Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ulva, Ulvan, Seaweed, Carbohydrates, Enzyme, Ultrasound

Highlights

-

•

Ulvan extracted with Cellic® CTEC3 enzyme mix enhances yield and preserves quality.

-

•

FTIR and NMR confirm sulfation and ulvan structure preservation.

-

•

Ultrafiltration yields 93% ulvan concentrate with 55% carbohydrate content.

-

•

Low Na+:K+ ratio and high Mg2+ content support ulvan’s potential for healthy diets.

-

•

Ulvans exhibit biopolymeric behavior and form weak but stable gels.

Abstract

Sea lettuce, or Ulva spp., dominates global algal biomass and significantly contributes to “green tides.”, representing a sustainable source for biomaterials. This study explores an innovative ultrasound-enzyme assisted extraction method with the novel Cellic® CTEC3 enzyme cocktail, applied for the first time in Ulva spp. succesfully enhancing ulvan release and extraction efficiency. Various processing methods, including ultrafiltration and dialysis, were employed to achieve higher ulvan purity. Dialyzation of ulvan resulted in a more purified product with a carbohydrate content up to 55.34 %, a sulfate content up to 21 %, and no glucose contamination. Liquid extracts were fractionated through ultrafiltration, with a 3 kDa MWCO yielding 93.51 % ulvan precipitate, representing 50.28 % of the total extractable ulvan. Sequential ultrafiltration concentrated ulvans but only partially modified their molecular weight distribution. Depolymerization using microwave and H2O2 shifted ulvans towards lower molecular weights, reducing high molecular weight residue. HPSEC confirmed pH-dependent aggregation behavior, with all isolated ulvans having molecular weights above 786 kDa. Hydrolysis methods were compared, with 2-hour 1 M TFA hydrolysis at 121 °C providing the best monosaccharide profile of ulvan. FTIR and NMR analyses showed preservation of sulfation. Rheology indicated biopolymeric behavior and stable gel formation. Ulvans demonstrated nutraceutical potential, being suitable for a low Na+ and high K+ diet, with a Na+:K+ ratio as low as 0.14, and were rich in Mg2+.

1. Introduction

Seaweeds require structural flexibility to withstand physical and biotic stress. To achieve this adaptability, they employ a combination of rigid components, such as cellulose fibrils, proteins and a mucilage matrix, primarily composed of linear and bioactive sulfated polysaccharides. These soluble polysaccharides vary in their structure, not only depending on algal species, but also eco-physiological origin and exact life stage [1], [2], [3], [4]. The main representatives of sulfated polysaccharides in green seaweeds (Chlorophyta) are ulvans [5]. Ulvans are gaining popularity for use in their native form or after chemical modification due to their unique characteristics of biocompatibility and biodegradability. These inherent qualities make them highly valued as essential ingredients in biomaterials and provide them with a big potential in the biomedical field [6], as carrier systems in drug delivery or tissue engineering, or directly as medical bioactive products. In fact, sulfated polysaccharides are considered safer and non-immunogenic, compared to sulfated polysaccharides of animal origin as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) [7]. In addition, biopolymeric matrices based on these polysacccolouharides integrate well in GAGs native environments, as it is the extracellular matrix, showing potential as wound dressings [8], [9].

Ulvan, obtained from green seaweeds as Ulva spp., is one of the less investigated sulfated polysaccharides, but also one of the most promising, due to its ease of cultivation and abundance [10]. Ulva spp. is involved in “green tides”, or macroalgal blooms, which occur in coastal eutrophicated areas, with an ecologically concerning impact [11]. Thus, there is a huge potential to exploit and transform this underutilized and pollutant biomass as a source of new and valuable biomaterials through innovative extraction and processing [12].

Ulvan is mainly composed by disaccharides units, with rhamnose, glucuronic acid, xylose and iduronic acid as main constituents [13]. These constituents are mainly integrated in two types of ulvanobiuronic 3-sulfate acids: A3s [⟶4)-β-D-GlcA-(1⟶ 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] and B3s [⟶4)-α-L-IdoA-(1⟶ 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶]. Rhamnose residues bear sulfation at C-3 or both C-2 and C-3. Less frequent variations include ulvanobiose acids consisting of rhamnose with xylose [⟶4)-β-D-Xyl-(1⟶ 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] or sulfated xylose [⟶4)-β-D-Xyl 2S-(1⟶ 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] (U3s, U2′s,3s, respectively) [14], [15], [16]. Minor amounts of galactose, arabinose, glucose, and mannose are also reported, though their precise role and position in the ulvan structure is uncertain [5], [17]. However, ulvan does not appear to form long chains with the same repeating unit. Moreover, its heterogeneous chemical structure shows a disordered, slightly branched, biopolymeric conformation without a defined backbone and varying degrees of sulfation [5], [13].

Ulvan has recently emerged as a promising biomaterial for hydrogels, 3D porous structures, nanofibers, and nanoparticle formulations. Its applications extend to wound dressing, drug delivery, or tissue engineering/regeneration [8], [13]. Further, this sulfated heteropolysaccharide has demonstrated anti inflammatory [18], anticoagulant [19], antioxidant [20], anticancer [21], immunomodulating [22], antiviral [23], antibacterial [24], and antihyperlipidemic [25] effects. Yield, molecular weight distribution, rheological or textural properties, and chemical composition, are contingent on extraction conditions [26]. However, existing extraction methods yield low quantities and with suboptimal mechanical properties [27], [28].

Ulvan yield is influenced by various factors, including ecophysiological conditions, species, harvest time, storage, as well as extraction and purification methods [27]. Ulvan extraction is typically conducted in aqueous solutions at temperatures ranging 80–90 °C. To overcome the crosslinking of ulvan in the cell wall, acids or divalent cation chelating agents are often added as extractants [27], [29]. Higher temperatures and lower pH levels contribute to depolymerization and desulfation [30], [31], [32]. These degradation processes may either enhance or diminish the functionality of ulvan, depending on its intended application. Preventing degradation helps in the obtention of a more versatile product that can be easily degraded if needed for specific uses [27]. Enzyme or ultrasound assisted extractions, when compared to conventional methods, rely on fewer chemical reagents, imply shorter processing times and can offer high yields at lower temperatures, which reduces energy consumption and minimizes product degradation [33], [34].

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to explore different ulvan obtention pathways primarily aimed at obtaining ulvans through novel enzyme-ultrasound combined extraction and ultrafiltration processing techniques. This involved testing a novel commercial enzyme cocktail applied for the first time to this biomass. Furthermore, the study aimed to assess the varying quality and purity levels of the extracted ulvans, its physico-chemical properties, along with their rheological features when formulated as gels. Additionally, different depolymerization assays were conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the structure and aggregation behaviour of these polysaccharides and providing insights into methods for obtaining low-molecular-weight ulvans.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Raw materials

A dry mixture of different laminar Ulva species, mainly comprising Ulva lactuca, were kindly provided by Porto-Muíños S.L. (A Coruña, Spain). Samples were milled using an A320 chopper (Moulinex, Spain), to a particle size bellow 0.5 cm. Algae specimens were prepared for analysis and extraction treatments by chopping them into uniform fragments measuring approximately 1–2 cm in length.

2.2. Ultrasound-enzyme-assisted extraction

Ultrasound-assisted extraction was conducted using a ultrasonic bath (Fisherbrand Scientific, FB11207) set at 100 %, 80 kHz frequency, amplitude, 1130 W power, and a constant temperature of 55 °C (modified from Torres et al. [35]). Residual solid phase was sepparated through membrane vacuum filtration (0.45 μm). Enzyme-assisted extraction was performed using a Cellic® CTec3 enzyme complex, kindly provided by the Novozymes company (Denmark). This complex has cellulase, hemicellulase and beta-glucosidase activity, and is often used for the treatment of lignocellulosic materials [36]. The enzyme activity was measured at 183 FPU/mL, using Whatman No. 1 filter paper during the filter paper assay. A dose of 300 μL of Cellic® CTec3 enzyme complex was added per g of dry seaweed based on preliminary assays aimed to improve extraction yields. All extraction parameters were adjusted to T = 55 °C, pH = 5.6, 300 mM NaCl and 50 mM acetate buffer, simmilarly to reported elsewhere [37], in reactions containing a 1:30 solid–liquid ratio as performed by André et al. [38]. The reactions were stopped by heating up to 95 °C for 5 min.

2.3. Dialysis and membrane fractionation

Ulvan precipitates were resuspended to a final concentration of 1 % (w/w) to be dialyzed for one week using a Float-A-Lyzer®G2 Dialysis Device, with a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 100–500 Da (Spectrum Laboratories, USA).

Ulvan-rich extract obtained via US-enzyme assisted extraction (LFB) was concentrated through ultrafiltration using an Amicon ultrafiltration device (USA) under N2 pressure, employing membranes with MWCOs of 1, 3, and 10 kDa for selective separation. The liquid phase was initially diluted with distilled water and sequentially filtered through membranes, starting with the highest MWCO, until reaching a volume concentration ratio (VCR) of 10 in the retentate phase. Subsequently, the permeate underwent the same process using the next highest MWCO, and so forth, yielding fractions categorized by MWCO ranges of >10 kDa, 3–10 kDa, 1–3 kDa, and < 1 kDa.

2.4. Depolymerization assays

Microwave assisted depolymerization of ulvan was performed using an Anton Paar Microwave reactor Monowave 450 (Austria). Samples were dissolved in water with a final concentration of 5 mg/mL and H2O2 was added at a final concentration of 1.5 %, modified from procedures reported elsewhere [20], [39], [40]. In all cases, the samples were heated during 20 min up to 160 °C, with a power of 850 W. Agitation speed was set at 800 rpm. Acid depolymerization assays were performed using 0.1 M HCl, in a 10 min treatment, in agitation, adjusted to pH = 3.

2.5. Characterization of raw material and solid products

Scanning electron microscopy (JEOL JSM6010LA, Japan) was used to analyze microstructural morphology of raw material and solid residues after extraction treatments. Images were obtained at different magnifications.

The contents of heavy metals (As, Se, Pb) were determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Optima 4300 DV, PerkinElmer, USA), while the mercury (Hg) content was measured using cold vapor atomic absorption spectrometry.

Some of shown elemental and mineral values are based on [38]. Macroelements were measured using atomic emission spectrophotometry for Na and K, or atomic absorption spectrophotometry for Ca and Mg, employing a 220 Fast Sequential Spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). For C content determination, an elemental analyser (Thermo Flash EA 1112, Germany) was utilized under specific conditions: He gas flow of 130 mL/min, reference gas flow of 100 mL/min, oxygen flow of 250 mL/min, an oxidation furnace temperature of 900 °C, and a reduction furnace temperature of 680 °C. A 2.0 m, 6 × 5 mm multiple analysis column (Cromlab, Spain) was used, with the temperature set at 50 °C and a chromatogram time of 420 s. Aspartic acid (Sigma, USA) was employed as a calibration standard. Total N was measured using the Kjeldahl method, results were converted to protein content using a specific conversion factor of 5.65 for Ulva spp. [41], as this algae was supposed to be the main constituent of the used biomass.

Higher heating values (HHV) of solid products were carried out using the nitrogen (N), hydrogen (H) and carbon (C) content measured experimentally, which were introduced to the equation given bellow:

| (1) |

A Minolta CR-400 (Japan) colorimeter was used for colour measurements. Results were expressed in the CIELab system defined by L*, a* and b* as chromaticity responsible parameters. Samples were measured at least ten times, always at room temperature and identical light conditions.

2.6. Characterization of liquid fractions

Various analyses were conducted on the liquid phase obtained from ultrasonic (US) and/or enzyme-assisted extractions. Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method [42]. The antioxidant capacity of the analysed extracts was assessed using two different methods: the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) assay [43] and the ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assay [44]. Soluble protein content was determined using the Bradford method [45]. Soluble sulfate content was determined using the gelatine-barium chloride method [46]. Total lipid content was determined according to the Folch method [47]. The pH was determined under consistent stirring and at room temperature using a Crison GLP-21 instrument (Spain). Electroconductivity (EC) measurements were carried out using a HI 8633 Hanna electroconductivity meter (Spain). All samples were always measured at least in triplicate.

2.7. Characterization and processing of ulvan fractions

2.7.1. Polysaccharide recovery and yield

Ulvan fractions were isolated from the liquid phases by precipitation with 96 % ethanol (at a ratio of 1:1.5). Afterwards, precipitates were washed under constant stirring in ethanol for 30 min when necessary. The ethanol precipitate was dried at 50 °C until constant weight and then ground to powder. Ulvan extraction yield was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

2.7.2. Monosaccharide composition

Monosaccharide composition of ulvans was determined by HPLC after three different acid hydrolysis treatments of ulvans of increasing intensity. In all cases, extracted ulvans were dissolved to 2 mg/mL and dialyzed (100–500 Da MWCO) for one week prior to analysis.

One treatment involved the addition of 4 % H2SO4 to the samples, which were then incubated at 121 °C during 20 min, in an autoclave. The second method involved trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), based on Wang et al. [48] with some modifications, where an aliquot of the dialyzed sample was mixed with the same volume of 2 M TFA, resulting in a final concentration of 1 M TFA and submitted to 121 °C for 1 or 2 h in an autoclave. The third method added a second hydrolysis step to the latter treatment, with 2 M TFA during 1 h and same conditions. In all cases, mixtures were transferred to the autoclave in oven-dried Pyrex tubes. After the hydrolysis treatment, samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter, and finally measured on a chromatograph.

In case of experiments involving TFA, the solution was vacuum rotavapored until complete evaporation of the acid and samples were then redissolved to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL with water, prior to be injected into the HPLC equipment. An Aminex HPX-87H or a HPX-87P column (both 300 × 7.8 mm, BioRad, CA, USA) were used, operating at 60 °C, with a mobile phase of 0.003 M H2SO4 (w/w) at 0.6 mL/min, or operating at 80 °C with a mobile phase of MilliQ water at at 0.6 mL/min, respectively. The HPLC equipment had a refractive index detector. Samples were measured at least in triplicate.

2.7.3. Structural characterization

Molecular weight distributions of the samples were assessed using High-Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HPSEC) with an Infrared (IR) detector-equipped High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent). A TSKGel Super-Multipore PW-H column (6 × 150 mm) along with a TSKGel guard column SuperMP(PW)-H (4.6 × 35 mm), from Tosoh Bioscience (Germany) were used. The mobile phase consisted of Milli-Q water at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Poly(ethylene oxide) standards with molecular weights ranging from 2.36 × 104 to 7.86 × 105 g/mol (Tosoh Bioscience, Japan) were utilized for calibration.

Fourier transform infrared attenuated total reflectance (FTIR-ATR) analysis was carried out for the qualitative examination of ulvans, employing a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer (Fisherbrand Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada) with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 and a scanning rate of 32 scans per minute, all measurements were conducted at room temperature. The acquired FTIR spectra ranged from 400 to 4000 nm.

Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (H-NMR) spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker ARX400 spectrometer, operating at 75 °C and a magnetic field strength of 400 MHz. Deuterium oxide (D2O) was employed as the solvent. For the quantification of the biopolymeric fraction, 3-(trimethylsilyl)-L-propane sulfonic acid (Sigma Aldrich, USA) was used as an internal standard, following the methodology outlined in a previous study [49]. A standard phycocolloid concentration of 10 mg ml−1 in D2O was employed. All spectra were processed and analyzed using MestreNova software (Spain).

For the determination of proton‑carbon single bond correlations, bidimensional NMR (HSQC, Heteronuclear single quantum coherence) spectroscopy was performed, using an Avance DPX600 spectrometer (Bruker, Massachusetts, USA), operating at identical conditions as H-NMR. 3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propane sulfonic acid (TMS-PSA, Sigma Aldrich) and deuterium oxide (D2O) were used as internal standart and solvent, respectively.

2.8. Rheological assays

Dispersions of increasing concentrations (0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2 %) were prepared for different ulvans for thermo-rheological characterization. Gel-forming solutions were formulated by dissolving dried ulvan extract (3 %, w/v) in distilled water at temperatures ranging from 50 to 70 °C with continuous stirring. The viscoelastic properties of these samples were measured using a MCR302 controlled-stress rheometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria). Small amplitude oscillatory shear measurements were conducted at 5 Pa within the linear viscoelastic region (< 10 Pa), using a sand-blasted parallel plate of 25 mm diameter (1 mm gap). Measurements were controlled at 25 °C using a Peltier system. All samples were rested 5 min and covered with light paraffin oil previously to the rheological testing.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and graphical representations were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Differences between means were assessed using Student's t-tests, with statistical significance established at p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Schematic procedure of extraction and processing

Starting with Ulva spp. as raw material, different products were obtained to be characterized and tested as biomaterials for the formulation of gels. The final products were always processed to dry powders, to allow a correct preservation. In each extraction process, various streams were generated. Flow diagrams illustrating the experimental procedures are represented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of preliminary extraction configurations for ulvan obtention with ultrasound and or enzyme-assisted extraction. T.1 and T.2 correspond to a 60 min treatment with or without Cellic® CTec3 cellulase-hemicellulase enzyme mix, respectively; T3 and T4 correspond to a 90 min treatment, also with and without the same enzyme mix.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram illustrating various ulvan obtention pathways, based on the best yielding preliminary treatment (T.3), showing experimental procedures and different processing pathways with corresponding mass balances. BP-3B-R10, BP-3B-R3 and BP-3B-R1, refer to ulvan precipitated from retentate fractions of > 10, 3–10, and 1–3 kDa (MWCOs), respectively.

Ulva spp. was firstly submitted to four different US-assisted extractions. Two different extraction times (60 and 90 min) were compared, in presence or absence of the commercial Cellic® CTec3 cellulase-hemicellulase enzyme mix (Fig. 1). After identifying treatment 3 as the most effective one, this stream was chosen for further processing experiments (Fig. 2). A primary focus was placed on the extraction of ulvan biopolymer (BP-3A and B), which was subsequently characterized and further used in experiments.

The obtained liquid fraction contained a multitude of solubilized compounds, necessitating further separation downstream. For this purpose, different processing pathways with corresponding mass balances are summarized in Fig. 2. On the one hand, a direct ethanol precipitation method (Option A) was employed, resulting in an ulvan extract rich in pigments which was ethanol-washed to increase purity (BP-3A). Alternatively, a centrifugation step facilitated the separation of a pigment-rich fraction as pellet, alongside a supernatant containing ulvan (Option B), to get a cleaner biopolymeric product (BP-3B). Centrifugation could also be substituted by a slower passive sedimentation procedure for one week, achieving a similar result with a clean supernatant and a pellet rich in solids and pigment, although some ulvan deposition also occurs due to cold precipitation. The supernatant of Option B underwent two alternative paths for further processing. In Option B-1, direct ethanol precipitation was employed, yielding a cleaner ulvan (BP-3B) compared to BP-3A, obviating the need for an ethanol washing step. Alternatively, Option B-2 involved membrane fractionation via ultrafiltration, employing selected cut-offs to obtain different ulvan retentates. Retentate fractions of >10, 3–10, and 1–3 kDa were subsequently precipitated, resuspended and dialyzed. Note that mass balances of Fig. 2 did not yield the exact mass at the end of the process, due to some losses in the liquid streams during the extraction and processing steps, particularly in the ethanol washing and dialysis, which reduced final mass sum.

3.2. Microstructural effect of ultrasound-enzyme extraction on the raw material

Surface Electron Microscopy (SEM) was utilized to examine the impact of US and enzymatic treatment on the microstructure of Ulva spp. biomass. Micrographs are presented in Fig. 3. The live cells of Ulva spp. present various shapes, including oval, triangular, quadrilateral, pentagonal or polygonal [50]. In the case of dehydrated samples, depicted in Fig. 3A-B, the cells undergo a central collapse, resulting in a concave, shrunken, appearance. Despite the rough surface morphology, the cellular contours remain distinguishable. Similar shape in dry samples of Ulva rigida were observed [51].

Fig. 3.

Surface morphology of Ulva spp. a-b) show dehydrated Ulva spp. samples, c-f) show solid residues after ultrasound treatment without (c, d) or with (e, f) simultaneous Cellic®CTec3 digestion.

The surface topology of Ulva spp. solid residues after US treatment (Fig. 3C-D) depict a well-preserved tissue structure, with discernible individual cells and a smoother surface compared to non-treated Ulva spp. Again, slight cell shrinkage is observed, consistent with previous findings on more intense microwave treatments applied to Ulva spp., as reported elsewhere [38], where higher temperatures resulted in greater shrinkage. Fig. 3E-F display the microstructural impact of the combined US-Ez treatment. The micrographs reveal a homogeneous appearance, indicating the complete disintegration of the tissue structure following enzymatic cell wall digestion. The remaining components appear to have fused together, forming a laminar, stacked conglomerate that bears a resemblance to the morphology observed in alkaline treatments of Ulva spp., as reported in studies [52], [53], where a simmilar degradation of algal cell wall after an alkaline treatment was clearly observed through SEM. Thus, our findings show that the enzymatic digestion using Cellic®CTec3 successfully disrupted the cell wall structures of Ulva spp.

3.3. Efficacy of Cellic® CTEC3 enzyme cocktail in ultrasound-assisted ulvan extraction

Ulvan is a sulfated polysaccharide that physically constitutes the water-soluble portion of the polysaccharide biomass, and which is held within the structure of the cell wall [54]. Thus, the proposed extraction methods targeted the disruption of the cell wall while using water as only solvent. Ultrasound-assisted extraction is a non-thermal technique based on the formation of cavitation bubbles, that grow and collapse, causing high shear pressure which disrupts cell walls while reducing particle size of the samples, allowing a more efficient contact with the solvent [55], [56]. The Cellic® CTEC3 enzyme complex specifically targets the (hemi-)cellulosic structure of the biomass, which loosens the cell wall and should aid in releasing soluble ulvan into the aqueous solution. Alternatively, acid conditions along with calcium sequestering agents such as EDTA or oxalic acid are conventionally utilized for this purpose [26], [31], [57].

Fig. 1 illustrates how yields revealed a substantial increase both when utilizing the enzyme mix and extending the extraction time. Optimal ulvan extraction occurred using Cellic® CTec3 enzyme mix and a 90-minute extraction (BP-3A), giving a yield of 32.18 ± 1.69 % ethanol-washed ulvan precipitate (treatment 3). During these preliminary ulvan extraction assays, temperature and pH were adjusted to the enzyme optimum (T = 55 °C, pH = 5.6, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM acetate buffer).

Our results show that enzyme mix works in standard conditions with water, but yielding significantly lower values than the optimized solution (pH = 5.6, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM acetate buffer), as shown in Fig. 4. The adjustment of the extractive solution to the enzyme conditions increased signifficantly its effectiveness when compared to the use of water, obtaining values of 37.22 ± 0.46 % and 32.72 ± 0.15 %, respectively, for non-dialyzed samples; and 24.53 ± 0.34 % and 21.57 ± 0.11 %, respectively, for dialyzed samples. Interestingly, 7.46 % of the extractable ulvan from the centrifuged US-enzyme extract (BP-3B) can be obtained without the addition of ethanol, utilizing a slow precipitation step over one week at 4 °C, as illustrated in Fig. 4 (“cold precipitation without ethanol”). Ethanolic precipitation similarly benefits from extended precipitation times at low temperatures: the ethanolic precipitate increased by 22 % with the inclusion of a cold precipitation step lasting at least 12 h at 4 °C (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Ulvan extraction yields from treatment 3 (BP-3B) with centrifugation prior to precipitation, comparing dialysis, enzyme medium, and water extraction solutions. The inset white box in the non-dialyzed ulvan indicates cold-precipitated ulvan. Different letters denote significant mean differences; error bars represent standard deviations.

Rahimi et al. [58] pointed out optimal US-assisted extraction conditions at 66 °C, liquid:solid ratio of 50:1 (which was the highest concentration ratio tested), and pH 7 (lowest pH tested), with a maximum yield of 8.3 %. Comparatively, the approach of this study increased the concentration ratio to 30:1, and worked with lower temperatures (55 °C) adjusting to the enzyme requirements. Unlike the findings of the mentioned study, which demonstrated no increase or a diminishing yield beyond a 30-minute US-assisted extraction, this study reveals a notable enhancement in the extraction yield from 60 to 90 min. On the other hand, Guidara et al. [59] obtained a yield of 17.95 % (w/w), with combined enzymatic and chemical extraction. Wahlström et al. [60] obtained a yield of 18 ± 2 % through acidic extraction, and 11 ± 3 % when using water extraction. It is worth noting that the dry weight percentage of total ulvan content in Ulva is quantified up do 30–36 % [12], [27].

In this line, our results show that enzymatic treatments, like the use of Cellic® CTec3, offer a promising approach for ulvan obtention, reducing energy consumption and waste generation compared to chemical treatments. However, ulvan products contained certain impurities (as discussed in section 3.7.2) that may not be present when using extraction methods with very low pH. Additionally, challenges arise in scaling up enzymatic processes due to high costs and reaction times, often necessitating a combination of enzymatic and chemical treatments [61]. In comparison, hydrochloric acid-based extraction offers a faster, one-step process with higher yields than multi-step water-based methods, although implying both energy costs and waste disposal. Furthermore, this method generates by-products as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and furfural, originated from the dehydration of hexoses and pentoses under acidic conditions [61]. However, water-based extraction yields a purer ulvan fraction with higher sulfation rates, which is preferred for biomedical applications. The choice between acid-based and water-based extraction depends on the intended application of ulvan [60].

3.4. Fractionation and obtention of ulvan-rich extracts by ultrafiltration

Pore size selection impacts both ulvan retention and the rate of permeate flow, with smaller pores slowing the ultrafiltration process. Optimal balance is recommended at approximately 10 kDa [27]. In this study, this was the highest tested size, with three sequential MWCOs, 10 kDa, 3 kDa, and 1 kDa, were used to fractionate the liquors from Option B (Fig. 2), as shown in Fig. 5A. This resulted in six fractions, each with distinct dry weight, pH and EC (Fig. 5C). Further purification of the fractions through dialysis enabled the removal of salts (Fig. 5A). Notably, while the values for BP-3B-R10 remained unchanged, BP-3B-R3 and BP-3B-R1 showed significant changes. Specifically, BP-3B-R3 decreased from 52.90 ± 0.71 g/L in non-dialyzed ulvan to 40.77 ± 0.12 g/L in dialyzed ulvan, and BP-3B-R1 decreased from 32.20 ± 0.85 g/L to 18.69 ± 0.48 g/L, respectively, while maintaining the same volume. This suggests that these downstream fractions contained higher salt contents.

Fig. 5.

A. Flow diagram of membrane fractionation. B. Percentages of precipitated ulvan showing ulvan in fraction relative to d.w. of fraction (in black) or relative to total extractable ulvan from the liquid extract (in grey) or ulvan yield relative to dry weight of Ulva spp. (in white). Different letters indicate significant differences among means of the same group. Bars indicate standard deviation. C. Ethanol-precipitated ulvan from different fractionated liquors, illustrating successful fractionation of ulvans. R: retentate, P: permeate.

The highest dry weight (4.47 %) and ulvan yields were in the 3–10 kDa fraction (R3), followed by 1–3 kDa (R1) and >10 kDa (R10) retentate fractions, as shown in Fig. 5C. As shown in Fig. 5B, 93.51 ± 1.58 % of ulvan precipitate, relative of the dry weight of the fraction, were obtained for R3, which corresponded to 50.28 ± 0.84 % of the total extractable ulvan from the liquid extract. Comparatively, R10 and R1 resulted in 62.45 ± 2.89 % and 59.77 ± 3.19 % of ulvan relative to d.w. of fraction, respectively, and only retained 20.45 ± 0.95 % and 17.02 ± 0.91 % of extractable ulvan, respectively. These results also indicate that a 3 kDa membrane is the optimal MWCO for concentrating ulvan from the generated US-enzyme extract. However, the 10 kDa retentate might have the advantage of not requiring a dialysis step.

It is important to note that the molecular size ranges are based on the pore size of the used membranes, which may not accurately reflect the actual sizes of the ulvans within the fractions. Ulvans could fit through larger-sized pores due to their chain conformation, or be hindered due to potential aggregation dynamics, as commented in section 3.6 [31]. This makes it difficult to accurately determine the true sizes of ulvans present in these fractions, so given results should be taken with care. For scaled-up purification, discontinuous diafiltration is common, involving continuous dilution with a diafiltrate buffer [62]. Our preliminary assay used a two-step purification approach: concentration to reduce volume and increase retentate concentration, followed by dialysis to reduce salt content. These findings can serve as a basis for further scaling-up.

3.5. Molecular size of ulvan, aggregation and depolymerization assays

Enzymatic digestion of (hemi-)celluloses of Ulva spp. with the moderate physical extraction conditions of US-treatment, resulted in extremely high molecular-sized ulvan, as shown in HPSEC spectrum of Fig. 6B, where BP-3B is referred to as “Control”. BP-3B was subjected to degradation processes to obtain lower molecular weight ulvans. The untreated ulvan displayed a broad molecular weight distribution, in accordance with previous studies [26], [38], [59], with a smaller shoulder near the 786 kDa standard, showing similarity with the typical second peak seen in ulvan HPSEC spectra [26], [63]. The molecular size exceeded 786 kDa, higher than reported elsewhere [60], but in the range of values reported for this polysaccharide, between 530 and 7700 kDa [64].

Fig. 6.

Molecular size distributions based on HPSEC analysis. A: HPSEC spectra of membrane fractions with mobile phase at two different pH. B: HPSEC molecular size distributions of ulvan submitted to various degradation assays. Control: Ulvan BP-3A submitted to no treatment; Acid: pH = 3, t = 10 min; Microwave: 200 °C, H2O2 2 %, t = 20 min; pH of mobile phase = 3.

Low molecular weight ulvans are more bioactive and can be obtained via hydrolysis methods [27], [65], [66]. Chemical hydrolysis is cost-effective but lacks control over polymerization degree and may produce undesired compounds [67]. Physical techniques like microwave-assisted depolymerization with chemical method of H2O2 depolymerization offer a controlled reduction in molecular size and uniform extraction.

More severe extraction conditions, namely acid or alkaline extractions, may result in smaller molecular sizes due to partial hydrolysis and depolymerization of the chains [13], [30] which also show altered chemical properties due to hydrolysis of functional groups, or may yield high molecular sizes due to a stronger disruption of the biomass and consequent liberation of larger sized ulvan chains. Mild extraction conditions, often performed with water as only solvent, generally result in smaller sized ulvans but with more conserved chemical profiles (e.g. sulfation pattern) [60].

Acid treatment (10 min at pH = 3 adjusted with HCl) shifted ulvan to lower molecular weights, whereas 20 min microwave-assisted depolymerization treatment with 2 % H2O2 led to more complete degradation. Combination of these methods further reduced size. Treated ulvans probably show a more neutral behavior than untreated ulvan, due to cleavage of sulfate from the chain, and could therefore have a different behavior in HPSEC. These results are in accordance with [26], who obtained a enzymatic and chemically extracted ulvan, with high molecular weight, while acid extractions yielded lower molecular sizes.

Bellow the pKa of glucuronic acid (3.28) carboxylate groups should be protonated while sulfate esters remain ionized. Robic et al. [31] demonstrated that these conditions resulted in the dispersion of aggregates into free condensed bead-like conformations. In Fig. 6A, we tested the behaviour of ulvans in a mobile phase with a pH 3 acetate buffer during HPSEC analysis, comparing it to their behaviour in an almost neutral pH environment. We examined various ulvan fractions obtained from membrane ultrafiltration, specifically > 10 kDa (BP-3B-R10), 3–10 kDa (BP-3B-R3), and 1–3 kDa retentate (BP-3B-R1). It is important to note that these values correspond to the membrane MWCOs and not the actual Mw of the ulvans. The results indicated a decreased Mw at pH = 3 compared to pH = 6.9 across all samples, with smoother peaks suggesting probable pH-driven aggregation and disaggregation. Additionally, at pH = 6.9, BP-3B-P3 and BP-3B-P1 exhibited peaks at larger molecular sizes, while at pH = 3, a clear shift to smaller molecular weights was observed, indicating disaggregation of the ulvans.

Both spectra of Fig. 6A revealed a distinct molecular weight profile for the BP-3B-R1 ulvan, characterized by a shoulder shifted towards the lower Mw region, which was more defined at pH = 3. However, BP-3B-R10 still conserved a peak at the high molecular weight region. In contrast, BP-3B-R10 and BP-3B-R3 did not show clear differences.

These findings suggest that sequential ultrafiltration did not effectively separate fractions based on different molecular weights, only partially contributing to altering the proportion of molecular weights in case of BP-3B-P3, BP-3B-R1 and BP-3B-P1 ulvans. Comparatively, depolymerization experiments showed in Fig. 6B involving acid and microwave with or without H2O2 treatments, did show cleaner shifts to LMW ulvans, with less HMW residue, although membrane fractionation permitted the partial concentration of smaller molecular weights.

HPSEC analysis faces challenges like ulvan self-aggregation and ionic interactions with the stationary phase impacting peak clarity [8], [68]. Aggregation occurs due to ionic interactions and presence of divalent cations [31], [69]. In addition, the utilized calibration standards, namely polyethylene glycol and dextrans, possess a neutral charge and may exhibit distinct hydrodynamic volumes and interactions with the solvent [70]. Ulvan, being a branched anionic polysaccharide, likely demonstrates varied affinities to the eluent, with a hydrodynamic volume which cannot be directly compared with the standards. The derived values should be regarded as estimates. However, internal comparisons remain feasible [71]. The aggregation of ulvan polysaccharide, acting as a polyelectrolyte, is likely the main reason for the significant variation in molecular weight reported by different techniques in the literature [27], [64].

3.6. Helix–coil transition analysis

Data in Fig. 7 depict the helix–coil transition analysis of BP-3A and BP-3B in the presence of different NaOH concentrations, as representative of tested ulvans. Polysaccharides adopting a triple-helix structure can complex with Congo red reagent under weak alkaline conditions, causing a redshift in λmax compared to Congo red alone. Higher NaOH concentrations lead to triple-helix denaturation due to increased charge density, resulting in electrostatic repulsion and subsequent conversion to single or double helix structures. Our results show a significant λmax increase at low NaOH concentrations, suggesting a need for minimal alkali for complex formation. While triple helices induce the redshift, other helical conformations may also contribute. Aggregation of the polyelectrolyte could also explain why high NaOH concentration do not cause expected triple-helix denaturation. Even without stable or obvious transition regions, a substantial redshift implies triple-helix involvement [72]. In both BP-3A and BP-3B, the observed shifts in the helix-coil transition were comparable, suggesting that the molecular structures contributing to this behavior are similar.

Fig. 7.

Helix-coil transition analysis of the BP-3A and BP-3B ulvans in presence of different NaOH concentrations.

3.7. Antioxidant capacity and total phenolic contents of liquid extracts and ulvan fractions

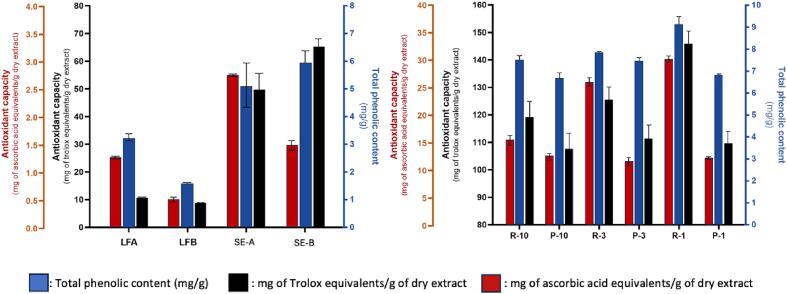

The phenolic content of the liquid fractions and the saline extracts is low (Fig. 8), but in the range of those found for hydrothermal processing of the same seaweed [73]. The values were also comparable to those reported for ulvan and bioactives from other species using other extraction technologies, such as Ulva linza with oxalic acid extraction [74], Ulva rigida with ultrasound assisted aqueous extraction [75] or from Ulva lactuca with pulsed electric fields [76]. Differences in bioactivity of analyzed fractions could be related to ulvan concentration (retentates show higher bioactivity values than permeates), and molecular size, as 1–3 kDa MWCO fraction (R1) showed increased bioactivity compared to 3–10 and >10 kDa MWCO fractions (R3 and R10, respectively). The presence of reducing ends and sulfation can significantly influence the antioxidant behavior of ulvan [20], modifying the reducing capacity of the solution, and thereby impact the measurements of antioxidant capacity and phenolic content.

Fig. 8.

Antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content of obtained liquors (left) and fractions (right). LFA/B: Liquid fraction from processing option A or B. SE-A/B: Saline extract from processing option A or B. R: Retentate, P: Permeate; 10, 3 and 1 kDa MWCOs. Bars represent standard deviations.

As expected, the reducing power and antiradical properties could be strongly dependent on the phenolic content (Fig. 8) and should be considered for further valorization of these byproduct streams.

3.8. Chemical composition of the obtained products

General chemical composition of the starting biomass and of main obtained products is illustrated in Table 1. Ulva spp. composition is based on values reported in previous studies with the same biomass [73] and is in the range of values reported in literature [14], [77], [78]. Minerals and proteins are known to be strongly associated with polysaccharides in the cell-wall [15], and are therefore naturally present in the starting biomass, which showed an ash content of 22.53 ± 0.45 % and a protein content of 10.31 ± 0.22 %. The solid residue (SR) of the extractions showed high protein content of 17.09 ± 0.12 % significantly higher than the starting material. Note that the increased ash content of non-dialyzed obtained products is influenced by the addition of NaCl in the US-enzyme extraction medium.

Table 1.

General composition of the raw material and obtained solid products. SR refers to solid residue from the ultrasound-enzyme assisted extraction. SE-A and SE-B correspond to the liquid extracts remaining after ulvan precipitation from the mentioned streams. BP-3A and BP-3B correspond to ulvans precipitated from a non-centrifuged or centrifuged US-enzyme extract, respectively. nd- and d- prefixes indicate non dialyzed and dialyzed samples, respectively. AIR indicates acid insoluble residue.

| Content (%, d.w.) | Ulva spp.* | SR | SE-A | SE-B | nd-BP-3A | nd-BP-3B | d-BP-3B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfate-free ash | 22.53 ± 0.45a | 30.56 ± 0.83b | 62.25 ± 0.04c | 55.70 ± 0.24d | 28.82 ± 1.01b | 17.93 ± 0.47e | 4.53 ± 0.51f |

| Protein | 10.31 ± 0.22a | 17.09 ± 0.12b | 2.42 ± 0.00c | N.D. | 15.74 ± 0.36d | 8.04 ± 0.06e | 9.05 ± 0.07e |

| Lipids | 5.12 ± 0.14a | 1.38 ± 0.71b | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0.35 ± 0.09c | 0.39 ± 0.11c |

| Sulfates | 9.75 ± 0.23a | 8.17 ± 0.67b | 5.20 ± 1.04c | 6.78 ± 0.16c | 16.28 ± 0.14d | 18.79 ± 0.37e | 21.04 ± 0.41f |

| AIR | 9.4 ± 2.50a | 4.42 ± 1.90b | N.M. | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| TC | 42.00 ± 0.70a | 31.68 ± 0.85b | 24.97 ± 0.32c | 37.10 ± 0.99d | 33.02 ± 1.96b | 49.41 ± 2.73e | 55.34 ± 3.05f |

N.M.: Not measured, N.D.: Not detected; AIR: acid insoluble residue; TC: total carbohydrates; *Data from Rodríguez-Iglesias [73].

3.8.1. By-products

For 100 g dry Ulva spp. biomass, the solid residue (SR) yielded 56.18 ± 1.65 g (d.w.), with a high protein content of 17.09 ± 0.12 % (d.w. of SR). The liquid ethanolic fraction without ulvan (LEF) from Option A, which resulted after the precipitation of ulvan with ethanol, was rotavapored and spray-dried, yielding 44.61 ± 4.01 g (d.w.) of a saline extract (SE-A) containing 9.11 ± 1.55 % (d.w. of SE-A) of glucose as main monosaccharide, and an estimate content of 57.05 ± 0.47 % salts. Option B yielded 25.5 ± 3.19 g of an equally processed saline extract (SE-B), more concentrated in glucose with 17.87 ± 1.55 % (d.w. of SE-B), and 55.70 ± 0.25 % of estimated salts. Colour rich fraction (CRF) yielded 12.12 ± 1.89 g (d.w.), showing a dark brownish colour close to black (L* = 10.52 ± 0.47, a* = 0.52 ± 0.07, b* = 1.64 ± 0.10).

The higher heating values (HHV) were assessed for SR, SE-A, SE-B and BP-3B to demonstrate their potential energy content. SR had an HHV of 13694.11 J/kg, SE-A had 14201.79 J/kg, SE-B had 14935.54 J/kg and BP-3B had 12783.97 J/kg. In all cases, these values are consistent with those typically measured in Ulva genus seaweeds, around 10 kJ/kg [38], [79].

3.8.2. Ulvans

Results show a significant enrichment (p < 0.05) in carbohydrates when comparing crude ulvan BP-3A with non-dialyzed BP-3B (nd-BP-3B), and dialyzed BP-3B (d-U3B), as summarized in Table 1, although protein contamination was conserved across all samples. The highest carbohydrate content was detected in d-U3B, measuring 55.34 ± 3.05 % (d.w.). This value is notably higher than the carbohydrate content of 37.4 ± 0.2 % reported by [39] for dialyzed ulvan, obtained from enzyme-assisted extractions at similar extraction temperature.

Direct ethanolic precipitation of ulvans offers rapid processing with the counterpart of protein and mineral contamination [63]. Although pigments and metabolites remain in the ethanol solution and are easily removed, low solubility of salts and proteins cause their coprecipitation with ulvans, overestimating yields and impairing the potential applicability of this polysaccharide. Moreover, Costa et al. [78] identified a protein contamination of 1.1–1.4 % (following proteinase treatments) and an inorganic material content of 26–43 % in the dry ethanol precipitate. Similarly, Yaich et al. [63] reported protein contamination ranging from 1.94 to 2.32 % and an inorganic material content ranging from 33.36 to 47.15 % within the ethanol precipitate.

In this line, high ash and protein contents were observed in all ulvan samples precipitated through this method, especially in BP-3A, with values of 28.82 ± 1.01 % in ash content and 15.74 ± 0.36 % in protein content, suggesting lower purity levels. The addition of a centrifugation step enabled the recovery of a pigment-rich fraction, yielding a purer non-dialyzed ulvan product with less protein contamination (nd-BP-3B), with 17.93 ± 0.47 % sulfate-free ash content and 8.04 ± 0.06 % protein content. The significant protein contamination observed in our enzymatically extracted ulvans can be attributed to the enhanced disintegration of the cell wall during treatments, leading to the coextraction of proteins that were initially part of the cell wall structure. Starch is also typically present as a storage carbohydrate of Ulva spp. [60]. Our method did not include an α-amylase nor a proteinase treatment to remove starch and proteins.

The sulfate content was high compared to the literature [80], probably preserved due to the low severity of the extraction treatment used. This is consistent with low severity enzyme extraction treatments reported by similar procedures [39]. Sulfates accounted up to 82 % of the ash content, in case of d-BP-3B.

As already suggested elsewhere [27], [63], ultrafiltration and dialysis permit the removal of salts and small contaminating molecules from ulvans, reducing the total ash content of BP-3A and BP-3B ulvan from 28.82 % and 36.72 %, down to 16.27 % and 25.57 % (d.w.), respectively. Incorporating additional steps, such as enzymatic digestion of proteins, ethanol-washing, or using chromatographic techniques, helps ensuring ulvan purity, but increases processing costs, and were not implemented in this study.

Mineral compostion of obtained ulvans, Ulva spp. and by-products is shown in Table 2, showing varying concentrations. Ca2+ was detected at 13.86 mg/kg in the BP-3A ulvan extract and 13.46 mg/kg in BP-3B, reflecting its strong association with the polysaccharide matrix. Iron (Fe) content was higher in the solid residue (512 mg/kg) compared to the ulvan extracts. Trace elements such as copper (Cu) and boron (B) were also present in measurable amounts, with Cu concentrations reaching up to 3.65 mg/kg in SE-A extracts. Boron was found in small quantities across all samples, with the highest concentration in BP-3B at 34.89 mg/kg. Notably, the levels of heavy metals such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), and mercury (Hg) were generally below the detection limit in the final ulvan extracts, suggesting minimal contamination risk from these potentially harmful elements. BP-3B showed nutraceutical potential for application in low Na+ and high K+ diets [81], with a Na+:K+ ratio as low as 0.14. In this line, contents in Mg2+ were notably high 28876 mg/kg and 30839 mg/kg for non dialyzed BP-3A and BP-3B samples, respectively.

Table 2.

Mineral composition of the raw material and obtained solid products. SR: Solid residue from the ultrasound-enzyme assisted extraction. nd-BP-3A and nd-BP-3B correspond to non-dialyzed ulvans precipitated from a non-centrifuged or centrifuged US-enzyme extract, respectively. SE-A and SE-B correspond to the liquid extracts remaining after ulvan precipitation from the mentioned streams.

| Content (mg/kg) | Ulva spp. | SR | SE-A | SE-B | nd-BP-3A | nd-BP-3B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium (Mg) (mg/kg) | 7228.02 | 14,855 | 26,732 | 25,788 | 28,876 | 30,839 |

| Potassium (K) (mg/kg) | 5428.02 | 6515 | 19,388 | 41,753 | 14,501 | 28,745 |

| Sodium (Na) (mg/kg) | 2768.09 | 81,310 | 191,284 | 161,535 | 22,233 | 3897 |

| Calcium (Ca) (mg/kg) | 578.26 | 627 | 164.9 | 156.18 | 13,859 | 13,456 |

| Iron (Fe) (mg/kg) | 7.39 | 512 | 7.96 | 4.48 | 176 | 160 |

| Boron (B) (mg/kg) | 1.10 | 14.45 | 27.26 | 26.18 | 35.76 | 34.89 |

| Copper (Cu) (mg/kg) | 0.29 | 2.76 | 3.65 | 1.84 | 3.31 | 1.38 |

| Arsenic (As) (mg/kg) | 0.07* | 2.54* | 1.58* | 0.65* | 0.64* | 0.04* |

| Selenium (Se) (mg/kg) | 4.1 | 49 | 1.30 | 1.22 | 3.56 | 3.24 |

| Lead (Pb) (mg/kg) | 0.64 | 1.31 | 0.25* | 0.15* | 0.38 | 0.23* |

| Cadmium (Cd) (mg/kg) | 0.02* | 0.11* | 0.07* | 0.00* | 0.01* | 0.09* |

| Mercury (Hg) (mg/kg) | 2.39 | < 0.5* | < 0.5* | < 0.5* | 2.29 | 0.017* |

*Bellow detection limit.

Monosaccharide composition of Ulva spp. and obtained products is summarized in Table 3. The monomeric sugars released from glucans digested by Cellic® CTec3, persist in the ulvan-free liquid after the precipitation step, resulting in a saline extract enriched in glucose (SE-A, and especially SE-B), while SR decreased its glucose content compared to the starting material.

Table 3.

Monosaccharide composition of the raw material (Ulva spp.), solid residue (SR), 702 saline extracts (SE-A, SE-B) and obtained ulvans prior to dialysis (BP-3A, BP-3B), following various acid hydrolysis treatments (d.w.% of analysed product).

|

Ulva spp. |

SR |

SE-A |

SE-B |

BP-3A (d.w.%) |

BP-3B (d.w.%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis treatment | 1. Sulfuric acid 72 %, 30 min, 30 °C; 2. Sulfuric acid 4 %, 1 h, 121 °C | Sulfuric acid 4 %, 20 min, 121 °C | Sulfuric acid 4 %, 20 min, 121 °C | TFA 1 M, 2 h, 121 °C | 1. TFA 1 M, 2 h, 121 °C; 2. TFA 2 M, 1 h, 121 °C | Sulfuric acid 4 %, 20 min, 121 °C | TFA 1 M, 2 h, 121 °C | 1. TFA 1 M, 2 h, 121 °C; 2. TFA 2 M, 1 h, 121 °C | ||

| Rhamnose | 17.18 ± 0.39 | 7.51 ± 0.13 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 1.80 ± 0.05 | 15.77 ± 0.79 | 13.64 ± 0.77 | 13.43 ± 0.72; | 24.40 ± 0.85 | 22.88 ± 2.12 | 23.58 ± 0.56 |

| Glucuronic acid | 4.18 ± 0.20 | 3.49 ± 0.16 | N.D. | N.D. | 4.69 ± 0.21 | 7.35 ± 0.61 | 5.42 ± 1.78 | 7.69 ± 0.12 | 14.77 ± 2.05 | 7.98 ± 0.01 |

| Iduronic acid | 6.31 ± 0.25 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | N.D. | N.D. | 2.51 ± 0.04 | 5.40 ± 1.27 | 4.36 ± 1.30 | 3.58 ± 0.25 | 4.32 ± 0.21 | 4.51 ± 0.01 |

| Xylose | 3.94 ± 0.23 | 2.65 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 3.42 ± 0.38 | 2.68 ± 0.29 | 2.46 ± 0.01 | 1.49 ± 0.10 | 3.77 ± 0.23 | 1.88 ± 0.06 | 3.59 ± 0.58 |

| Glucose | 10.39 ± 0.43 | 8.59 ± 0.17 | 9.11 ± 0.26 | 17.87 ± 0.86 | 0.91 ± 0.19 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Fructose | N.M. | N.D. | 2.46 ± 0.08 | 1.42 ± 0.30 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Galactose | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | < 1 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Mannose | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 2.23 ± 0.31 | 1.50 ± 0.55 | 0.53 ± 0.10 | 1.45 ± 0.74 | 2.25 ± 0.47 | N.D. |

| Arabinose | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Arabitol | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Manitol | N.M. | N.D. | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Formic acid | N.D. | 3.34 ± 0.47 | N.D. | N.D. | 0.82 ± 0.16 | 1.33 ± 0.55 | N.D. | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 2.04 ± 0.74 | N.D. |

| Acetic acid | N.D. | 3.28 ± 0.64 | 12.45 ± 0.14 | 12.47 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.14 | N.D. | 0.73 ± 0.11 | 0.78 ± 0.15 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Levulinic acid | N.D. | 1.39 ± 0.08 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 2.43 ± 0.29 | N.D. | N.D. | 2.57 ± 0.00 |

| Furfural | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| HMF | N.D. | 0.62 ± 0.10 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Others | N.M. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 5.89 ± 0.33 | N.D. | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 10.68 ± 0.22 | 1.27 ± 0.29 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| Total carbohydrates | 42.00 ± 0.70 | 31.68 ± 0.85 | 24.97 ± 0.32 | 37.10 ± 0.99 | 34.31 ± 1.02 | 33.02 ± 1.96 | 28.56 ± 1.55 | 52.94 ± 1.21 | 49.41 ± 2.73 | 42.47 ± 0.81 |

N.D.: Not detected, N.M.: Not measured.

Fructose has occasionally been detected in small quantities in Ulva spp. [82], [83], while other studies have not observed its presence [38], [84]. In our analysis, peaks corresponding to the retention time of fructose were observed in samples SE-A and SE-B, with concentrations of 2.46 ± 0.08 % and 1.42 ± 0.30 % (d.w.), respectively. However, these results were not included in Table 3 due to insufficient evidence confirming the presence of this monosaccharide in Ulva spp.

Fucose is occasionally detected in ulvan [85] and in the starting material [38]. This may be due to confusion caused by the similar retention time of glucurono-lactone on certain chromatography columns. Glucurono-lactone, derived from glucuronic acid under high temperature or acidic conditions [86], was included in this study for the quantification of total glucuronic acid.

In this sense, monosaccharide profiles of ulvan show variations across literature, as different ulvan hydrolysis methods for analysis yield different molar distributions of monosaccharides, ulvans show some variations along species [80] and because of seasonality in the composition of the algae [82]. Theoretically, ulvan is mainly composed by dissaccharides containing rhamnose and uronic acids [15]. Xylose and sulphated xylose have alse been reported in place of uronic acid residues [87]. In this line, we could assume that the ratio of rhamnose to the sum of uronic acids and xylose should be 1. In fact, these values agree with the results reported in literature for most blade Ulva species [13], [59], [88].

In this study, various acid hydrolysis treatments with increasing severity were implemented for comprehensive monosaccharide characterization of ulvans. The mildest treatment, using 4 % (w/w) H2SO4 at 121 °C for 20 min, yielded the highest amounts of xylose and rhamnose in both BP-3A and BP-3B samples. However, because of the resistance of aldobiuronic glycosidic linkages to hydrolysis, only small quantities of iduronic and glucuronic acids were detected. The stronger acid environment of 1 M TFA for 2 h resulted in more effective uronic acid liberation, although the rhamnose and xylose contents decreased due to degradation. An even more intense treatment, which extended the previous hydrolysis by an additional hour, with 2 M TFA, led to a general reduction in monosaccharide contents. Overall, the treatments with 4 % H2SO4 and 1 M TFA facilitated a more complete monosaccharide characterization of ulvans. By selecting the highest monosaccharide values from each method, the Rha:(Xyl + Uronic acids) ratio was found to be consistent with literature, yielding values of 1.02 for BP-3A and 1.05 for BP-3B. Other studies report high rhamnose contents (up to 60 mol%), comparatively to low uronic acids contents [88], [89].

Monosaccharide release through TFA hydrolysis has been pointed out by [90] as an efficient method. The subsequent fast removal of TFA through evaporation omits the need for neutralization, also minimizing potential damage on released monomers. However, [27] highlighted the inefficiency of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and other conventional acids, commonly employed in traditional acid hydrolysis methods, due to resistance of aldobiuronic glycosidic linkages and degradative effects. In our conditions, TFA treatments resulted to be useful for ulvan monomer characterization.

Some studies also mention glucose as frequent contaminant, associated to co-extracted cellulose [26], [91], but in our case cellulase and hemicellulase digestion treatments followed by dialysis eliminated most part of these contaminants. However, trace amounts of glucose (0.19–0.91 %, d.w.) were detected. In addition, trace amounts of mannose, arabinose or galactose are often detected [59], but in our study only mannose appeared in low amounts (0.53–2.25 %, d.w.). Levulinic acid detection is probably associated to acidic hidrolysis products of monomers. Hexoses usually degrade to 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural (HMF) that can further degrade to levulinic acid [92], but no intermediate compounds were measured. In sum, for an accurate quantification of ulvan monosaccharides, it is crucial to achieve an optimized combination of hydrolysis strength and duration, to produce a maximun monosaccharide liberation while minimizing their degradation.

3.9. Structural analysis of ulvan, FTIR and NMR

FTIR-spectra from analyzed ulvans are shown in Fig. 9. In Fig. 9A, BP-1 to 4 correspond to ulvans obtained from preliminary extraction assays (see Fig. 2), confirming ulvan presence in preliminary extractions. In Fig. 9B, BP-3B and ulvans obtained from membrane fractionation assays are depicted. All samples show high similarity in the fingerprint region between 700 and 1200 cm−1. Typicall sulfate groups were observed in all of samples, with symetrical stretches of C-O-S at 785 and 845 cm−1, characteristic of sulfation at axial and equatorial positions. All ulvan spectra presented a broad absorption band with a maximum around 1025 cm−1 attributed to the C-O streching and the C-O-C glycosidic bond vibrations, from the main components of ulvan: rhamnose and glucuronic acid. The absorption at ∼1210-1250 cm−1 can be attributed to the asymetrical streching of S-O, indicative of the sulfate ester substitution of rhamnoses in ulvan. These results were consistent with the ulvan charaterization performed previous studies [15], [93], and demonstrated sulfation conservation in extracted ulvans.

Fig. 9.

Fourier transform infrared spectra from ulvans after different extraction procedures, all involving US-assisted extractions at 37 kHz. A. BP-1: 60 min US-treatment, combined with enzymatic digestion, BP-2: 60 min US-treatment, without enzymatic digestion, BP-3A: 90 min US-treatment with enzymatic digestion, BP-4: 90 min US-treatment without enzymatic digestion. B. BP-3B corresponds to ulvan which included a centrifugation step of prior to precipitation. R/P10, R/P3, R/P1 correspond to retentate or permeates from the membrane fraction assay, with MWCOs of 10, 3 and 1 kDa. Continuous and discontinuous lines correspond to non-dialyzed and dialyzed samples, respectively.

Uronic acid carboxylic groups (−C O) from ulvans show typically two bands: a broad streching at ∼1600–1650 cm−1 and a second, weaker symmetric streching around 1415 cm−1 [27], both are present in the obtained samples. Interestingly, ulvans from the enzyme-assisted extraction showed a more asymmetric streching at ∼1600–1650 cm−1, presenting a bend at 1540–1545 cm−1 not present in samples which were not submitted to enzyme assisted extraction (BP-1 and BP-4), and which can be related to the N-H bending of amide bonds of protein. Proteins have often been pointed out as impurities present in extracted ulvan [30], [60]. In sum, extracted ulvans conserved the natural sulfation pattern, with mostly identical results for all the extraction variants despite little differences in enzyme-treated samples, probably related to protein impurities. The bioactivity of sulfated polysaccharides has been linked to the sulfate groups, with particular emphasis on their positioning within the chemical structure rather than only the quantity present. This aspect was highlighted as crucial for providing ulvan-based biomaterials with bioactive properties [85].

As a complex polysaccharide, ulvan poses challenges in its structural analysis due to its irregular and heterogeneous nature, often disrupted by sulfate groups, its high molecular weight, the multitude of possible disaccharide sequences, and the presence of contaminants, making 1H NMR spectra analysis complicated [85], [94]. The obtained 1H NMR spectra are depicted in Fig. 10 and are comparable with data from previous studies [14], [16], [38], [95]. Fig. 10A shows ulvans from preliminary extraction assays, including BP-3A. These spectra resulted more impure than those of BP-3B and BP-3B-R3, which showed very similar results (Fig. 10C). Fig. 10B shows proposed disaccharide conformations, identified in the analyzed ulvans. Obtained spectra, particularly in the 3.25–5.25 ppm region, reflect the hybrid composition of ulvans, rich in rhamnose and uronic acids, with traces of xylose and glucose [38], [94], [95].

Fig. 10.

1H NMR spectra of ulvans extracted from Ulva spp. Relevant peaks are pointed out with arrows. A. BP-1: 60 min US-treatment, combined with enzymatic digestion, BP-2: 60 min US-treatment, without enzymatic digestion, BP-3A: 90 min US-treatment with enzymatic digestion, BP-4: 90 min US-treatment without enzymatic digestion. B. BP-3B corresponds to ulvan of identical extraction method as BP-3A but which included a centrifugation step of prior to precipitation. BP-3B-R3 correspond to ulvan precipitated from the 3 kDa retentate of the membrane fraction assay.

Across all samples, several peaks appeared between 3.25 and 4.25 ppm, a region which is representative of ring protons of ulvan monomers [96]. The measured signals of BP-3B were classified as representative example, according to previous studies with spectra recorded at simmilar temperatures [14], [16], [95], [97] and are summarized in Table 4. The two intense peaks around 1.40 and 1.30 (with slight differences across samples) correspond to protons of methyl groups of sulfated and non-sulfated α-L-rhamnosyl monomers, respectively [98]. Signals downstream of 4.6 ppm, mainly corresponding to anomeric protons (H1), have less intense signals [95]. This, together with the big peak of deuterium oxide (D2O; 4.82–4.88 ppm) made it difficult to assign any peaks from this region, although some anomeric protons could be assigned. Fig. 11 shows representative example of bidimensional NMR spectra of crude ulvan BP-3A, in line with results from literature, although some contamination is evident [30], [80].

Table 4.

Assignment of BP-3B ulvan proton chemical shifts (ppm), obtained through 1H NMR spectrum analysis.

| Disaccharide | Chemical shifts |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP-3B | RV1 | BP-3B | RV1 | BP-3B | RV1 | BP-3B | RV1 | BP-3B | RV1 | BP-3B | RV1 | ||

| A3s | [⟶4)-β-D-GlcA-(1⟶ | 4.65 | 4.65 | 3.39 | 3.36 | 3.66 | 3.66 | 3.66 | 3.66 | 3.77 | 3.76 | − | − |

| 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] | a | 4.85 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 4.65a | 4.63 | 3.80 | 3.80 | 4.17a | 4.17 | 1.35 | 1.32 | |

| B3s | [⟶4)-α-L-IdoA-(1⟶ | 5.11 | 5.12 | 3.68 | 3.68 | 3.85 | 3.85 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.56 | 4.58 | − | − |

| 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] | 4.97a | 4.97 | 4.25 | 4.24 | 4.65a | 4.65 | a | 3.79 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 1.35 | 1.32 | |

| U3s | [⟶4)-β-D-Xyl-(1⟶ | 4.65 | 4.65 | a | 3.36 | 3.66 | 3.66 | a | 3.62 | 4.10a | 4.10 | – | − |

| 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] | a | 4.91 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 4.65a | 4.63 | 3.80 | ∼3.81 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 1.35 | 1.32 | |

| U2′s,3s | [⟶4)-β-D-Xyl 2S-(1⟶ | 4.97a | 4.97 | a | 4.15 | 3.85 | 3.86 | 3.70 | ∼3.70 | 3.50 | 3.50 | − | − |

| 4)-α-L-Rha 3S-(1⟶] | 4.95 | 4.95 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 4.65a | 4.63 | 3.80 | ∼3.81 | 4.10a | ∼4.10 | 1.35 | 1.32 | |

a. Not detected, weak or unclear signal due to overlapping.

1 Reference value: de Freitas et al. (2015).

Fig. 11.

Representative example of 1H–13C HSQC spectra of crude ulvan BP-3A.

BP-3B samples exhibited less contaminated, more intense and clearer signals, probably due to absence of contaminants compared to BP-3A (e.g. signals around 2.80 and 3.00 ppm were significantly less intense in enzyme treated samples). Starch contamination (5.30–5.34 ppm) in U3-B samples was minimal [15].

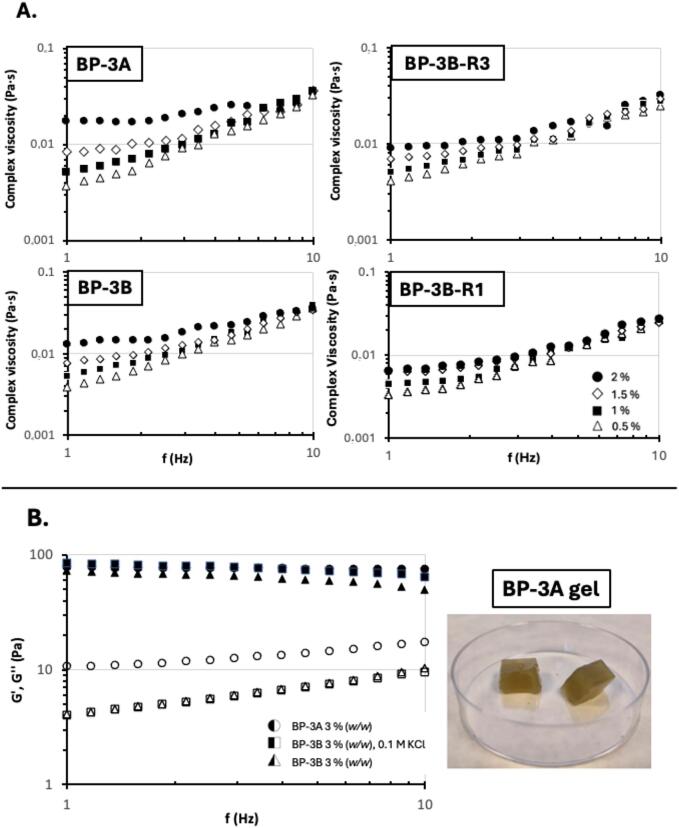

3.10. Rheology

Fig. 12A shows the results from the small amplitude oscillatory shear measurements of the extracted ulvans. In all cases, the complex viscosity increased with increasing frequency, which is typical for systems with a liquid-like behavior [99]. The effect of the biopolymer content on the complex viscosity was also clearly observed, achieving the maximum values at the highest biopolymer content. Note here that the highest differences on this parameter were identified at the lowest tested frequencies, tending to a common value at the highest tested frequencies. As expected, the magnitude of the complex viscosity was higher for the crude ulvan (BP-3A), followed by BP-3B and the corresponding fractions (BP-3B-R3 and BP-3B-R1). This is consistent with the results previously reported for other biopolymer-based systems [35], where lower average molecular weights involved lower viscoelastic features. As a representative example of the ability of these ulvans to form gels, the mechanical spectra of BP-3A and BP-3B are displayed in Fig 12B. A typical gel behavior is observed, with the elastic modulus exceeding the viscous modulus. According the values of the viscoelastic moduli and tendencies, weak gels were developed, being the strongest those formulated in the presence of potassium chloride. No water syneresis was identified in any of the systems after 2 weeks cold-storage, which is an indicative of the stability of the formulated matrices. Although several promising applications for ulvan hydrogels are discussed in literature [5], [8], [9], [29], practical testing and evaluation of these applications were beyond the scope of this study.

Fig. 12.

A. Dispersions of ulvan samples, at different concentrations. BP-3A corresponds to ulvan obtained without a centrifugation step of the extract. BP-3B corresponds to ulvan precipitated after centrifugation of the extract. BP-3B-R1 and −R3 correspond to a 1–3 kDa and 3–10 kDa retentate from a membrane fractionation process, respectively. B. Circles represent BP-3A ulvan, triangles illustrate BP-3B ulvan, and squares show BP-3B ulvan with addition of KCl 0.1 M. Note here that closed symbols represent the loss modulus and open symbols the storage modulus. All samples contain ulvan at 3 % (w/w).

4. Conclusions

The incorporation of the novel comercial Cellic® CTEC3 enzyme cocktail used for the first time in Ulva spp., significantly enhanced the yield and quality of ulvan extracted from Ulva spp. The enzyme mix facilitated the breakdown of cell wall polysaccharides, thereby improving the release of ulvan. Additionally, ultrasound treatment contributed to cell wall disruption, which, when combined with enzymatic action, further improved ulvan extraction efficiency. We demonstrated various processing pathways for US-enzyme extracted ulvans, achieving progressively higher purities with more elaborate methods, obtaining dialyzed ulvan with a carbohydrate content of up to 55.34 ± 3.05 % (d.w.) without glucose contamination. FTIR and NMR spectra confirmed the sulfation and presence of typical ulvan functional groups. Rheology assays demonstrated the biopolymeric behavior of ulvan samples and their ability to form stable gels, especially in case of crude ulvan and in the presence of potassium chloride. A highly ulvan-concentrated liquid fraction was obtained by sequential membrane ultrafiltration, at 3 kDa MWCO, containing 93.51 ± 1.58 % ulvan relative to the dry weight. Sequential membrane fractionation permitted the partial concentration of smaller molecular weights, especially in the BP-3B-R3 and BP-3B-R1 fraction, although it did not effectively separate fractions based on different molecular weights. Comparatively, depolymerization experiments involving acid and microwave treatments, with or without H2O2, showed cleaner shifts to low molecular weight ulvans with less high molecular weight residue. Future studies could focus on a detailed compositional analysis of ultrafiltrated ulvans, further optimization of the extraction process using Cellic® CTec3, pilot studies to assess scalability and the development of innovative technologies for ulvan applications. These efforts could contribute to the transformation of Ulva spp. from an environmental challenge into a valuable biomaterial resource.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

K.L. Baltrusch: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. M.D. Torres: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. H. Domínguez: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge SEM measurements, FTIR and NMR to the services of analysis of Universidade de Vigo (CACTI). K.L.B. acknowledges to the predoctoral fellowship program of the Xunta de Galicia (Consellería de Educación, Ciencia, Universidades e Formación Profesional), co-financed by the European Union under the FSE + Galicia 2021-2027 Program. M.D.T. acknowledges to the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain for her postdoctoral grants (RYC2018-024454-I) and to the Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Universidade da Xunta de Galicia (ED431F 2020/01).

References

- 1.Sfriso A.A., Gallo M., Baldi F. Seasonal variation and yield of sulfated polysaccharides in seaweeds from the Venice Lagoon. Bot. Mar. 2017;60(3):339–349. doi: 10.1515/bot-2016-0063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skriptsova A.V. Seasonal variations in the fucoidan content of brown algae from Peter the Great Bay, Sea of Japan. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2016;42(4):351–356. doi: 10.1134/S1063074016040106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd V.A., Beilby M.J., Heslop D.J. Ecophysiology of the hypotonic response in the salt-tolerant charophyte alga Lamprothamnium papulosum. Plant, Cell Environ. 1999;22(4):333–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00414.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade L.R., et al. Brown algae overproduce cell wall polysaccharides as a protection mechanism against the heavy metal toxicity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010;60(9):1482–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.L. Cunha, A. Grenha, Sulfated seaweed polysaccharides as multifunctional materials in drug delivery applications, Mar. Drugs, 14 (3), 2016, doi: 10.3390/md14030042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Zaitseva O.O., Sergushkina M.I., Khudyakov A.N., Polezhaeva T.V., Solomina O.N. Seaweed sulfated polysaccharides and their medicinal properties. Algal Res. 2022;68(October) doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2022.102885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.K. Iliou, S. Kikionis, E. Ioannou, V. Roussis, Marine biopolymers as bioactive functional ingredients of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications, Mar. Drugs, 20 (5), 2022, doi: 10.3390/md20050314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Morelli A., Puppi D., Chiellini F. ‘Perspectives on biomedical applications of ulvan’, seaweed polysaccharides isol. Biol. Biomed. Appl. 2017:305–330. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809816-5.00016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.S. Shen, X. Chen, Z. Shen, H. Chen, Marine polysaccharides for wound dressings application: an overview, 13 (10) 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Mantri V.A., Kazi M.A., Balar N.B., Gupta V., Gajaria T. Concise review of green algal genus Ulva Linnaeus. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020;32(5):2725–2741. doi: 10.1007/s10811-020-02148-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H., Wang G., Gu W. Macroalgal blooms caused by marine nutrient changes resulting from human activities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020;57(4):766–776. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dominguez H., Loret E.P. Ulva lactuca, a source of troubles and potential riches. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17(6):1–20. doi: 10.3390/md17060357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tziveleka L.A., Ioannou E., Roussis V. Ulvan, a bioactive marine sulphated polysaccharide as a key constituent of hybrid biomaterials: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;218(April):355–370. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahaye M., Inizan F., Vigouroux J. NMR analysis of the chemical structure of ulvan and of ulvan-boron complex formation. Carbohydr. Polym. 1998;36(2–3):239–249. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00026-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robic A., Bertrand D., Sassi J.F., Lerat Y., Lahaye M. Determination of the chemical composition of ulvan, a cell wall polysaccharide from Ulva spp. (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) by FT-IR and chemometrics. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009;21(4):451–456. doi: 10.1007/s10811-008-9390-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Freitas M.B., Ferreira L.G., Hawerroth C., Duarte M.E.R., Noseda M.D., Stadnik M.J. Ulvans induce resistance against plant pathogenic fungi independently of their sulfation degree. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;133:384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.C. Li et al., Ulvan and Ulva oligosaccharides: a systematic review of structure, preparation, biological activities and applications, Bioresour. Bioprocess., 10 (1), 2023, doi: 10.1186/s40643-023-00690-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Flórez-Fernández N., et al. Anti-inflammatory potential of ulvan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;253(August) doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.S. K. Kim, I. Wijesekara, Anticoagulant effect of marine algae, in Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, vol. 64, S.-K. B. T.-A. in F. and N. R. Kim, Ed. Academic Press, 2011, pp. 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Qi H., Zhao T., Zhang Q., Li Z., Zhao Z., Xing R. Antioxidant activity of different molecular weight sulfated polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa Kjellm (Chlorophyta) J. Appl. Phycol. 2005;17(6):527–534. doi: 10.1007/s10811-005-9003-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee D.G., et al. Ulva lactuca: A potential seaweed for tumor treatment and immune stimulation. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2004;9(3):236–238. doi: 10.1007/BF02942299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabarsa M., You S., Dabaghian E.H., Surayot U. Water-soluble polysaccharides from Ulva intestinalis: molecular properties, structural elucidation and immunomodulatory activities. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018;26(2):599–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanova V., Rouseva R., Kolarova M., Serkedjieva J., Rachev R., Manolova N. Isolation of a polysaccharide with antiviral effect from ulva lactuca. Prep. Biochem. 1994;24(2):83–97. doi: 10.1080/10826069408010084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Tran T.T., et al. Structure, conformation in aqueous solution and antimicrobial activity of ulvan extracted from green seaweed Ulva reticulata. Nat. Prod. Res. Oct. 2018;32(19):2291–2296. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1408098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pengzhan Y., Ning L., Xiguang L., Gefei Z., Quanbin Z., Pengcheng L. Antihyperlipidemic effects of different molecular weight sulfated polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa (Chlorophyta) Pharmacol. Res. 2003;48(6):543–549. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(03)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaich H., et al. Impact of extraction procedures on the chemical, rheological and textural properties of ulvan from Ulva lactuca of Tunisia coast. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;40(2014):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidgell J.T., Magnusson M., de Nys R., Glasson C.R.K. Ulvan: A systematic review of extraction, composition and function. Algal Res. 2019;39(January) doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulastri E., Zubair M.S., Lesmana R., Mohammed A.F.A., Wathoni N. Development and characterization of ulvan polysaccharides-based hydrogel films for potential wound dressing applications. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021;15:4213–4226. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S331120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tziveleka L.A., Ioannou E., Roussis V. Ulvan, a bioactive marine sulphated polysaccharide as a key constituent of hybrid biomaterials: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;218(March):355–370. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glasson C.R.K., Sims I.M., Carnachan S.M., de Nys R., Magnusson M. A cascading biorefinery process targeting sulfated polysaccharides (ulvan) from Ulva ohnoi. Algal Res. 2017;27:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2017.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robic A., Gaillard C., Sassi J.F., Leral Y., Lahaye M. Ultrastructure of Ulvan: a polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biopolymers. 2009;91(8):652–664. doi: 10.1002/bip.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidara M., et al. Effects of extraction procedures and plasticizer concentration on the optical, thermal, structural and antioxidant properties of novel ulvan films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;135(2019):647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quitério E., Grosso C., Ferraz R., Delerue-Matos C., Soares C. A critical comparison of the advanced extraction techniques applied to obtain health-promoting compounds from seaweeds. Mar. Drugs. 2022;20(11):1–40. doi: 10.3390/md20110677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.S. U. Kadam, C. Álvarez, B. K. Tiwari, C. P. O’Donnell, Extraction of biomolecules from seaweeds. Elsevier Inc., 2015.