Abstract

Herein, we report structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies to develop novel tricyclic M4 PAM scaffolds with improved pharmacological properties. This endeavor involved a “tie-back” strategy to replace a 5-amino-2,4-dimethylthieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carboxamide core, which led to the discovery of two novel tricyclic cores. While both tricyclic cores displayed low nanomolar potency against both human and rat M4 and were highly brain-penetrant, the 2,4-dimethylpyrido[4′,3′:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine tricycle core provided lead compound, VU6016235, with an overall superior pharmacological and drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK) profile, as well as efficacy in a preclinical antipsychotic animal model.

Keywords: Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR), Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 4 (M4), Positive allosteric modulator (PAM), Structure−activity relationship (SAR), Schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) are G protein-coupled receptors that have been linked to a variety of central nervous system functions, including cognition, motor control, and sleep–wake architecture.1 Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 4 (M4) positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) have gained interest as a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of behavioral and cognitive disturbances associated with both schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as well as other neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD).2−8 Xanomeline, an M1/M4-preferring agonist, was evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of AD and schizophrenia. Unfortunately, adverse cholinergic side effects, associated with a lack of receptor subtype selectivity, halted xanomeline’s clinical development. Nevertheless, data obtained from these trials further validated the muscarinic cholinergic system as a treatment for the psychosis and behavioral disturbances observed in both Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia patients.9,10 To overcome these side effects, Karuna Therapeutics (acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb) developed KarXT, which coadministers xanomeline with a pan-selective peripheral mAChR antagonist (trospium chloride) to combat the adverse events associated with xanomeline administration alone (Figure 1).11 The New Drug Application (NDA) for KarXT was accepted for review by the FDA in late 2023.12 Recently, a selective M4 PAM was shown to not only be efficacious in preclinical assays but also exhibited fewer and less severe adverse cholinergic-related side effects when compared to rats treated with xanomeline.13 Thus, data suggest that development of a receptor subtype-selective M4 PAM could result in improved safety profiles. Emraclidine (CVL-231), a selective M4 PAM developed by Cerevel Therapeutics, is currently undergoing clinical trials (Figure 1).14−20

Figure 1.

Structures of clinically advanced M4-targeting therapeutics.

Our lab has heavily focused on developing novel, selective M4 PAM chemotypes bereft of the traditional β-amino carboxamide moiety historically believed to be essential for M4 PAM activity (Figure 2, dashed circle).21−27 This key pharmacophore gave rise to M4 PAMs with poor solubility, species potency discrepancies, and poor brain exposure.28−37 Most recently, our laboratory disclosed a novel 5,6,6-tricyclic scaffold and a novel 6,5,6-tricyclic scaffold that still afforded potent and CNS-penetrant M4 PAMs (Figure 2, VU6007215 and VU6017649).24,25 To identify additional novel M4 PAM chemotypes, we elected to further explore these tricyclic scaffolds. An historic β-amino carboxamide-containing M4 PAM (4), developed by the Capuano laboratory, formed the base of our novel tricycles.38 This exercise resulted in the discovery of a novel M4 PAM chemotype containing a 7,9-dimethylthieno[2,3-d:4,5-d′]dipyrimidine core, 5. Further exploration revealed a second, novel, tricyclic M4 PAM chemotype containing a 2,4-dimethylpyrido[4′,3′:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine core, 6. This body of work details the development of these two novel M4 PAM chemotypes.

Figure 2.

Exploration of novel tricyclic cores as M4 PAMs revealed two unique M4 PAM tricyclic chemotypes: 7,9-dimethylthieno[2,3-d:4,5-d′]dipyrimidine core (5) and 2,4-dimethylpyrido[4′,3′:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine core (6).

Results and Discussion

The synthesis of tricyclic core 5 began with reacting commercially available acyl chlorides 7, 3-aminocrotonitrile (8), and ammonium thiocyanate to afford the tetra-substituted pyrimidine 9 (Scheme 1). Similar to published protocols, treatment with 2-chloroacetamide (10) and potassium carbonate followed by irradiation in a microwave reactor generated carboxamide 11.39 Treatment of 11 with trimethylorthoformate under heat afforded pyrimidone intermediate 12. Pyrimidone 12 was then converted into chloride 13 with POCl3, which then readily underwent nucleophilic aromatic substitution with a variety of amines to yield desired analogues 14. For this exercise, we decided to forego exploring amino azetidines of past M4 PAMs because of their potential metabolic instability.40 Instead, we focused on examining small aliphatic amines, which typically provided potent M4 PAMs, as well as substituted benzylamines, which could aid in increasing solubility.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of M4 PAM Analogues 14.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 8, NH4SCN, 1,4-dioxane, 110 °C, 2 h, 46%; (b) 10, K2CO3, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), microwave-irradiated at 60 °C for 30 min, then microwave-irradiated at 100 °C for 1 h, 43%; (c) CH(OEt)3, 150 °C, 3 h, 99%; (d) POCl3, TEA, 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE), 110 °C, 3 h, 81%; (e) amine, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), NMP, 60 °C for 2 h or microwave-irradiated at 100 °C for 10 min, 30–77%.

Select analogues 14 were screened against human M4 (hM4) to determine EC50 values with results highlighted in Table 1. These results emphasize the importance of the amine tail on potency. In the context of the 7,9-dimethylthieno[2,3-d:4,5-d’]dipyrimidine core (5), the benzyl amine-containing analogues 14j and 14k both have hM4 EC50 values > 1 μM. However, several of the small aliphatic amine tails provided compounds with hM4 EC50 values < 500 nM (14g, hM4 EC50 = 290 nM; 14h, hM4 EC50 = 100 nM; and 14i, hM4 EC50 = 160 nM). It was noticed that minor modifications, such as fluorine substitutions on the pyrrolidine (14e vs 14g), led to a 2.2-fold loss in potency. Moreover, removal of the oxygen from the morpholine analogue 14b (hM4 EC50 = 5.6 μM) to give the piperidine analogue 14a (hM4 EC50 > 30 μM) resulted in a loss of activity. Additionally, substituting the 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptane tail of 14c (hM4 EC50 = 1.6 μM) with the 6,6-difluoro-2-azaspiro[3.3]heptane tail of 14h (hM4 EC50 = 100 nM) resulted in a 16-fold increase in functional human M4 potency. Interestingly, we also observed an 11-fold loss of potency when comparing the pyridine predecessor compound VU6007215 (Figure 1; hM4 EC50 = 144 nM) to the pyrimidine compound 14c. One could speculate that this result is due to the difference in the tricyclic cores; however, other amine tails were nearly equipotent [e.g., pyrrolidine (14g)].25 These results reiterate the importance the amine tail can have on potency, particularly in combination with different tricycles.

Table 1. Structures and Activities for Analogues 14.

Calcium mobilization assays with hM4/Gqi5-CHO cells were performed in the presence of an EC20 fixed concentration of acetylcholine. EC50 values for hM4 represent at least one experiment performed in triplicate.

We next turned our attention to evaluating the relevance of the pyrimidine nitrogen at the 5-position by synthesizing analogues 22 and 23. Previously, conversion of this pyrimidine ring into a pyridine ring was not detrimental to hM4 activity; rather, several analogues displayed increased potency.41 To determine if this trend proved true for our current scaffold, we synthesized analogues with the tricyclic core 6. The synthesis was accomplished by first treating intermediate 9b with ethyl 2-chloroacetate (15) and sodium carbonate to generate carboxylate 16 (Scheme 2). A copper-catalyzed Sandmeyer reaction gave bromide 17, which could then undergo Suzuki–Miyaura coupling with 1,3,2-dioxaborolane 18 to afford carboxylate 19. In a two-step process, intermediate 19 was first treated with TFA and heat to generate a pyranone intermediate that was further transformed in the presence of NH4OH and heat to yield pyridinone 20. Treatment with POCl3 yielded chloride 21, which could readily undergo nucleophile aromatic substitution to generate desired analogues 22. Alternatively, chloride 21 could be subjected to an iron-catalyzed Kumada coupling with various Grignard reagents to afford analogues 23.42

Scheme 2. Synthesis of M4 PAM Analogues 22 and 23.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 8, NH4SCN, 1,4-dioxane, 110 °C, 2 h, 21–42%; (b) 15, Na2CO3, DMF, 45 °C, 3 h, 52–91%; (c) CuBr2, tBuONO, acetonitrile (ACN), 1 h, 40–75%; (d) 18, Cs2CO3, Pd(dppf)Cl2, 1,4-dioxanes/H2O (10:1), 80 °C, 18 h, 44–76%; (e) (i) TFA, 120 °C, 2 h; (ii) NH4OH, 100 °C, 4.5 h, 30–88% over two steps; (f) POCl3, microwave-irradiated at 120 °C, 30 min, 13–92%; (g) aliphatic amine, DIEA or K2CO3, NMP, microwave-irradiated at 120–180 °C, 0.5–2 h, 8–20%; (h) benzyl amine, Pd2(dba)3, Xantphos, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, 110 °C, 6–18 h, 14–51%; (i) R2MgCl, Fe(acac)3, THF/NMP (5:1), 1–18 h, 31–41%.

Select analogues 22 and 23 were screened against hM4 to determine potency with results highlighted in Table 2. It was evident that 2,4-dimethylpyrido[4′,3′:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine core (6) provided a boost in functional human hM4 potency. For instance, comparing the benzyl amine tail analogues 22g (hM4 EC50 = 140 nM) and 22j (hM4 EC50 = 170 nM) to 14j (hM4 EC50 = 1.3 μM) and 14k (hM4 EC50 = 1.2 μM) resulted in a 9-fold and 7-fold increase in EC50, respectively. This trend was also observed with small aliphatic groups. Comparing analogue 22k (hM4 EC50 = 73 nM) to 14g (hM4 EC50 = 290 nM) and 22f (hM4 EC50 = 33 nM) to 14e (hM4 EC50 = 640 nM) resulted in a 4-fold and 19-fold increase in EC50, respectively. Most notable was the potency difference in the pyrrolidine analogues 22e (hM4 EC50 = 73 nM) and 14a (hM4 EC50 > 30 μM). Taken together, these data suggest that the basicity of the nitrogen at the 7-position plays a key role in hM4 PAM potency and may function as a critical H-bond acceptor, while the nitrogen at the 5-position is not essential for activity.

Table 2. Structures and Activities for Analogues 22 and 23.

Calcium mobilization assays with hM4/Gqi5-CHO cells were performed in the presence of an EC20 fixed concentration of acetylcholine. EC50 values for hM4 represent at least one experiment performed in triplicate.

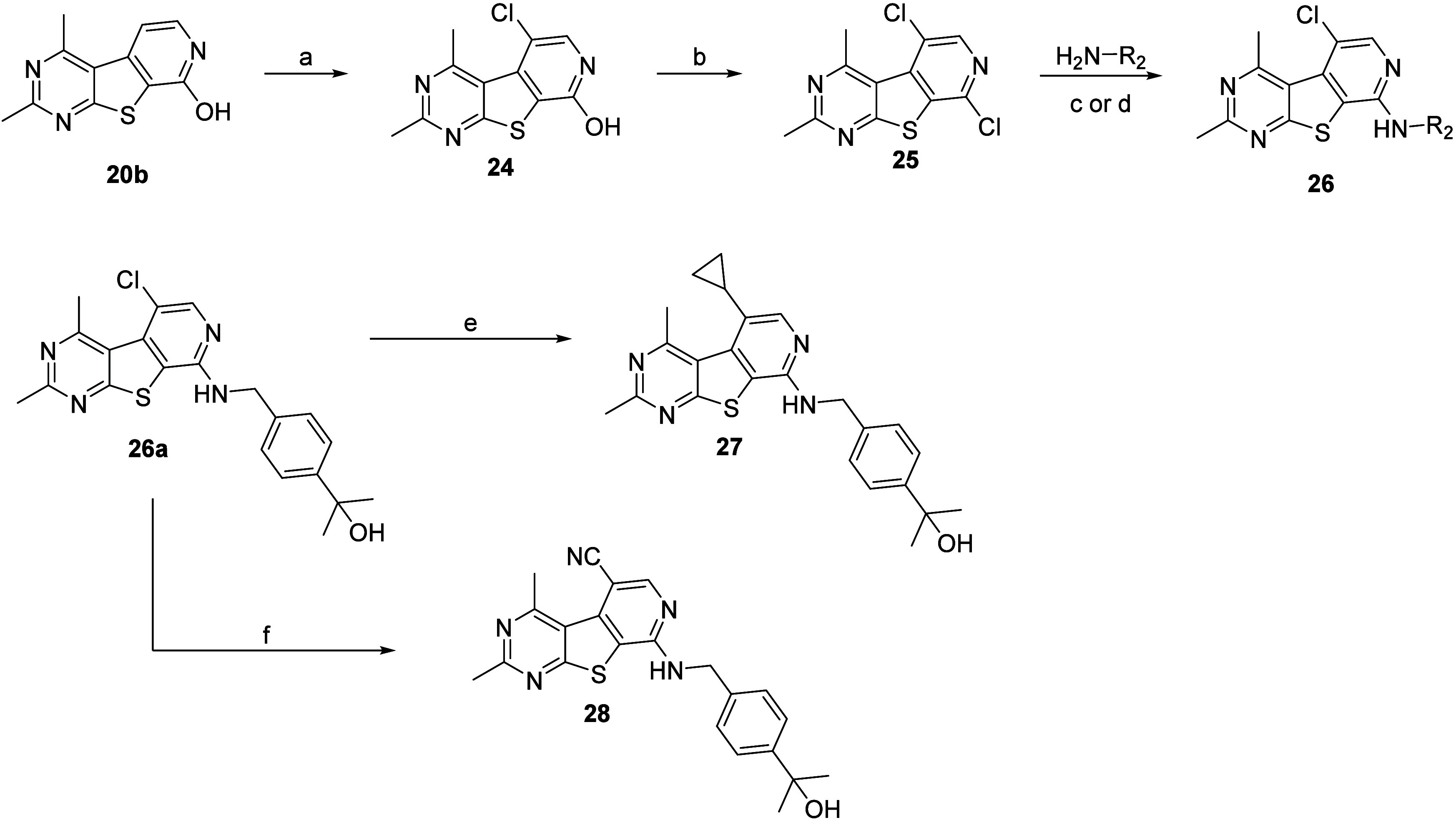

We next wanted to explore various substitutions on the pyridine ring of the tricyclic core 6 to expand upon our SAR studies, as well as elucidate the spatial constraints of the binding pocket. Being para to the amine linkage and, thus, a potential site of metabolism, we chose to explore substitutions at the 5-position of the tricyclic ring (R2). The preparation of analogues 27 and 28 began with chlorinating pyridinone 20b in the presence of N-chlorosuccinimide to give intermediate 24 (Scheme 3). Treatment with POCl3 afforded dichloride 25, which then underwent either a nucleophilic aromatic substitution or a Buchwald–Hartwig amination to generate analogues 26. Analogue 26a was further derivatized utilizing Suzuki–Miyaura coupling conditions to yield analogue 27. Alternatively, analogue 26a was subjected to palladium-catalyzed cyanation to afford analogue 28. We decided to focus mainly on analogues containing the 2-[4-(aminomethyl)phenyl]propan-2-ol tail as this would aid in solubility, as well as the small aliphatic pyrrolidine tail for comparison.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of M4 PAM Analogues 26, 27, and 28.

Reagents and conditions: (a) N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS), DMF, 18 h, 55%; (b) POCl3, microwave-irradiated at 150 °C, 1 h, 45%; (c) pyrrolidine, DIEA, NMP, microwave-irradiated at 150 °C, 30 min, 15%; (d) 2-[4-(aminomethyl)phenyl]propan-2-ol, Pd2(dba)3, Xantphos, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, microwave-irradiated at 130 °C, 1 h, 29%; (e) cyclopropylboronic acid, Cs2CO3, Pd(dppf)Cl2, 1,4-dioxanes/H2O (10:1), microwave-irradiated at 110 °C, 30 min, 11%; (f) Zn0, Zn(CN)2, NiCl2, dppf, 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP), ACN, 80 °C, 2 h, 43%.

Select analogues 22, 26, 27, and 28 were screened against hM4 to determine potency with results highlighted in Table 3. It was evident that substitutions larger than methyl at the R1 position were tolerated; however, a decrease in the EC50 was observed. In fact, an increase in steric bulk [22p (ethyl) < 22o (cyclopropyl) < 22n (isobutyl)] coincided with more dramatic reductions in activity (4.0-fold, 9.3-fold, >66-fold decrease, respectively). This was also observed with the pyrrolidine analogue 22q (>13-fold loss of potency). Similarly, substitutions at the 5-position of the ring (R2) also led to a loss of potency (analogues 26a, 26b, 27, and 28).

Table 3. Structures and Activities for Analogues 22, 26, 27, and 28.

Calcium mobilization assays with hM4/Gqi5-CHO cells were performed in the presence of an EC20 fixed concentration of acetylcholine. EC50 values for hM4 represents at least one experiment performed in triplicate.

Of these compounds, 14h, 14i, 22e, 22f, 22g, 22j, and 22k were advanced into a battery of in vitro drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK) assays and our standard rat plasma-to-brain level (PBL) cassette paradigm (Table 4). These compounds were chosen to move forward based on their hM4 potency (EC50 < 190 nM), as well as their chemical diversity across subseries. In regards to physicochemical properties, these analogues all possessed molecular weights less than 400 Da and desirable topological polar surface area (TPSA) (<80 Å) with 14h, 14i, 22e, 22f, and 22k having the most attractive CNS xLogP values (2.52–3.68).43,44 Of the analogues tested, several (14i, 22e, 22f, 22j, and 22k) displayed high predicted hepatic clearance in both human and rat on the basis of microsomal CLint data (rat CLhep ≥ 46 mL/min/kg; human CLhep ≥ 15 mL/min/kg). These analogues were not progressed forward because of their high predicted hepatic clearance in rat and/or human. By contrast, analogues 14h and 22g display moderate human and rat predicted hepatic clearance on the basis of microsomal CLint data (rat CLhep of 37–44 mL/min/kg; human CLhep of 12–14 mL/min/kg).

Table 4. In Vitro DMPK and Rat PBL Data for Select Analogues 14 and 22.

| property | 14h | 14i | 22e | 22f | 22g | 22j | 22k |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VU6015976 | VU6015368 | VU6016233 | VU6017369 | VU6016235 | VU6016234 | VU6016225 | |

| MW | 347.39 | 297.38 | 298.41 | 320.36 | 378.49 | 368.43 | 284.38 |

| xLogP | 3.06 | 2.52 | 3.68 | 3.45 | 4.43 | 4.23 | 3.23 |

| TPSA | 54.8 | 54.8 | 41.9 | 41.9 | 70.9 | 59.9 | 41.9 |

| in vitro pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters | |||||||

| CLint (mL/min/kg), rat | 121 | 1048 | 3444 | 1518 | 78 | 386 | 3055 |

| CLhep (mL/min/kg), rat | 44 | 66 | 69 | 67 | 37 | 59 | 68 |

| CLint (mL/min/kg), human | 45 | 177 | 134 | 148 | 26 | 50 | 124 |

| CLhep (mL/min/kg), human | 14 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 12 | 15 | 18 |

| rat fu,plasmaa | 0.132 | 0.048 | 0.019 | 0.043 | 0.024 | 0.014 | 0.038 |

| human fu,plasmaa | 0.035 | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.023 |

| rat fbraina | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.007 |

| brain distribution (0.25 h) (SD rat; 0.2 mg/kg IV) | |||||||

| Kp, brain:plasmab | 5.07 | 7.27 | 7.77 | 8.33 | 1.14 | 1.69 | 18.6 |

| Kp,uu, brain:plasmac | 1.27 | 1.82 | 1.64 | 2.91 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 3.43 |

fu = fraction unbound; equilibrium dialysis assay; brain = rat brain homogenates.

Kp = total brain to total plasma ratio.

Kp,uu = unbound brain (brain fu × total brain) to unbound plasma (plasma fu × total plasma) ratio.

All compounds tested had low-to-moderate rat plasma protein binding (rat fu,plasma = 1.5–13.2%). Analogue 22e was highly bound to human plasma protein (human fu,plasma < 1%), while all other analogues analyzed displayed moderate human plasma protein binding profiles (human fu,plasma = 1.0–3.5%). Analogues 22e, 22j, and 22k were highly bound to rat brain homogenate (fu,brain < 1%). Conversely, analogues 14h, 14i, 22f, and 22g were moderately bound to rat brain homogenate (fu,brain = 1.2–3.3%). All compounds tested achieved acceptable CNS penetration (Kp ≥ 1) and unbound brain to unbound plasma ratios (Kp,uu ≥ 0.76). Because of their superior DMPK profiles, 14h and 22g were screened against rat M4 (rM4) to ensure there was no appreciable species differences in M4 activity.46 Both analogues were potent against rM4 (14h, rM4 EC50 = 380 nM; 22g, rM4 EC50 = 42 nM) and minor species differences were within the acceptable range (2–3.5-fold); however, 22g was 9-fold more potent against rM4 than 14h. Thus, 22g (VU6016235) was selected for further evaluation in an array of in vitro and in vivo experiments.

When evaluated, VU6016235 displayed high subtype selectivity across the mAChRs (M1, M3, and M5 = inactive; M2 = 148-fold selectivity) and was highly brain-penetrant with a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux ratio of 1.5 (Table 5). Additionally, VU6016235 displayed an excellent cytochrome P450 (CYP450) inhibition profile with IC50 values ≥ 17 μM across all isoforms tested (1A2, 2D6, 2C9, and 3A4). Highlighted in Table 6 are the in vivo rat PK parameters. VU6016235 displayed high oral bioavailability (≥100% at a 3 mg/kg dose and 84% at a 30 mg/kg dose) and low plasma clearance (4.9 mL/min/kg) in rat. Volume of distribution was moderate (1.3 L/kg), and elimination t1/2 was 3.4 h. In a rat dose escalation pharmacokinetic (PK) study, VU6016235 demonstrated an increase in the mean AUC0-∞ (3 to 30 mg/kg, po). In a preclinical pharmacodynamic (PD) model of antipsychotic-like activity, VU6016235 demonstrated a robust dose-dependent reversal of amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion (AHL) significant at doses of 1.0, 3.0, and 10.0 mg/kg after oral administration (MED = 1 mg/kg, Figure 3). At 90 min postdose, brain/plasma Kp and Kp,uu were determined at 1 mg/kg (Kp = 0.62; Kp,uu = 0.41), 3 mg/kg (Kp = 0.79; Kp,uu = 0.53), and 10 mg/kg (Kp = 0.82; Kp,uu = 0.55) with mean Cbrain,u values of 13.9, 60.3, and 204 nM, respectively (Table 7).

Table 5. Further In Vitro Characterization of VU6016235 (22g).

| muscarinic selectivity45 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) | [%Ach Max] | pEC50 | |

| rat M4a | 42 | [89] | 7.38 |

| human M1a | inactive | ||

| human M2a | 6200 | [46] | 5.21 |

| human M3a | inactive | ||

| human M5a | inactive | ||

| permeability assay | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cell line | Papp (A–B) (cm/s) | Papp (B–A) (cm/s) | efflux ratio |

| MDCK-MDR1 | 47 × 10–6 | 68 × 10–6 | 1.5 |

| P450 inhibition IC50 (μM)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A2 | 2D6 | 2C9 | 3A4 |

| 23 | >30 | 17 | 17 |

Calcium mobilization assay; EC50 values for rM4 and hM2 represent three experiments performed in triplicate; EC50 values for hM1,3,5 represent one to two experiments performed in triplicate.

Assayed in pooled human liver microsomes (HLM) in the presence of NADPH with CYP-specific probe substrates.

Table 6. In Vivo Rat and Dog iv/po PK Profile of VU6016235.

| iv PK | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | dose (mg/kg) | t1/2 (hr)b | MRT (hr)b | CLp (mL/min/kg)b | Vss (L/kg)b |

| rat (SD)a | 1.0 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| dog (beagle)c | 0.5 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 23.8 | 2.3 |

| po PK | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | dose (mg/kg) | Tmax (hr) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0-∞ (hr·ng/mL) | %F |

| rat (SD)d | 3.0 | 3.0 | 657 | 8408 | >100 |

| rat (SD)d | 30.0 | 5.0 | 4455 | 59164 | 84 |

| dog (beagle)e | 1.0 | 0.83 | 62.4 | 200 | 27.5 |

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (n = 2); vehicle = 10% EtOH, 40% PEG 400, 50% Saline (1.0 mL/kg).

t1/2 = terminal phase plasma half-life; MRT = mean residence time; Clp = plasma clearance; Vss = volume of distribution at steady state.

Male beagle dogs (n = 3); vehicle = 10% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD).

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 2); vehicle = 10% Tween-80 in water (10 mL/kg; suspension).

Male beagle dogs (n = 3); fasted; vehicle = 0.5% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) in water.

Figure 3.

VU6016235, administered orally, reverses amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion in male Sprague–Dawley rats. (Left) Time course of locomotor activity. (Right) Total locomotor activity during the 60 min period following amphetamine administration. Data are means ± SEM of 6–8 animals per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001 vs Vehicle + Amphetamine. VU0467154 = positive control. Vehicle = 10% Tween80 in H2O.

Table 7. Relationship between Total (Mean Cbrain) and Unbound (Mean Cbrain,u) Brain Concentrations of VU6016235 and Pharmacodynamic Effects on Amphetamine (0.75 mg/kg, sc)-Induced Hyperlocomation in Rats.a.

| dose (mg/kg) | mean reversal of AHL (%) | mean Cplasmab (μM) | mean Cplasma,uc (nM) | mean Cbrainb (μM) | mean Cbrain,ud (nM) | brain/plasma mean Kp | brain/plasma mean Kp,uu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30.5 | 1.37 | 33.2 | 0.85 | 13.9 | 0.62 | 0.41 |

| 3 | 41.4 | 4.66 | 113 | 3.70 | 60.3 | 0.79 | 0.53 |

| 10 | 54.2 | 15.3 | 372 | 12.5 | 204 | 0.82 | 0.55 |

Bioanalysis only performed for efficacious doses.

At 1.5 h proadministration.

Estimated unbound plasma concentration based on the rat fu,p (0.024).

Estimated unbound brain concentration based on the rat fu,b (0.016).

On the basis of the encouraging in vivo rat PK and PD profile of VU6016235, the off-target and safety/toxicity profiles for this compound were further investigated. An ancillary pharmacology screen (Eurofins Panlabs) revealed no off-target activity (≤26% inhibition at 10 μM across all off-targets screened) (see the Supporting Information for the full ancillary pharmacology profile).47 Additionally, VU6016235 was negative in a Mini Ames test (4 strains ± S9). Potential cardiac risks were also assessed (Charles River ChanTest Cardiac Channel Panel), and VU6016235 was not found to strongly inhibit any cardiac ion channels tested (all ion channel inhibitions ≤14% at 10 μM (patch clamp, see the Supporting Information for additional details).48 With such promising data, VU6016235 was progressed into higher species in vivo PK (Table 6). VU6016235 displayed moderate oral bioavailability (27.5% at a 1 mg/kg dose) in the dog; however, high plasma clearance (∼24 mL/min/kg, nearly 78% hepatic blood flow) in the dog halted further progress of VU6016235.

Conclusion

In summary, a scaffold hopping exercise utilizing a “tie-back” strategy to design M4 PAMs 1 and 2 proved to be a successful strategy in converting an early micromolar M4 PAM, 4, into potent tricyclic M4 PAM analogues devoid of the classic β-amino carboxamide moiety. Two analogues within the tricycle series containing the 7,9-dimethylthieno[2,3-d:4,5-d’]dipyrimidine core core (5) were potent M4 PAMs (14h and 14i; hM4 EC50 < 200 nM). Both analogues displayed favorable fraction unbound in regard to human plasma protein and rat brain homogenate binding (BHB) (1% < fu < 5%) and low rat plasma protein binding (PPB) (fu > 5%). Additionally, both analogues were highly CNS-penetrant (rat brain/plasma Kp > 5, Kp,uu > 1). Points of difference were observed in the predicted hepatic clearance. While 14i displayed high human (CLhep = 19 mL/min/kg) and rat (CLhep = 66 mL/min/kg) predicted hepatic clearance, 14h displayed moderate human (CLhep = 14 mL/min/kg) and rat (CLhep = 44 mL/min/kg) predicted hepatic clearance.

Moreover, several analogues (22e-g and 22j,k) containing the 2,4-dimethylpyrido[4′,3′:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine core (6) were potent M4 PAMs (hM4 EC50 < 200 nM). Four of the five analogues profiled (22e, 22f, 22j, and 22k) displayed high human (CLhep ≥ 15 mL/min/kg) and rat (CLhep ≥ 50 mL/min/kg) predicted hepatic clearance. Conversely, 22g displayed moderate human (CLhep = 12 mL/min/kg) and rat (CLhep = 37 mL/min/kg) predicted hepatic clearance. While analogues 22e, 22i, and 22k were all highly bound to rat brain homogenates (fu < 1%), analogues 22f and 22g had modest fraction unbound (1% < fu < 5%). Most analogues in this series had moderate rat and human plasma protein binding except for 22e, which was highly bound to human plasma proteins. Furthermore, all five analogues evaluated were highly CNS-penetrant (rat brain/plasma Kp > 5, Kp,uu > 1).

Our efforts to mask the β-amino carboxamide moiety of an early M4 PAM compound 4 resulted in the discovery of two new tricyclic cores (5 and 6), which provided potent M4 PAM analogues that were highly brain-penetrant. This endeavor also provided analogues 14h (VU6015976) and 22g (VU6016235), which display 24-fold and 30-fold increase in human M4 activity, respectively, when compared to parent compound 4 (hM4 EC50 = 4.5 μM). Moreover, tricycles VU6015976 and VU6016235 exhibited moderate predicted hepatic clearance profiles in rat and human similar to parent compound 4; this was a great improvement over previously reported tricycle VU6007215 (Figure 2).25 Additionally, both VU6015976 and VU6016235 displayed a higher CNS distribution of unbound drug (Kp,uu = 0.76 and 1.27, respectively) compared to VU6007215 (Kp,uu = 0.40). Overall, VU6015976 and VU6016235 have similarly attractive DMPK profiles; however, because of VU6016235 exhibiting a nearly 9-fold increase in rat M4 activity compared to VU6015976, we selected VU6016235 to carry forward for further in vivo PK/PD profiling. Although VU6016235 possessed a favorable rat PK profile, displayed efficacy in a rat AHL-induced hyperlocomotion PD assay, and was determined to have minimal safety and toxicity risks, its inferior dog in vivo PK necessitated evaluation in alternative nonrodent species. Efforts aimed at ameliorating higher species PK are ongoing and will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for funding via the NIH Roadmap Initiative 1×01MH077607 (C.M.N.), the Molecular Libraries Probe Center Network (U54MH084659 to C.W.L.), and U01MH087965 (Vanderbilt NCDDG). We also thank William K. Warren, Jr. and the William K. Warren Foundation who funded the William K. Warren, Jr. Chain in Medicine (to C.W.L.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AHL

amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion

- BHB

brain homogenate binding

- CLhep

hepatic clearance

- CLint

intrinsic clearance

- CNS

central nervous system

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DMPK

drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- hM4

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 4, human

- mAChR

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor

- MED

minimum effective dose

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PBL

plasma-to-brain level

- PPB

plasma protein binding

- rM4

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 4, rat

- SAR

structure activity relationship

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.4c00465.

Detailed methods for the synthesis and characterization of key compounds, experimental details for all assays performed [in vitro pharmacology; DMPK (in vitro and in vivo); rat AHL], and additional ancillary pharmacology data (Eurofins Panlabs and Cardiac Ion Channel Panel) (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.L.E., L.A.B., and K.J.T. performed synthetic chemistry and scaled up key compounds. V.B.L., A.L.R., H.P.C., and C.M.N. performed and analyzed molecular pharmacology. M.B. and C.K.J. performed and analyzed behavioral pharmacology experiments. W.P., J.M.R., A.T.G., and C.K.J. performed in vivo pharmacokinetic experiments. S.C., T.M.B., and O.B. performed and analyzed DMPK experiments. J.L.E., K.J.T., P.J.C, C.W.L., D.W.E, C.M.N., and C.K.J. oversaw experimental design, and K.J.T. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): J.L.E., L.A.B., C.W.L., P.J.C., D.W.E., and K.J.T. are inventors on applications for composition of matter patents that protect several series of M4 positive allosteric modulators.

Supplementary Material

References

- Jones C. K.; Byun N.; Bubser M. Muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists and allosteric modulators for the treatment of Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012, 37, 16–42. 10.1038/npp.2011.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebois E. P.; Thorn C.; Edgerton J. R.; Popiolek M.; Xi S. Muscarinic receptor subtype distribution in the central nervous system and relavenance to aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2018, 136, 362–373. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W.; Plotkin J. L.; Francardo V.; Ko W. K. D.; Xie Z.; Li Q.; Fieblinger T.; Wess J.; Neubig R. R.; Lindsley C. W.; Conn P. J.; Greengard P.; Bezard E.; Cenci M. A.; Surmeier D. J. M4 Muscarinic receptor signaling ameliorates striatal plasticity deficits in models of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Neuron. 2015, 88, 762–773. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancani T.; Foster D. J.; Moehle M. S.; Bichell T. J.; Bradley E.; Bridges T. M.; Klar R.; Poslusney M.; Rook J. M.; Daniels J. S.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Wood M. R.; Bowman A. B.; Lindsley C. W.; Xiang Z.; Conn P. J. Allosteric activation of M4 muscarinic receptors improve behavioral and physiological alteration in early symptomatic YAC128 mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, 14078–14083. 10.1073/pnas.1512812112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges T. M.; LeBois E. P.; Hopkins C. R.; Wood M. R.; Jones C. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. The antipsychotic potential of muscarinic allosteric modulation. Drug News Perspect. 2010, 23, 229–240. 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.4.1416977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster D. J.; Wilson J. M.; Remke D. H.; Mahmood M. S.; Uddin M. J.; Wess J.; Patel S.; Marnett L. J.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Xiang Z.; Lindsley C. W.; Rook J. M.; Conn P. J. Antipsychotic-like effects of M4 positive allosteric modulators are mediated by CB2 receptor-dependent inhibition of Dopamine release. Neuron. 2016, 91, 1244–1252. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M.; Roth B. L. Allosteric Antipsychotics: M4 Muscarinic potentiators as novel treatments for Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010, 35, 851–852. 10.1038/npp.2009.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A. C.; Kobilka B. K.; Gautam D.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A.; Wess J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: novel opportunities for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2014, 13, 549–560. 10.1038/nrd4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodick N. C.; Offen W. W.; Levey A. I.; Cutler N. R.; Gauthier S. G.; Satlin A.; Shannon H. E.; Tollefson G. D.; Rasmussen K.; Bymaster F. P.; Hurley D. J.; Potter W. Z.; Paul S. M. Effects of xanomeline, a selective muscarinic receptor agonist, on cognitive function and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 1997, 54, 465–473. 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160091022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar A.; Potter W. Z.; Lightfoot J.; Lienemann J.; Dubé S.; Mallinckrodt C.; Bymaster F. P.; McKinzie D. L.; Felder C. C. Selective muscarinic receptor agonist xanomeline as a novel treatment approach for schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008, 165, 1033–1039. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.06091591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol Myers Squibb Completes Acquisition of Karuna Therapeutics, Strengthening Neuroscience Portfolio. https://news.bms.com/news/details/2024/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Completes-Acquisition-of-Karuna-Therapeutics-Strengthening-Neuroscience-Portfolio/default.aspx (accessed 2024-05-08).

- Brannan S. K.; Sawchak S.; Miller A. C.; Lieberman J. A.; Paul S. M.; Breier A. Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist for Schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 717–726. 10.1056/NEJMoa2017015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert J. W.; Harrison S. T.; Mulhearn J.; Gomez R.; Tynebor R.; Jones K.; Bunda J.; Hanney B.; Wai J. M.; Cox C.; McCauley J. A.; Sanders J. M.; Magliaro B.; O’Brien J.; Pajkovic N.; Huszar Agrapides S. L.; Taylor A.; Gotter A.; Smith S. M.; Uslaner r J.; Browne S.; Risso S.; Egbertson M. Discovery, Optimization, and Biological Characterization of 2,3,6-Trisubstituted Pyridine-Containing M4 Positive Allosteric Modulators. ChemMedChem. 2019, 14, 943–951. 10.1002/cmdc.201900088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Multiple Ascending Dose Trial of CVL-231 in Subjects with Schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04136873 (accessed 2023-10-18).

- PET Trial to Evaluate Target Occupancy of CVL-231 on Brain Receptors Following Oral Dosing. Date of Access. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04787302?term=CVL-231(accessed 2023-10-18).

- Trial to Study the Effect of CVL-231 on 24-h Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Participants with Schizophrenia. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05245539 (accessed 2023-10-18).

- Pharmacokinetics of CVL-231 Following Single Oral Administration of Modified- and Immediate-release Formulation in Fasted and Fed Healthy Participants. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05106309 (accessed 2023-10-18).

- A Study to Evaluate Safety and Tolerability of CVL-231 (Emraclidine) in Adult Participants with Schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05443724 (accessed 2023-10-18).

- A Trial of 10 and 30 mg Doses of CVL-231 (Emraclidine) in Participants with Schizophrenia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05227690 (accessed 2023-10-18).

- Butler C. R.; Popiolek M.; McAllister L. A.; LaChapelle E. A.; Kramer M.; Beck E. M.; Mente S.; Brodney M. A.; Brown M.; Gilbert A.; Helal C.; Ogilvie K.; Starr J.; Uccello D.; Grimwood S.; Edgerton J.; Garst-Orozco J.; Kozak R.; Lotarski S.; Rossi A.; Smith D.; O’Connor R.; Lazzaro J.; Steppan C.; Steyn S. J. Design and Synthesis of Clinical Candidate PF-06852231 (CVL-231): A Brain Penetrant, Selective, Positive Allosteric Modulator of the M4Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 10831–10847. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M. F.; Engers J. L.; Chang S.; Zhan X.; Weiner R. L.; Luscombe V. B.; Rodriguez A. L.; Cho H. P.; Niswender C. M.; Bridges T. M.; Conn P. J.; Engers D. W.; Lindsley C. W. Discovery of a novel 2,4-dimethylquinolin-6-carboxamide M4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) chemotype via scaffold hopping. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 4999–5001. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple K. J.; Engers J. L.; Long M. F.; Gregro A. R.; Watson K. J.; Chang S.; Jenkins M. T.; Luscombe V. B.; Rodriguez A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Bridges T. M.; Conn P. J.; Engers D. W.; Lindsley C. W. Discovery of a novel 3,4-dimethylcinnoline carboxamide M4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) chemotype via scaffold hopping. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 126678. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple K. J.; Engers J. L.; Long M. F.; Watson K. J.; Chang S.; Luscombe V. B.; Jenkins M. T.; Rodriguez A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Bridges T. M.; Conn P. J.; Engers D. W.; Lindsley C. W. Discovery of a novel 2,3-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine-6-carboxamide M4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) chemotype. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126812. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple K. J.; Long M. F.; Engers J. L.; Watson K. J.; Chang S.; Luscombe V. B.; Rodriguez A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Bridges T. M.; Conn P. J.; Engers D. W.; Lindsley C. W. Discovery of structurally distinct tricyclic M4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) chemotypes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126811. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M. F.; Capstick R. A.; Spearing P. K.; Engers J. L.; Gregro A. R.; Bollinger S. R.; Chang S.; Luscombe V. B.; Rodriguez A. L.; Cho H. P.; Niswender C. M.; Bridges T. M.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Engers D. W.; Temple K. J. Discovery of structurally distinct tricyclic M4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) chemotypes-Part 2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 53, 128416. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovich J. M.; Vinson P. N.; Sheffler D. J.; Lamsal A.; Utley T. J.; Blobaum A. L.; Bridges T. M.; Le U.; Jones C. K.; Wood M. R.; Daniels J. S.; Conn P. J.; Niswender C. M.; Lindsley C. W.; Hopkins C. R. Discovery of N-(4-methoxy-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazol—2-yl)isonicotinamide, ML293, as a novel, selective and brain penetrant positive allosteric modulator of the muscarinic 4 (M4) receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 5084–5088. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E.; Chase P.; Niswender C. M.; Utley T. J.; Sheffler D. J.; Noetzel M. J.; Lamsal A.; Wood M. R.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Madoux F.; Acosta M.; Scampavia L.; Spicer T.; Hodder P. Application of Parallel Multiparametric Cell-Based FLIPR Detection Assays for the Identification of Modulators of the Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor 4 (M4). J. Biomol. Screening. 2015, 20, 858–868. 10.1177/1087057115581770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W. Y.; McKinzie D. L.; Bose S.; Mitchell S. N.; Witkin J. M.; Thompson R. C.; Christopoulos A.; Lazareno S.; Birdsall N. J.; Bymaster F. P.; Felder C. C. Allosteric modulation of the muscarinic M4 receptor as an approach to treating Schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 10978–10983. 10.1073/pnas.0800567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach K.; Loiacono R. E.; Felder C. C.; McKinzie D. L.; Mogg A.; Shaw D. B.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A. Molecular Mechanisms of action and in vivo validation of an M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric modulator with potential antipsychotic properties. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010, 35, 855–869. 10.1038/npp.2009.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady A.; Jones C. K.; Bridges T. M.; Kennedy J. P.; Thompson A. D.; Heiman J. U.; Breininger M. L.; Gentry P. R.; Yin H.; Jadhav S. B.; Shirey J. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Centrally active allosteric potentiators of the M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor reverse amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotor activity in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 327, 941–953. 10.1124/jpet.108.140350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun N. E.; Grannan M.; Bubser M.; Barry R. L.; Thompson A.; Rosanelli J.; Gowrishankar R.; Kelm N. D.; Damon S.; Bridges T. M.; Melancon B. J.; Tarr J. C.; Brogan J. T.; Avison M. J.; Deutch A. Y.; Wess J.; Wood M. R.; Lindsley C. W.; Gore J. C.; Conn P. J.; Jones C. K. Antipsychotic drug-like effects of the selective M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor positive allosteric modulator VU0152100. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014, 39, 1578–1593. 10.1038/npp.2014.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubser M.; Bridges T. M.; Dencker D.; Gould R. W.; Grannan M.; Noetzel M. J.; Lamsal A.; Niswender C. M.; Daniels J. S.; Poslusney M. S.; Melancon B. J.; Tarr J. C.; Byers F. W.; Wess J.; Duggan M. E.; Dunlop J.; Wood M. W.; Brandon N. J.; Wood M. R.; Lindsley C. W.; Conn P. J.; Jones C. K. Selective activation of M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors reverses MK-801-induced behavioral impairments and enhances associative learning in rodents. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 920–942. 10.1021/cn500128b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melancon B. J.; Wood M. R.; Noetzel M. J.; Nance K. D.; Engelberg E. M.; Han C.; Lamsal A.; Chang S.; Cho H. P.; Byers F. W.; Bubser M.; Jones C. K.; Niswender C. M.; Wood M. W.; Engers D. W.; Wu D.; Brandon N. J.; Duggan M. E.; Conn P. J.; Bridges T. M.; Lindsley C. W. Optimization of M4 positive allosteric modulators (PAMs): The discovery of VU0476406, a non-human primate in vivo tool compound for translational pharmacology. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 2296–2301. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M. R.; Noetzel J.; Melancon B. H.; Poslusney M. S.; Nance K. D.; Hurtado M. A.; Luscombe V. B.; Weiner R. L.; Rodriguez A. L.; Lamsal A.; Chang S.; Bubser M.; Blobaum A. L.; Engers D. W.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Brandon N. J.; Wood M. W.; Duggan M. E.; Conn P. J.; Bridges T. M.; Lindsley C. W. Discovery of VU0467485/AZ13713945: An M4 PAM evaluated as a preclinical candidate for the treatment of Schizophrenia. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 233–238. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr J. C.; Wood M. R.; Noetzel M. J.; Bertron J. L.; Weiner R. L.; Rodriguez A. L.; Lamsal A.; Byers F. W.; Chang S.; Cho H. P.; Jones C. K.; Niswender C. M.; Wood M. W.; Brandon N. J.; Duggan M. E.; Conn P. J.; Bridges T. M.; Lindsley C. W. Challenges in the development of an M4 PAM preclinical candidate: The discovery, SAR, and in vivo characterization of a series of 3-aminoazetidine-derived amides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 2990–2995. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le U.; Melancon B. J.; Bridges T. M.; Vinson P. N.; Utley T. J.; Lamsal A.; Rodriguez A. L.; Venable D.; Sheffler D. J.; Jones C. K.; Blobaum A. L.; Wood M. R.; Daniels J. S.; Conn P. J.; Niswender C. M.; Lindsley C. W.; Hopkins C. R. Discovery of a selective M4 positive allosteric modulator based on 3-amino-thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamide scaffold: Development of ML253, a potent and brain penetrant compound that is active in a preclinical model of schizophrenia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 346–350. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J. P.; Bridges T. M.; Gentry P. R.; Brogan J. T.; Kane A. S.; Jones C. K.; Brady A. E.; Shirey J. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Synthesis of Structure-Activity Relationships of Allosteric Potentiators of the M4 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor. ChemMedChem. 2009, 4, 1600–1607. 10.1002/cmdc.200900231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo M.; Huynh T.; Valant C.; Lane J. R.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A.; Capuano B. A structure-activity relationship study of the positive allosteric modulator LY233298 at the M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. MedChemComm. 2015, 6, 1998–2003. 10.1039/C5MD00334B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daghish M.; Schulze A.; Reichelt C.; Ludwig A.; Leistner S.; Heinicke J.; Krödel A.. Substituted carboxamides method for production and use thereof as TNF-alpha release inhibitors. WO2006100095A1, 2006.

- Tarr J. C.; Wood M. R.; Noetzel M. J.; Melancon B. J.; Lamsal A.; Luscombe V. B.; Rodriguez A. L.; Byers F. W.; Chang S.; Cho H. P.; Engers D. W.; Jones C. K.; Niswender C. M.; Wood M. W.; Brandon N. J.; Duggan M. E.; Conn P. J.; Bridges T. M.; Lindsley C. W. Challenges in the development of an M4 PAM preclinical candidate: The discovery, SAR, and biological characterization of a series of azetidine-derived tertiary amides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 5179–5184. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capstick R. A.; Bollinger S. R.; Engers J. L.; Long M. F.; Chang S.; Luscombe V. B.; Rodriguez A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Bridges T. M.; Boutaud O.; Conn P. J.; Engers D. W.; Lindsley C. W.; Temple K. J. Discovery of VU6008077: A Structurally Distinct Tricyclic M4 Positive Allosteric Modulator with Improved CYP450 Profile. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1358–1366. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürstner A.; Leitner A.; Méndez M.; Krause H. Iron-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13856–13863. 10.1021/ja027190t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankovic Z. CNS Drug Design: Balancing Physiochemical Properties for Optimal Brain Exposure. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2584–2608. 10.1021/jm501535r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager T. T.; Hou X.; Verhoest P. R.; Villalobos A. Central Nervous System Multiparameter Optimization Desirability: Application in Drug Discovery. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 767–775. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehle M. S.; Bender A. M.; Dickerson J. W.; Foster D. J.; Qi A.; Cho H. P.; Donsante Y.; Peng W.; Bryant Z.; Stillwell K. J.; Bridges T. M.; Chang S.; Watson K. J.; O’Neill J. C.; Engers J. L.; Peng L.; Rodriguez A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Lindsley C. W.; Hess E. J.; Conn P. J.; Rook J. M. Discovery of the First Selective M4 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonist with in Vivo Antiparkinsonian and Antidystonic Efficacy. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021, 4, 1306–1321. 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M. R.; Noetzel M. J.; Poslusney M. S.; Melancon B. J.; Tarr J. C.; Lamsal A.; Chang S.; Luscombe V. B.; Weiner R. L.; Cho H. P.; Bubser M.; Jones C. K.; Niswender C. M.; Wood M. W.; Engers D. W.; Brandon N. J.; Duggan M. E.; Conn P. J.; Bridges T. M.; Lindsley C. W. Challenges in the development of an M4 PAM in vivo tool compound: The discovery of VU0467154 and unexpected DMPK profiles of close analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 171–175. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.11.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurofins LeadProfiling Screen SafetyScreen Panel. https://www.eurofinsdiscovery.com/catalog/leadprofilingscreen-safetyscreen-panel-tw/PP68 (accessed 2024-06-24).

- Charles River ChanTest Cardiac Channel Panel and SaVetyTM Assessment. https://www.criver.com/products-services/safety-assessment/safety-pharmacology/vitro-assays/chantest-cardiac-channel-panel-savetytm-assessment?region=3601 (accessed 2024-06-24).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.