Abstract

Loneliness and associated physical and cognitive health decline among the aging population is an important medical concern, exacerbated in times of abnormal isolation like the 2020–2021 Covid-19 pandemic lockdown. In this backdrop, recent “social prescribing” based health policy initiatives such as community groups as a support structure for the aging population assumes great importance. In this paper, we evaluate and quantify the impact of such social prescribing policies in combatting loneliness and related health degeneration of the aging population in times of abnormal isolation. To this end, we conduct a natural experiment across a sample of 618 individuals aged 65 and over with varying access to community groups during the Covid-19 lockdown period. Using a random-effects, probit model to compare the differences in health outcomes of participants with access to community groups (target) with those without access (control), we find that the target group was 2.65 times less likely to suffer from loneliness as compared to the control group, along with lower incidences of reported cardiovascular and cognitive health decline. These initial findings provide preliminary support in favor of the interventional power of social prescription tools in mitigating loneliness and its consequent negative health impact on the aging population.

Keywords: Covid-19, Social isolation, Loneliness, Cognitive decline, Social prescription, Community groups

Subject terms: Health policy, Human behaviour

Introduction

While social isolation—measured by the frequency of social interactions—and loneliness—assessed by the quality of those interactions—are two distinct concepts in psychology, research indicates a strong correlation between social isolation and declines in physical, mental, and cognitive health of individuals, often triggered by heightened loneliness1–3. Yet, social isolation has been a primary strategy to limit the spread of contagious diseases, as seen during the 2020–2021 Covid-19 pandemic. This presents a critical health challenge: developing mechanisms to safely counter loneliness and associated health declines caused by social isolation, especially among vulnerable populations like the elderly who are at a greater risk of such health challenges. With a shortage of medical professionals overwhelmed by urgent healthcare demands, many governments have turned to “social prescribing,” advocating for community groups as a vital resource in combatting loneliness and associated health decline by acting as a bridge between healthcare professionals and vulnerable populations. This research empirically investigates the effectiveness of social prescribing by examining changes in mental and physical health of 618 seniors with varying access to community groups during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our goal is to document quantitative evidence of the impact of social prescribing measures in times of abnormal isolation, providing policy-makers with necessary data for a comprehensive cost–benefit analysis before broader implementation of such initiatives.

Our primary research hypothesis—social prescribing initiatives like community groups help reduce loneliness and consequent physical and cognitive decline particularly in times of abnormal isolation by increasing social connectedness—is derived from two parallel theories. The first theory, the “loneliness model,” comes from the extensive neurobiological literature connecting social isolation with loneliness4,5. The main contention of the loneliness model is that social isolation breeds insecurity, setting off “social hypervigilance” and negative social expectations. This reinforces a loneliness loop representing a “dispositional tendency” activating neurobiological and behavioral mechanisms that trigger adverse health outcomes, often transmitted through compromised self-regulation6,7. Empirical evidence in support of this theory draws from two pooled-estimates that show a standardized mean difference of 0.28% between pre-pandemic and pandemic loneliness index across nations8–11. However, the impact on different demographics is mixed. For example, longitudinal evidence from Hong Kong notes a larger impact of social isolation on the pre-teen and young adult population compared to the elderly, driven by school and college closures12. This contrasts with the Social Isolation and Loneliness (SI/L) report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) that notes a worsening SI/L index among 7.7 million adults aged 65 and over post-2020 in the United States13. Further, medical research reveals greater health implications of loneliness stemming from isolation, like worsening pain tolerance and perception among the elderly as compared to other age groups14–16. This mixed evidence suggests that while social isolation increases loneliness across all age groups, its health implications are more severe for the senior population. This makes it imperative to design health policies particularly tailored to the needs of the elderly population. Therefore, in this study, we focus on the population aged 65 and above to first quantitatively document the extent of worsening SI/L index during the Covid-19 lockdown17–19. Next, we expand the existing research focus on physical health beyond pain, and cognitive health beyond heightened loneliness, to investigate whether loneliness from social isolation also impacts cardiovascular health and forgetfulness—two significant contributors to comorbidity linked to heart disease and Alzheimer’s in the senior population. We focus on India as an ideal testing ground due to its large elderly population and its implementation of two phases of complete lockdown between 2020 and 2021, reaching100 on the Oxford University Stringency Index as compared to 71 in the United States at the peak of the pandemic20.

The second theoretical premise of this study, “Social Relationship Expectations Framework (SREF),” is derived from the interventional strategy literature21. Traditional medical research identifies three putative mediators of mental health: behavioral, psychological, and biological. A summary of 92 randomized control trials on these three mediators by NASEM shows that psychological interventions, like cognitive behavioral therapy, is successful in reducing feelings of loneliness, followed by behavioral practices like meditation and nature therapy22–24. However, NASEM highlights the challenges of implementing these therapies in times of abnormal isolation due to the need for professional oversight. Instead, NASEM advocates for a social prescribing approach that utilizes SREF mediators, such as social network exchanges, to overcome the functional limitations of the traditional mediators. The American Medical Association describes social prescribing as a “systematic approach to addressing patient’s social needs by referring them to or implementing community-based interventions.” In general, psychological research has uncovered a significant role of community on individual health through association security breeding mindfulness25 and shaping personality traits26. SREF mediators work by using social groups to increase social connectedness, which then acts as a scaffold, reducing self-vigilance and enhancing self-regulation for better health27,21. Medical literature further suggests a parallel multilevel causal model where community groups foster positive social evaluation, reducing cortisol awakening response that predates cognitive deterioration28.

Following these insights, in the aftermath of the Covid-19 lockdown, governments and health regulatory bodies like the NHS started advocating for social prescribing tools where individuals at risk of loneliness-related health degeneration are connected with community groups to foster social connectedness. Countries like Australia and Canada launched initiatives like “Ending Loneliness Together” and “Canadian Institute for Social Prescribing” to establish social interaction groups. Yet, only six qualitative studies of social prescription-based loneliness interventions have been conducted so far with mixed results, some recipients reporting positive interaction with their link workers, while others experiencing an “on-hold” intervention exacerbated by remote check-ins29–31. Given these varied responses, NASEM emphasizes the urgent need for quantitative evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of social prescription tools beyond the current qualitative insights.

In this paper, we conduct a natural experiment on 618 individuals aged 65 and over during the Covid-19 lockdown in Kolkata, India to assess whether community groups—a specific form of social intervention—can effectively reduce social isolation-generated loneliness and its consequent cardiovascular and mental health impact. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first quantitative studies that evaluates such a social prescription-based loneliness intervention in a period of complete social isolation. In our study, we use a two-step approach. First, we measure the impact of the lockdown on the participants using a modified version of the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale32. The UCLA loneliness scale (UCLA LS3-SF3) is a 20-item questionnaire with a provision for self-reported scores intended to gauge emotional health used extensively in previous literature33–35. Next, we evaluate the treatment—access to community groups—using the natural setting of our study population where 295 of the 618 participants (47.74%) live in one of the 11 apartment buildings that formed a community group during the lockdown (target group), while the remaining 323 participants (52.26%) who lived in one of the remaining 17 apartment buildings did not have any such community groups available to them (control group). The community groups, most of them formed during February–April 2020, had three main tasks—conducting weekly in-person check-ins in a socially isolated manner, conducting phone check-ins every evening, and providing a bridge between health professionals and the residents by keeping track of their health needs and arranging for necessary medical care. In addition, the community groups also assisted with day-to-day living needs of the mobility challenged like getting groceries or facilitating pharmacy delivery. Each community group consisted of a team of 8–10 volunteers, working together with a social worker and apartment management, operating under the SREF framework by providing a supportive social scaffolding reducing the need for individual hyper-vigilance. The resulting positive social support is then expected to promote more self-awareness leading to better physical and cognitive outcomes through positive behavioral modifications and lifestyle changes.

Our sample follows a quasi-experimental structure because one group (target) is subject to the treatment—access to active community groups—while the other group (control) is not. To evaluate the suitability of our setup for a natural experiment, we note that in line with traditional randomized control trial (RCT) setups, our sample is cluster-randomized at the site (apartment) level36. Further, self-selection bias is not a major concern as the participants started residing in the apartment buildings before formation of community groups, and no movement across sites during the study period was noted that could have potentially contaminated the sample. The staggered, non-coordinated formation of the community groups further supports a quasi-randomized block design, where access durations varied based on a random initial community group formation date37. The participants are otherwise similar in their demographic and socio-economic characteristics. Given these criteria, we believe that the naturally occurring treatment in our experiment, access to community groups, creates sufficient variability between our target and control groups in line with experimental manipulations in traditional RCT studies. This setup allows us to quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of such community groups by noting any differences in outcomes between the target and control groups.

Using this experimental design, we show how access to community groups during periods of social isolation partially mitigates increased feelings of loneliness. Additionally, we note lower incidences of physical and mental health degeneration, such as worsening cardiovascular parameters and incidences of forgetfulness among the target group, providing preliminary quantitative evidence of effectiveness of social prescription interventions.

Methods

Study design

Kolkata metropolis in India is home to 4.6 million people, with the fastest rising aging population in any Indian city, making it suitable for our study38. The Kolkata Municipal Corporation provides lists of apartment complexes around the city and 28 apartment complexes were selected based on their representative demographic and socio-economic structure. A random sampling methodology was used to recruit participants. In the first stage, a pre-survey questionnaire and documentation describing the purpose and the intended outcome of the study along with any risks of taking part in the survey was shared with potential participants and informed consent (consent form I) was received from all participants before disbursement of the self-reporting survey questionnaire to a select group (see Study Population). Next, the select group received the survey questionnaire along with a second set of informed consent form informing the participants that their responses at this stage would be used in the final analysis (consent form II). We used a cross-sectional design to study the impact of community groups by classifying the apartment complexes into two categories, those with active community groups during the lockdown (target group) and those without (control group). We started our initial pre-survey outreach in June 2022 and concluded our survey in November 2022. The supplementary information contains the details of the data collection process (SI Fig. 1).

Lockdown in India

On 24 March 2020, Government of India announced a complete nationwide lockdown to limit the spread of the coronavirus. The Oxford University tracker gave the lockdown measures in India a score of 100, the highest stringency score in the world (Fig. 1). While the impact of the lockdown in containing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is still being investigated, initial reports suggest that without the lockdown, India would have seen 31,000 more coronavirus cases in a month than it saw in reality39. This complete lockdown sparked a high degree of social isolation that makes India an ideal test case for our study.

Fig. 1.

Government Response Stringency Index in India as calculated by the University of Oxford. The Government of India declared the lockdown on 24 March 2020 as indicated by the green circle in the diagram. The index is a composite of nine response indicators regarding closures of schools, offices, stay-at-home requirements, cancellation of public events, closures of public transport, public information campaigns, restrictions on internal and international travel, with 100 being the strictest condition of lockdown. Our data collection period is from the Summer of 2022 to November 2022. The original source of the government response stringency index: Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R. et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat Hum Behav.5, 529–538; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8 (2021).

Study population

To an initial list of 952 adults aged 65 and over residing across these 28 apartment complexes, we first distributed a pre-survey questionnaire soliciting responses about their mental and physical health as well as their social connection, in particular, if they resided with other family members (besides their spouses) in a multi-family household. This questionnaire also contained details of the study including its purpose and intended outcome as well as details of their intended participation and any associated health risks. Responses and signed informed consent (form I) was received from 794 adults (83.4% response rate) who met the criterion that they did not have multifamily connections or any independent social networks during the lockdown (beyond possible community groups) that would preclude them from the study. These adults received the survey questionnaire and another set of informed consent form (form II).

From the set of responses received in this second stage, we narrowed down our final sample based on a set of exclusion criterion. Following previously cited literature, the exclusion criterion for final sample selection included previous mental health condition requiring anxiolytic agents, opioids, and other stimulants as well as ongoing health challenges like cancer, heart disease, stroke, autoimmune disorders or any other physical ailment that required regular medical intervention. Since we were interested in collecting data on the cardiovascular parameters to study the impact of loneliness on physical health, we also asked the volunteers if they tracked their blood pressure and heart rate regularly before and during the lockdown phase. Finally, we excluded participants who did not provide informed consent. With the exclusion criterion, we finalized a sample of 618 adults, with 346 males (55.99%) and 272 females (44.01%). The final data was anonymized before further analysis to remove any individual identifiers.

Outcome variables

Increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown

Our fundamental variable of interest was any perceived change in loneliness before and during the Covid-19 lockdown period in India. A modified version of the University of Los Angeles Revised Loneliness Scale was used to collect responses32. The scale was modified to include change responses or Δ (comparing lockdown to pre-lockdown experience) to ten questions (corresponding original UCLA LS3-SF3 question number in parenthesis): (1) During the lockdown, I feel more alone than before the lockdown (#4); (2) Over the lockdown period, I feel I am no longer close to anyone compared to before (#7); (3) During the lockdown, there has been a reduction in the number of people I can talk to than before (#19); (4) I feel more isolated during the lockdown than before (#14); (5) Due to the lockdown, I am no longer a part of a friend’s group that I used to be before (#5—answer n/a if not a part of a group before); (6) Due to the lockdown, I have more trouble finding people I can talk to than before (#19); (7) Due to the lockdown, I have more trouble finding people I can turn to when I need than before (#20); (8) Due to the lockdown, I feel more left out than I felt before (#11); (9) During the lockdown, I have lost people I used to feel close to (additional question not included in UCLA LS3-SF3) and (10) I feel more depressed over the lockdown period than I did that I think is the result of my increased loneliness (additional question not included in the UCLA LS3-SF3). We used the same four-point frequency scale as in UCLA LS3-SF3, with 1 corresponding to “Never or Do not agree at all” and 4 corresponding to “Often or Strongly agree.” A rating of 1–2 was classified as mild or no change in feelings of loneliness, 3 corresponded to moderate increase in feelings of loneliness, while 4 corresponded to substantial increase in feelings of loneliness. The Cronbach’s alpha measure of consistency was 0.91, indicating strong internal consistency40.

Physical and mental health parameters

To measure the physical impact of loneliness during the lockdown, we collected data on cardiovascular parameters: (a) systolic blood pressure, (b) diastolic blood pressure, and (c) heart rate. Additionally, we collected data on forgetfulness, considered as an early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, found to be closely related to loneliness. We asked the respondents to report: (i) average systolic and diastolic reading before and during the lockdown phase; (ii) average heart rate before and during the lockdown phase; and (iii) responses, on a scale of 1–4, to the question: “Do you feel you have become more forgetful or have a difficult time remembering things since the lockdown as compared to before?”.

Potential confounders

In order to control for factors beyond the lockdown that could potentially explain any variation in the degree of loneliness observed or any deterioration in the physical and memory related parameters, we used population-based previous cohort studies to control for factors associated with loneliness and physical and mental health classified into four categories: evolutionary changes41, neuroscience related42, epidemiological43, clinical44, and developmental45 factors.

Demographic factors

We collected data on sex, body mass index, and ages of the participants. India comprises of 28 states and 8 union territories, each with its unique language and culture, and people from many states reside in the Kolkata metropolis. Therefore, we also gathered information on familiarity with Bengali, the local language of Kolkata. This was to control for the fact that people might have an easier time connecting if they speak the local language. Additionally, we also collected data on the number of years that they were residing in the apartment complex as these factors are critical for social integration.

Socioeconomic factors

We collected data on employment (currently employed in a job, currently running a business, retired) and current involvement in community organizations or social clubs (classified as “volunteering”), income information (includes pension, investment income, rental income, and income from other sources), education level (less than high school, high school, vocational school, junior or technical college, university, graduate school, or other), marital status (married, widowed/divorced, never married), whether the individual was living alone or with a spouse or partner. In case of joint income of the participants, we calculated the average income of each participant by dividing the annualized income of the household by the number of members (18 and over).

Health, lifestyle, and family history information

We collected data on ongoing chronic health issues including blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes and other age-related chronic ailments. In addition, since lifestyle has been associated with loneliness46, we also collect data on exercise and physical activity of our sample, particularly changes in physical activity during the lockdown period (no change, some change, substantial change) as well as change in sleep patterns (no change, some change, substantial change). In addition, we also collected data on alcohol and tobacco consumption of the participants. Given the evolutionary and genetic factors associated with loneliness, we surveyed the participants to get the family history of mental health challenges by posing the question, “To the best of your knowledge, do you have any immediate family member that was or has been diagnosed or suffering from loneliness or depression? (yes/no/not sure)”.

Statistical analysis

First, we used descriptive statistics (mean/sample proportion and standard deviation) of the potential confounders and their distribution across the three classifications of loneliness determined by the UCLA LS3-SF3 scoring groups to detect patterns in confounders that might explain severity of loneliness, noting any differential impact through ANOVA testing.

Second, we used a random-effects probit regression model to study the differential impact of community groups on the degree of loneliness with the target group coded as 1 and the control group coded as 0. Random effects were used to control for the unobservable sample characteristics. To construct the probit regression model with a binary dependent variable, for each classification, the dependent variable was assigned a value of 1 if the participant belonged to that classification as determined by the survey responses and UCLA LS3-SF3 scoring guidelines, and 0 otherwise. Pseudo R-squared measures were calculated for goodness of fit47. In addition, we conducted a two-tailed test of difference of means and proportions across the target and control samples to make sure that they were comparable and sample heterogeneity beyond the treatment was not driving our results. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Third, we examined the association between the perceived changes in cardiovascular measures and potential risks of Alzheimer’s disease as measured by increased forgetfulness and the degree of loneliness experienced during the Covid-19 lockdown. Given the risk of erroneous self-reported measurements, we used a more conservative estimate of what we considered as an “increase” in these parameters. We defined any observed mean cardiovascular parameter during the lockdown period at least two standard deviations higher than the mean during the pre-Covid period as indicative of worsened cardiovascular health in our baseline (we relaxed the measure to at least one standard deviation in robustness checks), while any change less than one standard deviation was deemed mild or negligible under both baseline and robustness tests. Similarly, a forgetfulness score of 1 or 2 was deemed mild or negligible while 3 or 4 was deemed as substantial, following such categorizations in previous research. The odds ratios (ORs) of the incidences of a rise in systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, heart rate, and indicators of forgetfulness measured across the loneliness classifications were calculated using a multinomial logistic regression model, controlling for potential confounders. We built our models using a “stack” framework where the confounding factor groups were added incrementally such that model 1 includes the demographic factors, model 2 includes the demographic and socioeconomic factors, while model 3 is the complete model including all confounding factors. The p-trends were calculated using a generalized linear model.

Finally, we conducted another set of random-effects probit regressions to examine if having active community groups in apartments help mitigate to some extent the impact of loneliness on physical and mental health. Two alternative methodologies were applied for consistency check. For our main analysis, we used a random-effects probit model with each health measure coded as a binary variable taking a value of 1 in case of a reported increase in the observed measure, and 0 otherwise. The impact of community groups was analyzed separately for each classification of loneliness. In all instances, the complete model including all confounders (model 3) was used for the analysis, with appropriate random effects included to control for any unobserved heterogeneity. The pseudo R-squared measures were reported in each case for goodness of fit. Additionally, as a robustness check, we also conducted another set of probit regressions on the complete sample of 618 participants. Two binary variables and their interactions were used for the purpose, where “Mild or no change in loneliness” takes a value of 1 for incidences of mild or no change in loneliness reported during the lockdown, and 0 for incidences of moderate or substantial increases in loneliness. Similarly, “Community groups” takes a value of 1 for apartments that had active community groups during the lockdown, and 0 otherwise. The dependent variable remained the same in both setups, and appropriate confounders and random effects were included in all instances.

We used Python 3.11 for data cleanup and anonymization and imported the finalized dataset to STATA version 14 (Stata Corp LLC) for our analysis. Any p-value < 0.05 (95% confidence interval in a two-tailed test) was considered as statistically significant for the interpretation of the results. The command “ttest” was used to compare difference in means and the command “prtest” was used to compare any difference in proportional values across the target and control groups for the set of confounding factors controlled for in the regression analysis. The figures were created by the authors using excel software by importing the results from STATA.

Ethics declaration

This study includes survey of human participants. All procedures were conducted following the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. The experimental steps and protocol were reviewed and approved by the ACSEF & B.K. Roy Institutional Review Board as a part of a larger, multi-year study. The purpose, design, any potential risks associated with the survey, and the expected outcome of the study was shared with the participants and informed consent was received. No human images were used in the study and final results were all anonymized and stripped off any identifying and sensitive participant information. No minors were included in the study and no compensation was given to the participants for taking part in the study.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Of the total 618 participants in our study, 305 (49.35%) reported either no change or only a mild increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown as compared to the pre-Covid period, 198 (32.04%) reported moderate increase in feelings of loneliness, while 115 (18.61%) reported substantial increase in feelings of loneliness (Table 1). The distribution across confounding factors reveals some interesting patterns under ANOVA testing. Among demographic factors, participants who were comparatively younger (mean age 73.3 and 74.4 respectively) reported less increase in loneliness as compared to the more aged population (mean age 81.7), and women reported fewer substantial increases in loneliness (39.1%). No noticeable difference was noted in BMI or number of years residing in the apartment complex, though, speaking Bengali, the native language, is associated with less increase in loneliness.

Table 1.

Mean values and proportions of participant characteristics along with their standard deviations of the total sample (n = 618) and by groupings according to intensity of feelings of increased loneliness during the lockdown period.

| N | Total | Feelings of increased loneliness during the lockdown (F-statistics in parenthesis) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild or no change | Moderate increase | Substantial increase |

||||||

| 618 | 305 (49.35%) |

198 (32.04%) |

115 (18.61%) |

|||||

| Mean/ Frequency |

SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Demographic factors | ||||||||

| Age, in years (Mean) | 75.2 | 9.6 | 73.3 | 9.2 | 74.4 (4.01) | 8.3 | 81.7 (8.14) | 9.7 |

| Women (Proportion) | 44.0 | 49.6 | 44.6 (1.87) | 49.7 | 46.0 (3.96) | 49.9 | 39.1 (7.15) | 48.8 |

| BMI (Mean) | 24.2 | 7.8 | 24.3 | 9.5 | 24.4 (2.04) | 5.6 | 23.4 (3.17) | 5.5 |

| Language spoken (Bengali, Proportion) | 63.4 | 48.2 | 66.9 (3.15) | 47.1 | 62.6 (6.18) | 48.4 | 55.7 (4.33) | 49.7 |

| Number of years residing in the apartment complex (Mean) | 24.1 | 13.8 | 23.8 | 14.4 | 24.4 (2.18) | 13.1 | 24.1 (3.15) | 13.1 |

| Socioeconomic factors (proportion) | ||||||||

| Currently employed in a job | 18.5 | 38.8 | 18.7 | 39 | 19.2 (3.99) | 39.4 | 16.5 (5.16) | 37.1 |

| Currently running a business | 20.4 | 40.3 | 23.6 | 42.5 | 17.2 (2.15) | 37.7 | 17.4 (4.04) | 37.9 |

| Retired | 56.2 | 49.6 | 54.8 | 49.8 | 58.6 (3.91) | 49.3 | 55.7 (4.18) | 49.7 |

| Currently volunteering at a social org/club | 15.2 | 35.9 | 16.1 | 36.7 | 13.6 (2.15) | 34.3 | 15.7 (2.87) | 36.3 |

| Top 10% of income level | 0.81 | 9.0 | 0.66 | 8.1 | 1.51 (1.99) | 12.2 | 0.0 (4.14) | 0.0 |

| 75–90% income level | 23.5 | 42.4 | 24.6 | 43.1 | 24.8 (2.89) | 43.2 | 18.3 (4.15) | 38.6 |

| 50–74% of income level | 56.2 | 49.6 | 57.4 | 49.5 | 50.5 (5.16) | 50.0 | 62.6 (5.01) | 48.4 |

| 25–49% of income level | 19.1 | 39.3 | 17.1 | 37.6 | 22.2 (2.22) | 41.6 | 19.1 (3.19) | 39.3 |

| Bottom 25% of income level | 0.49 | 6.7 | 0.33 | 5.7 | 1.01 (1.98) | 10.0 | 0.0 (1.07) | 0.0 |

| Less than high school | 0.16 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.51 (1.44) | 7.09 | 0.0 (1.89) | 0.0 |

| High school graduate | 3.6 | 18.5 | 3.6 | 18.7 | 4.04 (2.22) | 19.7 | 2.6 (1.98) | 15.9 |

| Vocational or some technical degree | 15.1 | 35.8 | 16.1 | 36.7 | 15.7 (1.97) | 36.3 | 11.3 (3.28) | 31.7 |

| 3-year university bachelor’s degree | 62.3 | 48.5 | 61.3 | 48.7 | 63.1 (1.57) | 48.3 | 63.5 (1.09) | 48.2 |

| Professional or master’s degree and above | 18.9 | 39.2 | 19.0 | 39.2 | 16.7 (2.15) | 37.3 | 22.6 (2.73) | 41.8 |

| Married | 70.1 | 45.8 | 68.2 | 46.6 | 72.2 (1.99) | 44.8 | 71.3 (2.15) | 45.2 |

| Widowed/Divorced | 28.0 | 44.9 | 29.5 | 45.6 | 26.3 (3.97) | 44.0 | 27.0 (5.17) | 44.4 |

| Never married | 1.9 | 13.8 | 2.3 | 15.0 | 1.5 (4.78) | 12.2 | 1.7 (4.13) | 13.1 |

| Living alone | 22.5 | 41.8 | 20.0 | 40.0 | 23.7 (5.55) | 42.6 | 27.0 (4.13) | 44.4 |

| Health, lifestyle, and past family history factors (proportion) | ||||||||

| Previous existence of chronic disease | 44.7 | 49.7 | 42.6 | 49.5 | 45.5 (4.15) | 49.8 | 48.7 (5.14) | 50.0 |

| Tobacco or alcohol use | 56.3 | 49.6 | 54.1 | 49.8 | 58.6 (2.22) | 49.3 | 58.3 (4.19) | 49.3 |

| No change in sleep pattern | 27.7 | 44.7 | 29.2 | 45.5 | 31.3 (2.13) | 46.4 | 17.4 (1.11) | 37.9 |

| Some change in sleep pattern | 71.9 | 45.0 | 68.2 | 46.6 | 74.2 (3.18) | 43.7 | 77.4 (3.98) | 41.8 |

| Substantial change in sleep pattern | 3.6 | 18.5 | 2.62 | 16.0 | 4.0 (6.15) | 19.7 | 5.2 (4.02) | 22.2 |

| No change in exercise routine | 25.6 | 43.6 | 27.9 | 44.8 | 25.3 (1.12) | 43.5 | 20.0 (1.89) | 40.0 |

| Some change in exercise routine | 60.2 | 49.0 | 59.3 | 49.1 | 61.6 (2.89) | 48.6 | 60.0 (4.05) | 49.0 |

| Substantial change in exercise routine | 13.3 | 33.9 | 10.8 | 31.1 | 13.1 (5.16) | 33.8 | 20.0 (6.14) | 40.0 |

| Immediate family member with a history | 8.7 | 28.2 | 6.2 | 24.2 | 10.1 (4.10) | 30.1 | 13.0 (7.11) | 33.7 |

The F-statistics of ANOVA tests are reported in parenthesis. In all cases except gender and language spoken, the mean for no to mild loneliness is compared against moderate and severe loneliness across characteristics. For gender and language spoken, mean is compared across genders and across people speaking Bengali versus not speaking Bengali for each of the three loneliness categories. Loneliness was measured by collecting participant responses based on a modified questionnaire prepared using the University of California at Los Angeles Loneliness Scale Version 3 (UCLA-LS3-SF3). A rating of 1–2 was classified as mild to no increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown (305 or 49.35% of the participants), a rating of 3 was classified as a moderate increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown (198 or 32.04% of the participants), while a rating of 4—the highest rating possible, was classified as a substantial increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown (115 or 18.61% of the participants).

Among socioeconomic factors, running a business and being in the top 25% of the income levels was associated with lower feelings of loneliness, consistent with previous surveys14. While education levels and marital status is not associated with increased feelings of loneliness, living alone by choice or life events like death of spouse or divorce is associated with increased feelings of loneliness, consistent with similar patterns noticed for the European aging population during the Covid-19 lockdown48. Health, lifestyle, and past family history show an association with increased feelings of loneliness, as does previous existence of a chronic disease and tobacco or alcohol usage consistent with previous studies46,48. Changes in lifestyle like moderate and substantial changes in sleep patterns as well as lack of exercise and having an immediate family member with a history of depression is associated with increased loneliness, revealing a link between lifestyle, genetics and loneliness41,49.

To study the impact of community groups, the sample was split into a target group of 11 apartment complexes with 295 participants that had active community groups and a control group of 17 apartment complexes with 323 participants that had no active community groups to aid the residents during the lockdown. The two-tailed test of difference of means and proportions of the demographic, socioeconomic, and related factors of the two groups do not reveal significant statistical differences, suggesting comparability (SI Table 1). While some differences are noted among the two groups in the proportion of participants employed in their business and the proportion retired, this evidence is not overwhelming, suggesting self-selection bias is not a major concern in our sample.

Regression results

The impact of community groups on increased feelings of loneliness during the lockdown

We first quantify the impact of having active community groups in the apartment complexes on increased feelings of loneliness during the Covid-19 lockdown as compared to the pre-lockdown period. In our sample, the target group of 295 participants (47.74% of the sample) had community groups that were active during the lockdown, providing social support. The community groups were also active in providing aid to the aging residents in terms of daily life needs like help with grocery, pharmacy visits, hospitalizations, and other forms of assistance as required. The impact of these community groups is presented as results of the random effects probit model applied across the three UCLA-LS3-SF3 scoring groups in Table 2. For each category, the dependent variable takes a value of 1 for participants who belong to that category and 0 otherwise, yielding the probit structure.

Table 2.

Random effects probit regression to evaluate any statistical difference in increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown across the target and control groups, where the target group consists of participants residing in apartments with active community groups during the lockdown and control group consisting of participants residing in apartments without any community groups.

| Feelings of increased loneliness during the lockdown | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild or no increase | Moderate increase | Substantial increase | |

| Model 1 | |||

| Community group (Binary Variable = 1) | 3.14** (1.58) | − 2.85*** (0.91) | − 2.11*** (0.32) |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.41 |

| N | 618 | ||

| Random effects & confounders | Included (Demographic factors) | ||

| Model 2 | |||

| Community group (Binary Variable = 1) | 2.98** (1.44) | − 3.01*** (0.45) | − 2.86*** (0.95) |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.45 |

| N | 618 | ||

| Random effects & confounders | Included (Demographic & socioeconomic factors) | ||

| Model 3 | |||

| Community group (Binary Variable = 1) | 2.65** (1.34) | − 4.12*** (0.91) | − 2.15**(1.02) |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.49 |

| N | 618 | ||

| Random effects & confounders | Included (Complete model) | ||

There are 295 participants who belong to the target group spread across 11 apartment complexes. Participants are denoted by a variable “Community group” that takes a value of 1 for participants who belong to the target group and 0 for participants who belong to the control group. The sample size is 618. The pseudo R-square is measured to indicate goodness of fit. Model 1 controls for demographic confounders, model 2 controls for demographic as well as socioeconomic confounders, while model 3 is the complete model that controls for the entire set of cofounding factors. Random effects are included to control for unobserved heterogeneity in our sample. Regression analysis is carried out across the three classifications of increased feelings of loneliness as categorized by collecting participant responses based on a modified questionnaire prepared using the University of California at Los Angeles Loneliness Scale Version 3 (UCLA-LS3-SF3). For regressions in each category, the dependent variable takes a value of 1 for participants belonging to that category and 0 otherwise. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The target group was 2.65 times more likely to report mild or no increase in loneliness during the lockdown as compared to those participants who experienced moderate or substantial increase in feelings of loneliness. Similarly, the target group was 4.12 times less likely to report moderate increase in feelings of loneliness and 2.15 times less likely to report substantial increase in feelings of loneliness, after controlling for confounding factors and other unobserved heterogeneity. While the coefficients quoted in this paragraph are for model 3, the impact is consistent across all three models, suggesting that our treatment worked as per SREF theoretical predictions.

Association between perceived changes in loneliness and physical and mental health measures

We document the changes in cardiovascular parameters and perceptions of increased forgetfulness across different classifications of perceived increases in loneliness during the lockdown period (Table 3, Figs. 2, 3). 324 or 52.43% of the 618 participants report elevated systolic blood pressure during the lockdown as compared to pre-lockdown period. 274 or 44.34% of the participants report elevated diastolic blood pressure and 251 or 40.62% of the participants report elevated heart rate. Additionally, 340 or 55.02% of the participants report perceived increase in forgetfulness. Increases in cardiovascular parameters are strongly associated with an increase in feelings of loneliness. For example, of the 115 participants who reported substantial increase in loneliness, 87 or 75.65% report an increase in systolic pressure. In contrast, 103 of the 305 participants (33.77%) who report mild to no change in loneliness report increase in systolic pressure. This pattern is observed across all cardiovascular and cognitive parameters. Odds ratio calculations further support this observation. Compared to participants who report mild or no increases in loneliness, reported increases in cardiovascular parameters among participants who report moderate to substantial increase in loneliness is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Similarly, participants who report increase in forgetfulness also report heightened feelings of loneliness. This result is further supported in robustness checks (SI Table 2) that relaxes the classifications to one standard deviation away from the mean.

Table 3.

The association of physical health and forgetfulness with increases in loneliness during the lockdown. Model 1 controls for demographic confounders, model 2 controls for demographic as well as socioeconomic confounders, while model 3 is the complete model that controls for the entire set of cofounding factors.

| Feelings of increased loneliness during the lockdown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild or no increase | Moderate increase | Substantial increase | ||

| Number of people with increased systolic pressure | 103 | 134 | 87 | 324 (52.43%) |

| Number of people with increased diastolic pressure | 98 | 110 | 66 | 274 (44.34%) |

| Number of people with increased heart rate | 104 | 78 | 69 | 251 (40.62%) |

| Number of people with perceived increase in forgetfulness | 104 | 132 | 104 | 340 (55.02%) |

| Model 1 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p for trend | |

| Increase in systolic pressure during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.96 (1.77–2.13) | 2.54 (2.42–2.68) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in diastolic pressure during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.78 (1.62–1.95) | 2.23 (2.14–2.35) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in heart rate during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.94 (1.75–2.11) | 2.18 (2.08–2.30) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in perceived forgetfulness during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.86 (1.41–2.34) | 2.21 (2.09–2.38) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p for trend | |

| Increase in systolic pressure during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 2.01 (1.89–2.13) | 2.15 (2.04–2.31) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in diastolic pressure during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.92 (1.83–2.05) | 2.18 (2.01–2.33) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in heart rate during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 2.11 (1.98–2.31) | 2.17 (2.08–2.26) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in perceived forgetfulness during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.95 (1.73–2.14) | 2.23 (2.04–2.41) | < 0.01 |

| Model 3 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p for trend | |

| Increase in systolic pressure during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.85 (1.71–2.01) | 2.34 (2.05–2.63) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in diastolic pressure during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 1.53 (1.18–1.90) | 2.61 (2.13–3.04) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in heart rate during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 2.16 (2.05–2.27) | 2.83 (2.53–3.13) | < 0.01 |

| Increase in perceived forgetfulness during lockdown versus no increase | 1 | 2.01 (1.75–2.27) | 3.01 (2.87–3.15) | < 0.01 |

OR is the odds ratio and CI is the confidence interval at 95% calculated using a multinomial logistic regression model. Increased feelings of loneliness are categorized by collecting participant responses based on a modified questionnaire prepared using the University of California at Los Angeles Loneliness Scale Version 3 (UCLA-LS3-SF3). p-values were calculated to compare participants with mild to no increase in feelings of loneliness to those in the other categories using the analysis of covariance with Dunnett’s test.

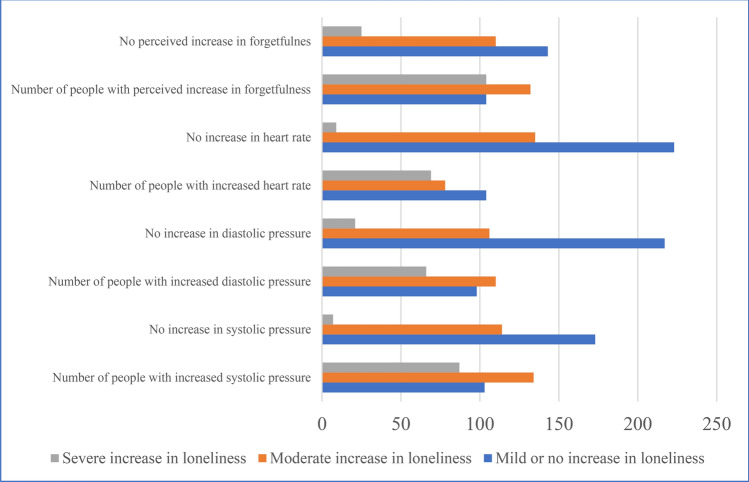

Fig. 2.

Distribution of participants with perceived increases in systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and perceived increase in forgetfulness across classifications of loneliness during the Covid-19 lockdown period. A cardiovascular parameter that was at least one standard deviation higher in the Covid-19 lockdown period as compared to its average value in the pre-lockdown period was considered as an “increase.” Similarly, a forgetfulness score (measured using participant responses to a survey question) of 1 or 2 were deemed mild or negligible while 3 or 4 was deemed as substantial. Loneliness was measured by collecting participant responses based on a modified questionnaire prepared using the University of California at Los Angeles Loneliness Scale Version 3 (UCLA-LS3-SF3). A rating of 1–2 was classified as mild to no increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown, a rating of 3 was classified as a moderate increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown, while a rating of 4—the highest rating possible, was classified as a substantial increase in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown. Data is from a sample of 618 individuals spread across 28 apartment complexes.

Fig. 3.

Association of cardiovascular parameters and forgetfulness with loneliness during the Covid-19 lockdown period. OR indicates the odds ratio, marked on the y-axis, which is calculated using a multinomial logistic regression on model 3 that includes the complete set of confounding factors. Bars indicate the 95% confidence interval band.

Impact of community groups on physical and mental health parameters across loneliness classification

A random-effects probit model is used to quantify the impact of community groups as a moderator for physical health (cardiovascular parameters) and mental wellbeing (changes in reported forgetfulness) across classifications of loneliness during the lockdown (Table 4). The model was applied, one at a time, across the three classifications of loneliness where the dependent variable took a value of 1 if the cardiovascular parameter being considered (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate) and the forgetfulness rating indicated a substantial increase during the lockdown period as compared to the pre-Covid19 period, and 0 otherwise giving the model a probit structure. The analysis was conducted using model 3 with complete set of confounding factors and random effects to control for any unobserved heterogeneity. Pseudo R-squared measures goodness of fit. Across all three measures of cardiovascular health, having access to community groups is associated with lower instances of increase in blood pressure and heart rate. The effect is evident across all classifications of loneliness. Larger magnitude of the coefficients suggests an even stronger mitigating impact on perceptions of forgetfulness, with participants having access to community groups reporting 2 to 2.5 times lower incidences of increase in forgetfulness during the lockdown.

Table 4.

Random effects probit regression to evaluate the moderating effect of community groups on the impact of loneliness on the cardiovascular parameters and perceived increase in forgetfulness during the lockdown period.

| Physical and mental health parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | Heart rate | Forgetfulness | |

| Mild or no increase in loneliness | ||||

| Community group (Binary Variable = 1) | − 1.01*** (0.23) | − 0.67 (0.42) | − 0.98** (0.43) | − 1.97*** (0.56) |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| N | 305 | |||

| Random effects & Confounders | Included (Model 3) | |||

| Moderate increase in loneliness | ||||

| Community group (Binary Variable = 1) | − 2.16*** (0.42) | − 1.06*** (0.29) | − 2.17*** (0.68) | − 2.59*** (0.33) |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.69 |

| N | 198 | |||

| Random effects & Confounders | Included (Model 3) | |||

| Substantial increase in loneliness | ||||

| Community group (Binary Variable = 1) | − 1.74** (0.71) | − 0.99*** (0.32) | − 1.43** (0.69) | − 2.18*** (0.33) |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.62 |

| N | 115 | |||

| Random effects & Confounders | Included (Model 3) | |||

Subsample regressions performed across the three classifications of loneliness categorized by collecting participant responses based on a modified questionnaire prepared using the University of California at Lost Angeles Loneliness Scale Version 3 (UCLA-LS3-SF3).The pseudo R-square indicates goodness of fit. Regressions under model 3 (complete model) that controls for the entire set of cofounding factors. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

To validate the findings, additional robustness checks were conducted across subsamples based on loneliness classifications (SI Table 3) and alternative binary variable structure for loneliness (SI Table 4). Perceived increases in feelings of loneliness was reclassified as a binary variable where mild to no change in loneliness was coded as 1 while moderate or significant changes in loneliness were coded as 0. Therefore, when the interaction variable of community groups and loneliness takes a value of 1, it represents participants who resided in apartment complexes with active community groups and those who had additionally experienced mild or no changes in loneliness during the lockdown. A priori, we expect this group to be least likely to report worsening health outcome. This group is then compared to the rest of the sample. The results show that participants with active community groups and with mild or no increases in feelings of loneliness during the lockdown were, on an average, two times less likely to experience any increase in their cardiovascular parameters or perceptions of loneliness during the lockdown (model 3 full results). The impact is statistically significant across all health parameters, supporting the baseline findings.

Discussion

The Covid-19 pandemic exposed the fault lines of global healthcare systems, revealing strains on an overworked and insufficient medical personnel. In response, recent healthcare policies embraced social prescribing interventions to partially bridge the gap between communities and the healthcare system. Operating under the Social Relationship Expectations Framework (SREF), these interventions are designed to reduce the need for individual hypervigilance activated by isolation by providing a social scaffold. The resulting increase in social interconnectedness helps cultivate a more positive outlook that aids overall health and wellbeing. Yet, beyond a few qualitative studies with mixed evidence, limited quantitative evidence exists evaluating its effectiveness in mitigating health challenges, especially during periods of abnormal isolation21,29–31.

This study aims to address this gap in research by quantitatively assessing the effectiveness of community groups—a form of social prescribing intervention designed to counteract the negative health effects of isolation by promoting positive lifestyle and behavioral changes through a supportive social network. Conducted as a quasi-randomized control trial involving 618 seniors in India during the Covid-19 lockdown, this study capitalized on a natural quasi-experimental setting, where 47.74% of the participants had access to community groups while the rest did not. Using this naturally occurring treatment, this study tracked differences in cardiovascular and cognitive health outcomes of the two groups as a way to assess the impact of community groups during social isolation.

Impact of social isolation on loneliness

Two key insights emerge from this study. First, nearly half of the 618 participants (all aged 65 and older) reported moderate to substantial increases in loneliness due to social isolation, in lines with the predictions of the loneliness model. This is consistent with findings by NASEM for the US senior population as well as studies by Chen and coauthors in China18 and Menze and coauthors in Germany19, where similar percentage increases were observed (around 54.3%). Therefore, our findings reinforce the growing consensus that the Covid-19 pandemic related lockdown universally heightened loneliness across demographics and nations, emphasizing the need for health policy measures to preemptively address such social isolation-related health challenges in future crisis50–52.

Several confounding factors were found to be linked to increased loneliness. Lower income levels and retirement were both strongly associated with increased loneliness, consistent with a study on 25,482 Japanese adults that found poverty to be strongly associated with increased social isolation and loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic14. Similarly, being never married and living alone were disproportionately associated with increased loneliness. However, unlike the Japanese study, we found no significant impact of education on loneliness, likely because most participants in our study were educated, having completed a bachelor’s degree, lacking the variation needed for differential results. Health, lifestyle, and family history also influenced loneliness, with prevalence of a chronic disease, tobacco or alcohol use, disruptions in sleep patterns and exercise routines associated with increased feelings of loneliness, consistent with previous research46,53–55. Loneliness was also associated with family history of depression, consistent with studies linking genetics with loneliness56.

Access to community groups and associated health impact

Social isolation, a biopsychological trigger, impacts mental and physical health through heightened loneliness1–3,10,11. The SREF mediators help mitigate these effects by providing a social scaffold that reduces the need for individual hypervigilance and promotes self-care through positive social connectedness. Within this framework, community groups can serve as effective mediators by providing the necessary social scaffolding to build social networks. While strong social ties—family, neighborhood, and friendship networks—are theoretically predicted to improve emotional health and reduced loneliness, empirical evidence is mixed. For instance, the UK Community Life Survey (2014–2015) showed that while community identification reduced loneliness, the effect varied based on the socio-economic background of the neighborhood studied57. On the other hand, a 3-wave longitudinal study on 222 Chinese adults found that even perceptions of social support help mitigate feelings of Covid-19 induced anxiety58, and a parallel study in Michigan Metropolitan Areas found that seniors who live in vibrant neighborhoods experience lower rates of cognitive decline59.

In line with these latter findings, our results provide convincing evidence of the effectiveness of community groups. Residents with access to such groups in our study were statistically significantly less likely to report increases in loneliness during the lockdown period as predicted by the SREF model27,29,30. Moreover, participants who reported experiencing mild to no increase in loneliness were also less likely to report worsening cardiovascular parameters or memory issues as compared to participants who reported moderate to substantial increases in loneliness. The magnitudes reveal strong correlation between loneliness and associated deterioration of health parameters. For example, of the 115 participants reporting substantial increase in loneliness, cardiovascular worsening was noted for 66–87 participants. 104 of the 115 participants, or 90% reported increased forgetfulness. Of these only 15.63% had access to community groups. This suggests that community groups build a pathway to better physical and cognitive functioning through supportive social contact, as predicted by Cohn-Schwartz60.

Limitations

While one of the strengths of our study is its natural experimental design, which allowed us to compare two otherwise similar groups that differed in their access to community groups, there are many limitations that merit discussion. First, while our sample size is comparable to other experimental studies18,55,61, it is smaller compared to those using secondary data11,12, potentially limiting the statistical power of our analysis. Second, we assumed every participant adhered to the strict lockdown as mandated by the Government of India. However, enforcement of lockdown possibly varied based on civil administration and police vigilance as well as individual compliance. We have not explicitly controlled for enforcement of lockdown (though unobserved heterogeneity was controlled using random effects), which could influence a person’s access to friends, family, and community and hence perceptions of loneliness. Third, a limiting factor of such surveys has been strict restrictions on soliciting information whether participants had themselves contracted Covid-19 or had family members that contracted Covid-1914. This implies that our study, as the studies before us, might be missing an important confounding effect of loneliness during the lockdown that might exacerbate feelings of loneliness due to medically mandated isolation. Fourth, our sample is drawn from India, a country naturally reliant on community and social connections. India traditionally has had a multifamily structure, where social, familial, and neighborhood connections are a dominant force in the socio-economic life of its residents as compared to more individualistic Western nations. For example, according to the Hofstede measure of cultural dimensions62, United States scores 91 out of 100 on “individualism” defined on the basis of “degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members” with a high score indicating lower interdependence, while India scores 48 out of 100 indicating a collectivist society. This implies that the impact of the lockdown and the consequent mitigating effect of community groups as a recourse for the lack of social connectivity due to the lockdown will be stronger in India than in some other nations that are more individualistic. Therefore, while our study provides promising evidence of the interventional power of community groups, we would caution against generalizing these findings and advocate for additional studies from diverse societies before coming to a consensus. Finally, since our study relies on responses from survey participants, self-reporting response bias remains a concern. In particular, emotional and mental health status remains a taboo topic for discussion in India as per the Lissun survey63, so it is possible that our survey responses are subject to social desirability and conformity bias. A larger scale study with a more randomized population or cross-country analysis might provide further comprehensive insights.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is among the first to use a natural experimental setting to objectively evaluate and quantify the impact of community groups as an interventional strategy to mitigate loneliness and associated health challenges of the aging population, as advocated by the SREF mediator theory. Amid growing strains on an already fragile healthcare system, there is increasing recognition of the need for holistic health policies that foster government-community partnership to bridge vulnerable populations with professional healthcare. This need was accentuated during the mandated social isolation to contain the spread of Covid-19.

However, broader implementation of such policies requires data-driven evidence of their effectiveness, and our study contributes to this effort by quantitatively evaluating community groups—a primary social prescription tool. The preliminary evidence in our study is promising with access to community groups showing significantly negative correlation with loneliness and associated health implications of the vulnerable senior population. This suggests potential for SREF based interventional mediators to partially address the logistical limitations of traditional behavioral, psychological, and biological mediators. Although our study focused on a catastrophic event like the Covid-19 pandemic and the consequent lockdown that disrupted life across the globe, the findings can be generalized and they suggest that proactive intervention by community and social groups can play a vital role in countering health challenges faced by the aging population, offering a valuable direction for future health policy.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the survey participants for their assistance. RC thanks the International Institute of Cardiac Sciences for hosting her during this study period. SC (corresponding author) acknowledges financial assistance received from the University of San Francisco Faculty Development Fund Spring 2021.

Author contributions

RC and SC (corresponding author) conceptualized the study and designed the experiment. SC and IN conducted the survey, collected, and cleaned the data for final analysis. RC performed the data analysis. SC (corresponding author) wrote the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. It is not yet available in a public repository as it contains confidential medical information that is part of an ongoing, larger multi-year study. Data requests should be sent to Dr. Suparna Chakraborty: schakraborty2@usfca.edu.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article omitted a citation for Reference 27 in the Introduction. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/28/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-025-90534-x

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-75262-y.

References

- 1.Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci.10, 227–237 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shor, E. & Roelfs, D. J. Social contact frequency and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Soc. Sci. Med.128, 76–86 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, F. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 90 cohort studies of social isolation, loneliness and mortality. Nat. Hum. Behav.7, 1307–1319 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacioppo, J. T. et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. J. Res. Personal.40(6), 1054–1085 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med.40(2), 218–227 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newall, N. et al. Causal beliefs, social participation, and loneliness among older adults: A longitudinal study. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh.26, 273–290 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauder, W., Mummery, K., Jones, M. & Caperchione, C. A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations. Psychol. Health Med.11, 233–245 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis, D. What Scientists have Learnt from Covid Lockdowns. Nature. 609(8) (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Flaxman, S. et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature584, 257–261 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst, M. et al. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc.77(5), 660–677 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Sullivan, R. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness and social isolation: A multi-country study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18(19), 1–18 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tso, W. W. Y. et al. Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry31, 161–176 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2020). 10.17226/25663. [PubMed]

- 14.Yamada, K., Wakaizumi, K., Kubota, Y., Murayama, H. & Tabuchi, T. Loneliness, social isolation, and pain following the COVID-19 outbreak: Data from a nationwide internet survey in Japan. Sci. Rep. Nat.11, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaremka, L. M. et al. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: Understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology38, 1310–1317 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell, V. D. et al. Unwelcome companions: Loneliness associates with the cluster of pain, fatigue, and depression in older adults. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med.7, 2333721421997620 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassam, K. & McMillan, J. M. The impact of loneliness and social isolation during COVID-19 on cognition in older adults: A scoping review. Front. Psychiatry14, 1287391 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, Z. C. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies in China: A 1-year follow-up study. Front. Psychiatry12, 711658 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menze, I., Mueller, P., Mueller, N. G. & Schmicker, M. Age-related cognitive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and associated mental health changes in Germans. Sci. Rep.12(1), 8172 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oxford Stringency Index. Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford, https://ig.ft.com/coronavirus-lockdowns/

- 21.Akhter-Khan, S. C., Prina, M., Wong, G. H. Y., Mayston, R. & Li, L. Understanding and addressing older adults’ loneliness: The social relationship expectations framework. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.18(4), 762–777 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsay, E. K., Young, S., Brown, K. W. & Creswell, J. D. Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA116(9), 3488–3493 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott, A. Kids adopt different ways of coping in wake of the pandemic. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA119(39), 1–5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sachs, A. L. et al. Rationale, feasibility, and acceptability of the meeting in nature together (MINT) program: A novel nature-based social intervention for loneliness reduction with teen parents and their peers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19(17), 11059 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, F., Ren, M. & Oshio, A. The effect of attachment style on mindfulness: Findings from a weekly diary study using latent growth modeling. Curr. Psychol.43, 26395–26402 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, F. & Oshio, A. A secure mind is a clear mind: The relationship between attachment security, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity. Curr. Psychol.43, 11276–11287 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hough, K., Kotwal, A. A., Boyd, C., Tha, S. H. & Perissinotto, C. What are social prescriptions and how should they be integrated into care plans?. AMA J. Ethics25(11), E795-801 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adam, E. K., Hawkley, L. C., Kudielka, B. M. & Cacioppo, J. T. Day-today dynamics of experience-cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA103, 17058–17063 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingkachotivanich, N. et al. Different effects of perceived social support on the relationship between perceived stress and depression among university students with borderline personality disorder symptoms: A multigroup mediation analysis. Healthcare10, 2212 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Husk, K., Elston, J., Gradinger, F., Callaghan, L. & Asthana, S. Social prescribing: Where is the evidence?. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract.69(678), 6–7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris, S. L. et al. Social prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of service providers’ and clients’ experiences. BMC Health Serv. Res.22(1), 258 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell, D., Peplau, L. A. & Cutrona, C. E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.39, 472–480 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkley, L. C. Loneliness and health. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.8, 22 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagawa, S. et al. White matter structures associated with loneliness in young adults. Sci. Rep.5, 17001 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P. & Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA110(15), 5797–5801 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, C. J., Smith, S. N. & Pugatch, M. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs in implementation research. Psychiatry Res.283, 112452 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Festing, M. F. W. The “completely randomised” and the “randomised block” are the only experimental designs suitable for widespread use in pre-clinical research. Sci. Rep.10, 17577 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivaramakrishnan, L. & Roy Bardhan, A. Health and well-being of ageing population in India: A Case Study of Kolkata. In Urban Health Risk and Resilience in Asian Cities. Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences (eds Singh, R. et al.) 13 (Springer, Singapore, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulkarni, S. India would have seen 31,000 coronavirus cases without lockdown: Researches. Deccan Herald. 3 April 2020.

- 40.Taber, K. S. The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ.48, 1273–1296 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cacioppo, J. T. & Cacioppo, S. Loneliness in the modern age: An evolutionary theory of loneliness (ETL). Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol.58, 127–197 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cacioppo, S., Capitanio, J. P. & Cacioppo, J. T. Toward a neurology of loneliness. Psychol. Bull.140(6), 1464 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A metanalytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.10(2), 227–237 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinrich, L. M. & Gullone, E. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.26(6), 695–718 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hutten, E. et al. Trajectories of loneliness and psychosocial functioning. Front. Psychol.12, 2367 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malcolm, M., Frost, H. & Cowie, J. Loneliness and social isolation causal association with health-related lifestyle risk in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst. Rev.8, 48 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veall, M. R. & Zimmermann, K. F. Evaluating Pseudo-R2’s for binary probit models. Qual. Quant.28, 151–164 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delaruelle, K., Vergauwen, J., Dykstra, P., Mortelmans, D. & Bracke, P. Marital-history differences in increased loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic: A European study among older adults living alone. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.108, 104923 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrempft, S. et al. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health19, 74 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banerjee, A. et al. Depression and loneliness among the elderly in low- and middle-income countries. J. Econ. Perspect.37(2), 179–202 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giusti, L. et al. Everything will be fine. Duration of home confinement and “all-or-nothing” cognitive thinking style as predictors of traumatic distress in young university students on a digital platform during the COVID-19 Italian lockdown. Front. Psychiatry11, 1–14 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rettie, H. & Daniels, J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol.76(3), 427–437 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iovino, P., Vellone, E., Cedrone, N. & Riegel, B. A middle-range theory of social isolation in chronic illness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20(6) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Virant, K.W. The Link Between Chronic Illness and Loneliness. Feb 15, 2022. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/chronically-me/202202/the-link-between-chronic-illness-and-loneliness (2022).

- 55.Guerra-Balic, M. et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity, insomnia, and loneliness among Spanish women and men. Sci. Rep.13(1), 2912 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goossens, L. et al. The genetics of loneliness: linking evolutionary theory to genome-wide genetics, epigenetics, and social science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.10(2), 213–226 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNamara, N. et al. Community identification, social support, and loneliness: The benefits of social identification for personal well-being. Br. J. Soc. Psychol.60(4), 1379–1402 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu, J. et al. Perceived social support protects lonely people against COVID-19 anxiety: A three-wave longitudinal study in China. Front. Psychol.11, 566965 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim, M. H., Dunkle, R. & Clarke, P. Neighborhood resources and risk of cognitive decline among a community-dwelling long-term care population in the U.S. Public Health Pract.6, 100433 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohn-Schwartz, E. Pathways from social activities to cognitive functioning: The role of physical activity and mental health. Innov. Aging4(3), igaa015 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lampraki, C., Hoffman, A., Roquest, A. & Jopp, D. S. Loneliness during COVID-19: Development and influencing factors. PLOS One17(3), 1–20 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hofstede, G. Dimension maps of the world: Individualism. Available at https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/. Accessed 23 September 2024.

- 63.Tripathi, S. How To Tackle The Issue Of Indians Still Thinking Of Mental Health & Its Treatment As Taboo. India Times. Dec. 13 2022. https://www.indiatimes.com/lifestyle/mental-health/how-to-prevent-indians-from-thinking-of-mental-health-as-taboo-587429.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. It is not yet available in a public repository as it contains confidential medical information that is part of an ongoing, larger multi-year study. Data requests should be sent to Dr. Suparna Chakraborty: schakraborty2@usfca.edu.