Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Learning in medical education involves a multitude of practical tasks and skills that are amenable to feedback provision. Though passive feedback is given, there is a consistent gap in feedback provision and its receipt. This study aims to assess provider perspectives on feedback and learner attributes influencing the receipt of feedback in medical educational settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A parallel mixed methods study was conducted in September 2023 at a tertiary care teaching institute. A convenience sample of 40 medical teachers comprising two faculties per department and 30 students were included. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with students from each academic year for assessing the student-level factors (facilitators and barriers) in the receipt of feedback.

RESULTS:

Among the 40 medical teachers who were interviewed, the majority of 23 (57.5%) were assistant professors and nearly half of them (18; 45.0%) were below the age of 30 years. The majority of the respondents (28; 70.0%) were females, and 34 (85.0%) of them were postgraduates. Most of them (24; 60.0%) had worked for more than 10 years at the institute. It was observed that 80.0% of the respondents had given feedback to their students at some point in their careers. The major barriers for providing feedback were lack of curricular guidelines, fear of affective responses from students, burden of clinical, administrative work, and lack of perceived need by both students and teachers. DESTEP analysis of the student-level factors governing the receipt of feedback shows the effects of institutional ethics and culture, feedback model utilized, and the influence of learner behaviors, motivations, and teacher attributes.

CONCLUSION:

The study elucidates mentor- and mentee-level influencers for providing and receiving feedback. Effective teacher-student partnerships along with an optimal skill set are required to recognize the need, opportunities, and processes to provide and seek feedback. Shifting the focus from feedback giving to active feedback seeking would be a step toward creating effective and pragmatic feedback systems.

Keywords: DESTEP analysis, feedback, learner, mentor, mind map, receipt

Introduction

Feedback forms an integral part of several fields, such as psychology, administration, and economics. Feedback is the information provided by mentor or teacher, colleague, or even a friend regarding aspects related to performance of an individual in any specific area.[1] In the field of education, the concept of feedback was introduced in the past decade as specific information about the observed performance of the learner, comparing it to a model or “standard,” to improve the student’s learning and performance.[2] Effective feedback brings about improvement of the student’s performance in an interactive and non-judgmental manner. In the absence of feedback, students may feel that there are no problems with their performance and thereby lose a chance at improvement. There are several learner- and provider-level factors that influence the process of giving and receiving feedback.[3,4,5]

The provider may be unaware of the processes of giving constructive and specific feedback to the student. They may use nonverbal or verbal communication that is not intentionally directed to provide feedback about the student’s performance.[6] This may prove harmful as the student is unable to draw a constructive conclusion about their learning and evolution throughout the training. Similarly, barriers regarding receiving feedback by the learners are there as they may not be prepared to receive feedback. This hinders progress and development of the student as a person and professional shifting primary emphasis on grades leading to suboptimal performance.[7,8]

If the provider envisages that the task is performed adequately but fails to provide the feedback regarding the same, the students would be in dilemma about their performance.[9] Appropriate and timely feedback on positive performance is helpful for the future reinforcement of the skills learned by the students helping them to effectively use those in the future, whereas skipping feedback is a recipe for failure by continuation of errors and poor performance by students.[10]

This study will add to the gaps in the literature on the factors that provide insight regarding the felt need for provision of, quality, acceptability, and acceptance of feedback by students. Similarly, factors influencing feedback, such as teacher-related factors, learner factors, feedback process, feedback content, and the educational context, are also assessed. In this context, the study was developed to assess the provider- and learner-level barriers and facilitators in giving or receiving feedback for improving learning outcomes The aim of the study was to assess the perceptions of medical teachers and students in provision and receipt of feedback.

Objectives:

To assess the facilitators and barriers for giving effective feedback by medical teachers

To study the student-level facilitators and barriers for receiving feedback

To study the perceptions of teachers and students regarding the process through which the feedback is delivered.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting: A cross-sectional study was conducted using parallel mixed methods approach (qualitative and quantitative methods) for a duration of 1 month from September 2023 to October 2023. The study was conducted at a tertiary care teaching institute.

Study participants and sampling

Both mentors and mentees, that is, the medical teachers and students, were included in the study. The study included two teaching faculties from each department, yielding a sample size of 40 faculties. Similarly, three focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted for students from the preclinical, paraclinical, and the clinical subjects with nearly 6–10 participants per group, giving a sample size of 30 participants for assessing the student-level factors (both facilitators and barriers) in the receipt of feedback. The above sample size is assumed to yield adequate power on post hoc analysis for the retrospective power of an observed effect based on the sample size and parameter estimates to achieve complete data saturation.

Sampling technique: A convenience sample of teachers and students was taken at random depending upon their availability during the data collection period. The sample was stratified according to the year of graduate medical course as preclinical, paraclinical, and clinical mentors with approximately equal representation in each stratum for obtaining an internally heterogeneous sample for facilitating varied perceptions regarding facilitators and barriers to effective feedback at each level. Similarly, students from each year of undergraduate medical course were randomly recruited for conducting FGDs in a similarly stratified manner.

Ethical consideration: After obtaining the ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Ethics Committee Re-Registration Number—ECR/88/Inst/MH/2003/RR-19), the study recruited a mixed group of teaching faculties by drawing name chits and a written informed consent was obtained from each of them.

Data collection and techniques: The teachers were invited to participate in a 3-day interactive workshop on “Effective feedback in Medical Education.” The workshop was conducted on a hybrid mode with online sessions and assignments on the first 2 days and a hands-on skill development session on the 3rd day. The students were selected using a simple random sample for conducting the FGDs. Perceptions of the participating medical teachers regarding the facilitators and the barriers for providing feedback as well as student-level factors that govern the receipt of feedback were assessed using a predesigned and validated Google Form. The key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted for the teachers using a Google Form as a self-administered questionnaire, followed by a one-on-one session where their detailed responses were audio-recorded after seeking written informed consent. Three student FGDs were conducted with nine, 11, and 10 students each, respectively, from the preclinical, paraclinical, and the clinical years of study of the medical undergraduate education.

Data analysis: The quantitative data were entered in Microsoft (MS) Excel to calculate percentages and proportions of the pertinent variables. The qualitative data were transcribed, and thematic analysis was conducted to induct the themes related to the possible facilitators and barriers for the provision and receipt of feedback by the teachers as well as the students. The grounded theory was utilized as the general analytic approach, and FGD transcripts were first translated if required and transcribed using ATLAS.ti version 23 for Windows. These were then coded using the constant comparative analytic method.[11] Two coders (YP and AD) independently identified the themes and subthemes after a holistic review of the transcripts. On completion of the initial review, a codebook was developed for further analyzing the data and it was subsequently revised for the purpose of obtaining intercoder agreement of greater than 90%. Other investigators also analyzed the transcripts, for periodically checking each other’s analysis to ensure data consistency in the document analysis.

Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework for doing a thematic analysis was utilized with the following steps—Step 1: Familiarizing the data to get a general idea of the contents; Step 2: Generation of initial codes; Step 3: Inducting themes from the codes and merging codes suggesting common themes; Step 4: Review the themes; Step 5: Defining themes; and Step 6: Write-up of the themes emerging from the overall dataset supported by relevant quotes. A mind map was created based on the emergent themes to elucidate the factors that affected the provision of feedback by the teachers. Similarly, DESTEP analysis was conducted to understand the intrinsic factors, such as student beliefs, behaviors, and motivations, and extrinsic environmental factors, such as the institutional ethics, cultures, feedback models utilized, and the teacher attributes that may impact the receipt of feedback by the medical graduates. “DESTEP” analysis is an analytical framework used to study the extrinsic factors governing a particular phenomenon, in the current context the feedback receipt by students. It stands for Demographic, Economic, Sociocultural, Technological, Ecological and Political (or administrative) factors that govern student feedback.

Results

The study was conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital including the medical teachers and students as respondents. There were 40 medical teachers who were interviewed to assess the factors affecting feedback provision in their routines and 20 medical graduates who were invited to participate in FGD sessions for providing their perceptions regarding the facilitators and barriers for the receipt of feedback to improve their learning experience and performance at medical school.

Among the 40 medical teachers who were interviewed, the majority of 23 (57.5%) were assistant professors and nearly half of them (18; 45.0%) were below 30 years of age. The majority of the respondents (28; 70.0%) were females, and 34 (85.0%) of them were postgraduates. Most of them (24; 60.0%) had worked for more than 10 years at the medical college [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants for the KIIs (n=40)

| Characteristics | Number | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | ||||

| Senior resident | 4 | 10.0 | ||

| Tutor | 6 | 15.0 | ||

| Assistant professor | 23 | 57.5 | ||

| Associate professor | 5 | 12.5 | ||

| Professor | 2 | 5.0 | ||

| Age | ||||

| 25-30 years | 18 | 45.0 | ||

| 31-40 years | 15 | 37.5 | ||

| >40 years | 7 | 17.5 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 12 | 30.0 | ||

| Female | 28 | 70.0 | ||

| Educational qualifications | ||||

| MBBS | 6 | 15.0 | ||

| MD/MS | 34 | 85.0 | ||

| Years in service | ||||

| ≤10 years | 16 | 40.0 | ||

| >10 years | 24 | 60.0 |

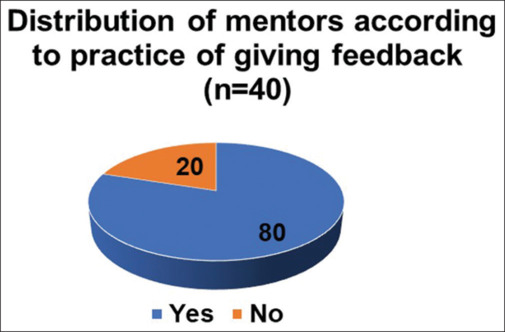

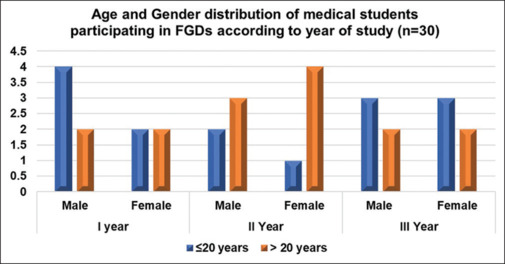

It was observed that 80.0% of the respondents had given feedback to their students at some point in their careers [Figure 1]. The age and gender distribution of the students from each academic year who participated in the FGDs is given in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Mentors who gave feedback (n = 40)

Figure 2.

Baseline characteristics of the medical students participating in FGDs (n = 30)

When the determinants of giving feedback such as what motivates and facilitates them to give feedback to the students was inquired about, several thematic areas that were obtained along with their supporting quotes are described below:

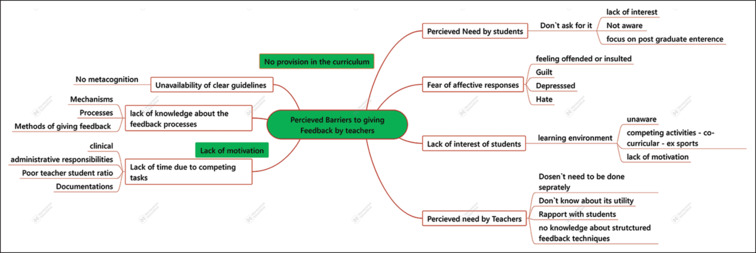

The main themes and their subthemes for facilitators and barriers for providing student feedback as stated by the medical teachers were identified through the transcripts. These have been described along with their supporting quotes in Table 2. Similarly, the student-level factors that affect the receipt of feedback along with its supporting quotes are described in Table 3. Perceived challenges by the teachers for providing effective feedback illustrated in the mind map are depicted in Figure 3. The major barriers are the lack of curricular guidelines regarding the processes for giving feedback, along with factors, such as fear of affective response from students and lack of perceived need by both students and teachers.

Table 2.

Themes and major subthemes with supporting quotes for the teacher-level facilitators and barriers for the provision of feedback to their students (n=40)

| Themes identified | Major subthemes | Participant ID | Participant quotes supporting the theme and subtheme | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Teacher-level facilitators for giving feedback (teacher attributes) | ||||||

| Knowledge and motivation | Awareness | T29F T23M |

“You cannot give feedback if you aren’t aware of its necessity”

“For doing this (giving feedback), we need to be updated on the correct methods and techniques of providing effective feedback” |

|||

| Beneficence | T15M T12F T26M |

“Giving feedback to students doesn’t have to be only after their exams but ongoing feedback even through our daily routines proves to be useful in improving their learning and performance”

“Feedback not only helps them learn better but also changes the ways in which their personality is shaped” “Not only does it (feedback) help with studies but also brings about an overall development of their value ecosystem and can be utilized to impart AETCOM skills to the students” |

||||

| Improve performance | T17F T23M |

“I have seen dramatic improvement in the performance of students when they receive timely and appropriate feedback”

“Once you provide the specific feedback based on their performance, they are willing to improve themselves and do it a whole lot better afterwards” |

||||

| Good rapport with students | Approachable | T12F T38F T21M |

“Students being able to reach you and discuss their problems makes giving them feedback all the more easier”

“Unless you build the confidence in your students that you can be approached for any of their problems, they will not be willing to reach you to share their difficulties or get feedback from you” “The mentorship program ‘Anubandh’ at our institute is a very good platform for students to approach the teachers and the teachers as mentors are in a position to give effective feedback for enhancing their performance” |

|||

| Non-judgmental | T15F T08M |

“The cardinal rule is not to judge them if they are willing to share regarding their performance with you as judging them will further close the doors and they will not be receptive to what you have to offer them”

“Many a times students prefer to be listened to without being judged and this gives us an opportunity to share our own expectations about their learning and performance with them” |

||||

| Recognized mentor (popular among students) | T01F T20F |

“It’s not difficult (to give feedback) if you are popular among the students as they will themselves come to you for it”

“Most of the students have a goto mentor whom they are associated with through participation in certain activities guided by them, mostly extracurricular like sports or annual events” |

||||

|

Teacher-level barriers for giving feedback | ||||||

| Clear guidelines | Curricular guidelines are not available | T03M T09F |

“The present curriculum has no clear directives for feedback and the guidelines to do the same”

“The new CBME curriculum has elaborated on the assessment part adequately, however the details about feedback and how it is to be delivered are sadly missing” |

|||

| Unfamiliar with FB processes | Mechanisms | T24F | “For years together, I was giving feedback in my own ways, getting to know the mechanisms for giving it has helped a lot” | |||

| Processes | T37F T01F |

“When I attended the MET workshop, that was the first time I came across so many ways in which feedback could be given constructively otherwise I was still following the traditional way learnt from our ancient mentors”

“Earlier we were unaware but nowadays, it has become very easy to provide feedback using the structured processes developed for it” |

||||

| Fear of affective responses from students | Feeling insulted | T22F T39M |

“Today’s children lack tolerance towards criticism even if given in a positive manner, so it has to be done very cautiously”

“The student’s may feel offended if you tell them regarding their poor performance and need for doing better” |

|||

| Insecure | T17F T34M |

“One thing that sometimes deters us from giving feedback to them is also the fact that we do not wish to be seen in bad light by our students”

“You need to be cautious of how you explain them regarding their performance as offending them would ruin your image” |

||||

| Guilt | T11F | “The method adopted for providing feedback has to be selected cautiously, even choosing the words wisely helps to boost their morale rather than making them feel guilty about their performance” | ||||

| Depressed | T02M T40F |

“Some of the sensitive students can be further depressed if they are harshly reprimanded regarding their poor performance”

“Moreover, the students of the present generation are very pampered at their homes and cannot be approached strictly for the fear of causing them to be depressed” |

||||

| Lack of time | Parallel clinical and administrative tasks | T32M | “Here we are so boggled down with the patients that we do not even have the opportunity to think about how and when to give feedback to them” | |||

| Poor teacher-student ratio | T10F T11F |

“There are nearly 200 students in each academic year, even the clinical postings have nearly 30-40 students making it difficult to observe each one of them with very few teachers around”

“The clinical disciplines are mostly fraught with lack of staff and multitude of clinical and administrative tasks making it a chore to keep track of all the students that we are teaching” |

||||

| Perceived need | Learning objectives | T28M T21M |

“They (students) lack clarity of their own learning objectives and are often guided by what their peers are planning to learn”

“Students seldom take the initiative to introspect on their learning needs or express them succinctly, so that the mentors are able to cater to their specific learning goals” |

|||

| Learning environment | T16F T33F |

“With changing times, in addition to their studies emphasis is laid on other co-curricular activities and events that may divert the students from their studies so, balance needs to be created between the curricular and co-curricular activities”

“The institutional philosophy has a strong bearing on the learning experience of the students” |

||||

| Student’s motivation | T19F | “It is very rare to find students who are self-motivated, therefore, it becomes imperative for the teachers to provide a stimulating environment for facilitating their learning to a great extent” | ||||

*Participant ID format T=teacher; M=male; F=female

Table 3.

Themes and subthemes with supporting quotes for student-level factors affecting the receipt of feedback (n=30)

| Themes identified | Major subthemes | Participant ID | Supporting quotes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Student-level factors affecting receipt of feedback | ||||||

| Institutional ethics and culture | Learning environment | S15M S02M |

“The environment at the college should facilitate seeking feedback for our exam performance but we are just shown the internal assessment marks and no further discussion takes place”

“There is not much interest for explaining the reasons for our poor performance or a redressal portal if we think that our marks are not at par with our exam performance” |

|||

| Free communication | S28F S25F |

“When we wish to discuss with our teachers, they are sometimes busy with their tasks and meetings so we are not able to discuss our difficulties with them”

“We are afraid that they (teachers) may think that we are interrupting their important work” |

||||

| Channels for feedback | S21F S29M |

“Our mentor in the Anubandh mentorship program guides us regarding the ways in which we can improve our studies”

“The group sessions after our exams that explain the deficiencies in our exam performance are helpful for focussing on the weaker aspects” |

||||

| Feedback model and processes | Positive FB | S09M | “If the teachers appreciate us for our work in a good manner, we are satisfied and want to do well every time” | |||

| Friendly manner | S03F S28M |

“We feel much better receiving inputs from ….sir as he says that in a very friendly way”

“If things are explained in a good way, them it motivates us to take up their suggestions” |

||||

| Criticism | S11M S06F |

“Criticising for improving our performance doesn’t serve the purpose as it dampens our enthusiasm rather than lifting our spirits”

“We have been subjected to it so often that it ceases to motivate us to learn even from our mistakes” |

||||

| Negative FB | S16F | “Stating the facts harshly only deters us from doing what is being told to us” | ||||

| Learner’s attitudes, beliefs, and motivation | Expectations related to their performance | S22F S07M |

“We are never explained about what is expected out of us, so we do not have any set goals for ourselves”

“We should be sensitized at the outset as to what we need to do during the course very precisely so that we conduct ourselves accordingly” |

|||

| Interest and motivations | S01M | “If I am interested in learning, I will make sure to go to my mentor and request for pointers in improving my performance” | ||||

| Learning objectives and learning needs | S12F | “….poor scorers need that additional help as compared to the brilliant ones” | ||||

| Value system | S17M S08M |

“….it is easier for the confident ones to go to the teachers and get their feedback but for people like us it is a herculean task”

“If the teachers care for our wellbeing, then they definitely tell us about our studies and exam performance” |

||||

| Perceived role of teacher | S21F | “….friendly ones (teachers) are best received by the students as their mentors and are very approachable even for matters other than studies” | ||||

| Teacher attributes | Facilitator | S09M S11M |

“Criticizing us versus helping our progress, we prefer the latter ones for taking feedback”

“We never have the feeling that they will facilitate our journey as we are never taken into consideration” |

|||

| Non-judgmental | S25F S04F |

“….if they start calling us names we cannot take in or act on their suggestions”

“They just label us as irresponsible even before understanding our genuine problems” |

||||

| Approachable | S19F S07M S29M |

“I am sure that I will never seek feedback from …. as a I am very afraid of their bad temper”

“We always find some of the teachers to be very difficult to talk with and wish that we never have to have any conversations with them” “….if we are sent back often then we do not wish to seek help from them” |

||||

| Recognition | S21F S22F S18M |

“….ma’am is so kind and soft spoken that we are not afraid to ask her about our difficulties”

“Our sports committee chairperson is our goto mentor for our difficulties as he is always there for us” “we follow what our seniors tell us about the teachers and this helps us to choose our preferred mentors” |

||||

| Good listener | S01M S27F S08M |

“Sometimes, we are not allowed to share our side of the story”

“if they listen to our problems, then why will we not be willing to implement their suggestions” “The solutions are not based on our problems as no one tries to uncover them” |

||||

| Motivated | S16F S29M |

“Some of them are very inspiring and always help us in learning new skills”

“….the enthusiasm with which they teach helps us learn better” |

||||

*Participant ID format S=student; M=male; F=female

Figure 3.

Mind map showing perceived barriers to giving feedback by the teachers

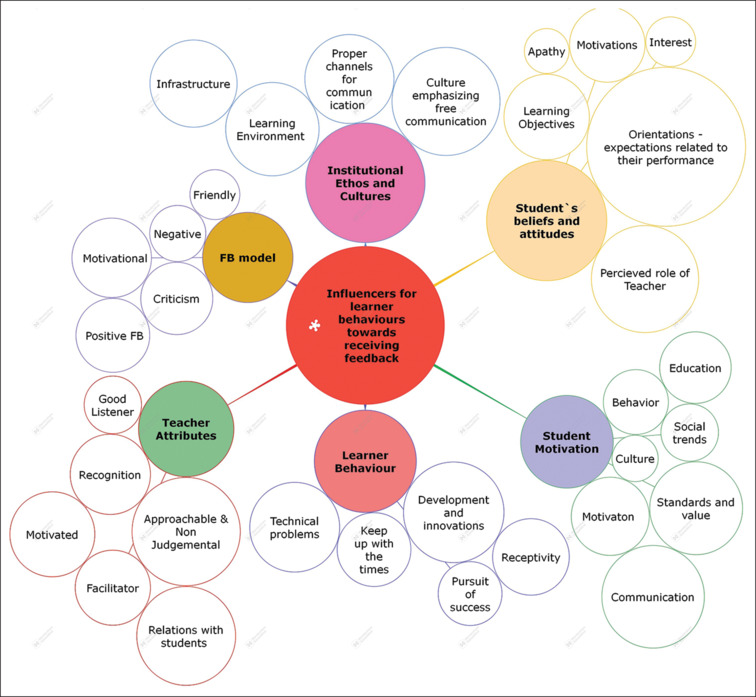

Similarly, Figure 4, which is a DESTEP analysis of the student-level factors governing the receipt of feedback, shows the effects of institutional ethics and culture, the kind of feedback model utilized, and the influence of learner behaviors and motivations along with teacher attributes on receiving feedback effectively [Figure 4]. This has also been elaborated in the form of four major themes and its subthemes in Table 3. Institutional culture that favored free communication as well as a healthy learning environment was considered to be crucial by the students for facilitating feedback. Similarly, positive feedback techniques, teacher’s attributes, such as friendliness, being non-judgmental, and genuine interest, and motivation were supportive for feedback. Learner attitude toward feedback indicated that their learning needs and objectives as well as motivations played an important role in receiving feedback from them.

Figure 4.

DESTEP analysis for the student-level factors affecting feedback

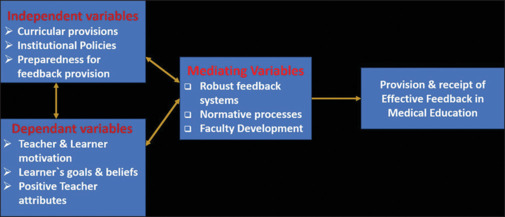

Figure 5 describes the conceptual framework that illustrates the major factors affecting the provision of feedback by the teachers and its receipt by the students. The theory that emerges from the framework indicates that the provision of feedback is chiefly guided by factors, such as curricular provision for feedback, institutional policies, and mentor as well as mentee preparedness for feedback. The exploratory findings revealed the factors that govern the feedback processes including teacher and learner motivation, their learning goals, and beliefs as well as certain teacher attributes, such as friendliness, approachability, and being non-judgmental. These are successfully mediated through robust feedback systems and equipping as well as training faculties for providing effective feedback and preparing the learners to receive the same in a non-threatening environment.

Figure 5.

Conceptual framework for effective feedback in medical education

Discussion

Considering the rising use of current interactive teaching learning methods in medical education, feedback plays a vital role in the student’s achievements. This study explored the teacher-level facilitators and barriers in providing feedback as well as the factors related to the students that governed the receipt of feedback at a tertiary care teaching hospital. This was helpful in assessing the ground reality of how feedback is provided and received by the medical students and its effect on their learning behaviors.

There were two core themes that came up during the KIIs with teachers that facilitated effective feedback, which were teacher’s knowledge and motivation as well as their rapport with the students. There were several subthemes that further elucidated their point of view [Table 2]. The barriers for giving feedback were enumerated under five major themes and several subthemes under each of the core themes [Table 2]. These included lack of curricular guidelines, time, fear of affective responses from students, unfamiliarity with feedback processes, and learner beliefs and attitudes toward the perceived need for feedback.

Factors facilitating feedback provision: The most important step in facilitating feedback in our setting was observed to be the mutual understanding about the purpose of giving feedback by both the providers and the learners. This emphasizes the importance of our feedback mind map as a tool to understand the challenges for giving feedback and to align it with learning intentions of both the mentors and the mentees. The feedback mind map supported meaningful discussion with teachers about their perceptions around feedback encounters. It has also helped us understand the factors that influence effective feedback and its receipt by the end users.

-

Teacher’s knowledge and motivation

One of the major facilitators for providing feedback was teacher’s knowledge and involvement in the student’s learning processes as harnessed by their own motivation levels for teaching the students. Learned and motivated teachers made it a point to provide feedback on each session conducted by them. This was also evident in the studies conducted by McGinness et al. and Ramani et al.[12,13]

-

Rapport with students

Another determinant for effective feedback was the teacher-student relationships that fostered a positive environment for feedback. The students claimed that they perceived feedback given by the teachers who they had a good rapport with and were particularly instrumental in their performance and learning outcomes. This has also been established by other studies that indicate the need for meaningful teacher-student relationships as the driving force for providing effective feedback. Other teacher attributes that were found to be favorable were being approachable, non-judgmental, and considerate of the student’s emotions while giving feedback as also emphasized by the previous studies.[13,14,15]

Barriers for providing feedback: The major barriers encountered in the study were the lack of curricular guidelines regarding the processes for giving feedback, along with other factors, such as fear of affective response from the students and lack of perceived need by both the students and the teachers. Also, an important factor that was elucidated was that the teachers are boggled down with several competitive tasks apart from academics that further takes away the time that could have been allotted to giving feedback to the students.

-

Paucity of curricular guidelines

Some of the previous studies have also reflected on the need for curricular guidelines for feedback processes and the role of teachers in providing effective feedback for positive learning outcomes.[12,13,14,15,16] The earlier researchers have argued that how are the teachers supposed to do what they are not directed to do according to the mandates.[13,14,15] Curricular reforms are needed for effective implementation of feedback systems in medical education.

-

Lack of time due to competing tasks

Another major barrier to giving feedback emerged to be the competing tasks of patient care, administration, and education that often left with little time for giving feedback. This was also emphasized by a few studies that deliberated upon the duty restrictions for maintaining good relationships between teachers and learners to facilitate feedback.[17,18,19,20] They were of the opinion that the curricula should include instructions on processes for conducting ongoing feedback rather than independent “sandwich” sessions and should give pointers on how to effectively use evaluation tools to provide feedback and facilitate discussions with learners.[21,22] Another effective mechanism for handling the problem of competing tasks interfering with feedback was to incorporate formal feedback sessions at the outset and after conducting evaluations with real-time feedback which is less time-consuming as the ongoing method of providing feedback.[23]

-

Fear of affective responses

One of the major undermining factors for giving feedback was the fear of upsetting students with honest and critical feedback. This would invoke several negative emotions among the students, such as feeling hurt, sad, or even depressed after obtaining the feedback. This can further weaken the resolve of already poor-performing students instead of encouraging them. The studies by Ramani et al.[4] and Noble et al.[11] also state that provision of feedback without affective responses requires an understanding of the process and skills on the part of the ones imparting it. However, these should not deter the mentor from providing feedback in the best interests of their learners.

-

Unfamiliarity with feedback processes

Many faculties were unaware of the content, timing, and structuring the feedback to maximize the learning output gained from it. This was also stated by other studies that have emphasized on the need of faculty development in this aspect of providing effective feedback through enhancing the knowledge about effective feedback processes.[24,25,26] Honing the skills of faculties in the right processes and methods for effective feedback will be the best policy for tackling this barrier.[25,26]

-

Lack of felt need by students

Another major factor that proved to be a hinderance in giving feedback by the faculties was that there was the absence of a felt need for feedback from the student’s side. This could be due to the shift in the learning patterns from school education that provided little or no feedback, making them believe that only the scores obtained after the evaluations are the form of feedback that is provided. This has been illustrated by Ramani et al.[22] who emphasizes on creating the demand for feedback from the student’s side by creating awareness about the necessity for effective feedback for facilitating learning.

Factors influencing the receipt of feedback: However, the students shared the factors influencing the receipt of feedback that are described under four major themes: institutional cultures, feedback models used, and learner and teacher attributes as described in the DESTEP analysis [Figure 4]. Several studies conducted previously have exhibited many themes that are consistent with those identified in this study.[12,13,16] When determinants for feedback giving, feedback seeking, and feedback receiving were inquired about, the learners discussed about the factors that promote feedback seeking from teachers like their engagement with students, motivations, and friendly attitude as mentioned by the terms, such as, “approachable,” “available,” and “non-judgemental.” The factor, such as a safe and wholesome environment for feedback, was also consistent with prior studies.[14,15]

-

Institutional core values

The institutional learning culture came up as a key influence on student feedback behaviors and necessitates commitment at the institutional level. Similarly, the educator also needs to acknowledge the learning culture so that there is a great potential for implementing an effective feedback system. This can be brought about by standardized faculty training, effective long-term relationships between mentors and learners, and a more free and open system of responding to learner needs.[23,24] The learners also emphasized as reported by other studies that positive learning environments allays their fears encouraging them to ask questions for clarification and request support from teachers, enabling them to work with an inquiring mind thereby enhancing their knowledge as well as skills.[25,26]

-

Student’s attitude and beliefs

Other factors that emerged as determinants of learners’ perceptions regarding feedback were related to their attitudes toward learning, their beliefs, and their feedback literacy skills, to enable them to recognize and seek feedback specific to their own learning needs. This makes engaging and empowering students to take initiative to assess their own learning needs and actively seek feedback from their mentors in the fast-paced medical education settings. Thus, shifting the focus from feedback giving to active feedback seeking would be a step toward creating effective and pragmatic feedback systems.[25,26,27,28]

-

Feedback models and processes

Another important factor hindering effective feedback was observed to be the dearth of applying appropriate feedback models that would enhance its receipt by learners. This might have stemmed from the final supervisor’s lack of awareness about effective feedback delivery mechanisms. Bransen et al.[29] and colleagues have demonstrated that poorly delivered feedback is often perceived as a negative experience by the trainee. Developing a structured and consistent approach keeping in mind the trainee’s goals can prove to be highly effective.[30,31]

Some of the evidence-based feedback models, such as the “R2C2” model, were conducted in four phases: rapport building, examining the receiver reactions to feedback, exploring feedback content, and coaching for change.[32] The feedback given using this model is effective as it is based on building relationships and approaching feedback as a facilitatory mechanism rather than being critical and mean. Another approach is the SET-GO model which is a student-centered descriptive approach centered on outcomes. It comprises what learner saw as the supervisor, what else was observed, what did the learner think, what goal would they like to achieve, and any offers how learners get there.[33] The technique is non-judgmental as instead of judging the learner, and feedback is provided on what is learned and on the manner of learning focusing on learner’s specific goals. This allows the students to participate actively in the feedback process.

The emergent conceptual models for barriers to providing and seeking or receiving feedback grounded in the data generated during the in-depth interviews and the discussions also emphasize on the need for suitable models for feedback that would stand the tests of complexity and the context of the learning culture of the students. The feedback process is governed by a network of factors described in the mind map and the DESTEP analysis showing the complexity of the multitude of factors surrounding the feedback exchange. Configuring how learners would respond to feedback and what impact it creates on their learning is an important gap that needs to be assessed further.

Conclusion

Though feedback is provided as a part of medical education, it is not conducted in a structured manner or as a systematic approach. Several teacher attributes that were identified as barriers by the study need to be emphasized through faculty development programs, and student-related factors should be taken into consideration while providing feedback. Active feedback seeking should be encouraged and incorporated as a policy recommendation.

Recommendations

A holistic approach based on effective teacher-student partnerships within the institutional and curricular framework for providing effective feedback needs to be established and strengthened with an optimal skill set to recognize the need and the appropriate opportunity to provide and seek feedback.

Key messages

There is a gap in the provision of feedback by teachers due to certain barriers, and students are also unaware of the importance of feedback in supporting their learning.

Effective teacher-student partnerships along with an optimal skill set are required to recognize the need, opportunities, and processes to provide and seek feedback. Shifting the focus from feedback giving to active feedback seeking would be a step toward creating effective and pragmatic feedback systems.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We express our sincere gratitude to the administrative authorities of our institute for permitting us to conduct the study. We are also thankful to the teachers who took valuable time from their busy schedules for participating in the study and expressing their valuable opinions. Lastly, our study would not have been possible without the enthusiastic support and response accorded by our students who are the major stakeholders in this research.

References

- 1.Wilbur K, Ben Smail N, Ahkter S. Student feedback experiences in a cross-border medical education curriculum. Int J Med Educ. 2019;10:98–105. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5ce1.149f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carless D, Boud D. The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 2018;43:1315–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molloy E, Boud D, Henderson M. Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assess Eval High Educ. 2020;45:527–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramani S, Konings KD, Mann KV, Pisarski EE, Van Der Vleuten CPM. About politeness, face, and feedback: Exploring resident and faculty perceptions of how institutional feedback culture influences feedback practices. Acad Med. 2018;93:1348–58. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann MH, Monteiro R, Foggiatto C, Gomes RZ. The teacher and the art of evaluating in medical teaching at a University in Brazil. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2019;43:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leitão Maia I, Cordeiro M, Oliveira X, Maria C, Oliveira C, Kristopherson LA. Feedback strategy adapted for university undergraduate student. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2018;42:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Wang T, Ren X. Inner speech in the learning context and the prediction of students’ learning strategy and academic performance. Educ Psych. 2020;40:535–49. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand PLP, Jaarsma ADC, van der Vleuten CPM. Driving lesson or driving test? A metaphor to help faculty separate feedback from assessment. Perspect Med Educ. 2020:10. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00617-w. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00617-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thrien C, Fabry G, Härtl A, Kiessling C, Graupe T, Preusche I, et al. Feedback in medical education – A workshop report with practical examples and recommendations. GMS J Med Educ. 2020;37:1–19. doi: 10.3205/zma001339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant A. New York (NY): Viking; 2021. Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noble C, Billett S, Armit L, Collier L, Hilder J, Sly C, et al. “It’s yours to take”: Generating learner feedback literacy in the workplace. Adv in Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25:55–74. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGinness HT, Caldwell PHY, Gunasekera H, Scott KM. An educational intervention to increase student engagement in feedback. Med Teach. 2020;42:1289–97. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1804055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramani S, Konings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: Swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med Teach. 2019;41:625–31. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molloy E, Bearman M. Embracing the tension between vulnerability and credibility: ‘Intellectual candour’ in health professions education. Med Educ. 2019;53:32–41. doi: 10.1111/medu.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little D, Green DA. Credibility in educational development: Trustworthiness, expertise, and identification. High Educ Res Dev. 2021;41(158):1–16. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1871325. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajjawi R, Regehr G. When I say … feedback. Med Educ. 2019;53:652–4. doi: 10.1111/medu.13746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai CM, Bertram K, Chahine S. Feedback credibility in healthcare education: A systematic review and synthesis. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31:923–33. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01167-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamothe DB, Rowe J, Boet S, Denis-Leblanc M. S’outiller pour mieux participer à la rétroaction: Un nouveau modèle cognitivo-comportemental destiné aux apprenants en médecine [Empowering yourself to better participate in feedback: A new cognitive-behavioural model for medical learners] Can Med Educ J. 2023;14:6–13. doi: 10.36834/cmej.74419. [French] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tielemans C, De Kleijn R, Van Der Schaaf M, Broek Van der S, Westerveld T. The Westerveld framework for interprofessional feedback dialogues in health professions education. Assess Eval High Educ. 2021;48(6):1–17. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1967285. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armson H, Lockyer JM, Zetkulic M, Könings KD, Sargeant J. Identifying coaching skills to improve feedback use in postgraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53:477–93. doi: 10.1111/medu.13818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Kleijn RAM. Supporting student and teacher feedback literacy: An instructional model for student feedback processes. Assess Eval High Educ. 2021;48(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramani S, Könings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CP. Feedback redefined: Principles and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:744–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04874-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan TM, Dowling S, Tastad K, Chin A, Thoma B. Integrating training, practice, and reflection within a new model for Canadian medical licensure: A concept paper prepared for the Medical Council of Canada. Can Med Educ J. 2022;13:68–81. doi: 10.36834/cmej.73717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ott MC, Pack R, Cristancho S, Chin M, Van Koughnett JA, Ott M. “The most crushing thing”: Understanding resident assessment burden in a competency-based curriculum. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:583–92. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00050.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutrer WB, Atkinson HG, Friedman E, Deiorio N, Gruppen LD, Dekhtyar M, et al. Exploring the characteristics and context that allow master adaptive learners to thrive. Med Teach. 2018;40:791–6. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1484560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sargeant J, Lockyer JM, Mann K, Armson H, Warren A, Zetkulic M, et al. The R2C2 model in residency education: How does it foster coaching and promote feedback use? Acad Med. 2018;93:1055–63. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lockyer J, Armson H, Könings KD, Lee-Krueger RCW, des Ordons AR, Ramani S, et al. In-the-moment feedback and coaching: Improving R2C2 for a new context. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12:27–35. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00508.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rassbach CE, Blankenburg R. A novel pediatric residency coaching program: Outcomes after one year. Acad Med. 2018;93:430–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bransen D, Govaerts MJB, Sluijsmans DMA, Driessen EW. Beyond the self: The role of co-regulation in medical students’ self-regulated learning. Med Educ. 2020;54:234–41. doi: 10.1111/medu.14018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sulla F, Monacis D, Limone P. A systematic review of the role of teachers’ support in promoting socially shared regulatory strategies for learning. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1208012. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1208012. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1208012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadwin AF, Jarvela S, Miller M. Self-regulated, co-regulated and socially-shared regulation in collaborative learning environments. In: Schunk DH, Greene JA, editors. Handbook of Self-Regulation, Learning, and Performance. New York, NY: Routledge; 2018. pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armson H, Lockyer JM, Zetkulic M, Könings KD, Sargeant J. Identifying coaching skills to improve feedback use in postgraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53:477–93. doi: 10.1111/medu.13818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolff M, Hammoud M, Carney M. Developing master adaptive learners: Implementation of a coaching program in graduate medical education. West J Emerg Med. 2023;24:71–5. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2022.12.57636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]