Abstract

Background and Objectives

Only a fraction of the 53 million caregivers in the United States use available formal community services. This scoping review synthesized the literature on the barriers and facilitators of community support service utilization by adult caregivers of a family member or friend with an illness, disability, or other limitation.

Research Design and Methods

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science for quantitative and qualitative articles assessing barriers and facilitators of caregivers’ access to and utilization of resources, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis scoping review guidelines. Thematic analysis, drawing on an initial conceptualization, informed key insights around caregivers’ resource navigation process.

Results

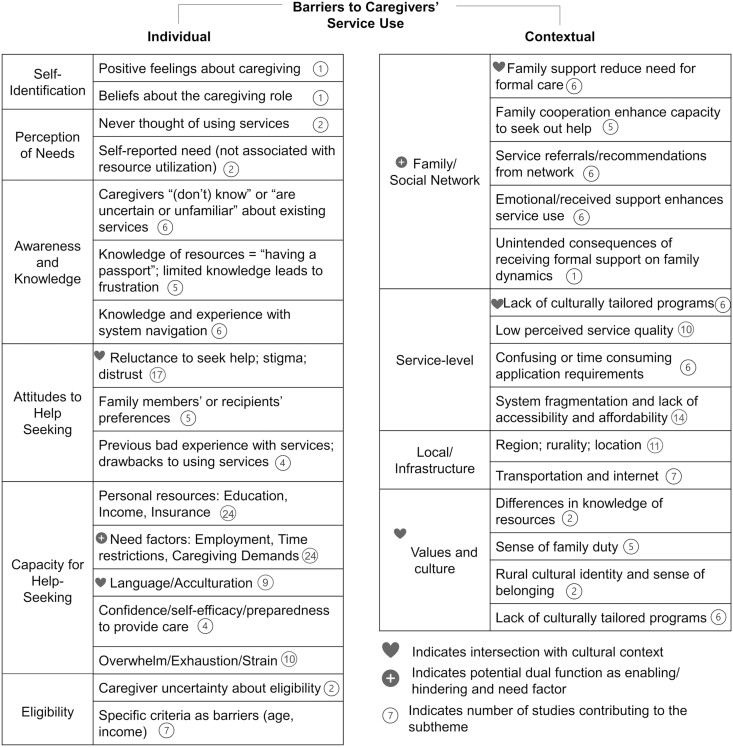

The review provides support for individual factors affecting service use. Notably, some factors—such as time restrictions and increased caregiving demands—appear to function as barriers to accessing services even as they increase caregivers’ need for support. Additionally, contextual barriers including cultural factors and support of friends/family can affect caregivers’ access to resources. Finally, experience with health systems and structures and the intersection with other factors can affect service utilization.

Discussion and Implications

Suboptimal access to and utilization of community support services can be addressed at both the person and system level to mitigate potential inequities. Ensuring that caregivers are aware of, eligible for, and have the capacity and support to access the appropriate resources at the right time is essential for improving caregiver outcomes, reducing burnout, and supporting continued care.

Keywords: Caregiving—informal, Health care policy, Home and community-based care and services, Social services

Background

Caregivers play a critical role in supporting the health and well-being of family members or friends with illness, disability, or other limitations, providing more than $470 billion worth of care annually (Reinhard et al., 2019). Although caregiving occurs across the life span, more than two-thirds of care recipients are older than age 65 (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP Public Policy Institute, 2020). Although caregiving is often rewarding, caregivers face numerous challenges, such as elevated stress, emotional and physical health problems, and financial burden. Extensive research suggests caregivers with adequate support have lower levels of burden (Del-Pino-Casado et al., 2018). Moreover, those who receive community support services report providing better care and continue providing care for longer than would otherwise be possible (Administration for Community Living, 2021).

Support services for caregivers are available through community organizations, health systems, or governmental agencies, and range from respite care and grants for home modifications to transportation support and caregiver support groups. However, caregivers often report barriers to accessing and effectively utilizing high-quality services, with the result that only a fraction of the 53 million caregivers in the United States uses the support services that are available to them (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP Public Policy Institute, 2020). Existing research indicates that: many caregivers do not self-identify as such (Aufill et al., 2019; Kutner, 2001); many caregivers are unaware that support services are available for caregivers, or only hear about them by chance (Bruening et al., 2020; Harrop et al., 2014); and complex application processes hinder caregivers’ ability to engage with needed resources (Gardiner et al., 2019; Reinhard et al., 2014). This is especially true for low-income families, suggesting a need to address this disparity in care (Appelbaum & Milkman, 2011; Litzelman & Harnish, 2022; Zebrak & Campione, 2021). This literature, however, is fragmented and would benefit from an overarching conceptualization. Systematically mapping and synthesizing the literature on this topic can identify research and practice gaps and is a crucial step in the development of both person- and systems-level interventions and solutions to address challenges with and inequities in utilization.

Models of Access to and Utilization of Services

Several existing frameworks conceptualize access to and quality of services. Centering on the service-seeker, the Andersen Behavioral Model conceptualizes access as a function of an individual’s predisposing, enabling/hindering, and need characteristics (Andersen, 1995). Predisposing characteristics consist of demographic factors that affect the likelihood of need for services, such as age as well as social factors such as ethnicity and family or social networks and the attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge people hold about services. Enabling/hindering factors include personal and family resources such as income, education, and social relationships as well as organizational and community resources such as the availability of services. Finally, need characteristics consist of both subjective and objective need for services, including health and caregiver burden. In a well-functioning, equitable system, we would expect service use to be largely driven by need. Dominance of predisposing social factors or enabling/hindering characteristics, on the other hand, can indicate inequitable access to services (Andersen et al., 2014). We consider the factors within these categories to be interactive and situated in the context of the social and structural environment.

On the service-provider side, the Five Dimensions of Accessibility Model assesses the availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability of services (Penchansky & Thomas, 1981). This model suggests that appropriate uptake of services will be maximized when there is alignment of the services with the needs and expectations of clients across these five dimensions. Levesque et al. (2013) expanded these concepts to explicitly consider the interface between individual or “demand-side” features with system-level or “supply-side” features across a series of steps that enable individuals to contact and obtain health care.

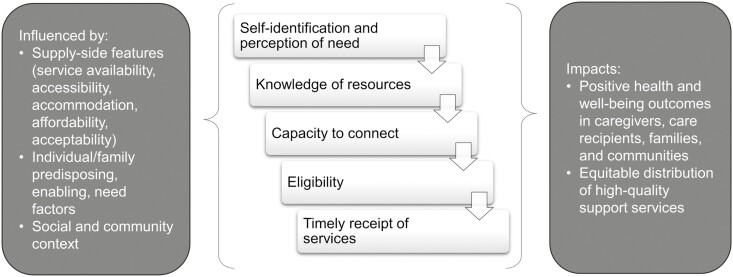

Conceptualizing Access as a Resource Cascade

In existing conceptualizations, access to services is largely considered unidimensional. However, needs assessments of caregivers and service providers (Litzelman & Wisconsin Family and Caregiver Support Alliance, 2019; Wisconsin Family and Caregiver Support Alliance, 2018), as well as conversations with caregiver advocates and stakeholders, have led us to further consider the potential for the process of accessing services to act as a cascade, or a series of sequential steps that individuals must navigate in order to successfully obtain high-quality, timely, tailored services and supports. Eisenberg and Power (2000) used the metaphor of “voltage drops” to describe how the potential for high-quality health care can be undermined by numerous stepwise barriers, illustrating that access to health insurance is not sufficient to ensure the receipt of high-quality health care. Drawing on the models described above, caregivers’ access to and utilization of supports and resources can be similarly deconstructed into multiple steps that contribute to overall access and quality (Figure 1). Integrating these frameworks, service-seeker (“demand-side”), and service-provider (“supply-side”) factors as outlined by Andersen, Penchansky, and Levesque and their colleagues (including social and structural factors such as family/informal support networks or social determinants of health and service coordination across medical, public health, and social services systems) can be considered as acting independently and interactively on multiple steps across a resource access cascade. Importantly, an individual’s predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics do not exist in a vacuum, but interact with each other and with social and structural factors. This integrated conceptualization can support policy, systems, or environment changes that reflexively pinpoint and respond to local challenges to supporting caregivers. Later we describe steps in a potential resource cascade and elucidate how social determinants of health can affect each stage.

Figure 1.

Conceptualization of caregivers’ access to and utilization of community support services.

In order to receive caregiving-specific supports and services, individuals must first recognize themselves as caregivers. Self-identification has been acknowledged as a key impediment to uptake of caregiver supportive services (Aufill et al., 2019), although empirical assessment of this phenomenon is sparse. For example, family members often see the caregiving work they do as an extension of their relational role (O’Connor, 2007). Among older adults providing the kind of help consistent with a family caregiving role, slightly more than half self-identified as a caregiver (Kutner, 2001). Often, the role of “child” or “spouse” is not perceived as requiring the level of outside support as “caregiver.” Thus, role identification can inhibit support-seeking and can lead to caregivers feeling overwhelmed and burnt out. Similarly, individuals must perceive a need for support related to their caregiving role. Structural and social factors such as gender, geography, and culture potentially predispose or enable individuals to such perceptions.

Next, caregivers must have awareness of support services. Many caregivers are unaware of caregiver support programs or indicate that they heard about them only by chance (e.g., Bruening et al., 2020). Caregivers who are not aware of the existence of support programs will be unable to make use of them, particularly in the absence of routine caregiver identification and need assessments by the health care or social services systems. Awareness may be particularly low in disadvantaged subgroups such as low-income households (Appelbaum & Milkman, 2011), those with low health literacy, and across gender and cultural identities. Such disparities have downstream implications for the equitable distribution of resources as marginalized families fall off the cascade.

Caregivers next must have the capacity to engage with the organizations and agencies that provide resources. Capacity can be either logistical or functional, including the time to research or inquire about resources as well as ability to take on the potentially overwhelming and complex task of applying for and coordinating services. This step may further exacerbate inequity. If those with more time, financial, or personal resources have greater capacity to seek and obtain support services, caregivers with potentially the highest burden may be least likely to obtain support. Geography may play a key role at this stage, as availability of services (and therefore the time and resources required to access them) is likely to vary across localities.

Next, eligibility for many caregiving resources is often conditioned on characteristics of the care recipient or caregiver, typically age, health condition, or economic means. Enrolling in services often includes providing ongoing documentation or certification of the care recipients’ health condition(s), their caregiving-related expenses, the family’s income, or other factors. Navigating enrollment paperwork can be a burdensome process for caregivers whose time and emotional capacity are already stretched. Gaps in services can result when high-needs caregiving populations fall outside of existing eligibility requirements or when caregivers deem that the value of the service is not commensurate with the burdensomeness of the enrollment processes.

Finally, effective caregiver support services must be rendered in the right dose and at the right time. Institutional capacity plays a key role at this step—if support services are underfunded or understaffed, or lack cultural tailoring, there may be extended wait times, limited services, or lack of relevance that may compromise a program’s effectiveness at supporting caregiver and family outcomes. As noted above, individual and structural factors and social determinants of health have the potential to shape each step in the cascade and the ultimate receipt of wanted and needed support services.

Objective

The purpose of this scoping review is to map the literature on barriers and facilitators to community service utilization for caregivers of adults in the United States, in terms of our initial conceptualization of a resource cascade. Guided by our conceptual model, we identified barriers and facilitators at steps across the process of accessing services. Therefore, we investigated barriers and facilitators that fall under the following domains of our initial conceptualization of the resource cascade: Caregiver’s self-identification, awareness of services, capacity for help seeking, eligibility, and institutional capacity. We also identified emergent constructs from the research evidence. The findings from this scoping review provide a critical framework guiding additional research as well as policy and practice initiatives that seek to provide equitable, timely, culturally appropriate support for caregivers.

Research Design and Methods

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this review is based on the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). The final protocol has been registered with the Open Science Framework (Litzelman et al., 2021).

Study Eligibility Criteria

Population

We include work focused on any adult (18+) caregivers of an adult family member or friend with an illness, disability, or other limitation (including old age or frailty). Although those under 18 may have caregiving responsibilities, they have unique needs from adults and are thus excluded from this review.

Concept

Throughout this paper, community resources, supports, or services are referred to interchangeably, as a reflection of similar usage across the literature. To better elucidate our theoretical model, we focused on studies that directly addressed barriers or facilitators to accessing services. We included papers that examined the use of discretionary formal services in the community, such as adult day care, respite care, caregiver training, and support groups. Studies that assessed only prescribed services (e.g., physical therapy or medically necessary home health care), informal support services (e.g., neighbors helping with housework), generic programs and services (e.g., Medicaid/Medicare), or outcomes of service utilization were beyond the scope and intent of the current review and were excluded. Although clinical interventions (e.g., psychoeducation; pharmacotherapy) and informal support (e.g., social support from family and friends) are both undoubtedly important for shoring up caregiver well-being, we focus on community support services due to their potential for local policy, systems, and environmental impacts. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods evidence were included. Studies were excluded if they were not available in English.

Context

We included peer reviewed papers conducted in the United States after 2000. These limits were selected because of the policy differences across countries and across time that affect access to and utilization of support services. The year 2000 was specifically selected to examine the timeframe following the implementation of the National Family Caregiver Support Programs in the United States, which codified and provided financial support for caregiver-centered programming (Administration for Community Living, 2021).

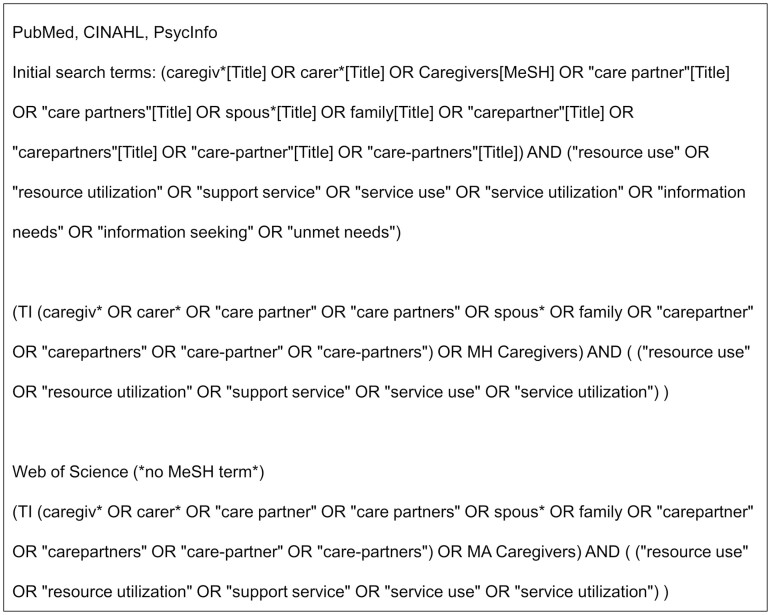

Information Sources

A search was conducted with the electronic databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science (Figure 2). The most recent search was conducted on December 08, 2022.

Figure 2.

Database search queries.

Selection of Sources of Evidence (Study Selection)

Titles and abstracts were each independently reviewed by two of three researchers using Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, 2022). Full texts were then each independently reviewed by two researchers. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion among all three researchers. We conducted quality assessment for included studies using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool Version 2018 (Hong et al., 2018). Two researchers completed the quality appraisal for each study.

Data Charting Process

A data extraction form was developed and pilot-tested in alignment with the study purpose. The three researchers then worked independently to abstract data from included studies; each entry was verified by a second researcher. The following information was extracted: barriers/facilitators to access services, how services were defined within the study, types and measurement of formal services, caregiving contexts (e.g., caregiver’s and care recipient’s demographics, kinship types, and caregiving duration), research framework, and manuscript characteristics (e.g., design, methodology, or limitations).

Synthesis of Results

Thematic analysis of the barriers identified across studies was conducted, drawing on the initial resource cascade model and adding, expanding, and refining themes and subthemes in an iterative process. Where appropriate, we also reported the direction of the association with resource utilization as “positive,” “negative,” or “no relationship.”

Results

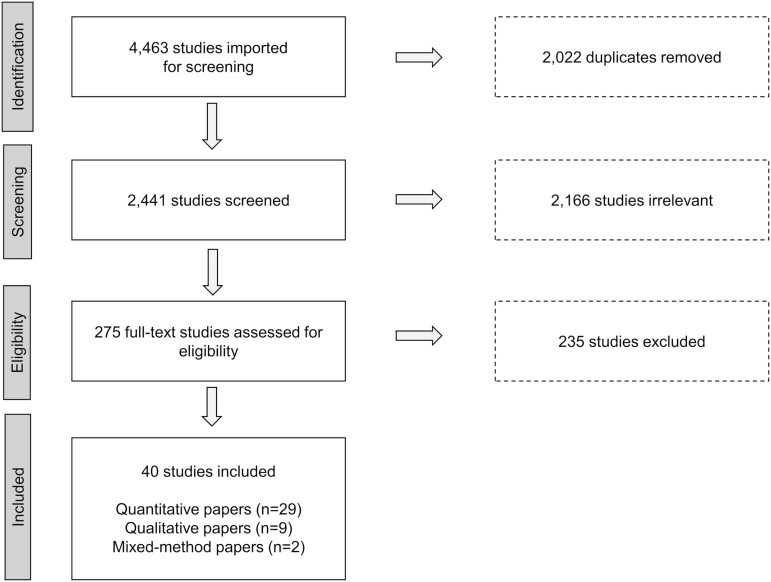

Selection of Sources of Evidence

Initially, the electronic databases identified 4,463 studies. After removing duplicates (n = 2,022) and irrelevant studies (n = 2,166), we screened 275 full-text manuscripts. After full-text review, we excluded 235 manuscripts for the following reasons: They did not directly address access to/utilization of services (n = 136), were not conducted in United States (n = 49), did not directly address barriers (n = 20), sample did not fit inclusion criteria (n = 15), not real-world setting (n = 4), data were collected before 2000 (n = 5), review paper (n = 2), not in English (n = 1), and additional duplicate (n = 3). Overall, 40 manuscripts (29 quantitative, nine qualitative, and two mixed-methods design) were included in this review. These manuscripts represent unique studies, with the exception of two papers that report on different elements of the same data set and sample (Hong, 2010; Hong et al., 2011) and one that reported on qualitative data (Roberto et al., 2022) collected from a subset of participants in a larger quantitative study (Savla et al., 2022). Figure 3 presents the PRISMA flow chart.

Figure 3.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis flow diagram.

Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

Characteristics of studies

Supplementary Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies in this scoping review. In total, 38 studies used a cross-sectional study design and two studies used a longitudinal design. The plurality of studies used convenience or purposive samples. The majority of studies referenced a guiding theoretical framework, with nearly half (n = 19) adapting the original or modified version of the Andersen Behavioral Model.

Sample characteristics

The studies’ samples mostly consisted of female caregivers (range: female 56%–100%; male 0%–44%). Most studies included multiple types of caregivers, primarily spouse/partners, adult children caring for parent or in-law, or parents caring for their adult child. Twenty-three studies recruited or focused on caregivers of care recipients with a specific illness or health condition, most often Alzheimer’s or related dementia (n = 17).

There were variations in the type of service utilization considered across studies. Thirty-six studies measured utilization across multiple services, while four studies only assessed utilization of respite care. Quantitative studies (n = 29) measured patterns of service utilization by creating a dichotomized variable (e.g., any vs no utilization of the evaluated services), calculating frequency as the count of services used, or dividing into subgroups based on the extent of service utilization (e.g., high vs low users). The qualitative studies (n = 9) primarily served to identify barriers and facilitators of service use stemming from the lived experiences of caregivers.

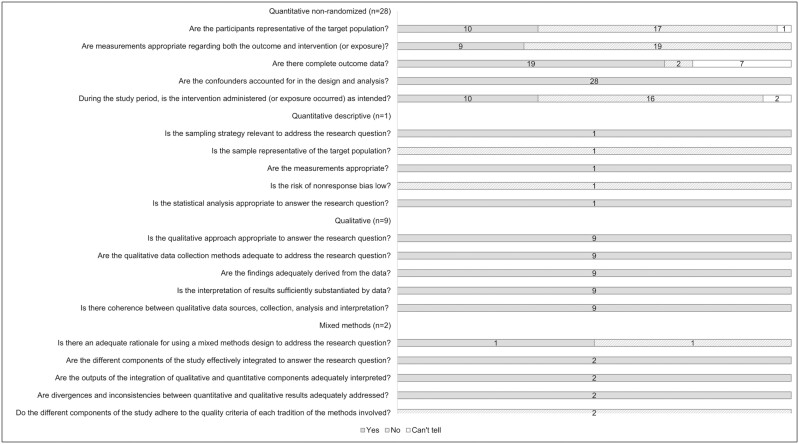

Quality assessment

The included studies varied in quality. We observed that many quantitative studies used over-simplified measures of service utilization assessed over long time frames (e.g., over the past year or since caregiving began), which also introduced potential variation in the exposure that was not explicitly accounted for in the analyses (Figure 4). A detailed quality assessment table is available in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 4.

Results of the quality assessment.

Insights Derived from the Scoping Review

The themes and subthemes identified in this scoping review are depicted in Figure 5. Several key insights emerged from the review. In addition to the initial conceptualization of a resource cascade, several contextual factors—that is, community, social, and structural factors that can affect the steps in the resource cascade—emerged that appeared likely to shape individual experience and outcomes. In particular, cultural heritage and values emerged as important predictors of perceptions of need for services, awareness that resources are available, and perceived acceptability and accessibility of the services. The support of family and friends emerged repeatedly as instrumental in caregivers’ ability to access services, both by increasing capacity to seek out care and by providing information and referrals that provided an entryway into service systems. In addition, we identified several factors that may function simultaneously as enabling/hindering or need factors. Finally, evidence indicated that experience and engagement with the medical system affected caregivers’ utilization of community services, suggesting a need to better understand and shore up alignment of services and resource navigation across systems. A detailed summary of the thematic findings and directionality of associations is available in Supplementary Materials: Section B and Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 5.

Results of the thematic analysis information key insights.

Evidence Across the Resource Cascade

The combined evidence from our review highlights the steps in the initial conceptualization of a resource cascade. Studies suggested that positive feelings about the caregiving role were associated with greater service utilization (Friedemann et al., 2014; Radina & Barber, 2004), while perceived need for services was not (Friedemann et al., 2014; Toseland et al., 2002). Unfamiliarity with services and lack of knowledge around systems navigation were brought up in numerous studies as barriers to service use (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Casado & Lee, 2012; Cotton et al., 2021; Fleming & Litzelman, 2021; Gustavson & Dal Santo, 2008; Herrera et al., 2008; LaValley et al., 2019; Miller & Canada, 2012; Richardson et al., 2019; Roberto et al., 2022; Santo et al., 2007; Scharlach et al., 2006, 2008; Sun et al., 2014; Toseland et al., 2002), which could result in feelings of frustration (Sun et al., 2014). There was mixed evidence for the role of education, employment, income, caregiving demands, and psychosocial well-being, with most quantitative studies pointing toward positive associations (see Supplementary Table 3). Service ineligibility was noted as a barrier in several studies (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Casado & Lee, 2012; Fleming & Litzelman, 2021; Herrera et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2011; Miller & Canada, 2012; Scharlach et al., 2006; Winslow, 2003), with emerging evidence that ineligibility for financial support was associated with lower utilization of services (Litzelman & Harnish, 2022).

One important element was added to our conceptualization of a resource cascade: attitudes toward help seeking. Several studies touched on a general reluctance or hesitation to seek services (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Casado & Lee, 2012; Cotton et al., 2021; Giunta et al., 2004; Gustavson & Dal Santo, 2008; Herrera et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2011; Keith et al., 2009; Kosloski et al., 2002; Miller & Canada, 2012; Moon, 2016; Richardson et al., 2019; Roberto et al., 2022; Scharlach et al., 2006; Watari et al., 2006; Winslow, 2003). Consistent with the conceptualization of Collins et al. (1991), studies identified challenges related to stigma (Sun et al., 2014) or mistrust of service providers or the government (Miller & Canada, 2012; Richardson et al., 2019; Scharlach et al., 2006). Previous bad experiences with services were also mentioned as a factor affecting reluctance to use services (Fleming & Litzelman, 2021; Miller & Canada, 2012; Toseland et al., 2002) as were the preferences of other family members and the care recipient (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Casado & Lee, 2012; Cotton et al., 2021; Giunta et al., 2004; Gustavson & Dal Santo, 2008; Herrera et al., 2008; Watari et al., 2006; Winslow, 2003), although one study found this not to be a factor in resource utilization (Kosloski et al., 2002).

Potential for Increased Need and Decreased Capacity to Access Services

The synthesis of the reviewed studies points toward several factors inhabiting a gray area between Andersen’s need and enabling/hindering factors. Employment, for example, can increase a caregivers’ need (i.e., to provide care during the workday) while also limiting their capacity to engage with and access services due to time constraints (Dionne-Odom et al., 2018; Feldman et al., 2021; Hong, 2010; Hong et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2022; Martindale-Adams et al., 2016; Parker & Fabius, 2020; Santo et al., 2007; Scharlach et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2021). Similarly, greater caregiving demands (such as coresiding with the care recipient, caregiving tasks, or providing more hours of care) are likely to increase a caregiver’s need while simultaneously decreasing the time and emotional energy available to seek out and secure services (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Casado & Lee, 2012; Friedemann et al., 2014; Giunta et al., 2004; Herrera et al., 2008; Hong, 2010; Keith et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2022; Santo et al., 2007; Savla et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2018; Toseland et al., 2002; Young et al., 2002). Although the plurality of reviewed studies show that psychological stress and strain increase resource utilization (and thus appear to be functioning as need factors; Dionne-Odom et al., 2018; Fleming & Litzelman, 2021; Henning-Smith et al., 2019; Hong, 2010; Sun et al., 2007; Toseland et al., 2002; Watari et al., 2006; Winslow, 2003), a few studies suggest that strain was not significantly related to caregivers’ capacity to reach out for service (Lee et al., 2022; Parker & Fabius, 2020). It remains unclear whether these factors act as need and enabling factors simultaneously or function differently in different circumstances, and future research disentangling these potential mechanisms will be valuable.

Cultural Values and Tailoring of Programs

Many of the studies reviewed approached service utilization with a cultural lens (specifically in consideration of shared values, beliefs, and customs of particular groups) or assessed patterns of barriers across multiple racial/ethnic groups (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Calderón-Rosado et al., 2002; Casado & Lee, 2012; Friedemann et al., 2014; Giunta et al., 2004; Herrera et al., 2008; Parker & Fabius, 2020; Radina & Barber, 2004; Richardson et al., 2019; Scharlach et al., 2006, 2008; Sun et al., 2014; Williams & Dilworth-Anderson, 2002; Young et al., 2002). This lens is a critical strength of the literature, as it emphasizes how needs, preferences, knowledge, and pressures differ across cultural backgrounds and identities. Supplementary Material: Section B has a detailed summary of the findings from these studies across ethnocultural identities. Generally, the findings suggest that cultural disparities in awareness and knowledge of resources or mistrust of service providers have the potential to result in inequitable access and utilization of services. Conversely, differences in preferences or perceived need across subgroups may be reflective of appropriate utilization in a cultural context. Importantly, several studies highlighted a lack of culturally tailored programs, or barriers in language and racial/ethnic concordance of providers (Cotton et al., 2021; Giunta et al., 2004; Gustavson & Dal Santo, 2008; Herrera et al., 2008; Scharlach et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2014), as a crucial barrier for many families, presenting an opportunity for improvement for both service providers and policy-makers. Further, few studies took an intersectional lens, limiting our ability to unpack how caregivers’ different identities and personal experiences combine to facilitate or create barriers to accessing caregiving resources.

Family Dynamics and Social Support

Family support appeared to play conflicting roles. Several studies indicated that family support reduced the caregivers’ need for formal support services (Radina & Barber, 2004; Scharlach et al., 2006, 2008; Williams & Dilworth-Anderson, 2002), but family cooperation or sharing of care responsibilities appears to increase caregivers’ capacity to seek out support services (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Herrera et al., 2008; Hong, 2010; Roberto et al., 2022). Social networks also provided crucial referrals to services that facilitated caregivers’ knowledge and access (Cotton et al., 2021; LaValley et al., 2019; Roberto et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2014; Young et al., 2002). However, several studies indicate that family or care recipient resistance to services was a key challenge for caregivers, potentially shaping their attitudes toward service use and affecting their utilization (Abramsohn et al., 2019; Casado & Lee, 2012; Cotton et al., 2021; Giunta et al., 2004; Gustavson & Dal Santo, 2008; Herrera et al., 2008; Miller & Canada, 2012; Moon, 2016; Richardson et al., 2019; Roberto et al., 2022; Scharlach et al., 2006; Watari et al., 2006; Winslow, 2003).

Cross-System Alignment

Caregivers’ access to services appears to be influenced by interfaces across social and structural systems. Alignments with the medical system are a prime example: Studies in this review provided evidence that a delayed care-recipient medical diagnosis presented challenges for access to resources (Cotton et al., 2021). Furthermore, we saw evidence that referrals and recommendations for services, both from informal social networks as well as from medical providers, affected utilization (Cotton et al., 2021; Herrera et al., 2008; Hong, 2010; Hong et al., 2011; LaValley et al., 2019; Roberto et al., 2022; Santo et al., 2007; Scharlach et al., 2006, 2008; Shi et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2014; Williams & Dilworth-Anderson, 2002; Young et al., 2002). This evidence suggests that efforts to optimize access to and utilization of support services will function best when social, public health, and medical systems are aligned and facilitate coreferral and coordination.

Discussion and Implications

This scoping review mapped and synthesized the literature on caregivers’ barriers to utilization of community services in terms of a multistep resource cascade affecting access to services. Our initial conceptualization considered access to and utilization of community services as a series of steps that caregivers must successfully navigate in order to receive high-quality services that meet their needs and produce positive outcomes. The reviewed studies added narrative depth to the initial conceptualization, and also revealed complexity underlying access to and utilization of resources at the individual and population level. Moreover, the review identified several additional key contextual factors (i.e., community, social, and structural factors) that are likely to drive resource utilization as well as gaps that remain understudied in the literature. These findings provide insight to guide research, policy, and practice.

From a research perspective, several gaps and future directions can be gleaned from this review. First, this area is ripe for methodological advances. Longitudinal analyses that are capable of assessing pathways and directionality of associations and facilitate causal inference are critically important to advancing our understanding of and ultimately our ability to affect the drivers of service use. Analytic techniques that capture the complexity and heterogeneity in service utilization (rather than more reductionistic approaches) will be crucial for informing risk stratification, intervention, and policy that is effective in a real-world setting. Second, future research would do well to conceptualize service use as embedded in a complex cultural, family, and life course context. Evidence from this scoping review indicates that cultural elements such as familism, filial responsibility, and the availability of culturally tailored programs, and family elements such as resistance to support services by care recipients or nonprimary caregivers are associated with service utilization. Furthermore, the extant literature overlooks other high-needs populations across the life course such as caregivers of younger adults with disabilities or mental illness or caregivers who are young adults themselves. Future work assessing service utilization in these understudied populations is needed, as is research that employs a broader life course perspective in assessing trends and potential interventions to overcome barriers and optimize service utilization for caregivers.

Another clear gap that emerged from this review was the lack of information about the ways in which social location (defined as the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location; Brown et al., 2019) affects barriers and facilitators to support service utilization in complex, structural ways. For example, socialization to gender roles is theorized to affect how women engage in caregiving behaviors (Kim et al., 2019). Male caregivers as a group may tend to have different perceptions of need and attitudes toward help seeking, and may experience differing intersections between their gender, roles, and identity that influence their preferences and capacity to seek support (Mott et al., 2019). Further exploring the ways in which social locations explain facilitators and barriers to support service utilization is a critical direction for future research and synthesis. Although a significant subset of the reviewed studies examined caregiver support service utilization through a cultural lens, very few applied a gender-role or other social identity lens to understand resource utilization. Synthesizing and articulating the social and structural processes by which such factors influence caregiving behavior and resource utilization will be crucial to advance efforts to address structural biases that maintain patterns of inequitable access.

This scoping review and conceptualization of the drivers of community resource use in family caregivers also have important implications for policy and practice. First and foremost is the potential for the current system to result in inequities in receipt of services based on financial, personal, and social resources. Rather than integrated systems providing services as a default to caregivers, our system demands caregivers expend resources not only to opt in but also even realize that there is something available to opt into. The evidence from this review suggests that those with higher income, more education, fewer time restrictions, and greater internal and external psychosocial resources (including self-efficacy and social support) have greater access to and utilization of support services, suggesting that resources accrue not to those with the highest need but to those with the greatest capacity to seek out and obtain them. Ensuring equitable access to services in the context of complex preferences, lived experiences, and perceived needs of individuals across cultural backgrounds will be a key task of service providers as well as local and state policy-makers who develop and sponsor support programs.

In addition, there is an opportunity to provide education about the role support services can play in supporting the well-being of both a care recipient and the network of caregivers. A family-centered approach may provide a framework for evaluating, discussing, and deciding on the services that meet key needs in the context of social and cultural identities, values, and preferences. Materials and curricula that provide scaffolding for these conversations and subsequent shared decision making are critical to navigating the transitions of caregiving and identifying appropriate resources to meet caregiving needs. Understanding and seeking to change attitudes and misconceptions about help seeking also have the potential to have population-level impacts on service utilization and subsequent caregiver and family well-being.

Policy-makers and community leaders also have the opportunity to consider the potential intersection among individual and systems-level factors in the distribution of community support services to caregivers. Consistent with Levesque et al.’s consideration of the drivers of health service utilization (Levesque et al., 2013), this review revealed evidence of both “demand-side” (i.e., caregiver’s needs, preferences, and behaviors) and “supply-side” (i.e., system fragmentation and accessibility at the service and local infrastructure levels) barriers to utilization. Embracing a complex view of these systems navigation challenges, and the social and structural elements that contribute to them, can support the implementation of locally relevant policies and initiatives that address both classes of barriers as well as their intersections.

Finally, the findings point to the need for strategic and systematic integration of services and information across systems. It is clear that barriers exist to caregivers routinely receiving services they often need and want. Policy-makers, advocates, and community organizations have mandated the development of a coordinated family caregiving strategy. The national caregiver strategy, published in late 2022, includes recommendations for adoption of community support services, ranging from respite care, financial or workplace support, caregiver training, or support groups (Administration for Community Living, 2022). However, while this report, and the legislation that led to its development, demonstrates a recognition of the importance of caregivers, to date few health care systems are equipped to even identify caregivers in the electronic medical record as standard of care (Applebaum et al., 2021), much less provide them with key resources and services.

Limitations

It is important to interpret this review, and its findings, in light of the methodological boundaries as well as the potential limitations of the included studies. In particular, given that the majority of the studies were cross-sectional in nature, alternative interpretations must be considered. For example, it is difficult to ascertain whether income functioned as a facilitator (increasing the caregivers’ capacity to access resources) or is instead an outcome of resource use (e.g., showing that services were effective at allowing for increased work time and thus income) and thoughtful consideration is encouraged. Although this review was limited to studies in the United States, studies in other countries reflect similar challenges with systems navigation and accessing services (e.g., Macleod et al., 2017). Additionally, although several studies focused on specific minoritized groups, the majority of studies focused on caregivers who were White, older, women, caring for a spouse or parent. Other factors may be important to consider in resource use by specific minoritized or understudied populations. Finally, although we hold that gender, ethnicity, and other social locations are often integral in explaining barriers and facilitators to formal service access, the existing literature on resource utilization has not thoroughly unpacked these interrelationships and intersectionalities. Future work is needed to articulate the complex social and structural processes by which such factors affect the barriers and facilitators to service utilization.

Conclusion

Given the increasing trend toward outpatient and home-based care by family caregivers, it is important to provide appropriate, high-quality, and timely resources for caregivers to ensure they are able to effectively engage in their role. In this review paper, we found diverse barriers at individual, family, service, and cultural levels that influence caregivers’ access to and utilization of resources. Our findings imply that it is necessary to understand caregiver resource utilization with an ecological view, including how these various levels can intersect and interact within the context of care. Overall, our findings provide insights for additional research and opportunities for policy to improve accessibility to resources, ultimately increasing both caregiver’s and care recipient’s well-being.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Hyojin Choi, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, School of Human Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Maija Reblin, Department of Family Medicine, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, USA.

Kristin Litzelman, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, School of Human Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA; Center for Demography of Health and Aging, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the UW-Madison Center for Demography of Health and Aging (P30 AG17266).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Data Availability

Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP). Extraction materials and results are available upon request. The scoping review protocol was preregistered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/df6mk/).

References

- Abramsohn, E. M., Jerome, J., Paradise, K., Kostas, T., Spacht, W. A., & Lindau, S. T. (2019). Community resource referral needs among African American dementia caregivers in an urban community: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1341-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Administration for Community Living. (2021). National Family Caregiver Support Program. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers/national-family-caregiver-support-program

- Administration for Community Living. (2022). 2022 National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers. Retrieved December 23, 2022, from https://acl.gov/CaregiverStrategy

- Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R. M., Davidson, P. L., & Baumeister, S. E. (2014). Improving access to care. In G. F. Kominski (Ed.), Changing the US health care system: Key issues in health services policy and management (4th ed., pp. 33–69). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, E., & Milkman, R. (2011). Awareness of California’s paid family leave program remains limited, especially among those who would benefit from it most: New results from the September 2011 field poll. http://cepr.net/documents/publications/pfl-2011-11.pdf

- Applebaum, A. J., Kent, E. E., & Lichtenthal, W. G. (2021). Documentation of caregivers as a standard of care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39(18), 1955–1958. doi: 10.1200/jco.21.00402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aufill, J., Burgdorf, J., & Wolff, J. (2019). In support of family caregivers: A snapshot of five states. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/MMF_Caregiver_Report_6.19.pdf

- Brown, T. L., Bryant, C. M., Hernandez, D. C., Holman, E. G., Mulsow, M., & Shih, K. Y. (2019). Inclusion and diversity committee report: What’s your social location? Highlights from the special session at the 2018 NCFR Annual Conference NCFR Report. National Council on Family Relations Report, 64(1), 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bruening, R., Sperber, N., Miller, K., Andrews, S., Steinhauser, K., Wieland, G. D., Lindquist, J., Shepherd-Banigan, M., Ramos, K., Henius, J., Kabat, M., & Van Houtven, C. (2020). Connecting caregivers to support: Lessons learned from the VA caregiver support program. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(4), 368–376. doi: 10.1177/0733464818825050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Rosado, V., Morrill, A., Chang, B.-H., & Tennstedt, S. (2002). Service utilization among disabled Puerto Rican elders and their caregivers: Does acculturation play a role? Journal of Aging and Health, 14(1), 3–23. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado, B. L., & Lee, S. E. (2012). Access barriers to and unmet needs for home- and community-based services among older Korean Americans. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 31(3), 219–242. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2012.703540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C., Stommel, M., King, S., & Given, C. W. (1991). Assessment of the attitudes of family caregivers toward community services. Gerontologist, 31(6), 756–761. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.6.756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, Q. D., Kind, A. J., Kim, A. J., Block, L. M., Thyrian, J. R., Monsees, J., Shah, M. N., & Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A. (2021). Dementia caregivers’ experiences engaging supportive services while residing in under-resourced areas. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 84(1), 169–177. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R., Frias-Osuna, A., Palomino-Moral, P. A., Ruzafa-Martinez, M., & Ramos-Morcillo, A. J. (2018). Social support and subjective burden in caregivers of adults and older adults: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 13(1), e0189874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne-Odom, J. N., Applebaum, A. J., Ornstein, K. A., Azuero, A., Warren, P. P., Taylor, R. A., Rocque, G. B., Kvale, E. A., Demark-Wahnefried, W., & Pisu, M. (2018). Participation and interest in support services among family caregivers of older adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 27(3), 969–976. doi: 10.1002/pon.4603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, J. M., & Power, E. J. (2000). Transforming insurance coverage into quality health care: Voltage drops from potential to delivered quality. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(16), 2100–2107. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, S. J., Solway, E., Kirch, M., Malani, P., Singer, D., & Roberts, J. S. (2021). Correlates of formal support service use among dementia caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(2), 135–150. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2020.1816589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, V., & Litzelman, K. (2021). Caregiver resource utilization: Intellectual and development disability and dementia. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(6), 1468–1476. doi: 10.1111/jar.12889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann, M. L., Newman, F. L., Buckwalter, K. C., & Montgomery, R. J. (2014). Resource need and use of multiethnic caregivers of elders in their homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(3), 662–673. doi: 10.1111/jan.12230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, C., Taylor, B., Robinson, J., & Gott, M. (2019). Comparison of financial support for family caregivers of people at the end of life across six countries: A descriptive study. Palliative Medicine, 33(9), 1189–1211. doi: 10.1177/0269216319861925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, N., Chow, J., Scharlach, A. E., & Dal Santo, T. S. (2004). Racial and ethnic differences in family caregiving in California. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 9(4), 85–109. doi: 10.1300/j137v09n04_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson, K., & Dal Santo, T. S. (2008). Caregiver service use: A complex story of care at the end of life. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 4(4), 286–311. doi: 10.1080/15524250903081475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrop, E., Byrne, A., & Nelson, A. (2014). “It’s alright to ask for help”: Findings from a qualitative study exploring the information and support needs of family carers at the end of life. BMC Palliative Care, 13(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith, C., Lahr, M., & Casey, M. (2019). A national examination of caregiver use of and preferences for support services: Does rurality matter? Journal of Aging and Health, 31(9), 1652–1670. doi: 10.1177/0898264318786569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, A. P., Lee, J., Palos, G., & Torres-Vigil, I. (2008). Cultural influences in the patterns of long-term care use among Mexican American family caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27(2), 141–165. doi: 10.1177/0733464807310682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., & Nicolau, B. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018: User guide. McGill University. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.-I. (2010). Understanding patterns of service utilization among informal caregivers of community older adults. Gerontologist, 50(1), 87–99. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.-I., Hasche, L., & Lee, M. J. (2011). Service use barriers differentiating care-givers’ service use patterns. Ageing & Society, 31(8), 1307–1329. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10001418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P. M., Wacker, R., & Collins, S. M. (2009). Family influence on caregiver resistance, efficacy, and use of services in family elder care. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 52(4), 377–400. doi: 10.1080/01634370802609304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y., Mitchell, H. R., & Ting, A. (2019). Application of psychological theories on the role of gender in caregiving to psycho-oncology research. Psycho-Oncology, 28(2), 228–254. doi: 10.1002/pon.4953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosloski, K., Schaefer, J. P., Allwardt, D., Montgomery, R. J., & Karner, T. X. (2002). The role of cultural factors on clients’ attitudes toward caregiving, perceptions of service delivery, and service utilization. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 21(3–4), 65–88. doi: 10.1300/J027v21n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner, G. (2001). AARP caregiver identification study. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/post-import/caregiver.pdf

- LaValley, S. A., Vest, B. M., & Hall, V. (2019). Challenges to and strategies for formal service utilization among caregivers in an underserved community. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 62(1), 108–122. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2018.1542372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y., Choi, W., & Park, M. S. (2022). Respite service use among dementia and nondementia caregivers: Findings from the National Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 Survey. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(6), 1557–1567. doi: 10.1177/07334648221075620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 181–189. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman, K., & Wisconsin Family and Caregiver Support Alliance. (2019). Wisconsin Family and Caregiver Support Alliance Family Caregiver Survey 2019. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1hDKSB8SrmEZUnqBZUxuT2Pl2Na0nrMAI/view

- Litzelman, K., Choi, H., & Reblin, M. (2021). Conceptualizing family caregivers’ access to and utilization of community support services: A scoping review protocol. https://osf.io/df6mk/

- Litzelman, K., & Harnish, A. (2022). Caregiver eligibility for support services: Correlates and consequences for resource utilization. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(2), 515–525. doi: 10.1177/0733464820971134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod, A., Tatangelo, G., McCabe, M., & You, E. (2017). “There isn’t an easy way of finding the help that’s available.” Barriers and facilitators of service use among dementia family caregivers: A qualitative study. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(5), 765–776. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216002532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale-Adams, J., Nichols, L. O., Zuber, J., Burns, R., & Graney, M. J. (2016). Dementia caregivers’ use of services for themselves. Gerontologist, 56(6), 1053–1061. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. T., & Canada, N. (2012). Linking employed caregivers’ perceptions of long-term community services with health care legislation. Family and Community Health, 35(4), 345–357. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182666793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H. (2016). Predictors of perceived benefits and drawbacks of using paid service among daughter and daughter-in-law caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Women and Aging, 28(2), 161–169. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2014.954505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott, J., Schmidt, B., & MacWilliams, B. (2019). Male caregivers: Shifting roles among family caregivers. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 23(1), E17–E24. doi: 10.1188/19.CJON.E17-E24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving, & AARP Public Policy Institute. (2020). Caregiving in the US 2020. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states-01-21.pdf

- O’Connor, D. L. (2007). Self-identifying as a caregiver: Exploring the positioning process. Journal of Aging Studies, 21(2), 165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2006.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L. J., & Fabius, C. D. (2020). Racial differences in respite use among black and white caregivers for people living with dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(10), 1667–1675. doi: 10.1177/0898264320951379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penchansky, R., & Thomas, J. W. (1981). The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care, 19(2), 127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radina, M. E., & Barber, C. E. (2004). Utilization of formal support services among Hispanic Americans caring for aging parents. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 43(2–3), 5–23. doi: 10.1300/j083v43n02_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard, S. C., Feinberg, L. F., Houser, A., Choula, R., & Evans, M. (2019). Valuing the invaluable: 2019 update charting a path forward. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/11/valuing-the-invaluable-2019-update-charting-a-path-forward.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00082.001.pdf

- Reinhard, S. C., Kassner, E., Houser, A., Ujvari, K., Mollica, R., & Hendrickson, L. (2014). Raising expectations, 2014: A state scorecard on long-term services and supports for older adults, people with physical disabilities, and family caregivers. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2014/raising-expectations-2014-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf

- Richardson, V. E., Fields, N., Won, S., Bradley, E., Gibson, A., Rivera, G., & Holmes, S. D. (2019). At the intersection of culture: Ethnically diverse dementia caregivers’ service use. Dementia, 18(5), 1790–1809. doi: 10.1177/1471301217721304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto, K. A., Savla, J., McCann, B. R., Blieszner, R., & Knight, A. L. (2022). Dementia family caregiving in rural Appalachia: A sociocultural model of care decisions and service use. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77(6), 1094–1104. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santo, T. S. D., Scharlach, A. E., Nielsen, J., & Fox, P. J. (2007). A stress process model of family caregiver service utilization: Factors associated with respite and counseling service use. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49(4), 29–49. doi: 10.1300/j083v49n04_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savla, J., Roberto, K. A., Blieszner, R., & Knight, A. L. (2022). Family caregivers in rural Appalachia caring for older relatives with dementia: Predictors of service use. Innovation in Aging, 6(1), igab055. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach, A. E., Giunta, N., Chow, J. C.-C., & Lehning, A. (2008). Racial and ethnic variations in caregiver service use. Journal of Aging and Health, 20(3), 326–346. doi: 10.1177/0898264308315426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach, A. E., Gustavson, K., & Dal Santo, T. S. (2007). Assistance received by employed caregivers and their care recipients: Who helps care recipients when caregivers work full time? Gerontologist, 47(6), 752–762. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach, A. E., Kellam, R., Ong, N., Baskin, A., Goldstein, C., & Fox, P. J. (2006). Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: Lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(1–2), 133–156. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n01_09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., Chan, K., Ferretti, L., & McCallion, P. (2018). Caregiving load and respite service use: A comparison between older caregivers and younger caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(1), 31–44. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2017.1391364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F., Kosberg, J. I., Leeper, J., Kaufman, A., & Burgio, L. (2007). Formal services utilization by family caregivers of persons with dementia living in rural southeastern USA. Rural Social Work and Community Practice, 12(2), 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F., Mutlu, A., & Coon, D. (2014). Service barriers faced by Chinese American families with a dementia relative: Perspectives from family caregivers and service professionals. Clinical Gerontologist, 37(2), 120–138. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2013.868848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toseland, R. W., McCallion, P., Gerber, T., & Banks, S. (2002). Predictors of health and human services use by persons with dementia and their family caregivers. Social Science and Medicine, 55(7), 1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. (2022). Covidence systematic review software. www.covidence.org

- Watari, K., Wetherell, J. L., Gatz, M., Delaney, J., Ladd, C., & Cherry, D. (2006). Long distance caregivers: Characteristics, service needs, and use of a long distance caregiver program. Clinical Gerontologist, 29(4), 61–77. doi: 10.1300/j018v29n04_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S. W., & Dilworth-Anderson, P. (2002). Systems of social support in families who care for dependent African American elders. Gerontologist, 42(2), 224–236. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow, B. W. (2003). Family caregivers’ experiences with community services: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nursing, 20(5), 341–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisconsin Family and Caregiver Support Alliance. (2018). Wisconsin family caregivers: Important supports and barriers identified by professionals. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vANJ5lmC0aAB9HgOHbyIV3by0R4L_Ua4/view?usp=sharing

- Xu, L., Lee, Y., Kim, B. J., & Chen, L. (2021). Determinants of discretionary and non-discretionary service utilization among caregivers of people with dementia: Focusing on the race/ethnic differences. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 40(1), 75–92. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2020.1805083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, H. M., McCormick, W. M., & Vitaliano, P. P. (2002). Attitudes toward community-based services among Japanese American families. Gerontologist, 42(6), 814–825. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrak, K. A., & Campione, J. R. (2021). The effect of National Family Caregiver Support Program services on caregiver burden. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(9), 963–971. doi: 10.1177/0733464819901094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP). Extraction materials and results are available upon request. The scoping review protocol was preregistered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/df6mk/).