Abstract

The tuning of glutamatergic transmission is an essential mechanism for neuronal communication. α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs) are ionotropic glutamate receptors that mediate fast synaptic transmission. The phosphorylation states of specific serine residues on the GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits are considered critical post-translational modifications that regulate AMPAR activity and subcellular trafficking. While behavioral stress, via stress hormones, exerts specific alterations on such glutamatergic processes, there have been conflicting data concerning the influence of stress on AMPAR phosphorylation in different brain regions, and the post-stress signaling mechanisms mediating these processes are not well delineated. Here, we examined the dynamics of phosphorylation at three AMPAR serine residues (ser831-GluA1, ser845-GluA1, and ser880-GluA2) in four brain regions [amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), dorsal hippocampus, and ventral hippocampus] of the rat during the hour following behavioral stress. We also tested the impact of post-stress corticosteroid receptor blockade on AMPAR phosphorylation. Both GluA1 subunit residues exhibited elevated phosphorylation after stress, yet post-stress administration of corticosteroid receptor antagonists curtailed these effects only at ser831-GluA1. In contrast, ser880-GluA2 displayed a time-dependent tendency for early decreased phosphorylation (that was selectively augmented by mifepristone treatment in the amygdala and mPFC of stressed animals) followed by increased phosphorylation later on. These findings show that the in vivo regulation of AMPAR phosphorylation after stress is a dynamic and subunit-specific process, and they provide support for the hypothesis that corticosteroid receptors have an ongoing role in the regulation of ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation during the post-stress interval.

Keywords: Stress, AMPA, Phosphorylation, Spironolactone, Amygdala, Prefrontal cortex

Introduction

By mediating fast glutamatergic neuronal transmission at excitatory synapses, AMPARs maintain a pervasive role in brain function. These receptors are heteromeric complexes comprised from varying combinations of GluA1, GluA2, GluA3, and GluA4 subunits, which have different intracellular cytoplasmic tails containing several protein-binding domains and phosphorylation sites important for regulating their function (Shepherd and Huganir 2007; Delgado et al. 2007). Most endogenous AMPARs are made up of GluA1/GluA2 or GluA2/GluA3 combinations, whose activity-dependent trafficking is thought to be governed largely by the GluA1 or GluA2 subunits, respectively (Shepherd and Huganir 2007). Of all the GluA1 subunit phosphorylation sites, the serine 831 (ser831) and serine 845 (ser845) residues of the GluA1 subunit have been the most extensively studied. The phosphorylation of ser845 by protein kinase A (PKA) increases AMPAR content at extra-synaptic membrane sites (Oh et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2009), while phosphorylation of ser831 by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) or protein kinase C (PKC) increases AMPAR conductance (Derkach et al. 1999; Kristensen et al. 2011) and favors insertion of receptors into the postsynaptic spine (Hu et al. 2007). The phosphorylation of serine 880 residue (ser880) of the GluA2 subunit by PKC increases the likelihood of GluA2-containing AMPAR internalization (Chung et al. 2000; Seidenman et al. 2003). While these phosphorylation events are thought to be critical for the regulation of synaptic plasticity (Derkach et al. 2007; Santos et al. 2009; Chung et al. 2003), delineating their precise function remains a challenge because these residues can be differentially phosphorylated or dephosphorylated depending on the history of synaptic activation (Lee et al. 2000), and also because the functional impact of phosphorylation at one residue can be influenced by phosphorylation at other nearby residues (Gray et al. 2014).

Acute behavioral stress modifies fundamental brain processes including synaptic transmission, neural plasticity, executive functions, and memory processes (de Kloet et al. 2005; Holmes and Wellman 2009), and it can precipitate symptoms for psychiatric disorders (Brewin et al. 2000; Corcoran et al. 2003; Bogdan and Pizzagalli 2006; Hammen et al. 2009; Fullerton et al. 2004). There has been a growing understanding for how stress exerts specific changes on glutamatergic transmission in the brain (Popoli et al. 2012) in ways that can vary across time domains and brain regions (Joels et al. 2012; Karst et al. 2010; Groc et al. 2008; Dorey et al. 2012). The release of corticosteroids is a cardinal feature of the stress response, and the actions of these hormones in the brain are pivotal in mediating both beneficial and detrimental neural adaptations to stress (de Kloet et al. 2005; McEwen 2007). For example, it has been known for some time that acute behavioral stress, or treatment with corticosterone, increases AMPAR-mediated transmission in the hippocampus (Krugers et al. 1993; Karst et al. 2005). Corticosterone also increases the surface mobility of AMPARs in rat hippocampal neuron cultures (Groc et al. 2008), just as behavioral stress increases AMPAR levels in neuronal membranes in both the hippocampus (Conboy and Sandi 2010; Whitehead et al. 2013) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Yuen et al. 2009, 2011). While these molecular adaptions are considered critical for the tuning of synaptic strength and have been implicated in learning (Conboy and Sandi 2010; Popoli et al. 2012), the in vivo signaling pathways mediating these stress effects have not been fully clarified (Opazo and Choquet 2011).

Corticosterone is the major stress hormone in rodents and exerts its effects through mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) and glucocorticoid receptors (GRs). Classically, these receptors are known to mediate stress effects by affecting gene expression (Reul and de Kloet 1985; Funder 1997; Herman et al. 2003), yet there is also evidence for a population of membrane-localized MRs and GRs involved in rapid, non-genomic effects of stress hormones (Evanson et al. 2010; Groeneweg et al. 2011). MRs are heavily expressed in the hippocampus and are also present in the amygdala (AMY) and mPFC, while GRs are expressed more extensively throughout the brain (Reul and de Kloet 1985). Most studies probing MR/GR mechanisms have focused on their involvement during the initiation of stress, yet these receptors also have been implicated in memory consolidation mechanisms (de Kloet et al. 2005; Roozendaal et al. 2009). Considering that traumatic memories could be subject to disruption during the memory consolidation window (which begins immediately after the traumatic event), there also has been interest in understanding post-stress processes because their clarification could inform the development of early post-stressor therapeutic interventions (Cohen et al. 2008; Zohar et al. 2009; Cain et al. 2012). In line with this goal, previous research in our laboratory has interrogated the regulation of synaptic plasticity during the post-stress time domain. We have previously observed that post-stress GR blockade can prevent the stress-induced disruption of synaptic plasticity in the mPFC (Mailliet et al. 2008). Similar effects also have been observed with treatment with the antidepressant drug tianeptine (Rocher et al. 2004), which in cultured hippocampal neurons reduces the surface diffusion of AMPARs via a CaMKII-dependent mechanism, in a process mimicking LTP (Zhang et al. 2013).

In the interest of understanding the impact of stress on AMPAR regulation during the post-stress interval, and considering evidence that stress effects can vary over time and by brain region, here we have examined the dynamics of AMPAR phosphorylation at three serine residues (ser831-GluA1, ser845-GluA1, and ser880-GluA2) in four regions of the rat brain: the AMY, the mPFC, the dorsal hippocampus (DH), and the ventral hippocampus (VH), during the hour following a behavioral stress procedure. Moreover, we tested the impact of MR and GR blockade on AMPAR phosphorylation during this post-stress time window.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed with 65 adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (300–400 g) housed 4 per cage. Rats were maintained on a 12/12-h light/dark schedule (lights on at 7:00 am) in a temperature-controlled facility (22 ± 1 °C) with free access to food and water. Animals were kept at least 7 days after arrival from the supplier before being used in the experiment (Charles River, L’Arbresle, France). The stress protocol was performed during the beginning of the light phase (between 8:00 am and 12:00 noon). All procedures were conducted in conformity with National (JO 887–848) and European (2010/63/EU) rules for animal experimentation. Results from tissue collected from a portion of these animals (concerning MR and GR content) were reported previously (Caudal et al. 2014).

Stress and Injection Procedures

Elevated platform (EP) stress-treated rats were brought to an unfamiliar room where they were placed individually on an elevated and unsteady platform for 30 min. The platform dimensions were 20 × 21 cm2 and it was situated 100 cm above the ground. A bright fluorescent lamp (38 W, Goliath, JO-EL, Denmark; ~1500 Lux) was positioned at the same height as the platform, and its light beam was directed at the platform from 50 cm away. The lamp was included in the procedure because bright light is an ecologically relevant danger signal that evokes a low level of fear/stress in rats (File and Peet 1980; Godsil and Fanselow 2004).

Immediately after the platform procedure, rats were administered a sequence of two injections. The first injection (1 mL/kg i.p.) was either mifepristone (20 mg/mL DMSO) or spironolactone (50 mg/mL DMSO) or DMSO. The second injection was the anesthetic sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg i.p.). Control rats (non-stressed rats) received the same sequence of injections as the EP-stressed rats while being briefly removed from their home cage. Afterwards, the body temperatures of all the rats were maintained with homeothermic warming blankets (37 °C) until they were killed by decapitation 10 min or 60 min later. The groups were control-vehicle-10 min (n = 6), control-mifepristone-10 min (n = 6), control-spironolactone-10 min (n = 6), control-vehicle-60 min (n = 5), control-mifepristone-60 min (n = 4), control-spironolactone-60 min (n = 3), stress-vehicle-10 min (n = 6), stress-mifepristone-10 min (n = 6), stress-spironolactone-10 min (n = 6), stress-vehicle-60 min (n = 5), stress-mifepristone-60 min (n = 6), and stress-spironolactone-60 min (n = 6). Sodium pentobarbital was administered to retain continuity with our previous methodology for experiments that studied the impact of EP stress on in vivo electrophysiology in anesthetized rats (Rocher et al. 2004; Mailliet et al. 2008; Qi et al. 2009).

Drugs

The GR antagonist mifepristone (Sigma-Aldrich, France) and MR antagonist spironolactone (Sigma-Aldrich, France) were freshly dissolved in DMSO the day of the experiment and injected intra-peritoneally (20 and 50 mg/kg, respectively). They were administered in a volume of 1 mL/kg body weight.

Plasma Corticosterone Measurement

Trunk blood samples were collected just after decapitation. Samples were centrifuged at 1000×g, 4 °C, for 15 min, and the serum was stored at −20 °C. Plasma corticosterone was assessed by immunoassay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Corticosterone Immunoassay ® , DSL, Webster, Texas, USA).

Brain Sample Preparation

After decapitation, brains were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until processed. Using tissue punchers (0.50, 0.75 or 1.0 mm; Harris Unicore, USA), samples were extracted from 100-μm-thick sections prepared in a cryostat at −20 °C as described previously (Caudal et al. 2014). The mPFC (prelimbic and infralimbic) was sampled from 2.7 to 4.0 mm anterior of bregma. The AMY, DH, and VH were sampled from 2.0 to 3.5, 3.0 to 4.6, and 5.0 to 6.0 mm posterior of bregma, respectively, according to a rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson 1998).

Phosphorylation Studies

For phosphorylation studies, samples were immediately sonicated in 1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4, boiled for 10 min, and kept at −80 °C. Each sample was resuspended in sample buffer (Tris-base 250 mM, glycerol 40 %, SDS 8 %, β-mercaptoethanol 20 %, bromophenol blue 0.1 %).

Western Blotting

Twenty five µg of each sample was separated three times on three different gels (3 different phosphorylation sites), with 4–15 % running gels (26 wells, Criterion™ Precast Gel, Tris–HCl, Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), and transferred to a 0.2-µm PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Membranes were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in blocking buffer (TBS-Tween 20 0.1 %, BSA 5 %, NaN3 0.02 %). Immunoblotting was carried out overnight at 4 °C with phosphorylation-state-specific antibodies against ser831-GluA1 (Millipore, Molsheim, France), ser845-GluA1 (Millipore, Molsheim, France), and ser880-GluA2 (Interchim, Montluçon, France). Immunoblotting was also carried out on the same stripped membranes with antibodies that were not phosphorylation-state-specific against total GluA1 and GluA2 (Millipore, Molsheim, France) in blocking buffer. Membranes were washed three times with TBS-Tween 20 (0.1 %) and incubated with secondary HRP anti-rabbit antibody (dilution 1/1000) or HRP anti-mouse antibody (dilution 1/1000, only with the primary actin antibody) for 1 h at room temperature (P.A.R.I.S, Compiègne, France). At the end of the incubation, membranes were washed three times with TBS-Tween 20 and the immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence (Immun-Star™ WesternC™ kit, Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). A series of primary and secondary antibody dilutions and exposure times were used to optimize the experimental conditions for the linear sensitivity range of the autoradiography films (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA). Films were scanned on the GS-800 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), and the density of each band was quantified using the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France).

Data Analysis

Group differences were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVAs and t tests. Fisher LSD tests were used for post hoc contrasts. Any statistical tests yielding a p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. p values between 0.05 and 0.10 were referred to as non-significant trends. All statistical procedures were performed with Statistica software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Acute Stress Increased Plasma Corticosterone Levels

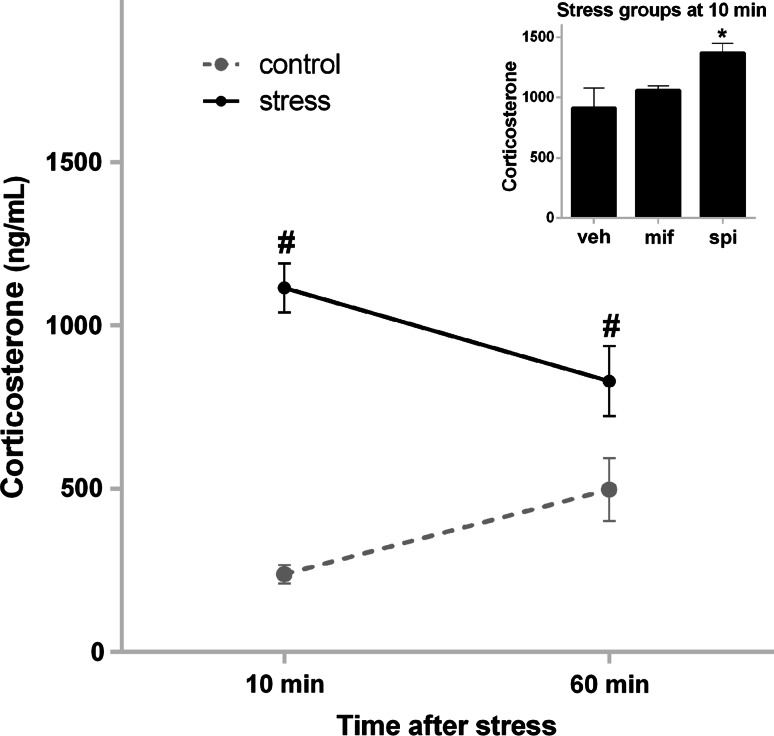

Stress exposure was associated with a high degree of plasma corticosterone compared to controls at 10 and 60 min post-stress, and the 60-min non-stressed controls exhibited higher levels of corticosterone compared to the 10-min controls (Fig. 1). The corticosterone concentration data were entered into a factorial ANOVA with between-subject factors for stress (control, stress), drug (vehicle, mifepristone, spironolactone), and time (10, 60 min). This analysis detected a main effect of stress (F 1,53 = 55.73, p < 0.000001) and also a significant stress × time interaction (F 1,53 = 11.06, p = 0.0016). Post hoc tests indicated that stress exposure led to elevated corticosterone compared to controls at each time point. Although no drug effects were detected with this analysis, at 10 min, post-stress spironolactone treatment was associated with elevated corticosterone compared to the vehicle-stress control (t test: t 10 = 2.50, p = 0.032) (Fig. 1 inset), which may result from the tendency for MR blockade to prolong the stress response by altering negative feedback on HPA axis activation (Cole et al. 2000).

Fig. 1.

Exposure to acute EP stress increased plasma corticosterone levels. Corticosterone data sampled from trunk blood 10 and 60 min after the end of stress. Data were collapsed across the Drug factor. Inset Spironolactone exposure was associated with elevated corticosterone levels in the stress conditions at 10 min. Error bars show standard error of the means (SEMs). The number sign indicates a significant difference compared to the non-stressed control group. Asterisk indicates a significant t test compared to the vehicle-treated group. AMY amygdala, DH dorsal hippocampus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, VH ventral hippocampus

GluA1 and GluA2 Subunits Displayed Distinct Phosphorylation Patterns After Behavioral Stress

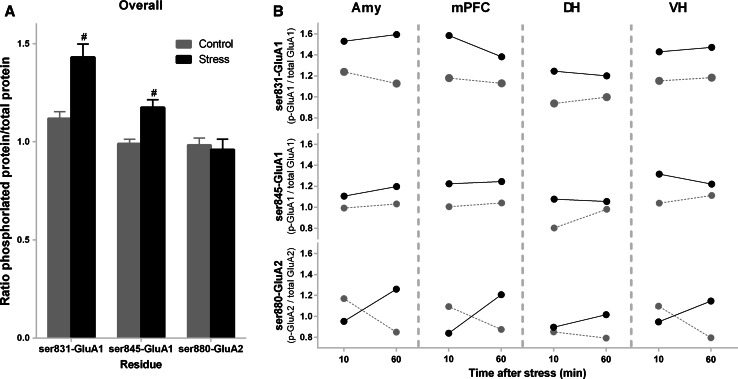

The first objective of our analyses of the AMPAR phosphorylation data was to contrast the impact of stress on the phosphorylation profile of the three AMPAR residues. For this purpose, phosphorylation data of the vehicle-treated rats were entered into a multiple-repeated measures ANOVA with between-subject factors of stress (control, stress), time (10, 60 min), and within-subject variables for residue (ser831-GluA1, ser845-GluA1, ser880-GluA2) and brain region (AMY, mPFC, DH, VH). Visual inspection of the data (Fig. 2) indicated that the three residues had different phosphorylation profiles after acute stress. This overall pattern was confirmed by a significant stress × residue interaction (F 2,36 = 3.49, p = 0.041), with planned comparisons indicating that exposure to EP stress increased the phosphorylation of ser831-GluA1 and ser845-GluA1. This analysis also indicated that ser831-GluA1 exhibited higher levels of phosphorylation compared to the other residues (residue: F 2,36 = 12.46, p = 0.00008) and the DH had less total phosphorylation compared to the other regions (region F 3,54 = 12.29, p = 0.000002).

Fig. 2.

Exposure to acute EP stress had differential effects on GluA1 and GluA2 phosphorylation. a Overall, the ser831 and ser845 GluA1 residues show increased phosphorylation compared to non-stressed control after a 30-min exposure to an elevated platform. Data were collapsed across brain region and time factors. The number sign indicates a significant difference compared to the non-stressed control group. Error bars represent the SEMs. b Trend lines showing mean phosphorylation levels for ser831-GluA1, ser845-GluA1, and ser880-GluA2 at 10 and 60 min post-stress. Data from stressed groups shown with black solid lines; data from non-stressed groups shown with gray dashed lines. AMY amygdala, DH dorsal hippocampus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, VH ventral hippocampus

To further characterize the phosphorylation patterns, we also analyzed each residue separately using a repeated-measures ANOVA with between-subject factors of stress (control, stress), time (10, 60 min), and a within-subject variable for brain region (AMY, mPFC, DH, VH). These tests confirmed that stress elevated the overall phosphorylation of the GluA1 residues (main effects of stress: ser831: F 1,18 = 4.83, p = 0.042; ser845: F 1,18 = 5.83, p = 0.027). Importantly, unlike the GluA1 residues, ser880-GluA2 exhibited a time-dependent phosphorylation pattern that varied by region (region × stress × time interaction: F 3,54 = 3.65, p = 0.018) (Fig. 2b, lower panel), whereby in the AMY, mPFC, and VH, there was a trend for decreased phosphorylation at 10 min post-stress followed by increased phosphorylation at 60 min. Overall, these results show that exposure to EP stress increased phosphorylation at the two GluA1 residues, whereas the impact of stress on ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation varied over time.

The GluA1 Subunit Residues Exhibited a High Degree of Similarity with Respect to Phosphorylation

Having sampled multiple brain regions and multiple serine residues, we were interested in exploring the degree to which phosphorylation at one residue would predict phosphorylation at the others. Therefore, we performed correlation analyses using data from the control-vehicle and stress-vehicle groups that was split by the sampling region (Table 1). Notably, although phosphorylated by different kinases, the two GluA1 residues (ser831 and ser845) displayed a high degree of correspondence in each brain region, whereas ser880-GluA2 was significantly correlated with ser831-GluA1 in the DH, but not elsewhere.

Table 1.

Within-region correlation coefficients for ser831-GluA1, ser845-GluA1, and ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation

| Comparison | Amygdala | mPFC | Dorsal hippocampus | Ventral hippocampus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ser831-GluA1 versus ser845-GluA1 | 0.752052* | 0.728553* | 0.728969* | 0.737308* |

| ser831-GluA1 versus ser880-GluA2 | 0.417096 | 0.138163 | 0.429325* | 0.307120 |

| ser845-GluA1 versus ser880-GluA2 | 0.270623 | −0.047003 | 0.357134 | 0.327987 |

* Indicates a significant correlation

Impact of Post-stress GR and MR Receptor Blockade on AMPAR Phosphorylation

To understand the relationship between corticosteroid receptor activation and AMPAR phosphorylation levels during the post-stress period, we next performed analyses to contrast the data from vehicle-treated rats with animals that were given either the GR antagonist mifepristone or the MR antagonist spironolactone, immediately after the EP stress procedure. Data from each residue were entered into separate repeated-measures ANOVAs each with a between-subject factor of group (control-vehicle, control-mifepristone, control-spironolactone, stress-vehicle, stress-mifepristone, stress-spironolactone) and a within-subject variable of brain region (AMY, mPFC, DH, VH). Because the previous analysis indicated that ser880-GluA exhibited time-dependent effects, data from this residue were split such that the 10-min groups were analyzed separately from the 60-min groups.

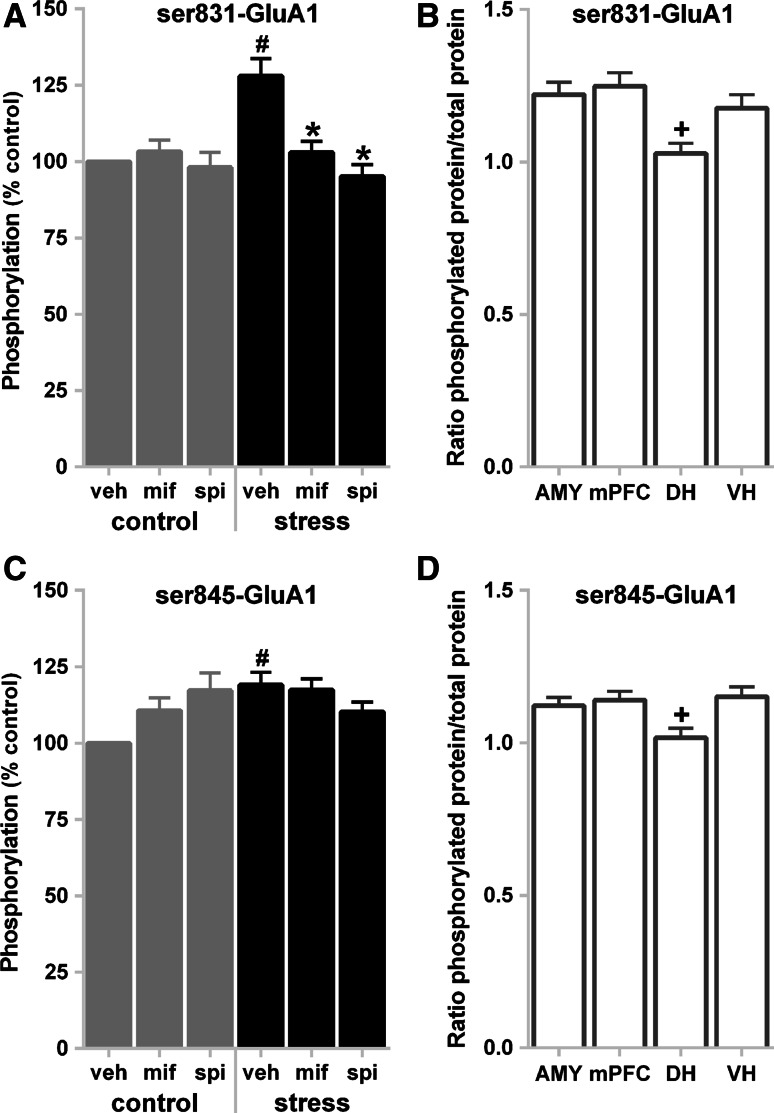

For ser831-GluA1, the analysis revealed significant effects for both group (F 5,59 = 2.54, p = 0.038) and brain region (F 3,177 = 20.50, p < 0.000001). Post hoc tests confirmed that exposure to stress increased ser831 phosphorylation compared to controls, while post-stress mifepristone or spironolactone decreased phosphorylation to control levels (Fig. 3a). Also, consistent with the analysis of the stress data above, the DH displayed significantly less phosphorylation overall compared to the other regions (Fig. 3b). For ser845-GluA1, there was no effect of group (F 5,59 = 1.08, p = 0.38) (Fig. 3c), yet the analyses detected a significant effect of brain region (F 3,177 = 12.87, p < 0.000001). Once again, the DH had less overall phosphorylation compared to the other sampling regions (Fig. 3d). Although the overall group effect was not significant, post hoc contrasts of the vehicle-treated groups suggested that stress increased ser845 phosphorylation (control-vehicle vs. stress-vehicle). The control groups treated with mifepristone or spironolactone did not reach significance by this measure.

Fig. 3.

Post-stress corticosteroid blockade decreased ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation. a Ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation data showing group means with the data split by the stress and drug factors. Data were collapsed across time and brain region factors and were normalized to the vehicle-treated non-stressed controls. b Ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation data showing group means split by brain region. Data were collapsed across the drug, time, and brain region factors. c Ser845-GluA1 phosphorylation data showing group means with the data split by the stress and drug factors. Data were collapsed across time and brain region factors and were normalized to the vehicle-treated non-stressed control. d Ser845-GluA1 phosphorylation data showing group means split by brain region. Data were collapsed across the drug, time, and brain region factors. The number sign indicates a significant difference compared to the vehicle-treated non-stressed control group. Asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to the vehicle-treated stressed control group. +indicates a significant group difference based on brain region. Error bars show SEMs. AMY amygdala, DH dorsal hippocampus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, mif mifepristone, spi spironolactone, veh vehicle, VH ventral hippocampus

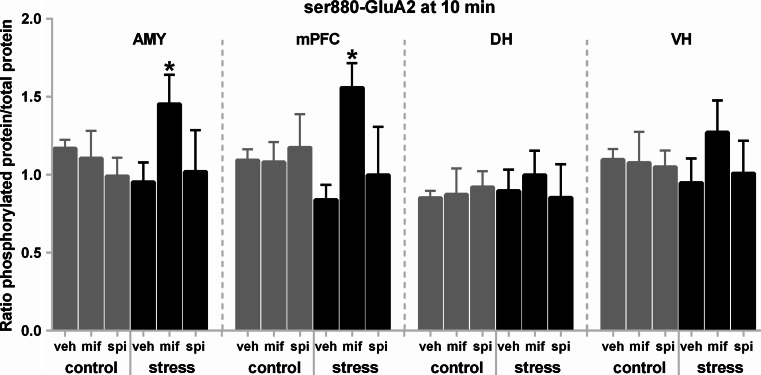

Analyses of the data from ser880-GluA2 indicated no effects of group at either 10 or 60 min post-stress (10 min: F 5,30 = 0.82, p = 0.55; 60 min: F 5,23 = 0.28, p = 0.92), but with significant effects of brain region at both time points, once again showing that the DH had less overall phosphorylation than the other regions (10 min: F 3,90 = 15.23, p < 0.00001; 60 min: F 3,69 = 14.36, p < 0.00001) (data not shown). There was also a significant group × brain region interaction at 10 min (F 15,90 = 2.07, p = 0.018). Here, mifepristone treatment selectively increased phosphorylation of ser880-GluA1 in the AMY and mPFC of stressed animals compared to stressed, vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 4). Overall, these results indicate that stress-induced ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation was reversed by treatment with post-stress corticosteroid receptor antagonists, whereas the similar effects were not observed at ser845-GluA1. GR blockade also seemed to augment ser880-GluA2 in the stress condition shortly after stress, but only in the AMY and mPFC.

Fig. 4.

Post-stress mifepristone treatment temporarily augmented ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation in the amygdala and mPFC of stressed animals. Ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation data at 10 min post-stress showing group means with the data split by the stress, brain region, and drug factors. Asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to the vehicle-treated stressed control group. Error bars show SEMs. AMY amygdala, DH dorsal hippocampus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, mif mifepristone, spi spironolactone, veh vehicle, VH ventral hippocampus

Discussion

These findings indicate that GluA1 and GluA2 subunit residues exhibit different phosphorylation dynamics during the hour following acute stress. The GluA1 subunit residues (ser831 and ser845) exhibited elevated stress-induced phosphorylation throughout this interval, and these effects were fairly similar across the four sampled brain regions. In contrast, in the AMY, mPFC, and VH, ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation varied over time with the tendency for decreased phosphorylation at 10 min post-stress leading to elevated phosphorylation later on. Additionally, correlational analyses suggested that the two GluA1 residues displayed significant within-region correspondence with respect to phosphorylation, whereas ser880-GluA2 displayed far less correlation with other residues. Finally, stress-induced GluA1 phosphorylation was curtailed at ser831-GluA1 by post-stress treatment of MR or GR antagonists, while no such effects were detected at ser845-GluA1 or ser880-GluA2. Together, these findings show how the post-stress phosphorylation dynamics of these AMPAR residues are distinct and that corticosteroid receptors maintain an ongoing role in the regulation of ser831-GluA1 during the post-stress interval. Moreover, these findings highlight that ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation can be manipulated after stress, which makes it an interesting candidate target for potentially limiting the effects of trauma by developing immediate post-stress drug interventions.

Most research investigating AMPAR processes in the brain uses cells maintained in culture or as slices (Shepherd and Huganir 2007), yet several groups have also investigated the influence of acute stress on AMPAR phosphorylation in vivo (Table 2). These reports indicate that, most often, acute stress exposure increases the phosphorylation of GluA1, which is consistent with our present findings. Considering the cases where both ser831 and ser845 were examined, it might be that the two residues have differential sensitivity to the type and duration of the stressor, whereby short bouts of stress only increase ser831 phosphorylation, whereas predator odors and longer-duration stressors may be more likely to influence both sites. Compared to GluA1, much less is known about the impact of behavioral stress on ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation. One study reported no effect in the PFC after brief exposure to swim stress (Caffino et al. 2015), whereas in the present experiment we observed a time-dependent shift from decreased phosphorylation to increased phosphorylation after 60 min of EP stress, which implies that ser880-GluA2 might also be sensitive to the duration of the stressor. Our results are also congruent with previous work demonstrating that tail shock stress strongly elevates PKC activity (Birnbaum et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2004), which phosphorylates ser880-GluA2. Differential timing effects related to AMPAR subunits have also been observed after the induction of hippocampal LTP in vivo, where GluA1 exhibited an immediate and sustained increase in cell surface expression, but GluA2 increased after a 20-min delay (Williams et al. 2007).

Table 2.

Influence of acute stress on ser831-GluA1 and ser845-GluA1 phosphorylation in vivo

| Stressor | Stressor duration (min) | Sampling time after stress (min) | Sampling method | Species | Residue | Region | Result | Author, date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fox urine | 5 | 0 | Whole homogenate | Mouse |

ser831 ser845 |

Hipp. Hipp. |

↑ ↑ |

Hu et al. 2007 |

| Swim | 5 | 15 | Crude synaptosome | Rat |

ser831 ser831 |

Hipp. PFC |

↑ ↔ |

Fumagalli et al. 2009 |

| Platform | 30 | 30 | Whole homogenate | Rat |

ser831 ser845 |

mPFC mPFC |

↑(trend) ↑(trend) |

Qi et al. 2009 |

| Platform | 30 | 30 | Whole homogenate | Rat |

ser831 ser831 |

AMY mPFC |

↔ ↓ |

Caudal et al. 2010 |

| ser831 | DH | ↓ | ||||||

| ser831 | VH | ↔ | ||||||

| ser845 | AMY | ↑ | ||||||

| ser845 | mPFC | ↔ | ||||||

| ser845 | DH | ↔ | ||||||

| ser845 | VH | ↑ | ||||||

| Restraint | 60 | 0 | Membrane fraction | Mouse | ser831 | Hipp. | ↑ | Fumagalli et al. 2011 |

| Restraint | 30 | 0 | Surface biotinylation and pull down | Rat | ser845 | Hipp. | ↑ | Whitehead et al. 2013 |

| Swim | 5 | 15 | Crude synaptosome | Rat | ser831 | PFC | ↑ | Caffino et al. 2015 |

AMY amygdala, DH dorsal hippocampus, Hipp whole hippocampus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, PFC prefrontal cortex, VH ventral hippocampus

Symbols: ↑ means increase in phosphorylation compared to non-stressed controls, ↓ means decrease in phosphorylation compared to non-stressed controls, ↔ means no change in phosphorylation compared to non-stressed controls. Sampling time refers to time delay between the end of the stress procedure until the moment of tissue sampling. Hu et al. (2007); Fumagalli et al. (2009); Qi et al. (2009); Caudal et al. (2010); Fumagalli et al. (2011); Whitehead et al. (2013); Caffino et al. (2015)

Beyond these timing effects, there are several notable implications of our results. Firstly, previous research has demonstrated that ser831-GluA1 and ser845-GluA1 phosphorylation may substitute for the other in mechanisms supporting synaptic plasticity and learning (Lee et al. 2010; Crombag et al. 2008), which implies that drug interventions attempting to reverse trauma-related stress effects might need to influence both residues to be effective. Our correlation analyses indicate that the two GluA1 sites exhibited a high degree of correspondent phosphorylation in each of the brain regions sampled (Table 1). Considering that these residues are phosphorylated by different kinases, the within-region correlation raises the possibility that there is a common upstream signaling element, or a downstream phosphatase, that regulates both residues. Identifying such molecules, which might co-regulate ser831 and ser845, could benefit the development of successful post-trauma drug interventions. Secondly, we observed that phosphorylation levels of ser831-GluA1 and ser880-GluA2 were correlated in the DH, with the same non-significant tendency in the AMY, but with no correlation in the mPFC and VH. Considering that PKC phosphorylates both of these residues, it might be that there are distinct regional differences in PKC activity (Busto et al. 1994), making PKC a candidate target for interrogating the mechanism leading to regional differences in stress-induced alterations of glutamatergic transmission (Popoli et al. 2012; Karst et al. 2010; Yuen et al. 2011), especially considering that stress hormones can directly bind to and activate specific isoforms of PKC (Alzamora and Harvey 2008), and these isoforms have variable expression in different cells in the brain (Naik et al. 2000). Thirdly, given the role of AMPAR phosphorylation in regulating AMPAR trafficking, it is likely that acute stress led to increased GluA1-containing AMPARs in the membrane (Hu et al. 2007; Oh et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2009), perhaps especially early on after stress when ser880-GluA2 was not yet phosphorylated (Chung et al. 2000; Seidenman et al. 2003).

One caveat of our interpretations is that we have previously reported that acute stress caused a different pattern of results, including a decrease of the phosphorylation of ser831-GluA1 in the mPFC in stressed animals compared to controls (Caudal et al. 2010). Given the overall consensus among the different stressors (Table 2), the results of our previous report seem somewhat anomalous. One possible explanation lies in the evidence that AMPA receptor phosphorylation is sensitive to previous experience. Namely, in vitro studies have shown that prior experience with patterned synaptic stimulation can alter the direction and locus of GluA1 phosphorylation (at both ser831 and ser845) induced by subsequent stimulation (Lee et al. 2000). Similarly, experience with prior stress can influence the sensitivity of in vivo synaptic plasticity to a second stressor (Rocher et al. 2004; Richter-Levin and Maroun 2010). Opposite effects on glutamatergic transmission have also been demonstrated in AMY slices after the first and second corticosterone treatments (Karst et al. 2010). Together, these observations strongly suggest that experience can induce metaplasticity in synapses, which influences how they will respond to subsequent stimulation (Fink and O’Dell 2009; Delgado and O’Dell 2005; Abraham 2008). Based on this idea, we speculate that the previous anomalous result might have been due to a synaptic history effect. That is to say, we offer the hypothesis that animals in that study might have been exposed to an extraneous stressor prior to the EP stress procedure [such as during transport from the supplier, or in the vivarium (Sorge et al. 2014)], which favored a shift in the direction of AMPAR phosphorylation because these residues may be especially sensitive to prior experience. Support for this interpretation comes from recent demonstrations that chronic stress decreased levels of GluA1 phosphorylation (Chandran et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015; Hsiao et al. 2011). Indirect support also comes from the observation that GluA1 is first phosphorylated and then dephosphorylated during a sequence of closely timed fear memory retrieval tests (Jarome et al. 2012). Thus, a first stressor might increase GluA1 phosphorylation, whereas a second stressor might tend toward dephosphorylation.

Stress and corticosterone can produce both rapid and delayed effects on glutamatergic transmission that have been ascribed to both non-genomic and genomic signaling mediated by MRs and GRs (Joels et al. 2012). Evidence supporting MR and GR involvement comes primarily from pharmacological experiments in which these receptors were blocked by antagonist drugs prior to the initiation of the stress or corticosterone treatments, as well as from MR/GR knockout mice. Yet, in the present investigation we gave the MR and GR antagonists immediately after a 30-min behavioral stress session and then measured the phosphorylation later on. This methodological difference has important implications for the interpretation of our results. Namely, our measurements probe the involvement of these receptors after the animals have already had sustained elevated plasma corticosterone levels for 30 min. Thus, instead of addressing the mechanisms involved during the initiation of stress, our work pertains to the maintenance of AMPAR subunit phosphorylation during the post-stress interval. This time epoch was chosen for its relevance to developing post-trauma drug interventions (Cohen et al. 2008; Cain et al. 2012).

Interestingly, we observed that post-stress treatment with spironolactone or mifepristone led to decreased ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation. The same drug treatments did not appear to influence stress-induced phosphorylation of ser845-GluA1, while mifepristone caused a region-selective short-duration elevation of ser880-GluA2 phosphorylation in the stress condition. These results suggest that ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation is an ongoing and dynamic post-stress process, which depends on corticosteroid receptors. One interpretation of this finding is that when corticosterone levels are high, ser831-GluA1 residues require corticosteroid receptor activation to maintain a high degree of elevated phosphorylation. This phenomenon might be related to the known involvement of MRs and GRs in rapid non-genomic processes (Groeneweg et al. 2011; Groc et al. 2008). Future experiments could target this question with knockout mice lacking MR and/or GR receptors, or by using shorter duration stressors to precisely clarify the time domain in which corticosteroid blockade can influence ser831-GluA1 phosphorylation. Since the stress-related changes in phosphorylation at ser845-GluA1 were largely insensitive to corticosteroid receptor blockade, and ser880-GluA2 had rather selective effects, the results suggest that other stress-related signaling molecules are involved. Considering the known role of noradrenaline in stress processes (Hu et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2012), it would be interesting to probe its involvement in future studies. The mifepristone effects that were observed in the mPFC might also be relevant for understanding how the antagonist reverses the stress-induced disruption of mPFC LTP (Mailliet et al. 2008).

Limitations

Our sampling method used whole homogenates which does not directly measure membrane content, which is important for AMPAR function. These measurements also do not discriminate between cell types within a brain region (pyramidal neurons, interneurons, astrocytes, etc.). Also, our experiments were conducted under pentobarbital anesthesia, which was included to mimic previous stress investigations that employed well-defined procedures for measuring phosphorylation events (Qi et al. 2009; Caudal et al. 2010; Mailliet et al. 2008). Also, in the present study animals were given i.p. injections of DMSO because it was the vehicle for mifepristone and spironolactone. In vitro, low concentrations of DMSO have been reported to increase non-NMDA-mediated EPSP amplitudes (Tsvyetlynska et al. 2005), which implies that our vehicle itself could have a direct influence on our measurements [but see (Julien et al. 2012)].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from INSERM and Paris Descartes University. DC was supported by a fellowship from the French Ministère de l’Education Nationale. MR had a financial support from Servier.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham WC (2008) Metaplasticity: tuning synapses and networks for plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(5):387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzamora R, Harvey BJ (2008) Direct binding and activation of protein kinase C isoforms by steroid hormones. Steroids 73(9):885–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum SG, Yuan P, Wang M, Vijayraghavan S, Bloom A, Davis D, Gobeske K, Sweatt J, Manji H, Arnsten A (2004) Protein kinase C overactivity impairs prefrontal cortical regulation of working memory. Science 306(5697):882–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan R, Pizzagalli DA (2006) Acute stress reduces reward responsiveness: implications for depression. Biol Psychiatry 60(10):1147–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(5):748–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busto R, Globus MYT, Neary JT, Ginsberg MD (1994) Regional alterations of protein kinase C activity following transient cerebral ischemia: effects of intraischemic brain temperature modulation. J Neurochem 63(3):1095–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffino L, Calabrese F, Giannotti G, Barbon A, Verheij MM, Racagni G, Fumagalli F (2015) Stress rapidly dysregulates the glutamatergic synapse in the prefrontal cortex of cocaine-withdrawn adolescent rats. Addict Biol 20(1):158–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain CK, Maynard GD, Kehne JH (2012) Targeting memory processes with drugs to prevent or cure PTSD. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 21(9):1323–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudal D, Godsil BP, Mailliet F, Bergerot D, Jay TM (2010) Acute stress induces contrasting changes in AMPA receptor subunit phosphorylation within the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus. PLoS One 5(12):e15282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudal D, Jay TM, Godsil BP (2014) Behavioral stress induces regionally-distinct shifts of brain mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor levels. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 8:19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran A, Iyo AH, Jernigan CS, Legutko B, Austin MC, Karolewicz B (2013) Reduced phosphorylation of the mTOR signaling pathway components in the amygdala of rats exposed to chronic stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 40:240–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Xia J, Scannevin RH, Zhang X, Huganir RL (2000) Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 differentially regulates its interaction with PDZ domain-containing proteins. J Neurosci 20(19):7258–7267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Steinberg JP, Huganir RL, Linden DJ (2003) Requirement of AMPA receptor GluR2 phosphorylation for cerebellar long-term depression. Science 300(5626):1751–1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Matar MA, Buskila D, Kaplan Z, Zohar J (2008) Early post-stressor intervention with high-dose corticosterone attenuates posttraumatic stress response in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 64(8):708–717. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M, Kalman B, Pace T, Topczewski F, Lowrey M, Spencer R (2000) Selective blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor impairs hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis expression of habituation. J Neuroendocrinol 12(10):1034–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy L, Sandi C (2010) Stress at learning facilitates memory formation by regulating AMPA receptor trafficking through a glucocorticoid action. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(3):674–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran C, Walker E, Huot R, Mittal V, Tessner K, Kestler L, Malaspina D (2003) The stress cascade and schizophrenia: etiology and onset. Schizophr Bull 29(4):671–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Sutton JM, Takamiya K, Holland PC, Gallagher M, Huganir RL (2008) A role for alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid GluR1 phosphorylation in the modulatory effects of appetitive reward cues on goal-directed behavior. Eur J Neurosci 27(12):3284–3291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F (2005) Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 6(6):463–475. doi:10.1038/nrn1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado JY, O’Dell TJ (2005) Long-term potentiation persists in an occult state following mGluR-dependent depotentiation. Neuropharmacology 48(7):936–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado JY, Coba M, Anderson CN, Thompson KR, Gray EE, Heusner CL, Martin KC, Grant SG, O’Dell TJ (2007) NMDA receptor activation dephosphorylates AMPA receptor glutamate receptor 1 subunits at threonine 840. J Neurosci 27(48):13210–13221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkach V, Barria A, Soderling TR (1999) Ca2+/calmodulin-kinase II enhances channel conductance of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate type glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96(6):3269–3274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkach VA, Oh MC, Guire ES, Soderling TR (2007) Regulatory mechanisms of AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 8(2):101–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorey R, Pierard C, Chauveau F, David V, Beracochea D (2012) Stress-induced memory retrieval impairments: different time-course involvement of corticosterone and glucocorticoid receptors in dorsal and ventral hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology 37(13):2870–2880. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanson N, Herman J, Sakai R, Krause E (2010) Nongenomic actions of adrenal steroids in the central nervous system. J Neuroendocrinol 22(8):846–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Peet LA (1980) The sensitivity of the rat corticosterone response to environmental manipulations and to chronic chlordiazepoxide treatment. Physiol Behav 25(5):753–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink AE, O’Dell TJ (2009) Short trains of theta frequency stimulation enhance CA1 pyramidal neuron excitability in the absence of synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci 29(36):11203–11214. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1450-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Wang L (2004) Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am J Psychiatry 161(8):1370–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Pasini M, Frasca A, Drago F, Racagni G, Riva MA (2009) Prenatal stress alters glutamatergic system responsiveness in adult rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurochem 109(6):1733–1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Caffino L, Vogt MA, Frasca A, Racagni G, Sprengel R, Gass P, Riva MA (2011) AMPA GluR-A receptor subunit mediates hippocampal responsiveness in mice exposed to stress. Hippocampus 21(9):1028–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder JW (1997) Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors: biology and clinical relevance. Annu Rev Med 48:231–240. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godsil BP, Fanselow MS (2004) Light stimulus change evokes an activity response in the rat. Learn Behav 32(3):299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EE, Guglietta R, Khakh BS, O’Dell TJ (2014) Inhibitory Interactions between Phosphorylation Sites in the C Terminus of α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic Acid-type Glutamate Receptor GluA1 Subunits. J Biol Chem 289(21):14600–14611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groc L, Choquet D, Chaouloff F (2008) The stress hormone corticosterone conditions AMPAR surface trafficking and synaptic potentiation. Nat Neurosci 11(8):868–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneweg FL, Karst H, de Kloet ER, Joels M (2011) Rapid non-genomic effects of corticosteroids and their role in the central stress response. J Endocrinol 209(2):153–167. doi:10.1530/JOE-10-0472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Kim EY, Eberhart NK, Brennan PA (2009) Chronic and acute stress and the prediction of major depression in women. Depress Anxiety 26(8):718–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Cullinan WE (2003) Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Front Neuroendocrinol 24(3):151–180. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Wellman CL (2009) Stress-induced prefrontal reorganization and executive dysfunction in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33(6):773–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao Y-H, Chen PS, Chen S-H, Gean P-W (2011) The involvement of Cdk5 activator p35 in social isolation-triggered onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficit in the transgenic mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 36(9):1848–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Real E, Takamiya K, Kang M-G, Ledoux J, Huganir RL, Malinow R (2007) Emotion enhances learning via norepinephrine regulation of AMPA-receptor trafficking. Cell 131(1):160–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarome TJ, Kwapis JL, Werner CT, Parsons RG, Gafford GM, Helmstetter FJ (2012) The timing of multiple retrieval events can alter GluR1 phosphorylation and the requirement for protein synthesis in fear memory reconsolidation. Learn Mem 19(7):300–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Sarabdjitsingh RA, Karst H (2012) Unraveling the time domains of corticosteroid hormone influences on brain activity: rapid, slow, and chronic modes. Pharmacol Rev 64(4):901–938. doi:10.1124/pr.112.005892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien C, Marcouiller F, Bretteville A, El Khoury NB, Baillargeon J, Hébert SS, Planel E (2012) Dimethyl sulfoxide induces both direct and indirect tau hyperphosphorylation. PLoS One 7(6):e40020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst H, Berger S, Turiault M, Tronche F, Schutz G, Joels M (2005) Mineralocorticoid receptors are indispensable for nongenomic modulation of hippocampal glutamate transmission by corticosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(52):19204–19207. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507572102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst H, Berger S, Erdmann G, Schutz G, Joels M (2010) Metaplasticity of amygdalar responses to the stress hormone corticosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(32):14449–14454. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914381107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen AS, Jenkins MA, Banke TG, Schousboe A, Makino Y, Johnson RC, Huganir R, Traynelis SF (2011) Mechanism of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulation of AMPA receptor gating. Nat Neurosci 14(6):727–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugers H, Koolhaas J, Bohus B, Korf J (1993) A single social stress-experience alters glutamate receptor-binding in rat hippocampal CA3 area. Neurosci Lett 154(1):73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-K, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, Bear MF, Huganir RL (2000) Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature 405(6789):955–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-K, Takamiya K, He K, Song L, Huganir RL (2010) Specific roles of AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 (GluA1) phosphorylation sites in regulating synaptic plasticity in the CA1 region of hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 103(1):479–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Sun QA, Chen Q, Lee TH, Huang Y, Wetsel WC, Michelotti GA, Sullenger BA, Zhang X (2009) Targeting inhibition of GluR1 Ser845 phosphorylation with an RNA aptamer that blocks AMPA receptor trafficking. J Neurochem 108(1):147–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Li J, Dai P, Zhao F, Zheng G, Jing J, Wang J, Luo W, Chen J (2015) Microglia activation regulates GluR1 phosphorylation in chronic unpredictable stress-induced cognitive dysfunction. Stress 18(1):96–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailliet F, Qi H, Rocher C, Spedding M, Svenningsson P, Jay TM (2008) Protection of stress-induced impairment of hippocampal/prefrontal LTP through blockade of glucocorticoid receptors: implication of MEK signaling. Exp Neurol 211(2):593–596. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2007) Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev 87(3):873–904. doi:10.1152/physrev.00041.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik MU, Benedikz E, Hernandez I, Libien J, Hrabe J, Valsamis M, Dow-Edwards D, Osman M, Sacktor TC (2000) Distribution of protein kinase Mζ and the complete protein kinase C isoform family in rat brain. J Comp Neurol 426(2):243–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MC, Derkach VA, Guire ES, Soderling TR (2006) Extrasynaptic membrane trafficking regulated by GluR1 serine 845 phosphorylation primes AMPA receptors for long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem 281(2):752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo P, Choquet D (2011) A three-step model for the synaptic recruitment of AMPA receptors. Mol Cell Neurosci 46(1):1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1998) The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 4th edn. Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- Popoli M, Yan Z, McEwen BS, Sanacora G (2012) The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci 13(1):22–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H, Mailliet F, Spedding M, Rocher C, Zhang X, Delagrange P, McEwen B, Jay TM, Svenningsson P (2009) Antidepressants reverse the attenuation of the neurotrophic MEK/MAPK cascade in frontal cortex by elevated platform stress; reversal of effects on LTP is associated with GluA1 phosphorylation. Neuropharmacology 56(1):37–46. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, de Kloet ER (1985) Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology 117(6):2505–2511. doi:10.1210/endo-117-6-2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Levin G, Maroun M (2010) Stress and amygdala suppression of metaplasticity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 20(10):2433–2441. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocher C, Spedding M, Munoz C, Jay TM (2004) Acute stress-induced changes in hippocampal/prefrontal circuits in rats: effects of antidepressants. Cereb Cortex 14(2):224–229. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhg122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McReynolds JR, Van der Zee EA, Lee S, McGaugh JL, McIntyre CK (2009) Glucocorticoid effects on memory consolidation depend on functional interactions between the medial prefrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci 29(45):14299–14308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S, Carvalho A, Caldeira M, Duarte C (2009) Regulation of AMPA receptors and synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience 158(1):105–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenman KJ, Steinberg JP, Huganir R, Malinow R (2003) Glutamate receptor subunit 2 Serine 880 phosphorylation modulates synaptic transmission and mediates plasticity in CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci 23(27):9220–9228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Huganir RL (2007) The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23:613–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorge RE, Martin LJ, Isbester KA, Sotocinal SG, Rosen S, Tuttle AH, Wieskopf JS, Acland EL, Dokova A, Kadoura B (2014) Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nat Methods 11(6):629–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvyetlynska NA, Hill RH, Grillner S (2005) Role of AMPA receptor desensitization and the side effects of a DMSO vehicle on reticulospinal EPSPs and locomotor activity. J Neurophysiol 94(6):3951–3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead G, Jo J, Hogg EL, Piers T, Kim D-H, Seaton G, Seok H, Bru-Mercier G, Son GH, Regan P (2013) Acute stress causes rapid synaptic insertion of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors to facilitate long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Brain 136(12):3753–3765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Guévremont D, Mason-Parker SE, Luxmanan C, Tate WP, Abraham WC (2007) Differential trafficking of AMPA and NMDA receptors during long-term potentiation in awake adult animals. J Neurosci 27(51):14171–14178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C-H, Huang C-C, Hsu K-S (2004) Behavioral stress modifies hippocampal synaptic plasticity through corticosterone-induced sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Neurosci 24(49):11029–11034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen EY, Liu W, Karatsoreos IN, Feng J, McEwen BS, Yan Z (2009) Acute stress enhances glutamatergic transmission in prefrontal cortex and facilitates working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(33):14075–14079. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906791106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen EY, Liu W, Karatsoreos IN, Ren Y, Feng J, McEwen BS, Yan Z (2011) Mechanisms for acute stress-induced enhancement of glutamatergic transmission and working memory. Mol Psychiatry 16(2):156–170. doi:10.1038/mp.2010.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Etherington LA, Hafner AS, Belelli D, Coussen F, Delagrange P, Chaouloff F, Spedding M, Lambert JJ, Choquet D, Groc L (2013) Regulation of AMPA receptor surface trafficking and synaptic plasticity by a cognitive enhancer and antidepressant molecule. Mol Psychiatry 18(4):471–484. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Hoogenraad CC, Joëls M, Krugers HJ (2012) Combined β-adrenergic and corticosteroid receptor activation regulates AMPA receptor function in hippocampal neurons. J Psychopharmacol 26(4):516–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar J, Sonnino R, Juven-Wetzler A, Cohen H (2009) Can posttraumatic stress disorder be prevented? CNS Spectr 14(1 Suppl 1):44–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]