INTRODUCTION

Diagnostic imaging is a key cornerstone in the diagnosis, staging, treatment planning, and therapeutic monitoring of cancer patients. Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) combines nuclear (PET) and anatomic (CT) imaging to provide functional and structural information about the patient’s body, making it particularly useful in the field of oncology.

The PET images are generated using radiopharmaceuticals, which are composed of a radiotracer attached to a targeting molecule. Radiotracers such as 18-Fluorine (18F) release a pair of gamma photons traveling in opposite directions that are simultaneously detected to generate a 3-dimensional image (1,2). Targeting molecules such as fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), allow the radiotracer to accumulate in specific sites of the body. As FDG is an analog of glucose, it accumulates in tissues with high metabolic rates, which includes physiological uptake within certain organs as well as inflammatory and neoplastic tissues (3) (Figure 1). Although there are a variety of radiopharmaceuticals that target different molecular characteristics of specific tissues, 18F-FDG is the most studied in veterinary medicine (4,5). An anatomical CT scan can be performed at the same time, and the images are summated to form PET/CT images. These scans can be evaluated qualitatively by visual inspection of areas with radiopharmaceutical uptake, and quantitatively by Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) measurements, which are a direct reflection of the degree of metabolic activity at the region of interest (3).

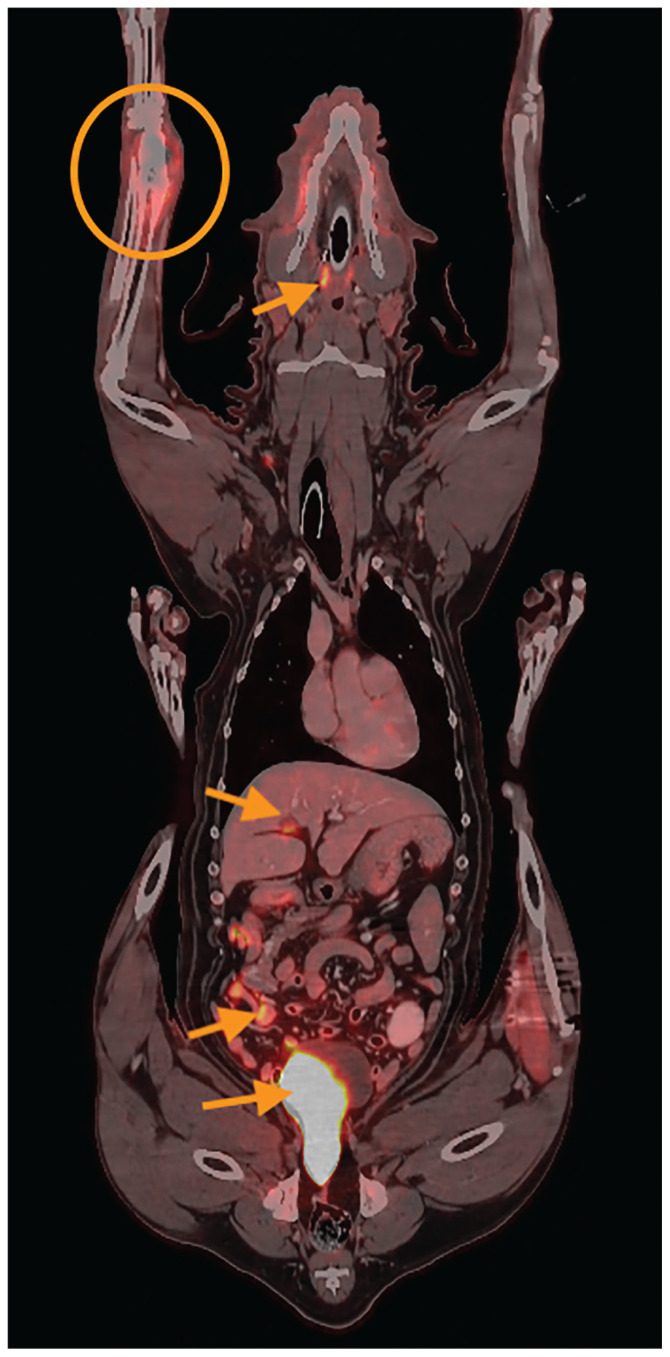

FIGURE 1.

Fused PET images and anatomical CT images (postcontrast soft tissue filter) in dorsal reconstruction. This patient has an osteosarcoma of the right distal radius (orange circle). Note the expansile appearance of this lesion with associated increased metabolic activity. Also note physiological FDG uptake in the tonsils, cystic duct, small intestines, and urinary bladder (orange arrows, cranial to caudal).

PET/CT IMAGING PROTOCOL

Imaging protocols of 18F-FDG PET/CT may vary slightly based on the institution. First, the patient must be fasted for a minimum of 6 to 12 h with free access to water (2,6,7). Blood glucose is measured before imaging, as high levels can compete with 18F-FDG for uptake into cells (2,7). Sedation or general anesthesia is required for the procedure (2). As 18F-FDG is eliminated by the urinary system, a urinary catheter is required to prevent radioactive contamination from urine leakage (2). The radiopharmaceutical is administered through a peripheral vein, followed by a 60- to 90-minute uptake period during which the patient must remain still to avoid active skeletal muscle uptake of FDG (2,8). A pre- and post-contrast anatomical CT scan and PET scan are then taken over a 60- to 90-minute period (Figure 2). After the imaging has been completed, the animal is placed in an isolation facility until radioactivity falls to institutionally approved levels. The short half-life of 18F (110 min) allows most animals to have their PET/CT completed in the morning for return home the same evening (2).

FIGURE 2.

Patient under sedation undergoing a PET/CT scan.

PET/CT UTILITY FOR DIFFERENT CANCER TYPES

Despite the limited research on PET/CT utility for veterinary cancer patients, its role in detection, staging, treatment planning, therapeutic monitoring and prognostication has been documented for various cancer types.

PET/CT was successful in detecting primary or metastatic neoplastic lesions that were otherwise undetectable on physical examination or by other imaging modalities in the following cancer types: lymphoma, mast cell tumors, hemangiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, mammary gland tumors, thyroid, intranasal, adrenocortical carcinoma, and pulmonary adenocarcinoma (2,3,9–19). A moderate positive correlation between FDG uptake, tumor size, and malignancy of mammary gland tumors has been established, although there was no association between the SUV and histological subtype or grade (20). Use of PET/CT may also provide justification to aspirate material from the bone marrow and palpably normal peripheral lymph nodes for lymphoma patients (10). Mast cell tumors were variably hypermetabolic, with small or low-grade lesions being poorly visualized or not visualized at all (2). Likewise, there is limited applicability of PET/CT in detecting insulinomas (15,21), as well as urological cancers such as transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) (22).

A decrease in FDG uptake in disease after stereotactic radiation therapy or systemic chemotherapy has been shown with PET/CT, in accordance with improved clinical signs in osteosarcoma and lymphoma patients (9,23). Lymphoma patients who failed to enter remission after chemotherapy were also consistently detected with this modality, making PET/CT a reliable tool for monitoring therapeutic response (3). In addition, valuable prognostic information can be provided for osteosarcoma patients, as a higher SUV of appendicular osteosarcoma has been correlated with a shorter mean survival time in dogs (24). As such, PET/CT may be suitable as a solitary imaging modality for appendicular osteosarcoma (13).

ADVANTAGES OF PET/CT

The PET/CT provides an in-depth evaluation of the molecular function and anatomic characteristics of the entire body (2). It can detect metabolic changes before anatomic change is evident, allowing the detection of cancer that is otherwise undetectable in physical examinations or other imaging modalities (2,3,7). Furthermore, it is the best tool available to depict maximal tumor volume, which has implications in determining surgical margins and directing radiation therapy (2). Use of PET/CT is also uniquely suited to detect recurrent or progressive disease (Figure 3), as well as to distinguish it from post-treatment fibrosis or necrosis, which is particularly helpful for diagnosing lesions that otherwise require invasive biopsies (8). Lastly, its noninvasive nature makes serial studies easy to obtain, with each procedure providing whole-body staging (1,2). These factors ultimately contribute to the ability of PET/CT to provide invaluable information for cancer patients.

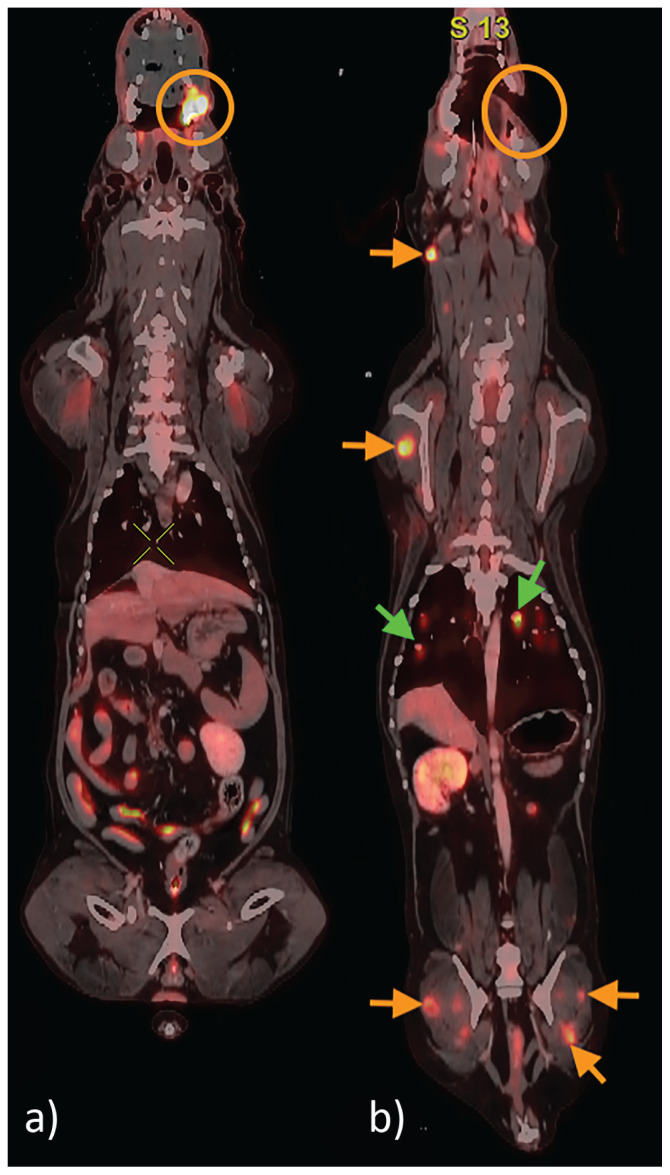

FIGURE 3.

Two PET/CT studies for a patient with left maxillary melanoma performed 6 mo apart. On the initial study (image a), a markedly hypermetabolic lesion is present in the left maxilla (orange circle). A partial maxillectomy is performed (orange circle, image b); however, at the time of recheck, there are multifocal progressive metastatic lesions in the muscles (orange arrows) and lungs (green arrows).

PITFALLS OF PET/CT

Although highly sensitive, PET/CT is limited in specificity, which predisposes image interpretation to false positives. This is the result of overlap in hypermetabolic activity between physiologic, inflammatory, and neoplastic lesions (2). Therefore, one of the most important aspects of interpreting PET/CT images is knowing the benign and physiologic variants and the normal distribution of various radiopharmaceuticals to reduce the chances of misinterpretation. On the same note, due to the minor differences in equipment and imaging protocol between institutions, standardized SUV reference values are difficult to establish, further complicating interpretation. Owing to the low specificity, histopathology is still the gold standard for obtaining a definitive diagnosis (2). When collecting tissue samples, it is important to keep in mind that biopsies or aspirates of lesions performed 1 to 2 d before PET/CT imaging cause local inflammation, resulting in hypermetabolic areas (2) that may confound interpretation.

False negatives may occur for tumors that are small, low-grade, necrotic, less vascular, or have large amounts of mucin (2,7). Whole-body PET/CT images also have a lower spatial resolution compared to regional CT or MRI due to the large field of view. Therefore, lesions less than 5 to 8 mm may be missed on visual or semiquantitative inspection of the images (2).

PATIENT CONSIDERATIONS

Radiation exposure to the patient and personnel is minimal with proper radiation safety practice. Owing to the strict guidelines for the use of radiopharmaceuticals, there is also no harmful level of exposure to the owners. The main concern for the animal is the extensive time under general anesthesia or sedation, and the patient should be healthy enough to undergo general anesthesia for 2 to 3 h for PET/CT imaging (2). This, in addition to the availability of a veterinary PET/CT scanner at only one site in Canada (the Western College of Veterinary Medicine), limit the suitability of this imaging modality for some veterinary patients (13).

Footnotes

Copyright is held by the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. Individuals interested in obtaining reproductions of this article or permission to use this material elsewhere should contact Permissions.

Questions

-

Which of the following regarding PET/CT scans is the most correct?

Small, low-grade, necrotic, less-vascular tumors have greater uptake of FDG, making them easier to distinguish.

It is a relatively invasive procedure, meaning serial studies are difficult to obtain.

It has low sensitivity and high specificity, meaning image interpretation is predisposed to false positives.

It is the best tool available to depict maximal tumor volume.

It is not suitable to detect recurring diseases and distinguish them from post-treatment fibrosis or necrosis.

Answer: D

-

PET/CT scans have limited specificity because?

Aspirates of lesions performed 1–2 d before PET/CT imaging cause reduced uptake of FDG in those areas.

Blood glucose often confounds interpretation by competing with FDG for uptake into cells.

PET/CT scans can detect metabolic changes before anatomical changes are evident.

Tumors that are small, low-grade, necrotic, less vascular, and have large amounts of mucin are difficult to detect.

There is a large overlap in the hypermetabolic activity between physiologic, inflammatory, and neoplastic lesions.

Answer: E

REFERENCES

- 1.Schnöckel U, Hermann S, Stegger L, et al. Small-animal PET: A promising, non-invasive tool in pre-clinical research. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2010;74:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randall EK. PET-computed tomography in veterinary medicine. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2016;46:515–533. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence J, Rohren E, Provenzale J. PET/CT today and tomorrow in veterinary cancer diagnosis and monitoring: Fundamentals, early results and future perspectives. Vet Comp Oncol. 2010;8:163–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2010.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanni C, Torigian DA. Applications of small animal imaging with PET, PET/CT, and PET/MR imaging. PET Clin. 2008;3:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao R, Lecomte R, Crawford ES. Small-animal PET: What is it, and why do we need it? J Nucl Med Technol. 2012;40:157–165. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.111.098632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattoon JS, Bryan JN. The future of imaging in veterinary oncology: Learning from human medicine. Vet J. 2013;197:541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leblanc AK, Miller AN, Galyon GD, et al. Preliminary evaluation of serial (18) FDG-PET/CT to assess response to toceranib phosphate therapy in canine cancer. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2012;53:348–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2012.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBlanc AK, Daniel GB. Advanced imaging for veterinary cancer patients. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2007;37:1059–1077. v–i. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBlanc AK, Jakoby BW, Townsend DW, Daniel GB. 18FDG-PET imaging in canine lymphoma and cutaneous mast cell tumor. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2009;50:215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2009.01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballegeer EA, Hollinger C, Kunst CM. Imaging diagnosis-multicentric lymphoma of granular lymphocytes imaged with FDG PET/CT in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2013;54:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2012.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slinkard PT, Randall EK, Griffin LR. Retrospective analysis of use of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) for detection of metastatic lymph nodes in dogs diagnosed with appendicular osteosarcoma. Can J Vet Res. 2021;85:131–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crooks C, Randall E, Griffin L. The use of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography as an effective method for staging in dogs with primary appendicular osteosarcoma. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2021;62:350–359. doi: 10.1111/vru.12959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brody A, Crooks JC, French JM, Lang LG, Randall EK, Griffin LR. Staging canine patients with appendicular osteosarcoma utilizing fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography compared to whole body computed tomography. Vet Comp Oncol. 2022;20:541–550. doi: 10.1111/vco.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo Y, Yun T, Chae Y, et al. Evaluation of a dog with inflammatory mammary carcinoma using 18F-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Vet Med Sci. 2022;8:1361–1365. doi: 10.1002/vms3.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walczak R, Kawalilak L, Griffin L. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography for staging of canine insulinoma: 3 cases (2019–2020) J Small Anim Pract. 2022;63:227–233. doi: 10.1111/jsap.13446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Kwon SY, Cena R, et al. CT and PET-CT of a dog with multiple pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76:615–620. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee D, Yun T, Koo Y, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT image findings of a dog with adrenocortical carcinoma. BMC Vet Res. 2022;18:15. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-03102-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen AE, McEvoy F, Engelholm SA, Law I, Kristensen AT. FDG PET/CT imaging in canine cancer patients. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2011;52:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borgatti A, Winter AL, Stuebner K, et al. Evaluation of 18-F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) as a staging and monitoring tool for dogs with stage-2 splenic hemangiosarcoma — A pilot study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sánchez D, Romero L, López S, et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT in canine mammary gland tumors. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:280. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi J, Keh S, Kim S, et al. Diagnostic imaging of malignant insulinoma in a dog. Korean J Vet Res. 2012;52:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song S-H, Park N-W, Eom K-D. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging features of renal cell carcinoma and pulmonary metastases in a dog. Can Vet J. 2014;55:466–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selmic LE, Griffin LR, Nolan MW, Custis J, Randall E, Withrow SJ. Use of PET/CT and stereotactic radiation therapy for the diagnosis and treatment of osteosarcoma metastases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2017;53:52–58. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin LR, Thamm DH, Brody A, Selmic LE. Prognostic value of fluorine18 flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:820–826. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]