, complex III, and complex IV of the electron transport chain (Acin-Perez et al. 2008; Lapuente-Brun et al. 2013; Pfeiffer et al. 2003). This aggregation not only allows for increased efficiency in the transport of electrons between complexes, which minimizes the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), but also facilitates the transport of protons, thereby producing a strong electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane (Cui et al. 2014; Paradies et al. 2001; Pfeiffer et al. 2003). In addition to being associated with the respiratory supercomplexes, cardiolipin also binds tightly to complex V (ATP synthase) of the electron transport chain, which utilizes the electrochemical gradient to produce ATP (Acehan et al. 2011; Jonckheere et al. 2012; Paradies et al. 2011). Due to its phosphate head-containing structure, cardiolipin is capable of acting as a proton trap that helps maintain the mitochondrial membrane potential, and can supply protons directly to complex V for the synthesis of ATP (Haines and Dencher 2002).

Fig. 3.

The biological functions of cardiolipin in the mitochondria. a Cardiolipin (CL) plays a critical role in maintaining the efficiency of the electron transport chain (ETC). Cardiolipin stabilizes the respiratory supercomplexes, which are formed by the aggregation of complexes I, III, and IV of the electron transport chain. Cardiolipin also binds to and stabilizes complex V (ATP synthase), whereby it is capable of acting as a proton trap that helps maintain mitochondrial membrane potential and directly supplies protons for the synthesis of ATP. b During the initial stages of apoptosis, cardiolipin is (1) redistributed to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), where it interacts with cytochrome c (Cyt. c). (2) This interaction facilitates formation of the cardiolipin/cytochrome c complex, which (3) selectively oxidizes cardiolipin (CLox) and causes the dissociation of the cardiolipin/cytochrome c complex. (4) Dissociation of this complex increases mitochondrial membrane permeability, which allows for the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm. (5) Once in the cytoplasm, cytochrome c interacts with several caspases, which is a critical step in the apoptotic process in cells of the central nervous system (CNS). The activation of caspases, as well as the presence of cardiolipin in the outer mitochondrial membrane, (6) promotes the migration and binding of truncated BH3 interacting-domain death agonist (tBid) protein to the mitochondria and (7) facilitates additional release of cytochrome c, by increasing outer mitochondrial membrane permeability through the oligomerization of Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer (Bak) and Bcl-2-associated X (Bax) proteins. ADP adenosine diphosphate, ATP adenosine triphosphate; IMS intermembrane space, IMM inner mitochondrial membrane

In damaged or diseased neurons, cardiolipin acts as an elimination signal that helps regulate the selective degradation of malfunctioning mitochondria (Chu et al. 2013, 2014). In addition, cardiolipin participates in the programmed death of cells by apoptosis (McMillin and Dowhan 2002; Petrosillo et al. 2008). Dysfunctional mitochondria are known to produce excess levels of ROS, which at high concentrations can damage surrounding cellular membranes and organelles. In order to prevent excessive damage due to high ROS levels, dysfunctional mitochondria are sequestered and selectively degraded through a process called mitophagy. During this process, cardiolipin is relocated from the inner mitochondrial membrane to the outer mitochondrial membrane, a migration that is facilitated by the activity of the mitochondrial isoform of creatine kinase (MtCK) (Garcia Fernandez et al. 2002; Schlattner et al. 2009). This enzyme, which binds to the outer face of the inner mitochondrial membrane mainly through electrostatic interactions with cardiolipin, regulates mitochondrial morphology by facilitating the formation of contact sites between the mitochondrial inner and outer membranes (Maniti et al. 2009; Speer et al. 2005). Furthermore, MtCK has been shown to induce the clustering of cardiolipin at such mitochondrial contact sites, thereby promoting the sequestration of cardiolipin from the inner mitochondrial membrane and allowing for lipid transfer to the outer mitochondrial membrane (Epand et al. 2007; Schlattner et al. 2009). Once redistributed to the outer mitochondrial membrane, cardiolipin acts as a mitochondrial signaling molecule and interacts with proteins involved in the targeted destruction of the mitochondria (Chu et al. 2014; Li et al. 2015; Paradies et al. 2009).

During cellular apoptosis, cardiolipin is similarly redistributed from the inner mitochondrial membrane to the outer mitochondrial membrane (McMillin and Dowhan 2002; Raemy et al. 2016). Multiple types of apoptosis, including the intrinsic and the perforin/granzyme pathways, are largely dependent on the interactions between mitochondrial membrane constituents and cytochrome c, a component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (Cheng et al. 2008; Elmore 2007; Paradies et al. 2009). Relocation of cardiolipin to the outer mitochondrial membrane not only allows it to act as a cytosolic signaling molecule, but also facilitates its interaction with cationic cytochrome c in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (Anthonymuthu et al. 2016; Hong et al. 2012; Schlattner et al. 2009). This interaction leads to the formation of a cardiolipin/cytochrome c complex, which functions as a cardiolipin-specific peroxidase and facilitates the selective oxidation of cardiolipin. Following the oxidation of cardiolipin, the strength of interaction between cardiolipin and cytochrome c decreases causing the dissociation of the cardiolipin/cytochrome c complex, which has been shown to increase the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane (Hong et al. 2012; Kagan et al. 2005; Sparvero et al. 2010; Tyurin et al. 2008). This increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability allows the release of cytochrome c, as well as other pro-apoptotic factors, including second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase/direct inhibitor of apoptosis-binding protein with low pI (Smac/DIABLO), from the mitochondrial intermembrane space to the cytoplasm (Kagan et al. 2005; Petrosillo et al. 2008; Raemy et al. 2016). The mitochondrial release of cytochrome c into the cytoplasm is a critical step of the apoptotic process in both neurons and glia (Camilleri et al. 2013; Jazvinscak Jembrek et al. 2015; Simon et al. 2000; Sparvero et al. 2010; Tyurin et al. 2008). Once in the cytoplasm, cytochrome c is capable of interacting with several different caspases, which results in the initiation of the tightly regulated cell death response (Cheng et al. 2008; van Gurp et al. 2003). BH3 interacting-domain death agonist (Bid) belongs to the Bcl-2 pro-death protein family, and is implicated in regulating apoptotic processes. Bid normally resides in the cytosol in its inactive state; however, once cleaved by caspase 8 in the cytosol, the carboxy-terminus portion of Bid, known as truncated Bid (tBid), is capable of traveling from the cytosol to the mitochondria. Once bound to the mitochondria, tBid increases membrane permeability through the oligomerization of Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer (Bak) and Bcl-2-associated X (Bax) proteins, which induces the release of cytochrome c (Huang and Strasser 2000; Kim et al. 2004). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that this migration and binding of tBid to the mitochondria could be facilitated by cardiolipin (Esposti et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2004). For example, it has been shown that tBid binding is restricted to the cardiolipin-enriched mitochondrial contact sites, and that the binding of tBid is significantly decreased in cardiolipin-deficient membranes, which leads to reduced cytochrome c release (Lutter et al. 2000, 2001). Therefore, it is evident that cardiolipin plays a pivotal role in apoptotic processes within the CNS.

Cardiolipin in CNS Diseases

Due to its role in various metabolic processes in the brain, the modification of cardiolipin, or the molecules it associates with, results in the alteration of mitochondrial structure. This structural change subsequently affects mitochondrial function, as well as the overall viability of cells (Cheng et al. 2008). Modification of the chemical structure of cardiolipin, or even a decrease in the overall levels of cardiolipin, can result in weakened, enlarged, or dysfunctional mitochondria, which are implicated in the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative diseases (Mancuso et al. 2009; Sathappa and Alder 2016), including AD and PD (Ghio et al. 2016; Kiebish et al. 2008), as well as the exacerbation of symptoms following TBI (Cheng et al. 2008; Ji et al. 2012).

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases have become an increasingly significant area of study, as their contribution to global mortality has heightened exponentially during the last several decades. AD is the most common cause of dementia, and currently affects over 46 million people worldwide (Blasko et al. 2004; Prince et al. 2015). This debilitating disorder is characterized by cognitive decline, extensive memory loss and changes in personality and/or behavior (Breedlove and Watson 2013). Two cellular hallmarks, which are hypothesized to contribute to AD pathogenesis, include the deposition of extracellular amyloid β protein (Aβ)-containing plaques, as well as the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (Marsh et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2014). The Aβ plaques are formed due to the dysregulation of beta amyloid precursor protein metabolism, which is accompanied by Aβ overproduction or reduction in Aβ clearance, ultimately leading to the aggregation of Aβ (Fang et al. 2016; Tucker et al. 2000). The neurofibrillary tangles are formed following abnormal phosphorylation of tau protein, which is normally involved in the formation and stabilization of microtubules (Mandelkow and Mandelkow 2012; Wang and Mandelkow 2016). Both of these irregular structures are implicated in the pathophysiology of AD, as they can have toxic effects on surrounding brain cells, including damage to DNA and inhibition of anti-apoptotic mechanisms, ultimately inducing apoptosis and resulting in excessive neuronal death (Marsh et al. 2016; Monteiro-Cardoso et al. 2015; Wang and Mandelkow 2016).

Extensive death of select neuronal populations is also a hallmark of PD, the second most common neurodegenerative disorder following AD (Wood-Kaczmar et al. 2006; Zhou et al. 2008). PD is a debilitating disease caused by the degeneration of neurons in the substantia nigra, as well as the disruption of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the basal ganglia, both of which play a critical role in regulating movement (Cabezas et al. 2014; Nutt and Wooten 2005). Manifestations of PD include several motor-related symptoms such as instability, slowness, and stiffness of movements, tremors at rest as well as abnormal gait (Ghio et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2015). In addition to the extensive death of dopaminergic neurons, other neuropathological mechanisms have been shown to facilitate the development and progression of PD, including the accumulation of α-synuclein protein in PD brains, mitochondrial dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, and the overactivation of glia (Jenner 2003; Wang et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2008). In PD, aggregation of α-synuclein occurs within the soma and dendrites of neurons (Benskey et al. 2016; Wood-Kaczmar et al. 2006). This detrimental amalgamation of protein can occur due to a variety of missense mutations in the α-synuclein gene, which may cause increased intracellular sequestration and aggregation of insoluble α-synuclein (Miller et al. 2004). For a comprehensive review of α-synuclein structure and function, as well as the pathophysiology of associated synucleinopathies see Benskey et al. (2016).

Cardiolipin in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Normal aging brains, as well as those affected by AD and PD, exhibit decreased levels of cardiolipin, as demonstrated by Ruggiero et al. (1992) who showed that non-synaptic mitochondria from the brains of aged rats contain 26% less cardiolipin when compared to mitochondria from the brains of young rats. Additionally, aging brains are associated with elevated production of ROS (Fang et al. 2016; Petrosillo et al. 2008; Zhou et al. 2008). This age-related increase in oxidative stress leads to the peroxidation of mitochondrial membrane constituents, including cardiolipin. Following peroxidation, the structure of cardiolipin is modified in a way that hinders its ability to properly regulate the activity of mitochondrial proteins, including complexes I, III, IV, and V of the electron transport chain (Chicco and Sparagna 2007; Monteiro-Cardoso et al. 2015; Ruggiero et al. 1992; Sen et al. 2006; Tyurin et al. 2008). Petrosillo et al. (2008) confirmed this by showing that brains from aged rats possessed significantly decreased levels of cardiolipin, as well as an increased proportion of peroxidized cardiolipin, which resulted in reduced activity of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain compared to the brains of young rats. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the addition of exogenous cardiolipin, which was extracted and purified from the mitochondria obtained from young rat brains, completely restored the activity of mitochondrial complex I to control level (Petrosillo et al. 2008). Additionally, Perier et al. (2005) utilized a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of PD to show that inhibition of complex I resulted in increased production of ROS and further peroxidation of cardiolipin, demonstrating that a reciprocal relationship may exist between cardiolipin oxidation and impaired complex I activity. Therefore, it is evident that maintaining proper levels of functional cardiolipin is critical for regulating various mitochondrial processes, including the electron transport chain (Fry and Green 1981; Perier et al. 2005).

Within the mitochondrial membranes of PD brains, α-synuclein has been shown to directly interact with and preferentially bind to anionic lipids, such as cardiolipin (Ghio et al. 2016; Kagan et al. 2009). This binding induces a conformational change in α-synuclein, allowing it to adopt α-helical structure, thereby preventing self-association and aggregation of the protein (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). Further investigation of the interaction between cardiolipin and α-synuclein has revealed the ratio of protein to lipid in the mitochondrial membrane as a critical determining factor in the aggregation of α-synuclein (Ghio et al. 2016). Zhu and Fink (2003) demonstrated that a lower protein to lipid ratio resulted in more protein–lipid interactions, which stabilized the α-helical conformation of α-synuclein protein and prevented its aggregation. Therefore, when the levels of functional cardiolipin are significantly decreased, such as in PD brains, the harmful aggregation of α-synuclein protein is exacerbated. The importance of cardiolipin in PD pathogenesis was also demonstrated by Wang et al. (2016), who treated cardiolipin-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans with three different drugs that had been previously shown to rescue the slow growth phenotype of psd1Δ yeast cells expressing human α-synuclein protein. In cardiolipin-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans, these drugs were shown to significantly increase animal survival and rescue dopaminergic neurons (by up to 50%). Therefore, these drugs may compensate for the decreased mitochondrial function resulting from the depletion of vital phospholipids, such as cardiolipin (Wang et al. 2016).

The aforementioned findings, which suggest the interactions between α-synuclein and cardiolipin may be important in PD pathogenesis, are not without controversy, however. Other studies have indicated that α-synuclein binding interferes with the ability of cardiolipin to stabilize and regulate the electron transport chain, as well as the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier, a transport protein located primarily in the inner mitochondrial membrane (Beyer and Nuscher 1996; Fry and Green 1981). Furthermore, the α-helical conformation of α-synuclein has been shown to facilitate production of ROS, increase the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane, and decrease cardiolipin content within the mitochondria, thereby exacerbating the progression of PD (Shen et al. 2014; Stefanovic et al. 2014).

Camilleri et al. (2013) demonstrated that the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane was dependent on the interaction between α-synuclein and mitochondrial membrane constituents, including cardiolipin, rather than the formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT) pore, which typically forms during apoptosis (Crompton 1999). Furthermore, Bayir et al. (2009) demonstrated that α-synuclein was associated with the cardiolipin/cytochrome c complex, which had been generated during apoptosis, thereby forming a triple complex that prevented the cascade of pro-apoptotic signals and exhibited peroxidase activity. However, the same study revealed that the acute beneficial effects caused by the peroxidase activity of the triple complex were followed by an increase in oxidative stress, which may contribute to the chronic neurodegeneration seen in PD brains (Bayir et al. 2009). Considering these contrasting findings, further investigation is required to fully elucidate the significance of the interaction between α-synuclein and cardiolipin in the context of PD pathology.

Due to the role cardiolipin plays in a wide variety of metabolic processes in the brain, its therapeutic potential has recently become a topic of interest. Gobbi et al. (2010) showed that liposomes with embedded cardiolipin readily crossed the BBB from the periphery to the brain. Even though such liposomes have high affinity towards Aβ peptides in AD brains, it is unclear whether this binding could result in the clearance of toxic Aβ peptide aggregates (Gobbi et al. 2010). Orlando et al. (2013) utilized in vitro cell culture techniques to demonstrate that cardiolipin-embedded liposomes were able to act as Aβ ligands without producing toxic effects on endothelial or phagocytic cells. Subsequent studies demonstrated that cardiolipin-containing liposomes carrying nerve growth factor (NGF) were able to cross the BBB and increase the survival of neurons that were previously exposed to harmful Aβ peptides (Kuo and Liu 2014). These discoveries indicate that cardiolipin-containing liposomes could potentially be used as a therapeutic tool for the delivery of various drugs to the brains of patients suffering from AD (Orlando et al. 2013); however, further investigation is required to determine whether these liposomes assist in reducing Aβ aggregation or inducing the clearance of amyloid plaques.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Cardiolipin has not only been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, but has also been shown to play a regulatory role after TBI. TBI occurs following the application of external force that exceeds the protective capacity of the head, and results in physical damage to the brain (Lozano et al. 2015). TBI is one of the leading causes of death and disability in young people, and accounts for approximately one-third of all trauma-related deaths (Heegaard and Biros 2007). Chronic symptoms of TBI include headache, increased levels of stress and anxiety, a change in mood or behavior, as well as impaired motor and cognitive abilities (Bayir et al. 2007; Ghajar 2000; Lozano et al. 2015). These manifestations range from mild to severe, and are caused in part by the cell death that occurs following mechanical damage to neurons, glia, and surrounding blood vessels (McIntosh et al. 1996). Additional pathological features associated with TBI include disruption of the BBB, increased production of ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation, all of which contribute to the extensive brain cell death that results from TBI (Anthonymuthu et al. 2016; Bayir et al. 2007; Heegaard and Biros 2007; Lozano et al. 2015).

Cardiolipin in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Recent studies have implicated cardiolipin in the neuropathological mechanisms associated with TBI. Zhao et al. (2016) demonstrated that following the cellular injury caused by TBI, neurons and microglia released cardiolipin-containing mitochondrial microparticles, which disrupted the BBB. More specifically, this study revealed that the presence of cardiolipin in the mitochondrial microparticles reduced the expression of cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31), a well-defined marker for endothelial cell junctions, and promoted the leakage of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran, a fluorescent probe, through endothelial cell barriers (Zhao et al. 2016). These findings indicate that the release of cardiolipin-containing mitochondrial microparticles following TBI promotes vascular leakage and compromises the integrity of the BBB, thereby amplifying the neurological symptoms associated with TBI.

As with AD and PD, the increased production of ROS following TBI has been shown to result in the selective peroxidation of cardiolipin (Andriessen et al. 2010; Anthonymuthu et al. 2016; Bayir et al. 2007; Ji et al. 2015). Ji et al. (2012) utilized controlled cortical impact (CCI) in rats, an in vivo model of TBI, to demonstrate that following TBI, the proportion of oxidized cardiolipin increased 20-fold, as they were able to identify over 150 different molecular species of oxidized cardiolipin. Furthermore, this study revealed that the administration of XJB-5-131, a targeted electron scavenger that readily crosses the BBB, almost completely prevented the oxidation of cardiolipin, returning the number of oxidized molecular species back to the levels found in control brains (Ji et al. 2012, 2015). These findings, therefore, demonstrate that the prevention of cardiolipin peroxidation could be a therapeutic target for the inhibition of extensive neuronal death, as well as attenuation of the clinical symptoms seen following TBI.

Conclusion

Although the functions of cardiolipin within the mitochondria of cells from peripheral tissues are well defined, less is known regarding the role of cardiolipin within the cells of the CNS, as well as its contribution to the pathogenesis of various brain diseases. The purpose of this review was to summarize the available evidence on the critical role cardiolipin might play in regulating various cellular and molecular processes within the brain, including the efficacy of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, protein aggregation, and apoptotic processes in both neurons and glia. Furthermore, we have outlined the indispensable role of cardiolipin in regulating brain homeostasis (see Table 1), as well as the adverse effects seen when the levels of functional cardiolipin are significantly reduced, such as in aging brains, as well as in the CNS affected by AD, PD, and TBI. Each of these pathologies is associated with increased conversion of cardiolipin to its non-functional oxidized form primarily due to excessive ROS production, a characteristic feature shared between AD, PD, and TBI. The therapeutic use of cardiolipin-containing liposomes is an emerging area of research, which may lead to novel treatment options for neurodegenerative disorders such as AD. Since cardiolipin is also implicated in the pathogenesis of PD, as well as the progression of TBI, further investigation is required to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which cardiolipin contributes to various disease states, as well as to determine its potential as a diagnostic tool or as a marker for monitoring the effectiveness of therapeutic strategies.

Table 1.

The role of cardiolipin in maintaining homeostatic conditions in the CNS

| Cardiolipin is found in neurons, as well as in the three main types of glial cells: astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia |

| Cardiolipin supports mitochondrial functioning by stabilizing various proteins involved in the electron transport chain |

| Cardiolipin contributes to the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane fluidity |

| Cardiolipin can act as a cytosolic signaling molecule that facilitates the selective degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria, as well as the programmed death of brain cells |

| Decreased levels of functional cardiolipin, as well as modification to the structure of cardiolipin, are implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, as well as in exacerbating the symptoms following traumatic brain injury |

Acknowledgements

CP is supported by the University of British Columbia Okanagan Campus fellowships. AK is supported by grants from the Jack Brown and Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the University of British Columbia Okanagan Campus.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Caitlin B. Pointer wrote the manuscript, with editorial comments from Andis Klegeris.

References

- Acehan D, Malhotra A, Xu Y, Ren M, Stokes DL, Schlame M (2011) Cardiolipin affects the supramolecular organization of ATP synthase in mitochondria. Biophys J 100:2184–2192. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acin-Perez R, Fernandez-Silva P, Peleato ML, Perez-Martos A, Enriquez JA (2008) Respiratory active mitochondrial supercomplexes. Mol Cell 32:529–539. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF (2007) Role of lipids in brain injury and diseases. Future Lipidol 2:403–422. doi:10.2217/17460875.2.4.403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriessen TM, Jacobs B, Vos PE (2010) Clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms of focal and diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Cell Mol Med 14:2381–2392. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01164.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthonymuthu TS, Kenny EM, Bayir H (2016) Therapies targeting lipid peroxidation in traumatic brain injury. Brain Res 1640:57–76. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayir H et al (2007) Selective early cardiolipin peroxidation after traumatic brain injury: an oxidative lipidomics analysis. Ann Neurol 62:154–169. doi:10.1002/ana.21168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayir H et al (2009) Peroxidase mechanism of lipid-dependent cross-linking of synuclein with cytochrome c: protection against apoptosis versus delayed oxidative stress in Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem 284:15951–15969. doi:10.1074/jbc.M900418200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benskey MJ, Perez RG, Manfredsson FP (2016) The contribution of alpha synuclein to neuronal survival and function: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 137:331–359. doi:10.1111/jnc.13570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K, Nuscher B (1996) Specific cardiolipin binding interferes with labeling of sulfhydryl residues in the adenosine diphosphate/adenosine triphosphate carrier protein from beef heart mitochondria. Biochemistry 35:15784–15790. doi:10.1021/bi9610055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht K et al (2016) Dark microglia: a new phenotype predominantly associated with pathological states. Glia 64:826–839. doi:10.1002/glia.22966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasko I, Stampfer-Kountchev M, Robatscher P, Veerhuis R, Eikelenboom P, Grubeck-Loebenstein B (2004) How chronic inflammation can affect the brain and support the development of Alzheimer’s disease in old age: the role of microglia and astrocytes. Aging Cell 3:169–176. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove SM, Watson NV (2013) Biological psychology: an introduction to behavioral, cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Sinauer Associates Incorporated, Sunderland [Google Scholar]

- Bussell R Jr., Eliezer D (2003) A structural and functional role for 11-mer repeats in alpha-synuclein and other exchangeable lipid binding proteins. J Mol Biol 329:763–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas R et al (2014) Astrocytic modulation of blood brain barrier: perspectives on Parkinson’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci 8:211. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri A et al (2013) Mitochondrial membrane permeabilisation by amyloid aggregates and protection by polyphenols. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828:2532–2543. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H et al (2008) Shotgun lipidomics reveals the temporally dependent, highly diversified cardiolipin profile in the mammalian brain: temporally coordinated postnatal diversification of cardiolipin molecular species with neuronal remodeling. Biochemistry 47:5869–5880. doi:10.1021/bi7023282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicco AJ, Sparagna GC (2007) Role of cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292:C33–C44. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00243.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT et al (2013) Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nat Cell Biol 15:1197–1205. doi:10.1038/ncb2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Bayir H, Kagan VE (2014) LC3 binds externalized cardiolipin on injured mitochondria to signal mitophagy in neurons: implications for Parkinson disease. Autophagy 10:376–378. doi:10.4161/auto.27191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M (1999) The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J 34:233–249 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui TZ, Conte A, Fox JL, Zara V, Winge DR (2014) Modulation of the respiratory supercomplexes in yeast: enhanced formation of cytochrome oxidase increases the stability and abundance of respiratory supercomplexes. J Biol Chem 289:6133–6141. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.523688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, Mucke L (1993) Molecular profile of reactive astrocytes–implications for their role in neurologic disease. Neuroscience 54:15–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S (2007) Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 35:495–516. doi:10.1080/01926230701320337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RF, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Epand RM (2007) Cardiolipin clusters and membrane domain formation induced by mitochondrial proteins. J Mol Biol 365:968–980. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposti MD, Cristea IM, Gaskell SJ, Nakao Y, Dive C (2003) Proapoptotic Bid binds to monolysocardiolipin, a new molecular connection between mitochondrial membranes and cell death. Cell Death Differ 10:1300–1309. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang D et al (2016) Increased electron paramagnetic resonance signal correlates with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse brain. J Alzheimers Dis 51:571–580. doi:10.3233/JAD-150917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fressinaud C, Vallat JM, Rigaud M, Cassagne C, Labourdette G, Sarlieve LL (1990) Investigation of myelination in vitro: polar lipid content and fatty acid composition of myelinating oligodendrocytes in rat oligodendrocyte cultures. Neurochem Int 16:27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry M, Green DE (1981) Cardiolipin requirement for electron transfer in complex I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. J Biol Chem 256:1874–1880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Fernandez M et al (2002) Early changes in intramitochondrial cardiolipin distribution during apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ 13:449–455 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspard GJ, McMaster CR (2015) Cardiolipin metabolism and its causal role in the etiology of the inherited cardiomyopathy Barth syndrome. Chem Phys Lipids 193:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghajar J (2000) Traumatic brain injury. Lancet 356:923–929. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02689-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghio S, Kamp F, Cauchi R, Giese A, Vassallo N (2016) Interaction of alpha-synuclein with biomembranes in Parkinson’s disease-role of cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res 61:73–82. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi M et al (2010) Lipid-based nanoparticles with high binding affinity for amyloid-beta1-42 peptide. Biomaterials 31:6519–6529. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines TH, Dencher NA (2002) Cardiolipin: a proton trap for oxidative phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 528:35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heegaard W, Biros M (2007) Traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am 25:655–678. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Muenzner J, Grimm SK, Pletneva EV (2012) Origin of the conformational heterogeneity of cardiolipin-bound cytochrome c. J Am Chem Soc 134:18713–18723. doi:10.1021/ja307426k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang HG, Ye JM, Shi Y (2015) Cardiolipin remodeling by TAZ/tafazzin is selectively required for the initiation of mitophagy. Autophagy 11:643–652. doi:10.1080/15548627.2015.1023984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DC, Strasser A (2000) BH3-only proteins-essential initiators of apoptotic cell death. Cell 103:839–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikon N, Su B, Hsu FF, Forte TM, Ryan RO (2015) Exogenous cardiolipin localizes to mitochondria and prevents TAZ knockdown-induced apoptosis in myeloid progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 464:580–585. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J, Duchen MR, Heales SJ (2002) Intracellular distribution of the fluorescent dye nonyl acridine orange responds to the mitochondrial membrane potential: implications for assays of cardiolipin and mitochondrial mass. J Neurochem 82:224–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazvinscak Jembrek M, Hof PR, Simic G (2015) Ceramides in Alzheimer’s disease: key mediators of neuronal apoptosis induced by oxidative stress and abeta accumulation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015:346783. doi:10.1155/2015/346783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P (2003) Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 53(Suppl. 3):S26–S36. doi:10.1002/ana.10483(discussion S36–S38) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR (2004) Glial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36:1861–1867. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J et al (2012) Lipidomics identifies cardiolipin oxidation as a mitochondrial target for redox therapy of brain injury. Nat Neurosci 15:1407–1413. doi:10.1038/nn.3195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J et al (2015) Deciphering of mitochondrial cardiolipin oxidative signaling in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35:319–328. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonckheere AI, Smeitink JA, Rodenburg RJ (2012) Mitochondrial ATP synthase: architecture, function and pathology. J Inherit Metab Dis 35:211–225. doi:10.1007/s10545-011-9382-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan VE et al (2005) Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipin oxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat Chem Biol 1:223–232. doi:10.1038/nchembio727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan VE et al (2009) Cytochrome c/cardiolipin relations in mitochondria: a kiss of death. Free Radic Biol Med 46:1439–1453. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Verkhratsky A (2008) Neuroglia: the 150 years after. Trends Neurosci 31:653–659. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiebish MA et al (2008) Lipidomic analysis and electron transport chain activities in C57BL/6 J mouse brain mitochondria. J Neurochem 106:299–312. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05383.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiebish MA, Han X, Cheng H, Seyfried TN (2009) In vitro growth environment produces lipidomic and electron transport chain abnormalities in mitochondria from non-tumorigenic astrocytes and brain tumours. ASN Neuro. doi:10.1042/AN20090011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH et al (2004) Bid-cardiolipin interaction at mitochondrial contact site contributes to mitochondrial cristae reorganization and cytochrome c release. Mol Biol Cell 15:3061–3072. doi:10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomiytseva IK, Markevich LN, Ignat’ev DA, Bykova OV (2010) Lipids of nuclear fractions from neurons and glia of rat neocortex under conditions of artificial hypobiosis. Biochemistry 75:1132–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulagina TP, Shevchenko NA, Arkhipov VI (2004) Influence of seizures on lipids of homogenate and neuronal and glial nuclei of rat neocortex. Biochemistry 69:1143–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YC, Liu YC (2014) Cardiolipin-incorporated liposomes with surface CRM197 for enhancing neuronal survival against neurotoxicity. Int J Pharm 473:334–344. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JC, Walsh JM, Dennis SC, Clark JB (1977) Synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria from rat brain: isolation and characterization. J Neurochem 28:625–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuente-Brun E et al (2013) Supercomplex assembly determines electron flux in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Science 340:1567–1570. doi:10.1126/science.1230381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XX, Tsoi B, Li YF, Kurihara H, He RR (2015) Cardiolipin and its different properties in mitophagy and apoptosis. J Histochem Cytochem 63:301–311. doi:10.1369/0022155415574818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano D, Gonzales-Portillo GS, Acosta S, de la Pena I, Tajiri N, Kaneko Y, Borlongan CV (2015) Neuroinflammatory responses to traumatic brain injury: etiology, clinical consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:97–106. doi:10.2147/NDT.S65815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YW, Claypool SM (2015) Disorders of phospholipid metabolism: an emerging class of mitochondrial disease due to defects in nuclear genes. Front Genet 6:3. doi:10.3389/fgene.2015.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YW et al (2016) Defining functional classes of Barth syndrome mutation in humans. Hum Mol Genet 25:1754–1770. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddw046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lull ME, Block ML (2010) Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 7:354–365. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Fang M, Luo X, Nishijima M, Xie X, Wang X (2000) Cardiolipin provides specificity for targeting of tBid to mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol 2:754–761. doi:10.1038/35036395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Perkins GA, Wang X (2001) The pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member tBid localizes to mitochondrial contact sites. BMC Cell Biol 2:22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso DJ et al (2009) Genetic ablation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2gamma leads to alterations in hippocampal cardiolipin content and molecular species distribution, mitochondrial degeneration, autophagy, and cognitive dysfunction. J Biol Chem 284:35632–35644. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.055194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (2012) Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a006247. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniti O, Lecompte MF, Marcillat O, Desbat B, Buchet R, Vial C, Granjon T (2009) Mitochondrial creatine kinase binding to phospholipid monolayers induces cardiolipin segregation. Biophys J 96:2428–2438. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh SE et al (2016) The adaptive immune system restrains Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis by modulating microglial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:E1316–E1325. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525466113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh TK, Smith DH, Meaney DF, Kotapka MJ, Gennarelli TA, Graham DI (1996) Neuropathological sequelae of traumatic brain injury: relationship to neurochemical and biomechanical mechanisms. Lab Invest 74:315–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillin JB, Dowhan W (2002) Cardiolipin and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1585:97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia EM, Nguyen H, Hatch GM (2014) Mammalian cardiolipin biosynthesis. Chem Phys Lipids 179:11–16. doi:10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K, Kaspar BK (2016) Glia-neuron interactions in neurological diseases: testing non-cell autonomy in a dish. Brain Res. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DW, Hague SM, Clarimon J, Baptista M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Cookson MR, Singleton AB (2004) Alpha-synuclein in blood and brain from familial Parkinson disease with SNCA locus triplication. Neurology 62:1835–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro-Cardoso VF et al (2015) Cardiolipin profile changes are associated to the early synaptic mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 43:1375–1392. doi:10.3233/JAD-141002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M, Ransom B, Goldman SA (2003) New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci 26:523–530. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt JG, Wooten GF (2005) Diagnosis and initial management of Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 353:1021–1027. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp043908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando A et al (2013) Effect of nanoparticles binding beta-amyloid peptide on nitric oxide production by cultured endothelial cells and macrophages. Int J Nanomedicine 8:1335–1347. doi:10.2147/IJN.S40297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM (2009) Role of cardiolipin peroxidation and Ca2 + in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Cell Calcium 45:643–650. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM (2011) Mitochondrial dysfunction in brain aging: role of oxidative stress and cardiolipin. Neurochem Int 58:447–457. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perier C et al (2005) Complex I deficiency primes Bax-dependent neuronal apoptosis through mitochondrial oxidative damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:19126–19131. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508215102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosillo G, Matera M, Casanova G, Ruggiero FM, Paradies G (2008) Mitochondrial dysfunction in rat brain with aging involvement of complex I, reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Neurochem Int 53:126–131. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyta L et al (2016) Reduced cardiolipin content decreases respiratory chain capacities and increases ATP synthesis yield in the human HepaRG cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1857:443–453. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer K, Gohil V, Stuart RA, Hunte C, Brandt U, Greenberg ML, Schagger H (2003) Cardiolipin stabilizes respiratory chain supercomplexes. J Biol Chem 278:52873–52880. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308366200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope S, Land JM, Heales SJ (2008) Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegeneration; cardiolipin a critical target? Biochim Biophys Acta 1777:794–799. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, Wu Y-T, Prina M (2015) World Alzheimer Report 2015. Alzheimer’s Disease International. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2015. Accessed 19 Oct 2016

- Raemy E, Montessuit S, Pierredon S, van Kampen AH, Vaz FM, Martinou JC (2016) Cardiolipin or MTCH2 can serve as tBID receptors during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 23:1165–1174. doi:10.1038/cdd.2015.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NC (1993) Functional binding of cardiolipin to cytochrome c oxidase. J Bioenerg Biomembr 25:153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero FM, Cafagna F, Petruzzella V, Gadaleta MN, Quagliariello E (1992) Lipid composition in synaptic and nonsynaptic mitochondria from rat brains and effect of aging. J Neurochem 59:487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandlers Y, Mercier K, Pathmasiri W, Carlson J, McRitchie S, Sumner S, Vernon HJ (2016) Metabolomics reveals new mechanisms for pathogenesis in Barth syndrome and introduces novel roles for cardiolipin in cellular function. PLoS ONE 11:e0151802. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saric A, Andreau K, Armand AS, Moller IM, Petit PX (2015) Barth syndrome: from mitochondrial dysfunctions associated with aberrant production of reactive oxygen species to pluripotent stem cell studies. Front Genet 6:359. doi:10.3389/fgene.2015.00359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathappa M, Alder NN (2016) The ionization properties of cardiolipin and its variants in model bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1858:1362–1372. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlame M (2013) Cardiolipin remodeling and the function of tafazzin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1831:582–588. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlame M, Rua D, Greenberg ML (2000) The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res 39:257–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlattner U et al (2009) Mitochondrial kinases and their molecular interaction with cardiolipin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788:2032–2047. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen T, Sen N, Tripathi G, Chatterjee U, Chakrabarti S (2006) Lipid peroxidation associated cardiolipin loss and membrane depolarization in rat brain mitochondria. Neurochem Int 49:20–27. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J et al (2014) Alpha-synuclein amino terminus regulates mitochondrial membrane permeability. Brain Res 1591:14–26. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F (2000) Role of reactive oxygen species in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 5:415–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparvero LJ, Amoscato AA, Kochanek PM, Pitt BR, Kagan VE, Bayir H (2010) Mass-spectrometry based oxidative lipidomics and lipid imaging: applications in traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem 115:1322–1336. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07055.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer O, Back N, Buerklen T, Brdiczka D, Koretsky A, Wallimann T, Eriksson O (2005) Octameric mitochondrial creatine kinase induces and stabilizes contact sites between the inner and outer membrane. Biochem J 385:445–450. doi:10.1042/BJ20040386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic AN, Stockl MT, Claessens MM, Subramaniam V (2014) Alpha-synuclein oligomers distinctively permeabilize complex model membranes. FEBS J 281:2838–2850. doi:10.1111/febs.12824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WR et al (2016) New targets for monitoring and therapy in Barth syndrome. Genet Med 18:1001–1010. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker HM et al (2000) The plasmin system is induced by and degrades amyloid-beta aggregates. J Neurosci 20:3937–3946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyurin VA et al (2008) Oxidative lipidomics of programmed cell death. Methods Enzymol 442:375–393. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01419-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gurp M, Festjens N, van Loo G, Saelens X, Vandenabeele P (2003) Mitochondrial intermembrane proteins in cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 304:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreken P, Valianpour F, Nijtmans LG, Grivell LA, Plecko B, Wanders RJ, Barth PG (2000) Defective remodeling of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol in Barth syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 279:378–382. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mandelkow E (2016) Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 17:5–21. doi:10.1038/nrn.2015.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhou J (2015) Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease and its potential as therapeutic target. Transl Neurodegener 4:19. doi:10.1186/s40035-015-0042-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S et al (2016) Chemical compensation of mitochondrial phospholipid depletion in yeast and animal models of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 11:e0164465. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whited K, Baile MG, Currier P, Claypool SM (2013) Seven functional classes of Barth syndrome mutation. Hum Mol Genet 22:483–492. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Kaczmar A, Gandhi S, Wood NW (2006) Understanding the molecular causes of Parkinson’s disease. Trends Mol Med 12:521–528. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi H, O’Brien JS (1968) Brain cardiolipin: isolation and fatty acid positions. J Neurochem 15:1383–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DS et al (2014) Defective macroautophagic turnover of brain lipids in the TgCRND8 Alzheimer mouse model: prevention by correcting lysosomal proteolytic deficits. Brain 137:3300–3318. doi:10.1093/brain/awu278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Bell RJ, Kiebish MA, Seyfried TN, Han X, Gross RW, Chuang JH (2011) A mathematical model for the determination of steady-state cardiolipin remodeling mechanisms using lipidomic data. PLoS ONE 6:e21170. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z et al (2016) Cardiolipin-mediated procoagulant activity of mitochondria contributes to traumatic brain injury-associated coagulopathy in mice. Blood 127:2763–2772. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-12-688838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Huang Y, Przedborski S (2008) Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease: a mechanism of pathogenic and therapeutic significance. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1147:93–104. doi:10.1196/annals.1427.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Fink AL (2003) Lipid binding inhibits alpha-synuclein fibril formation. J Biol Chem 278:16873–16877. doi:10.1074/jbc.M210136200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]