Abstract

Background

The use of educational and behavioural interventions in the management of chronic asthma have a strong evidence base. There may be a role for educative interventions following presentation in an emergency setting in adults.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of educational interventions administered following an acute exacerbation of asthma leading to presentation in the emergency department (ED).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group trials register. Study authors were contacted for additional information. Searches are current to November 2009.

Selection criteria

Randomised, parallel group trials were eligible if they recruited adults (> 17 years) who had presented at an emergency department with an acute asthma exacerbation. The intervention of interest was any educational intervention (for example, written asthma management plan).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We assessed the quality of evidence using recommendations developed by the GRADE working group.

Main results

Thirteen studies met the eligibility criteria of the review, randomising 2157 adults. Education significantly reduced future hospital admissions (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.91, high quality evidence); however, the estimated reduction in risk of re‐presentation at ED following intervention was imprecise and did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.11, low quality evidence). Symptom control improved following education. The lack of statistically significant differences between asthma education and control groups in terms of peak flow, quality of life, study withdrawal and days lost were hard to interpret given the low number of studies contributing to these outcomes and statistical variation between the study results. Two studies from the USA measured costs: one study from the early 1990s measured cost and found no difference for total costs and costs related to physician visits and admissions to hospital. If data were restricted to emergency department treatment, education led to lower costs than control. A study from 2009 showed that associated costs of ED presentation and hospitalisation were lower following educational intervention.

Authors' conclusions

Our findings support educational interventions applied in the emergency department as a means of reducing subsequent asthma admissions to hospital. Whilst the direction of the effect on ED presentations was consistent with the reduction in risk of admission, the results were not definitive.. Outcomes were measured on average at 6 months after index ED presentation. The impact of educational intervention in this context on longer term outcomes relating to asthma morbidity is unclear. Priorities for additional research in this area include assessment of health‐related quality of life, lung function assessment, exploration of the relationship between socio‐economic status and asthma morbidity, and better description of the intervention assessed.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Humans; Patient Education as Topic; Acute Disease; Asthma; Asthma/prevention & control; Asthma/therapy; Emergency Service, Hospital; Emergency Service, Hospital/statistics & numerical data; Patient Admission; Patient Admission/statistics & numerical data; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Self Care

Plain language summary

Education interventions for adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma

Self‐management and education plans are widely recommended for treating chronic asthma; however, despite endorsement of this intervention acute asthma continues to affect a large number of adults globally. We reviewed evidence from randomised trials that assessed an educational intervention given after presentation in the emergency setting by adults over 17 years old. Thirteen trials involving 2157 people were included. The studies suggested that following the intervention there was a reduction in the frequency of future hospital admissions; however, the effect on visit to the emergency department was imprecise and the results of our analysis indicate that this was a chance result. Education may be an effective reinforcement strategy in reducing future hospital admission following emergency department attendance, but there was little evidence to suggest that it improved other indicators of chronic disease severity such as lung function and quality of life.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Educational interventions for adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma.

| Educational interventions for adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma Settings: Community Intervention: Education | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | educational interventions | |||||

|

Hospital admission/re‐admission Follow‐up ‐ median: 24 weeks (range 4 to 78 weeks) |

Study population | RR 0.5 (0.27 to 0.91) | 572 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 259 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 (70 to 236) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 271 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (73 to 247) | |||||

|

Presentation at emergency department Follow‐up ‐ median 24 weeks (range 8 to 78 weeks) |

Study population | RR 0.72; (0.47 to 1.11) | 946 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 244 per 1000 | 175 per 1000 (115 to 270) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 245 per 1000 | 176 per 1000 (115 to 272) | |||||

|

Quality of life (SGRQ) ‐ Total scores

SGRQ units. Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: mean 6 months |

The mean Quality of life (SGRQ) ‐ Total scores in the intervention groups was 2.17 lower (9.34 lower to 5 higher) | 356 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias (‐1): The design of some of the studies put the results at some risk of bias. A sensitivity analysis which removed studies at a high risk of selection bias gave a result that was closer to unity. 2 Imprecision (‐1): The confidence interval around the pooled effect estimate is compatible with both a small increase and large reduction in the risk of ED re‐presentation.

3 Inconsistency (‐1): Only two studies contributed data and there was some discordance between their effect sizes on the total domain of the SGRQ (I square: 77%)). 4 Imprecision (‐1): The number of studies is low for this outcome and the pooled result requires replication.

Background

Acute asthma presentations to emergency departments are common, can be severe, and may lead to hospitalisations. Despite many systematic reviews regarding the medical management of asthma exacerbations, hospitalizations and re‐presentations appear common. The frequency of acute asthma presentations has stimulated research into whether initiating non‐pharmacological measures to reduce future use of healthcare in this context is useful and appropriate (Boudreaux 2003). Hospital admissions are a strong marker of severe asthma, increased risk of readmission, and death (Martin 1995; Mitchell 1994). There is evidence to suggest that many hospital admissions could be prevented if individuals with asthma were to use an asthma action plan, had improved knowledge of asthma, adhered to their preventive treatment, initiated medication early during an asthma attack, and sought medical assistance early if their condition was not improving (Ordoñez 1998). While emergency physicians feel asthma education is important, they feel unprepared to deliver it and under extreme time pressures (Emond 2000). Consequently, educational interventions need to be proven efficacious and cost‐effective in order to be adopted in this frenetic environment.

Two Cochrane reviews in adults have addressed the role of educational and behavioural interventions in asthma. Gibson 2002a focuses on 'information only' education programs. While this review reported such interventions were effective, only one study reported a reduction in emergency room visits; the other studies reported no impact on unscheduled physician visits, lung function, admissions, medication use, or lost workdays. However, a positive effect upon patient perceived asthma symptoms was detected; one study found a cost savings attributable to the education; three studies found a positive change in knowledge in the intervention group, while two studies found no difference. Gibson 2002c focused on 'self‐management' education interventions for adults with asthma. Asthma self‐management education provides individuals with the skills and resources necessary to effectively manage their illness. These programs include information such as preventing asthma exacerbations, communicating with health care professionals, and attack management (Clark 1993). Significant reduction in hospital admissions, emergency room visits, lost work/school days, and unscheduled physician visits were identified. The five trials that addressed self‐management versus physician managed asthma found no difference in hospitalizations, emergency room visits, physician visits, nocturnal asthma, and one study found a difference in lost work days (self‐management group benefited).

The population to be addressed in this review has unique characteristics and possibly different learning needs than those previously described. While considerable literature has been published addressing self‐management education for individuals with chronic asthma there is not a general consensus on its effectiveness, particularly concerning patients in the emergency department (Bernard‐Bonnin 1995). There is research which suggests that even limited education (information only) may be effective if initiated in the emergency department setting where patients' asthma is often severe (Bolton 1991; Madge 1997). This review is being conducted to summarize the results of literature evaluating the effect of asthma education given to adult patients while attending the emergency department, and to determine whether this education results in positive health outcomes for individuals with asthma.

Objectives

The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the literature in order to determine whether asthma education provided to adults while attending the emergency department for asthma exacerbation management leads to improved health outcomes. A secondary aim is to identify the characteristics of the asthma education programs that had the greatest positive effect on health outcomes. To our knowledge, no previous systematic review has been completed on this topic.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), of parallel group design.

Types of participants

Adults (> 17 years of age) who have attended an emergency department or equivalent setting for the treatment of an asthma exacerbation (defined by doctor's diagnosis or objective criteria). Studies in which there are some participants under the age of 17 have been included (on the assumption that such studies are unlikely to be considered in a paediatric setting), and sensitivity analyses have been used to assess whether this characteristic affects the findings of the review (see ′Methods′ of the review).

Types of interventions

Any educational intervention targeted at adults individually or as a group. The educational intervention may take place in the emergency department, the hospital, the home or in the community, occurring within one week of the emergency room visit. The intervention could involve a nurse, pharmacist, educator, health or medical practitioner associated with the hospital or referred to by the hospital. The intervention may include information, counselling, a change in therapy, the use of home peak flow or symptom monitoring or a written action plan or all three.

The control should consist of usual care following presentation or admission with acute asthma.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Hospital admission/re‐admission rate

Subsequent emergency department visits

Secondary outcomes

Primary care practitioner visits

Lung function: fixed expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR)

Symptoms

Use of rescue (or reliever) medications

Quality of life (using a validated tool for respiratory disease), functional health status

Days home sick (lost from school, child care)

Cost

Withdrawals/loss to follow up

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trials were identified using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see the Airways Group Module for further details). The current review includes a search of the Register to November 2009.

All records in the register coded as 'asthma' were searched using the following terms:

(emerg* or acute* or admi* or exacerb* or status* OR severe* or hospital*) AND (educat* or instruct* or self‐manag* or "self manag*" or self‐care or "self care")

The Register contains studies published in foreign languages, and we did not exclude trials on the basis of language. If necessary, attempts were made to translate the articles from the foreign language literature.

Searching other resources

In addition, we checked reference lists of each primary study and review article to identify additional potentially relevant citations. We also contacted the primary authors of included studies regarding other published or unpublished studies. Finally, we contacted colleagues, collaborators and other investigators working in the field of asthma to identify potentially relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (ST and TL) screened and sorted studies identified by the above search strategy based on the title, abstract and key words (see below).

Include: definitely a RCT; participants > 17 years recruited following emergency room attendance; and received an asthma education intervention.

Possible/unclear: appears to fit inclusion criteria but insufficient information available to be certain, review of the methods necessary to verify inclusion.

Exclude: definitely not a RCT; participants not > 17 years; not recruited following emergency room attendance; or intervention is not asthma education

The complete article was retrieved for studies in categories 1 and 2. Two review authors (ST and TL) independent ly assessed these articles for eligibility using objective criteria. Inter‐rater agreement was calculated using simple agreement. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third review author.

Data extraction and management

TL and ST independently extracted data, including the characteristics of included studies (methods, participants, interventions, outcomes) and results of the included studies. Any discrepancies between the data extracted by the review authors were discussed and resolved between study team authors. Data were entered into the Cochrane Collaboration software (Review Manager 5) by TL, with random checks on accuracy by ST.

Some additional quality variables were also recorded: Follow up ‐ Withdrawals/dropouts, intention to treat analysis.

Other ′Characteristics of included studies′ I) Demographics: age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status.

ii) Type of intervention

Who delivered it (e.g.: nurse, asthma educator, primary care provider);

What was delivered (e.g.: written action plan, modification of drug therapy, peak expiratory flow or symptom monitoring or both, information only);

To whom delivered (adults, families, both); and

When was the intervention delivered in relation to the emergency department visit.

iii) Type of control:

Usual care (which may or may not involve a degree of education);

Waiting list control or lower intensity educational intervention.

iv) Setting of intervention

This is referring to the place the intervention was actually delivered: e.g.: hospital, home, or community setting.

v) Duration of intervention

Number of sessions;

Total hours of teaching.

vi) Sample size

vii) Asthma severity

viii) Number of previous emergency department visits

ix) Intermediate outcomes: asthma knowledge, skills

x) Previous asthma education

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the studies against 6 sources of bias recommended in the Cochrane Handbook. Our judgements (low, unclear and high risk of bias) reflected our assessment of the credibility of the results of the study in light of each particular aspect:

Allocation generation: measures taken to prevent the allocation sequence being manipulated or predicted.

Allocation concealment: measures taken to prevent foreknowledge of the treatment group assignment

Blinding: measures taken to blind study assessors as to the group assignment. Participants and investigators were unlikely to have been concealed

Completeness of follow‐up: whether and how incomplete data were handled in the analysis of study

Selective reporting: whether there was evidence of outcome reporting bias in the study reports

Free of other bias: whether there was any other aspect of the design of the study which may have biased the results of the study.

Dealing with missing data

With one exception we approached authors of the included studies if we could not use data from their studies in our primary outcomes. Following contact with the editorial base initiated by the lead author of Smith 2008 we would like to clarify that the original correspondence with regard to this study was incomplete and inaccurately described in previous versions of this review. A subsequent comment posted by the lead author has provided us with details regarding the outcome of long‐term ED presentation and other detailed information about the study design.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For pooled results, heterogeneity was tested using the I‐squared (I2) statistic (Higgins 2003). Low heterogeneity was defined as I2< 25%; moderate heterogeneity was defined as I2 = 25‐75%; high heterogeneity was defined as I2 > 75%;

Data synthesis

Numerical data were entered and analysed using Review Manager 5. For individual studies, continuous variables were reported as mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where studies have included more than one active intervention group and a control group, we have included the data from both treatment groups by aggregating the means and SDs, and combining the event data for dichotomous outcomes. If appropriate, continuous variables were pooled using mean differences (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs. For dichotomous variables, a relative risk (RR) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated for individual studies; RR and 95% CI were reported for the pooled results using a random‐effects model, which assumes that there is an underlying distribution of treatment effects represented by the different studies. For estimates of RR, a NNT(benefit) or NNT (harm) was calculated (www.nntonline.net).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The following subgroup analyses were planned provided there were sufficient studies within subgroups:

Type of participants ‐ the number of prior admissions may have an impact on how effective an education programme is in reducing further asthma morbidity. If data were available we subgrouped studies (or participants from studies where this information was available) according to hospital admission history (one versus more than one admission to hospital with asthma).

Type of intervention ‐ each of the variables (who delivered the intervention, what was delivered, to whom was it delivered and when it was delivered) were tested to determine if there were any associations with the magnitude of the effect found.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses as needed to determine the robustness of the findings under different assumptions. Analyses include the effect of the following variables on the results:

Risk of bias (removal of studies at a high risk of selection bias)

Statistical model (random versus fixed‐effect modelling).

Studies where participants under the age of 17 were recruited were removed from the analyses to determine the robustness of the effect.

Summary of Findings tables

We summarised the quality of evidence on an outcome by outcome basis using methods developed by the GRADE working group and tabulated our assessments alongside relevant statistical meta‐analysis results and estimates of the absolute effect.

We selected the following outcomes to feature in the Summary of Findings table:

Hospital admission

ED re‐presentation

Quality of life

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

From electronic literature searches to November 2009, a total of 669 references were identified. Of these, 66 unique studies were identified and retrieved for further scrutiny. Five of these references are ongoing trials identified through clinical trials registration searching.

Included studies

The review includes 13 randomised controlled trials which met the review entry criteria. For full details of included studies, see Characteristics of included studies.

Participants

A total of 2157 adults who had presented with an exacerbation of asthma were recruited to the studies. When data on gender were reported it was evident that the majority of study participants across the trials were female. Although presentation with acute asthma featured as an entry criterion in all the studies, there was some variation between the studies as to how participants were identified and when they were recruited to the trials. This occurred either within the emergency department/hospital setting (Baren 2001; Bolton 1991; George 1999; Godoy 1998; Maiman 1979; Morice 2001; Osman 2002; Perneger 2002; Shelledy 2009; Smith 2008; Yoon 1993), or was conducted subsequent to a recent presentation with acute asthma at an emergency setting (Brown 2006; Levy 2000).

Interventions

Type and duration of education

Overall, these educational interventions could be described as ′mixed′. That is, each program contained some combination of interventions. Interventions conducted as part of the education programs were classified according these five important groups (see Table 2). In one study (Godoy 1998), there was a 24 hours asthma hotline included to the education intervention.

1. Type & content of intervention.

| Study | Written self‐management plans | Education on symptoms and triggers control | Information booklet or card | Teaching of use of medication and inhalers (including peak flow meters) | Emphasizing importance of follow up |

| Baren 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ✓ | ‐ | ✓ |

| Bolton 1991 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ✓ |

| Brown 2006 | ✓ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| George 1999 | ‐ | ✓ | ‐ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Godoy 1998 | ‐ | ✓ | ‐ | ‐ | ✓ |

| Levy 2000 | ✓ | ✓ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Maiman 1979 | ✓ | ‐ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Morice 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Osman 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ‐ |

| Perneger 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Shelledy 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ‐ | ✓ | ‐ |

| Smith 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Yoon 1993 | ✓ | ‐ | ‐ | ✓ | ‐ |

Most education sessions were conducted by asthma or ED nurses except in two studies where they were given by respiratory specialists and a physiotherapist (Perneger 2002), and a respiratory therapist (Shelledy 2009).The average timing for follow up was 7.4 months (range 6 to 18 months). Shelledy 2009 assessed both the content and delivery of intervention by including two active treatment groups (with similar education delivered by a nurse and a respiratory therapist) against a usual care group.

Timing of education

Educational interventions were given at different times either at post discharge (Bolton 1991; Brown 2006; Levy 2000; Perneger 2002; Shelledy 2009; Yoon 1993), during hospitalisation (George 1999; Morice 2001) or ED visits for exacerbation (Godoy 1998; Osman 2002; Smith 2008), or at discharge (Baren 2001; Maiman 1979).

Control groups

Usual care was cited as the control group treatment in all the studies. There was some variation between the intensity and frequency of active intervention offered to the control groups. In Smith 2008 the intervention differed from the usual care group by the theoretical model by which education was delivered. The control group received educational intervention that was similar in content to actively treated participants, but active intervention included more open‐ended questions in order to promote autonomy, in line with self‐determination theory. George 1999 also included some education as part of a routine discharge process in the control group, and control group participants from Morice 2001 received an interview with a nurse specialist within 48 hours of admission.

Outcomes

The principal outcome of interest to this review was reported in all the studies as either presentation to an emergency setting or re‐hospitalisation during follow up. However, the different endpoints reported as primary outcomes within each study suggested that there was some variation in the aims of each intervention that the trialists assessed. Baren 2001 and Godoy 1998 cited scheduled clinic attendance as the primary outcome, indicating that the aim of intervention in these studies was to encourage and enhance follow up. Morice 2001 reported the results of the two treatment groups as the preferred action on deterioration of symptoms, suggesting that the primary aim of the intervention was to help study participants seek appropriate medical assistance in the event of an asthma attack. Levy 2000 and Perneger 2002 measured diary data and in this respect the study was primarily concerned with the effect of education on chronic management of asthma. In the remaining studies readmission/re‐presentation at an acute setting was cited as the primary outcome.

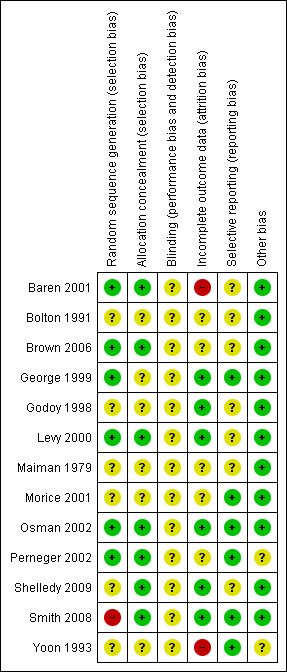

Risk of bias in included studies

We applied judgements according to our protocol across the five sources of bias assessed across six items outlined above. The risk of bias across the six items within the studies varied (see Figure 1).

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged allocation sequence generation and allocation concealment to be at a low risk of bias for five studies (Baren 2001; Brown 2006; Levy 2000; Osman 2002; Perneger 2002). Following information received via comments posted on the review for Smith 2008 we considered the sequence generation to be at a high risk of selection of bias, but measures attempted to conceal the treatment group assignment from the study personnel were at a low risk of bias. Of the remaining studies either one of these items was unclear in two studies (George 1999; Shelledy 2009); both were unclear in Bolton 1991; Godoy 1998; Maiman 1979; Morice 2001; Yoon 1993).

Blinding

The risk of detection in these studies for those participating in the studies was high. Some study reports outlined procedures for masking study personnel during data collection (Bolton 1991; Levy 2000; Osman 2002; Shelledy 2009).

Incomplete outcome data

Follow‐up and adequate analysis of randomised participants was mixed. In five studies the intention to treat principle was applied, completion rates were high, or audit data were verified for all participants (Godoy 1998; Levy 2000; Osman 2002; Shelledy 2009; Smith 2008).

In two studies we considered that follow‐up procedures left the study results at a high risk of bias (Baren 2001; Yoon 1993). In the remaining six studies the basis on which the analysis of data was undertaken could not be ascertained.

Selective reporting

Data for our primary outcomes were provided by nine of the 13 included studies.

Other potential sources of bias

Whilst there were low participation rates in some of the studies, we cannot be certain by whether and by how much this might impact on the results of the studies overall.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

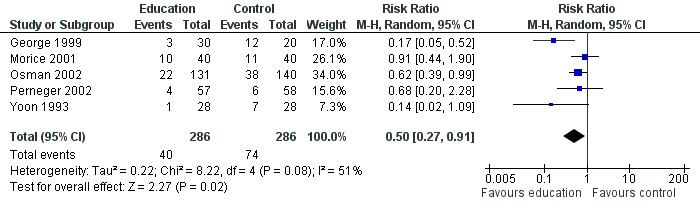

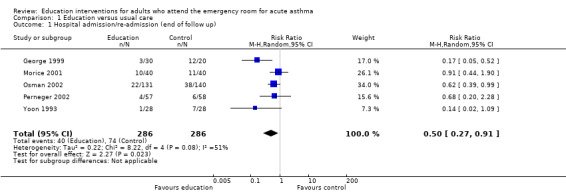

Hospital admission

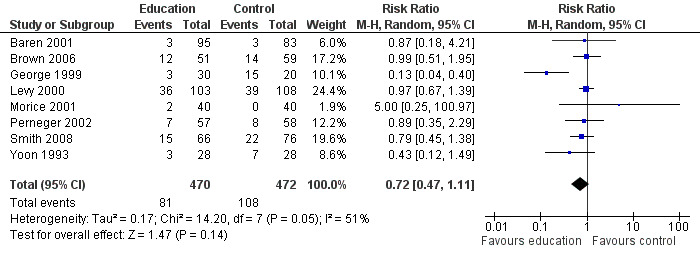

Educational interventions led to a reduction in the risk of subsequent hospital admission (ps (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.91, five studies, N = 572. Figure 2). This was high quality evidence (see Table 1). Based on an assumed risk of admission of 27% in untreated populations, risk of admission would fall to 13%. Most of the evidence comes from studies measuring outcome at 24 weeks. There was a moderate level of statistical heterogeneity for this outcome (I2 = 42%).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Education versus usual care, outcome: 1.1 Hospital admission/re‐admission

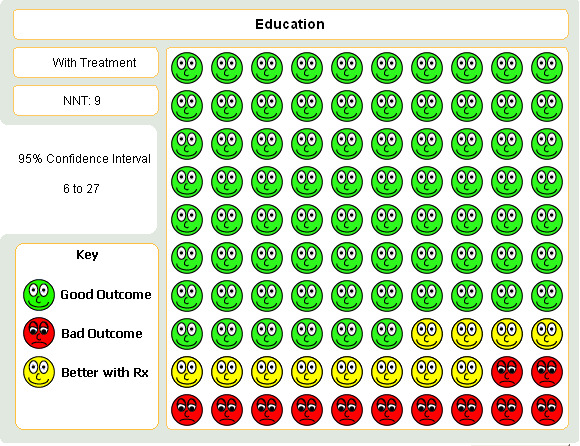

The varying degree of risk in the control groups (seeTable 3) means that a NNT based on a pooled control group event rate might be strongly influenced by the higher rate of re‐admission in the control group in George 1999. In lower risk patients (that is, where baseline risk of re‐admission was around 10%) the NNT is 20; in patients with a risk of between 25 to 28% of re‐admission, the NNT is 8, and amongst the highest risk of admission (60%) the NNT is 4. Overall, this translates into an average NNT(benefit) of nine (95% CI 6 to 27, seeFigure 3). This estimate assumes a control group event rate of approximately 25%, and is derived from clinical trials which followed up patients for between six and 18 months.

2. Control group re‐admission rate.

| Study | N | % re‐admitted | NNT(benefit) | Follow up (w) |

| George 1999 | 20 | 60 | 4 (3 to 19) | 24 |

| Morice 2001 | 40 | 28 | 8 (5 to 40) | 72 |

| Osman 2002 | 140 | 27 | 8 (6 to 42) | 52 |

| Perneger 2002 | 58 | 10 | 20 (14 to 112) | 24 |

| Yoon 1993 | 28 | 25 | 8 (6 to 45) | 40 |

3.

Graph to demonstrate that for every 100 people who undergo an educational intervention having presented with an acute asthma exacerbation, around 9 would have to be treated in order that one person would not be admitted to hospital.

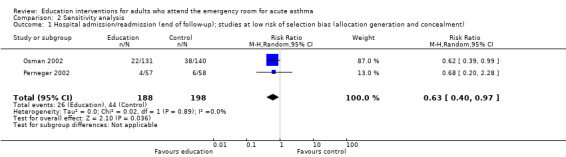

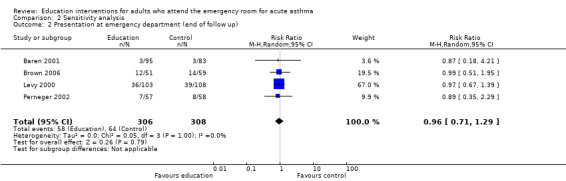

A sensitivity analysis on the basis of low risk of selection bias produced a statistically significant and homogenous result (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.97; I2 = 0%, Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 1 Hospital admission/readmission (end of follow‐up); studies at low risk of selection bias (allocation generation and concealment).

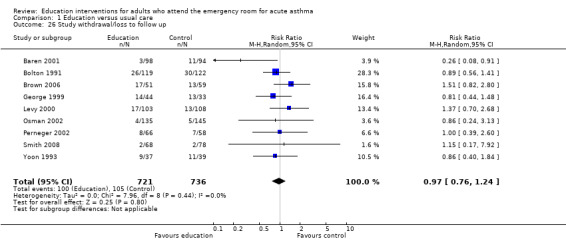

Presentation to the emergency department to the end of follow‐up

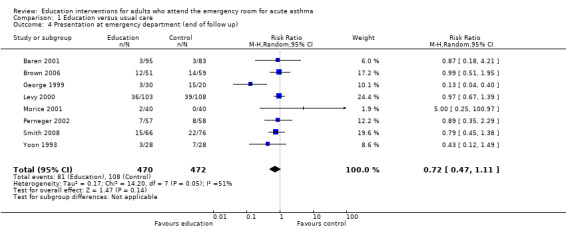

From eight studies involving 946 participants, there was no significant difference on the number of people who re‐presented at an emergency department setting between education and control groups (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.11); Figure 4). We observed a moderate level of statistical heterogeneity for this outcome (I2 = 55%). This was low quality evidence due to statistical imprecision and risk of bias.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Education versus usual care, outcome: 1.4 Presentation at emergency department (end of follow up).

A sensitivity analysis which restricted the results to those studies at the lowest risk of selection bias gave a result that was closer to 1 (i.e. no difference) and demonstrated no statistical heterogeneity between the results (RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.29, Analysis 2.2; I2 = 0%).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 2 Presentation at emergency department (end of follow up).

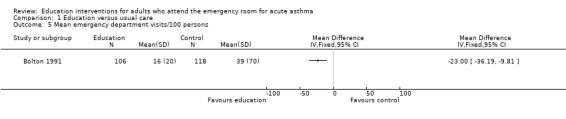

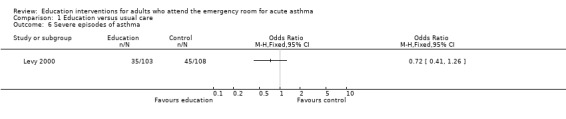

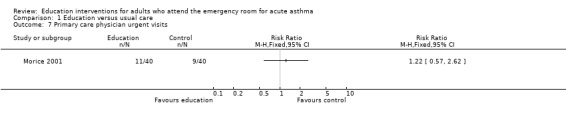

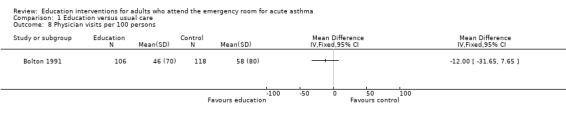

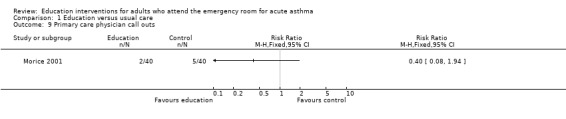

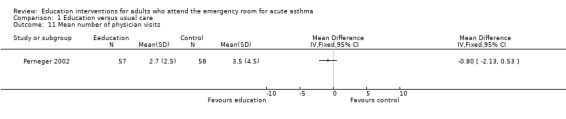

Individual clinical trial data indicated no significant difference in mean hospitalisations for asthma per 100 persons at 12 months; mean length of hospital stay (days); mean emergency department visits/100 persons; physician visits per 100 persons (Bolton 1991); physician visits (Perneger 2002); severe episodes of asthma (including sleep disturbance, GP urgent visits, presentation at emergency department) (Levy 2000); and primary care physician urgent visits or call outs (Morice 2001).

Secondary outcomes

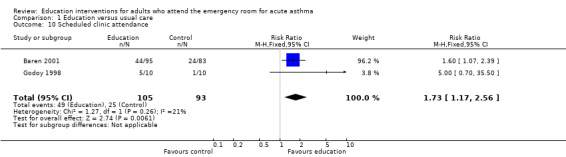

Scheduled clinic attendance

Educational intervention led to a greater likelihood of scheduled outpatient follow‐up appointment in two studies (RR 1.73; 95% CI 1.17 to 2.56) involving 198 participants.

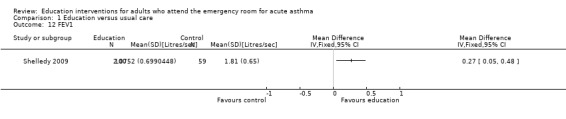

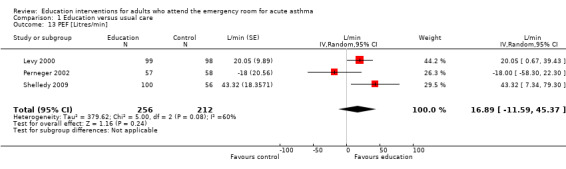

Lung function

From three studies there was no significant PEF difference between education and control groups (16.89 L/min; 95% CI ‐11.59 to 45.37). There was a high level of heterogeneity observed for this outcome (I2 = 60%). The variation between the studies included type of education and delivery.

Symptoms

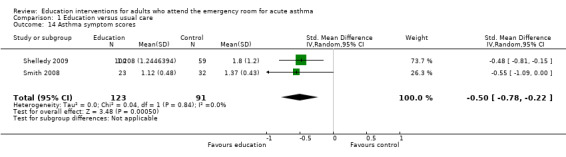

We analysed data from two studies for this outcome (Shelledy 2009; Smith 2008). Education led to improved symptoms, with a SMD of ‐0.50 (95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.22, N = 214).

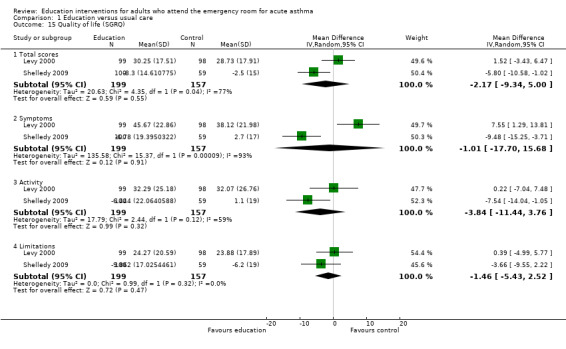

Quality of life

Data from Shelledy 2009 and Levy 2000 were collected for the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). The results failed to identify a difference between education and control in terms of the domains for the SGRQ. When combined the results showed high level of statistical heterogeneity across the symptoms and activities sub‐domains. The data on symptoms are particularly noteworthy as the study effect estimates are in opposite directions (Analysis 1.15). Levy 2000 reported a significant difference in favour of control at six months (of approximately six units). The reason for this apparent difference is difficult to assess, but could be related to an increased awareness of symptoms as a result of enhanced knowledge of asthma and self‐management in the intervention group.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 15 Quality of life (SGRQ).

Days lost from school/work and functional impairment

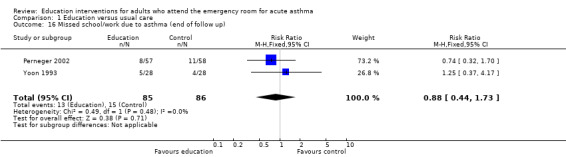

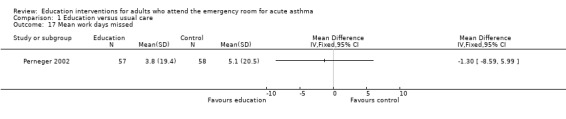

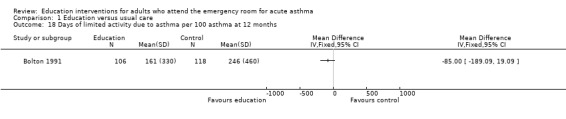

From two studies involving 171 participants, there was no significant difference in the number of participants experiencing days lost from school/work between the groups (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.44 to 1.73). One study reported no significant difference in mean days of limited activity per 100 persons (Bolton 1991), and a further trial reported no significant difference in mean work days lost during treatment (Perneger 2002).

Number of participants experiencing symptoms

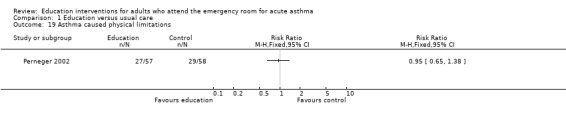

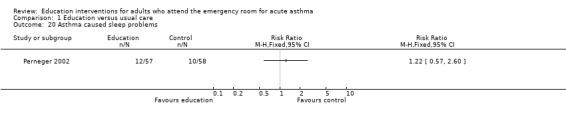

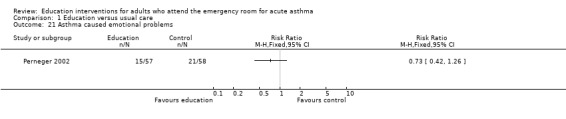

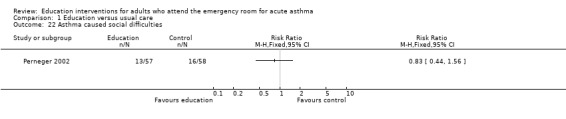

Perneger 2002 reported no significant difference between education and control in the number of participants experiencing sleeping problems, physical limitations, emotional problems and social difficulties; however, there were few studies contributing to these results.

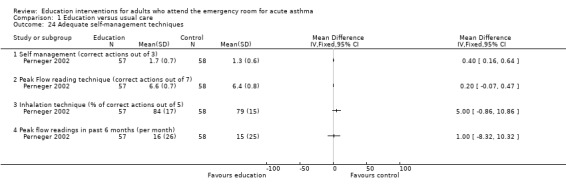

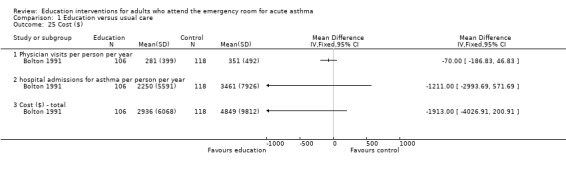

Cost

One US study published in 1991 reported estimated costs of treatment (Bolton 1991). This was significantly lower in favour of education in terms of cost of emergency department visits per person per year ($638). The differences were not significant for physician visits, hospital admissions and total costs. Shelledy 2009 reported that patients allocated to educational interventions incurred lower costs as represented by ED visits and costs of hospitalisation.

Withdrawals/loss to follow up

From eight studies involving 1311 participants, there was no significant difference between the groups with respect to study withdrawal or loss to follow up between education and control (RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.74 to 1.26).

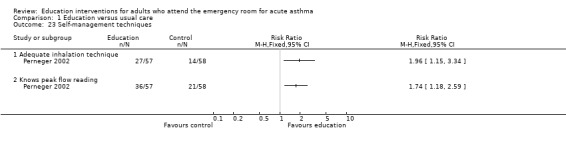

Effects of education on self‐management techniques

Perneger 2002 reported that significantly more patients were able to demonstrate adequate inhalation technique and were aware of their peak flow reading following education compared to the control groups. When data were measured in terms of performance of correct actions, however, there was no significant difference between the treatment groups for outcomes relating to mean number of correct actions observed for inhalation technique, peak flow reading technique and the frequency of peak flow in the previous six months.

Discussion

This systematic review includes 13 studies addressing the efficacy of educational interventions administered to adults following an index visit to the emergency department with asthma. From 2157 participants enrolled in these studies, the results demonstrated that educational interventions given in or after the ED visit to adult patients with acute asthma can decrease the risk of hospital re‐admissions, improve scheduled appointment attendance, reduce costs of emergency departments visits, and improve correct use of self‐management techniques. There was no significant effect of these educational interventions on decreasing the number of ED visits during follow up, improving control in PEF, reduction in days absent from school/work, increasing of the quality of life, and decreasing the number of participants experiencing symptoms.

The effect observed on the primary outcome translates to a reduction in the absolute risk of readmission of approximately 12%, although the admission rates in the control groups did indicate variation in baseline risk (seeTable 3). The results of sensitivity analysis also require some consideration. Common elements to the content of intervention delivered by the high quality studies include written asthma plans and education on symptoms and triggers of asthma. Education was also delivered by specialists in follow‐up sessions in these studies (Osman 2002; Perneger 2002; Shelledy 2009). The number of ED visits did not demonstrate significant results in favour of intervention in eight of the 13 studies, although the point estimate and most of the confidence intervals suggest that there may be a beneficial effect. We need to be rather cautious about the presence of a positive effect on ED presentation in view of the results of the sensitivity analysis (Analysis 2.2).

A significant decrease in ED visits by the same magnitude as that in hospital admissions would mean a decrease of direct and indirect costs involved. The lack of statistical significance on re‐presentation to the ED may be interpreted in several ways. First, the confidence interval only just includes unity, with the majority of the estimate located in favour of a reduction in ED visits. This implies that ED visits can be reduced, and simply more studies are required to prove this. Alternatively, when viewed in conjunction with the reduction in admissions to hospital it could indicate that whilst education does not affect the frequency of visits to the emergency setting, it may lead to earlier presentation during the course of an episode by improving recognition of the onset of acute asthma, and promoting early treatment of deteriorating asthma that leads to hospital admission (Kelly 2002).

Written personalised action plans when given as part of a self‐management intervention improve health outcomes for adults with asthma (Cote 2001; Gibson 2002a; Gibson 2002c; Gibson 2002b; Lahdensuo 1996). The Canadian Consensus Asthma Guidelines recommends that a written action plan for guided self‐management, usually based on an evaluation of symptoms, must be provided for all patients (Becker 2005). Despite this advice there has until now been very little evidence that this is being done. The asthma education programmes for adults described here contained education sessions, visual material and more. According to the British Guideline on Management of Asthma, successful programmes vary considerably, but encompass:

structured education, reinforced with written personal action plans, though the duration, intensity and format for delivery may vary;

specific advice about recognizing loss of asthma control, though this may be assessed by symptoms or peak flows or both;

action to take if asthma deteriorates, including seeking emergency help, commencing oral steroids (which may include provision of an emergency course of steroid tablets), and recommencing or temporarily increasing inhaled steroids, as appropriate to clinical severity. Many plans have used a 'zoned' approach (BTS 2003).

Although this review has not attempted to explore barriers to widespread use of action plans, the significant effects observed should be viewed cautiously, particularly if low uptake of self‐management plans are a contributory factor to presentation at emergency departments (Douglass 2002; Walters 2003). Adults may have limited opportunities to attend educational sessions in practice due to work and childcare commitments, and the format, content and uptake of educational intervention still requires quantitative and qualitative evaluation (Zayas 2006).

There are several limitations of this review. First, there was heterogeneity between the intensity and frequency of educational intervention. The characteristics of the interventions were described in varying degrees of detail. It is difficult to determine the relative effectiveness of the individual elements of the educational interventions, and whether there are specific characteristics that lead to successful outcome. Additional variables which could affect the degree of success of this class of intervention include prior asthma education, baseline level of educational attainment and socio‐economic status. This was hard to assess formally within the review. Second, among the 13 studies, 25 different outcomes were measured and many of the outcomes are reported in only one study, preventing formal statistical aggregation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review provides evidence which supports the use of educational interventions to reduce readmission following an episode of acute asthma in adults. Whilst the direction of the effect on ED presentations was consistent with the reduction in risk of admission, the results were not definitive. This review does not provide evidence to suggest that other important markers of long‐term asthma morbidity are affected. Although we observed high levels of statistical heterogeneity in re‐admissions, the result was sufficiently robust for us to conclude that there was evidence of a beneficial effect across the studies. These results were ascertained at around 6 months post intervention across the majority of studies contributing to these outcomes.

The evidence to date regarding the cost‐effectiveness is sparse and the decision to implement an educational intervention is currently based predominantly on evidence of effectiveness.

Implications for research.

Studies are required to provide information on the following sources of uncertainty surrounding educational interventions.

Efficacy Are the findings of this review repeatable? In particular, what are the effects of treatment on health‐related quality of life, symptoms and lung function?

Educational intervention intensity The intensity of the intervention may present a barrier to the widespread uptake of post‐ED education, particularly where resources are scarce and continuation contingent on accommodation of a course of education in the routine of daily life.

Educational intervention format We have pooled data from studies where different combinations of various educational elements have been used in an intervention. Better reporting of the intervention provided, and how it can be delivered are required from future trials

Confounders of effect The impact of socio‐economic status of patients on access and continuation with these interventions.

Cost‐benefit of educational interventions In an era of diminishing resources available for additional services, there is an urgent need for studies which examine the cost‐effectiveness of individual components of educational interventions.

Feedback

Additional information on included study Smith 2008, 12 April 2013

Summary

1. I did not receive a request from the update authors for further information on Smith 2008. Assessment of this study in the 2010 update of this review may therefore be inaccurate, and could be misleading to readers.

2. Details of concealment and blinding to intervention are detailed in a stepwise process below:

Medical officer gives permission for PhD student to see patient and patient asked if they would like to participate in study after they had read the information on the study.

Patient’s ‘sticky’ label from their chart, that has all the patient details, is then placed in study book after consent is signed in the patient’s room. All ED rooms are single person bays.

Group assignment placed next to sticky label in study book and study book placed immediately into student’s brief case whilst patient and clinical staff were not present.

Date of birth was not recorded anywhere and study book was keep in locked filing cabinet separate to questionnaires.

All signed consent forms without group assignment are placed in the brief case and transported back to the university where they are stored in a locked cabinet – separate to the questionnaires.

Envelopes with the questionnaires and asthma pamphlet used in the education are stored in the student’s brief case in readiness for study participants and there are no markings on the A4 white envelopes.

Patient takes questionnaire out of envelope and completes questionnaire and then it is placed back in the envelope is sealed along with the completed clinical data of FEV1 FVC from beside chart and envelope is placed in the brief case. Identifier is only placed on the front page of the questionnaire as the last action before the questionnaire is placed back in the envelope just prior to immediate sealing and then is taken back to university where it is stored in locked cabinet.

Data from questionnaires were entered onto database ‐ date of birth was not recorded.

Clinical staff would not be able to identify any details of patient assignment to group as the process looked exactly the same for both groups.

Education is given as per the patients selected order (PCE) or in the standard order (SPE).

Education given was ‘word perfect’ for both groups as it is read from an Asthma Australia pamphlet.

Asthma pamphlet is then given to the patient to take home.

If any clinical staff heard the education it would sound the same as it was being read off the pamphlet

All patients knew they were going to receive asthma education and they received the same information and the PCE was a patient determined order which was the intervention (and patients didn't know). Patients in the control group would have thought they were receiving what everyone else was receiving and vice versa.

3. As per Smith 2008 ERJ publication in the methods section under study design (p991), the primary aim was ED re‐attendances at 4 & 12 months and improvement in asthma control after education in ED

4. The number of people experiencing one or more emergency department visits at four and 12 months from each arm of this study has been provided for the review authors.

Reply

We would like to thank Sheree Smith for submitting this clarification that contrary to what we had reported about the correspondence process in the last version of this review, we did not request outcome data from the 2008 publication of her study. The provision of information about the study design and outcome data has enabled us to revise our bias assessments and the results of our analysis.

Having now had an opportunity to consider the information provided, we have upgraded our assessment of the concealment of allocation and selective outcome reporting accordingly. We have used the 12 month data in ED attendance in our analysis, and revised the Summary of Findings table and abstract accordingly.

Contributors

Professor Sheree Smith.

Family & Community Health Research Group, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Western Sydney, Australia.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 April 2013 | Feedback has been incorporated | Comment posted on the review by Sheree Smith relating to Smith 2008. Outcome data, risk of bias and study details revised. Clarification made over the correspondence process for obtaining data. |

| 18 April 2013 | Amended | New data and information added to the table of study characteristics, risk of bias table and the analysis of ED presentation for Smith 2008. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 November 2009 | New search has been performed | Literature search re‐run. One new study met the review eligibility criteria. One study initially included as an abstract has now been published in full. Restructured outcomes list. Summary of Findings table added. Conclusions are unchanged. |

| 23 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 April 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to the staff of the Cochrane Airways Group editorial base, namely Emma Welsh, Elizabeth Arnold, Susan Hansen, Chris Cates and Veronica Stewart for providing extensive support with literature searching and editorial comment. We would like to extend our gratitude to Sheree Smith for contacting us to point out that the reporting of our correspondence with her was inaccurate in previous versions of this review. She has supplied information about her study via the feedback mechanism regarding study design and outcome data which has contributed to us revising our appraisal of her study in this review.

Dr. Rowe's research is supported by a 21st Century Canada Research Chair from the Government of Canada (Ottawa, ON).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Education versus usual care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hospital admission/re‐admission (end of follow up) | 5 | 572 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.27, 0.91] |

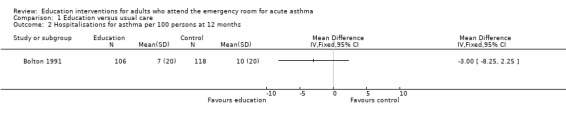

| 2 Hospitalisations for asthma per 100 persons at 12 months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

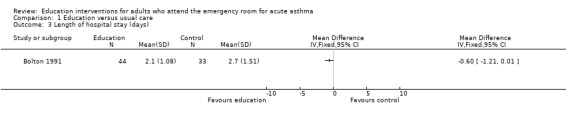

| 3 Length of hospital stay (days) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Presentation at emergency department (end of follow up) | 8 | 942 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.47, 1.11] |

| 5 Mean emergency department visits/100 persons | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Severe episodes of asthma | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Primary care physician urgent visits | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Physician visits per 100 persons | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Primary care physician call outs | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Scheduled clinic attendance | 2 | 198 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [1.17, 2.56] |

| 11 Mean number of physician visits | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12 FEV1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 13 PEF [Litres/min] | 3 | 468 | L/min (Random, 95% CI) | 16.89 [‐11.59, 45.37] |

| 14 Asthma symptom scores | 2 | 214 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.50 [‐0.78, ‐0.22] |

| 15 Quality of life (SGRQ) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 Total scores | 2 | 356 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.17 [‐9.34, 5.00] |

| 15.2 Symptoms | 2 | 356 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.01 [‐17.70, 15.68] |

| 15.3 Activity | 2 | 356 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.84 [‐11.44, 3.76] |

| 15.4 Limitations | 2 | 356 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.46 [‐5.43, 2.52] |

| 16 Missed school/work due to asthma (end of follow up) | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.44, 1.73] |

| 17 Mean work days missed | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 18 Days of limited activity due to asthma per 100 asthma at 12 months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 19 Asthma caused physical limitations | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 20 Asthma caused sleep problems | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 21 Asthma caused emotional problems | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 22 Asthma caused social difficulties | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 23 Self‐management techniques | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 23.1 Adequate inhalation technique | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 23.2 Knows peak flow reading | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 24 Adequate self‐management techniques | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 24.1 Self management (correct actions out of 3) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 24.2 Peak Flow reading technique (correct actions out of 7) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 24.3 Inhalation technique (% of correct actions out of 5) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 24.4 Peak flow readings in past 6 months (per month) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 25 Cost ($) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 25.1 Physician visits per person per year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 25.2 hospital admissions for asthma per person per year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 25.3 Cost ($) ‐ total | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 26 Study withdrawal/loss to follow up | 9 | 1457 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 1 Hospital admission/re‐admission (end of follow up).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 2 Hospitalisations for asthma per 100 persons at 12 months.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 3 Length of hospital stay (days).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 4 Presentation at emergency department (end of follow up).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 5 Mean emergency department visits/100 persons.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 6 Severe episodes of asthma.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 7 Primary care physician urgent visits.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 8 Physician visits per 100 persons.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 9 Primary care physician call outs.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 10 Scheduled clinic attendance.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 11 Mean number of physician visits.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 12 FEV1.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 13 PEF [Litres/min].

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 14 Asthma symptom scores.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 16 Missed school/work due to asthma (end of follow up).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 17 Mean work days missed.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 18 Days of limited activity due to asthma per 100 asthma at 12 months.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 19 Asthma caused physical limitations.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 20 Asthma caused sleep problems.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 21 Asthma caused emotional problems.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 22 Asthma caused social difficulties.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 23 Self‐management techniques.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 24 Adequate self‐management techniques.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 25 Cost ($).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus usual care, Outcome 26 Study withdrawal/loss to follow up.

Comparison 2. Sensitivity analysis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hospital admission/readmission (end of follow‐up); studies at low risk of selection bias (allocation generation and concealment) | 2 | 386 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.40, 0.97] |

| 2 Presentation at emergency department (end of follow up) | 4 | 614 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.71, 1.29] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baren 2001.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: North America, single centre. DURATION OF STUDY: 8 weeks COMPLIANCE: Not assessed CONFOUNDERS: Even distribution between groups in terms of baseline lung function, age, sex and maintenance therapies. |

|

| Participants | N SCREENED: 197 N RANDOMISED: 192 N COMPLETED: 178 M = 64/F = 128 MEAN AGE: 31 BASELINE DETAILS: Ethnicity: Asian: 7; Black: 146; Hispanic: 3; White: 18; Insurance: Government/HMO: 40%; Government/military: 4%; HMO: 22%; Private: 22%; None: 13%. PEFR: 246 l/min; respiratory rate: 21.3; Inhaler use in previous 24 hrs (puffs): 4.7 INCLUSION CRITERIA: Aged between 16‐46 years; attendance at emergency department with symptoms of acute asthma EXCLUSION: Admission to hospital; unable to speak English; unwilling/unable to provide informed consent |

|

| Interventions | Education group: On discharge, participants were provided with a pack containing oral steroids, transportation vouchers to attend a primary care follow up; asthma information card; written instructions on use of vouchers and medication. Attempts made to contact all intervention group participants to remind them to attend a primary care follow up. Control group: Participants discharged with short course of oral steroids; further instructions and medication at discretion of discharging physician FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: Participants were followed up for two months. |

|

| Outcomes | Scheduled attendance at primary care physician/clinic; relapse (re‐presentation at ED within 21 days of discharge); withdrawal/loss to follow‐up. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated block randomisation schedule |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Prepared by third party. 'Study packages were prepared and sealed by 2 investigators not involved in patient enrolment.' |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study participants aware of treatment group assignment. Information on study outcome assessor blinding not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Differential loss to follow‐up. 11/93 in control group withdrew versus 3/94 in intervention group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Could not determine this reliably |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Bolton 1991.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: North America, Two sites (urban and suburban emergency departments) DURATION OF STUDY: 12 months. COMPLIANCE: 41% participants randomised to intervention did not attend any of the educational classes. CONFOUNDERS: Slightly higher ER visits for asthma in control group in 6 months prior to study |

|

| Participants | N SCREENED: 537 N RANDOMISED: 241 N COMPLETED: 185/241 M = 122 (82/241)/F = 119 (159/241) MEAN AGE: 37 years BASELINE DETAILS: 13% of sample had been admitted at initial ED visit; Ethnicity: white: 34% (31%); ED visit at inner‐city site: 64%; < 13 years education: 57%; 13‐14 years of education: 32%; > 14 years of education: 11%. Insurance coverage: 93%. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 18‐70 years; Attendance at ED with acute asthma episode. EXCLUSION: Language/psychiatric barrier |

|

| Interventions |

Education group Invitation to attend three small group educational sessions with trained nurse. Participants were reminded of importance of compliance with maintenance therapy, importance of self‐care. Interactive dialogue with emphasis on problem‐solving skills was also undertaken. Education aimed to change behaviour and to teach them about their asthma. Participants received instruction in breathing exercises; practiced inhalation techniques, and received smoking cessation advice if necessary. Those who missed their class received educational material by post. Control group Usual follow up. FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: 12 months. |

|

| Outcomes | Attendance at emergency department; cost; withdrawal. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Block randomisation (randomly chosen block size: 4, 6 or 8) stratified by site |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study participants were aware as to group assignment. 'The follow‐up telephone interviewers were blinded to the patients' group memberships.' |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Data reported for 224/241 participants at 12 months. 185 participants completed the study. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Could not determine this reliably |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Brown 2006.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: USA, one centre. DURATION OF STUDY: 6 months COMPLIANCE: 39% in intervention group did not comply with any aspect of planned educational programme. CONFOUNDERS: Even distribution between groups in terms of baseline lung function, age, sex and maintenance therapies. |

|

| Participants | N SCREENED: 1061 N RANDOMISED: 248 M = 107/F = 128 BASELINE DETAILS: Primary care physician: 87%; Asthma action plan: 23%; Spacer: 57%; ICS: 78%; PEF metre: 44%; 37% were African American, 56% had moderate‐to‐severe persistent asthma, 78% on ICS at baseline. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Children or adults; asthma exacerbation presenting on ED visit, have had asthma symptoms in the prior 2 weeks, or a previous hospitalisation or ED visit in the past year. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Not described |

|

| Interventions |

Education group Conducted by trained asthma educators and included a facilitated office visit with patient and primary care provider within 2‐4 weeks of enrolment, a home‐visit 2‐4 weeks thereafter. Control group Usual follow up. FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: 6 months |

|

| Outcomes | Urgent asthma visit; treatment compliance; withdrawals | |

| Notes | Follow‐up information was obtained from 190 participants. 49% of the 117 intervention participants did not comply with activities Data for adults (> 18 years) presented in trial report were used in the review |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random number sequences |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participants aware as to treatment group assignment. Information on blinding of outcome assessors not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 'Intention‐to‐treat analysis' |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine this reliably. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

George 1999.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: One centre in USA inner city (Philadelphia, PENN). DURATION OF STUDY: 6 months COMPLIANCE: Not assessed. CONFOUNDERS: Comparable groups at baseline in terms of disease severity. | |

| Participants | N SCREENED: 88 N RANDOMISED: 77 N COMPLETED: 77 (data presented from follow‐up based on central records) M = 16 F = 61 MEAN AGE: 29 BASELINE DETAILS: Medicaid: 43; self‐pay: 9; Private: 25. MEAN AGE: 29 years. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 18‐45 years; participants admitted to hospital with acute asthma exacerbation. EXCLUSION: Admission to intensive care; no telephone access; pregnant females,comorbid disease, inability to speak English. | |

| Interventions |

Education group In‐patient education, consisting of repetitive teaching sessions with an asthma nurse, with the aim of improving inhaler technique, recognition of need for long‐term therapy, early warning signs of asthma and action plan in response to them. Asthma nurse also screened for obstacles to care including lack of transportation to OPD, lack of childcare or substance abuse. Social worker collaborated in order to remove/address barriers where possible. Follow‐up telephone call 24 hours post‐discharge was also made. An appointment was arranged for treatment group participants at an outpatient clinic within 7 days of discharge. Control group Usual discharge routine (education, PEF measurements, discharge planning and scheduled follow‐up at discretion of nursing and house staff). Both groups received usual treatment for the exacerbation of their asthma (including iv methylprednisone and nebulised SABA) FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: Six months |

|

| Outcomes | Length of hospital stay; successful discharge; scheduled follow‐up visit; subsequent ED use. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random number generator. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participants aware as to treatment group assignment. Information on blinding of outcome assessors not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Available case, but for key outcomes data were obtained from central records. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Review primary outcome measured, analysed and disclosed in full. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Godoy 1998.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group. LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: USA, inner city hospital. DURATION OF STUDY: 4‐8 week follow up. COMPLIANCE: Assessed as attendance at a clinic. CONFOUNDERS: Not sufficient detail reported. |

|

| Participants | N SCREENED: Not reported. N RANDOMISED: 20 N COMPLETED: 12/20 (available for telephone interview at 4‐8 weeks) M = Not reported/F = Not reported MEAN AGE: Not reported. BASELINE DETAILS: Not reported. Participants completed asthma knowledge questionnaire. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Attending ED for acute asthma, no other criteria were specified. EXCLUSION: Not specified. |

|

| Interventions |

Education group Reinforcement of signs of asthma exacerbation and importance of outpatient care as a means of maintaining long‐term asthma control. Access to a hotline. Control group Usual care FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: Four‐eight weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Attendance at outpatient clinic | |

| Notes | Presented as conference abstract only | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants accounted for. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to ascertain this reliably |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Levy 2000.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group trial. LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: UK, two outer‐London general hospitals. DURATION OF STUDY: 6 months. COMPLIANCE: 57% participants had three education sessions (either in person or by telephone); 63% had two sessions and 77% had one session. CONFOUNDERS: Comparable groups at baseline. " | |

| Participants | N SCREENED: 865 N RANDOMISED: 211 N COMPLETED: 181 M = 80 F = 131 MEAN AGE: 42 BASELINE DETAILS: PEF 47% predicted (in ED). INCLUSION CRITERIA: Presentation at ED with acute asthma. EXCLUSION: Not reported. | |

| Interventions | Education group: 1 hr consultation with specialist nurse two weeks post‐study entry, followed by an additional two consultations of 30 minutes at 6 weekly intervals. Asthma control was assessed, followed by some education on recognising and treating acute asthma. Control group: Usual care. FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: 6 months. |

|

| Outcomes | Peak flow; quality of life (as measured by the St George Respiratory Questionnaire); symptom scores; asthma attacks. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated equal blocks of 4 from randomly generated number sequence. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'The nurses had no idea which group the patients would be randomised into, however, once randomised they became aware in order to proceed and invite intervention group patients to attend.' |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participants aware as to treatment group assignment. 'An interviewer, blinded to the patients randomisation status, conducted four structured telephone interviews using the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire and an assessment questionnaire...' |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants accounted for. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Cannot ascertain this reliably. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Maiman 1979.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group trial. LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: One centre in USA (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore). DURATION OF STUDY: 6 months COMPLIANCE: Not assessed. CONFOUNDERS: Baseline characteristics of the groups not presented. | |

| Participants | N SCREENED: 538 N RANDOMISED: 289 N COMPLETED: 289 (data presented on 245) M = 58 F = 187 MEAN AGE: 34.4 years BASELINE DETAILS: African American: 226. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 18‐64 years of age; presentation to ED with acute asthma; visit termination interview conducted by a nurse. EXCLUSION: > 65 years. | |

| Interventions |

Education group 1a Exit interview from nurse who identified herself as asthmatic; positive written appeal (booklet containing information on what happens during an asthma attack, use medications and how they prevent attacks, coping strategies for asthma attacks, environmental control advice). Education group 1b Exit interview from nurse who identified herself as asthmatic; no booklet. Education group 2a Exit interview from nurse who did not identify herself as asthmatic; positive written appeal (booklet containing information on what happens during an asthma attack, use medications and how they prevent attacks, coping strategies for asthma attacks, environmental control advice). Education group 2b Exit interview from nurse (as above) who did not identify herself as asthmatic; no booklet. Education group 3a Exit interview from ED nurse; positive written appeal (booklet containing information on what happens during an asthma attack, use medications and how they prevent attacks, coping strategies for asthma attacks, environmental control advice). Education group 3b Exit interview from ED nurse; no booklet. All participants received follow‐up telephone call. FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: 6 months |

|

| Outcomes | Subsequent presentation at ED with asthma symptoms. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | (3 x 2) x 2 x 2 factorial design |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study participants aware as to treatment group assignment Information on blinding of outcome assessors not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Information not available (assumed available case). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine this reliably. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Morice 2001.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group trial LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: UK, large teaching hospital DURATION OF STUDY: 18 months DESCRIPTION OF WITHDRAWALS/DROPOUTS: 10 out of 40 in the control group and 5 out of 40 in the intervention group did not return responded to the questionnaire TYPE OF ANALYSIS (AVAILABLE CASE/TREATMENT RECEIVED/ ITT): Intention‐to‐treat analysis COMPLIANCE: Not assessed CONFOUNDERS: Not mentioned | |

| Participants | N SCREENED: 80 N RANDOMISED: 80 N COMPLETED (at 6 months): 65 M = 53 F = 27 MEAN AGE: 36.1 years CHARACTERISTICS: Prior use of ICS at 1 mg: 47.5% INCLUSION CRITERIA: admitted on the general medical take to a large teaching hospital with a documented primary diagnosis of acute asthma EXCLUSION CRITERIA: chronic obstructive respiratory disease, previously participated in an educational programme from a hospital‐based asthma nurse, unable or unwilling to complete a series of follow‐up questionnaires | |

| Interventions | Education group: subsequent visits of the asthma nurse until discharge from hospital. A minimum of 2 sessions of 30 minutes each; 1)discussion about mechanisms, triggers and booklet 2) summary of first session, self‐management plan peak flow meter+instructions and Sheffield Asthma Card with emergency phone numbers and, 3) last visit where patients were encouraged to express fears or anxieties related to their home management Control group: usual care Both groups: seen by the asthma nurse as a single interviewer within 48 hours of admission FOLLOW‐UP PERIOD: 18 months |

|

| Outcomes | Preferred action taken on worsening of asthma symptoms (GP urgent visits, GP call‐outs, accident and emergency visits, re‐admissions); withdrawal/loss to follow up | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study participants aware as to treatment group assignment Information on blinding of outcome assessors not clear |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 10 out of 40 in the control group and 5 out of 40 in the intervention group did not return responded to the questionnaire. Analysis described as intention‐to‐treat. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Review primary outcome measured, analysed and disclosed in full. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias could be identified. |

Osman 2002.

| Methods | STUDY DESIGN: Parallel group trial. LOCATION, NUMBER OF CENTRES: Single centre in Scotland, UK. DURATION OF STUDY: 12 months COMPLIANCE: Assessed via questionnaire report (81% returned at 1 month). CONFOUNDERS: At 12 months the differences between the 2 groups of patients remained greater for those for whom this had been a first admission. At one month return of questionnaire may be motivated by satisfaction with treatment. |

|