Getting intimate with us

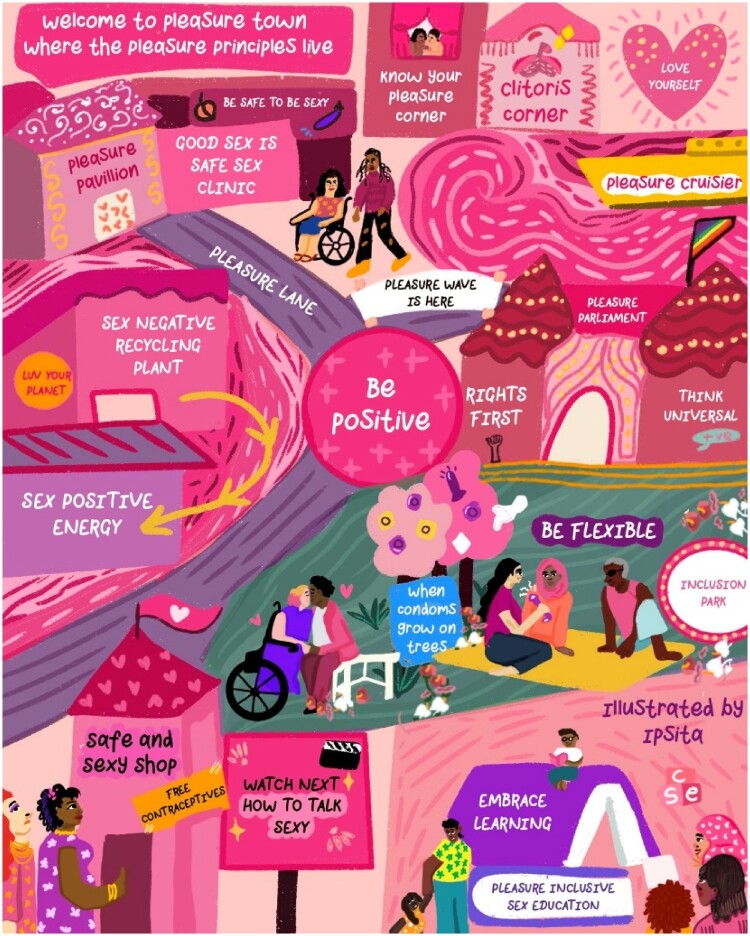

We are thrilled to be asked to curate this collection of content on a topic that excites us both hugely: pleasure. Together, we bring over 30 years of advocacy on the importance of pleasure, open discussions of sexuality and the importance of joy in sexual health. We have lived and worked in different geographies and brought different skillsets in selecting the content for this collection and writing this editorial. Through our pleasure-focused organisations, we have enjoyed working together to challenge the stigma around pleasure and to create fun and entertaining sex education. As guest editors, we draw on our own learnings and lived experiences over the years of working in this field as feminists and pleasure activists. Both our organisations produced visions of sex-positive pleasure-filled worlds, showing how like-minded and pleasure-passionate we are: the Agents of Ishq created The Political Power of Pleasure: AOI Manifesto and Figure 1 shows The Pleasure Project’s vision of a sex-positive world.

Figure 1.

Pleasure town – the Pleasure Project

We believe that pleasure reconnects our work with its fundamental purpose, so easily lost in technicalities and protocols – to make knowledge adventurous and revelatory, not merely disciplinary and disciplined. To make politics meaningful, not just correct. To dissolve hierarchies, not harden them. To make life itself pleasurable, not just bearable.

That’s why we, as guest editors, were so excited to be asked to look back at the history of pleasure in the articles published in Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters (SRHM) and in content hosted on the Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters (SRHM) organisational website over the past 20 years, seeking out the luscious corners where pleasure has been celebrated and suggesting opportunities for filling research gaps and knowledge creation opportunities within and beyond this space.

Pillow talk

We cannot be truly liberatory in our aspirations for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), or be meaningful in our engagement in body politics, unless we engage deeply with the experiences and politics of pleasure. Sadly, for too long, sexual and reproductive health knowledge creation, policy and programmatic action have been overwhelmingly focused on death, danger, disease and reproducing. When we, as torchbearers for SRHR, don’t recognise or speak of pleasure, we re-inscribe the shame and stigma that surround sex and lead to so many disempowered and unsafe choices in sexual life.

We loved reading all the past pleasure content of SRHM and SRHM – celebrating the wide range of pleasures, from the golden triangle of sexual health, sexual rights and pleasure,1 to the beauties of lube,2 female masturbation,3 pride,4 pleasure-meters5 and sex tech6 – and we are delighted that the journal and organisation use a combination of peer-reviewed articles, poetry, podcasts and blogs involving first-person accounts and stories to express the beautiful diversities of pleasure.

These few lines in the poem “Well-being” by Alice d’Aboville7 in the SRHM collection Poetry for Sexual and Reproductive Justice highlight the humanness of seeking pleasure and how poetry can capture the beauty of what we aim to articulate here:

I am blessed and sacred

To be capable of creating miracles

That outlive me

But I am also a soul

Who seeks discovery, pleasure, and glee

Flirting with pleasure: how it started

But let’s start with a couple of authors pointing to the sounds of silence around pleasure and the damage that does. Guan8 states that “Sexual education without the discussion of pleasure maintains a void that adolescents are left to blindly explore on their own”, while Purdy9 goes a step further to provide a textual analysis of the highly influential Guttmacher-Lancet commission on SRHR – which refreshingly did mention pleasure (four times) but was overwhelmingly focused on the negative consequences of sex – and asks:

“Why do we talk about the distortions and dangers of sex (HIV, 73 times; risk, 57 times; cancer, 35 times) without first defining sex as a natural, pleasurable, wonderful thing? Our language gives in to our collective fear and concern that sex is somehow a bad or dangerous thing”.

And we were pleasantly surprised to see a small but perfectly formed range of content that did look at the idea of pleasure from different perspectives and how it is critical to delivery of SRHR. These included research on how a sexual health service delivery organisation enriched their Kenyan chatbot content to a pleasure-inclusive offering and saw a large increase in engagement.10 El Feki11 and Bo3 go beyond this to wonder why there is such a silencing of pleasure in SRHR, and their wonderful article and blog celebrating eroticism in the Arab region and self-pleasures, respectively, point out the colonial and historical influences that have caused this taboo and stigmatisation. Muhanguzi12 points out how low-income women talk about and create pleasure in Uganda, thus flipping the stereotype that poorer women cannot or do not prioritise pleasure, and Edmunds and Gupta13 challenge the narratives of risk and violence and the hidden spaces of pleasure in Delhi, India.

This content did not focus on sexual life only as risky business, with threats of disease, shame and impossibility constantly looming, as has been traditional in the development and health sector, but instead acknowledged that pleasure is both a motivation and a desirable outcome for many people. In doing so, the authors move the narrative from prevention – of disease, violence or unwanted pregnancy – to articulation of choice and desire that communities could move towards. Purdy9 points out the inconvenient but obvious truth that:

“If the main reason people have sex is for pleasure, we can use that to remind them that contraception enables them to enhance this intimacy without the consequences of pregnancy. Ensuring products and services are easily available and affordable, and delivered in a non-stigmatized, de-medicalized manner, will further support the notion that contraception promotes pleasure, and is not merely a medical intervention.”

However, things are changing, as pleasure as linked to sexual rights has become more visible,14–16 and now we know that pleasure-inclusive sexual health programmes and sexuality education increase positive sexual health outcomes.17 To date. more than 50 key organisations and initiatives have committed to integrating pleasure in order to ensure positive outcomes for public health initiatives.18

Pleasing/playing with ourselves: pleasure politics and where it could take us

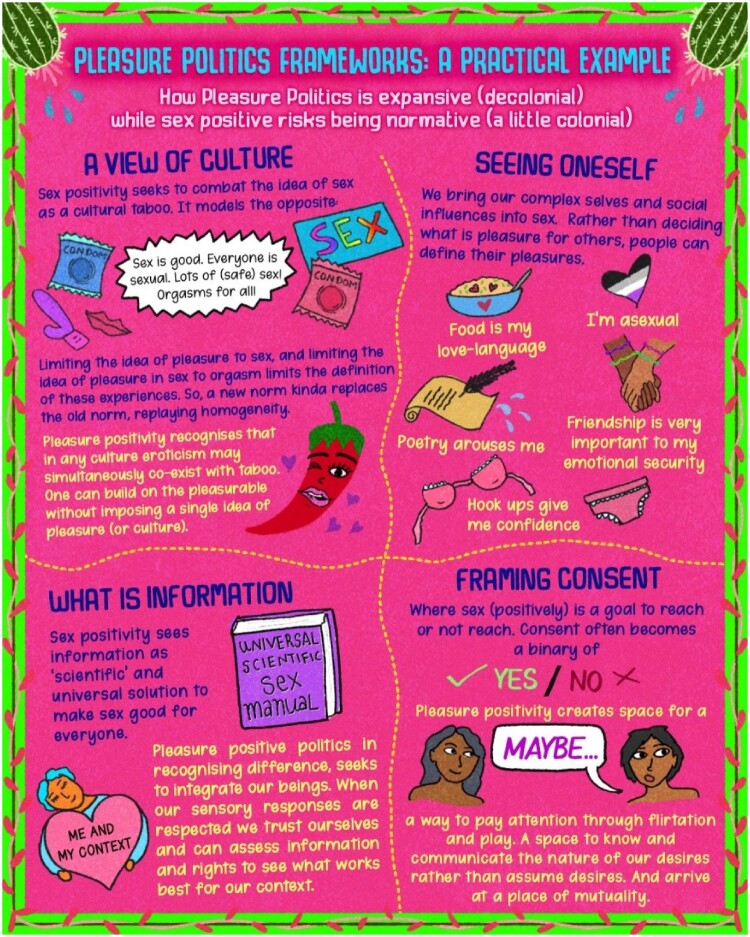

This acknowledgement of pleasure is important, but we hope for and argue towards a more radical understanding of pleasure, as a political lens and as a methodological approach to reframe how the development sector imagines intervention and impact. Pleasure gets namechecked as “a good thing” in a way that fits safely into a sex-positive framework, but is rarely explored in all its contradictions and individuality, as explained in Figure 2. Hence it risks being mired in outcomes, funding politics, indicators and scalability – being instrumentalised until its vulnerability is lost, together with our opportunities to be honest, to have fun and to tell our stories. But hopefully, this collection and increased awareness can help to create safe spaces to explore our desires, facilitating a much more expansive approach of pleasure politics.

Figure 2.

Pleasure-Positive versus Sex-Positive Frameworks from the agents of Ishq Pleasure Manifesto

There is a political power in pleasure, in visioning what a sex-positive future could look like, as the Agents of Ishq Pleasure Manifesto highlights and The Pleasure Project’s “Erotic Justice [Wo]Manifesto” shows.19

We cannot simply add pleasure to an otherwise unquestioned frame, one where pleasure is only a route to safer sex, as the sanitary bare minimum. Where pleasure, too, becomes an instrumentalised intervention within a biomedical risk-focused and “techno-fix” world. Rather, we can draw upon the understandings outside this normative frame to co-create a new politics of sexuality and sexual health which are informed and transformed via the experiences of marginalised communities as they seek the pleasure often forbidden to them. We can be more vulnerable and yet bold, remembering that the personal is political, and share our stories of touch, desire, the best sex we have ever had, the possibilities of pleasure activism and why we are and should be pleasure seekers in a puritanical world.

Pleasure as a portal to diverse erotic natures

Pleasure is experientially diverse: it means different things to different people, communities and cultures. To engage with pleasure is to engage deeply with this diversity. This is why the articles on disability and sexuality we read in SRHM/SRHM were electrifying and revelatory. We loved the whole issue on “Disability and sexuality: claiming sexual and reproductive rights”, which gave us a chink of light into how pleasure and desire could be written about and what we would love to see more in the literature and, frankly, the world.

Building on personal experience, these accounts provide a fresh understanding of autonomy empowerment, sexual-ness and rights. They provide the powerful frame of eroticism, our erotic natures, and in so doing, widen the understanding of sexuality to think about touch, with all its meanings of pleasure, empathy, mischief, excitement, gentleness and human connection: a notion of rights and a solution to touch and sexual deprivation imposed by a protectionist approach.

Disabled persons’ sexuality is ignored by society and social programmes, as this issue makes clear. Like many groups, they are subject to a patriarchal or protectionist approach to their well-being, where they are seldom the decision makers. At the same time, unhampered by so-called expertise, and pre-approved definitions of good sex, not only are members of the community devising their own strategies and producing narratives of autonomy, but they also impart an understanding which is far less programmatic and that is relevant to all people, not only people with disabilities. The SRHM blog post “Sex Tech for Sexual Health, Rights and Justice: Findings for the first public interest sex tech hackathon” shows us how those with an interest and lived experience, in this case designers, technologists and communities, can illuminate a positive vision of sex, sexuality, desire and liberatory possibilities.6 We also hear from very diverse communities such as midwives, sex workers and trans activists how pleasure has been a portal to better conversations and more joy, and a mechanism which allows for open conversations with groups across East and Southern Africa and in India.20

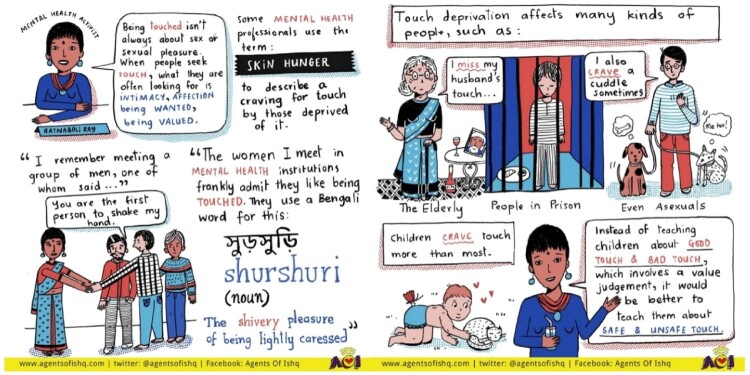

Touch as a gateway to a cosmos of intimacies

Touch should be central to sexual knowledge – touching the self, touching others, types of touch – moving away from the penetrative, heterosexual understanding of sex to a cosmos of intimacies where sensuality begets con-sensuality. These understandings of touch allow us to re-imagine human needs in terms of desire, as is also visible in Figure 3. We would love to see writing that brings the quality of lived experience of touch and of mental well-being within the fold of SRHR, and that supports an expansive view of what sexual health needs to be.

Figure 3.

Excerpt from a primer on Skin Hunger, Agents of Ishq

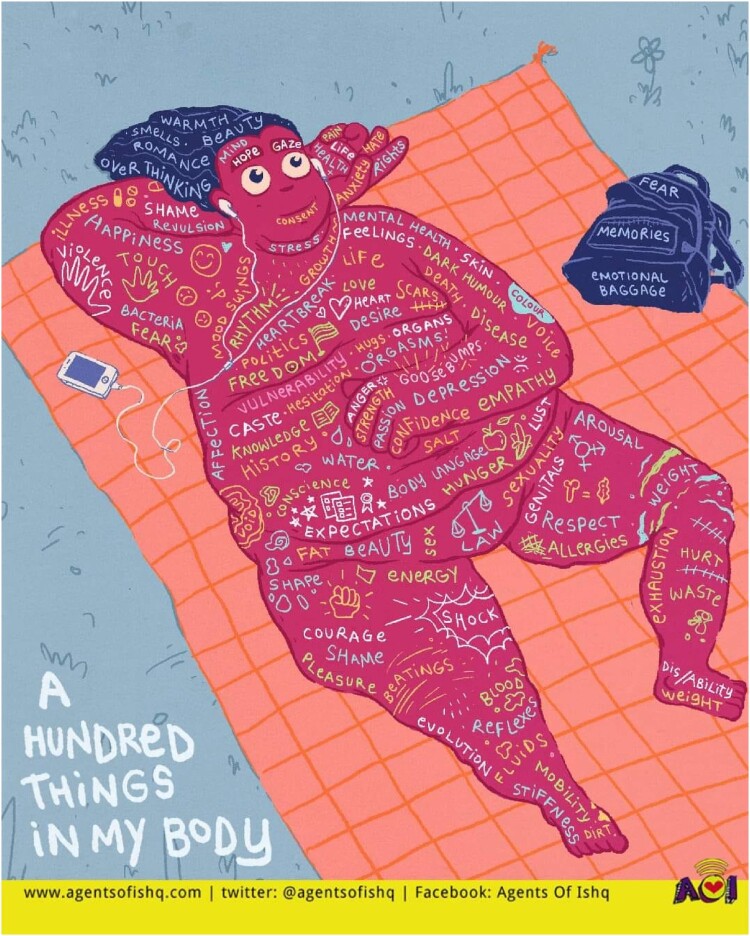

SRHM authors20–22 have argued for a much deeper form of intersectionality, recognising the body as not simply a biomedical site, but one shaped by law, history, emotion, desire, memory, social norms, ableism and biography, as in Figure 4. They also argue for an intersectionality of knowledge systems in which people are seen as experts on their own lives, and where advocates and researchers work in co-creative ways for social transformation that may constantly build on itself. As Alexander and Taylor Gomez21 say:

“For people with disability, including people with intellectual disability, pleasure may not be seen as important and in their daily lives, there is a distinct lack of discourse about pleasure leading to an experiential poverty”.

Figure 4.

A Hundred Things in My Body, Agents of Ishq

What is holding us back?

But why are we so fearful of this approach in the development and public health sector? Framed by scalability, outcomes, funding and indicators, we have become subservient to quantifiable ideas, and as pleasure becomes more acceptable, which it must, there is a risk it, too, will become “interventionalised”.

Sexual and reproductive health has long underscored the idea of heteronormativity – locating sex in peno-vaginal intercourse between a man and a woman, within coupledom and preferably for producing babies. When we look at what is often prioritised in research and interventions – “family planning” and “sexually transmitted infection prevention” – we see a trauma-based, agency-less notion of reproductive health focused more on reproductive tragedy than on sexual success. Who does this limited view of sex often leave out? Queer people, young unmarried people, single people of all ages, sex workers and their clients, the polyamorous, the asexual, older people, the kinky – those for whom sex is a part of intimacy, desire, sexual or emotional pleasure, an exploration of their own humanness and individuality. And, because of this silencing in mainstream conversations, in these communities’ sexuality there is a personal and political pleasure project with its own vital understandings. It holds, therefore, a new political imagination which could revitalise our scholarship and activism, and re-connect it to its feminist origins, where sexuality was a field of liberation and creativity, not management. We have seen and felt the silencing of pleasure in international development and public health as an active erasure of a critical component of sexuality: one that hurts those with marginalised sexualities most; one that makes sexuality education less effective and causes harm, shame and death; and one that holds existing historical and colonial power structures in place.

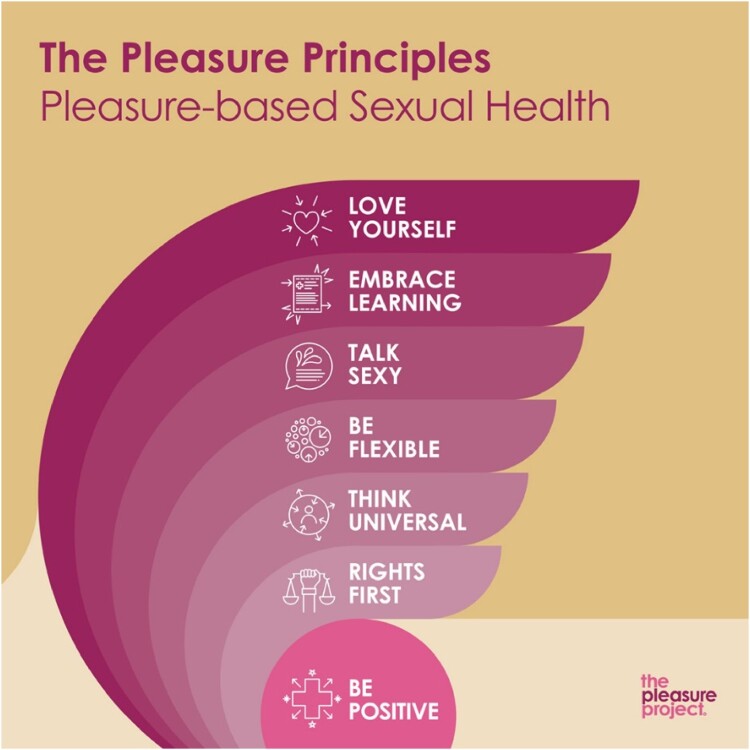

The hard truth is that these vectors also allow for more control. One must ask fearlessly and honestly if these do not tip over to serving funding proposals more than the communities we work with. Let us be led instead by our principles of pleasure and be inspired by pleasure evidence, best pleasure practices and lived experience of pleasure seekers, as in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The Pleasure Principles: an inspiration for pleasure-based sexual health, The Pleasure Project

The qualitative, subterranean world of pleasure poses many generative questions: can we let go this notion of control, into an exploratory understanding of sexual life and its overlaps with health and social reality? Can we let go a notion of power – who gets to tell whom the right way to be – so rooted in a civilisational-colonial mindset? Can we let go of designing control as risk management? As Alexander and Taylor Gomez say in their article,21 “Addressing sexuality only from a pathology or crisis stance would be akin to preparing for the holidays by only talking about all the negatives, e.g. financial hardship, family feuding, and individual stress. What fun would that be?”

At heart, pleasure politics is a decolonial politics. It recognises the decades of colonial history that have shaped the fields of medicine, reproductive health and sexuality. To recognise pleasure is to be willing to enter this space of self-reflection and self-questioning, and to emerge into a more vulnerable and, therefore, more revolutionary place. Please be confident and feel valid in your explorations of these themes. New writers are welcome. Let’s break the hierarchy about who is seen as an expert and celebrate the lived experiences of those who feel pleasure, who eroticise safer sex, who feel the impact of policy changes.

Finishing off, or I want to get to know you better

What might this place look like in terms of content? As curators and guest editors, what kind of creations and articles would we be thrilled and turned on to see in response to this unique pleasure collection? What articles would blow our minds, and would we read again and again, or even place by our bedside to read to our lovers? SRHM and SRHM have already begun some of this work by including diverse forms of knowledge – poetry and podcasts together with research articles and data analyses. By continuing to diversify the forms of knowledge creation – art, poetry, storytelling, personal accounts – a vibrant dialogue could be set up between the personal and the political. A central question of academic research could also be addressed: we love the array of qualitative data that add meaning to the quantitative, but also how do we move beyond this? How can we think about impact beyond the quantitative? Can we prompt ourselves to think about what reading a pleasure poem means for our sexual health?

Let us not speak generically about pleasure, but become more specific, more granular, more true-to-life. Enter the world of sex, dive into pleasure-seeking universes and individuals, and draw from the world of sex an understanding of politics, policy, community and rights, rather than fit sexuality into the currently available understandings of these domains. Flip the long-established expectations of what is credible, scientific and correct – and start an article with your lived experience, then take us on a journey to what this means in the world, then think how this experience might benefit more of us.

We would love to see research and articles on more provocative questions that do not simply adhere to existing political morality but, rather, use the world of pleasure to really tease complex concepts, to thicken the philosophical discourse. We imagine roundtable/symposium-style pieces and polemical reflections that broaden contexts.

Some questions we thought of when reading the existing pleasure-inclusive SRHM and SRHM content were:

♥ Who is the current discourse on consent really framed by or for – and is it more about protecting women than protecting their freedoms?

♥ Sexuality research has overlooked the positive experiences of women of colour, and focused on experiences of educated, industrialised, richer populations – we want to hear about the pleasure that women of colour experience outside of these populations and how the intersections of sexual identity, income and gender identity affect your sexual well-being

♥ We want to hear about sex purely for pleasure, sex between women, trans pleasures, sex outside the biomedical framing of SRHR interventions

♥ Why is the SRHR industry obsessed with bad sex, and how can we change this?

♥ What happens when you think about the best sex you ever had?

♥ How do class, caste and race determine the nature of your erotic life?

♥ Who defines community standards around sexuality or safe content?

♥ If porn is now considered sex education, how do we feel about it as feminists? Does that make us re-think porn or re-think sex education?

♥ What it is like to live in a sex-positive culture? What does “Pleasure Land” feel like?

♥ How can we reclaim cultural practices stigmatised by colonialism and use those to shape sexuality education and rights?

Saying bye for now

We look forward to getting to know you better, to understanding your multifaceted desires, your pleasures, what turns you on and makes you tick. When it feels good and why, telling us what is the most pleasurable sex you ever had and what it could feel like to live in a land where pleasure is possible and how that could lead to broader senses of pleasure, liberation and love.

Send in your love letters. Because Pleasure is Progress. Pleasure Matters.

Author contributions

Conception, interpretation: AP, PV. Conceptualisation, analysis, investigation, visualisation, writing of original draft, review and editing: AP, PV. Project administration and supervision: AP.

Funding Statement

None; however, Paromita Vohra received an honorarium for this work from The Pleasure Project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Provenance statement

This paper was commissioned and has gone through internal review.

References

- 1.Gruskin S, Yadav V, Castellanos-Usigli A, et al. Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27(1):29–40. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Li J, et al. Lubricants for the promotion of sexual health and well-being: a systematic review. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2022;29(3):2044198. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2022.2044198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bo J. Talking taboo: can female masturbation be good for reproductive health? [Internet] 2021. [cited 01/08/24]. Available from: https://www.srhm.org/news/talking-taboo-can-female-masturbation-be-good-for-reproductive-health/

- 4.Philpott A, Kamanda A. Pleasure and pride. [Internet] 2022. [cited 02/08/24]. Available from: https://www.srhm.org/news/pleasure-and-pride/

- 5.Castellanos-Usigli A, Braeken-van Schaik D.. The Pleasuremeter: exploring the links between sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure in sexual history-taking, SRHR counselling and education. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27(1):1–3. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1690334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stardust Z, Albury K, Kennedy J. Sex tech for sexual health, rights and justice: findings from the first public interest sex tech hackathon. [Internet] 2022. [cited 01/08/24]. Available from: https://www.srhm.org/news/sex-tech-for-sexual-health-rights-and-justice-findings-from-the-first-public-interest-sex-tech-hackathon/

- 7.d’Aboville A. Wellbeing. [Internet] 2022. [cited 01/08/24]. Available from: https://srhm2-cdn-1.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/30133321/Wellbeing.pdf

- 8.Guan L. Adolescents and sexual education during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. [Internet] 2021. [cited 01/08/24]. Available from: https://www.srhm.org/news/adolescents-and-sexual-education-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-and-beyond/

- 9.Purdy C. Pleasurable sex as a human right: an idea that has happily caught up to its constituents. [Internet] 2019. Available from: https://www.srhm.org/news/pleasurable-sex-as-a-human-right

- 10.Njogu J, Jaworski G, Oduor C, et al. Assessing acceptability and effectiveness of a pleasure-oriented sexual and reproductive health chatbot in Kenya: an exploratory mixed-methods study. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2023;31(4):2269008. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2023.2269008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Feki S. The Arab Bed Spring? Sexual rights in troubled times across the Middle East and North Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;23(46):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muhanguzi FK. “Sex is sweet”: women from low-income contexts in Uganda talk about sexual desire and pleasure. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;23(46):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edmunds E, Gupta A.. Headline violence and silenced pleasure: contested framings of consensual sex, power and rape in Delhi, India 2011-2014. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24(47):126–40. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starrs A, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher– Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642–2692. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pleasure Matters: shining a light on pleasure as a core element of SRHR. [Internet] 2022. [cited 01/08/24]. Available from: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/srhmjournal/episodes/Pleasure-Matters–shining-a-light-on-pleasure-as-a-core-element-of-SRHR-e1n8nv2

- 16.Philpott A, Mofokeng T, Yadav V. Sexual pleasure in times of COVID-19. [Internet] 2020. [cited 01/08/24]. Available from: https://www.srhm.org/news/sexual-pleasure-in-times-of-covid-19/

- 17.Zaneva M, Philpott A, Singh A, et al. What is the added value of incorporating pleasure in sexual health interventions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0261034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Pleasure Project . Organisations who endorse The Pleasure Principles. [Internet] 2024. [cited 27/07/24]. Available at: https://thepleasureproject.org/the-pleasure-principles/endorsing-organisations/

- 19.Philpott A, Singh A.. Good sex liberates: why sexual rights and erotic justice should get into bed with pleasure. In: Handbook of sexuality, gender, health and rights. Routledge; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills R, Northcott K, Kovacs E, et al. Opening a portal to pleasure based sexual and reproductive health around the globe; a qualitative analysis and best practice development study. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2023;31(3):2275838. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2023.2275838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander N, Taylor Gomez M.. Pleasure, sex, prohibition, intellectual disability, and dangerous ideas. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(50):114–120. doi: 10.1080/09688080.2017.1331690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Invalid S. Skin, tooth, and bone – the basis of movement is our people: a disability justice primer. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(50):149–150. doi: 10.1080/09688080.2017.1335999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]