Abstract

Woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) mutants with core internal deletions (CID) occur naturally in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks, as do hepatitis B virus mutants in humans. We studied the replication of WHV deletion mutants in primary woodchuck hepatocyte cultures and in vivo after transmission to naive woodchucks. By screening 14 wild-caught, chronically WHV-infected woodchucks, two woodchucks, WH69 and WH70, were found to harbor WHV CID mutants. Consistent with previous results, WHV CID mutants from both animals had deletions of variable lengths (90 to 135 bp) within the middle of the WHV core gene. In woodchuck WH69, WHV CID mutants represented a predominant fraction of the viral population in sera, normal liver tissues, and to a lesser extent, in liver tumor tissues. In primary hepatocytes of WH69, the replication of wild-type WHV and CID mutants was maintained at least for 7 days. Although WHV CID mutants were predominant in fractions of cellular WHV replicative intermediates, mutant covalently closed circular DNAs (cccDNAs) appeared to be a small part of cccDNA-enriched fractions. Analysis of cccDNA-enriched fractions from liver tissues of other woodchucks confirmed that mutant cccDNA represents only a small fraction of the total cccDNA pool. Four naive woodchucks were inoculated with sera from woodchuck WH69 or WH70 containing WHV CID mutants. All four woodchucks developed viremia after 3 to 4 weeks postinoculation (p.i.). They developed anti-WHV core antigen (WHcAg) antibody, lymphoproliferative response to WHcAg, and anti-WHV surface antigen. Only wild-type WHV, but no CID mutant, was found in sera from these woodchucks. The WHV CID mutant was also not identified in liver tissue from one woodchuck sacrificed in week 7 p.i. Three remaining woodchucks cleared WHV. Thus, the presence of WHV CID mutants in the inocula did not significantly change the course of acute self-limiting WHV infection. Our results indicate that the replication of WHV CID mutants might require some specific selective conditions. Further investigations on WHV CID mutants will allow us to have more insight into hepadnavirus replication.

Mutations within the core gene of hepatitis B virus (HBV) were often found in chronically HBV-infected patients (3, 5, 8, 21; for a review, see reference 14). HBV core internal deletion (CID) is a common type of mutation (1, 2, 12, 13, 17, 20, 26, 27, 28). In some patients, HBV CID mutants emerged in association with severe liver diseases. For example, HBV CID mutants occurred in renal allograft recipients who suffered from endstage liver diseases (12, 13, 18). CID mutations lead to the expression of truncated, unstable core proteins (24, 29). Thus, HBV CID mutants are defective in replication and require trans-complementation by wild-type virus (22, 29). This fact explains why HBV CID mutants always co-occurred with wild-type virus in patients examined so far. However, our knowledge about the replication of HBV CID mutants in the host is limited. It is also not known whether the presence of HBV CID mutants influences infection in naive hosts, since HBcAg harbors major epitopes of host cellular immune responses within the deleted region (7).

Woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV), a virus genetically closely related to HBV, causes acute and chronic infection in its natural host, the woodchuck (Marmota monax) (9, 10, 11, 25). Particularly, chronically WHV-infected woodchucks develop hepatocellular carcinoma at high frequency (10, 23). Recently, WHV CID mutants were found in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks (4). WHV CID mutants show similar characteristics to HBV CID mutants: (i) they occur often in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks but always coexist with wild-type WHV, and (ii) CIDs are located in the middle of the WHV core gene and lead to truncation of the core protein. Truncated WHV core proteins appear to be unstable, as do truncated HBV core proteins (24, 29). Our findings provide an opportunity to study CID mutants in the woodchuck model system. In the present study, we screened chronically WHV-infected woodchucks for WHV CID mutants. WHV CID mutants were found in 2 of 14 woodchucks. We studied the replication of WHV CID mutants in liver samples and primary hepatocyte cultures prepared from these woodchucks. Further, we examined the infection of naive woodchucks with virus stocks containing WHV CID mutants to clarify the possible influence of CID mutants on the course of WHV infection and WHV-specific immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Woodchucks, sera, and liver samples of woodchucks.

Naive and chronically WHV-infected woodchucks were purchased from North Eastern Wildlife (Ithaca, N.Y.). All woodchucks were tested for WHV surface antigen (WHsAg), anti-WHV core antigen (anti-WHcAg), and anti-WHsAg to determine their status. WHV DNA was detected in serum samples of these woodchucks by spot blot hybridization with a full-length WHV genome probe. Liver and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) samples from woodchucks were taken after euthanasia, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Isolation of DNA from woodchuck sera and liver samples.

Sera (100 μl) were subjected to digestion with proteinase K (0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM Na-EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mg of proteinase K per ml, pH 8.2) and phenol-chloroform extraction. WHV DNA was precipitated with ethanol by standard procedures.

Total DNA from liver samples of chronically WHV-infected woodchucks was extracted with the QIAamp Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, about 25 mg of frozen liver samples was ground to powder in liquid nitrogen by using a mortar and pestle, lysed in 180 μl of lysis buffer, and digested with proteinase K. Samples were then mixed with 210 μl of ethanol and applied to a QIAamp spin column. DNA was bound to the column, washed twice, and eluted by buffers supplied with the kit.

To extract WHV covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), 100 mg of frozen liver samples was ground to powder in liquid nitrogen by using a mortar and pestle and was homogenized with 1 ml of ice-cold Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0. After adding 1 ml of 4% SDS, the mixture was vortexed vigorously to shear cellular DNA. Cellular DNA, proteins, and viral protein-bound DNA were precipitated by adding 0.5 ml of KCl, 2.5 M, to the mixture. The precipitates were sedimented by centrifugation in a Sorvall RT 6000B at 3,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. Supernatants were collected and extracted with phenol. Nucleic acids were recovered by ethanol precipitation.

Encapsidated WHV DNA was extracted as follows. Frozen liver samples (100 mg) were ground to powder in liquid nitrogen by using a mortar and pestle and were homogenized with 1 ml of ice-cold Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0. Homogenate was mixed with 50 μl of 10% NP-40 and incubated on ice for 5 to 30 min. Nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation. Supernatants, after adding magnesium acetate (final concentration, 6 mM) and DNase I (50 μg/ml), were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Then additional reagents were added to adjust to 10 mM EDTA, 10% SDS, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.5 mg of pronase per ml. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 60 min and extracted with phenol. Nucleic acids were recovered by ethanol precipitation.

Amplification of WHV core gene and pre-S1/pre-S2 region by PCR, cloning, and sequence analysis of PCR products.

The WHV core gene (nucleotides [nt] 2021 to 2587) and pre-S1/pre-S2 region (nt 2992 to 338) were analyzed by PCR as described previously (4). The primers were designed according to the WHV genome sequence published by Galibert et al. (9): wc1, 5′ TGG GGC CAT GGA CAT AGA TCC TTA 3′ (nt 2015 to 2038), and wc2, 5′ CAT TGA ATT CAG CAG TTG GCA GAT GG 3′ (nt 2570 to 2597), for the WHV core gene; ps1, 5′ CAG CTA GTG CAA CAT AAT CC 3′ (nt 2976 to 2995), and ps2, 5′ CCT GTA ATC CTG CGA GGA GT 3′ (nt 338 to 319), for the WHV pre-S region. PCR products were visualized on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. Each sample that yielded more than one band was further examined. DNA fragments of interest were purified from the gel with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). These fragments were subjected to cloning into pCRII-Vector (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands). Sequencing of plasmids was performed by a commercial service (MWG Biotech, Munich, Germany).

Nested PCR was used for the amplification of serially diluted DNA preparations extracted from serum samples of woodchuck WH69. The first PCR was run with WhpreC, 5′ TAA ATG CAT GCG ACT TCT GTA ACC A 3′ (nt 1907 to 1931), and wc3, 5′ TTA TGT ACC CAT TGA AGA TCA GCA G 3′ (nt 2605 to 2581). The second PCR was performed with wc1 and wc2. Both PCRs were run over 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C.

Liver perfusion on woodchucks and primary woodchuck hepatocyte cultures.

Liver perfusion was carried out according to the following protocol. Anesthetized woodchucks received an intravenous injection of 2 ml of heparin (104 U/ml). After opening the peritoneum, 400 ml of calcium-free preperfusion solution (Spinner minimal essential medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 0.05% glucose, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], insulin, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 IU of penicillin-streptomycin per ml) were pumped into the liver through a portal vein. Then 400 ml of collagenase medium (Williams medium supplemented with 0.4 mg of collagenase per ml, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM glutamine, 0.05% glucose, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 12 IU of insulin per ml, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 IU of penicillin-streptomycin per ml) was pumped through a portal vein with a flow rate of 20 ml/min. Liver tissues were dissected from the abdominal cavity. Hepatocytes were separated from liver tissue with forceps and a scalpel and were stirred in 100 ml of collagenase medium for an additional 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cell suspensions were filtered through gauze to remove tissue fragments and passed through a 70-μm filter. Hepatocytes were separated from other cells by repeated centrifugation at 50 × g.

Primary woodchuck hepatocytes were seeded in 60-mm plates at a density of 106 per well. Plates were coated with collagen type 1 before use. Hepatocytes were maintained for 7 days in Williams medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 0.05% glucose, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), hydrocortisone, 12.5 μg of inosine per ml, 12 IU of insulin per ml, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 IU of penicillin-streptomycin per ml, and 1% dimethyl sulfoxide. Medium was changed at days 1, 3, and 5.

Analysis of WHV replication intermediates in woodchuck primary hepatocytes.

WHV replication intermediates, encapsidated WHV DNA, and cccDNA were extracted as described in the previous section. Extracted DNA was subjected to Southern blot hybridization or PCR.

Immunohistochemical staining of HCC tissue sections with anti-WHcAg antibody.

Excised liver tissues were immediately fixed in formalin (4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin. Sections of paraffin-embedded tissue were prepared. Polyclonal rabbit antibodies raised to WHcAg were used to detect WHcAg expression in liver tissue. Liver sections were incubated with diluted antibodies (1:100) and stained with DAKO EnVision+ System (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For a control, a parallel section of liver was treated in the same manner, except WHcAg-specific antibodies were replaced by normal rabbit serum.

RESULTS

WHV CID mutants occurred in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks.

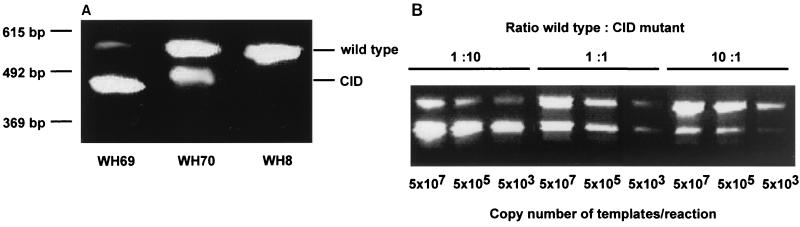

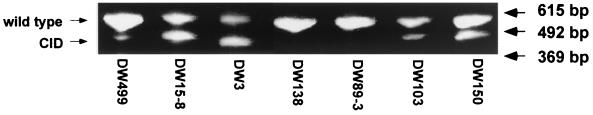

According to a previous study, WHV CID occurs in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks at a frequency of about 10% (4). For further studies on the replication of CID mutants, we screened 14 wild-caught woodchucks with chronic WHV infection to identify individuals carrying WHV CID mutants. WHV DNA was extracted from serum samples from these woodchucks and subjected to PCR for amplification of the WHV core gene (nt 2021 to 2587). WHV CID mutants were found in two woodchucks, WH69 and WH70 (Fig. 1A). The ratios of WHV wild type to CID mutants were about 1:10 in WH69 and 2:1 in WH70. WHV CID persisted in the following 6 months until the sacrifice of WH69 and WH70. The WHV titers in WH69 and WH70 were at about 108 to 109 genome equivalents/ml, as estimated by spot blot hybridization, indicating that the replicative activity of WHV CID mutants in vivo was comparable with that of the WHV wild type. PCR amplification of the WHV pre-S1/pre-S2 region (nt 2992 to 338) was performed with samples from the same 14 woodchucks. No deletion mutant of WHV pre-S was found in these woodchucks (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Identification of WHV CID mutant genomes in serum samples of chronically WHV-infected woodchucks WH69 and WH70. (A) PCR with DNA-extracted serum samples from woodchucks WH69 and WH70. WH8 was a virus stock containing only wild-type WHV. PCR fragments corresponding to the wild-type WHV core gene and deletion mutants are marked wild type and CID, respectively. (B) PCR amplification of WHV wild type and CID mutants in defined ratios of 1:10, 1:1, and 10:1. Templates of WHV wild type and CID mutants were mixed in defined ratios and adjusted to different copy numbers.

To exclude the possibility that PCR led to a selective amplification of wild-type or mutant sequences, cloned fragments containing the wild-type WHV core gene sequence and CID mutations were mixed in different ratios (1:10, 1:1, and 10:1). PCRs were performed with initial template numbers ranging from 5 × 107 to 5 × 103 copies per reaction mixture. In all cases, the wild-type-to-CID ratios in final PCR products remained approximately the same as those in the initial reaction mixtures (Fig. 1B). PCR using linearized plasmids as templets gave the same results (not shown). Therefore, our PCR protocol is appropriate to quantitatively analyze the presence of WHV CID mutants.

WHV population in sera from woodchucks WH69 and WH70.

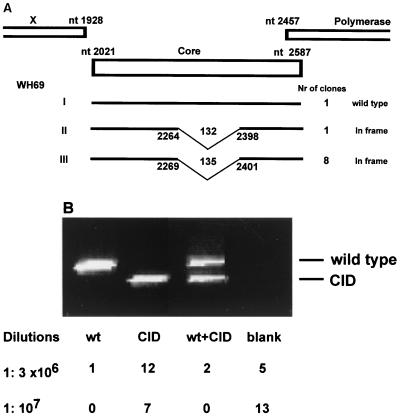

The presence of WHV CID mutants in WH69 and WH70 provided an opportunity to study the replication and infection of such mutants in woodchucks. Prior to further experiments, the CID mutants were characterized in detail. PCR products of the WHV core gene from WH69 were cloned into pCR2.1 vector, and 10 randomly chosen clones were subjected to further sequence analysis. Only one of these clones from WH69 contained the wild-type sequence of the WHV core gene (Fig. 2A). Eight other clones contained a WHV CID mutation of 135 bp at nt 2264 to 2398. Another WHV CID mutation of 132 bp at nt 2269 to 2401 was identified in the remainder. Both WHV CID mutations have been found in other woodchucks in a previous study (4). To conform the results of cloning, we analyzed the ratio of WHV wild type to CID mutants by PCR with diluted DNA preparations from serum samples of WH69. Nested PCR was necessary for the amplification of very small numbers of WHV genomes down to a single copy in diluted samples. Totals of 15 and 7 of 20 individual reactions with 1:3 × 106- and 1:107-diluted samples, respectively, were positive (Fig. 2B). At the dilution of 1:3 × 106, 1 wild type, 12 CID mutants, and 2 mixtures of wild type and CID mutant were detected. Seven CID mutants were identified in nested PCR with 107-diluted samples. These results indicated that the ratio of WHV wild type to CID mutants ranged between 1:7 and 1:8, comparable with results gained by other approaches.

FIG. 2.

Heterogeneity of WHV CID mutants in woodchuck WH69. (A) Analysis of the WHV population in WH69 by the cloning of the PCR product of the WHV core region. The numbering of the nucleotide positions is according to Galibert et al. (9). The positions of CIDs are indicated by broken lines and the nucleotide positions. The numbers on the broken lines indicate the respective length of deletions. Nr, number. (B) Analysis of the WHV population in WH69 by nested PCR with diluted preparations of extracted serum DNA. Samples at dilutions of 1:3 × 106 and 1:107 were subjected to nested PCR. The numbers of WHV wild type (wt), CID mutants, and mixtures of both types (wt+CID) are indicated. Diluted samples resulting in negative PCR are indicated as blank.

The majority of cloned PCR products derived from WH70 had the wild-type WHV core sequence. A CID mutation of 90 bp between nt 2268 and 2357 was found. These results were concordant with our previous finding that genetically different CID mutants coexist together with wild-type WHV in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks.

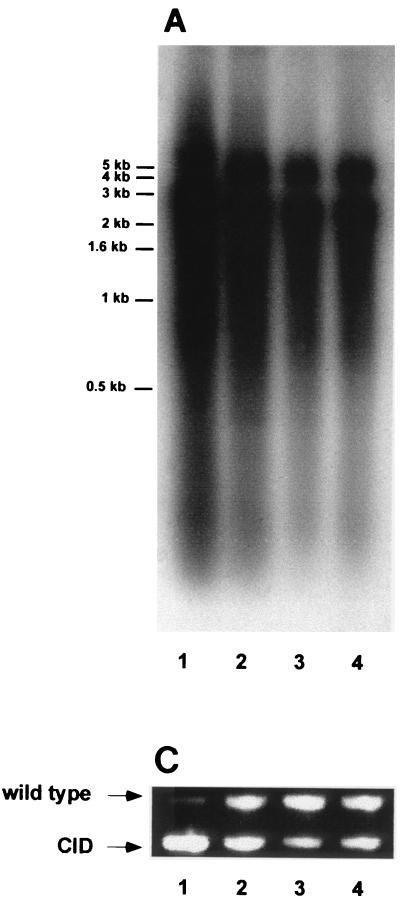

WHV CID mutants in normal and HCC tissues.

To study the replication of WHV CID mutants in liver tissues, woodchuck W69 was sacrificed. An HCC was found at the left lobus of the liver. In a previous work, WHV replication was found to occur in HCC tissues from chronically WHV-infected woodchucks. It is of interest whether WHV wild type and CID mutants may unevenly distribute in normal and HCC tissues. Thus, biopsies from normal liver tissue and HCC tissue were taken to examine the WHV replication and the presence of WHV CID mutants. WHV replication intermediates were detected in total DNA fractions from HCC and liver tissues by Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 3A). An immunohistochemical staining of the WHcAg showed that WHcAg was expressed in cancerous tissues (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that WHV replication also occurred within HCC tissues. The presence of WHV CID mutants in normal and HCC tissues was examined by WHV core-specific PCR. The ratio of WHV wild type to CID mutants in normal tissues was comparable with that in serum samples (Fig. 3C). In contrast, WHV wild type in HCC tissues appeared to be the major part of viral populations. Thus, WHC CID mutants replicated preferentially in normal tissues of WH69 and to a lesser extent in HCC.

FIG. 3.

(A) Detection of WHV replication intermediates in normal woodchuck liver tissues (lane 1) and woodchuck HCC tissues from WH69 (lanes 2 through 4). (B) The immunohistological staining of HCC section with anti-WHcAg antibody. Magnification, ×1,000. (C) WHV core-specific PCR with DNA extracted from normal liver tissues (lane 1) and three different parts of HCC tissues from WH69 (lanes 2 through 4).

HBV CID mutants were reported to occur in patients with HCC (16, 29). To examine the occurrence of WHV CID mutants in HCC tissues, total DNA was extracted from HCC tissues from seven additional woodchucks and was subjected to Southern blot analysis and PCR. Different amounts of WHV replication intermediates were detected in all HCC tissues by Southern blotting (data not shown). WHV core-specific PCR with the same samples revealed that WHV CID mutants were present in five HCC samples (Fig. 4). Three woodchucks, DW499, DW15-8, and DW3, were found to harbor WHV CID mutants in sera and normal liver samples (4). The ratio of WHV CID mutants to wild type was comparable in HCC tissues and normal liver tissues (Fig. 4). No WHV CID mutant was identified in HCC tissues from two other chronically WHV-infected woodchucks. Thus, WHV CID mutants appeared to occur frequently in woodchucks with HCC.

FIG. 4.

Detection of WHV CID mutants in HCC tissues from seven chronically WHV-infected woodchucks. WHV core-specific PCR with DNA extracted from HCC tissues from seven woodchucks is shown.

Replication of WHV wild type and CID mutants in primary hepatocytes.

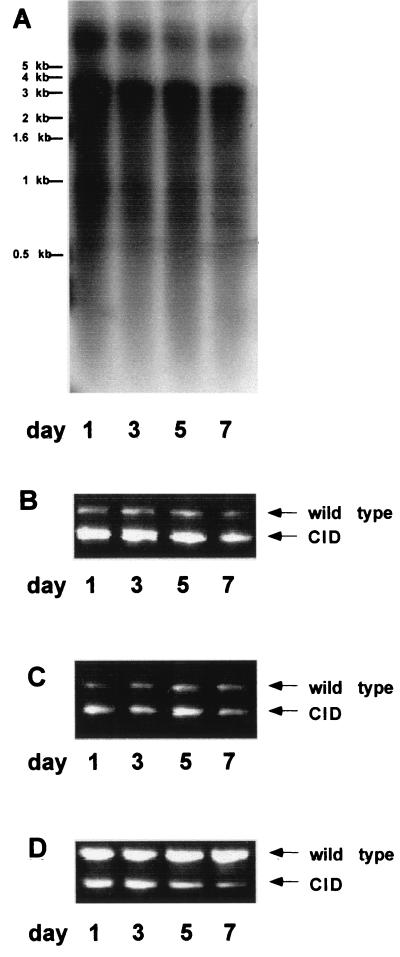

So far, CID mutants were studied in biopsies or in transfected cell lines. It is not possible yet to study the replication of CID mutants dynamically. We took advantage of studying replication of WHV CID mutants in primary hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes were prepared from perfused liver of WH69 and cultured for 7 days. Total WHV replicative intermediates, encapsidated WHV DNA, and WHV cccDNA were extracted from primary hepatocytes at days 1, 3, 5, and 7. WHV replication in primary hepatocytes was examined by detection of WHV DNA in extracted fractions by Southern blot hybridization with a WHV-specific probe.

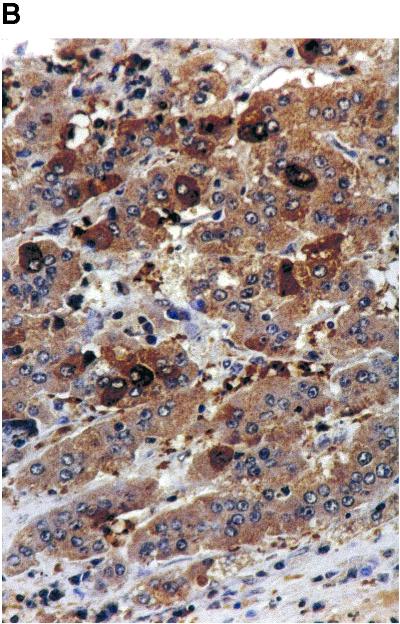

WHV replicative intermediates in primary hepatocytes changed only slightly during the period of culturing (Fig. 5). The ratio between WHV wild-type and CID mutant genomes was assessed by WHV core-specific PCR using total DNA fractions, encapsidated WHV DNA, and WHV cccDNA-enriched fractions. WHV CID mutants remained continuously predominant in total DNA fractions and in fractions of encapsidated WHV DNA. However, the wild-type WHV genome represented the predominant part in cccDNA-enriched fractions. In addition, the ratio of WHV CID mutants to wild type in cccDNA-enriched fractions decreased gradually during the culturing (Fig. 5C). Thus, WHV CID mutants did not accumulate at the level of cccDNA but as encapsidated WHV DNA and WHV genomes in circulating viral particles.

FIG. 5.

Detection of WHV CID mutants in a fraction of WHV replication intermediates and cccDNA in woodchuck primary hepatocytes. (A) WHV replication intermediates detected by Southern blot hybridization. WHV core-specific PCRs were performed with total DNA (B), with encapsidated WHV DNA (C), and with cccDNA-enriched fractions (D) extracted from woodchuck primary hepatocytes.

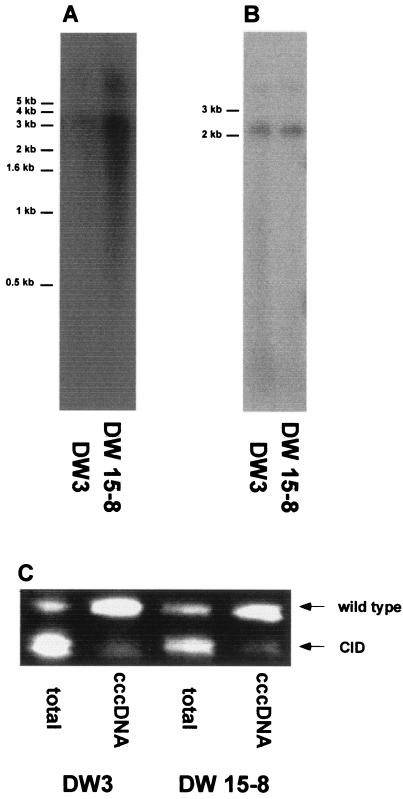

To examine whether cccDNAs of WHV CID mutants accumulated in liver tissues of other chronically WHV-infected woodchucks, total DNA and WHV cccDNA-enriched fractions from liver tissues of two woodchucks, DW3 and DW15-8, were extracted and subjected to core-specific PCR. These woodchucks were found to carry WHV CID mutants as predominant species in serum in a previous study (4), with the same ratios of wild type to CID mutants in total DNA fractions from liver by core-specific PCRs (Fig. 6). CID mutants were present as small fractions in cccDNA-enriched fractions from WH3 and WH15-8.

FIG. 6.

Detection of WHV CID mutants in total DNA and cccDNA-enriched fractions from normal liver tissues from woodchucks DW3 and DW15-8. WHV replication intermediates (A) and cccDNAs (B) were detected by Southern blot hybridization. (C) The presence of WHV CID mutants in the extracted DNA fractions was analyzed by WHV core-specific PCR.

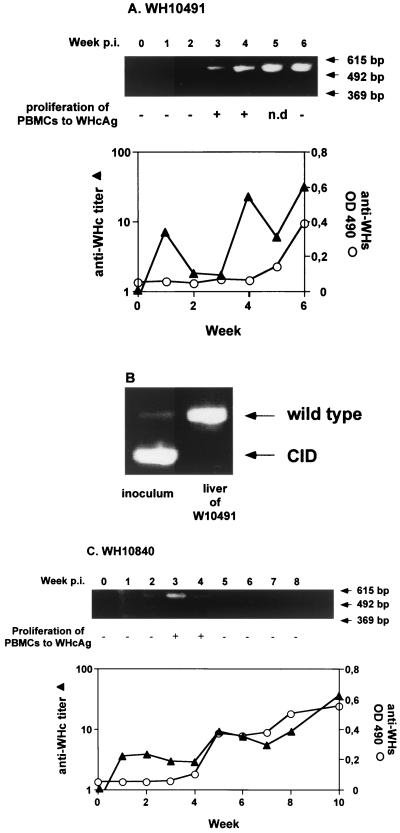

Experimental infection of naive woodchucks with WHV stocks from WH69 and WH70.

CID mutations lead to the loss of important immunological determinants on WHcAg, e.g., a T-cell epitope which is recognized by a large number of outbred woodchucks (19). In addition, WHV CID mutants show a higher replication activity than does the wild-type virus. Thus, the presence of WHV CID mutants in inocula may have an influence on the anti-WHcAg antibody response, WHcAg-specific lymphoproliferative responses, and virus clearance. To clarify this possibility, stocks from WH60 and WH70 were used for inoculation of naive woodchucks. Two naive woodchucks, WH10491 and WH10840, were inoculated by intravenous injection of 100 μl of serum of woodchuck WH69, corresponding to about 107 to 108 WHV genome equivalents. Both woodchucks developed acute self-limiting WHV infection (Fig. 7). In week 4 postinfection (p.i.), anti-WHcAg antibody was detectable in WH10491 (Fig. 7A). Anti-WHsAg antibody appeared in week 6 p.i., which indicated a self-limiting course of WHV infection. WHV DNA was detectable in PCR in week 3 p.i. and persisted to week 6 p.i. Despite the predominance of WHV CID mutants over wild type in the inoculum derived from WH69, WHV CID mutants were not observed in WH10491. WH10491 was sacrificed in week 6, and liver tissues were examined for the presence of WHV CID mutants. Total DNA was extracted from liver tissues from different parts of the liver and was subjected to WHV core gene-specific PCR (Fig. 7B). Only WHV wild type was found in consistence with PCR results gained with serum samples. Similar results were obtained from the infection of WH10840 (Fig. 7C). After carryover anti-WHc antibodies decreased in WH10840, the anti-WHcAg antibody titer raised from week 5 p.i. WHV DNA was detectable only in weeks 3 and 4 p.i., with the appearance of anti-WHsAg at week 5 p.i. The proliferative response to WHcAg was assessed in both woodchucks during the course of infection by in vitro stimulation of woodchuck peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with recombinant WHcAg (rWHcAg) (Fig. 7). PBMC from WH10491 and WH10840 showed proliferative response to rWHcAg at weeks 3 and 4 p.i., as in woodchucks infected by wild-type virus alone (19).

FIG. 7.

Infection of naive woodchucks WH10491 (A) and WH10840 (C) with sera from WH69. OD 490, optical density at 490 nm. The course of WHV infection was monitored by determining anti-WHcAg (anti-WHc titer) and anti-WHsAg (anti-WHs OD 490) antibody levels in woodchuck sera. For the detection of WHV CID, WHV core-specific PCR was performed with DNA extracted from woodchuck sera. The specific lymphoproliferative response of PBMCs to rWHcAg was indicated by a plus if the stimulation index was higher than 3 (19). n.d., not determined. (B) WHV core-specific PCR with DNA extracted from WHV inoculum (WH69) and from liver tissues from woodchuck WH10491 is shown.

Two woodchucks, WH10838 and WH10839, were inoculated with 100 μl of serum from woodchuck WH70. Similar to WH10491 and WH10840, both woodchucks developed acute self-limiting infection. WHV appeared at very low titers at week 3 p.i. and was cleared in week 4 p.i. (data not shown). No deletion mutants in these woodchucks were found by PCR with WHV DNA extracted from sera.

DISCUSSION

WHV CID mutants appeared frequently in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks. In this study, we confirmed results of a previous retrospective study on WHV CID mutants (4). WHV CID mutations from WH69 and WH70 had different sizes and were located in the center of the core gene, consistent with previous results. It is not understood yet how heterogeneous WHV CID mutants emerge and coexist in naturally WHV-infected woodchucks. It is likely that different WHV CID mutants accumulate and replicate at low levels in chronically infected animals. Under some as-yet-unknown conditions, WHV CID mutants replicated rapidly and became predominant in a WHV population.

HBV CID mutants occur in chronically infected patients. HCC was found in some patients harboring HBV CID mutants (16, 29). WHV CID mutants appeared to occur often in woodchucks with HCC. However, the association of the appearance of WHV CID mutants and HCC was not close, as a number of woodchucks with WHV deletion mutants had no HCC. Our results also clearly showed that WHV CID mutants replicated in normal liver tissues and in primary woodchuck hepatocytes. In the liver tumor of WH69, the replication of WHV CID mutants was rather limited.

Our results revealed some interesting features of the replication of WHV CID mutants. Though WHV CID mutants represented significant or even predominant parts of serum viral populations in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks, just a small fraction of cccDNAs, if any, harbored CID mutations. These results might be explained by the instability or slower formation of mutant cccDNAs. The portion of cccDNAs of WHV CID mutants decreased rapidly during the culturing of woodchuck primary hepatocytes. Interestingly, HBV CID mutants in patients disappeared quickly with treatments with lamivudine, while HBV wild type persisted (18). The vulnerability of HBV CID mutants to lamivudine might result from their unstable cccDNA pools. By reduction of HBV replication activity, CID mutants would not be able to maintain sufficient amounts of cccDNAs to persist.

It is still not clear how WHV CID mutants produced large amounts of virions containing mutant genomes with such a small fraction of cccDNAs. We demonstrated previously that CID mutations might lead to an increased expression of WHV polymerase due to the deletion of some of the 11 AUGs in the 5′-untranslated region preceding the WHV polymerase start codon (4). An enhanced expression of WHV polymerase may facilitate the packaging of mutant WHV pregenomic RNAs. Alternatively, CID mutations resulted in a disregulation of transcriptional control that led to an increased production of pregenomic RNAs. Our preliminary data indicate that a large amount of mRNA with CID mutations accumulated in liver tissues from WH69. However, it could not be simply explained by an enhanced transcription of mutant mRNAs. The subsequent steps, like the interaction with polymerase and the packaging into virions, may greatly influence the fate of pregenomic mRNAs. Further investigations should clarify whether such mechanisms are responsible for the emergence of WHV CID mutants. Yuan et al. (28, 29) found that HBV CID mutants have properties of defective interfering particles. HBV CID mutants were enriched if they were cotransfected with HBV wild-type DNA into a human hepatoma cell line. Consistent with these results, Gunther et al. demonstrated that HBV CID mutants show an enhanced replication (15).

WHV CID mutants did not have an apparent influence on acute WHV infections in naive woodchucks. It seems that WHV CID mutants did even not have a chance to propagate in naive woodchucks after experimental infection. WHV CID mutants need the trans-complementation of wild-type viruses for their replication. Since only about 107 WHV genome equivalents were used for our infection experiments, a simultaneous infection of single cells by WHV wild type and mutants is supposed to be a very unlikely event. Thus, WHV CID mutants would disappear in the early phase of an acute infection due to the lack of trans-complementation. The replication of CID mutants might be maintained in naive woodchucks if a sufficient part of hepatocytes are coinfected with wild-type and mutant viruses by a high-titer inoculum. An additional reason would be the lack of appropriate selective conditions in naive woodchucks which favor the replication of WHV CID mutants. Such selective conditions for CID mutants are not defined so far. Our experiments demonstrated that naive woodchucks developed immune responses to WHV proteins after infection with WHV stocks containing WHV CID mutants and efficiently cleared WHV. HBV CID mutants have consistently not been detected in acutely infected patients so far or been found in an association with serious consequences in acute infections. The role of HBV CID mutants for pathogenesis in chronic HBV infection remains to be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Hans Will for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Ulrick Protzer and Ulla Schultz for technical advice.

This work was supported by grants of German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung to M.R. and M.L. (BMBF, 01 KI 9862).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackrill A M, Naoumov N V, Eddleston A L, Williams R. Specific deletions in the hepatitis B virus core open reading frame in patients with chronic active hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 1993;41:165–169. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akarca U S, Lok A S. Naturally occurring core-gene-defective hepatitis B viruses. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1821–1826. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aye T T, Uchida T, Becker S O, Hirashima M, Shikata T, Komine F, Moriyama M, Arakawa Y, Mima S, Mizokami M, Lau J Y N. Variation of hepatitis B virus precore/core gene sequence in acute and fulminant hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1281–1287. doi: 10.1007/BF02093794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botta A, Lu M, Zheng X, Kemper T, Roggendorf M. Naturally occurring woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) deletion mutants in chronically WHV-infected woodchucks. Virology. 2000;277:226–234. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehata T, Omata M, Yokosuka O, Hosoda K, Ohto M. Variations in codons 84–101 in the core nucleotide sequence correlate with hepatocellular injury in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Investig. 1992;89:332–338. doi: 10.1172/JCI115581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feitelson M A. Biology of hepatitis B virus variants. Lab Investig. 1994;71:324–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrari C, Penna A, Bertoletti A, Fiaccadori F. Cell mediated immune response to hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid antigen. Arch Virol Suppl. 1993;8:91–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9312-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiordalisi G, Primi D, Tanzi E, Magni E, Incarbone C, Zanetti A R, Cariani E. Hepatitis B virus C gene heterogeneity in a familial cluster of anti-HBc negative chronic carriers. J Med Virol. 1994;42:109–114. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galibert F, Chen T N, Mandart E. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned woodchuck hepatitis virus genome: comparison with the hepatitis B virus sequence. J Virol. 1982;41:51–65. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.1.51-65.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerin J L. Experimental WHV infection of woodchucks: an animal model of hepadnavirus-induced liver cancer. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1990;25(Suppl. 2):38–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02779926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girones R, Cote P J, Hornbuckle W E, Tennant B C, Gerin J L, Purcell R H, Miller R H. Complete nucleotide sequence of a molecular clone of woodchuck hepatitis virus that is infectious in the natural host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1846–1849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunther S, Li B C, Miska S, Kruger D H, Meisel H, Will H. A novel method for efficient amplification of whole hepatitis B virus genomes permits rapid functional analysis and reveals deletion mutants in immunosuppressed patients. J Virol. 1995;69:5437–5444. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5437-5444.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunther S, Baginski S, Kissel H, Reinke P, Kruger D H, Will H, Meisel H. Accumulation and persistence of hepatitis B virus core gene deletion mutants in renal transplant patients are associated with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 1996;24:751–758. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunther S, Fischer L, Pult I, Sterneck M, Will H. Naturally occurring variants of hepatitis B virus. Adv Virus Res. 1999;52:25–137. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunther S, Piwon N, Jun M, Iwanska A, Schmitz H, Will H. Enhanced replication contributes to enrichment of hepatitis B virus with a deletion in the core gene. Virology. 2000;273:286–299. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosono S, Tai P C, Wang W, Ambrose M, Hwang D, Yuan T T, Peng B H, Yang C S, Lee C S, Shih C. Core antigen mutations of human hepatitis B virus in hepatomas accumulate in MHC class II-restricted T cell epitopes. Virology. 1995;212:151–162. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marinos G, Torre F, Gunther S, Thomas M G, Will H, Williams R, Naoumov N V. Hepatitis B virus variants with core gene deletions in the evolution of chronic hepatitis B infection. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:183–192. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meisel H, Preikschat P, Reineke P, Hocher B, Budde K, Bechstein W O, Neuhaus P, Kruger D H, Neumayer H H. Disappearance of hepatitis B virus core deletion mutants and successful combined kidney/liver transplantation in a patient treated with lamivudine. Transplant Int. 1999;12:283–287. doi: 10.1007/s001470050225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menne S, Maschke J, Tolle T K, Lu M, Roggendorf M. Characterization of T-cell response to woodchuck hepatitis virus core protein and protection of woodchucks from infection by immunization with peptides containing a T-cell epitope. J Virol. 1997;71:65–74. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.65-74.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miska S, Gunther S, Vassilev M, Meisel H, Pape G, Will H. Heterogeneity of hepatitis B virus C-gene sequences: implications for amplification and sequencing. J Hepatol. 1993;18:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Mayumi M. Defective mutants of hepatitis B virus in the circulation of symptom-free carriers. Jpn J Exp Med. 1987;57:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto H, Wang Y, Tanaka T, Machida A, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Trans-complementation among naturally occurring deletion mutants of hepatitis B virus and integrated viral DNA for the production of viral particles with mutant genomes in hepatoma cell lines. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:407–414. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-3-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popper H, Roth L, Purcell R H, Tennant B, Gerin J L. Hepatocarcino-genicity of woodchuck hepatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:866–870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preikschat P, Borisova G, Borschukova O, Disler A, Mezule G, Grens E, Krüger D H, Pumpens P, Meisel H. Expression, assembly competence and antigenic properties of hepatitis B virus core gene deletion variants from infected liver cells. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1777–1788. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-7-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roggendorf M, Tolle T K. The woodchuck: an animal model for hepatitis B virus infection in man. Intervirology. 1995;38:100–112. doi: 10.1159/000150418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchida T, Aye T T, Shikata T, Yano M, Yatsuhashi H, Koga M, Mima S. Evolution of the hepatitis B virus gene during chronic infection in seven patients. J Med Virol. 1994;43:148–154. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakita T, Kakumu S, Shibata M, Yoshioka K, Ito Y, Shinagawa T, Ishikawa T, Takayanagi M, Morishima T. Detection of pre-C and core region mutants of hepatitis B virus in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:1793–1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI115500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan T T, Lin M H, Chen D-S, Shih C. A defective interference-like phenomenon of human hepatitis B virus in chronic carriers. J Virol. 1998;72:578–584. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.578-584.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan T T, Lin M H, Qiu S M, Shih C. Functional characterization of naturally occurring variants of human hepatitis B virus containing the core internal deletion mutation. J Virol. 1998;72:2168–2176. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2168-2176.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]