Abstract

Sonic hedgehog (Shh) is a morphogen with important roles in embryonic development and in the development of a number of cancers. Its activity is modulated by interactions with binding partners and co-receptors including heparin and heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). To identify antagonists of Shh/heparin binding, a diverse collection of 34,560 chemicals was screened in single point 384-well format. We identified and confirmed twenty six novel small molecule antagonists with diverse structures including four scaffolds that gave rise to multiple hits. Nineteen of the confirmed hits blocked binding of the N-terminal fragment of Shh (ShhN) to heparin with IC50 values < 50 μM. In the Shh-responsive C3H10T1/2 cell model, four of the compounds demonstrated the ability to block ShhN-induced alkaline phosphatase activity. To demonstrate a direct and selective effect on ShhN ligand mediated activity, two of the compounds were able to block induction of Gli1 mRNA, a primary downstream marker for Shh signaling activity, in Shh-mediated but not Smoothened agonist (SAG)-mediated C3H10T1/2 cells. Direct binding of the two compounds to ShhN was confirmed by thermal shift assay and molecular docking simulations, with both compounds docking with the N-terminal heparin binding domain of Shh. Overall, our findings indicate that small molecule compounds that block ShhN binding to heparin and act to inhibit Shh mediated activity in vitro can be identified. We propose that the interaction between Shh and HSPGs provides a novel target for identifying small molecules that bind Shh, potentially leading to novel tool compounds to probe Shh ligand function.

Keywords: Sonic hedgehog, heparin, high-throughput screening, SAG, C3H10T1/2

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The secreted morphogen sonic hedgehog (Shh) is critical for embryonic development and in the development of a number of adult tissues [1, 2]. A plethora of steps and components are involved in Shh signaling, from its processing and secretion, to pathway engagement on the responding cell (reviewed in [2–5], and refs therein). During its biogenesis Shh is processed to generate an N-terminal product modified with cholesterol on the C-terminus [6] and palmitate on its N-terminus [7]. At the receiving cell, the primary cilium serves as the main location for most events related to the reception of the Shh signal (reviewed in [5]). Shh signaling is initiated by Shh ligand binding to the Patched (Ptch) receptor which relieves Ptch-mediated suppression of the 7-transmembrane transducer Smoothened (Smo) leading to pathway activation via Gli transcription factors (recently reviewed in [3, 5]).

A number of mechanisms (reviewed in [3, 5, 8]) have been proposed for how Shh is transported from secreting to receiving cells over short- and long-range, with recent studies suggesting that a series of extracellular molecular relays consisting of Scube2, heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG), cell-adhesion-molecule-related/downregulated by oncogenes (CDO), brother of CDO (BOC), growth arrest-specific protein 1 (GAS1) and hedgehog interacting protein (HHIP) are responsible in shuttling Shh from the extracellular environment to its cell surface receptor Ptch [9–11]. In the initial release steps, loading of Shh on to Scube2 shields the Shh lipid moieties and generates a soluble complex for transport [12]. In particular, HSPGs such as glypican [13–16] have been shown to interact with Shh and affect Shh release, trafficking and signaling [17–22]. Two potential sites of interaction between Shh and HSPG have been identified [23–26], with a Cardin-Weintraub (CW) consensus sequence [27] within the N-terminal region of Shh [17] serving as the preferred binding site (reviewed in [20]) along with a glycosaminoglycan (GAG)/“pseudo-active”/zinc-binding site in the core structure where GAG [23], Ptch [28], HHIP [29–31] and the Shh neutralizing antibody (5E1) [32] also bind. Mutation of the CW heparin binding domain (HBD) on Shh was shown to affect its ability to promote cerebellar cell proliferation in mice [17], and abolished the colocalization of HSPGs with Hh in Drosophila [33]. As with HSPGs, Shh can bind heparin directly [34, 35] through its CW HBD [17, 23, 24, 36, 37].

Dysregulation of Shh signaling has been implicated in disease with the pathway driving growth in a range of cancers through multiple mechanisms (reviewed in [5, 38–40]). Hence, significant effort has been undertaken to target the pathway with the most success being small molecule inhibitors of Smo (reviewed in [41, 42]). However, the observation of resistance to Smo inhibitors in patients (reviewed in [43]) has led to efforts to target elsewhere in the pathway. A role for Shh ligand-dependent activation has also been implicated in several cancers including colon, pancreatic, ovarian, breast, digestive tract, lung, prostate, acute myeloid leukemia and medulloblastoma [44–53]. In contrast to targeting Smo and downstream effectors, efforts to target upstream of Smo including at the level of Hh processing, Hh trafficking and Hh/Ptch binding (reviews [3, 5, 54–56], and refs therein) have been less studied. While it has been demonstrated that Shh binding to Ptch and subsequent signaling can be blocked at the level of Shh ligand by anti-Shh neutralizing antibodies [51, 57–59], truncated Shh ligand [60] and by the small molecule robotnikinin [61], none of these have progressed beyond preclinical studies [62].

Herein, we describe the results of a high-throughput screen to identify novel small molecule antagonists of Shh/heparin binding. From a screen of 34,560 compounds, 24 compounds were confirmed as ShhN/heparin antagonists, with two being able to specifically block Shh signaling in cells. Direct binding of the two compounds to Shh was confirmed by thermal shift, while molecular docking had both compounds docking at the heparin binding domain within the N-terminal region of Shh. These two compounds should serve as novel starting points for developing new tool compounds to probe Shh ligand function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Unless otherwise stated all reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) or Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) at the highest level of purity possible. C3H10T1/2, clone 8 murine embryonic fibroblast cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Fluorescein-conjugated heparin (flu-Hep) (cat. No. H-7482, mol. wt. ~ 18 kDa) was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Heparin (13 kDa) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Robotnikinin (AG-CR1-0069) was purchased from AdipoGen Corp. (San Diego, CA). Suramin and Surfen were from Sigma Aldrich. KAAD-cyclopamine was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The N-terminal domain of human Shh (ShhN, residues 24–197) protein was as previously described [60, 63, 64]. Thermo 384-well, flat-bottom, black, MaxiSorp plates (cat. no. 460518) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

2.2. Small molecule chemical collection and library management

For high-throughput screening (HTS), a chemical collection of 34,560 compounds was previously purchased from Asinex Corp (Winston-Salem, NC). All compounds in the Asinex library adhere to Lipinski’s rule of 5 [65], were registered in ScreenAble database (ScreenAble Solutions, Chapel Hill, NC) at BRITE and can be positionally located in bar-coded 384-well plates with associated SD file data. Compounds are stored at −20°C in 384-well Greiner V-bottom polypropylene plates (Greiner #781280) (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) in 100% DMSO at 10 mM and 1 mM concentrations. Repurchased compounds were from Asinex.

2.3. High-throughput assay for inhibitors of sonic hedgehog/heparin binding

Details of the development, optimization and validation of the high-throughput ShhN/heparin binding assay are described in [66]. Additions were carried out using a NanoScreen NSX-1536 (NanoScreen, Hanahan, SC) and washes using a Biotek ELx405 Select CW microplate washer (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT). Briefly, ShhN was added to 384-well (flat-bottom, black, MaxiSorp) plates at 200 ng/well in 50 mM NaHCO3 pH 9.5 (Coating Buffer) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed four times with 50 mM Na3PO4 pH 6.5, 150 mM NaCl (Binding Buffer). For HTS of the Asinex compound collection, after the ShhN incubation and wash steps, 50 μL of Binding Buffer was added to columns 3–24 and 50 μL of heparin (10 μM unlabeled 13 kDa in Binding Buffer) to columns 1 and 2 (maximum inhibition signal). Each compound from the Asinex set (100 nL of 10 mM stocks in DMSO) was placed into columns 3–22 using two dips with a 50 nL pin-tool head on a Biomek® NX (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA) to give a final compound concentration of 20 μM. Columns 1, 2, 23 and 24 received an equal volume (100 nL) of DMSO. Flu-heparin (20 μL/well of 500 nM in Binding Buffer) was then added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Plates were washed a further four times with Binding Buffer. Coating Buffer (20 μL) was then added to the wells and fluorescent intensity read at 485/520 nm using a BMG Pherastar (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC).

2.4. Dose response confirmation for inhibitors of sonic hedgehog/heparin binding

For IC50 determinations of Asinex screen hits, serial dilutions of compounds (10 mM stock concentration in DMSO) were performed in 100% DMSO with a 2-fold dilution factor resulting in 10 final concentrations spanning 80 μM to 0.156 μM. Intermediate compound concentration plates were made using the serially diluted compounds and assay plates were assembled as described for the single-concentration screen.

For each concentration, percent inhibition values were calculated and IC50 values determined using a three-parameter dose-response (variable slope) equation in ScreenAble (ScreenAble Solutions) or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

As for HTS above, after the ShhN incubation step, serially diluted compounds were then added (using eight dips with a 50 nL pin-tool head on the Biomek) into 50 μL of Binding Buffer to yield a 10-point 80 μM to 0.156 μM titration. For a positive inhibitor control, a 2-fold serial dilution of heparin (13 kDa) from 16 μM to 0.031 μM was included on every plate.

2.5. C3H10T1/2 cell-based assay for measuring inhibition of Shh activity

The ability of heparin and small molecules to block Shh-mediated signaling was assessed in the Shh-responsive C3H10T1/2 murine embryonic fibroblast cell line [67]. These cells induce alkaline phosphatase (AP) expression as a downstream marker of Shh activation. Activation can be induced using either ShhN protein or the small molecule Smoothened agonist (SAG) [68]. First, half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) for ShhN and SAG were determined essentially as described previously in 96-well plates [60, 63, 64]. Briefly, after 24 h, cells were incubated with varying concentrations of either ShhN or SAG for 5 days and AP activity assessed as previously described [59, 60, 63, 64]. For determining potential inhibitors, the C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated with either a fixed concentration of ShhN protein or SAG equivalent to their EC50 values in the presence or absence of the compounds. EC50 and IC50 values were determined in Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) with non-linear regression.

2.6. qRT-PCR for Gli1 and Ptch1 in C3H10T1/2 cells

ShhN- or SAG-mediated induction of the Hh target genes Gli1 and Ptch1 was assessed in C3H10T1/2 cells by qRT-PCR essentially as we have previously described [64]. Briefly, cells were cultured in 12-well plates at 60,000 cells per well and after 24 h incubated with either ShhN protein or SAG at their respective EC50 values in the presence or absence of heparin or compounds at their respective IC50 values. After a further 5 days, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cDNA synthesized using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher). Taqman assay primers and probes specific for mouse Gli1 and mouse Ptch1 were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher). The target sequences were amplified using the following thermal cycling protocol: initial denaturation at 95°C for 20 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 3 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. Endogenous normalization control used was β-actin. All assays were performed in duplicate and mRNA fold change determined by 2−ΔΔCt method. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test were used to evaluate the data using GraphPad Prism 7.

2.7. Protein thermal shift assay

Direct binding of compounds to ShhN protein was assessed by determining Tm shifts (protein thermal shift assay) using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). DSF was carried out on an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system equipped with Protein Thermal Shift™ Software (Life Technologies, version 1.1, Thermo Fisher) and using the Protein Thermal Shift™ kit. Protein melt reactions were prepared as follows based on manufacturer’s recommendation. ShhN protein (1–2 μM final concentration) was incubated with protein thermal shift buffer and protein thermal shift dye in a final volume of 20 μL in Fast Optical 96-well reaction plates and kept on ice. Plates were loaded into the instrument and melt curves run using standard continuous ramp speed (2°C/s) from 25°C to 97.5°C. For experiments with inhibitors, ShhN protein was incubated in the absence or presence of varying concentrations of compounds (1.56 to 50 μM). Data were collected on the instrument and analyzed using Protein Thermal Shift™ (Life Technologies, software version 1.1). The difference in temperature transition midpoints (ΔTm) between ShhN with and without inhibitor were determined.

2.8. Molecular docking

The Molecular Operating Environment (MOE, Chemical Computing Group, Toronto, Canada) software was used for docking and graphic visualization. The structures of the two screening hits (BAS 00653707 and BAS 0757892) were obtained from the ScreenAble database, sketched in MOE and their three-dimensional conformations generated on-the-fly. The crystal structure (PDB ID: 3M1N) of human ShhN [69] was used as a rigid structure to determine the binding mode of BAS 00653707 and BAS 0757892. All solvent atoms were deleted before initiating docking and unbiased molecular docking computation was used with MOE default parameters. The top ranking poses generated were assessed by comparing docking scores and evaluating the robustness of the formed interactions.

2.9. Data Analysis

ScreenAble (ScreenAble Solutions) and GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) were used for nonlinear regression statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and confirmation of compounds from HTS of ShhN/heparin binding assay

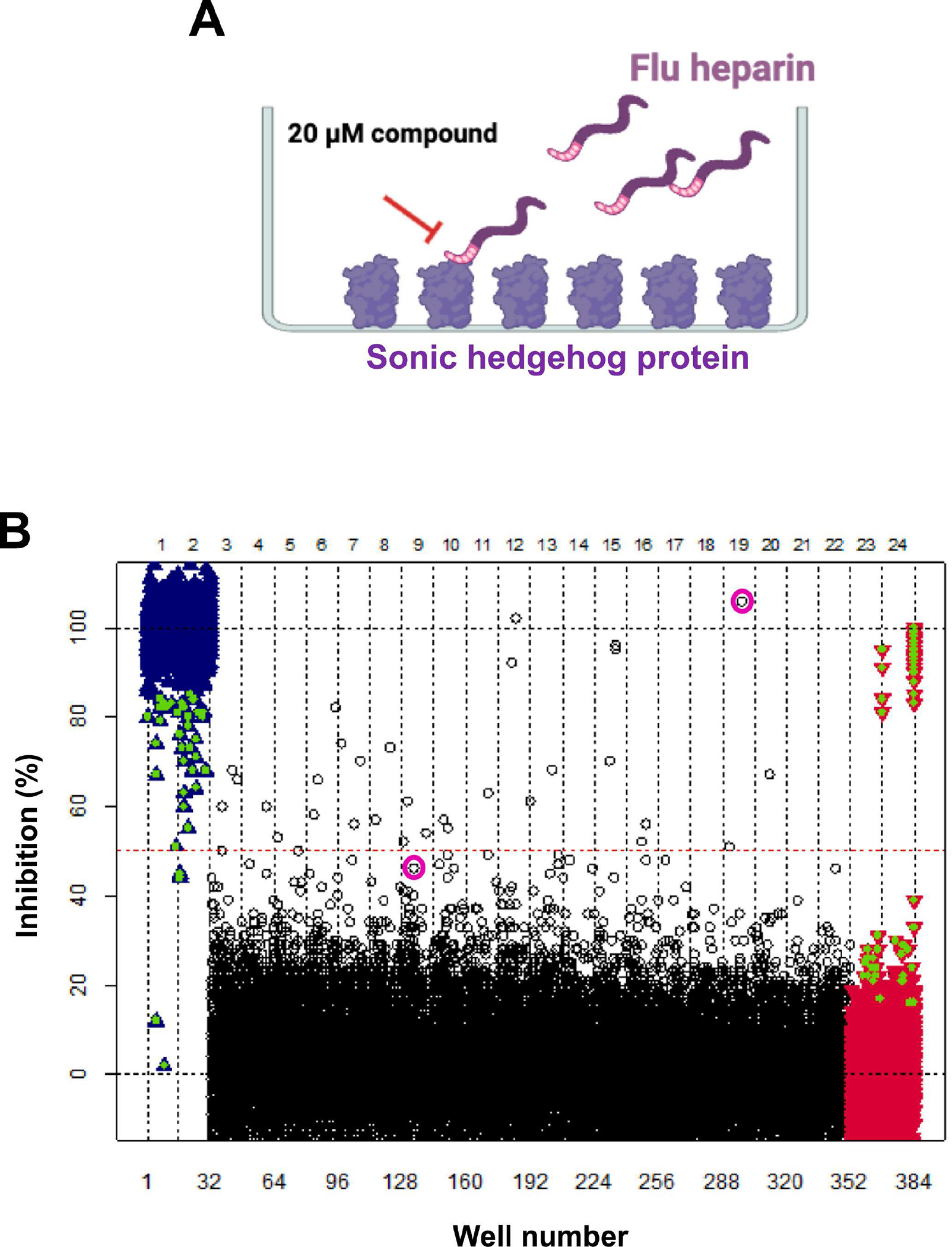

A solid-phase plate-based assay for identifying antagonists of ShhN heparin binding was developed and validated by our lab [66] (shown schematically in Fig. 1A). Briefly, 384-well plates are coated with ShhN protein at pH 9.5, wells washed with PBS, incubated with flu-heparin at pH 6.5 with or without compounds for a further 2 h and then fluorescence read. Using this assay to identify antagonists of ShhN/heparin binding, a diverse collection of 34,560 small organic molecules from a purchased Asinex set was screened in 384-well format (108 plates in total) at 20 μM single point concentration and percent inhibition values plotted for each compound (Fig. 1B). For HTS, wells in columns 1 and 2 contained 13 kDa heparin as a positive control inhibitor (10 μM, 20x IC50 value [66]) to give minimum signal control, and wells in columns 23 and 24 contained DMSO as maximum signal control. As an internal validation control, a dose response for 13 kDa heparin was run on every 5- or 10-plate assay set run (indicated by green triangles on Fig. 1B). For HTS, the average Z′ for this screen was 0.69. Seventy-seven compounds exhibiting inhibition values above a 40% threshold were identified for a primary hit rate of 0.22%, including 35 with inhibition values > 50%.

Fig. 1. High-throughput screening of an Asinex compound collection to identify antagonists of ShhN-heparin binding.

A. Schematic for the solid-phase plate-based assay for identifying antagonists of ShhN heparin binding. 384-well plates are coated with ShhN protein, wells washed with PBS, incubated with flu-heparin with or without compounds and then fluorescence read. Asinex compounds were added to the 384-well plates to give a final compound concentration of 20 μM. The ShhN/heparin binding assay was carried out in a final volume of 50 μL as described in detail in materials and methods. B. The HTS scatterplot shows percent inhibition values on the y-axis and well number on the x-axis. Asinex compounds from 108 384-well plates screened in the ShhN/heparin binding assay are shown as black circles. The dashed red line indicates 50% inhibition. Maximum (+ DMSO) and minimum (+ 10 μM 13 kDa heparin) signal controls are shown in red and blue, respectively. Green triangles indicate internal 13 kDa heparin dose-response control included in each 5- or 10-plate assay set run. The best two inhibitors identified from this study (compounds 4 and 24) are highlighted with purple circles.

To confirm actives from HTS, each compound was cherry-picked from primary library plates and tested in dose-response with data analyzed using ScreenAble to generate IC50 values. In this confirmation assay, 26 of the 77 compounds exhibited dose response curves with average IC50 values ranging from 16 to 67 μM, for an overall confirmation rate of 34%. Dose-response curves for all the 26 confirmed compounds as generated in ScreenAble are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. For all confirmed hits, the percent inhibition values from the primary screen and average IC50 values are shown in Fig. 2. Eighteen of the 26 actives tested from the HTS with primary inhibition values > 40% returned IC50 values < 50 μM.

Fig. 2. Chemical clustering of compounds confirmed by dose response in ShhN/heparin binding assay.

Compounds with > 40% inhibition in HTS were confirmed by dose-response in the ShhN/heparin binding assay. For IC50 determinations, serial dilutions of compounds were tested starting at a high concentration of 80 μM. Compounds (numbered 1 through 26, see also Supplemental Fig. 1) shown with Asinex ID, chemical structure, HTS primary % inhibition and dose response IC50 values (n = 2 independent dose response runs). a Percent inhibition values at highest dose tested. A subset of compounds was clustered into four chemotypes indicated by A-D.

K-means clustering analysis was used to group compounds based on structural similarity and within the 26 confirmed hits, four chemotype scaffolds were identified comprising 12 compounds (Fig. 2). They are scaffold A, the tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c] quinolines; scaffold B, the 1,3-thiazol-2-yl]amino] benzoic acids; scaffold C, the 1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl)-2-thiophen-2-yl-2H-pyrrol-5-ones and scaffold D, the 2-thioxo-dihydro-pyrimidine-4,6-diones and 1,3-diazinane-2,4,6-triones. Scaffold D contains one of the most potent compounds 1-(4-Fluoro-phenyl)-5-furan-2-ylmethylene-2-thioxo-dihydro-pyrimidine-4,6-dione, compound 7 found in this study with an average IC50 of 17.5 μM. Scaffold B contains compounds that have an activity range similar to the compounds in scaffolds A and D. In this scaffold (B), it appears that the position of the carboxylic acid group on the phenyl ring has a small impact on potency. Some of the least potent compounds 18, 19 and 20 with IC50 values of 58, 80 and 57.5 μM, respectively, are found in scaffold C. These compounds are the only compounds that have a central heterocycle that is substituted by three aryl or heterocyclic moieties. The third most potent compound is 9, 4-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c] quinoline-8-carboxylic acid, which has an IC50 of 23 μM, is a member of scaffold A. The remaining 14 compounds, including the most potent (IC50 value = 16.5 μM) from the primary screen, compound 24, were structurally unrelated. Ten of the 26 hits that confirmed with IC50 values < 50 μM in the initial Hh/heparin dose response assay from the primary library plates were repurchased as dry powders (LC-MS data confirming chemical structures was provided by the vendor) and included at least 1 compound from each chemotype. The resupplied compounds were dissolved in DMSO and first tested in dose response in the Hh/heparin binding assay, with IC50 values obtained that were comparable to the values obtained from the initial testing with the cherry-picked library compounds (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of inhibition values in binding and hedgehog functional assays for confirmed hits from chemical library screen of ShhN/heparin binding.

| Cpd No. | Sample ID | ShhN/heparin Avg. IC50 (μM) a | Inhibition of ShhN-induced AP IC50 (μM) | Inhibition of SAG-induced AP | Inhibition of ShhN-induced GLI1 and Ptch1 mRNA | Inhibition of SAG-induced GLI1 and Ptchl mRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASN03067791 | 38 | 1.6 | Yes | ||

| 4 | BAS | 53 | 42 | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | BAS | 49 | No inhibition | |||

| 8 | BAS | 48 | No inhibition | |||

| 10 | BAS | 57 | 23 | Yes | ||

| 11 | BAS | 46 | No inhibition | |||

| 20 | BAS | 55 | No inhibition | |||

| 21 | BAS | 45 | 25 | Weak | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | BAS | 33 | 26 | No | Yes | No |

| 26 | BAS | 44 | 21 | Yes | ||

| Robotnikinin | No inhibition | 6.4 | No | Yes | No |

For IC50 determinations, serial dilutions of compounds were tested starting at a high concentration of 80 μM. Average IC50 values from cherry-picked master plates and repurchased compounds.

We also assessed in our Hh/heparin binding assay compounds previously reported to directly bind Hh or to affect heparin binding to proteins (Fig. 3A). Robotnikinin was previously identified as binding directly to ShhN and blocking its activity [61]. Suramin is a polyanionic compound which has been shown to compete with heparin for binding to heparin-binding proteins [70, 71]. Surfen has been reported as binding directly to charged groups on heparin and blocking heparin-protein binding [72, 73]. As a positive control inhibitor, unlabeled heparin (13 kDa) blocked ShhN/flu-heparin binding with an IC50 value of 0.4 μM comparable to our previous observation [63]. Suramin did inhibit Hh/heparin binding with an IC50 value of 1.9 μM, whereas robotnikinin and surfen did not block binding (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Testing of compounds known to bind Shh, protein heparin binding domains or heparin in ShhN/heparin binding assay.

A. Chemical structures of suramin, surfen and robotnikinin. B. Dose-response curves for suramin, surfen, heparin (13 kDa) and robotnikinin in ShhN/heparin binding assay. For each concentration, percent inhibition values were calculated and IC50 values determined using a three-parameter dose-response (variable slope) equation in Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

3.2. Assessment of ShhN/heparin antagonists for activity in Hh functional cell-based assays

The confirmed hits from the Hh/heparin binding assay were next tested in the C3H10T1/2 cell-based functional assay that measures Hh ligand induced signaling activity. We have previously demonstrated that heparin binding to ShhN can block ShhN-mediated induction of AP in C3H10T1/2 cells [63]. In the C3H10T1/2 assay, cells are incubated with ShhN protein and induction of AP activity measured as an indicator of ShhN-mediated cell differentiation. The C3H10T1/2 assay is a widely used assay to determine Hh activity [60, 64] and assess pathway inhibition [59, 60]. AP activity in these cells can also be induced by binding of the small molecule SAG (Smoothened agonist) directly to the Smoothened (Smo) receptor [74], bypassing the need for ShhN binding to the Ptch receptor upstream of Smo. Representative dose response curves for ShhN and SAG induction of AP in C3H10T1/2 cells are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2 along with the inhibition curve for a widely used Shh pathway inhibitor KAAD-cyclopamine [75] as a positive control inhibitor. In the C3H10T1/2 assay, robotnikinin and heparin (13 kDa) were able to block ShhN- but not SAG-mediated AP induction (Fig. 4A). The ten repurchased compounds identified as blocking Hh/heparin binding with IC50 values < 50 μM were run in dose response in the C3H10T1/2 assay. Six of the compounds blocked ShhN-induced AP activity (Table 1), with three of those (compounds 4, 21 and 24) being able to differentially block ShhN- but not SAG-mediated induction of AP (Fig. 4B). Compound 21 showed weak inhibition and less of a differential effect on blocking ShhN versus SAG AP induction. Compounds 4 and 24 blocked ShhN (IC50 values of ~40 and ~25 μM for compounds 4 and 24 respectively) but not SAG induction of AP. The lack of effect in the SAG induction assay data also indicates that compounds 4 and 24 are not cytotoxic in these cells.

Fig. 4. Effects of identified ShhN/heparin antagonists on induction of Shh pathway activity in C3H10T1/2 cells.

C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated with either ShhN protein or SAG at their EC50 values (2 μg/ml for ShhN; 100 nM for SAG) in the presence of either 13 kDa heparin, robotnikinin (A) or the indicated compounds (B) in dose response for 5 days and AP activity measured. C. C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated as above with either ShhN protein or SAG in the absence or presence of the indicated compounds (50 μM for compounds 4, 21 and 24, 10 μM for robotnikinin). Induction of Gli1 and Ptch1 mRNA was measured by RT-PCR relative to β–actin and shown as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data were evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism. Relative to ShhN-mediated induction alone, compounds 4, 24 and robotnikinin show statistically significant decreases in Gli1 (****p<0.0001 for compounds 4 and 24, **p=0.002 for robotnikinin) and Ptch1 (****p<0.0001 for compounds 4, 24 and robotnikinin). ns = not significant.

As a more direct measure of Shh pathway activity in C3H10T1/2 cells, qRT-PCR was run to measure the effects of compounds 4, 21 and 24 on blocking ShhN- or SAG-mediated induction of the Shh target genes Gli1 and Ptch1. Compounds 4 and 24 significantly blocked ShhN-mediated induction of Gli1 (****p<0.001 for both compounds) and Ptch1 (****p<0.001 for both compounds) by ~6–7 fold compared to ShhN treatment alone (Fig. 4C, Table 1), but did not decrease SAG-mediated induction of Gli1 or Ptch1. In contrast, compound 21 did not block ShhN- or SAG-mediated induction of Gli1 or Ptch1 expression (ns, not significant). Robotnikinin, like compounds 4 and 24, also blocked ShhN-mediated Gli1 (**p=0.002) and Ptch1 induction (****p<0.001) but did not block SAG-mediated induction of Gli1 and Ptch1.

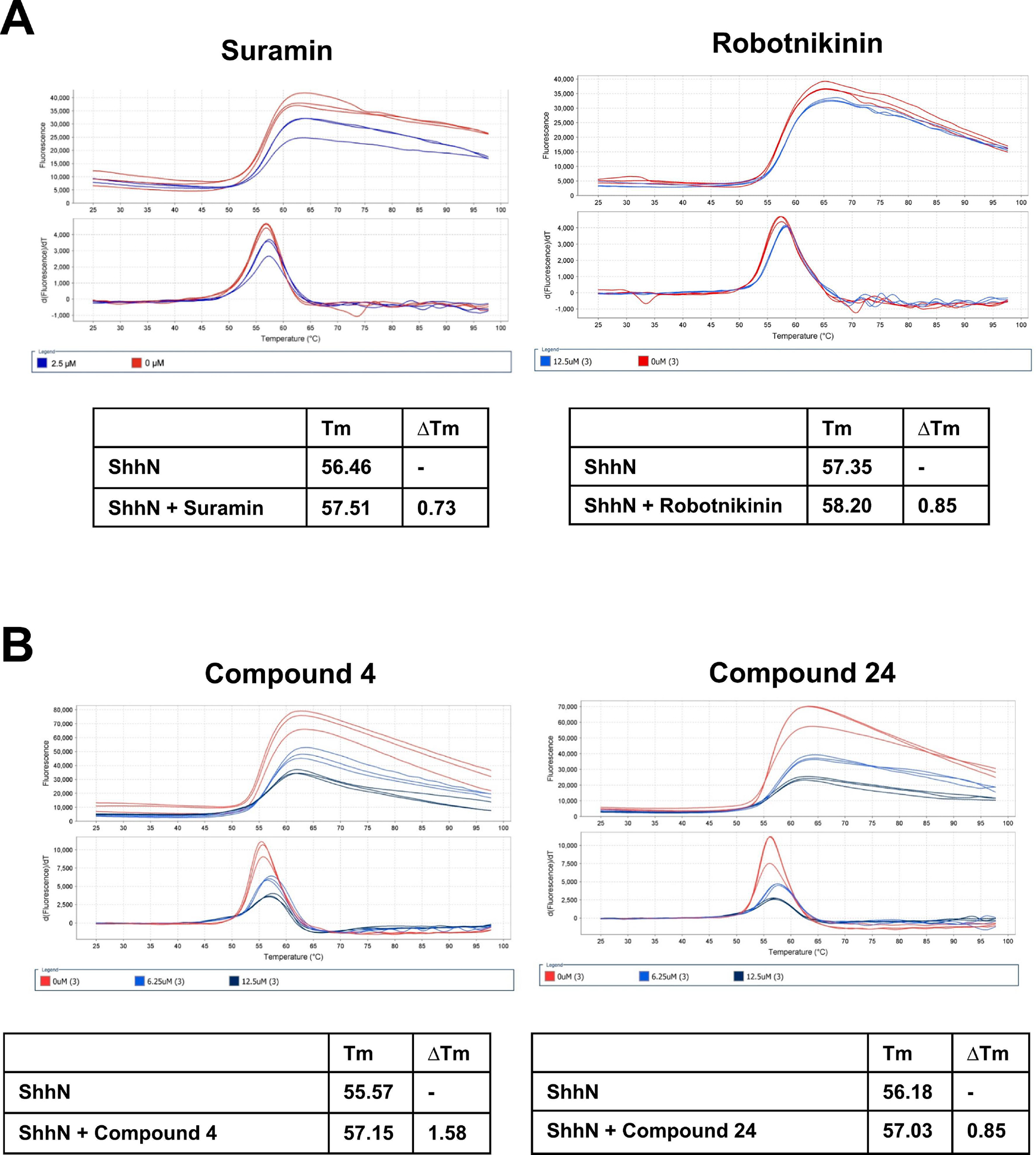

3.3. Protein thermal shift assessment and molecular docking analysis of antagonists binding to ShhN

Next, we used a protein thermal shift assay to assess compound binding directly to ShhN protein. Temperature transition midpoints (ΔTm) between ShhN with and without compound were determined. Suramin and Robotnikinin binding to ShhN produced Tm shifts of 0.73°C and 0.85°C respectively (Fig. 5A). Compounds 4 and 24 binding to ShhN produced Tm shifts of 1.58°C and 0.85°C respectively (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Assessment of binding of identified antagonists to ShhN by thermal shift assay.

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) was carried out on an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system as described in materials and methods. ShhN protein was incubated in the absence or presence of varying concentrations of compounds (1.56 to 50 μM) and plates heated from 25°C to 97.5°C. A. Suramin and robotnikinin; B. Compounds 4 and 24. Data were collected on the instrument and analyzed using Protein Thermal Shift™ software. The differences in temperature transition midpoints (ΔTm °C) between ShhN with and without inhibitor were determined.

Compounds 4 and 24 (chemical structures in Fig. 6A and LC-MS data confirming chemical structures in Supplemental Fig. 3), demonstrating Shh-selective blocking activity were next assessed as ligands for molecular docking using our previously determined crystal structure for ShhN [69] (Protein Data Base: 3M1N). The ShhN structure is shown in Fig. 6B with the consensus CW HBD located in the N-terminal region shown as the stick and ball section of the protein and the core GAG binding site also noted. Although no single reaction dominated, the highest ranked potential interaction (pose) for compounds 4 (Fig. 6C) and 24 (Fig. 6D) has both binding with parts of the N-terminal CW HBD with compound 24 having more extensive interactions, primarily H-bonds, to this part of the protein.

Figure 6. Molecular docking of compounds 4 and 24 on ShhN crystal structure.

A. Chemical structures of compounds 4 and 24. B. Cartoon representation of x-ray crystal structure of Shh N-terminal domain [69] (PDB ID: 3M1N). Stick and ball section of the protein is the consensus Cardin-Weintraub (CW) heparin binding domain (HBD) with nitrogen atoms in blue and oxygen atoms in red. The large ball residues are K38 (one of the positively charged residues in the N-terminal CW motif HBD) and K178 (one of the positively charged residues in the core GAG binding site) (note the N-terminal Cys in human ShhN is residue 24 after processing). The aqua-colored ball is the coordinated zinc ion. Molecular docking of compounds 4 (C) and 24 (D) to ShhN. CW HBD shown as gray stick and ball. Green is compound. Lines indicate hydrogen bond and numbers are bond distance.

4. Discussion

Identifying small molecule chemicals that target Sonic hedgehog (Shh) ligand interactions with its binding partners and co-receptors is of great interest as tools to probe function and as potential “leads” to target those cancers driven by abnormal expression of Shh [44–50]. In our study, we chose to target the Shh heparin/HSPG interaction as heparin and HSPGs [13, 76, 77] act as crucial modulators of Shh activity. Identifying small molecule chemicals that bind to extracellular ligands to block their activity can be challenging due to the typically large binding interfaces involved [78–81]. To identify Shh ligand antagonists, we used our previously developed solid-phase Shh/heparin binding assay [66] in high-throughput mode to screen a diverse compound collection. Two compounds were identified that blocked binding of ShhN to heparin and were also able to inhibit Shh-dependent signaling. These two compounds were shown to bind directly to the ShhN protein, with molecular modeling suggesting they interact with the consensus CW heparin binding domain located in the N-terminal part of ShhN.

From a high-throughput screen of 34,560 diverse small molecule compounds, we identified 77 compounds with > 40% inhibition, with 26 of those being confirmed by dose response as being able to block ShhN binding to heparin. Four distinct chemical scaffolds were identified among the 26 compounds indicating the ability of this assay to mine structurally related compounds from a diverse set of chemicals. To assess if the confirmed compounds were also able to block Shh ligand-dependent signaling, we utilized the Shh responsive cell line model C3H10T1/2 [59, 60, 64], for which Shh-dependent signaling can be induced by either ShhN protein binding to the Ptch receptor which relieves repression of Smo mediated signaling, or by addition of the small molecule agonist SAG [68], which binds directly to Smo to activate downstream signaling. This second mechanism bypasses the need for a Shh/Ptch interaction and allowed us to dissect and triage these compounds. Two of the compounds (4 and 24) were able to block ShhN-induced but not SAG-induced AP activity indicating they act directly on the ShhN protein. In a direct Shh pathway readout, we confirmed these two compounds could block ShhN- but not SAG-mediated activation of Gli1 and Ptch1 mRNA in the C3H10T1/2 cells. We [63] and others [20] have previously shown that heparin can block Shh activity but not Smo agonist activity in the C3H10T1/2 assay, and that potency is related to the size of the heparin molecules. The potencies we observed for compounds 4 and 24 were comparable to that of the 5 kDa heparin we previously tested in the C3H10T1/2 assay [66]. As a further comparison, we chose to look at several compounds previously reported to bind to either Shh protein directly (robotnikinin, [61]), or to heparin binding domains in other proteins (suramin, [70, 71]) or to heparin and related molecules (surfen, [72, 73]). While robotnikinin, like compounds 4 and 24, was also able to block ShhN- but not SAG-induced Hh pathway activity, we found it did not disrupt ShhN heparin binding in our assay suggesting a differing mechanism of action of our compounds (4 and 24) compared to robotnikinin. Comparable to compounds 4 and 24, suramin also blocked ShhN heparin binding and ShhN activation in C3H10T1/2 cells strengthening our findings that targeting the HBD domain of Shh is an effective strategy to block Shh ligand mediated signaling. As assessed by thermal shift, compounds 4 and 24 had binding affinities for ShhN comparable to robotnikinin and suramin. However, compounds 4 and 24 are chemically distinct from the polyanionic suramin.

Compound 4, (3Z)-5-(4-Ethylphenyl)-3-(furan-2-ylmethylidene) furan-2-one, is the only active compound that contains no nitrogen or sulfur atoms. Compound 24, N-[2-(Cyclopentylamino) ethyl] thiophene-2-carboxamide, is the only active compound containing a cycloalkane connected via an ethylene diamine group to a heterocyclic moiety, and it is also perhaps one of the least constrained compounds. Compared to the macrocycle robotnikinin (mol. wt. 454.95), compounds 4 (mol. wt. 266.3) and 24 (mol. wt. 238.4) are smaller and less complex. Compounds 4, 24 and robotnikinin have predicted polar surface areas of 39, 69 and 85Å2, respectively, which is indicative of their ability to permeate cell membranes. Where they differ is that only compound 24 contains a basic nitrogen. Compounds 4 and 24 contain no optically active centers and in the case of compound 24, contain no double bonds that could lead to isomerization. These differences can facilitate ease of synthesis of analogs for optimizing activity. Improving the potency of compounds 4 and 24 will require extensive chemistry to elucidate structure-activity relationship (SAR).

Our molecular modeling simulations indicated that the two compounds we identified (4 and 24) can bind directly to the Shh protein and that this interaction occurs via the CW HBD within the flexible N terminus sequence [60, 69]. The CW motif comprises a cluster of basic residues (xBBBxxBx, where B are basic residues) [27] and in human Shh the sequence spanning residues 32–38 of the N-terminal region (GKRRHPKK) fits the CW consensus motif [17, 82]. The N-terminal region is highly conserved among Hh family members with two of the HBD residues, Arg33 and Lys37, being absolutely conserved [82]. In our docking simulations, compounds 4 and 24 both make interactions with the conserved Arg33 within the CW HBD of ShhN, with compound 4 making additional interactions with Arg34 and compound 24 additional interactions with Arg28. Further, we and others have shown that the N-terminal portion of ShhN is critical, with function compromised in Shh variants with mutated or truncated CW sequences [17, 60, 82–84]. While mutational studies suggest the presence of more than one heparin/HSPG binding site on ShhN [23–26, 37], our best docking pose had compounds 4 and 24 interacting with the CW HBD located within the N-terminal region of ShhN.

While in structural studies the N-terminal sequence of ShhN possessing the CW HBD extends away from the main structure [69], making it accessible for heparin or HSPG binding, its accessibility in vivo may be less apparent. Current studies suggest that in the extracellular environment, Shh is transported from secreting cells to responding cells via molecular relays consisting of Scube, HSPGs and Hh co-receptors [9–11], and that some of these interactions are mediated by the N-terminal CW region of Shh [10]. While it has been proposed that one of the mechanisms in which Shh is released from secreting cells requires proteolytic cleavage [85–87] that would result in removal of the N-terminal sequence spanning the palmitoylated N-terminus [7] and CW domain [20, 88], it has been suggested that genetic evidence for this cleavage is lacking [5]. Further, recent structural analyses indicate that the N-terminal palmitoylated region of Shh is critical for Ptch binding and regulation [89–93]. In these structures, two Ptch molecules engage with one ShhN molecule with the N-terminus of ShhN with its palmitate moiety inserting into a cavity of one Ptch molecule while the second Ptch molecule contacts with the metal binding site on ShhN ([89–92], and reviewed in [5, 94]). While Qi et al reported that simultaneous engagement of both interfaces is required for efficient signaling in cells [89], it has also been shown, although with low potency, that a palmitoylated 20 residue peptide comprising the N-terminal sequence of ShhN was sufficient to bind Ptch and activate the pathway [93]. Considering these many molecular interactions of Shh, how accessible the N-terminal HBD region of Shh would be in vivo to targeted compounds such as those identified in this study (compounds 4 and 24) is an intriguing question and requires further study.

To our knowledge, only one other chemical compound (robotnikinin) has been identified previously using lab-based HTS and shown to bind to and perturb Shh-ligand mediated activity [61]. Interestingly, subsequent molecular dynamic simulations indicate that robotnikinin binds in the vicinity of the pseudo-active/Zn binding site using in part interactions with the Zn ion and residues H134, H135 and E177 [95]. Macrocyclic peptides based on the region of HHIP that binds Shh have been designed and optimized for high affinity and shown to block Hh signaling in cell based assays [96].

As an alternative to lab-based HTS, computational based methodologies are increasingly being utilized and while there have been considerable efforts using such approaches to identify novel Smo inhibitors including most recently [97–99], there are few reports on using virtual screening to identify direct Shh binders. Pharmacophore modeling of robotnikinin has been used by Hwang et al to identify novel analogs with higher affinity for Hh [100]. As a follow up, to identify compounds that target Shh-Ptch binding, Hwang et al used a pharmacophore model targeting the pseudo-active site on Shh and 2 compounds with strong interactions with Shh were identified from a virtual screen of over 200,000 compounds in an Asinex database [101]. More recently the interaction surfaces of Shh-HHIP [30] and Shh-5E1 [32] were used by Yun et al to virtually screen over 200,000 compounds and 7 compounds were identified [102], which were also shown to be active in cellular assays for Hh pathway activity [102]. While these compounds had diverse scaffolds, docking simulations indicated that they all docked with ShhN using several key residues in common (His134, Asp147, Glu176, His180 and His182) [102], some of which (Asp 147, Glu176 and His 182) are involved in coordinating the bound Zn ion on ShhN [103]. In the Hwang study, residues His134, His 180 and His182 are also involved in the binding of the compounds they identified [101], suggesting close proximity of binding sites for the compounds from these two studies [101, 102].

We suggest that targeting the N-terminal CW HBD region of ShhN with small molecule chemical compounds such as those identified in our current study should block binding of Shh to HSPGs and potentially to Ptch, and so be an effective strategy to block Shh signaling. Further, the compounds we identified by binding at the flexible N-terminus sequence CW HBD provide an alternative targeting strategy compared to those chemical compounds previously identified by HTS [61] and virtual screening [100–102], all which appear to bind at or near the pseudo-active site region of Shh. Hence, the antagonists of Shh heparin binding described in our study offer a potential new mechanistic approach compared to other Shh targeting strategies. Small molecule chemicals that directly target the Shh protein including those identified herein should have utility in dissecting its various mechanistic roles and offer a potential avenue to new therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Compounds with > 50% inhibition in HTS were confirmed by dose response in the ShhN/heparin binding assay (in two independent experiments, representative curves shown). For each concentration, percent inhibition values were calculated and IC50 values determined using a three-parameter dose-response (variable slope) equation in ScreenAble (ScreenAble Solutions). For all curves, the x axis shows compound concentration in micromolar, and the y axis shows % inhibition.

C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated with ShhN protein (A) or SAG (B) in dose response for 5 days and induction of AP activity measured as described before. A dose response curve for ShhN is included on each C3H10T1/2 assay plate as an internal control for these studies with an EC50 value range of 1.9 ± 0.8 μg/ml (n = 6) close to that we have previously reported [64]. (C) C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated with ShhN protein at its EC50 value (2 μg/ml) for 5 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of KAAD-cyclopamine (KAAD-cyc) and induction of AP activity measured.

LC-MS data for all repurchased compounds was provided by the vendor Asinex. LC-MS data confirming chemical structures for compound 4 (A) and compound 24 (B) are shown.

Highlights.

From a high throughput screen of ~35,000 small molecules, two compounds were identified that block Sonic hedgehog binding to heparin.

The two compounds inhibited Sonic hedgehog mediated signaling in a Shh-responsive cell line.

Thermal shift studies indicate that the two compounds bind directly to Shh protein.

Molecular docking predicts that the two compounds bind at the N-terminal Cardin-Weintraub consensus heparin binding domain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH under award numbers R15CA159209, U54AA030451, R01MD017405 and RCMI U54MD012392. Additional funding was from Golden LEAF Foundation and the BIOIMPACT Initiative of the State of North Carolina through the Biomanufacturing Research Institute & Technology Enterprise (BRITE) Center for Excellence at North Carolina Central University. The authors acknowledge Greg Cole and Blake Pepinsky for initial discussions. The assay schematic image in Figure 1 and the graphical abstract were created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Ingham P, McMahon A, Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles, Genes & Development 15(23) (2001) 3059–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Groves I, Placzek M, Fletcher AG, Of mitogens and morphogens: modelling Sonic Hedgehog mechanisms in vertebrate development, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 375(1809) (2020) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ingham PW, Hedgehog signaling, Current Topics in Developmental Biology 149 (2022) 1–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Qi X, Li X, Mechanistic Insights into the Generation and Transduction of Hedgehog Signaling, Trends Biochem Sci 45(5) (2020) 397–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang Y, Beachy PA, Cellular and molecular mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 24(9) (2023) 668–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Porter J, Young K, Beachy P, Cholesterol Modification of Hedgehog Signaling Proteins in Animal Development, Science 274(5285) (1996) 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pepinsky R, Zeng C, Wen D, Rayhorn P, Baker D, Williams K, Bixler S, Ambrose C, Garber E, Miatkowski K, Taylor FR, Wang E, Galdes A, Identification of a Palmitic Acid-modified Form of Human Sonic hedgehog, Journal of Biological Chemistry 273(22) (1998) 14037–14045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gradilla A-C, Guerrero I, Hedgehog on track: Long-distant signal transport and transfer through direct cell-to-cell contact, Cell-Cell Signaling in Development 150 (2022) 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wierbowski BM, Petrov K, Aravena L, Gu G, Xu Y, Salic A, Hedgehog pathway activation requires coreceptor-catalyzed, lipid-dependent relay of the Sonic Hedgehog ligand, Developmental cell 55(4) (2020) 450–467. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tang X, Chen R, Mesias VSD, Wang T, Wang Y, Poljak K, Fan X, Miao H, Hu J, Zhang L, A SURF4-to-proteoglycan relay mechanism that mediates the sorting and secretion of a tagged variant of sonic hedgehog, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(11) (2022) e2113991119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gude F, Froese J, Manikowski D, Di Iorio D, Grad J-N, Wegner S, Hoffmann D, Kennedy M, Richter RP, Steffes G, Hedgehog is relayed through dynamic heparan sulfate interactions to shape its gradient, Nature Communications 14(1) (2023) 758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang Q, Asarnow DE, Ding K, Mann RK, Hatakeyama J, Zhang Y, Ma Y, Cheng Y, Beachy PA, Dispatched uses Na+ flux to power release of lipid-modified Hedgehog, Nature 599(7884) (2021) 320–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Capurro M, Xu P, Shi W, Li F, Jia A, Filmus J, Glypican-3 Inhibits Hedgehog Signaling during Development by Competing with Patched for Hedgehog Binding, Developmental Cell 14(5) (2008) 700–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ortmann C, Pickhinke U, Exner S, Ohlig S, Lawrence R, Jboor H, Dreier R, Grobe K, Sonic hedgehog processing and release are regulated by glypican heparan sulfate proteoglycans, Journal of Cell Science 128(12) 2374–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Filmus J, Capurro M, The role of glypicans in Hedgehog signaling, Matrix Biology 35 (2014) 248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Guo W, Roelink H, Loss of the Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Glypican5 Facilitates Long-Range Sonic Hedgehog Signaling, Stem cells 37(7) (2019) 899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rubin J, Choi Y, Segal R, Cerebellar proteoglycans regulate sonic hedgehog responses during development, Development 129(9) (2002) 2223–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Callejo A, Torroja C, Quijada L, Guerrero I, Hedgehog lipid modifications are required for Hedgehog stabilization in the extracellular matrix, Development 133(3) (2006) 471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dierker T, Dreier R, Migone M, Hamer S, Grobe K, Heparan sulfate and transglutaminase activity are required for the formation of covalently cross-linked hedgehog oligomers, Journal of Biological Chemistry 284(47) (2009) 32562–32571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Manikowski D, Jakobs P, Jboor H, Grobe K, Soluble Heparin and Heparan Sulfate Glycosaminoglycans Interfere with Sonic Hedgehog Solubilization and Receptor Binding, Molecules 24(8) (2019) 1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bandari S, Exner S, Ortmann C, Bachvarova V, Vortkamp A, Grobe K, Sweet on Hedgehogs: Regulatory Roles of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Hedgehog-Dependent Cell Proliferation and Differentiation, Current Protein and Peptide Science 16(1) (2015) 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ramsbottom SA, Pownall ME, Regulation of Hedgehog Signalling Inside and Outside the Cell, J Dev Biol 4(3) (2016) 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Whalen DM, Malinauskas T, Gilbert RJ, Siebold C, Structural insights into proteoglycan-shaped Hedgehog signaling, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(41) (2013) 16420–16425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chang S-C, Mulloy B, Magee AI, Couchman JR, Two distinct sites in sonic Hedgehog combine for heparan sulfate interactions and cell signaling functions, Journal of Biological Chemistry 286(52) (2011) 44391–44402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jaegers C, Roelink H, Association of Sonic Hedgehog with the Extracellular Matrix Requires its Putative Zinc-Peptidase Activity, BMC Molecular and Cell Biology 22 (2019) 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Manikowski D, Steffes G, Froese J, Exner S, Ehring K, Gude F, Di Iorio D, Wegner SV, Grobe K, Drosophila hedgehog signaling range and robustness depend on direct and sustained heparan sulfate interactions, Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 10 (2023) 1130064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cardin A, Weintraub H, Molecular modeling of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions, Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 9(1) (1989) 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gong X, Qian H, Cao P, Zhao X, Zhou Q, Lei J, Yan N, Structural basis for the recognition of Sonic Hedgehog by human Patched1, Science 361(6402) (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bishop B, Aricescu A, Harlos K, O’Callaghan C, Jones E, Siebold C, Structural insights into hedgehog ligand sequestration by the human hedgehog-interacting protein HHIP, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 16(7) (2009) 698–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bosanac I, Maun H, Scales S, Wen X, Lingel A, Bazan J, de Sauvage F, Hymowitz S, Lazarus R, The structure of SHH in complex with HHIP reveals a recognition role for the Shh pseudo active site in signaling, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 16(7) (2009) 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Griffiths SC, Schwab RA, El Omari K, Bishop B, Iverson EJ, Malinauskas T, Dubey R, Qian M, Covey DF, Gilbert RJ, Hedgehog-Interacting Protein is a multimodal antagonist of Hedgehog signalling, Nature communications 12(1) (2021) 7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Maun HR, Wen X, Lingel A, de Sauvage FJ, Lazarus RA, Scales SJ, Hymowitz SG, Hedgehog pathway antagonist 5E1 binds hedgehog at the pseudo-active site, Journal of Biological Chemistry 285(34) (2010) 26570–26580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Vyas N, Goswami D, Manonmani A, Sharma P, Ranganath H, VijayRaghavan K, Shashidhara L, Sowdhamini R, Mayor S, Nanoscale Organization of Hedgehog Is Essential for Long-Range Signaling, Cell 133(7) (2008) 1214–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bumcrot D, Takada R, McMahon A, Proteolytic processing yields two secreted forms of sonic hedgehog., Molecular and Cellular Biology 15(4) (1995) 2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lee J, Ekker S, von Kessler D, Porter J, Sun B, Beachy P, Autoproteolysis in hedgehog protein biogenesis, Science 266(5190) (1994) 1528–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang F, McLellan J, Ayala A, Leahy D, Linhardt R, Kinetic and structural studies on interactions between heparin or heparan sulfate and proteins of the hedgehog signaling pathway, Biochemistry 46(13) (2007) 3933–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Farshi P, Ohlig S, Pickhinke U, Hoing S, Jochmann K, Lawrence R, Dreier R, Dierker T, Grobe K, Dual roles of the Cardin-Weintraub motif in multimeric Sonic hedgehog, Journal of Biological Chemistry 286(26) (2011) 23608–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jing J, Wu Z, Wang J, Luo G, Lin H, Fan Y, Zhou C, Hedgehog signaling in tissue homeostasis, cancers, and targeted therapies, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 8(1) (2023) 315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ, Targeting the Hedgehog pathway in cancer, Nat Rev Drug Discov 5(12) (2006) 1026–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kar S, Deb M, Sengupta D, Shilpi A, Bhutia SK, Patra SK, Intricacies of hedgehog signaling pathways: a perspective in tumorigenesis, Experimental cell research 318(16) (2012) 1959–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chahal KK, Parle M, Abagyan R, Hedgehog pathway and smoothened inhibitors in cancer therapies, Anti-cancer drugs 29(5) (2018) 387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Feng Z, Zhu S, Li W, Yao M, Song H, Wang R-B, Current approaches and strategies to identify Hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitors for cancer therapy, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry (2022) 114867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Nicheperovich A, Townsend-Nicholson A, Towards Precision Oncology: The Role of Smoothened and Its Variants in Cancer, Journal of Personalized Medicine 12(10) (2022) 1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yauch RL, Gould SE, Scales SJ, Tang T, Tian H, Ahn CP, Marshall D, Fu L, Januario T, Kallop D, Nannini-Pepe M, Kotkow K, Marsters JC, Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ, A paracrine requirement for hedgehog signalling in cancer, Nature 455(7211) (2008) 406–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Theunissen J, de Sauvage F, Paracrine Hedgehog signaling in cancer, Cancer Research 69(15) (2009) 6007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].O’Toole SA, Machalek DA, Shearer RF, Millar EK, Nair R, Schofield P, McLeod D, Cooper CL, McNeil CM, McFarland A, Hedgehog overexpression is associated with stromal interactions and predicts for poor outcome in breast cancer, Cancer research 71(11) (2011) 4002–4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Berman DM, Karhadkar SS, Maitra A, Montes De Oca R, Gerstenblith MR, Briggs K, Parker AR, Shimada Y, Eshleman JR, Watkins DN, Beachy PA, Widespread requirement for Hedgehog ligand stimulation in growth of digestive tract tumours, Nature 425(6960) (2003) 846–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Szczepny A, Rogers S, Jayasekara WSN, Park K, McCloy RA, Cochrane CR, Ganju V, Cooper WA, Sage J, Peacock CD, The role of canonical and non-canonical Hedgehog signaling in tumor progression in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer, Oncogene 36(39) (2017) 5544–5550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fan L, Pepicelli CV, Dibble CC, Catbagan W, Zarycki JL, Laciak R, Gipp J, Shaw A, Lamm ML, Munoz A, Hedgehog signaling promotes prostate xenograft tumor growth, Endocrinology 145(8) (2004) 3961–3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Liu Y, Yuelling LW, Wang Y, Du F, Gordon RE, O’Brien JA, Ng JM, Robins S, Lee EH, Liu H, Astrocytes promote medulloblastoma progression through hedgehog secretion, Cancer research 77(23) (2017) 6692–6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bailey JM, Swanson BJ, Hamada T, Eggers JP, Singh PK, Caffery T, Ouellette MM, Hollingsworth MA, Sonic hedgehog promotes desmoplasia in pancreatic cancer, Clinical cancer research 14(19) (2008) 5995–6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Park K-S, Martelotto LG, Peifer M, Sos ML, Karnezis AN, Mahjoub MR, Bernard K, Conklin JF, Szczepny A, Yuan J, A crucial requirement for Hedgehog signaling in small cell lung cancer, Nature medicine 17(11) (2011) 1504–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zahreddine HA, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Assouline S, Gendron P, Romeo AA, Morris SJ, Cormack G, Jaquith JB, Cerchietti L, Cocolakis E, The sonic hedgehog factor GLI1 imparts drug resistance through inducible glucuronidation, Nature 511(7507) (2014) 90–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kandel N, Wang C, Hedgehog Autoprocessing: From Structural Mechanisms to Drug Discovery, Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 9 (2022) 900560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Stanton B, Peng L, Small-molecule modulators of the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway, Molecular BioSystems 6(1) (2010) 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Heretsch P, Tzagkaroulaki L, Giannis A, Modulators of the hedgehog signaling pathway, Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 18(18) (2010) 6613–6624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ericson J, Morton S, Kawakami A, Roelink H, Jessell T, Two critical periods of Sonic Hedgehog signaling required for the specification of motor neuron identity, Cell 87(4) (1996) 661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Michaud NR, Wang Y, McEachern KA, Jordan JJ, Mazzola AM, Hernandez A, Jalla S, Chesebrough JW, Hynes MJ, Belmonte MA, Novel Neutralizing Hedgehog Antibody MEDI-5304 Exhibits Antitumor Activity by Inhibiting Paracrine Hedgehog SignalingFully Human Anti-Hedgehog Antibodies, Molecular cancer therapeutics 13(2) (2014) 386–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wang L, Liu Z, Gambardella L, Delacour A, Shapiro R, Yang J, Sizing I, Rayhorn P, Garber E, Benjamin C, Williams K, Taylor F, Barrandon Y, Ling LE, Burkly L, Conditional disruption of hedgehog signaling pathway defines its critical role in hair development and regeneration., J Invest Dermatol 114(5) (2000) 901–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Williams KP, Rayhorn P, Chi-Rosso G, Garber EA, Strauch KL, Horan GS, Reilly JO, Baker DP, Taylor FR, Koteliansky V, Pepinsky RB, Functional antagonists of sonic hedgehog reveal the importance of the N terminus for activity, J Cell Sci 112 ( Pt 23) (1999) 4405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Stanton B, Peng L, Maloof N, Nakai K, Wang X, Duffner J, Taveras K, Hyman J, Lee S, Koehler A, A small molecule that binds Hedgehog and blocks its signaling in human cells, Nature Chemical Biology 5(3) (2009) 154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Carpenter RL, Ray H, Safety and tolerability of sonic hedgehog pathway inhibitors in cancer, Drug Safety 42(2) (2019) 263–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Daye LR, Gibson W, Williams KP, Development of a high throughput screening assay for inhibitors of hedgehog-heparin interactions, International Journal of High Throughput Screening 2010 (2010) 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- [64].House AJ, Daye LR, Tarpley M, Addo K, Lamson DS, Parker MK, Bealer WE, Williams KP, Design and characterization of a photo-activatable hedgehog probe that mimics the natural lipidated form, Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 567 (2015) 66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ, Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings, Adv. Drug Delivery. Rev 23(1–3) (1997) 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lamson DR, Hughes M, Adcock A, Smith GR, Williams KP, Development and validation of a hedgehog heparin-binding assay for high-throughput screening, MethodsX 8 (2020) 101207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Nakamura T, Aikawa T, Iwamoto-Enomoto M, Iwamoto M, Higuchi Y, Maurizio P, Kinto N, Yamaguchi A, Noji S, Kurisu K, Induction of Osteogenic Differentiation by Hedgehog Proteins, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 237(2) (1997) 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Frank-Kamenetsky M, Zhang XM, Bottega S, Guicherit O, Wichterle H, Dudek H, Bumcrot D, Wang FY, Jones S, Shulok J, Small-molecule modulators of Hedgehog signaling: identification and characterization of Smoothened agonists and antagonists, Journal of biology 1(2) (2002) 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Pepinsky R, Rayhorn P, Day E, Dergay A, Williams K, Galdes A, Taylor F, Boriack-Sjodin P, Garber E, Mapping Sonic Hedgehog-Receptor Interactions by Steric Interference, Journal of Biological Chemistry 275(15) (2000) 10995–11001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Ganesh V, Muthuvel S, Smith S, Kotwal G, Murthy K, Structural Basis for Antagonism by Suramin of Heparin Binding to Vaccinia Complement Protein, Biochemistry 44(32) (2005) 10757–10765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kathir KM, Kumar TKS, Yu C, Understanding the mechanism of the antimitogenic activity of suramin, Biochemistry 45(3) (2006) 899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Schuksz M, Fuster M, Brown J, Crawford B, Ditto D, Lawrence R, Glass C, Wang L, Tor Y, Esko J, Surfen, a small molecule antagonist of heparan sulfate, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(35) (2008) 13075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Weiss RJ, Gordts PL, Le D, Xu D, Esko JD, Tor Y, Small molecule antagonists of cell-surface heparan sulfate and heparin–protein interactions, Chemical Science 6(10) (2015) 5984–5993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chen JK, Taipale J, Young KE, Maiti T, Beachy PA, Small molecule modulation of Smoothened activity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99(22) (2002) 14071–14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Taipale J, Chen JK, Cooper MK, Wang B, Mann RK, Milenkovic L, Scott MP, Beachy PA, Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine, Nature 406(6799) (2000) 1005–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].McLellan JS, Yao S, Zheng X, Geisbrecht BV, Ghirlando R, Beachy PA, Leahy DJ, Structure of a heparin-dependent complex of Hedgehog and Ihog, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(46) (2006) 17208–17213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].The I, Bellaiche Y, Perrimon N, Hedgehog movement Is regulated through tout velu–dependent synthesis of a heparan sulfate proteoglycan, Molecular Cell 4(4) (1999) 633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Arkin MR, Tang Y, Wells JA, Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality, Chemistry & biology 21(9) (2014) 1102–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Jones S, Thornton JM, Principles of protein-protein interactions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93(1) (1996) 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kieffer C, Jourdan JP, Jouanne M, Voisin-Chiret AS, Noncellular screening for the discovery of protein–protein interaction modulators, Drug Discovery Today 25(9) (2020) 1592–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Scott DE, Bayly AR, Abell C, Skidmore J, Small molecules, big targets: drug discovery faces the protein–protein interaction challenge, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 15(8) (2016) 533–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Goetz J, Singh S, Suber L, Kull F, Robbins D, A highly conserved amino-terminal region of sonic hedgehog Is required for the formation of Its freely diffusible multimeric form, Journal of Biological Chemistry 281(7) (2006) 4087–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Jarov A, Williams K, Ling L, Koteliansky V, Duband J, Fournier-Thibault C, A dual role for Sonic hedgehog in regulating adhesion and differentiation of neuroepithelial cells., Developmental biology 261(2) (2003) 520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Testaz S, Jarov A, Williams K, Ling L, Koteliansky V, Fournier-Thibault C, Duband J, Sonic hedgehog restricts adhesion and migration of neural crest cells independently of the Patched-Smoothened-Gli signaling pathway, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98(22) (2001) 12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Jakobs P, Exner S, Schürmann S, Pickhinke U, Bandari S, Ortmann C, Kupich S, Schulz P, Hansen U, Seidler DG, Scube2 enhances proteolytic Shh processing from the surface of Shh-producing cells, Journal of Cell Science 127(8) (2014) 1726–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Kastl P, Manikowski D, Steffes G, Schürmann S, Bandari S, Klämbt C, Grobe K, Disrupting Hedgehog Cardin–Weintraub sequence and positioning changes cellular differentiation and compartmentalization in vivo, Development 145(18) (2018) dev167221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Ohlig S, Pickhinke U, Sirko S, Bandari S, Hoffmann D, Dreier R, Farshi P, Götz M, Grobe K, An emerging role of Sonic Hedgehog shedding as a modulator of heparan sulfate interactions, The Journal of Biological Chemistry 288(7) (2013) 5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Manikowski D, Ehring K, Gude F, Jakobs P, Froese J, Grobe K, Hedgehog lipids: Promotors of alternative morphogen release and signaling? Conflicting findings on lipidated Hedgehog transport and signaling can be explained by alternative regulated mechanisms to release the morphogen, BioEssays 43(11) (2021) 2100133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Qi X, Schmiege P, Coutavas E, Li X, Two Patched molecules engage distinct sites on Hedgehog yielding a signaling-competent complex, Science 362(6410) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Qi X, Schmiege P, Coutavas E, Wang J, Li X, Structures of human Patched and its complex with native palmitoylated sonic hedgehog, Nature 560(7716) (2018) 128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Qian H, Cao P, Hu M, Gao S, Yan N, Gong X, Inhibition of tetrameric Patched1 by Sonic Hedgehog through an asymmetric paradigm, Nature communications 10(1) (2019) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Rudolf AF, Kinnebrew M, Kowatsch C, Ansell TB, El Omari K, Bishop B, Pardon E, Schwab RA, Malinauskas T, Qian M, The morphogen Sonic hedgehog inhibits its receptor Patched by a pincer grasp mechanism, Nature Chemical Biology 15(10) (2019) 975–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Tukachinsky H, Petrov K, Watanabe M, Salic A, Mechanism of inhibition of the tumor suppressor Patched by Sonic Hedgehog, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(40) (2016) E5866–E5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Kong JH, Siebold C, Rohatgi R, Biochemical mechanisms of vertebrate hedgehog signaling, Development 146(10) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Hitzenberger M, Schuster D, Hofer TS, The binding mode of the sonic hedgehog inhibitor robotnikinin, a combined docking and QM/MM MD study, Frontiers in Chemistry 5 (2017) 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Owens AE, de Paola I, Hansen WA, Liu Y-W, Khare SD, Fasan R, Design and evolution of a macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of the sonic hedgehog/patched interaction, Journal of the American Chemical Society 139(36) (2017) 12559–12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lu W, Zhang D, Ma H, Tian S, Zheng J, Wang Q, Luo L, Zhang X, Discovery of potent and novel smoothened antagonists via structure-based virtual screening and biological assays, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 155 (2018) 34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Mohebbi A, Ligand-based 3D pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, and molecular dynamic simulation of potential smoothened inhibitors, Journal of Molecular Modeling 29(5) (2023) 143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Song S, Jiang J, Zhao L, Wang Q, Lu W, Zheng C, Zhang J, Ma H, Tian S, Zheng J, Structural optimization on a virtual screening hit of smoothened receptor, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 172 (2019) 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Hwang S, Thangapandian S, Lee Y, Sakkiah S, John S, Lee KW, Discovery and evaluation of potential sonic hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitors using pharmacophore modeling and molecular dynamics simulations, Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 9(supp01) (2011) 15–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Hwang S, Thangapandian S, Lee KW, Molecular dynamics simulations of sonic hedgehog-receptor and inhibitor complexes and their applications for potential anticancer agent discovery, PLoS One 8(7) (2013) e68271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Yun T, Wang J, Yang J, Huang W, Lai L, Tan W, Liu Y, Discovery of small molecule inhibitors targeting the sonic hedgehog, Frontiers in Chemistry 8 (2020) 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Bonn-Breach R, Gu Y, Jenkins J, Fasan R, Wedekind J, Structure of Sonic Hedgehog protein in complex with zinc(II) and magnesium(II) reveals ion-coordination plasticity relevant to peptide drug design, Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75(Pt 11) (2019) 969–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Compounds with > 50% inhibition in HTS were confirmed by dose response in the ShhN/heparin binding assay (in two independent experiments, representative curves shown). For each concentration, percent inhibition values were calculated and IC50 values determined using a three-parameter dose-response (variable slope) equation in ScreenAble (ScreenAble Solutions). For all curves, the x axis shows compound concentration in micromolar, and the y axis shows % inhibition.

C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated with ShhN protein (A) or SAG (B) in dose response for 5 days and induction of AP activity measured as described before. A dose response curve for ShhN is included on each C3H10T1/2 assay plate as an internal control for these studies with an EC50 value range of 1.9 ± 0.8 μg/ml (n = 6) close to that we have previously reported [64]. (C) C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated with ShhN protein at its EC50 value (2 μg/ml) for 5 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of KAAD-cyclopamine (KAAD-cyc) and induction of AP activity measured.

LC-MS data for all repurchased compounds was provided by the vendor Asinex. LC-MS data confirming chemical structures for compound 4 (A) and compound 24 (B) are shown.