Abstract

Purpose

Several lung function endpoints are utilized in clinical trials of inhaled bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Trough forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is a commonly reported endpoint in COPD trials and can be complemented by area under the FEV1 vs time curve (FEV1 AUC), which provides information on duration and consistency of bronchodilation over a dosing interval. Revefenacin, a once-daily bronchodilator, significantly improved lung function in patients with COPD when measured by trough FEV1 in two replicate Phase 3 trials. Here, we report an FEV1 AUC substudy using data from these trials.

Patients and Methods

This post hoc analysis examined substudy data from 12-week replicate Phase 3 trials (NCT02459080/NCT02512510); patients with moderate to very severe COPD were randomized 1:1 to revefenacin 175 μg or placebo once daily. The substudy patients had FEV1 AUC0–2h assessed on Day 1, and those who continued to Day 84 also underwent 24-hour serial spirometry postdose where FEV1 AUC0–2h, AUC0–12h, AUC12-24h, and AUC0–24h were evaluated.

Results

Fifty and 47 patients who received revefenacin and placebo underwent 24-hour serial spirometry; most baseline characteristics were aligned between groups. At Day 84 postdose, revefenacin demonstrated sustained improvements in bronchodilation over 24 hours; differences in least squares mean vs placebo were 282, 220, 205, and 212 mL for FEV1 AUC0–2h, AUC0–12h, AUC12–24h, and AUC0–24h (all P <0.001), respectively.

Conclusion

This substudy analysis supplements previous findings that revefenacin provides sustained bronchodilation over 24 hours. Assessing additional complementary COPD clinical trial endpoints can help clinicians make treatment decisions.

Keywords: Bronchodilators, long-acting muscarinic antagonist, outcome measures, spirometry, forced expiratory volume in 1 second

Introduction

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) rely on bronchodilation to relieve their symptoms of dyspnea, cough, and mucus hypersecretion and to improve lung function.1–4 In addition to smoking cessation, long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and/or long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) bronchodilators administered alone or in combination, with or without inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), are important treatment options for patients with COPD.3,5,6

Historically, a majority of clinical trials in COPD examining long-acting bronchodilator therapies have used trough forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as the primary efficacy endpoint when assessing lung function.7–10 Other endpoints, such as area under the FEV1 vs time curve (FEV1 AUC) and peak FEV1, are typically included as secondary or exploratory endpoints. For example, all Phase 3 trials assessing once-daily LAMAs for the treatment of COPD have reported trough FEV1 as a lung function primary endpoint,11–13 while FEV1 AUC has been reported as a secondary or exploratory endpoint in a limited number of other Phase 3 trials.14–20 While no minimal clinically important difference (MCID) has been established for FEV1 AUC over any particular interval postdose, the MCID for trough FEV1 is defined as 100 mL by the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society guidelines.8,21,22 The effect of treatment on trough FEV1 is assumed to be at its nadir immediately before the next dose. When the trough FEV1 exceeds the MCID, it is inferred that the effect is greater than that threshold throughout the entire dosing period. FEV1 AUC can provide supplemental information on the magnitude of a response over a wider dosing interval vs trough FEV1 (and therefore may be less sensitive to outliers compared with other measures of lung function).23 Therefore, the combination of lung function endpoints is valuable to comprehensively assess the extent of bronchodilation over the interval between doses.

Revefenacin is a novel, once-daily LAMA approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018 for the maintenance treatment of patients with COPD.1,24 In two replicate Phase 3 trials, revefenacin significantly improved trough FEV1 at Day 85 (Trial 0126: 146 mL and Trial 0127: 147 mL) and peak FEV1 (pooled across both trials: 130 mL) vs placebo (all P <0.001) in patients with moderate to very severe COPD.11 Furthermore, revefenacin improved health-related quality of life parameters in these patients.25 The safety profile of revefenacin may be attributed to its lung selectivity, as well as minimal systemic drug exposure.1,26 Revefenacin Phase 3 FEV1 AUC data have not been reported previously given the strong trough FEV1 values observed in the Phase 3 trial program.11,27 The purpose of this post hoc analysis is to report FEV1 AUC revefenacin data from the two replicate Phase 3 trials to more fully define its 24-hour bronchodilatory profile.

Material and Methods

Analysis Design and Patient Population

This post hoc analysis examined data from two 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled replicate Phase 3 trials (Trials 0126 [NCT02459080] and 0127 [NCT02512510]).11 Detailed methods of these trials have been published previously.11 Briefly, these trials included adults ≥40 years old with documented moderate to very severe COPD, who had a current or past smoking history of ≥10 pack-years, and were randomized 1:1:1 to receive revefenacin 88 μg, revefenacin 175 μg, or placebo administered once daily in the morning by a standard jet nebulizer (PARI LC Sprint) for 12 weeks.11 The prespecified primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in trough FEV1 on Day 85.11 Peak FEV1 on Day 1 was a secondary endpoint11 and FEV1 AUC from 0 to 2 hours (FEV1 AUC0–2h) on Days 1, 15, 29, 57, and 84 was a prespecified exploratory endpoint. While both revefenacin 88 μg and 175 μg doses were investigated in these trials, the post hoc analysis reported herein focused only on the 175 μg dose as this is the dose approved by the FDA.24

On Day 84, a subgroup of patients at preselected sites underwent 24-hour serial spirometry following the last dose of trial medication on Day 84 in addition to their standard assessments. Patients included in this substudy provided sufficient spirometry serial assessments for FEV1 AUC from 0 to 12 hours (FEV1 AUC0–12h) to be calculated. Most patients also provided sufficient assessments for FEV1 AUC from 12 to 24 hours (FEV1 AUC12–24h) and FEV1 AUC from 0 to 24 hours (FEV1 AUC0–24h) to be calculated.

Data Collection and Assessments

FEV1 was assessed by spirometry using a flow-volume loop for all respiratory flow measurements. Trough FEV1 and 0- to 2-hour postdose (peak) serial spirometry were conducted at Days 1, 15, 29, 57, and 84 (trough FEV1 was also assessed on Day 85). Serial spirometry over 24 hours in the subgroup of patients started on Day 84 postdose. In these patients, spirometry was performed at 45 and 15 minutes predose and at 5, 15, and 30 minutes, and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 21, 22, 23.25, and 23.75 hours postdose (the time window for spirometry was ±5 minutes for each nominal time point up to the 2-hour time point and a ±10 minute window for each of the later time points). Some patients were unable (based on advisement that it was clinically inappropriate) or unwilling to perform spirometry at every time point in the 24-hour period. Spirometry was performed according to techniques described in the Spirometry Manual, which reflects the ATS Guidelines for Spirometry.28 A central spirometry vendor (CompleWare Corporation) was used to provide standardized training on spirometry, qualification of the spirometry technician, and quality control of the spirometry throughout the trials. Serial FEV1 AUC data were collected separately from Trials 0126 and 0127 and then pooled together for this post hoc analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Spirometry endpoints were analyzed by fitting mixed-effects repeated-measures models (modeling details are provided in the Supplementary Materials). A patient must have had an available beginning, in-between, and end time point assessment for the calculation of AUCs (if any of these were missing, the AUC was set to missing). In addition, FEV1 AUC0–24h was set to missing if either FEV1 AUC0–12h or FEV1 AUC12–24h was missing. AUCs were calculated using the trapezoidal rule and converted to weighted means for analysis by dividing by interval duration (2, 12, or 24 hours). All statistical analyses were performed using base SAS software version 9.4 and SAS/STAT software version 15.1 (SAS Institute). P-values presented for these post hoc analyses were unadjusted for multiple testing and were nominal.

Results

Patient Population and Baseline Demographics and Characteristics

A total of 97 patients (50 who received revefenacin 175 μg and 47 who received placebo) from the 2 trials were included in the Day 84 24-hour serial spirometry substudy analysis set. Baseline demographics and characteristics of patients included in the substudy analysis set were similar and generally well balanced between the revefenacin and placebo arms (Table 1). Most common comorbid conditions included hypertension (60%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (53%), and depression (35%). The median number of years smoked was 41, and the median pack-years was 42. A higher proportion of patients who received revefenacin were male and were on a concurrent ICS/LABA regimen. ICS/LABA regimens included budesonide and formoterol fumarate, fluticasone propionate and salmeterol, mometasone furoate and formoterol fumarate, or fluticasone furoate and vilanterol, all at their FDA-approved doses. An ad hoc sensitivity analysis comparing FEV1 AUC results adjusted and not adjusted for sex and concurrent ICS/LABA showed that the net effect of these imbalances was minimal.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Revefenacin 175 μg (n = 50) |

Placebo (n = 47) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 (9) | 64 (8) |

| Male, n (%) | 26 (52) | 18 (38) |

| Race, White, n (%) | 42 (84) | 39 (83) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 (7) | 29 (7) |

| Current Smoker, n (%) | 24 (48) | 25 (53) |

| Pack-Years, median | 42 | 45 |

| Concurrent ICS/LABA Use, n (%) | 22 (44) | 11 (23) |

| Post-ipratropium % Predicted FEV1 | 56 (13) | 54 (12) |

| Post-ipratropium FEV1 to FVC Ratio | 0.53 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.10) |

| FEV1, L | 1.31 (0.45) | 1.25 (0.38) |

| Patients With mMRC ≥2, n (%) | 28 (56) | 26 (55) |

| Patients With CAT ≥10, n (%) | 45 (90) | 43 (91) |

| Exacerbations in the Prior Year, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 37 (74) | 34 (72) |

| 1 | 12 (24) | 10 (21) |

| ≥2 | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| GOLD Airflow Limit Category, n (%) | ||

| ≥50, <80% | 34 (68) | 32 (68) |

| ≥30%, <50% | 13 (26) | 14 (30) |

| <30% | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

Notes: Data are mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified. The substudy analysis set was defined as all patients for whom Day 84 weighted mean FEV1 0–12 hours could be calculated. GOLD airflow limit category is based on post-ipratropium % predicted FEV1.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta-agonist; mMRC, Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale.

Lung Function Efficacy

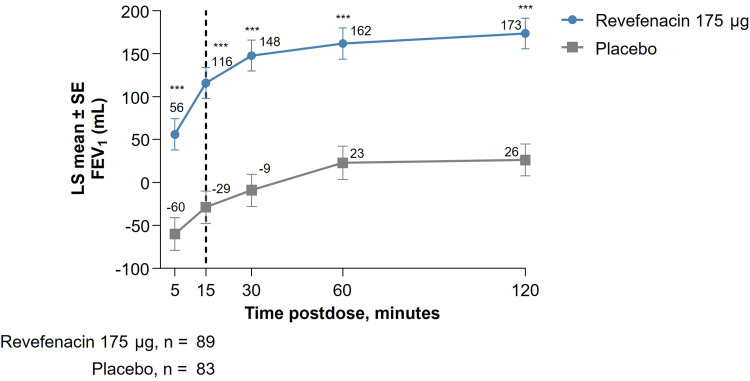

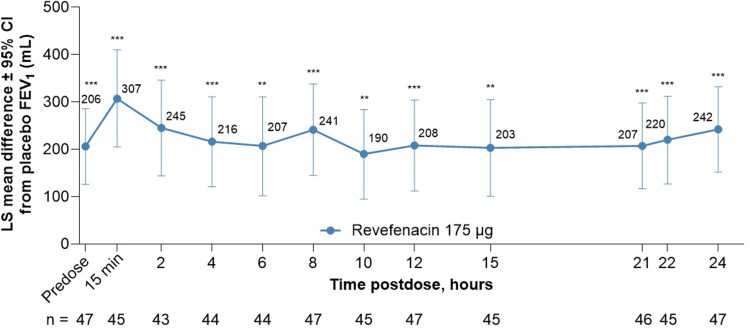

This post hoc analysis of pooled substudy data from Trials 0126 and 0127 showed that revefenacin improved lung function in patients with moderate to very severe COPD when assessed by FEV1 AUC. In these patients, bronchodilation onset with revefenacin was rapid with a least squares (LS) mean difference (95% confidence interval [CI]) of 145 mL (99, 191; P <0.001) between revefenacin 175 μg vs placebo at 15 minutes postdose on Day 1, and this difference was maintained through 2 hours postdose; Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). At Day 84, improvements in bronchodilation were sustained over 24 hours in the revefenacin treated arm vs placebo (Figure 2), with LS mean differences (95% CI) between revefenacin 175 μg vs placebo being 282 mL (181, 383) for FEV1 AUC0–2h, 220 mL (134, 305) for FEV1 AUC0–12h, 205 mL (119, 291) for FEV1 AUC12–24h, and 212 mL (129, 296) for FEV1 AUC0–24h (all P <0.001; Table 2). Differences in LS mean (95% CI) in trough and peak FEV1 at Day 84 between revefenacin 175 μg vs placebo were 197 (122, 273) mL and 264 (172, 355) mL (both P <0.001), respectively.

Figure 1.

Short-Term (0 to 2 Hours) Increase in FEV1 of Revefenacin at Day 1.

Notes: ***P<0.001 vs placebo. The vertical line signifies time point of bronchodilation onset with revefenacin. LS mean values at each time point are shown. The number of patients in each group at 15 minutes postdose is reported.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second; LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Figure 2.

LS Mean Difference of Revefenacin from Placebo in Serial Spirometry Over 24 Hours at Day 84.

Notes: ***P<0.0001 vs placebo. **P<0.001 vs placebo. LS mean differences from placebo values at each time point are shown.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second; LS, least squares; min, minute.

Table 2.

Weighted Mean FEV1 Lung Function Endpoints of Revefenacin from Placebo at Day 84

| Parameters | Revefenacin 175 μg | Placebo |

|---|---|---|

| FEV1 AUC0–2h (mL) | ||

| Evaluable n | 45 | 42 |

| LS Mean Difference (SE) | 282 (51) | – |

| 95% CI for LS Mean Difference (SE) | (181, 383) | – |

| P-value | <0.001 | – |

| FEV1 AUC0–12h (mL) | ||

| Evaluable n | 50 | 47 |

| LS Mean Difference (SE) | 220 (43) | – |

| 95% CI for LS Mean Difference (SE) | (134, 305) | – |

| P-value | <0.001 | – |

| FEV1 AUC12–24h (mL) | ||

| Evaluable n | 48 | 47 |

| LS Mean Difference (SE) | 205 (43) | – |

| 95% CI for LS Mean Difference (SE) | (119, 291) | – |

| P-value | <0.001 | – |

| FEV1 AUC0–24h (mL) | ||

| Evaluable n | 48 | 47 |

| LS Mean Difference (SE) | 212 (42) | – |

| 95% CI for LS Mean Difference (SE) | (129, 296) | – |

| P-value | <0.001 | – |

| Peak FEV1 0–2 hours (mL) | ||

| Evaluable n | 50 | 47 |

| LS Mean Difference (SE) | 264 (46) | – |

| 95% CI for LS Mean Difference (SE) | (172, 355) | – |

| P-value | <0.001 | – |

| Trough FEV1 (mL) | ||

| Evaluable n | 50 | 47 |

| LS Mean Difference (SE) | 197 (38) | – |

| 95% CI for LS Mean Difference (SE) | (122, 273) | – |

| P-value | <0.001 | – |

Notes: Evaluable n is the number of patients included in the analysis.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second; FEV1 AUC, area under the FEV1 vs time curve; FEV1 AUC0-2h, FEV1 AUC from 0 to 2 hours; FEV1 AUC0-12h, FEV1 AUC from 0 to 12 hours; FEV1 AUC0-24h, FEV1 AUC from 0 to 24 hours; FEV1 AUC12-24h, FEV1 AUC from 12 to 24 hours; LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Discussion

When assessing FEV1 AUC in this post hoc analysis from two Phase 3 trials where patients underwent 24-hour serial spirometry, sustained and robust bronchodilation at Day 84 was observed over 24 hours postdose in patients who received revefenacin, reflected by a FEV1 AUC0–24h LS mean difference vs placebo of 212 mL. Furthermore, improvements in lung function also favored revefenacin vs placebo when assessed by FEV1 AUC0–2h, AUC0–12h, and AUC12–24h, demonstrating that the action of revefenacin is persistent regardless of the observed time interval. In addition, within 15 minutes, revefenacin exhibited an effect on mean FEV1 which with approximately 97.5% confidence exceeded the MCID of 100 mL (LS mean difference vs placebo [95% CI] of 145 [99, 191] mL).8,21,22

FEV1 AUC is normalized as a time-adjusted calculation (ie, by dividing the observed FEV1 AUC value by the interval duration to obtain a time-normalized value).29,30 The time-adjustment enables a relative comparison of bronchodilator effect across various postdose intervals. In this analysis, the Day 84 LS mean FEV1 AUC0–12h, FEV1 AUC12–24h, and FEV1 AUC0–24h improvements for revefenacin over placebo were remarkably similar, demonstrating that the consistent and sustained effect revefenacin has during the daytime was carried over through the nighttime, and indeed over the full 24 hours postdose. In this manner, FEV1 AUC analyses have utility in describing the profile of long-acting bronchodilators. Indeed, when combined with the early and late assessments of peak and trough FEV1, respectively, a full-time profile of a bronchodilator’s effectiveness over the dosing interval is achieved. Thus, each of these lung function parameters play a role in the reporting of spirometry outcomes from bronchodilators in clinical trials.

According to the FDA, if the goal of a trial is to reduce airflow obstruction, the primary efficacy endpoint should be the change in postdose FEV1 for a bronchodilator.31 For bronchodilators, serial postdose FEV1 assessments should be performed to characterize a time profile curve to estimate the time to and duration of the effect.31 In this context, the FEV1 AUC measure would appear to have utility in characterizing the time-averaged patient response. Nevertheless, in recent Phase 3 registrational trials of new COPD agents, FEV1 AUC has been used less frequently than trough FEV1 as the primary efficacy endpoint.11,12,32 Trough FEV1, which measures the extent of bronchodilation at the end of the dosing period33 (ie, 24 hours for once-daily drugs and 12 hours for twice-daily drugs), is a highly sensitive measure of a drug’s duration, and has effectively distinguished agents appropriate for once-daily dosing vs those more suited for twice-daily administration (Table 3). A placebo-adjusted difference in trough FEV1 of 100 mL or greater vs baseline (predose) is considered an MCID.8,21,22 Changes in trough FEV1 of 100 mL have been correlated with fewer relapses following COPD exacerbations.8,21,22,34 Given the above guidance and findings, trough FEV1 became the primary lung function endpoint reported in long-acting bronchodilator clinical trials as this reflects lung function improvements over 12 to 24 hours as well as morning lung function when patients awaken.8

Table 3.

Lung Function Endpoints to Assess Bronchodilator Efficacy in COPD

| Endpoint | Description | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Peak FEV1 |

|

|

|

FEV1 AUC (General) |

|

|

| FEV1 AUC0–2h |

|

|

| FEV1 AUC0–12h |

|

|

| FEV1 AUC12–24h |

|

|

| FEV1 AUC0–24h |

|

|

| Trough FEV1 |

|

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1 AUC, area under the FEV1 vs time curve; MCID, minimal clinically important difference.

Despite the emergence of trough FEV1 as a predominant measure for bronchodilator effect, FEV1 AUC can still provide valuable complementary information as illustrated by revefenacin data in this post hoc analysis.6,8 Despite limitations, each time interval endpoint provides useful information regarding the effect profile (Table 3). Different measures of FEV1 can vary on the same day and be susceptible to diurnal changes (spirometry parameters tend to be lower in the morning vs evening).8,36,37 Assessing bronchodilation over a 24 hour period (FEV1 AUC0–24h) obviously aligns best with once-daily dosing, and assessments such as FEV1 AUC0–12h can examine daytime treatment effects. Therefore, with time averaging, this allows the comparison of effect from a once-daily drug dosed in the first part of the day vs the entire 24-hour period. Time averaging may also enable comparisons of drugs dosed once vs twice daily. Finally, FEV1 AUC12–24h can assess the efficacy of a drug dosed once daily during the nighttime period35 and show contrast to daytime FEV1 AUC0–12h.

A principal shortcoming of FEV1 AUC is the potential to mask drastic differences between peak and trough measurements. For example, similar FEV1 AUC0–12h values cannot distinguish between a modest yet consistent bronchodilation over a 12-hour interval vs a high peak-to-trough profile where a robust acute effect wanes to a low, clinically ineffective level at the 12-hour trough. This scenario supports the importance of reporting peak and trough FEV1 alongside FEV1 AUC values from bronchodilators in clinical trials. Each lung function endpoint has its own strengths and limitations. In practice, all of the above lung function parameters are recommended to assess a drug’s full bronchodilation profile. Therefore, it is recommended that clinicians utilize multiple lung function endpoints in order to better understand the potential bronchodilation of a patient during the dosing interval.

Limitations with this post hoc analysis should be noted. The principal limitation was the low number of patients who underwent serial spirometry in the substudy (approximately 50 per treatment group), yielding imprecise treatment effect estimates; nonetheless, the 95% CI lower limits exceeded 100 mL at 30 minutes and 2 hours postdose.

Conclusion

Revefenacin, an approved LAMA administered once daily for the maintenance treatment of moderate to very severe COPD, demonstrated robust, stable, and sustained improvements in lung function compared with placebo over 24 hours as measured by FEV1 AUC. These FEV1 AUC substudy results support previous peak and trough FEV1 findings11 indicating a consistent revefenacin response that was sustained for the entire 24-hour postdose period. Lung function endpoints used in clinical trials for COPD have their benefits and limitations. Combining peak and trough FEV1 with time-averaged FEV1 AUC measures from clinical trials allows for full profiling of a bronchodilator’s efficacy response. Clinicians should be aware of the information that each lung function endpoint is conveying, and that the synthesis of multiple lung function endpoints is optimal to assess the consistency of bronchodilation that a patient may receive.

Acknowledgments

All authors conform to the ICMJE guidelines for authorship and substantially participated in the creation of the submitted work. The authors would like to thank the patients, investigators, and site staff involved in the 24-hour serial spirometry substudy for making these analyses possible. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Gregory Suess, PhD, CMPP, of AlphaBioCom, a Red Nucleus company, and was funded by Theravance Biopharma US, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA and Viatris, Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA.

Funding Statement

Support for the development of this manuscript was funded by Theravance Biopharma US, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA and Viatris, Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA.

Abbreviations

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting beta-agonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1 AUC, area under the FEV1 vs time curve; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; ATS, American Thoracic Society; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; FEV1 AUC0-2h, FEV1 AUC from 0 to 2 hours; FEV1 AUC0-12h, FEV1 AUC from 0 to 12 hours; FEV1 AUC12-24h, FEV1 AUC from 12 to 24 hours; FEV1 AUC0-24h, FEV1 AUC from 0 to 24 hours; LS, least squares; CI, confidence interval; PRO, patient-reported outcome.

Data Sharing Statement

Theravance Biopharma (and its affiliates) will not be sharing individual deidentified patient data or other relevant trial data documents at this time.

Ethics Approval

All patients provided written informed consent and the protocol was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board (Quorum Review IRB, Seattle, Washington). This study was conducted according to the principles of Good Clinical Practice, following the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Guideline and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Corey J. Witenko is a current employee of Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. and owns stock. Melinda K. Lacy is a current employee of Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. and owns stock. Ann W. Olmsted is a paid consultant for Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. and owns stock. Edmund J. Moran is a current employee of Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. and owns stock. In addition, Edmund J. Moran has a patent US11484531 licensed to Viatris. Donald A. Mahler serves on the advisory boards of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Theravance, Verona, and Viatris and receives royalties from pharmaceutical companies (Elpen Pharmaceutical Company and University of Aberdeen) for the use of baseline dyspnea index/transition dyspnea index. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Donohue JF, Kerwin E, Sethi S, et al. Revefenacin, a once-daily, lung-selective, long-acting muscarinic antagonist for nebulized therapy: safety and tolerability results of a 52-week phase 3 trial in moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2019;153:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelmeier CF, Román-Rodríguez M, Singh D, Han MK, Rodríguez-Roisin R, Ferguson GT. Goals of COPD treatment: focus on symptoms and exacerbations. Respir Med. 2020;166:105938. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeh KM, Beier J. The short, the long and the “ultra-long”: why duration of bronchodilator action matters in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adv Ther Mar. 2010;27(3):150–159. doi: 10.1007/s12325-010-0017-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calzetta L, Ritondo BL, Zappa MC, et al. The impact of long-acting muscarinic antagonists on mucus hypersecretion and cough in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(164). doi: 10.1183/16000617.0196-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pezzuto A, Tonini G, Ciccozzi M, et al. Functional Benefit of Smoking Cessation and Triple Inhaler in Combustible Cigarette Smokers with Severe COPD: a Retrospective Study. J Clin Med. 2022;12(1). doi: 10.3390/jcm12010234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 update. Available from: www.goldcopd.org. Accessed July 2, 2024.

- 7.Rabe KF, Halpin DMG, Han MK, et al. Composite endpoints in COPD: clinically important deterioration in the UPLIFT trial. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01431-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohue JF. Minimal clinically important differences in COPD lung function. COPD. 2005;2(1):111–124. doi: 10.1081/copd-200053377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donohue JF, Jones PW, Bartels C, et al. Correlations between FEV1 and patient-reported outcomes: a pooled analysis of 23 clinical trials in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther Apr. 2018;49:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dankers M, Nelissen-Vrancken M, Surminski SMK, Lambooij AC, Schermer TR, van Dijk L. Healthcare professionals’ preferred efficacy endpoints and minimal clinically important differences in the assessment of new medicines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Pharmacol. 2020;10:1519. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson GT, Feldman G, Pudi KK, et al. Improvements in lung function with nebulized revefenacin in the treatment of patients with moderate to very severe COPD: results from two replicate Phase III clinical trials. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis Apr. 2019;6(2):154–165. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.6.2.2018.0152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi R, Richard N, Mehta R, Church A. Umeclidinium in patients with COPD: a randomised, placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):72–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00033213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelmeier C, Paggiaro PL, Dorca J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Aclidinium/formoterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone: a phase 3 COPD study. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(4):1030–1039. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00216-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman KR, Beeh KM, Beier J, et al. A blinded evaluation of the efficacy and safety of glycopyrronium, a once-daily long-acting muscarinic antagonist, versus tiotropium, in patients with COPD: the GLOW5 study. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones PW, Rennard SI, Agusti A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily Aclidinium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2011;12(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rennard SI, Scanlon PD, Ferguson GT, et al. ACCORD COPD II: a randomized clinical trial to evaluate the 12-week efficacy and safety of twice-daily Aclidinium bromide in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(12):893–904. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0138-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh D, Ferguson GT, Bolitschek J, et al. Tiotropium + olodaterol shows clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life. Respir Med. 2015;109(10):1312–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaForce C, Feldman G, Spangenthal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of twice-daily glycopyrrolate in patients with stable, symptomatic COPD with moderate-to-severe airflow limitation: the GEM1 study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1233–1243. doi: 10.2147/copd.S100445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones PW, Singh D, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy and safety of twice-daily Aclidinium bromide in COPD patients: the ATTAIN study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(4):830–836. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00225511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cazzola M, MacNee W, Martinez FJ, et al. Outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):416–469. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00099306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones PW, Beeh KM, Chapman KR, Decramer M, Mahler DA, Wedzicha JA. Minimal clinically important differences in pharmacological trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(3):250–255. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1863PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durr SM, Davis B, Gauvreau G, Cockcroft, D. Allergen bronchoprovocation: correlation between FEV(1) maximal percent fall and area under the FEV(1) curve and impact of allergen on recovery. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2023;19(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13223-023-00759-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.YUPELRI (revefenacin). Package Insert. Theravance Biopharma and Mylan Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donohue JF, Kerwin E, Barnes CN, Moran EJ, Haumann B, Crater GD. Efficacy of revefenacin, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist for nebulized therapy, in patients with markers of more severe COPD: a post hoc subgroup analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1156-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn D, Barnes CN, Yates W, et al. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety of revefenacin (TD-4208), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): results of two randomized, double-blind, Phase 2 studies. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donohue JF, Kerwin E, Sethi S, et al. Maintained therapeutic effect of revefenacin over 52 weeks in moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Res. 2019;20(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1187-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respir Health Spirometry Proc Manual. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.de la Loge C, Tugaut B, Fofana F, et al. Relationship between FEV(1) and patient-reported outcomes changes: results of a meta-analysis of randomized trials in stable COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016;3(2):519–538. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.3.2.2015.0152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beeh KM, Kirsten AM, Dusser D, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics following once-daily and twice-daily dosing of tiotropium respimat(®) in asthma using standardized sample-contamination avoidance. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2016;29(5):406–415. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2015.1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: developing drugs for treatment. 81 FR 31945. Nov 2007. Accessed 02 January 2024.

- 32.Bateman ED, Ferguson GT, Barnes N, et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 versus single bronchodilator therapy: the SHINE study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(6):1484–1494. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00200212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerstjens HA, Disse B, Schröder-Babo W, et al. Tiotropium improves lung function in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(2):308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann M, Meyer RJ. Drug development for asthma and COPD: a regulatory perspective. Respir Care. 2018;63(6):797–817. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beier J, Kirsten AM, Mróz R, et al. Efficacy and safety of Aclidinium bromide compared with placebo and tiotropium in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a 6-week, randomized, controlled phase IIIb study. COPD. 2013;10(4):511–522. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.814626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goel A, Goyal M, Singh R, Verma N, Tiwari S. Diurnal variation in peak expiratory flow and forced expiratory volume. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(10):Cc05–7. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2015/15156.6661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhee MH, Kim LJ. The changes of pulmonary function and pulmonary strength according to time of day: a preliminary study. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(1):19–21. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Theravance Biopharma (and its affiliates) will not be sharing individual deidentified patient data or other relevant trial data documents at this time.