Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are present in serum and have the potential to serve as disease biomarkers. As such, it is important to explore the clinical value of miRNAs in serum as biomarkers for ischemic stroke (IS) and cast light on the pathogenesis of IS. In this study, we screened differentially expressed serum miRNAs from IS and normal people by miRNA microarray analysis, and validated the expression of candidate miRNAs using quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assays. Furthermore, we performed gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses to disclose functional enrichment of genes predicted to be regulated by the differentially expressed miRNAs. Notably, our results revealed that 115 miRNAs were differentially expressed in IS, among which miR-32-3p, miR-106-5p, and miR-532-5p were first found to be associated with IS. In addition, GO and KEGG pathway analyses showed that genes predicted to be regulated by differentially expressed miRNAs were significantly enriched in several related biological process and pathways, including axon guidance, glioma, MAPK signaling, mammalian target of rapamycin signaling, and ErbB-signaling pathway. In conclusion, we identified the changed expression pattern of miRNAs in IS. Serum miR-32-3p, miR-106-5p, miR-1246, and miR-532-5p may serve as potential diagnostic biomarkers for IS. Our results also demonstrate a novel role for miRNAs in the pathogenesis of IS.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10571-014-0139-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Microarray, Ischemic stroke, Biomarker

Introduction

Stroke is a major cerebrovascular disease threatening human health and life with high morbidity, disability, and mortality. Recent studies have been reported that stroke has been a leading cause of death in China (Tsai et al. 2013). Stroke can be classified into ischemic stroke (IS) and hemorrhagic stroke (HS). Approximately, 80 % of the stroke cases are ischemic in origin (Goldstein et al. 2001). Stroke risk increases with age (Faber et al. 2011), and multiple factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, are believed to be associated with a high risk of stroke (Prugger et al. 2013).

At present, the diagnosis of stroke depends on clinical examination and neuro-imaging techniques. There are no reliable circulating biomarkers for acute IS risk prediction, diagnosis, and outcome prediction. Stroke clinical diagnosis with biomarkers should be fast, cost effective, specific, and sensitive. As for identification of the biomarkers of IS, many studies have been focused on single selected proteins because of their known relationship to IS pathophysiology. Among these include markers of brain tissue damage, inflammation, and coagulation/thrombosis, such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and D-dimer (Lynch et al. 2004; Di Napoli et al. 2005; Fon et al. 1994; Montaner et al. 2008; Alvarez-Perez et al. 2011; Lambertsen et al. 2012). Given that heterogeneity of IS, the successful translation to a protein biomarker useful in clinical practice has been proven difficult. In recent years, RNA biomarkers have brought more attention in the diagnosis and assessment of IS (Jickling and Sharp 2011). However, research on these biomarkers is flourishing, and they are not yet used in clinical settings.

The serum microRNAs (miRNAs) in serum have been reported to be stable, reproducible, and consistent among individuals (Chen et al. 2008). MiRNAs are noncoding RNAs of ~22 nucleotides and modulate protein expression by binding to complementary or partially complementary target sites in the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of messenger RNA (mRNA) (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001) (see Fig. 1). MiRNAs play a significant role in various cellular processes (i.e., development, differentiation, apoptosis, and oncogenesis) (Bushati and Cohen 2007). MiRNAs are abundantly expressed in the nervous system, implicating their significant contribution to neural development and functioning (Shao et al. 2010). It is widely believed that circulating miRNAs can be associated with the brain miRNA (Liu et al. 2010), and miRNAs released from damaged cells or circulating cells lead to increased plasma miRNAs expressions (Mayr et al. 2013). Therefore, serum miRNAs could partly represent the miRNAs released from damaged nerve tissue (Jin et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.

MiRNA biogenesis and mode of function. miRNAs genes are transcribed in the nucleus by the RNA polymerase II as a pri-miRNA, followed by processing by the RNase III enzyme Drosha and its cofactor DiGeorge syndrome critical gene 8 (DGCR8) into pre-miRNAs. After nuclear export, they are cleaved by the RNase III enzyme Dicer into mature miRNAs consisting of ~22 nucleotides. Finally, a single-stranded miRNA is loaded onto the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC), where the seed sequence is located at positions 2–8 from the 5′ end of the miRNA binding to the target mRNA thus inhibiting gene transcription

Studies on miRNAs have opened up the opportunity of developing a new class of molecular markers for diagnosis of IS (Sepramaniam et al. 2014; Tan et al. 2009). In the event of a stroke, up-regulation or down-regulation of miRNAs may be observed in the brain and serum (Yuan et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2009; Siegel et al. 2011; Tan et al. 2013; Zeng et al. 2011). A class of miRNAs has been identified to be differentially expressed in animal models of IS and young patients (Dharap et al. 2009; Jeyaseelan et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2010; Lusardi et al. 2010; Tan et al. 2009). The involvement of miRNA in regulating the pathogenesis associated with middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in SD rats was first reported by Jeyaseelan et al., which demonstrated that rno-miR-19b, -290, and -292-5p were found to be highly expressed, whereas rno-miR-103 and rno-miR-107 were found to be poorly expressed (2008). Moreover, they also carried out miRNA profiling from peripheral blood in young stroke patients (Tan et al. 2009), in which 8 miRNAs (hsa-let-7f, miR-126, -1259, -142-3p, -15b, -186, -519e, -768-5p) were found to be poorly expressed across the three subtypes of stroke (large artery stroke, small artery stroke, and cardio embolic stroke). In another study, Long et al. identified that circulating miR-126 was markedly down-regulated in IS until 24 weeks (2013). Laterza et al. demonstrated that circulating miR-124-3p is a biomarker of brain injury (2009). However, studies have shown that miR-124 is clearly reduced in the ischemic brain after stroke (Doeppner et al. 2013; Gilje et al. 2014). Recent studies have indicated that miR-145, miR-424, and miR-223 may serve as biomarker of IS (Gan et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2013). In summary, variety of miRNAs biomarker has been reported in IS. However, due to the complexity of the pathology, the knowledge on the association of circulating miRNAs with IS is still lacking. There has been limited studies regarding the roles of circulating miRNAs as potential biomarkers in Chinese middle-old-aged acute IS patients. Additional study is required to better understand miRNAs in acute IS, and their regulation of genes and pathways was involved in IS.

In this work, we aimed to profile serum miRNAs profile from middle-old-aged patients with acute IS and investigate their diagnostic potential in IS. Furthermore, we analyzed the biological function of these differentially expressed miRNAs, in the perspective of a more comprehensive understanding toward IS-associated circulating miRNAs.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the ethic committee of Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine. All patients and controls provided written informed consents for the collection of samples and subsequent analysis.

Patients, Healthy Controls, and Samples

All participants (aged >45) were enrolled from the acute IS patients (within 24 h after stroke onset) and healthy volunteers at Jiangsu Province hospital of TCM from March 2012 to January 2013. Diagnosis was based on the International Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision) as previously described (Zhang et al. 2011a). Imaging studies (MRI/CT) were reviewed by experienced neuroradiologists to confirm the diagnosis and identify the stroke subtypes. Exclusion criteria included other types of stroke (transient ischemic attack, subarachnoid hemorrhage, brain tumors, and cerebrovascular malformation); severe systemic diseases, i.e., pulmonary fibrosis, endocrine, and metabolic diseases (except type 2 diabetes); inflammatory and autoimmune diseases; and serious chronic diseases, for example, hepatic cirrhosis and renal failure. Healthy volunteers met the same exclusion criteria as the patient cases. The demographics and clinical features of the patients in the validation set are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

General clinical characteristics of IS patients and healthy control

| Characteristics | IS (n = 117) | Control (n = 82) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68 ± 1.5 | 67 ± 1.2 | >0.05 |

| Gender (M/F) | 31/22 | 29/21 | >0.05 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.29 ± 0.03 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | >0.05 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.43 ± 0.06 | 2.39 ± 0.08 | >0.05 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.52 ± 0.12 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | >0.05 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.98 ± 0.16 | 4.67 ± 0.07 | >0.05 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.85 ± 0.09 | 4.73 ± 0.06 | >0.05 |

M male, F female, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG total triglyceride, TC total cholesterol

Blood samples from IS patients were collected within 24 h after stroke symptoms onset. 5 ml of whole blood was collected into a separate gel coagulation-promoting vacuum tube (BD Vacutainer, Plymouth, UK). Blood samples were fractionated by centrifugation at 3,000g for 15 min at 4° C. The serum layer was then aliquoted and stored at −80° C for subsequent experiments.

Laboratory Determinations

The serum levels of total triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and glucose were measured by clinical laboratory (Olympus AU2700, Japan) using the manufacturer’s reagents and standards.

Study Design

The study design was used to profile serum miRNAs in IS. There are two types of IS: thrombotic and embolic. Furthermore, the important risk factors for IS include high blood pressure, diabetes, heart diseases, and high cholesterol. During the initial screening stage, we divided the serum samples into five groups (10 serum samples were pooled to form a group). Group A1: A1 denotes thrombotic stroke and hypertension. Group A14: A 14 denotes thrombotic stroke, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Group B2: B2 denotes embolic stroke and heart disease. Group B12: B12 denotes embolic stroke, hypertension, and denotes heart disease. Group 0: 0 denotes healthy control. These serum samples were subjected to miRCURY™ LNA Array (v.18.0) for miRNAs profiling.

MicroRNA Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was purified using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Gmbh, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was determined using ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), and the integrity of RNA samples was verified using denaturing gel electrophoresis (15 % polyacrylamide). The samples were further labeled with the miRCURY™ Hy3™/Hy5™ Power labeling kit and hybridized on the miRCURY™ LNA Array (v.18.0) (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark). The slides were scanned with the Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner. The scanned images were imported into GenePix Pro 6.0 software (Axon) for grid alignment and data extraction. Replicated miRNAs were averaged, and miRNAs with intensity not less than 30 in all samples were chosen for normalization factor calculation. Expressed data were normalized using the median normalization. Differential expression analysis of the miRNAs was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction (p < 0.05) as described in Partek® Genomics Suite™ 6.6 Software (Partek Inc, St Louis, USA). We performed a fold change filtering between the two samples from the experiment. The fold change threshold that we used to screen up or down-regulated miRNAs is 2. Microarray data have been deposited in NCBI gene expression omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE60319.

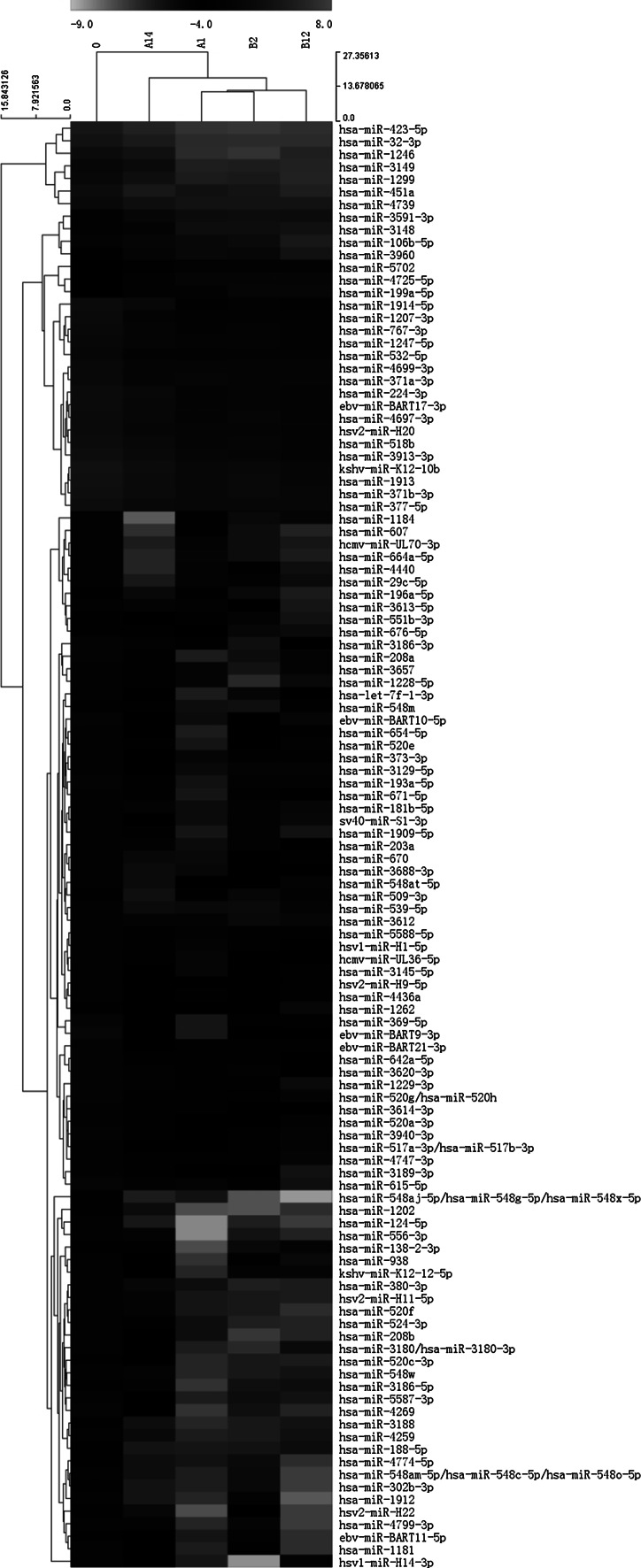

Differentially expressed miRNAs between IS and control were selected for cluster analysis with Cluster software (version 3.0, http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm). The TreeView tool (http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net/) was used to show the generated results. The cluster analysis categorized samples and miRNAs into groups based on their expression levels, which allowed us to predict the relationships between the miRNAs and the samples.

Bioinformatics Target Gene Prediction, Gene Ontology, and Pathway Analysis

The sequences of differentially expressed miRNAs were obtained from the Sanger miRNA Registry (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/software/Rfam/mirna). We used the miRBase target prediction database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm), TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), and miRanda (http://www.microRNA.org) for the prediction of miRNAs-targeted genes, which were defined as genes predicted to be targeted by all the three algorithms.

The Gene Ontology project provides a controlled vocabulary to describe gene and gene product attributed in any organism (http://www.geneontology.org). The ontology covers three domains: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. Fisher’s exact test was used to find if there was significant overlap between the differential expression (DE) list and the GO annotation list, rather than that would be expected by chance. The p value denotes the significance of GO terms enrichment in the DE genes. The lower the p value, the more significant the GO Term (p value <0.05 is recommended).

Similarly, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) was used to find out the significant pathway of the predicted target genes. Likewise, the p value (EASE-score, Fisher-p value, or hyper geometric-p value) denotes the significance of the Pathway correlated to the conditions. The threshold of significance was defined by p value and FDR.

Selection of Candidate miRNAs

The criteria for further investigation of the most promising candidates were as follows: (1) higher fold change of differentially expressed miRNAs in IS and control, (2) higher expression levels and signal intensity of differential miRNAs in IS and control, and (3) well-known miRNAs that have been reported by literatures. We used these criteria to generate a list of 13 miRNAs: miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-423-5p, miR-451a, miR-1246, miR-1299, miR-3149, miR-4739, miR-224-3p, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, miR-532-5p, and miR-1913.

Validation of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

The serum miRNAs were extracted using the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, serum proteins were denatured, and 1 μl of 5 nM non-human synthetic miRNA (syn-cel-lin-39) was added into 50 μl of each serum sample as an internal control for the normalization of the real-time PCR results (Kroh et al. 2010). The expressions of mature miRNAs were analyzed using TaqMan based qRT-PCR methods according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The total RNA (2 μl) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using AMV reverse transcriptase (Takara Dalian, Liaoning, China) and the stem-loop RT primer (Applied Biosystems). Each RT reaction contained 1× stem-loop RT-specific primer, 1× reaction buffer, 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 3.33 units per Multiscribe RT enzyme, and 0.25 U per RNase inhibitor. The 20 μl reactions were incubated for 30 min at 16 °C, 30 min at 42 °C, and 5 min at 85 °C. The real-time PCR reactions were performed in duplicate in scaled-down reaction volumes (20 μl) with an ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System under the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The data were analyzed using the SDS Software version 2.4 (Applied Biosystems). The cycle threshold (Ct) values were determined using the fixed threshold settings. Any miRNA with a Ct value greater than 36 was considered undetectable. The results were expressed as Ct values and normalized on the calculated median Ct of each sample (ΔCt). Relative expression was calculated using the comparative Ct method (2−ΔΔCt).

A total of 24 IS patients and 22 control subjects were enrolled in the training set. MiRNAs with a Ct value lower than 35 and a p value <0.05 were selected for further analysis. To verify the accuracy and specificity of these miRNAs and to determine the number of miRNAs to be used as the IS signature, we further examined the following six miRNAs (miR-32-3p, miR-106-5p, miR-1246, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, and miR-532-5p), in the validation set by qRT-PCR. All the miRNAs were sampled from 53 IS patients and 50 controls. MiRNAs with a mean fold change ≥2 or ≤0.05 and p value <0.05 were considered to be significantly differentially expressed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Results for variables that were normally distributed are displayed as the mean ± SEM. For categorical variables, the Chi-Square test was used. Independent samples t test was used for 2-group comparisons. p value <0.05 was considered to be significantly different.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

117 patients with acute IS and 82 healthy subjects were recruited from March 2012 to January 2013. In our study, all patients suffered from IS, participants’ age, gender, total triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, and Glucose were recorded. No significant difference between IS groups and control group was observed (p > 0.05). Baseline characteristics for recruited people are presented in Table 1.

MiRNA Microarray Analysis and Screening

For the miRNA microarray analysis, the miRNA expression profile of 3,100 miRNAs was determined in the serum from the IS patients and the control group using Exqion miRCURY™ LNA Array (v.18.0) technology. Furthermore, after microarray scanning and normalization, we analyzed the differentially expressed miRNAs between the IS and the normal control serum samples by performing unsupervised clustering that was blinded to the clinical evaluation. The dendrogram generated by the cluster analysis showed a clear separation of the IS samples from the control samples (Fig. 2). In our study, 115 human mature miRNAs were identified to be differentially expressed in IS serum compared to those control group, including 14 up-regulated miRNAs and 101 down-regulated miRNAs. The up-regulated miRNAs are shown in Table 2. The criteria for further investigation of the most promising candidates were as follows: (1) higher fold change of differentially expressed miRNAs in IS and control, threshold: miRNAs have change ≥fourfold; (2) higher expression levels and signal intensity of differentially expressed miRNAs in IS and control, threshold: the quantification Ct values of miRNAs <32 and foreground intensity of miRNA probe signal-background intensity of miRNA probe signal in IS and control >100; and (3) well-known miRNAs that have been reported by literatures. Based on these criteria, 13 miRNAs were further subjected for validation by bioinformatic assay and detected by qRT-PCR. These miRNAs included miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-423-5p, miR-451a, miR-1246, miR-1299, miR-3149, miR-4739, miR-224-3p, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, miR-532-5p, and miR-1913.

Fig. 2.

Hierarchical cluster and tree-view analysis of differentially expressed miRNAs in healthy people and IS serum (A1, A14, B2, B12). Group A1: A1 denotes thrombotic stroke and hypertension. Group A14: A 14 denotes thrombotic stroke, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Group B2: B2 denotes embolic stroke and heart disease. Group B12: B12 denotes embolic stroke, hypertension, and denotes heart disease. Group 0: 0 denotes healthy control. Above the color gradient represents the relative expression level (green color denotes low expression and red color denotes high expression) (Color fiure online)

Table 2.

Fold change of up-regulated miRNAs in serum from IS and healthy control

| Name | A1 versus control | A14 versus control | B2 versus control | B12 versus control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-423-5p | 13.58083844 | 3.402944497 | 17.3879983 | 9.058359651 |

| hsa-miR-1299 | 18.92825112 | 3.992329723 | 14.48596169 | 35.90226834 |

| hsa-miR-32-3p | 12.66718343 | 2.979117045 | 13.53832256 | 12.22182197 |

| hsa-miR-106b-5p | 3.43416225 | 2.170025468 | 5.325557937 | 36.19619666 |

| hsa-miR-451a | 2.427128897 | 5.81691075 | 3.518220032 | 11.4205019 |

| hsa-miR-3149 | 31.72782791 | 2.21220171 | 27.31768225 | 38.85100856 |

| hsa-miR-1246 | 31.06999949 | 2.15625252 | 60.83851618 | 11.8488132 |

| hsa-miR-4739 | 5.137185121 | 2.766733563 | 5.031602268 | 4.795541707 |

| hsa-miR-4725-5p | 6.340807175 | 2.327649208 | 6.990291262 | 5.410714286 |

| hsa-miR-3591-3p | 13.93592973 | 4.796506098 | 17.05439553 | 13.78069961 |

| hsa-miR-5702 | 3.860986547 | 2.378806334 | 2.927184466 | 2.933035714 |

| hsa-miR-3148 | 18.62666742 | 2.007755285 | 18.11724223 | 29.38223327 |

| hsa-miR-3960 | 8.656950673 | 4.061510353 | 6.653259362 | 47.00892857 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | 4.603049327 | 3.112399513 | 12.26796117 | 12.49392857 |

Group A1: A1 denotes thrombotic stroke and hypertension. Group A14: A14 denotes thrombotic stroke, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Group B2: B2 denotes embolic stroke and heart disease. Group B12: B12 denotes embolic stroke, hypertension, and heart disease. Group 0: 0 denotes healthy control group

GO and Pathway Analysis Revealed the Roles of These miRNAs in IS

In order to gain insights into the functions of these miRNAs, miRNAs-targeted genes were predicted using miRBase, TargetScan, and miRanda, and GO and KEGG pathway analysis were applied to their target pool. In order to obtain a more reliable result, we excluded the targets found by only one prediction programs. As a result, we found that these miRNAs could regulate a large number of genes (Fig. 3). GO enrichment analysis indicated that 921 GOs were significantly enriched by the down-regulated genes, and 340 GOs were significantly enriched by the up-regulated genes. The top 10 GOs enriched by genes targeted by the up-regulated miRNAs included regulation of cellular process, cellular biosynthetic process, and gene expression (Fig. 4a). In contrast, top 10 GOs enriched by genes targeted by down-regulated miRNAs included heart development, negative regulation of cellular metabolic process, and negative regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 3.

Functional annotation analysis of predicted targets of differentially expressed miRNAs. a Venn diagram of predicted targets of up-regulated miRNAs with three prediction programs: miRBase, TargetScan, and miRanda. b Venn diagram of predicted targets of down-regulated miRNAs

Fig. 4.

Top 10 GO categories based on biological processes for target genes of dysregulated miRNAs. a Target genes of the up-regulated miRNAs were involved in the regulation of cellular process, cellular biosynthetic process, and gene expression. b Target genes of the down-regulated miRNAs were involved in heart development, negative regulation of cellular metabolic process, and negative regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process. The vertical axis is GO categories, and the horizontal axis is the −lg p values of GO categories

A variety of pathways enriched by genes targeted by differentially expressed miRNAs was identified via KEGG pathway analysis. 61 pathways were enriched genes targeted by up-regulated miRNAs, the top 10 of which included axon guidance, glioma, MAPK signaling, mTOR signaling, and ErbB signaling (Fig. 5). In addition, 24 pathways were enriched by genes targeted by down-regulated miRNAs, the top 10 of which included chemokine-signaling pathway, ErbB signaling, axon guidance, and focal adhesion (Fig. 5). Many of these signaling pathways, such as MAPK pathways and mTOR signaling, have been demonstrated to participate in the pathogenesis of IS. This represents novel evidences for the modulatory roles of miRNAs in IS. In addition, target genes involved in both the enriched GO categories and KEGG pathways were assembled in a miRNA-gene network, in which the interaction between miRNAs and their corresponding target genes was displayed (Figs. 6, 7). The miRNAs that had crucial roles in regulating the related biological processes and pathways were identified. Among the dysregulated miRNAs, miR-106b-5p, miR-3148, and miR-423-5p were the top three key miRNAs in the network (Figs. 6, 7).

Fig. 5.

Top 10 KEGG pathways based on miRNA-targeted genes. a Target genes of up-regulated miRNAs were involved in axon guidance, MAPK signaling, mTOR signaling, ErbB signaling, and Glioma. b Target genes of down-regulated miRNAs were related to chemokine-signaling pathway, ErbB signaling, axon guidance, and Focal adhesion. The vertical axis is KEGG categories, and the horizontal axis is the −lg p value of KEGG pathways

Fig. 6.

MiRNA-GO-network analysis. Target genes of the dysregulated miRNAs are assembled in the network according to their miRNA status. The circles represent genes that were involved in the enriched GO categories. The squares represent the dysregulated miRNAs (a and b show up-regulated and down-regulated miRNAs, respectively)

Fig. 7.

MiRNA-gene-network analysis. Target genes of the dysregulated miRNAs were assembled in the network according to their miRNA status. The circles represent genes that were involved in both the enriched GO categories and KEGG pathways. The squares represent the dysregulated miRNAs (a and b show up-regulated and down-regulated miRNAs, respectively). Green lines mark the interactions between miRNAs and corresponding target genes (Color figure online)

Validation of Microarray Data Using qRT-PCR

To validate the microarray data, we performed qRT-PCR of the above selected miRNAs. In the training set, the expression levels of 13 miRNAs in the serum from the control (n = 22) and IS (n = 24) were determined by qRT-PCR. We found that expression of 8 miRNAs (miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-423-5p, miR-451a, miR-1246, miR-1299, miR-3149, and miR-4739) significantly increased (fold change: 1.69, 2.6, 1.64, 1.82, 2.02, 1.98, 1.96, 1.83, respectively) in the serum of IS patients compared with the control subjects (Fig. 8a). On the other hand, the expression of 5 miRNAs (miR-224-3p, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, miR-532-5p, and miR-1913) significantly decreased (fold change 1.63, 1.77, 1.49, 1.65, 1.59, respectively) in the serum of IS patients (Fig. 8b). The altered expression of these miRNAs was identical to microarray data. Next, we further selected these miRNAs with high fold change and high basal expression level (miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, miR-532-5p, and miR-1246) to validate by qRT-PCR in a larger sample which consisted of 53 IS patients and 50 control people. Compared with the control group, the expression of miR-32-3p, miR-106-5p, and miR-1246 in IS serum was significantly increased (fold change 1.57, 1.74, 1.96, respectively), and the expression of miR-532-5p in IS serum was significantly lower (fold change: 1.63) (Fig. 9), similar to the previous results. However, the expression of miR-518b and miR-377-5p did not change significantly. These results indicated the diagnostic potential of such miRNAs in IS.

Fig. 8.

Quantitative real-time PCR analyses of the expressions of miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-423-5p, miR-451a, miR-1246, miR-1299, miR-3149, miR-4739 (a), miR-224-3p, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, miR-532-5p, and miR-1913 (b) in serum from control group (n = 22) and IS (n = 24). The data are presented as relative expression following normalization. Data represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to control

Fig. 9.

Quantitative real-time PCR analyses of the expressions of miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-377-5p, miR-518b, miR-532-5p, and miR-1246 in serum from control group (n = 50) and IS (n = 53). The data are presented as relative expression following normalization. Data represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to control

Discussion

In the present study, we profiled the expression of circulating miRNAs in the acute IS for the first onset of symptom. 115 miRNAs with altered expression in IS serum were identified by miRNAs screening technique. Furthermore, according to functional assay, miR106b-5p, miR-532-5p, and miR-1246 might play a vital role in the pathogenesis of IS.

Recently, various studies have investigated the profile of miRNAs in IS patients and middle cerebral artery occlusion animal models by microarray and RT-qPCR technique (Dharap et al. 2009; Jeyaseelan et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2010; Lusardi et al. 2010; Tan et al. 2009). Similarly, altered expression of miR-1246 has also been detected in blood samples of IS, as reported in previous studies (Tan et al. 2009). Nevertheless, the profiles of miRNAs from different laboratories varied widely due to the difference in miRNA array platforms, specimen category, sample sizes, and other clinical characteristics. For the first time, we identified three additional miRNAs (miR-32-3p, miR-106b-5p, and miR-532-5p) in serum that are differentially expressed in ischemia.

It is reported that some miRNAs play fundamental roles in neuronal development, dendritic growth and morphogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis (Cheng et al. 2009; Fiore et al. 2008; Saugstad 2010; Doeppner et al. 2013; Harraz et al. 2012; Serafini et al. 2012). In this respect, some differentially expressed miRNAs in the present study may be involved in the processes of brain damage or neuroprotection after stroke, including axon guidance, apoptotic response to ischemia/reperfusion injury, or neuron protection from ischemic death. Therefore, we hypothesized that these differentially expressed miRNAs may induce the onset of IS.

The mechanisms that trigger ischemic brain damage might involve cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, autophagy, and underlying-signaling pathway (Moskowitz et al. 2010). Recent studies have demonstrated that the activation of NF-κB and p38MAPK is linked to the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia (Cui et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010). Other research reports have shown that mTOR pathway, as a novel neuroprotectants for IS, plays a pivotal role in protecting against stroke (Xiong et al. 2014; Fletcher et al. 2013). Our findings indicated that the target genes of these differentially expressed miRNAs might participate in the mTOR, MAPK, and ErB signal pathways. Zhang et al. (2011b) demonstrated that p53 regulatory pathway was potentially important for tumorigenesis, in which miR-1246 was involved. Moreover, Annemarie et al. elucidated that miR-106 could promote the hematopoietic cells expansion through interference with MAPK-signaling pathway (Meenhuis et al. 2011). Hence, precise mechanisms and cellular pathways involved in stroke require further investigation.

In our study, serum miRNAs levels were changed in IS compared to normal controls. Although serum miRNAs could be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of some diseases, the sources and the mechanisms of their secretion from which cell types into serum remain unclear. Chen et al. found that serum miRNAs were derived from blood cells and other tissues that were affected by the disease (2008). Therefore, whether the expression levels of serum miRNAs in IS also changed in brain tissue will need to be confirmed.

Our studies have identified four miRNAs with altered expression in the acute IS. Further studies are warranted to examine the expression of these miRNAs in the sub-acute phase, rehabilitation phase, and recurrence IS. Another question that needs to be addressed is the determination of the targets of miRNAs. Through bio-informatic analysis, we found that stroke-related genes vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGFA), myeloid cell leukemia-1(Mcl-1), and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) might be the targets of miR-106b (Zeng et al. 2014; Ouyang et al. 2014; Ouyang and Giffard 2014), so miR-106b may affect multiple pathways such as apoptosis, oxidation, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis in IS. The search of specific miRNA sequence polymorphisms will be determinant in future studies in the effort to discover the association with IS pathogenesis (Serafini et al. 2012; Jeon et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2014). Such investigations not only are beneficial to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the occurrence and development of stroke but also provide theoretical evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of stroke. Further investigation is needed to identify the miRNAs that are involved in regulation of stroke-related cellular and molecular networks, which could provide insight into new therapeutic avenues.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81171659 and 81403136).

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- Alvarez-Perez FJ, Castelo-Branco M, Alvarez-Sabin J (2011) Usefulness of measurement of fibrinogen, D-dimer, D-dimer/fibrinogen ratio, C reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate to assess the pathophysiology and mechanism of ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82(9):986–992. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.230870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushati N, Cohen SM (2007) microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23:175–205. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, Guo J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Guo X, Li Q, Li X, Wang W, Zhang Y, Wang J, Jiang X, Xiang Y, Xu C, Zheng P, Zhang J, Li R, Zhang H, Shang X, Gong T, Ning G, Wang J, Zen K, Zhang J, Zhang CY (2008) Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res 18(10):997–1006. doi:10.1038/cr.2008.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LC, Pastrana E, Tavazoie M, Doetsch F (2009) miR-124 regulates adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone stem cell niche. Nat Neurosci 12(4):399–408. doi:10.1038/nn.2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Zhang X, Yang R, Liu L, Wang L, Li M, Du W (2010) Baicalein is neuroprotective in rat MCAO model: role of 12/15-lipoxygenase, mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytosolic phospholipase A2. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 96(4):469–475. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2010.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharap A, Bowen K, Place R, Li LC, Vemuganti R (2009) Transient focal ischemia induces extensive temporal changes in rat cerebral microRNAome. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metab 29(4):675–687. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2008.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli M, Schwaninger M, Cappelli R, Ceccarelli E, Di Gianfilippo G, Donati C, Emsley HC, Forconi S, Hopkins SJ, Masotti L, Muir KW, Paciucci A, Papa F, Roncacci S, Sander D, Sander K, Smith CJ, Stefanini A, Weber D (2005) Evaluation of C-reactive protein measurement for assessing the risk and prognosis in ischemic stroke: a statement for health care professionals from the CRP Pooling Project members. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 36(6):1316–1329. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000165929.78756.ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doeppner TR, Doehring M, Bretschneider E, Zechariah A, Kaltwasser B, Muller B, Koch JC, Bahr M, Hermann DM, Michel U (2013) MicroRNA-124 protects against focal cerebral ischemia via mechanisms involving Usp14-dependent REST degradation. Acta Neuropathol 126(2):251–265. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1142-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber JE, Zhang H, Lassance-Soares RM, Prabhakar P, Najafi AH, Burnett MS, Epstein SE (2011) Aging causes collateral rarefaction and increased severity of ischemic injury in multiple tissues. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31(8):1748–1756. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore R, Siegel G, Schratt G (2008) MicroRNA function in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1779(8):471–478. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher L, Evans TM, Watts LT, Jimenez DF, Digicaylioglu M (2013) Rapamycin treatment improves neuron viability in an in vitro model of stroke. PLoS ONE 8(7):e68281. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fon EA, Mackey A, Cote R, Wolfson C, McIlraith DM, Leclerc J, Bourque F (1994) Hemostatic markers in acute transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 25(2):282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan CS, Wang CW, Tan KS (2012) Circulatory microRNA-145 expression is increased in cerebral ischemia. Genet Mol Res 11(1):147–152. doi:10.4238/2012.January.27.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilje P, Gidlof O, Rundgren M, Cronberg T, Al-Mashat M, Olde B, Friberg H, Erlinge D (2014) The brain-enriched microRNA miR-124 in plasma predicts neurological outcome after cardiac arrest. Crit Care 18(2):R40. doi:10.1186/cc13753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LB, Adams R, Becker K, Furberg CD, Gorelick PB, Hademenos G, Hill M, Howard G, Howard VJ, Jacobs B, Levine SR, Mosca L, Sacco RL, Sherman DG, Wolf PA, del Zoppo GJ (2001) Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 32(1):280–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz MM, Eacker SM, Wang X, Dawson TM, Dawson VL (2012) MicroRNA-223 is neuroprotective by targeting glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(46):18962–18967. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121288109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon YJ, Kim OJ, Kim SY, Oh SH, Oh D, Kim OJ, Shin BS, Kim NK (2013) Association of the miR-146a, miR-149, miR-196a2, and miR-499 polymorphisms with ischemic stroke and silent brain infarction risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33(2):420–430. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan K, Lim KY, Armugam A (2008) MicroRNA expression in the blood and brain of rats subjected to transient focal ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 39(3):959–966. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jickling GC, Sharp FR (2011) Blood biomarkers of ischemic strokem. Neurotherapeutics. J Am Soc Exp NeuroTher 8(3):349–360. doi:10.1007/s13311-011-0050-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin XF, Wu N, Wang L, Li J (2013) Circulating microRNAs: a novel class of potential biomarkers for diagnosing and prognosing central nervous system diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 33(5):601–613. doi:10.1007/s10571-013-9940-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroh EM, Parkin RK, Mitchell PS, Tewari M (2010) Analysis of circulating microRNA biomarkers in plasma and serum using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). Methods 50(4):298–301. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T (2001) Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294(5543):853–858. doi:10.1126/science.1064921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen KL, Biber K, Finsen B (2012) Inflammatory cytokines in experimental and human stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32(9):1677–1698. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2012.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laterza OF, Lim L, Garrett-Engele PW, Vlasakova K, Muniappa N, Tanaka WK, Johnson JM, Sina JF, Fare TL, Sistare FD, Glaab WE (2009) Plasma MicroRNAs as sensitive and specific biomarkers of tissue injury. Clin Chem 55(11):1977–1983. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2009.131797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Yoon HJ, Jeon D, Kang KM, Park KH, Bae EK, Kim M, Lee SK, Roh JK (2010) MicroRNAs induced during ischemic preconditioning. Stroke. J Cereb Cir 41(8):1646–1651. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Li Z, Li J, Siegel C, Yuan R, McCullough LD (2009) Sex differences in caspase activation after stroke. Stroke. J. Cereb Circ 40(5):1842–1848. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DZ, Tian Y, Ander BP, Xu H, Stamova BS, Zhan X, Turner RJ, Jickling G, Sharp FR (2010) Brain and blood microRNA expression profiling of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and kainate seizures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30(1):92–101. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long G, Wang F, Li H, Yin Z, Sandip C, Lou Y, Wang Y, Chen C, Wang DW (2013) Circulating miR-30a, miR-126 and let-7b as biomarker for ischemic stroke in humans. BMC Neurol 13:178. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-13-178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi TA, Farr CD, Faulkner CL, Pignataro G, Yang T, Lan J, Simon RP, Saugstad JA (2010) Ischemic preconditioning regulates expression of microRNAs and a predicted target, MeCP2, in mouse cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30(4):744–756. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2009.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JR, Blessing R, White WD, Grocott HP, Newman MF, Laskowitz DT (2004) Novel diagnostic test for acute stroke. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 35(1):57–63. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000105927.62344.4C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr M, Zampetaki A, Kiechl S (2013) MicroRNA biomarkers for failing hearts? Eur Heart J 34(36):2782–2783. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenhuis A, van Veelen PA, de Looper H, van Boxtel N, van den Berge IJ, Sun SM, Taskesen E, Stern P, de Ru AH, van Adrichem AJ, Demmers J, Jongen-Lavrencic M, Lowenberg B, Touw IP, Sharp PA, Erkeland SJ (2011) MiR-17/20/93/106 promote hematopoietic cell expansion by targeting sequestosome 1-regulated pathways in mice. Blood 118(4):916–925. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-336487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner J, Perea-Gainza M, Delgado P, Ribo M, Chacon P, Rosell A, Quintana M, Palacios ME, Molina CA, Alvarez-Sabin J (2008) Etiologic diagnosis of ischemic stroke subtypes with plasma biomarkers. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 39(8):2280–2287. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, Iadecola C (2010) The science of stroke: mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron 67(2):181–198. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YB, Giffard RG (2014) microRNAs affect BCL-2 family proteins in the setting of cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Int 77C:2–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YB, Xu L, Yue S, Liu S, Giffard RG (2014) Neuroprotection by astrocytes in brain ischemia: importance of microRNAs. Neurosci Lett 565:53–58. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prugger C, Luc G, Haas B, Morange PE, Ferrieres J, Amouyel P, Kee F, Ducimetiere P, Empana JP, Group PS (2013) Multiple biomarkers for the prediction of ischemic stroke: the PRIME study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33(3):659–666. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad JA (2010) MicroRNAs as effectors of brain function with roles in ischemia and injury, neuroprotection, and neurodegeneration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30(9):1564–1576. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2010.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepramaniam S, Tan JR, Tan KS, DeSilva DA, Tavintharan S, Woon FP, Wang CW, Yong FL, Karolina DS, Kaur P, Liu FJ, Lim KY, Armugam A, Jeyaseelan K (2014) Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers of acute stroke. Int J Mol Sci 15(1):1418–1432. doi:10.3390/ijms15011418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G, Pompili M, Innamorati M, Giordano G, Montebovi F, Sher L, Dwivedi Y, Girardi P (2012) The role of microRNAs in synaptic plasticity, major affective disorders and suicidal behavior. Neurosci Res 73(3):179–190. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao NY, Hu HY, Yan Z, Xu Y, Hu H, Menzel C, Li N, Chen W, Khaitovich P (2010) Comprehensive survey of human brain microRNA by deep sequencing. BMC Genom 11:409. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel C, Li J, Liu F, Benashski SE, McCullough LD (2011) miR-23a regulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) contributes to sex differences in the response to cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(28):11662–11667. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102635108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KS, Armugam A, Sepramaniam S, Lim KY, Setyowati KD, Wang CW, Jeyaseelan K (2009) Expression profile of microRNAs in young stroke patients. PLoS ONE 4(11):e7689. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JR, Tan KS, Koo YX, Yong FL, Wang CW, Armugam A, Jeyaseelan K (2013) Blood microRNAs in Low or No risk ischemic stroke patients. Int J Mol Sci 14(1):2072–2084. doi:10.3390/ijms14012072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CF, Thomas B, Sudlow CL (2013) Epidemiology of stroke and its subtypes in Chinese vs white populations: a systematic review. Neurology 81(3):264–272. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfde3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang X, Liu L, Cui L, Yang R, Li M, Du W (2010) Tanshinone II A down-regulates HMGB1, RAGE, TLR4, NF-kappaB expression, ameliorates BBB permeability and endothelial cell function, and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res 1321:143–151. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Huang J, Chen X, Gu X, Wang Y, Zeng L, Yang GY (2014) Increase of circulating miR-223 and insulin-like growth factor-1 is associated with the pathogenesis of acute ischemic stroke in patients. BMC Neurol 14:77. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-14-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Xie R, Zhang H, Gu L, Xie W, Cheng M, Jian Z, Kovacina K, Zhao H (2014) PRAS40 plays a pivotal role in protecting against stroke by linking the Akt and mTOR pathways. Neurobiol Dis 66:43–52. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M, Siegel C, Zeng Z, Li J, Liu F, McCullough LD (2009) Sex differences in the response to activation of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase pathway after experimental stroke. Exp Neurol 217(1):210–218. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Liu J, Wang Y, Wang L, Weng S, Tang Y, Zheng C, Cheng Q, Chen S, Yang GY (2011) MicroRNA-210 as a novel blood biomarker in acute cerebral ischemia. Front Biosci 3:1265–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, He X, Wang Y, Tang Y, Zheng C, Cai H, Liu J, Wang Y, Fu Y, Yang GY (2014) MicroRNA-210 overexpression induces angiogenesis and neurogenesis in the normal adult mouse brain. Gene Ther 21(1):37–43. doi:10.1038/gt.2013.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Ding H, Yan J, Wang W, Ma A, Zhu Z, Cianflone K, Hu FB, Hui R, Wang DW (2011a) Plasma tissue kallikrein level is negatively associated with incident and recurrent stroke: a multicenter case–control study in China. Ann Neurol 70(2):265–273. doi:10.1002/ana.22404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liao JM, Zeng SX, Lu H (2011b) p53 downregulates down syndrome-associated DYRK1A through miR-1246. EMBO Rep 12(8):811–817. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wang J, Gao L, Wang R, Liu X, Gao Z, Tao Z, Xu C, Song J, Ji X, Luo Y (2013) MiRNA-424 protects against permanent focal cerebral ischemia injury in mice involving suppressing microglia activation. Stroke. J Cereb Circ 44(6):1706–1713. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R, Liu X, He Z, Li Q (2014) miR-146a and miR-196a2 polymorphisms in patients with ischemic stroke in the northern Chinese Han population. Neurochem Res 39(9):1709–1716. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1364-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.