Abstract

Background

Intense pyrethroid resistance threatens the effectiveness of the primary vector control intervention, insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), in Nigeria, the country with the largest malaria burden globally. In this study, the epidemiological and entomological impact of a new type of ITN (piperonyl-butoxide [PBO] ITNs) distributed in Ebonyi State were evaluated. The epidemiological impact was also compared to the impact of standard pyrethroid-only ITNs in Cross River State.

Methods

A controlled interrupted time series analysis was conducted on monthly malaria incidence data collected at the health facility level, using a multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial model. Data were analysed two years before and after the PBO ITN campaign in Ebonyi State (December 2017 to November 2021). A pre-post analysis, with no comparison group, was used to assess the impact of PBO ITNs on human biting rates and indoor resting density in Ebonyi during the high transmission season immediately before and after the PBO ITN campaign.

Results

In Ebonyi, PBO ITNs were associated with a 46.7% decrease (95%CI: -51.5, -40.8%; p < 0.001) in malaria case incidence in the 2 years after the PBO ITN distribution compared to a modelled scenario of no ITNs distributed, with a significant decrease from 269.6 predicted cases per 1000 population to 143.6. In Cross River, there was a significant 28.6% increase (95%CI: -10.4, 49.1%; p < 0.001) in malaria case incidence following the standard ITN distribution, with an increase from 71.2 predicted cases per 1000 population to 91.6. In Ebonyi, the human biting rate was 72% lower (IRR: 0.28; 95%CI 0.21, 0.39; p < 0.001) and indoor resting density was 73% lower (IRR: 0.27; 95%CI 0.21, 0.35; p < 0.001) after the PBO ITNs were distributed.

Conclusions

The epidemiological and entomological impact of the PBO ITNs underscore the impact of these ITNs in areas with confirmed pyrethroid resistance. These findings contribute to ongoing research on the impact of new types of ITNs in Nigeria, providing critical evidence for the Nigeria National Malaria Elimination Programme and other countries for future ITN procurement decisions as part of mass ITN campaign planning and malaria programming.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12936-024-05137-0.

Keywords: Malaria, Piperonyl butoxide, Insecticide-treated nets, Vector control

Background

Insecticide treated nets (ITNs) have been essential tools in the global effort to reduce the burden of malaria. Estimates suggest that 68% of all averted malaria cases between 2000 and 2015 were due to the use of ITNs [1]. ITNs are the primary vector control intervention in Nigeria, where malaria continues to be one of the main public health challenges in the country. From 2000 to 2015, malaria case incidence in Nigeria decreased from 413.3 to 294.1 cases per 1000 population, a 28.8% decline, but since 2016, case incidence has remained relatively stable, fluctuating between 294.1 and 312.7 cases per 1000 population [2]. In 2021, despite the progress made, Nigeria still accounted for 26.6% of global malaria cases and 31.3% of global malaria deaths, with an estimated 65 million cases and nearly 200,000 deaths [2]. Malaria control efforts have been challenged by worsening, widespread insecurity in the northeast and northwest areas of the country, as well as documented resistance of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato (s.l.) mosquitoes to pyrethroid insecticides [3, 4].

To address the growing challenge of widespread resistance to pyrethroids among mosquito populations [5–7], new types of ITNs have been developed. PBO ITNs are a pyrethroid ITN with a piperonyl butoxide (PBO) synergist, whereby PBO enhances the efficacy of the pyrethroid insecticide through inhibition of metabolic enzymes that contribute to the detoxification of the insecticide [8]. PBO ITNs have since been conditionally recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a malaria control intervention in areas with confirmed intermediate levels of pyrethroid resistance [9]. Studies in Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda found significantly lower parasite prevalence in communities that received PBO ITNs compared to those that received standard (pyrethroid-only) ITNs up to 21 months post-distribution [10–12]. A systematic literature review found that PBO ITNs were generally more effective than standard ITNs in areas of high and moderate insecticide resistance, but that more research on the impact of these nets over their intended life span [13] and the cost-effectiveness of the PBO ITNs is needed.

With the WHO’s High Burden High Impact approach [14], the Nigeria National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) has continued to focus on stratification and sub-national tailoring of malaria control interventions. Entomological data from 2017 through 2019 found high intensity resistance to both deltamethrin and permethrin among An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes from sampling sites in four local government areas (LGAs) in Ebonyi State, and that pre-exposure of the mosquitoes to a PBO synergist resulted in full and partial restoration of susceptibility for deltamethrin and permethrin, respectively [4, 15, 16]. Using a data-driven decision matrix, the NMEP and U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) decided to distribute PBO ITNs via mass distribution in Ebonyi in November 2019, the first PBO ITN campaign in Nigeria. In neighbouring Cross River State, resistance monitoring results from the same time period showed An. gambiae s.l. in five of the six LGA sampling sites were fully susceptible (≥ 98% mortality) to deltamethrin and alpha-cypermethrin but were resistant to permethrin at all LGA sampling sites [15]. As such, standard deltamethrin-only ITNs were distributed via mass distribution in Cross River in June 2019.

This study evaluates: (1) the impact of PBO ITNs on malaria case incidence in Ebonyi, where An. gambiae s.l. has confirmed high intensity pyrethroid resistance, (2) how the impact of PBO ITNs in Ebonyi compares to the impact of standard ITNs in Cross River, and (3) the impact of PBO ITNs on entomological indicators (human biting rate and indoor resting density) in a setting of confirmed high intensity pyrethroid resistance.

Methods

Study setting

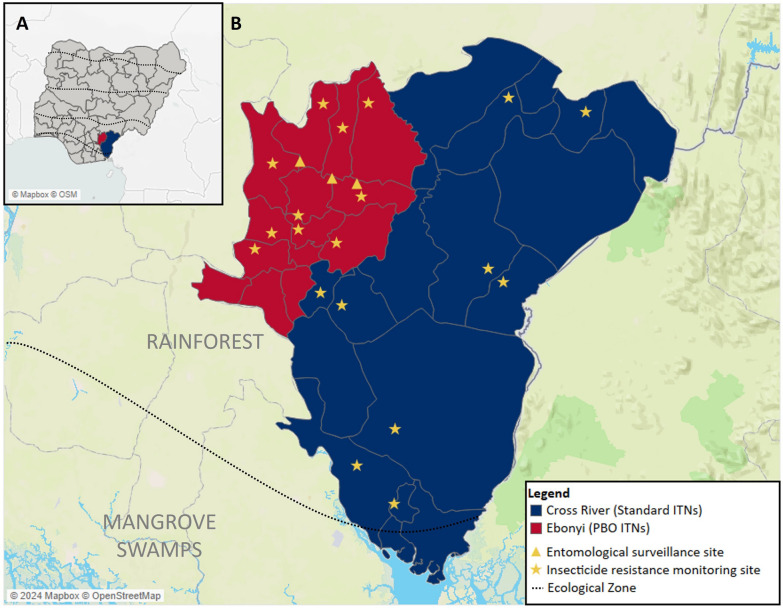

Nigeria is divided into six geopolitical zones and 36 states, with Ebonyi State located in the South-East zone and Cross River State located in the South-South zone (Fig. 1). Ebonyi is further divided into 13 LGAs and Cross River into 18 LGAs. Population estimates from microplanning in 2019 reported 3.1 million people lived in Ebonyi and 4.3 million people lived in Cross River.

Fig. 1.

Map of study site showing A a map of Nigeria with the two study states highlighted; B Local government areas that received PBO ITNs (red) and standard ITNs (blue) with the locations of the entomological surveillance and insecticide resistance monitoring sites. Ecological zones indicated by the dotted lines

Both states are in the southern part of the country in the rainforest ecological zone, with the most southern part of Cross River located in the mangrove swamp ecological zone. In these regions of Nigeria, the rainy season is from March to November, which usually coincides with peak malaria incidence. The 2018 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) reported that malaria prevalence in children aged 6–59 months according to rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) was 49.3% in Ebonyi and 26.4% in Cross River [17]. In the year prior to the two ITN campaigns, among households with at least one ITN, 80.8% of household members slept under an ITN the previous night in Ebonyi and 65.9% slept under a net in Cross River [17]. In the 2021 Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS), this percentage decreased to 66.0% in Ebonyi and 51.6% in Cross River [18]. The primary malaria vectors throughout Nigeria are part of the An. gambiae species complex, with An. gambiae sensu stricto (s.s.) being the most predominant [19].

Intervention

Based on entomological evidence collected prior to the ITN campaigns between 2017 and 2019, [15, 16, 19] 1.7 million PBO ITNs (PermaNet 3.0; deltamethrin + PBO) were distributed in Ebonyi in November 2019. In Cross River, 2.3 million standard ITNs (Dawa Plus 2.0; deltamethrin only) were distributed in June 2019. Prior to the 2019 campaigns, the most recent ITN mass campaigns occurred in September 2015, when standard ITNs (Dawa Plus 2.0; deltamethrin only) were distributed in both states. Insecticide resistance data by year and site from 2017 and 2021 are provided in Supplemental Tables 1–3.

Study design

A retrospective observational analysis was conducted to evaluate the epidemiological and entomological impact of PBO ITNs. Epidemiological analyses assessed the impact at the facility level by month in Ebonyi and Cross River in the two years before and after the November 2019 PBO ITN campaign (December 2017–November 2021) using routine facility surveillance data. Cross River was selected as the comparison group for these analyses as it is similar geographically to Ebonyi and was the only state in Nigeria that received standard ITNs during the same year. Entomological analyses used surveillance data collected at six sampling sites in three LGAs in Ebonyi during the high transmission season immediately before and after the ITN campaign (June–October 2019 and June–October 2020). Given that longitudinal entomological monitoring was not conducted in Cross River during the study period, no comparison group was available for the entomological analyses.

Health facility surveillance

The primary outcome of the epidemiological evaluation was monthly malaria case incidence, defined as the number of confirmed malaria cases (confirmed by either microscopy or rapid diagnostic tests, RDT) per 1000 population. Data on confirmed malaria cases by month for each facility in Ebonyi and Cross River were extracted from the National Health Management Information System (NHMIS), stored in the District Health Information System, Version 2 (DHIS2). Completeness categories were calculated for each facility based on the number of months with data for each “evaluation year,” defined as December to November of the following year. Facilities were considered to have 100% confirmed case data for a given month if the number of confirmed cases was available and if no clinical cases were reported. Analysis was restricted to facilities with a minimum of data on confirmed cases for at least 9 out of the 12 months (75% completeness) for each of the four evaluation years. Health facility catchment populations were estimated based on gridded population estimates from 2019 using a statistical model as population estimates were not available in the NHMIS [20]. Additional information on health facility eligibility and the model used for estimating catchment areas are provided in Supplementary Information.

Vector surveillance

Two entomological outcome indicators analysed were human biting rate and indoor resting density. Human biting rate was defined as the number of An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes collected by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) light traps (LT) per person per night, which served as a proxy for human landing catch collections [21], disaggregated by indoor and outdoor collections. Indoor resting density was defined as the number of An. gambiae s.l. collected indoors by pyrethrum spray catch (PSC) per room per day. Vector surveillance was conducted at six sampling sites in three LGAs, two sites per LGA (Supplemental Table 4). Anopheles mosquitoes were collected monthly from each site during the high transmission season (June–October 2019 and June–October 2020) using human-baited CDC LTs and PSCs. For each month, field teams placed two human-baited CDC LTs—one indoors and one outdoors—at four houses per site for three nights, collecting hourly to measure mosquito biting. Indoor-resting mosquitoes were collected using PSCs in 32 houses per site per month. Teams followed standard operating procedures for CDC LT and PSC collections [22, 23]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were carried out on approximately 10% of the mosquitoes collected to identify members of the An. gambiae complex. The extracted DNA was amplified using the An. gambiae species-specific multiplex PCR [24, 25].

Model covariates

Climate data were extracted from publicly available satellite sources for each health facility catchment area and ward where vector surveillance was conducted, for each month of the evaluation period (December 2017 to November 2021). These data were incorporated into all statistical models and included: (1) average monthly precipitation from Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station (CHIRPS) data [26], (2) average monthly enhanced vegetation index (EVI) from the Famine Early Warning Systems Network [27], and (3) average monthly daytime temperature from the MODIS Land Surface Temperature and Emissivity [28].

Statistical analysis

Epidemiological impact model

For the epidemiological impact analysis, an interrupted time series approach with a comparison group was used to detect changes in the level and trend of malaria case incidence following each state’s respective ITN campaign. Monthly confirmed malaria cases for each eligible health facility were the primary outcome variable of the multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial model, with the natural log of the estimated facility catchment population included as an offset. Ward and health facility were included as random effects, with health facility nested within ward. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) method was used to determine which combination of lagged climate variables was the best fit. The final model included the following covariates: binary variable for before and after the ITN campaigns, binary variable for intervention group, time (months) since the start of the study, time (months) since the ITN campaigns, month fixed effects, precipitation lagged 1 month, EVI lagged 1 month, and daytime temperature lagged 2 months. The three climate covariates were scaled to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one.

The change in malaria case incidence for each state following the respective ITN campaign was calculated as the percent change between the number of cases estimated by the model during the post-intervention period and the estimated counterfactual, defined as the total number of expected cases in a scenario in which ITNs were not distributed. The number of cases averted was defined as the difference between these two values. For Ebonyi, the percent change in malaria case incidence was also calculated based on a counterfactual scenario in which standard ITNs were distributed, based on the model results for Cross River. Bootstrap confidence intervals were estimated by resampling the data at the ward level 1000 times and refitting the model to estimate the number of cases averted for each simulated dataset [29, 30]. Statistical significance was determined using the outputs of bootstrap analyses based on the proportion of bootstrap simulations in which the estimated cases averted crossed zero.

Entomological impact model

For the entomological analysis, two negative binomial models were constructed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) for the two outcome variables of interest: human biting rate and indoor resting density. The models used the total number of An. gambiae s.l. collected (from CDC LTs for biting rates and PSC for indoor resting density) as the dependent variable, with the number of collection nights for each month used as an offset. The best fit models were selected using the quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion (QIC) method, a modification of the AIC method used above that was developed for GEE model selection [31]. Both models included a binary variable for before and after the PBO ITN campaign in Ebonyi and a categorical variable for LGA as fixed effects. The model for human biting rate also included collection location (indoor/outdoor), precipitation lagged 1 month, EVI lagged 2 months, and daytime temperature lagged 2 months. The model for indoor resting density included precipitation lagged 1 month, EVI lagged 2 months, and daytime temperature lagged 1 month. The three climate covariates in each model were scaled to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one.

Data cleaning and transformation, as well as model fitting and simulations, were conducted using Stata SE 17 (© StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Data were visualized using R version 4.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Tableau (©Tableau Software, Seattle, WA, USA).

Results

Epidemiological impact outcomes

Descriptive analysis

Between December 2017 and November 2021, a total of 1653 health facilities were identified as active (Supplemental Fig. 1), of which 675 (40.8%) met the eligibility criteria for data completeness by having data on malaria cases for at least nine months of each evaluation year. Of these, 383 facilities (56.7%) were in Cross River and 292 (43.3%) were in Ebonyi. These facilities accounted for 579,261 cases out of all 976,958 cases reported (59.3%) during the 48 month period in Cross River and 1,438,084 cases out of all 1,835,786 cases reported (78.4%) in Ebonyi.

Annual observed malaria case incidence was higher in Ebonyi than in Cross River for each year of the evaluation (Table 1). Incidence rates increased in both states between the two years pre-distribution (December 2017–November 2018 to December 2018–November 2019); however, during the first year post-distribution (December 2019–November 2020), incidence declined in Ebonyi but increased in Cross River. Declines were seen in both states between the two post-distribution years (December 2019–November 2020 to December 2020–November 2021). Overall, the observed malaria case incidence declined 22.9% between the pre- and post-distribution periods in Ebonyi (from 180.6 malaria cases per 1000 population to 139.2) and increased 22.5% in Cross River (from 72.8 malaria cases per 1000 population to 89.2).

Table 1.

Incidence per 1000 population by evaluation year in Ebonyi and Cross River

| Evaluation Year | Ebonyi | Cross river |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-distribution (average) | 180.6 | 72.8 |

|

Pre-distribution year 1 (December 2017–November 2018) |

156.9 | 68.7 |

|

Pre-distribution year 2 (December 2018–November 2019) |

203.6 | 87.4 |

| Post-distribution (average) | 139.2 | 89.2 |

|

Post-distribution year 1 (December 2019–November 2020) |

175.5 | 92.3 |

|

Post -distribution year 2 (December 2020–November 2021) |

111.3 | 82.5 |

Case incidence is presented for the two years before and two years after the November 2019 PBO ITN campaign in both states. Values in bold indicate the average incidence rate for the entire pre- or post-distribution periods

Impact of ITN campaigns on malaria case incidence

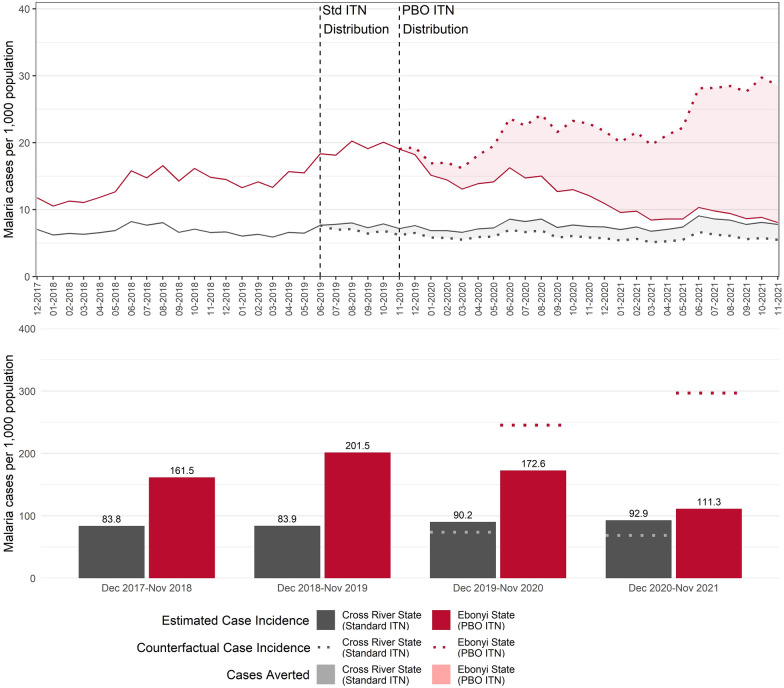

Using the interrupted time series model outputs, further analyses were conducted to estimate the number of cases averted in the event that no ITNs were distributed in either state in 2019, as well as the estimated percent change (Fig. 2). In Ebonyi, there was a statistically significant 46.7% decrease (95%CI: -51.5, -40.8%; p < 0.001) in malaria case incidence in the period after the PBO ITN distribution compared to if no ITNs had been distributed, from 269.6 predicted cases per 1000 population to 143.6 cases (p < 0.001). An estimated 560,074 cases were averted in Ebonyi among facilities included in the analyses. Most of these (69.6% of all estimated cases averted) were averted in the second year (13 to 24 months) after the PBO ITN campaign. In Cross River, there was a 28.6% increase (95%CI: -10.4, 49.1%; p < 0.001) in malaria case incidence following the standard ITN distribution compared to if no ITNs had been distributed, from 72.8 predicted cases per 1000 population to 91.6. Model results from Cross River were used to estimate the number of cases averted in a counterfactual scenario in which Ebonyi received standard ITNs rather than PBO ITNs. In this scenario, malaria case incidence in Ebonyi was 57.1% lower (95%CI: -63.2%, -49.5%; p < 0.001) following the PBO ITN campaign compared to if standard ITNs were deployed, averting an estimated 849,214 cases. The full table of multivariate incidence rate ratios for the model are presented in Table 2 Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted by different reporting completeness groups, with similar decreases observed in Ebonyi and increases observed in Cross River. Results from these sensitivity analyses are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Fig. 2.

Monthly incidence per 1000 population in Ebonyi and Cross River states, December 2017–November 2021. Monthly confirmed malaria case incidence rates are presented for the two years before and after the 2019 Ebonyi PBO ITN campaign with counterfactual of no ITN distribution. The top graph represents the monthly all-ages confirmed malaria cases per 1000 population. Vertical dashed lines indicate the ITN campaigns in Cross River (June 2019) and Ebonyi (November 2019). Solid lines represent modelled predictions from the interrupted time series model and points represent the observed values reported in the NHMIS. Dashed lines show the predicted number of cases in each state had no ITN campaign occurred. The shading for each state indicates the difference between the model estimates and the counterfactual. The bottom graph shows the modelled annualized case incidence per 1000 for each evaluation year (December to the following November) for both Cross River and Ebonyi. The dotted lines represent the counterfactual rate during the post-intervention period had no ITNs been distributed

Table 2.

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) for population-adjusted confirmed malaria cases in Cross River and Ebonyi states

| IRR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross River | |||

| Slope prior to the ITN distribution | 0.99 | (0.99–1.00) | 0.08 |

| Change in level following ITN distribution | 1.12 | (1.04–1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Difference in slopes pre- and post-ITN distribution | 1.01 | (1.00–1.02) | 0.04 |

| Ebonyi | |||

| Slope prior to the ITN distribution | 1.02 | (1.01–1.02) | < 0.001 |

| Change in level following ITN distribution | 0.94 | (0.88–1.01) | 0.11 |

| Difference in slopes pre- and post-ITN distribution | 0.95 | (0.94–0.96) | < 0.001 |

| Differences between Cross River and Ebonyi | |||

| Difference in the level between Cross River and Ebonyi prior to ITN distribution | 1.81 | (1.55–2.12) | < 0.001 |

| Difference in the slope between Cross River and Ebonyi prior to intervention | 1.02 | (1.02–1.03) | < 0.001 |

| Difference in the level between Cross River and Ebonyi immediately following ITN distribution | 0.84 | (0.79–0.93) | 0.01 |

| Difference between Cross River and Ebonyi in the slope after ITN distribution compared to pre-distribution | 0.94 | (0.92–0.95) | < 0.001 |

| Rainfall (lagged 1 month) | 1.04 | (1.02–1.05) | < 0.001 |

| EVI (lagged 1 month) | 1.04 | (1.02–1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Daytime temperature (lagged 2 months) | 0.96 | (0.94–0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Month | |||

| January | Ref. | ||

| February | 1.07 | (1.04–1.10) | < 0.001 |

| March | 1.00 | (0.97–1.03) | 0.91 |

| April | 1.05 | (1.01–1.09) | 0.01 |

| May | 1.04 | (0.99–1.09) | 0.08 |

| June | 1.20 | (1.14–1.27) | < 0.001 |

| July | 1.09 | (1.04–1.15) | < 0.001 |

| August | 1.09 | (1.05–1.14) | < 0.001 |

| September | 0.98 | (0.94–1.02) | 0.32 |

| October | 1.02 | (0.98–1.07) | 0.35 |

| November | 0.95 | (0.91–0.99) | 0.03 |

| December | 1.03 | (1.00–1.07) | 0.05 |

Entomological impact

Descriptive analysis

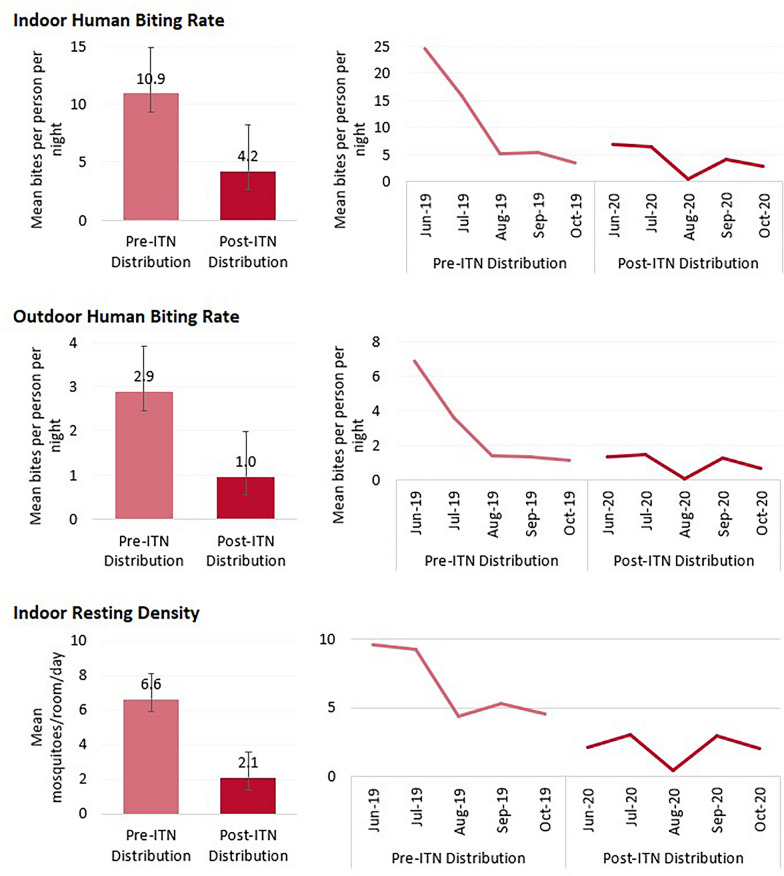

During the two high transmission seasons (June–October 2019 and June–October 2020), 22,271 mosquitoes were collected by either CDC LT or PSC at the six sampling sites in Ebonyi. Of these, 68.7% were Anopheles mosquitoes and 30.4% were culicine mosquitoes. Of the 15,492 Anopheles mosquitoes collected, nearly all were An. gambiae s.l. (98.8%). Results from the PCR assays indicated that, of the 1,071 An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes identified, 79.4% were An. gambiae s.s., 19.4% were Anopheles coluzzii, and 0.8% were Anopheles arabiensis. Between June and October 2019, the indoor biting rate of An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes was 10.9 bites per person per night (b/p/n), and the outdoor biting rate was 2.9 b/p/n, before dropping to 4.2 b/p/n and 1.0 b/p/n, respectively, between June and October 2020 (Fig. 3). Indoor and outdoor biting rates were highest in June 2019, before steadily dropping prior to the PBO ITN distribution in November 2019. Slight increases in both indoor and outdoor biting rates were seen between June and July 2020 and again in September 2020, although these increases were not as high as the same months during the previous year. As with the indoor and outdoor biting rates, indoor resting density decreased between the 2019 and 2020 high transmission seasons. The average number of An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes per room per day decreased from 6.6 mosquitoes per room per day between June to October 2019 to 2.1 during the same period in the following year. Monthly trends for indoor resting density were also similar to monthly trends in the human biting rate, with the highest rates seen at the start of the study period between June and July 2019.

Fig. 3.

Biting rates and indoor resting density among An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes during the 2019 and 2020 high transmission seasons, Ebonyi

Impact of ITN campaigns on entomological indicators

Model results from the pre-post analysis in Ebonyi from the six sampling sites found that biting rates during the high transmission season were 72% lower after the PBO ITNs were distributed compared to the pre-distribution period (IRR: 0.28; 95%CI: 0.21, 0.39; p < 0.001), with a decrease from 8.4 b/p/n to 2.6 (Table 3). Indoor resting density was also significantly lower during the high transmission season following the PBO ITN distribution in Ebonyi, with the model indicating that rates were 73% lower in the post-distribution period compared to the pre-distribution period (IRR: 0.27; 95%CI: 0.21, 0.35; p < 0.001), a decrease from 7.7 mosquitoes per room per day to 2.1 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) for human biting rate in Ebonyi

| IRR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention timing | |||

| Pre-PBO ITN campaign | Ref. | ||

| Post-PBO ITN campaign | 0.28 | (0.21–0.39) | < 0.001 |

| Collection method | |||

| Outdoor CDC-LT | Ref. | ||

| Indoor CDC-LT | 3.91 | (2.50–6.12) | < 0.001 |

| Local Government Area (LGA) | |||

| Ezza North | Ref. | ||

| Izzi | 0.50 | (0.28–0.91) | 0.02 |

| Ohaukwu | 1.03 | (0.60–1.77) | 0.92 |

| Rainfall (lagged 1 month) | 0.42 | (0.37–0.47) | < 0.001 |

| EVI (lagged 2 months) | 0.60 | (0.0–0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Temperature (lagged 2 months) | 1.10 | (1.02–1.18) | 0.01 |

Analyses were based on data from entomological collections during the high transmission season immediately before and after the PBO ITN campaign (June–October 2019 and June–October 2020)

Table 4.

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) for indoor resting density in Ebonyi

| IRR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention timing | |||

| Pre-PBO ITN campaign | Ref. | ||

| Post-PBO ITN campaign | 0.27 | (0.21–0.35) | < 0.001 |

| Local government area | |||

| Ezza North | Ref. | ||

| Izzi | 0.47 | (0.31–0.63) | < 0.001 |

| Ohaukwu | 0.44 | (0.45–0.70) | < 0.001 |

| Rainfall (lagged 1 month) | 0.56 | (0.45–0.70) | < 0.001 |

| EVI (lagged 2 months) | 0.82 | (0.73–0.93) | < 0.001 |

| Temperature (lagged 1 month) | 0.95 | (0.86–1.05) | 0.30 |

Analyses were based on data from entomological collections during the high transmission season immediately before and after the PBO ITN campaign (June–October 2019 and June–October 2020)

Discussion

This evaluation assessed the impact of PBO ITNs in a setting with widespread resistance to pyrethroids and standard ITNs in a setting where mosquitoes are still susceptible to deltamethrin and alpha-cypermethrin. Results from the interrupted time series analysis used for this evaluation indicated that there was a significant epidemiological impact of the PBO ITN campaign in Ebonyi compared to both counterfactual scenarios (no ITNs and standard ITNs) examined. This positive impact was not observed in Cross River where standard ITNs were distributed, with an observed increase in estimated cases compared to if no ITNs were distributed. Results from the entomological analyses found that during the high transmission season immediately following the PBO ITN campaign in Ebonyi, the human biting rate was 72% lower and indoor resting density was 73% lower compared to the high transmission season immediately before the campaign.

It was expected that these two types of ITNs would have a similar epidemiological impact in each state due to the targeting based on mosquito resistance profiles. However, the results found that only PBO ITNs were effective at reducing malaria incidence. One reason could be that pyrethroid resistance may exist in other settings in Cross River where data were not collected, thus minimizing the state-level impact of standard ITNs. Additionally, it has been documented that PBO ITNs contain higher pyrethroid levels compared to standard ITNs [13], which may have increased the efficacy of the pyrethroid active ingredient in Ebonyi. Finally, the overall higher malaria burden in Ebonyi during the pre-distribution period may have provided an opportunity to observe a greater decline.

To date, this is one of the first studies in Nigeria to evaluate the epidemiological and entomological impacts of a newer type of ITN. The positive epidemiological impact of PBO ITNs is similar to findings from previous assessments. In Tanzania, PBO ITNs reduced malaria prevalence by 44% after the first year and by 33% after the second year [11], and in Uganda, prevalence decreased by 27% after 18 months [12]. The trends observed in both Ebonyi and Cross River are also similar to those reported between the 2018 DHS [17] and the 2021 MIS [18]. In Ebonyi, malaria prevalence, according to RDT results for children under five years of age, decreased by 39% between the 2018 DHS and 2021 MIS, and malaria prevalence according to microscopy declined by 16%. In Cross River, malaria prevalence by RDT increased by 54% and malaria prevalence by microscopy increased by 21%. Positive impacts of PBO ITNs were also observed for the entomological indicators measured. Although this study was unable to compare the entomological impact of the PBO ITNs to the impact of standard ITNs, our positive results are similar to results reported in previous studies. A 2021 Cochrane review reported that a positive entomological impact of PBO ITNs was demonstrated on mosquito population density, and that this impact was greater than the impact of standard pyrethroid-only ITNs [13].

Of the estimated 560,074 malaria cases averted, most occurred in the second year after the PBO ITN campaign, indicating the efficacy of the PBO ITNs was retained over the study period. This finding differs from previous studies that have raised concerns over the long-term effectiveness of the PBO ITNs. Findings from Malawi suggest that neither PBO nor standard ITNs retained effectiveness for two high transmission seasons post-campaign [10], and a study in Tanzania found that while PBO ITNs were more effective than standard ITNs at reducing malaria prevalence, this impact was limited to 12 months [11].

The results from this epidemiological and entomological analyses contribute to a set of ongoing evaluations designed to assess the impact of new types of ITNs in Nigeria [32]. The other analyses, conducted by the New Nets Project, will also use NHMIS data to assess the impact on malaria case incidence, enabling direct comparisons between the findings of this study, and more rigorous quasi-experimental methods using cross-sectional surveys. Collectively, results from these evaluations will provide critical evidence to inform the NMEP’s stratification and planning for future ITN campaigns to ensure that the most effective nets are selected.

While the results from this evaluation are encouraging and can be used as one factor in the decision-making matrix, this evaluation does have limitations. First, it examined the impact on malaria case incidence between PBO ITNs in a setting with high malaria case incidence compared to the impact of standard ITNs in a setting with lower malaria case incidence. A more suitable comparison group with similar rates of malaria case incidence that received standard ITNs was not available. Results from the standard ITN counterfactual for Ebonyi should be interpreted with caution given the noted pre-intervention differences between these two states. Although possible, it is unlikely that the increase in malaria case incidence under the standard ITN counterfactual would be greater than under the no-ITN counterfactual. Any ITN, regardless of type, would still provide a physical barrier between household members and mosquitoes. For Cross River, while these analyses found an increase in case incidence compared to the no-ITN counterfactual—as also indicated by the increase in malaria prevalence in the state between the 2018 DHS and 2021 MIS—future analyses would benefit from incorporating routine NHMIS data from states that did receive ITNs at the time that PBO ITNs were distributed in Ebonyi. Similarly, longitudinal entomological data were only collected in Ebonyi and thus no suitable comparison group was available to assess the impact on biting rate and indoor resting density in areas that received standard ITNs.

A second limitation was that this evaluation was conducted using routine data from the NHMIS, which limits the ability to assess the true impact on malaria case incidence at the community level. The 2018 DHS reported that among children under 5 years of age with a fever, 72.8% sought advice or treatment, with 42.5% seeking treatment in the private sector [17]. The 2021 MIS, which was conducted the month immediately after the end of this evaluation period, found that 62.8% of febrile children under five sought advice or treatment, with 19.7% seeking treatment in the private sector. Within Nigeria, as in many countries, reporting from private sector facilities to the NHMIS has been limited. The NMEP is actively working with key stakeholders on improving this reporting with the goal to have at least 80% of health facilities (both public and private) reporting malaria data to the NHMIS by 2025 [33].

Additionally, the lack of data completeness for many facilities (65.4% of active facilities in Cross River and 54.0% in Ebonyi) further limited the number of facilities that could be reasonably included in the analysis without compromising the quality of the data. To address these concerns, the decision was made to only include those facilities with data for at least 9 out of the 12 months for each evaluation year. Since the analysis was restricted to a subset of facilities, and because the DHIS2 does not capture all facilities or all cases, it is likely that averted cases were underestimated in Ebonyi. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for all completeness groups, finding a significant impact of the PBO ITNs among all groups (see Supplementary Information).

Finally, this evaluation was unable to control for ITN use as monthly, facility-level data were not available. According to the 2018 DHS, among households with at least one ITN, 80.8% of household members slept under an ITN the previous night in Ebonyi and 65.9% slept under the net in Cross River [17]. In the 2021 MIS, this percentage decreased to 66.0% in Ebonyi and 51.6% in Cross River [18]. The difference in ITN use between the two states could partially explain the difference in impact between the two states but could not be accounted for in these analyses.

Conclusion

Trends in malaria case incidence and key entomological indicators show a positive impact of the 2019 PBO ITN campaign in Ebonyi, an area with confirmed pyrethroid resistance in An. gambiae s.l. There was no effect of standard ITNs in Cross River, an area with limited pyrethroid resistance. With an increase in resistance seen globally, these findings underline the impact that PBO ITNs can have in settings with widespread pyrethroid resistance and contribute to the larger body of ongoing research being conducted in Nigeria on the impact of new types of ITNs to decrease malaria burden.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Ebonyi State Ministry of Health and Ebonyi State University for their support on this project. We thank the USAID Global Health Supply Chain-Procurement and Supply Management (GHSC-PSM) for providing the ITN distribution and microplanning data, Erkwagh Dagba for his guidance and support in data analysis, John Aponte for his contributions to the statistical analyses, and Natalie Galles for her support on the data visualizations. We would like to expressly thank all the partners of the PMI VectorLink Project in Nigeria for their support and contributions.

Abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- b/p/n

Bites per person per night

- CDC LT

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention light trap

- CHIRPS

Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station

- DHIS2

District Health Information System, Version 2

- DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

- EVI

Enhanced vegetation index

- GEE

Generalized estimating equations

- IRR

Incidence rate ratio

- ITNs

Insecticide-treated nets

- LGA

Local government area

- MIS

Malaria indicator survey

- NHMIS

National Health Management Information System

- NMEP

National Malaria Elimination Programme

- PBO

Piperonyl butoxide

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PSC

Pyrethrum spray catch

- QIC

Quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion

- RDT

Rapid diagnostic test

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

ML, UI and MM conceived and designed the study. AO, PI, and CU oversaw programmatic activities, including supervising entomological data collection. KD drafted the manuscript with input from OO. KD analyzed the data with support from DR and CC on the statistical analyses and interpretation of the results. JM provided the population estimate and climate data for each facility catchment area. SB, OO, PU, AO, PI, CU, KA, AS, DR, CC, JM, ML UI, MM, JR and MY critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by USAID through the US President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or PMI.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study can be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/20/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s12936-024-05168-7

References

- 1.Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodiumfalciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015;526:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. World Malaria Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. p. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative. Nigeria Malaria Profile. 2023.

- 4.U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative. Nigeria—Malaria Operational Plan FY 2019.

- 5.Awolola TS, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Coetze M. Resistance of the malaria vector Anophelesgambiae s.s. to pyrethroid insecticides, in south-western Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96:849–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awolola TS, Oduola OA, Strode C, Koekemoer LL, Brooke B, Ranson H. Evidence of multiple pyrethroid resistance mechanisms in the malaria vector Anophelesgambiaesensu stricto from Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chukwuekezie O, Nwosu E, Nwangwu U, Dogunro F, Onwude C, Agashi N, et al. Resistance status of Anophelesgambiae (s.l.) to four commonly used insecticides for malaria vector control in South-East Nigeria. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PMI Technical Guidance FY 2022.

- 9.WHO. Guidelines for Malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. p. 396. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topazian HM, Gumbo A, Brandt K, Kayange M, Smith JS, Edwards JK, et al. Effectiveness of a national mass distribution campaign of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying on clinical malaria in Malawi, 2018–2020. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6: e005447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Protopopoff N, Mosha JF, Lukole E, Charlwood JD, Wright A, Mwalimu CD, et al. Effectiveness of a long-lasting piperonyl butoxide-treated insecticidal net and indoor residual spray interventions, separately and together, against malaria transmitted by pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes: a cluster, randomised controlled, two-by-two factorial design trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1577–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staedke SG, Gonahasa S, Dorsey G, Kamya MR, Maiteki-Sebuguzi C, Lynd A, et al. Effect of long-lasting insecticidal nets with and without piperonyl butoxide on malaria indicators in Uganda (LLINEUP): a pragmatic, cluster-randomised trial embedded in a national LLIN distribution campaign. Lancet. 2020;395:1292–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleave K, Lissenden N, Chaplin M, Choi L, Ranson H. Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) combined with pyrethroids in insecticide-treated nets to prevent malaria in Africa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021:CD012776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. High burden to high impact: a targeted malaria response [Internet]. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2018. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-CDS-GMP-2018.25

- 15.PMI VectorLink Project. The PMI VectorLink Nigeria Annual Entomology Report, November 2018–September 2019. USA: Rockville; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.PMI VectorLink Project. The PMI VectorLink Nigeria Annual Entomology Report, October 2019–September 2020. USA: Rockville; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Population Commission, ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, USA; 2019.

- 18.National Malaria Elimination Programme. Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey 2021 Final Report. Abuja, Nigeria, 2022.

- 19.PMI Africa IRS (AIRS) Project. AIRS Nigeria Final Entomology Report January—December 2017. Rockville, USA, 2018.

- 20.GRID3. GRID3 Nigeria Gridded Population Estimates, Version 2.0. 2021. https://data.grid3.org/maps/GRID3::grid3-nigeria-gridded-population-estimates-version-2-0/about

- 21.Kilama M, Smith DL, Hutchinson R, Kigozi R, Yeka A, Lavoy G, et al. Estimating the annual entomological inoculation rate for Plasmodium falciparum transmitted by Anophelesgambiae sl using three sampling methods in three sites in Uganda. Malar J. 2014;13:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.PMI VectorLink Project. SOP 01/01: Indoor and Outdoor CDC Light Trap Collections. 2019. https://tinyurl.com/us5p6mxm

- 23.PMI VectorLink Project. SOP 03/01: Pyrethrum Spray Catch. 2019. https://tinyurl.com/us5p6mxm

- 24.Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanello C, Santolamazza F, Della TA. Simultaneous identification of species and molecular forms of the Anophelesgambiae complex by PCR-RFLP. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:461–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CHIRPS: Rainfall Estimates from Rain Gauge and Satellite Observations. Climate Hazards Center—UC Santa Barbara. https://www.chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps

- 27.Famine Early Warning Systems Network. https://fews.net/

- 28.MODIS Web. https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/

- 29.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap(Monographs on statistics and applied probability). New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carpenter J, Bithell J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000;19:1141–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui J. QIC program and model selection in GEE analyses. Stata J Promot Commun Statist Stata. 2007. 10.1177/1536867X0700700205. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gansané A, Candrinho B, Mbituyumuremyi A, Uhomoibhi P, et al. Design and methods for a quasi-experimental pilot study to evaluate the impact of dual active ingredient insecticide-treated nets on malaria burden in five regions in sub-Saharan Africa. Malar J. 2022;21:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Malaria Elimination Programme. National Malaria Strategic Plan, 2021–2025. Abuja, Nigeria; 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study can be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.