Abstract

The effects of primary explosive blast on brain tissue still remain mostly unknown. There are few in vitro models that use real explosives to probe the mechanisms of injury at the cellular level. In this work, 3D aggregates of human brain cells or brain microphysiological system were exposed to military explosives at two different pressures (50 and 100 psi). Results indicate that membrane damage and oxidative stress increased with blast pressure, but cell death remained minimal.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10571-017-0463-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Primary blast, Traumatic brain injury, In vitro model, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Minibrain, Explosives

Introduction

Traumatic brain injuries from blast represent a major source of disability and death for military combat personnel. The mechanisms of such injuries are still poorly understood, and often detection with instruments commonly used to study the brain such as MRI is not possible. Thus doctors frequently rely on self-reported symptoms for diagnosis. We have recently developed an in vitro system which uses military explosives in a controlled environment to study the effects of blast waves on brain cells (Zander et al. 2015, 2016a, b). In these experiments, 2D models of dissociated primary neurons, glia, and cell lines were evaluated. Increased membrane damage and oxidative stress, among others, indicated the cells were in a stressed state following blast. These changes may be responsible for the progression of cellular injury and neurodegeneration seen following blast traumatic brain injury. But 2D models are not very realistic as cellular morphology is constrained, which limits complex synaptic interactions (Hogberg et al. 2013). 3D models, in contrast, allow the neurons and astrocytes to maintain a more natural shape and synaptic connections with neighboring cells. Complex 3D models containing the many different cell types of the brain including neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes are critical to replicate the function and structural design of the brain (Pamies et al. 2014). Models using human cells further increase the usefulness of the model.

Our lab has developed a human 3D brain microphysiological system (Pamies et al. 2016). In this work, we have examined the effects of primary blast on human 3D aggregates of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) at two different pressures (50 and 100 psi) to simulate explosive blast-induced TBI conditions.

Materials and Methods

See Supporting information.

Results and Discussion

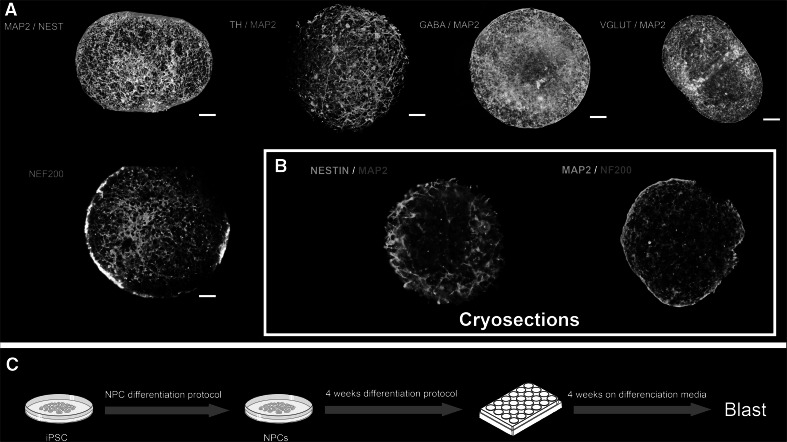

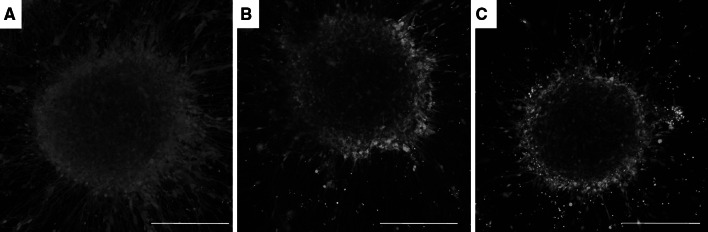

The 3D BMPS model has been already described (Pamies et al. 2016). BMPS has been able to generate different types of neurons (Fig. 1a). As well controlling the size by gyratory shanking, necrosis, normally associated with microphysiological systems bigger than 450 μm, can be avoided in the middle (Fig. 1b). Cell death of 2D or monolayer cultures of cells exposed to blast has been found to be surprisingly low, even at high pressures (Zander et al. 2015, 2016a, b; Arun et al. 2011, Effgen et al. 2014). It was expected that 3D cultures would be more susceptible to injury from the blast wave, resulting in higher cell death rates, since the cultures are not firmly fixed to the culture substrate. But in fact, cell viability rates remained at ca. 90% even after exposure to a 100 psi blast (Fig. 2). Most of the dead cells were observed outside of the aggregates, which may have died sometime during the 8 weeks of culturing to form the aggregate (also observed in controls). It is possible that the live dead stain did not penetrate well inside the aggregate, but MTS viability assay results showed no significant difference from controls of blast-exposed cells (sham 1.47 ± 0.25; 50 psi 1.20 ± 0.41; 100 psi 1.35 ± 0.26, n = 4).

Fig. 1.

a Representative images of immunocytochemistry with fluorescent microscopy for different combinations of specific neuronal markers (MAP2, NF200, TH, GABA, and VGLUT) and immature neurons (nestin) after 8 weeks. b Immunocytochemistry of cry-sectioned 8-week BMPS. c Diagram of cell culture protocol for the blast experiment (Color figure online)

Fig. 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of human 3D aggregates with live/dead stain. a Sham, b 50 psi explosive blast exposure, c 100 psi explosive blast exposure. Green denotes live cells and red denotes dead cells. Scale bar denotes 200 µm (Color figure online)

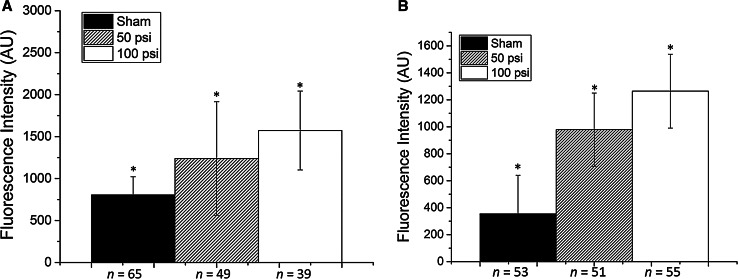

The formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause harmful effects through production of peroxides and free radicals which damage cellular components such as DNA, protein, and lipids, was observed for the blast-injured aggregates (Fig. 3a). The amount of ROS species increased significantly with blast peak pressure. CSLM images of the aggregates are in the supporting information (S2).

Fig. 3.

a Reactive oxygen species changes as a function of ROS indicator uptake of human 3D aggregates 24 h after exposure to explosive blast (50–100 psi), b intracellular sodium measured by CoroNa Green indicator of human 3D aggregates exposed to explosive blast (50–100 psi). *p < 0.05

Membrane permeability changes are commonly observed after blast insults. These changes can lead to a large influx of ions, disrupting ion homeostasis and eventually causing cytoskeletal damage. To access changes in intracellular ionic concentrations, intracellular sodium, and calcium were probed via CoroNa Green and Fluo-4 indicators as described in the Methods section. Figure 3b shows the results for the intracellular sodium imaging of the aggregates. Intracellular sodium was significantly higher for the blast-injured samples and further increased with peak pressure. CSLM images of the aggregates are in the supporting information (S3). Significant increases in intracellular calcium were observed between the sham/50 psi blast and the 100 psi blast (sham 631.9 ± 205, n = 40; 50 psi 356.3 ± 109, n = 29; 100 psi 767.8 ± 241, n = 54). The lack of increase compared to the sham with the lower pressure blast may be due in part to the minimal amount of strain experienced by the cells. Ravin et al. found changes in calcium only following blast in the presence of shear (Ravin et al. 2012). The effect of shear stress was expected to play a greater role in the indicators of damage for the 3D model compared to 2D cultures, but this was not observed in our model. We attribute this to the minimal movement of air or blast wind in our model due to the small size of our explosive and open-air blast design of the experiment. Most in vitro experiments are conducted in shock tube systems, which are composed on compressed gas in an enclosed environment, leading to a significant amount of air movement within the tube. This can lead to the likely greater effect of shear in the 3D versus 2D cell culture models.

Conclusions

In this work, we report changes at the cellular level of human brain tissue aggregates due to explosive shock wave exposure. Significant changes in intracellular sodium and reactive oxygen species were observed, and increased with peak pressure. These changes, which may indicate activation of damage pathways, appear to be transient in nature as cell death was minimal. This has been reported in other studies, but for the first time has been demonstrated in human cells. We believe our work using a human 3D tissue model will improve our understanding of the mechanisms of blast injury in humans, and aid in evaluating the usefulness of other non-human models. Time-course studies with near real-time and later time points after injury would appreciably aid in our understanding of the underlying mechanisms. This knowledge will contribute to better treatment of traumatic brain injuries, and in the design of enhanced protective equipment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Richard Benjamin for his assistance during the blast testing.

References

- Arun P, Spadaro J, John J, Gharavi RB, Bentley TB, Nambiar MP (2011) Studies on blast traumatic brain injury using in vitro model with shock tube. NeuroReport 22:379–384. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e328346b138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effgen GB, Vogel EW, Lynch KA, Lobel A, Hue CD, Meaney DF, Bass CR, Morrison B (2014) Isolated primary blast alters neuronal function with minimal cell death in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurotrauma 31:1202–1210. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogberg HT, Bressler J, Christian KM, Harris G, Makri G, O’Driscoll C, Pamies D, Smirnova L, Wen Z, Hartung T (2013) Toward a 3D model of human brain development for studying gene/environment interactions. Stem Cell Res 4(Suppl 1):S4. doi:10.1186/scrt365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamies D, Hartung T, Hogberg HT (2014) Biological and medical applications of a brain-on-a-chip. Exp Biol Med 239:1096–1107. doi:10.1177/1535370214537738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamies D, Barreras P, Block K, Makri G, Kumar A, Wiersma D, Smirnova L, Zhang C, Bressler J, Christian KM, Harris G, Ming GL, Berlinicke CJ, Kyro K, Song H, Pardo CA, Hartung T, Hogberg HT (2016) A human brain microphysiological system derived from induced pluripotent stem cells to study neurological diseases and toxicity. ALTEX. doi:10.14573/altex.1609122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravin R, Blank PS, Steinkamp A, Rappaport SM, Ravin N, Bezrukov L, Guerrero-Cazares H, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Bezrukov SM, Zimmerberg J (2012) Shear forces during blast, not abrupt changes in pressure alone, generate calcium activity in human brain cells. PLoS ONE 7:e39421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander NE, Piehler T, Boggs M, Banton R, Benjamin R (2015) In vitro studies of primary explosive blast loading on neurons. J Neuroscience Res 9:1353–1363. doi:10.1002/jnr.23594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander NE, Piehler T, Banton R, Boggs M (2016a) The effect of explosive blast loading on human neuroblastoma cells. Anal Biochem 504:4–6. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander NE, Piehler T, Banton R, Benjamin R (2016b) Effects of repetitive low pressure explosive blast on primary neurons and mixed cultures. J Neuroscience Res 94:827–836. doi:10.1002/jnr.23786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.