Abstract

In previous studies we have identified actin rearrangement-inducing factor 1 as an early gene product of Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus that is involved in the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. We have constructed viral recombinants with a mutated Arif-1 open reading frame that confirm the causal link of Arif-1 expression and the actin rearrangement observed as accumulation of F-actin at the plasma membrane at 3 to 7 h postinfection. Infection with Arif mutant viruses leads to the loss of actin accumulation at the plasma membrane in TN-368 cells, although in the course of infection, early actin cables and nuclear F-actin are observed as in wild-type-infected cells. By immunofluorescence studies, we have demonstrated the localization of Arif-1 at the plasma membrane, and confocal imaging reveals the colocalization to F-actin. Accordingly, the ∼47-kDa Arif-1 protein is observed exclusively in membrane fractions prepared at 4 to 48 h postinfection, with a decrease at 24 h postinfection. Phosphatase treatment suggests that Arif-1 is modified by phosphorylation. Antibodies against phosphotyrosine precipitate Arif-1 from membrane fractions, indicating that Arif-1 becomes tyrosine phosphorylated during the early and late phases of infection. In summary, our results indicate that functional Arif-1 is tyrosine phosphorylated and is located at the plasma membrane as a component of the actin rearrangement-inducing complex.

During their life cycle, viruses can interact specifically with the actin cytoskeleton of their host cells, resulting in a variety of alterations. Those alterations that are distinct from the effects that follow the virus-induced breakdown of the cells have been postulated to play a role in viral genome transcription and replication, virion assembly, and viral budding (for a review, see reference 5). Extensive changes of the actin cytoskeleton have been described in cells infected with the baculovirus Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV). The different stages of actin rearrangement include the induction of actin cables, followed by a second step of reorganizing the microfilaments, and the appearance of nuclear filamentous (F)-actin (3). The functional role of the virus-induced changes is still speculative.

AcMNPV belongs to the large DNA viruses and infects lepidopteran larvae. Viral replication and the morphogenesis of nucleocapsids take place in the cell nucleus and result in two forms of AcMNPV. Both forms are essential to complete the viral life cycle in the larvae; however, only budded viruses (BV) are the infectious agents in cell culture (for a review, see reference 2). BV enter cells via adsorptive endocytosis. The release of the nucleocapsids into the cytoplasm correlates with the formation of actin cables, which are described as transient structures from 1 until 4 h postinfection (p.i.) (3). The actin cables are thought to be directly induced by the nucleocapsids to facilitate transport to the nucleus (4, 13). The second step of actin rearrangement depends on early viral gene expression and is represented by F-actin aggregates at the ventral surface of Spodoptera frugiperda cells and the accumulation of F-actin at the plasma membrane in TN-368 cells (3, 17).

Recently, we have identified the Arif-1 (actin rearrangement-inducing factor 1) gene, an early gene of AcMNPV. Expression of Arif-1 alone leads to actin rearrangement which was comparable to changes of the actin cytoskeleton that are present at about 6 h p.i. (17). The causal link between Arif-1 expression and actin rearrangement during the early phase of infection has been confirmed by infection studies with AcMNPV recombinant viruses that carry mutations in the Arif-1 gene. To obtain insights into the functional role of Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement and its transduction pathway during the infection cycle, we have examined the expression and localization of Arif-1. Our results provide first evidence that Arif-1 resides at the place of action within the plasma membrane where Arif-1 induced F-actin accumulation was observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus growth.

Trichoplusia ni TN-368 (10) and S. frugiperda IPLB21 cells (19) were grown as monolayer cultures at 27°C in TC100 medium (8) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Infection with AcMNPV plaque isolate E (18) was performed at a multiplicity of 10 PFU per cell. Time zero was defined as the time when the AcMNPV inoculum was added to the cells.

BV were purified for the analysis of structural components. After sucrose gradient centrifugation, purified virus particles were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% NP-40 and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were mixed with equal volumes of Laemmli sample buffer (12), boiled for 5 min, and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Recombinant viruses. (i) Construction of Ac-arif-lacZ:

The Arif-1 gene of AcMNPV was disrupted by insertion of a lacZ expression cassette into the XbaI site of the Arif-1 open reading frame (Fig. 1). The transfer vector was built as follows. An oligonucleotide of 15 bp which contained an Sse8387I site flanked by XbaI sites was inserted into the XbaI sites of the pARIF-1 plasmid (17) which additionally carried a mutated XbaI site in the multiple cloning site, generating plasmid pARIF-Sse. The polyhedrin promoter-lacZ gene cassette was isolated from plasmid pAcRP23-Sse-lacZ (gift from Robert D. Possee) as an Sse8387I fragment and inserted into the Sse8387I site of the pARIF-Sse plasmid. The resulting plasmid, pARIF-phlacZ, with the polyhedrin promoter in the opposite direction from the genomic orientation of the polyhedrin gene, was used as the transfer vector.

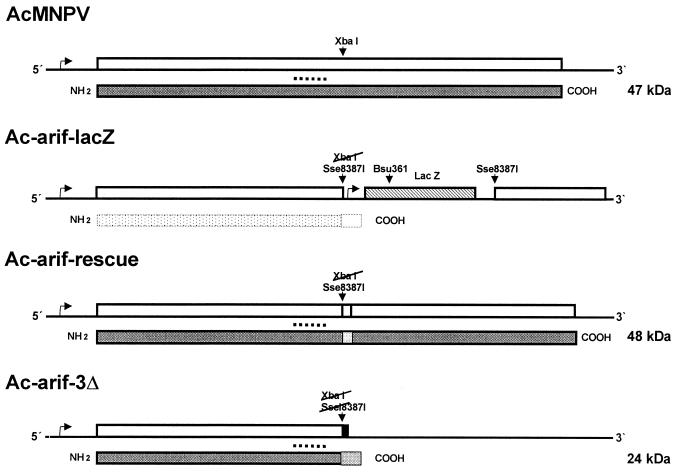

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the Arif-1 gene in the AcMNPV recombinant viruses. The recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ was generated by homologous recombination of wt AcMNPV and the transfer vector containing the polyhedrin promoter-lacZ gene cassette as an Sse8387I fragment in the XbaI site of the Arif-1 ORF. The recombinant viruses Ac-arif-rescue and Ac-arif-3Δ are based on the Ac-arif-lacZ virus and were generated by excision of the promoter-lacZ gene cassette. Religation of the virus DNA led to the in-frame insertion of five codons or to a frameshift, which resulted in the recombinant viruses Ac-arif-rescue and Ac-arif-3Δ, respectively. The open boxes represent the Arif-1 ORF and its various versions; the hatched box represents the lacZ ORF with the simian virus 40 (SV40) transcription termination signal; and the shaded boxes underneath the Arif-1 ORF represent the expressed proteins. The grey box in the Arif-1 protein of the recombinant Ac-arif-rescue indicates the five additional amino acids, and the grey box in the N-terminal Arif protein shows the 27 amino acids which form the unrelated C terminus of Arif-1. The expected Arif-1 protein of the recombinant Ac-arif-lacZ is shown as a stippled box. The dashed line above the proteins indicates the peptide against which the polyclonal anti-Arif serum is directed. The predicted molecular masses of the Arif-1 proteins are given on the right. The rightward arrow upstream of the lacZ gene indicates the transcriptional start site in the polyhedrin promoter, and the rightward arrow upstream of the Arif-1 ORF represents the transcriptional start site in the Arif-1 promoter.

(ii) Transfection and screening.

The recombinant Ac-arif-lacZ was obtained by cotransfection of virus DNA of AcMNPV plaque isolate E and the pARIF-phlacZ transfer vector into S. frugiperda cells using the transfection reagent DOTAP (Roche). The recombinant virus was identified by LacZ expression and subsequently plaque purified. Determination of the sequences flanking the inserted cassette revealed the insertion of 1,544 bp and the deletion of 394 bp upstream of the Arif-1 promoter between nucleotides 17550 and 17940 according to the published sequence of AcMNPV (1). The insertion carried part of the pBluescript sequences that flank the cloned Arif-1 gene in the pARIF-phlacZ transfer vector. Since the insertion and deletion disrupts the putative ORF22 (1), we generated the recombinant Ac-arif-rescue, which contained the insertion in addition to the restored Arif-1 open reading frame (ORF).

(iii) Construction of Ac-arif-rescue.

DNA from the recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ was digested with the restriction enzyme Sse8387I to excise the polyhedrin promoter-lacZ gene cassette and with Bsu361 to disrupt the lacZ ORF. Religation of the virus DNA resulted in in-frame insertion of 15 bp, providing the expression of five additional amino acids not contained in the wild-type (wt) Arif-1 (Fig. 1).

(iv) Construction of Ac-arif-3Δ.

DNA from the recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ was digested with the restriction enzyme Sse8387I, the site was blunt ended with T4 polymerase, and the DNA was cut with the enzyme BSU361. After religation of the virus DNA, the Arif-1 ORF was disrupted. The remaining Arif-1 ORF is out of frame downstream of the Sse8387I site; thus, it encodes only the N-terminal part of Arif-1 with 20 additional amino acids (Fig. 1).

The recombinant viruses Ac-arif-rescue and Ac-arif-3Δ were obtained after transfection of the religated virus DNAs, and the plaques were identified by the loss of LacZ expression.

Antibodies.

The polyclonal anti-Arif antiserum was produced by immunizing rabbits with a 16-amino-acid peptide (NH2-CDIDYRREERESNSR-COOH) coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Eurogentec). The unpurified polyclonal antiserum was used for immunoblotting at a dilution of 1:2,000. Prior to indirect immunofluorescence studies, the polyclonal antiserum was preadsorbed to TN-368 cells by diluting the antiserum 1:10 in PBS-T buffer (140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween) containing approximately 104 TN-368 cells, followed by incubation for 45 min at room temperature and low-speed centrifugation for 5 min at 3,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected, designated precleared anti-Arif serum, then diluted in PBS (1:20), and supplemented with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA).

The mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) B12B5 α-gp64 is directed against a surface epitope of gp64 (11). The MAb clone 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology) was used to detect phosphorylated tyrosine residues.

Immunocytochemistry.

TN-368 cells grown on coverslips were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, followed by permeabilization in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 4 min. After blocking for 30 min in PBS containing 3% BSA (PBS-BSA), the cells on coverslips were floated for 1 h on 50 μl of precleared anti-Arif serum diluted 1:200 or of MAb α-gp64 diluted 1:50 in PBS-BSA. The cells were washed three times in PBS and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse Immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Jackson Laboratory). F-actin was stained with tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated phalloidin as described previously (17). Subsequently, the cells were rinsed several times with PBS and embedded in mounting medium (Citifluor). Specimens were viewed using a Zeiss Axiovert 135 microscope linked to the INTAS digital camera system. A Zeiss LSM4 with Zeiss software was used for confocal imaging, and the images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop 5.2.

Cell extracts and subcellular fractionation.

Uninfected and AcMNPV-infected TN-368 cells were collected by low-speed centrifugation and washed with PBS. Pelleted cells were resuspended in buffer H (10 mM HEPES, 300 mM sucrose, 5.4 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM orthovanadate [pH 7.4]; one proteinase inhibitor cocktail tablet complete [Roche] was added to freshly prepared buffer H) and homogenized by 25 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. After centrifugation for 10 min at 3,000 × g, the pellet was resuspended in buffer H and centrifuged again. The collected supernatants were centrifuged at 23,000 × g for 45 min, and the pellet was resuspended in buffer S (10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.2 mM orthovanadate [pH 7.4]) and designated the crude membrane fraction.

Aliquots of crude membrane fractions were pelleted and resuspended in calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.6], 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2) containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, protease inhibitors, and CIP (10 U; USB). After incubation for 20 min at 37°C, the aliquots were subjected to immunoblot analysis. As mock control, CIP was heat treated for 10 min at 70°C (adapted from reference 7).

Immunoprecipitation.

Aliquots of the crude membrane preparations (15 to 20 μg in a total volume of 200 μl) were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with the antiphosphotyrosine MAb (2.5 μg). The immunocomplexes were precipitated by protein G-agarose (Santa Cruz) for 2 h at 4°C, collected by centrifugation for 1 min at 4,000 rpm, and then washed three times in PBS-T. Pellets were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer (12), boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged for 1 min at 10,000 rpm, and the supernatants were subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblotting.

Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis by (SDS-PAGE) on either 12 or 15% gels (12) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) by blotting for 2 h at 20 V and 4°C in a tank blotter (Peqlab). The membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C in PBS-T containing 5% (wt/vol) milk powder. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer (anti-Arif serum at 1:2,000 or antiphosphotyrosine MAb at 1:500), incubated with the membranes for 1 h at room temperature, and washed three times in PBS-T. Blots were incubated for 1 h with either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit Ig (1:4,000) or sheep anti-mouse Ig (1:2,000) secondary antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Antibody binding was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL or ECLplus system; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RESULTS

Expression of mutated Arif-1 proteins from recombinant viruses.

We have constructed AcMNPV recombinant viruses with deletions in the Arif-1 gene to explore the role of Arif-1 in directing the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton during the early phase of infection.

The recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ, carrying a polyhedrin promoter-lacZ gene cassette in the Arif-1 ORF, was initially generated (Fig. 1). Based on the recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ, the recombinant Ac-arif-3Δ virus with a frameshift in the Arif-1 ORF and the recombinant Ac-arif-rescue virus with a rescued arif-1 ORF and five additional amino acids in frame were constructed (Fig. 1).

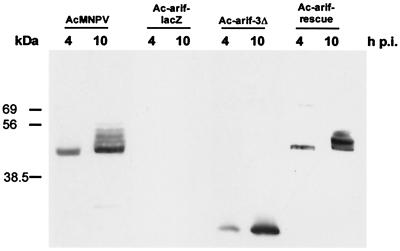

Expression of the mutated Arif-1 proteins was investigated after infection of TN-368 cells with the recombinant viruses Ac-arif-lacZ, Ac-arif-rescue, and Ac-arif-3Δ, and their expression was compared with that of wt Arif-1. After staining with a polyclonal antibody directed against Arif-1, the wt protein was detectable in protein extracts prepared at 4 and 10 h p.i. (Fig. 2). At 4 h p.i., Western blot analysis revealed a single specific protein of approximately 47 kDa, which matches the predicted size of the Arif-1 ORF product. At 10 h p.i., additional bands with decreased mobility were also detected that might indicate modifications of the Arif-1 protein (Fig. 2). As expected, the same pattern was present in Ac-arif-rescue-infected cells at 4 and 10 h p.i. In Ac-arif-3Δ-infected cells, a ∼24-kDa protein was visible, which was more abundant at 10 h p.i. (Fig. 2). This protein represents the N-terminal part of Arif-1 with 20 additional amino acids (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, no protein was detectable in Ac-arif-lacZ-infected cells, although expression of the N-terminal part of Arif-1 with an additional 27 amino acids was predicted. One possible explanation might be insufficient transcriptional termination, since the 3′ end of the truncated Arif-1 ORF is located in the polyhedrin promoter region, which might result in unstable transcripts.

FIG. 2.

Arif-1 expression in wt- and recombinant-virus-infected TN-368 cells. Crude membrane fractions were prepared from TN-368 cells infected with AcMNPV, Ac-arif-lacZ, Ac-arif-3Δ, or Ac-arif-rescue at 4 and 10 h p.i. Samples (10 μg) were loaded on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels and stained with the polyclonal anti-Arif serum. Positions of protein size markers are given on the left.

In summary, three recombinant viruses were generated that lack either the entire Arif-1 protein or the C-terminal portion or that carry the complete Arif-1 ORF with an insertion of five codons (Fig. 1). None of the recombinant viruses showed a significant loss of infectivity in TN-368 and S. frugiperda cells compared to wt viruses (data not shown).

Actin rearrangement after expression of mutated Arif-1 proteins.

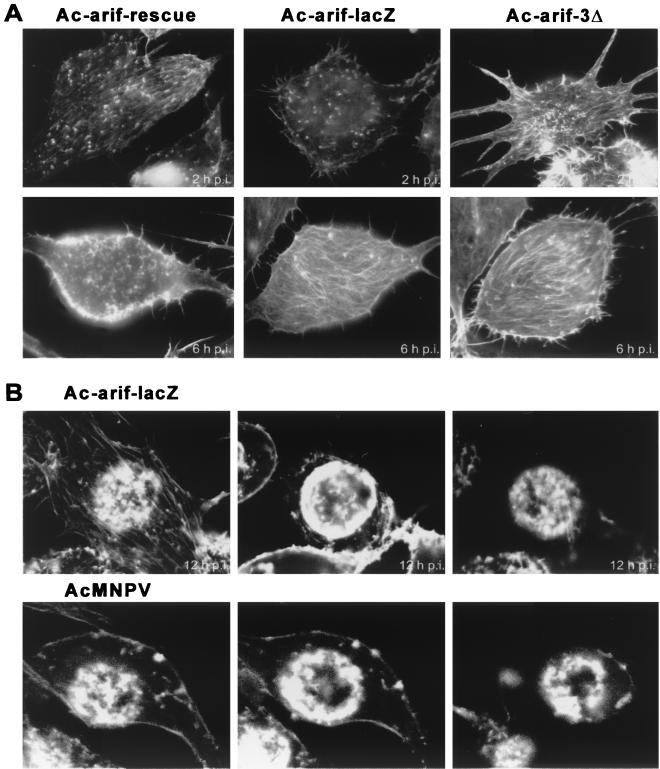

The actin cytoskeleton forms a fine homogeneous network in uninfected TN-368 cells. During the early phase of AcMNPV infection (2 h p.i.), actin cables appear, which are localized at the cell surface and extend into the cytoplasm. The disappearance of these actin cables is accompanied by a second stage of actin rearrangement, observed mainly as actin accumulation at the plasma membrane at 3 to 7 h p.i. (17).

The influence of mutated Arif-1 on the early stages of actin rearrangement was investigated by F-actin staining with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin after infection with the recombinant viruses Ac-arif-lacZ, Ac-arif-rescue, and Ac-arif-3Δ. In general, no difference was observed between wt- and Ac-arif-rescue-infected cells. At 2 h p.i., actin cables were detectable, as in wt virus-infected cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, at 6 h p.i., actin accumulation at the plasma membrane was only visible after infection with Ac-arif-rescue (Fig. 3A). The expression of the N-terminal part of Arif-1 or the complete loss of Arif-1 expression led to the maintenance of actin cables, rendering the cells at 6 h p.i. indistinguishable from those at 2 h p.i. These results demonstrate that Arif-1 expression correlates with actin accumulation at the plasma membrane and that the C-terminal part of Arif-1 is essential. The insertion of codons for five additional amino acids in the middle of the Arif-1 ORF in the recombinant Ac-arif-rescue virus (Fig. 1) did not interfere with the actin rearrangement-inducing function.

FIG. 3.

Actin rearrangement in recombinant-virus-infected TN-368 cells. (A) Cells were infected with the indicated recombinant viruses at a multiplicity of 20 PFU per cell and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 2 h p.i. (first row) and 6 h p.i. (second row). (B) Ac-arif-lacZ and AcMNPV-infected cells were also fixed at 12 h p.i. (third and fourth rows, respectively). By confocal imaging, the same cell is shown at a ventral, medial, and apical (left to right) plane of focus at 12 h p.i. The actin cytoskeleton was visualized with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin.

During the late phases of wt virus infection, actin accumulation at the plasma membrane is followed by the appearance of F-actin in the nucleus (17). Since the Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement was missing in cells infected with recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ or Ac-arif-3Δ, the question arises of whether the recombinant-virus-infected cells still exhibit nuclear F-actin. Therefore, actin staining was performed at 12 h p.i. with the recombinant virus Ac-arif-lacZ, which does not express Arif-1. Confocal imaging revealed the appearance of nuclear F-actin, which formed a ring close to the inner nuclear membrane resembling the nuclear F-actin observed in wt-virus-infected cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast to wt infection, the actin network and the cables were still detectable (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained in Ac-arif-3Δ-infected cells, in which the N-terminal part of Arif-1 was expressed (data not shown). These observations indicate that the presence of nuclear F-actin is independent of Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement. However, Arif-1 expression seems to be an essential prerequisite for the breakdown of the actin network and disappearance of actin cables.

Localization and expression of Arif-1 during the course of infection.

An important issue for understanding the mechanism by which Arif-1 induces actin rearrangement is the identification of its site of action. Therefore, we have investigated the localization of Arif-1 in the course of infection by indirect immunofluorescence using antibodies directed against Arif-1. In wt-virus-infected cells, Arif-1 was observed at the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm as early as 4 h p.i. (data not shown). Arif-1 staining became most prominent at 6 h p.i. (Fig. 4A) and at 12 h p.i. and disappeared at the plasma membrane at 24 h p.i., although some staining was still observed in the cytoplasm (data not shown). The cytoplasmic staining pattern indicated the presence of Arif-1 in vesicular structures.

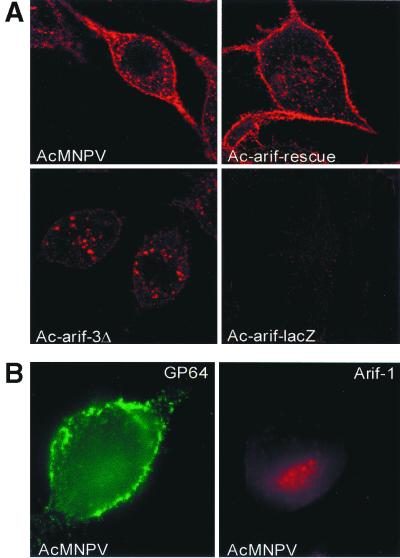

FIG. 4.

Localization of Arif-1 in infected TN-368 cells. Cells infected with AcMNPV or with recombinant virus Ac-arif-rescue, Ac-arif-3Δ, or Ac-arif-lacZ were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 6 h p.i. Arif-1 was visualized by staining with anti-Arif serum and indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. Confocal images are shown (A, first and second rows, red). Cells that were fixed but not permeabilized were stained with either anti-arif serum and Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (B, right panel, red) or with MAb B12B5 α-gp64 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (B, left panel, green).

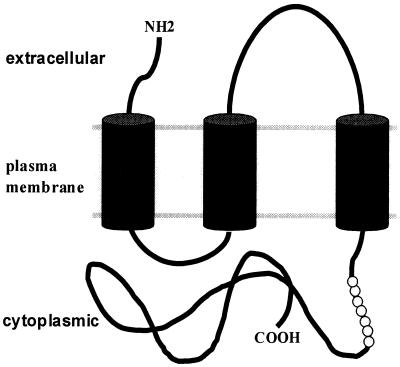

As a control for localization at the plasma membrane, we used MAbs specific for the surface antigen of the viral glycoprotein GP64 (11). GP64 is the major envelope protein of the BV form and is present on the surface of the infected cells, which was confirmed by staining GP64 in nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 4B). In contrast, no significant staining of Arif-1 was observed in nonpermeabilized cells; minor staining of Arif-1 which is only visible in part of the cells might be related to local disruption of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B). Since the anti-Arif-1 serum is directed against a peptide, our results suggest that the epitope recognized by the antibody is localized at the cytoplasmic site (Fig. 1 and 9).

FIG. 9.

Model of Arif-1 plasma membrane localization. Computer analysis of the amino acid sequence (GCG Wisconsin package) predict a signal peptide at the N terminus followed by three transmembrane regions. Arif-1 is shown in the plasma membrane after cleavage of the signal peptide of 35 amino acids. Each transmembrane domain spans about 20 amino acids and is shown as a cylinder. The peptide of 16 amino acids against which the polyclonal Arif antibodies are directed is shown as a string of pearls. It is located at the cytoplasmic region of the C-terminal 200 amino acids.

When cells were infected with the recombinant Ac-arif-rescue virus, the localization of rescued Arif-1 was indistinguishable from that of wt Arif-1 (Fig. 4A). However, after infection with Ac-arif-3Δ, the truncated Arif-1 was observed in vesicular structures, and no specific staining was detectable at the plasma membrane. The Arif-1 staining was missing in cells that were infected with Ac-arif-lacZ (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we conclude that the C terminus of Arif-1 influences the transport and/or anchoring of Arif-1 at the plasma membrane.

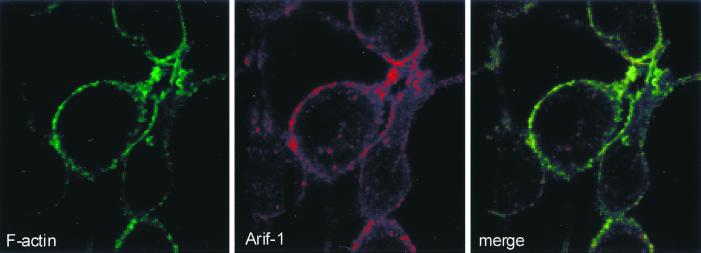

The correlation between the presence of Arif-1 at the plasma membrane and the induction of actin rearrangement indicates that Arif-1 has to be translocated to the plasma membrane in order to exert its activity. This in turn led to the question of whether Arif-1 and F-actin colocalized at the plasma membrane. After costaining cells at 6 h p.i., the merge of the signals indeed indicated colocalization of Arif-1 and F-actin at the plasma membrane (Fig. 5). Whether Arif-1 interacts directly with F-actin or F-actin organizing factors remains to be determined.

FIG. 5.

Colocalization of Arif-1 and F-actin in AcMNPV-infected TN-368 cells. AcMNPV-infected cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 6 h p.i. Double-label immunofluorescence analysis was performed with FITC-conjugated phalloidin (left, green) and with polyclonal anti-Arif serum and Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (center, red). The confocal overlay is shown on the right.

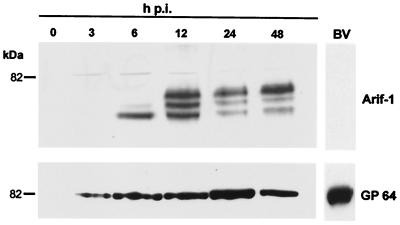

We have examined the time course of Arif-1 expression and the presence of Arif-1 in preparations of BV by Western blot analysis. In contrast to the viral envelope protein GP64, Arif-1 was undetectable in solubilized BV, indicating that Arif-1 is not a structural component of BV (Fig. 6). The Arif-1 protein was not detectable in either cytoplasmic or nuclear protein fractions but only in crude membrane preparations, which is in agreement with the localization of Arif-1 at the plasma membrane and with its association with vesicular structures. As control for the protein fractionation procedure, we stained the membrane-bound glycoprotein GP64, which was also observed exclusively in crude membrane fractions from 3 until 48 h p.i. (Fig. 6). The ∼47-kDa Arif-1 protein was present at 4 h p.i. and increased at 6 h p.i. (Fig. 2, 6, and 7). The observation of delayed early-gene expression compared to major early proteins like PE38, ME53, IE2, and IE1 is in line with our previous finding that the Arif-1 promoter is dependent on the early viral regulator IE1 expression (17). The protein level of Arif-1 was maintained until 12 h p.i. and decreased significantly at 24 and 48 h p.i. (Fig. 6). In addition to the ∼47-kDa Arif-1 protein, a faint band of higher apparent molecular mass was observed at 6 h p.i. and other bands between 12 and 48 h p.i. (Fig. 6). Most likely these higher-molecular-weight proteins represent posttranslationally modified Arif-1. The intensity of the bands with lower mobility was most prominent when the protein extracts were freshly prepared, indicating a labile modification of Arif-1 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Time course of Arif-1 expression in AcMNPV-infected TN-368 cells. Crude membrane fractions were prepared from uninfected TN-368 cells (lane 0) and from AcMNPV-infected TN-368 cells at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h p.i. Protein samples (10 μg) were loaded on SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gels. In addition, purified BV preparations were lysed and analyzed for the presence of Arif-1 and GP64 (lane BV). Gels were stained with the polyclonal anti-Arif serum and, as a control, with MAb B12B5 α-gp64. Position of protein size marker is given on the left.

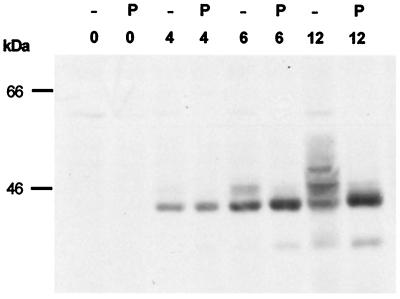

FIG. 7.

Phosphorylation of Arif-1 during AcMNPV infection. Crude membrane fractions were prepared from uninfected TN-368 cells (lanes 0) and from AcMNPV-infected cells at 4, 6, and 12 h p.i. Aliquots were treated with CIP. Samples of untreated (lanes −) and phosphatase-treated (lanes P) fractions were loaded on a SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with the polyclonal anti-Arif serum. Positions of protein size markers are given on the left.

Phosphorylation of Arif-1.

One possible modification is the phosphorylation of Arif-1. When crude membrane fractions were treated with phosphatase prior to Western blot analysis, the slower-migrating Arif-1 proteins were converted into the fastest-migrating Arif-1, suggesting that the higher apparent molecular weight is caused by changes in the phosphorylation state of Arif-1 during the course of infection (Fig. 7).

The prediction of potential phosphorylation sites in the Arif-1 amino acid sequence shows several serine and threonine residues with high probability for a phosphorylation site, which are concentrated at the C-terminal portion of Arif-1. Since putative tyrosine phosphorylation sites were also identified, we performed immunoprecipitation assays with an MAb directed against phosphotyrosine to investigate whether Arif-1 was phosphorylated at tyrosine residues.

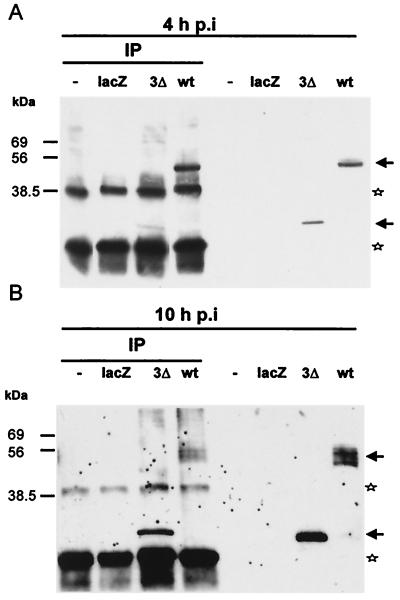

Crude membrane fractions were prepared from wt-virus-infected TN-368 cells and, as a control, from cells infected with either Ac-arif-lacZ or Ac-arif-3Δ. After immunoprecipitation with the MAb directed against phosphotyrosine, staining of the Western blots with anti-Arif serum demonstrated precipitation of the ∼47-kDa Arif-1 from membrane fractions prepared at 4 h p.i. (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, the truncated ∼24-kDa protein that represents the N-terminal portion of Arif-1 was also precipitated by the MAb against phosphotyrosine, indicating that phosphotyrosine residues were present in the first 257 amino acids (Fig. 8A). In protein extracts prepared at 10 h p.i., the antibodies against phosphotyrosine precipitated Arif-1 proteins with apparently higher molecular mass in addition to the ∼47-kDa Arif-1 (Fig. 8B). Solubilization of the membrane fractions with 2% SDS prior to immunoprecipitation showed a slight reduction but not a complete loss of precipitated Arif-1 (data not shown). We conclude from these results that Arif-1 is already tyrosine phosphorylated at 4 h p.i. and that further amino acids may become phosphorylated during the late phase of infection, which would lead to the lower mobility of Arif-1 isoforms in SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

FIG. 8.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Arif-1. Crude membrane fractions were prepared from uninfected TN-368 cells (lanes −) and from cells infected with AcMNPV (lanes wt), Ac-arif-lacZ (lanes lacZ), and Ac-arif-3Δ (lanes 3Δ) at 4 h p.i. (A) and 10 h p.i. (B). Aliquots (15 to 20 μg) were immunoprecipitated with the antiphosphotyrosine MAb (clone 4G10) and loaded on SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gels (lanes IP). For comparison, aliquots of the membrane fractions were also loaded (right panels). Positions of protein size markers are given on the left. The arrows on the right indicate full-size Arif-1, modified forms, and the truncated version. The stars indicate the IgG chains of the antiserum.

DISCUSSION

The sequential actin rearrangement during baculovirus infection suggests specific interactions of the viruses with the actin cytoskeleton that are distinct from the effects that follow the virus-induced breakdown of the cell. How the different steps of actin rearrangement contribute to viral infection, however, is still speculative. The only known baculovirus protein that causes actin rearrangement is Arif-1, whose expression leads to actin polymerization prior to viral replication (17). Our present study demonstrates that the loss of Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement has various effects on the changes of the actin cytoskeleton during the viral infection cycle. While the formation of the early actin cables that follow the release of the nucleocapsids in the cytoplasm was not significantly affected, Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement seems to be a prerequisite for the breakdown of the early cables and the actin network late in infection. In wt-virus-infected cells, the disappearance of Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement at about 12 h p.i. correlated with the appearance of nuclear F-actin. Interestingly, nuclear F-actin still appeared when Arif-1 expression was missing, which suggests that the pathway leading to nuclear F-actin is unrelated to the one inducing the changes in the actin cytoskeleton. Recent work provides evidence that nuclear F-actin is required for morphogenesis of the nucleocapsids (14). However, the underlying mechanism of F-actin accumulation in the nucleus is still open.

To understand how the early protein Arif-1 triggers actin rearrangement, the localization and time course of Arif-1 expression were examined in the permissive insect cell line TN-368. Our results indicate that Arif-1-induced actin polymerization at the plasma membrane relies on the presence of Arif-1 at the site of action. After expression of the N-terminal part, Arif-1 was only localized in the cytoplasm, which correlated with the loss of actin polymerization at the plasma membrane. The colocalization of Arif-1 and F-actin at the plasma membrane further supports the involvement of Arif-1 in a signal transduction pathway that might be based on the direct or indirect interaction of Arif-1 with F-actin organizing factors.

The analysis of the Arif-1 amino acid sequence predicts a signal peptide of about 35 amino acids at the N terminus, followed by three transmembrane regions of about 20 amino acids each. This prediction is in line with our observation that Arif-1 staining is visible at the plasma membrane and in cytoplasmic structures. Taking this together with the results of the indirect immunofluorescence studies, we propose a model that exhibits three transmembrane regions spanning the plasma membrane and a cytoplasmic tail of about 200 amino acids (Fig. 9). Conclusively, the model predicts two epitopes that point to the extracellular space (Fig. 9). The evidence indicating that the C-terminal part of Arif-1 is cytoplasmic emerged from indirect immunofluorescence studies in nonpermeabilized cells, where no significant Arif-1 staining was observed with an antibody that recognized a peptide in the C-terminal part of the protein (Fig. 9). Furthermore, the cytoplasmic localization of the C-terminal 200 amino acids coincides with the functional role of Arif-1 as an inducer of actin polymerization and is in line with the colocalization of Arif-1 and F-actin.

Arif-1 staining at the plasma membrane was detectable until 12 h p.i., when Arif-1-induced actin polymerization started to disappear. Later on, Arif-1 was only visible in cytoplasmic structures. These observations suggest that Arif-1 becomes nonfunctional while it is still present at the plasma membrane. When the Arif-1 protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, multiple bands of higher apparent molecular weight were visible between 12 and 48 h p.i. Phosphatase treatment reversed the change in apparent molecular weight, suggesting that Arif-1 is hyperphosphorylated. Thus, we speculate that Arif-1 becomes nonfunctional by phosphorylation, followed by translocation to the cytoplasm during the late phase of infection. It will be of interest to determine whether cellular or viral kinases are involved. The AcMNPV genome contains two genes, pk1 and pk2, with homology to eukaryotic protein kinases. Enzymatic activity is associated with the gene product of pk1 (16). pk2 encodes a truncated protein kinase homologue and is involved in the reduced phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (6). Since both genes are expressed during the late phases of infection, we treated TN-368 cells with aphidicolin, which blocks viral replication and late-gene expression, to investigate whether the potential viral kinases contribute to the phosphorylation of Arif-1 during the late phase of infection. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the Arif-1 protein pattern after aphidicolin treatment was indistinguishable from the pattern in untreated cells (data not shown). Therefore, the involvement of late viral kinases in Arif-1 phosphorylation is rather unlikely.

In contrast to the late hyperphosphorylated forms, tyrosine phosphorylation of Arif-1 was already detectable during the early phase of infection. Computer analysis predicts several phosphotyrosine residues, which are primarily localized to the N-terminal portion of Arif-1. This prediction is in agreement with our observation that the C-terminally truncated version of Arif-1 is tyrosine phosphorylated. Future experiments will demonstrate which of the residues indeed become phosphorylated. Furthermore, the functional significance of the tyrosine phosphorylation has still to be determined. However, the Arif-1-induced actin polymerization at the plasma membrane and the tyrosine phosphorylation of Arif-1 are reminiscent of signal transduction pathways involved in the control of actin polymerization (9, 15).

The infectivity of the AcMNPV recombinant viruses carrying mutations in the Arif-1 ORF was not significantly altered in cell culture. Three recombinant viruses were generated, one lacking Arif-1, a second expressing the N-terminal part of Arif-1, and a third expressing rescued Arif-1. Sequence analysis revealed an additional insertion in all three recombinant viruses that disrupted ORF22 upstream of the Arif-1 ORF. A contribution of the ORF22 gene product to the virus-induced actin rearrangement in TN-368 cells could be excluded, since the phenotype of the rescued Arif-1 recombinant virus was indistinguishable from that of the wt virus.

In conclusion, Arif-1-induced actin rearrangement seems to play no significant role in the transportation of the virus particles, viral replication, or assembly of BV, at least in the permissive S. frugiperda and TN-368 cells. However, infection of a cell culture mimics only the cellular part of the in vivo infection cycle and neglects the route of infection in the host organism. Thus, it will be of considerable interest to determine whether Arif-1 participates in the process of virus spreading in the various tissues of the larvae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Felicitas Jahnel for technical assistance, Christoph Groten and Andreas Kremer for help with the sequence analysis, Bob Possee for the gift of plasmid pAcRP23-Sse-lacZ, and Loy Volkman for kindly providing the antibodies against GP64. We also thank Kathy Astrahantseff, Brigitte Kisters-Woike, and Markus Plomann for discussions and reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by grant Mo513/9-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by the Köln Fortune Program, University of Cologne.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayres M D, Howard S C, Kuzio J, Lopez-Ferber M, Possee R D. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1994;202:586–605. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blissard G W, Rohrmann G F. Baculovirus diversity and molecular biology. Annu Rev Entomol. 1990;35:127–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.35.010190.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlton C A, Volkman L E. Sequential rearrangement and nuclear polymerization of actin in baculovirus-infected Spodoptera frugiperda cells. J Virol. 1991;65:1219–1227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1219-1227.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlton C A, Volkman L E. Penetration of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus nucleocapsids into IPLB Sf 21 cells induces actin cable formation. Virology. 1993;197:245–254. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cudmore S, Reckmann I, Way M. Viral manipulations of the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Microbiol. 1997;4:142–148. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dever T E, Sripriya R, McLachlin J R, Lu J, Fabian J R, Kimball S R, Miller L K. Disruption of cellular translational control by a viral truncated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2a kinase homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fankhauser C, Reymond A, Cerutti L, Utzig S, Hofmann K, Simanis V. The S. pombe cdc15 gene is a key element in the reorganization of F-actin at mitosis. Cell. 1995;82:435–444. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardiner G R, Stockdale H. Two tissue culture media for production of lepidopteran cells and nuclear polyhedrosis viruses. J Invertebr Pathol. 1975;25:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hink W F. Established insect cell line from the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. Nature. 1970;226:466–467. doi: 10.1038/226466b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keddie B A, Aponte G W, Volkman L E. The pathway of infection of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus in an insect host. Science. 1989;243:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.2648574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lanier L M, Volkman L E. Actin binding and nucleation by Autographa californica M nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology. 1998;243:167–177. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohkawa T, Volkman L E. Nuclear F-actin is required for AcMNPV nucleocapsid morphogenesis. Virology. 1999;264:1–4. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawson T. Protein modules and signalling networks. Nature. 1995;373:573–580. doi: 10.1038/373573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reilly L M, Guarino L A. The pk-1 gene of Autographa californica multinucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus encodes a protein kinase. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2999–3006. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-11-2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roncarati R, Knebel-Mörsdorf D. Identification of the early actin rearrangement-inducing factor gene arif-1 from Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1997;71:7933–7941. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7933-7941.1997. . (Erratum, 72:888–889, 1998.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tjia S T, Carstens E B, Doerfler W. Infection of Spodoptera frugiperda cells with Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. II. The viral DNA and the kinetics of its replication. Virology. 1979;99:399–409. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaughn J L, Goodwin R H, Tompkins G J, McCawley P. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda. In Vitro. 1977;13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]