Abstract

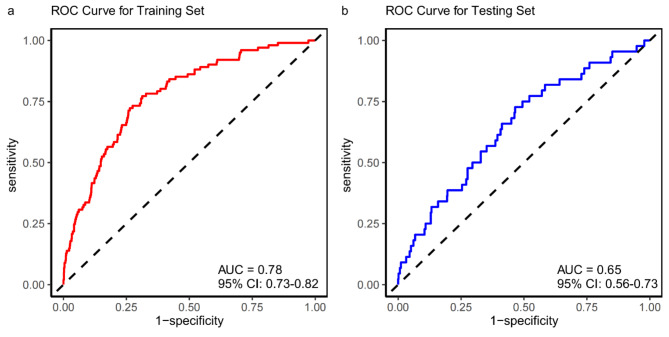

Asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (aICAS) is a major risk factor for cerebrovascular events. The study aims to construct and validate a nomogram for predicting the risk of aICAS. Participants who underwent health examinations at our center from September 2019 to August 2023 were retrospectively enrolled. The participants were randomly divided into a training set and a testing set in a 7:3 ratio. Firstly, in the training set, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression and multivariate logistic regression were performed to select variables that were used to establish a nomogram. Then, the receiver operating curves (ROC) and calibration curves were plotted to assess the model’s discriminative ability and performance. A total of 2563 neurologically healthy participants were enrolled. According to LASSO-Logistic regression analysis, age, fasting blood glucose (FBG), systolic blood pressure (SBP), hypertension, and carotid atherosclerosis (CAS) were significantly associated with aICAS in the multivariable model (adjusted P < 0.005). The area under the ROC of the training and testing sets was, respectively, 0.78 (95% CI: 0.73–0.82) and 0.65 (95% CI: 0.56–0.73). The calibration curves showed good homogeneity between the predicted and actual values. The nomogram, consisting of age, FBG, SBP, hypertension, and CAS, can accurately predict aICAS risk in a neurologically healthy population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74393-6.

Keywords: Asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis, Nomogram, LASSO-Logistic regression, Neurologically healthy population

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Diseases, Health care, Medical research, Neurology, Risk factors

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, not only resulting in severe sequelae but also exacerbating the global burden of disease1. Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) is a primary cause of stroke. Compared with other causes, ICAS is also the most important risk factor for recurrence stroke2,3. ICAS accounts for 50% of ischemic strokes in Asia and about 10% in the US4,5. ICAS mainly occurs in Asians, African Americans, and Hispanic Americans6,7. However, studies on asymptomatic ICAS (aICAS) are relatively limited, and considering the covert onset of aICAS and its high prevalence, more clinical attention is needed for populations with aICAS.

aICAS not only poses a risk for cerebrovascular events but also increases in risk with the degree of stenosis. Some studies have shown that long-term exposure to vascular risk factors, especially uncontrolled or more severe risk factors, directly impacts the presence of ICAS and related vascular events8.

The prevalence of aICAS mainly depends on the different study populations and screening methods. In a Chinese study of a community-based population using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (HR-MRI) to assess the degree of ICAS, it was found that about 12.08% of patients had ≥ 50% aICAS; moreover, compared to patients without aICAS, patients with aICAS of 50–69% and ≥ 70% had a nearly 3.5-fold and 5-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke, respectively9. The ARIC study showed that about 9% of the American population had ≥ 50% aICAS10.The Barcelona-aICAS study, targeting patients with medium-high vascular risk but no stroke or coronary artery disease, used transcranial color-coded duplex (TCCD) ultrasound to assess their intracranial arteries. In this study, researchers found that 9% of the patients had aICAS. Compared to structural arterial imaging methods such as magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), the TCCD method may underestimate its prevalence in high-risk populations11. In the OXVASC study, which included patients with transient cerebral ischemia (TIA) or mild stroke, 4.2% had symptomatic ICAS and 11.3% had aICAS. Moreover, the 7-year risk of recurrent ischemic stroke was 6.8% in the aICAS population12.

Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that aICAS is also a risk factor for asymptomatic cerebral infarction, cognitive impairment, and dementia2,13,14. Nevine et al. found a higher incidence of cognitive impairment in patients with aICAS, and they exhibit executive dysfunction15. The ARIC study showed that aICAS is independently associated with cognitive impairment and dementia in whites16.

Previous studies have explored the risk scores for asymptomatic carotid stenosis (ACS)17, but research on predictive models for aICAS is limited. The purpose of this study is to analyze the risk factors for aICAS in a neurologically healthy population, establish a nomogram prediction model, and evaluate the model.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study screened participants who had a health check-up at the Health Management Center of Beijing Tiantan Hospital from September 2019 to August 2023 (N = 3,853). The health examinations included questionnaire surveys, physical examinations, laboratory tests, standard carotid ultrasound and superb microvascular imaging (SMI) examinations, and MRA.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of central nervous system disease (such as cerebrovascular disease, including cerebral infarction, TIA, cerebral hemorrhage, etc.) (N = 137); (2) incomplete laboratory indicators (N = 1005); (3) incomplete carotid ultrasound and/or SMI examination (N = 148).

A total of 2563 neurologically healthy participants were ultimately included in the analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital. All participants have signed written informed consent forms.

Clinical assessment

Extensive evaluations were conducted for demographic data, clinical factors, cerebrovascular risk factors, laboratory factors, and intracranial and extracranial atherosclerosis, including sex, age, height, weight, waist circumference, hip circumference, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, and smoking history. Venous blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein after an overnight fast of at least 8 h. All blood samples were tested in the clinical laboratory of Beijing Tiantan Hospital using an automatic analyzer (Hitachi 008/008AS; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with strict quality control. Laboratory tests include total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), remnant cholesterol (RC), Non-HDL-C, apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), various lipid ratios, fasting blood glucose (FBG), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum creatinine (Scr), homocysteine (HCY), uric acid (UA), thyroid hormones (TH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Non-HDL-C was calculated using the following formula: Non-HDL-C = TC - HDL-C18. RC was calculated using the following formula: RC = Non-HDL-C - LDL-C19.

Hypertension was defined as a self-reported history of hypertension or the use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus was characterized by a self-reported history of diabetes, the use of hypoglycemic medication, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%,20or glycated albumin (GA) ≥ 17.1%. Dyslipidemia was defined as the use of lipid-lowering medication or a self-reported history of dyslipidemia. The definition of cardiovascular disease followed the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology21. Smoking status was categorized into two groups: past and current smokers, or never smokers. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was determined by the formula: waist circumference (cm) / hip circumference (cm).

Imaging procedures

Extracranial artery atherosclerosis was assessed using ultrasound scanning with a high-resolution ultrasound system (Aplio A500, Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Japan) and equipped with an 11L4 linear array probe (frequency range 4–11 MHz) for routine carotid vascular ultrasound and SMI examinations. The vessels examined included both the carotid arteries (common carotid artery, carotid bifurcation, internal carotid artery, and external carotid artery) of the participants.

Intima-media thickness (IMT) refers to the distance between the lumen-intima interface and the intima-media interface on the longitudinal images of the walls on both sides of the common carotid artery. Carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) is defined as an average IMT of 1.00 mm or greater at 1 cm below the far wall of the bilateral common carotid artery. Carotid plaque (CP) is defined as a focal structure with a cIMT ≥ 1.5 mm19,22,23. After examining the carotid plaque, further SMI examination is performed for patients with CP. SMI is an advanced ultrasound imaging technique that can further determine the presence of unstable carotid plaque (UCP) by displaying blood flow signals within the plaque24,25.

The diagnostic criteria for aICAS were based on MRA scans performed on a 3T Siemens scanner following a standardized protocol26. Three-dimensional time-of-flight (TOF) MRA to evaluate the intracranial stenosis, including the supraclinoid and cavernous segments of the bilateral internal carotid artery (ICA), middle cerebral artery (MCA, M1-M4), anterior cerebral artery (ACA, A1-A3), vertebral artery (VA, V4), posterior cerebral artery (PCA, P1-P3), and basilar artery10.

Each artery and region were visually inspected to determine the need for further measurement of diameter. If intracranial artery stenosis was detected, the degree of stenosis was measured using the criteria established in the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial, with the stenosis percentage calculated as % = [(1-(diameter at the most severe stenosis site/normal diameter of the proximal artery)] *100. The grading criteria for intracranial vascular stenosis were recorded in order of no detectable stenosis, < 50%, 50-70%, 71-99%, and occlusion10,26,27. aICAS was defined as intracranial artery stenosis ≥ 50%. Two neurologists independently evaluated the MRA of each participant, blinded to the participants’ medical history and laboratory indicators, with a kappa value of 0.852.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The study population of 2563 was randomly divided into a training set (N = 1749) and a testing set (N = 769) in a 7:3 ratio. Continuous variables were expressed as medians (interquartile range, IQR) and compared using the Wilcoxon test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage) and compared using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. In order to evaluate the ability and accuracy of clinical baseline indicators in identifying aICAS, the receiver operating curves (ROC) curves were plotted, and the area under curve (AUC), 95% confidence interval (CI), best threshold, sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were calculated.

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis is a shrinkage and variable selection method for linear regression models. In order to obtain a subset of predictors, LASSO regression analysis imposes constraints on model parameters, causing some variable coefficients to shrink to zero, thereby minimizing the prediction error of quantitative response variables. Variables with zero coefficients after the shrinkage process are excluded from the model, while variables with non-zero coefficients are most strongly associated with the response variable. Based on the − 2 log-likelihood and binomial family type measure, LASSO regression analysis was performed in R software with centralized and normalized variables, followed by 20-fold cross-validation to select the optimal best lambda value. “Lambda.lse” provided a model with good performance and the smallest number of independent variables28. Therefore, in the training set, LASSO regression was used to select the best predictors from clinical baseline indicators. Subsequently, the selected variables were introduced into a multivariate logistic regression analysis to further assess the variable’s efficacy by calculating the odds ratio (OR), 95% CI, and P values, thereby establishing a nomogram prediction model.

Based on this, two validation methods were used to assess the accuracy of the risk prediction model using data from the training set and the testing set. The AUC value was used to determine the discriminative ability of the risk nomogram. Internal verification was performed using the bootstrap method (1000 times), and the calibration curves were drawn to evaluate the consistency of the model, assessing the calibration effect of the aICAS risk nomogram. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to assess the clinical utility of the model. In all tests, a two-sided P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical baseline characteristics

A total of 2563 neurologically healthy participants were enrolled in the study, 5.66% (145/2563) were diagnosed with aICAS according to the WASID method. The participants in this study had a median age of 52 years (IQR: 44–58 years); 61.33% (1572/2563) were male; 26.06% had hypertension; 12.64% had diabetes mellitus; 2.85% had cardiovascular disease; 8.97% had dyslipidemia; 29.73% had a smoking history; 18.10% had cIMT; 33.94% had CP; and 1.76% had UCP.

In the study, 1794 and 769 participants, respectively, were included in the training set and testing set according to a randomized sampling ratio of 7:3. The prevalence of aICAS was respectively 5.63% (101/1794) and 5.72% (44/769) in the training and testing sets. Table 1 presents the clinical baseline characteristics of the participants in both groups. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups across all included variables (P > 0.05), indicating that the grouping was conducted in a randomized and reasonable manner.

Table 1.

Clinical baseline characteristics in the training and testing sets.

| Variables | Total (n = 2563) | Training set (n = 1794) | Testing set (n = 769) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 1572 (61.33) | 1100 (61.32) | 472 (61.38) | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 52 (44–58) | 52 (44–58) | 52 (45–58) | 0.638 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.41 (23.21–27.77) | 25.39 (23.14–27.70) | 25.43 (23.46–27.90) | 0.298 |

| WHR | 0.90 (0.84–0.94) | 0.89 (0.84–0.94) | 0.90 (0.85–0.94) | 0.462 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 127 (116–138) | 127 (116–138 | 128 (116–139) | 0.353 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81 (73–89) | 81.00 (73–89) | 82 (73–89) | 0.339 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.89 (4.30–5.49) | 4.89 (4.30–5.52) | 4.89 (4.28–5.44) | 0.385 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.32 (0.92–1.98) | 1.31 (0.92-2.00) | 1.33 (0.91–1.93) | 0.611 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.04 (2.47–3.59) | 3.05 (2.46–3.62) | 3.04 (2.49–3.52) | 0.238 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.33 (1.14–1.55) | 1.34 (1.14–1.57) | 1.31 (1.15–1.52) | 0.323 |

| RC (mmol/L) | 0.42 (0.29–0.58) | 0.41 (0.29–0.58) | 0.43 (0.30–0.60) | 0.319 |

| Non-HDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.52 (2.95–4.09) | 3.52 (2.95–4.10) | 3.53 (2.94–4.06) | 0.537 |

| ApoA1 (g/L) | 1.41 (1.26–1.57) | 1.41 (1.26–1.58) | 1.41 (1.26–1.55) | 0.216 |

| ApoB (g/L) | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.481 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.64 (3.05–4.29) | 3.65 (3.05–4.30) | 3.64 (3.05–4.25) | 0.994 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 0.99 (0.62–1.63) | 0.98 (0.61–1.65) | 1.00 (0.63–1.58) | 0.889 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C ratio | 2.28 (1.76–2.80) | 2.29 (1.76–2.82) | 2.26 (1.77–2.78) | 0.545 |

| Non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratio | 2.64 (2.05–3.29) | 2.65 (2.05–3.30) | 2.64 (2.05–3.25) | 0.994 |

| RC/HDL-C ratio | 0.31 (0.20–0.48) | 0.31 (0.20–0.47) | 0.32 (0.21–0.50) | 0.293 |

| ApoB/HDL-C ratio | 0.71 (0.55–0.88) | 0.71 (0.55–0.88) | 0.72 (0.55–0.88) | 0.913 |

| TC/ApoA1 ratio | 3.45 (2.96–3.95) | 3.45 (2.95–3.95) | 3.44 (2.97–3.93) | 0.638 |

| TG/ApoA1 ratio | 0.95 (0.62–1.50) | 0.95 (0.61–1.51) | 0.95 (0.62–1.48) | 0.919 |

| LDL-C/ApoA1 ratio | 2.15 (1.72–2.60) | 2.16 (1.71–2.62) | 2.13 (1.73–2.56) | 0.383 |

| Non-HDL-C/ApoA1 ratio | 2.49 (1.99–2.99) | 2.50 (1.99-3.00) | 2.49 (2.00-2.96) | 0.753 |

| RC/ApoA1 ratio | 0.30 (0.19–0.44) | 0.29 (0.19–0.44) | 0.30 (0.20–0.46) | 0.204 |

| ApoB/ApoA1 ratio | 0.67 (0.54–0.80) | 0.67 (0.54–0.81) | 0.67 (0.54–0.79) | 0.808 |

| HCY (µmol/L) | 12.24 (10.2-14.96) | 12.34 (10.20-15.14) | 12.02 (10.16–14.53) | 0.114 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 4.95 (4.62–5.48) | 4.96 (4.62–5.48) | 4.93 (4.63–5.49) | 0.571 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 115.71 (108.61-123.32) | 115.70 (108.70-123.08) | 115.73 (108.46-123.69) | 0.484 |

| Scr (µmol/L) | 61.1 (51.8–70.10) | 61.10 (51.80–70.20) | 61.10 (52.00-69.80) | 0.478 |

| UA (µmol/L) | 340.90 (276.50-405.60) | 342.55 (278.90-406.20) | 335.10 (271.50-402.60) | 0.137 |

| TSH (µlµ/mL) | 1.84 (1.32–2.61) | 1.84 (1.32–2.55) | 1.84 (1.33–2.68) | 0.376 |

| TH (nmol/L) | 107.51 (96.35-119.08) | 107.51 (96.27–119.10) | 107.20 (96.52-118.91) | 0.527 |

| CP thick (mm) | 1.10 (0.00-1.80) | 1.10 (0.00-1.80) | 1.10 (0.00-1.90) | 0.316 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 668 (26.06) | 473 (26.37) | 195 (25.36) | 0.629 |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 324 (12.64) | 232 (12.93) | 92 (11.96) | 0.541 |

| Cardiovascular disease, N (%) | 73 (2.85) | 49 (2.73) | 24 (3.12) | 0.679 |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 230 (8.97) | 158 (8.81) | 72 (9.36) | 0.707 |

| Smoking history, N (%) | 762 (29.73) | 540 (30.10) | 222 (28.87) | 0.563 |

| CAS, N (%) | 0.994 | |||

| 0 | 1229 (47.95) | 859 (47.88) | 370 (48.11) | |

| cIMT | 464 (18.10) | 325 (18.12) | 139 (18.08) | |

| CP | 870 (33.94) | 610 (34.00) | 260 (33.81) | |

| UCP, N (%) | 45 (1.76) | 33 (1.84) | 12 (1.56) | 0.742 |

| aICAS, N (%) | 145 (5.66) | 101 (5.63) | 44 (5.72) | 1.000 |

BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RC, remnant cholesterol; Non-HDL-C, non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ApoA1, apolipoprotein A-1; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; HCY, homocysteine; FBG, fasting blood glucose; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Scr, serum creatinine; UA, uric acid; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; TH, thyroid hormones; CP, carotid plaque; CAS, carotid atherosclerosis; cIMT, carotid intima–media thickness; UCP, unstable carotid plaque; aICAS, asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis.

Table 2 illustrates the comparative analysis of clinical baseline indicators between the groups with and without aICAS in the training set. In this cohort, participants diagnosed with aICAS at baseline were older and exhibited higher levels of BMI, WHR, SBP, DBP, HCY, FBG, and eGFR. Moreover, these individuals were more likely to have thicker CP, hypertension, diabetes, and carotid atherosclerosis (CAS) compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Conversely, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups for other indicators, such as gender, TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C, RC, Non-HDL-C, ApoA1, ApoB, lipid ratios, Scr, UA, TSH, TH, cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidemia, UCP, and the history of smoking (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between the without and with aICAS groups in the training set.

| Variables | Without aICAS (n = 1693) | With aICAS (n = 101) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 1034 (61) | 66 (65) | 0.453 |

| Age (years) | 51 (43–57) | 58 (53–64) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.36 (23.1-27.63) | 26.33 (24.02–28.26) | 0.007 |

| WHR | 0.89 (0.84–0.94) | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 126 (116–137) | 140 (124–149) | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81 (73–88) | 85 (76–91) | 0.003 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.88 (4.3–5.51) | 4.97 (4.40–5.52) | 0.475 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.31 (0.92-2.00) | 1.46 (1.10–2.03) | 0.116 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.03 (2.46–3.62) | 3.22 (2.63–3.78) | 0.186 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.34 (1.14–1.57) | 1.30 (1.08–1.53) | 0.151 |

| RC (mmol/L) | 0.41 (0.29–0.57) | 0.45 (0.29–0.63) | 0.277 |

| Non-HDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.52 (2.93–4.10) | 3.60 (3.18–4.15) | 0.177 |

| ApoA1 (g/L) | 1.42 (1.26–1.58) | 1.39 (1.23–1.56) | 0.179 |

| ApoB (g/L) | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 0.95 (0.88–1.09) | 0.086 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.63 (3.05–4.29) | 3.76 (3.28–4.38) | 0.103 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 0.98 (0.61–1.65) | 1.07 (0.73–1.67) | 0.105 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C ratio | 2.29 (1.75–2.81) | 2.33 (1.98–2.94) | 0.065 |

| Non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratio | 2.63 (2.05–3.29) | 2.76 (2.28–3.38) | 0.103 |

| RC/HDL-C ratio | 0.30 (0.19–0.47) | 0.33 (0.20–0.54) | 0.251 |

| ApoB/HDL-C ratio | 0.71 (0.54–0.88) | 0.77 (0.60–0.90) | 0.049 |

| TC/ApoA1 ratio | 3.45 (2.94–3.95) | 3.55 (3.23–3.98) | 0.122 |

| TG/ApoA1 ratio | 0.95 (0.61–1.51) | 1.02 (0.76–1.53) | 0.091 |

| LDL-C/ApoA1 ratio | 2.16 (1.69–2.61) | 2.27 (1.94–2.75) | 0.085 |

| Non-HDL-C/ApoA1 ratio | 2.49 (1.98–2.99) | 2.56 (2.26–3.07) | 0.107 |

| RC/ApoA1 ratio | 0.29 (0.19–0.44) | 0.32 (0.19–0.48) | 0.229 |

| ApoB/ApoA1 ratio | 0.67 (0.53–0.80) | 0.70 (0.59–0.82) | 0.054 |

| HCY (µmol/L) | 12.25 (10.16–15.07) | 13.2 (10.64–16.35) | 0.029 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 4.95 (4.61–5.43) | 5.23 (4.81–6.53) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 115.97 (108.94-123.36) | 112.43 (102.19-117.09) | < 0.001 |

| Scr (µmol/L) | 61.10 (51.80–70.20) | 59.80 (52.30–69.40) | 0.769 |

| UA (µmol/L) | 342.10 (277.90-406.20) | 351.90 (287.20–406.00) | 0.328 |

| TSH (µlµ/mL) | 1.84 (1.33–2.55) | 1.84 (1.28–2.48) | 0.929 |

| TH (nmol/L) | 107.51 (95.96-119.08) | 108.96 (100.53–119.10) | 0.092 |

| CP thick (mm) | 1.10 (0.00-1.80) | 1.40 (0.00-2.10) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 420 (25) | 53 (52) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 203 (12) | 29 (29) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease, N (%) | 45 (3) | 4 (4) | 0.352 |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 149 (9) | 9 (9) | 1.000 |

| Smoking history, N (%) | 503 (30) | 37 (37) | 0.173 |

| CAS, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 841 (50) | 18 (18) | |

| cIMT | 311 (18) | 14 (14) | |

| CP | 541 (32) | 69 (68) | |

| UCP, N (%) | 29 (2) | 4 (4) | 0.111 |

BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RC, remnant cholesterol; Non-HDL-C, non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ApoA1, apolipoprotein A-1; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; HCY, homocysteine; FBG, fasting blood glucose; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Scr, serum creatinine; UA, uric acid; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; TH, thyroid hormones; CP, carotid plaque; CAS, carotid atherosclerosis; cIMT, carotid intima–media thickness; UCP, unstable carotid plaque.

Predicting the value of baseline characteristics for aicas

We assessed the predictive ability of baseline indicators for aICAS, calculating the AUC, 95%CI, best threshold, sensitivity, specificity, PLR, and NLR (Table S1). Age and CAS had the best AUC values, respectively: age (AUC = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.64–0.73), with the best threshold at 52.50, sensitivity, and specificity at 74% and 54%, respectively; and CAS (AUC = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.63–0.71), with sensitivity and specificity at 62% and 68%, respectively (Table S1).

Variable selection for the prediction model

All 41 biomarkers in the study were considered potential predictive factors for aICAS. We established a LASSO-Logistic regression prediction model in the training set with aICAS as the dependent variable, employing the LASSO regression algorithm to select variables, choosing the best λ value through 20-fold cross-validations (Fig. S1). The two dashed lines in Figure S1a represent, respectively, lambda.min and lambda.1-standard error. We used lambda.1se to screen the variables. Thus, the most streamlined predictive model is obtained by combining the fewest variables while ensuring fit. Fig. S1b shows that the LASSO regression selected 5 variables with non-zero coefficients, including age, SBP, FBG, hypertension, and CAS.

Construction and validation of the nomogram

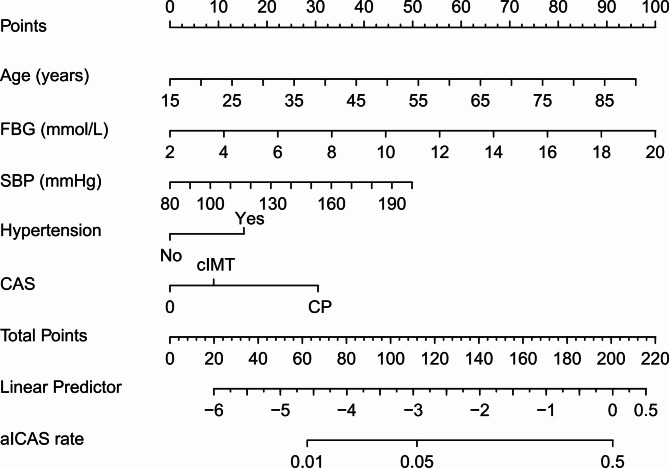

The five selected variables were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis, revealing age (P < 0.001), SBP (P = 0.040), FBG (P < 0.001), hypertension (P = 0.029), and CP (P < 0.001) were significantly and independently associated with aICAS in neurologically healthy participants (Table 3). Therefore, age, SBP, FBG, hypertension, and CAS were subsequently selected to construct the nomogram for risk prediction (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the selected indicators in the training set.

| Variables | β | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.041 | 1.81 (1.30–2.53) | <0.001 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.012 | 1.35 (1.01–1.81) | 0.040 | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 0.184 | 1.17 (1.07–2.61) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 0.506 | 1.66 (1.05–2.61) | 0.029 | |

| CAS, N (%) | ||||

| cIMT | 0.299 | 1.35 (0.65–2.80) | 0.424 | |

| CP | 1.012 | 2.75 (1.54–4.93) | <0.001 | |

Fig. 1.

Nomogram for prediction of aICAS in neurologically healthy participants. For each variable, a vertical line was drawn from its respective axis upwards to intersect the corresponding score line to determine the score associated with that variable. The individual scores for all variables were then added together to arrive at a total score. A vertical line was subsequently drawn from the total score axis downward to intersect the probability axis to determine the predicted probability of the aICAS. aICAS, asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis; FBG, fasting blood glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; CAS, carotid atherosclerosis; cIMT, carotid intima–media thickness; CP, carotid plaque.

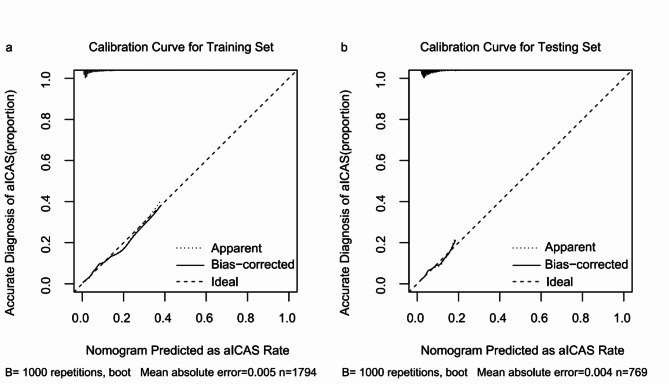

AUC, calibration curve, and DCA were used to assess the performance of the model. In the training set, the model demonstrated moderate discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.73–0.82) (Fig. 2a). The calibration curve analysis further showed that the model’s predictions were highly aligned with the actual aICAS incidence rates, especially after applying bias correction (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the DCA indicated that the model offered significant net benefits across a certain range of threshold probabilities, affirming its potential utility in clinical practice for aICAS risk assessment (Fig. S2a).

Fig. 2.

ROC Curve for the probability of aICAS occurrence of the nomogram in the training and testing sets. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; aICAS, asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis.

Fig. 3.

Calibration curves for aICAS risk nomograms in the training and testing sets. The x-axis indicates the predicted risk of aICAS and the y-axis reflects the actual diagnosed cases of aICAS. “Ideal” represents the optimum predictive performance, “Apparent” means the predicted probability curve fitted by the nomogram model, and “Bias-corrected” means the predicted probability curve adjusted for overfitting.

Within the testing set, the model exhibited a diminished discriminative capacity, with a C-index of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.57–0.73), which, while lower, still demonstrated adequate differentiation capabilities (Fig. 2b). The calibration curve in this set suggested that the model’s predictions were reasonably accurate across low to moderate predictive probability ranges, though an upward deviation was observed at higher risk thresholds, reflecting a tendency toward overestimation in these cases (Fig. 3b). Despite this, the DCA in the testing set (Fig. S2b) showed that the model offered clinical benefits at lower-risk thresholds, although these benefits diminished across higher threshold ranges.

Discussion

This study developed and validated a nomogram predicting aICAS risk based on a neurologically healthy population. A total of 2,563 participants were included in the study, of whom approximately 5.66% had aICAS. To overcome the limitations of traditional logistic regression analysis in predicting factors due to overfitting and skewed distribution, we applied LASSO-Logistic to screen predictors independently associated with aICAS. Notably, through the use of multivariable regression analysis, this study controlled for multiple potential confounding factors. The advantage of this approach lies in its ability to simultaneously account for several covariates, thereby providing a more accurate assessment of each variable’s relationship with aICAS. This method reduces the risk of confounding effects that may arise in univariable analyses, resulting in findings with greater interpretative power and clinical significance. The results showed that age, FBG, SBP, hypertension, and CAS were significantly associated with aICAS in the multivariable model after controlling for other covariates. We further used the above variables to construct a nomogram for the risk of aICAS in neurologically healthy populations. Based on the AUC value and calibration plot results, the nomogram demonstrated good discrimination and calibration in predicting the risk of aICAS, indicating its high clinical value. DCA further indicated that this prediction model provided significant net benefits within some threshold probability ranges. These findings underscore the nomogram’s potential as a practical tool for clinicians to stratify risk and identify neurologically healthy individuals at higher risk for aICAS, thereby aiding in timely preventive interventions.

Our study found that age, FBG, SBP, and hypertension were independent risk factors for the occurrence of aICAS in a neurologically healthy population, which is consistent with previous research findings. Age is one of the unmodifiable risk factors for aICAS. Robert et al. indicated that in Caucasian patients with TIA and mild strokes, the prevalence of aICAS increased with age12. Previous studies have shown that older age and the history of hypertension were significantly associated with aICAS, and this correlation persisted after further adjusting for confounding factors8,12. Wang et al. found that the FBG concentrations of ICAS patients were significantly higher than in non-ICAS patients, and FBG was an independent risk factor for aICAS29. High levels of FBG may increase the risk of aICAS due to hyperglycemia, which can lead to endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress, which in turn promote the formation and progression of atherosclerotic plaques30,31. It was shown that in patients with hypertension, aICAS patients have significantly higher morning SBP. And morning SBP had a significant and independent correlation with aICAS32. In summary, the longer the duration of hypertension, the greater the damage to intracranial vessels and brain tissue33,34. Therefore, for aICAS patients, controlling above-modifiable risk factors to clinical standards is an important strategy to delay the progression of aICAS and the occurrence of clinical events.

Moreover, the results of this study showed that CP was an independent risk factor for aICAS and was the strongest among all risk factors. When CP occurred, the incidence of aICAS increased by 2.75-fold (OR = 2.75, 95% CI: 1.54–4.93). Atherosclerosis is a cholesterol-mediated disease, and its core pathological process is the deposition of cholesterol in the arterial wall. The severity of atherosclerosis is considered to be linearly progressive13. Growing evidence indicates that patients with ICAS have a correlation with CAS and peripheral arterial disease (PAD)35,36. Recently, a cohort study of a community-based population indicated that, after adjusting for traditional risk factors, CP was a significant and independent indicator for the progression of aICAS (OR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.06–3.92)37. In another study, the results showed that the burden of CP was significantly correlated with severe intracranial artery stenosis, indicating that the load of plaques in the extracranial carotid artery could serve as an independent risk factor for it35. In a single-center, prospective cohort study, a two-year follow-up of aICAS patients found that lipid-lowering treatment to control LDL-C levels to ≤ 1.8 mmol/L or reduce by ≥ 50% from baseline can improve aICAS, indicating that intensified lipid-lowering treatment had a significant therapeutic effect on the regression of aICAS38. However, in our study, no significant and independent correlation was found between blood lipids and aICAS. On one hand, this may be because other factors had more significant impacts in the LASSO-Logistic regression analysis. On the other hand, it may be related to the characteristics of the study population, where the prevalence of dyslipidemia was only 8.97% and the study population consists of individuals with healthy nervous systems and no history of stroke or other neurological diseases.

Given the limited research on predictive models for aICAS, we tried to compare the distinct risk factors between aICAS and ACS. By identifying both shared and differing risk factors between these two conditions, we further clarify the value of the model presented in this study. A recent study targeting subjects undergoing vascular disease screening in an outpatient clinic constructed a risk prediction model for detecting ACS with a narrowing degree of ≥ 50% and 70% through multivariable logistic regression variable selection. The study results indicated that age, sex, SBP, DBP, TC/HDL-C ratio, smoking history, diabetes mellitus, stroke/TIA, cardiovascular disease, and PAD were independent risk factors for ACS17. In our study, age, FBG, SBP, hypertension, and CP were independently associated with aICAS. We discovered that aICAS and ACS may share common risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as age and SBP. However, there are also some differing factors between the two, such as sex and PAD. The discrepancies may be attributed to several reasons: firstly, the populations included in the two studies differ, and the evaluation of atherosclerosis risk factors varies; secondly, the statistical methods differ, with the ACS model utilizing traditional multivariable logistic regression for variable selection. Finally, although ACS and aICAS are manifestations of atherosclerosis in different vascular locations, they may be influenced by risk factors to varying extents during their occurrence and development. Therefore, future research should further explore the underlying mechanisms of intracranial and extracranial arterial atherosclerosis.

Notably, in this study, we observed a notable difference in the AUC values between the training set (0.78) and the testing set (0.65). This discrepancy may indicate potential overfitting of the model to the training data, where it captured specific patterns or noise that did not generalize well to the unseen validation data. Furthermore, subtle differences in data distribution between the training and validation sets might have impacted the model’s generalization ability. Overfitting is a common challenge in predictive modeling, particularly when model complexity is high or sample sizes are limited. Even though LASSO-logistic regression and cross-validation were used to reduce overfitting, the results didn’t show a big improvement. This suggests that there are deeper problems that need to be carefully thought through in future model development. Additionally, exploring other machine learning approaches or parameter optimization may offer potential solutions to address these challenges.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the target population of this study was a neurologically healthy population, and this was a single-center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size that lacked external testing from other institutions. Therefore, its generalization to other populations may be limited, and future testing is needed in large-sample, multi-center, prospective studies. Secondly, the indicators measured in the study were only measured once, which may not fully reflect the general condition of the body; at the same time, the past medical history of participants mainly relied on self-reporting by the participants, which may introduce bias. Finally, although a lot of data on neurologically healthy populations was collected, some predictors potentially related to the occurrence and development of aICAS were not included in this study (such as inflammatory predictors), and future studies need to continue collecting relevant data to comprehensively evaluate atherosclerosis.

This study also has certain strengths. First, this study is the first to evaluate a nomogram for the risk of aICAS occurrence, especially in neurologically healthy populations, which has certain clinical value. Second, this study comprehensively assesses the atherosclerosis of participants’ intracranial and extracranial arteries, using non-invasive MRA to assess intracranial arterial stenosis, which has high accuracy in diagnosing aICAS, and also evaluates the atherosclerosis of extracranial arteries, which is of clinical concern. Finally, this study used LASSO-Logistic regression analysis to screen variables independently associated with aICAS, and the nomogram performs well in terms of discrimination, calibration, and clinical application.

Conclusions

As far as we know, this work is the first to construct and validate a clinical risk prediction model for the occurrence of aICAS in neurologically healthy populations. Multivariate logistic regression showed that age, FBG, SBP, hypertension, and CAS were independently associated with aICAS. Therefore, the nomogram based on those indicators may be helpful in clinical risk assessment and decision-making.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study subjects for their participation and support of this study.

Author contributions

WL contributed to the study design, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. XL was involved in study design, data collection and processing, and wrote the manuscript. YL, JL1 and HZ contributed to the study design. QG contributed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. JL2 contributed to the data analysis. YL, JL1, WZ, LZ, YZ, and YH contributed to data collection and processing. HZ secured project funding. HZ, WL, JL2 and AW reviewed and edited the intellectual content. All authors gave final approval for this version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1311203).

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenbo Li and Xiaonan Liu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Greco, A. et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for Primary and Secondary Prevention of ischemic stroke: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.82, 1538–1557 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dearborn, J. L. et al. Intracranial atherosclerosis and dementia: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) Study. Neurology. 88, 1556–1563 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi, S. Asymptomatic intracranial artery stenosis—one less thing to worry about. JAMA Neurol.77 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wong, L. K. Global burden of intracranial atherosclerosis. Int. J. Stroke: Official J. Int. Stroke Soc.1, 158–159 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elder, T. A. et al. Future of Endovascular and Surgical treatments of atherosclerotic intracranial stenosis. Stroke. 55, 344–354 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoh, B. L. & Chimowitz, M. I. Focused update on intracranial atherosclerosis: introduction, highlights, and knowledge gaps. Stroke. 55, 305–310 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derdeyn, C. P. et al. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet (London England). 383, 333–341 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutierrez, J. et al. Determinants and outcomes of asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.78, 562–571 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, S. et al. The prevalence and prognosis of asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis in a community-based population: results based on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. J. Neurol.30, 3761–3771 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suri, M. F. et al. Prevalence of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis using high-resolution magnetic resonance angiography in the General Population: the atherosclerosis risk in communities Study. Stroke. 47, 1187–1193 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Planas-Ballvé, A. et al. The Barcelona-Asymptomatic Intracranial atherosclerosis study: subclinical intracranial atherosclerosis as predictor of long-term vascular events. Atherosclerosis. 282, 132–136 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurford, R. et al. Prognosis of asymptomatic intracranial stenosis in patients with transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. JAMA Neurol.77, 947–954 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutierrez, J., Turan, T. N., Hoh, B. L. & Chimowitz M. I. Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol.21, 355–368 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim, M. J. R., Tan, C. S., Gyanwali, B., Chen, C. & Hilal, S. The effect of intracranial stenosis on cognitive decline in a memory clinic cohort. Eur. J. Neurol.28, 1829–1839 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahas, N. E. et al. Cognitive impairment in asymptomatic cerebral arterial stenosis: a P300 study. Neurol. Sciences: Official J. Italian Neurol. Soc. Italian Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol.44, 601–609 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suri, M. F. K. et al. Cognitive impairment and intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in general population. Neurology. 90, e1240–e1247 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poorthuis, M. H. F. et al. Development and Internal Validation of a risk score to detect asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Eur. J. Vascular Endovascular Surgery: Official J. Eur. Soc. Vascular Surg.61, 365–373 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J.41, 111–188 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, B. et al. Association of remnant cholesterol and lipid parameters with new-onset carotid plaque in Chinese population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.9, 903390 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chait, A. et al. Remnants of the Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins, diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Diabetes. 69, 508–516 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knuuti, J. et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J.41, 407–477 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Touboul, P. J. et al. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004-2006-2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European stroke conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc. Dis.34, 290–296 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu, J. et al. National and Provincial-Level Prevalence and Risk factors of carotid atherosclerosis in Chinese adults. JAMA Netw. Open.7, e2351225 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamani, M. et al. Carotid plaque neovascularization detected with superb microvascular imaging Ultrasound without using contrast media. Stroke. 50, 3121–3127 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao, Z., Wang, H., Hou, Q., Zhou, Y. & Zhang, Y. Non-traditional lipid parameters as potential predictors of carotid plaque vulnerability and stenosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Neurol. Sciences: Official J. Italian Neurol. Soc. Italian Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol.44, 835–843 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuels, O. B., Joseph, G. J., Lynn, M. J., Smith, H. A. & Chimowitz M. I. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.21, 643–646 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chimowitz, M. I. et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med.352, 1305–1316 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mo, R., Shi, R., Hu, Y. & Hu, F. Nomogram-Based Prediction of the Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Retrospective Study. Journal of diabetes research 7261047 (2020). (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Wang, Y. L. et al. Fasting glucose and HbA(1c) levels as risk factors for the presence of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis. Annals Translational Med.7, 804 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ceriello, A. & Motz, E. Is oxidative stress the pathogenic mechanism underlying insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease? The common soil hypothesis revisited. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.24, 816–823 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan, C. et al. The stress hyperglycemia ratio is Associated with Hemorrhagic Transformation in patients with Acute ischemic stroke. Clin. Interv. Aging. 16, 431–442 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen, C. T. et al. Association between ambulatory systolic blood pressure during the day and asymptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 63, 61–67 (2014). (1979). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Turan, T. N. et al. Relationship between risk factor control and vascular events in the SAMMPRIS trial. Neurology. 88, 379–385 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi, Z. et al. Association of Hypertension with both occurrence and outcome of symptomatic patients with mild intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis: a prospective higher resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging: JMRI. 54, 76–88 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, Y. et al. Association of severity between carotid and intracranial artery atherosclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol.5, 843–849 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoshino, T. et al. Prevalence of systemic atherosclerosis burdens and overlapping stroke etiologies and their associations with Long-Term Vascular Prognosis in Stroke with Intracranial atherosclerotic disease. JAMA Neurol.75, 203–211 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, M. et al. Carotid atherosclerotic plaque predicts progression of intracranial artery atherosclerosis: a MR imaging-based community cohort study. Eur. J. Radiol.172, 111300 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao, H. et al. Intensive lipid-lowering therapy ameliorates asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis. Aging Disease. 10, 258–266 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.