Abstract

BACKGROUND

Obesity is a key factor in the development and progression of both heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and atrial fibrillation (AF). In the STEP-HFpEF Program (comprising the STEP-HFpEF [Research Study to Investigate How Well Semaglutide Works in People Living With Heart Failure and Obesity] and STEP-HFpEF DM [Research Study to Look at How Well Semaglutide Works in People Living With Heart Failure, Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes] trials), once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg improved HF-related symptoms, physical limitations, and exercise function and reduced body weight in patients with obesity-related HFpEF. Whether the effects of semaglutide in this patient group differ in participants with and without AF (and across various AF types) has not been fully examined.

OBJECTIVES

The goals of this study were: 1) to evaluate baseline characteristics and clinical features of patients with obesity-related HFpEF with and without a history of AF; and 2) to determine if the efficacy of semaglutide across all key trial outcomes are influenced by baseline history of AF (and AF types) in the STEP-HFpEF Program.

METHODS

This was a secondary analysis of pooled data from the STEP-HFpEF and STEP-HFpEF DM trials. Patients with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction ≥45%, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire–Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) <90 points were randomized 1:1 to receive once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg or matching placebo for 52 weeks. Dual primary endpoints (change in KCCQ-CSS and percent change in body weight), confirmatory secondary endpoints (change in 6-minute walk distance; hierarchical composite endpoint comprising all-cause death, HF events, thresholds of change in KCCQ-CSS, and 6-minute walk distance; and C-reactive protein [CRP]), and exploratory endpoint (change in N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]) were examined according to investigator-reported history of AF (yes/no). Responder analyses examined the proportions of patients who experienced a ≥5-, ≥10, ≥15, and ≥20-point improvement in KCCQ-CSS per history of AF.

RESULTS

Of the 1,145 participants, 518 (45%) had a history of AF (40% paroxysmal, 24% persistent AF, and 35% permanent AF) and 627 (55%) did not. Participants with (vs without) AF were older, more often male, had higher NT-proBNP levels, included a higher proportion of those with NYHA functional class III symptoms, and used more antithrombotic therapies, beta-blockers, and diuretics. Semaglutide led to larger improvements in KCCQ-CSS (11.5 points [95% CI: 8.3–14.8] vs 4.3 points [95% CI: 1.3–7.2]; P interaction = 0.001) and the hierarchal composite endpoint (win ratio of 2.25 [95% CI: 1.79–2.83] vs 1.30 [95% CI: 1.06–1.59]; P interaction < 0.001) in participants with AF vs without AF, respectively. The proportions of patients receiving semaglutide vs those receiving placebo experiencing ≥5-, ≥10-, ≥15-, and ≥20-point improvement in KCCQ-CSS were also higher in those with (vs without) AF (all P interaction values <0.05). Semaglutide consistently reduced CRP, NT-proBNP, and body weight regardless of AF status (all P interaction values not significant). There were fewer serious adverse events and serious cardiac disorders in participants treated with semaglutide vs placebo irrespective of AF history.

CONCLUSIONS

In the STEP-HFpEF Program, AF was observed in nearly one-half of patients with obesity-related HFpEF and was associated with several features of more advanced HF. Treatment with semaglutide led to significant improvements in HF-related symptoms, physical limitations, and exercise function, as well as reductions in weight, CRP, and NT-proBNP in people with and without AF and across AF types. The magnitude of semaglutide-mediated improvements in HF-related symptoms and physical limitations was more pronounced in those with AF vs without AF at baseline.(Research Study to Investigate How Well Semaglutide Works in People Living With Heart Failure and Obesity [STEP-HFpEF; NCT04788511; Research Study to Look at How Well Semaglutide Works in People Living With Heart Failure, Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes [STEP-HFpEF DM; NCT04916470])

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, KCCQ-CSS, obesity, patient-reported outcomes, semaglutide

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is commonly observed in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and is associated with worse outcomes compared with those in sinus rhythm.1,2 Little is known about this relationship in the context of obesity-related HFpEF. This is of particular interest because overweight and obesity, through numerous mechanisms, contribute to the risk, progression, and severity of both AF and HFpEF.3–5

In the STEP-HFpEF Program (comprising the STEP-HFpEF [Research Study to Investigate How Well Semaglutide Works in People Living With Heart Failure and Obesity] and STEP-HFpEF DM [Research Study to Look at How Well Semaglutide Works in People Living With Heart Failure, Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes] trials), once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg improved HF-related symptoms, physical limitations, and exercise function, and reduced body weight and biomarkers of inflammation and congestion in individuals with obesity-related HFpEF.6–8 Nearly one-half of the patient population in the STEP-HFpEF Program had AF at baseline, and we previously showed that participants with AF (compared with those who did not have AF) experienced larger improvements in HF-related health status (per the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire–Clinical Summary Score [KCCQ-CSS]) but similar magnitude of reduction in body weight.6 However, several key aspects of the relationship between obesity-related HFpEF, presence of AF, and the effects of semaglutide in this patient population remain unexplored.

First, the details of how AF is related to the patient’s baseline characteristics in the context of obesity-related HFpEF has not been previously described. Second, it is not known whether the efficacy of semaglutide on all of the key trial outcomes (beyond changes in KCCQ-CSS and body weight) is influenced by presence of AF. Specifically, we have not previously reported the effects of semaglutide on confirmatory secondary endpoints such as 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), hierarchical composite endpoint, and C-reactive protein (CRP), or exploratory endpoints (N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]), and have not examined the proportion of participants with small, moderate, and large improvements in HF-related symptoms and physical limitations according to AF status. Finally, whether the relationship between presence of AF and the effects of semaglutide on the trial endpoints differ according to the type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent) is also unknown. Accordingly, we set out to evaluate the aforementioned objectives in the current analysis.

METHODS

STUDY AND PROGRAM DESIGN.

The design and primary results of the individual trials and the overall program have been published previously.6–8 The participants were recruited from 129 sites across 18 countries in Asia, Europe, North America, and South America. The Steering Committee, comprising academic members and representatives from the sponsor (Novo Nordisk), designed both trials and oversaw academic publications. A global expert panel provided input on academic, medical, and operational aspects in each country. Both trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocols for both trials were approved by the Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards at each site, and all participants signed written informed consent.

STUDY PROGRAM PARTICIPANTS AND RANDOMIZATION.

Eligible participants had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥45%, body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, NYHA functional class II to IV, KCCQ-CSS <90 points, 6MWD ≥100 m, and ≥1 of the following: elevated filling pressures, elevated natriuretic peptide levels (with thresholds stratified based on BMI) and echocardiographic abnormalities, or HF hospitalization in the previous 12 months plus ongoing requirement for diuretic therapy and/or echocardiographic abnormalities. They also had requirement for ongoing diuretic treatment and/or echocardiographic abnormalities. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to receive a once-weekly target dose of subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or matching placebo on top of standard of care for 52 weeks.

History of AF at baseline, as well as AF type (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), was reported by the investigators and not based on the presence of AF on an electrocardiogram.

EFFICACY AND SAFETY OUTCOMES.

Dual primary endpoints were change in KCCQ-CSS and percent change in body weight, both measured from baseline to 52 weeks. Confirmatory secondary endpoints were change in 6MWD from baseline to 52 weeks, a hierarchical composite endpoint analyzed using win ratio (comprising all-cause death, HF events, differences of ≥15, ≥10, and ≥5 points in KCCQ-CSS change, and a difference of ≥30 m in 6MWD change), and change in CRP from baseline to 52 weeks. Selected supportive secondary and exploratory endpoints included change in NT-proBNP from baseline to 52 weeks and improvements in KCCQ-CSS of ≥5, ≥10, ≥15, and ≥20 points. Safety endpoints included serious adverse events, including serious cardiac and gastrointestinal disorders, evaluated within the AF subgroups.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES.

Analyses were prespecified in the academic Statistical Analysis Plan (unless stated otherwise). Patients were stratified according to history of AF and AF subtypes (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), as reported by the investigators. Baseline characteristics were evaluated according to AF status. Continuous variables were compared by using the Wilcoxon test, and categorical variables were compared by using the chi-square test. The effects of semaglutide vs placebo were examined using the full analysis set (all randomized participants according to the intention-to-treat principle while in-trial regardless of treatment discontinuation).

Analyses of continuous endpoints were performed by using analysis of covariance models, adjusted for the baseline value of the relevant continuous outcome variable, with treatment, trial, and BMI (<35 kg/m2 or ≥35 kg/m2) as fixed factors using 1,000 imputations; analyses also included an interaction term between treatment and AF subgroup. NT-proBNP and CRP were log-transformed before analyses. Estimates were then combined by using Rubin’s rule. For the analyses of change in KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD, missing observations at week 52 caused by cardiovascular death or previous HF events were single imputed to the lowest observed value across both treatment arms and visits. Missing values caused by other reasons were multiple imputed from retrieved participants in the same randomized treatment arm. For other endpoints, missing observations at week 52 were multiple imputed irrespective of death or prior HF events using the same imputation method. Interaction P values were derived from an F-test of equality between the treatment differences across the 2 subgroups (any AF vs no AF), as well as across the 4 subgroups accounting for AF types (permanent vs persistent vs paroxysmal vs no AF).

Analyses of the hierarchical composite endpoint (win ratio) were performed stratified according to AF status, based on direct comparisons of each participant randomized to receive semaglutide vs each participant randomized to receive placebo. For each of the participant pairs, a “treatment winner” based on similar observation time was declared based on the endpoint hierarchy. The win ratio (ie, the proportion of winners randomized to semaglutide divided by the winners randomized to placebo) was estimated independently according to AF status (using 1,000 imputations as described in the previous text). Test for equality for the win ratio was performed using Cochran’s Q test.

For the responder analyses, we examined the proportions of participants according to AF status who experienced a ≥5-, ≥10-, ≥15-, and ≥20-point improvement in KCCQ-CSS (corresponding to at least small, at least moderate, large, and very large improvements) in patients receiving semaglutide and those receiving placebo. Missing data were imputed following an approach similar to that used for analysis of continuous KCCQ-CSS. Logistic regression models were then used to calculate the ORs and corresponding 95% CIs for semaglutide effects on the likelihood of ≥5-, ≥10, ≥15, and ≥20-point improvement in KCCQ-CSS, with 1,000 multiple imputations, adjusted for the baseline KCCQ-CSS, trial, and BMI group (the stratification factor). Estimates were then again combined using Rubin’s rule.

In post hoc analyses, we also constructed the cumulative response curves according to AF status that plotted observed changes in KCCQ-CSS scores between baseline and week 52 against the cumulative proportions of participants in the semaglutide and placebo groups experiencing those changes (eg, ≥20-point improvement; ≥10-point worsening). Finally, post hoc sensitivity analyses were performed of the dual primary, confirmatory secondary, select supportive secondary, and exploratory endpoints, in which the models were additionally adjusted for baseline LVEF, NYHA functional class (II vs III-IV), NT-proBNP, and diuretic use (yes/no).

Safety endpoints according to AF status were analyzed by using the full analysis set (all randomized participants) using in-trial data.

No adjustment for multiple testing was performed, given the exploratory nature of the analyses. A 2-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant. Results are presented as estimated changes from baseline to week 52 for continuous endpoints, a win ratio (for the hierarchical composite endpoint), or an OR (for responder analyses) with a 95% CI and a 2-sided P value. Because NT-proBNP and CRP were log-transformed, treatment ratios with the corresponding 95% CIs at week 52 are reported. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.4, SAS/STAT version 15.1 (SAS Institute, Inc).

RESULTS

Of the 1,145 participants, 518 (45%) had a history of AF and 627 (55%) did not (Table 1). In those with AF, 40% had paroxysmal AF, 24% had persistent AF, and 35% had permanent AF (1% of participants were missing AF type). Participants with AF were older (72.0 years [Q1-Q3: 65–76 years] vs 67 years [Q1-Q3: 60–73 years]), were more often male, had higher NT-proBNP levels (882.1 pg/mL [Q1-Q3: 410.2–1,340.4 pg/mL] vs 304.0 pg/mL [Q1-Q3: 181.0–575.9 pg/mL]), and included a higher proportion of those with NYHA functional class III symptoms compared with people without AF. BMI, LVEF, blood pressure, history of HF hospitalization or coronary artery disease, KCCQ-CSS, and 6MWD were similar between groups. Use of antithrombotic therapies, beta-blockers, and diuretics (including mineralocorticoid receptorantagonists)were higherin those with AF.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Pooled STEP-HFpEF and STEP-HFpEF DM Participants Stratified According to History of AF (N = 1,145)

| Patients With AFa (n = 518) |

Patients Without AF (n = 627) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | <0.0001 | ||

| STEP-HFpEF | 275 (53.1) | 254 (40.5) | |

| STEP-HFpEF DM | 243 (46.9) | 373 (59.5) | |

| Sex | 0.0002 | ||

| Female | 227 (43.8) | 343 (54.7) | |

| Male | 291 (56.2) | 284 (45.3) | |

| Age, y | 72.0 (65.0–76.0) | 67.0 (60.0–73.0) | <0.0001 |

| Raceb | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 498 (96.1) | 528 (84.2) | |

| Asian | 10 (1.9) | 66 (10.5) | |

| Black/African American | 8 (1.5) | 31 (4.9) | |

| Other | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Ethnicityb | <0.0001 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 17 (3.3) | 95 (15.2) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 501 (96.7) | 532 (84.8) | |

| Body weight, kg | 106.2 (94.7–122.4) | 101.0 (89.6–116.0) | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 37.1 (33.8–41.5) | 36.8 (33.5–41.2) | 0.2999 |

| BMI stratification | 0.5369 | ||

| 30 to <35 kg/m2 | 176 (34.0) | 224 (35.7) | |

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 342 (66.0) | 403 (64.3) | |

| Waist circumference, cm | 120.7 (112.3–130.8) | 119.0 (110.0–128.0) | 0.0049 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 133.0 (122.0–144.0) | 133.0 (124.0–144.0) | 0.4657 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 78.0 (71.0–86.0) | 78.0 (70.0–84.0) | 0.0671 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 70.0 (61.0–81.0) | 70.0 (63.0–78.0) | 0.2968 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 882.1 (410.2–1340.4) | 304.0 (181.0–575.9) | <0.0001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.4 (1.8–7.0) | 3.7 (1.8–9.0) | 0.1743 |

| LVEF, % | 55.0 (50.0–60.0) | 58.0 (52.0–60.0) | 0.0014 |

| LVEF stratification | 0.0132 | ||

| ≥45 to <50%c | 100 (19.3) | 91 (14.5) | |

| ≥50 to <60% | 223 (43.1) | 251 (40.0) | |

| ≥60% | 195 (37.6) | 285 (45.5) | |

| KCCQ-CSS, points | 59.4 (44.3–74.0) | 58.3 (41.7–70.8) | 0.0384 |

| 6MWD, m | 298.0 (221.8–378.1) | 290.0 (220.0–360.0) | 0.2973 |

| HF hospitalization within prior 1 y | 82 (15.8) | 111 (17.7) | 0.3996 |

| Comorbidities at screening | |||

| Hypertension | 438 (84.6) | 521 (83.1) | 0.5046 |

| Coronary artery disease | 108 (20.8) | 138 (22.0) | 0.6344 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 57 (11.0) | 62 (9.9) | 0.5383 |

| NYHA functional class | 0.1029 | ||

| II | 343 (66.2) | 442 (70.5) | |

| III-IV | 175 (33.8) | 185 (29.5) | |

| Concomitant medications | |||

| Antithrombotic medications | 469 (90.5) | 91 (14.5) | <0.0001 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 349 (67.4) | 458 (73.0) | 0.0363 |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 65 (12.5) | 342 (54.5) | <0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers | 446 (86.1) | 482 (76.9) | <0.0001 |

| Diuretics | 444 (85.7) | 481 (76.7) | 0.0001 |

| Loop diuretics | 355 (68.5) | 347 (55.3) | <0.0001 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 199 (38.4) | 185 (29.5) | 0.0015 |

| Thiazides | 62 (12.0) | 113 (18.0) | 0.0046 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB (ARNI) | 412 (79.5) | 487 (77.7) | 0.4445 |

| ARNI | 27 (5.2) | 31 (4.9) | 0.8369 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 90 (17.4) | 131 (20.9) | 0.1334 |

Values are n (%) or median (Q1-Q3) and are from the full analysis set. Percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding. Continuous variables used the Wilcoxon test, and binary variables used a Pearson chi-square test. A total of 1,146 patients were randomized to treatment; however, 1 patient was randomized in error such that the full analysis set comprises 1,145 patients.

Permanent AF: 179 (15.6%); persistent AF: 124 (10.8%); paroxysmal AF: 208 (18.2%); unknown AF: 7 (0.6%).

Race and ethnic group were reported by the investigator.

Includes 1 patient with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 33%.

6WMD = 6-minute walk distance; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; AF = atrial fibrillation; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARNI = angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; BMI = body mass index; CRP = C-reactive protein; HF = heart failure; KCCQ-CSS = Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Clinical Summary Score; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; SGLT2 = sodium-glucose cotransporter 2.

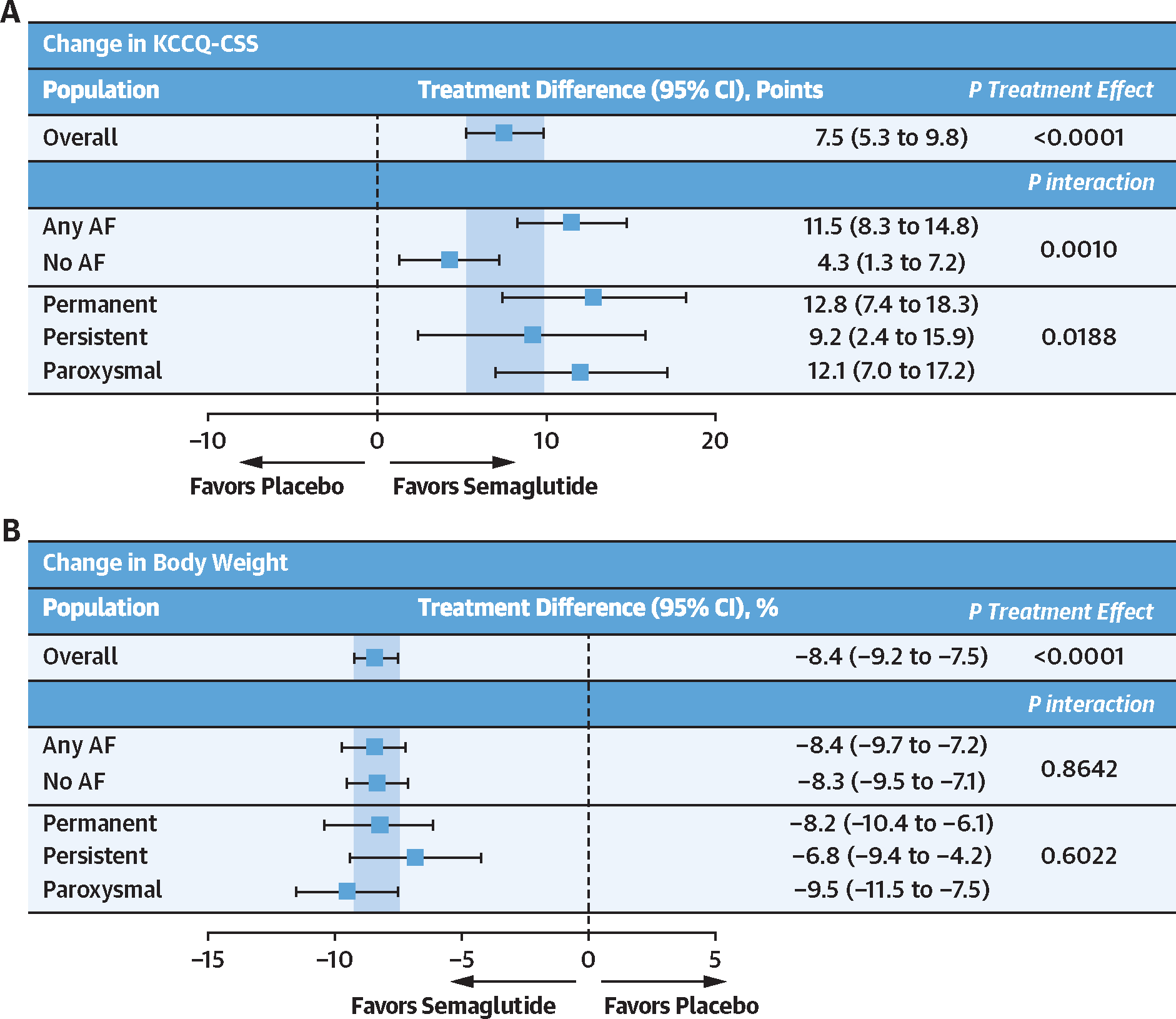

Semaglutide vs placebo led to a larger increase in KCCQ-CSS in those with AF and AF subtypes compared with patients who did not have AF (Figure 1). Semaglutide consistently reduced body weight compared with placebo, regardless of AF status or type.

FIGURE 1. Effects of Semaglutide vs Placebo on the Dual Primary Endpoints According to History of AF at Baseline.

Effects of semaglutide vs placebo on change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) (A) and (B) change in body weight according to history of atrial fibrillation (AF) (and AF subtype) at baseline. Analyses were performed by using an analysis of covariance model, with study, randomized treatment, body mass index strata (<35 kg/m2 vs ≥35 kg/m2), subgroup, and treatment by subgroup interaction as factors and baseline endpoint value as a covariate. Missing observations due to reasons other than cardiovascular death or previous heart failure events were multiple imputed (×1,000) from retrieved participants from the same treatment arm. Missing observations due to cardiovascular death of previous heart failure events were imputed by using a composite strategy with the least favorable value determined during the trial. P values for interaction were derived from an F test of equality between the treatment differences across the 2 subgroups.

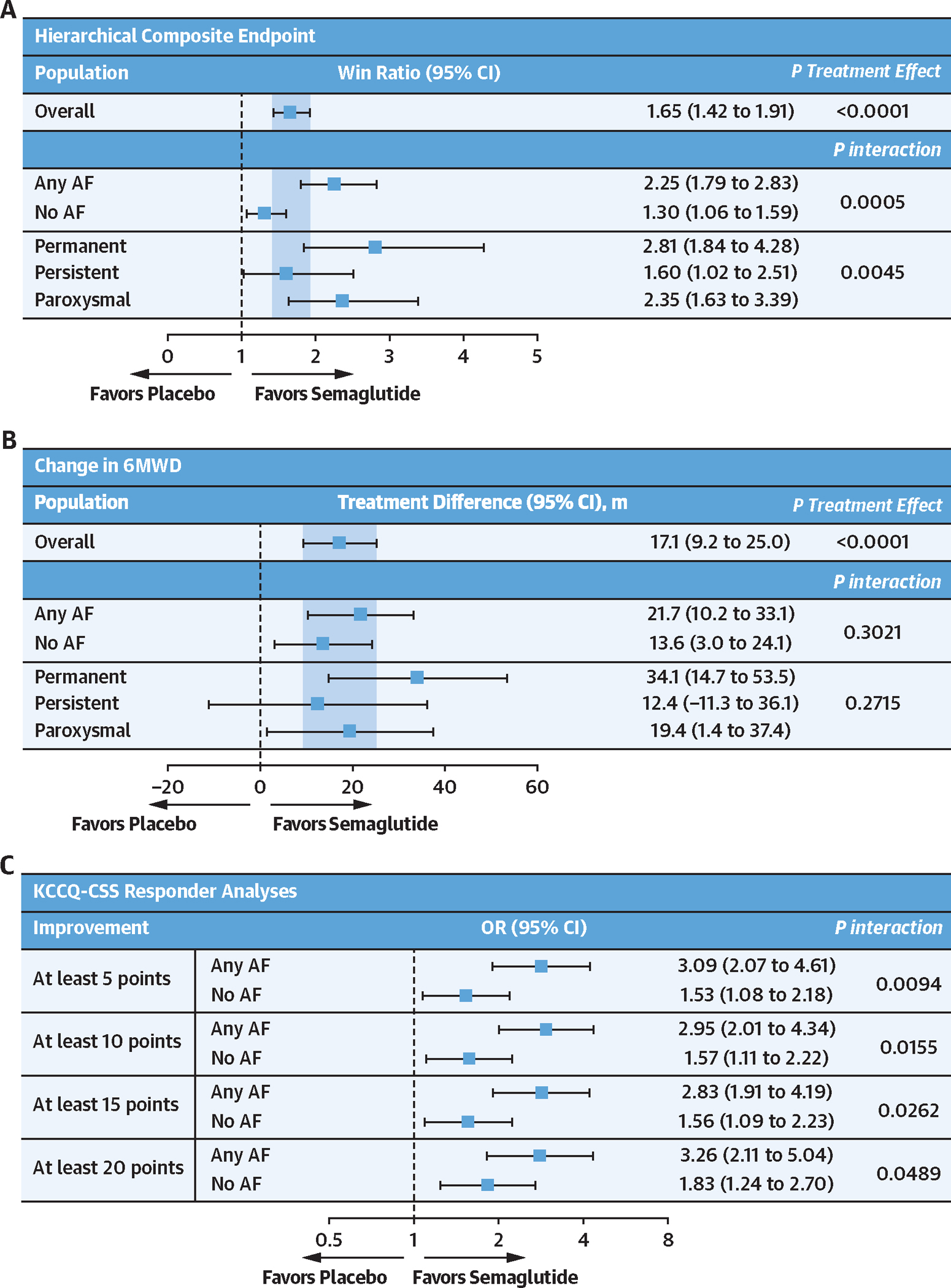

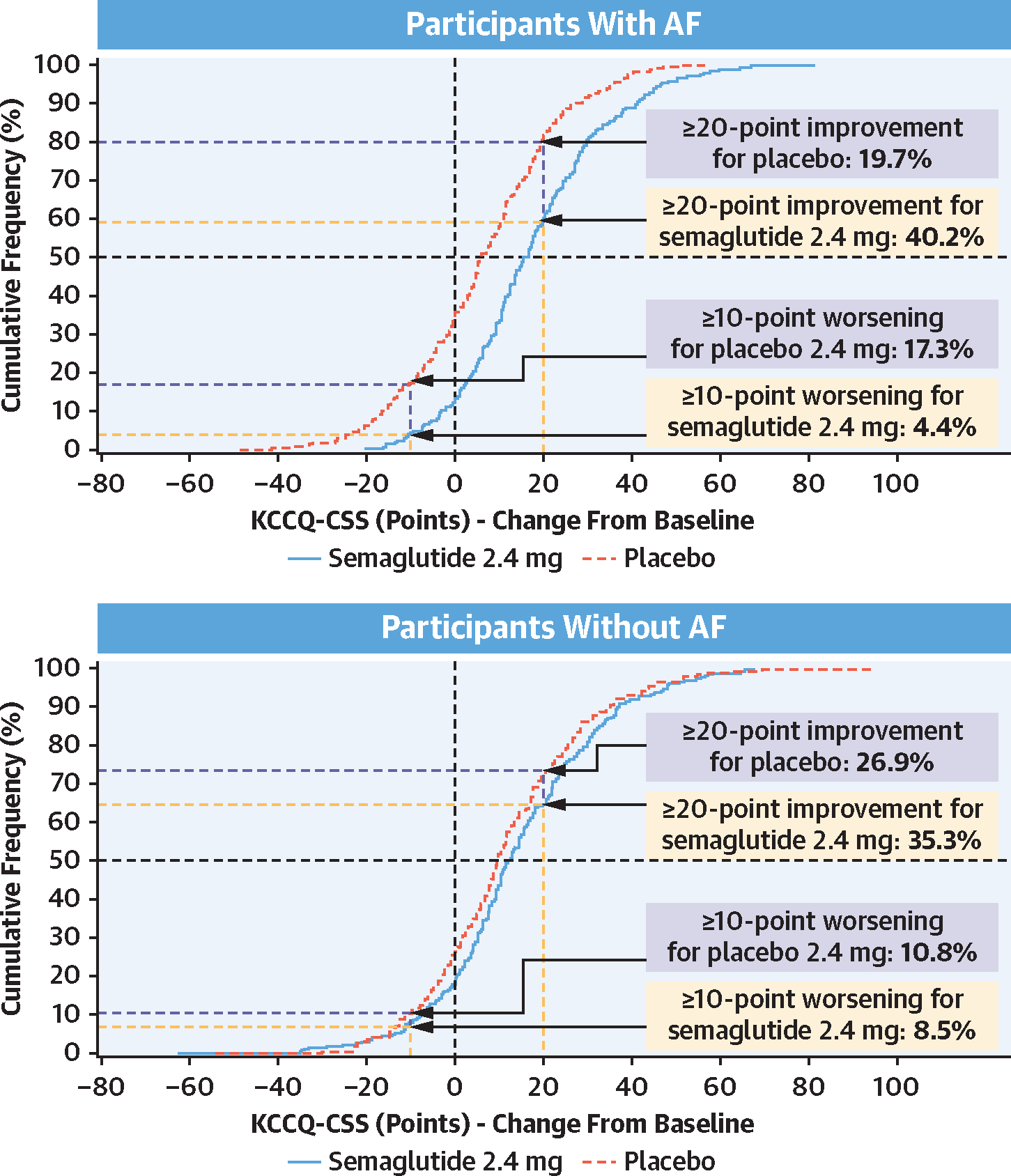

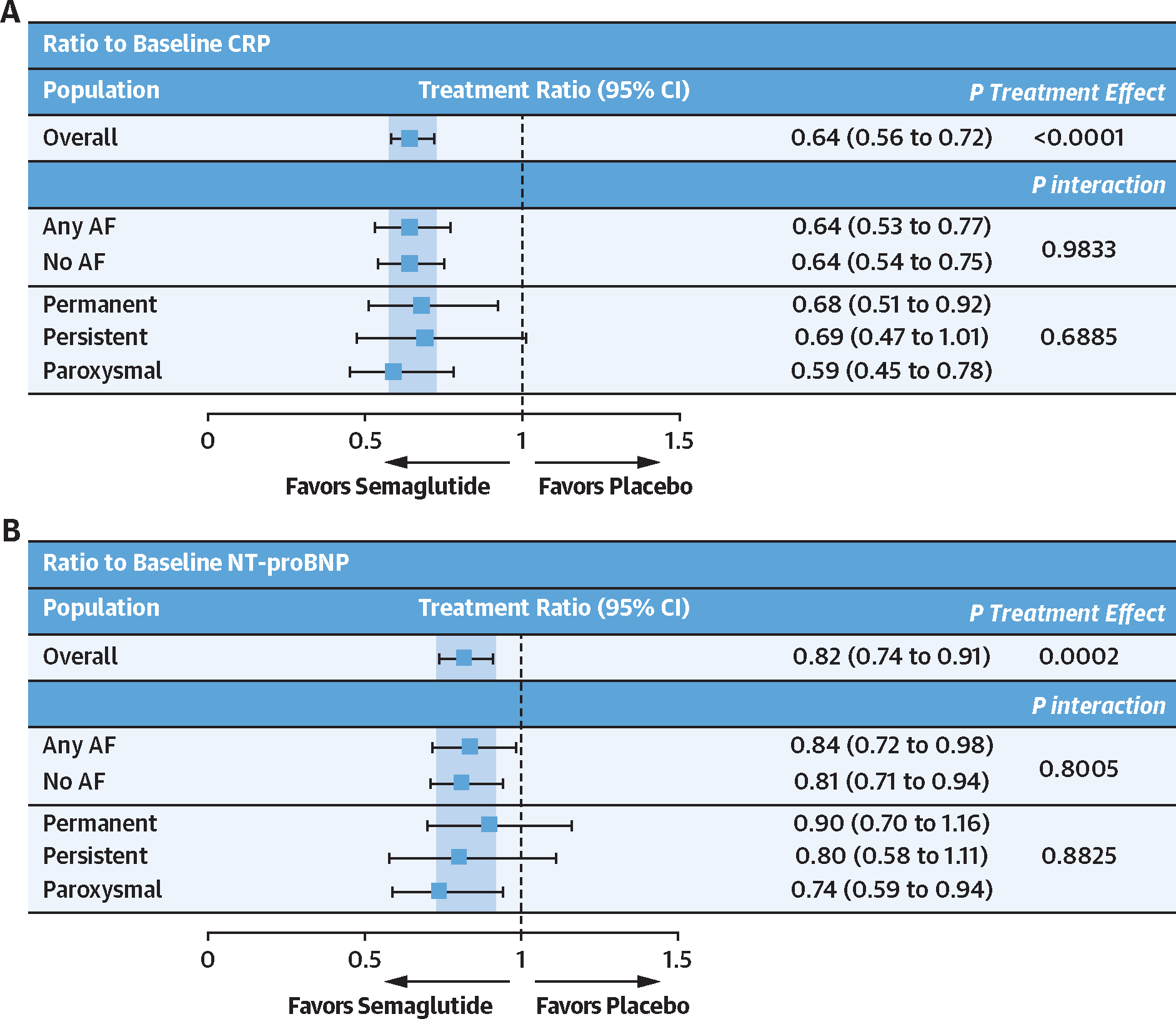

Semaglutide (vs placebo) also led to a larger improvement in the hierarchal composite endpoint (win ratio) among those with (vs without) AF (Figure 2) and improved 6MWD consistently across the AF subgroups. Furthermore, in responder analyses, the proportion of semaglutide-treated patients experiencing ≥5-, ≥10-, ≥15-, and ≥20-point improvements in KCCQ-CSS was higher in those with (vs without) AF. Cumulative response analyses showed continuous separation of KCCQ-CSS in favor of semaglutide vs placebo among participants both with and without AF. There was greater improvement and less deterioration in KCCQ-CSS in semaglutide-treated patients vs those receiving placebo; however, the magnitude of these semaglutide-mediated effects seemed more pronounced in participants with AF vs without AF (Figure 3). Semaglutide consistently reduced CRP and NT-proBNP regardless of the presence or absence of AF (all P interaction > 0.05) (Figure 4). Sensitivity analyses of the dual primary, confirmatory secondary, select supportive secondary, and exploratory endpoints that were additionally adjusted for baseline LVEF, NYHA functional class, NT-proBNP, and diuretic use produced results that were similar to the main analyses (Supplemental Table 1).

FIGURE 2. Effects of Semaglutide vs Placebo on the Hierarchical Composite Endpoint, 6MWD, and KCCQ-CSS (Responder Analyses) According to History of AF at Baseline.

Effects of semaglutide vs placebo on hierarchical composite endpoint (A), change in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) (B), and KCCQ-CSS responder analyses (C) according to history of AF at baseline. Analyses were performed by using an analysis of covariance model, with study, randomized treatment, body mass index strata (<35 kg/m2 vs ≥35 kg/m2), subgroup, and treatment by subgroup interaction as factors, and baseline endpoint as a covariate. Responder analyses at week 52 were performed by using a binary logistic regression model with study, body mass index strata, randomized treatment, subgroup, and treatment by subgroup interaction as factors, and baseline KCCQ-CSS as a covariate. P values for interaction were derived from an F test of equality between the treatment differences across the 2 subgroups. For the win ratio, the test for equality of the AF groups was performed using a Cochran’s Q test. Other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

FIGURE 3. Cumulative Incidence Curves of Change in KCCQ-CSS With Semaglutide vs Placebo From Baseline to Week 52 in Participants With and Without AF.

Plots show observed data from the in-trial period for the full analysis set. To interpret this graph, select a change in KCCQ-CSS on the x-axis and find the corresponding proportion of patients receiving semaglutide 2.4 mg and placebo who achieved that degree of improvement or worsening on the y-axis. For example, in participants with AF, note that the vertical line arising from 20-point improvement intersects with the semaglutide and placebo curves at 59.8% and 80.3%, respectively. Therefore, 40.2% and 19.7% in the semaglutide and placebo groups achieved a ≥20-point improvement, respectively. Other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

FIGURE 4. Effects of Semaglutide vs Placebo on Ratio to Baseline for CRP and NT-proBNP According to History of AF at Baseline.

Effects of semaglutide vs placebo on the ratio to baseline for C-reactive protein (CRP) (A) and ratio to baseline for N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) (B) according to history of AF at baseline. Analyses were performed by using an analysis of covariance model, with randomized treatment, body mass index strata (<35 kg/m2 vs ≥35 kg/m2), subgroup, and treatment by subgroup interaction as factors, and baseline endpoint as a covariate. CRP and NT-proBNP values were log-transformed. P values for interaction were derived from an F test of equality between the treatment differences across the 2 subgroups. AF = atrial fibrillation.

There were fewer serious adverse events and serious cardiac disorders in participants receiving semaglutide vs placebo irrespective of AF history (Supplemental Table 2). Serious gastrointestinal adverse events also occurred at similar rates in those with AF (3.6% of semaglutide-treated participants vs 1.9% of participants receiving placebo) and without AF (2.2% of semaglutide-treated participants vs 2.3% of participants receiving placebo). In participants without AF at baseline, new AF was reported as a serious adverse event in 0.9% (3 of 321) of semaglutide-treated patients and 1.6% (5 of 306) of patients receiving placebo.

DISCUSSION

Although the prevalence and clinical impact of AF in people with HFpEF are well recognized,1,2,9 there are few data exploring this relationship in the context of obesity-related HFpEF. In the STEP-HFpEF Program, we found that the prevalence of AF in people with obesity-related HFpEF was 45%, slightly lower than what has been observed in contemporary HFpEF trials, such as those of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (56% in the DELIVER [Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure] and 52% in the EMPEROR-Preserved [Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction] trials),1,2 or in prior heart failure registries.10 Although obesity is a well-recognized risk factor for the development of left atrial myopathy and AF,11 it is noteworthy that the prevalence of AF was comparable (and not higher) in the setting of obesity-related HFpEF vs the broader HFpEF patient populations. This is consistent with subgroup analyses from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial according to baseline BMI, which revealed no significant step-up in the prevalence of AF with increasing BMI.12 People with obesity-related HFpEF and concomitant AF were older, more frequently male, and had several features consistent with more advanced heart failure (approximately 3-fold higher NT-proBNP, a higher proportion with NYHA functional class III symptoms, and greater use of diuretics), which is generally consistent with what has been described in contemporary HFpEF trials.2 Of interest, we did not find higher BMI in people with AF, nor did we observe meaningful differences in baseline KCCQ-CSS or 6MWD between AF subgroups. These observations vary from previous HFpEF trials, which found greater prevalence of obesity, worse exercise capacity, and lower peak oxygen consumption in patients with AF vs without AF.13,14 The aforementioned differences may be related to the fact that the baseline BMI was considerably higher, and KCCQ and 6MWD considerably lower, in the STEP-HFpEF Program vs other HFpEF trials. Collectively, these data highlight important baseline differences in people with AF and obesity-related HFpEF relative to other HFpEF populations.

Prior analyses from STEP-HFpEF Program showed that in obesity-related HFpEF, semaglutide 2.4 mg produced large improvements in heart failure–related symptoms and physical limitations both in patients with and without AF, although the magnitude of benefit was nearly 3-fold greater in those with (vs without) AF despite a similar magnitude of weight loss in these participant groups.6 The findings of this study expand on these initial observations in several ways. First, the responder (and cumulative response curve) analyses confirm that the likelihood of clinically meaningful improvements in KCCQ-CSS in patients receiving semaglutide vs those receiving placebo was consistently higher among those with (vs without) a history of AF. This larger improvement in KCCQ-CSS was also likely responsible for the more favorable hierarchical composite endpoint results (ie, higher win ratio) in participants with vs without AF. Second, we found that semaglutide effects on all other key trial outcomes, including improvement in exercise function (evaluated by 6MWD), and reductions in CRP and NT-proBNP were observed consistently regardless of AF history. Third, the effects of semaglutide on the wide spectrum of trial outcomes remained consistent when comparing participants across the types of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent) with those who did not have a history of AF. Finally, semaglutide was well tolerated, with fewer serious adverse events and cardiac disorders than placebo across AF subgroups. Collectively, these findings are clinically relevant and highlight a favorable benefit-risk balance for semaglutide in patients with obesity-related HFpEF regardless of AF status; those who have AF derive an even greater benefit.

Although the mechanism(s) responsible for the greater improvement in patient-reported symptoms and physical limitations with semaglutide among participants with vs without AF remain unclear, these do not seem to be due to baseline differences in KCCQ-CSS, nor are they related to greater reductions in weight, NT-proBNP, or CRP. Another possible explanation could be more favorable effects on cardiac remodeling, specifically left atrial remodeling, in those with AF. Indeed, the AF-predominant phenotype of HFpEF is known to be associated with significant left atrial remodeling, reduced left atrial compliance and reservoir strain, and increased venous congestion.9 Although it could be hypothesized that semaglutide may lead to a greater reduction in left atrial remodeling in those with AF vs without AF, in the echocardiographic substudy from the STEP-HFpEF Program, we found similar semaglutide-mediated improvements in left atrial remodeling in patients with and without a history of AF.15 Furthermore, there was no significant relationship between the change in left atrial volume and change in KCCQ-CSS postrandomization with semaglutide vs placebo.

The most likely explanation is that presence of AF simply identifies patients with features of more advanced HF. Although the degree of reduction in NT-proBNP observed in the current study was similar across AF subgroups, it is possible (and likely) that similar reductions in natriuretic peptides (which are a surrogate for decongestion) may translate to an even more favorable effect on HF-related symptoms and physical limitations in patients who have greater magnitude of congestion and hemodynamic impairment at baseline. In this regard, the findings of this study are in line with prior analyses from the STEP-HFpEF Program, which showed greater semaglutide-mediated improvement in KCCQ-CSS in participants with other features of more advanced HF, such as higher (vs lower) NT-proBNP levels16 and NYHA functional class,17 and in those requiring (vs not requiring) loop diuretics.18 However, it is also possible that this observation is a chance finding; accordingly, it will require further validation in future trials.

The observation of greater semaglutide-mediated improvement in KCCQ-CSS despite similar weight reduction in those with AF vs without AF suggests that the benefits of semaglutide in HFpEF seem to be mediated, in part, via direct (and likely non-weight loss related) effects on HF pathobiology. This adds another line of evidence to a number of prior observations from the STEP-HFpEF Program, including semaglutide’s robust effects on reducing NT-proBNP (despite substantial concomitant weight loss),16 as well as marked reductions in loop diuretic requirements in patients receiving semaglutide vs those receiving placebo.18 Furthermore, the echocardiographic substudy from the STEP-HFpEF Program revealed that semaglutide reduced left atrial volumes, right ventricular dimensions, and transmitral E-wave velocity (reflecting the pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle).15 These are all consistent with decongestive and disease-modifying effects of semaglutide in obesity-related HFpEF, which is further substantiated by fewer “hard” clinical events of HF hospitalizations and urgent visits with semaglutide vs placebo, as noted both in the STEP-HFpEF Program6 and in the pooled analyses of the HFpEF populations from the SELECT (Semaglutide Effects on Heart Disease and Stroke in Patients With Overweight or Obesity), FLOW (A Research Study to See How Semaglutide Works Compared to Placebo in People With Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease), STEP-HFpEF, and STEP-HFpEF DM trials.19

A remaining unanswered question is whether semaglutide treatment in obesity-related HFpEF can reduce incident AF in those without AF at baseline. Because obesity is one of the most important risk factors in the development of incident AF,20 the potential benefit of semaglutide in this context would represent an important clinical advance. Although the STEP-HFpEF trials were not designed to systematically capture this factor (beyond spontaneous safety reporting), and the number of incident AF events was small, we did note slightly fewer such events in semaglutide-treated patients (0.9%) vs those receiving placebo (1.6%). This potential signal requires further investigation and validation in future trials.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

First, AF history and type were investigator reported and not ascertained based on the baseline electrocardiogram. STEP-HFpEF trials were primarily designed to evaluate HF-related symptoms, physical limitations and exercise function, and were not adequately powered for clinical events. Therefore, we were not able to address the relationship between AF subgroups and semaglutide effects on HF hospitalizations and urgent visits. Statistical power to detect treatment effect heterogeneity within specific subgroups was limited, and such analyses should be interpreted within the context of this limitation. Statistical analyses were not adjusted for multiplicity, given their exploratory nature. It is therefore possible that greater semaglutide-mediated improvements in KCCQ-CSS among people with (vs without) AF could be a chance finding, and therefore needs to be validated in future trials.

CONCLUSIONS

In the STEP-HFpEF Program, AF was observed in nearly one-half of patients with obesity-related HFpEF and was associated with several features of more advanced HF. Treatment with semaglutide led to significant improvements in HF-related symptoms, physical limitations, and exercise function, as well as reductions in weight, CRP, and NT-proBNP in people with and without AF, and across AF types. The magnitude of semaglutide-mediated improvements in HF-related symptoms and physical limitations was more pronounced in those with vs without AF at baseline.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are indebted to the trial patients, the investigators, and the trial site staff. Administrative support was provided by Isabella Goldsbrough Alves, PhD, of Apollo, OPEN Health Communications, funded by Novo Nordisk A/S.

FUNDING SUPPORT AND AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

This trial was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S. Administrative support for manuscript development was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S. Dr Verma is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and holds the Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Cardiovascular Surgery. Dr Petrie is supported by the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence Award (RE/13/5/30177 and RE/18/6/34217þ). Dr Borlaug is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL128526, R01HL162828, and U01HL160226, and by the US Department of Defense grant W81XWH2210245. Dr Davies is supported by the Leicester National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre, Leicester General Hospital. Dr Kitzman was supported in part by the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine and NIH grants U01AG076928, R01AG078153, R01AG045551, R01AG18915, P30AG021332, U24AG059624, and U01HL160272. Dr Shah was supported by NIH grants U54HL160273, R01HL107577, R01HL127028, R01HL140731, and R01HL149423. Dr Verma has received speaking honoraria and/or consulting fees from Abbott, Amarin, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, PhaseBio, and TIMI. Dr Butler is a consultant to Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AskBio, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardiac Dimension, CardioCell, Cardior, CSL Behring, CVRx, Cytokinetics, Daxor, Edwards Lifesciences, Element Science, Faraday, Foundry, G3P, Imbria, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Inventiva, Ionis, Levator, Lexicon, Lilly, LivaNova, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, Occlutech, Owkin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, PharmaIN, Prolaio, Pulnovo, Regeneron, Renibus, Roche, Salamandra, Salubris, Sanofi, scPharmaceuticals, Secretome, Sequana, SQ Innovation, Tenex, Tricog, Ultromics, Vifor, and Zoll. Dr Borlaug receives research support from the NIH and the United States Department of Defense, as well as research grant funding from AstraZeneca, Axon Therapies, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Mesoblast, Novo Nordisk, Rivus, and Tenax Therapeutics; has served as a consultant for Actelion, Amgen, Aria, Axon Therapies, BD, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eli Lilly, Imbria, Janssen, Merck, NGM, Novo Nordisk, NXT, and VADovations; and is named inventor (U.S. patent no. 10,307,179) for the tools and approach for a minimally invasive pericardial modification procedure to treat heart failure. Dr Davies has acted as consultant, advisory board member, and speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is an advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Carmot/Roche, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Zealand Pharma; is a speaker for Amgen and AstraZeneca; and has received grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. Dr Kitzman has received honoraria as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Corvia Medical, Ketyo, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Rivus; has received grant funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Rivus; and has stock ownership in Gilead Sciences. Dr Petrie has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacosmos, Roche, and SQ Innovations; and has served on committees or consulted for AbbVie, Akero, AnaCardio, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardiorentis, Corvia, Eli Lilly, Horizon Therapeutics, LIB Therapeutics, Moderna, New Amsterdam, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacosmos, Siemens, SQ Innovations, Takeda, Teikoku, and Vifor. Dr Shah has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Corvia, and Pfizer; and has recevied consulting fees from Abbott, Alleviant, Amgen, Aria CV, AstraZeneca, Axon Therapies, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cyclerion, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eidos, Imara, Impulse Dynamics, Intellia, Ionis, Lilly, Merck, MyoKardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Prothena, ReCor, Regeneron, Rivus, Sardocor, Shifamed, Tenax, Tenaya, and Ultromics. Drs Jensen, Rasmussen, and Rönnbäck are employees and shareholders of Novo Nordisk A/S. Dr Merkely has received speaker fees and/or research payments from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, DUKE Clinical Institute, Medtronic, and Novartis; and has recevied institutional grants from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, DUKE Clinical Institute, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, Terumo, and Vifor. Dr Kosiborod has served as a consultant or on an advisory board for 35Pharma, Alnylam, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Corcept Therapeutics, Cytokinetics, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Esperion Therapeutics, Janssen, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Merck (Diabetes and Cardiovascular), Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, scPharmaceuticals, Structure Therapeutics, Vifor, and Youngene Therapeutics; has received research grants from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim; holds stocks in Artera Health and Saghmos Therapeutics; and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk; and has received other research support from AstraZeneca and Vifor. Dr O’Keefe has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- 6MWD

6-minute walk distance

- BMI

body mass index

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- HF

heart failure

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- KCCQ-CSS

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire–Clinical Summary Score

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

APPENDIX For supplemental tables, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butt JH, Kondo T, Jhund PS, et al. Atrial fibrillation and dapagliflozin efficacy in patients with preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80:1705–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filippatos G, Farmakis D, Butler J, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction with and without atrial fibrillation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:970–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavie CJ, Pandey A, Lau DH, Alpert MA, Sanders P. Obesity and atrial fibrillation prevalence, pathogenesis, and prognosis: effects of weight loss and exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2022–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borlaug BA, Jensen MD, Kitzman DW, Lam CSP, Obokata M, Rider OJ. Obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: new insights and pathophysiological targets. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118:3434–3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obokata M, Borlaug BA. Response by Obokata and Borlaug to letters regarding article, “Evidence supporting the existence of a distinct obese phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.”. Circulation. 2018;137:416–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler J, Shah SJ, Petrie MC, et al. Semaglutide versus placebo in people with obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pooled analysis of the STEP-HFpEF and STEP-HFpEF DM randomised trials. Lancet. 2024;403:1635–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosiborod MN, Abildstrom SZ, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1069–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosiborod MN, Petrie MC, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in patients with obesity-related heart failure and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1394–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel RB, Shah SJ. Therapeutic targeting of left atrial myopathy in atrial fibrillation and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:497–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartipy U, Dahlstrom U, Fu M, Lund LH. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Packer M HFpEF is the substrate for stroke in obesity and diabetes independent of atrial fibrillation. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sattar N, Butler J, Lee MMY, et al. Body mass index and cardiorenal outcomes in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial: principal findings and meta-analysis with the DELIVER trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26:900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam CS, Rienstra M, Tay WT, et al. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: association with exercise capacity, left ventricular filling pressures, natriuretic peptides, and left atrial volume. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zakeri R, Chamberlain AM, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Temporal relationship and prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. Circulation. 2013;128:1085–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon SD, Ostrominski JW, Wang X, et al. Effect of semaglutide on cardiac structure and function in patients with obesity-related heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. Published online August 30, 2024. 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrie MC, Borlaug BA, Butler J, et al. Semaglutide and NT-proBNP in obesity-related HFpEF: insights from the STEP-HFpEF Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schou M, Petrie MC, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide and NYHA functional class in obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the STEP-HFpEF program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah SJ, Sharma K, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide and diuretic use in obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pooled analysis of the STEP-HFpEF and STEP-HFpEF-DM trials. Eur Heart J. Published online May 13, 2024. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosiborod M, Deanfield J, Pratley R, et al. Semaglutide in heart failure and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: a pooled analysis of the SELECT, FLOW, STEP-HFpEF, and STEP-HFpEF DM randomised trials. 2024. Lancet. 2024. In press; 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01643-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sha R, Baines O, Hayes A, et al. Impact of obesity on atrial fibrillation pathogenesis and treatment options. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13:e032277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.