Abstract

Cyclohexane is a volatile substance that has been utilized as a safe substitute of several organic solvents in diverse industrial processes, such as adhesives, paints, paint thinners, fingernail polish, lacquers, and rubber industry. A number of these commercial products are ordinarily used as inhaled drugs. However, it is not well known whether cyclohexane has noxious effects in the central nervous system. The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of cyclohexane inhalation on motor behavior, spatial memory, and reactive gliosis in the hippocampus of adult mice. We used a model that mimics recreational drug use in male Balb/C mice (P60), divided into two groups: controls and the cyclohexane group (exposed to 9,000 ppm of cyclohexane for 30 days). Both groups were then evaluated with a functional observational battery (FOB) and the Morris water maze (MWM). Furthermore, the relative expression of AP endonuclease 1 (APE1), and the number of astrocytes (GFAP+ cells) and microglia (Iba1+ cells) were quantified in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas. Our findings indicated that cyclohexane produced severe functional deficits during a recreational exposure as assessed by the FOB. The MWM did not show statistically significant changes in the acquisition and retention of spatial memory. Remarkably, a significant increase in the number of astrocytes and microglia cells, as well as in the cytoplasmic processes of these cells were observed in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas of cyclohexane-exposed mice. This cellular response was associated with an increase in the expression of APE1 in the same brain regions. In summary, cyclohexane exposure produces functional deficits that are associated with an important increase in the APE1 expression as well as the number of astrocytes and microglia cells and their cytoplasmic complexity in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the adult hippocampus.

Keywords: Degenerative disease, Hippocampus, Astrogliosis, Cyclohexane, Microglia, Inhaled drug

Introduction

Organic solvents are psychoactive substances with long-term negative or fatal consequences for individuals (Cruz 2011; Visser et al. 2011). These substances are inexpensive, legal, and easily available, which can be found in many commercial products, such as adhesives, correction fluid, lighter fuel, felt-tip markers, aerosols, paint products, and paint removers. (Bowen et al. 2006; Lubman et al. 2008; Ridenour et al. 2007). Organic solvents are highly volatile at room temperature and consumers can usually inhale them by nose and mouth (Cruz 2011; Bowen et al. 2006). Thus, the recreational consumption of organic solvents is associated with a number of medical illnesses and even death (Ridenour et al. 2007).

Volatile solvents produce a wide range of alterations in different body systems, but particularly affect the central and peripheral nervous system (Cruz 2011; Sabbath et al. 2014). Toluene, acetone, benzene, and cyclohexane are organic solvents found in abuse drugs (Flanagan and Ives 1994; Bespalov et al. 2003). Toluene, benzene, and other organic solvents produce evident behavioral alterations (Baydas et al. 2005; von Euler et al. 1993; Fifel et al. 2014) and hippocampal cell damage (Fukui et al. 1996; Gotohda et al. 2000; Korbo et al. 1996; Bale et al. 2005). Cyclohexane is used as an alternative to toluene and other solvents because it is considered as a less hazardous substance (Sikkema et al. 1994; Perbellini et al. 1981). Nevertheless, cyclohexane-exposed humans show a wide spectrum of biological effects, including lacrimation, hyperactivity, and sedation (Christoph et al. 2000; Malley et al. 2000; Bespalov et al. 2003; Lammers et al. 2009; Kreckmann et al. 2000). However, the possible consequences of cyclohexane inhalation on cognitive functions and brain cytoarchitecture have been scarcely studied. The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of inhaled cyclohexane on behavior, learning and spatial memory, and astroglial and microglial responses in the adult mouse hippocampus. Our findings suggested that cyclohexane has important deleterious effects on behavior and cytoarchitecture of the adult brain.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Housing

A total of 20 Balb/C male mice (P60) were assembled in two groups: the control group (non-exposed to cyclohexane) and the experimental group exposed to cyclohexane (99.5 % PRA grade, Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO). All animals were housed under standard biotery conditions in standard rearing cages (28 × 12 × 15 cm) maintained in an air-conditioned room (25 ± 1 °C). Water and food were delivered ad libitum. All experimental procedures described herein were approved and supervised by the Committee of Animal Care and Use of the University of Colima.

Cyclohexane Exposure

We used an animal model that mimics the human condition of solvent abuse episodes, which typically inhale very high concentrations (>6,000 ppm) for short periods of time (Bowen et al. 2006). All animals were placed in a polycarbonate chamber (38.5 cm × 27.5 cm) with four drug-delivery cylinders (11.5 cm) at every corner (Haas et al. 1999) at 25 °C. For 30 consecutive days, the cyclohexane group was exposed to 9,000 ppm of cyclohexane (Sigma Cat. No. 227048) for 30 min. All the experiments were performed at approximately 8:30 AM. Relative humidity and temperature were monitored and kept constant throughout the experiment. Following exposure, all the mice were transferred in a recovery cage for 30 min before being returned to their home cages. The control group was handled and placed under similar experimental conditions but without cyclohexane.

Functional Observational Battery (FOB)

Both the control and experimental groups were evaluated with the functional observational battery (FOB) (Boucard et al. 2010). FOB is a noninvasive procedure designed to detect gross functional deficits in rodents resulting from exposure to chemicals and to better quantify neurotoxic effects. The behavioral deficits observed with the FOB can predict some of the symptomatology that some drugs will have in humans (Moser 1990). Activity level, gait, and auditory function were evaluated during the last 3 min of drug exposure with the animals in the intoxication chamber. The parameters that required mouse handling were analyzed immediately after drug removal. Thus, we evaluated the response to two-hand manipulation, forelimb/hind limb grip strength, algesic (pain) response, lacrimation, and salivation. Forelimb/hind limb grip strength and algesic responses were assessed using a dichotomous scale: absence = 1 and presence = 2. To quantify the remaining parameters, we used a 3-point rating scale: severe = 1, mild = 2, and normal = 3.

Morris Water Maze (MWM)

To analyze functional impairments caused by cyclohexane inhalation on spatial learning and memory, all mice were evaluated with the MWM (Morris 1981, 1984).The experimental apparatus consisted of a circular water tank (120 cm wide and 40 cm high) surrounded by extra-maze cues. An escape platform (10 cm wide and 30 cm high) was placed in the water daily at 27 ± 1 °C temperature. The spatial learning protocol consisted of a 7-day acquisition period. Mice were allowed to swim freely for 90 s to locate the scape platform and kept onto the platform for 60 s. All animals that did not find the platform were guided and maintained on it for 60 s. After the task, all animals were then removed from the maze and placed in a pre-warmed cage. The memory retention test was performed 48-h after the memory acquisition task. Briefly, the escape platform was removed and mice were place into the water to quantify the time spent in the platform’s quadrant. Data were automatically captured by a video image motion analyzer of behavioral experiments (Ethovision, Version 3.1; Noldus Information Technology, USA).

Tissue Processing

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight) before sacrifice. Transcardial perfusion was done with 0.9 % NaCl solution at 37 °C followed by 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The brains were post-fixed overnight at 4 °C in the same fixative. Forty-micron thick coronal sections were cut with a vibratome. Serial sections were collected at 200-µm intervals between the coordinates +1.34 mm and −2.54 mm relative to Bregma (Paxinos and Franklin 2001). Tissue staining was performed as described below.

Immunohistochemistry

The samples were rinsed (10 min × 3) in 0.1 M buffer phosphate buffer saline (PBS) to rehydrate the tissue. To inactivate endogenous peroxidases, the brain sections were immersed in 3 % hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) dissolved in distilled water for 20 min and then washed three times with 0.1 M PBS. The sections were then blocked in 0.1 M PBS + 0.1 % Triton + 10 % goat serum for 1 h at room temperature in agitation. To label astrocytes, we used a rabbit IgG anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), dilution 1:500; (DakoCytomation, Cat. Z0334,), whereas to detect microglia cells we used or rabbit IgG anti Iba1, dilution 1:250 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Cat. GR117789-10). To analyze the expression of oxidative stress response proteins, we used a rabbit IgGanti-AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) dilution 1:1000 (Abcam Cat. AB175315). All primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C in blocking solution +0.1 % Triton-X. The following day, the tissue sections were rinsed 3 times with 0.1 M PBS and incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit lgG + lgM Biotin; AbDSerotec Cat. 401008) at dilution 1:400 and dissolved in blocking solution for 60 min at room temperature in darkness. The brain sections were then rinsed three times in 0.1 M PBS and incubated in darkness with the avidin–biotin complex (Vectastain ABC Kit, Elite Cat. No. PK-6100 Standard) for 45 min at room temperature. After three rinses in 0.1 M PBS, the sections were revealed for 5 min at room temperature using 0.03 % diaminobenzidine (DAB, Aldrich, No. 261890). The sections were then washed three times in 0.1 M PBS, mounted, and dehydrated using a series of ethanol solutions at crescent concentrations (70, 80, 90, and 95 %). The slides were immediately sealed with two drops of resin (Entellan; Merck, Cat. No. 1079600500) and air-dried before observation.

Quantification

To quantify the number of GFAP- or Iba-1 -expressing cells, ten 40-µm randomly selected sections at 200-µm intervals (n = 10 animals per group) were collected between the coordinate +1.34 mm to the coordinate −2.54 mm from Bregma. Under a 400× magnification (field area = 0.64 mm2), the CA1 and CA3 regions of hippocampus were studied. Only the cells found in the same focal plane were taken into account for quantification. The cytoplasmic transformation of astrocytes and microglia were evaluated with a stereological grid, which provides a suitable estimate of gliosis reactivity (Gonzalez-Perez et al. 2001). Briefly, the test grid consisted of 10 concentric circles with a separation between them of 10 μm. At least 320 astrocyte somas and 120 microglia somas per group were then placed in the central circle and the number of points at which cytoplasmic processes crossed the test grid lines was counted under 400× magnification. Only the GFAP+ or Iba1+ processes seen in the same plane of focus and in contact with the cell soma were considered for quantification. In all cases, the focal plane was set at the middle of the section using the computerized Z-position of the microscope. All pictures and histological analyses were done with a Zeiss Axio-Observer D1 microscope (Göttingen, Germany) and Axio-Vision 4.8.1 acquisition Software (Göttingen, Germany). A researcher blinded to group assignment did all the morphological analyses.

Densitometry (Relative Optical Density)

To determine changes in the expression of APE1, a densitometric analysis was performed to calculate relative optical density as described previously (Curtis et al. 2010). Briefly, at least five sections from each mouse (n = 4 animals per group) and ~290 images per group for the hippocampal CA1 region, and ~80 images per group for the hippocampal CA3 region were taken. All images were analyzed using the software ImageJ1.46r (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). The total intensity of staining per area was calculated by dividing the immunostaining intensity by the microscope field (area = 0.64 mm2) for each image and averaging all the images taken for each animal sample. To determine relative intensity per area, the average intensity per area determined for each animal sample was compared to the mean intensity per area of the control group. Thus, the expression level of APE1, the control group was set to one, whereas the cyclohexane group was plotted as the relative amount of APE1 expression above one. A blinded observer performed the densitometry measurement and calculations.

Statistical Analysis

Histological analyses are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR = Q3−Q1). Based on the assessment of skewness and kurtosis, the Mann–Whitney “U” test was used to determine differences between groups. In all cases, the statistical analyses were done with sample sizes based on the number of animals and the P < 0.05 value was selected to establish statistically significant differences.

Results

Functional Observational Battery

The FOB detects behavioral functional deficits in rodents as a result of exposure to chemicals (Boucard et al. 2010). To evaluate behavioral changes induced by cyclohexane exposure, we applied the FOB daily for 30 days. Remarkably, the cyclohexane group showed statistically significant differences in gait, activity function, sensory auditory function, response to two-hand manipulation, forelimb/hindlimb grip strength, and salivation and lacrimation levels as compared to the control group (Table 1). We did not find statistically significant differences in algesic response between groups (Table 1). All of these behaviors and signs were transient and remained less than 10 min after drug exposure. These findings indicate that cyclohexane inhalation causes an important functional deficit as that observed with other organic solvents.

Table 1.

FOB was used to detect behavioral functional deficits in rodents as a result of exposure to cyclohexane

| Parameters | Control median (IQ1–3) | Cyclohexane median (IQ1–3) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gait | 3 (2.9–3.0) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | 0.011 |

| Activity function | 2.9 (2.8–2.9) | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) | 0.014 |

| Sensory auditory function | 2.3 (2.2–2.5) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.014 |

| Response two-hand handling | 2.6 (2.6–2.9) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.014 |

| Forelimb/hindlimb grip strength | 1.9 (1.93–1.95) | 1.2 (1.26–1.29) | 0.009 |

| Salivation | 2.5 (2.3–2.6) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 0.014 |

| Lacrimation | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 0.014 |

| Algesic response | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) | 1.6 (1.6–1.8) | 0.707 |

Statistical analysis: Mann–Whitney “U” test P < 0.05. Data are expressed as median and 75–25 % interquartile range (IQR = Q3−Q1), n = 10 mice per group

Spatial Learning and Memory

To analyze whether a 30-day cyclohexane inhalation produced a cognitive deficit, we used the classic version of the MWM (Morris, 1984). This task also allows assessing gross physical, sensory, or motor impairments in rodents (Gulinello et al. 2009; Vorhees and Williams 2006). In this regard, the group cyclohexane showed more erratic navigation pattern and egocentric spatial strategies than control group (data not shown). As shown by the escape time, the cyclohexane group showed longer escape latencies (52.4 s, IQR = 38.2–63.5) throughout the experiment as compared to the control group (42.48 s, IQR = 35.5–56.1). Nonetheless, the statistical analysis did not show significant differences between groups (Fig. 1a). To determine a possible impairment in memory consolidation, we analyzed memory retention 48-h after memory acquisition phase. For this assay, we removed the escape platform from quadrant III and allowed animals to swim for 60 s in a single trail. We did not find differences in the time spent in the correct quadrant between the control group (15.7 s, IQR = 8.6–24.4) and the cyclohexane group (13.8 s, IQR = 11.4–17.2; P = 0.496, Mann–Whitney “U” test) (Fig. 1b). Taken together, our data suggest that cyclohexane did not impair memory acquisition and retention.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of spatial memory acquisition and retention in the Morris water maze (n = 10 mice per group). Cyclohexane exposure did not produce statistically significant differences either in the time course of the assay (a) or in the overall performance of the test (b). Memory retention was not affected by the effect of cyclohexane as shown by the time spent in the platform quadrant (c). The upper and lower limits of boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR = Q3−Q1) and the horizontal line into plot boxes represents the median value. The additional bars show the 90 % range of data and the circles symbolize extreme values (outliers). The learning acquisition curve (a) shows the mean ± standard error

Astrocytes

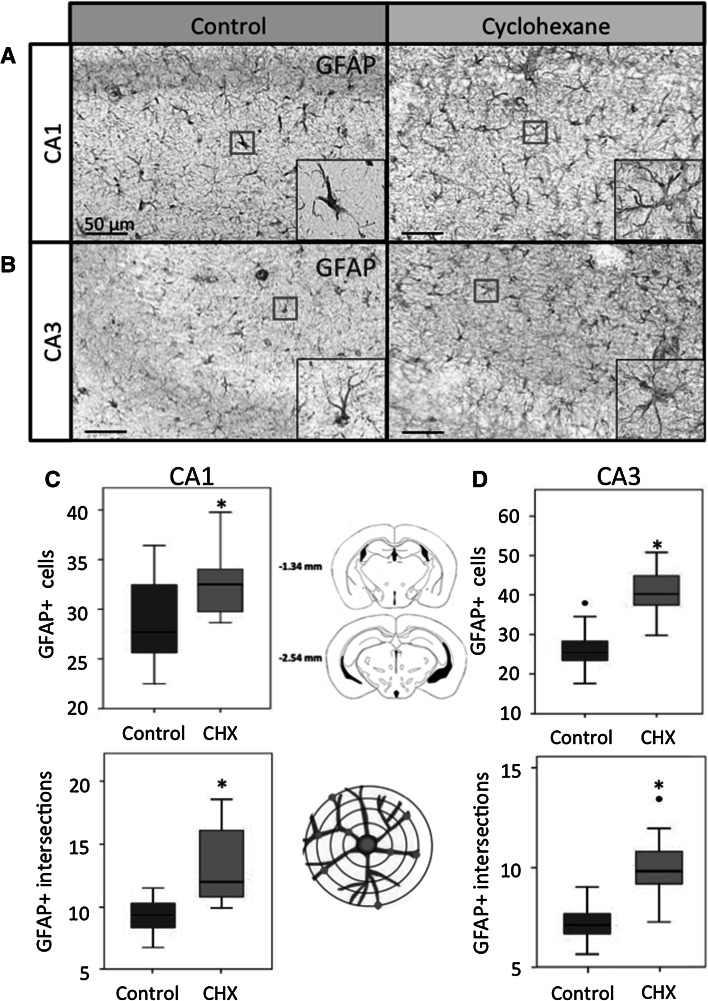

The over expression of GFAP is a good indicator of reactive gliosis and neural lesion in the central nervous system (O’Callaghan and Sriram 2005; Ramos-Remus et al. 2002). To investigate astrogliosis caused by cyclohexane inhalation, we quantified the number of GFAP+ cells in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas (Fig. 2a–d). In the CA1 area, the number of astrocytes in the cyclohexane group was higher (32.5 cells, IQR = 29.6–35.3; n = 10 mice) than in the control group (27.6 cells, IQR = 25.5–32.6; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 2c). In the CA3 area, cyclohexane inhalation also induced an increase in the number of astrocytes (40.2 cells, IQR = 37–45.4; n = 10 mice) with respect to the control group (25.3 cells, IQR = 22.9–29.8; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

GFAP-expressing astrocytes in CA1 in the control and the cyclohexane group. Cyclohexane exposure increased significantly, the number of astrocytes and the cytoplasmic complexity in the hippocampal CA1 (a, c) and CA3 (b, d) regions. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR = Q3−Q1); n = 10 mice per group. CHX cyclohexane. Circles outliers. Asterisks P < 0.05; Mann–Whitney “U” test. Bars 100 μm

In response to brain insults, reactive astrocytes increase their cytoplasmic complexity (Ramos-Remus et al. 2002). The number of GFAP+ processes was quantified with a stereological grid to determine the cytoplasmic transformation of astrocytes, (Gonzalez-Perez et al. 2001). In the CA1 area, we found statistically significant differences in the number of cytoplasmic intersections between the cyclohexane inhalation group (12 intersections, IQR = 10–16; n = 10 mice; P = 0.002, Mann–Whitney “U” test) and control group (9.3 intersections, IQR = 8.3–10.46; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 2c). In the CA3 region (Fig. 2d), the number of cytoplasmic intersections in the cyclohexane group (9.8 intersections, IQR = 8.9–11; n = 10 mice; P = 0.001, Mann–Whitney “U” test) was higher than in the control group (7.1 intersections, IQR = 6.5–7.7; n = 10 mice).These findings indicate that cyclohexane inhalation produces reactive gliosis in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas.

Microglia

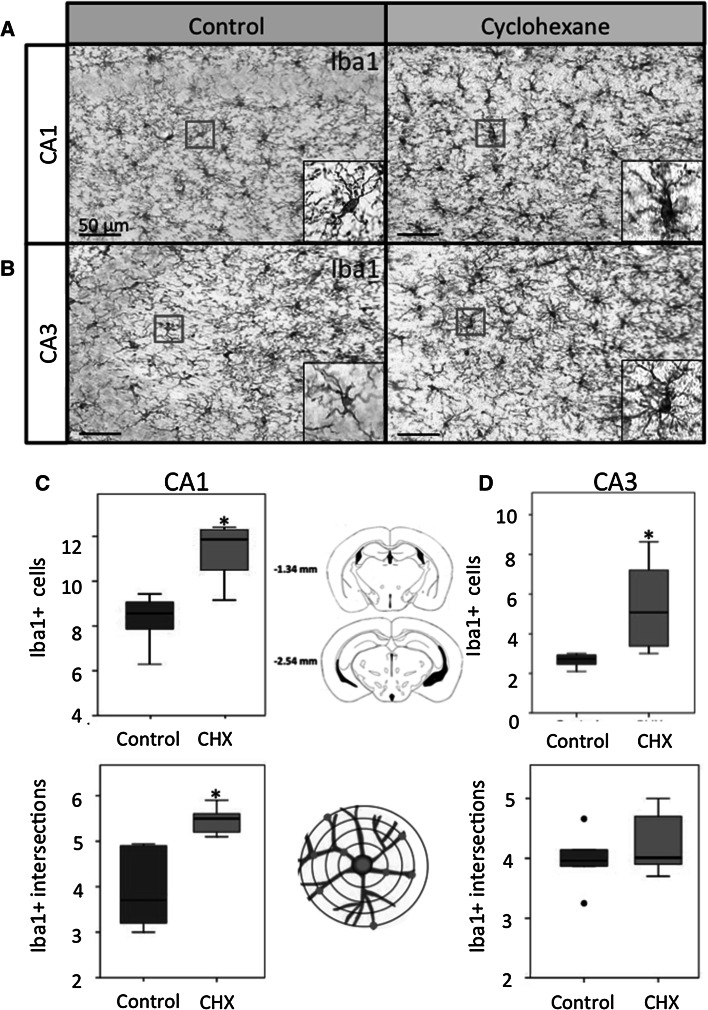

Microglial cells respond rapidly to a variety of alterations in the microenvironment of the brain and act as sensors for pathological events in the brain (Choi et al. 2007; Gonzalez-Castaneda et al. 2007). The number of Iba1+ (a marker of microglia) cells was quantified to investigate changes produced by cyclohexane inhalation at the CA1 and CA3 regions of hippocampus (Fig. 3a–d). In hippocampal CA1 region, the number of microglial cells were increased in the cyclohexane group (9.8 cells, IQR = 11.8–12.3; n = 10 mice) as compared to the control group (7 cells, IQR = 8.5–9.2; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 3c). In the CA3 region, the cyclohexane group also showed an increase (3.1 cells, IQR = 5–7.9; n = 10 mice) in the number of microglia cells as compared to the control group (2.2 cells, IQR = 2.7–2.9; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 3d).To determine the cytoplasmic transformation of microglia, we determine the number of cytoplasmic intersections with a stereological grid. In the CA1 region, we found statistically significant differences in the number of cytoplasmic intersections in the cyclohexane group (5.1 intersections, IQR = 5.5–5.7; n = 10 mice; P = 0.001, Mann–Whitney “U” test) as compared to controls (3.1 intersections, IQR = 3.7–4.9; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 3c). However, in the CA3 region, we did not find statistically significant differences between both groups: the cyclohexane group (3.8 intersections, IQR = 4–4.8; n = 10 mice; P = 0.658, Mann–Whitney “U” test) versus the control group (3.5 intersections, IQR = 3.9–4.4; n = 10 mice) (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Iba1-expressing microglia cells in CA1 in the control and the cyclohexane group. The number of microglia cells was significantly increased in the hippocampal CA1 (a, c) and CA3 (b, d) areas of cyclohexane-exposed animals as compared to controls. The cytoplasmic complexity of microglia cells was increased in the CA1 region of the cyclohexane group. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR = Q3−Q1); n = 10 mice per group. CHX = cyclohexane. Circles outliers. Asterisks P < 0.05; Mann–Whitney “U” test. Bars 50 μm

Oxidative Stress Analysis

The accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is considered as responsible for neurotoxicity of solvents (van Thriel et al. 2007; Dick 2006). To determine whether cyclohexane induced the expression of oxidative stress response proteins, we analyzed the expression of AP endonuclease 1 in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions (n = 4 mice per group). We found that the relative expression of APE1 in the group exposed to cyclohexane was significantly increased in the CA1 region (1.46, IQR = 1.3–1.6; P = 0.04) and in the CA3 hippocampus (1.85, IQR = 1.7–2.1; P = 0.03) as compared to the control group (Fig. 4a, b). These data indicate that cyclohexane promotes a significant oxidative stress response in hippocampus.

Fig. 4.

Expression of APE1 in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions. a APE1 immunohistochemistry in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas of the cyclohexane group and controls. Cyclohexane exposure induced significant increase in the relative expression of APE1 in both the hippocampal CA1 (P = 0.04; Mann–Whitney “U” test) and CA3 (P = 0.036; Mann–Whitney “U” test) regions as compared to controls. The APE1 expression of controls is equal to one (dashed line). Bar 200 μm

Discussion

Cyclohexane has been proposed as a safe substitute for toluene or xylene in a number of industrial processes and commercial products. However, the effects of cyclohexane inhalation in the CNS are not totally studied, yet. In this study, we analyzed the effects of inhaled cyclohexane on behavior, memory acquisition/retention, reactive gliosis, and cellular response to oxidative stress. Our findings indicated that cyclohexane exposure produced naso-oral hypersecretion and motor hyperactivity followed by lethargy and sedation. These behaviors were reversible and minimal residual deficit was observed upon drug removal. These findings closely resemble those seen in drug users of organic solvents (Kurtzman et al. 2001). Similar biphasic effects have also been reported with other solvents such as toluene and trichloroethane that increase motor activity, disrupt psychomotor performance, and provoke sedation (Gmaz et al. 2012; Bowen and Balster 1998; Warren et al. 1998; Evans and Balster 1991). Besides reactive astrocytes and microglia cells, cyclohexane induced overexpression of APE1, an oxidative stress response enzyme. Taken together, this evidence indicates that cyclohexane inhalation produce a similar intoxication as that observed with other solvents.

To evaluate possible alterations on spatial learning and memory in the group exposed to cyclohexane for 30 days, we used the Morris water maze (Morris 1981, 1984). As shown by the escape latencies and time spent in the platform quadrant, cyclohexane exposure did not produce changes in memory tasks. In contrast, other organic solvents such as toluene, trichloroethane, or benzene impair the acquisition phase and spatial memory retention (Baydas et al. 2005; von Euler et al. 1993; Fifel et al. 2014). These differences may indicate that cyclohexane could have less functional implications on spatial memory as compared to other organic solvents. However, the experimental design of our study does not allow discarding other types of cyclohexane-induced cognitive impairments, such as working memory, social memory, operant, or classical conditioning.

To evaluate astrogliosis induced by the cyclohexane inhalation, the number of astrocytes (GFAP+ cells) and their intermediate filaments in the CA1 and CA3 areas were analyzed. Our findings showed a statistically significant increase in the number and in the cytoplasmic complexity of hippocampal astrocytes. An increase in the number of astrocytes had only been reported upon exposure to toluene, trichloroethane, and dichloromethane (Gotohda et al. 2000; Rosengren et al. 1985, 1986). Astroglial response can be triggered by physical, biological, or chemical insults and is characterized by an increase in GFAP+ intermediate filaments, cellular hypertrophy, and astrocytic proliferation (Nowicka et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2010; Burda and Sofroniew 2014; Anderson et al. 2014; Ransom and Ransom 2012). Taken together, our data indicate that cyclohexane induces similar pathological changes in the central nervous system as those described with other organic solvents.

Microglia cells are extremely sensitive to homeostatic disruptions in the CNS and moderate brain insults can generate a robust microglial response (Gonzalez-Perez et al. 2012). In this study, we found a significant increase in the number and cytoplasmic complexity of microglia cells in hippocampal CA1. In CA3 area, the number of microglia cells was increased, but we did not observe significant changes in the cellular morphology as compared with control. A similar microglial response was observed after exposure to 1-bromopropane, an aliphatic organic solvent that increases oxidative stress in neurons, which increases the expression of CD11b/c microglial cells in cerebellum (Subramanian et al. 2012). Thus, we hypothesize that cyclohexane may have a similar mechanism to promote microglial activation and proliferation after neural insults (Kettenmann et al. 2011). Cyclohexane is a strongly lipophilic molecule (Hissink et al. 2009) that can easily diffuse throughout the neural tissue. Therefore, we cannot reject the possibility that cyclohexane is affecting other brain regions involved in motor control, balance, or cognitive functions. However, further studies are needed to clarify this event.

APE1, a multifunctional enzyme that plays a central role in the cellular response to oxidative stress, which includes the redox regulation of transcriptional factors and DNA repair (Gros et al. 2004). AP endonuclease is up-regulated in presence of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress-associated insults (van Thriel et al. 2007; Dick 2006). Our data indicated that APE1 expression was increased by cyclohexane exposure, which suggest that oxidative stress mediators are involved in the glial response in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas. However, the molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration underlying cyclohexane exposure remains to be elucidated.

In summary, cyclohexane inhalation for 30 days in young adult mice produces functional deficit during exposure without evident changes on learning and spatial memory. Remarkably, cyclohexane induces APE1 overexpression, reactive gliosis, and microglial response in hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions, which can indicate an ongoing brain injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from ConsejoNacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT; INFR2014-224359)andPrograma de Mejoramiento al Profesorado (PROMEP; 103.5/12/4857).

Conflict of interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Anderson MA, Ao Y, Sofroniew MV (2014) Heterogeneity of reactive astrocytes. Neurosci Lett 565:23–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale AS, Tu Y, Carpenter-Hyland EP, Chandler LJ, Woodward JJ (2005) Alterations in glutamatergic and gabaergic ion channel activity in hippocampal neurons following exposure to the abused inhalant toluene. Neuroscience 130(1):197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydas G, Ozveren F, Akdemir I, Tuzcu M, Yasar A (2005) Learning and memory deficits in rats induced by chronic thinner exposure are reversed by melatonin. J Pineal Res 39(1):50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bespalov A, Sukhotina I, Medvedev I, Malyshkin A, Belozertseva I, Balster R, Zvartau E (2003) Facilitation of electrical brain self-stimulation behavior by abused solvents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 75(1):199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucard A, Betat AM, Forster R, Simonnard A, Froget G (2010) Evaluation of neurotoxicity potential in rats: the functional observational battery. Current Protoc Pharmacol/Editorial Board, Enna SJ (editor-in-chief) et al Chapter 10:Unit 10 12 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bowen SE, Balster RL (1998) A direct comparison of inhalant effects on locomotor activity and schedule-controlled behavior in mice. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 6(3):235–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Batis JC, Paez-Martinez N, Cruz SL (2006) The last decade of solvent research in animal models of abuse: mechanistic and behavioral studies. Neurotoxicol Teratol 28(6):636–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JE, Sofroniew MV (2014) Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron 81(2):229–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Lee CH, Hwang IK, Won MH, Seong JK, Yoon YS, Lee HS, Lee IS (2007) Age-related changes in ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 immunoreactivity and protein level in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region. J Vet Med Sci 69(11):1131–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph GR, Kelly DP, Krivanek N (2000) Acute inhalation exposure to cyclohexane and schedule-controlled operant performance in rats: comparison to d-amphetamine and chlorpromazine. Drug Chem Toxicol 23(4):539–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz SL (2011) The latest evidence in the neuroscience of solvent misuse: an article written for service providers. Subst Use Misuse 46(Suppl 1):62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis CD, Thorngren DL, Nardulli AM (2010) Immunohistochemical analysis of oxidative stress and DNA repair proteins in normal mammary and breast cancer tissues. BMC Cancer 10:9. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick FD (2006) Solvent neurotoxicity. Occup Environ Med 63(3):221–226, 179. doi:10.1136/oem.2005.022400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans EB, Balster RL (1991) CNS depressant effects of volatile organic solvents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 15(2):233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fifel K, Bennis M, Ba-M’hamed S (2014) Effects of acute and chronic inhalation of paint thinner in mice: behavioral and immunohistochemical study. Metab Brain Dis 29(2):471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan RJ, Ives RJ (1994) Volatile substance abuse. Bull Narc 46(2):49–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K, Utsumi H, Tamada Y, Nakajima T, Ibata Y (1996) Selective increase in astrocytic elements in the rat dentate gyrus after chronic toluene exposure studied by GFAP immunocytochemistry and electron microscopy. Neurosci Lett 203(2):85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmaz JM, Yang L, Ahrari A, McKay BE (2012) Binge inhalation of toluene vapor produces dissociable motor and cognitive dysfunction in water maze tasks. Behav Pharmacol 23(7):669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Castellanos-Alvarado EA, Flores-Marquez MR, Gonzalez-Perez O, Luquin S, Garcia-Estrada J, Ramos-Remus C (2007) Deflazacort induced stronger immunosuppression than expected. Clin Rheumatol 26(6):935–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Ramos-Remus C, Garcia-Estrada J, Luquin S (2001) Prednisone induces anxiety and glial cerebral changes in rats. J Rheumatol 28(11):2529–2534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Gutierrez-Fernandez F, Lopez-Virgen V, Collas-Aguilar J, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Garcia-Verdugo JM (2012) Immunological regulation of neurogenic niches in the adult brain. Neuroscience 226:270–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotohda T, Tokunaga I, Kubo S, Morita K, Kitamura O, Eguchi A (2000) Effect of toluene inhalation on astrocytes and neurotrophic factor in rat brain. Forensic Sci Int 113(1–3):233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros L, Ishchenko AA, Ide H, Elder RH, Saparbaev MK (2004) The major human AP endonuclease (Ape1) is involved in the nucleotide incision repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Res 32(1):73–81. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulinello M, Gertner M, Mendoza G, Schoenfeld BP, Oddo S, LaFerla F, Choi CH, McBride SM, Faber DS (2009) Validation of a 2-day water maze protocol in mice. Behav Brain Res 196(2):220–227. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas CN, Rose JB, Gerba CP. (1999). Quantitative microbial risk assessment. Wiley, New York.

- Hissink AM, Kulig BM, Kruse J, Freidig AP, Verwei M, Muijser H, Lammers JH, McKee RH, Owen DE, Sweeney LM, Salmon F (2009) Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of cyclohexane as a tool for integrating animal and human test data. Int J Toxicol 28(6):498–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A (2011) Physiology of microglia. Physiol Rev 91(2):461–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbo L, Ladefoged O, Lam HR, Ostergaard G, West MJ, Arlien-Soborg P (1996) Neuronal loss in hippocampus in rats exposed to toluene. Neurotoxicology 17(2):359–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreckmann KH, Baldwin JK, Roberts LG, Staab RJ, Kelly DP, Saik JE (2000) Inhalation developmental toxicity and reproduction studies with cyclohexane. Drug Chem Toxicol 23(4):555–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman TL, Otsuka KN, Wahl RA (2001) Inhalant abuse by adolescents. J Adolesc Health 28(3):170–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers JH, Emmen HH, Muijser H, Hoogendijk EM, McKee RH, Owen DE, Kulig BM (2009) Neurobehavioral effects of cyclohexane in rat and human. Int J Toxicol 28(6):488–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Yucel M, Lawrence AJ (2008) Inhalant abuse among adolescents: neurobiological considerations. Br J Pharmacol 154(2):316–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malley LA, Bamberger JR, Stadler JC, Elliott GS, Hansen JF, Chiu T, Grabowski JS, Pavkov KL (2000) Subchronic toxicity of cyclohexane in rats and mice by inhalation exposure. Drug Chem Toxicol 23(4):513–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R (1981) Spatial localisation does not depend on the presence of local cues. Learn Motiv 12:239–260 [Google Scholar]

- Morris R (1984) Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods 11(1):47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser VC (1990) Approaches for assessing the validity of a functional observational battery. Neurotoxicol Teratol 12(5):483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka D, Rogozinska K, Aleksy M, Witte OW, Skangiel-Kramska J (2008) Spatiotemporal dynamics of astroglial and microglial responses after photothrombotic stroke in the rat brain. Acta Neurobiol Exp 68(2):155–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan JP, Sriram K (2005) Glial fibrillary acidic protein and related glial proteins as biomarkers of neurotoxicity. Expert Opin Drug Saf 4(3):433–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin K (2001) The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 2nd edn. Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- Perbellini L, Brugnone F, Silvestri R, Gaffuri E (1981) Measurement of the urinary metabolites of N-hexane, cyclohexane and their isomers by gas chromatography. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 48(1):99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Remus C, Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Gonzalez-Perez O, Luquin S, Garcia-Estrada J (2002) Prednisone induces cognitive dysfunction, neuronal degeneration, and reactive gliosis in rats. J Investig Med 50(6):458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom BR, Ransom CB (2012) Astrocytes: multitalented stars of the central nervous system. Methods Mol Biology (Clifton NJ) 814:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour TA, Bray BC, Cottler LB (2007) Reliability of use, abuse, and dependence of four types of inhalants in adolescents and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 91(1):40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren LE, Aurell A, Kjellstrand P, Haglid KG (1985) Astrogliosis in the cerebral cortex of gerbils after long-term exposure to 1,1,1-trichloroethane. Scand J Work Environ Health 11(6):447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren LE, Kjellstrand P, Aurell A, Haglid KG (1986) Irreversible effects of dichloromethane on the brain after long term exposure: a quantitative study of DNA and the glial cell marker proteins S-100 and GFA. Br J Ind Med 43(5):291–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbath EL, Gutierrez LA, Okechukwu CA, Singh-Manoux A, Amieva H, Goldberg M, Zins M, Berr C (2014) Time may not fully attenuate solvent-associated cognitive deficits in highly exposed workers. Neurology 82(19):1716–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema J, de Bont JA, Poolman B (1994) Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem 269(11):8022–8028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian K, Mohideen SS, Suzumura A, Asai N, Murakumo Y, Takahashi M, Jin S, Zhang L, Huang Z, Ichihara S, Kitoh J, Ichihara G (2012) Exposure to 1-bromopropane induces microglial changes and oxidative stress in the rat cerebellum. Toxicology 302(1):18–24. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Thriel C, Kiesswetter E, Schaper M, Blaszkewicz M, Golka K, Juran S, Kleinbeck S, Seeber A (2007) From neurotoxic to chemosensory effects: new insights on acute solvent neurotoxicity exemplified by acute effects of 2-ethylhexanol. Neurotoxicology 28(2):347–355. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser I, Wekking EM, de Boer AG, de Joode EA, van Hout MS, van Dorsselaer S, Ruhe HG, Huijser J, van der Laan G, van Dijk FJ, Schene AH (2011) Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic solvent induced encephalopathy (CSE). Neurotoxicology 32(6):916–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Euler G, Ogren SO, Li XM, Fuxe K, Gustafsson JA (1993) Persistent effects of subchronic toluene exposure on spatial learning and memory, dopamine-mediated locomotor activity and dopamine D2 agonist binding in the rat. Toxicology 77(3):223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees CV, Williams MT (2006) Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc 1(2):848–858. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren DA, Reigle TG, Muralidhara S, Dallas CE (1998) Schedule-controlled operant behavior of rats during 1,1,1-trichloroethane inhalation: relationship to blood and brain solvent concentrations. Neurotoxicol Teratol 20(2):143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Hu X, Qian L, O’Callaghan JP, Hong JS (2010) Astrogliosis in CNS pathologies: is there a role for microglia? Mol Neurobiol 41(2–3):232–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]