Abstract

Avirulent genes either directly or indirectly produce elicitors that are recognized by specific receptors of plant resistance genes, leading to the induction of host defense responses such as hypersensitive reaction (HR). HR is characterized by the development of a necrotic lesion at the site of infection which results in confinement of the invader to this area. Artificial chimeras and mutants of cymbidium ringspot (CymRSV) and the pepper isolate of tomato bushy stunt (TBSV-P) tombusviruses were used to determine viral factors involved in the HR resistance phenotype of Datura stramonium upon infection with CymRSV. A series of constructs carrying deletions and frameshifts of the CymRSV coat protein (CP) undoubtedly clarified that an 860-nucleotide (nt)-long RNA sequence in the CymRSV CP coding region (between nt 2666 and 3526) is the elicitor of a very rapid HR-like response of D. stramonium which limits the virus spread. This finding provides the first evidence that an untranslatable RNA can trigger an HR-like resistance response in virus-infected plants. The effectiveness of the resistance response might indicate that other nonhost resistance could also be due to RNA-mediated HR. It is an appealing explanation that RNA-mediated HR has evolved as an alternative defense strategy against RNA viruses.

Successful infection of plants by viral pathogens requires a series of compatible interactions between the host plant and the viral invader. Virus-host interactions such as replication of the virus genome at the single-cell level, cell-to-cell movement through plasmodesmata, and long-distance translocation in vascular tissue are required for the virus to successfully invade the host plant and cause disease (6, 7). A resistant or immune response can be caused by a passive mechanism when essential host components are missing (13). This kind of incompatible reaction could be due to the inability of a virus to associate with host-specific proteins for replication (17, 23) or movement (30, 37). Plants have also developed the ability to recognize and resist many invading pathogens by inducing a set of defense responses. These resistant responses, such as hypersensitive cell death (12), systemic acquired resistance (36, 44), or posttranscriptional gene silencing (PTGS) (33), can prevent the virus infection.

A hypersensitive response (HR) is characterized by the development of a necrotic lesion at the site of infection which results in confinement of the invader to this area. It is induced by a direct or indirect interaction between the product of the host plant R gene and the matching avirulence product of the corresponding pathogen. Different virus proteins, including RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (15, 16, 24, 28, 32), movement protein (29, 48, 49), and the coat protein (CP) (2, 3, 14, 46), have been identified as avirulence determinants. In addition to proteins, polysaccharides and other low-molecular-weight compounds have also been shown to act as specific elicitors in different nonviral host-pathogen systems (22).

Avirulence determinants can be responsible for host specificity of viruses, and they are often identified by genomic exchanges between related viruses having different host ranges and symptoms. The availability of infectious cDNA clones of different well-characterized tombusviruses having altered host ranges offers an excellent experimental system to recognize host specificity determinants.

The genome of a tombusvirus is a linear, single-stranded monopartite RNA molecule of mRNA polarity. The 4.7-kb-long genomic RNA acts as mRNA for the translation of a 33-kDa protein (p33, from open reading frame1 [ORF1]) and a readthrough product of a 92-kDa protein (p92, from ORF2). It was previously demonstrated that both of them are required for replication (11, 25, 31, 43). The 41-kDa CP is synthesized from the 2.1-kb subgenomic RNA 1 (sg1) (35), and two small nested ORFs (ORF4 and ORF5) coding for a 22-kDa (p22) and a 19-kDa (p19) protein are translated from the 0.9-kb subgenomic RNA 2 (sg2) (35). The p22 protein is required for cell-to-cell movement (11, 34, 40), and it also has a role in symptom development on certain hosts (41). p19 plays a crucial role in necrotic symptoms (4, 11, 34, 41) and participates in virus spread in a host-specific manner (42). Furthermore, p19 is able to suppress the virus-induced PTGS in Nicotiana benthamiana (47).

The aim of the present study was to determine virus-encoded host specificity determinants of tombusviruses. We used chimeras of previously described biologically active cDNA clones of cymbidium ringspot virus (CymRSV) (11) and tomato bushy stunt virus pepper strain (TBSV-P) (19). Although the genomic RNAs of the two viruses have very similar primary structures and genome organizations, there are significant differences in their host ranges. TBSV-P readily infects Capsicum annum and Datura stramononium plants systemically, while CymRSV is not able to infect these plants. Here we report that a stretch of 860 nucleotides (nt) of the RNA sequence from the CymRSV CP coding region is responsible for the HR-like resistance of D. stramonium plants against CymRSV. Furthermore, evidence is provided that the elicitor of the HR-like response resides in this 860-nt-long RNA sequence itself and not in the encoded protein. To our knowledge, this is the first report which shows that an RNA itself can act as an avirulence determinant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

DNA manipulations and cloning were carried out using standard molecular biology techniques (38) unless otherwise described.

Plasmids containing complete cDNA copies of CymRSV (11) and TBSV-P (19) were used to construct TBSV-P–CymRSV chimeras L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, L6, L7, L8, L9, and L10 as previously described (19) by using the following common restriction sites: StuI, NheI, PflMI, and SmaI. Plasmids TBSV-PΔCP, L1ΔCP, L4ΔCP, L6ΔCP, L8ΔCP, and L9ΔCP were constructed by digesting them with restriction enzymes NotI (position 2725) and KpnI (position 3524), followed by treatment with T4 DNA polymerase to generate blunt-end termini and then self ligation. Mutant LT/GNB was produced by replacing the last 2,191 nt of the L5 chimera with the last 2,191 nt of TBSV-P using BanII and SacI sites in L5 and TBSV-P. Reciprocal mutant LG/TNB was constructed by replacing the last 2,191 nt of the L8 chimera with the last 2,148 nt of CymRSV. Plasmid L11 was constructed by replacing the first 2,474 nt of the LG/TNB chimera with the first 2,480 nt of TBSV-P using ClaI and NheI sites of LG/TNB and TBSV-P. Reciprocal mutant L12 was constructed by replacing the first 2,480 nt of LT/GNB with the first 2,474 nt of CymRSV. Plasmids G11ΔSacII/9 and G11ΔSacII/11 were constructed by digesting G11 with restriction enzyme SacII (position 3626), followed by Bal 31 (Promega) treatment at 30°C for 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 min and religation with T4 DNA ligase. The resulting clones were selected by digestion with restriction enzymes and sequencing. For construction of G11ΔApaBglII and L5ΔApaBglII, plasmids G11 and L5 were digested with ApaI (position 3352) and BglII (position 3526) followed by T4 DNA polymerase treatment and ligation. Plasmid G11ΔAbglII was constructed previously (11) and L5ΔAbglII was generated by deletion of the AvaI-BglII fragment.

Plasmids G11FsCP and L5FsCP were constructed by digesting G11 and L5 with restriction enzyme AvaI (position 2666), followed by Klenow treatment and ligation, respectively. The resulting frameshift mutant clones were selected by digestion with AvaI and sequencing. The insertion of 4 bases into the AvaI site introduced a frameshift mutation into the CymRSV CP, which resulted in the premature termination of the CP. For construction of G11ΔAvaI, plasmid G11 was digested with restriction enzyme AvaI (position 2666), followed by mung bean nuclease treatment and ligation. The resulting frameshift mutant clone was selected by digestion with AvaI and sequencing. Sequencing revealed an accidentally introduced 5-nt deletion at the AvaI site. Plasmid L5ΔAvaI was generated by digestion of L5ΔAbglII with NheI (position 2474) and PflMI (position 3806), and the NheI-to-PflMI fragment from the G11ΔAval plasmid was used to replace the corresponding fragment of L5. A recombinant plasmid with the appropriate insert was selected. The deletions of 5 nt at the AvaI site of the G11ΔAvaI and L5ΔAvaI chimeras introduced frameshift mutations which resulted in premature termination of the CymRSV CP.

For constructing TBSV-AvaBg, TBSV-AvApa, and TBSV-ApaBg, plasmid TBSV-P was digested with NotI (position 2725) and SalI (position 3670), followed by Klenow and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) treatment, to produce a cloning vector. To generate TBSV-AvaBg, the filled-in AvaI (position 2666)-to-BglII (position 3526) fragment of G11 was inserted into the TBSV-P/NotI-SalI Klenow- and CIAP-treated vector. For construction of the TBSV-AvApa plasmid, the blunt-ended AvaI (position 2666)-to-ApaI (position 3352) fragment of G11 was inserted into the TBSV-P/NotI-SalI Klenow- and CIAP-treated vector. An additional construct, TBSV-ApaBg, was made using the blunt-ended ApaI (position 3352)-to-BglII (position 3526) fragment of G11 inserting into the TBSV-P/NotI-SalI Klenow- and CIAP-treated vector. Recombinant plasmids with the appropriate insert in the right orientation were selected.

DNA sequencing.

Plasmid DNAs were purified as previously described (18). DNA was sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method (39) using T7 DNA polymerase (Sequenase; U.S. Biochemicals).

In vitro transcription and inoculation into plants.

Plasmids G11, TBSV-P, and their derivatives were linearized by SmaI, and the RNA transcriptions were performed as previously described (11). For inoculation, the appropriate synthetic transcripts were mixed, and then the RNA was diluted with an equal volume of inoculation buffer (20) and applied to three leaves (15 μl/leaf) of N. benthamiana plants with a sterile glass spatula. D. stramonium plants were inoculated with the plant sap of infected leaves of N. benthamiana.

RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA from leaf tissue was isolated essentially according to the method of White and Kaper (50), with some modifications (11). Northern blot analysis was performed as follows. RNA samples were denatured with formamide and formaldehyde, electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gels, and transferred to nylon membranes (38). The following DNA fragments were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by random priming following the manufacturer's instructions (Prime-a-Gene kit; Promega): the PflMI-SmaI fragment of TBSV-P, corresponding to nt 3850 to 4776 of the TBSV-P genome, and the PflMI-SmaI fragment of G11, corresponding to nt 3806 to 4733 of the CymRSV genome. The two fragments were labeled separately and were mixed prior to use according to their specific activity.

In situ hybridization.

The press blot of inoculated leaves was carried out according to the method of Szilassy et al. (45). In brief, inoculated leaves were removed, and the lower side was abraded with Celite using a brush. The leaves were rinsed in water and were placed onto a Hybond N membrane (Amersham) with the abraded side down. The membrane was floated on W5 solution (125 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 154 mM NaCl, 5.5 mM glucose, 10.7 mM KCl) containing 0.7% cellulase (Onozuka R-10) and 0.25% macerozyme (R-10) and incubated in the dark overnight at room temperature. The membrane, together with the leaves, was removed and roller pressed between Whatman 3MM papers. Leaf remains were removed by rinsing the membrane with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and the membrane was dried and UV cross-linked according to the manufacturer's instructions. The presence of viral RNA was detected with randomly primed, 32P-labeled probes synthesized from the nt 3806-to-4733 PflMI-SmaI insert of CymRSV.

RESULTS

Symptoms and replication of CymRSV and TBSV-P on C. annum and D. stramonium plants.

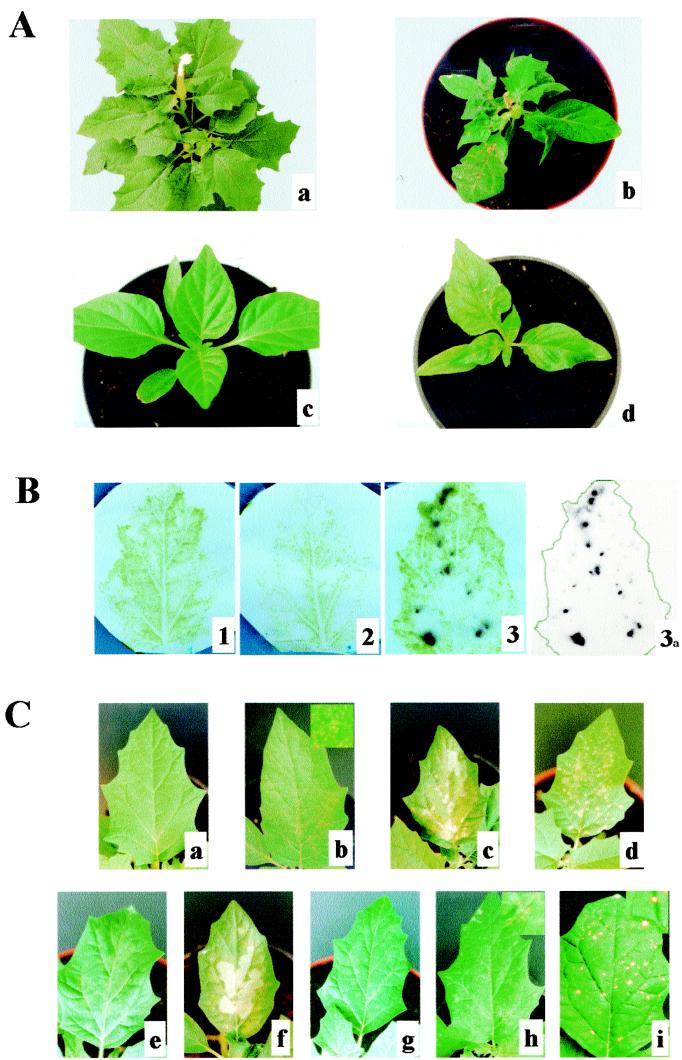

TBSV-P and CymRSV were used to infect C. annum and D. stramonium plants. TBSV-P-infected C. annum plants reacted with characteristic chlorotic lesions followed by the appearance of systemic symptoms, which consisted of a yellow and dark green mosaic pattern (Fig. 1A, panel d). The TBSV-P-infected D. stramonium plants displayed expanded necrotic lesions on the inoculated leaves (Fig. 1C, panel c) followed by systemic necrotic spots and twisting of the top leaves (Fig. 1A, panel b). However, CymRSV was not able to systemically infect either C. annum or D. stramonium plants (Fig. 1A, panels a and c), and the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium showed a typical HR-like necrotic response (very small, needle prick-sized necrotic lesions) at 3 days postinoculation (dpi) (Fig. 1C, panel b). This result suggested that the observed resistance against CymRSV infection is due to a very fast HR and that as a consequence of the HR-like necrotic local lesions the virus was not able to spread from the initially infected cells. To test this suggestion, press blot analysis was done on CymRSV-inoculated D. stramonium leaves showing HR-like necrotic lesions. Virus-specific RNAs could not be detected on leaves blotted at 1 hour postinoculation. In contrast, when leaves were blotted at 3 dpi, those containing HR-like necrotic local lesions reacted with the CymRSV-specific probe (Fig. 1B), indicating virus accumulation in the initially infected cells. Attempts to detect CymRSV RNAs in the total RNA extracts of these leaves at 3 and 7 dpi using Northern analysis were unsuccessful. The lack of detection was likely due to the fact that only a few cells could be infected with CymRSV (Fig. 1B). However, the same RNA extracts were able to induce infection on N. benthamiana plants. These results suggested that CymRSV was able to replicate in the primary infected cells but that the plant quickly confined the virus by an HR-like response.

FIG. 1.

Symptoms and virus replication in C. annum and D. stramonium plants inoculated with CymRSV, TBSV-P, and CymRSV–TBSV-P chimeras. (A) Symptoms on D. stramonium plants 3 weeks after inoculation with CymRSV (a) and TBSV-P (b) and on C. annum plants 2 weeks after inoculation with CymRSV (c) and TBSV-P (d). (B) Press blot analysis of D. stramonium leaves inoculated with either mock inoculum (1) or CymRSV (2 and 3). Inoculated leaves were harvested either at 1 h postinfection (2) or at 3 dpi (1 and 3). Filters were hybridized with radiolabeled, CymRSV-specific probes. The photographs were prepared by overlaying the filters with the appropriate autoradiograms showing the sites of infected cells. Panel 3a shows the autoradiogram of filter 3 without the filter in order to make faint signals visible. The green line indicates the edge of the inoculated leaf. (C) Symptoms induced on the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium by mock inoculum (a), CymRSV (b), TBSV-P (c), L6 (d), L8Δ41 (e), L12 (f), G11ΔAbglII (g), G11ΔAval (h), and TBSV-AvaBg (i). Insets in panels b, h, and i are enlarged portions of the leaves shown.

The CP gene of tombusviruses determines the host specificity.

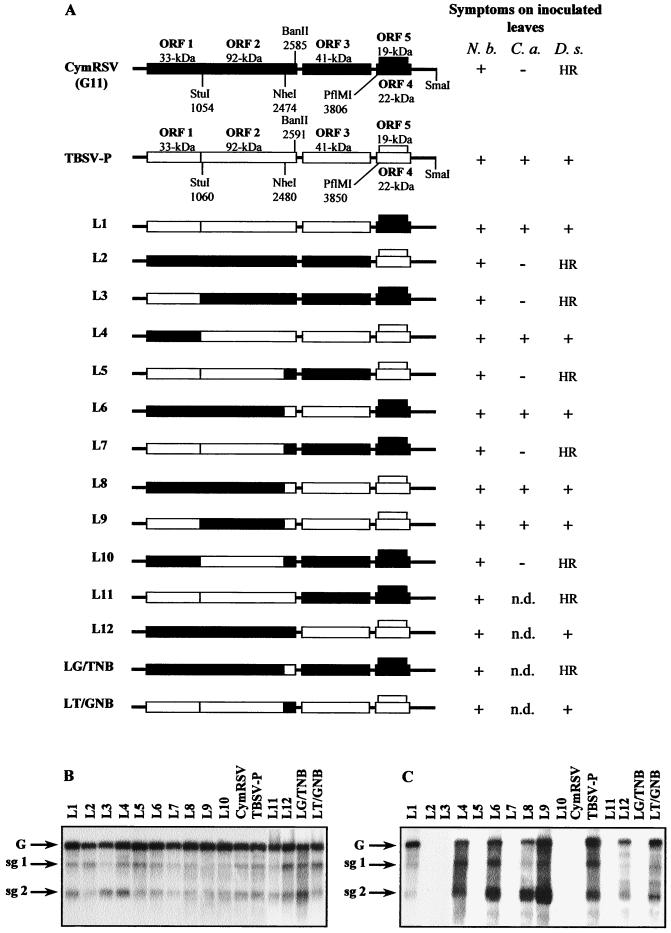

To localize the viral genes responsible for the host specificity, hybrid viruses were constructed by exchanging the corresponding genomic regions between TBSV-P and CymRSV (Fig. 2A). The viability of hybrid viruses was tested by inoculating them on N. benthamiana. All chimeras were able to infect N. benthamiana plants systemically and caused similar symptoms and accumulated to the same level as the parental viruses did (Fig. 2B). These results confirmed that all chimeras retained basic competence for infection. In order to identify those viral factors which are responsible for host specificity, selective hosts (C. annum and D. stramonium) were inoculated with plant sap prepared from N. benthamiana plants infected with corresponding hybrids. Virus RNA accumulation and symptom development were analyzed on the inoculated leaves of C. annum and D. stramonium. The results obtained showed that replacement of the two 3′ proximal nested genes (constructs L1 and L2) and the ORF1 (constructs L3 and L4) did not modify the symptoms of wild-type (wt) CymRSV and TBSV-P infections (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the exchange of sequence between StuI and NheI sites in ORF2 (constructs L9 and L10) did not alter the symptoms of wt virus infections. However, modifications which affected the CP-encoding sequence (ORF3) (constructs L5 and L6) resulted in a significant alteration in the symptoms of infected D. stramonium (Fig. 2A). Northern blot analysis revealed that only those constructs (L1, L4, L6, L8, and L9) that carry the CP gene and the last 143 nt of the replicase gene of TBSV-P were able to infect D. stramonium plants (Fig. 2A and C). Some variation in the accumulation of viral RNA was observed, but these differences were likely due to sampling effects and did not result in alterations in symptoms. Constructs (L2, L3, L5, L7, and L10) containing the corresponding region (the CP gene and the last 143 nt of the replicase gene) of CymRSV induced HR in D. stramonium (Fig. 2A and C). The symptoms of infectious constructs on D. stramonium (e.g., L6 in Fig. 1C, panel d) and C. annum (not shown) were similar to those of TBSV-P (Fig. 1C, panel c), causing expanding chlorotic and necrotic lesions. This observation may suggest that similar viral factors are involved in the host specificity determination on C. annum and D. stramonium, although C. annum did not exhibit HR-like necrotic lesions upon CymRSV infection. In this study C. annum was not used for further investigation. The obtained results suggested that the CP and/or the last 143 nt of the replicase gene of TBSV-P are required to infect D. stramonium and C. annum plants, and alternatively, that the CymRSV CP and/or the last 143 nt of the replicase gene represent an avirulence factor to these hosts.

FIG. 2.

Viral symptoms and RNA accumulation in plants inoculated with CymRSV, TBSV-P, and CymRSV–TBSV-P chimeras. (A) Schematic representation and induced symptoms of the CymRSV–TBSV-P chimeras. The organizations of CymRSV and TBSV-P genomic RNAs are shown above with the ORFs (boxes) and the approximate molecular masses of the encoded proteins. The common restriction endonuclease sites used for constructing chimeras are indicated. The designations of the chimeras are on the left. Symptoms of parental and hybrid viruses are indicated at the right. Three plants were inoculated with each inoculum, and the experiment was repeated three times. Symbols: +, efficient virus infection with the typical symptoms detailed in the text; −, no symptoms appeared for up to 4 weeks; HR, small necrotic local lesions which limited the virus spread; n.d., not determined. N. b., N. benthamiana; C. a., C. annum; D. s., D. stramonium. The accumulation of hybrid viral RNAs in N. benthamiana (B) and D. stramonium (C) plants is shown. Total RNAs were extracted at 6 to 8 dpi from systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana and inoculated leaves of D. stramonium. Northern blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA mixed probes of the 3′-terminal 1,000 nt of CymRSV and TBSV-P RNAs. G, genomic RNA; sg1, subgenomic RNA 1; sg2, subgenomic RNA 2.

To test whether the last 143 nt of the replicase gene are functionally relevant to host specificity, mutants were constructed in which all parts of the replicase gene derived from CymRSV except the downstream sequences, which were from TBSV-P, and vice versa (Fig. 2A, L11 and L12). Two other hybrids (LG/TNB and LT/GNB) were also constructed, exchanging the last 143 nt of the replicase genes of CymRSV and TBSV-P (Fig. 2A). The L11 and LG/TNB chimeras were not able to infect D. stramonium plants, while L12 and LT/GNB induced very similar symptoms (data not shown) and accumulated to the same level as the wt TBSV-P did (Fig. 2C). Northern blot analysis of RNAs extracted from inoculated leaves of D. stramonium again confirmed that only those chimeras which contained the CP gene of TBSV-P replicated at detectable levels in this host (Fig. 2C). Thus, the last 143 nt of the replicase gene of TBSV-P are not host specificity determinants, and it is assumed that the active avirulence determinants reside in either the encoding RNA of the CP or the CP itself.

CymRSV CP or the encoding RNA sequence acts as an avirulence factor eliciting an HR-like resistance response in D. stramonium.

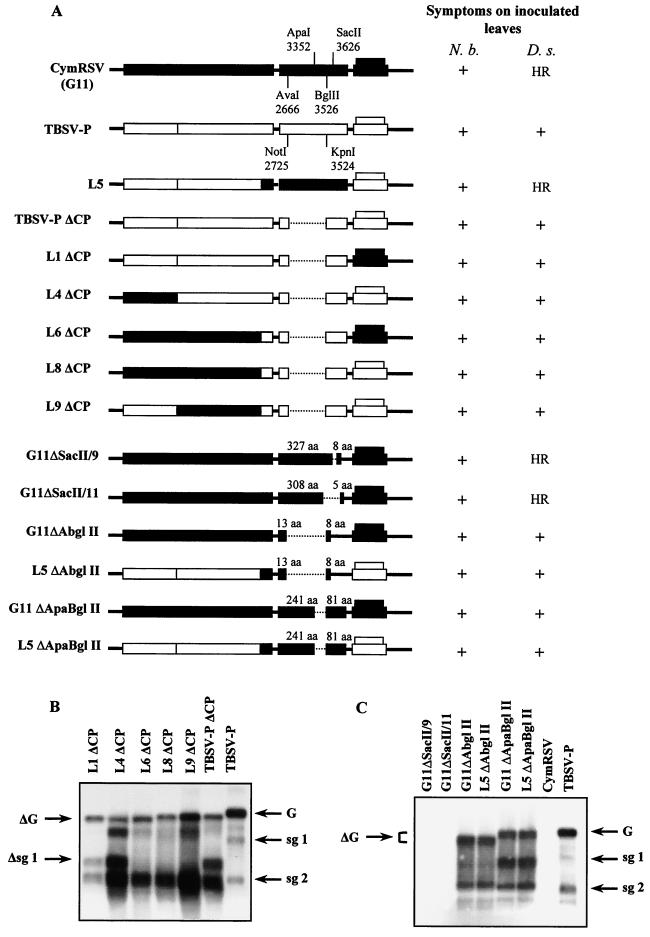

The inability of CymRSV to infect D. stramonium plants can be explained in two different ways: (i) the TBSV-P CP gene is required for successful infection or (ii) the CymRSV CP gene acts as an avirulence factor eliciting an HR-like resistance response. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we prepared TBSV-PΔCP, L1ΔCP, L4ΔCP, L6ΔCP, L8ΔCP, and L9ΔCP deletion mutants (Fig. 3A) and tested them on both N. benthamiana and D. stramonium plants. As was expected from previous observations (10, 11), all of the CP deletion mutants were able to infect N. benthamiana, and they accumulated to the same level as (data not shown) and caused symptoms similar to those previously reported for a CymRSV CP deletion mutant (G11ΔAbglII) (10, 11). Surprisingly, all of the TBSV-P CP deletion mutants were also able to infect D. stramonium plants (Fig. 3B) and induced expanding light chlorotic lesions on the inoculated leaves (Fig. 1C, panel e) which were milder than those induced by TBSV-PΔCP (data not shown). These results clearly indicate that the CP of TBSV-P was not required for the infection of D. stramonium and support the alternative hypothesis that CymRSV CP inhibits the virus infection on D. stramonium by eliciting an incompatible HR response.

FIG. 3.

Symptoms and RNA accumulation in plants infected with CP deletion mutants of TBSV-P, CymRSV, and CymRSV–TBSV-P chimeras. (A) Diagrams and induced symptoms of the CP deletion mutant chimeras. The restriction endonuclease sites used for constructing the CP deletion mutant chimeras are indicated. Symptoms of the parental and CP deletion mutant chimeras are indicated at the right. Symptoms were evaluated at 6 to 8 dpi. Three plants were inoculated with each inoculum, and the experiment was repeated three times. Dotted lines indicate the deleted sequences, and solid lines represent presumed untranslated sequences. Numbers shown above the CP of CymRSV indicate the predicted length of the translated polypeptides. Other symbols are defined in the legend to Fig. 2A. (B) Accumulation of viral RNAs in the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium plants inoculated with the CP deletion mutants of TBSV-P and the indicated chimeras, respectively. Total RNAs were extracted at 6 to 8 dpi and subsequently subjected to Northern analysis. (C) Accumulation of CymRSV CP deletion mutant viral RNAs in D. stramonium plants. Total RNAs were extracted at 6 to 8 dpi from inoculated leaves of D. stramonium, and Northern analysis was performed using the same DNA probes as defined in the legend to Fig. 2B. ΔG and Δsg1 indicate the positions of the genomic RNA and the subgenomic RNA 1 of the CP deletion mutant chimeras, respectively. Other symbols are described in the legend to Fig. 2B.

In order to test this hypothesis, new CP deletion mutants of CymRSV and the L5 hybrid were prepared (Fig. 3A). All of the CP deletion mutants were able to infect N. benthamiana similarly to previously reported CP deletion mutants of tombusviruses (data not shown; 10, 11, 42). Inoculation of D. stramonium plants with these mutants and Northern blot analysis of RNAs extracted from the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium revealed that only those mutants in which the central region of CymRSV CP was deleted (G11ΔApaBglII, L5ΔApaBglII, G11ΔAbglII, and L5ΔAbglII) were able to replicate and accumulate efficiently (Fig. 3C). These mutants induced expanding light chlorotic spots (3 to 4 mm in diameter) on the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium plants (Fig. 1C, panel g). CP C-terminal deletion mutants G11ΔSacII/9 (64-nt deletion between positions 3611 and 3675) and G11ΔSacII/11 (200-nt deletion between positions 3503 and 3703) (Fig. 3A) were not detectable by Northern blot analysis in the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium (Fig. 3C) and caused HR-like necrotic local lesions similar to those of the wt CymRSV (Fig. 1C, panel b). These observations strongly suggest that the N-terminal 308 amino acids (aa) (or the coding sequence) of CymRSV CP are still sufficient to induce small HR-like necrotic lesions on the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium and limit virus infection. However, shorter sequences from the N-terminal region of the CymRSV CP (G11ΔApaBglII) or further deletion in this region (G11ΔAbglII) was not sufficient to induce the resistant response, and the mutant virus became infectious, inducing expanding light chlorotic spots (e.g., Fig. 1C, panel g).

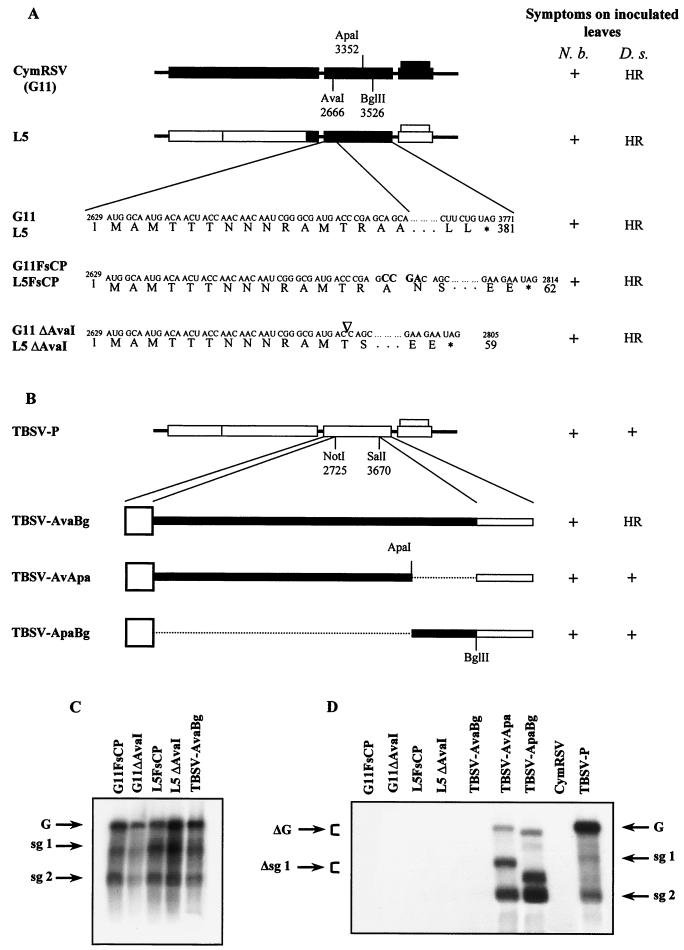

A stretch of 860 nt of RNA in CymRSV CP coding sequence acts as an avirulence factor.

Further studies were conducted to determine whether the CymRSV CP or the encoding RNA is the elicitor of the HR-like resistance response of D. stramonium. CymRSV and L5 CP frameshift mutants were prepared (Fig. 4A). The CP frameshift mutant chimeras (G11FsCP and L5FsCP) contain a 4-nt insertion at the AvaI (nt 2666) restriction enzyme site. Theoretically, these mutants are able to produce a 61-aa peptide in which the first 15 aa are identical to those of the CymRSV CP. In addition, G11ΔAvaI and L5ΔAvaI mutants were produced by deleting 5 nt at the same AvaI position, and they may produce a 58-aa peptide (their first 13 aa are identical to those of the CP). In the inoculation experiments, all of the CymRSV CP frameshift mutants (G11FsCP, L5FsCP, G11ΔAvaI, and L5ΔAvaI) were able to infect N. benthamiana plants, and they accumulated to the same level (Fig. 4C) as the ΔCP mutants of wt CymRSV did and caused similar symptoms (10). The regions containing the mutations were reverse transcriptase-PCR amplified and sequenced. The results of sequence analysis confirmed that the progeny of all frameshift mutants were identical with synthetic transcripts used to inoculate N. benthamiana, and the coding region of the CymRSV CP was not restored. D. stramonium plants were inoculated with saps prepared from G11FsCP-, L5FsCP-, G11ΔAvaI-, and L5ΔAvaI-infected N. benthamiana. Surprisingly, none of these CP frameshift mutant viruses were able to infect D. stramonium plants; instead, they elicited a typical HR-like resistance response (Fig. 1C, panel h), as the wt CymRSV did. Northern blot analysis confirmed that the CymRSV CP frameshift mutants were not able to accumulate in D. stramonium (Fig. 4D). This finding strongly suggests that the RNA in the CymRSV CP coding region downstream of the AvaI site at position 2666 acts as an avirulence factor on resistant D. stramonium plants. We analyzed further whether this RNA region can elicit the HR-like reaction in a different genetic background. The TBSV-P CP coding sequence between the NotI (nt 2725) and SalI (nt 3670) restriction enzyme sites was replaced by three different parts of the CymRSV CP coding sequence (Fig. 4B). These were AvaI-BglII (860-nt long), AvaI-ApaI (686-nt long), and ApaI-BglII (174-nt long) fragments of CymRSV CP. The resulting chimeras are able to produce only short peptides (24 aa) instead of functional CP. It was shown above (Fig. 3) that the deletion of AvaI-BglII or ApaI-BglII fragments of CymRSV CP abolished the elicitor activity of CymRSV CP on D. stramonium plants. Therefore, it was expected that the insertion of the AvaI-BglII CymRSV CP fragment or part of it into the corresponding position of TBSV-P would result in an HR-like resistance response in D. stramonium. All chimeras (TBSV-AvaBg, -AvApa, and -ApaBg) were able to infect N. benthamiana plants and accumulated to levels similar to those of the TBSV-P ΔCP mutant (data not shown). In addition, the regions of interest of the progeny of chimeras (TBSV-AvaBg, -AvApa, and -ApaBg) were reverse transcriptase-PCR amplified and sequenced. The results of sequence analysis confirmed that the progeny of all chimeras retained the original sequences. Northern blot analysis revealed that constructs carrying the AvaI-ApaI (TBSV-AvApa) or ApaI-BglII (TBSV-ApaBg) fragment of CymRSV CP accumulated efficiently in the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium (Fig. 4D). These chimeras also induced light chlorotic spots on the inoculated leaves (data not shown). In contrast, the TBSV-AvaBg chimera carrying the CymRSV CP AvaI-BglII fragment was not detectable by Northern analysis (Fig. 4D). It induced an HR-like local necrotic response, and thus the virus infection was confined. However, there was a little delay in the virus localization, so the necrotic lesions became a little larger than with CymRSV infection (Fig. 1C, panel i versus panel b). Sequence comparison of the two viruses using the Bestfit program of the Wisconsin package, version 9.1, Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis., revealed that within this 860-nt-long RNA region there is only 55% similarity between CymRSV and TBSV-P. This is the least conserved region in the genomic RNAs compared to the 81% similarity of the rest of the sequences. Despite the relatively low similarity of these 860-nt-long RNA regions, we did not find significant differences between the predicted secondary structure of the two RNA stretches. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the 860-nt-long RNA sequence located between the AvaI and BglII sites in the CymRSV CP is an avirulence factor. Moreover, we provide evidence that this RNA segment is sufficient and also required to elicit an HR-like resistance response in D. stramonium.

FIG. 4.

Viral symptoms and RNA accumulation in plants inoculated with the CP frameshift mutants of CymRSV, L5, and TBSV-P chimeras carrying different parts of the coding sequence of the CymRSV CP. (A) Schematic diagrams and induced symptoms of the frameshift mutants. Restriction enzyme sites used for constructing chimeras are indicated. The inserted nucleotides at the AvaI site are shown by boldface letters. The positions of the five deleted nucleotides (CCGAG) are indicated by the symbol ▿. The developed symptoms of the inoculated plants are shown on the right. Three plants were inoculated with each inoculum, and the experiment was repeated three times. The nucleotide (above) and amino acid (below) sequences of the region of interest of the CymRSV CP in the G11 and L5 genomes are shown. Numbers at the starts and ends of the sequences indicate the nucleotide and amino acid positions in the CymRSV genome and the CP sequence, respectively. Dots indicate the nonmodified part of the sequences. Asterisks indicate the termini of wt and mutant CymRSV CP. (B) Diagrams of the TBSV-P genome carrying different parts of the CymRSV CP. The developed symptoms of the inoculated plants are shown at the right. The large open boxes show the short 24-aa-long coding region of the N-terminal part of the TBSV-P CP. Thick dark lines indicate the CymRSV CP, and thin open boxes show the out-of-frame sequences of TBSV-P. Dotted lines indicate the deleted sequences. Three plants were inoculated with each inoculum, and the experiment was repeated three times. (C) The accumulation of viral RNAs in the inoculated leaves of N. benthamiana plants infected with chimeras indicated above the lanes. Total RNAs were extracted at 6 to 8 dpi and subsequently subjected to Northern analysis. The DNA probes used and other symbols are defined in the legend to Fig. 2. (D) Northern analysis of total RNAs extracted at 6 to 8 dpi from the inoculated leaves of D. stramonium plants infected with the chimeras indicated above the lanes. The DNA probes used and other symbols are defined in the legend to Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described the use of CymRSV–TBSV-P chimeras to determine viral factors involved in the determination of host specificity of tombusviruses. We have shown here that an 860-nt-long RNA sequence of CymRSV is the elicitor of a very rapid HR-like response of D. stramonium. This finding provides the first example that an untranslatable RNA can trigger an HR-like resistance response in virus-infected plants. This finding represents a new feature of molecular strategies employed by plants for defense against pathogens.

Mapping of avirulence factors of tombusviruses.

Mapping of host-range determinants of plant viruses by gene exchange and reverse genetics has the major advantage of the exchanged genomic sequences being put into a very similar background to the one they originated from. Foreign virus vectors (PVX or TMV) have also been used for the same purposes (41); however, the expression of a viral gene in a different genetic background may switch a virulent gene to an avirulent one (26). In addition, the compartmentalization of the studied viruses (5) and the use of viral expression vectors could modify the plant response. The facts that CymRSV and TBSV-P have a similar primary structure and the same genome organization and that they replicate in the same compartments (27, 35) offer an excellent opportunity to study viral avirulence factors. In addition, we found significant differences in the host ranges of CymRSV and TBSV-P. TBSV-P readily infects C. annum and D. stramonium plants systemically, while CymRSV is not able to infect these plants systemically. The results of press blot analysis clearly indicated that the failure of CymRSV to infect D. stramonium plants is not caused by its inability to replicate in this host. Most likely, the alterations caused by the replicating virus in the initially infected cells induced a very fast HR-like response, which arrested further spread of the virus. Therefore, the differences in the host ranges of the two tombusviruses were the consequence of different host responses of the plants infected with TBSV-P or CymRSV. It was shown by several studies that different virus proteins with different functions are able to elicit HR as an effective resistance response (8, 9). The tombusvirus proteins p22 and p19 have been shown to elicit HR-like necrotic responses in selected resistant plant species (41, 42). In contrast, the replacement of the nested coding regions of p19 and p22 has no effect on the differential response of C. annum and D. stramonium to TBSV-P and CymRSV (e.g., see symptoms of L5 and L7 or L6 and L8), confirming that different hosts can recognize different avirulence factors of the same pathogen (9). Similarly, the virus-encoded replicase subunits (p33 and p92) did not influence the host specificity (e.g., see symptoms of L11 and L12 on C. annum and D. stramonium).

Furthermore, the ΔCP mutant of TBSV-P and constructs L1ΔCP, L4ΔCP, L6ΔCP, L8ΔCP, and L9ΔCP were infectious on C. annum and D. stramonium, showing that the accumulation of the chimeras does not depend on the presence of the TBSV-P CP. These results suggest that the CymRSV CP or its coding region is responsible for the induction of HR-like local lesions that limit the virus spread. The CPs of tombusviruses do not contribute to cell-to-cell movement (35). So, it was unlikely that the failure of CymRSV (and chimeras carrying the CymRSV CP) to infect D. stramonium was due to the inability of the CymRSV CP to support the cell-to-cell movement. In fact, those constructs which contained the CymRSV CP with an 860-nt-long deletion (between nt 2666 and 3526) or a part of it (G11ΔAbglII, G11ΔApaBglII, L5ΔAbglII, and L5ΔApaBglII) were able to infect D. stramonium, but the chimeras carrying the coding sequence of the N-terminal 308 aa (between nt 2629 and 3611) of the CymRSV CP elicited the resistant response.

Frameshift mutants of the CymRSV and L5 CPs clearly showed that the resistance response observed on D. stramonium was induced by an 860-nt-long RNA sequence located in the CP ORF (between nt 2666 and 3526). The TBSV-AvaBg chimera containing this untranslatable 860-nt-long RNA stretch of the CymRSV CP undoubtedly clarified that this sequence is required and sufficient to induce the HR-like necrotic response, even in a different genetic background. To our knowledge, this is the first report which provides evidence that an RNA sequence and not the encoded protein product induces a very fast HR-like response which prevents virus invasion in the plant. The mechanism of how this RNA region affects the host-virus interaction and how it elicits the HR-like response of the plant remains to be established.

Can RNAs of molecular pathogens be recognized as avirulence factors?

Cellular organisms have evolved different strategies to recognize and combat molecular parasites. In eukaryotes, recognition of double-stranded (ds) replication intermediates of RNA viruses leads to the release of different defense reactions, including PTGS (1) and interferon-mediated responses (21). PTGS degrades in a sequence-specific manner all mRNAs homologous to the dsRNA. In vertebrates, dsRNA molecules trigger interferon-induced cellular antiviral responses which might lead to apoptosis. Importantly, dsRNAs are recognized independently from their sequences.

In contrast, we have found that the mRNA of an RNA virus can be recognized in a sequence-specific manner by resistant plants as an invader. An 860-nt-long untranslatable RNA sequence of the CymRSV CP was sufficient to elicit an HR-like response on D. stramonium, but the corresponding genome segment of another tombusvirus did not trigger this response. HR is often triggered by gene-for-gene resistance, when the R gene of the host recognizes a specific product, the avirulence factor of the pathogen. Viral proteins as avirulence determinants can trigger HR; however, this is the first report that an RNA region can be recognized as an avirulence factor. This is an unexpected finding, because the binding of the host receptor to the avirulence factor is very specific. For example, a single amino acid change could result in resistance breaking (9). Therefore, the degeneracy of the genetic code and the high mutation rate of RNA molecules would suggest that new resistance-breaking viruses can be selected soon, but this did not happen in the CymRSV-D. stramonium system. RNA structures are evolutionarily more conserved than primary structures, so we may speculate that a specific RNA structure formed in this HR elicitor region rather than the sequence itself can be identified by the receptor of resistant plants. However, preliminary data of computer analysis did not predict a special structure for this avirulence RNA.

Whether this specific, RNA-mediated HR is a frequently deployed defense strategy or is rarely utilized in nature cannot be predicted. However, the effectiveness of the HR-like response of D. stramonium against CymRSV might indicate that other nonhost resistance could also be due to RNA-mediated HR. It is an appealing explanation that RNA-mediated HR has evolved as an alternative defense strategy against RNA viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Fernando Garcia-Arenaland and Dániel Silhavy for very valuable suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript.

This research was supported by grants from the Hungarian OTKA (T 31929) and the Ministry of Education (FKFP0442/1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bass B L. Double-stranded RNA as a template for gene silencing. Cell. 2000;101:235–238. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)71133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendahmane A, Kohn B A, Dedi C, Baulcombe D C. The coat protein of potato virus X is a strain-specific elicitor of Rx1-mediated virus resistance in potato. Plant J. 1995;8:933–941. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.8060933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berzal-Herranz A, de la Cruz A, Tenllado F, Díaz-Ruíz J R, López L, Sanz A I, Vaquero C, Serra M T, García-Luque I. The capsicum L3 gene-mediated resistance against the tobamoviruses is elicited by the coat protein. Virology. 1995;209:498–505. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgyán J, Hornyik C, Szittya G, Silhavy D, Bisztray G. The ORF1 products of tombusviruses play a crucial role in lethal necrosis of virus-infected plants. J Virol. 2000;74:10873–10881. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.10873-10881.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgyán J, Rubino L, Russo M. The 5′-terminal region of a tombusvirus genome determines the origin of multivesicular bodies. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1967–1974. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrington J C, Whitham S A. Viral invasion and host defense: strategies and counter-strategies. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:336–341. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrington J C, Kasschau K D, Mahajan S K, Shaad M C. Cell-to-cell and long distance movement of viruses in plants. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1669–1681. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu M, Park J-W, Scholthof H B. Separate regions on the tomato bushy stunt virus p22 protein mediate cell-to-cell movement versus elicitation of effective resistance responses. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999;12:285–292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culver J. Viral avirulence genes. In: Stacey G, Keen N T, editors. Plant-microbe interactions. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1996. pp. 196–219. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalmay T, Rubino L, Burgyán J, Russo M. Replication and movement of a coat protein mutant of cymbidium ringspot tombusvirus. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1992;5:379–383. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-5-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalmay T, Rubino L, Burgyán J, Kollár Á, Russo M. Functional analysis of cymbidium ringspot virus genome. Virology. 1993;194:697–704. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dangl J L, Dietrich R A, Richberg M H. Death don't have no mercy: cell death programs in plant-microbe interactions. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1793–1807. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson W O, Hilf M E. Host-range determinants of plant viruses. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:527–555. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Cruz A, López L, Tenllado F, Díaz-Ruíz J R, Sanz A I, Vaquero C, Serra M T, García-Luque I. The coat protein is required for the elicitation of the capsicum L2 gene-mediated resistance against the tobamoviruses. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:107–113. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson F L, Holzberg S, Calderon-Urrea A, Handley V, Axtell M, Corr C, Baker B. The helicase domain of the TMV replicase proteins induces the N-mediated defense response in tobacco. Plant J. 1999;18:67–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamamoto H, Watanabe Y, Kamada H, Okada Y. Amino acid changes in the putative replicase of tomato mosaic tobamovirus that overcome resistance in Tm-1 tomato. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:461–464. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-2-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamamoto H, Watanabe Y, Kamada H, Okada Y. A single amino acid substitution in the virus-encoded replicase of tomato mosaic tobamovirus alters host specificity. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:1015–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattori M, Sakaki Y. Dideoxy sequencing method using denatured plasmid templates. Anal Biochem. 1986;152:232–238. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havelda Z, Szittya G, Burgyán J. Characterization of the molecular mechanism of defective interfering RNA-mediated symptom attenuation in tombusvirus-infected plants. J Virol. 1998;72:6251–6256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6251-6256.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heaton L A, Carrington J C, Morris T J. Turnip crinkle virus infection from RNA synthesized in vitro. Virology. 1989;170:214–218. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman R J. Double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase mediates virus-induced apotosis: a new role for an old actor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11693–11695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keen N T. The molecular biology of disease resistance. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;19:109–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00015609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller K E, Johansen I E, Martin R R, Hampton R O. Potyvirus genome-linked protein (VPg) determines pea seed-borne mosaic virus pathotype-specific virulence in Pisum sativum. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:124–130. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim C H, Palukaitis P. The plant defense response to cucumbermosaic virus in cowpea is elicited by the viral polymerase gene and affects virus accumulation in single cells. EMBO J. 1997;16:4060–4068. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kollár Á, Burgyán J. Evidence that ORF 1 and 2 are the only virus encoded replicase genes of cymbidium ringspot tombusvirus. Virology. 1994;201:169–172. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H-W, Lucy A P, Guo H-S, Li W-X, Ji L-H, Wong S-M, Ding S-W. Strong host resistance targeted against a viral suppressor of the plant gene silencing defense mechanism. EMBO J. 1999;18:2683–2691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martelli G P, Gallitelli D, Russo M. Tombusviruses. In: Koenig R, editor. The plant viruses. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing; 1988. pp. 13–72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meshi T, Motoyoshi F, Adachi A, Watanabe Y, Takamatsu N, Okada Y. Two concomitant base substitutions in the putative replicase genes of tobacco mosaic virus confer the ability to overcome the effects of a tomato resistance gene, Tm-1. EMBO J. 1988;7:1575–1581. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meshi T, Motoyoshi F, Maeda T, Yoshiwoka S, Watanabe H, Okada Y. Mutations in the tobacco mosaic virus 30-kD protein gene overcome Tm-2 resistance in tomato. Plant Cell. 1989;1:515–522. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.5.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mise K, Allison R F, Janda M, Ahlquist P. Bromovirus movement protein genes play a crucial role in host specificity. J Virol. 1993;67:2815–2823. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2815-2823.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oster S K, Wu B, White A. Uncoupled expression of p33 and p92 permits amplification of tomato bushy stunt virus RNAs. J Virol. 1998;72:5845–5851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5845-5851.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padgett H S, Watanabe Y, Beachy R N. Identification of the TMV replicase sequence that activates the N gene-mediated hypersensitive response. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:709–715. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratcliff F G, MacFarlane S A, Baulcombe D C. Gene silencing without DNA: RNA-mediated cross-protection between viruses. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1207–1215. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rochon D M, Johnston J C. Infectious transcripts from cloned cucumber necrosis virus cDNA. Evidence for a bifunctional subgenomic mRNA. Virology. 1991;181:656–665. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90899-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo M, Burgyán J, Martelli P G. The molecular biology of Tombusviridae. Adv Virus Res. 1994;44:382–424. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryals J A, Neuenschwander U H, Willits M G, Molina A, Steiner H Y, Hunt M D. Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1809–1819. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryu K H, Kim C H, Palukaitis P. The coat protein of cucumber mosaic virus is a host range determinant for infection of maize. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scholthof H B, Morris T J, Jackson A O. The capsid protein gene of tomato bushy stunt virus is dispensable for systemic movement and can be replaced for localized expression of foreign genes. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholthof H B, Scholthof K-B G, Jackson A O. Identification of tomato bushy stunt virus host-specific symptom determinants by expression of individual genes from a potato virus X vector. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1157–1172. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholthof H B, Scholthof K-B G, Kikkert M, Jackson A O. Tomato bushy stunt virus spread is regulated by two nested genes that function in cell-to-cell movement and host-dependent systemic invasion. Virology. 1995;213:425–438. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scholthof K-B G, Scholthof H B, Jackson A O. The tomato bushy stunt virus replicase proteins are coordinately expressed and membrane associated. Virology. 1995;208:365–369. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sticher L, Mauch-Mani B, Metraux J P. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1997;35:235–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szilassy D, Salánki K, Balázs E. Stunting induced by cucumber mosaic cucumovirus-infected Nicotiana glutinosa is determined by a single amino acid residue in the coat protein. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999;12:1105–1113. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.12.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taraporewala Z F, Culver J N. Identification of an elicitor active site within the three-dimensional structure of the tobacco mosaic tobamovirus coat protein. Plant Cell. 1996;8:169–178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voinnet O, Pinto Y M, Baulcombe D C. Suppression of gene silencing: a general strategy used by diverse DNA and RNA viruses of plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14147–14152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weber H, Pfitzner A J. Tm-22 resistance in tomato requires recognition of the carboxy terminus of the movement protein of tomato mosaic virus. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:498–503. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber H, Schultze S, Pfitzner A J. Two amino acid substitutions in the tomato mosaic virus 30-kilodalton movement protein confer the ability to overcome the Tm-2(2) resistance gene in the tomato. J Virol. 1993;67:6432–6438. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6432-6438.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White J L, Kaper J M. A simple method for detection of viral satellite RNAs in small tissue samples. J Virol Methods. 1989;23:83–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(89)90122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]