Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a pathogen associated with severe respiratory infections. The ability of S. aureus to internalize into lung epithelial cells complicates the treatment of respiratory infections caused by this bacterium. In the intracellular environment, S. aureus can avoid elimination by the immune system and the action of circulating antibiotics. Consequently, interfering with S. aureus internalization may represent a promising adjunctive therapeutic strategy to enhance the efficacy of conventional treatments. Here, we investigated the host-pathogen molecular interactions involved in S. aureus internalization into human lung epithelial cells. Lipid raft-mediated endocytosis was identified as the main entry mechanism. Thus, bacterial internalization was significantly reduced after the disruption of lipid rafts with methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Confocal microscopy confirmed the colocalization of S. aureus with lipid raft markers such as ganglioside GM1 and caveolin-1. Adhesion of S. aureus to α5β1 integrin on lung epithelial cells via fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs) was a prerequisite for bacterial internalization. A mutant S. aureus strain deficient in the expression of alpha-hemolysin (Hla) was significantly impaired in its capacity to enter lung epithelial cells despite retaining its capacity to adhere. This suggests a direct involvement of Hla in the bacterial internalization process. Among the receptors for Hla located in lipid rafts, caveolin-1 was essential for S. aureus internalization, whereas ADAM10 was dispensable for this process. In conclusion, this study supports a significant role of lipid rafts in S. aureus internalization into human lung epithelial cells and highlights the interaction between bacterial Hla and host caveolin-1 as crucial for the internalization process.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-024-05472-0.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Human lung epithelial cells, Lipid rafts, Bacterial internalization, Alpha-hemolysin, Caveolin-1

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is an important cause of lung infections and a leading cause of ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units [1, 2]. The respiratory epithelium spans both the upper and lower airways and extends into the lung alveoli. This broad coverage positions lung epithelial cells as the first point of contact with respiratory pathogens, including S. aureus. In this regard, several studies have confirmed the ability of S. aureus to internalize within lung epithelial cells [3–7]. This internalization strategy potentially shields S. aureus from the attack of professional phagocytic cells, which would otherwise aim to eliminate the extracellular bacteria [3–7]. In addition, internalized S. aureus can evade the killing effects of circulating antibiotics, as these antimicrobial agents may have limited access to the intracellular compartment [3–7]. Suboptimal intracellular antibiotic concentrations can lead to reduced efficacy in eliminating intracellular S. aureus and promote pathogen persistence. The suboptimal antibiotic concentrations can also create an environment that favors the selection and survival of antibiotic-resistant strains. Unlike professional phagocytic cells such as macrophages and neutrophils, epithelial cells are generally considered to be non-phagocytic. The traditional role of respiratory epithelial cells is to form protective barriers and to orchestrate the immune response to pathogens rather than actively engulf and digest them [8]. Therefore, the process of bacterial internalization into respiratory epithelial cells is often self-promoted by the pathogen [9]. Despite the recognized ability of S. aureus to internalize into lung epithelial cells, the precise mechanism of bacterial entry remains an active area of research. Identifying and targeting the molecular events involved in bacterial internalization may provide potential avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The internalization of pathogens into eukaryotic cells can occur through several cellular processes, including clathrin-mediated and clathrin-independent endocytosis [10]. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is a fundamental cellular process used by eukaryotic cells for the internalization and recycling of surface receptors [11]. The initiation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis is characterized by the formation of coated pits, which are enriched with clathrin and other associated proteins, at the cell surface [11]. The coated pits invaginate from the cell surface, resulting in the formation of coated vesicles containing cargo molecules inside of the cells [11]. The internalized cargo, which may include receptors, can be recycled back to the cell surface or targeted to specific cellular compartments for degradation. Although the primary role of the clathrin machinery is to internalize cell surface receptors to regulate their abundance on the cell surface [12], it is often manipulated by pathogens to gain access into host cells [13, 14]. A possible role for clathrin-dependent endocytosis has been proposed for the entry of S. aureus into osteoblasts [15].

Clathrin-independent endocytosis, on the other hand, allows the cell to internalize a wide variety of cargo, including extracellular ligands, receptors, and pathogens, without relying on the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles [16]. The majority of clathrin-independent endocytic pathways take place in lipid rafts, which are specialized membrane microdomains that are enriched with cholesterol, glycophospholipids, and lipid-anchored membrane proteins [17, 18]. Many pathogens exploit lipid rafts for entry into host cells [19–25]. Pathogens that enter host cells via lipid rafts follow a different pathway than clathrin-dependent endocytosis [26]. Whereas the endocytic vesicles formed by clathrin-dependent endocytosis are typically targeted to intracellular compartments that fuse with lysosomes, pathogens entering host cells via lipid rafts are targeted to intracellular compartments that do not fuse with lysosomes [26]. Therefore, pathogens may strategically use lipid rafts as entry points to evade intracellular degradation and survive within the host cell. In this regard, internalization of S. aureus in fibroblasts has been reported to be mediated by sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich lipid rafts [27].

The interactions between S. aureus and host cells are highly complex and can vary depending on the specific cell type involved. Different cell types express unique sets of receptors and signaling pathways that can influence the dynamics of infection. The primary objective of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms by which S. aureus internalizes into human lung epithelial cells. Our results provide compelling evidence for an important role of lipid rafts in bacterial internalization. The key finding of this study is that alpha-hemolysin (Hla) released by S. aureus specifically interacts with caveolin-1 within lipid rafts in the host cell membrane and that this interaction is critical for bacterial internalization. Hla is a major pore-forming toxin secreted by S. aureus and has been reported to interact with lipid rafts in host cells [28–30]. Caveolin-1 is one of the principal structural proteins associated with lipid rafts and acts as a scaffold or organizing platform for the assembly of these membrane microdomains [31]. The results of our study suggest a model in which Hla produced by S. aureus interacts with caveolin-1 on lung epithelial cells, leading to lipid raft formation in the host cell membrane and bacterial internalization.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The strains of S. aureus used in this study were S. aureus strain SH1000 [32], the Hla-deficient (hla) mutant strain [33], S. aureus 8325-4 and its fibronectin-binding protein A-deficient (FnBPA) derivative [34], S. aureus USA300 [35] and the clinical isolates SA102, SA103, SA112, SA138 and SA302 obtained from our strain collection. S. aureus strains were grown to mid-log phase in Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) medium (Roth) at 37 °C with shaking (120 rpm). Bacteria were collected by centrifugation, washed with sterile PBS, and diluted to the required concentration.

For carboxyfluorescein labeling of S. aureus, a bacterial suspension (5 × 108/ml) was incubated with 200 µg/ml of carboxyfluorescein (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark. Labeled bacteria were washed three times before use.

Culture of human lung epithelial cells

The human adenocarcinomic alveolar basal epithelial cells A549 (ATCC CCL-185) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FCS and the immortalized human bronchial basal epithelial cells CI-huBroBECs (InSCREENeX; #INS-CI-1025) were cultured in huBroBEC medium (InSCREENeX; #INS-ME-1033). Cells were incubated in 5% CO2 in an air-humidified incubator at 37 °C. The media was changed every 2 days, and cells were passaged when they were approximately 80% confluent.

Antibodies and reagents

The following antibodies and reagents were used in this study: mouse anti-caveolin-1 (BD Bioscience); mouse anti-lysosomal-associated membrane protein (LAMP-1) antibody (BD Bioscience); cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568 (Thermo Fisher Scientific); Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific); BODIPY 493/503 (Thermo Fisher Scientific); and Alexa Fluor 594 cholera toxin subunit B (CT-B) conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The rabbit polyclonal anti-S. aureus antibodies used in this study were custom-made.

Infection assay for quantification of viable intracellular S. aureus

Human lung epithelial cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates (Nunc) (5 × 105 cells/well) and infected with S. aureus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of five bacteria per cell (106 bacteria/well). The multiplicity of infection of 5 bacteria per eukaryotic cell was identified in preliminary experiments as the optimal MOI that balances sufficient infection of lung epithelial cells and host response to initial infection with minimal cytotoxic effects for the host cells. Plates were centrifuged at 800 x g for 1 min to synchronize infection. After 2 h of infection, lysostaphin (2 µg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and cells were incubated for 10 min to remove non-internalized extracellular bacteria. Cells were then washed twice with sterile PBS and lysed at the indicated times by incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100 in double-distilled H2O for 5 min. The number of viable bacteria was determined by plating serial dilutions on blood agar plates. The limit of detection was less than 50 CFU/ml.

In some experiments, lung epithelial cells were incubated with either 10 µM or 30 µM Pitstop 2 (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis [36], 100 µM RGD peptide (GLY-ARG-GLY-ASP-SER-PRO) (Sigma Aldrich) to block the binding of fibronectin to host integrin α5β1 [37] or with reverse sequence RGD peptide as a negative control, 10 mM of cholesterol-depleting agent methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβDC; Sigma-Aldrich), 50 nM or 100 nM of the selective disruptor of caveolin-1 oligomers WL47 [38], and 1–10 µg of a caveolin-1 blocking peptide (Bio-Connect). Cells were preincubated with these compounds for 1 h before and during infection at the indicated concentrations while control cells were incubated with vehicle only.

Infection assay for fluorescence microscopy

Human lung epithelial cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well tissue culture plates (Nunc) in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS to obtain sub-confluent cell monolayers. The cells were infected with S. aureus at a MOI of five bacteria per cell. At the indicated time points of infection, the coverslips were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at RT. Prior to fluorescence labeling, the coverslips were first washed with 10 mM glycine in PBS to quench free aldehyde groups, followed by two washes with PBS and were then blocked in 10% FCS-PBS for 45 min. Infected cells on coverslips were stained as described below. Stained coverslips were washed with PBS and mounted on glass microscope slides using Prolong Gold antifade mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (with or without DAPI), sealed with nail polish and stored at 4 °C.

Samples were analyzed either using either a Zeiss Imager A2 (Zeiss, Germany) with a 63x/1.25 oil Ph3 (Plan Neofluar) or a 100x/1.25 oil Ph3 (Plan Neofluar) objective and an Axiocam MRm camera or under a Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning confocal upright microscope (Leica Microsystems) with an HC PL APO 63×/1.40 oil immersion objective and two lasers, diode (405) and argon (488 nm), and the LAS AF software. The image analysis was performed using Zeiss Zen 2011 blue software for images taken with Zeiss Imager A2 or with Fiji/ImageJ [39] for images taken with Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning confocal.

Double immunofluorescence staining for detection of extracellular/intracellular S. aureus

After the blocking step described above, the coverslips were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of rabbit S. aureus antiserum (primary antibody) for 1 h without washing. After three washes with PBS, samples were incubated with secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:150) for 45 min to stain extracellular bacteria. The coverslips were then washed three times, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, washed twice and incubated again with the primary antibody for 1 h to stain intracellular S. aureus. After three washes, samples were incubated with secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:150). Coverslips were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 400 Phalloidin (1:200) for 45 min to visualize F-actin. Coverslips were washed three times before mounting.

For interpretation of the double immunofluorescence images, extracellular bacteria that were initially stained green will appear yellow after the second staining due to the overlap of green and red fluorescence. Intracellular bacteria will appear red because they are stained only with the red fluorescent antibody after permeabilization.

Immunofluorescence staining for the detection of LAMP-1, caveolin-1, and S. aureus

S. aureus-infected lung epithelial cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min and washed twice with PBS before the blocking step. Coverslips were then incubated with either a mouse anti-LAMP-1 antibody (1:50) or a mouse anti-caveolin-1 antibody (1:250) for 1 h, washed twice, and incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:150) secondary antibody. After two washes and incubation with blocking buffer for 5 min, the coverslips were further incubated with rabbit S. aureus antiserum (1:100) for 1 h without washing. The samples were washed twice and incubated with Alexa 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:150). Coverslips were washed three times before mounting.

Fluorescence labeling of lipids with BODIPY 493/503

The fluorescence staining of the lipid droplets was performed with BODIPY 493/503 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacture’s recommendations.

Fluorescent labeling of ganglioside GM1 using cholera toxin B subunit (CTB)

S. aureus-infected lung epithelial cells were incubated with CTB (1:50) for 20 min, washed twice, blocked for 5 min and further incubated with rabbit anti-S. aureus antibody (1:100) for 30 min without washing. After incubation, the samples were washed twice and incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:150) secondary antibody. Coverslips were washed three times before mounting. No permeabilization of the cell membranes was performed during this labeling. Thus, only extracellular bacteria were labeled.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

S. aureus-infected and uninfected control lung epithelial cells were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde and 5% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M EM-HEPES. After fixation, cells were washed twice with TE buffer (20 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 6.9]) and dehydrated with a graded series of acetone (10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 100%) for 15 min on ice. Samples in the 100% acetone were allowed to reach room temperature before being placed in 100% acetone for a second time. Samples were then critical-point dried with liquid CO2 (CPD 30, Bal-Tec) and coated with a palladium-gold film by sputter deposition (SCD 500, Bal-Tec). Cells were examined with a field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss DSM 982 Gemini) using the Everhart Thornley HESE2 detector and the in-lens SE detector in a 25:75 or 50:50 ratio at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

S. aureus-infected and uninfected control lung epithelial cells were fixed as described above for FESEM. After washing with TE buffer, cells were osmified with 1% aqueous osmium at RT for 1 h. Cells were then dehydrated with a graded series of acetone (10, 30, 50, 70, 90, and 100%) for 30 min at each step. The 70% acetone dehydration step was performed overnight in 2% uranyl acetate. Cells were then infiltrated with an epoxy resin, and ultrathin 70-nm sections were cut with a diamond knife. Sections were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a TEM910 transmission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss) at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV. Images were taken at calibrated magnifications using a line replica and digitally recorded with a slow scan CCD-Camera (ProScan) using ITEM software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions). Brightness and contrast were adjusted using Adobe Photoshop CS5.

Immune field emission scanning electron microscopy (Immune-FESEM)

S. aureus-infected and uninfected control lung epithelial cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M EM-HEPES for 1 h, washed first with 10 mM glycine in PBS to quench free aldehyde groups, and then washed twice with PBS. The cells were first incubated in 10% FCS-PBS for 45 min for blocking and then with 50–100 µg/ml of purified anti-Hla rabbit IgG (S7531, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h. After several washes with PBS, the cells were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-gold conjugated (particle size 15 nm) in BBI solution for 30 min. After washing with TE buffer, cells were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde in TE and dehydrated in graded series of acetone, as described for TEM. Cells were then coated with a thin carbon layer using a Bal-Tec MED 020 (Liechtenstein), which allows the detection of colloidal gold particles on bacterial and cellular surfaces without charging problems, and were finally examined in a field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss DSM 982 Gemini) using the Everhart Thornley HESE2 detector or the In-lens SE detector at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 software. Differences between two groups were determined using a Student’s t-test. Groups of three or more were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

S. aureus efficiently internalizes into human lung epithelial cells

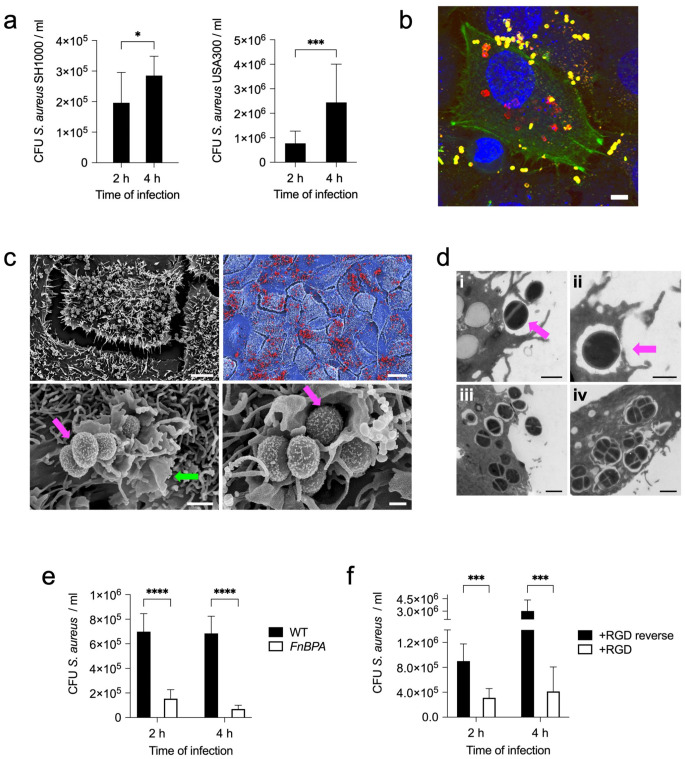

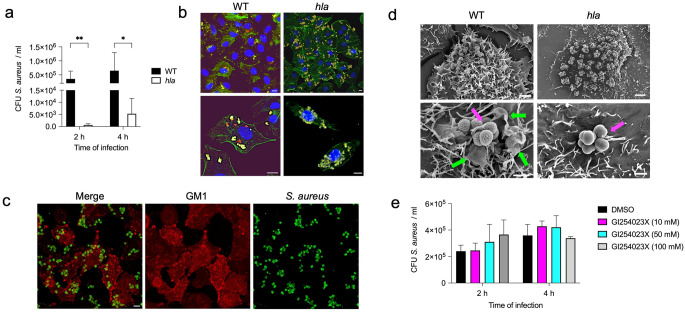

The capacity of S. aureus to internalize into human lung epithelial cells was first evaluated using a lysostaphin-protection assay. In the experimental setup, A549 cells were infected with either S. aureus strain SH1000 or S. aureus strain USA300. The infection period lasted for 2 h to allow the bacteria to interact and internalize into the host cells. After the 2 h infection period, lysostaphin was added to selectively kill extracellular bacteria while sparing those that had successfully entered the A549 cells. The first set of samples was processed immediately after 10 min of lysostaphin treatment (time point 2 h). This rapid disruption allowed the number of viable intracellular bacteria to be determined at the initial 2 h time point. Another set of samples was incubated for an additional 2 h after lysostaphin treatment (a total of 4 h from the beginning of infection). This additional incubation period provided insight into the fate of intracellular bacteria over a longer period of time. Both S. aureus strain SH1000 and S. aureus strain USA300 showed efficient internalization into A549 cells after 2 h of infection (Fig. 1a). The number of intracellular viable bacteria increased significantly between 2 h and 4 h of infection (Fig. 1a), indicating that intracellular S. aureus was also able to replicate within A549 cells. The ability of S. aureus to internalize within human lung epithelial cells was further confirmed using the immortalized human bronchial basal epithelial cells CI-huBroBECs (Supplementary Fig. S1a). The presence of intracellular bacteria in A549 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S2a-e) or in CI-huBroBECs cells (Supplementary Fig. S1b) was also demonstrated by confocal microscopy. The confocal microscopy images depicted in these figures show substantial numbers of S. aureus internalized within the epithelial cells (red fluorescence) along with extracellular bacteria adhered to the cell surface (yellow fluorescence). Examination of infected A549 by scanning electron microscopy revealed abundant S. aureus bacteria attached to the cell surface (Fig. 1c, upper panels). Large membrane raffles were observed on the surface of the A549 cells surrounding the attached bacteria (Fig. 1c, lower panels). The transmission electron microscopy images in Fig. 1d show S. aureus at different stages of internalization into A549 cells. The earlier step is the attachment to the host cells and the induction of host cell membrane ruffles surrounding the attached bacteria (i). The resulting membrane ruffles formed in this process then collapse onto the plasma membrane, where they fuse together (ii) and then split to form intracellular vacuoles (iii). Within these vacuoles, S. aureus can replicate, leading to the formation of bacterial clusters (iv).

Fig. 1.

S. aureus adheres to and internalizes into human lung epithelial cells. a Quantification of viable intracellular S. aureus strain SH1000 (left panel) and S. aureus strain USA300 (right panel) in A549 cells at 2 h and 4 h of infection. b Double immunofluorescence staining image of A549 cells infected with S. aureus SH1000 at 4 h of infection showing the intracellular bacteria in red, extracellular bacteria in yellow, actin in green and DNA in the nucleus is stained in blue. The scale bar represents 5 μm. c Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) photographs showing A549 cells infected with S. aureus SH1000 (4 h) at different magnifications. The photograph in the upper right panel is a digitally colorized version showing a detail of the image in the left panel with S. aureus bacteria colored in red and A549 cells colored in blue. Magenta arrows indicate S. aureus bacteria and green arrow indicates membrane ruffles. Scale bars represent 5 μm for the upper left panel, 20 μm for the upper right panel and 0.5 μm for the lower panels. d Transmission electron microscopy images showing adhesion (i), engulfment (ii), internalization (iii), and replication (iv) of S. aureus SH1000 in A549 cells. Scale bars represent 1 μm for (i) and (iv) and 0.5 μm for (ii) and (iii). e Quantification of viable intracellular S. aureus strain 8325-4 wild-type (WT) (black bars) and S. aureus strain 8325-4 deficient in fibronectin-binding protein A (FnBPA) expression (white bars) at 2 h and 4 h of infection. f Quantification of viable intracellular S. aureus strain SH1000 within A549 cells treated with either RGD peptide (white bars) or with RGD reverse peptide as negative control (black bars). Each bar in a, e and f represents the mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001

Adhesion to human lung epithelial cell surface via FnBPs is required for S. aureus internalization

Adhesion of S. aureus to the surface of lung epithelial cells may be a critical step that precedes bacterial internalization. Fibronectin-biding proteins (FnBPs) are widely recognized as the major adhesins of S. aureus [40–44]. FnBPs, expressed on the surface of S. aureus, bind to fibronectin, which in turn binds to the α5β1 integrin on the surface of the host cell [42]. Thus, fibronectin serves as a bridge between FnBPs on S. aureus and α5β1 integrin on the host cell and facilitates a close interaction between the bacterium and the host cell. FnBPs have been shown to be involved in S. aureus adhesion to human respiratory epithelial cells [9, 45]. To determine the relevance of bacterial attachment via FnBPs for the internalization of S. aureus into human lung epithelial cells, we evaluated the internalization capacity of a mutant S. aureus strain deficient in the expression of fibronectin-binding protein A (FnBPA). Adhesion of S. aureus FnBPA to the surface of A549 cells was significantly reduced compared to wild-type S. aureus, indicating that FnBPA is a major factor in mediating bacterial attachment to these cells (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, the lack of FnBPA expression also resulted in a significant reduction in the number of internalized bacteria at 2 h and 4 h of infection (Fig. 1e). Thus, the initial adhesion of S. aureus to the lung epithelial cell surface via FnBPA appears to be an essential step for subsequent internalization. To further corroborate this requirement, we evaluated the effect of blocking the host α5β1 integrin with an RGD-containing peptide on bacterial internalization. RGD is a peptide sequence that competitively interacts with α5β1 integrin, preventing its engagement with fibronectin [37]. A significant reduction in S. aureus internalization into A549 cells was observed after treatment with the RGD peptide (Fig. 1f). These data confirmed that attachment to α5β1 integrin on the surface of A549 cells via FnBPA was a prerequisite for subsequent S. aureus internalization.

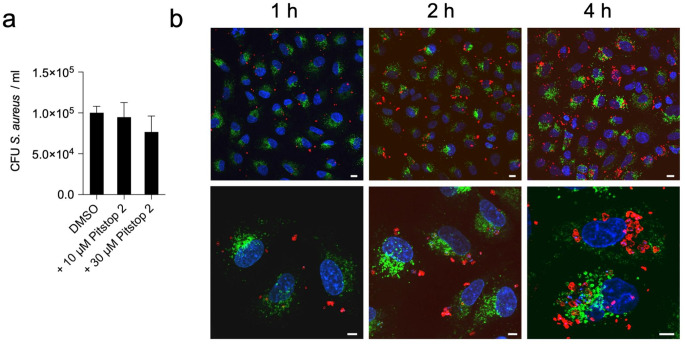

S. aureus internalizes into human lung epithelial cells via a clathrin-independent pathway

After binding to the host cell surface, bacterial internalization can occur via various mechanisms, which can be clathrin-mediated or clathrin-independent [10]. To determine whether S. aureus internalization into lung epithelial cells was clathrin-mediated, we monitored the effect of blocking clathrin-mediated endocytosis on bacterial internalization using the selective inhibitor pitstop 2 [36]. The results in Fig. 2a showed that treatment with two different concentrations of pitstop 2 (10 µM and 30 µM) did not affect the internalization of S. aureus into A549 cells. Therefore, clathrin-dependent endocytosis may not be the primary pathway used by the bacterium to enter human lung epithelial cells.

Fig. 2.

S. aureus internalizes into human lung epithelial cells via a clathrin-independent pathway. a Quantification of intracellular viable S. aureus strain SH1000 at 2 h after internalization into A549 cells treated with either vehicle control DMSO or Pitstop (10 µM and 30 µM). Each bar represents the mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. b Confocal microscopy images of S. aureus SH1000-infected A549 cells at 1 h (left panels), 2 h (middle panels), and 4 h (right panels) postinfection showing LAMP-1 in green, S. aureus in red, and DNA in blue. Scale bars represent 5 μm

While endocytic vesicles generated by clathrin-dependent endocytosis typically fuse with lysosomes, pathogens that enter host cells via clathrin-independent mechanisms such as lipid rafts are targeted to intracellular compartments that do not fuse with lysosomes [26]. The lack of co-localization between intracellular S. aureus and LAMP-1, one of the major proteins associated with phago-lysosomes [46], confirmed that the intracellular compartment where S. aureus resides within lung epithelial cells does not fuse with lysosomes (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. S4). These observations are in contrast to the reported acquisition of LAMP-1 by S. aureus containing vacuoles in immortalized cystic fibrosis tracheal epithelial cells CFT-1 at 1 h after internalization [47]. This discrepancy may be due to different pathways of S. aureus internalization between CFT-1 and the lung epithelial cells used in our study, or to a difference in the physiology between the different cell lines.

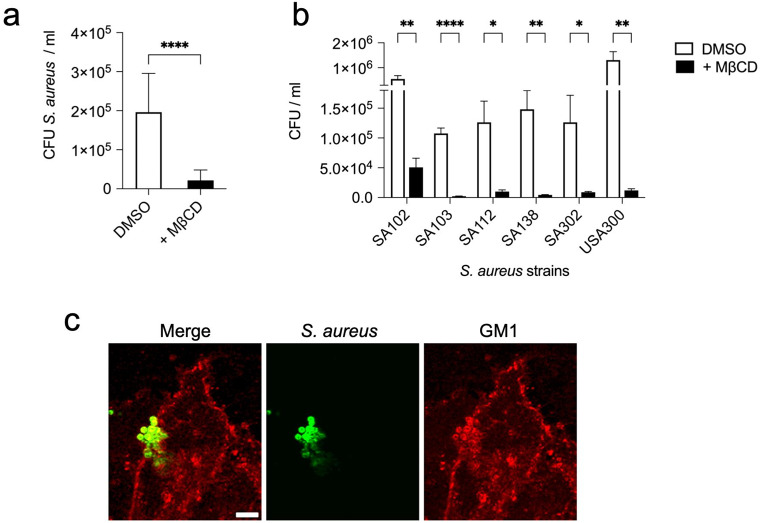

Internalization of S. aureus into human lung epithelial cells is mediated by lipid rafts

Lipid rafts are involved in clathrin-independent endocytic pathways, which are exploited by numerous pathogens for entry into host cells [19–25]. Pathogens internalized via lipid rafts reside in an intracellular compartment that generally do not fuse with traditional lysosomes [26]. Therefore, we investigated the possibility that S. aureus could use lipid rafts to enter the human lung epithelial cells. To this end, we determined the effect of lipid rafts disruption using the cholesterol depleting agent β-methylcyclodextrin (MβCD) [48] on bacterial internalization. The results show that S. aureus internalization was strongly reduced after treatment with MβCD, indicating that lipid rafts play a crucial role in S. aureus entry into A549 (Fig. 3a) or into CI-huBroBECs cells (Supplementary Fig. S5). Furthermore, we observed a reduction in bacterial internalization within A549 cells across different S. aureus clinical isolates after MβCD treatment (Fig. 3b). This indicates that the involvement of lipid rafts is not strain-specific but represents a general mechanism used by S. aureus strains to invade human lung epithelial cells. To further support the use of lipid rafts by S. aureus as an entry mechanism, we examined whether S. aureus colocalized with the lipid raft marker ganglioside GM1 in A549 cells. Colocalization of S. aureus with GM1 was confirmed using cholera toxin B subunit (CTB), which binds specifically to GM1 [49, 50]. In S. aureus-infected A549 cells, CTB-labeled GM1 was recruited to the site where S. aureus was attached to A549 cells (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. S6). Collectively, these results support the involvement of lipid rafts in the entry mechanism of S. aureus into human lung epithelial cells.

Fig. 3.

S. aureus enters human lung epithelial cells via lipid raft-mediated endocytosis. a Quantification of intracellular viable S. aureus strain SH1000 at 2 h after internalization within A549 cells treated with either 10 mM MβCD (black bar) or with DMSO vehicle control (white bar). b Quantification of viable bacteria within A549 cells infected for 2 h with different S. aureus strains and either treated with 10 mM MβCD (black bars) or with DMSO vehicle control (white bars). Each bar in a and b represents the mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ****, p < 0.0001. c Confocal microscopy images of S. aureus SH1000-infected A549 cells showing S. aureus in green (middle panel) and CTB-Alexa Fluor 594-bound to GM1 in red (right panel). A merged image of S. aureus and CTB-GM1 is shown in the left panel. The scale bar represents 5 μm

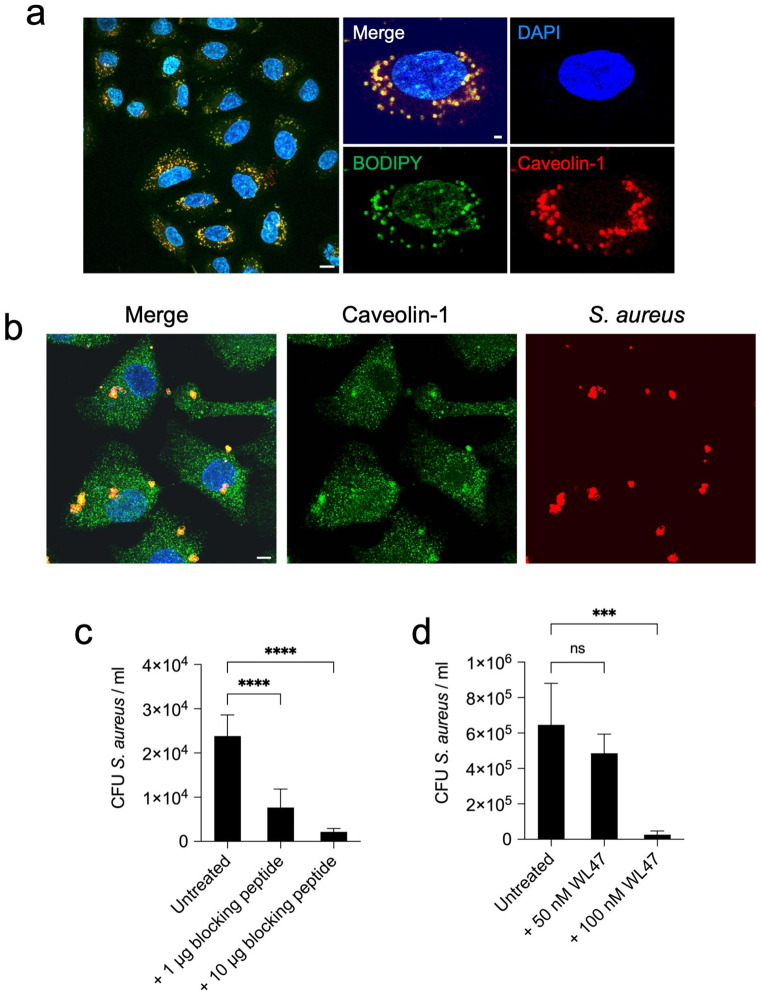

Caveolin-1 mediates the internalization of S. aureus into human lung epithelial cells

Next, we investigated the specific components associated with lipid rafts that may be used by S. aureus to invade human lung epithelial cells. Proteins such as caveolin-1 are enriched in lipid rafts [51], and Hoffmann et al. [27] have reported that caveolin-1 is recruited to the sites of S. aureus attachment in fibroblasts. Therefore, we investigated whether caveolin-1 was also recruited to the site of S. aureus attachment in A549 lung epithelial cells. Since the expression levels of caveolin-1 can vary between different cell types [52], we first determined the expression levels of caveolin-1 in A549 cells. We found that A549 cells expressed high levels of caveolin-1, which colocalized with lipids in the cell membrane (Fig. 4a). Confocal microscopy examination of infected A549 cells revealed colocalization of S. aureus with caveolin-1, suggesting a potential role for caveolin-1 in the internalization process (Fig. 4b). The relevance of caveolin-1 for bacterial internalization was further supported by the dose-dependent reduction in the number of intracellular S. aureus observed after disruption of caveolin-1 functionality with either a blocking peptide that inhibits the interaction of caveolin-1 with potential ligands (Fig. 4c) or with the caveolin-1 oligomer disruptor WL47 (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Caveolin-1 mediates S. aureus internalization into A549 epithelial cells. a Confocal microscopy images of A549 cells stained with BODIPY 493/503 (green) and caveolin-1 (red). DNA in the nucleus is stained in blue. Scale bar represents 5 μm. b Confocal microscopy images of A549 cells infected with S. aureus SH1000 for 3 h and stained with anti-caveolin-1 and anti-S. aureus antibodies. S. aureus appears in red (right panel), caveolin-1 in green (middle panel). S. aureus colocalizing with caveolin-1 appears in yellow in the merged image (left panel). DNA in the nucleus is stained in blue. Scale bar represents 5 μm. Quantification of viable intracellular S. aureus strain SH1000 at 2 h after internalization within A549 cells treated with either 1 µg or10 µg of caveolin-1 blocking peptide (c) or with 50 nM or 100 nM of the high-affinity caveolin-1 disruptor WL47 (d). Untreated cells are used as controls. Each bar in c and d represents the mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001

Hla is crucial for the internalization of S. aureus into human lung epithelial cells

The above results indicated that the interaction of S. aureus with caveolin-1 in A549 cells was critical for bacterial internalization. Therefore, we next investigated the potential virulence determinant of S. aureus that could mediate this interaction. In this regard, Hla is the only virulence factor of S. aureus that has been shown to directly interact with caveolin-1 [53–56]. Hla is a pore-forming protein produced by almost all S. aureus strains and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of S. aureus infections [29]. Hla is secreted as a monomer by S. aureus and forms heptameric pores in the membranes of target host cells [29]. Hla has also been reported to induce extensive clustering of caveolin-1 on the surface of A431 epithelial cells [54]. Based on these observations, we investigated the role of Hla in S. aureus internalization into human lung epithelial cells. We found that a mutant S. aureus strain deficient in the expression of Hla (S. aureus hla) was significantly impaired in its ability to internalize into human lung epithelial cells, as evidenced by the significantly lower numbers of intracellular bacteria detected in infected A549 (Fig. 5a) or in infected CI-huBroBEC cells (Supplementary Fig. S7a) cells at 2 h and 4 h postinfection. Confocal microscopy of infected A549 cells (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S8) and of infected CI-huBroBEC cells (Supplementary Fig. S7b) showed that, in contrast to S. aureus wild-type (WT), S. aureus hla was unable to internalize into human epithelial cells and remained attached to the cell surface.

Fig. 5.

Hla is required by S. aureus for internalization into human lung epithelial cells. a Quantification of intracellular viable S. aureus wild-type (WT) (black bars) and the corresponding S. aureus mutant strain deficient in the expression of Hla (hla) (white bars) within A549 cells at 2 h and 4 h of infection. Each bar represents the mean value ± SD of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01. b Immunofluorescence microscopy images showing A549 cells infected for 4 h with either S. aureus WT (left panels) or with the corresponding Hla-deficient S. aureus strain (right panels). Intracellular bacteria appear red, extracellular bacteria appear yellow, cell actin cytoskeleton appears green and DNA in the nucleus is stained in blue. c Immunofluorescence microscopy images showing A549 cells infected with S. aureus hla for 4 h and stained with CTB-Alexa Fluor 594 to identify GM1. S. aureus appears green (right panel) and CTB-GM1 appears red (middle panel), the merged image is shown in the left panel. Scale bars are 10 μm. d Scanning electron microscopy images showing A549 cells infected with either S. aureus WT (left panels) or with the corresponding Hla-deficient S. aureus strain (right panels) for 4 h. Magenta arrows indicate S. aureus bacteria and green arrow indicates membrane ruffles. Scale bars are 2 μm for the upper left panel, 5 μm for the upper right panel and 1 μm for the lower panels. e Quantification of intracellular viable S. aureus strain SH1000 in A549 cells at 2 h and 4 h of infection treated with either different concentrations of the caveolin-1 inhibitor GI254023X or vehicle DMSO. Each bar represents the mean value ± SD of three independent experiments

Confocal microscopy examination of A549 cells infected with S. aureus hla also revealed a lack of colocalization of S. aureus with CTB-GM1, suggesting that S. aureus hla was unable to induce lipid raft formation at the adhesion site in A549 cells (Fig. 5c). Further examination of A549 cells infected with S. aureus WT or hla by scanning electron microscopy confirmed that S. aureus hla had a comparable capacity to adhere to the surface of A549 cells (Fig. 5d, upper right panel) as S. aureus WT (Fig. 5d, upper left panel). However, in contrast to S. aureus WT (Fig. 5d, lower left panel), S. aureus hla was unable to induce membrane ruffling around the attached bacteria (Fig. 5d, lower right panel). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Hla is required for S. aureus internalization in human lung epithelial cells.

In addition to caveolin-1, ADAM10 has been reported to be a receptor for Hla in lipid rafts [57]. To determine the relevance of ADAM10 in the internalization process, we examined the effect of treating A549 epithelial cells with different concentrations of the ADAM10-specific inhibitor GI254023X [58] on bacterial internalization. The results in Fig. 5e show that inhibition of ADAM10 did not affect the capacity of S. aureus to internalize into A549 cells. These results suggest that ADAM10 is not involved in the interactions of S. aureus with lipid rafts in human lung epithelial cells.

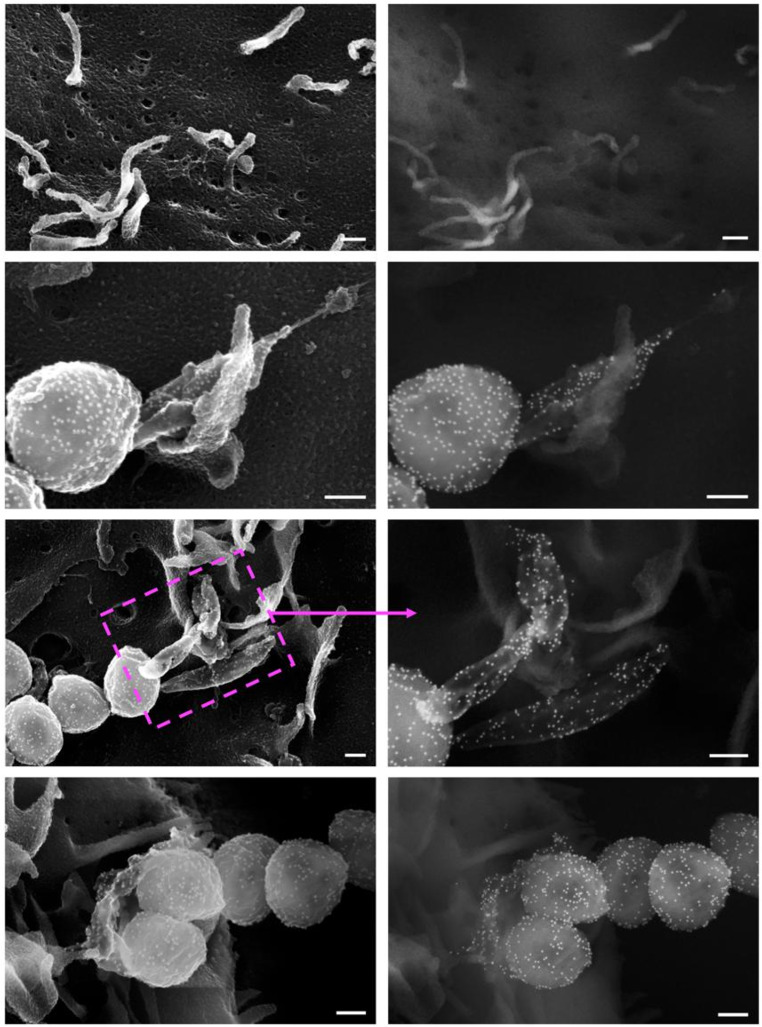

Hla is detected in the membrane ruffles of lung epithelial cells in close proximity to attached S. aureus

S. aureus produces Hla as a soluble monomer that is secreted into the extracellular environment. Hla is secreted by S. aureus via the general secretory pathway and is cleaved at the bacterial cell surface by type I signal peptidase [59]. Therefore, we hypothesized that secreted Hla might interact with caveolin-1 near the bacterial binding site in the membrane of lung epithelial cells, leading to membrane ruffling and bacterial internalization. To test this hypothesis, Hla was labeled in S. aureus-infected A549 cells using anti-Hla antibodies conjugated to gold particles and examined by scanning electron microscopy. The images shown in Fig. 6 confirm the presence of Hla predominantly in the membrane ruffles that are in close proximity to S. aureus in A549 cells.

Fig. 6.

Hla secreted by S. aureus is bound to bacteria-associated membrane ruffles in A549 epithelial cells. FESEM images showing uninfected A549 cells (first row panels) and A549 cells infected with S. aureus SH1000 for 4 h (other panels) and immunogold labeled with anti-Hla primary antibodies and secondary antibodies tagged with 15 nm gold particles. The left panels were photographed using the InLens detector and the right panels were photographed using the HE-SE2 detector to highlight the gold labeling. The inset shows a magnified view of the area inside the magenta box. Scale bars represent 0.2 μm

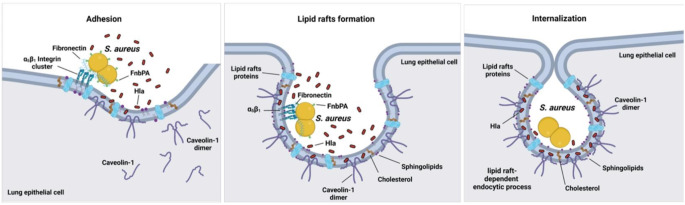

A schematic representation of the interactions between Hla, lipid rafts, and caveolin-1 that facilitate S. aureus internalization into lung epithelial cells is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed model for S. aureus internalization into human lung epithelial cells via Hla interaction with caveolin-1 on lipid rafts. The first step is the adhesion of S. aureus to lung epithelial cells, which involves the α5β1 integrin expressed on the epithelial cell and is mediated by bacterial fibronectin-binding protein A (FnbPA) via fibronectin as a connecting molecule (left panel). Hla released by the attached S. aureus interacts with caveolin-1 in the epithelial cell membrane, leading to membrane destabilization and formation of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich lipid rafts surrounding the bacteria (middle panel). The lipid rafts then collapse onto the plasma membrane, where they fuse and then split to form and intracellular vacuole containing S. aureus (right panel). The scheme was created using BioRender.com

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying S. aureus internalization into human lung epithelial cells. We provide evidence that S. aureus internalization within these cells is facilitated by lipid raft-mediated endocytosis. Accordingly, treatment of A549 or CI-huBroBECs cells with the lipid raft disrupting drug MβCD significantly impaired S. aureus internalization. Attachment of S. aureus to α5β1 integrin on the surface of lung epithelial cells via fibronectin bound to bacterial FnBPs was a prerequisite for bacterial internalization. However, a major finding of this study was that the interaction between bacterial Hla and caveolin-1 on the host cell appeared to be essential for the internalization process. This was supported by the observation that a mutant S. aureus strain deficient in the expression of Hla was significantly impaired in bacterial internalization despite efficient attachment to the epithelial cell surface. Similarly, inhibition of caveolin-1 functionality on lung epithelial cells resulted in a significant reduction in S. aureus internalization.

Hla is a beta-barrel pore-forming toxin that assembles into heptameric pores in the membrane of target cells [29]. This toxin is one of the major virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of S. aureus lung infections [29, 60]. The binding of Hla to target cells typically involves receptor-dependent and receptor-independent mechanisms [61]. At high concentrations (> 1 µM), Hla binds to most eukaryotic cells in a receptor-independent manner. This type of binding may occur through interactions with specific membrane lipids such as phosphocholine head groups [28]. At low concentrations (1–2 nM), Hla binds to target cells via specific receptors such as ADAM10 [57] and caveolin-1 [53–56, 62]. In this study, we found that while caveolin-1 was essential, ADAM10 was dispensable for S. aureus internalization into lung epithelial cells. There is considerable evidence for a direct interaction between S. aureus Hla and caveolin-1 in the eukaryotic cell membrane [53, 54, 56]. For example, the addition of purified caveolin-1 has been shown to inhibit Hla-induced hemolysis of rabbit erythrocytes in a dose-dependent manner [56]. Furthermore, Hla was found to co-precipitate with caveolin-1 in pull-down assays, suggesting a physical association between Hla and caveolin-1 at the molecular level [54]. This was further supported by the colocalization of Hla with caveolin-1 observed in A431 epithelial cells by confocal microscopy [54].

A major remaining question in our study is how extracellular Hla, which is secreted by S. aureus and diffusing through the extracellular milieu, can bind to caveolin-1, which is generally believed to be located on the cytoplasmic side of the cell membrane. In this regard, it has been proposed that the aromatic tip of the scaffolding domain of caveolin-1 is positioned within the membrane bilayer where it may be accessible from the extracellular environment [63]. The rest of the protein is located in the cytoplasm, with the N-terminal region functioning as a scaffolding domain that controls lipid raft-dependent endocytosis [64]. Thus, extracellular Hla could potentially interact with the exposed aromatic tip of caveolin-1 at the membrane interface, leading to subsequent internalization events. Support for this statement is provided by the high levels of Hla detected primarily in the lipid rafts surrounding S. aureus in human lung epithelial cells (Fig. 5). Interestingly, Hoffmann et al. [27] reported that, in fibroblasts, caveolin-1 acts as a lock that stabilizes the plasma membrane in the lipid rafts [27]. This implies that specific signaling events may be required to induce conformational changes or modifications in caveolin-1 that allow it to destabilize the cell membrane and initiate the lipid raft-dependent endocytic process. Based on the results of our study, we propose that the interaction between Hla and caveolin-1 leads to cell membrane destabilization in lung epithelial cells to allow S. aureus endocytosis via lipid rafts.

The use of lipid rafts and caveolin-1 to enter host cells is not unique to S. aureus but is rather a common strategy used by various pathogens from different taxa to gain access to their host cells [19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26]. This underscores the evolutionary advantage of this cell invasion strategy for pathogen survival. Pathogen entry via lipid rafts prevents fusion with lysosomes and subsequent degradation by the host antimicrobial mechanisms [24]. Indeed, we found that S. aureus was not only able to survive in the intracellular compartment of human lung epithelial cells but also remained viable and even proliferated. In addition to lung epithelial cells, S. aureus is able to invade and survive intracellularly in many other cell types [65]. This ability allows S. aureus to hide from the immune cells and persist in the host. In addition, many antibiotics are poorly penetrating into eukaryotic cells and do not reach the concentration necessary to eliminate intracellular S. aureus, leading to treatment failure and even promoting antibiotic tolerance [66]. Consequently, elimination of the intracellular S. aureus reservoir is key to treatment success. An alternative to killing intracellular S. aureus would be to interfere with its ability to internalize into host cells, for example by inactivating the bacterial virulence determinants involved in the internalization process. Since the pathway used by S. aureus for internalization may vary depending on the infected cell type, understanding the pathways and virulence factors involved in its invasion of different host cells is critical for developing effective strategies to target the intracellular bacterial reservoir. In the specific case of human lung epithelial cells, this study shows that inhibiting the interaction between bacterial Hla and host cell caveolin-1 significantly reduces the ability of S. aureus to internalize within these cells. In this regard, Hla inhibitors such as anti-Hla antibodies in combination with antimicrobial treatment, may represent a more effective strategy for successful treatment of S. aureus respiratory infections.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank S. Beyer for technical assistance.

Author contributions

OG and JCL contributed equally to this study. OG and JCL performed the experiments and analyzed the data. EM and OG designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MR performed some of the electron microscopy experiments. GM performed all confocal microscopy and most of the electron microscopy experiments and prepared the corresponding figures. TM has performed part of the experiments with the CI-huBroBECs cells. All authors have contributed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by internal funding provided by the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information file. Additionally, data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Oliver Goldmann and Julia C. Lang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Parker D, Prince A (2012) Immunopathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pulmonary infection. Semin Immunopathol 34(2):281–297 Epub 2011/11/01. 10.1007/s00281-011-0291-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RN (2010) Microbial etiologies of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 51(Suppl 1):S81–S87 Epub 2010/07/06. 10.1086/653053. PubMed PMID: 20597676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garzoni C, Francois P, Huyghe A, Couzinet S, Tapparel C, Charbonnier Y et al (2007) A global view of Staphylococcus aureus whole genome expression upon internalization in human epithelial cells. BMC Genomics 8:171 Epub 2007/06/16. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surmann K, Simon M, Hildebrandt P, Pfortner H, Michalik S, Dhople VM et al (2016) Data Brief 7:1031–1037 Epub 2016/10/21. 10.1016/j.dib.2016.03.027. Proteome data from a host-pathogen interaction study with Staphylococcus aureus and human lung epithelial cells [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Truong-Bolduc QC, Bolduc GR, Medeiros H, Vyas JM, Wang Y, Hooper DC (2015) Role of the Tet38 efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus internalization and survival in epithelial cells. Infect Immun 83(11):4362–4372 Epub 2015/09/02. 10.1128/IAI.00723-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niemann S, Nguyen MT, Eble JA, Chasan AI, Mrakovcic M, Bottcher RT et al (2021) More is not always better-the double-headed role of fibronectin in Staphylococcus aureus host cell Invasion. mBio 12(5):e0106221 Epub 2021/10/20. 10.1128/mBio.01062-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H, Xu J, Li W, Wang S, Li J, Yu J et al (2018) Staphylococcus aureus virulence attenuation and immune clearance mediated by a phage lysin-derived protein. EMBO J 37(17). 10.15252/embj.201798045PubMed PMID: 30037823; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6120661 Epub 2018/07/25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Whitsett JA, Alenghat T (2015) Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity. Nat Immunol 16(1):27–35 Epub 2014/12/19. doi: 10.1038/ni.3045. PubMed PMID: 25521682; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4318521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertuzzi M, Hayes GE, Bignell EM (2019) Microbial uptake by the respiratory epithelium: outcomes for host and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev 43(2):145–161. 10.1093/femsre/fuy045PubMed PMID: 30657899; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6435450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renard HF, Boucrot E (2021) Unconventional endocytic mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. ;71:120-9. Epub 2021/04/17. 10.1016/j.ceb.2021.03.001. PubMed PMID: 33862329 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kaksonen M, Roux A (2018) Mechanisms of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19(5):313–326 Epub 2018/02/08. 10.1038/nrm.2017.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMahon HT, Boucrot E (2011) Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12(8):517–533 Epub 2011/07/23. 10.1038/nrm3151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veiga E, Guttman JA, Bonazzi M, Boucrot E, Toledo-Arana A, Lin AE et al (2007) Invasive and adherent bacterial pathogens co-opt host clathrin for infection. Cell Host Microbe 2(5):340–351 Epub 2007/11/17. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veiga E, Cossart P (2006) The role of clathrin-dependent endocytosis in bacterial internalization. Trends Cell Biol 16(10):499–504 Epub 2006/09/12. 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellington JK, Reilly SS, Ramp WK, Smeltzer MS, Kellam JF, Hudson MC (1999) Mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus invasion of cultured osteoblasts. Microb Pathog 26(6):317–323 Epub 1999/05/27. 10.1006/mpat.1999.0272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira APA, Boucrot E (2018) Mechanisms of carrier formation during clathrin-independent endocytosis. Trends Cell Biol 28(3):188–200 Epub 2017/12/16. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levental I (2020) Lipid rafts come of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. ;21(8):420. Epub 2020/05/01. 10.1038/s41580-020-0252-x. PubMed PMID: 32350456 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Simons K, Ikonen E (1997) Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387(6633):569–572 Epub 1997/06/05. doi: 10.1038/42408. PubMed PMID: 9177342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulkarni R, Wiemer EAC, Chang W (2021) Role of lipid rafts in Pathogen-Host Interaction - A Mini Review. Front Immunol 12:815020 Epub 2022/02/08. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.815020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberger CM, Brumell JH, Finlay BB (2000) Microbial pathogenesis: lipid rafts as pathogen portals. Curr Biol. ;10(22):R823-5. Epub 2000/12/05. 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00788-0. PubMed PMID: 11102822 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hartlova A, Cerveny L, Hubalek M, Krocova Z, Stulik J (2010) Membrane rafts: a potential gateway for bacterial entry into host cells. Microbiol Immunol. ;54(4):237 – 45. Epub 2010/04/10. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00198.x. PubMed PMID: 20377752 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Manes S, del Real G, Martinez AC (2003) Pathogens: raft hijackers. Nat Rev Immunol. ;3(7):557 – 68. Epub 2003/07/24. 10.1038/nri1129. PubMed PMID: 12876558 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zaas DW, Duncan M, Rae Wright J, Abraham SN (2005) The role of lipid rafts in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections. Biochim Biophys Acta 1746(3):305–313 Epub 2005/11/18. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bukrinsky MI, Mukhamedova N, Sviridov D (2020) Lipid rafts and pathogens: the art of deception and exploitation. J Lipid Res 61(5):601–610 Epub 2019/10/17. 10.1194/jlr.TR119000391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parton RG, Richards AA (2003) Lipid rafts and caveolae as portals for endocytosis: new insights and common mechanisms. Traffic 4(11):724–738 Epub 2003/11/18. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieira FS, Correa G, Einicker-Lamas M, Coutinho-Silva R (2010) Host-cell lipid rafts: a safe door for micro-organisms? Biol Cell 102(7):391–407 Epub 2010/04/10. 10.1042/BC20090138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann C, Berking A, Agerer F, Buntru A, Neske F, Chhatwal GS et al (2010) Caveolin limits membrane microdomain mobility and integrin-mediated uptake of fibronectin-binding pathogens. J Cell Sci 123(Pt 24):4280–4291 Epub 2010/11/26. 10.1242/jcs.064006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valeva A, Hellmann N, Walev I, Strand D, Plate M, Boukhallouk F et al (2006) Evidence that clustered phosphocholine head groups serve as sites for binding and assembly of an oligomeric protein pore. J Biol Chem 281(36):26014–26021 Epub 2006/07/11. 10.1074/jbc.M601960200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berube BJ, Bubeck Wardenburg J (2013) Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin: nearly a century of intrigue. Toxins (Basel) 5(6):1140–1166 PubMed PMID: 23888516; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3717774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J (1991) Alpha-toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Rev 55(4):733–751 PubMed PMID: 1779933; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC372845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams TM, Lisanti MP (2004) The caveolin proteins. Genome Biol. ;5(3):214. Epub 2004/03/09. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-214. PubMed PMID: 15003112; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC395759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Horsburgh MJ, Aish JL, White IJ, Shaw L, Lithgow JK, Foster SJ (2002) sigmaB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J Bacteriol 184(19):5457–5467 Epub 2002/09/10. 10.1128/JB.184.19.5457-5467.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Reilly M, de Azavedo JC, Kennedy S, Foster TJ (1986) Inactivation of the alpha-haemolysin gene of Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4 by site-directed mutagenesis and studies on the expression of its haemolysins. Microb Pathog 1(2):125–138. 10.1016/0882-4010(86)90015-x. Epub 1986/04/01. PubMed PMID: 3508485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greene C, McDevitt D, Francois P, Vaudaux PE, Lew DP, Foster TJ (1995) Adhesion properties of mutants of Staphylococcus aureus defective in fibronectin-binding proteins and studies on the expression of fnb genes. Mol Microbiol. ;17(6):1143-52. Epub 1995/09/01. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061143.x. PubMed PMID: 8594333 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG et al (2006) Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367(9512):731–739 Epub 2006/03/07. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Kleist L, Stahlschmidt W, Bulut H, Gromova K, Puchkov D, Robertson MJ et al (2011) Role of the clathrin terminal domain in regulating coated pit dynamics revealed by small molecule inhibition. Cell 146(3):471–484 Epub 2011/08/06. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama SK, Yamada KM (1985) Synthetic peptides competitively inhibit both direct binding to fibroblasts and functional biological assays for the purified cell-binding domain of fibronectin. J Biol Chem 260(19):10402–10405 Epub 1985/09/05. PubMed PMID: 3161878 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilliam AJ, Smith JN, Flather D, Johnston KM, Gansmiller AM, Fishman DA et al (2016) Affinity-guided design of Caveolin-1 ligands for deoligomerization. J Med Chem 59(8):4019–4025 Epub 2016/03/25. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T et al (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9(7):676–682 Epub 2012/06/30. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinha B, Francois PP, Nusse O, Foti M, Hartford OM, Vaudaux P et al (1999) Fibronectin-binding protein acts as Staphylococcus aureus invasin via fibronectin bridging to integrin alpha5beta1. Cell Microbiol. ;1(2):101 – 17. Epub 2001/02/24. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00011.x. PubMed PMID: 11207545 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Speziale P, Pietrocola G (2020) The Multivalent Role of Fibronectin-Binding Proteins A and B (FnBPA and FnBPB) of Staphylococcus aureus in Host Infections. Front Microbiol. ;11:2054. Epub 2020/09/29. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02054. PubMed PMID: 32983039; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7480013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Fowler T, Wann ER, Joh D, Johansson S, Foster TJ, Hook M (2000) Cellular invasion by Staphylococcus aureus involves a fibronectin bridge between the bacterial fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs and host cell beta1 integrins. Eur J Cell Biol 79(10):672–679 Epub 2000/11/23. 10.1078/0171-9335-00104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Josse J, Laurent F, Diot A (2017) Staphylococcal adhesion and host cell Invasion: fibronectin-binding and other mechanisms. Front Microbiol 8:2433 Epub 2017/12/21. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Ganesh VK, Hook M (2014) Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Microbiol 12(1):49–62 Epub 2013/12/18. 10.1038/nrmicro3161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mongodin E, Bajolet O, Cutrona J, Bonnet N, Dupuit F, Puchelle E et al (2002) Fibronectin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus are involved in adherence to human airway epithelium. Infect Immun 70(2):620–630 PubMed PMID: 11796591; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC127664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vieira OV, Botelho RJ, Grinstein S (2002) Phagosome maturation: aging gracefully. Biochem J 366(Pt 3):689–704 Epub 2002/06/14. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020691. PubMed PMID: 12061891; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1222826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jarry TM, Cheung AL (2006) Staphylococcus aureus escapes more efficiently from the phagosome of a cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cell line than from its normal counterpart. Infect Immun 74(5):2568–2577 Epub 2006/04/20. 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2568-2577.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodal SK, Skretting G, Garred O, Vilhardt F, van Deurs B, Sandvig K (1999) Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 10(4):961–974 Epub 1999/04/10. 10.1091/mbc.10.4.961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merritt EA, Sarfaty S, van den Akker F, L’Hoir C, Martial JA, Hol WG (1994) Crystal structure of cholera toxin B-pentamer bound to receptor GM1 pentasaccharide. Protein Sci 3(2):166–175 Epub 1994/02/01. 10.1002/pro.5560030202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenworthy AK, Schmieder SS, Raghunathan K, Tiwari A, Wang T, Kelly CV et al (2021) Cholera Toxin as a Probe for Membrane Biology. Toxins (Basel). ;13(8). Epub 2021/08/27. 10.3390/toxins13080543. PubMed PMID: 34437414; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8402489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Quest AF, Leyton L, Parraga M (2004) Caveolins, caveolae, and lipid rafts in cellular transport, signaling, and disease. Biochem Cell Biol 82(1):129–144 Epub 2004/03/31. 10.1139/o03-071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scherer PE, Lewis RY, Volonte D, Engelman JA, Galbiati F, Couet J et al (1997) Cell-type and tissue-specific expression of caveolin-2. Caveolins 1 and 2 co-localize and form a stable hetero-oligomeric complex in vivo. J Biol Chem 272(46):29337–29346 Epub 1997/11/20. 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vijayvargia R, Suresh CG, Krishnasastry MV (2004) Functional form of Caveolin-1 is necessary for the assembly of alpha-hemolysin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 324(3):1130–1136 Epub 2004/10/16. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vijayvargia R, Kaur S, Sangha N, Sahasrabuddhe AA, Surolia I, Shouche Y et al (2004) Assembly of alpha-hemolysin on A431 cells leads to clustering of Caveolin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 324(3):1124–1129 Epub 2004/10/16. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vijayvargia R, Kaur S, Krishnasastry MV (2004) Alpha-hemolysin-induced dephosphorylation of EGF receptor of A431 cells is carried out by rPTPsigma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 325(1):344–352 Epub 2004/11/04. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pany S, Vijayvargia R, Krishnasastry MV (2004) Caveolin-1 binding motif of alpha-hemolysin: its role in stability and pore formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322(1):29–36 Epub 2004/08/18. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilke GA, Bubeck Wardenburg J (2010) Role of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 in Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(30):13473–13478 Epub 2010/07/14. 10.1073/pnas.1001815107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ludwig A, Hundhausen C, Lambert MH, Broadway N, Andrews RC, Bickett DM et al (2005) Metalloproteinase inhibitors for the disintegrin-like metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 that differentially block constitutive and phorbol ester-inducible shedding of cell surface molecules. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 8(2):161–171 Epub 2005/03/22. doi: 10.2174/1386207053258488. PubMed PMID: 15777180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schallenberger MA, Niessen S, Shao C, Fowler BJ, Romesberg FE (2012) Type I signal peptidase and protein secretion in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 194(10):2677–2686 Epub 2012/03/27. 10.1128/JB.00064-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bubeck Wardenburg J, Bae T, Otto M, Deleo FR, Schneewind O (2007) Poring over pores: alpha-hemolysin and Panton-Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Nat Med 13(12):1405–1406 Epub 2007/12/08. 10.1038/nm1207-1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hildebrand A, Pohl M, Bhakdi S (1991) Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin. Dual mechanism of binding to target cells. J Biol Chem 266(26):17195–17200 Epub 1991/09/15. PubMed PMID: 1894613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pany S, Krishnasastry MV (2007) Aromatic residues of Caveolin-1 binding motif of alpha-hemolysin are essential for membrane penetration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 363(1):197–202 Epub 2007/09/14. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fernandez I, Ying Y, Albanesi J, Anderson RG (2002) Mechanism of caveolin filament assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(17):11193–11198 Epub 2002/08/09. 10.1073/pnas.172196599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu P, Rudick M, Anderson RG (2002) Multiple functions of caveolin-1. J Biol Chem 277(44):41295–41298 Epub 2002/08/22. 10.1074/jbc.R200020200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fraunholz M, Sinha B (2012) Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus: live-in and let die. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:43 Epub 2012/08/25. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hommes JW, Surewaard BGJ (2022) Intracellular Habitation of Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Mechanisms and Prospects for Antimicrobial Therapy. Biomedicines. ;10(8). Epub 2022/08/27. 10.3390/biomedicines10081804. PubMed PMID: 36009351; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9405036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Surmann K, Simon M, Hildebrandt P, Pfortner H, Michalik S, Dhople VM et al (2016) Data Brief 7:1031–1037 Epub 2016/10/21. 10.1016/j.dib.2016.03.027. Proteome data from a host-pathogen interaction study with Staphylococcus aureus and human lung epithelial cells [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information file. Additionally, data are available from the corresponding author upon request.