Abstract

Neurons of the Grueneberg ganglion (GG) residing in the vestibule of the murine nose are activated by cool ambient temperatures. Activation of thermosensory neurons is usually mediated by thermosensitive ion channels of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family. However, there is no evidence for the expression of thermo-TRPs in the GG, suggesting that GG neurons utilize distinct mechanisms for their responsiveness to cool temperatures. In search for proteins that render GG neurons responsive to coolness, we have investigated whether TREK/TRAAK channels may play a role; in heterologous expression systems, these potassium channels have been previously found to close upon exposure to coolness, leading to a membrane depolarization. The results of the present study indicate that the thermosensitive potassium channel TREK-1 is expressed in those GG neurons that are responsive to cool temperatures. Studies analyzing TREK-deficient mice revealed that coolness-evoked responses of GG neurons were clearly attenuated in these animals compared with wild-type conspecifics. These data suggest that TREK-1 channels significantly contribute to the responsiveness of GG neurons to cool temperatures, further supporting the concept that TREK channels serve as thermoreceptors in sensory cells. Moreover, the present findings provide the first evidence of how thermosensory GG neurons are activated by given temperature stimuli in the absence of thermo-TRPs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10571-013-9992-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Thermosensory, Chemosensory, Cool temperature, c-Fos, Mouse

Introduction

The Grueneberg ganglion (GG)—a small cluster of neuronal cells in the nasal vestibule of several mammalian species (Grüneberg 1973; Tachibana et al. 1990)—is activated by distinct chemical stimuli and cool temperatures (Brechbühl et al. 2008; Mamasuew et al. 2008; 2011a, b; Schmid et al. 2010). Recent studies indicate that the responsiveness of GG neurons to these modalities is mediated by unique transduction mechanisms; both the chemo- and the thermosensory pathway comprise signaling elements associated with the second messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Mamasuew et al. 2010, 2011b). However, the details of the transduction cascades and the nature of the relevant receptor proteins are yet elusive. While for the response to chemical cues distinct olfactory receptor types expressed in numerous GG neurons are considered as potentially relevant elements (Fleischer et al. 2006b, 2007), little is known about the thermosensory receptors mediating GG responses to coolness. Regarding coolness-activated sensory neurons in the trigeminal and the dorsal root ganglion of the central nervous system, the ion channel TRPM8 is considered as the principal detector element for cool temperatures (Bautista et al. 2007; Colburn et al. 2007; Dhaka et al. 2007). However, TRPM8 is absent from the GG (Fleischer et al. 2009). Previous studies suggest that besides heat- or cold-sensitive TRP channels, another family of temperature-responsive ion channels is important for thermosensation in mammals: the temperature-gated ion channels TREK-1, TREK-2 and TRAAK which belong to the two-pore domain potassium (K2P) channels (Maingret et al. 2000; Kang et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2008; Noël et al. 2009). These TREK/TRAAK channels are not only highly temperature-sensitive, they are also expressed in neurons of the trigeminal and the dorsal root ganglion (Maingret et al. 2000; Yamamoto et al. 2009), thereby affecting warm and cold perception (Noël et al. 2009). At cooler temperatures, TREK/TRAAK channels are inactivated, i.e., these potassium channels are closed (Maingret et al. 2000; Kang et al. 2005), leading to a depolarization of the cell membrane. In this context, for TREK-1, it has been reported that its activity is low at ~22 °C and reaches its climax at ~40 °C (Maingret et al. 2000); similar observations have been made for TREK-2 and TRAAK (Kang et al. 2005). Interestingly, a cool temperature of 22 °C elicits responses in GG neurons, whereas warm temperatures (such as 30 and 35 °C) do not (Mamasuew et al. 2008). Thus, this temperature response profile of the GG neurons matches quite well with the temperature-dependent gating behavior of TREK/TRAAK channels (Maingret et al. 2000; Kang et al. 2005). Therefore, in the present study, we set out to determine whether TREK/TRAAK channels might contribute to the thermosensory capacity of GG neurons.

Materials and Methods

Mice

This study was performed on mice of wild-type strain C57/BL6J purchased from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). The OMP/GFP line was kindly provided by Chen Zheng, Paul Feinstein and Peter Mombaerts. In this line, the region encoding the olfactory marker protein (OMP) was replaced by a sequence encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP). The generation of mouse strains deficient for TREK-1 or TREK-2 has been described previously (Heurteaux et al. 2004; Guyon et al. 2009). These strains were crossed to get double knockout mice (termed TREK-KO or TREK−/−). All experiments comply with the Principles of animal care, publication no. 85-23, revised 1985, of the National Institutes of Health and with the current laws of Germany.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Isolation of RNA from the GG and subsequent cDNA synthesis were carried out as described elsewhere (Fleischer et al. 2006b). For preparation of cDNA from the murine brain, total RNA was isolated with the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey–Nagel, Dueren, Germany). Mouse genomic DNA was isolated using the peqGold tissue DNA Mini Kit (Peqlab Biotechnologie, Erlangen, Germany).

Design of Oligonucleotide Primers

For amplification of sequences encoding distinct TREK/TRAAK subtypes, the following primers were used: TREK-1: 5′-ggtgatctctaagaagacgaaggaag and 5′-tcaatgacagctatgtcctcaccag; TREK-2: 5′-ctcagtatgatcggagactggctgcg and 5′-gtaccattccgttctccatctcagc; TRAAK: 5′-gcctaacggcacaggctgctagct and 5′-gccttgtctcggagtcgcccaggac. All oligonucleotide primer sequences are given according to the code of the International Union of Biochemistry (IUB code). Oligonucleotide primers were ordered from biomers.net (Ulm, Germany).

PCR

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was performed as described previously (Fleischer et al. 2006b). PCR products were cloned into pGem-T plasmids (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and subjected to sequence analysis using an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Exposure to Cool Ambient Temperatures

Female mice were kept together with their pups in a cage under a 12-h light/dark cycle (light on at 7:00 a.m.). For exposure to a given ambient temperature (22, 26, 28 or 30 °C), neonatal pups were transferred (without their mother) to a cage placed in an incubator (CERTOMAT BS-1, B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany) adjusted to the desired temperature. In these experiments, in line with previous studies (Mamasuew et al. 2008, 2010), an exposure time of 2 h was chosen since such an interval allows a substantial c-Fos expression, facilitating quantitative analyses. The pups were killed by decapitation directly after exposure.

Tissue Preparation

For in situ-hybridization, heads of mice were embedded in Leica OCT Cryocompound “tissue freezing medium” (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany) and quickly frozen on dry ice. Sections (12 μm) were cut on a CM3050S cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany) and attached to Polysine slides (Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany). For immunohistochemistry, heads of mice were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in 1xPBS (0.85 % NaCl, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, 8 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) for 15–30 min at 4 °C followed by cryoprotection in 25 % sucrose (in 1xPBS) at 4 °C overnight. Sections (12 μm) were cut on a CM3050S cryostat (Leica Microsystems) and attached to Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Menzel).

In Situ-Hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled antisense riboprobes were generated from partial cDNA clones in pGem-T plasmids encoding mouse TREK-1, TREK-2 or c-Fos using the T7/SP6 RNA transcription system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer. After fixation in 4 % paraformaldehyde/0.1 M NaHCO3/pH 9.5 for 45 min at 4 °C, slices were washed in 1xPBS for 1 min at room temperature, then incubated in 0.2 M HCl for 10 min, in 1 % Triton X-100/1xPBS for 2 min and again washed twice in 1xPBS for 30 s. Finally, sections were incubated in 50 % formamide/5xSSC (0.75 M NaCl, 0.075 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) for 5 min. Then tissue was hybridized in hybridization buffer [50 % formamide, 25 % H2O, 25 % Microarray Hybridization Solution Version 2.0 (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany)] containing the probe and incubated in a humid box (50 % formamide) at 65 °C overnight.

After slides were washed twice in 0.1xSSC for 30 min at 65 °C, they were treated with 1 % blocking reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in TBS (100 mM TRIS, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) with 0.3 % Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature (in a humid box) and incubated with an anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (Roche Diagnostics) diluted 1:750 in TBS/0.3 % Triton X-100/1 % blocking reagent at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing twice in TBS for 15 min, hybridization signals were visualized using 0.0225 % NBT (nitroblue tetrazolium) and 0.0175 % BCIP (5-brom-4-chlor-3-indolyl phosphate) dissolved in DAP buffer (100 mM TRIS, pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2) as substrates. Sections were mounted in Vectamount mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, tissue sections adhered to microscope slides were air-dried for 1 h at room temperature and then equilibrated for 10 min in 1xPBS at room temperature prior to overnight incubation at 4 °C with the primary antibody dissolved in 1xPBS supplemented with 0.3 % TritonX100 and 10 % normal donkey serum. After washing 3 times for 5 min each with 1xPBS, detection was carried out with appropriate secondary antibodies dissolved in 1xPBS supplemented with 0.3 % TritonX100 and 10 % normal donkey serum at room temperature for 2 h. To monitor localization of CNGA3, a specific polyclonal antibody [AbmCG3; (Biel et al. 1999)] generated in rabbit was used at a dilution of 1:500. This antibody detects a protein of the expected size (80 kDa) in membrane extracts of HEK293 cells transfected with an expression vector carrying the CNGA3 cDNA (Biel et al. 1999); it has been previously used to stain GG neurons of wild-type mice but has failed to label the GG of CNGA3-deficient conspecifics (Mamasuew et al. 2010). To visualize localization of TREK-1, a specific polyclonal antibody (sc-11556; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) generated in goat was used at a dilution of 1:80. For control experiments, the corresponding blocking peptide (sc11556P; Santa Cruz) was employed. Secondary detection was carried out using appropriate secondary antibodies coupled to Alexa dyes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Counterstaining was performed for 3 min with 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/ml in 1xPBS). Finally, sections were rinsed with H2O and subsequently mounted in Mowiol (33 % glycerin, 13 % Polivinylalkohol 4–88; 0.13 M Tris pH 8).

Microscopy and Photography

Sections were photographed using a Zeiss Axiophot (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Göttingen, Germany). Fluorescence was examined with a SensiCam CCD camera (PCO, Kelheim, Germany) and the Zeiss Axiovision imaging system (Zeiss) with appropriate filter sets. For confocal microscopy, a Zeiss LSM 510 META system was used.

Statistical Analyses

From each animal investigated, all sections along the rostro-caudal extent of the GG were analyzed. For statistical analyses (Fig. 6e and supplemental Fig. 3), all c-Fos-positive cells on these sections were counted. In Fig. 6e, the standard deviation is indicated. The P value was determined by two-tailed paired t test (confidence interval: 0.95) using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. In supplemental Fig. 3C, the standard deviations are indicated.

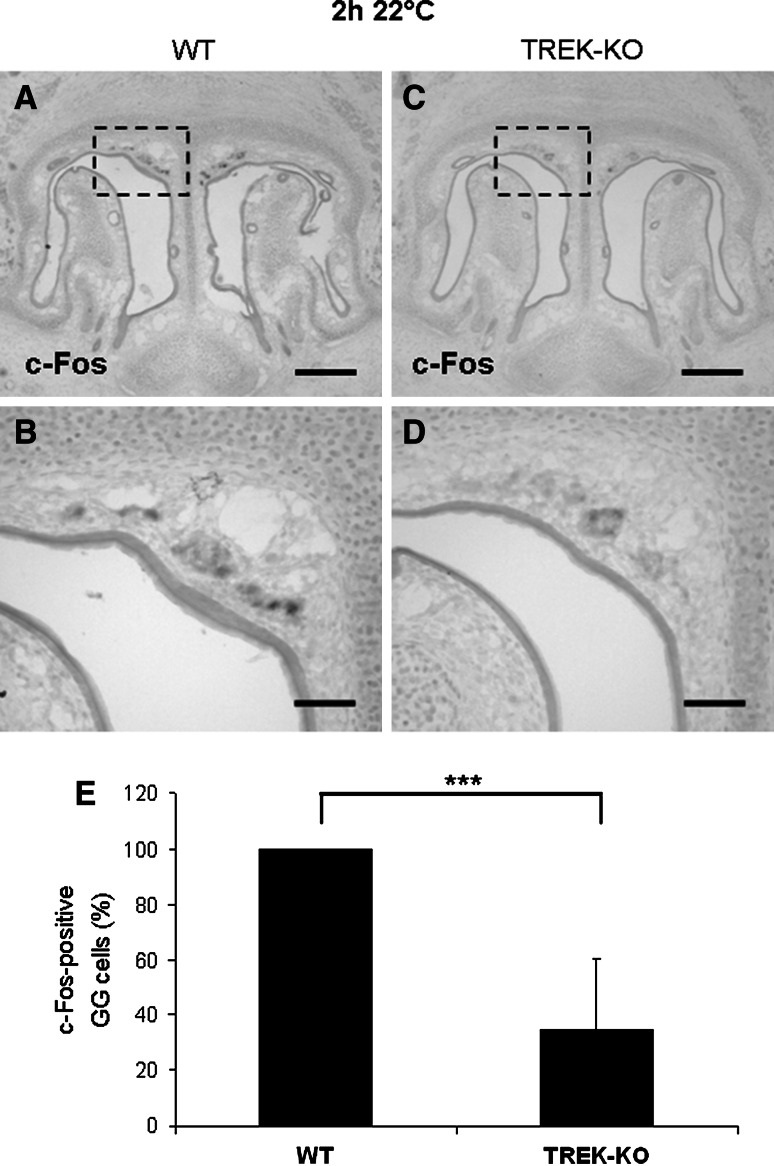

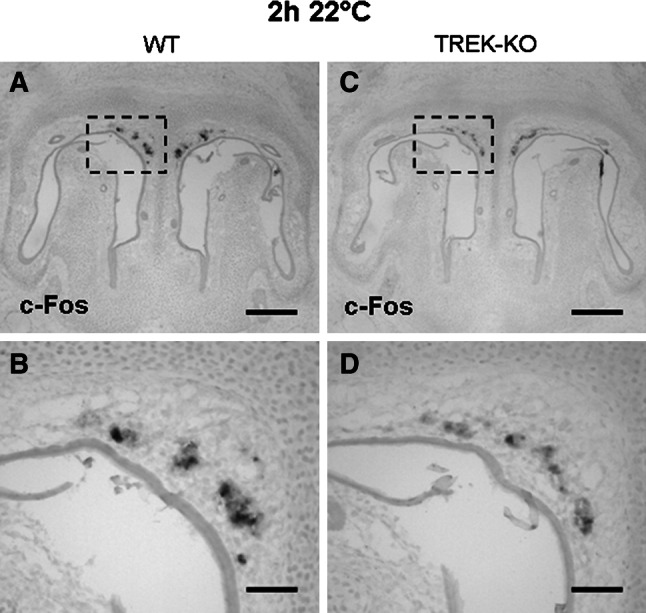

Fig. 6.

Decreased responsiveness to coolness in the GG of TREK-KO mice. a–d Expression of c-Fos in the GG of early postnatal pups was analyzed by in situ hybridization using a c-Fos-specific antisense probe (at a dilution of 1:400). a–b Following an exposure to 22 °C for 2 h, c-Fos signals were clearly observable in the GG of wild-type (WT) mice. c–d Compared with wild-type conspecifics, the number of c-Fos-positive GG cells was reduced in the GG of TREK−/− pups. All figures depicted are representative of 7 experiments. Scale bars a, c = 200 μm; b, d = 50 μm. e Counting the c-Fos-expressing GG cells after exposure to 22 °C for 2 h revealed that the number of these cells is clearly lower in TREK-KO than in wild-type pups. The results are derived from 7 experiments. In each experiment, the number of c-Fos-positive GG cells in a TREK−/− pup was determined relative to that in a concomitantly processed wild-type conspecific, which was set as 100 %. A mean of values, the standard deviation and the P value were calculated (P value <0.0001)

Results

Expression of TREK Channels in Coolness-Activated GG Neurons

In order to determine whether TREK/TRAAK channels are expressed in the GG, PCR experiments were performed. In approaches with intron-spanning (except for TRAAK) primer pairs specific for the coding sequence, for each of the three known thermosensitive TREK channels (TREK-1, TREK-2 and TRAAK), amplicons of the expected size were amplified from cDNA of the murine brain (TREK-1 and TREK-2) or murine genomic DNA (TRAAK) (supplemental Fig. 1). Using the same primer pairs and cDNA from the GG as template, PCR experiments resulted in an amplicon of the expected size for TREK-1 (supplemental Fig. 1). By contrast, only a very faint band was obtained for TREK-2 and no PCR product was observable for TRAAK (supplemental Fig. 1). To explore where in the ganglionic tissue TREK-1 and TREK-2 are expressed, in situ-hybridization studies were performed with specific antisense riboprobes on coronal sections through the GG. As documented in Fig. 1a, b, the antisense probe for TREK-1 stained numerous cells in the GG. In control experiments with the corresponding sense probe, no cells were labeled (Fig. 1c, d), confirming the specificity of the signals obtained with the antisense probe. In line with the very weak amplification from GG cDNA in PCR approaches (supplemental Fig. 1), in situ-hybridization with a TREK-2-specific antisense probe did not result in a detectable staining on GG sections (data not shown). The expression of TREK-1 in the GG was investigated in more detail by immunohistochemistry since an alternative splicing isoform (designated as TREK-1ΔEx4) has recently been identified which lacks the entire C-terminal domain and does not function as an ion channel (Veale et al. 2010). To validate that cells in the GG express the functional isoform, immunohistochemical studies were performed using an antibody specifically directed against the C-terminal domain of TREK-1. The results depicted in Fig. 2a, c show that a TREK-1 protein with a complete C-terminal domain is present in numerous GG cells. In control experiments with the same antibody, tissue sections from animals deficient in both TREK-1 and TREK-2 (hereinafter designated as TREK-KO or TREK−/−) were analyzed; thereby, no detectable immunostaining was observed in the GG of TREK-KO animals (Fig. 2b, d). The evidence for expression of TREK-1 in the GG was further substantiated in approaches in which the above-mentioned antibody was pre-incubated with a corresponding blocking peptide; under these conditions, labeling was strongly diminished (Fig. 2e, f), thus confirming the specificity of the TREK-1 immunostaining in the GG.

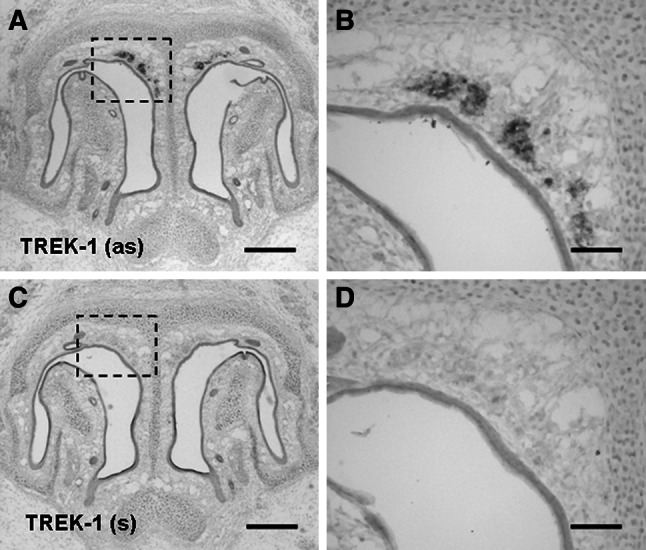

Fig. 1.

Expression of TREK-1 mRNA in the GG. a TREK-1 expression in the GG was visualized by in situ-hybridization with an antisense (as) riboprobe for TREK-1 on coronal sections through the anterior nasal region of a wild-type neonatal pup. c In control experiments, on sections incubated with the corresponding sense (s) probe for TREK-1, no staining was observable in the GG. b, d Higher magnifications of the boxed areas in a, c. Scale bars a, c = 200 μm; b, d = 50 μm

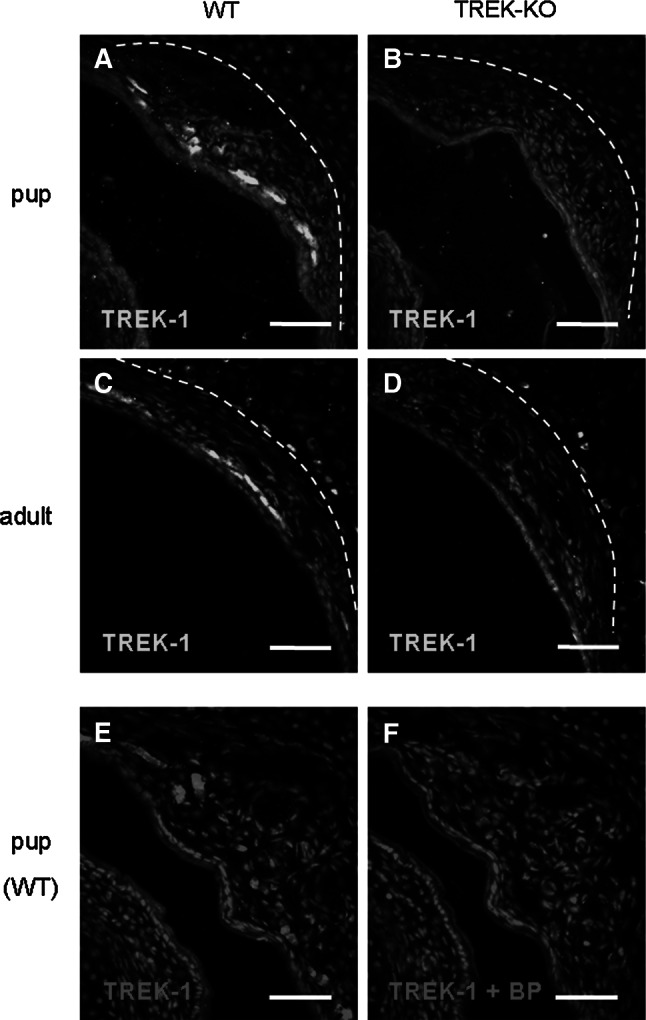

Fig. 2.

TREK-1 protein is expressed in the GG. a–d Immunohistochemical staining with a TREK-1-specific antibody on coronal sections through the GG of wild-type (WT) (a, c) and TREK-KO (b, d) animals. The broken white lines denote the boundary between the mesenchyme harboring GG neurons and the adjacent cartilage tissue. In pups (a–b), TREK-1 immunoreactivity was observed in the GG of wild-type mice (a), whereas no immunolabeling was detectable in the GG of age-matched TREK-KO animals (b). c–d Similarly, in adults, TREK-1 immunoreactivity was clearly observable in the GG of wild-type mice (c) but not in the GG of TREK-KO animals (d). In adult mice, some signals were also detectable in the border region between the nasal mesenchyme and the neighboring cartilage tissue. However, these signals are non-specific since they were observed in both wild-type and TREK-KO animals. e Immunohistochemical staining with the antibody for TREK-1 on a coronal GG section from a wild-type pup. f Immunolabeling was strongly diminished after pre-incubation of the TREK-1 antibody with the corresponding blocking peptide (BP). Sections were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars 50 μm

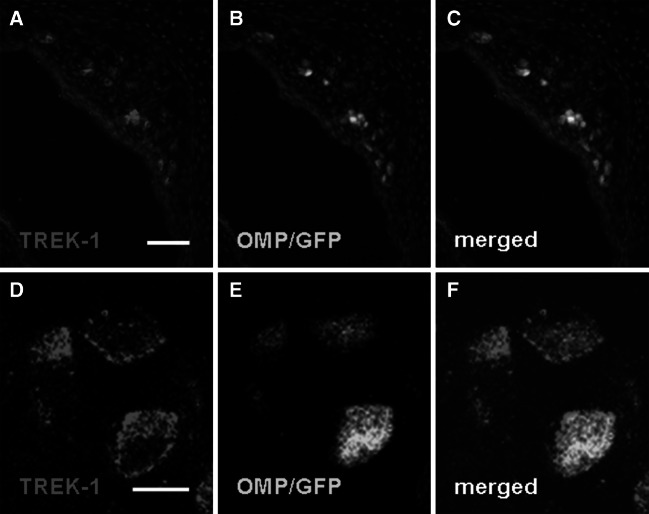

Coolness-evoked responses in the GG are confined to neurons and do not occur in adjacent cells (Mamasuew et al. 2008; Schmid et al. 2010). Since the anterior nasal region harboring the GG comprises different cell types including neuronal, glial and epithelial cells (reviewed by Fleischer and Breer 2010), attempts were made to explore whether TREK-1 is expressed in GG neurons. For this purpose, immunohistochemical staining with the TREK-1 antibody was performed on coronal sections through the GG from OMP/GFP mice; in this mouse strain, GG neurons can be visualized by intrinsic GFP fluorescence (Fuss et al. 2005; Koos and Fraser 2005; Fleischer et al. 2006a). It was found that TREK-1 is in fact expressed in OMP/GFP-positive neurons (Fig. 3a–c). More detailed analyses using confocal laser scanning microscopy revealed that in GG cells the TREK-1 immunoreactivity encircles the central GFP fluorescence, indicating that the TREK-1 protein is localized to the periphery of GG neurons (Fig. 3d–f); a finding which is consistent with the role of TREK-1 as an ion channel in the cell membrane.

Fig. 3.

The TREK-1 protein is expressed by GG neurons and localized to their periphery. a–c Immunohistochemical staining on a coronal section through the GG of an OMP/GFP neonatal mouse with an antibody against TREK-1 (a). Intrinsic GFP fluorescence indicative of GG neurons is shown in b. The overlay (c) demonstrates expression of TREK-1 in GG neurons. d–f Confocal laser scanning microscopy of GG neurons revealed that the TREK-1 immunoreactivity (d) encircles the GFP fluorescence (e). The merged image (f) displays a peripheral localization of the TREK-1 protein in GG neurons. The section in a–c was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars a–c = 50 μm; d–f = 5 μm

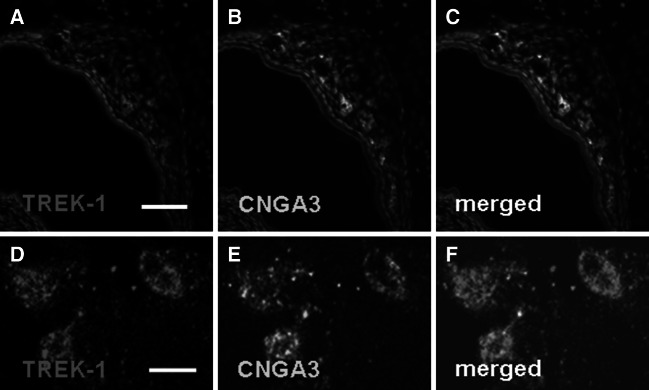

The presence of TREK-1 in coolness-responsive GG neurons is a prerequisite for its potential role in coolness-evoked GG responses. These neurons are characterized by the expression of the cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel CNGA3 (Mamasuew et al. 2010). To scrutinize that TREK-1 is indeed present in the coolness-activated GG neurons, double-staining experiments with an antibody for TREK-1 and an antibody for CNGA3 were conducted which revealed that both proteins are co-localized in the GG (Fig. 4a–c). A closer inspection with confocal laser scanning microscopy demonstrated that TREK-1 is indeed present in the CNGA3-positive GG neurons (Fig. 4d–f), i.e., in the coolness-activated cells of the GG.

Fig. 4.

TREK-1 is present in coolness-responsive (CNGA3-positive) GG neurons. a–c Double–fluorescent immunohistochemistry with antibodies against TREK-1 (a) and CNGA3 (b) demonstrates co-expression of these two proteins in GG neurons (merged image in c). d–f Confocal laser scanning microscopy of GG neurons shows that TREK-1 immunostaining (d) and the immunoreactivity for CNGA3 (e) are localized to the same cells. The section in a–c was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars a–c = 50 μm; d–f = 5 μm

Functional Implications of TREK-1 for Coolness-Evoked Responses in the GG

To assess a potential involvement of TREK-1 in thermosensory signaling of the GG, coolness-induced responses were compared between TREK-KO and wild-type mice. In preceding experiments, it was verified that signaling elements characteristic of coolness-responsive GG cells [CNGA3 and the transmembrane guanylyl cyclase subtype GC-G (Fleischer et al. 2009; Mamasuew et al. 2010)] are expressed in TREK−/− mice (supplemental Fig. 2). To monitor GG responses to given ambient temperatures, expression of the activity-dependent immediate early gene c-Fos was assessed by in situ-hybridization approaches. Previous studies have shown that a cool temperature of 22 °C elicits a significant c-Fos expression in the GG, whereas a warm temperature of 30 °C does not (Mamasuew et al. 2008). Accordingly, it was found that exposure of neonatal pups to a warm ambient temperature of 30 °C for 2 h did not lead to a detectable c-Fos expression, neither in wild-type nor in TREK-KO pups (data not shown). Following an exposure to a cool ambient temperature (22 °C) for 2 h, c-Fos expression (the c-Fos antisense probe was used at a dilution of 1:150) was clearly observable in both mouse strains; however, hybridization signals were more intense in wild-type than in TREK-deficient pups (Fig. 5). In this context, it appeared that wild-type and TREK-KO pups differed in the signal intensity rather than the number of signals. Thus, it seems that TREK-1 is not indispensable for GG activation by coolness, but rather enhances GG responses to cool temperatures. To investigate this enhancing effect on coolness-induced GG activation in greater detail, in a subsequent series of experiments, the c-Fos antisense probe was used at a higher dilution (1:400 instead of 1:150) to visualize only those cells which strongly respond to the stimulus. Employing this approach, following an exposure to 22 °C for 2 h and using the c-Fos probe at a dilution of 1:400, the number of c-Fos-positive cells in the GG of wild-type pubs was reduced by only about 19 % as compared with a dilution of 1:150 (supplemental Fig. 3). However, at this lower concentration of the probe, the number of c-Fos-positive GG cells was substantially different in TREK-KO compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 6a–d). In fact, under these conditions and following an exposure to 22 °C for 2 h, the number of c-Fos-positive cells was about 66 % lower in TREK−/− pups compared with wild-type conspecifics (Fig. 6e). These findings support the concept that TREK channels contribute to coolness-evoked signaling in the GG.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of GG responsiveness to cool ambient temperatures in wild-type and TREK-KO mice. a–d In situ-hybridization experiments with an antisense probe for c-Fos (at a dilution of 1:150) on coronal sections through the GG of wild-type (WT; left panel) or TREK-KO (right panel) pups exposed to a cool ambient temperature (22 °C) for 2 h. Figures b, d show higher magnifications of the boxed areas in a, c. Upon exposure to 22 °C, strong c-Fos expression was observed in the GG of wild-type pups (a–b), whereas c-Fos expression (notably the signal intensity) was weaker in the GG of TREK−/− individuals (c–d). The data shown in figures a–d are representative of 4 experiments. Scale bars a, c = 200 μm; b, d = 50 μm

It has been reported recently that in temperature-sensitive nociceptors, TREK channels are not only important for the intensity of excitation by temperature stimuli but also contribute to define the temperature thresholds of responsiveness (Noël et al. 2009). In order to investigate whether TREK channels may affect the threshold of coolness-induced GG responsiveness, i.e., the temperature from which on responses of GG neurons can be observed, wild-type and TREK-KO pups were exposed for 2 h to various temperatures ranging from 22 to 30 °C (Fig. 7). Exposing pups to 22 °C evoked strong GG responses (Fig. 7a, b). At 26 °C, these responses were markedly weaker but clearly detectable in both wild-type and TREK-KO mice (Fig. 7c, d). At 28 °C, no c-Fos signals were detectable in both mouse lines (Fig. 7e, f). Consequently, although c-Fos signals were weaker in TREK−/− animals, no clear difference concerning the threshold temperature (~26 °C) between these two mouse lines was observed, suggesting that TREK-1 is probably not required to determine the threshold temperature.

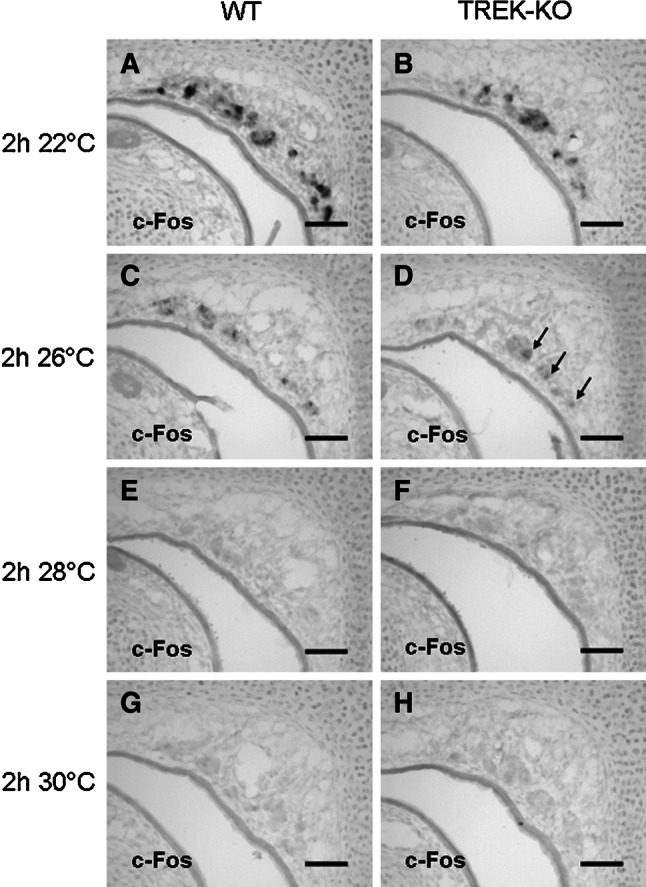

Fig. 7.

TREK-1 is not required to determine the threshold temperature of coolness-induced GG responses. a–h Expression of c-Fos in the GG of wild-type (WT) and TREK-KO pups upon exposure to different ambient temperatures for 2 h was monitored by in situ-hybridization with a c-Fos-specific antisense probe (at a dilution of 1:150) on coronal sections through the anterior nasal region. Substantial expression of c-Fos was induced in the GG of both wild-type (a) and TREK−/− (b) mice following an exposure to 22 °C. Although c-Fos expression was clearly weaker at 26 °C, it was detectable in wild-type and TREK-KO (arrows) animals (c, d). At 28 °C, no coolness-induced response was observed in both mouse lines (e, f). Similarly, no c-Fos signals were visible upon exposure to 30 °C (g, h). The data shown in figures a–h are representative of 4 experiments. Scale bars 50 μm

Discussion

The GG is considered as a dual sensory organ which is activated by distinct chemical substances as well as cool ambient temperatures (Brechbühl et al. 2008; Mamasuew et al. 2008, 2011a, b; Schmid et al. 2010). The mechanisms mediating stimulus-induced GG responses are largely unknown. In particular, the molecular basis for the temperature responsiveness appears to be unique since the GG lacks the coolness-activated ion channel TRPM8 (Fleischer et al. 2009) which is regarded as the principal detector for environmental cold in thermosensory neurons of the trigeminal and the dorsal root ganglion (Bautista et al. 2007; Colburn et al. 2007; Dhaka et al. 2007).

Based on recent studies, it was speculated that a pathway involving signaling elements associated with the second messenger cGMP may contribute to coolness-evoked GG responses (Mamasuew et al. 2010). In search for molecular elements which could render GG neurons responsive to cool temperatures, in this study, we have examined the expression of the thermosensitive TREK/TRAAK ion channels. These potassium channels are activated (i.e., open) at warm temperatures while they are mostly inactive (i.e., closed) at room temperature (Maingret et al. 2000; Kang et al. 2005). Thus, TREK channels should cause a depolarization and thereby could enhance excitability of thermosensory cells by coolness. In line with this concept, previous studies have shown that in thermosensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglion, cold transduction is mediated in part via attenuation of a K+ conductance with properties of TREK channels (Reid and Flonta 2001; Viana et al. 2002). In fact, TREK channels are expressed in a subset of cells in the dorsal root ganglion (Maingret et al. 2000; Talley et al. 2001). Similarly, in the GG, a subset of the neuronal cells expresses the TREK-1 channel (Figs. 3, 4). This finding is consistent with the previous observation that coolness-induced responses in the anterior nasal region appear to occur only in GG neurons, but not in neighboring cells (Mamasuew et al. 2008; Schmid et al. 2010).

The notion that TREK channels play an important role in coolness-evoked responses of thermosensitive GG neurons was strongly supported by the clearly reduced responsiveness of the GG from TREK-KO mice (Fig. 6). However, even in the absence of TREK channels, there was a substantial response of GG neurons to cool temperatures (Fig. 5), suggesting that TREK channels contribute to the thermosensitivity, but additional mechanisms are apparently involved. In this regard, it is interesting to note that thermosensitive neurons of the trigeminal ganglion, co-express TREK-1 with the coolness-activated TRP ion channel TRPM8 (Yamamoto et al. 2009). Thus, co-expression of TREK-1 with other thermoresponsive ion channels may be a general phenomenon; however, the nature of other thermoresponsive proteins in GG neurons is still elusive.

Since a considerable responsiveness to coolness persists in TREK-KO mice (Fig. 5), TREK-1 may not serve as the principal detector for cool temperatures in the GG. Yet, closing of TREK-1 at cool temperatures might contribute to an enhanced depolarization of GG neurons. Accordingly, it is conceivable that TREK-1 may augment the coolness-evoked activation of GG neurons via other thermosensory pathways. In this context, it is interesting to note that temperature sensitivity of several TRP channels has been reported to be voltage-dependent, i.e., when the membrane potential is depolarized, these channels become more sensitive to their relevant temperature stimulus; i.e., their threshold temperature is shifted (Voets et al. 2004). Consequently, inactivation of TREK channels might lead to an enhancement of coolness-induced responses in the GG by shifting the threshold via depolarization of the membrane. However, experiments scrutinizing this concept have shown that the threshold temperature of coolness-induced GG activation is unaltered in TREK-KO mice (Fig. 7). These results indicate that TREK-1 is apparently not determining the threshold temperature of GG neurons and implies that the mechanisms underlying activation by cool temperatures are not substantially affected by the membrane potential. At warm temperatures, one might assume that opening of TREK-1 channels would lead to a hyperpolarization of GG neurons, thus reducing the basal activity of these cells. Consequently, it is conceivable that TREK channels could enhance the contrast between the activated state of these cells at cool temperatures and the inactive state at warmer temperatures.

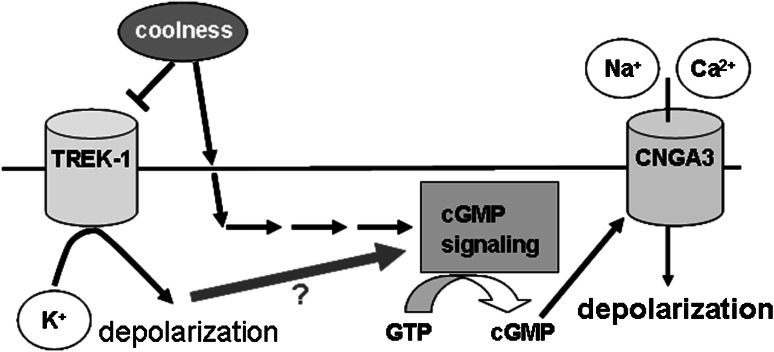

Recently, it has been reported that the cGMP-activated ion channel CNGA3 is essential for coolness-evoked GG responses, suggesting that cGMP signaling plays an important role in GG responses to cool temperatures. In fact, in CNGA3-KO mice, the response of GG neurons to a cool temperature (22 °C) was strongly reduced (Mamasuew et al. 2010). The co-expression of TREK-1 and CNGA3 in GG neurons (Fig. 4) leads to the question whether there is any interaction between coolness-induced responses mediated via cGMP signaling and those mediated via TREK-1. Two different scenarios can be envisioned (Fig. 8). In a first scenario, TREK-1 could operate independently from the coolness-activated cGMP signaling and accordingly would enhance coolness-induced GG responses which are primarily mediated via a cGMP signaling pathway that has its own thermoreceptor. In a second scenario, TREK-1 could function as a thermosensor which operates upstream of cGMP signaling, i.e., the activity of TREK channels would regulate cGMP signaling. This concept has to be scrutinized in subsequent studies.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of the molecular mechanisms underlying coolness-induced activation of GG neurons. Cool temperatures activate GG neurons via TREK-1 and additionally by means of a cGMP pathway. It is unclear whether coolness-evoked inactivation of TREK-1 might impact on cGMP signaling in these cells

In summary, the findings of the present study show that the thermosensitive ion channel TREK-1 is expressed in coolness-responsive GG neurons. Upon elimination of TREK-1, responsiveness to coolness in these cells is reduced. Yet, even in the absence of TREK-1, GG neurons are clearly activated by cool temperatures, suggesting that an additional receptor for coolness is present in the GG.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anne Ullrich, Heidrun Froß, Lena Heuschmid and Helge Fuss for excellent technical assistance. We are indebted to Verena Kretzschmann for her initial contributions to this study and to Michel Lazdunski for critical comments on the manuscript. The OMP/GFP mouse line was kindly provided by Chen Zheng, Paul Feinstein and Peter Mombaerts. The CNGA3-specific antibody was a gift from Martin Biel. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Br712/24-1) and the Fondation pour le Recherche Médicale (équipe labellisée FRM to FL). J. Fleischer was supported by the Humboldt reloaded program of the University of Hohenheim financed by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (01PL11003).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bautista DM, Siemens J, Glazer JM, Tsuruda PR, Basbaum AI, Stucky CL, Jordt SE, Julius D (2007) The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature 448:204–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, Seeliger M, Pfeifer A, Kohler K, Gerstner A, Ludwig A, Jaissle G, Fauser S, Zrenner E, Hofmann F (1999) Selective loss of cone function in mice lacking the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel CNG3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7553–7557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechbühl J, Klaey M, Broillet MC (2008) Grueneberg ganglion cells mediate alarm pheromone detection in mice. Science 321:1092–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn RW, Lubin ML, Stone DJ Jr, Wang Y, Lawrence D, D’Andrea MR, Brandt MR, Liu Y, Flores CM, Qin N (2007) Attenuated cold sensitivity in TRPM8 null mice. Neuron 54:379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A, Murray AN, Mathur J, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Patapoutian A (2007) TRPM8 is required for cold sensation in mice. Neuron 54:371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer J, Breer H (2010) The Grueneberg ganglion: a novel sensory system in the nose. Histol Histopathol 25:909–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer J, Hass N, Schwarzenbacher K, Besser S, Breer H (2006a) A novel population of neuronal cells expressing the olfactory marker protein (OMP) in the anterior/dorsal region of the nasal cavity. Histochem Cell Biol 125:337–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer J, Schwarzenbacher K, Besser S, Hass N, Breer H (2006b) Olfactory receptors and signalling elements in the Grueneberg ganglion. J Neurochem 98:543–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer J, Schwarzenbacher K, Breer H (2007) Expression of trace amine-associated receptors in the Grueneberg ganglion. Chem Senses 32:623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer J, Mamasuew K, Breer H (2009) Expression of cGMP signaling elements in the Grueneberg ganglion. Histochem Cell Biol 131:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss SH, Omura M, Mombaerts P (2005) The Grueneberg ganglion of the mouse projects axons to glomeruli in the olfactory bulb. Eur J Neurosci 22:2649–2664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüneberg H (1973) A ganglion probably belonging to the N. terminalis system in the nasal mucosa of the mouse. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch 140:39–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon A, Tardy MP, Rovère C, Nahon JL, Barhanin J, Lesage F (2009) Glucose inhibition persists in hypothalamic neurons lacking tandem-pore K + channels. J Neurosci 29:2528–2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Guy N, Laigle C, Blondeau N, Duprat F, Mazzuca M, Lang-Lazdunski L, Widmann C, Zanzouri M, Romey G, Lazdunski M (2004) TREK-1, a K + channel involved in neuroprotection and general anesthesia. EMBO J 23:2684–2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Choe C, Kim D (2005) Thermosensitivity of the two-pore domain K + channels TREK-2 and TRAAK. J Physiol 564:103–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koos DS, Fraser SE (2005) The Grueneberg ganglion projects to the olfactory bulb. NeuroReport 16:1929–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret F, Lauritzen I, Patel AJ, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honoré E (2000) TREK-1 is a heat-activated background K(+) channel. EMBO J 19:2483–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamasuew K, Breer H, Fleischer J (2008) Grueneberg ganglion neurons respond to cool ambient temperatures. Eur J Neurosci 28:1775–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamasuew K, Michalakis S, Breer H, Biel M, Fleischer J (2010) The cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel CNGA3 contributes to coolness-induced responses of Grueneberg ganglion neurons. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:1859–1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamasuew K, Hofmann N, Breer H, Fleischer J (2011a) Grueneberg ganglion neurons are activated by a defined set of odorants. Chem Senses 36:271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamasuew K, Hofmann N, Kretzschmann V, Biel M, Yang RB, Breer H, Fleischer J (2011b) Chemo- and thermosensory responsiveness of Grueneberg ganglion neurons relies on cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling elements. Neurosignals 19:198–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noël J, Zimmermann K, Busserolles J, Deval E, Alloui A, Diochot S, Guy N, Borsotto M, Reeh P, Eschalier A, Lazdunski M (2009) The mechano-activated K + channels TRAAK and TREK-1 control both warm and cold perception. EMBO J 28:1308–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Flonta M (2001) Cold transduction by inhibition of a background potassium conductance in rat primary sensory neurones. Neurosci Lett 297:171–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A, Pyrski M, Biel M, Leinders-Zufall T, Zufall F (2010) Grueneberg ganglion neurons are finely tuned cold sensors. J Neurosci 30:7563–7568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana T, Fujiwara N, Nawa T (1990) The ultrastructure of the ganglionated nerve plexus in the nasal vestibular mucosa of the musk shrew (Suncus murinus, insectivora). Arch Histol Cytol 53:147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley EM, Solorzano G, Lei Q, Kim D, Bayliss DA (2001) Cns distribution of members of the two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channel family. J Neurosci 21:7491–7505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale EL, Rees KA, Mathie A, Trapp S (2010) Dominant negative effects of a non-conducting TREK1 splice variant expressed in brain. J Biol Chem 285:29295–29304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F, de la Peña E, Belmonte C (2002) Specificity of cold thermotransduction is determined by differential ionic channel expression. Nat Neurosci 5:254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Droogmans G, Wissenbach U, Janssens A, Flockerzi V, Nilius B (2004) The principle of temperature-dependent gating in cold- and heat-sensitive TRP channels. Nature 430:748–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Hatakeyama T, Taniguchi K (2009) Immunohistochemical colocalization of TREK-1, TREK-2 and TRAAK with TRP channels in the trigeminal ganglion cells. Neurosci Lett 454:129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Shepherd N, Creazzo TL (2008) Temperature-sensitive TREK currents contribute to setting the resting membrane potential in embryonic atrial myocytes. J Physiol 586:3645–3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.