Abstract

Fournier's gangrene is a severe type of necrotizing fasciitis that affects the perineal and genital regions. Because of its rapid progression, Fournier's gangrene is associated with high mortality and morbidity rates. Surgical treatment of Fournier's gangrene requires leaving the wound open and performing multiple debridement procedures. We report a case of Fournier's gangrene caused by Streptococcus anginosus in a 9-year-old boy with severe autism. Because of the patient's condition, surgical treatment included thorough debridement and closure of the initial wound under general anesthesia. This case was successfully treated and the patient was discharged without infection recurrence.

Keywords: Fournier's gangrene, Pediatric case

1. Introduction

Fournier's gangrene (FG) is a type of rapidly progressing necrotizing fasciitis that primarily affects the perineal, genital, and perianal regions. Described by Alfred Fournier in 1883, FG is associated with a high mortality rate because of its aggressive nature. FG commonly occurs in men 50–60 years of age and has an incidence of approximately 0.4 cases per 100,000 adults.1 However, FG can affect individuals of all ages.

Pediatric cases of FG are rare. Necrotizing fasciitis in various anatomical regions, including the perineal area, have been reported, with an incidence rate of 0.08 cases per 100,000 children.2 Etiological factors associated with pediatric cases of FG include omphalitis, strangulated hernia, premature birth, diaper rash, circumcision, and perineal skin abscesses.3, 4, 5

FG treatment includes extensive debridement of infected tissue and the administration of intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics. Additionally, surgical treatment of FG requires leaving the wound open and performing multiple debridement procedures. However, maintaining an open wound is difficult in pediatric cases. We report the case of a 9-year-old boy with a rare case of FG that was successfully treated with surgical closure of the initial wound.

2. Case presentation

A 9-year-old boy with severe autism presented to our emergency department with acute scrotal erythema (Fig. 1). An ultrasound examination of the scrotum revealed normal blood flow in the testicles; therefore, testicular torsion was considered unlikely. We suspected epididymis at that time and discharged the patient with treatment comprising oral antibiotics. Five days after the initial visit, the patient returned with worsening scrotal erythema, swelling, and fever (Fig. 1). Scrotal ultrasonography revealed a hypoechoic area (30 mm × 40 mm) in the right medial scrotum that was not observed during the initial examination (Fig. 2).

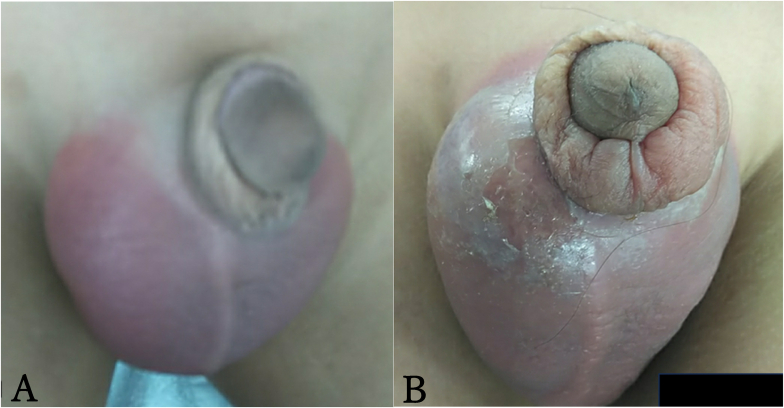

Fig. 1.

Erythema and swelling in the examination of the scrotum

(A) The scrotum at the first visit.

(B) The scrotum after the 5 days from the first visit. Erythema and swelling were worse mainly in the right scrotum.

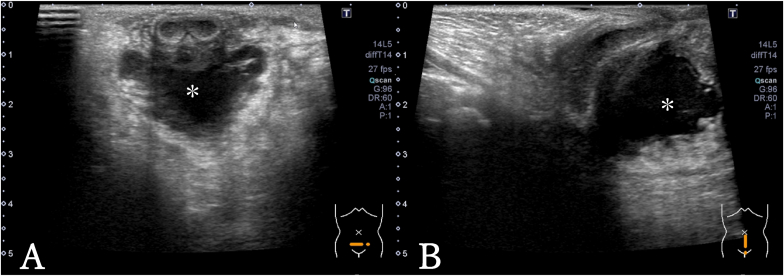

Fig. 2.

US examination of the scrotum

(A) The transverse image. The low echoic lesion was observed on ventral side of urethra (∗).

(B) The sagittal image. The low echoic lesion was observed on ventral side of urethra (∗).

Laboratory tests showed a complete blood count of 29,200 leukocytes/mm3, 85 % segmented neutrophils, and increased acute-phase reactant levels (C-reactive protein level of 17.8 mg/dL). Severe abscess formation in the scrotum was suspected. After FG was diagnosed, surgical drainage was performed and new antibiotic treatment was administered.

A midline incision of the scrotum revealed pus. Extensive debridement of the necrotic tissue was performed under general anesthesia (Fig. 3). The scrotal secretion culture results revealed Actinomyces species and Streptococcus anginosus. Postoperative wounds associated with FG are managed openly. However, because our patient had severe autism, wound management was difficult; therefore, we decided to close the wound with drainage tube (Fig. 3).

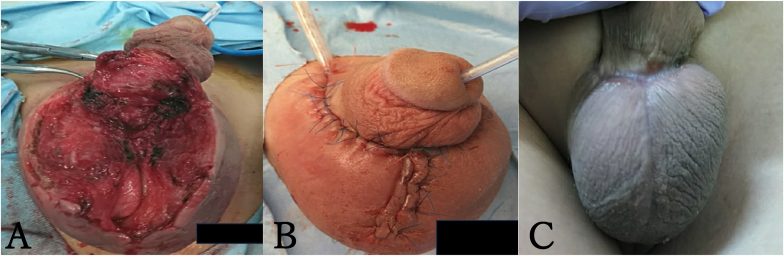

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative and postoperative wound picture.

(A) Extensive scrotal subcutaneous debridement and skin excision.

(B) Primary closure of the wound with drainage tube.

(C) Surgical wound appearance 60 days post-operation.

During the first 3 days postoperatively, the patient was sedated using dexmedetomidine to ensure the stable administration of antibiotics (ampicillin/sulbactam plus clindamycin) and maintain the wound. The sutures were removed on postoperative day 10, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 14.

At 60 days postoperatively, infection recurrence was not observed and the wound remained closed (Fig. 3). At 1 year postoperatively, clinical problems were not observed.

3. Discussion

FG is a severe and quickly progressing type of necrotizing fasciitis caused by a polymicrobial infection that affects the perineal area and genitalia.6 Mortality rates associated with FG range from 11 % to 45 %.7 The necrotizing process is typically initiated by an infection in the anorectum, urogenital tract, or genitalia skin 8. Bacteria produce enzymes, such as collagenase and hyaluronidase, that infiltrate the fascial planes, thus causing vascular thrombosis and subsequent gangrene of the overlying skin 9. These bacteria continue to multiply in the necrotic tissues.

Pediatric cases of FG are rare. Necrotizing fasciitis in various anatomical regions, including the perineal area, have been documented, with an incidence rate of 0.08 cases per 100,000 children.2 Scrotal abscesses can be caused by appendicitis, duodenal perforation, colonic perforation, Cowper's duct cyst infection, and pancreatitis.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 However, our case had no identifiable cause.

The primary therapeutic approach for FG comprises the use of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement. Multiple debridement procedures may be required to remove all necrotic tissue, reduce the bacterial load, and control infection. However, maintaining an open wound can be particularly challenging when the patient is a child, as demonstrated by our case. Therefore, primary wound closure and thorough debridement of the necrotic tissue during the initial surgery should be considered for pediatric FG cases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported pediatric FG case involving closure of the initial wound.

This case highlights the importance of an early diagnosis and aggressive treatment for pediatric cases of FG. Unlike adult patients, pediatric patients often present unique challenges, such as difficult open wound maintenance and the presence of different etiological factors. Further research is necessary to obtain a better understanding of the long-term outcomes of pediatric FG and develop standardized treatment protocols that can be applied across healthcare settings. Additionally, this case emphasizes the need for increased clinical vigilance of FG, especially when it is not initially suspected and particularly for pediatric patients with atypical presentations.

4. Conclusion

FG caused by Streptococcus anginosus was effectively treated with extensive debridement and primary wound closure. Because of the difficulty associated with managing the open wound of pediatric patients, primary wound closure may be an appropriate treatment option. This case highlights a new surgical management option for pediatric FG and the potential to use alternative approaches for similar cases.

Informed consent

The patient's father provided informed consent prior to study participation.

Funding

This work was produced without outside funding contributions.

Data availability

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kohei Mori: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yutaka Shiono: Data curation, Conceptualization. Soichiro Shimura: Data curation, Conceptualization. Shuhei Hirano: Conceptualization. Dai Koguchi: Conceptualization. Masaomi Ikeda: Conceptualization. Hideyasu Tsumura: Conceptualization. Daisuke Ishii: Conceptualization. Kazumasa Matsumoto: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Fournier J.A. Jean-Alfred Fournier 1832-1914. Gangrène Foudroyante de La Verge (overwhelming Gangrene). Sem Med 1883. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:984–988. doi: 10.1007/BF02554904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setiawan F., Sibarani J. A rare case of Fournier's gangrene developing from colon perforation in an infant: a case report. Urol Case Rep. 2024;54 doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2024.102721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thwaini A., Khan A., Malik A., et al. Fournier's gangrene and its emergency management. Postgrad Med. 2006;82:516–519. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.042069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Güneren E., Keskin M., Uysal O.A., Aritürk E., Kalayci A.G. Fournier's gangrene as a complication of varicella in a 15-month-old boy. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1632–1633. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.36200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekingen G., Isken T., Agir H., Oncel S., Günlemez A. Fournier's Gangrene in childhood: a report of 3 infant patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:E39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safioleas M.C., Stamatakos M.C., Diab A.I., Safioleas P.M. The use of oxygen in Fournier's gangrene. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1748–1750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekingen G., Isken T., Agir H., Oncel S., Günlemez A. Fournier's gangrene in childhood: a report of 3 infant patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:e39–e42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton M.D., Fowler J.E., Sharifi R., Pearl R.K. Causes, presentation and survival of fifty-seven patients with necrotizing fasciitis of the male genitalia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laucks S.S., 2nd Fournier's gangrene. Surg Clin. 1994;74:1339–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46485-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyes J., Casas-Melley A.T., Liu C., Epelman M.S., Ellsworth P.I. Scrotal abscess after a perforated appendicitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa058. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahadur A., Singh N., Kashmira M., Shukla A., Gupta V., Jain S. Fecal scrotal abscess secondary to spontaneous retroperitoneal perforation of ascending colon. Case Rep Med. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6658083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saadat P., Borzi P., Patel B., Winkle D. Urethral syringocele: unseen but existing. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:743–746. doi: 10.1111/ans.15039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirhashemi S., Soori M., Faghih G., Peyvandi H., Shafagh O. Scrotal abscess: a rare presentation of complicated necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20:124–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutalo N., Dragisic V., Miskovic J., Soljic M. Scrotal abscess as the first symptom of fatal necrotizing pancreatitis. Saudi Med J. 2019;40:1167–1170. doi: 10.15537/smj.2019.11.24488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.