Abstract

This pilot study examines Ohio’s licensed nursing home administrators and state tested nursing assistant’s perspectives about job satisfaction, future career and employment plans, potential beneficial changes to their organizations, and their thoughts on reducing turnover rates in their field. Ohio Board of Executives of Long-Term Services and Supports provided their contact list of all 1,969 licensed nursing home administrators in Ohio in the fall of 2023. Two surveys were created for licensed nursing home administrators and state tested nursing assistants. Results were analyzed for themes within the open-ended responses; 28 surveys were received from licensed nursing home administrators and 17 surveys were received from state tested nursing assistants. Residents and their families are among the top reasons for job satisfaction, many employees face symptoms of burnout, and wages are a concern among both state tested nursing assistants and licensed nursing home administrators. Future career plans differed between the two professions and had distinct driving factors. A discussion of licensed nursing home administrators’ opinions on improving retention and turnover rates should include more accountability, personal responsibility, and adding opportunities for professional growth and development.

Keywords: state tested nursing assistant, job satisfaction, career planning, assisted living, caregiving, employment, nursing home administration, staffing

What this Paper Adds to Existing Literature:

Perceptions from Ohio’s Licensed Nursing Home Administrators (LNHA) and State Tested Nursing Assistants (STNAs) about job satisfaction, future career plans, and thoughts on how to reduce turnover rates in their field.

Staffing shortages contribute to healthcare worker burnout, and it has been difficult for nursing homes to maintain staffing ratios.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, both LNHAs and STNAs report that the administrative burdens being placed by the Ohio Department of Health have been issues.

Applications of Study Findings:

Educational interventions targeted at improving STNA retention rates and career advancements may be beneficial to implement in nursing homes in Ohio.

STNAs may benefit from being educated about how reimbursement works and how it directly influences their wages and benefits.

The implications of how COVID-19 influences career plans for LNHAs and STNAs will be beneficial for future research to develop ways to increase retention and decrease turnover rates in this field.

Introduction

Direct care workers (DCW) in nursing homes during the pandemic faced difficult challenges that were both personal and work-related—staffing shortages, turnover, unsuccessful retention strategies, increased workload demands, increased reports of dysregulated emotions, isolation, financial burdens, and familial hardships (Cimarolli et al., 2022). Despite decreases in long-term nursing home stays, the older adult population is rapidly growing (Mather & Scommenga, 2024; Toth et al., 2022; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). More older adults are going to need long-term care (LTC), and this directly impacts the continual need for DCWs in LTC facilities the United States (U.S.). The direct care workforce is among the fastest-growing occupations in the U.S. between 2022 and 2032, yet factors such as job satisfaction, work hours, salary, turnover and retention rates, benefits, and limited opportunities for future career advancements are why DCWs continue to leave the profession (Bergman et al., 1984; Castle et al., 2007a; Kim, 2020; Morgan et al., 2013; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). It is adamant that the aging population has enough DCWs moving forward to avoid possible physical, medical, and social problems (Potter et al., 2006).

Nursing education was drastically changed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chan et al., 2021). Licensure exam testing was delayed because of the pandemic, causing graduating classes of nurses being unable to practice; at the same time, nurses left the healthcare profession altogether (Chan et al., 2021). The entry-level education for state tested nursing assistants (STNAs) and other DCWs in similar roles in Ohio is some high school education with additional on-the-job training (Morgan et al., 2013). In comparison, the level of education required to become a licensed nursing home administrator (LNHA) in Ohio requires a minimum of a bachelor’s degree from an accredited university, and Ohio Board of Executives of Long-Term Services and Supports (BELTSS) core knowledge, and a 1,000 clock hour Administrator in Training, or graduation from a National Association of Long-Term Care Administrator Boards accredited program (Ohio BELTSS, 2023). Credentials alone can significantly increase the likelihood of an employee having access to opportunities that advance their careers, better benefits, and higher salaries (Kim, 2020).

The LTC industry continues to face three major challenges: the need to increase worker retention, wages, and provide better service qualities (Kim, 2020). They can be addressed by providing more opportunities for continuing education that leads to the acquisition of additional credentials for DCWs. This may subsequently assist DCWs in future career planning and encourage them to remain in the LTC profession, lowering retention and turnover rates over time (Kim, 2020). Turnover and retention among DCWs is an issue that has been studied for decades and tends to be positive for the individual worker but poses a negative framework for the facilities where they work (Bergman et al., 1984; Castle et al., 2007a, 2007b; Kennedy et al., 2022; Morgan et al., 2013; Rollison et al., 2023; Rosen et al., 2011). Wage gaps exist between STNAs and higher levels of nursing staff due to job requirements and educational backgrounds (McHenry & Mellor, 2022; Ward et al., under review). Minimum wage for these positions in comparison to wage increases in the LTC setting has historically shown short-term declines in the number of employees working at the same time; when this happens, the number of hours worked by individual employees also decreases, which contributes to their lower salaries and greater wage gaps by job position (Machin & Wilson, 2004; McHenry & Mellor, 2022; Vadean & Allan, 2021).

Job satisfaction influences future career planning for DCWs (Castle et al., 2007a; Cimarolli et al., 2022). Effective communication from leadership during high-stress situations like the pandemic has been linked to higher job satisfaction and intent to stay (Cimarolli et al., 2022). However, work-specific demands related to COVID-19, such as requiring additional personal protective equipment and new safety rules have not clearly affected job satisfaction (Bryant et al., 2023).

DCW burnout has been a long-standing issue within the profession, further highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic (Gambaro et al., 2023; Hastings et al., 2004; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Burnout is defined by Maslach and Leiter (2016) as a “psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job.” During the pandemic, DCWs faced additional stress and mental health concerns due to expanded job duties and low staffing levels (Gambaro et al., 2023). Symptoms of stress can reflect employee wellbeing through motivation, commitment to residents and their organizations, and job satisfaction (Lindmark et al., 2023).

This pilot study sought to collect insights from Ohio’s LNHAs and STNAs regarding job satisfaction, future career and employment plans, suggested organizational improvements, and perspectives on reducing turnover rates in their field. This paper’s main objective is to delve into Ohio’s LNHAs’ and STNAs’ opinions regarding their respective disciplines. By comparing their responses, the aim is to enhance understanding of the working dynamics between these two professions. By understanding the perspectives of DCWs in LTC settings, key issues can be strategically identified and a foundation for initiatives can be established that contributes to an increase in the workforce interested in and committed to working as DCWs.

Methods

Ohio Board of Executives of Long-Term Services and Supports (BELTSS) provided the investigators with access to email addresses of all 1,969 LNHAs in Ohio. The study was approved by Youngstown State University’s Institutional Review Board (#2022-116). Incentives were not offered for participation. Informed consent was collected electronically at the beginning of each survey. The first survey was for LNHAs and data were collected between 10/18-11/8/2023. The second survey was for STNAs and the investigators asked the same LNHA sample to share the survey with STNAs in their facilities; data were collected between 11/16-12/18/2023. Alchemer’s survey services were used to create and distribute a survey link and QR code for both surveys, and a flyer was attached in the STNA survey for distribution by LNHAs who received the emails.

The two surveys were developed as part of a larger pilot study that assessed both the LNHA perspective of STNA staffing, retention, turnover rates, and their opinions of their own jobs, as well as the STNA perspective of their jobs, relationship with management, levels of education, intent to turnover, and career advancement. Questions 42 to 49 from the LNHA survey and questions 3 and 7 to 13 from the STNA survey are analyzed in this paper. The outcomes are derived from the responses given for each question, with sample sizes specified for clarity.

A content analysis was conducted on the open-ended inquiries within the surveys. By aligning the survey questions common to both STNAs and LNHAs, a comparative examination was undertaken to identify prevalent themes. Subsequently, two researchers autonomously analyzed the responses to discern recurring themes, followed by a collaborative session to cross-reference and match their findings. In instances where researchers’ themes did not align, deliberation ensued until consensus was reached, preventing the necessity for a third-party researcher input. Confirmation of thematic saturation within the responses was unattainable due to the limited cohort of participants who engaged with the open-ended questions (Creswell, 2018).

Results

Between the two surveys, 27 responses were received from LNHAs and 17 responses were received from STNAs. Question-specific response rates are listed in each table and in figure captions. Question 3 of the STNA survey asks if they would leave their current job, and if so, how quickly. Half of the sample (52.6%) reported often thinking about quitting their jobs and a similar percentage responded that they will look for a new job in the next year (47.4%), in comparison to only 21.1% who want to leave their current workplace as soon as possible (Table 1).

Table 1.

Question 3 Results from STNA Survey and Response Rates.

| Survey | Responses | Number | Question | Count (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unlikely | Neutral | Likely | ||||

| STNA | n = 19 | 3 | I often think about quitting my present job. | 3 (15.8) | 6 (31.6) | 10 (52.6) |

| I will probably look for a new job in the next year. | 4 (21.1) | 6 (31.6) | 9 (47.4) | |||

| As soon as possible, I will leave the organization. | 6 (31.6) | 9 (47.4) | 4 (21.1) | |||

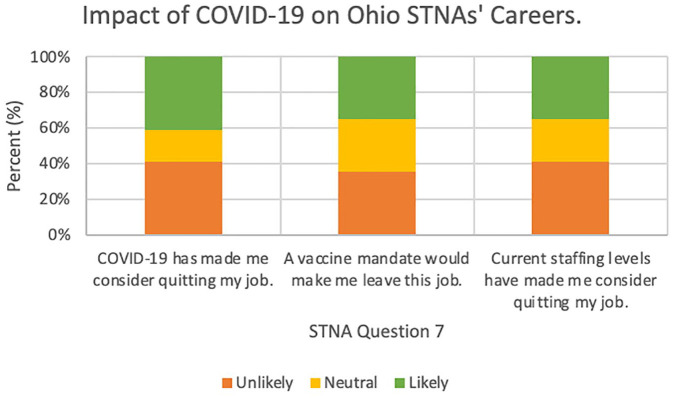

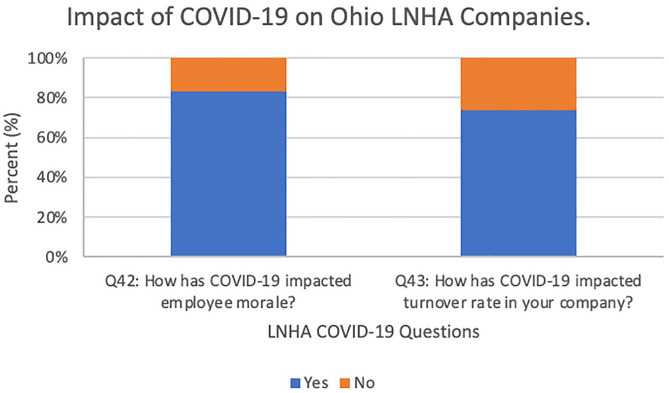

Question 7 of the STNA survey and questions 42 and 43 of the LNHA survey asked about how COVID-19 influenced career planning in Ohio’s nursing homes. COVID-19 equally influenced turnover among respondents (41.2%) (Figure 1). LNHAs responded that it largely influenced employee morale (83.3%) and highly impacted turnover rate (73.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Best description of the impact of COVID-19 on your career: Response rate (COVID-19): 7 unlikely, 3 neutral, 7 likely; Response rate (Vaccine): 6 unlikely, 5 neutral, 6 likely; Response rate (Staffing): 7 unlikely, 4 neutral, 6 likely.

Figure 2.

COVID-19 impacts on Ohio’s nursing homes: Response rate (Morale): 19 yes, 4 no; Response rate (Turnover): 20 yes, 3 no.

The central focus on the positive aspects of working in LTC is centered around the residents, as indicated by responses from both surveys. In question 8 of the STNA survey and question 44 of the LNHA survey, participants were asked to highlight the positive aspects of their jobs, and residents and interactions with residents and their families were a bright spot in their work. “Taking care of my residents and knowing they appreciate what I can do for them” and “When residents succeed in therapy or families receive peace knowing their transitioning loved one is well taken care of” are two the statements that suggest high points to working in LTC. Residents are the reason people have jobs in LTC and can make the job rewarding. It was stated in the survey that “personal satisfaction in helping others” and “performing meaningful work” keep employees satisfied with their occupations.

Questions 9 and 10 of the STNA survey and 45 and 46 of the LNHA survey ask about future career plans. There were mixed responses that were dependent on individual’s situations and both positive and negative attitudes. The strongest themes among STNAs’ reasons for turnover were pay, benefits, and support from management. Both STNAs and LNHAs commented on government regulation as a reason for leaving their LTC jobs, stating “The government makes it increasingly challenging with constant surveys that demolish the morale you’re trying to rebuild. Reporting requirements take away from patient care. Staffing mandates are going to force facilities to close because IT CANNOT BE DONE!!! Creating a staffing mandate in the midst of the worst staffing crisis in long term care. . .just screams how valued we are as an industry.” and “The Ohio Department of health makes it difficult to love my job.” Some LNHAs reported responses reflecting that they were happy in their positions, stating, “I enjoy being an administrator and I am happy where I am currently working” and “My plans are to remain in place, and truly build a culture where people want to work and feel a sense of community.”

Most LNHAs (69.6%) do not have future career plans while over half of STNAs (53.8%) do have future career plans (Table 2). A majority of the STNAs (57.1%) could see themselves leaving their company, while 47.8% of LNHAs responded that they could and 47.8% responded that they could not see themselves leaving their company (Table 2). STNAs who have future career plans report a mix of retirement and pursuing a degree in nursing depending on age and individual situations, which was reflected in question 11 of the STNA survey where only 14.3% responded that they would reapply to their current position again (Table 2). LNHAs who report future career plans either state getting out of healthcare completely or working their way up the ladder to a more corporate position. Question 47 of the LNHA survey was split, where 47.8% responded yes and 43.5% responded no to being asked if they would apply to their current position again (Table 2). LNHAs appear to have less desire to leave the field based on their responses about staying in healthcare. LNHAs also have more time and education dedicated to serving the older adult population than STNAs; the LNHA investment in their careers is greater than a STNA, so it makes a direct comparison difficult (Table 3).

Table 2.

Questions and Response Rates of Open-Ended Questions Asked in the STNA and LNHA Surveys.

| Survey | Responses | Number | Question | Count (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | N/A | ||||

| STNA | n = 13 | 9 | What are your future career/ employment plans? | 7 (53.8) | — | 6 (46.2) |

| LNHA | n = 23 | 45 | 7 (30.4) | — | 16 (69.6) | |

| STNA | n = 14 | 10 | Could you see yourself leaving this company? | 8 (57.1) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (21.4) |

| LNHA | n = 23 | 46 | 11 (47.8) | 11 (47.8) | 1 (4.3) | |

| STNA | n = 14 | 11 | Would you apply to this position again? | 2 (14.3) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (28.6) |

| LNHA | n = 23 | 47 | 11 (47.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| STNA | n = 13 | 12 | If given the opportunity, what changes would you make at this organization? | 8 (61.5) | — | 5 (38.5) |

| LNHA | n = 20 | 48 | 16 (80.0) | — | 4 (20.0) | |

| STNA | n = 13 | 13 | How can we reduce turnover rates in our field? | 8 (61.5) | — | 5 (38.5) |

| LNHA | n = 22 | 49 | 20 (90.9) | — | 2 (9.1) | |

Table 3.

Content Analysis of Open-Ended Questions Asked in the STNA and LNHA Surveys.

| Survey | Responses | Number | Question | Content analysis themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STNA | n = 13 | 9 | What are your future career/ employment plans? | Retirement, nursing |

| LNHA | n = 23 | 45 | Getting out of healthcare, moving up in a company | |

| STNA | n = 14 | 10 | Could you see yourself leaving this company? | Pay, benefits, management |

| LNHA | n = 23 | 46 | Reimbursement, satisfaction | |

| STNA | n = 13 | 12 | If given the opportunity, what changes would you make at this organization? | Wages, management, scheduling |

| LNHA | n = 20 | 48 | Wages, administrative burden, reimbursement, leadership | |

| STNA | n = 13 | 13 | How can we reduce turnover rates in our field? | Wages, schedules, staff ratios |

| LNHA | n = 22 | 49 | Reimbursement, wages, support |

Questions 12 and 13 of the STNA survey and 48 and 49 of the LNHA survey ask what changes they would make to their current organization and ideas to reduce turnover at their place of employment. Most STNAs (61.5%) and LNHAs (80.0%) provided suggestions for changes, and similar percentages of STNAs (61.5%) and LNHAs (90.9%) provided ways to reduce turnover rates in their field (Table 2). Themes between both STNAs and LNHAs in this category were wages, reimbursement, administrative burden, resources, accountability, and leadership. LNHAs report needing better reimbursement rates to pay higher wages. STNAs suggested, “Raise pay. Improve staffing ratios. Improve benefits. Offer more bonuses. . .” and “Higher wages. Better schedules.” as ways to reduce turnover from their standpoint. LNHAs state that the changes needed to help turnover are to “incentivize longevity in reimbursement rates” and “raise our reimbursement rates, stop making us take homeless people who can’t pay or file a Medicaid application.”

Discussion

This pilot study represents the inaugural attempt to compare the perspectives of LNHAs and STNAs regarding their work experiences, personal sentiments, and identified areas for enhancement within the LTC setting. Current research indicates that the challenges faced in previous literature, both as written pre- and post-COVID-19, are still present in nursing homes today, which include education, wages, staffing, retention, turnover, job satisfaction, future career plans, and burnout (Brazier et al., 2023; Bryant et al., 2023; Castle et al., 2007a, 2007b; Cimarolli et al., 2022; Hastings et al., 2004; Kennedy et al., 2022; Kim, 2020; Lindmark et al., 2023; Machin & Wilson, 2004; Maslach & Leiter, 2016; McHenry & Mellor, 2022; Morgan et al., 2013; Ohio BELTSS, 2023; Potter et al., 2006; Rodríguez-Nogueira et al., 2022; Rosen et al., 2011; Vadean & Allan, 2021; Ward et al., under review). Job satisfaction influences both turnover and intent to leave when satisfaction is low; therefore, when staff turnover rates are high, lower quality care is reflected in the facility and among DCWs who provide care to the residents (Castle et al., 2007a, 2007b; Levere et al., 2021). In previously studied literature, the main factors that influenced whether DCWs would leave or remain at their facilities included job satisfaction, emotional factors, benefits (sick leave, health insurance, paid time off) and intrinsic rewards (meaningfulness of their job, individual autonomy) (Morgan et al., 2013; Rosen et al., 2011). This survey revealed a consensus among LNHAs and STNAs, indicating that individuals with a career in LTC derive satisfaction from working with residents and their families. LTC workers enjoy working with their residents and genuinely like the satisfaction that comes with helping other people. Over half (53.8%) of STNAs who responded to this survey have plans to continue a career in nursing, indicating that they want to continue working in healthcare. Half (53.8%) of STNAs have future career or employment plans, and 30.8% are in school for or plan to go to school for a nursing degree, while 69.6% of the LNHAs do not have future career or employment plans. There were still many complaints that led to stress and burnout from both LNHAs and STNAs.

High levels of DCW burnout are associated with high levels of job-related anxiety and stress (Gambaro et al., 2023). Research shows that developing strong positive relationships with co-workers and supervisors can work to combat the effects of burnout, whereas tense and stressful relationships contribute to the negative effects of burnout (Maslach & Lieter, 2016). Concerns regarding stress and staffing are reflected in the results from the current study, where one STNA responded, “more money and less stress and to be considerate of the hard work we do. . .,” and one LNHA stated, “Lowered stressful expectations, more resources” when asked about reducing turnover rates and changes to make in their organizations, respectively. Addressing staffing ratios may be helpful to reduce burnout, but one STNA recommended to “Appreciate staff, wouldn’t put so much on the aides, & better pay. Also, better care for the residents it’s impossible to give good care when your taking care of too many people.” There is also concern with hiring and maintaining enough staff to sustain staffing ratios. When staffing needs cannot be met, companies have to use agency staffing, which is very costly.

Staffing shortages in U.S. LTC facilities have presented challenges for all DCWs. Frontline workers who remain in the field post-COVID-19 have observed the effects of a global pandemic and how long-term effects are impacting both workers and residents alike (Brazier et al., 2023). In previous literature and in the current study, LNHAs reported low staffing levels, difficulty compensating for the lack of staff, and challenges with restaffing their facilities after the worst of the pandemic was over (Brazier et al., 2023). In 2023, turnover rates for DCWs—LNHAs and STNAs in particular—ranged from 35% to 90% depending upon the setting and job title (Rollison et al., 2023). When this study was conducted in 2021, STNA turnover and intent to leave was not influenced by COVID-19, whereas LNHAs reported that the pandemic did influence turnover rate in their facilities (Figures 1 and 2).

Many LNHAs report that Medicare and health insurance reimbursement limits hinder better care and raising wages. A study in Ohio found that higher Medicaid reimbursement rates led to more staff but did not improve other quality measures (Bowblis & Applebaum, 2017). It is also noted in the results that STNAs did not mention reimbursement as a factor, so it is probable that they are unaware of this obstacle that LNHAs and LTC facilities face when making decisions about budgets and wages.

To improve staff retention, increasing hourly wages and giving STNAs opportunities to feel heard within their companies is suggested (Kennedy et al., 2022; Morgan et al., 2013). Education levels influence wages since the training required for STNAs is different from that for LNHAs (Chan et al., 2021; Ward et al., under review). Many STNAs in this study expressed a desire to advance in the nursing profession, which would involve pursuing higher education. As they progress, they will understand the reimbursement and wage challenges that they were unaware of as STNAs.

Conclusion

This pilot study will help guide future research and help to better understand how to frame research questions to further investigate why LNHAs and STNAs stay in or leave the LTC setting. The major themes of retirement, getting out of healthcare, salary, benefits, management, and support will help frame future studies, including potential intervention research to improve working conditions and study their impact on satisfaction.

The response rate may have been low due to the LNHA survey length and because of reliance on snowball sampling through LNHAs to share the STNA survey with the STNAs in their facilities rather than contacting them directly. This was due to the availability and accessibility of email lists, since Ohio BELTSS provided an Ohio LNHA email list, but they do not have active STNA email lists. In future studies, incorporating a set of open-ended questions to delve into the limitations perceived by LNHAs, along with specific inquiries addressing reimbursement challenges, will enhance our insights. It was difficult to follow standards for qualitative research analyses due to poor response rates and inability to reach data saturation.

A discussion of LNHA’s opinions on improving retention and turnover rates should include more accountability, personal responsibility, and adding more opportunities for professional growth and development. Focusing on targeted questions to comprehend the experiences of STNAs in the LTC setting may facilitate the development of educational interventions aimed at improving STNA retention. Studies such as those conducted by Castle et al. (2007a), Rosen et al. (2011), and Morgan et al. (2013) produced results pertaining to factors that influenced job satisfaction and turnover rates; however, the current day and age lies under different circumstances and working conditions in healthcare, and the educational intervention component was not addressed in any of the mentioned papers.

To improve cohesion in LTC facilities, educating STNAs and DCWs about the reimbursement and administrative challenges confronted by LNHAs is essential. Transparency and education can foster better teamwork and address issues related to wages and the support sought by STNAs from management. A lack of understanding of the LNHAs’ role by STNAs leads to feelings of inadequate support from management. Further investigation into how much of a limitation reimbursement causes facilities is needed.

An aspect not considered during the pilot was the type of facility where the DCWs were employed. Huang and Bowblis (2019) found that owner-managed nursing homes in Ohio have higher nursing staff levels but do not show better quality or financial performance compared to non-owner-managed facilities. It would be valuable to assess job satisfaction and retention in owner-managed versus non-owner-managed facilities. Future research should also include examination of facilities by size, and profit vs. non-profit statuses and satisfaction.

The COVID-19 implications will also be beneficial for programs to increase job retention in the healthcare workforce. Demographic information was not collected from individuals who took the surveys, so future research should also take demographics into consideration to determine if it influences responses to the questions asked in both surveys.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the DePizzo Endowed Chair of Gerontology at Youngstown State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Youngstown State University IRB approved our study (#2022-116). Ohio BELTSS provided their contact list of all currently licensed nursing home administrators in Ohio for this study. Informed consent was collected electronically.

ORCID iDs: Rachel E. Ward  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7810-890X

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7810-890X

Daniel J. Van Dussen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8331-013X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8331-013X

References

- Bergman R., Eckerling S., Golander H., Sharon R., Tomer A. (1984). Staff composition, job perceptions and work retention of nursing personnel in geriatric institutions. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 21(4), 279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowblis J., Applebaum R. (2017). How does medicaid reimbursement impact nursing home quality? The effects of small anticipatory changes. Health Services Research, 52, 1729–1748. 10.1111/1475-6773.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier J. F., Geng F., Meehan A., White E. M., McGarry B. E., Shield R. R., Grabowski D. C., Rahman M., Santostefano C., Gadbois E. A. (2023). Examination of staffing shortages at US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 6(7), e2325993. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant N. S., Cimarolli V. R., Falzarano F., Stone R. (2023). Organizational factors associated with certified nursing assistants’ job satisfaction during COVID-19. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 42(7), 1574–1581. 10.1177/07334648231155017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle N. G., Engberg J., Anderson R., Men A. (2007. a). Job satisfaction of nurse aides in nursing homes: Intent to leave and turnover. The Gerontologist, 47(2), 193–204. 10.1093/geront/47.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle N. G., Engberg J., Men A. (2007. b). Nursing home staff turnover: Impact on nursing home compare quality measures. The Gerontologist, 47(5), 650–661. 10.1093/geront/47.5.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G., Bitton J., Allgeyer R., Elliott D., Hudson L., Moulton Burwell P. (2021). The impact of covid-19 on the nursing workforce: A national overview. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(2). 10.3912/ojin.vol26no02man02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cimarolli V. R., Bryant N. S., Falzarano F., Stone R. (2022). Factors associated with nursing home direct care professionals’ turnover intent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatric Nursing, 48, 32–36. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Poth C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gambaro E., Gramaglia C., Marangon D., Probo M., Rudoni M., Zeppegno P. (2023). Health workers’ Burnout and COVID-19 pandemic: 1-year after-results from a repeated cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6087. 10.3390/ijerph20126087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings R. P., Horne S., Mitchell G. (2004). Burnout in direct care staff in intellectual disability services: A factor analytic study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48(3), 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. S., Bowblis J. R. (2019). Private equity ownership and nursing home quality: An instrumental variables approach. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 19(3–4), 273–299. 10.1007/s10754-018-9254-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy K. A., Abbott K. M., Bowblis J. R. (2022). The one-two punch of high wages and empowerment on CNA retention. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(2), 312–321. 10.1177/07334648211035659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. (2020). Occupational credentials and job qualities of direct care workers: Implications for labor shortages. Journal of Labor Research, 41(4), 403–420. 10.1007/s12122-020-09312-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levere M., Rowan P., Wysocki A. (2021). The adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing home resident well-being. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(5), 948–954.e2. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark T., Engström M., Trygged S. (2023). Psychosocial work environment and well-being of direct-care staff under different nursing home ownership types: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 42(2), 347–359. 10.1177/07334648221131468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin S., Wilson J. (2004). Minimum wages in a low-wage labour market: Care homes in the UK. The Economic Journal, 114(494), C102–C109. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3590311 [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Leiter M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(2), 103–111. 10.1002/wps.20311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M., Scommegna P. (2024). Fact sheet: Aging in the United States. Population Reference Bureau. https://www.prb.org/resources/fact-sheet-aging-in-the-united-states/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20Americans%20ages,from%2017%25%20to%2023%25.&text=The%20U.S%20population%20is%20older%20today%20than%20it%20has%20ever%20been.

- McHenry P., Mellor J. M. (2022). The impact of recent state and local minimum wage increases on nursing facility employment. Journal of Labor Research, 43(3–4), 345–368. 10.1007/s12122-022-09338-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. C., Dill J., Kalleberg A. L. (2013). The quality of healthcare jobs: Can intrinsic rewards compensate for low extrinsic rewards? Work, Employment, and Society, 27(5), 802–822. 10.1177/0950017012474707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohio BELTSS. (2023). Licensing. Ohio Board of Executives of Long-Term Services and Supports. https://beltss.ohio.gov/licensing#:~:text=The%20Ohio%20Board%20of%20Executives,Degree%20from%20an%20accredited%20college. [Google Scholar]

- Potter S. J., Churilla A., Smith K. (2006). An examination of full-time employment in the direct-care workforce. The Journal of Applied Gerontology, 25(5), 356–374. 10.1177/0733464806292227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Nogueira Ó., Leirós-Rodríguez R., Pinto-Carral A., Álvarez-Álvarez M. J., Fernández-Martínez E., Moreno-Poyato A. R. (2022). The relationship between burnout and empathy in physiotherapists: A cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine, 54(1), 933–940. 10.1080/07853890.2022.2059102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollison J., Bandini J., Feistel K., Gittens A. D., Key M., González I., Kong W., Ruder T., Etchegaray J. M. (2023). An evaluation of a multisite, health systems-based direct care worker retention program: Key findings and recommendations. Rand Health Quarterly, 10(2), 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J., Stiehl E. M., Mittal V., Leana C. R. (2011). Stayers, leavers, and switchers among certified nursing assistants in nursing homes: A longitudinal investigation of turnover intent, staff retention, and turnover. The Gerontologist, 51(5), 597–609. 10.1093/geront/gnr025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth M., Palmer L., Bercaw L., Voltmer H., Karon S. L. (2022). Trends in the use of residential settings among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77(2), 424–428. 10.1093/geronb/gbab092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Occupational outlbureaook handbook: Fastest growing occupations. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/fastest-growing.htm

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). QuickFacts Ohio. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/OH/AGE775222

- Vadean F., Allan S. (2021). The effects of minimum wage policy on the long-term care sector in England. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 59(2), 307–334. 10.1111/bjir.12572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R. E., Van Dussen D. J., Weaver A., Cook A. G. (under review). A comparison of sociodemographic factors during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout among U.S. long-term care workers using a theoretical lens application. [Google Scholar]