Abstract

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 1 2008). Cancer‐related fatigue (CRF) is common, under‐recognised and difficult to treat. There have been studies looking at drug interventions to improve CRF but results have been conflicting depending on the population studied and outcome measures used. No previous reviews of this topic have been exhaustive or have synthesised all available data.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of drugs for the management of CRF.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (from Issue 2 2007) MEDLINE and EMBASE from January 2007 to October 2009 and a selection of cancer journals. We searched references of identified articles and contacted authors to obtain unreported data.

Selection criteria

Studies were included in the review if they 1) assessed drug therapy for the management of CRF compared to placebo, usual care or a non‐pharmacological intervention in 2) randomised controlled trials (RCT) of 3) adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of cancer.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Meta‐analyses were performed on different drug classes using continuous variable data.

Main results

Fifty studies met the inclusion criteria. Six additional studies were identified since the original review. Only 31 of these studies involving 7104 participants were judged to have used a sufficiently robust measure of fatigue and thus were deemed suitable for detailed analysis. The drugs were still analysed by class (psychostimulants; haemopoietic growth factors; antidepressants and progestational steroids). Methylphenidate showed a small but significant improvement in fatigue over placebo (Z = 2.83; P = 0.005). Since the publication of the original review increased safety concerns have been raised regarding erythropoietin and this cannot now be recommended in practice.There was a very high degree of statistical and clinical heterogeneity in the trials and the reasons for this are discussed.

Authors' conclusions

There is increasing evidence that psychostimulant trials provide evidence for improvement in CRF at a clinically meaningful level. There is still a requirement for a large scale RCT of methylphenidate to confirm the preliminary results from this review. There is new safety data which indicates that the haemopoietic growth factors are associated with increased adverse outcomes. These drugs can no longer be recommended in the treatment of CRF. Readers of the first review should re‐read the document in full.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Central Nervous System Stimulants, Central Nervous System Stimulants/therapeutic use, Darbepoetin alfa, Erythropoietin, Erythropoietin/adverse effects, Erythropoietin/analogs & derivatives, Erythropoietin/therapeutic use, Fatigue, Fatigue/drug therapy, Fatigue/etiology, Hematinics, Hematinics/adverse effects, Hematinics/therapeutic use, Methylphenidate, Methylphenidate/therapeutic use, Neoplasms, Neoplasms/complications, Progestins, Progestins/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Drugs for cancer‐related fatigue

Fatigue associated with cancer is a significant problem. It can occur because of side effects of treatment or because of the disease itself. It can have a significant impact on a person's ability to function. The causes of fatigue are not fully understood and so it is very difficult to treat appropriately. This review has examined drug treatment for fatigue as it represents one of the ways this problem can be tackled. The review authors looked at trials in all types of cancer and at all stages of treatment. Fifty studies met the inclusion criteria but only 31 (7104 participants) were deemed suitable for detailed analysis as they explored fatigue in sufficient detail. They found mixed results with some drugs showing an effect on fatigue ‐ most notably drugs that stimulate red blood cell production and also drugs that improve levels of concentration. Methylphenidate, a stimulant drug that improves concentration, is effective for the management of cancer‐related fatigue but the small samples used in the available studies mean more research is needed to confirm its role. Erythropoietin and darbopoetin, drugs that improve anaemia, are effective in the management of cancer‐related fatigue. However safety concerns and side effects from these drugs mean that they can no longer be recommended to treat cancer fatigue.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Psychostimulants versus placebo in the management of cancer‐related fatigue.

| Psychostimulants versus placebo in the management of cancer‐related fatigue. | ||||||

| Patient or population: Settings: Intervention: Psychostimulants versus placebo Comparison: the management of cancer‐related fatigue | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| the management of cancer‐related fatigue | Psychostimulants versus placebo | |||||

| Fatigue score change Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | The mean Fatigue score change in the intervention groups was 0.28 standard deviations lower (0.48 to 0.09 lower) | 410 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | SMD ‐0.28 (‐0.48 to ‐0.09) | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 1 2008) on drug therapy for the management of cancer‐related fatigue (Minton 2008). Cancer‐related Fatigue (CRF) is one of the most common symptoms experienced by cancer patients (Morrow 2002). It can be problematic at the time of diagnosis, during and after treatment and in patients with advanced disease (Morrow 2002). Most studies have reported prevalence figures in excess of 60% (Stone 2002). The subjective sensations attributed to CRF are characterised by a pervasive and persistent sense of tiredness not relieved by sleep or rest. This can adversely affect a person's emotional, physical and mental well‐being (Morrow 2005). CRF can also affect patients' abilities to function in terms of their usual social activities, and their ability to carry on with their normal working lives. Fatigue is not only a problem in cancer patients.

Fatigue is a recognised condition within the general population (Bultmann 2002; Lawrie 1997). It is a feature of other chronic illnesses such as multiple sclerosis (Krupp 1988) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Trendall 2001). It can also be a separate diagnosis in its own right in the case of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (Sharpe 1992).

While CRF in some groups may have similarities with CFS there are important differences in particular in relation to concerns about its relationship to disease progression and toxicity of treatment (Servaes 2002).

It has therefore been suggested that CRF should be considered to represent a diagnostic entity in its own right (Cella 2001; Sadler 2002). CRF is a complex condition with many physical and psychological components potentially predisposing people to it. These same factors may also exacerbate and perpetuate established CRF. The complex nature of the condition makes it difficult to identify a clear underlying mechanism. Indeed, it is more than likely that no such single mechanism exists (Andrews 2004). Nevertheless, CRF is a disabling and distressing condition which is often under‐recognised by cancer physicians (Stone 2000).

Previous reviews (Mock 2004; Morrow 2005; Stone 2002) and clinical guidelines (NCCN 2010) have attempted to summarise existing evidence for both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatments for CRF. The main focus of one of these reviews (Mock 2004) was on non‐pharmacological measures where there have been a number of studies investigating exercise interventions and the role of support groups. The review authors concluded that:

exercise had a direct effect on reducing fatigue;

there was some evidence that correction of anaemia improved quality of life and energy.

Another review group focused their review on pharmacological interventions (Morrow 2005). They considered the evidence in support of a number of treatment options:

Antidepressants: on the basis of one study found by this review group (Breitbart 1995) anti‐depressants were suggested as a possible treatment for fatigue associated with advanced disease or uncontrolled symptoms, or both. However, the review authors did not recommend the routine use of anti‐depressants in the absence of concurrent depression. This opinion was based in part on the results of a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted with paroxetine which improved mood but found no effect on fatigue in ambulatory cancer patients (Morrow 2003);

Erythropoietin: this was recommended because it has been studied as a treatment for anaemia in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and some studies reported improvements in fatigue in such patients with the correction of anaemia (Demetri 1998; Glaspy 1997).

Corticosteroids: Morrow 2005 concluded that corticosteroids may produce modest improvements in quality of life including improvement in fatigue in patients with metastatic cancer but that they are limited by the side effects (Bruera 1985).

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network's (NCCN 2010) clinical guidelines also provide further options for CRF management. These suggest initially treating any underlying reversible causes of fatigue (e.g. anaemia, poor nutrition or depression) and attending to general supportive measures and psychosocial support. The most common specific recommendation for an intervention targeted at fatigue is the use of an exercise programme which is the subject of a separate Cochrane review (Cramp 2010). The main drug treatment the NCCN guidelines recommend is the use of methylphenidate in selected cases of cancer‐related fatigue after other non‐pharmacological approaches have been tried. However, most of the evidence for this suggestion is from a trial in HIV patients (Breitbart 2001). A recent RCT in cancer patients failed to find any significant superiority over placebo (Bruera 2006).

The previous literature reviews have made suggestions for the use of different drugs based on varying amounts and quality of evidence. No previous review has collated all of the relevant literature concerning pharmacological interventions for cancer‐related fatigue in a systematic way. A Cochrane systematic review was therefore needed in order to evaluate all the available evidence for the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for CRF. Treatment of fatigue in palliative care will be the subject of another Cochrane review prepared by Radbruch et al. (Radbruch 2007). Close collaboration between the two review author groups will ensure maximum coverage and minimum overlap of the two reviews. This review update was conducted to analyse the increasing number of trials and to address safety concerns raised over haemopoietic growth factors.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and adverse events related to drugs used in the treatment of CRF at all stages of cancer treatment (including palliative care) compared with standard care or non‐pharmacological interventions.

To establish optimal dose and duration of drug therapy(s).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only RCTs of a particular drug therapy were included. Studies that were single blind or open label were allowed.

Types of participants

The review included studies that evaluated drug therapy for CRF in adults (aged 18 and over) and with a clinical diagnosis of cancer. We included studies which had recruited participants at any point of the cancer treatment spectrum, including those undergoing curative treatment, those with advanced disease receiving palliative care, and disease‐free survivors.

Types of interventions

Included studies compared drug therapy with placebo, standard care or an alternative non‐pharmacological treatment for CRF, for example, including nutritional status or mood. Only those studies that investigated drug interventions to improve fatigue as a prior identified aim were included.

Studies comparing different types of cancer‐modifying treatment (e.g. chemotherapy regimens or radiotherapy) and their effect on prognosis and quality of life were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Differences in fatigue between intervention group and controls using patient self‐reported measures or validated self‐assessment tools, or both.

Adverse events including cardiac arrhythmias and thrombo‐embolic events.

Search methods for identification of studies

This search was run for the original review up to week 1 March 2007. The subsequent search has been run up to 1 October 2009.

Electronic searches

We used the search strategy defined in Appendix 1 for this review and adapted it for other databases using text and keyword and MESH terms, in addition to an RCT filter. This strategy was adapted for the following databases ‐ for the different terms that are used in these databases please refer to Appendix 2. There was no language restriction.

The following databases were used to obtain relevant studies for this updated review:

The PaPaS group specialized register (October 2009);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 3, 2009);

MEDLINE to week 1 October 2009;

EMBASE to week 1 October 2009;

CINAHL to week 1 October 2009;

Dissertation Abstracts International to October 2009);

Meta register of controlled trials to October 2009.

Searching other resources

We searched the following journals: British Journal of Cancer to October 2009, Journal of Clinical Oncology to October 2009, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management to October 2009 and Palliative Medicine to October 2009.

We checked reference lists of all articles obtained for additional studies. We also contacted experts in the field of CRF in order to identify any research that may not have been published. We checked published abstracts through searches of conference proceedings and we obtained full trial data if possible. We attempted to communicate with the study authors to secure information not presented in the papers or conference abstracts if not subsequently published as a full article.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection

One review author (OM) screened the eligibility of retrieved articles from the title and abstract. If there was insufficient information for assessment, the full article was scrutinised by two review authors (OM and PS). Two review authors (OM and PS) independently assessed all RCTs. For a trial to be included it must have included fatigue as part of a primary outcome measure and one treatment arm must have been a drug therapy. Disagreement was resolved by consensus with other members of the review group (MS, AR, MH).

Quality assessment

Each trial was assessed for potential bias on the basis of allocation and concealment as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2006). A ‐ adequate; B ‐ unclear; C ‐ clearly inadequate; D ‐ allocation concealment not used. We also assessed the methodological quality of each study using the three item Oxford Quality Scale (Jadad 1996).

(1) Randomisation

Was the study described as randomised? (1 = yes; 0 = no)

Was the method of randomisation well described and appropriate? (1 = yes; 0 = no); deduct one point if inappropriate

(2) Blinding

Was the study described as double‐blind ? (1 = yes; 0 = no)

Was the double blinding well described and appropriate? (1 = yes; 0 = no); deduct one point if inappropriate.

(3) Description of study withdrawals and dropouts

Were withdrawals and dropouts described? (1 = yes; 0 = no)

All studies also had an assessment of efforts made to match groups in terms of prognostic factors. Study quality was further assessed based on intention‐to‐treat analysis, standardisation and blinding of outcome assessment and percentage loss to follow up. This information was used to determine an overall risk of bias from a study ‐ those studies felt to be at an unacceptably high risk of bias were excluded from the review. Study quality was not scored on an additive basis. Impact of study quality was determined by sensitivity analysis.

Data management

Data was organised using RevMan 5 (version 5.1.1). Data extraction forms were developed a priori and included information regarding methods, participant details, dose and frequency of drug administration, attrition and outcome measures. Two review authors (OM and PS) independently extracted data and disagreements were resolved by consensus with the other members of the group (MH, AR, MS).

Heterogeneity assessment

Homogeneity of the results of the various endpoints of interest was explored using I squared (I2) values. Heterogeneity in the results was seen as a result of many potential factors (postulated a priori) and efforts were made to identify sub groups for sensitivity analysis. Meta‐analysis was undertaken. As a result of high statistical heterogeneity we used a random‐effects model for analysis.

Potential sources of heterogeneity:

quality of studies,

medication dose and frequency,

duration of treatment,

duration of follow up,

rate of attrition,

outcome measures used,

case mix/stage of disease accessed.

Statistical considerations

We evaluated quantitative outcomes for dichotomous and continuous data using RevMan 5 and the random‐effects models as the data was not normally distributed. Analysis based on intention to treat was used. Outcomes of interest were compared between treatment and control arms using mean differences and standard deviations.

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) was not calculated because of the continuous outcome data found. A judgement on how to combine outcome measures was made depending on how information was collected. In trials where the same scale was used the weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated to provide an effect size of clinically significant change on one specific outcome measure. In other trials which had different outcome measures, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). The size of difference between mean score change on the meta‐analysis is given by the Z score.

Results

Description of studies

Re‐running the search strategy in MEDLINE ,EMBASE and CENTRAL retrieved 647 additional references. The Updated search identified 12 additional studies potentially suitable for inclusion. Further analysis of these studies found that six did not meet the inclusion criteria for the review. One study met the inclusion criteria but was not possible to include in a meta‐analysis and was not analysed further. Therefore there are now 31 studies included for full analysis; 19 additional studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified but were not analysed. One included study reference (Fleishman 2005) has been altered from the previous version of the review following the publication of the full text paper (Lower 2009) Thirteen trials were excluded (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table).

Included studies

Thirty‐one trials were analysed in more detail generating data on N = 7104 participants who had a drug intervention for CRF. This figure excludes the trials deemed unsuitable for more detailed analysis ‐ nineteen trials with a total of N = 4752 participants.

We divided the trials by classes of drugs used for the treatment of CRF. Those groups which contained more than one study were included in subsequent meta‐analyses. This yielded four separate classes of drugs and three trials in their own separate categories.

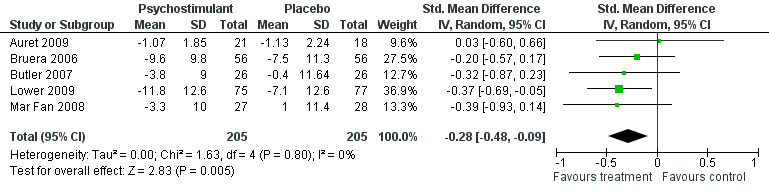

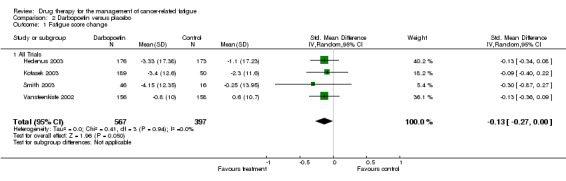

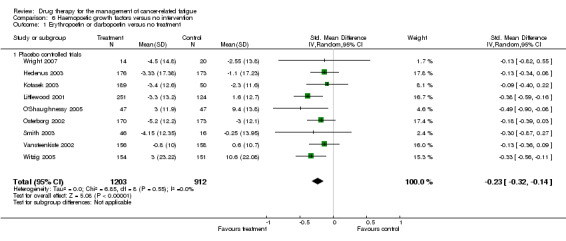

Psychostimulants

Bruera 2006; Butler 2007; Lower 2009; and Mar Fan 2008 all used methylphenidate. Auret 2009 used dexamphetamine. There were five trials with N = 426 participants in total. The Bruera 2006 trial studied participants off active treatment of any tumour type. Participants were blinded for seven days only followed by a non‐randomised open label phase (results not included). The Lower 2009 trial studied participants on chemotherapy (any tumour type) and had eight weeks of follow up. The Butler 2007 trial studied participants with brain tumour or brain metastases undergoing radiotherapy. The Mar Fan 2008 trial studied breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. The Auret 2009 trial studied participants off active treatment of any tumour type but used dexamphetamine as the psychostimulant. (Figure 1).

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Psychostimulants versus placebo, outcome: 5.1 Fatigue score change.

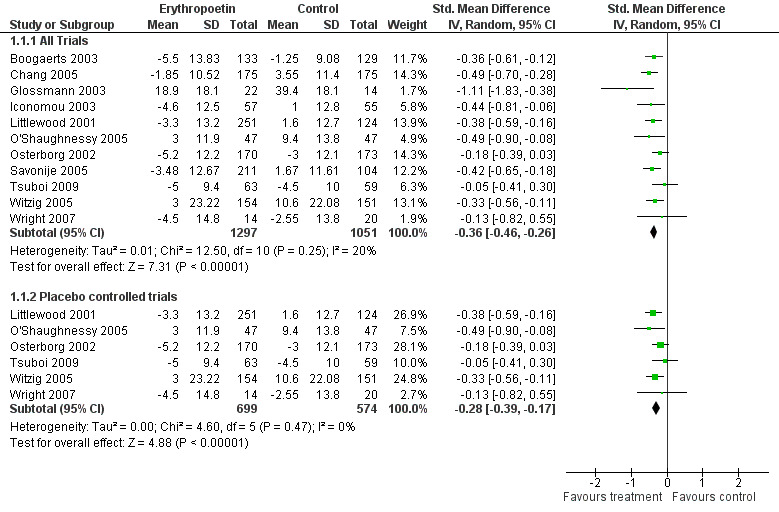

Haemopoietic growth factors

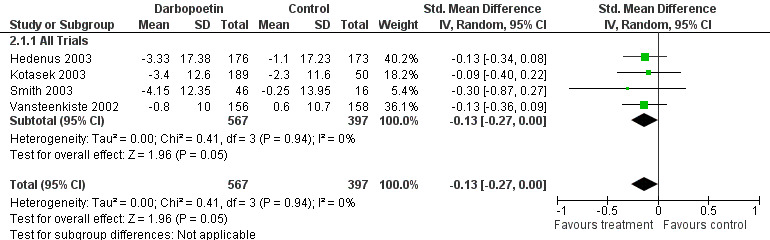

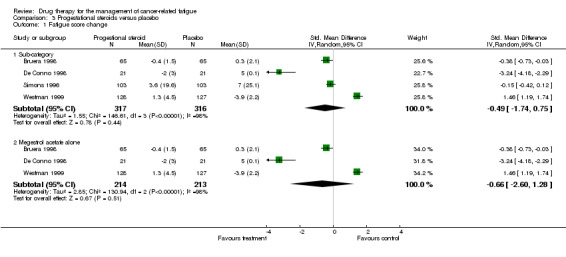

The majority of these trials were in the haemopoietic growth factors class. All trials examined the effect of these drugs on haemoglobin concentrations and their subsequent change in fatigue scores. All trials recruited anaemic cancer patients (Haemoglobin <12 g/dl). This group was split into erythropoietin ‐ fourteen trials N = 3950 participants in total (Bamias 2003; Boogaerts 2003; Chang 2005; Glossmann 2003; Iconomou 2003; Leyland‐Jones 2005; Littlewood 2001; O'Shaughnessy 2005; Osterborg 2002; Savonije 2005; Tsuboi 2009; Wilkinson 2006; Witzig 2005; Wright 2007) and darbopoetin ‐ four trials N = 1650 participants in total (Hedenus 2003; Kotasek 2003; Smith 2003; Vansteenkiste 2002). Darbopoetin is a synthetic derivative of erythropoietin with a similar but longer duration of action.

The trials varied in design with the majority of the erythropoietin trials being open label while the darbopoetin trials were all placebo controlled. This was not related to publication date. All trials had a minimum of 12 weeks follow up with some of up to 18 weeks. Most trials (12/14) were conducted on patients receiving chemotherapy. There was considerable variation in the dose and frequency used and this is given in more detail in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

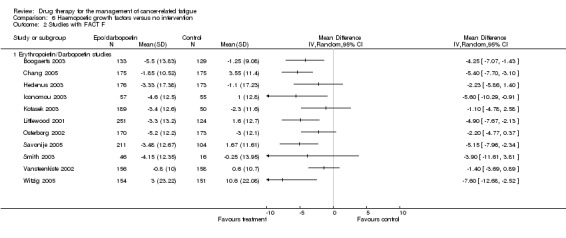

The groups were analysed separately and together in subsequent meta‐analyses (Figure 2; Figure 3 ).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Erythropoetin versus no intervention (sub analysis versus placebo), outcome: 1.1 Difference in fatigue score.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Darbopoetin versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Fatigue score change.

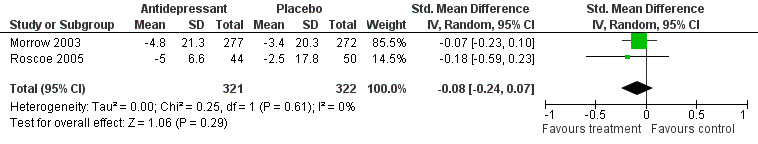

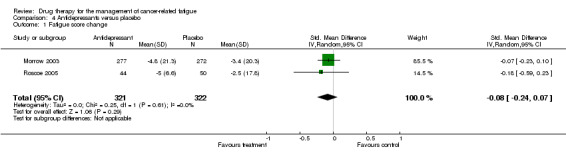

Anti‐depressants

Morrow 2003 and Roscoe 2005 were double blind placebo controlled trials using paroxetine (a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor) during eight weeks of chemotherapy treatment. The Stockler 2007 double blind placebo controlled trial studied the effects of sertraline on fatigue and survival in participants off active treatment‐ the data from this trial is not included in the meta‐analysis as it was not possible to obtain it from the study author. Three trials N = 733 participants in total. The Morrow 2003 study was a multi‐centre trial examining all tumour types. The Roscoe 2005 study was a single centre trial examining breast cancer patients only (Figure 4)

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Antidepressants versus placebo, outcome: 4.1 Fatigue score change.

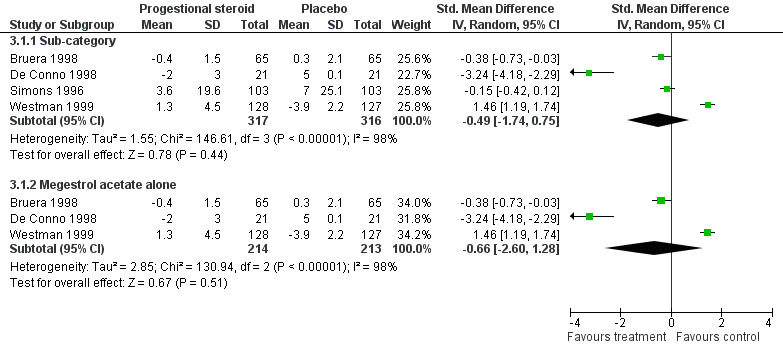

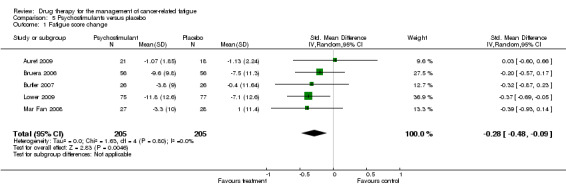

Progestational steroids

Bruera 1998; De Conno 1998; Simons 1996 and Westman 1999 used megestrol acetate or medroxyprogesterone acetate. Four trials with N = 587 participants in total. All were double blind and placebo controlled. Bruera 1998 was a crossover study. The others were double blind parallel design. All trials studied any tumour type and all participants were off active treatment. Follow‐up varied from one to twelve weeks. (Figure 5)

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Progestational steroids versus placebo, outcome: 3.1 Fatigue score change.

Single studies

Diel 2004 used ibandronate for bone pain and reduction in bone morbidity and measured associated changes in quality of life on breast cancer participants. This was a single trial with N = 466 participants. This study used four‐weekly treatments and had up to ninety‐six weeks of follow up.

Monk 2006 examined etanercept (a tumour necrosis factor blocker) and its effect on CRF. This was a single trial with N = 12 participants. This double blind placebo controlled trial used etanercept during docetaxel chemotherapy (for any tumour type) for 18 weeks (six cycles).

Bruera 2007 was a double blind placebo trial of donepezil with N = 142 participants given for one week only. The study failed to demonstrate any benefit over placebo.

Included studies not analysed further

There were 19 included studies that were not analysed further; total N = 3827 participants (Abels 1996; Agteresch 2000; Bruera 1990; Bruera 2003; Capuron 2002; Case 1993; Dagnelie 2003; Dammacco 2001; Della 1989; Downer 1993; Fisch 2003; Granetto 2003; Henry 1995; Inoue 2003; Moertel 1974; Popiela 1989; Semiglazov 2006; Stockler 2007; Thatcher 1999). These studies were all excluded from more detailed analysis as they either used a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) to measure fatigue or the measurement tool used had only one item to measure fatigue ‐ See 'Characteristics of included studies' table. It was felt that a single item on fatigue was an inadequate assessment of this complex symptom and that including studies that only had a single item fatigue measure would introduce an unacceptable outcome bias into our review. In addition this group of trials used heterogeneous outcome measures such as levels of physical function or well‐being. While they might be regarded as a subjective measure of fatigue and so meet our inclusion criteria we felt that they did not provide robust enough evidence for full inclusion in our analysis.

Excluded studies

There were fourteen excluded trials in this updated review. Bruera 1985 was excluded as they measured activity with no subjective measure of fatigue included in the analysis. The two trials by Glapsy et al (Glaspy 2003; Glaspy 2006) and Courneya 2009; Charu 2007; Waltzman 2005 were excluded as they had active control arms ‐ these trials all studied erythropoietin or darbopoetin with no placebo arms. The other four excluded trials (Glimelius 1998; Heras 2009 ; Johansson 2001; Steensma 2006) all studied varying doses of erythropoietin but did not include a usual care or placebo arm. Mantovani 2008 studied multiple treatment arms for cachexia and fatigue but did not include any inactive control. Barton 2009; da Costa Miranda 2009; De Suza 2007 all examined substances not classified as drugs for the purposes of this review‐ see 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed where possible in terms of the adequacy of concealment of allocation. This was done using the criteria defined in The Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2006) where grade A is adequate concealment; grade B is uncertain allocation concealment; grade C is clearly inadequate concealment, grade D ‐ not used). The grade given is shown in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table and in the Forest plots.

The studies are grouped below by the score on the Oxford Quality Scale for quality assessment of RCTs (Jadad 1996). There are an increasing number of quality assessment tools but currently this is the one used by our review authors. It is scored zero to five with five being the highest score indicating the best quality trials.

Oxford Quality Scale Score 5 ‐ Roscoe 2005; Vansteenkiste 2002.

Oxford Quality Scale Score 4 ‐Auret 2009; Bruera 2006; Bruera 2007; Butler 2007; Hedenus 2003; Kotasek 2003; Leyland‐Jones 2005; Littlewood 2001; Mar Fan 2008; Morrow 2003; O'Shaughnessy 2005; Osterborg 2002; Simons 1996; Westman 1999; Wright 2007.

Oxford Quality Scale Score 3 ‐ Bruera 1998; De Conno 1998; Diel 2004; Lower 2009; Savonije 2005; Smith 2003;Stockler 2007; Wilkinson 2006; Witzig 2005.

Oxford Quality Scale Score 2 ‐ Bamias 2003; Boogaerts 2003; Chang 2005; Iconomou 2003; Glossmann 2003; Monk 2006. The average score for the erythropoietin studies is three due to the large number of open label trials.

The darbopoetin studies have an average of four (three studies all double blinded).

The other studies have an amalgamated average of four indicating reasonable quality overall but disguising some wide variation in quality with scores ranging from two to five.

The reasons for lower scores were due to inadequate reporting of the methods used for randomisation and blinding. The Oxford Quality Scale is prescriptive in its application and does not account for the complexity of many of the trials studied. It does, however, highlight the lack of adherence to accepted reporting guidelines (Consort 2007).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Psychostimulants

Five studies looking at the use of psychostimulants were combined in a random effects model N = 413 (Auret 2009; Bruera 2006; Butler 2007; Lower 2009; Mar Fan 2008). The studies are statistically homogeneous with I2 = 0%. This is despite differences in follow up. The overall effect Z score = 2.83 (P = 0.005), SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.48 to ‐0.09.

This is evidence of a significant effect on treating fatigue with methylphenidate over placebo for the treatment of CRF. Figure 1

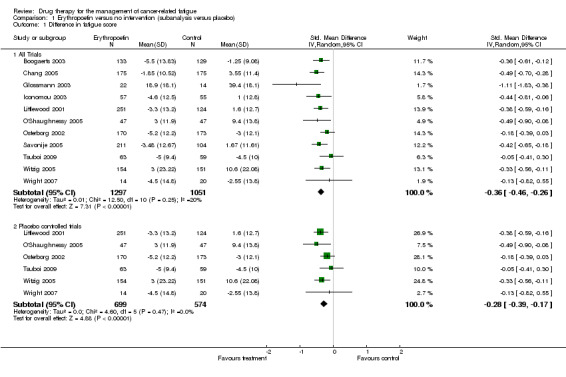

Haemopoietic growth factors

This is the largest group of studies and they will be sub‐divided into erythropoietin and darbopoetin studies. Unfortunately due to the lack of consistency in reporting these trials much of the necessary data for meta‐analysis were missing. The studies where it was not possible to obtain the relevant data were:

Bamias 2003; Leyland‐Jones 2005; Wilkinson 2006 (Total N = 1265) .

Erythropoietin studies

Eleven studies were combined in the erythropoietin analysis N = 3950. There were five open label studies (Boogaerts 2003; Chang 2005; Glossmann 2003; Iconomou 2003; Savonije 2005; (comparison 1.1 and subcategory). There were six placebo controlled studies (Littlewood 2001; O'Shaughnessy 2005; Osterborg 2002;Tsuboi 2009; Witzig 2005; Wright 2007). Due to the difference in quality a sensitivity analysis was also performed.

Combining the eleven trials in a random effects model showed a low degree of heterogeneity I2 = 20%. There was no clear difference in heterogeneity in sensitivity analysis when variation in doses was accounted for. Trials used doses from 3000 to 40,000 units a week and different dosing schedules with some trials using a three times a week dosing and others giving a weekly dose. Tumour type studied also did not affect heterogeneity.

When the six placebo controlled trials (N = 1401) were combined in a subcategory there was homogeneity I2 = 0%. This would suggest the heterogeneity was due to study quality and lack of blinding in allocation. The overall effect Z score = 4.88 (P < 0.0001), SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.17.

When the five open label studies (N = 2459) were combined in a subcategory there was a homogeneity I2 =0%. The overall Z score = 7.15 (P = < 0.0001), SMD ‐0.45, 95% CI ‐0.57 to ‐0.15.

For the eleven trials the overall effect Z score = 7.31 (P < 0.001), SMD ‐0.36, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.26.

All combinations showed evidence of an effect of erythropoietin over standard care or placebo for the treatment of CRF. Figure 2

Darbopoetin studies

Four trials were combined in a random effects model N = 1650; (Hedenus 2003; Kotasek 2003; Smith 2003; Vansteenkiste 2002). All were placebo controlled trials. The trials were homogenous I2 = 0%. One trial investigated patients with lymphoproliferative malignancies only (Hedenus 2003), one lung tumour patients (Vansteenkiste 2002) and one any tumour type (Kotasek 2003). The other included trial (Smith 2003) was conducted on cancer patients not on any chemotherapy. The four trials used different doses which varied form 2.25 µg/kg to 15 µg/kg three times weekly. Only a combined mean effect has been used in the meta‐analysis to avoid duplication.

The overall effect Z score = 1.45 (P = 0.05) , SMD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.00. This indicated that there is a small but statistically significant difference between darbopoetin and placebo for the treatment of CRF. Figure 3

Combined analysis

As darbopoetin is a derivative of erythropoietin and therefore a nearly identical drug with a similar mechanism of action we felt it was appropriate to combine the two groups in a combined analysis of all placebo controlled trials. The following trials were included in a random‐effects model: Hedenus 2003; Kotasek 2003; Littlewood 2001; O'Shaughnessy 2005; Osterborg 2002; Vansteenkiste 2002; Witzig 2005; Wright 2007. Total N = 2801. The overall Z score = 5.08 (P < 0.001), SMD ‐0.23 95% CI ‐0.32 to ‐0.14. This indicated a small but consistent positive effect using either growth factor. It also suggested that the overall effect is increased with the addition of the darbopoetin trials which might be expected from the common mechanism of action. The erythropoietin studies which used the FACT F tool (functional assessment of cancer therapy ‐ fatigue sub scale) (Cella 2002) for fatigue measurement were combined in a random effects model but using weighted mean difference (WMD). The overall Z score = 6.13, SMD ‐4.29, 95% CI ‐5.04 to ‐2.60. This indicates that overall these trials may provide a clinically significant reduction in fatigue.

Paroxetine

Two studies N = 645 (Morrow 2003; Roscoe 2005; comparison 04 01) were combined in a random‐effects meta‐analysis. The studies were homogenous I2 = 0%. The test for overall effect ‐ Z score was 1.17 (P = 0.24), SMD ‐0.08 95 % CI ‐4.64 to 1.18.

This indicated no difference between paroxetine and placebo for the treatment of CRF. Figure 4

Progestational steroids

Four studies N = 587 (Bruera 1998; De Conno 1998; Simons 1996; Westman 1999) were combined in a random‐effects model (comparison 3.1).

The studies showed a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 98.8%). This may be explained by difference in dosing regime (from 160 milligrams to 320 milligrams once a day). The Simons study used medroxyprogesterone acetate while the others all used megestrol acetate. However, when this study was excluded the heterogeneity remains very high (I2 = 98%). There are other factors which may contribute. The duration of study varied widely from ten days (Bruera 1998) to 12 weeks (Simons 1996; Westman 1999).

Tumour type ‐ apart from Bruera 1998 (only included gastrointestinal (GI) and lung tumours) any tumour was included in all the remaining studies.

Two studies allowed palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Simons 1996; Westman 1999) this was in the minority of patients (10%) and matched in both treatment groups. The other two studies (Bruera 1998; De Conno 1998) did not allow any concomitant therapy.

The four studies were combined in a random‐effects model as there was significant heterogeneity despite limited sensitivity analysis. The overall effect Z score is 0.78 (P = 0.44) SMD ‐0.49 95% CI ‐1.74 to 0.75. The effect of megestrol acetate alone is Z = 0.67 (P = 0.5) SMD ‐0.66, 95% CI ‐2.6 to 1.28. This indicated no difference between progestational steroids and placebo for the treatment of CRF. Figure 5

Single studies

As these are individual trials no synthesis of the data was possible.

The Ibandronate study N = 466 (Diel 2004) was a trial with long term follow up of nearly two years. It recruited participants with breast cancer only. The results showed that the ibandronate group had a statistically significant difference in fatigue scores at the 96 week outcome assessment. There was no clear dose response with different dosing schedules. All groups experienced increases in fatigue scores over the time of the study

One single study used etanercept in conjunction with docetaxel chemotherapy (Monk 2006). This was a trial on a very small number of participants (N = 12) but that studied all tumour types. It was a pilot study but with 'positive' results ‐ the etanercept group showed a statistically significant reduction in fatigue compared to patients treated with docetaxel alone.

The final single study used donepezil N =142 (Bruera 2007) for one week only but showed no benefit over placebo.

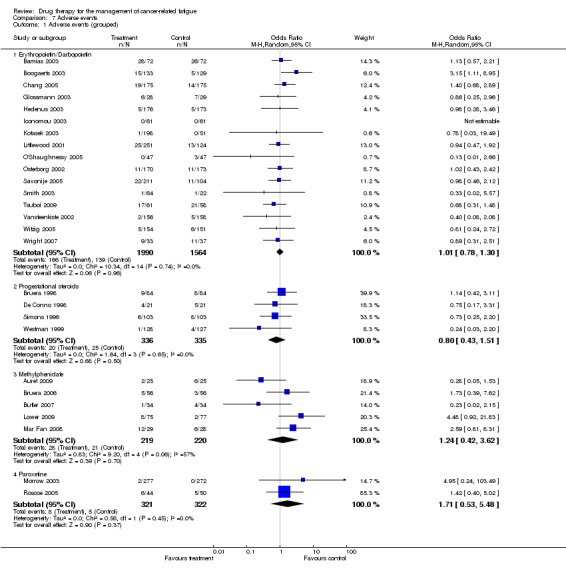

Adverse events

This updated review did not find any increase in adverse effects in the drug classes studied. However there has been a meta‐analysis (Bohlius 2009) examining the adverse effects of the hematopoietic growth factors. On a number of sub group analyses the authors of this review found an increase in mortality in advanced cancer patients and many more adverse events in the treated groups.

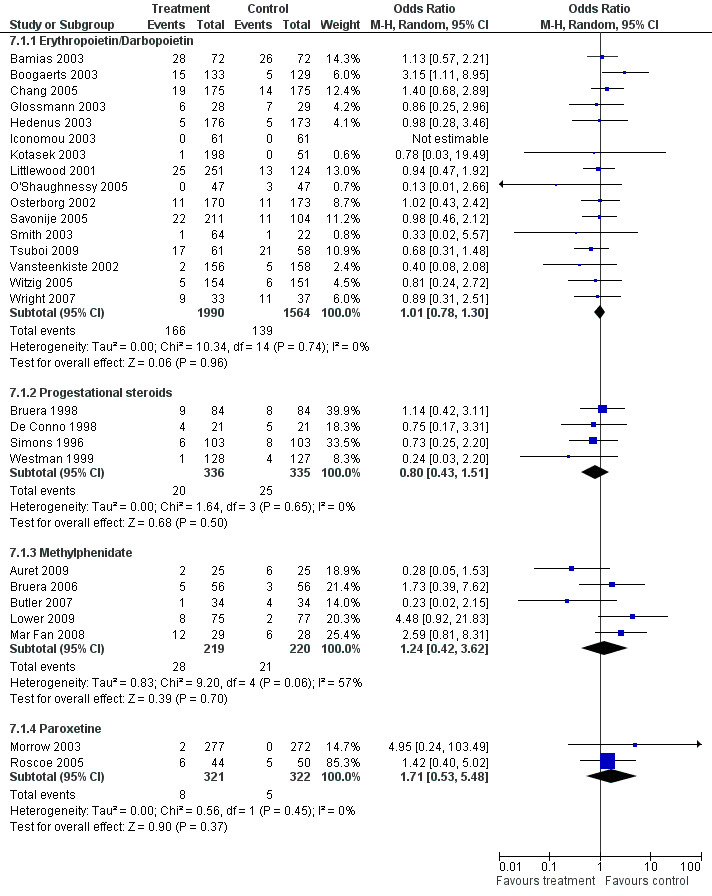

The majority of trials had minimal reported adverse events. The analysis for grouped adverse events (comparison 7.1) demonstrated some variation across the different drugs.

The haemopoietic growth factors had a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.30 indicating a non statistically significant between group difference. The progestational steroids had an OR of 0.8, 95% CI 0.4 to 1.51 indicating a non statistically significant between group difference. The psychostimulant studies had an OR of 1.24, 95% CI 0.42 to 3.62 indicating a non statistically significant between group difference. The paroxetine studies had an OR of 1.71, 95% CI 0.53 to 5.48 indicating a non statistically significant between group difference. Figure 6

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 7 Adverse events, outcome: 7.1 Adverse events (grouped).

Some of the erythropoietin trials highlighted ongoing safety concerns. Leyland‐Jones 2005 was primarily a survival study. It was designed to compare mortality rates between groups not receiving chemotherapy. The erythropoietin group showed increased mortality at four months and the trial was terminated prematurely. It was felt that there may have been an increased rate of fatal thrombo‐embolic events in the erythropoietin arm over placebo (1.1% versus 0.2% at four months). The rate of serious adverse events was 5% in the erythropoietin arm versus 2% with placebo. This study was designed to keep haemoglobin at 12 to 14 g/100 ml. Current prescribing guidelines state that a haemoglobin of 12 g/100 ml should not be exceeded (BNF 53).

Wright 2007 was also prematurely terminated as a result of safety concerns. The data monitoring committee suspended the trial after it was noted that the median survival in the epoetin group was worse than placebo. The cause for this discrepancy was unclear and may not have been solely due to adverse events related to the medication. Nevertheless current prescribing guidelines should be adhered to and a lower maintenance haemoglobin aimed for.

A more comprehensive and quantitative assessment of all adverse events of these agents is made in another Cochrane review (Bohlius 2007). The reader is also referred to the review by the same group published in 2009 (Bohlius 2009). The authors of this review detail new safety concerns about the use of haemopoietic growth factors in treating cancer related anaemia.

Discussion

The aim of this Cochrane review was to look at the overall effect of drugs on CRF. The study has yielded a large number of trials of varying size and quality. It has also demonstrated the wide range of tools used for fatigue or quality of life measurement, or both. The large number of trials identified allowed for synthesis of data and the quantification of the clinical effect of the drugs used on CRF which previous narrative reviews have been unable to do.

The review was comprehensive as it was impracticable to specify in advance which drugs would be studied. The included RCTs incorporate four different drug classes where results could be combined and two separate single trials. Other drugs were identified during the search strategy but none were examined within a RCT and so none of those trials are reported. However, some of these drugs are now being studied within a RCT. These trials are listed in the 'characteristics of ongoing studies' table. There are ongoing trials investigating the effects of modafinil (Drappatz 2009; Duffy 2009; Morrow 2007; Wee 2009); levo carnitine (Cruciani 2007); co‐enzyme Q10 (Frizell 2007); adenosine triphosphate (Dagnelie 2007); There are also three ongoing trials that will add to the data on methylphenidate (Hutson 2007; Roth 2007; Sood 2006) and one ongoing trial examining etanercept (Thomas 2007). On viewing the current data some general comment about the trials underway are warranted before a more detailed discussion on individual analyses is given.

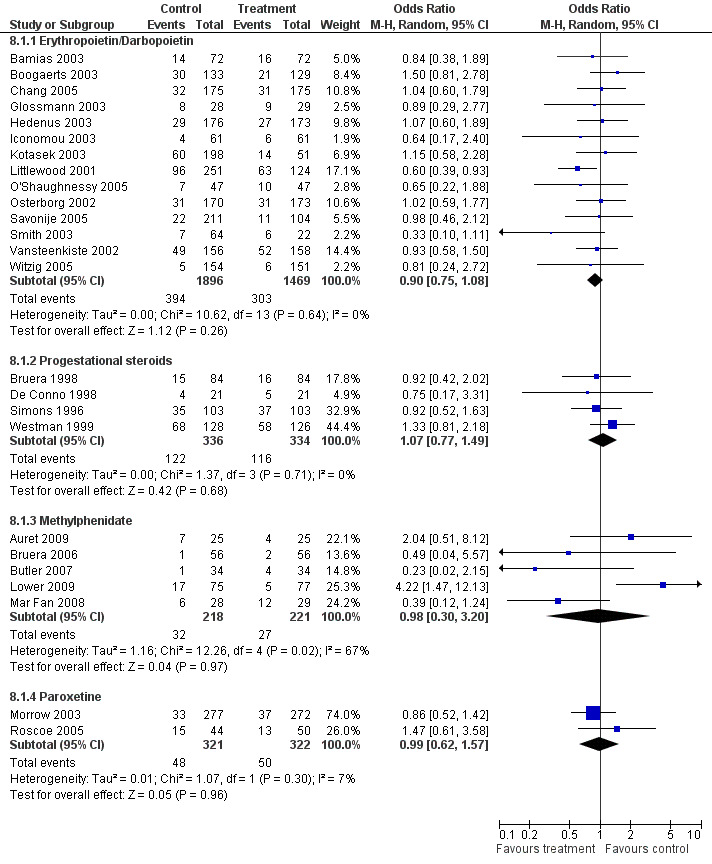

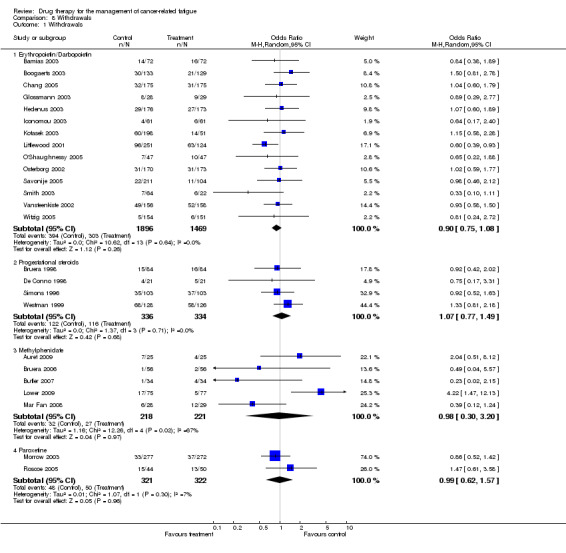

While the quality of some trials was mediocre on the scale used this may be due to lack of consistency in trial reporting and failure to adhere to CONSORT guidelines (Consort 2007). There is a high rate of attrition in some studies but this is due more to the population studied than reported adverse events. The rate of attrition was mainly due to disease progression and the complex nature of any concurrent treatment. This led to large withdrawals because of death or protocol violation. If this was not reported in the trial publication then the quality score given was lower. There are no between group differences in withdrawal rate for all drugs studied (Figure 7). The heterogeneity of some of the trials may also have been due to a low signal:noise ratio. There were many factors such as disease progression and the unstable nature of the population which may have affected heterogeneity which it has not been possible to account for. However, for the erythropoietin trials heterogeneity was mainly due to differences in study design.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 8 Withdrawals, outcome: 8.1 Withdrawals.

All trials demonstrated statistical non significance between group differences for important prognostic factors. This included a detailed description of stage and type of tumour and concurrent treatment (if any). If specific methods were required to match the randomised groups this was invariably achieved with stratification by tumour type and treatment. There were no exceptions to this. There were also no significant differences in any trial in relation to missing data.

There was some variation in the withdrawal rates but nearly all trials were analysed on an intention to treat basis. The exception to this was Boogaerts 2003 that used last observation carried forward (LOCF). The variations in the quality of trials and any impact in a sensitivity analysis will be commented on for each drug.

Psychostimulants

Five studies (Auret 2009; Bruera 2006; Butler 2007; Lower 2009; Mar Fan 2008) were combined. The standardized mean difference (SMD) on analysis was positive with a small effect seen and narrow confidence interval. The five studies did differ in design and follow up but used the same outcome measure (FACT F) and so it is possible to obtain a weighted mean difference (WMD) of ‐2.21. This translates as the value equal to the previously calculated minimal clinically significant difference (2 point change) on this scale (Cella 2002). This gives the result's clinical relevance ‐ these drugs lead to an observable improvement in fatigue. The current evidence supports the use of psychostimulants in the treatment of CRF. In addition there are three further trials being conducted with methylphenidate that may potentially increase the available evidence base (see 'characteristics of ongoing studies' table).

Erythropoietin

There are a number of studies included in the analysis. Eleven studies were combined in total and demonstrated a positive effect. This persisted in a sensitivity analysis of placebo controlled trials although the CI was much narrower. It was not possible to generate a number needed to treat (NNT) as the data were continuous. A WMD was generated using a sub‐analysis of studies using the FACT F and gave a score of 4.33. Again this value was above the minimal clinically significant difference. This would suggest that erythropoietin does provide a recognisable reduction in fatigue. This conclusion was limited to anaemic patients undergoing chemotherapy only. As there have been more recent safety concerns close monitoring of haemoglobin should also be instigated. This is especially important as previous multivariate regression (Jones 2004) has shown that haemoglobin only accounts for a small (approximately 20%) percentage of fatigue symptomology. The authors also demonstrated that greater improvement was most likely to be seen at lower haemoglobin concentrations (8 to 10 g/100 ml). The improvement in fatigue may not necessarily be due to improvement in haemoglobin concentrations after a minimum level has been reached. However in conclusion overall new safety concerns raised now mean that any potential improvement in fatigue is out weighed by the increase risk of harm from these drugs.

Darbopoetin

The four placebo controlled trials combined in a random‐effects model showed superiority over placebo. Three of the trials (Hedenus 2003; Kotasek 2003; Smith 2003) had multiple dose treatment arms. The reporting of these trials only gave changes in fatigue score based either on dose of darbopoetin or haemoglobin change. Thus it was necessary to calculate the average response in order to undertake a meta‐analysis. The authors were contacted to provide original trial data. The result seen is as expected as darbopoetin is a derivative of erythropoietin and has an almost identical mechanism of action. However, the WMD using the FACT F gave a score of ‐1.96 slightly below the minimal clinically significant difference. It is possible that further trials may strengthen this result but future trials need to focus on fatigue measurement with a simplified or fixed dosing regime to avoid the complex analyses from previous trials which has made data extraction so difficult.

Erythropoietin/darbopoetin

A further analysis was carried out combining all the placebo controlled trials. This demonstrated a positive result using a random‐effects model. The effect size was increased when the erythropoitetin/darbopoetin trials were combined over the erythropoietin trials alone. As we were interested in the mean effect of treatment on fatigue this data would seem to provide further evidence for their use in clinical practice. The review identified three head to head trials (Glaspy 2003; Glaspy 2006; Waltzman 2005) which suggested that neither treatment was inferior on the limited fatigue data provided. However, it was not the aim of the review to demonstrate superiority of one treatment over another. In addition these studies were not primarily designed to look at quality of life changes for the two drugs. The combined WMD using all studies using the FACT F gave a score of 3.75 ‐ above the minimal clinically significant difference on this scale. Data on transfusion requirements and haemoglobin changes for the two drugs can be found in another Cochrane review (Bohlius 2007).

Paroxetine

Two studies were combined (Morrow 2003; Roscoe 2005). These trials were conducted by the same group concurrently but were separate trials in their own right. The analysis fails to show any benefit of paroxetine for the treatment of CRF. The addition of a third antidepressant trial of sertraline (Stockler 2007) did not alter these findings. There were many measures made of fatigue and mood within the study but only the primary fatigue outcome was included in our analysis. The results of the trials demonstrate an improvement in mood with no associated improvement in fatigue. It is not clear, however, if this is a class effect related to all antidepressants. The use of antidepressants with different mechanisms of action may improve fatigue. Further trials may yet add more evidence. This is, however, an important negative result as many clinicians view the two symptoms as having a large overlap. While fatigue may be a symptom of a depressive illness, this data reinforces our contention that cancer‐related fatigue is an entity in its own right.

Progestational steroids

Four studies (Bruera 1998; De Conno 1998; Simons 1996; Westman 1999) were combined. The analysis demonstrates no superiority over placebo for this class of drugs. While all these trials are older than other included trials they were of good quality and placebo controlled. There is no evidence to support their continued use for the treatment of fatigue in current practice. There is no requirement for additional trials as the analysis demonstrates a consistent negative effect.

Single trials

There are three separate trials which were not combined.

Diel 2004 examined the use of ibandronate over a period of two years. The results indicate that there is limited evidence to support the use of ibandronate in the treatment of CRF over a long term follow‐up. The effect is likely to be due to reduction in bone morbidity rather than directly improving fatigue per se. However, it is the only study to use a measure of fatigue over a long follow up period in patients with metastatic disease. The clinical significance of the results are unclear and further targeted trials are needed.

Monk 2006 examined the use of etanercept during chemotherapy. While the results are statistically significant the small numbers and poor design mean that further larger and better quality trials are needed to explore this effect. This study was conducted with one type of chemotherapy only and the results cannot readily be extrapolated. There is very limited evidence to support its use currently outside of a study setting. Future trials should be conducted with larger numbers as the proof of concept has been achieved in this small study.

Bruera 2007 examined the use of donepezil in patients off active treatment. There was no benefit over placebo and no further examination of this drug is indicated.

Limitations

This review was focused on fatigue and does not make any comment on the overall quality of life (QOL) changes that may be seen with the use of these drugs. There is likely to be a relationship between improving fatigue and improving QOL. Indeed in many trials the two terms are used interchangeably. We have extracted data on fatigue changes only. During the review process if we felt that data did not provide a detailed measure of fatigue then the study was not analysed further.

There were only continuous data available from the trials with only mean score change analysed in the meta‐analysis. The diverse conduct and quality of the trials meant that there is large variance in outcome data. This means that combined between group changes need to be interpreted with caution and the conclusions of the review are necessarily limited.

We included trials that assessed outcomes using overall QOL in addition to pure fatigue scales. However, in many cases the trials were often published in ways that made extraction of the fatigue data impossible. Often only a limited comment was made on the effect on QOL with no quantitative data recorded if multiple outcome measures were included.

This was most often the case in the erythropoietin/darbopoetin trials where multiple measures of QOL were obtained but not published. This reaffirms the findings of a previous Cochrane review (Bohlius 2007) where quantifying QOL changes with these drugs was not included because of missing data. We have tried to include as much data in our analysis as possible by contacting authors to obtain data. This may have had the propensity to introduce bias into our study as this data has not been peer reviewed.

It is also possible that the difficulties in conducting these types of trials with any of these drugs may mean that trials have not been published at all. There is therefore the potential for a publication bias in this review. However, by contacting experts in this field we have attempted to reduce this bias as much as possible.

This review also demonstrated that there is still no consensus as to how QOL data should be presented. A single study report will often not give useful data about QOL changes due to limited space for data reporting and study complexity. It is hoped that this review will serve to highlight this weakness in study reporting.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Four methylphenidate trials provided equivocal evidence for its use in a dose of 10 to 20 mg per day depending on response. Serious adverse effects were minimal but contra‐indications to this drug should be reviewed before prescribing.

Erythropoietin and darbopoetin can no longer be recommended for the treatment of CRF given the increase in adverse events associated with these drugs.

Implications for research.

This review highlighted the large number of outcome measures used to examine fatigue. It found major limitations in reporting of trials. Future trials in this area should focus on fatigue as a primary outcome using validated outcome measures.

Further large scale RCTs should be conducted using methylphenidate to evaluate these preliminary results further. Other candidate drugs needing further evaluation include tumour necrosis factor blocking drugs.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 December 2013 | Review declared as stable | This review is no longer being updated. See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 1, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 July 2010 | Amended | Moved link to previous version of this update from the Abstract to the first sentence of the main Background. |

| 17 June 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Six new studies added. Conclusions regarding the use of haemopoietic growth factors changed. |

| 25 January 2010 | New search has been performed | Update search in October 2009. |

| 1 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

This review is no longer being updated, but will be incorporated into the update of another review, 'Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated with palliative care' (Peuckmann‐Post V, Elsner F, Krumm N, Trottenberg P, Radbruch L. Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated with palliative care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD006788. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006788.pub2). This review will be withdrawn upon publication of the update, anticipated in 2014.

Acknowledgements

The search strategy was developed with the assistance of Sylvia Bickley, Trials search Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group. We would like to thank Amgen; Johnson & Johnson; Dr J Wright; Professor J Vansteenkiste; Dr K Auret and Dr D Case for making additional unpublished data available.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 Exp NEOPLASMS #2 BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION #3 neoplasm* or cancer* or carcinoma* or tumour* or adenocarcinoma* or leukeni* or leukaemi* or lymphoma* or tumor* or malignan* (title, abstract & keywords) #4 neutropeni* or neutropaeni* (title, abstract & keywords) #5 Exp RADIOTHERAPY #6 radioth* or radiat* or irradiat* or radiochemo* or chemotherap* (title, abstract & keywords) #7 "bone marrow" NEAR transplant* #8 "bone‐marow" NEAR transplant* #9 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or#7 or #8 #10 FATIGUE (drug therapy) #11 fatigue* (title, abstract & keywords) #12 tired* or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted or lacklustre or astheni* or asthenia* #13 lack* NEAR/2 energy #14 lack* NEAR/2 vigour #15 lack* NEAR/2 vigor #16 loss NEAR/2 energy #17 loss NEAR/2 vigour #18 loss NEAR/2 vigor #19 lost NEAR/2 energy #20 lost NEAR/2 vigour #21 lost NEAR/2 vigor #22 apathy or apathetic or lassitude or letharg* or "feeling drained" or "feeling sleepy" or "feeling sluggish" or "feeling weak*" #23 #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 #24 #9 AND #23

Appendix 2. Other search strategies

| Search terms for MEDLINE |

| 1 Exp NEOPLASMS |

| 2 Exp BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION/ |

| 3 neoplasm$ or cancer$ or carcinoma$ or tumour$ or adenocarcinoma$ or leukeni$ or leukaemi$ or lymphoma$ or tumor$ or tumor$ or malignan$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 4 neutropeni$ or neutropaeni$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 5 Exp RADIOTHERAPY |

| 6 radioth$ or radiat$ or irradiat$ or radiochemo$ or chemotherapy$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 7 (("bone marrow" adj4 transplant$) or ("bone‐marow" NEAR transplant$)) |

| 8 OR/1‐7 |

| 9 FATIGUE/ (drug therapy) |

| 10 fatigue$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 11 tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted or lacklustre or astheni$ or asthenia$ |

| 12 ((lack$ or loss or lost) adj2 (energy or vigour or vigor) |

| 13 (apathy or apathetic or lassitude or letharg$ or (feeling adj3 (drained or sleepy or sluggish or weak$))) |

| 14 OR/9‐13 |

| Search terms for EMBASE |

| 1 Exp NEOPLASM |

| 2 BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION/ |

| 3 neoplas$ or cancer$ or carcinoma$ or tumour$ or adenocarcinoma$ or leukeni$ or leukaemi$ or lymphoma$ or tumor$ or tumor$ or malignan$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 4 neutropeni$ or neutropaeni$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 5 Exp RADIOTHERAPY |

| 6 radioth$ or radiat$ or irradiat$ or radiochemo$ or chemotherapy$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 7 (("bone marrow" adj4 transplant$) or ("bone‐marow" NEAR transplant$)) |

| 8 OR/1‐7 |

| 9 FATIGUE/ (drug therapy) |

| 10 fatigue$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 11 tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted or lacklustre or astheni$ or asthenia$ |

| 12 ((lack$ or loss or lost) adj2 (energy or vigour or vigor) |

| 13 (apathy or apathetic or lassitude or letharg$ or (feeling adj3 (drained or sleepy or sluggish or weak$))) |

| 14 OR/9‐13 |

| 15 8 AND 14 |

| Search terms for CINAHL |

| 1 Exp NEOPLASM |

| 2 BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION/ |

| 3 neoplas$ or cancer$ or carcinoma$ or tumour$ or adenocarcinoma$ or leukeni$ or leukaemi$ or lymphoma$ or tumor$ or tumor$ or malignan$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 4 neutropeni$ or neutropaeni$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 5 Exp RADIOTHERAPY |

| 6 radioth$ or radiat$ or irradiat$ or radiochemo$ or chemotherapy$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 7 (("bone marrow" adj4 transplant$) or ("bone‐marow" NEAR transplant$)) |

| 8 OR/1‐7 |

| 9 CANCER FATIGUE/ (drug therapy) |

| 10 fatigue$ (title, abstract & keywords) |

| 11 tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted or lacklustre or astheni$ or asthenia$ |

| 12 ((lack$ or loss or lost) adj2 (energy or vigour or vigor) |

| 13 (apathy or apathetic or lassitude or letharg$ or (feeling adj3 (drained or sleepy or sluggish or weak$))) |

| 14 OR/9‐13 |

| 15 8 AND 14 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Erythropoetin versus no intervention (subanalysis versus placebo).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Difference in fatigue score | 11 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 All Trials | 11 | 2348 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.36 [‐0.46, ‐0.26] |

| 1.2 Placebo controlled trials | 6 | 1273 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.28 [‐0.39, ‐0.17] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Erythropoetin versus no intervention (subanalysis versus placebo), Outcome 1 Difference in fatigue score.

Comparison 2. Darbopoetin versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatigue score change | 4 | 964 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.27, 0.00] |

| 1.1 All Trials | 4 | 964 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.27, 0.00] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Darbopoetin versus placebo, Outcome 1 Fatigue score change.

Comparison 3. Progestational steroids versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatigue score change | 4 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Sub‐category | 4 | 633 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.49 [‐1.74, 0.75] |

| 1.2 Megestrol acetate alone | 3 | 427 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.66 [‐2.60, 1.28] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progestational steroids versus placebo, Outcome 1 Fatigue score change.

Comparison 4. Antidepressants versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatigue score change | 2 | 643 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.24, 0.07] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 1 Fatigue score change.

Comparison 5. Psychostimulants versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatigue score change | 5 | 410 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.28 [‐0.48, ‐0.09] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Psychostimulants versus placebo, Outcome 1 Fatigue score change.

Comparison 6. Haemopoetic growth factors versus no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Erythropoetin or darbopoetin versus no treatment | 9 | 2115 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.23 [‐0.32, ‐0.14] |

| 1.1 Placebo controlled trials | 9 | 2115 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.23 [‐0.32, ‐0.14] |

| 2 Studies with FACT F | 11 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Erythropoietin/Darbopoetin studies | 11 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Haemopoetic growth factors versus no intervention, Outcome 1 Erythropoetin or darbopoetin versus no treatment.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Haemopoetic growth factors versus no intervention, Outcome 2 Studies with FACT F.

Comparison 7. Adverse events.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Adverse events (grouped) | 27 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Erythropoietin/Darbopoietin | 16 | 3554 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.78, 1.30] |

| 1.2 Progestational steroids | 4 | 671 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.43, 1.51] |

| 1.3 Methylphenidate | 5 | 439 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.42, 3.62] |

| 1.4 Paroxetine | 2 | 643 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.71 [0.53, 5.48] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Adverse events, Outcome 1 Adverse events (grouped).

Comparison 8. Withdrawals.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Withdrawals | 25 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Erythropoietin/Darbopoietin | 14 | 3365 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.75, 1.08] |

| 1.2 Progestational steroids | 4 | 670 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.77, 1.49] |

| 1.3 Methylphenidate | 5 | 439 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.30, 3.20] |

| 1.4 Paroxetine | 2 | 643 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.62, 1.57] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Withdrawals, Outcome 1 Withdrawals.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Abels 1996.

| Methods | Double blind placebo control | |

| Participants | N = 413 non myeloid mixed cancer population Male 197 Female 216 average age 61.9 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoetin 150 U/kg 3 x week N = 213 matching placebo N = 200 up to 8 weeks duration | |

| Outcomes | Quality of life on VAS | |

| Notes | Single item fatigue measurement ‐ unsuitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Agteresch 2000.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Advanced non small cell cancer patients N = 58 Male 38 Female 20 Average age 62.5 | |

| Interventions | ATP (adenosine tri‐phosphate) infusion up to 75 µg/kg 2 to 4 weekly N = 28 supportive care N = 30 | |

| Outcomes | Rotterdam symptom control checklist | |

| Notes | Single item fatigue scores ‐not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Auret 2009.

| Methods | double blind | |

| Participants | N =50 mixed cancer patients off treatment | |

| Interventions | dexamphetamine 20mg or matching placebo n =25 in each group for 8 days males 36 female 14 mean age 71 |

|

| Outcomes | brief fatigue inventory | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ adequate |

Bamias 2003.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Solid tumours receiving platinum chemotherapy N = 144 Male 74 Female 70 Average age 61 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoetin 10,000 U sc 3 x week for 12 weeks N = 72 no treatment N = 72 | |

| Outcomes | EORTC QLQ 30 | |

| Notes | Fatigue subscale not mentioned ‐ not suitable for further analysis (see footnote) Oxford Quality Score 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Boogaerts 2003.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Any tumour type at least three cycles of chemotherapy N = 262 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoetin 150 u/kg 3 x week for 12 weeks N = 133 usual care and transfusion PRN N = 129 Male 98 Female 164 Average age 62 | |

| Outcomes | FACT‐F score change epo = +5.5 (1.6) usual care = +0.5 (0.7) | |

| Notes | LOCF analysis ‐ missing data on quality of life outcomes not ITT Oxford Quality Score 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Bruera 1990.

| Methods | Crossover double blind placebo control | |

| Participants | Advanced cancer not on treatment N = 40 Male 30 Female 10 average age 62 | |

| Interventions | Megestrol acetate 480 mg od or placebo for seven days and cross over | |

| Outcomes | Single item scores in well being and energy | |

| Notes | Single item ‐ not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bruera 1998.

| Methods | Cross over placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Lung and GI tumours N = 84 Male 47 Female 37 Average age 62 | |

| Interventions | Megestrol acetate 160 mg od 10/7 or placebo and two day washout and crossover | |

| Outcomes | Piper fatigue scale overall change megestrol = ‐0.4 (1.5) placebo +0.3 (2.1) | |

| Notes | n = 19 lost due to progressive disease no adverse events due to medication Oxford Quality Score 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bruera 2003.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Any tumour type N = 91 Male 27 Female 63 Average age 63.8 | |

| Interventions | Fish oil capsules 1000 mg daily N = 46; placebo capsules N = 46 | |

| Outcomes | VAS score changes at day 14 ‐ tiredness | |

| Notes | Single item score ‐ unsuitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bruera 2006.

| Methods | Parallel double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Any tumour type >4 VAS fatigue N = 112 Male 39 Female 68 Average age 56.5 | |

| Interventions | Methylphenidate 5 mg two hourly/PRN up to 20 mg/24 hrs n = 56 or matching placebo n = 56 for seven days | |

| Outcomes | FACT‐F methylphenidate +9.6 (9.8) placebo +7.5 (11.3) | |

| Notes | Seven days double blind ‐ no change improvement in open label phase Oxford Quality Score 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bruera 2007.

| Methods | Parallel double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | any tumour type with VAS >4 for fatigue , symptoms of greater than 1 week N=142 ( males and females equal) |

|

| Interventions | donepezil 5mg od or matched placebo for one week | |

| Outcomes | FACT F donepezil ‐6 (10.6) placebo ‐7.2 (9.5) |

|

| Notes | single study not for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A‐ Adequate |

Butler 2007.

| Methods | Parallel double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Brain tumour patients undergoing cranial radiotherapy (stratified by primary or secondary tumour) 34 in each arm ( males= 37 females = 31) average age 56 |

|

| Interventions | Methylphenidate 5mg BD increasing to 20mg Bd for up to 8 weeks during radiotherapy. | |

| Outcomes | FACT F methylphenidate ‐3.4 (9) placebo ‐ 0.4 (11.6) |

|

| Notes | study terminated early due to poor recruitment ‐ underpowered. Large dropout over course of study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Capuron 2002.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Resected melanoma receiving interferon alpha N = 40 for up to 12 weeks of therapy Male 20 Female 20 Average age 51 | |

| Interventions | Paroxetine 20 mg N = 20 placebo N = 20 | |

| Outcomes | Single item included in assessment of depressive symptoms | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Case 1993.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Any tumour type on chemotherapy N = 153 Male 62 Female 95 Average age 64 | |

| Interventions | 150 u/kg erythropoietin 3 x week or matching placebo for up to 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Single item VAS | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Chang 2005.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Breast cancer on chemotherapy N = 350 Average age 50.3 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoetin 40,000 u 1x week N = 175 standard care N = 175 for up to 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | FACT ‐F erythropoietin = +1.85 (10.5) standard care = ‐3.55 (11.4) | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Dagnelie 2003.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Non small cell lung ca N = 58 Male 40 Female 18 average age 57 | |

| Interventions | ATP infusions two to four weekly N = 28 Standard care N = 30 3/12 duration | |

| Outcomes | Single item score from Rotterdam symptom checklist | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis partial duplication of Agertasch 2000 data | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Dammacco 2001.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Myeloma N = 145 Male 67 Female 78 average age 66.5 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoietin 150 u/kg 3 x week or matching placebo for 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Single item scales | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

De Conno 1998.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Any tumour type N = 42 Male 31 Female 11 average age 61.5 | |

| Interventions | Megestrol acetate 320mg od 14/7 N = 21 placebo N = 21 | |

| Outcomes | Profile of mood states fatigue subscale MA = ‐2.0 (‐3 to 0) placebo 0 (‐0.5 to +0.1) | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Della 1989.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Any tumour type N = 403 Male 198 Female 207 average age 62.7 | |

| Interventions | Methylprednisolone 125 mg od IV daily eight weeks matching placebo | |

| Outcomes | Single item VAS | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Diel 2004.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Breast cancer N = 466 average age 55.4 | |

| Interventions | Ibandronate 2 mg IV four weekly N = 154 ibandronate 6 mg IV four weekly N = 154 placebo N = 158 up to 96 weeks treatment | |

| Outcomes | EORTC QLQ 30 fatigue subscale ibandronate 2 mg = +4.58 (2.3) 6 mg = +4.84 (2.2) placebo = +10.41 (2.3) | |

| Notes | Dose arms were open label due to infusion volumes Oxford Quality Score 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Downer 1993.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Breast cancer N = 60 Average age 62 | |

| Interventions | Medroxyprogesterone acetate 100 mg tds six weeks N = 30 or placebo N = 30 | |

| Outcomes | Single item VAS | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Fisch 2003.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Any tumour type N = 163 Male 80 Female 83 average age 60 | |

| Interventions | Fluoxetine 20 mg od 12 weeks N = 83 or placebo N = 80 | |

| Outcomes | Single item from FACT‐G | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Glossmann 2003.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Lymphoma N = 57 (on high dose chemotherapy) Male 33 Female 22 average age 37 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoetin 10,000 u 3x week N = 28 usual care N = 29 during salvage chemotherapy ‐ up to 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | EORTC QLQ 30 erythropoietin = +18.9 (18.1) usual care = +39.4 (18.1) | |

| Notes | Large loss to follow up. Oxford Quality Score 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Granetto 2003.

| Methods | Open label | |

| Participants | Any tumour type undergoing chemotherapy N = 510 Male 270 Female 240 average age 61.6 | |

| Interventions | Erythropoetin 10,000 u 3 x week N = 255 erythropoietin 150 u/kg 3 x week N = 255 up to 18 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Single item fatigue scores | |

| Notes | Not suitable for further analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Hedenus 2003.

| Methods | Double blind placebo controlled | |

| Participants | Lymphoproliferative tumours N = 344 Male 166 Female 179 average age 64.6 | |

| Interventions | Darbopoetin 2.25 mcg/kg every three weeks N = 176 placebo N = 173 for 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | FACT F by baseline scores <24 darbopoetin +8.5 (5.0) placebo 5.4 (3.0) 25 to 36 Darbo1.5 (1.1) placebo ‐0.2 (1.1) >36 darbo ‐1.3 (1.5) placebo ‐3.5 (1.5) | |