Abstract

This study evaluated whether bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) combined with xenogeneic acellular nerve grafts (xANGs) would reduce the inflammation reaction of xANGs transplantation. BM-MSCs were extracted, separated, purified, and cultured from the bone marrow of rats. Then BM-MSCs were seeded into 5 mm xANGs as experimental group, while xANGs group was chosen as control. Subcutaneous implantation and nerve grafts transplantation were done in this study. Walking-track tests, electrophysiological tests, H&E staining, and immunostaining of CD4, CD8, and CD68 of subcutaneous implantations, cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α in lymphocytes supernatants and serum of the two groups were evaluated. Walking-track tests and electrophysiological tests suggested the group of BM-MSCs with xANGs obtained better results than xANGs group (P < 0.05). H&E staining and immunostaining of CD4, CD8, and CD68 of subcutaneous implantations showed there were less inflammatory cells in the group of BM-MSCs when compared with the xANGs group. The cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in BM-MSCs group were lower than xANGs group in lymphocytes supernatants and serum (P < 0.05). However, IL-10 concentrations in BM-MSCs group were higher than xANGs group (P < 0.05). xANG with BM-MSCs showed better nerve repair function when compared with xANG group. Furthermore, xANG with BM-MSCs showed less inflammatory reaction which might indicate the reason of its better nerve regeneration.

Keywords: Immunoregulation, Xenogeneic acellular nerve graft, Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, Transplant

Introduction

Patients suffer from peripheral nerve defects might have impaired life quality in many cases (Noble et al. 1998). In the last few years, with the development of tissue engineering, acellular nerve graft (ANG), especially xenogeneic acellular nerve graft (xANG), has become a good candidate for nerve repair (He et al. 2012; Nagao et al. 2011). Nowadays, there are a large number of different procedures to decellularize xenogeneic nerve, but most of them could not decellularize completely (Hudson et al. 2004). Moreover, although xANG would retain internal structure and extracellular matrix (ECM) components of the nerve which are suitable for nerve regeneration, it is still a complex foreign biomaterial which commonly contains type I collagen, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and adhesion molecules (Badylak et al. 2009). Even if cellular parts could be removed completely, all the residual components of xANG would cause inflammatory damage to the host (Badylak et al. 2009; Allman et al. 2001).

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells are multipotent progenitors (Pittenger et al. 1999; Dominici et al. 2006; Friedens et al. 1974). Interestingly, BM-MSCs have gotten renewed interest in the last few years, particularly due to their ability to modulate the immune response (Chen et al. 2006). Studies showed that in particular circumstances, BM-MSCs would elicit high levels of immunosuppressive factors which could inhibit immune cell activity and lead to immunosuppression (Ma et al. 2014). This feature, together with the characters that they are not immunogenic and are home to damaged tissue preferentially, makes them good candidates for cell-based therapy for a wide range of autoimmune disorders (Dazzi and Krampera 2011; Krampera 2011).

Based on the previous studies, considering the potential immunological rejection caused by xANG and the immunoregulation effects of BM-MSCs, we planned to study the immunoregulation effects of BM-MSCs combining with xANGs and the mechanism involved in after transplantation in a rat model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats and York pigs from laboratory animal research center of Xi’an Jiaotong University were used in the study. All experiment animals were housed under standard conditions, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of the Xi’an Jiaotong University. All surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia with intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium.

Preparation of Xenogeneic Acellular Nerve Grafts

Bilateral intercostal nerves of anesthetized York pigs were exposed and the nerve segments were excised to prepare xANGs under aseptic condition. After that, the connective tissue of the nerves was removed under the light microscope, and then the nerves were immediately placed in sterilized distilled water and cut into 5-mm segments. Xenogeneic acellular nerves were prepared from these segments under optimized chemical processing, and all the subsequent steps were conducted based on the previously developed protocol (Hudson et al. 2004). Briefly, nerve tissues were immersed in trypsin for digestion, and then rinsed in deionized distilled water. After 7 h, the water was aspirated and replaced with a 10 mM phosphate-buffered 50 mM sodium solution containing 125 mM SB-10 (sulfobetaine-10), and the nerves were agitated for 15 h. The tissue was then rinsed once for 15 min in a 50 mM phosphate-buffered 100 mM sodium solution. Next, the washing buffer was replaced with a 10 mM phosphate-buffered 50 mM sodium solution containing 0.6 mM SB-16 (sulfobetaine-16), and 0.14 % Triton X-200. After agitating for 24 h, the tissue was rinsed with the washing buffer three times at 5 min per rinse. The nerve segments were again agitated in the SB-10 solution (7 h), washed once, and agitated in the SB-16/Triton X-200 solution (15 h). Finally, the tissue segments were washed three times for 15 min in a 10 mM phosphate-buffered 50 mM sodium solution and then stored in the same solution at 4 °C.

BM-MSCs Preparation

About 6- to 8-week-old SD rats were killed using sodium pentobarbital, and the long bones were collected under sterile conditions, then all the bones were cut at both ends. The bone marrow from each bone was collected by flushing the bone with α Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (αMEM) (Sigma, US) containing 1,000 U/ml Penicillin G (Sigma, US). After filtering, the cells were centrifuged at 1,000×g for 5 min. The purified cells were finally dispersed in αMEM with 15 % fetal bovine serum (Sigma, US) containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, US) (Nadri et al. 2007). The medium was changed on the fourth day of culture and every 3 days after that. When the cells became subconfluent, usually after 7–10 days of culture, cells were detached using trypsin/EDTA (0.25 % trypsin and 0.02 % EDTA) (Sigma, US), concentrated by centrifugation at 1,000×g for 5 min and then suspended in medium. An analysis of cell surface molecules, CD44 and CD34, was conducted using flow cytometry. Osteoblasts and adipocytes differentiation was detected with alkaline phosphatase and Oil Red O staining kits under different induction conditions.

Construction of Nerve Grafts In Vitro

BM-MSCs were utilized for allogenic seeding. Single-cell suspension containing 2 % gelatin was prepared at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml, and the xenogeneic acellular nerves were pre-incubated in complete medium at 37 °C for 3 h. A total volume of 30 μl cell suspension was injected into a nerve graft using a microinjector, resulting in a loading of 3 × 105 cells per graft. To perform the injection, under a dissecting microscope, the microinjector was inserted through the full length of nerve segments, and the cells were injected in equal volumes at four evenly spaced points as the injector was withdrawn. The nerve grafts implanted with BM-MSCs were then immersed in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 under fully humidified condition. After 3 days culture, some nerve scaffolds embedded with BM-MSCs were utilized to bridge nerve defects in vivo. xANGs were also treated via the former procedure as control, without BM-MSCs involving.

Subcutaneous Implantation

30 SD rats were divided into two groups randomly (n = 15 per group). The groups were assigned as follows: (A) BM-MSCs-xANG group (BM-MSCs group), (B) xANG alone (xANG group). The rats were anesthetized by sodium pentobarbital, and the surgical site was shaved and sterilized by 75 % ethanol 3 times. A skin incision was then made along the dorsal midline. After that, 5-mm sterile segments of BM-MSCs-xANG or xANGs were placed in dorsal midline subcutaneous pocked, and sutured the skin with 6–0 proline sutures, and the wounds of the rats were rinsed with 40,000 U gentamycin sulfate. After surgery, the rats were placed under a warm light, allowed to recover from anesthesia, and then housed separately with food and water ad libitum in a colony room maintained at constant temperature (19–22 °C) and humidity (40–50 %) on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle.

Nerve Grafts Transplantation

All the other SD rats were divided into BM-MSCs and xANG groups randomly (n = 15 per group). The rats were anesthetized by sodium pentobarbital, and the surgical site was shaved and sterilized by 75 % ethanol 3 times. A skin incision was then made along the femoral axis, the thigh muscles were separated free. After that, the right sciatic nerves were cut near the obturator tendon in mid-thigh, allowed to retract, and then the distal nerve stumps were transected again to create 5 mm nerve defects. Both stumps of sciatic nerves gap were bridged using BM-MSCs-xANG or xANG with 10–0 nylon monofilament. The wounds of the rats were rinsed with 40,000 U gentamycin sulfate. After that, the muscles were reapposed with 4–0 vicryl sutures, and the skin incision was clamped shut with wound clips. After operation, the rats were placed under the same environment as subcutaneous implantation rats which mentioned before.

Walking-Track Tests

The rat sciatic function index (SFI) score was evaluated as previously described (Baptista et al. 2007; Bozkurt et al. 2008; Mimura et al. 2004) to measure the functional recovery of the rats from two groups. At different time points (2, 4, 8, and 12 week), the hind feet of the rats was dipped in ink, and the rats were allowed to walk across a plastic tunnel so that the footprints could be recorded on paper loaded onto the bottom of the tunnel. The distance between the top of the third toe and the most posterior part of the foot in contact with the ground (print length, PL), the distance between the first and the fifth toes (toe spread, TS), and the distance between the second and fourth toes (ITS) were measured on the experimental side (EPL, ETS, and EITS, respectively) and on the contralateral normal side (NPL, NTS, and NITS, respectively). The SFI was generated as follows: SFI = 109.5 × (ETS − NTS)/NTS − 38.3 × (EPL − NPL)/NPL + 13.3 × (EITS − NITS)/NITS − 8.8. In general, a SFI value around 0 indicated normal nerve function and a value around −100 indicated total dysfunction.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological tests were performed 12 weeks later after the transplantation. Under anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital, the previous surgical site was re-opened and the sciatic nerve was re-exposed. Bipolar hooked platinum recording and stimulating electrodes were used to induce and record electrical activity. Electrical stimuli were applied with the intensity of 1–30 mA to ensure the maximum waveform and prevent independent muscle contraction, and also applied to the sciatic nerve trunk at the proximal and distal ends of the graft sequentially. Recordings of compound muscle action potential amplitude as well as nerve conduction velocity were recorded following a supramaximal stimulus delivered by the proximal electrodes. Procedures were performed on a heating blanket to maintain temperature of 37 °C. The evoked peak amplitude of compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and the nerve conduction velocity in responding to the stimuli was recorded using MedLab V6.0 system (Meiyikeji, China). The stimuli duration was 0.2 ms, and stimulation frequency was 1 Hz.

Subcutaneous Implantation Evaluated by Histological Analysis

At 7, 14, 21 days post-surgery, the implanted grafts were taken out, and were immediately fixed with 4 % phosphate-buffered formalin over night at 4 °C. After that, the grafts were embedded in paraffin. Then, 5-mm sections were transected on a cryotome and collected on coated slides. Longitudinal sections of specimen, 7-μm thick, were cut with a microtome and captured on glass slides. Some sections were prepared for histopathological analysis using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Meanwhile, immunohistochemistry was used to inspect these two kinds of grafts for signs of immunological rejection. Immunostaining was performed with anti-rat CD4 (ABcam, UK), CD8 (ABcam, UK), and CD68 (ABcam, UK) as primary antibodies. Then, the sections were incubated in horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled second Abs (Sigma, US) for 30 min in a 37 °C chamber, rinsed 3 times in PBS, and incubated in 4 % diaminobenzidine substrate solution at room temperature. The stained slides were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70). Images were acquired using an optics-microscopy connected CCD camera (DP25, Olympus, Japan).

Analysis of Lymphocyte Cytokine Secretion In Vitro

At 21 days post-surgery, spleen was taken out from SD rats of different groups which had been anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital. Lymphocytes were selected with 2,000 g centrifugation after spleen was digested for 2 h with 625 U/ml collagenase (Sigma, US). Cells were then suspended again with 2 ml RPMI 1640 containing 10 % fetal bovine serum in 24-well plates. Following incubating 3 days at 5 % CO2 and 37 °C, lymphocytes were centrifuged at 2,000×g for 5 min, and supernatants were analyzed using a rat Th1/Th2 ELISA kit (IL-2, IL-10 and interferon gamma (IFN-γ), eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At the same time, a rat tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) ELISA kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was used to measure the concentrations of TNF-α in supernatants according to the manufacturer’s instructions as well.

Cytokine Profile in Peripheral Blood

At 21 days post-surgery, we tested IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γconcentrations in sera from blood of two groups, also using the same rat Th1/Th2 ELISA kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and TNF-α ELISA kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Analysis was performed using the SPSS 13.0 software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test was used for the comparison among experimental groups. Non-parametric data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test among experimental groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

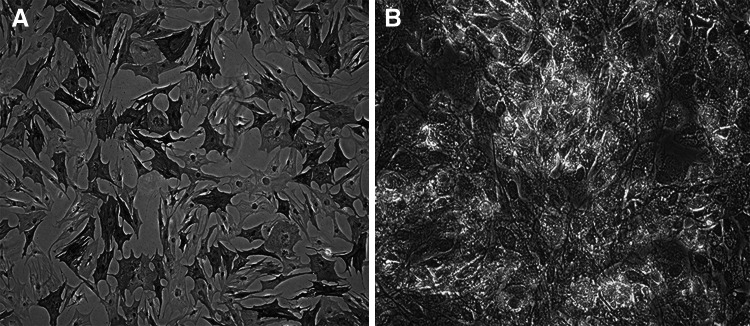

Characterization of Rat BM-MSCs

CD44 and CD34 were chosen as markers of flow cytometry. BM-MSCs were successfully expanded 3–4 days after initial seeding, and rapidly expanded into colonies of confluent spindle cells at 10–14 days. The third-passage cells were incubated with antibodies of both CD44 and CD34. Results showed that the cells were positive to CD44 (98.87 %) and negative to CD34 (1.13 %). The changes of osteoblasts and adipocytes differentiation were visualized 10 days after alkaline phosphatase staining and Oil Red O staining (Fig. 1a, b). According to the minimal criteria represented by the Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy (Dominici et al. 2006), the cultured cells were effectively BM-MSCs.

Fig. 1.

Osteoblasts differentiation was monitored by alkaline phosphatase staining (a). Adipocytes differentiation was monitored by Oil Red O staining (b)

Evaluation of the Nerve Transplantation

Twelve weeks after nerve grafts transplantation, all nerve grafts were integrated into the host nerve successfully. Proximal and distal ends of all nerve grafts remained coated to the proximal and distal stump of the transected nerve in all rats. At the ultimate time point, all nerve grafts were observed to be glossy white and opaque, with little evidence of disruptions. In addition, no evidence of neuroma formation was observed at either the graft-host junction or graft elongation in both groups.

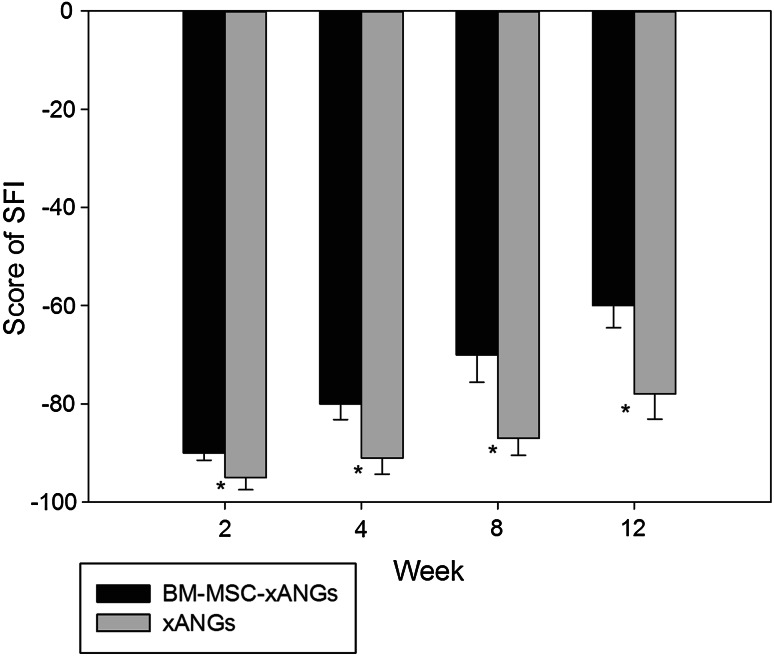

The efficacy of two kinds of nerve grafts on motor functional improvement in peripheral nerve injured rats was evaluated based on SFI. The results showed that SFI values were increased significantly in BM-MSCs group compared with xANG group at each time point (P < 0.05). These results indicated that the combination of BM-MSCs was more effective to promote motor function recovery than xANG only (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Typical walking tracks were obtained from two experimental groups at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after surgery, and SFI value was calculated. Data were shown in mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 versus xANGs group

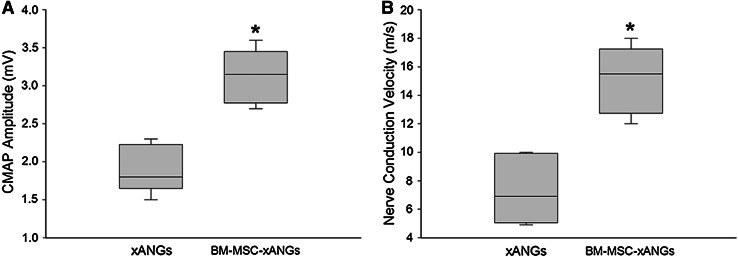

Electrophysiological studies were used to determine whether functional nerve regeneration occurred after transplantation of these two kinds of nerve grafts. After 12 weeks, the BM-MSCs group significantly presented superior recovery of electrophysiological parameters of regeneration compared with xANGs group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Amplitude of the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) was significantly greater in BM-MSCs group than xANGs group (a). Result of nerve conduction velocity recording (b) was similar to CMAP analysis. Data were shown in mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 compared with xANGs group

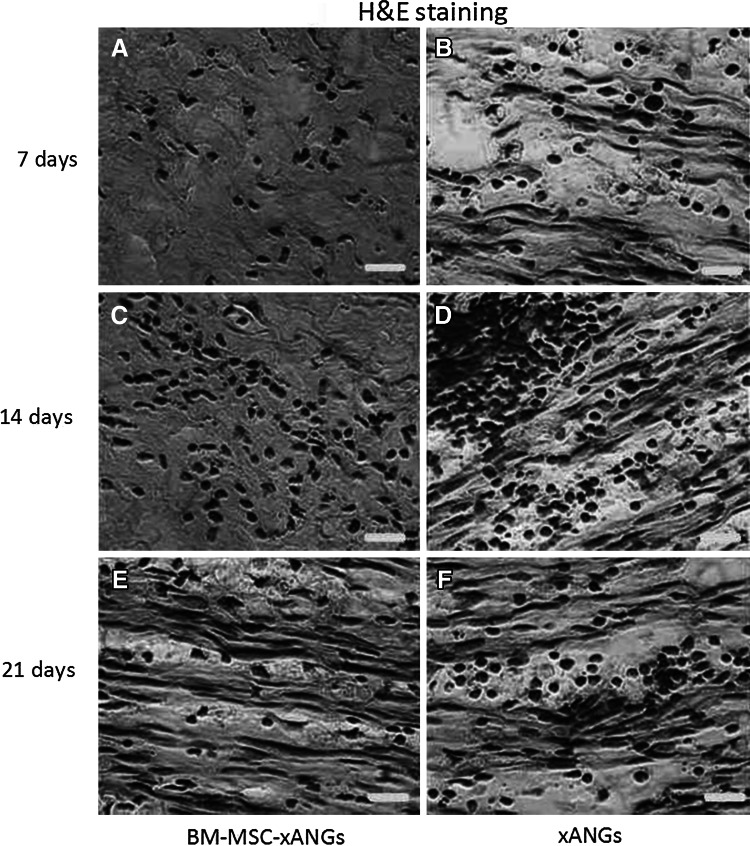

Histological Analysis of Subcutaneous Implantation

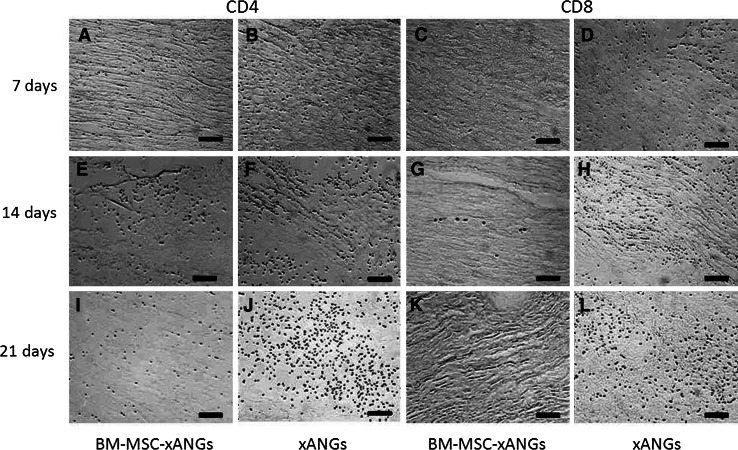

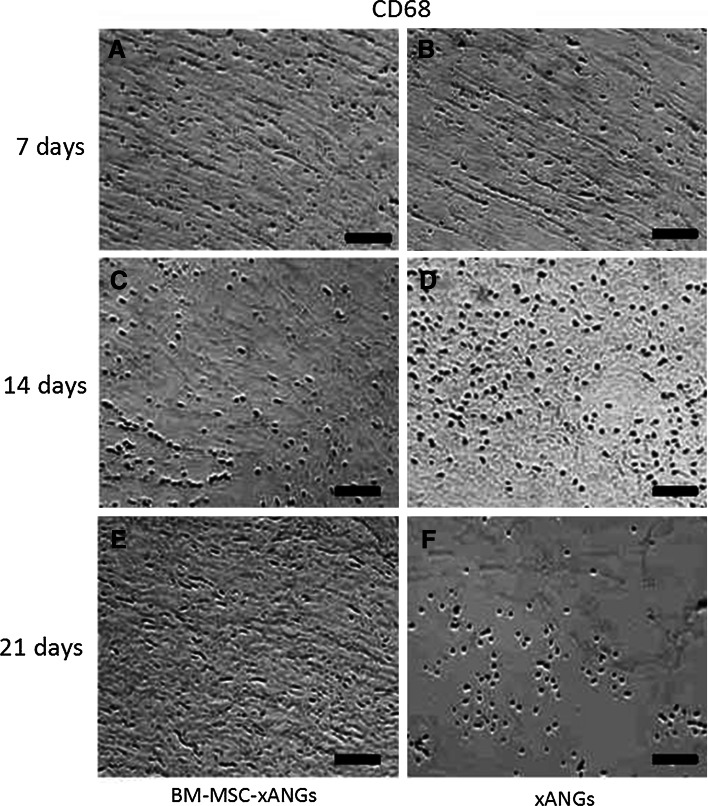

Two kinds of xANGs were implanted into SD rat subcutaneous to observe host response. At day 7, 14, and 21 post-surgery, grafts were taken out for H&E staining and immunohistochemical analysis. At day 7, implantation caused inflammatory reaction consisting mostly of lymphocytes infiltration, but BM-MSCs group showed less lymphocytes than xANGs group (Fig. 4a, b). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed some CD4+ T cells appeared in the host tissue, and the number of CD4+ T cells in BM-MSCs group was less than the other group (Fig. 5a, b). CD68, which is mark of macrophage, was also positive staining in both groups and the number of CD68+ cells in BM-MSCs group was less than another group (Fig. 6a, b). At day 14, the inflammation caused by lymphocytes was increased and BM-MSCs group showed less lymphocytes when compared with the xANGs group (Fig. 4c, d). Compared with Day 7, the quantity of CD4+ T cells was increased at the site of host tissue in xANGs group, and the number of CD4+ T cells in BM-MSCs group was also increased but it was still less than the other group (Fig. 5e, f), while CD68+ cells in both groups showed the same trend as well (Fig. 6c, d). 21 days later, lymphocytes decreased in both groups and BM-MSCs group still showed less lymphocytes (Fig. 4e, f). Meanwhile, the quantity of CD4+ T cells was decreased at the site of host tissue in BM-MSCs group (Fig. 5i). Nevertheless, in the xANGs group, the number of CD4+ T cells did not decrease (Fig. 5j). In xANGs group, the number of CD8+ T cells showed the same trend as CD4+ T cells, but CD8+ T cells in BM-MSCs group could be barely discovered (Fig. 5c, d, g, h, k, l). At the same time, the quantity of CD68+ cells in both groups was decreased at day 21 though the number of CD68+ cells in BM-MSCs group was still less than xANGs group (Fig. 6e, f).

Fig. 4.

H&E staining after xANG implantation 7, 14, and 21 days, implantation caused inflammatory reaction consisting mostly of lymphocytes infiltration, and BM-MSCs group showed less lymphocytes than xANGs group in every time point (a–f). And the number was most abundant at 14 days (c, d) and at day 21 the number was decreasing (e, f). Scale bars represent 50 μm

Fig. 5.

CD4 immunostaining represented positive signal after xANG implantation 7, 14, and 21 days, and BM-MSCs-xANGs group showed less CD4+ T cells than xANGs group in every time point (a, b, e, f, i, j), and the number was most abundant at 14 days (e), at day 21 the number was decreasing (i) in BM-MSCs group. However, in the xANGs group, the number of CD4+ T cells did not decrease on day 21 when compared with day 14 (f, j). CD8 immunostaining represented barely positive signal in BM-MSCs group (c, g, k), but the number of CD8+ T cells showed the same trend as CD4+ T cells in xANGs group. Scale bars represent 100 μm

Fig. 6.

CD68 immunostaining represented positive signal after xANG implantation 7, 14, and 21 days, and BM-MSCs-xANGs group showed less CD68+ cells than xANGs group in every time point (a–f), and the number was most abundant at 14 days (c, d), at day 21 the number was decreasing (e, f) in both groups. Scale bars represent 100 μm

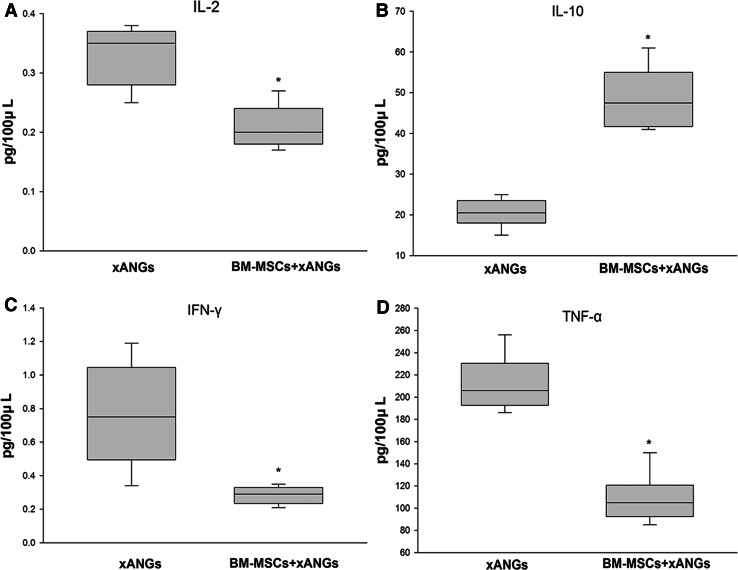

Analysis of Lymphocyte Cytokine Concentrations

We assessed the cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-αin supernatants of lymphocytes which separated from spleen at 21 days post-surgery. As we observed, BM-MSCs tended to decrease cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α significantly (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7a, c, d). On the contrary, the concentrations of IL-10 from BM-MSCs group showed significantly higher level than xANGs group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

The cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in supernatants of lymphocytes which separated from spleen at 21 days post-surgery, the IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α concentrations in BM-MSCs group were significantly lower than xANGs group (a, c, d) (P < 0.05). The concentrations of IL-10 from BM-MSCs group showed significantly higher level than xANGs group (b) (P < 0.05). Data were shown in mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 compared with xANGs group

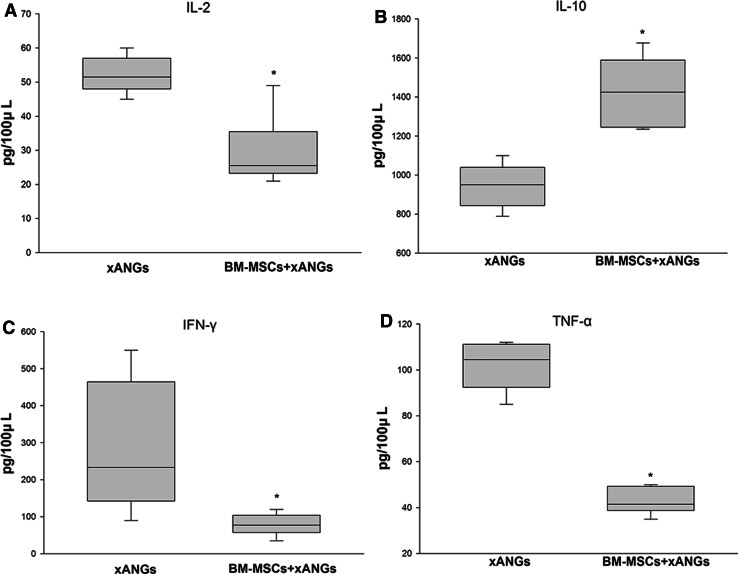

Cytokine Profile Analysis in Peripheral Blood

Parallel with cytokine concentration analysis, we also assessed serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α at 21 days post-surgery. As a result, we found that BM-MSCs decreased cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α significantly (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8a, c, d). However, it showed that BM-MSCs increased the cytokine concentrations of IL-10 significantly (P < 0.05) when compared with xANGs group (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

The cytokine analysis of IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in peripheral blood at 21 days post-operation, the IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α concentrations in BM-MSCs group were significantly lower than xANGs group (a, c, d) (P < 0.05). The concentrations of IL-10 from BM-MSCs group showed significantly higher level than xANGs group (b) (P < 0.05). Data were shown in mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 compared with xANGs group

Discussion

Peripheral nerve injury causes loss of nerve functions which would lead to impaired quality of life (Rosberg et al. 2005; Navarro et al. 2007). With the development of regenerative medicine, ANGs, especially xANGs which could be easily commercialized and acquired from other species, become a typical representative in tissue engineering for nerve repair. However, most of the procedures for nerve decellularization at present could not decellularize completely (Hudson et al. 2004). All the constituents of xANG would cause immune response to the host even without cellular parts (Allman et al. 2001; Bayrak et al. 2010). Meanwhile, previous studies revealed that implantation of BM-MSCs combining with xANGs could enhance sciatic nerve regeneration (He et al. 2012; Nagao et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2007; Kubek et al. 2011). Additionally, due to their ability to regulate the immune reaction, BM-MSCs have been re-understood in the last several years (Chen et al. 2006). Researches showed BM-MSCs would draw high levels of immunosuppressive factors like interleukin-10 (IL-10) which could reduce immune cell activity and lead to potent immunosuppression (Ma et al. 2014). Further, the crosstalk between BM-MSCs and the cells of the immune system leads to an increased or decreased production of several soluble immunomodulatory factors (English et al. 2007; Kang et al. 2008).

Based on the former studies, this work studied the immunoregulation effects of BM-MSCs combining with xANGs and the mechanism involved in after transplantation.

In this study, we made xenogeneic acellular nerve through trypsin, deionized distilled water and chemicals (Triton X-200, sulfobetaine-16 and sulfobetaine-10), the three key procedures, which were conducted based on the previously developed protocol (Hudson et al. 2004). This protocol removed cellular material from nerve tissue while preserving the natural ECM structure. However, as we mentioned before, ideal ANG is still a complex ECM biomaterial which commonly contain type I collagen, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and adhesion molecular, such as heparin, chondroitin sulfate, hyaluronic acid, fibronectin, and laminin (Badylak et al. 2009), which might induce immunological rejection. In addition, studies of implanted porcine-derived biological acellular materials leading to host cellular and humoral inflammatory in a primate model were described recently (Xu et al. 2008; Sandor et al. 2008).

This study showed the strong plasticity of BM-MSCs by their differentiation into osteoblasts and adipocytes. Meantime, we injected BM-MSCs into the ANGs in equal cell suspension volumes at four evenly spaced locations which could reduce the mechanical stress on injected cells and obtain better cell survivals after injection (Jesuraj et al. 2011). Earlier study has demonstrated that the injected cells would be well arranged along the longitudinal xANGs (Wang et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2010). Besides, Hu et al. (2007) observed that implanted BM-MSCs survived and migrated inside the acellular nerve graft up to 3 days. Further, Wang et al. (2008) demonstrated that BM-MSCs within the nerve grafts survived and some could differentiate into Schwann-like cells after 8 weeks inside acellular nerve transplants in vivo.

In this study, we chose SFI as a proper parameter to evaluate the functional recovery (Kanaya et al. 1996). The SFI from the group of nerve repair with the BM-MSCs with xANG was significantly improved when compared with the nerve repair with xANG only. In our work, we also chose the classical nerve electrophysiological function test for evaluating nerve recovering. Better nerve regeneration and axonal myelination would reflex in higher amplitude and nerve velocity. We found that the amplitude of CMAP and nerve conduction velocity of BM-MSCs group showed significantly higher results in electrophysiological function when compared with the other group. These results showed that BM-MSCs would improve the nerve repair.

Our study shows that BM-MSCs group presented less inflammation cells (lymphocytes mainly) than xANGs group in every time point from H&E staining, and the number of inflammation cells was most abundant at 14 day in both groups. For further study, we carried on the immunohistochemical analysis of CD4 and CD8. In the xANGs group, in each time point, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were more than BM-MSCs group. Moreover, the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not decrease on day 21 when compared with day xANGs group. On the contrary, in the BM-MSCs group, we found the same variation trend as H&E staining in CD4+ T cell quantity over time and rare CD8+ T cells which indicated the possible suppression of immune response. Nowadays, MSC-mediated inhibition of T cell proliferation has been largely described. In vitro, MSCs can inhibit CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation regardless of the signaling pathway stimulated in the lymphocytes (Le Blanc et al. 2003). Further, upon coculture, MSCs can induce a G0/G1 checkpoint arrest in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Di Nicola et al. 2002; Glennie et al. 2005). The feature of BM-MSCs to suppress the proliferation of T cells has opened new viewpoints for their clinical application (Luz-Crawford et al. 2013). On the other hand, macrophages, as innate immune cells, can be activated in response to tissue damage or infection during process of transplantation surgery (Anderson et al. 2008). Further, Kim and Hematti (2009) described a novel type of macrophage generated in vitro after coculture with BM-MSCs that assume an immunophenotype defined as IL-10 high and TNF-α low secreting cells . These MSC-educated macrophages may be a unique and novel type of alternatively activated macrophages with potentially significant role in tissue repair and immunosuppressive effect. In this study, we also performed the immunohistochemical analysis of CD68, a marker of macrophage, to evaluate xenogeneic immune response (Pulford et al. 1990). Lower number of macrophages in BM-MSCs group in every time point and the changes of quantities over time in both groups are consistent with our H&E staining analyses performed in this work, indicating the possible superior immunosuppressive effect of BM-MSCs.

Furthermore, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as macrophages affect immune reaction through the interaction of several secreted effector molecules, such as IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-10. Meanwhile, Aggarwal et al. demonstrate that MSCs interact with isolated cells of the immune system, and MSCs are capable of altering the outcome of the immune cell response by inhibiting two of the most important proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IFN-γ) and by increasing expression of suppressive cytokines, including IL-10 (Aggarwal and Pittenger 2005). The balance between proinflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory cytokines is critical to immunoregulation effects. Therefore, in this work, we also tested the cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-10 in lymphocytes supernatants and serum for further study.

As we know, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α are inflammatory accelerators (Polchert et al. 2008; Nagler et al. 2010; English et al. 2007; Prasanna et al. 2010) which are responsible for immunity and inflammation. They can enhance immune response and rejection alone or synergetically. IL-2 is necessary for adaptive immunity to foreign pathogens, as it is the basis for the development of immunological memory (Cantrell and Smith 1984). Many of the immunosuppressive drugs, such as corticosteroids and cyclosporine, work by inhibiting the production of IL-2 (Sakaguchi et al. 1995). Meanwhile, abnormal IFN-γ expression is associated with a lot of autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Due to the effect of immune activation, aberrant IFN-γ secretion would lead to severe rejection after transplantation (Zibar et al. 2011; Rendina et al. 2011; Briesemeister et al. 2011). Meantime, TNF-α is able to induce inflammation, and some studies showed that TNF-α, as a proinflammatory cytokine, contributed to the mechanism of transplant rejection (Mandegary et al. 2013; de Menezes Neves et al. 2013; Wang and Al-Lamki 2013). In our work, it indicated that BM-MSCs would reduce the secretion of these three inflammatory accelerators and lead to less inflammatory reaction and rejection.

On the contrary, IL-10 has a wide range of biological activities, including immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties, which regulate a variety of immune cell differentiation and proliferation events (Moore et al. 2001). IL-10 can down-regulate the major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) and growth and differentiation of B cells, T cells, dendritic cells, and other cells involved in inflammatory responses. Chernoff et al. (1995) also demonstrated that the inflammatory cytokine production and immune responses were inhibited after injection of IL-10 in humans. In our study, significantly higher level of IL-10 concentration in BM-MSCs when compared with xANGs group indicated that in the presence of BM-MSCs, the host was probably in the state of immunosuppression which would reduce the inflammatory reaction and rejection through promoting negative inflammatory regulatory factors way.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study validated that the combination of xANG with BM-MSCs would significantly facilitate nerve regeneration when compared with xANG group in rat. Moreover, H&E staining and immunostaining of CD4, CD8, and CD68 showed there were less inflammatory cells in BM-MSCs group. And the proinflammatory cytokine concentrations of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in BM-MSCs group were significantly lower in lymphocytes supernatants and serum while the concentrations of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were opposite. Therefore, we proved that xANG with BM-MSCs showed less inflammatory reaction when compared with xANG group. Probably, in some degree, due to this immunoregulation effect for reducing immunologic rejection, BM-MSCs group would obtain better nerve repair. Further investigation is needed to study mechanisms and determine the condition to optimize this technique to make a contribution to regenerative medicine and autoimmune disorders treatment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81101363 and 81371944) for financially supporting this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF (2005) Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood 105(4):1815–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman AJ, McPherson TB, Badylak SF, Merrill LC, Kallakury B, Sheehan C, Raeder RH, Metzger DW (2001) Xenogeneic extracellular matrix grafts elicit a Th2-restricted immune response. Transplantation 71(11):1631–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT (2008) Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol 20(2):86–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badylak SF, Freytes DO, Gilbert TW (2009) Extracellular matrix as a biological scaffold material: structure and function. Acta Biomater 5(1):1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista AF, de Souza Gomes JR, Oliveira JT, Garzedim Santos SM, Vannier-Santos MA, Blanco Martinez AM (2007) A new approach to assess function after sciatic nerve lesion in the mouse—adaptation of the sciatic static index. J Neurosci Methods 161(2):259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak A, Tyralla M, Ladhoff J, Schleicher M, Stock UA, Volk H-D, Seifert M (2010) Human immune responses to porcine xenogeneic matrices and their extracellular matrix constituents in vitro. Biomaterials 31(14):3793–3803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A, Tholl S, Wehner S, Tank J, Cortese M, Dm O’Dey, Deumens R, Lassner F, Schuegner F, Groeger A, Smeets R, Brook G, Pallua N (2008) Evaluation of functional nerve recovery with Visual-SSI—A novel computerized approach for the assessment of the static sciatic index (SSI). J Neurosci Methods 170(1):117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briesemeister D, Sommermeyer D, Loddenkemper C, Loew R, Uckert W, Blankenstein T, Kammertoens T (2011) Tumor rejection by local interferon gamma induction in established tumors is associated with blood vessel destruction and necrosis. Int J Cancer 128(2):371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell DA, Smith KA (1984) The interleukin-2 T-cell system—a new cell-growth model. Science 224(4655):1312–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Armstrong MA, Li G (2006) Mesenchymal stem cells in immunoregulation. Immunol Cell Biol 84(5):413–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-J, Ou Y-C, Liao S-L, Chen W-Y, Chen S-Y, Wu C-W, Wang C-C, Wang W-Y, Huang Y-S, Hsu S-H (2007) Transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells for peripheral nerve repair. Exp Neurol 204(1):443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff AE, Granowitz EV, Shapiro L, Vannier E, Lonnemann G, Angel JB, Kennedy JS, Rabson AR, Wolff SM, Dinarello CA (1995) A randomized, controlled trial of IL-10 in humans—inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production and immune-responses. J Immunol 154(10):5492–5499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi F, Krampera M (2011) Mesenchymal stem cells and autoimmune diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 24(1):49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes Neves PDM, Machado JR, dos Reis MA, Faleiros ACG, de Lima Pereira SA, Rodrigues DBR (2013) Distinct expression of interleukin 17, tumor necrosis factor alpha, transforming growth factor beta, and forkhead box P3 in acute rejection after kidney transplantation. Ann Diagn Pathol 17(1):75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, Grisanti S, Gianni AM (2002) Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood 99(10):3838–3843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, Krause DS, Deans RJ, Keating A, Prockop DJ, Horwitz EM (2006) Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 8(4):315–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English K, Barry FP, Field-Corbett CP, Mahon BP (2007) IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha differentially regulate immunomodulation by murine mesenchymal stem cells. Immunol Lett 110(2):91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedens AJ, Deriglas UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luria EA, Rudakow IA (1974) Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by invitro colony assay method. Exp Hematol 2(2):83–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennie S, Soeiro I, Dyson PJ, Lam EWF, Dazzi F (2005) Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood 105(7):2821–2827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Zhu QT, Chai YM, Ding XH, Tang JY, Gu LQ, Xiang JP, Yang YX, Zhu JK, Liu XL (2012) Outcomes with the use of human acellular nerve graft for repair of digital nerve defects: a prospective, multicenter, controlled clinical trial. J Tissue Eng Reg Med 6:76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Zhu Q-T, Liu X-L, Y-b Xu, Zhu J-K (2007) Repair of extended peripheral nerve lesions in rhesus monkeys using acellular allogenic nerve grafts implanted with autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Neurol 204(2):658–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson TW, Liu SY, Schmidt CE (2004) Engineering an improved acellular nerve graft via optimized chemical processing. Tissue Eng 10(9–10):1346–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesuraj NJ, Santosa KB, Newton P, Liu Z, Hunter DA, Mackinnon SE, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Johnson PJ (2011) A systematic evaluation of Schwann cell injection into acellular cold-preserved nerve grafts. J Neurosci Methods 197(2):209–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya F, Firrell JC, Breidenbach WC (1996) Sciatic function index, nerve conduction tests, muscle contraction, and axon morphometry as indicators of regeneration. Plast Reconstr Surg 98(7):1264–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JW, Kang K-S, Koo HC, Park JR, Choi EW, Park YH (2008) Soluble factors-mediated immunomodulatory effects of canine adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 17(4):681–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Hematti P (2009) Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: a novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Exp Hematol 37(12):1445–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampera M (2011) Mesenchymal stromal cells: more than inhibitory cells. Leukemia 25(4):565–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubek T, Ghalib N, Dubovy P (2011) Endoneurial extracellular matrix influences regeneration and maturation of motor nerve axons—a model of acellular nerve graft. Neurosci Lett 496(2):75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringden O (2003) Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol 57(1):11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz-Crawford P, Kurte M, Bravo-Alegria J, Contreras R, Nova-Lamperti E, Tejedor G, Noel D, Jorgensen C, Figueroa F, Djouad F, Carrion F (2013) Mesenchymal stem cells generate a CD4(+) CD25(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell population during the differentiation process of Th1 and Th17 cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 4:65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Xie N, Li W, Yuan B, Shi Y, Wang Y (2014) Immunobiology of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ 21(2):216–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandegary A, Azmandian J, Soleymani S, Pootari M, Habibzadeh S-D, Ebadzadeh M-R, Dehghani-Firouzabadi M-H (2013) Effect of donor tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10 genotypes on delayed graft function and acute rejection in kidney transplantation. Iran J Kidney Dis 7(2):135–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura T, Dezawa M, Kanno H, Sawada H, Yamamoto I (2004) Peripheral nerve regeneration by transplantation of bone marrow stromal cell-derived Schwann cells in adult rats. J Neurosurg 101(5):806–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A (2001) Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Ann Rev Immunol 19:683–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadri S, Soleimani M, Hosseni RH, Massumi M, Atashi A, Izadpanah R (2007) An efficient method for isolation of murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Dev Biol 51(8):723–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao RJ, Lundy S, Khaing ZZ, Schmidt CE (2011) Functional characterization of optimized acellular peripheral nerve graft in a rat sciatic nerve injury model. Neurol Res 33(6):600–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagler A, Berger R, Ackerstein A, Czyz JA, Luis Diez-Martin J, Naparstek E, Or R, Gan S, Shimoni A, Slavin S (2010) A randomized controlled multicenter study comparing recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL-2) in conjunction with recombinant interferon alpha (IFN-alpha) versus no immunotherapy for patients with malignant lymphoma postautologous stem cell transplantation. J Immunother 33(3):326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro X, Vivo M, Valero-Cabre A (2007) Neural plasticity after peripheral nerve injury and regeneration. Prog Neurobiol 82(4):163–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble J, Munro CA, Prasad V, Midha R (1998) Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. J Trauma 45(1):116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR (1999) Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284(5411):143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polchert D, Sobinsky J, Douglas GW, Kidd M, Moadsiri A, Reina E, Genrich K, Mehrotra S, Setty S, Smith B, Bartholomew A (2008) IFN-gamma activation of mesenchymal stem cells for treatment and prevention of graft versus host disease. Eur J Immunol 38(6):1745–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna SJ, Gopalakrishnan D, Shankar SR, Vasandan AB (2010) Pro-inflammatory cytokines, IFN gamma and TNF alpha, influence immune properties of human bone marrow and Wharton jelly mesenchymal stem cells differentially. Plos One 5(2):e9016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulford KAF, Sipos A, Cordell JL, Stross WP, Mason DY (1990) Distribution of the CD68 macrophage myeloid associated antigen. Int Immunol 2(10):973–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina M, Castellaneta NM, Fagiuoli S, Ponziani FR, Vigano R, Iemmolo RM, Donato MF, Toniutto P, Pasulo L, Morelli MC, Burra P, Miglioresi L, Giannelli V, Di Paolo D, Di Leo A (2011) Acute and chronic rejection during interferon therapy in HCV recurrent liver transplant patients: results from the AISF-RECOLT-C group. Digest Liver Dis 43:S148–S149 [Google Scholar]

- Rosberg HE, Carlsson KS, Dahlin LB (2005) Prospective study of patients with injuries to the hand and forearm: costs, function, and general health. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 39(6):360–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M (1995) Immunological self-tolerance maintained by activated t-cells expressing il-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25)—breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune-diseases. J Immunol 155(3):1151–1164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandor M, Xu H, Connor J, Lombardi J, Harper JR, Silverman RP, McQuillan DJ (2008) Host response to implanted porcine-derived biologic materials in a primate model of abdominal wall repair. Tissue Eng Part A 14(12):2021–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Al-Lamki RS (2013) Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2: its contribution to acute cellular rejection and clear cell renal carcinoma. Biomed Res Int 2013:821310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Liu X-L, Zhu J-K, Jiang L, Hu J, Zhang Y, Yang L-M, Wang H-G, Yi J-H (2008) Bridging small-gap peripheral nerve defects using acellular nerve allograft implanted with autologous bone marrow stromal cells in primates. Brain Res 1188:44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Wan H, Sandor M, Qi S, Ervin F, Harper JR, Silverman RP, McQuillan DJ (2008) Host response to human acellular dermal matrix transplantation in a primate model of abdominal wall repair. Tissue Eng Part A 14(12):2009–2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Luo H, Zhang Z, Lu Y, Huang X, Yang L, Xu J, Yang W, Fan X, Du B, Gao P, Hu G, Jin Y (2010) A nerve graft constructed with xenogeneic acellular nerve matrix and autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 31(20):5312–5324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibar L, Wagner J, Pavlinic D, Galic J, Pasini J, Juras K, Barbic J (2011) The relationship between interferon-gamma gene polymorphism and acute kidney allograft rejection. Scand J Immunol 73(4):319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]