Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic immune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system that results in destruction of the myelin sheath wrapped around the axons and eventual axon degeneration. The disease is pathologically heterogeneous; however, perhaps its most frustrating aspect is the lack of efficient regenerative response for remyelination. Current treatment strategies are based on anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory medications that have the potential to reduce the numbers of newly evolving lesions. However, therapies are still required that can repair already damaged myelin for which current treatments are not effective. A prerequisite for the development of such new treatments is understanding the reasons for insufficient endogenous repair. This review briefly summarizes the currently suggested causes of remyelination failure in MS and possible solutions.

Keywords: Demyelination, Multiple sclerosis, Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, Myelin repair, Remyelination failure

Introduction

In healthy central nervous system (CNS), myelin allows transmission of impulses via saltatory conduction, in a quick and energy-efficient manner. Myelin also provides physical protection and metabolic support for axons. Most of severe neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS) are associated with the pathological damage or loss of myelin sheaths, a process called demyelination. The mammalian CNS has a remarkable ability for repair and regenerate damaged myelin. This process, which is called remyelination, is a default spontaneous or intrinsic process by which new myelin sheaths are generated around demyelinated axons in the adult CNS, reinstating the saltatory conduction and resolving functional deficits (Shen et al. 2008).

MS is the most common demyelinating disorder of the CNS. The pathological hallmarks of MS are inflammation, breakdown of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), demyelination, remyelination, multifocal lesions, and axonal degeneration. In some MS patients, remyelination occurs successfully early in the disease; however, for the majority of patients, this recovery process gradually fails while demyelination continues. This may lead to subsequent degeneration of axons and eventually loss of neurons. Neuronal loss might underlie the clinical disability observed in patients following chronic demyelination, highlighting the need for treatments that promote both remyelination and neuronal survival. Current treatments for MS are mainly immunomodulatory or anti-inflammatory drugs, which act primarily by modulating or suppressing the immune system and inflammation. However, although they can decelerate the demyelinating course and reduce clinical deterioration, approaches that promote endogenous remyelination for already established demyelinated lesions are still lacking.

Remyelination is carried out by an endogenous population of adult oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs). OPCs are widespread throughout the CNS, encompassing approximately 3–4% of cells in the gray matter and 7–8% in white matter (Horner et al. 2000; Dawson et al. 2003). Moreover, adult neural precursor cells from the subventricular zone contribute significantly to oligodendrocyte regeneration and remyelination (Xing et al. 2014; Mozafari et al. 2010,2011). Unlike neurons, which have limited capacity to regenerate after CNS injury, adult OPCs have significant ability to proliferate and generate mature oligodendrocytes, capable of remyelinating the injured axons (Moyon et al. 2015). Despite this regenerative ability of these cells, still the question remains: why do many axons remain demyelinated in the CNS of MS patients? Understanding why endogenous remyelination often fails in MS is crucial to the development of effective remyelination therapies.

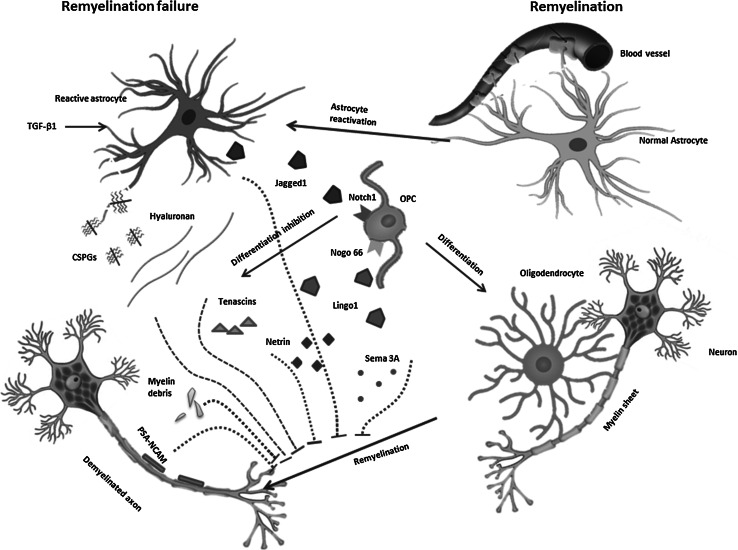

For remyelination to occur, OPCs must proliferate and migrate to the lesion then differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes. Mature oligodendrocytes extend processes toward axons, make contact to them and enwrap them with concentric layers of myelin membrane, and finally compact these layers into functional myelin (Miron et al. 2011). In theory, remyelination can be blocked at any point in the remyelination process including proliferation of OPCs, their recruitment towards the lesion, their differentiation into oligodendrocytes, and attachment of mature oligodendrocytes to the axons. Recently, several laboratories have begun to explore the molecular pathology that limits remyelination in hopes of development approaches for therapeutically enhancing remyelination in MS patients. In the following, we discuss some postulates for failure of remyelination in MS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Transforming growth factor-β 1 (TGF-β1) secreted by resident glial cells stimulates astrocytes in MS lesions to re-express the Notch ligand Jagged 1. Contact-mediated activation Notch signaling by ligand Jagged 1 inhibits OPC differentiation. Lingo-1, expressed by neurons and oligodendrocytes, is up-regulated in MS lesions, leading to OPC maturation inhibition and ultimate remyelination failure. The compounds of extracellular matrix including CSPGs, Hyaluronan, Tenascin C and R, produced through leakage from the damaged vasculature of BBB and secreted from reactive glial cells are often inhibitory to oligodendrocyte process extension and remyelination of axons. Deregulation of OPC guidance factors including semaphorins, netrins, and various chemokines are also contributed to remyelination failure. Production of PSA-NCAM by damaged axons is another inhibitor of remyelination through impairment of oligodendrocyte attachment to axons. Myelin debris remained following myelin sheet unravels and disperses from axons which are another inhibitory block for remyelination

Intracellular Pathways that Block Remyelination

Notch1 Pathway

Expressed by oligodendrocytes, Notch1 receptor is a well-known regulator of OPC maturation in the developing CNS (Wang et al. 1998). Notch1 interacts with membrane-bound ligands, Jagged1 and Delta, activating the canonical pathway that increases the downstream effecter, Hes5. In turn, Hes5 inhibits OPC differentiation. When cultured human OPCs were exposed to Jagged1, the OPCs failed to mature (John et al. 2002; Mi et al. 2009). Within and around active MS plaques lacking remyelination, Jagged1 was found to be expressed by reactive astrocytes, via stimulation with transforming growth factor-β1, (TGF- β1) an up-regulated cytokine in MS (John et al. 2002; Mi et al. 2009). Thus, re-expression of Jagged1 has been proposed to hamper remyelination in MS via activation of Notch1 pathway and inhibition of OPCs differentiation (John et al. 2002; Mi et al. 2009). However, the results of available in vivo studies provide conflicting evidence regarding a role for Notch1-Jagged1 in failure of adult CNS remyelination. First, in experimental models of demyelination, alterations of Jagged1 and Notch1 expression were not in agreement with what was found for MS lesions (Stidworthy et al. 2004). The experiment showed that Jagged1 and Notch1 were expressed in OPCs from experimental ethidium bromide-induced demyelination model, despite complete remyelination (Stidworthy et al. 2004), indicating that remyelination may occur in the presence of active Notch signaling. Similarly in EAE model of MS, Notch1-positive oligodendrocytes were exclusively present in lesions with ongoing remyelination and not found in lesions without signs of remyelination (Seifert et al. 2007). Secondly, conditional ablation of Notch1 in PLP-expressing oligodendrocytes of cuprizone-treated transgenic mice (proteolipid protein (PLP)−creERNotchlox/lox mice) did not produce a marked effect on remyelination, based on G ratio and percent remyelination (Stidworthy et al. 2004). However, one possibility explaining this conflicting result is that PLP+ oligodendrocytes may be too far along in maturation to respond to Jagged1/Notch1 inhibitory signaling in this experiment. In support of this possibility, conditional deletion of Notch1 in oligodendrocytes using Olig1Cre:Notch1, instead promoted precocious oligodendrocyte maturation (Zhang et al. 2009). Remyelination was extensive in these mice as well. Therefore, Notch1 signaling may block oligodendrocyte maturation in earlier stages of differentiation. In addition, an in vitro myelination experiment targeting Notch1 by siRNA confirmed that Notch1 signals inhibit OPCs differentiation and ultimately remyelination following toxin-induced demyelination of the corpus callosum (Mi et al. 2009). Overall, the reports of available animal studies make the role of Notch1 in remyelination of MS lesions complicated, leaving the role of Notch1 signaling on OPC differentiation during remyelination in vivo inconclusive.

LINGO1 Pathway and Nogo Receptor

LINGO-1 is a CNS-specific single transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in neurons and in oligodendrocytes but absent in astrocytes during development (Mi et al. 2004). It belongs to a large family of Leucine-rich-domain Ig-containing proteins involved in neurogenesis, axon guidance, and myelination during normal development (Mi et al. 2004). LINGO-1 associates with the Nogo-66 receptor complex (NgR1 complex) and exerts control over developmental myelination in vitro and in vivo, through a homophilic–hemophilic interaction and a Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA)-mediated mechanism (Mi et al. 2005). Various molecular and genetic tools including loss of function studies using siRNA, blocking antibodies, and null-mutant mice (Mi et al. 2005, 2007, 2009) as well as gain of function studies using lentiviral overexpression and transgenic mice (Lee et al. 2007; Mi et al. 2005) have reported LINGO-1 as a negative regulator of OPC differentiation and myelination. In vitro, experimental attenuation of LINGO-1 resulted in down-regulation of RhoA activity, a small GTPase involved in cytoskeletal dynamics, implicated in oligodendrocyte differentiation (Burridge and Wennerberg 2004). This, in turn, propels the in vitro differentiation of OPCs. Conversely, overexpression of LINGO-1 leads to activation of RhoA and inhibition of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination (Mi et al. 2005). LINGO-1 expression is reported to be up-regulated during CNS injury across diverse animal models and human CNS diseases (Mi et al. 2007; Inoue et al. 2007; Fernandez-Enright et al. 2014). Because impaired remyelination is a pathological hallmark of MS, antagonizing LINGO-1 was supposed to provide therapeutic target for the treatment of this disease. However, recent studies have reported that this approach failed to show significant therapeutic outcomes in MS patients. Still, poor trial design and not optimally developed drug are two possible causes of this failure.

Moreover, major myelin-associated inhibitory factors, NogoA and myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), exhibit their inhibitory effect through binding to NgR1. This receptor is expressed by neurons and other neural cells including neural stem cells, OPCs, astrocytes, Schwann cells, microglia as well as non-neural cells. It is well documented that inhibition of NgR can functionally enhance axonal repair and also lead to repopulation of progenitor cell and increase of myelinogenic potential of oligodendrocytes (Pourabdolhossein et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2010; Steinbach et al. 2011).

Wnt Pathway

Wnt signaling is another well-described developmental pathway implicated in preventing myelination during development and possibly preventing remyelination. This pathway prevents OPCs exit from the cell cycle and arrests their differentiation (Mi et al. 2009). Treatment of cord explants or primary mixed glial cultures with Wnt-conditioned media suppresses oligodendrocyte development. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of GSK3ß, a downstream of Wnt signaling, resulted in inhibition of oligodendrocyte maturation without affecting on OPC numbers (Shimizu et al. 2005).

A whole-genome screening study for transcription factors (TFs) expressed during remyelination, especially those expressed with the oligodendrocyte lineage, revealed specific expression of Tcf4 (also called TCF7L2), a critical intranuclear component of canonical Wnt signaling within remyelinating lesions—but not normal adult white matter (Fancy et al. 2009). Moreover, in a gene microarray analysis, MS lesions have been shown to express multiple Wnt signaling genes, including Wnt2, Wnt7a, β- catenin, Tcf4, and GSK3β, and their expression levels in active plaques were higher than in chronic silent plaques and normal-appearing white matter (Lock et al. 2002). Moreover, a proteomic analysis revealed the same phenomenon showing an up-regulated expression of Wnt signaling-related proteins (including Wnt3a, APC, and β-catenin) in MS lesions; the highest expression being observed in chronic active plaques (Han et al. 2008). Results from a blood RNA profiling study in a large cohort of MS patients also supported consideration of the Wnt pathway as a player in MS pathogenesis (Nickles et al. 2013). An explanation about activation of this pathway in remyelination is that in the initial stages of remyelination, a large number of OPCs are generated for myelin repair. It is necessary that OPCs do not exit cell cycle too early and differentiate before a sufficient numbers of cells have been generated (Casaccia-Bonnefil and Liu 2003). In order to ensure this, it seems probable that inhibitory regulators of differentiation such as Wnt are activated in OPCs. When these cells reached the appropriate number, these inhibitory pathways need to be switched off allowing the cells to then become responsive to inducers of differentiation and completion of remyelination. This model, however, requires very precise timing, whose dysregulation might be involved in differentiation failure. Altogether, these evidences of Wnt pathway activity in human MS lesions suggest that its dysregulation might contribute to inefficient myelin repair in MS patients.

RXR-γ Pathway

Several lines of evidence suggested that RXR-γ signaling might be involved in remyelination. RXR-γ is a nuclear receptor that dimerizes with other receptors, including retinoic acid receptors, thyroid hormone receptors, vitamin D receptors, and peroxisome proliferator activator receptors (PPARs) to modulate cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (Germain et al. 2006). In the healthy mammalian CNS, it is expressed at low levels by all glial cell types (Moreno et al. 2004). However, its expression is increased by activated microglia or macrophages, reactive astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes after CNS myelin injury (Huang et al. 2011b). The results of microarray analysis from demyelinated lesions of rodent brain at different stages of remyelination indicated RXR-γ as a positive regulator of endogenous remyelination (Huang et al. 2011b). OPCs express this receptor, and treatment of OPCs with an RXR-γ antagonist in vitro has led to impaired OPC maturation. In contrast, incubation with a RXR agonist, 9-cis-retinoic acid stimulated OPC differentiation and induction of remyelination in culture. Moreover, focal demyelinating lesions in RXR-γ knockout mice were associated with accumulation of immature OPCs, and treatment of rats with the RXR-γ agonist improves remyelination. In MS, RXR-γ expression increases in the nuclear component of OPCs in active lesion borders but is decreased in chronic inactive lesions, suggesting RXR-γ plays a positive role in remyelination (Huang et al. 2011b).

ECM Compounds as Modulators of Remyelination

A hallmark of CNS injury is the activation and proliferation of local glial cells, including microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Reactive glial cells, in particular astrocytes and microglia, deposit extracellular matrix proteins and increase the production of molecules that are often inhibitory to regeneration, the presses that eventually forms glial scar. In MS patients, ECM composition changes occur in both active and chronic lesions, as well as in the normal-appearing white matter. Aberrant deposition of ECM molecules occurs by leakage from the damaged vasculature and BBB disruption and by altered secretion from reactive glial cells, in particular astrocytes and microglia. The aberrant deposition of ECM molecules then creates a lesion environment that is often inhibitory to oligodendrocyte process extension and remyelination of axons, which in turn leads to increasing neuronal damage as the disease progresses (Wheeler and Fuss 2016; Lau et al. 2013). These are dynamic processes and the level of each ECM molecule changes as lesions progress and recover. The degree of remyelination likely results from the net ratios of supportive and inhibitory ECM molecules (e.g., merosin, CSPGs, tenascins, hyaluronan, fibronectin aggregates) within and around the lesion. In the following, we will discuss briefly the ECM compounds with inhibitory effects on remyelination. ECM is mainly secreted by reactive astrocytes; therefore, the removal of astrocytes may improve remyelination. As glial scars are distributed within the CNS in MS setting, removal of gliosis through surgery-like approaches is not feasible. Recently, engineering of these astrocytes into functional cells, such as neurons or oligodendrocytes has provided a new strategy for cellular regeneration in CNS injuries. Currently transcription factors, small molecules, and microRNAs are administrated as mediators of this cell conversion. For instance, forced expression of Oct4 and miR-302/367 converted the transduced astrocytes into oligodendrocyte lineage cells, in vivo (Dehghan et al. 2016; Ghasemi-Kasman et al. 2016). Moreover, previous work showed direct conversion of astrocytes into neuroblasts by miR-302/367, both in vivo and in vitro (Ghasemi-Kasman et al. 2015).

Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycans (CSPGs)

CSPGs consist of a protein core and a varying numbers of long-sulfated unbranched negatively charged glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains made up of repeating disaccharide units. High levels of CSPGs are present in the glial scars formed after many types of CNS insults including MS lesions (Mohan et al. 2010). After injury, reactive astrocytes and macrophages up-regulate CSPGs expression and OPCs themselves become reactive, change morphologically, and increase expression of CSPGs (Chen et al. 2002; Massey et al. 2008). Thus, oligodendrocytes are exposed to very high levels of CSPGs after CNS damage. Direct exposure of OPCs to CSPGs revealed a significant inhibition of process outgrowth, morphological differentiation as well as OPC migration (Lau et al. 2012; Siebert et al. 2011; Kippert et al. 2009; Siebert and Osterhout 2011). Thus, high levels of GSPGs in MS lesions environment contribute to the remyelination aversive.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma (PTPσ), which is expressed by oligodendrocytes, has been identified as a functional receptor for CSPGs in oligodendrocytes. This receptor appears to be a mediator of the inhibitory effects of CSPG on oligodendrocytes process outgrowth and capacity to remyelinate. Knockdown of PTPσ also reversed the inhibition of process outgrowth on CSPGs (Pendleton et al. 2013). PTPσ activation by CSPGs likely impedes myelination by interfering with oligodendrocytes process extension towards axons, rather than by inhibiting OPCs differentiation directly. Since immature OPCs express low levels of CSPG receptors, they are able to migrate into active lesion areas, despite the high CSPG concentration. As OPCs mature, the levels of PTPσ expression are increased. Thus, differentiating oligodendrocytes, PTPσ negatively, regulate Rho signaling pathway that promotes cytoskeletal rearrangements necessary for process extension and maturation (Pendleton et al. 2013). This is in agreement with the studies that report that CSPG-mediated inhibition of oligodendrocyte process outgrowth acts through Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) and in vitro studies show that inhibition of ROCK can reverse the inhibitory effects of CSPGs on oligodendrocyte process outgrowth and differentiation (Pendleton et al. 2013; Siebert and Osterhout 2011).

Fibronectin and osteopontin are two ECM molecules increased in demyelinating injury (Zhao et al. 2008; Selvaraju et al. 2004; Stoffels et al. 2013). During the process of demyelination these compounds are leaked from the blood circulation or produced by CNS resident cells including astrocytes. Temporal dimeric fibronectin expression is suggested to play an important role in remyelination at earlier stages of MS. However, increased aggregations of fibronectin within chronically demyelinated MS lesions contribute to remyelination failure predominantly via perturbed OPCs differentiation and subsequent impairment of remyelination (Stoffels et al. 2013). Thus strategies to promote remyelination should predominantly interfere with fibronectin aggregation, without preventing fibronectin deposition.

The production of osteopontin is also unregulated in demyelinated areas that undergo spontaneous and complete remyelination (Woodruff and Franklin 1999). The osteopontin indicated to have capacity to induction of proliferation and maturation of oligodendrocyte-derived cell lines and also enhancement of remyelination (Selvaraju et al. 2004). However, studies on osteopontin−/− mice showed that osteopontin plays a major role in governing the efficiency of remyelination (Zhao et al. 2008).

Hyaluronan-TLR2 Pathway

Accumulation of high molecular weight (HMW) hyaluronan (900–1000 kDa), produced by astrocytes, is another factor that has been implicated in the inhibition of OPCs differentiation in chronic MS lesions as well as in experimental demyelination models (Back et al. 2005). Culturing rat oligosphere-derived OPCs in the presence of HMW resulted in a significant reduction in the expression of myelin basic protein (MBP), a marker for mature oligodendrocytes. Furthermore, the addition of HMW hyaluronan to OPC cultures reversibly inhibits progenitor-cell maturation, whereas degrading hyaluronan in astrocyte-OPC co-cultures promotes oligodendrocyte maturation, supporting the notion that astrocyte-derived HMW is able to inhibit the differentiation of OPC (Back et al. 2005). In addition, expression of Toll-like receptor2 (TLR2), a receptor for hyaluronan, by oligodendrocytes was found to be up-regulated in MS lesions. Neutralizing antibodies to TLR2 lead to blockage of the inhibitory effect of HMW hyaluronan on OPC maturation, supporting the role for hyaluronan as a negative regulator for oligodendroglial differentiation via a TLR2 signaling pathway (Back et al. 2005; Sloane et al. 2010).

Tenascins

Besides adding to ECM structural stability, tenascins influence oligodendrocyte survival, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and morphological maturation (Czopka et al. 2009; Kiernan et al. 1996). Tenascin R (Tnr), expressed by oligodendrocytes themselves and by postnatal astrocytes, is necessary for the timely differentiation of oligodendrocytes in vitro. Conversely, Tenascin C (Tnc) expressed by radial glia cells at embryonic and by astrocytes at early postnatal stages exerts a strong inhibitory influence on OPC differentiation (Fuss et al. 1993). However, in contrast to their antagonistic effect on differentiation, both Tnc and Tnr similarly inhibited morphologic maturation by reduction of process elaboration and membrane expansion of OPCs through interfering with the activation of the small GTPase RhoA (Czopka et al. 2009). During the evolution of MS lesions, Tnc and Tnr remodeling occurs. In acute MS lesions, Tnc and Tnr glycoproteins are lost, and the loss extends into the normal-appearing white matter (Gutowski et al. 1999). As lesions become chronic, further reactivation of astrocytes increases the production of Tnc and Tnr, which might lead to the chronic inhibitory situation of glial scar formation.

Contribution of OPC Guidance Factors in Remyelination Failure

Failure of OPC recruitment into areas of demyelination may also arise due to disturbances in the local expression of the OPC migration guidance cues. A number of OPC guidance cues, whether repellant or attractive, have been implicated as regulators of OPC migration in developmental myelination and MS remyelination (Boyd et al. 2013; Tepavcevic et al. 2014). The most important long-range guidance cues include netrins and semaphorins. Chemokines, that are mainly produced by astrocytes, also play important roles in migration and maturation of glial cells.

Semaphorins

Semaphorins, a large family of secreted or transmembrane and glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, originally described as axonal growth cone guidance molecules, are among the most important OPC guidance cues. Two members of Semaphorins, called Semaphorin 3A (sema 3A) and sema 3F, have been shown to play important roles in the regulation of OPC migration (Spassky et al. 2002; Sugimoto et al. 2001). OPCs express Neuropilin 1 (NP1) and NP2, which are sema 3A and sema 3F receptors, respectively. During development, binding of sema 3A receptors to NP1 respells OPCs migration. Conversely, binding of sema 3F to NP2 leads to attraction of these cells (Cohen et al. 2003; Piaton et al. 2011; Spassky et al. 2002).

In adulthood, the mRNA expression of sema 3A and 3F in white matter disappears. However, the results obtained from toxin-induced demyelination model, showed that they are re-expressed and regulate OPC migration in demyelinating lesions. In the case of MS lesions, both Semaphorins are re-expressed as well. However, their expressions differ with regard to the degree of inflammatory activity and type of lesion, with active lesions (more inflammatory with ongoing remyelination) containing higher expression of the chemoattractant sema 3F than sema 3A, and chronic active lesions (less inflammatory and less likely to remyelinate) with higher expression of the chemorepellent sema 3A than sema 3F (Williams et al. 2007). Interestingly, the expression of their receptors is restricted to the cells available in the plaque and periplaque areas and, in contrast, neuropilin-1/2-positive cells seem to be absent in normal-appearing white matter (Syed et al. 2011). It is noteworthy that sema 3A also induces a reversible, dose-dependent inhibition of OPC differentiation. Thus, upregulation of sema 3A potentially prevents OPCs recruited into demyelinated lesions from differentiating into myelin-forming oligodendrocytes, which is in agreement with the findings that the presence of sema 3A in demyelinated lesion is associated with a strong impairment of remyelination (Syed et al. 2011). These findings may, at least partially, explain why most chronic active MS lesions are less likely to remyelinate, whereas majority of active MS lesions are likely to remyelinate.

Netrin-1

Netrin-1 is a secreted protein that directs both axonal extension (Manitt and Kennedy 2002) and OPC migration during CNS development (Spassky et al. 2002). Netrin-1 acts as chemorepellent for OPCs during embryonic development, and its effect is mediated by RhoA/ROCK signaling (Rajasekharan et al. 2010). Upregulation of astrocytic netrin-1 expression has been reported in mouse model of demyelination (Tepavcevic et al. 2014). Recently full-length netrin-1 protein and fragments of netrin-1 were found in chronic MS lesions (Tepavcevic et al. 2014; Bin et al. 2013). Besides, netrin-1 receptors were indicated to be expressed by OPCs in the brains of MS patients, and astrocytes in active and chronic MS lesions are netrin-1 + , whereas this expression is low in the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) and shadow plaques of MS lesions. These data, combined with the function of netrin-1 as a chemorepellent for adult OPCs in vitro, suggested that netrin-1 prevents periplaque OPC recruitment, and thereby would affect myelin repair. However, netrin-1 promotes OPCs differentiation in vitro and increases the acquisition of mature phenotype by oligodendrocytes. The presence of netrin-1 detected in actively demyelinating MS lesions is associated primarily with OPC differentiation and low OPC proliferation. It therefore seems that the timing of netrin-1 expression within areas of demyelination may be an important determinant of myelin repair meaning that early absence of this OPC chemorepellent facilitates OPC recruitment, whereas later expression of netrin-1 may act to switch OPC recruitment to differentiation. Thus, netrin-1 expression prior to OPC recruitment might be detrimental to myelin repair. A possible hypothesis is that during active MS demyelination, netrin-1 stimulates local OPC differentiation and prevents periplaque OPC recruitment (Tepavcevic et al. 2014). Repeated episodes of demyelination exhaust the pool of OPCs in the lesion, leaving only a few quiescent cells, corresponding to either surviving dysfunctional OPCs or recruited OPCs that only arrive at the lesion once the acute inflammatory stimulus has terminated and thus remain undifferentiated.

Chemokine OPC Guidance

Many chemokines play roles in migration and maturation of neural precursor cells during normal development (Stumm et al. 2007; Tsai et al. 2002). Local chemokine released by astrocytes and epithelial cells in MS setting also contribute to the modulation of OPC biology. For instance, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1) -expressing astrocytes (a chemokine that provides a migratory stop signal for OPCs) (Tsai et al. 2002), were detected at high levels around active MS lesions being totally absent in normal samples (Omari et al. 2005). The presence of CXCL1-producing astrocytes has been indicated to be associated with CXCL1 receptor (CXCR2)-expressing oligodendrocytes at these lesions. Signaling through CXCR2, CXCL1 is known to inhibit oligodendrocyte precursor migration (Tsai et al. 2002). In contrast to active lesions, in silent lesions, astrocytes displayed diminished expression of CXCL1. This proposed a functional role for CXCL1 in remyelination failure, potentially by inhibition of OPCs maturation. Supporting evidences were obtained from demyelinated CNS slice cultures, which showed enhanced myelin repair when CXCR2 was blocked with either genetic deletion or neutralizing antibodies.

However, the available reports are contradictory, with some reporting a protective role for CXCR2 during demyelination. In transgenic mice during EAE, overexpression of CXCL1 in astrocytes led to a decrease in clinical severity, a decrease in demyelination, and an increase of remyelination through CXCL1/CXCR2 pathway (Omari et al. 2009). Moreover, systemic injection of a small inhibitor molecule for CXCR2 at the onset of EAE decreased numbers of demyelinated lesions (Liu et al. 2010). It is suggested that the protective and pro-apoptotic roles of CXCR2 with regards to oligodendrocytes may be context-dependent (Hosking et al. 2010). In vivo studies on models of demyelination revealed that expression of CXCL12 by activated astrocytes is crucial for the maturation of OPCs that express CXCR4 during remyelination in adult mice (Patel et al. 2010, 2012). It has been showed inhibition of CXCR4 signaling, either via pharmacologic antagonism with AMD3100 or via in vivo RNA silencing, prevented OPC maturation and remyelination, proposing that CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling is required for OPCs maturation and myelin repair following CNS injury (Patel et al. 2010). However, the function of CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway is disrupted by upregulation of CXCR7 in the context of demyelination. CXCR7 is an alternative scavenger receptor, which works to sequester and degrades CXCL12 (Naumann et al. 2010; Boldajipour et al. 2008) and regulates activation of CXCR4. High level of CXCR7 was showed to regulate CXCL12 expression during demyelination, which leads to decreased expression of CXCL12 and a down-regulation of activated CXCR4 in OPCs. Since CXCR7 regulates CXCL12-CXCR4-mediated CNS myelin repair, it may, therefore, serve as a therapeutic target to promote OPC differentiation and remyelination in the adult CNS.

PSA-NCAM a Mediator of Myelin Attachment to Axons

PSA‐NCAM, a glycoprotein localized in the plasma membrane of neural and glial cells, acts as an inhibitor of myelination, presumably by preventing myelin‐forming cells from attaching to the axon. It also appears to exert a considerable inhibitory effect on OPCs differentiation (Charles et al. 2002). Disappearance of PSA‐NCAM from the axonal surface during development is coincident with the onset of myelination in human embryonic brain (Fewou et al. 2007). Blocking down-regulation of PSA in oligodendrocytes, in transgenic mice, that exhibit expression of the polysialyltransferase under the control of the PLP promoter led to a reduction in myelin content in the forebrains, both during the period of active myelination and in adult brain (Fewou et al. 2007). Furthermore, antibody‐mediated internalization PSA or removal of PSA sites by treatment with endoneuraminidase N, an enzyme that specifically hydrolyzes PSA, could promote the formation of myelinating internodes in mouse neuron–oligodendrocyte co-cultures (Charles et al. 2000). PSA-NCAM is normally absent from the adult brain but is abundantly re-expressed on demyelinated axons in chronic inactive MS lesions (Charles et al. 2002). In contrast, axons in acute lesions characterized by inflammatory infiltrates and lesions that underwent remyelination did not show evidence of PSA-NCAM expression. It acts as a negative regulator of myelination, presumably by preventing myelin-forming cells from attaching to the axon and blocking the OPCs differentiation (46). However, in addition to its effect on myelination, PSA-NCAM expression in early migratory progenitors is important for migration and recruitment of OPC to the lesion (Franceschini et al. 2004). The second role, therefore, may complicate the design of strategies aimed at removing barrier PSA to promote myelin repair.

Myelin Debris as Inhibitor of Remyelination

The process of primary demyelination generates vast amounts of myelin debris as the myelin sheet unravels and disperses from axons. Myelin removal is a critical step in the remyelination process. Cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system, including monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) and microglia, are actively implicated in the clearance of myelin debris (Napoli and Neumann 2010). Several lines of evidence reveal the importance of phagocytic removal of myelin debris for efficient remyelination. First, the more rapid remyelination that occurs in young animals is suggested to be associated with efficient removal of myelin debris in contrast to slow remyelination in adult animals as a result of impaired clearance of myelin due delayed activation and recruitment of phagocytic macrophages (Zhao et al. 2006). Second supportive evidence was obtained by impaired differentiation of cultured OPCs plated onto a CNS myelin substrate. (Robinson and Miller 1999). Third, injection of myelin debris in experimentally induced demyelinated animals severely impaired remyelination accompanied with an impairment of OPC differentiation, even after normal recruitment of these precursor cells and macrophages (Kotter et al. 2006). Myelin debris release inhibitory peptides which interact with Nogo-66 receptor and function through LONGO-1 to inhibit remyelination. Two main signaling pathways including Fyn-Rho-ROCK and PKC have been identified as being critical mediators of myelin-mediated inhibition (Baer et al. 2009). However, the concept of inhibitory effects of un-cleared myelin debris on remyelination has been derived exclusively from experimental studies and their role in MS remyelination failure is yet to be demonstrated.

Remyelination Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis

Given the large numbers of OPCs present in adult brain tissue, there are several potential strategies to enhance the remyelination capacity of endogenous OPCs, such as manipulating intrinsic signaling pathways that govern oligodendrocyte biology to override the inhibition of remyelination or altering the lesion environment to be more permissive of OPC differentiation, migration, and remyelination. In recent decades, small molecules, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and monoclonal antibodies that can target specific components of the signaling pathways that underlie myelination have been developed and tested. Among the targeted pathways with impact on OPCs maturation and myelination are Notch (Zhang et al. 2009), Wnt (Fancy et al. 2009), Akt (a serine/threonine kinase), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Feigenson et al. 2009; Narayanan et al. 2009), extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Ishii et al. 2012; Fyffe-Maricich et al. 2011), RXR/PPAR (Huang et al. 2011a), ISR (Cunnea et al. 2011; Mhaille et al. 2008), basic fibroblast growth factor (Dehghan et al. 2012), and LINGO-1 (Mi et al. 2007, 2009; Sun et al. 2015).

For instance, targeting LINGO-1 has been successful in reducing axonal damage, promoting remyelination, and restoring function after EAE (Mi et al. 2007, 2009; Sun et al. 2015). Moreover, blocking LINGO-1 with its antagonist antibody (mAb3B5) has been shown to enhance remyelination and recovery of axonal function in the rat lysolecithin-induced focal spinal cord demyelination model. In our previous study, we indicated that targeting NgR by siRNA leads to a significant remyelination and functional recovery of a focal model of demyelination in the mouse optic nerve. Our findings also showed that NgR inhibition also significantly increased the number of Olig2+ cells recruited in the lesion site and enhanced the numbers of third ventricle progenitor cells produced following chiasm demyelination (Pourabdolhossein et al. 2014). These findings shed a light on potential treatment for remyelination. To date, four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials to evaluate safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic profile, and efficacy of an anti-LINGO-1 monoclonal antibody called BIIB033 have been completed (ClinicalTrial.gov identifiers: NCT01864148, NCT01721161, NCT01052506, NCT01244139), and some results have been published (Tran et al. 2014). However, there is a tremendous amount of cross-talk among signaling pathways and manipulation of one pathway often induces alterations in another pathway, making these approaches complicating.

As RXRγ is highly expressed in acute and remyelinating lesions, its agonists have been explored in the pathophysiologic context of MS. The RXR-γ agonist has showed to improve remyelination in both cell culture system and in EAE animal models (Diab et al. 2004). Clinical trials evaluating RXR agonists for chronic MS are anticipated as a licensed RXR agonist, bexarotene, is already in clinical use for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and cutaneous T cell lymphoma (Cramer et al. 2012; Rodgers et al. 2013).

Several transcription factors such as Olig1, Olig2 Sox8, Sox10, and Sox17 are known to play important roles in differentiation and maturation of OPCs (Arnett et al. 2004; Ligon et al. 2006; Islam et al. 2009; Stolt et al. 2004; Moll et al. 2013). Olig1 and Olig2 belong to the large family of basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factors that function widely in cellular development and differentiation. They play partly overlap roles in developmental myelination and remyelination of CNS (Zhou and Anderson 2002; Dai et al. 2015; Li et al. 2007). Studies on transgenic rodent have showed that both of these transcription factors play essential role in remyelination in the context of white matter injury (Arnett et al. 2004; Maire et al. 2010). Overexpression of Olig1 and Olig2 may provide potential therapeutic target to enhance myelination and remyelination in the CNS. Available studies have showed that inducible Olig2 overexpression is sufficient for enhancing OPC migration and differentiation, leading to significant remyelination (Maire et al. 2010).

The Sox family transcription factors are also play well-established roles in regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation (Stolt et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007). Based on their roles, a number of available studies have evaluated their potential therapeutic role in myelin repair. For instance, overexpression of Sox17, as inducer of OPC differentiation and suppressor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, has led to remyelination of white matter lesion (Stolt et al. 2004).

Unquestionably, the components of extracellular environment radically altered in MS lesions to impact a number of functions, including cell migration and differentiation. Thus, more effective remyelination would likely be achieved if the local environment within lesions could be restored. To this end, clearance of myelin debris and ECM or other inhibitory factors produced by astrocytes may enhance remyelination. Therapeutically targeting of CSPGs, achieved through enzymatic degradation and interfering with enzymes involved in CSPG biosynthesis provide potentially effective approaches in promoting OPCs differentiation and migration in the presence of CSPGs (Back et al. 2005). The inhibitory nature of CSPGs has been indicated to become attenuated by the enzyme chondroitinase ABC (ChABC), which degrades inhibitory glycosaminoglycan side chains from the CSPG core protein. Additionally, treatment with the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 also reverses the observed inhibition, implicating the activation of Rho kinase in the CSPG inhibition of OPC growth. In a recent study, administration of a fluorinated analogue of N-acetyl-glucosamine called Fluorosamine, reduces the inhibitory nature of this ECM on oligodendrocyte which reduced the synthesis of CSPGs by astrocytes and subsequently led to the promotion of remyelination both in vivo and in vitro (Keough et al. 2016).

Even though attempts to enzymatic digestion of ECM have generated promising results in the context of spinal cord injuries (SCI) (Starkey et al. 2012; Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al. 2012), this approach is favorable for SCI due to the defined local area of damage which is easily accessed for ECM-degrading enzymes. The challenge for such an approach in MS is currently unpredictable due to the heterogeneous pattern of demyelinated lesions throughout the CNS, which makes local delivery difficult. Therefore, strategies that directly impact cells that produce ECM components, such as astrocytes, or alter oligodendrocyte responses to aberrant ECM molecules may be more successful approaches. Recently, transdifferentiation of astrocytes into neural precursors or OPCs is proposed to potentially provide effective regeneration and myelin repair approach. In this regard, reprogramming astrocytes has been achieved by using different small chemical molecules or microRNAs (Ghasemi-Kasman et al. 2016).

In addition to evaluation of approaches that directly modulate pathways involved in remyelination, high throughput drug screening assay is another course of action to identify new therapeutic agents that accelerate the differentiation of immature OPCs into mature, myelin-producing oligodendrocytes. In this regard, a number of studies have evaluated the therapeutic potentials of different collections of already known drugs (Lariosa-Willingham et al. 2016; Najm et al. 2015). The results of a recent study indicated that two drugs, miconazole and clobetasol, from NIH drug library are able to increase the number of new myelinating oligodendrocytes and enhance remyelination in a lysolecithin-induced mouse model of focal demyelination (Najm et al. 2015). Thus pharmacologically induction of remyelination by enhancing endogenous OPC differentiation may have significant therapeutic potential in MS.

Conclusion

Remyelination of MS lesions often fails as a consequence of failure to OPCs recruitment into the lesions, failure of OPCs to generate mature myelinating oligodendrocytes, and failure of oligodendrocytes to remyelinate axons. Many therapies have been developed to modulate the immune response in MS, but specific remyelinating therapies are not yet a reality. Promoting remyelination is a promising avenue for protecting axons, reversing neurologic disability, and preventing progressive disease in MS. Besides restoring the function of axons by remyelination, remyelination prevents secondary axonal damage caused by long-term demyelination which seems as the main cause of transition of relapsing–remitting MS to progressive type. Thus, it is crucial to pursue a strategy for developing myelin repair therapies. It will therefore be pivotal to further our understanding of the pathways involved in MS lesions remyelination and failure of this process.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Tarbiat Modares University, Royan institute, and Iranian Science Foundation for their support.

Abbreviations

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- CNS

Central nervous system

- PL

Proteolipid protein,

- CXCL1

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1

- sema3A

Semaphorins 3A

- LINGO-1

Leucine-rich repeat and immunoglobulin domain containing NOGO receptor interacting protein 1

- RXRs

Retinoid X receptors

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- NgR1 complex

Nogo-66 receptor complex

References

- Arnett HA, Fancy SP, Alberta JA, Zhao C, Plant SR, Kaing S, Raine CS, Rowitch DH, Franklin RJ, Stiles CD (2004) bHLH transcription factor Olig1 is required to repair demyelinated lesions in the CNS. Science 306(5704):2111–2115. doi:10.1126/science.1103709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Tuohy TM, Chen H, Wallingford N, Craig A, Struve J, Luo NL, Banine F, Liu Y, Chang A, Trapp BD, Bebo BF Jr, Rao MS, Sherman LS (2005) Hyaluronan accumulates in demyelinated lesions and inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation. Nature Medicine 11(9):966–972. doi:10.1038/nm1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer AS, Syed YA, Kang SU, Mitteregger D, Vig R, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ, Altmann F, Lubec G, Kotter MR (2009) Myelin-mediated inhibition of oligodendrocyte precursor differentiation can be overcome by pharmacological modulation of Fyn-RhoA and protein kinase C signalling. Brain : A Journal of Neurology 132(Pt 2):465–481. doi:10.1093/brain/awn334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin JM, Rajasekharan S, Kuhlmann T, Hanes I, Marcal N, Han D, Rodrigues SP, Leong SY, Newcombe J, Antel JP, Kennedy TE (2013) Full-length and fragmented netrin-1 in multiple sclerosis plaques are inhibitors of oligodendrocyte precursor cell migration. The American Journal of Pathology 183(3):673–680. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldajipour B, Mahabaleshwar H, Kardash E, Reichman-Fried M, Blaser H, Minina S, Wilson D, Xu Q, Raz E (2008) Control of chemokine-guided cell migration by ligand sequestration. Cell 132(3):463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A, Zhang H, Williams A (2013) Insufficient OPC migration into demyelinated lesions is a cause of poor remyelination in MS and mouse models. Acta Neuropathologica 125(6):841–859. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1112-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Wennerberg K (2004) Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell 116(2):167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Liu A (2003) Relationship between cell cycle molecules and onset of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Journal of Neuroscience Research 72(1):1–11. doi:10.1002/jnr.10565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles P, Hernandez MP, Stankoff B, Aigrot MS, Colin C, Rougon G, Zalc B, Lubetzki C (2000) Negative regulation of central nervous system myelination by polysialylated-neural cell adhesion molecule. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97(13):7585–7590. doi:10.1073/pnas.100076197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles P, Reynolds R, Seilhean D, Rougon G, Aigrot MS, Niezgoda A, Zalc B, Lubetzki C (2002) Re-expression of PSA-NCAM by demyelinated axons: an inhibitor of remyelination in multiple sclerosis? Brain : A Journal of Neurology 125(Pt 9):1972–1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Ughrin Y, Levine JM (2002) Inhibition of axon growth by oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences 20(1):125–139. doi:10.1006/mcne.2002.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RI, Rottkamp DM, Maric D, Barker JL, Hudson LD (2003) A role for semaphorins and neuropilins in oligodendrocyte guidance. Journal of Neurochemistry 85(5):1262–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer PE, Cirrito JR, Wesson DW, Lee CY, Karlo JC, Zinn AE, Casali BT, Restivo JL, Goebel WD, James MJ, Brunden KR, Wilson DA, Landreth GE ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models. Science 335 (6075):1503-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cunnea P, Mhaille AN, McQuaid S, Farrell M, McMahon J, FitzGerald U (2011) Expression profiles of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related molecules in demyelinating lesions and multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 17 (7):808-818. doi:10.1177/1352458511399114 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Czopka T, Von Holst A, Schmidt G, Ffrench-Constant C, Faissner A (2009) Tenascin C and tenascin R similarly prevent the formation of myelin membranes in a RhoA-dependent manner, but antagonistically regulate the expression of myelin basic protein via a separate pathway. Glia 57(16):1790–1801. doi:10.1002/glia.20891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Bercury KK, Ahrendsen JT, Macklin WB (2015) Olig1 function is required for oligodendrocyte differentiation in the mouse brain. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 35(10):4386–4402. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4962-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MR, Polito A, Levine JM, Reynolds R (2003) NG2-expressing glial progenitor cells: an abundant and widespread population of cycling cells in the adult rat CNS. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences 24(2):476–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan S, Hesaraki M, Soleimani M, Mirnajafi-Zadeh J, Fathollahi Y, Javan M (2016) Oct4 transcription factor in conjunction with valproic acid accelerates myelin repair in demyelinated optic chiasm in mice. Neuroscience 318:178–189. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan S, Javan M, Pourabdolhossein F, Mirnajafi-Zadeh J, Baharvand H (2012) Basic fibroblast growth factor potentiates myelin repair following induction of experimental demyelination in adult mouse optic chiasm and nerves. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience : MN 48(1):77–85. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9777-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab A, Hussain RZ, Lovett-Racke AE, Chavis JA, Drew PD, Racke MK (2004) Ligands for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and the retinoid X receptor exert additive anti-inflammatory effects on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of Neuroimmunology 148(1–2):116–126. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Baranzini SE, Zhao C, Yuk DI, Irvine KA, Kaing S, Sanai N, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH (2009) Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes & Development 23(13):1571–1585. doi:10.1101/gad.1806309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson K, Reid M, See J, Crenshaw EB 3rd, Grinspan JB (2009) Wnt signaling is sufficient to perturb oligodendrocyte maturation. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 42(3):255–265. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Enright F, Andrews JL, Newell KA, Pantelis C, Huang XF (2014) Novel implications of Lingo-1 and its signaling partners in schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry 4 (1):e348-. doi:10.1038/tp.2013.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fewou SN, Ramakrishnan H, Bussow H, Gieselmann V, Eckhardt M (2007) Down-regulation of polysialic acid is required for efficient myelin formation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282(22):16700–16711. doi:10.1074/jbc.M610797200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini I, Vitry S, Padilla F, Casanova P, Tham TN, Fukuda M, Rougon G, Durbec P, Dubois-Dalcq M (2004) Migrating and myelinating potential of neural precursors engineered to overexpress PSA-NCAM. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences 27(2):151–162. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2004.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss B, Wintergerst ES, Bartsch U, Schachner M (1993) Molecular characterization and in situ mRNA localization of the neural recognition molecule J1-160/180: a modular structure similar to tenascin. The Journal of Cell Biology 120(5):1237–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyffe-Maricich SL, Karlo JC, Landreth GE, Miller RH (2011) The ERK2 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Regulates the Timing of Oligodendrocyte Differentiation. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31(3):843–850. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3239-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain P, Chambon P, Eichele G, Evans RM, Lazar MA, Leid M, De Lera AR, Lotan R, Mangelsdorf DJ, Gronemeyer H (2006) International Union of Pharmacology. LXIII. Retinoid X receptors. Pharmacol Rev 58(4):760–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi-Kasman M, Hajikaram M, Baharvand H, Javan M (2015) MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct conversion of astrocytes to neuroblasts. PloS one 10(6):e0127878. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi-Kasman M, Zare L, Baharvand H, Javan M (2016) In vivo conversion of astrocytes to myelinating cells by miR-302/367 and Valproate to enhance myelin repair J TERM In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gutowski NJ, Newcombe J, Cuzner ML (1999) Tenascin-R and C in multiple sclerosis lesions: relevance to extracellular matrix remodelling. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology 25(3):207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Hwang SI, Roy DB, Lundgren DH, Price JV, Ousman SS, Fernald GH, Gerlitz B, Robinson WH, Baranzini SE, Grinnell BW, Raine CS, Sobel RA, Han DK, Steinman L (2008) Proteomic analysis of active multiple sclerosis lesions reveals therapeutic targets. Nature 451(7182):1076–1081. doi:10.1038/nature06559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner PJ, Power AE, Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Palmer TD, Winkler J, Thal LJ, Gage FH (2000) Proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells throughout the intact adult rat spinal cord. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 20(6):2218–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking MP, Tirotta E, Ransohoff RM, Lane TE (2010) CXCR2 signaling protects oligodendrocytes and restricts demyelination in a mouse model of viral-induced demyelination. PLoS One 5(6):e11340. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JK, Jarjour AA, Nait Oumesmar B, Kerninon C, Williams A, Krezel W, Kagechika H, Bauer J, Zhao C, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chambon P, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ (2011a) Retinoid X receptor gamma signaling accelerates CNS remyelination. Nature Neuroscience 14(1):45–53. doi:10.1038/nn.2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JK, Jarjour AA, Oumesmar BN, Kerninon C, Williams A, Krezel W, Kagechika H, Bauer J, Zhao C, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chambon P, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJM (2011b) Retinoid X receptor gamma signaling accelerates CNS remyelination. Nature Neuroscience 14(1):45–53. doi:10.1038/nn.2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Lin L, Lee X, Shao Z, Mendes S, Snodgrass-Belt P, Sweigard H, Engber T, Pepinsky B, Yang L, Beal MF, Mi S, Isacson O (2007) Inhibition of the leucine-rich repeat protein LINGO-1 enhances survival, structure, and function of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(36):14430–14435. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700901104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Fyffe-Maricich SL, Furusho M, Miller RH, Bansal R (2012) ERK1/ERK2 MAPK signaling is required to increase myelin thickness independent of oligodendrocyte differentiation and initiation of myelination. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 32(26):8855–8864. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0137-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MS, Tatsumi K, Okuda H, Shiosaka S, Wanaka A (2009) Olig2-expressing progenitor cells preferentially differentiate into oligodendrocytes in cuprizone-induced demyelinated lesions. Neurochemistry International 54(3–4):192–198. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Shankar SL, Shafit-Zagardo B, Massimi A, Lee SC, Raine CS, Brosnan CF (2002) Multiple sclerosis: re-expression of a developmental pathway that restricts oligodendrocyte maturation. Nature Medicine 8(10):1115–1121. doi:10.1038/nm781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Schut D, Wang J, Fehlings MG (2012) Chondroitinase and growth factors enhance activation and oligodendrocyte differentiation of endogenous neural precursor cells after spinal cord injury. PLoS One 7(5):e37589. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough MB, Rogers JA, Zhang P, Jensen SK, Stephenson EL, Chen T, Hurlbert MG, Lau LW, Rawji KS, Plemel JR, Koch M, Ling CC, Yong VW (2016) An inhibitor of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan synthesis promotes central nervous system remyelination. Nature Communications 7:11312. doi:10.1038/ncomms11312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan BW, Gotz B, Faissner A, ffrench-Constant C (1996) Tenascin-C inhibits oligodendrocyte precursor cell migration by both adhesion-dependent and adhesion-independent mechanisms. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences 7(4):322–335. doi:10.1006/mcne.1996.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippert A, Fitzner D, Helenius J, Simons M (2009) Actomyosin contractility controls cell surface area of oligodendrocytes. BMC Cell Biology 10:71. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-10-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter MR, Li WW, Zhao C, Franklin RJ (2006) Myelin impairs CNS remyelination by inhibiting oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 26(1):328–332. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2615-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariosa-Willingham KD, Rosler ES, Tung JS, Dugas JC, Collins TL, Leonoudakis D (2016) A high throughput drug screening assay to identify compounds that promote oligodendrocyte differentiation using acutely dissociated and purified oligodendrocyte precursor cells. BMC Research Notes. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2220-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LW, Cua R, Keough MB, Haylock-Jacobs S, Yong VW (2013) Pathophysiology of the brain extracellular matrix: a new target for remyelination. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14(10):722–729. doi:10.1038/nrn3550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LW, Keough MB, Haylock-Jacobs S, Cua R, Doring A, Sloka S, Stirling DP, Rivest S, Yong VW (2012) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in demyelinated lesions impair remyelination. Annals of Neurology 72(3):419–432. doi:10.1002/ana.23599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee X, Yang Z, Shao Z, Rosenberg SS, Levesque M, Pepinsky RB, Qiu M, Miller RH, Chan JR, Mi S (2007) NGF regulates the expression of axonal LINGO-1 to inhibit oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 27(1):220–225. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4175-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Lu Y, Smith HK, Richardson WD (2007) Olig1 and Sox10 interact synergistically to drive myelin basic protein transcription in oligodendrocytes. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 27(52):14375–14382. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4456-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon KL, Fancy SP, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH (2006) Olig gene function in CNS development and disease. Glia 54(1):1–10. doi:10.1002/glia.20273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Darnall L, Hu T, Choi K, Lane TE, Ransohoff RM (2010) Myelin repair is accelerated by inactivating CXCR2 on nonhematopoietic cells. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30(27):9074–9083. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1238-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, Klonowski P, Austin A, Lad N, Kaminski N, Galli SJ, Oksenberg JR, Raine CS, Heller R, Steinman L (2002) Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature Medicine 8(5):500–508. doi:10.1038/nm0502-500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maire CL, Wegener A, Kerninon C, Nait Oumesmar B (2010) Gain-of-function of Olig transcription factors enhances oligodendrogenesis and myelination. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio) 28 (9):1611-1622. doi:10.1002/stem.480 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manitt C, Kennedy TE (2002) Where the rubber meets the road: netrin expression and function in developing and adult nervous systems. Progress in Brain Research 137:425–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey JM, Amps J, Viapiano MS, Matthews RT, Wagoner MR, Whitaker CM, Alilain W, Yonkof AL, Khalyfa A, Cooper NG, Silver J, Onifer SM (2008) Increased chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan expression in denervated brainstem targets following spinal cord injury creates a barrier to axonal regeneration overcome by chondroitinase ABC and neurotrophin-3. Experimental Neurology 209(2):426–445. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhaille AN, McQuaid S, Windebank A, Cunnea P, McMahon J, Samali A, FitzGerald U (2008) Increased expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related signaling pathway molecules in multiple sclerosis lesions. Journal of neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 67(3):200–211. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e318165b239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Hu B, Hahm K, Luo Y, Kam Hui ES, Yuan Q, Wong WM, Wang L, Su H, Chu TH, Guo J, Zhang W, So KF, Pepinsky B, Shao Z, Graff C, Garber E, Jung V, Wu EX, Wu W (2007) LINGO-1 antagonist promotes spinal cord remyelination and axonal integrity in MOG-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature Medicine 13(10):1228–1233. doi:10.1038/nm1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Lee X, Shao Z, Thill G, Ji B, Relton J, Levesque M, Allaire N, Perrin S, Sands B, Crowell T, Cate RL, McCoy JM, Pepinsky RB (2004) LINGO-1 is a component of the Nogo-66 receptor/p75 signaling complex. Nature Neuroscience 7(3):221–228. doi:10.1038/nn1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Miller RH, Lee X, Scott ML, Shulag-Morskaya S, Shao Z, Chang J, Thill G, Levesque M, Zhang M, Hession C, Sah D, Trapp B, He Z, Jung V, McCoy JM, Pepinsky RB (2005) LINGO-1 negatively regulates myelination by oligodendrocytes. Nature Neuroscience 8(6):745–751. doi:10.1038/nn1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Miller RH, Tang W, Lee X, Hu B, Wu W, Zhang Y, Shields CB, Zhang Y, Miklasz S, Shea D, Mason J, Franklin RJ, Ji B, Shao Z, Chedotal A, Bernard F, Roulois A, Xu J, Jung V, Pepinsky B (2009) Promotion of central nervous system remyelination by induced differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Annals of Neurology 65(3):304–315. doi:10.1002/ana.21581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Kuhlmann T (1812) Antel JP (2011) Cells of the oligodendroglial lineage, myelination, and remyelination. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2:184–193. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan H, Krumbholz M, Sharma R, Eisele S, Junker A, Sixt M, Newcombe J, Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R, Lassmann H, Meinl E (2010) Extracellular matrix in multiple sclerosis lesions: Fibrillar collagens, biglycan and decorin are upregulated and associated with infiltrating immune cells. Brain Pathology (Zurich, Switzerland) 20 (5):966-975. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moll NM, Hong E, Fauveau M, Naruse M, Kerninon C, Tepavcevic V, Klopstein A, Seilhean D, Chew LJ, Gallo V, Nait Oumesmar B (2013) SOX17 is expressed in regenerating oligodendrocytes in experimental models of demyelination and in multiple sclerosis. Glia 61(10):1659–1672. doi:10.1002/glia.22547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Farioli-Vecchioli S, Ceru MP (2004) Immunolocalization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid X receptors in the adult rat CNS. Neuroscience 123(1):131–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyon S, Dubessy AL, Aigrot MS, Trotter M, Huang JK, Dauphinot L, Potier MC, Kerninon C, Melik Parsadaniantz S, Franklin RJ, Lubetzki C (2015) Demyelination causes adult CNS progenitors to revert to an immature state and express immune cues that support their migration. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 35(1):4–20. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0849-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari S, Javan M, Sherafat MA, Mirnajafi-Zadeh J, Heibatollahi M, Pour-Beiranvand S, Tiraihi T, Ahmadiani A (2011) Analysis of structural and molecular events associated with adult rat optic chiasm and nerves demyelination and remyelination: possible role for 3rd ventricle proliferating cells. Neuromolecular Medicine 13(2):138–150. doi:10.1007/s12017-011-8143-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari S, Sherafat MA, Javan M, Mirnajafi-Zadeh J, Tiraihi T (2010) Visual evoked potentials and MBP gene expression imply endogenous myelin repair in adult rat optic nerve and chiasm following local lysolecithin induced demyelination. Brain Research 1351:50–56. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najm FJ, Madhavan M, Zaremba A, Shick E, Karl RT, Factor DC, Miller TE, Nevin ZS, Kantor C, Sargent A, Quick KL, Schlatzer DM, Tang H, Papoian R, Brimacombe KR, Shen M, Boxer MB, Jadhav A, Robinson AP, Podojil JR, Miller SD, Miller RH, Tesar PJ (2015) Drug-based modulation of endogenous stem cells promotes functional remyelination in vivo. Nature 522(7555):216–220. doi:10.1038/nature14335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli I, Neumann H (2010) Protective effects of microglia in multiple sclerosis. Experimental Neurology 225(1):24–28. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan SP, Flores AI, Wang F, Macklin WB (2009) Akt signals through the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway to regulate CNS myelination. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 29(21):6860–6870. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0232-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann U, Cameroni E, Pruenster M, Mahabaleshwar H, Raz E, Zerwes H-G, Rot A, Thelen M (2010) CXCR7 functions as a scavenger for CXCL12 and CXCL11. PLoS One 5(2):e9175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickles D, Chen HP, Li MM, Khankhanian P, Madireddy L, Caillier SJ, Santaniello A, Cree BA, Pelletier D, Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR, Baranzini SE (2013) Blood RNA profiling in a large cohort of multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. Human Molecular Genetics 22(20):4194–4205. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omari KM, John GR, Sealfon SC, Raine CS (2005) CXC chemokine receptors on human oligodendrocytes: implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain : A Journal of Neurology 128(Pt 5):1003–1015. doi:10.1093/brain/awh479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omari KM, Lutz SE, Santambrogio L, Lira SA, Raine CS (2009) Neuroprotection and Remyelination after Autoimmune Demyelination in Mice that Inducibly Overexpress CXCL1. The American Journal of Pathology 174(1):164–176. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2009.080350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JR, McCandless EE, Dorsey D, Klein RS (2010) CXCR4 promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(24):11062–11067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JR, Williams JL, Muccigrosso MM, Liu L, Sun T, Rubin JB, Klein RS (2012) Astrocyte TNFR2 is required for CXCL12-mediated regulation of oligodendrocyte progenitor proliferation and differentiation within the adult CNS. Acta neuropathologica 124(6):847–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton JC, Shamblott MJ, Gary DS, Belegu V, Hurtado A, Malone ML, McDonald JW (2013) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans inhibit oligodendrocyte myelination through PTPsigma. Experimental neurology 247:113–121. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaton G, Aigrot MS, Williams A, Moyon S, Tepavcevic V, Moutkine I, Gras J, Matho KS, Schmitt A, Soellner H, Huber AB, Ravassard P, Lubetzki C (2011) Class 3 semaphorins influence oligodendrocyte precursor recruitment and remyelination in adult central nervous system. Brain : A Journal of Neurology 134(Pt 4):1156–1167. doi:10.1093/brain/awr022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourabdolhossein F, Mozafari S, Morvan-Dubois G, Mirnajafi-Zadeh J, Lopez-Juarez A, Pierre-Simons J, Demeneix BA, Javan M (2014) Nogo receptor inhibition enhances functional recovery following lysolecithin-induced demyelination in mouse optic chiasm. PLoS One 9(9):e106378. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekharan S, Bin JM, Antel JP, Kennedy TE (2010) A central role for RhoA during oligodendroglial maturation in the switch from netrin-1-mediated chemorepulsion to process elaboration. Journal of neurochemistry 113(6):1589–1597. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06717.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Miller RH (1999) Contact with central nervous system myelin inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation. Developmental Biology 216(1):359–368. doi:10.1006/dbio.1999.9466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JM, Robinson AP, Miller SD (2013) Strategies for protecting oligodendrocytes and enhancing remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Discovery Medicine 16(86):53–63 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert T, Bauer J, Weissert R, Fazekas F, Storch MK (2007) Notch1 and its ligand Jagged1 are present in remyelination in a T-cell- and antibody-mediated model of inflammatory demyelination. Acta Neuropathologica 113(2):195–203. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0170-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju R, Bernasconi L, Losberger C, Graber P, Kadi L, Avellana-Adalid V, Picard-Riera N, Baron Van Evercooren A, Cirillo R, Kosco-Vilbois M, Feger G, Papoian R, Boschert U (2004) Osteopontin is upregulated during in vivo demyelination and remyelination and enhances myelin formation in vitro. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences 25(4):707–721. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Sandoval J, Swiss VA, Li J, Dupree J, Franklin RJ, Casaccia-Bonnefil P (2008) Age-dependent epigenetic control of differentiation inhibitors is critical for remyelination efficiency. Nature Neuroscience 11(9):1024–1034. doi:10.1038/nn.2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Kagawa T, Wada T, Muroyama Y, Takada S, Ikenaka K (2005) Wnt signaling controls the timing of oligodendrocyte development in the spinal cord. Developmental Biology 282(2):397–410. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert JR, Osterhout DJ (2011) The inhibitory effects of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans on oligodendrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry 119(1):176–188. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert JR, Stelzner DJ, Osterhout DJ (2011) Chondroitinase treatment following spinal contusion injury increases migration of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Experimental Neurology 231(1):19–29. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane JA, Batt C, Ma Y, Harris ZM, Trapp B, Vartanian T (2010) Hyaluronan blocks oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation and remyelination through TLR2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107(25):11555–11560. doi:10.1073/pnas.1006496107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassky N, de Castro F, Le Bras B, Heydon K, Queraud-LeSaux F, Bloch-Gallego E, Chedotal A, Zalc B, Thomas JL (2002) Directional guidance of oligodendroglial migration by class 3 semaphorins and netrin-1. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 22(14):5992–6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey ML, Bartus K, Barritt AW, Bradbury EJ (2012) Chondroitinase ABC promotes compensatory sprouting of the intact corticospinal tract and recovery of forelimb function following unilateral pyramidotomy in adult mice. The European Journal of Neuroscience 36(12):3665–3678. doi:10.1111/ejn.12017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach K, McDonald CL, Reindl M, Schweigreiter R, Bandtlow C, Martin R (2011) Nogo-receptors NgR1 and NgR2 do not mediate regulation of CD4 T helper responses and CNS repair in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS One 6(11):e26341. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stidworthy MF, Genoud S, Li WW, Leone DP, Mantei N, Suter U, Franklin RJ (2004) Notch1 and Jagged1 are expressed after CNS demyelination, but are not a major rate-determining factor during remyelination. Brain : A Journal of Neurology 127(Pt 9):1928–1941. doi:10.1093/brain/awh217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffels JM, de Jonge JC, Stancic M, Nomden A, van Strien ME, Ma D, Siskova Z, Maier O, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ, Hoekstra D, Zhao C, Baron W (2013) Fibronectin aggregation in multiple sclerosis lesions impairs remyelination. Brain : A Journal of Neurology 136(Pt 1):116–131. doi:10.1093/brain/aws313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolt CC, Lommes P, Friedrich RP, Wegner M (2004) Transcription factors Sox8 and Sox10 perform non-equivalent roles during oligodendrocyte development despite functional redundancy. Development (Cambridge, England) 131 (10):2349-2358. doi:10.1242/dev.01114 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stumm R, Kolodziej A, Schulz S, Kohtz JD, Hollt V (2007) Patterns of SDF-1alpha and SDF-1gamma mRNAs, migration pathways, and phenotypes of CXCR4-expressing neurons in the developing rat telencephalon. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 502(3):382–399. doi:10.1002/cne.21336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Taniguchi M, Yagi T, Akagi Y, Nojyo Y, Tamamaki N (2001) Guidance of glial precursor cell migration by secreted cues in the developing optic nerve. Development (Cambridge, England) 128 (17):3321-3330 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun JJ, Ren QG, Xu L, Zhang ZJ (2015) LINGO-1 antibody ameliorates myelin impairment and spatial memory deficits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Scientific Reports. doi:10.1038/srep14235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed YA, Hand E, Mobius W, Zhao C, Hofer M, Nave KA, Kotter MR (2011) Inhibition of CNS remyelination by the presence of semaphorin 3A. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31(10):3719–3728. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4930-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepavcevic V, Kerninon C, Aigrot MS, Meppiel E, Mozafari S, Arnould-Laurent R, Ravassard P, Kennedy TE, Nait-Oumesmar B, Lubetzki C (2014) Early netrin-1 expression impairs central nervous system remyelination. Annals of Neurology 76(2):252–268. doi:10.1002/ana.24201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran JQ, Rana J, Barkhof F, Melamed I, Gevorkyan H, Wattjes MP, de Jong R, Brosofsky K, Ray S, Xu L, Zhao J, Parr E, Cadavid D (2014) Randomized phase I trials of the safety/tolerability of anti-LINGO-1 monoclonal antibody BIIB033. Neurology (R) Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 1 (2):e18. doi:10.1212/nxi.0000000000000018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tsai HH, Frost E, To V, Robinson S, Ffrench-Constant C, Geertman R, Ransohoff RM, Miller RH (2002) The chemokine receptor CXCR2 controls positioning of oligodendrocyte precursors in developing spinal cord by arresting their migration. Cell 110(3):373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Sdrulla AD, diSibio G, Bush G, Nofziger D, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Barres BA (1998) Notch receptor activation inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron 21(1):63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler NA, Fuss B (2016) Extracellular cues influencing oligodendrocyte differentiation and (re)myelination. Experimental Neurology 283 (Pt B):512-530. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol. 2016.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Williams A, Piaton G, Aigrot MS, Belhadi A, Theaudin M, Petermann F, Thomas JL, Zalc B, Lubetzki C (2007) Semaphorin 3A and 3F: key players in myelin repair in multiple sclerosis? Brain : A Journal of Neurology 130(Pt 10):2554–2565. doi:10.1093/brain/awm202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff RH, Franklin RJ (1999) Demyelination and remyelination of the caudal cerebellar peduncle of adult rats following stereotaxic injections of lysolecithin, ethidium bromide, and complement/anti-galactocerebroside: a comparative study. Glia 25(3):216–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing YL, Roth PT, Stratton JA, Chuang BH, Danne J, Ellis SL, Ng SW, Kilpatrick TJ, Merson TD (2014) Adult neural precursor cells from the subventricular zone contribute significantly to oligodendrocyte regeneration and remyelination. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 34(42):14128–14146. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3491-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Liu Y, Wei P, Peng H, Winger R, Hussain RZ, Ben LH, Cravens PD, Gocke AR, Puttaparthi K, Racke MK, McTigue DM, Lovett-Racke AE (2010) Silencing Nogo-A promotes functional recovery in demyelinating disease. Annals of Neurology 67(4):498–507. doi:10.1002/ana.21935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]