Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are recently described as a class of short non-coding RNAs, which play important roles in post-transcriptional gene regulation and involved in many physiological and pathological processes. MicroRNA-223 (miR-223) has been showed highly elevated in the injured spinal cord. However, the potential role and underlying mechanisms of miR-223 in spinal cord injury (SCI) were incompletely understood. In the present study, we observed the persistent high levels of miR-223 in the injured spinal cord at different time points (1, 3, 7, and 14 days) after SCI. Besides, inhibiting miR-223 by intrathecally injection with antagomir-223 significantly improved recovery in hindlimb motor function and attenuated cell apoptosis in spinal cord-injured rats. Additionally, antagomir-223 treatment markedly decreased the pro-apoptotic protein levels, including Bax and cleaved caspase-3, up-regulated the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein level, as well as the expression of GluR2. Moreover, inhibition of miR-223 promoted angiogenesis, as evidenced by the increased CD31 expression and microvascular density. Taken together, our results indicate that inhibition of miR-223 with antagomir-223 exerts protective role in functional recovery, angiogenesis, and anti-apoptosis during SCI. Thereby, miR-223 may be a promising target of therapy for SCI.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury (SCI), Antagomir-223, Apoptosis, Angiogenesis, Functional recovery

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe central nervous system disease that results in complete or incomplete loss of voluntary motor and sensory function and associated with high mortality (Hulsebosch 2002). Recent data revealed that the loss of function after SCI attributes to both the primary injury and the subsequent secondary injury, which includes cell apoptosis, excessive inflammatory response, reduced spinal cord blood flow, etc. (Dumont et al. 2001). To date, there is no effective treatment for functional recovery after SCI in clinical practice, despite various therapy strategies, such as methylprednisolone (Pereira et al. 2009) and cell transplantation (Ozdemir et al. 2012) have been applied to SCI. Thus, a novel efficacious therapy for SCI is urgently required.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are recognized as one class of non-protein-coding short RNAs (18–22 nucleotides) that widely distributed in animals, plants, and some viruses. They could regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by targeting mRNAs for cleavage, translational repression or mRNA degradation (Bartel 2004; Zhang and Farwell 2008). Recently, accumulating evidence indicates that miRNAs play crucial roles in a variety of human diseases, such as cancer, metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, virus infections, and traumatic neurological injuries (Liu et al. 2008; Yunta et al. 2012), which suggest that miRNAs can function as a novel biomarker for disease diagnostics and miRNA-related therapeutics development. Previous studies demonstrated that miRNA-223 is preferentially expressed in both human and murine hematopoietic system and thus involved in myeloid differentiation process (Chen et al. 2004). Besides, miRNA-223 could negatively regulate progenitor cell proliferation and granulocyte differentiation and activation (Johnnidis et al. 2008). In addition, it was reported that miRNA-223 was highly expressed and might regulate neutrophils in the early phase of secondary damage after SCI (Izumi et al. 2011). However, the potential role and underlying mechanisms of miRNA-223 in SCI still need further understanding.

In this study, we show that inhibition of miR-223 by antagomir-223 after SCI exerts protective role in functional recovery, angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis, and ameliorates the secondary injury during SCI.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The healthy adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (weighing 180–220 g) were provided by Experimental Animal Centre of China Medical University (Shenyang, China). Rats were housed in individual cages with 12 h light/dark cycle and provided with free water and standard rodent chow. All experiments and animal care were performed in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of China Medical University.

Establishment of SCI Model in Rats

A rat SCI model was established as previously described with slight modifications (Liu et al. 2004; Tysseling-Mattiace et al. 2008). In brief, rats were randomly assigned into two groups: the sham group and SCI group. Each group contained 12 rats. The rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 10 % chloral hydrate (30 mg/kg). After anesthetization, the rats were laid prostrate, and a dorsal laminectomy at thoracic vertebra level 8 (T8) was performed to expose the spinal cord. The spinal cord was then moderate contused by a modified Allen’s weight drop apparatus (5 mm in diameter, 30 g weight dropped from a vertical height of 5 cm) to produce SCI. Sham animals received a dorsal laminectomy only. Besides, the animals’ bladders were manually emptied twice a day until the mice were able to recover autonomic bladder function during this period.

Antagomir-223 treatment experiments: rats were randomly divided into two groups, SCI control group and antagomir-223 group. Antagomir-223 was a 2′-O-methyl (2′-OMe) modified antisense oligonucleotide and the sequence was 5′- GGGGUAUUUGACAAACUGACA-3′ (GenePharma, shanghai, China). Following SCI, 5 μl volume of antagomir-223 (0.5 nM) or negative control was injected intrathecally into the cord with the same concentration for 3 days. The dosage of antagomir-223 was based on the previous data (Hu et al. 2013). Rats were euthanized at different time points after injury, and the spinal cord tissues were collected for subsequent experiments. The functional recovery of hindlimb motor of rats in each group was monitored at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days post-injury.

Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) Assay

Locomotor function was measured at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after SCI using the BBB locomotor rating scale (Basso et al. 1995). It was performed by two separate observers who were blinded to the treatment. Numbers ranging from 0 (refers to no spontaneous movement) to 21 (refers to normal movement) were scored and recorded by observers according to group assignment.

Total RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from injured spinal cords was extracted using RNA simple total RNA kit (Tiangen biotech, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of total RNA were determined by spectrophotometric determination at 260/280 nm, and equal amounts of RNA from each sample were reverse-transcribed to cDNA for quantitative RT-PCR. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a BIONEER Exicycler TM 96 System (Bioneer, Korea). The primers were utilized as follows: miR-223, 5′-CGGTGCGTGTATTTGACAAGC-3′ (forward), 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTC-3′ (reverse); U6, 5′- CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA -3′ (forward), 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′ (reverse); GluR2, 5′- TGAGCGTTACGAGGGCTACTGT -3′ (forward), 5′-TGAAGGGCTTGGAGAAGTCAAT-3′ (reverse); and β-actin, 5′-GGAGATTACTGCCCTGGCTCCTAGC-3′ (forward), 5′-GGCCGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTT-3′ (reverse). The relative miRNA abundance was normalized to U6 expression, and the relative GluR2 levels were normalized to β-actin expression. Analysis of gene expression was performed by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

In Situ Hybridization

The expression of miR-223 in the spinal cord at day 1 and 3 post-injury was measured by in situ hybridization. The spinal cord sections were performed as described above. Briefly, paraffin-embedded spinal tissue was sliced into 5 μm sections. The sections were dewaxed to hydrate using graded alcohol. Sections were then incubated with 0.3 % H2O2 at room temperature for 15 min to exhaust endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing three times in DEPC-PBS, the slices were then blocked with hybridization buffer for 2 h at room temperature, followed by hybridization with 20 μl digoxigenin-labeled miR-223 probes (20 nM) at 52 °C overnight. The hybridized sections were washed in different concentrations of preheated saline sodium citrate (SCC) and again incubated with HRP-conjugated anti- digoxigenin antibody (PerkinElmer, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. Finally, after DAB staining, the hematoxylin was used for re-staining. Images of the stained sections were acquired by a light microscopy. The images acquired were analyzed by calculating integrated optical density (IOD) value according to previously described (Ge et al. 2014; Hu et al. 2013).

TUNEL Staining

The spinal cord paraffinic sections of 5 μm were prepared at 1 or 3 days after injection with antagomir-223 as described above. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining was performed to assess cell apoptosis in the spinal cord using in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the sections were rinsed three times with PBS, and then incubated with 3 % H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase for 15 min at room temperature. After wash again with PBS, the TUNEL reaction mixture was added to incubate for 60 min at 37 °C. Following washing with PBS, the sections were processed with POD for 30 min at 37 °C. The sections were then stained with DAB for 10 min and hematoxylin counterstain for 3 min before dehydration, hyalinization, and image acquisition. The number of positive cells in each section was counted with a light microscopy.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

For immunohistochemical analysis, the spinal cord paraffinic sections of 5 μm were prepared at 1 or 3 days after injection with miR-223 as described above. After dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols, the sections were treated with heat-induced epitope retrieval solution and put into a microwave irradiation for 10 min. Then the sections were cooled off, washed in PBS, and incubated with 3 % H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase for 15 min at room temperature. Following washing three times in PBS, the sections were blocked with goat serum (10 %) for 15 min and then incubated with diluted (1:100, in PBS) rabbit anti-GluR2 antibody at 4 °C overnight. After washed three times in PBS, the sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200, in PBS) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by staining with DAB for 10 min and hematoxylin reagent for 3 min before dehydration and hyalinization. Images of the stained sections were analyzed by a light microscopy.

Immunofluorescence Staining

The expression of CD31 was determined by immunofluorescence staining. Sections were performed as described above, and the sections were blocked with goat serum (10 %) for 15 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary CD31 antibody (1:50 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 °C overnight. After washed three times in PBS, the sections were incubated with Cy3-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200 diluted, Beyotime, Suzhou, China) for 60 min at 37 °C. After that, the sections were washed three times in PBS and counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to localize nuclear. After mounted onto glass slides, the stained sections were visualized under a light microscopy.

Western Blot Analysis

One-cm-long segments of spinal cord encompassing the injury site were harvested at 1 and 3 days post-injury, respectively. The samples were homogenized and total proteins from the homogenate were extracted by RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China), protein concentration was assayed using BCA protein assay kit and equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated by 8 % (for GluR2), and 14 % SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After that, the membrane was blocked with 5 % skim milk at room temperature for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies (cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax, 1:1,000 diluted, Wanleibio, Shenyang, China; GluR2, 1:500 diluted, Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology, Beijing, China) at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The targeted proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate, and analyzed by Image J software. The β-actin protein served as an internal control.

Microvascular Density Measurement

The microvascular density (MVD) was determined by IF staining of CD31 at 1 and 3 days post-injury as previously reported (Ge et al. 2014). CD31-positive cell clusters were marked as microvessels and each cluster of CD31-positive cells was counted as one microvessel. The mean value of microvessels in the spinal cord was calculated by two researchers who were blinded to the sample identity. The data then were converted into the number of microvessels/mm2 for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between the mean values of normally distributed data were assessed with a one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc corrections or the two-tailed Student’s t test. Results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Altered miR-223 Expression in the Injured Spinal Cord and Intrathecal Injection of Antagomir-223

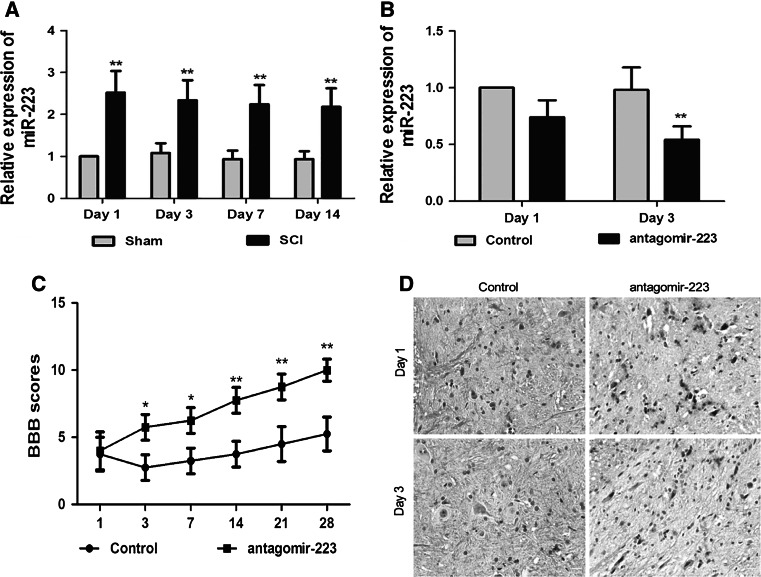

We detected the temporal expression of miR-223 in the spinal cord at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after SCI. qRT-PCR results revealed that the relative expression of miR-223 in the unimpaired spinal cord of sham rats did not significantly change from 1 to 14 days. Compared with the sham group, SCI caused a dramatic increase in miR-223 levels at day 1 after SCI (about 2.5 times of the sham), and the increase still maintained at day 14 post-injury (p < 0.01, Fig. 1). To investigate the role and function of miR-223 in SCI, we subsequently accessed the inhibitory effect of antagomir-223 on miR-223 expression. Quantitative RT-PCR results revealed that administration of antagomir-223 effectively reversed the increased miR-223 expression at 3 d after SCI (p < 0.01), and the relative expression of miR-223 was about 50 % of SCI group, but still higher than that of sham group (Fig. 1a, b). In situ hybridization analysis indicated that miR-223 was localized in the nuclei of several cells, and the number of miR-223 positive cells was decreased after antagomir-223 treatment compared with the SCI control group. These data indicate that SCI causes persistent up-regulation of miR-223, and the designed antagomir-223 can effectively down-regulate the miR-223 levels of SCI rats.

Fig. 1.

Altered miR-223 expression in the injured spinal cord and intrathecal injection of antagomir-223. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of miR-223 expression at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after SCI (a). Inhibitory effect of antagomir-223 on miR-223 expression was determined by qRT-PCR (b) and in situ hybridization, magnification ×400, scales bar 20 μm (d). Antagomir-223treatment promotes functional recovery following SCI (c). Hindlimb functional recovery was monitored at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after SCI using the BBB scores. The values are presented as mean ± SD. a **p < 0.01 significantly different from the Sham group; b, c *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 significantly different from the SCI control group

Inhibition of miR-223 Promoted Functional Recovery Following SCI

To assess the effect of silencing miR-223 on the functional recovery following SCI, hindlimb functional recovery was monitored at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after injury using the BBB score. As shown in Fig. 1c, SCI control group showed low scores, the mean score was 5.25 ± 1.14 points at 4 weeks after injury. However, the BBB score of antagomir-223 treatment group significantly increased at 3 days after SCI (p < 0.05) and gradually elevated during the experimental period compared to the SCI group (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01). Four weeks after injury, mean score was 10 ± 0.82 points, which indicates that antagomir-223 treatment can effectively improve the functional recovery of SCI rats.

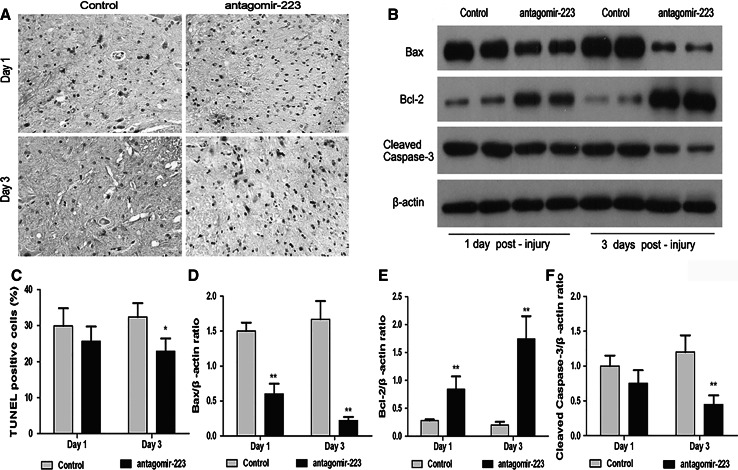

Administration of Antagomir-223 Reduced Cell Apoptosis and Regulated the Expression of Bcl-2, Bax, and Cleaved Caspase-3

The effect of antagomir-223 on apoptotic cells after SCI was detected using TUNEL staining. As shown in Fig. 2a and c, the number of TUNEL-positive cells in the antagomir-223 treatment group was significantly lower than that of SCI control group at 3 days post-injury (p < 0.05). Cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax have been reported to play important roles in regulating apoptotic response, we further examined whether inhibition of miR-223 affected these proteins expression in the injured spinal cord. Western blot results (Fig. 2b, d–f) revealed that the pro-apoptotic Bax and cleaved caspase-3 protein levels were markedly down-regulated after antagomir-223 treatment compared to those of the SCI control group (p < 0.01), whereas the anti-apoptotic protein of Bcl-2 levels was strikingly up-regulated in the antagomir-223 treatment group (p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Administration of antagomir-223 inhibits cell apoptosis and regulates the expression of Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved caspase-3. The effect of antagomir-223 on apoptotic cells was detected at 1 or 3 days after SCI using TUNEL staining, magnification ×400, scales bar 20 μm (a, c). The protein levels of Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved caspase-3 were analyzed by Western blot (b, d–f). The β-actin was performed as a control. The values are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 significantly different from the SCI control group

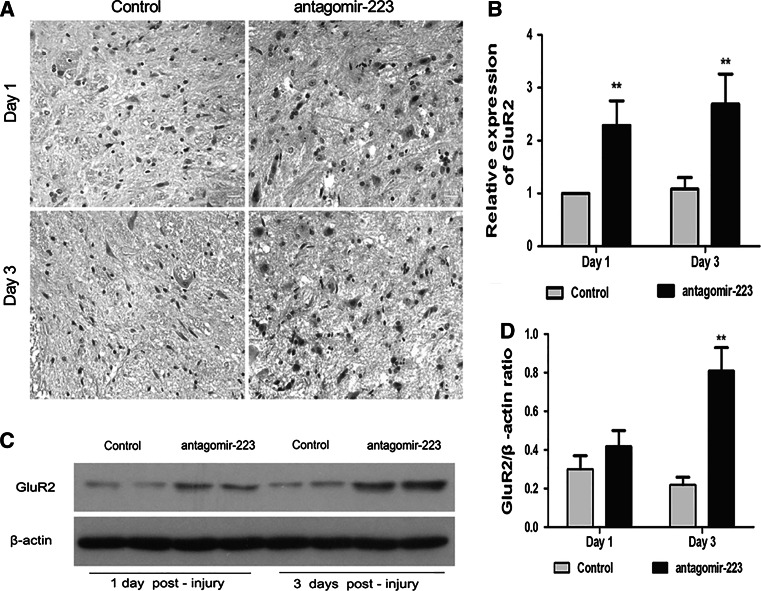

Antagomir-223 Up-Regulated GluR2 Expression in the Injured Spinal Cord of Rats

GluR2 has been reported as one target of mir-223, we further investigated the effects of miR-223 on the expression of GluR2 in the injured spinal cord. Immunohistochemical staining showed that (Fig. 3a), GluR2 was localized in the cytoplasm of neurons. Antagomir-223 treatment group presented deeper and increased staining compared with the SCI control group. Western blot and qRT-PCR results further confirmed that low levels of GluR2 were expressed in the injured spinal cord; however, the levels were significantly elevated after antagomir-223 treatment at 3 days post-injury (p < 0.01, Fig. 3b–d).

Fig. 3.

Administration of antagomir-223 up-regulates GluR2 expression at 1 or 3 days after SCI. The effect of antagomir-223 on GluR2 expression was measured by immunohistochemical staining, magnification ×400, scales bar 20 μm (a), qRT-PCR (b), and Western blot (c, d). The β-actin was performed as a control. The values are presented as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 significantly different from the SCI control group

Antagomir-223 Promoted Angiogenesis After SCI

CD31 (also named PECAM-1) is a key endothelial cell adhesion molecule that plays an important role in the formation of new vessels (DeLisser et al. 1997). The effect of miR-223 inhibition on angiogenesis in vivo was accessed using CD31 immunofluorescence staining and MVD. The results (Fig. 4) showed that the MVD in the spinal cord was increased in the antagomir-223 group, and the CD31-positive blood vessels were markedly increased at day 3 post-injury compared with the SCI control group (p < 0.01). The results indicate that down-regulation of miR-223 level can promote angiogenesis after SCI.

Fig. 4.

Administration of antagomir-223 promotes angiogenesis at 1 day or 3 days after SCI. The effect of antagomir-223 on CD31 expression was evaluated by Immunofluorescence staining, magnification ×200, scales bar 50 μm (a). Quantitative analysis of CD31-positive cells in spinal cord tissue (b). The values are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 significantly different from the SCI control group

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that inhibition of miR-223 by intrathecally injection with antagomir-223 could effectively ameliorate the pathologic hallmarks of SCI, as evidenced by suppressing cell apoptosis, promoting angiogenesis and functional recovery, as well as regulating the expression of Bcl-2, Bax, cleaved caspase-3, and GluR2. These findings offer a new therapeutic target of miR-223 for therapy of SCI.

Previous studies have shown that MiR-223 was a highly conserved, myeloid-specific expression miR (Gilicze et al. 2014), and it exacerbated inflammatory response by regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activity (Bauernfeind et al. 2012). Moreover, it was highly expressed and regulated the neutrophils during SCI (Nakanishi et al. 2010; Izumi et al. 2011). These data indicate a negative role of high miR-223 expression in SCI. Consistent with these findings, we found that miR-223 was persistent and highly expressed in the injured spinal cord. To further reveal its function and underlying mechanism in SCI, we used the antagomir-223 to down-regulate the expression of miR-223. Interestingly, administration of antagomir-223 significantly improved the hindlimb motor function recovery, as indicated by the increased BBB scores in the antagomir-223 group. Additionally, we found that inhibition of miR-223 significantly increased the expression of CD31-positive blood vessels, which indicates that antagomir-223 promotes angiogenesis during SCI. Our results were in line with result reported that miR-223 antagonized angiogenesis and prevented endothelial cell proliferation in mice (Shi et al. 2013).

The pathophysiological mechanisms of SCI are complicated, a series of cellular and molecular events are involved in the process (Young 1993; Lu et al. 2000). Previous studies have shown that apoptosis, as an important event of secondary injury after SCI, can result in spinal cord tissues damage and loss of function (Li et al. 1996; Grossman et al. 2001). Apoptosis is regulated primarily by the upstream Bcl-2 family and the downstream caspase family (Cory and Adams 2002; Riedl and Shi 2004), among which the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, pro-apoptotic Bax, and caspase-3 are the most commonly used apoptotic markers (Reed 2006; Jarskog et al. 2004; Ola et al. 2011). In the present study, SCI-induced apoptotic cells and the expression of apoptosis-related markers, Bcl-2, Bax, and caspase-3 were assessed. The results showed that SCI induced a notable increase of apoptotic cells in the spinal tissues. In contrast, antagomir-223 treatment group showed less number of TUNEL positive cells at 3 days after trauma. Simultaneously, antagomir-223 significantly repressed the pro-apoptotic Bax and the cleaved caspase-3 levels; whereas the levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 were up-regulated by antagomir-223 treatment. The results indicate that inhibition of miR-223 plays an anti-apoptotic role in SCI. Our results were consistent with recent data (Kim et al. 2014).

GluR2 as an important subunit of glutamate receptors (GluRs) has been reported playing a critical role in regulating Ca2+ influx into neurons and inhibiting cell apoptosis (Van Damme et al. 2007; Ishiuchi et al. 2002; Ferguson et al. 2008; Brown et al. 2004). Previous data have shown the abnormal GluR2 expression during SCI, GluR2 protein levels were persistently reduced near the injury site (Grossman et al. 1999; Brown et al. 2004). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that GluR2 as one gene target of miR-223 was up-regulated in miR-223 knockdown mice (Harraz et al. 2012). Since miRNAs can regulate their target gene expression at the post-transcriptional levels, silencing of miRNA using antagomirs might result in the regulation of many mRNAs. Based on these evidences, we further investigated the effect of antagomir-223 on the expression of GluR2 in the injured spinal cord. Immunohistochemical staining showed that low GluR2 levels were present in the cytoplasm of neurons in SCI group, and the result was in line with previous data. Inhibition of miR-223 using antagomir-223 obviously increased the GluR2 expression both in mRNA and protein levels. Our results indicate that inhibition of miR-223 expression by antagomir-223 can lead to the regulation of target GluR2. Antagomir-223 exerts its protective role in many aspects during SCI.

Conclusion

Taken together, our study demonstrated that administration of antagomir-223 after SCI exerted beneficial role in angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis, and functional recovery during SCI. Thereby, miR-223 may be a promising target of therapy for SCI.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.: 81371552) and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (No.: 2013021054).

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116(2):281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC (1995) A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma 12(1):1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind F, Rieger A, Schildberg FA, Knolle PA, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hornung V (2012) NLRP3 inflammasome activity is negatively controlled by miR-223. J Immunol 189(8):4175–4181. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KM, Wrathall JR, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB (2004) Glutamate receptor subunit expression after spinal cord injury in young rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 152(1):61–68. doi:10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303(5654):83–86. doi:10.1126/science.1091903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S, Adams JM (2002) The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer 2(9):647–656. doi:10.1038/nrc883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisser HM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Robinson CS, Wexler RS, Kerr JS, Garlanda C, Merwin JR, Madri JA, Albelda SM (1997) Involvement of endothelial PECAM-1/CD31 in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 151(3):671–677 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont RJ, Okonkwo DO, Verma S, Hurlbert RJ, Boulos PT, Ellegala DB, Dumont AS (2001) Acute spinal cord injury, part I: pathophysiologic mechanisms. Clin Neuropharmacol 24(5):254–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AR, Christensen RN, Gensel JC, Miller BA, Sun F, Beattie EC, Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS (2008) Cell death after spinal cord injury is exacerbated by rapid TNF alpha-induced trafficking of GluR2-lacking AMPARs to the plasma membrane. J Neurosci 28(44):11391–11400. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3708-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XT, Lei P, Wang HC, Zhang AL, Han ZL, Chen X, Li SH, Jiang RC, Kang CS, Zhang JN (2014) miR-21 improves the neurological outcome after traumatic brain injury in rats. Sci Rep 4:6718. doi:10.1038/srep06718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilicze AB, Wiener Z, Toth S, Buzas E, Pallinger E, Falcone FH, Falus A (2014) Myeloid-derived microRNAs, miR-223, miR27a, and miR-652, are dominant players in myeloid regulation. BioMed Res Int 2014:870267. doi:10.1155/2014/870267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SD, Wolfe BB, Yasuda RP, Wrathall JR (1999) Alterations in AMPA receptor subunit expression after experimental spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurosci 19(14):5711–5720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SD, Rosenberg LJ, Wrathall JR (2001) Temporal-spatial pattern of acute neuronal and glial loss after spinal cord contusion. Exp Neurol 168(2):273–282. doi:10.1006/exnr.2001.7628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz MM, Eacker SM, Wang X, Dawson TM, Dawson VL (2012) MicroRNA-223 is neuroprotective by targeting glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(46):18962–18967. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121288109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JZ, Huang JH, Zeng L, Wang G, Cao M, Lu HB (2013) Anti-apoptotic effect of microRNA-21 after contusion spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 30(15):1349–1360. doi:10.1089/neu.2012.2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebosch CE (2002) Recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment of spinal cord injury. Adv Physiol Educ 26(1–4):238–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiuchi S, Tsuzuki K, Yoshida Y, Yamada N, Hagimura N, Okado H, Miwa A, Kurihara H, Nakazato Y, Tamura M, Sasaki T, Ozawa S (2002) Blockage of Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA receptors suppresses migration and induces apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. Nat Med 8(9):971–978. doi:10.1038/nm746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi B, Nakasa T, Tanaka N, Nakanishi K, Kamei N, Yamamoto R, Nakamae T, Ohta R, Fujioka Y, Yamasaki K, Ochi M (2011) MicroRNA-223 expression in neutrophils in the early phase of secondary damage after spinal cord injury. Neurosci Lett 492(2):114–118. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarskog LF, Selinger ES, Lieberman JA, Gilmore JH (2004) Apoptotic proteins in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia: high Bax/Bcl-2 ratio without caspase-3 activation. Am J Psychiatry 161(1):109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnnidis JB, Harris MH, Wheeler RT, Stehling-Sun S, Lam MH, Kirak O, Brummelkamp TR, Fleming MD, Camargo FD (2008) Regulation of progenitor cell proliferation and granulocyte function by microRNA-223. Nature 451(7182):1125–1129. doi:10.1038/nature06607 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim D, Song J, Ahn C, Kang Y, Chun CH, Jin EJ (2014) Peroxisomal dysfunction is associated with up-regulation of apoptotic cell death via miR-223 induction in knee osteoarthritis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Bone 64:124–131. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GL, Brodin G, Farooque M, Funa K, Holtz A, Wang WL, Olsson Y (1996) Apoptosis and expression of Bcl-2 after compression trauma to rat spinal cord. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 55(3):280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Han S, Lu PH, Xu XM (2004) Upregulation of annexins I, II, and V after traumatic spinal cord injury in adult rats. J Neurosci Res 77(3):391–401. doi:10.1002/jnr.20167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Sall A, Yang D (2008) MicroRNA: an emerging therapeutic target and intervention tool. Int J Mol Sci 9(6):978–999. doi:10.3390/ijms9060978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Ashwell KW, Waite P (2000) Advances in secondary spinal cord injury: role of apoptosis. Spine 25(14):1859–1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Nakasa T, Tanaka N, Ishikawa M, Yamada K, Yamasaki K, Kamei N, Izumi B, Adachi N, Miyaki S, Asahara H, Ochi M (2010) Responses of microRNAs 124a and 223 following spinal cord injury in mice. Spinal cord 48(3):192–196. doi:10.1038/sc.2009.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ola MS, Nawaz M, Ahsan H (2011) Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem 351(1–2):41–58. doi:10.1007/s11010-010-0709-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir M, Attar A, Kuzu I (2012) Regenerative treatment in spinal cord injury. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 7(5):364–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira JE, Costa LM, Cabrita AM, Couto PA, Filipe VM, Magalhaes LG, Fornaro M, Di Scipio F, Geuna S, Mauricio AC, Varejao AS (2009) Methylprednisolone fails to improve functional and histological outcome following spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol 220(1):71–81. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC (2006) Proapoptotic multidomain Bcl-2/Bax-family proteins: mechanisms, physiological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ 13(8):1378–1386. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl SJ, Shi Y (2004) Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5(11):897–907. doi:10.1038/nrm1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Fisslthaler B, Zippel N, Fromel T, Hu J, Elgheznawy A, Heide H, Popp R, Fleming I (2013) MicroRNA-223 antagonizes angiogenesis by targeting beta1 integrin and preventing growth factor signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res 113(12):1320–1330. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tysseling-Mattiace VM, Sahni V, Niece KL, Birch D, Czeisler C, Fehlings MG, Stupp SI, Kessler JA (2008) Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit glial scar formation and promote axon elongation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 28(14):3814–3823. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Bogaert E, Dewil M, Hersmus N, Kiraly D, Scheveneels W, Bockx I, Braeken D, Verpoorten N, Verhoeven K, Timmerman V, Herijgers P, Callewaert G, Carmeliet P, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W (2007) Astrocytes regulate GluR2 expression in motor neurons and their vulnerability to excitotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(37):14825–14830. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705046104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W (1993) Secondary injury mechanisms in acute spinal cord injury. J Emerg Med 11(Suppl 1):13–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunta M, Nieto-Diaz M, Esteban FJ, Caballero-Lopez M, Navarro-Ruiz R, Reigada D, Pita-Thomas DW, del Aguila A, Munoz-Galdeano T, Maza RM (2012) MicroRNA dysregulation in the spinal cord following traumatic injury. PLoS One 7(4):e34534. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Farwell MA (2008) microRNAs: a new emerging class of players for disease diagnostics and gene therapy. J Cell Mol Med 12(1):3–21. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00196.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]