Abstract

This study was aimed to investigate the treatment mechanisms of 5-[5-(2-nitrophenyl) furfuryliodine]-1,3-diphenyl-2-thiobarbituric acid (UCF-101) in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion (CIR) model rats. Total of 54 healthy male Wistar rats were randomly assigned into three groups, namely sham group, vehicle group, and UCF-101 group. The CIR-injured model was established by right middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion. Neurological function was assessed by an investigator according to the Longa neurologic deficit scores. Meanwhile, the cerebral tissue morphology and apoptotic neurons were evaluated by H&E and TUNEL staining, respectively. Additionally, the expressions of caspase 3, p-p38, and p-ERK were detected by immunohistochemistry or/and Western blotting assays. As results, neurologic deficit and pathological damage were obviously enhanced and TUNEL positive neurons were significantly increased in CIR-injured rats, as compared with those in sham group. Furthermore, the expressions of caspase 3, p-p38, and p-ERK were also significantly increased in vehicle group than those in sham group (P < 0.05). However, UCF-101 treatment could markedly weaken the neurologic deficit with lower scores and improve pathological condition. After UCF-101 treatment, TUNEL positive neurons as well as the expression of caspase 3 were significantly decreased than those in vehicle group (P < 0.05). Besides, p-p38 was decreased while p-ERK was increased in UCF-101 group than those in vehicle group (P < 0.05). Therefore, we concluded that the protective effects of UCF-101 might be associated with apoptosis process and MAPK signaling pathway in the CIR-injured model.

Keywords: Cerebral ischemia–reperfusion, UCF-101, Apoptosis neurons, MAPK

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) plays a dominant role in the whole body, and neuroinflammation is contributed to the pathogenesis of neurological disorders, such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, traumatic injury, and multiple sclerosis (Nimmo and Vink 2009). Ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) has been reported to be the third leading cause of death worldwide (Lehotsky et al. 2009a; Liu et al. 2009), which refers to the tissue damage caused by blood supplication after a period of ischemia (Lutz et al. 2010; Szydlowska and Tymianski 2010). The pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia involves a complex sequence of physiological events including a well-documented inflammatory cascade characterized by the activations of glial cells (microglia and astrocytes) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Madinier et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2010). It has been reported that the deregulation of apoptosis could contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases as well as the IRI of organs (Bhuiyan and Fukunaga 2009). Nowadays, a large number of efforts have been made to investigate effective strategies to protect the graft from cell loss by interfering apoptosis process and reducing cell death (Pozo Devoto et al. 2008).

Omi/HtrA2 is a mitochondrial serine protease and exerts either proapoptotic or anti-apoptotic activities in neurons (Bhuiyan and Fukunaga 2009). Yoshioka et al. demonstrated that Omi/HtrA2 releasing into the cytosol after ischemia causes neuronal injury by inhibiting the expression of X chromosome-linked inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein (XIAP) (Yoshioka et al. 2013). The 5-[5-(2-nitrophenyl)furfuryliodine]-1,3-diphenyl-2-thiobarbituric acid (UCF-101) is a specific inhibitor of Omi/HtrA2 (Cilenti et al. 2003) and it owns the organ protective effects in cerebral IRI, cardiomyocyte dysfunction, S-nitrosoglutathione, and tubular fibrosis (Liu et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2010). Furthermore, UCF-101 can decrease the quantity of the apoptosis neurons via increasing the expression of XIAP during the cerebral ischemia–reperfusion (CIR) (Zhang et al. 2011). However, the molecular mechanisms of UCF-101 treatment in CIR injure is still far from completely clear.

During the last decade, a variety of signaling molecules have been documented to be involved in the progression of IRI (Lehotsky et al. 2009b; Gidday 2006). Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a serine/threonine kinases family and acts as signal transduction mediators, which regulate various cellular functions (Lu et al. 2011). MAPK/ERK/p38 pathway mainly plays as a mediator when cells are under stresses such as inflammation and apoptosis (Irving et al. 2000). An increase of MAPK/ERK signaling was found after UCF-101 treatment according to the study of Klupsch et al. (2006). Thus, we speculated that MAPK/ERK/p38 signaling pathway might be critical in the treatment process of UCF-101.

In this study, CIR-injured rat model was built to investigate the molecular mechanism of UCF-101 treatment in IRI. Neurologic deficit was evaluated by scoring and pathological changes were observed by H&E staining. Apoptosis was studied by detecting TUNEL positive neurons as well as the expressions of caspase 3. Additionally, p-p38 and p-ERK levels were also examined.

Materials and Methods

Animals

A total of 60 healthy male Wistar rats (weighing 250–300 g) were provided by Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, CAAS (Heilongjiang, China). The rats were housed in the animal house with free access to sterile water and food. The animal house was maintained at 50–70 % relative humidity, 23 ± 1 °C temperature, and a 12/12 h light and dark cycle. All experiments were approved and licensed by the Animal Protection Association and all the animals were handled following the guidelines according to the ethical principles of laboratory animal care.

Grouping and Modeling

All the rats were randomly assigned into three groups: sham group (n = 18), rats were prepared in the same way without carotid occlusion; vehicle group (n = 18); and UCF-101 group (n = 18). The CIR rat model was constructed in middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) according to the modified Longa method (Fukunaga et al. 1999). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 10 % chloral hydrate as the dose of 300 mg/kg of body weight. Then a 4–0 nylon monofilament with a noose was inserted into the right common carotid artery, and advanced into the internal carotid artery until it blocked the origin of the MCA. After ischemia for 1 h, reperfusion was performed by filament withdrawal to regain blood flow for 12 h. For the UCF-101 group, rats were intraperitoneally injected with UCF-101 (Calbiochem; Darmstadt, Germany) as a dose of 1.5 μmol/kg at 10 min before reperfusion. An equal volume of saline was supplied for the sham and vehicle group. During the whole surgical procedure, temperature in rectal was recorded and maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C.

Neurological Function Evaluation

At 12 h after reperfusion, neurological function assessment was conducted by one of the investigator who was unknown about the grouping according to the Longa neurologic deficit scores (Longa et al. 1989) as the following: score 0, no neurological deficit symptoms; score 1, the left forelimb could not be completely straighten and lifting tail test was positive; score 2, a circular motion to the left when walking; score 3, falling to the left when walking or do not walk spontaneously; and score 4, lose consciousness and cannot walk independently.

Histological Observation

At 12 h after reperfusion, the brains of rats were separated and fixed using 4 % paraformaldehyde. After dehydrated with gradient ethanol, vitrified with xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax, the slices were cut into slices about 5-μm thicknesses utilizing a microtome. The sections were dried in a 37 °C incubator overnight for the further experiments of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, TUNEL staining, and immunohistochemistry.

H&E staining was conducted to observe the cerebral tissue morphology. After deparaffinized with xylene, stained with HE, the sections were observed by light microscopy. Random 10 visions were chosen for each section.

TUNEL Assay

The changes of apoptotic neurons were evaluated by TUNEL staining. The sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated with xylene and graded alcohol series. DNA fragments were labeled by fluorescein-dUTP to detect the number of apoptotic neurons according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Wuhan Boster biotechnology companies, Hubei, China). Three slices were chosen for each animal and 10 visions were selected for each slice to calculate the apoptotic cells number (×200), and the average was considered as the apoptotic cell number.

Immunohistochemistry

After deparaffinized and rehydrated, the specimens were blocked with goat serum at 37 °C for 30 min. Then primary antibodies of mouse polyclonal p-p38 and p-ERK (1:200 dilution; Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washed with PBS for three times, the specimens were then incubated with anti-mouse IgG (1:1000 dilution; Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, avidin–biotin-HRP complex (ABC, 1:200; Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, USA) was applied at 37 °C for 1 h. At last, the reaction products was visualized with 3-3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd., Gillingham Dorset, UK) for 15 min, followed by dehydration, transparent, and mounted with neutral gum. Total five tissue sections were chosen and ten visions were observed for each section under microscopy (magnification of ×200), and the average was considered as the positive cells for rats.

Western Blotting

Brain tissue was separated from rats and grinded with 1 ml lysis buffer. After centrifugation, the supernatant protein concentration was detected using Bradford assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The protein samples (100 μl) were mixed with 20 μl 5× loading buffer and denatured at 100 °C for 5 min. The protein samples were separated by 10 % SDS-polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5 % skim milk for 1 h at room temperature, followed by an overnight incubation with primary antibodies (mouse anti-p-p38, anti-p-ERK, and anti-β-actin, 1:1000; Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd) at 4 °C. After washed, the membranes were incubated with anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co., Ltd) at room temperature for 1 h. The immunoreactive bands were detected and visualized by electrochemiluminescent (ECL) detection system (Amersham Life Sciences, Inc., Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA). Quantiscan 4.4 analysis software was performed to measure the optical density for each band.

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed by using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc multiple comparisons with Bonferroni test. P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant difference.

Results

UCF-101 Improved the Neurological Function in CIR Rats

Neurological deficits were evaluated according to the Longa neurologic deficit scores and the results were shown in Table 1. No neurobehavioral dysfunction was discovered in the rats of sham group. However, the rats in vehicle group appeared sever dysfunction of right limb with higher scores than those in sham group (P < 0.05). After UCF-101 treatment, the neurobehavioral function of rats was obviously improved with the significantly decreased scores, as compared with CIR rats in vehicle group (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Neurological function evaluation for the rats

| Groups | N | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| Sham group | 18 | 0 |

| Vehicle group | 18 | 2.33 ± 0.52 |

| UCF group | 18 | 1.67 ± 0.53* |

* P < 0.05 versus vehicle group

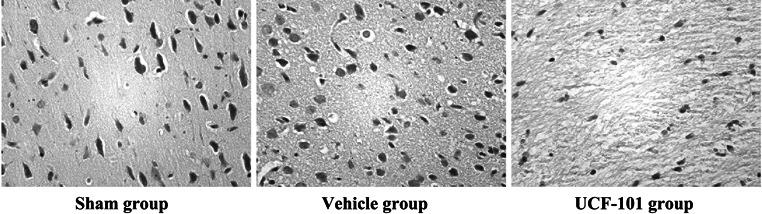

UCF-101 Alleviated CIR-Induced Neuronal Morphological Changes

The neuronal morphology of brain tissues were observed by H&E staining. As shown in Fig. 1, cells in sham group were observed with normal morphology, distinguishable cell contour and they were arranged in neat rows. Meanwhile, nucleoli were clearly observed in the center of cells. However, the neuronal cells in vehicle group were characterized by decreased cell size, disorganized, unclear structure, interstitial edema, nuclear pyknosis, and chromatin condensation. Compared with the vehicle group, UCF-101 treatment could markedly improve the pathological conditions, as only a few neurons appeared disorganized, hyperchromasia and nuclear pyknosis.

Fig. 1.

UCF-101 alleviated cerebral ischemia–reperfusion-induced neuronal morphological changes. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was conducted to observe the cerebral tissue morphology at 12 h after reperfusion (×200)

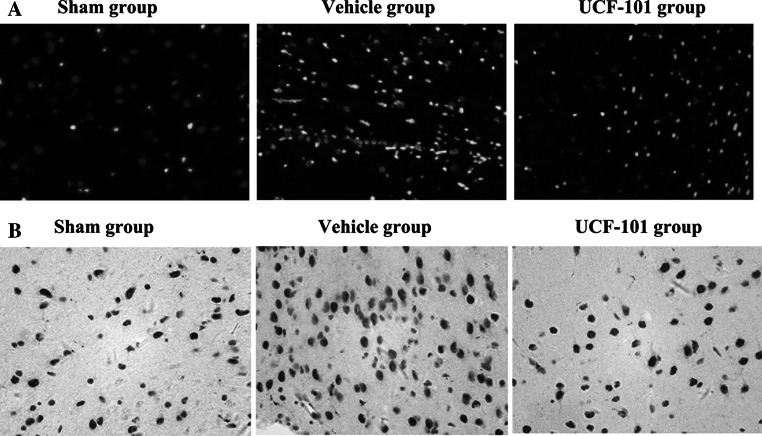

Apoptosis was Significantly Weakened After UCF-101 Treatment

As shown in Fig. 2a, apoptosis cells were rarely observed in the sham group, while they were significantly increased in CIR injury group. However, a notable reduction of the apoptotic cells number was found after treated with UCF-101 compared with those in vehicle group (52.14 ± 11.25 vs 90.26 ± 15.64, P < 0.01). Besides, the expression of caspase 3 was detected by immunohistochemistry. Consistent with the TUNEL results, overexpression of caspase 3 was found in vehicle group and it was significantly reduced in UCF group (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

UCF-101 reduced apoptosis in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion rats. a Apoptotic neurons in cortex by TUNEL assay (×200); b The expressions of caspase 3 by immunohistochemistry (×200)

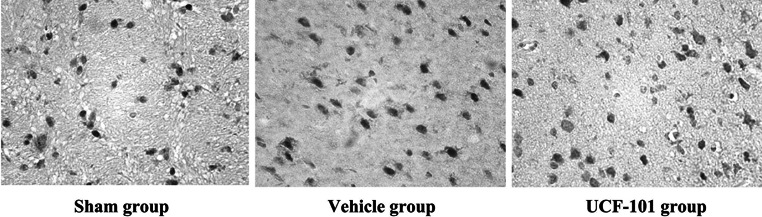

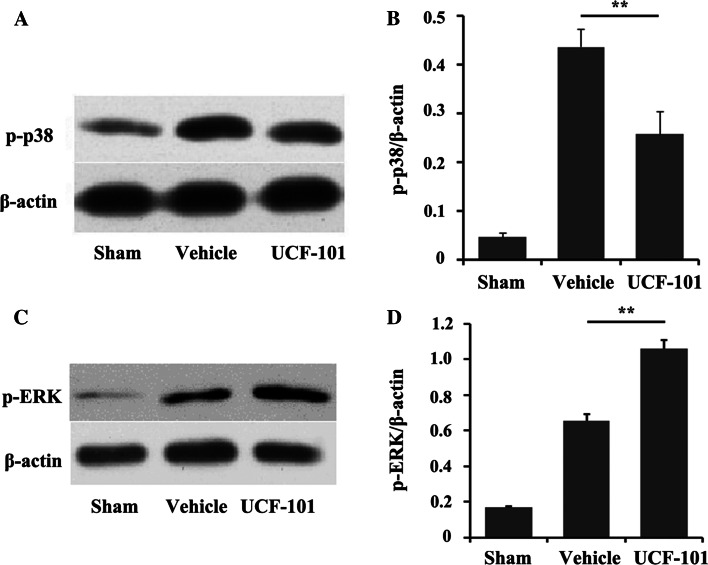

The Expressions of p-p38 and p-ERK were Changed After UCF-101 Treatment

The immunohistochemistry results of p-p38 are exhibited in Fig. 3. p-p38 was mainly located in nucleus and few appeared in cytoplasm. Compared with the sham group, the expression level of p-p38 was significantly higher in vehicle group (P < 0.05). Meanwhile, UCF-101 could effectively reduce the expression level of p-p38 (P < 0.05). Consistently, the expression levels of p-p38 were also increased in vehicle group and significantly decreased after UCF-101 treatment according to the Western blotting analysis (Fig. 4a). In addition, compared with sham group, the p-ERK levels were increased in CIR model and kept increasing after UCF-101 treatment (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, the differences were reflected clearly with the relative protein expression (Fig. 4b, d).

Fig. 3.

The expression of p-p38MARK by immunohistochemistry (×200)

Fig. 4.

The expressions of p-p38 and p-ERK were changed after UCF-101 treatment. The expression of p-p38 by Western blotting (a) and the relative protein expression (b). The expression of p-ERK by Western blotting (c) and the relative protein expression (d). Columns mean (n = 3); bars SD; **P < 0.01 versus vehicle group

Discussion

The protect mechanism of UCF-101, a specific inhibitor of Omi/HtrA2, was investigated in this present study by building CIR rat model. According to the results, UCF-101 treatment was demonstrated to extenuate the CIR injury and decrease the apoptotic neurons. Besides, the expression level of p-p38 was significantly reduced and p-ERK was upregulated after UCF-101 treatment.

Although reperfusion of blood flow is considered to be necessary for survival, reperfusion aggravates the brain injury rather than restores the normal function (Luo et al. 2014). Increasing studies revealed that CIR in neurological dysfunction mainly referred to the deterioration of motor function (Vaibhav et al. 2013). Neurologic findings, such as neurologic score, are the symptomatic indicators of I/R-induced brain damage (Yaidikar and Thakur 2015). Existing evidences suggested that neurologic scores were correlated with the cerebral infarct size (Yates et al. 2013) and high neurologic scores also have been demonstrated in the CIR models by multiply studies (Liu et al. 2015). Consistent with the previous studies, high neurologic scores also exited in the CIR model group according to our results. The decreasing of neurologic scores in the UCF-101 group suggested that UCF-101 could obviously improve the brain injury and motor function.

Apoptosis was obviously occurred in the injured neurons showed by positive TUNEL staining, nuclear condensation, and agarose gel electrophoresis, which suggested that the apoptosis of neurons was a underlying mechanism in the death of neurons (Yin et al. 2014). TUNEL staining was a common method to assess the apoptosis of neurons in previous studies on CIR models (Gheibi et al. 2014), which was also performed in our study. Anti-apoptotic drugs have a great potential to be as neuroprotective agents by blocking apoptosis pathway, inhibiting neuronal apoptosis, and reducing the volume of cerebral infarction in CIR-injured rats (Sairanen et al. 2006; Taoufik et al. 2007). For example, anemonin alleviated the nerve injury induced by CIR through inhibiting apoptosis pathway (Jia et al. 2014). Besides, apoptosis pathway is also involved in the heart protection of glycyrrhizin in IRI according to the study of Zhai et al. UCF-101, as a new specific inhibitor of Omi/HtrA2, has been shown to play the protective role of brain, heart, and kidney by inhibiting the apoptosis process (Althaus et al. 2007). Althaus et al. found that UCF-101 could inhibit the activity of Omi/HtrA2 and prevent the degradation of XIAP; thereby, the activities of caspase 3/9 were significantly inhibited and IRI was notably improved (Althaus et al. 2007). In this study, the apoptosis neurons and the expressions of caspase 3 were significantly decreased after UCF-101 treatment, which also confirmed the anti-apoptotic effects of UCF-101 in the ICR models.

Additionally, the anti-apoptotic mechanism of UCF-101 in ICR model was also exploited. It has been reported that apoptosis was a result of the decreasing activation of tyrosine kinase receptor by targeting their ligands (Li et al. 2012). Brain damages, including ischemia and hypoxia were transduced to the nucleus through a series of signal pathway, leading to the expression changes of related genes and then inducing the neuronal apoptosis (Chen et al. 2011). Previous studies have reported that the activation of MAPK/p38 and MAPK/ERK kinases plays critical roles in ischemia protects against neuronal damage (Roux and Blenis 2004; Bu et al. 2007). Muhammad et al. reported that MAPK/p38 signaling pathway could lead to cell death, redox stress, and IRI (Ashraf et al. 2014). Several studies have implicated the MAPK signal pathway in IRI of different organs. Kobayashi and his colleagues reflected the strong phosphorylation of p38-MAPK in IRI of the liver (Kobayashi et al. 2002). In the kidney, the induction of TNF gene transcription after IRI is due to the direct activation of p38-MAPK (Donnahoo et al. 1999). Meanwhile, p38-MAPK can bind to caspase-3 in nucleus and regulate caspase-3 expression during actinomycin D-induced apoptosis (Wang et al. 2009). Studies have shown that brain damages of ischemia and hypoxia can activate the p38-MAPK signaling pathway; furthermore, sustaining activation of p38-MAPK may induce neuronal apoptosis in rat focal CIR model (Lu et al. 2011). It is also reported that regulating the phosphorylation of p38-MAPK could inhibit apoptosis in response to extrinsic stresses (Takebe et al. 2011; Sui et al. 2014). Consistent with the previous study, the phosphorylation of p38-MAPK was increased in CIR model and notably decreased after UCF-101 treatment, which suggested that UCF-101 might reduce the neuronal apoptosis by weakening the activation of p38-MAPK. The activation of ERK is also associated with the protection of neurons from lethal ischemia (Cao et al. 2011) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 (P-ERK) level, which represents the ERK activation. It was demonstrated that ERK caused neuronal damage after ischemia (Campos-Gonzalez and Kindy 1992), while the phosphorylation of ERK might support neuronal survival through blocking cell proliferation and differentiation (Cao et al. 2011). However, whether an increase of ERK1/2 phosphorylation is a protective or detrimental factor is highly debatable (Sawe et al. 2008). Yue et al. demonstrated that p38 mediated apoptosis, whereas ERK plays a protective role in IR of cardiomyocytes, and the dynamic balance is critical in determining fate of cardiomyocyte reperfusional injury (Yue et al. 2000). In this present study, phosphorylation of ERK was increased in CIR model and kept increasing after UCF-101 treatment, which indicated that phosphorylation of ERK might play a neuroprotection role in UCF-101 treatment for CIR. Therefore, we speculated that UCF-101 played anti-apoptotic function in the CIR-injured rats by regulating the activation of MAPK/p38/ERK pathway.

In conclusion, UCF-101 contributed to treat CIR-injured rats owing to improving the neurologic deficit and decreasing apoptosis, and MAPK/p38/ERK pathway might be involved in the treatment process. Our study might help reveal the molecular mechanisms of UCF-101 and provide new ideas for the studies on UCF-101. However, more molecular experiments should be taken to certify these results and exploit the specific mechanisms in future.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the scientific research Project of Education Department of Heilongjiang Province (12511255).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Contributor Information

Jing Ma, Email: Jingma2009@aliyun.com.

Baozhong Shen, Phone: +86-0451-86104052, Email: baozhong_shen@163.com.

References

- Althaus J, Siegelin MD, Dehghani F, Cilenti L, Zervos AS, Rami A (2007) The serine protease Omi/HtrA2 is involved in XIAP cleavage and in neuronal cell death following focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Neurochem Int 50(1):172–180. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2006.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf MI, Ebner M, Wallner C, Haller M, Khalid S, Schwelberger H, Koziel K, Enthammer M, Hermann M, Sickinger S, Soleiman A, Steger C, Vallant S, Sucher R, Brandacher G, Santer P, Dragun D, Troppmair J (2014) A p38MAPK/MK2 signaling pathway leading to redox stress, cell death and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Commun Signal 12:6. doi:10.1186/1478-811X-12-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan MS, Fukunaga K (2009) Mitochondrial serine protease HtrA2/Omi as a potential therapeutic target. Curr Drug Targets 10(4):372–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu X, Huang P, Qi Z, Zhang N, Han S, Fang L, Li J (2007) Cell type-specific activation of p38 MAPK in the brain regions of hypoxic preconditioned mice. Neurochem Int 51(8):459–466. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2007.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Gonzalez R, Kindy MS (1992) Tyrosine phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein kinase after transient ischemia in the gerbil brain. J Neurochem 59(5):1955–1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, Qian M, Wang XF, Wang B, Wu HW, Zhu XJ, Wang YW, Guo J (2011) Negative feedback regulation of Raf/MEK/ERK cascade after sublethal cerebral ischemia in the rat hippocampus. Neurochem Res 36(1):153–162. doi:10.1007/s11064-010-0285-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S-D, Yang D-I, Lin T-K, Shaw F-Z, Liou C-W, Chuang Y-C (2011) Roles of oxidative stress, apoptosis, PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis in cerebral ischemia. Int J Mol Sci 12(10):7199–7215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilenti L, Lee Y, Hess S, Srinivasula S, Park KM, Junqueira D, Davis H, Bonventre JV, Alnemri ES, Zervos AS (2003) Characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor for the pro-apoptotic protease Omi/HtrA2. J Biol Chem 278(13):11489–11494. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212819200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnahoo KK, Shames BD, Harken AH, Meldrum DR (1999) Review article: the role of tumor necrosis factor in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Urol 162(1):196–203. doi:10.1097/00005392-199907000-00068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga A, Uchida K, Hara K, Kuroshima Y, Kawase T (1999) Differentiation and angiogenesis of central nervous system stem cells implanted with mesenchyme into ischemic rat brain. Cell Transpl 8(4):435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheibi S, Aboutaleb N, Khaksari M, Kalalian-Moghaddam H, Vakili A, Asadi Y, Mehrjerdi FZ, Gheibi A (2014) Hydrogen sulfide protects the brain against ischemic reperfusion injury in a transient model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Mol Neurosci: MN 54(2):264–270. doi:10.1007/s12031-014-0284-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidday JM (2006) Cerebral preconditioning and ischaemic tolerance. Nat Rev Neurosci 7(6):437–448. doi:10.1038/nrn1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving EA, Barone FC, Reith AD, Hadingham SJ, Parsons AA (2000) Differential activation of MAPK/ERK and p38/SAPK in neurones and glia following focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 77(1):65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Han B, Yang S, Zhao J (2014) Anemonin alleviates nerve injury after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion (i/r) in rats by improving antioxidant activities and inhibiting apoptosis pathway. J Mol Neurosci: MN 53(2):271–279. doi:10.1007/s12031-013-0217-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim DS, Park MJ, Cho HJ, Zervos AS, Bonventre JV, Park KM (2010) Omi/HtrA2 protease is associated with tubular cell apoptosis and fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298(6):F1332–F1340. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00737.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klupsch K, Downward J (2006) The protease inhibitor Ucf-101 induces cellular responses independently of its known target, HtrA2/Omi. Cell Death Differ 13(12):2157–2159. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Takeyoshi I, Yoshinari D, Matsumoto K, Morishita Y (2002) P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury of the rat liver. Surgery 131(3):344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehotsky J, Burda J, Danielisova V, Gottlieb M, Kaplan P, Saniova B (2009a) Ischemic tolerance: the mechanisms of neuroprotective strategy. Anat Rec 292(12):2002–2012. doi:10.1002/ar.20970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehotsky J, Urban P, Pavlikova M, Tatarkova Z, Kaminska B, Kaplan P (2009b) Molecular mechanisms leading to neuroprotection/ischemic tolerance: effect of preconditioning on the stress reaction of endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Mol Neurobiol 29(6–7):917–925. doi:10.1007/s10571-009-9376-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liu N, Wang Y, Wang R, Guo D, Zhang C (2012) Inhibition of EphA4 signaling after ischemia-reperfusion reduces apoptosis of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neurosci Lett 518(2):92–95. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2012.04.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HR, Gao E, Hu A, Tao L, Qu Y, Most P, Koch WJ, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Alnemri ES, Zervos AS, Ma XL (2005) Role of Omi/HtrA2 in apoptotic cell death after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation 111(1):90–96. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000151613.90994.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XQ, Sheng R, Qin ZH (2009) The neuroprotective mechanism of brain ischemic preconditioning. Acta Pharmacol Sin 30(8):1071–1080. doi:10.1038/aps.2009.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Chen B, Li S, Yao J (2015) Dose-dependent neuroprotection of delta-opioid peptide [d-Ala, d-Leu] enkephalin on spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury by regional perfusion into the abdominal aorta in rabbits. J Vasc Surg. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.11.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R (1989) Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke; J Cereb Circ 20(1):84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Rau TF, Harris V, Johnson M, Poulsen DJ, Black SM (2011) Increased p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling is involved in the oxidative stress associated with oxygen and glucose deprivation in neonatal hippocampal slice cultures. Eur J Neurosci 34(7):1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Yang YP, Liu J, Li WH, Yang J, Sui X, Yuan X, Nie ZY, Liu YQ, Chen D, Lin SH, Wang YA (2014) Neuroprotective effects of madecassoside against focal cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Brain Res 1565:37–47. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz J, Thurmel K, Heemann U (2010) Anti-inflammatory treatment strategies for ischemia/reperfusion injury in transplantation. J Inflamm 7:27. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madinier A, Bertrand N, Mossiat C, Prigent-Tessier A, Beley A, Marie C, Garnier P (2009) Microglial involvement in neuroplastic changes following focal brain ischemia in rats. PLoS One 4(12):e8101. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmo AJ, Vink R (2009) Recent patents in CNS drug discovery: the management of inflammation in the central nervous system. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov 4(2):86–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo Devoto VM, Giusti S, Chavez JC, de Plazas SF (2008) Hypoxia-induced apoptotic cell death is prevented by oestradiol via oestrogen receptors in the developing central nervous system. J Neuroendocrinol 20(3):375–380. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux PP, Blenis J (2004) ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev: MMBR 68(2):320–344. doi:10.1128/mmbr.68.2.320-344.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen T, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Paetau A, Ijas P, Lindsberg PJ (2006) Apoptosis dominant in the periinfarct area of human ischaemic stroke—a possible target of antiapoptotic treatments. Brain: J Neurol 129(Pt 1):189–199. doi:10.1093/brain/awh645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawe N, Steinberg G, Zhao H (2008) Dual roles of the MAPK/ERK1/2 cell signaling pathway after stroke. J Neurosci Res 86(8):1659–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, Kong N, Ye L, Han W, Zhou J, Zhang Q, He C, Pan H (2014) p38 and JNK MAPK pathways control the balance of apoptosis and autophagy in response to chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Lett 344(2):174–179. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szydlowska K, Tymianski M (2010) Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium 47(2):122–129. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe K, Nishiyama T, Hayashi S, Hashimoto S, Fujishiro T, Kanzaki N, Kawakita K, Iwasa K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M (2011) Regulation of p38 MAPK phosphorylation inhibits chondrocyte apoptosis in response to heat stress or mechanical stress. Int J Mol Med 27(3):329–335. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2010.588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoufik E, Valable S, Muller GJ, Roberts ML, Divoux D, Tinel A, Voulgari-Kokota A, Tseveleki V, Altruda F, Lassmann H, Petit E, Probert L (2007) FLIP(L) protects neurons against in vivo ischemia and in vitro glucose deprivation-induced cell death. J Neurosci 27(25):6633–6646. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1091-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaibhav K, Shrivastava P, Khan A, Javed H, Tabassum R, Ahmed ME, Khan MB, Moshahid Khan M, Islam F, Ahmad S, Siddiqui MS, Safhi MM, Islam F (2013) Azadirachta indica mitigates behavioral impairments, oxidative damage, histological alterations and apoptosis in focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion model of rats. Neurol Sci 34(8):1321–1330. doi:10.1007/s10072-012-1238-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sun L, Xia C, Ye L, Wang B (2009) P38MAPK regulates caspase-3 by binding to caspase-3 in nucleus of human hepatoma Bel-7402 cells during anti-Fas antibody- and actinomycin D-induced apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother 63(5):343–350. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaidikar L, Thakur S (2015) Punicalagin attenuated cerebral ischemia-reperfusion insult via inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines, up-regulation of Bcl-2, down-regulation of Bax, and caspase-3. Mol Cell Biochem 402(1–2):141–148. doi:10.1007/s11010-014-2321-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates RB, Sheng H, Sakai H, Kleven DT, DeSimone NA, Stafford-Smith M, Warner DS (2013) Lack of evidence for a remote effect of renal ischemia/reperfusion acute kidney injury on outcome from temporary focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 27(1):71–78. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Guo L, Meng CY, Liu YJ, Lu RF, Li P, Zhou YB (2014) Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells exerts anti-apoptotic effects in adult rats after spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury. Brain Res 1561:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Katsu M, Sakata H, Okami N, Wakai T, Kinouchi H, Chan PH (2013) The role of PARL and HtrA2 in striatal neuronal injury after transient global cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33(11):1658–1665. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2013.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue T-L, Wang C, Gu J-L, Ma X-L, Kumar S, Lee JC, Feuerstein GZ, Thomas H, Maleeff B, Ohlstein EH (2000) Inhibition of extracellular signal–regulated kinase enhances ischemia/reoxygenation–induced apoptosis in cultured cardiac myocytes and exaggerates reperfusion injury in isolated perfused heart. Circ Res 86(6):692–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Liu J, Shi JS (2010) Anti-inflammatory activities of resveratrol in the brain: role of resveratrol in microglial activation. Eur J Pharmacol 636(1–3):1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H-J, Deng Y-L, Su D-Y, Yang S-C, MA J (2011) The Effect of UCF-101 on the expression of apoptosis inhibitor protein XIAP during focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Prog Anat Sci 3:223–226 [Google Scholar]