Abstract

Introduction

Endothelial dysfunction is an early precursor of atherosclerosis and is common in patients with psoriasis, presumably primarily due to psoriasis-related inflammation. We investigated endothelial function, arterial stiffness, and circulating markers of endothelial activation in young patients with psoriasis vulgaris of varying severity, all of whom were effectively treated achieving PASI 90.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 80 patients (54 men/26 women, 30–45 years) who were effectively treated with topical therapy, methotrexate, adalimumab, secukinumab or guselkumab, and 20 healthy controls. Endothelial dysfunction was measured by flow-mediated dilation and arterial stiffness was measured by pulse wave velocity and common carotid artery stiffness. The following circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation were measured: ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E- and P-selectin, GDF-15, and TRAIL.

Results

Endothelial function and arterial stiffness parameters did not differ between patients with effectively treated psoriasis and the control group. Circulating endothelial activation biomarkers did not show relevant differences between the groups of effectively treated patients or controls.

Discussion

Although cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with psoriasis, effective antipsoriatic treatment appears to slow the progression of atherosclerosis, even when there are cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking or obesity. This may suggest that antipsoriatic treatment exerts a cardioprotective effect.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that early and effective treatment of varying-severity psoriasis vulgaris in young patients appears to prevent arterial dysfunction related to psoriasis and consequent cardiovascular risk.

The study is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT05957120).

Keywords: Psoriasis, young patients, endothelial function, arterial stiffness, antipsoriatic treatment

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic immune-mediated disease that affects 2–3% of the population. 1 It is associated with several comorbidities, of which cardiovascular disease is the most common and the main cause of mortality and morbidity in these patients. Psoriasis is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.1,2 In addition to the increased prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, chronic inflammation is probably the main driver of accelerated atherosclerosis in psoriasis patients. 2 Systemic inflammation activates and alters the endothelium, leading to endothelial dysfunction, a first step in atherosclerosis. 3 Activated endothelial cells then further secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, creating a vicious cycle. 3

There are numerous therapies available for the treatment of patients with psoriasis which are very effective in clearing skin lesions in most patients. 1 However, it is not yet known whether this visible improvement is also accompanied by an improvement in systemic inflammation. In view of the increased cardiovascular burden in psoriasis, biologic therapies targeting interrelated cytokines of psoriasis and atherosclerosis are of particular interest. These cytokines include tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-17, and IL-23. 4 These three cytokines have been shown to affect endothelial function through one of three main mechanisms – by exacerbating inflammation by stimulating the synthesis of other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6, by stimulating the expression of adhesion molecules such as endothelial intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), endothelial cell selectin (E-selectin) and platelet selectin (P-selectin), which facilitate adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium and thereby promote inflammation, and by impairing synthesis of nitric oxide, which is a key factor in maintaining vascular tone and preventing atherosclerosis.4,5 In vitro, IL-17 alone has been shown to have minimal effects on endothelial activation, while co-existing TNF-α and IL-17 act synergistically to induce endothelial activation, which then sustains and enhances neutrophil influx. 6 Although these biologic therapies target specific cytokines, they affect not only the primary cytokine, but also others in the downstream immune cascade.1,7 This broader effect on the dysregulated immune system in psoriasis suggests that biologic therapies can also affect arterial function by reducing the overall inflammatory burden and inhibiting the synergistic effects of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines.

It is particularly interesting to investigate whether endothelial dysfunction is already present in young patients with psoriasis who are effectively treated. Endothelial dysfunction is known to be common in patients with psoriasis, 3 but it is not yet known whether effective treatment can stop its development. If this is the case, the concept of early, rapid and complete skin clearing could also be useful in preventing the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Endothelial function can be measured as flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and by measuring circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation, such as soluble adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin) and others, such as growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL).8–10 Furthermore, measurement of arterial stiffness, which reflects the morphology of the arterial wall and is strongly influenced by endothelial cell function, could provide important information about the overall early dysfunction of the arterial wall. 3

The aim of our study was to investigate arterial function, that is, endothelial function and arterial stiffness, as well as circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation, in young patients with psoriasis with varying degrees of severity of psoriasis, but who were all effectively treated to achieve at least Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 11 90 and were in the stable phase of the disease. With such a selection of patients, we could determine whether arterial function (compared to controls without psoriasis of the same age and sex) is altered in these patients and whether there are differences between different therapies. We studied and compared five groups of patients treated with topical therapy, methotrexate, with TNF-α inhibitor adalimumab, the interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitor secukinumab, or with the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab, and controls without psoriasis of the same age and sex.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 80 patients (54 men and 26 women) with psoriasis vulgaris and 20 healthy control subjects, of the same age and sex (11 men and 9 women) at the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic, Department of Dermatovenerology, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia. We recruited consecutive patients who were effectively treated with topical therapy (n = 21), methotrexate (n = 11), adalimumab (n = 14), secukinumab (n = 14) or guselkumab (n = 20). 12 Both patients and physicians had to be satisfied with the response to treatment and did not plan to change treatment. The recruitment of participants lasted from March 2022 to December 2023. The efficacy of the treatment was defined by the Psoriasis Area Severity Score (PASI). Treatment was rated excellent in 99% of patients (PASI < 3) and good in 1% of patients (PASI 3–7). All participants met the following inclusion criteria: diagnosis of psoriasis, age between 30 and 45 years, effective treatment with topical therapy, methotrexate, adalimumab, secukinumab or guselkumab, and stable psoriasis for at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria were previous cardiovascular events, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, menopause, pregnancy or breastfeeding, psoriatic arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases, and any other treatments in addition to treatment of psoriasis. Healthy control subjects aged 30 to 45 years were included with the same exclusion criteria. All participants voluntarily participated in this study and gave their informed written consent. The study was approved by the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (approval number 0120-422/2021/6). The study is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05957120). The reporting of this study conforms to STROBE guidelines. 13 All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 as revised in 2013.

Study protocol

During the study visit, a complete medical history was taken and a complete medical examination was performed on each study participant including the duration of psoriasis, the duration of treatment, and the smoking status. Each participant's anthropometric measurements (weight, height, and waist circumference), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate were determined. Arterial function was evaluated by measuring endothelial function (FMD of the brachial artery) and measurements of arterial stiffness (carotid artery pulse wave velocity (cPWV) and common carotid artery stiffness (β-stiffness)). Furthermore, fasting blood samples were drawn from the antecubital vein of each participant according to the standard procedure and collected in vacuum tubes.

Endothelial dysfunction

Endothelial dysfunction was measured as FMD of the brachial artery. FMD of the brachial artery was assessed according to the guidelines. 14 Measurements were performed after 10 min of rest. Participants were in the supine position with the right hand extended. The diameter of the right brachial artery was continuously monitored and recorded 5–10 cm above the antecubital fossa. After recording the baseline brachial artery diameter for 1 min, the blood pressure cuff on the right forearm was inflated to 50 mmHg above systolic pressure for 4 min to induce arterial occlusion. The cuff was then rapidly deflated to produce reactive hyperemia, and the brachial artery diameter was recorded for a further 3 min. The ultrasound device continuously measured the brachial artery diameter throughout the procedure and automatically calculated the FMD value. The FMD value was expressed as the percentage change in brachial artery diameter from baseline to diameter after reactive hyperemia at the end of the measurement.

Arterial stiffness

Arterial stiffness was determined by carotid artery PWV and common carotid artery β-stiffness measurements. These measurements were performed in the supine position with the head elevated approximately 45° and tilted 30° to the left. The Aloka ultrasound machine automatically analyzed the pulse waves to determine the stiffness parameters. The echo tracker cursor was placed on the anterior and posterior wall approximately 1.5–2 cm proximal to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. Pressure waveforms were obtained non-invasively from changes in arterial diameter and calibrated using systolic blood pressure values. The device then automatically calculated the PWV and β-stiffness of the carotid artery at the end of the measurement.

Laboratory methods

Fasting blood samples were obtained from each participant by venipuncture according to the standard procedure and collected in 4 mL vacuum tubes containing clot activator. The serum was prepared by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 20 min. The serum was promptly aliquoted after centrifugation and stored at ≤ -70 °C until analysis. Serum levels of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E- and P-selectin, GDF-15 and TRAIL were measured with xMAP© technology using magnetic beads coupled with specific antibodies (all R&D Systems, USA) on a MagPix instrument (Luminex Corporation, USA).

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated considering that the normal values in our laboratory for healthy subjects are 7.0 +/- 0.9% for FMD and 5.2 +/- 0.9 m/s for PWV and the clinically relevant difference is 1.0% for FMD and 1.0 m/s for PWV with power = 80 and α 0.05, which requires 13 patients in each group. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2) and IBM SPSS Statistics 28. Due to the non-normal distribution of the data and the presence of outliers, the characteristics of the patients were represented by group medians and interquartile ranges. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test the null hypothesis that the medians of the populations are the same. Fisher's exact test was used to determine whether a significant relationship exists between two categorical variables. To determine whether subclinical atherosclerosis markers varied by type of psoriasis treatment, Quade's nonparametric ANCOVA test was used, with systolic blood pressure and age included as covariates in the model. In cases where ANCOVA yielded significant results, pairwise comparisons were performed using Fisher's least significant difference method (LSD). As this method does not sufficiently control the type I error rate, the Benjamini-Hochberg correction was subsequently applied. In addition to the main analyses, we calculated the partial eta squared to measure the effect size in the ANCOVA, where values of 0.01, 0.06 and 0.14 are considered small, medium and large effect sizes, respectively.

Results

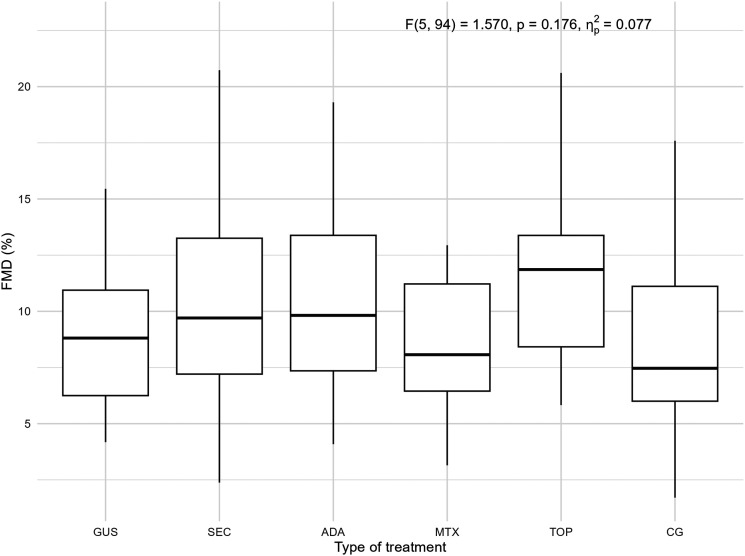

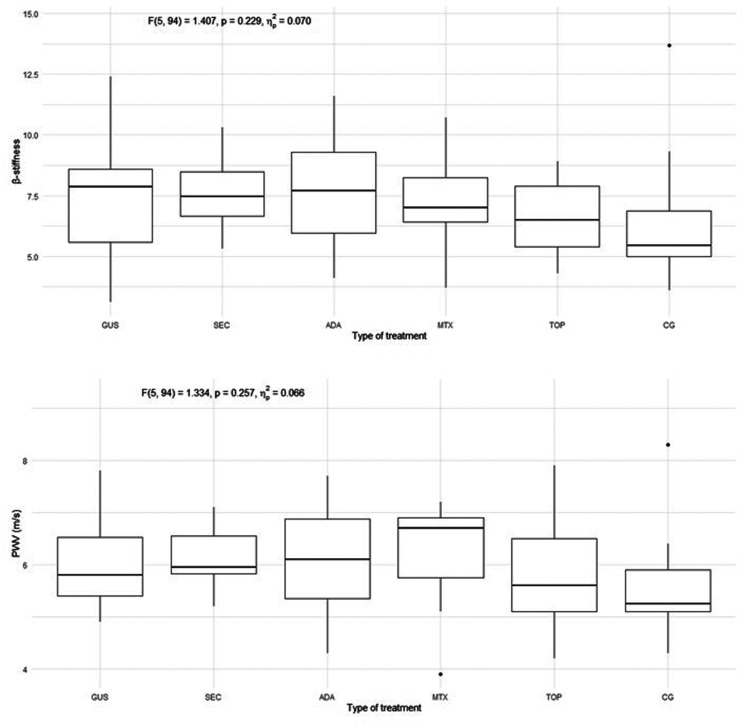

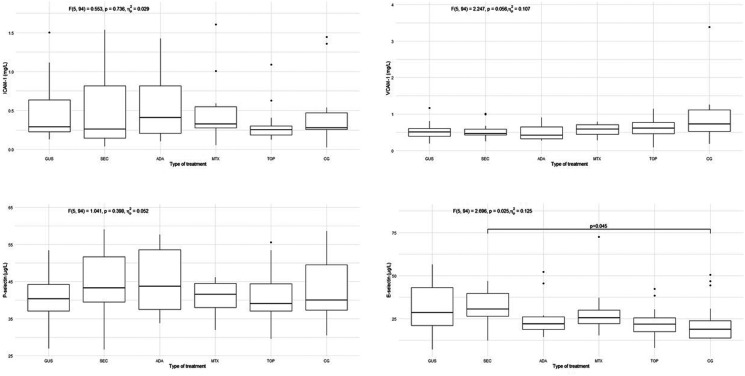

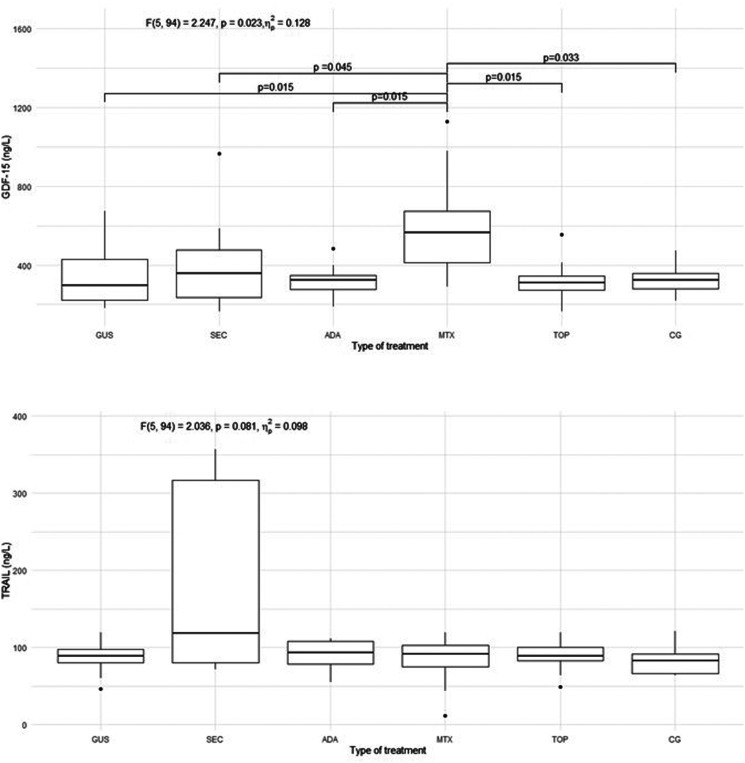

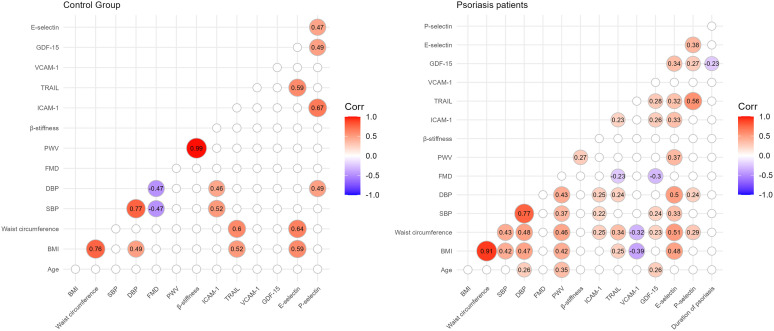

The characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. Of the included patients, 37% were smokers and 65% had a high body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, while in the control group 30% were smokers and 40% had a high BMI and waist circumference. The groups differed from each other in duration of psoriasis, duration of treatment, BMI, waist circumference, PASI, and body surface area (BSA). There were no statistically significant differences in endothelial function measured by FMD in the 5 psoriasis groups compared to each other and compared to the control group, as shown in Figure 1. There were no statistically significant differences in arterial stiffness measured by PWV and β-stiffness in the 5 psoriasis groups compared to each other and compared to the control group, as shown in Figure 2. Most of the selected circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin) or subclinical atherosclerosis (TRAIL) showed consistent changes compared to controls or different treatment modalities, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. On the other hand, there was a statistically significant increase in E-selectin in the secukinumab group compared to the control group. Furthermore, GDF-15 was higher in the methotrexate group compared to all other treatment groups and the control, but we did not find a significant difference between the other groups and the control. The correlation matrix in Figure 5 also shows correlations between arterial function, selected circulating endothelial activation biomarkers, demographic data of the patients, and anthropometric measurements. In the patient groups, BMI and waist circumference were positively correlated with PWV, TRAIL, and E-selectin. Additionally, FMD was negatively correlated with TRAIL and GDF-15.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients. Data are presented as the median (interquartile range), or number of cases for categorical variable. The P-value in the last column was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis H-test or Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test. CG, control group; TOP, topical therapy; MTX, methotrexate; ADA, adalimumab; SEC, secukinumab; GUS, guselkumab; BMI, body mass index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, BSA, Body Surface Area, BP, blood pressure.

| Patients’ characteristics | CG | TOP | MTX | ADA | SEC | GUS | Test statistic p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 34.50 (31.25–39.75) | 38.00 (32.00–41.50) | 39.00 (35.00–42.00) | 39.50 (36.75–41.00) | 39.50 (34.50–43.25) | 40.00 (36.00–43.00) | H = 9.312 P = 0.097 | |

| Gender | Male | 12 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 13 | Exact test P = 0.905 |

| Female | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||

| Smokers No. (%) | 6 (30) | 7 (33) | 3 (27) | 7 (50) | 8 (57) | 4 (20) | Exact test P = 0.242 | |

| Duration of psoriasis (years) | / | 8.0 (4.5–20.0) | 10.0 (5.0–12.0) | 20.0 (11.5–25.0) | 16.5 (13.75–23.25) | 20.0 (15.0–23.5) | H = 16.646 P = 0.002 | |

| Duration of treatment (months) | / | 77.0 (47.0–239.0) | 29.0 (21.0–47.0) | 95.0 (61.0–117.5) | 48.0 (33.5–59.0) | 31.0 (27.3–51.0) | H = 31.059 P < 0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.30(23.40–26.75) | 23.36 (22.59–26.18) | 28.05 (22.65–37.51) | 27.04 (23.62–30.66) | 31.04 (26.75–35.39) | 27.50 (24.54–34.96) | H = 17.766 P = 0.003 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.00 (79.75–94.00) | 86.00 (77.50–94.50) | 104.00 (92.00–121.50) | 93.25 (89.125–109.375) | 104.50 (98.00–113.50) | 99.25 (85.625–108.875) | H = 24.767 P < 0.001 | |

| PASI | / | 0.2 (0.1–1.75) | 1.2 (0.7–3.2) | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) | 0.0 (0.0–0.65) | 0.0 (0.0–0.6) | H = 17.393 P = 0.002 | |

| BSA (m2) | / | 1.0 (1.0–1.5) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.25) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | H = 20.849 P < 0.001 | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 127.00 (116.00–138.00) | 124.00 (110.00–132.50) | 137.00 (129.00–142.00) | 121.00 (110.25–133.25) | 123.00 (118.00–133.25) | 120.00 (110.75–136.75) | H = 8.948 P = 0.111 | |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 84.50 (77.25–90.00) | 79.00 (73.00–84.50) | 83.00 (80.00–95.00) | 81.50 (72.00–92.25) | 83.50 (81.00–93.25) | 84.50 (74.00–96.75) | H =7.084 P = 0.214 | |

Figure 1.

FMD measured endothelial function in the 5 groups of patients with psoriasis and the control group. FMD, flow-mediated dilation; GUS, guselkumab; SEC, secukinumab; ADA, adalimumab; MTX, methotrexate; TOP, topical therapy; CG, control group. Quade's ANCOVA was performed, and when the result was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05), an LSD post hoc test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction was conducted. Only statistically significant pairs are shown in the figure.

Figure 2.

Arterial stiffness measured by β-stiffness and PWV in all 5 groups of psoriasis patients and control group. PWV, pulse wave velocity; GUS, guselkumab; SEC, secukinumab; ADA, adalimumab; MTX, methotrexate; TOP, topical therapy; CG, control group. Quade's ANCOVA was performed, and when the result was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05), an LSD post hoc test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction was conducted. Only statistically significant pairs are shown in the figure.

Figure 3.

Circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E- and P-selectin) in all 5 groups of psoriasis patients and control group. ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; E-selectin, endothelial selectin; P-selectin, platelet selectin; GUS, guselkumab; SEC, secukinumab; ADA, adalimumab; MTX, methotrexate; TOP, topical therapy; CG, control group. Quade's ANCOVA was performed, and when the result was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05), an LSD post hoc test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction was conducted. Only statistically significant pairs are shown in the figure.

Figure 4.

Circulating biomarkers of subclinical atherosclerosis (GDF-15 and TRAIL) in all 5 groups of psoriasis patients and control group. GDF-15, growth differentiation factor 15; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; GUS, guselkumab; SEC, secukinumab; ADA, adalimumab; MTX, methotrexate; TOP, topical therapy; CG, control group. Quade's ANCOVA was performed, and when the result was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05), an LSD post hoc test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction was conducted. Only statistically significant pairs are shown in the figure.

Figure 5.

The correlation matrix shows the Spearman coefficients are shown for the control group (left) and for the psoriasis patients (right). Only significant correlations are shown, others are omitted from the matrix (α=0.05). BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; PWV, pulse wave velocity; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand; GDF-15, growth differentiation factor 15; E-selectin, endothelial selectin; P-selectin, platelet selectin.

Discussion

The most important finding of our study is that there were no significant differences in endothelial function between effectively treated young (30 to 45-year-old) patients with psoriasis and healthy controls of the same age and sex. Furthermore, there were no differences in endothelial function between patients with psoriasis treated with different therapies (topical therapy, methotrexate, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab). We found similar results for arterial stiffness, which was expected, as these two are considered dynamically related. 15 Overall, these results support the hypothesis that achieving complete or near-complete skin clearance is associated with endothelial function comparable to that of the control group, regardless of the therapy used. Applied to clinical practice, this could mean that complete or near-complete clearance of skin lesions appears to be an important preventive measure for arterial dysfunction (subclinical atherosclerosis) and the prevention of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in psoriasis. Most circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation also did not show a convincing degree of endothelial activation. However, GDF-15 was significantly higher in the methotrexate group suggesting a lower attenuation of inflammatory burden, and E-selectin was significantly higher in the secukinumab group compared to controls. However, this did not appear to have a significant effect on the functional and morphological properties of the arteries.

We selected the five treatments (topical therapy, methotrexate, adalimumab, secukinumab and guselkumab) because they were the most widely used therapies for psoriasis in Slovenia. Moreover, the last three are human monoclonal antibodies and are involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis through clinical studies or hypothesized mechanisms.16,17 These treatment groups also indirectly reflect the severity of psoriasis, with milder cases effectively treated with topical therapy and moderate to severe cases with methotrexate or biologic therapy. We selected an age range of 30 to 45 years to ensure that the patients had psoriasis long enough to affect the endothelium, while also minimizing the presence of cardiovascular risk factors that require treatment, such as arterial hypertension or the effects of menopause. Furthermore, a large study of healthy subjects has shown that endothelial function declines significantly after age 45, even in the absence of cardiovascular risk factors, 12 leading us to exclude potential older participants.

Endothelial dysfunction is considered a crucial early event in the development of atherosclerosis. 18 Various factors, including circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, activate endothelial cells directly and indirectly, resulting in altered endothelial function. This leads to impaired arterial relaxation, prothrombotic state, increased leukocyte adhesion, increased endothelial permeability, and remodeling of the arterial wall. 19 In addition, lifestyle factors such as smoking, an unhealthy diet high in fats and sugars, visceral obesity, and lack of physical activity have been shown to have a negative impact on endothelial function. 20 Smoking, for example, directly affects endothelial function by reducing nitric oxide. 21 In addition to all these factors, which are common in patients with psoriasis, several studies have shown that endothelial dysfunction is altered in patients with psoriasis, especially in the most severe forms due to systemic inflammation.22–24

Nevertheless, there are no comprehensive data on how systemic inflammation and antipsoriatic treatment affect endothelial function in patients with psoriasis. It is quite possible that predominantly inflammation-related endothelial dysfunction behaves differently from non-inflammation-related endothelial dysfunction. To this end, we measured and compared endothelial function in young patients with psoriasis who were exposed to psoriasis-related inflammation that was presumably resolved with effective antipsoriatic treatment. In the group of young patients, the long-term non-inflammatory effect is usually not present, allowing investigation of inflammation-related endothelial dysfunction. Previous studies have focused on comparing endothelial function before and after different antipsoriatic treatments22,25,26 or in patients with mild psoriasis. 27 Some of these studies have shown some degree of improvement in endothelial function, while others have not. It is not yet fully understood how effective antipsoriatic therapy affects (subclinical) atherosclerosis. This is particularly true for the latest biologic treatments such as various IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors. Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to have a positive effect on atherosclerosis, but it has no effect on microvascular endothelial function in patients with psoriasis. 25 On the other hand, a systematic review showed that TNF-α inhibitors can improve endothelial function in psoriasis. 26 An improvement in FMD was also observed in patients treated with secukinumab. 22 However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials found no beneficial effect on imaging biomarkers (FMD and aortic inflammation) in patients treated with adalimumab and secukinumab compared to placebo. 28

Our study is the first to date to comprehensively investigate all these parameters in patients with psoriasis treated with 5 different modalities. In contrast to other studies, we found that endothelial function in our group of patients, which has not been extensively studied before, is comparable to endothelial function in healthy controls of the same age and sex. Our results could be of great clinical relevance, as they emphasize the importance of early treatment with complete or near-complete skin clearance which could reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis.

Arterial stiffness is also a parameter that describes the deterioration of arterial wall function and is characteristic of early atherosclerosis. 29 Unlike endothelial function, it reflects morphological rather than functional properties of the arterial wall. Like endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness has an independent predictive value for cardiovascular events. 29 Arterial stiffness has been shown to increase in young patients with psoriasis and in patients with a moderate to severe form of psoriasis compared to healthy controls and is associated with psoriasis-related inflammation.3,30,31 Unlike previous studies, we found that arterial stiffness in young, effectively treated patients was comparable to that in control subjects, which has not been previously reported. It is evident that the effective treatment of young patients with psoriasis is associated with unaffected endothelial function and arterial stiffness comparable to those of healthy controls of the same age and sex.

Due to the activation of immune-mediated mechanisms, the arterial endothelium in psoriasis exhibits a pro-inflammatory phenotype with up-regulation of chemotactic, pro-atherogenic and vascular adhesion molecules, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1, IL-6 and the IL-17 family of cytokines, interferon and VCAM-1. 28 The downstream consequences lead to arterial inflammation and direct cytokine-induced injury. 28 We have shown that the measurements of arterial function in young patients with psoriasis who are effectively treated do not differ from those of the control group. However, there were some statistically significant differences between these groups in the expression of circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation. We found that GDF-15 was significantly increased in the methotrexate group compared to all other groups. However, this result should be taken with caution due to the insufficient sample size in the methotrexate group, especially since we did not find corresponding significant differences in the other parameters of endothelial function. Additionally, GDF-15 has been shown to be a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with psoriasis, 10 but there were no significant differences in FMD, β-stiffness and PWV in the methotrexate group compared to other groups. Therefore, this finding seems to be insignificant. However, we found an increase in the level of E-selectin in the secukinumab group compared to the control group. The link between significant differences observed in GDF-15 and E-selectin could also be attributed to BMI and waist circumference, since we observed a positive correlation in the patient and control groups between BMI and waist circumference on one side and E-selectin on the other. We also observed a positive correlation between waist circumference and GDF-15 in the groups of patients. Other authors have shown that E-selectin levels were significantly reduced in patients with psoriasis after treatment with adalimumab or methotrexate.32,33 However, in another study, E-selectin and VCAM-1 levels were higher in the adalimumab group than in the methotrexate and control groups. 34 In vitro, IL-17 and TNF-α have been shown to synergistically stimulate the adhesion molecules secretion. 6 Therefore, it could be expected that the adalimumab and secukinumab groups would have the lowest levels of adhesion molecules. However, we did not observe this trend consistently. We believe that the few differences between groups are merely incidental findings that occur in numerous comparisons. Furthermore, circulating marker concentrations tend to fluctuate much more than imaging methods such as FMD and PWV, making them more reliable for evaluating arterial function. 35

It is interesting that, while we found a correlation between BMI and waist circumference on the one hand and arterial stiffness on the other, we did not find significant differences in arterial function parameters between the groups. Patients with psoriasis and additional cardiovascular risk factors, such as obesity and smoking, may be expected to have more impaired arterial function. Given the high proportion of smokers (37%) and overweight patients with psoriasis patients (65% had a high BMI and waist circumference) in our study, it would be expected that biologic-treated patients, who generally had more severe psoriasis and a high BMI, would have a greater impairment of arterial function. However, we did not find significant differences in arterial function between groups in imaging studies or by circulating markers of endothelial activation. This is interesting since most studies suggest that more severe disease is associated with more impaired arterial function and also higher levels of some adhesion molecules, such as P-selectin.4,33,36 We found a significant difference in E-selectin only between controls and secukinumab group, which is probably a coincidental result, as we did not observe a consistent trend for other adhesion molecules. However, we observed that BMI and waist circumference were positively correlated with PWV, TRAIL, and E-selectin in the patient and control groups, as shown in Figure 5. Additionally, FMD was negatively correlated with TRAIL and GDF-15, but only in the group of patients, confirming TRAIL and GDF-15 as subclinical markers of atherosclerosis. These results emphasize the importance of treating overweight/obesity for the prevention of subclinical atherosclerosis.

A limitation of our study is the small number of participants in each group, although the power calculations showed that it was sufficient, except in the methotrexate group. Therefore, the results for the methotrexate group should be interpreted with caution. Although ideally only non-smoking and non-obese patients should be included, we also included smokers and obese patients in the study to reflect the ‘typical’ population of psoriasis, in which smoking, and obesity are common. Smoking in patients with psoriasis is estimated to be 20–30% and is higher than in the general population. 37 This high prevalence of smoking among patients with psoriasis is also consistent with our results, where 37% were smokers and 65% of patients were overweight. We also included smokers and overweight participants in the control group, where the proportion of smokers was 30% and 40% were overweight. However, the inclusion of smokers and overweight patients also provided important information that despite their high proportion in the psoriasis groups, the arterial function of the patients with psoriasis was still comparable to that of the control group. Furthermore, the measurement of circulating biomarkers is currently only used for research purposes. Therefore, there are still many unanswered questions, such as which biomarkers are the most specific and sensitive for endothelial dysfunction in patients with psoriasis. Another limitation of our study is that it is an observational study, and we do not have longitudinal data that would allow us to assess endothelial function and arterial stiffness over a longer period. However, despite the small sample size, our results may provide clinically valuable insights into the status of endothelial function in patients with effectively treated psoriasis. Future studies are likely to focus on determining the best marker or set of markers for endothelial dysfunction in patients with psoriasis. Identification of these markers would greatly facilitate the diagnosis and monitoring of endothelial function in patients with psoriasis.

Conclusions

Our study shows that young patients with psoriasis with varying degrees of disease severity, but effectively treated with different therapies (topical therapy, methotrexate, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab), have endothelial function and arterial stiffness comparable to their controls of the same age and sex without psoriasis. Furthermore, despite the high proportion of smokers and overweight people among these patients, this did not appear to have a significant effect on endothelial function and arterial stiffness with effective antipsoriatic treatment. Of the various circulating biomarkers of endothelial activation tested, none appear to replace endothelial function measurement by imaging methods (FMD, β-stiffness and PWV). Applied to clinical practice, our results suggest that early and effective treatment of varying severity psoriasis is necessary in young patients to prevent endothelial dysfunction related to psoriasis and the consequent cardiovascular risk. For the prevention of subclinical atherosclerosis, the most important factor, in addition to the successful treatment of psoriasis, appears to be the treatment of overweight/obesity.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504241287893 for Arterial function is preserved in successfully treated patients with psoriasis vulgaris by Eva Klara Merzel Šabović, Tadeja Kraner Šumenjak and Mojca Božič Mijovski, Miodrag Janić in Science Progress

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization - E.K.M.Š. and M.J., Methodology - E.K.M.Š., M.J., T.K.Š. and M.B.M, Investigation - E.K.M.Š. and M.J., Resources - E.K.M.Š. and M.J., Formal analysis - T.K.Š., Writing – Original Draft - E.K.M.Š. and M.J., Writing – Review and Editing - E.K.M.Š., M.J., T.K.Š. and M.B.M., Supervision – M.J., Funding Acquisition – M.J.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Consent to participate: All patients included in the study gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Data availability statement: A link to our data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (approval number 0120-422/2021/6).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the ARIS Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency research and infrastructure program P3-0308 Atherosclerosis and thrombosis.

ORCID iDs: Eva Klara Merzel Šabović https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1634-1868

Mojca Božič Mijovski https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1879-6353

Miodrag Janić https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7073-8922

Statements and declarations: Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Yamazaki F. Psoriasis: comorbidities. J Dermatol 2021; 48: 732–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masson W, Lobo M, Molinero G. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther 2020; 37: 2017–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anyfanti P, Margouta A, Goulas K, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in psoriasis: an updated review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022; 9: 864185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsiogka A, Gregoriou S, Stratigos A, et al. The impact of treatment with IL-17/IL-23 inhibitors on subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with plaque psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Biomedicines 2023; 11: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egeberg A, Gisondi P, Carrascosa JM, et al. The role of the interleukin-23/Th17 pathway in cardiometabolic comorbidity associated with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 1695–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin GK, Newton G, Tarrio ML, et al. IL-17 and TNF-α sustain neutrophil recruitment during inflammation through synergistic effects on endothelial activation. The Journal of Immunology 2012; 188: 6287–6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamanaka K, Yamamoto O, Honda T. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: a review. J Dermatol 2021; 48: 722–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakshmanan S, Shekar C, Kinninger A, et al. Association of flow mediated vasodilation and burden of subclinical atherosclerosis by coronary CTA. Atherosclerosis 2020; 302: 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varona JF, Ortiz-Regalón R, Sánchez-Vera I, et al. Soluble ICAM 1 and VCAM 1 blood levels alert on subclinical atherosclerosis in non smokers with asymptomatic metabolic syndrome. Arch Med Res 2019; 50: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser H, Wang X, Kvist-Hansen A, et al. Biomarkers of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with psoriasis. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 21438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis – oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatology 1978; 157: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skaug EA, Aspenes ST, Oldervoll L, et al. Age and gender differences of endothelial function in 4739 healthy adults: the HUNT3 fitness study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013; 20: 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alley H, Owens CD, Gasper WJet al. et al. Ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery in clinical research. J Visualized Exp 2014; 92: e52070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janić M, Lunder M, Šabovič M. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular therapy. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valaiyaduppu Subas S, Mishra V, Busa V, et al. Cardiovascular involvement in psoriasis, diagnosing subclinical atherosclerosis, effects of biological and non-biological therapy: a literature review. Cureus 2020; 12: e11173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wierzbowska-Drabik K, Lesiak A, Skibińska M, et al. Psoriasis and atherosclerosis—skin, joints, and cardiovascular story of two plaques in relation to the treatment with biologics. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leite AR, Borges-Canha M, Cardoso R, et al. Novel biomarkers for evaluation of endothelial dysfunction. Angiology 2020; 71: 397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gimbrone MA, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2016; 118: 620–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Man AWC, Li H, Xia N. Impact of lifestyles (diet and exercise) on vascular health: oxidative stress and endothelial function. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020; 2020: 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higashi Y. Smoking cessation and vascular endothelial function. Hypertens Res 2023; 46: 2670–2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Stebut E, Reich K, Thaçi D, et al. Impact of secukinumab on endothelial dysfunction and other cardiovascular disease parameters in psoriasis patients over 52 weeks. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 1054–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarian OI, Bolotna LA. Treatment of endothelial dysfunction with rosuvastatin in patients with psoriasis. Archives of the Balkan Medical Union 2019; 54: 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alba BK, Greaney JL, Ferguson SBet al. et al. Endothelial function is impaired in the cutaneous microcirculation of adults with psoriasis through reductions in nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2018; 314: H343–H349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyldenløve M, Jensen P, Løvendorf MB, et al. Short-term treatment with methotrexate does not affect microvascular endothelial function in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brezinski E, Follansbee M, Armstrong Eet al. et al. Endothelial dysfunction and the effects of TNF inhibitors on the endothelium in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des 2014; 20: 513–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dattilo G, Imbalzano E, Casale M, et al. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: correlation between psoriasis and cardiovascular functional indices. Angiology 2018; 69: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.González-Cantero A, Ortega-Quijano D, Álvarez-Díaz N, et al. Impact of biological agents on imaging and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol 2021; 141: 2402–2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schutte AE, Kruger R, Gafane-Matemane LF, et al. Ethnicity and arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020; 40: 1044–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gisondi P, Fantin F, Del Giglio M, et al. Chronic plaque psoriasis is associated with increased arterial stiffness. Dermatology 2009; 218: 110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yiu KH, Yeung CK, Chan HT, et al. Increased arterial stiffness in patients with psoriasis is associated with active systemic inflammation. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang N, Jiang M, Fan Y. Association between psoriasis and subclinical atherosclerosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zdanowska N, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Czerwińska J, et al. Methotrexate and Adalimumab decrease the Serum levels of cardiovascular disease biomarkers (VCAM-1 and E-selectin) in plaque psoriasis. Medicina (B Aires) 2020; 56: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campanati A, Goteri G, Simonetti O, et al. Angiogenesis in psoriatic skin and its modifications after administration of etanercept: videocapillaroscopic, histological and immunohistochemical evaluation. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2009; 22: 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mućka S, Miodońska M, Jakubiak GK, et al. Endothelial function assessment by flow-mediated dilation method: a valuable tool in the evaluation of the cardiovascular system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 11242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garbaraviciene J, Diehl S, Varwig D, et al. Platelet P-selectin reflects a state of cutaneous inflammation: possible application to monitor treatment efficacy in psoriasis. Exp Dermatol 2010; 19: 736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eder L, Shanmugarajah S, Thavaneswaran A, et al. The association between smoking and the development of psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504241287893 for Arterial function is preserved in successfully treated patients with psoriasis vulgaris by Eva Klara Merzel Šabović, Tadeja Kraner Šumenjak and Mojca Božič Mijovski, Miodrag Janić in Science Progress