Abstract

Amyloid β (Aβ) plays a pivotal role in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) through its neurotoxic and inflammatory effects. On one hand, Aβ binds to microglia and activates them to produce inflammatory mediators. On the other hand, Aβ is cleared by microglia through receptor-mediated phagocytosis and degradation. This review focuses on microglial membrane receptors that bind Aβ and contribute to microglial activation and/or Aβ phagocytosis and clearance. These receptors can be categorized into several groups. The scavenger receptors (SRs) include scavenger receptor A-1 (SCARA-1), MARCO, scavenger receptor B-1 (SCARB-1), CD36 and the receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE). The G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) and chemokine-like receptor 1 (CMKLR1). There are also toll-like receptors (TLRs) including TLR2, TLR4, and the co-receptor CD14. Functionally, SCARA-1 and CMKLR1 are involved in the uptake of Aβ, and RAGE is responsible for the activation of microglia and production of proinflammatory mediators following Aβ binding. CD36, CD36/CD47/α6β1-intergrin, CD14/TLR2/TLR4, and FPR2 display both functions. Additionally, MARCO and SCARB-1 also exhibit the ability to bind Aβ and may be involved in the progression of AD. Here, we focus on the expression and distribution of these receptors in microglia and their roles in microglia interaction with Aβ. Finally, we discuss the potential therapeutic value of these receptors in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid β, Microglial cells, Scavenger receptors, G protein-coupled receptors, Toll-like receptors

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause for dementia in older adults, is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a progressive and irreversible decline in cognition and behavior. The two prominent pathological features of AD are the extracellular accumulation of amyloid beta peptides (Aβ) in neuritic plaques and the intercellular aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles (Querfurth and LaFerla 2010). Besides these histopathological hallmarks, activation of inflammatory processes and the innate immune response are observed in the brains of AD patients (Akiyama et al. 2000).

The most widely accepted hypothesis for AD pathogenesis is the “amyloid cascade hypothesis.” It proposes that certain gene mutations or cell injury may induce Aβ accumulation, and Aβ accumulation is a major early event in the pathogenesis of AD (for reviews, see (Selkoe 2001; Regland and Gottfries 1992)). There have been extensive efforts for the development of AD drugs based on this hypothesis, although no clinical trials have been successful to date (Schneider et al. 2014; Karran et al. 2011). One reason for the failed trials is that the enrolled AD subjects are already too advanced to benefit from the treatment; the other reason is that the clinical criteria alone may be prone to misdiagnosis (Blennow et al. 2014; Toyn and Ahlijanian 2014). As a result, further research will be required to improve the amyloid cascade hypothesis and our understanding of the pathogenesis of AD in general.

Aβ, a group of 37–43-animo acid peptides, are produced through sequential cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase and γ-secretase (Thinakaran and Koo 2008). The Aβ40 (40 residues) and Aβ42 (42 residues) peptides are the major Aβ forms in the brain, and Aβ42 is more closely linked to the development of AD (Crouch et al. 2008). Like other amyloid proteins, Aβ has a tendency to aggregate and undergoes conformational changes to become an insoluble form called fibrillar Aβ (fAβ) (Serpell 2000). Although fAβ appears less neurotoxic than oligomeric soluble Aβ (sAβ), both of them display neurotoxicity through their direct action on neurons and indirect action through activation of glial cells to produce toxic inflammatory mediators, ultimately leading to progressive neurodegeneration as seen in AD (Wyss-Coray 2006; Hardy and Selkoe 2002).

A wealth of published studies demonstrated the important role for inflammation in the development of AD (Morales et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2013). Microglia, the resident macrophages in the brain, are the primary immune cells responding to invading pathogens and neuronal injuries in the central nervous system (CNS) (Streit et al. 1999). However, the origin of microglia remains controversy in spite of intense studies (for reviews, see (Chan et al. 2007; Hickman and El Khoury 2010)). Microglia constantly scavenge the CNS for plaques, damaged neurons and infectious agents. Microglia cells can be activated not only by injury and infection (Tuppo and Arias 2005), but also by stimulators (Minghetti et al. 2005; Yu et al. 2014) including Aβ (McGeer et al. 1987). Activated microglial cells exhibit dramatic morphological changes, proliferate, migrate, and produce a variety of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (Tuppo and Arias 2005; Banati et al. 1993). Although a few published studies showed that microglia may have no effect on Aβ plaque burden in AD mouse models (Grathwohl et al. 2009; Ulrich et al. 2014), many other studies support that microglia have an important role in plaque clearance and contribute to AD progression (Zhu et al. 2011; Koenigsknecht-Talboo and Landreth 2005; Wyss-Coray et al. 2001; Takata et al. 2007; Simard et al. 2006; Mandrekar et al. 2009) (for a review, see (Guillot-Sestier and Town 2013)). Generally, Microglia are believed to clear Aβ at early stages of AD, but as the disease progresses, the ability of phagocytosis decreases due to reduced expression of their Aβ-binding receptors and Aβ-degrading enzymes. However, microglia maintain their ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines induced by soluble Aβ or Aβ deposits (Hickman et al. 2008). These cytokines may in turn act in an autocrine manner and further reduce the expression of Aβ-binding receptors and Aβ-degrading enzymes, thereby leading to decreased Aβ clearance and increased Aβ accumulation (Hickman et al. 2008; Bolmont et al. 2008). Ultimately, this toxic inflammatory environment impairs the surrounding neurons, resulting in neuronal degeneration as AD progresses (Hickman et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2010). Therefore, promoting Aβ phagocytosis and degradation, inhibiting sustained activation of microglial cells, and limiting inflammatory cytokine production are expected to be beneficial for the prevention of AD progression.

It is known that Aβ induces microglia activation and phagocytosis through binding to receptors on the plasma membrane of microglia (Verdier and Penke 2004). Several receptors have been identified in microglia as endogenous binding sites for Aβ, including the scavenger receptors (SRs), G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and toll-like receptors (TLRs). In this review, we focus on the distribution and expression of these receptors in microglial cells and their roles in Aβ-microglia interaction. We also discuss the potential therapeutic value of these receptors in AD. Due to page limitation, Aβ receptors on other types of cells such as neurons (Verdier and Penke 2004; Kim et al. 2013) are not covered in this short review.

Scavenger Receptors

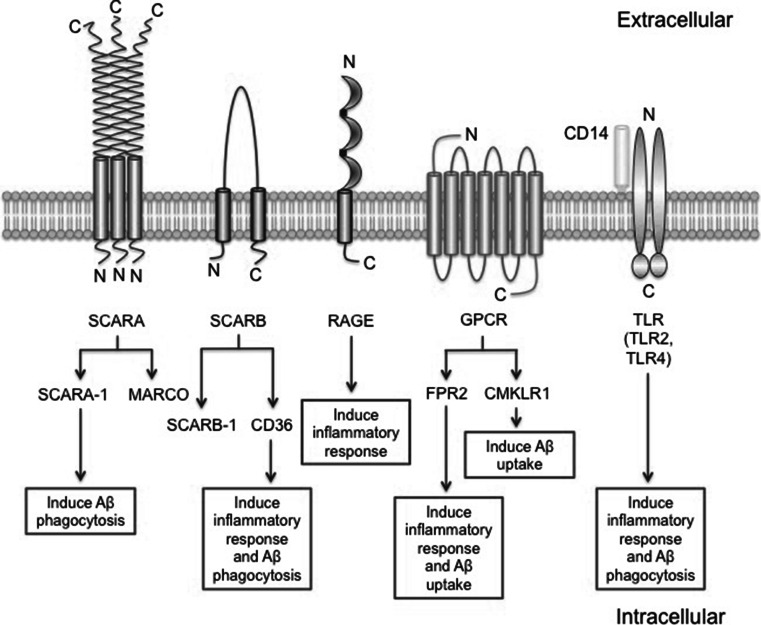

Scavenger receptors (SRs), named after their function of clearance (scavenging), consist of a broad family of membrane receptors that recognizes and internalizes modified low density lipoproteins (LDL) and several other ligands including Aβ (Krieger 1997; El Khoury et al. 1996; Paresce et al. 1996). SRs are divided into six classes: SCARA (SCARA-1, MARCO), SCARB (SCARB-1, CD36), SCARC, SCARD (CD68), SCARE (LOX-1), and SCARF (MEGF10). Additional members of this family, like the receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE), CD163, and SR-PSOX, remain unclassified (for a review, see (Wilkinson and El Khoury 2012)). In this part we will discuss the main SRs that are known to bind Aβ and involved in the inflammatory response and in clearance of Aβ (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Aβ interaction with microglial receptors that reported to be involved in Alzheimer’s disease

| Receptor | Aβ (binding) | Expression | Relevance to AD (microglia) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRs | SCARA-1 | sAβ and fAβ | Microglia, macrophages, and monocytes | ↑ sAβ and fAβ phagocytosis | (Reichert and Rotshenker 2003; Yang et al. 2011; Frenkel et al. 2013) |

| MARCO | sAβ and fAβ | Microglia, macrophages, and monocytes | Along with FPR2 involved microglia inflammatory response | (Elomaa et al. 1995; Alarcon et al. 2005; Brandenburg et al. 2010) | |

| SCARB-1 | fAβ | Microglia in human fetal brains, perivascular macrophages, astrocytes | ↓ fAβ deposition and amyloid plaque by perivascular macrophages | (Husemann et al. 2001; Mulder et al. 2012; Thanopoulou et al. 2010) | |

| CD36 | fAβ | Microglia, macrophages, monocytes and astrocytes | ↑ ROS and Aβ phagocytosis | (Moore et al. 2002; Yamanaka et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Kawahara et al. 2012) | |

| CD36/CD47/α6β1-integrin | fAβ | Microglia | ↑ ROS and Aβ phagocytosis | (Bamberger et al. 2003; Koenigsknecht and Landreth 2004) | |

| CD36/TLR4/TLR6 | fAβ | Microglia | Stimulate sterile inflammation | (Stewart et al. 2010) | |

| RAGE | sAβ | Microglia and astrocytes | Induce proinflammatory mediators and cell migration | (Lue et al. 2001; Choi et al. 2014; Yan et al. 1996) | |

| GPCRs | FPR2 | sAβ and fAβ | Macrophages, monocytes and astrocytes | Induce inflammatory response and uptake Aβ | (Le et al. 2001; Yazawa et al. 2001) |

| CMKLR1 | sAβ | Microglia and astrocytes | ↑ Aβ uptake | (Peng et al. 2014) | |

| TLRs | CD14/TLR2/TLR4 | fAβ | Microglia | Induce inflammatory response and Aβ phagocytosis | (Fassbender et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2005; Tahara et al. 2006) |

Fig. 1.

The structures and functions of microglia Aβ receptors. SCARA has a collagen-like domain, which is essential for ligand binding. SCARB has two transmembrane domains. RAGE is a transmembrane receptor of the immunoglobulin super family. GPCRs are known as seven-transmembrane domain receptors. CD14 anchors to the membrane and acts as a co-receptor along with the TLR2 or TLR4 for interaction with Aβ. TLRs are single membrane spanning and these two TLRs are believed to function as dimers. SCARA-1 and CMKLR1 are involved in the uptake of Aβ, and RAGE is responsible for the activation of microglia and production of proinflammatory mediators following Aβ binding. CD36 and FPR2 display both functions. Additionally, the exact roles of MARCO and SCARB-1 in microglia following Aβ binding need further investigation

SCARA-1

SCARA-1 has been shown to express on human and rodent macrophages (Hughes et al. 1995; Syvaranta et al. 2014), microglia (Paresce et al. 1996; Reichert and Rotshenker 2003; Yang et al. 2011) and on human monocytes (El Khoury et al. 1996). SCARA-1 expression is upregulated in microglia along with amyloid deposits in AD brains (Christie et al. 1996; Honda et al. 1998). SCARA-1 expression is also upregulated in APP23 mice (Bornemann et al. 2001), a transgenic mouse model for AD, suggesting induction of SCARA-1 in microglia under pathological conditions of AD.

In addition, SCARA-1 has been reported to regulate the adhesion of rodent microglia and monocyte to fAβ coated surface, leading to the production of ROS (El Khoury et al. 1996) and to Aβ internalization in microglia (Husemann and Silverstein 2001; Chung et al. 2001). SCARA-1 also mediates binding and ingestion of fAβ and sAβ by cultured human fetal microglia and naïve primary microglia, respectively (Yang et al. 2011). The direct evidence that SCARA-1 is a key phagocytic receptor for Aβ comes from studies using microglia and/or monocytes from SCARA-1 knock-out (KO) mice. Scara1 KO led to a 50–60 % reduction in the uptake of sAβ by fresh monocytes and microglia (Frenkel et al. 2013; Huang et al. 2013) and a 60 % reduction in fAβ uptake by microglia, compared with wild-type cells (Chung et al. 2001). These results indicate that, besides SCARA-1, other receptors may be involved in clearance of sAβ and fAβ by microglia. In addition, in vivo experiments showed that Scara1 deficiency increased Aβ accumulation in APP/PS1-Scara1−/− mice compared with APP/PS1 mice, in association with an increase in the mortality of the APP/PS1-Scara1−/− mice. Pharmacological upregulation of Scara1 using Protollin (proteosomes non-covalently complexed with LPS) leads to increased Aβ uptake and clearance by mononuclear phagocytes and microglia (Frenkel et al. 2013). However, another study reported that upregulation of Scara1 mRNA in aging AD mice following irradiation does not reduce the amount of soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 as seen with Protollin, but decreases the levels of insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 (Mildner et al. 2011). The contradictory results may be due to several factors including permeability of the blood brain barrier which is increased following brain irradiation, differences in the age and genotype of the mice analyzed (Frenkel et al. 2013), and the balance of insoluble Aβ and soluble Aβ. Further experiments are needed to confirm whether there is a dynamic exchange between insoluble Aβ and soluble Aβ, and whether this exchange contributes to homeostatic level of soluble Aβ along with its clearance. Nonetheless, these results suggest that SCARA-1 is involved in the clearance of Aβ by microglia and monocytes, and upregulating Scara1 expression with pharmacological agents may be beneficial in delaying AD progression.

MARCO

MARCO, the macrophage receptor with collagenous structure, is another member of the SRs class A family. MARCO is present at a very low level in human brain, cultured human astrocytes and rodent microglial cells, but is highly expressed in rodent astrocytes and macrophages (Granucci et al. 2003; Elshourbagy et al. 2000; Perez et al. 2010; Mulder et al. 2012; Alarcon et al. 2005). MARCO, as another receptor for Aβ, participates in rat microglia adhesion to sAβ and fAβ (Alarcon et al. 2005). By coimmunoprecipitation and fluorescence microscopy, MARCO shows physical and functional interaction with formyl peptide receptor (FPR2) (Brandenburg et al. 2010). The role of FPR2 will be discussed in detail later in this review. The complex of FPR2 and MARCO is involved in Aβ-induced signal transduction and inflammatory response in microglia (Brandenburg et al. 2010). Future experiments are required to confirm the expression of MARCO in microglia in AD brains and its function in Aβ clearance.

SCARB-1

SCARB-1 expresses and binds fAβ by cultured microglia in newborn mouse and human fetal brains, cultured astrocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in normal adult mouse and human brains and in AD brains but not by microglia in normal adult mouse and human brains, indicating that SCARB-1 may mediate the interaction between astrocytes or SMCs and fAβ, but not that of microglia and fAβ in AD, and that expression of SCARB-1 is developmentally regulated in human and rodent microglia (Husemann and Silverstein 2001; Husemann et al. 2001). SCARB-1 expression is increased upon exposure to ApoE in combination with fAβ in primary human astrocytes from non-demented controls but not in AD patient brain (Mulder et al. 2012), suggesting that the regulatory mechanism for SCARB-1 expression may be defective in astrocytes from AD patients. However, other studies imply that SCARB-1 may contribute to the progression of AD pathology through perivascular macrophages. SCARB-1 expression is significantly increased in the brains of an AD mouse model (J20), in which a single SCARB-1 allele deletion is sufficient to enhance fAβ vascular deposition and amyloid plaque formation in the brain, and to exacerbate animal behavioral abnormalities with a distinctive increase in perivascular macrophages in the brain (Thanopoulou et al. 2010). SCARB-1 reduction has little effect on the ability of peripheral macrophage and microglial cells to bind Aβ (Thanopoulou et al. 2010), and inhibition of SCARB-1–Aβ interaction does not affect binding of Aβ by astrocytes (Wyss-Coray et al. 2003). All these data suggest that the effect on amyloid deposition by SCARB-1 is mediated primarily by perivascular macrophages, although direct interaction of SCARB-1 and Aβ in perivascular macrophages requires further proof.

CD36

CD36, another member of SCARB family, has been found in human and rodent macrophages (Savill et al. 1992; El Khoury et al. 2003), microglia (Coraci et al. 2002; Hickman et al. 2008), and rodent astrocytes (Bao et al. 2012). CD36 is a receptor for Aβ and appears to be involved in the pathology of AD by regulating brain inflammation and Aβ clearance.

The expression of CD36 in the brains of the senescence-accelerated mice (SAMP8) is increased compared with that of the control mice (SAMR1) (Wu et al. 2013). Another study reported that in aging APP/PS1 transgenic mice, the expression of CD36 is decreased in microglia compared with younger mice (Hickman et al. 2008). fAβ induced a marked increase in CD36 mRNA expression in microglial cells (Kouadir et al. 2011), and pretreatment with oligomeric Aβ42 down-regulated fAβ induced over-expression of CD36 mRNA in microglia (Pan et al. 2011). These data suggest that CD36 expression may be regulated by Aβ in the course of AD development.

Further studies have shown that, in CD36 KO mice, fAβ-induced secretion of inflammatory mediators and microglial/macrophage recruitment is marked reduced (El Khoury et al. 2003). Furthermore, CD36 binds with fAβ and drives the signaling cascade leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Moore et al. 2002) through formation of a receptor complex with integrin-associated protein (IAP, CD47) and the α6β1-integrin (Bamberger et al. 2003). The complex may also contain TLR4 and TLR6 that are expressed on the cell surface (Stewart et al. 2010). The role of TLRs in amyloidosis will be discussed in a later section. Altogether, these results imply that CD36, upon binding to Aβ and forming a complex with other cell surface receptors, stimulates recruitment of microglia and produces inflammatory mediators in the brain.

In addition, stimulation of astrocytes with an Aβ cocktail (Aβ42+Aβ40) increases the expression of CD36, and blocking CD36 attenuates Aβ induced phagocytosis in astrocytes (Jones et al. 2013). The binding of fAβ to the receptor complex CD36/CD47/α6β1-intergrin has also been shown to drive a tyrosine kinase-based signaling cascade leading to stimulation of phagocytic activity (Wilkinson et al. 2006; Koenigsknecht and Landreth 2004). In vivo, increased expression of CD36, through either PPARγ activation or administration of NRF2 or IL-4/IL-13 into the brain enhances Aβ phagocytosis and clearance, thereby improving cognition in the AD mouse models (Yamanaka et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Kawahara et al. 2012). These data suggest that CD36 is involved in Aβ phagocytosis and clearance by glial cells, and increased expression of CD36 may prove beneficial in preventing AD.

CD36, as a receptor of Aβ, display dual functions in AD: one is harmful that induces the microglia activation and inflammatory mediator release when bound to Aβ, the other one is beneficial that induces the Aβ phagocytosis and clearance. Therefore, agents that inhibit Aβ induced inflammatory response in microglia and enhance phagocytosis of Aβ are expected to have good therapeutic value for the treatment of AD.

RAGE

RAGE is expressed in microglial cells, astrocytes, and neurons in human and rodent brain (Lue et al. 2001; Yan et al. 1996; Brett et al. 1993; Choi et al. 2014; Fang et al. 2010). The expression of RAGE is significantly increased in astrocytes in the hippocampal CA1 of the old 3xTg AD mice (a triple transgenic mouse model of AD) compared with age-matched controls (Choi et al. 2014). RAGE binds sAβ, mediates and enhances Aβ-induced microglial activation, leading to induction of proinflammatory mediators and migration of glial cells (Yan et al. 1996). Inhibition of RAGE suppresses microglia activation and the associated inflammatory response in aged APPsw/o mice that overexpresses human APP (Deane et al. 2012). Overexpression of RAGE in microglia increases tissue infiltration of glial cells, microglia activation, Aβ accumulation and deterioration of cognitive functions in APP transgenic mice (Fang et al. 2010). Consistent with these findings, another study shows that RAGE deficiency combined with transgenic expression of the Swedish and Arctic APP mutations results in a marked decrease in Aβ deposition and an increase in insulin degrading enzyme (IDE), which cleaves Aβ, at the age of 6 months. However, no improvement in cognitive performance or difference in Aβ accumulation and microglial recruitment to plaques has been seen in 12 months old mice (Vodopivec et al. 2009), suggesting that RAGE may be essential for microglial activation and Aβ processing in early disease state. Furthermore, studies using a dominant negative form of RAGE show that microglial RAGE activation through Aβ stimulation induces specific phosphorylation of p38 MARK and JNK, which lead to IL-1 induction and synaptic dysfunction in entorhinal cortex (Origlia et al. 2010). These results suggest that RAGE-dependent signaling in microglial cells is involved in neuron synaptic dysfunction.

G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

GPCRs, also known as seven-transmembrane domain receptors, constitute a large protein family of receptors that sense molecules outside the cell and activate intracellular signal transduction pathways, leading to cellular responses (Selbie and Hill 1998). In AD, GPCRs directly influence the amyloid cascade through modulation of the α-, β- and γ-secretases, proteolysis of the APP, and regulation of Aβ degradation. In addition, Aβ has been shown to perturb GPCR function (for a review, see (Thathiah and De Strooper 2011)). Here, we will discuss major GPCRs expressed on microglial membrane that have been shown to bind Aβ for their potential involvement in the progression of AD.

Formyl Peptide Receptor 2 (FPR2)

FPR2, originally cloned as an orphan receptor, recognizes a diverse array of chemotactic agonists including fMLF (high concentration), W peptide, and Aβ (Tiffany et al. 2001; Cui et al. 2002a; Le et al. 2001; Ye et al. 2009). FPR2 is moderately expressed in human and rodent monocytes, macrophages, and astrocytes (Le et al. 2001; Hughes et al. 1995; Decker et al. 2009; Yazawa et al. 2001; Slowik et al. 2012; Lee and Surh 2013). Previous studies have shown that, in mice, the expression level of Fpr2 is very low in microglia at resting state (Cui et al. 2002c). When stimulated with TNFα, synergistically with IL-10, or a plethora of TLR agonists (Cui et al. 2002b, 2002c; Iribarren et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2008), microglial cells express high levels of mFpr2 transcripts. Consequently, these cells display enhanced chemotaxis to mFpr2-specific agonists and increased capacity to phagocytose Aβ. In contrast, stimulation with IL-4 or TGFβ inhibits the expression of mFpr2 and attenuates LPS-induced signaling cascade in microglial cells (Iribarren et al. 2005). These results indicate that factors that regulate inflammation, such as cytokines, may alter the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals in the brain by regulating FPR2 expression and the ability of microglial cells to respond to Aβ. In addition, FPR2 interacts with RAGE directly and their colocalization is increased in the glial cells from APP/PS1 mice (Slowik et al. 2012). However, the exact role for these receptor complexes in AD requires further investigation.

As a receptor for Aβ, FPR2 regulates the proinflammatory response and mediates Aβ uptake in glia cells. An early study shows that bacterial fMLF and FPR antagonist inhibit Aβ42-induced IL-1β production from human THP-1 monocytes and primary rat microglia, suggesting that Aβ may interact with a FPR-like receptor (Lorton et al. 2000). A subsequent study has shown that Aβ42 is a chemotactic agonist for FPR2, and also induces calcium flux in FPR2-transfected cells (Le et al. 2001). Moreover, FPR2 is highly expressed in inflammatory cells infiltrating senile plaques in brain tissues from AD patients (Le et al. 2001), suggesting that FPR2 may mediate inflammatory response in AD. The role of FPR2 in the cellular uptake and subsequent fibrillar formation of Aβ42 has been examined using fluorescence confocal microscopy. Aβ42 is found to associate with FPR2 and the Aβ42/FPR2 complexes are rapidly internalized into the cytoplasmic compartment. Persistent exposure of the cells to Aβ42 over 24 h results in retention of Aβ42/FPR2 complexes in the cytoplasmic compartment and formation of Congo red positive fibrils in macrophages (Yazawa et al. 2001). These results suggest that FPR2 may be involved in the internalization and clearance of Aβ42. Additional experiments are required to confirm the functions of FPR2 in AD mouse models.

Chemokine-Like Receptor 1 (CMKLR1)

CMKLR1, known as the chemerin receptor (ChemR23), is also a GPCR initially known as an orphan receptor with homology to several chemokine receptors (Gantz et al. 1996). CMKLR1 has been reported expressed in human brain (Peng et al. 2014) and in mouse microglia, astrocytes, and monocytes (Methner et al. 1997; Arita et al. 2005; Peng et al. 2014). It recognizes chemerin, resolvin E1 (RvE1) and the chemerin-derived peptide C9 as its agonists (Wittamer et al. 2003, 2004; Arita et al. 2007). Little is known for its role in neurodegenerative diseases.

Recently, we found that CMKLR1 is colocalized with Aβ in hippocampus and frontal cortex in the brain of APP/PS1 transgenic mice and sAβ42 bound specifically to CMKLR1 in stably transfected rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells (CMKLR1-RBL), suggesting that CMKLR1 is a new member of the family of Aβ42 receptors (Peng et al. 2014). Aβ42 has the feature of a “biased ligand” (Reiter et al. 2012) at CMKLR1, as it selective activate certain CMKLR1-mediated functions (Peng et al. 2014). C9, a chemerin-derived nonapeptide that retains most of the agonistic activity of chemerin, induces robust Ca2+ flux in CMKLR1-RBL cells (Wittamer et al. 2004; Peng et al. 2014). However, Aβ42 fails to induce Ca2+ mobilization even when used at concentrations up to 20 μM (Peng et al. 2014). Aβ42 binds CMKLR1 and induces the migration in CMKLR1-RBL cells and primary microglia. It also induces internalization of the Aβ–CMKLR1 complex in the glial cells, suggesting a potential role for CMKLR1 in the chemotaxis of microglial cells and the clearance of Aβ42. Further mechanistic studies showed that Aβ42 induced migration through CMKLR1 by selectively activating ERK1/2 and the PKA/Akt pathway, but the induced migration was independent of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in CMKLR1-RBL cells (Peng et al. 2014). Interestingly, CMKLR1 activation does not seem to induce the production of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, IL-12, and iNOS (our unpublished data). These results suggest that CMKLR1, which promotes the migration of microglia and uptake of Aβ42 and has no effect on the activation of microglia, may be a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

It is notable that CMKLR1 shares sequence homology with FPR2, which has been known as a functional receptor for Aβ. However, although both receptors are coupled to Gαi proteins and share 36 % identity in amino acid sequence (Peng et al. 2014), CMKLR1 and FPR2 respond to Aβ42 differently. The lack of Aβ-induced Ca2+ mobilization in CMKLR1-RBL cells is of particular interest, as this second messenger is highly important for several signaling pathways downstream of the activated GPCR. Furthermore, amyloid proteins such as Aβ and serum amyloid A (SAA) do not bear significant sequence homology, but they all form fibrillary aggregates and have some common receptors. For instance, FPR2, CD36, and RAGE are receptors for both Aβ and SAA (Le et al. 2001; El Khoury et al. 2003; Yan et al. 1996; Paresce et al. 1996). However, CMKLR1-RBL cells did not respond to SAA in chemotaxis and calcium mobilization assays, nor did this receptor bind WKYMVm, a potent agonist for FPR2 (our unpublished data). It would be interesting and necessary to investigate how these diverse ligands activate their respective receptors, which will be beneficial to screen for potential drugs for AD and amyloidosis treatment (Fig. 1).

Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs)

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) characterized by an extracellular leucine-rich repeat domain and an intracellular Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain (Kielian 2006) (Fig. 1). In mammals, there are at least ten TLRs that play distinct functions in innate immune response. Each TLR has different ligand specificity that is extended through dimerization of the TLRs or additional co-receptors, such as CD14 for TLR4 and TLR2 (Kielian 2006). Here we will discuss the CD14/TLR2/TLR4 that are involved in the inflammatory response and clearance of Aβ (Table 1).

The CD14 co-receptor lacks a direct intracellular signaling domain, hence signals are transmitted through TLR2 or TLR4. High levels of CD14 are found in the microglia of AD patients (Liu et al. 2005) and of the APP23 mouse model of AD (Fassbender et al. 2004). Consistent with this, other studies have shown that in APP TgCRND8 transgenic mice, the transcripts and protein expression levels of TLR2 (Letiembre et al. 2009) and CD14 (Walter et al. 2007; Letiembre et al. 2009) are constantly upregulated and also show an inverse expression pattern in regard to its special distribution (Letiembre et al. 2009). CD14-positive cells have been detected around the Aβ plaques in the cortex, whereas TLR2-positive cells have been found to associate with Aβ plaques within the amygdala where CD14 immunoreactivity is barely detectable (Letiembre et al. 2009). In human AD brains, CD14 and TLR2-positive cells are localized in microglial cells and are associated with the Aβ plaques, and there are a greater number of CD14-positive cells surrounding the diffused Aβ plaques compared to dense-core Aβ plaques (Letiembre et al. 2009). All these studies suggest that the expression of CD14 and TLRs may be associated with Aβ accumulation in AD.

Additional studies have provided evidence that CD14 and TLR2/TLR4 form a receptor complex, and together they participate in the inflammatory response induced by fAβ. It has been reported that CD14 binds fibrillar Aβ but not nonfibrillar Aβ. Neutralization with antibodies against CD14 and genetic deficiency of this receptor significantly reduces Aβ-induced microglial activation (Fassbender et al. 2004). These results indicate that CD14 along with TLR4 can induce NF-κB nuclear translocation and consequently induce production of pro-inflammatory mediators in murine microglia and human peripheral blood monocytes (Fassbender et al. 2004). Besides CD14, there is also a direct interaction between TLR2 and the aggregated Aβ42. TLR2 deficiency reduces Aβ42-triggered inflammatory activation but enhances Aβ phagocytosis in cultured microglia and macrophages (Liu et al. 2012). Inhibition of TLR4 or TLR2 in human monocytes and murine microglia, or lack of CD14, TLR2, or TLR4 in microglia, abolishes the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators or a phagocytic response following fAβ exposure (Walter et al. 2007; Jana et al. 2008; Udan et al. 2008; Reed-Geaghan et al. 2009; Vollmar et al. 2010). An association with the Src-Vav-Rac cascade or p38 MAPK pathway has been implicated (Wilkinson et al. 2006; McDonald et al. 1998; Bachstetter et al. 2011). Moreover, AD mice lacking TLR2 or TLR4 display increased glial cell activation markers (Jin et al. 2008) and TGF-β transcripts (Richard et al. 2008). AD mice lacking CD14 showed increased expression of inflammatory mediators such as TNFα, IFNγ, and IL-10, and decreased levels of the microglial alternative activation markers Fizz1 and Ym1 (Reed-Geaghan et al. 2010). These studies suggest that these innate immune receptors function as members of the microglial fAβ receptor complex and are involved in microglial activation.

Besides the ability to recognize fAβ and mediate microglial activation, the TLR-CD14 complex are involved in the clearance of Aβ from the brain. Liu et al. reported that fAβ42 and CD14 co-localize at the surfaces of wild-type microglia under confocal microscopy, and subsequently, this complex of fAβ42/CD14 is rapidly internalized and co-localizes with the lysosomal marker LAMP-2. CD14 wild-type microglia internalizes significantly more fAβ42 than the CD14 KO microglia, suggesting the requirement for CD14 in microglial phagocytosis of fAβ42 (Liu et al. 2005). In addition, the in vivo role of TLR4 and TLR2 in amyloidogenesis has also been investigated. Tahara et al. showed that APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice lacking functional TLR4 have increases in diffuse and fibrillar Aβ in the cerebrum and hippocampus, compared with TLR4 wild-type mouse model at the age of 14–16 months (Tahara et al. 2006). Consistent with these in vivo observations, cultured microglia derived from TLR4 deficient mice fail to show an increase in Aβ uptake in response to TLR4 ligand stimulation (Tahara et al. 2006). However, APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice lacking CD14 exhibit decreased plaque burden at 7 months of age, resulting in a reduction of both diffuse and thioflavin S-positive plaques and an overall reduction in the number of microglia. Knock-out of the Tlr2 gene in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice also results in decreased level of plaque deposition for up to 6 months, but the level returns to normal in 9-month-old mouse brain (Richard et al. 2008). The different results for Aβ deposition between TLR4 KO mice and TLR2 or CD14 KO mice may be explained by the different age of the mice they used (Landreth and Reed-Geaghan 2009) or other microglial surface Aβ-binding receptors involved. One study investigated the role of TLR4 signaling and microglial activation in early stages and found no difference in cerebral Aβ load between APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice at 5 months with and without TLR4 deficiency (Song et al. 2011). While microglial activation in the mutant TLR4 APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice is less than that in the WT TLR4 APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice, the TLR4 mutant APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice have increased soluble Aβ42 and Aβ deposition in the brain compared to TLR4 wild-type APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice at 9 months (Song et al. 2011). Hickman et al. showed that as APP/PS1 mice age, their microglia become dysfunctional and exhibit a significant reduction in the expression of their Aβ-binding receptors and Aβ-degrading enzymes, but maintain their ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines (Hickman et al. 2008). These cytokines may in turn act in an autocrine manner and further reduce expression of Aβ-binding receptors and Aβ-degrading enzymes, leading to decreased Aβ clearance and increased Aβ accumulation (Hickman et al. 2008). All these findings indicate that CD14/TLR2/TLR4 may be involved in the activation of microglia at the early stage of β-amyloidosis, but not in the initiation of Aβ deposition. As Aβ aggregation increases, microglia activated via these receptors may display enhanced Aβ phagocytosis, thereby contributing to the reduction of Aβ deposition and preservation of cognitive functions (Song et al. 2011).

For therapeutic application, it may be advantageous to inhibit receptor binding of Aβ, which induces activation of microglia and release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Michaud et al. reported that monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), a lipopolysaccharide-derived TLR4 agonist, decreases Aβ deposits and enhances cognitive function through stimulating microglial phagocytosis of Aβ, while it only triggers a moderate proinflammatory response (Michaud et al. 2013). Resveratrol, a natural polyphenol associated with anti-inflammatory effects and currently in clinical trials for AD, also prevented the pro-inflammatory properties of fAβ on macrophages by inhibiting the effects of Aβ on IκB phosphorylation, STAT1 and STAT3 activation, and TNFα and IL-6 secretion. In vivo studies in a mouse model of cerebral amyloid deposition showed that oral administration of resveratrol in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice reduces microglial activation associated with cortical amyloid plaque formation (Capiralla et al. 2012). In addition, bisdemethoxycurcumin, a natural curcumin, increases the transcription of selected TLR genes and enhances phagocytosis and clearance of Aβ in cells derived from most AD patients tested (Fiala et al. 2007). Together, these studies provide strong evidence that the above agents may have the potential for therapeutic intervention of AD.

Conclusions

Aβ, as a major component of the senile plaque, participates in AD progression through its neurotoxic effects. These include direct impairment of neurons and an indirect effect resulting from the production of inflammatory mediators by activated microglia (Wyss-Coray 2006). In this process, the binding of Aβ to microglial membrane receptors appears to be a critical step. Receptors expressed on microglia alone or along with their co-receptors play complementary and non-redundant roles in the interaction with Aβ in AD. While the interactions between Aβ and SCARA-1 as well as Aβ and CMKLR1 promotes Aβ clearance and therefore are beneficial (Frenkel et al. 2013; Peng et al. 2014), RAGE–Aβ interaction is harmful and produces neurotoxins as well as proinflammatory mediators (Yan et al. 1996). In comparison, the interactions between Aβ and CD36, CD36/CD47/α6β1-intergrin, CD14/TLR2/TLR4 and FPR2 show the dual functions (beneficial and harmful) in AD (Table 1). Such differential roles of receptors may be explored for therapeutic applications. Drugs that enhance SCARA-1 and CMKLR1 expression or phagocytosis function may be helpful for treatment of AD, whereas drugs that reduce RAGE expression or block RAGE binding to Aβ may delay AD progression. For CD36, CD36/CD47/α6β1-intergrin, CD14/TLR2/TLR4 and FPR2, it may be advantageous to use their ability to bind Aβ and promote Aβ uptake through enhancement of phagocytosis in microglial cells. In addition to these receptors, MARCO and SCARB-1 also exhibit the ability to bind Aβ and may be involved in the progression of AD (Table 1). Therefore, the recognition of the complex roles of various microglial receptors in binding Aβ is important for the understanding of the pathogenesis of AD and for finding appropriate targets for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 31270941 to R.D.Y. and Grant 81200843 to Y.Y.), from National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, Grant 2012CB518001, to R.D.Y.), and from the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (Grant 20120073110069, to R.D.Y. and Grant 20120073120091, to Y.Y.). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, Finch CE, Frautschy S, Griffin WS, Hampel H, Hull M, Landreth G, Lue L, Mrak R, Mackenzie IR, McGeer PL, O’Banion MK, Pachter J, Pasinetti G, Plata-Salaman C, Rogers J, Rydel R, Shen Y, Streit W, Strohmeyer R, Tooyoma I, Van Muiswinkel FL, Veerhuis R, Walker D, Webster S, Wegrzyniak B, Wenk G, Wyss-Coray T (2000) Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 21(3):383–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon R, Fuenzalida C, Santibanez M, von Bernhardi R (2005) Expression of scavenger receptors in glial cells. Comparing the adhesion of astrocytes and microglia from neonatal rats to surface-bound beta-amyloid. J Biol Chem 280(34):30406–30415. doi:10.1074/jbc.M414686200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita M, Bianchini F, Aliberti J, Sher A, Chiang N, Hong S, Yang R, Petasis NA, Serhan CN (2005) Stereochemical assignment, antiinflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E1. J Exp Med 201(5):713–722. doi:10.1084/jem.20042031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita M, Ohira T, Sun YP, Elangovan S, Chiang N, Serhan CN (2007) Resolvin E1 selectively interacts with leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and ChemR23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol 178(6):3912–3917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachstetter AD, Xing B, de Almeida L, Dimayuga ER, Watterson DM, Van Eldik LJ (2011) Microglial p38alpha MAPK is a key regulator of proinflammatory cytokine up-regulation induced by toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands or beta-amyloid (Abeta). J Neuroinflammation 8:79. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger ME, Harris ME, McDonald DR, Husemann J, Landreth GE (2003) A cell surface receptor complex for fibrillar beta-amyloid mediates microglial activation. J Neurosci 23(7):2665–2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banati RB, Gehrmann J, Schubert P, Kreutzberg GW (1993) Cytotoxicity of microglia. Glia 7(1):111–118. doi:10.1002/glia.440070117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Qin L, Kim E, Bhosle S, Guo H, Febbraio M, Haskew-Layton RE, Ratan R, Cho S (2012) CD36 is involved in astrocyte activation and astroglial scar formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32(8):1567–1577. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2012.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Dubois B, Fagan AM, Lewczuk P, de Leon MJ, Hampel H (2014) Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmont T, Haiss F, Eicke D, Radde R, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Kohsaka S, Jucker M, Calhoun ME (2008) Dynamics of the microglial/amyloid interaction indicate a role in plaque maintenance. J Neurosci 28(16):4283–4292. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4814-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornemann KD, Wiederhold KH, Pauli C, Ermini F, Stalder M, Schnell L, Sommer B, Jucker M, Staufenbiel M (2001) Abeta-induced inflammatory processes in microglia cells of APP23 transgenic mice. Am J Pathol 158(1):63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg LO, Konrad M, Wruck CJ, Koch T, Lucius R, Pufe T (2010) Functional and physical interactions between formyl-peptide-receptors and scavenger receptor MARCO and their involvement in amyloid beta 1-42-induced signal transduction in glial cells. J Neurochem 113(3):749–760. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett J, Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Zou YS, Weidman E, Pinsky D, Nowygrod R, Neeper M, Przysiecki C, Shaw A et al (1993) Survey of the distribution of a newly characterized receptor for advanced glycation end products in tissues. Am J Pathol 143(6):1699–1712 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capiralla H, Vingtdeux V, Zhao H, Sankowski R, Al-Abed Y, Davies P, Marambaud P (2012) Resveratrol mitigates lipopolysaccharide- and Abeta-mediated microglial inflammation by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-kappaB/STAT signaling cascade. J Neurochem 120(3):461–472. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07594.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WY, Kohsaka S, Rezaie P (2007) The origin and cell lineage of microglia: new concepts. Brain Res Rev 53(2):344–354. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Zhang L, Huang J, Gong W, Dunlop NM, Wang JM (2008) Cooperation between NOD2 and Toll-like receptor 2 ligands in the up-regulation of mouse mFPR2, a G-protein-coupled Abeta42 peptide receptor, in microglial cells. J Leukoc Biol 83(6):1467–1475. doi:10.1189/jlb.0907607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BR, Cho WH, Kim J, Lee HJ, Chung C, Jeon WK, Han JS (2014) Increased expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in neurons and astrocytes in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Mol Med 46:e75. doi:10.1038/emm.2013.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie RH, Freeman M, Hyman BT (1996) Expression of the macrophage scavenger receptor, a multifunctional lipoprotein receptor, in microglia associated with senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol 148(2):399–403 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Brazil MI, Irizarry MC, Hyman BT, Maxfield FR (2001) Uptake of fibrillar beta-amyloid by microglia isolated from MSR-A (type I and type II) knockout mice. NeuroReport 12(6):1151–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coraci IS, Husemann J, Berman JW, Hulette C, Dufour JH, Campanella GK, Luster AD, Silverstein SC, El-Khoury JB (2002) CD36, a class B scavenger receptor, is expressed on microglia in Alzheimer’s disease brains and can mediate production of reactive oxygen species in response to beta-amyloid fibrils. Am J Pathol 160(1):101–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch PJ, Harding SM, White AR, Camakaris J, Bush AI, Masters CL (2008) Mechanisms of A beta mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40(2):181–198. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2007.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Le Y, Yazawa H, Gong W, Wang JM (2002a) Potential role of the formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) in inflammatory aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. J Leukoc Biol 72(4):628–635 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui YH, Le Y, Gong W, Proost P, Van Damme J, Murphy WJ, Wang JM (2002b) Bacterial lipopolysaccharide selectively up-regulates the function of the chemotactic peptide receptor formyl peptide receptor 2 in murine microglial cells. J Immunol 168(1):434–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui YH, Le Y, Zhang X, Gong W, Abe K, Sun R, Van Damme J, Proost P, Wang JM (2002c) Up-regulation of FPR2, a chemotactic receptor for amyloid beta 1-42 (A beta 42), in murine microglial cells by TNF alpha. Neurobiol Dis 10(3):366–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R, Singh I, Sagare AP, Bell RD, Ross NT, LaRue B, Love R, Perry S, Paquette N, Deane RJ, Thiyagarajan M, Zarcone T, Fritz G, Friedman AE, Miller BL, Zlokovic BV (2012) A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest 122(4):1377–1392. doi:10.1172/JCI58642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker Y, McBean G, Godson C (2009) Lipoxin A4 inhibits IL-1beta-induced IL-8 and ICAM-1 expression in 1321N1 human astrocytoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296(6):C1420–C1427. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury J, Hickman SE, Thomas CA, Cao L, Silverstein SC, Loike JD (1996) Scavenger receptor-mediated adhesion of microglia to beta-amyloid fibrils. Nature 382(6593):716–719. doi:10.1038/382716a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury JB, Moore KJ, Means TK, Leung J, Terada K, Toft M, Freeman MW, Luster AD (2003) CD36 mediates the innate host response to beta-amyloid. J Exp Med 197(12):1657–1666. doi:10.1084/jem.20021546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elomaa O, Kangas M, Sahlberg C, Tuukkanen J, Sormunen R, Liakka A, Thesleff I, Kraal G, Tryggvason K (1995) Cloning of a novel bacteria-binding receptor structurally related to scavenger receptors and expressed in a subset of macrophages. Cell 80(4):603–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshourbagy NA, Li X, Terrett J, Vanhorn S, Gross MS, Adamou JE, Anderson KM, Webb CL, Lysko PG (2000) Molecular characterization of a human scavenger receptor, human MARCO. Eur J Biochem 267(3):919–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Lue LF, Yan S, Xu H, Luddy JS, Chen D, Walker DG, Stern DM, Schmidt AM, Chen JX, Yan SS (2010) RAGE-dependent signaling in microglia contributes to neuroinflammation, Abeta accumulation, and impaired learning/memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J 24(4):1043–1055. doi:10.1096/fj.09-139634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender K, Walter S, Kuhl S, Landmann R, Ishii K, Bertsch T, Stalder AK, Muehlhauser F, Liu Y, Ulmer AJ, Rivest S, Lentschat A, Gulbins E, Jucker M, Staufenbiel M, Brechtel K, Walter J, Multhaup G, Penke B, Adachi Y, Hartmann T, Beyreuther K (2004) The LPS receptor (CD14) links innate immunity with Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J 18(1):203–205. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0364fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala M, Liu PT, Espinosa-Jeffrey A, Rosenthal MJ, Bernard G, Ringman JM, Sayre J, Zhang L, Zaghi J, Dejbakhsh S, Chiang B, Hui J, Mahanian M, Baghaee A, Hong P, Cashman J (2007) Innate immunity and transcription of MGAT-III and Toll-like receptors in Alzheimer’s disease patients are improved by bisdemethoxycurcumin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(31):12849–12854. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701267104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel D, Wilkinson K, Zhao L, Hickman SE, Means TK, Puckett L, Farfara D, Kingery ND, Weiner HL, El Khoury J (2013) Scara1 deficiency impairs clearance of soluble amyloid-beta by mononuclear phagocytes and accelerates Alzheimer’s-like disease progression. Nat Commun 4:2030. doi:10.1038/ncomms3030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I, Konda Y, Yang YK, Miller DE, Dierick HA, Yamada T (1996) Molecular cloning of a novel receptor (CMKLR1) with homology to the chemotactic factor receptors. Cytogenet Cell Genet 74(4):286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granucci F, Petralia F, Urbano M, Citterio S, Di Tota F, Santambrogio L, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P (2003) The scavenger receptor MARCO mediates cytoskeleton rearrangements in dendritic cells and microglia. Blood 102(8):2940–2947. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-12-3651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grathwohl SA, Kalin RE, Bolmont T, Prokop S, Winkelmann G, Kaeser SA, Odenthal J, Radde R, Eldh T, Gandy S, Aguzzi A, Staufenbiel M, Mathews PM, Wolburg H, Heppner FL, Jucker M (2009) Formation and maintenance of Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid plaques in the absence of microglia. Nat Neurosci 12(11):1361–1363. doi:10.1038/nn.2432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot-Sestier MV, Town T (2013) Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease: a complex affair. CNS Neurol Disord: Drug Targets 12(5):593–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297(5580):353–356. doi:10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, El Khoury J (2010) Mechanisms of mononuclear phagocyte recruitment in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord: Drug Targets 9(2):168–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J (2008) Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci 28(33):8354–8360. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda M, Akiyama H, Yamada Y, Kondo H, Kawabe Y, Takeya M, Takahashi K, Suzuki H, Doi T, Sakamoto A, Ookawara S, Mato M, Gough PJ, Greaves DR, Gordon S, Kodama T, Matsushita M (1998) Immunohistochemical evidence for a macrophage scavenger receptor in Mato cells and reactive microglia of ischemia and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 245(3):734–740. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.8120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FL, Shiao YJ, Hou SJ, Yang CN, Chen YJ, Lin CH, Shie FS, Tsay HJ (2013) Cysteine-rich domain of scavenger receptor AI modulates the efficacy of surface targeting and mediates oligomeric Abeta internalization. J Biomed Sci 20:54. doi:10.1186/1423-0127-20-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DA, Fraser IP, Gordon S (1995) Murine macrophage scavenger receptor: in vivo expression and function as receptor for macrophage adhesion in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs. Eur J Immunol 25(2):466–473. doi:10.1002/eji.1830250224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husemann J, Silverstein SC (2001) Expression of scavenger receptor class B, type I, by astrocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells in normal adult mouse and human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am J Pathol 158(3):825–832. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husemann J, Loike JD, Kodama T, Silverstein SC (2001) Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) mediates adhesion of neonatal murine microglia to fibrillar beta-amyloid. J Neuroimmunol 114(1–2):142–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren P, Chen K, Hu J, Zhang X, Gong W, Wang JM (2005) IL-4 inhibits the expression of mouse formyl peptide receptor 2, a receptor for amyloid beta1-42, TNF-alpha-activated microglia. J Immunol 175(9):6100–6106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren P, Chen K, Gong W, Cho EH, Lockett S, Uranchimeg B, Wang JM (2007) Interleukin 10 and TNFalpha synergistically enhance the expression of the G protein-coupled formylpeptide receptor 2 in microglia. Neurobiol Dis 27(1):90–98. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana M, Palencia CA, Pahan K (2008) Fibrillar amyloid-beta peptides activate microglia via TLR2: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Immunol 181(10):7254–7262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JJ, Kim HD, Maxwell JA, Li L, Fukuchi K (2008) Toll-like receptor 4-dependent upregulation of cytokines in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 5:23. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-5-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RS, Minogue AM, Connor TJ, Lynch MA (2013) Amyloid-beta-induced astrocytic phagocytosis is mediated by CD36, CD47 and RAGE. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 8(1):301–311. doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9427-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B (2011) The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10(9):698–712. doi:10.1038/nrd3505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara K, Suenobu M, Yoshida A, Koga K, Hyodo A, Ohtsuka H, Kuniyasu A, Tamamaki N, Sugimoto Y, Nakayama H (2012) Intracerebral microinjection of interleukin-4/interleukin-13 reduces beta-amyloid accumulation in the ipsilateral side and improves cognitive deficits in young amyloid precursor protein 23 mice. Neuroscience 207:243–260. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian T (2006) Toll-like receptors in central nervous system glial inflammation and homeostasis. J Neurosci Res 83(5):711–730. doi:10.1002/jnr.20767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Vidal GS, Djurisic M, William CM, Birnbaum ME, Garcia KC, Hyman BT, Shatz CJ (2013) Human LilrB2 is a beta-amyloid receptor and its murine homolog PirB regulates synaptic plasticity in an Alzheimer’s model. Science 341(6152):1399–1404. doi:10.1126/science.1242077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsknecht J, Landreth G (2004) Microglial phagocytosis of fibrillar beta-amyloid through a beta1 integrin-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci 24(44):9838–9846. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2557-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Landreth GE (2005) Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid and IgGs are differentially regulated by proinflammatory cytokines. J Neurosci 25(36):8240–8249. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1808-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouadir M, Yang L, Tu J, Yin X, Zhou X, Zhao D (2011) Comparison of mRNA expression patterns of class B scavenger receptors in BV2 microglia upon exposure to amyloidogenic fragments of beta-amyloid and prion proteins. DNA Cell Biol 30(11):893–897. doi:10.1089/dna.2011.1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger M (1997) The other side of scavenger receptors: pattern recognition for host defense. Curr Opin Lipidol 8(5):275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreth GE, Reed-Geaghan EG (2009) Toll-like receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 336:137–153. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-00549-7_8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Y, Gong W, Tiffany HL, Tumanov A, Nedospasov S, Shen W, Dunlop NM, Gao JL, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM (2001) Amyloid (beta)42 activates a G-protein-coupled chemoattractant receptor, FPR-like-1. J Neurosci 21(2):RC123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HN, Surh YJ (2013) Resolvin D1-mediated NOX2 inactivation rescues macrophages undertaking efferocytosis from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol 86(6):759–769. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Han SB, Nam SY, Oh KW, Hong JT (2010) Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Pharm Res 33(10):1539–1556. doi:10.1007/s12272-010-1006-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letiembre M, Liu Y, Walter S, Hao W, Pfander T, Wrede A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Fassbender K (2009) Screening of innate immune receptors in neurodegenerative diseases: a similar pattern. Neurobiol Aging 30(5):759–768. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Walter S, Stagi M, Cherny D, Letiembre M, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Heine H, Penke B, Neumann H, Fassbender K (2005) LPS receptor (CD14): a receptor for phagocytosis of Alzheimer’s amyloid peptide. Brain 128(Pt 8):1778–1789. doi:10.1093/brain/awh531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Liu Y, Hao W, Wolf L, Kiliaan AJ, Penke B, Rube CE, Walter J, Heneka MT, Hartmann T, Menger MD, Fassbender K (2012) TLR2 is a primary receptor for Alzheimer’s amyloid beta peptide to trigger neuroinflammatory activation. J Immunol 188(3):1098–1107. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorton D, Schaller J, Lala A, De Nardin E (2000) Chemotactic-like receptors and Abeta peptide induced responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 21(3):463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue LF, Walker DG, Brachova L, Beach TG, Rogers J, Schmidt AM, Stern DM, Yan SD (2001) Involvement of microglial receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) in Alzheimer’s disease: identification of a cellular activation mechanism. Exp Neurol 171(1):29–45. doi:10.1006/exnr.2001.7732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CY, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Landreth GE (2009) Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J Neurosci 29(13):4252–4262. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DR, Bamberger ME, Combs CK, Landreth GE (1998) beta-Amyloid fibrils activate parallel mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in microglia and THP1 monocytes. J Neurosci 18(12):4451–4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Tago H, McGeer EG (1987) Reactive microglia in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type are positive for the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR. Neurosci Lett 79(1–2):195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methner A, Hermey G, Schinke B, Hermans-Borgmeyer I (1997) A novel G protein-coupled receptor with homology to neuropeptide and chemoattractant receptors expressed during bone development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 233(2):336–342. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud JP, Halle M, Lampron A, Theriault P, Prefontaine P, Filali M, Tribout-Jover P, Lanteigne AM, Jodoin R, Cluff C, Brichard V, Palmantier R, Pilorget A, Larocque D, Rivest S (2013) Toll-like receptor 4 stimulation with the detoxified ligand monophosphoryl lipid A improves Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(5):1941–1946. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215165110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mildner A, Schlevogt B, Kierdorf K, Bottcher C, Erny D, Kummer MP, Quinn M, Bruck W, Bechmann I, Heneka MT, Priller J, Prinz M (2011) Distinct and non-redundant roles of microglia and myeloid subsets in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 31(31):11159–11171. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6209-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L, Ajmone-Cat MA, De Berardinis MA, De Simone R (2005) Microglial activation in chronic neurodegenerative diseases: roles of apoptotic neurons and chronic stimulation. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 48(2):251–256. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KJ, El Khoury J, Medeiros LA, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD, Freeman MW (2002) A CD36-initiated signaling cascade mediates inflammatory effects of beta-amyloid. J Biol Chem 277(49):47373–47379. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208788200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales I, Guzman-Martinez L, Cerda-Troncoso C, Farias GA, Maccioni RB (2014) Neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. A rational framework for the search of novel therapeutic approaches. Front Cell Neurosci 8:112. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder SD, Veerhuis R, Blankenstein MA, Nielsen HM (2012) The effect of amyloid associated proteins on the expression of genes involved in amyloid-beta clearance by adult human astrocytes. Exp Neurol 233(1):373–379. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Origlia N, Bonadonna C, Rosellini A, Leznik E, Arancio O, Yan SS, Domenici L (2010) Microglial receptor for advanced glycation end product-dependent signal pathway drives beta-amyloid-induced synaptic depression and long-term depression impairment in entorhinal cortex. J Neurosci 30(34):11414–11425. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2127-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XD, Zhu YG, Lin N, Zhang J, Ye QY, Huang HP, Chen XC (2011) Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid is attenuated by oligomeric beta-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 6:45. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-6-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paresce DM, Ghosh RN, Maxfield FR (1996) Microglial cells internalize aggregates of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta-protein via a scavenger receptor. Neuron 17(3):553–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Yu Y, Liu J, Li S, He H, Cheng N, Ye RD (2014) The Chemerin Receptor CMKLR1 is a Functional Receptor for Amyloid-beta Peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. doi:10.3233/JAD-141227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez A, Wright MB, Maugeais C, Braendli-Baiocco A, Okamoto H, Takahashi A, Singer T, Mueller L, Niesor EJ (2010) MARCO, a macrophage scavenger receptor highly expressed in rodents, mediates dalcetrapib-induced uptake of lipids by rat and mouse macrophages. Toxicol In Vitro 24(3):745–750. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM (2010) Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 362(4):329–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed-Geaghan EG, Savage JC, Hise AG, Landreth GE (2009) CD14 and toll-like receptors 2 and 4 are required for fibrillar A{beta}-stimulated microglial activation. J Neurosci 29(38):11982–11992. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3158-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed-Geaghan EG, Reed QW, Cramer PE, Landreth GE (2010) Deletion of CD14 attenuates Alzheimer’s disease pathology by influencing the brain’s inflammatory milieu. J Neurosci 30(46):15369–15373. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2637-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regland B, Gottfries CG (1992) The role of amyloid beta-protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 340(8817):467–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert F, Rotshenker S (2003) Complement-receptor-3 and scavenger-receptor-AI/II mediated myelin phagocytosis in microglia and macrophages. Neurobiol Dis 12(1):65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter E, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lefkowitz RJ (2012) Molecular mechanism of beta-arrestin-biased agonism at seven-transmembrane receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 52:179–197. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard KL, Filali M, Prefontaine P, Rivest S (2008) Toll-like receptor 2 acts as a natural innate immune receptor to clear amyloid beta 1-42 and delay the cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 28(22):5784–5793. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1146-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J, Hogg N, Ren Y, Haslett C (1992) Thrombospondin cooperates with CD36 and the vitronectin receptor in macrophage recognition of neutrophils undergoing apoptosis. J Clin Invest 90(4):1513–1522. doi:10.1172/JCI116019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N, Feldman H, Giacobini E, Jones R, Mantua V, Mecocci P, Pani L, Winblad B, Kivipelto M (2014) Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med 275(3):251–283. doi:10.1111/joim.12191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M, Kipnis J, Rivest S, Prat A (2013) How do immune cells support and shape the brain in health, disease, and aging? J Neurosci 33(45):17587–17596. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3241-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbie LA, Hill SJ (1998) G protein-coupled-receptor cross-talk: the fine-tuning of multiple receptor-signalling pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci 19(3):87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ (2001) Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev 81(2):741–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell LC (2000) Alzheimer’s amyloid fibrils: structure and assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta 1502(1):16–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard AR, Soulet D, Gowing G, Julien JP, Rivest S (2006) Bone marrow-derived microglia play a critical role in restricting senile plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 49(4):489–502. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slowik A, Merres J, Elfgen A, Jansen S, Mohr F, Wruck CJ, Pufe T, Brandenburg LO (2012) Involvement of formyl peptide receptors in receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)—and amyloid beta 1-42-induced signal transduction in glial cells. Mol Neurodegener 7:55. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-7-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Jin J, Lim JE, Kou J, Pattanayak A, Rehman JA, Kim HD, Tahara K, Lalonde R, Fukuchi K (2011) TLR4 mutation reduces microglial activation, increases Abeta deposits and exacerbates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 8:92. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-8-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, Rayner KJ, Boyer L, Zhong R, Frazier WA, Lacy-Hulbert A, El Khoury J, Golenbock DT, Moore KJ (2010) CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol 11(2):155–161. doi:10.1038/ni.1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ, Walter SA, Pennell NA (1999) Reactive microgliosis. Prog Neurobiol 57(6):563–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvaranta S, Alanne-Kinnunen M, Oorni K, Oksjoki R, Kupari M, Kovanen PT, Helske-Suihko S (2014) Potential pathological roles for oxidized low-density lipoprotein and scavenger receptors SR-AI, CD36, and LOX-1 in aortic valve stenosis. Atherosclerosis 235(2):398–407. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.05.933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara K, Kim HD, Jin JJ, Maxwell JA, Li L, Fukuchi K (2006) Role of toll-like receptor signalling in Abeta uptake and clearance. Brain 129(Pt 11):3006–3019. doi:10.1093/brain/awl249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata K, Kitamura Y, Yanagisawa D, Morikawa S, Morita M, Inubushi T, Tsuchiya D, Chishiro S, Saeki M, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S, Tooyama I (2007) Microglial transplantation increases amyloid-beta clearance in Alzheimer model rats. FEBS Lett 581(3):475–478. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanopoulou K, Fragkouli A, Stylianopoulou F, Georgopoulos S (2010) Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) regulates perivascular macrophages and modifies amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(48):20816–20821. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005888107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, De Strooper B (2011) The role of G protein-coupled receptors in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 12(2):73–87. doi:10.1038/nrn2977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinakaran G, Koo EH (2008) Amyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing, and function. J Biol Chem 283(44):29615–29619. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800019200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany HL, Lavigne MC, Cui YH, Wang JM, Leto TL, Gao JL, Murphy PM (2001) Amyloid-beta induces chemotaxis and oxidant stress by acting at formylpeptide receptor 2, a G protein-coupled receptor expressed in phagocytes and brain. J Biol Chem 276(26):23645–23652. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101031200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyn JH, Ahlijanian MK (2014) Interpreting Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials in light of the effects on amyloid-beta. Alzheimers Res Ther 6(2):14. doi:10.1186/alzrt244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuppo EE, Arias HR (2005) The role of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37(2):289–305. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udan ML, Ajit D, Crouse NR, Nichols MR (2008) Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 mediate Abeta(1-42) activation of the innate immune response in a human monocytic cell line. J Neurochem 104(2):524–533. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich JD, Finn MB, Wang Y, Shen A, Mahan TE, Jiang H, Stewart FR, Piccio L, Colonna M, Holtzman DM (2014) Altered microglial response to Abeta plaques in APPPS1-21 mice heterozygous for TREM2. Mol Neurodegener 9:20. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-9-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier Y, Penke B (2004) Binding sites of amyloid beta-peptide in cell plasma membrane and implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Protein Pept Sci 5(1):19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodopivec I, Galichet A, Knobloch M, Bierhaus A, Heizmann CW, Nitsch RM (2009) RAGE does not affect amyloid pathology in transgenic ArcAbeta mice. Neurodegener Dis 6(5–6):270–280. doi:10.1159/000261723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmar P, Kullmann JS, Thilo B, Claussen MC, Rothhammer V, Jacobi H, Sellner J, Nessler S, Korn T, Hemmer B (2010) Active immunization with amyloid-beta 1-42 impairs memory performance through TLR2/4-dependent activation of the innate immune system. J Immunol 185(10):6338–6347. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S, Letiembre M, Liu Y, Heine H, Penke B, Hao W, Bode B, Manietta N, Walter J, Schulz-Schuffer W, Fassbender K (2007) Role of the toll-like receptor 4 in neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Physiol Biochem 20(6):947–956. doi:10.1159/000110455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Wang ZY, Xie JW, Cai JH, Wang T, Xu Y, Wang X, An L (2014) CD36 upregulation mediated by intranasal LV-NRF2 treatment mitigates hypoxia-induced progression of Alzheimer’s-like pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. doi:10.1089/ars.2014.5845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson K, El Khoury J (2012) Microglial scavenger receptors and their roles in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012:489456. doi:10.1155/2012/489456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson B, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Grommes C, Lee CY, Landreth G (2006) Fibrillar beta-amyloid-stimulated intracellular signaling cascades require Vav for induction of respiratory burst and phagocytosis in monocytes and microglia. J Biol Chem 281(30):20842–20850. doi:10.1074/jbc.M600627200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittamer V, Franssen JD, Vulcano M, Mirjolet JF, Le Poul E, Migeotte I, Brezillon S, Tyldesley R, Blanpain C, Detheux M, Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Vassart G, Parmentier M, Communi D (2003) Specific recruitment of antigen-presenting cells by chemerin, a novel processed ligand from human inflammatory fluids. J Exp Med 198(7):977–985. doi:10.1084/jem.20030382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittamer V, Gregoire F, Robberecht P, Vassart G, Communi D, Parmentier M (2004) The C-terminal nonapeptide of mature chemerin activates the chemerin receptor with low nanomolar potency. J Biol Chem 279(11):9956–9962. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313016200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Ueno M, Kusaka T, Miki T, Nagai Y, Nakagawa T, Kanenishi K, Hosomi N, Sakamoto H (2013) CD36 expression in the brains of SAMP8. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 56(1):75–79. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2012.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T (2006) Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med 12(9):1005–1015. doi:10.1038/nm1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Lin C, Yan F, Yu GQ, Rohde M, McConlogue L, Masliah E, Mucke L (2001) TGF-beta1 promotes microglial amyloid-beta clearance and reduces plaque burden in transgenic mice. Nat Med 7(5):612–618. doi:10.1038/87945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Loike JD, Brionne TC, Lu E, Anankov R, Yan F, Silverstein SC, Husemann J (2003) Adult mouse astrocytes degrade amyloid-beta in vitro and in situ. Nat Med 9(4):453–457. doi:10.1038/nm838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka M, Ishikawa T, Griep A, Axt D, Kummer MP, Heneka MT (2012) PPARgamma/RXRalpha-induced and CD36-mediated microglial amyloid-beta phagocytosis results in cognitive improvement in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 mice. J Neurosci 32(48):17321–17331. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, Roher A, Slattery T, Zhao L, Nagashima M, Morser J, Migheli A, Nawroth P, Stern D, Schmidt AM (1996) RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 382(6593):685–691. doi:10.1038/382685a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CN, Shiao YJ, Shie FS, Guo BS, Chen PH, Cho CY, Chen YJ, Huang FL, Tsay HJ (2011) Mechanism mediating oligomeric Abeta clearance by naive primary microglia. Neurobiol Dis 42(3):221–230. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazawa H, Yu ZX, Le Takeda Y, Gong W, Ferrans VJ, Oppenheim JJ, Li CC, Wang JM (2001) Beta amyloid peptide (Abeta42) is internalized via the G-protein-coupled receptor FPRL1 and forms fibrillar aggregates in macrophages. FASEB J 15(13):2454–2462. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0251com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM (2009) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol Rev 61(2):119–161. doi:10.1124/pr.109.001578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Liu J, Li SQ, Peng L, Ye RD (2014) Serum amyloid a differentially activates microglia and astrocytes via the PI3 K pathway. J Alzheimers Dis 38(1):133–144. doi:10.3233/JAD-130818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Hou H, Rezai-Zadeh K, Giunta B, Ruscin A, Gemma C, Jin J, Dragicevic N, Bradshaw P, Rasool S, Glabe CG, Ehrhart J, Bickford P, Mori T, Obregon D, Town T, Tan J (2011) CD45 deficiency drives amyloid-beta peptide oligomers and neuronal loss in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci 31(4):1355–1365. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3268-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]