Abstract

BACKGROUND

Spinal subdural empyemas are a rare presentation of rapid neurological decline, progressing from radiculopathy to complete paralysis and sensory loss. Although pathogenic mechanisms have been hypothesized, their occurrence in this population of patients remains unclear.

OBSERVATIONS

The authors present the third documented case of an isolated spinal subdural empyema of unclear etiology in an immunocompetent patient with no established risk factors.

LESSONS

Successful treatment requires prompt clinical suspicion, radiological diagnosis, and surgical evacuation along with empirical antibiotic treatment. Radiological clarification of the subdural versus the epidural location of the empyema is difficult, while intraoperative durotomy for exploration risks subdural dissemination. In these cases, intraoperative ultrasonography would be a useful adjunct and decision aid.

Keywords: spinal subdural empyema, intraoperative sonography, immunocompetent, spinal infection, subdural empyema

ABBREVIATIONS: ICU = intensive care unit, IV = intravenous, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Subdural empyema, a loculated collection of purulence between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater, can present within the cranial vault or, in very rare cases, within the spine.1, 2 Interposed between the spinal epidural space and the intramedullary compartment, the spinal subdural space is contiguous across segments, making it prone to rapid and extensive colonization.2, 3 This results in a spectrum of diseases ranging from cord infarction to profound neurological deficit within 48 hours, particularly if not treated expeditiously with antibiotics and often surgical drainage.2, 4

The rarity of spinal subdural empyema has conferred a paucity of literature since its initial description in 1927 by Sittig.5, 6 With fewer than 80 reported cases, the pathogenesis is poorly understood, with prevalent theories revealing a predominant incidence in those with chronic sinus infections and immunosuppressive conditions (including diabetes, malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and intravenous [IV] drug use).7, 8 The following case illustrates a recent experience in a patient with an isolated spinal subdural abscess and, to our knowledge, the third case in the published literature without an underlying etiology or risk factors in an immunocompetent patient.9

Illustrative Case

History

A 55-year-old right-handed woman working as an industrial cleaner presented to the emergency department with a 48-hour history of rapidly progressive right-predominant dense quadriparesis in the setting of clinical and biochemical sepsis. Associated symptomatology included a subjectively swollen and tender right ankle, as well as systemic manifestations of infection, including fevers, without other focal neurological manifestations or alternative foci of infection.

Aside from a mechanical fall over a vacuum cleaner 4 weeks earlier, the patient had no history of prior trauma, no historical risk factors of immunocompromise, and no exposure to atypical infections in the way of sick contacts or travel history. The patient’s past medical history included a total right knee replacement 7 years earlier for premature osteoarthritis attributed to her occupation, bilateral breast augmentation, and hypertension.

Examination

Upon transfer to our quaternary neurosurgery center, the patient had hemodynamic parameters within normal limits and was apyretic. A neurological examination demonstrated dense, flaccid quadriparesis, with 3/5 power distally and 1/5 power proximally in the upper limbs. Her lower-limb powers were 1/5 globally. Reflexes were diminished but present globally, with no features of hypertonia or clonus. Sensation was diminished below the T1 level. The patient had a grossly swollen and erythematous right ankle, which was tender on passive movement.

Biochemistry

The patient’s serum laboratory tests revealed leucocytosis with predominant neutrophilia and a mild lymphocytopenia (white blood cell count: 29.36 × 109/L, neutrophils: 27.45 × 109/L, lymphocytes: 0.93 × 109/L). Ancillary tests included a C-reactive protein value of 296 mg/L, with preserved renal function and mild liver dysfunction with elevation of cholestatic markers (estimated glomerular filtration rate > 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, alanine aminotransferase: 48 U/L, bilirubin: 20 U/L, alkaline phosphatase: 605 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase: 249 U/L). Preliminary preoperative cultures of blood, urine, and sputum upon admission were negative. An aspiration of the right ankle joint was macroscopically clean, with no evidence of bacteria on microscopy or growth upon culture.

Imaging

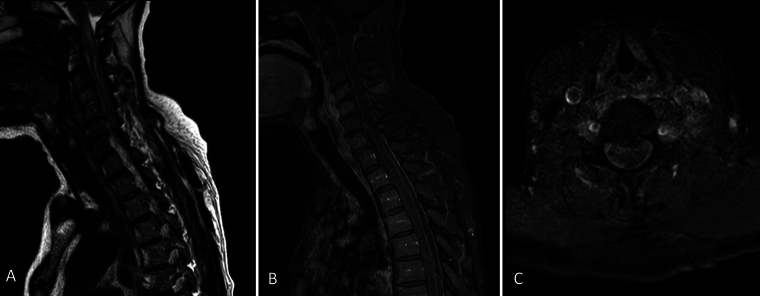

A preliminary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of her whole spine showed C4–5 osteomyelitis and discitis, extensive arachnoiditis, and multiple loculated epidural collections throughout the spinal column (Fig. 1). Of the latter, the most compressive regions included a dorsal C5–6 and a left ventral C2–3 collection. Associated with the above was cord signal hyperintensity extending from the craniocervical junction to the C7 level, with an equivocal cord signal from C7 to T3.

FIG. 1.

Index preoperative midsagittal T2-weighted (A) and gadolinium T1-weighted (B) MRI of the cervical and upper thoracic cord. Axial gadolinium T1-weighted MRI (C) at the level of C5–6.

Operation

The patient was initiated on empirical antibiotics (IV cefepime 2 g twice a day, IV vancomycin 1 g twice a day, and IV metronidazole 400 mg 3 times a day) and underwent an emergency C2–7 laminectomy on the day of admission, with intraoperative findings of a probable phlegmonous collection dorsally, overlying the theca at the level of C2. There were small amounts of inflammatory fluid in the epidural space, with no overtly purulent material encountered. Because the patient did not have overt meningism, subdural exploration was avoided and durotomy was not performed. At the conclusion of the decompression, there was minimal but present pulsatility of the cervical cord.

Postoperative Course

The patient was subsequently transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for routine neurointensive perioperative care, with spinal perfusion prioritized and mean arterial pressure targets of at least 80 mm Hg. Interestingly, it was only during her postoperative period in the ICU that delayed growth of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus was noted sporadically in serially drawn culture bottles.

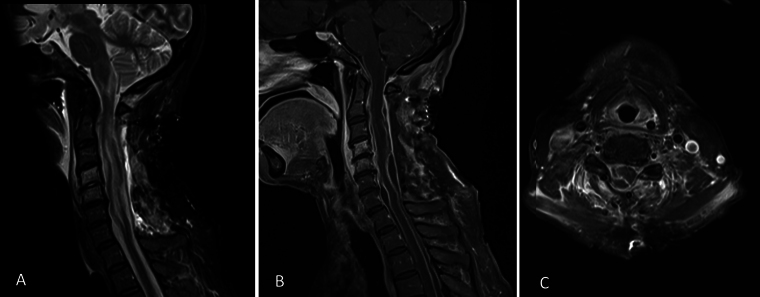

Following an initial improvement of her upper-limb strengths to 4–/5 distally and 2/5 proximally within the ensuing 48 hours postoperatively, the patient’s power regressed significantly, prompting repeat MRI of her spine. Aside from a small volume of restricted diffusion in the left inferior cerebellum, there were findings of a residual, multiloculated subdural collection in the cervical area causing cord flattening, as seen in Fig. 2. There was progression of high cervical cord edema, with an extension of signal change into the inferior medulla, with persistent thoracic and lumbosacral subdural collections, which were not of significant neural element compromise.

FIG. 2.

First postoperative midsagittal T2-weighted (A) and gadolinium T1-weighted (B) MRI of the cervical and upper thoracic cord. Axial gadolinium T1-weighted MRI (C) at the level of C5–6.

The patient was returned to the operating room for a C2–7 longitudinal durotomy for evacuation of the subdural empyema. Frank purulence under pressure within the subdural space was released. The cervical cord was grossly inflamed and intimately adherent to the thecal sac at various junctions, resulting in multiple loculated collections. Membranes of these collections were fenestrated. A 1.5-mm external ventricular drain was advanced subdurally into the thoracic region below the limits of the durotomy to carefully lavage purulent fluid.

The patient remained in the ICU postoperatively for 15 days, during which the microbiological etiology was identified to be methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, prompting rationalization of the IV antibiotics to IV flucloxacillin. The patient was eventually transferred to the state rehabilitation center, prior to which her neurological examination had improved to 4/5 power throughout the left upper limb, 3/5 in the right upper limb distally, and 2/5 in the right upper limb proximally. She remained paraplegic, with a positive bulbocavernous reflex.

Patient Informed Consent

The necessary patient informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Spinal subdural empyemas are a rare presentation of rapid neurological decline, with an unknown incidence, as opposed to the more common spinal epidural empyemas.10, 11 Fewer than 80 cases have been reported in the literature, of which the majority occurred in the pediatric population.11 A relative rise in incidence in recent decades could be attributable to the development of and improved access to refined MRI.12 Before the advent of modern radiological techniques, diagnosis required clinical and biochemical suspicion, a positive lumbar puncture, or myelographic block.12 The natural progression from pyrexia, with or without radiculopathy, to mild sensorimotor or sphincter dysfunction and finally to paralysis with complete sensory loss occurs expeditiously.12 Thus, quickly establishing an accurate diagnosis is of paramount importance to ensure better treatment outcomes. The mainstay of treatment for spinal subdural empyemas remains surgical evacuation and targeted antibiotic treatment.12–14

The gold-standard investigation for a suspected spinal subdural empyema is whole-spine MRI with pre- and postgadolinium contrast administration sequences.12, 13 Classically, subdural empyemas are intradural, extramedullary, peripherally enhancing collections that are separated from normal epidural fat by contrast-enhancing dura.11 Often, there is pial enhancement along the medullary boundaries of subdural empyemas.11

Observations

In the abovementioned patient, whole-spine MRI demonstrated multiple loculated collections with extensive arachnoiditis. However, the exact location of the empyemas was difficult to establish on imaging and was thought to predominate in the epidural space. Intraoperatively, a small volume of epidural inflammatory fluid without obvious purulence was encountered. Although the thickened, discolored dura could have indicated subdural involvement, this poses a dilemma. If the subdural space was sterile, an exploratory durotomy could cause intradural dissemination of the infection. Given the pulsatility of the theca upon evacuation of the epidural collection, suggesting elimination of significant compression, a decision was made not to explore the subdural space. In retrospect, the presence of radiological arachnoiditis, dorsal compression, and the minimal extradural purulent material encountered intraoperatively should have prompted subdural exploration despite the absence of meningism.

Intraoperative ultrasonography, historically used in intracranial tumor resections, has gained traction in spinal operations in recent decades.15 First utilized by Reid in 193816 to preoperatively evaluate an intradural intramedullary tumor via interlaminar spaces of the neck, modern sonographic equipment allows for intraoperative anatomical mapping of various structures, both normal and pathological, including the spinal cord, central canal, spinal arteries, tumors, and syringes.15 Thus, it has been used widely in spinal tumor resections, cerebrospinal fluid disorders, spinal traumas, spinal neurovascular surgeries, and instrumentation.15 However, its utility in spinal subdural infection has not been previously published.

Lessons

We hypothesize that ultrasonographic features are likely to mirror those seen in intracranial infective pathologies, particularly in the case of infantile cranial subdural empyemas.17 Compared to anechoic cerebrospinal fluid collections (such as hygromas and arachnoid cysts), infected collections are likely to demonstrate increased echogenicity, with hyperechoic fibrinous strands, thickened inner membranes, and the pia-arachnoid interface.17 In this case, intraoperative sonography would have been invaluable when considering the risks of durotomy and subdural exploration. Evidence of subdural loculations and the aforementioned ultrasonographic features would have likely warranted subdural evacuation in the first operation itself.

Another interesting aspect of this case was the likely etiology of an isolated spinal subdural empyema in the absence of risk factors and no other confirmed focus of infection. There is significant overlap between established risk factors for spinal epidural and subdural empyemas and a predominant incidence among patients who are relatively or otherwise immunocompromised (including those with diabetes, alcoholism, chronic corticosteroid use, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infections), as well as active drug users and patients with recent spinal procedures (including acupuncture, lumbar puncture, spinal surgery, and epidural anesthesia).7, 8, 18

In the absence of prior spinal operations, and therefore in noniatrogenic cases, the pathogenesis of spinal subdural empyemas is not entirely clear. Various theories have been proposed, the most prevalent of which suggests hematogenous seeding from a peripheral source of infection.11 Alternatively, locoregional spread from osteomyelitis of vertebral elements or via hematogenous inoculation during the course of meningitis has been implicated.13 Once within the subdural space, which runs from the foramen magnum throughout the spine interrupted only by penetrating vessels and nerves, its contiguous nature allows for rapid longitudinal dissemination.14

In this case, the etiology of the patient’s spinal subdural hematoma remains unclear. In a septic patient with a significant intradural infection burden, there was no other clinical focus of infection, with negative blood cultures and sputum samples preoperatively. Although the patient did have a swollen ankle, there was no radiological evidence of osteomyelitis or biochemical confirmation of septic arthritis upon needle aspiration. With regard to her fall approximately a month preceding her presentation, our hypothesis is that a small volume of noncompressive spinal epidural hematoma may have occurred, with a subsequent superimposed infection, as seen in previously published cases.19 However, it remains unclear why epidural samples from the first operation did not yield bacterial growth.

Overall, spinal subdural empyemas are a rare presentation of rapid neurological decline, ranging from profound neurological deficit to cord infarction, and depend upon timely diagnosis and, subsequently, management to optimize patient outcomes.1, 2 We have presented the third documented case of spinal subdural empyema in an immunocompetent patient without established risk factors or etiology.9 Although various theories have been proposed, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms in this population remain a mystery.11, 13 The mainstay of treatment is surgical drainage and targeted antibiotics.12 However, as seen in this case, radiological clarification of the subdural versus epidural location of empyema is not always distinct and necessitates clinical gestalt and intraoperative decision-making to consider subdural exploration. Intraoperative sonography would be an invaluable adjunct in this dilemma.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Thiruvengadam, Khoo. Acquisition of data: Thiruvengadam. Analysis and interpretation of data: Thiruvengadam. Drafting the article: Thiruvengadam. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Thiruvengadam. Administrative/technical/material support: Thiruvengadam, Khoo. Study supervision: Khoo, Saha.

Correspondence

Shreyas Thiruvengadam: Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, Western Australia. shreyasthiru@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bartels RH, de Jong TR, Grotenhuis JA. Spinal subdural abscess: case report. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(2):307-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortazavi MM, Quadri SA, Suriya SS, et al. Rare concurrent retroclival and pan-spinal subdural empyema: review of literature with an uncommon illustrative case. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:326-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandler AL, Thompson D, Goodrich JT, et al. Infections of the spinal subdural space in children: a series of 11 contemporary cases and review of all published reports. A multinational collaborative effort. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(1):105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin RJ, Yuan HA. Neurosurgical care of spinal epidural, subdural, and intramedullary abscesses and arachnoiditis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(1):125-136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy ML, Wieder BH, Schneider J, Zee CS, Weiss MH. Subdural empyema of the cervical spine: clinicopathological correlates and magnetic resonance imaging. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 1993;79(6):929-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sittig O. Metastatischer Rückenmarksabsceß bei septischem Abortus. Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. 1927;107(1):146-151. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marciano RD, Buster W, Karas C, Narayan K. Isolated spinal subdural empyema: a case report & review of the literature. Open J Mod Neurosurg. 2017;7(3):112-119. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vural M, Arslantaş A, Adapinar B, et al. Spinal subdural Staphylococcus aureus abscess: case report and review of the literature. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;112(5):343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorar M, Er U, Seçkin H, Ozturk MH, Bavbek M. Spinal subdural abscess: a rare cause of low back pain. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(3):292-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadjipavlou AG, Mader JT, Necessary JT, Muffoletto AJ. Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine. 2000;25(13):1668-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngwenya LB, Prevedello LM, Youssef PP. Concomitant epidural and subdural spinal abscess: a case report. Spine J. 2016;16(4):e275-e282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilkington SA, Jackson SA, Gillett GR. Spinal epidural empyema. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17(2):196-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tompkins M, Panuncialman I, Lucas P, Palumbo M. Spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(3):384-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenlee JE. Subdural empyema. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5(1):13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganau M, Syrmos N, Martin AR, Jiang F, Fehlings MG. Intraoperative ultrasound in spine surgery: history, current applications, future developments. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018;8(3):261-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reid MH.Ultrasonic visualization of a cervical cord cystic astrocytoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1938;131(5):907-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CY, Huang CC, Chang YC, Chow NH, Chio CC, Zimmerman RA. Subdural empyema in 10 infants: US characteristics and clinical correlates. Radiology. 1998;207(3):609-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velissaris D, Aretha D, Fligou F, Filos KS. Spinal subdural staphylococcus aureus abscess: case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2009;4(1):1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inamasu J, Shizu N, Tsutsumi Y, Hirose Y. Infected epidural hematoma of the lumbar spine associated with invasive pneumococcal disease. Asian J Neurosurg. 2015;10(1):58-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]