Abstract

Studies in humans strongly implicate Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Thus, Th17 cells are major targets of approved and emerging biologics. Herein, we review the role of Th17 in IBD with a clinical focus.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic systemic relapsing-remitting conditions that are thought to be the end result of dysregulated host immune responses to enteric flora.1 The pathogenesis of IBD is complex. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and animal models implicate multiple mechanisms of disease induction and propagation.2 Indeed, every component of the gut from the enteric microbiome to (host) epithelial and immune cells including antigen presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells and macrophages and T and B cells have all been linked to the pathogenesis of IBD.2

In this regard, it has become clear over the last 20 years that the IL-17 producing subset of CD4+ T-cells, termed “Th17” cells, are strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD.2–5 This connection has in turn focused intense attention on Th17 cells, leading to IBD therapies targeting these pathways.6, 7

Herein, we review the role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis and treatment of IBD, with a focus on clinically relevant avenues including emerging therapies. Our goal is to make this subject accessible while encompassing the most relevant aspects of Th17 biology. This review is written with the clinician in mind and is aimed at providing an overview of Th17 cell biology in humans. Much has been written about the fundamental biology of Th17 cells in mice and humans, and we refer the reader interested in the unadulterated complexity of the subject to any number of outstanding reviews.8–10

MUCOSAL BIOLOGY AND T-CELL DIFFERENTIATION: THE BASICS

The immune system is a multifarious system with many interconnected parts. At the very core, it exists to protect the host from overwhelming pathogenic invasions. Consistent with this purpose, regions of the body that are constantly inundated with microbes, such as the skin, genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) tracts, and respiratory system, are also suffused with extensive immune defenses.11, 12

The intestinal immune system functions to regulate homeostatic enteric flora but also prevent barrier breach by pathogenic strains while facilitating nutrient extraction. In a simplified and expansive sense, it is composed of the epithelium, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), APCs, and T and B lymphocytes.11, 12 Each of these cell types encompasses subtypes that play specialized roles. Not surprisingly, the intestine contains several T-cell subset—most notably, CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T-cells distinguished by expression of distinct T-cell receptors (TCRs).13 These T-cell subtypes also exhibit a distinct spatial localization with CD8+ and γδ T-cells typically enriched in the intraepithelial compartment, whereas CD4+ T-cells reside primarily in the lamina propria in the basal state.14 Increasing evidence furthermore suggests that spatial localization may determine T-cell function, as some subpopulations of T-cells are thought to permanently reside in the intestine.15–18

The long-term goal of the immune system is to generate adaptive antigen-specific responses that maintain host integrity. Although the process sometimes tips towards autoimmunity, by and large a suitable balance is achieved with high frequency, and fidelity T-cells are armed with a TCR that has specificity for a given epitope. T-cells are termed “naïve” if they have not engaged their cognate antigen via the TCR and are different flavors of “terminally differentiated” if they have undergone this process. Naïve T-cells are quiescent and do not produce effector cytokines like interleukin (IL)-17A, interferon gamma (IFN)γ, or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α but circulate throughout the blood and lymphatics until they meet their cognate antigen in lymphoid organs.19 This antigen, presumably a piece of some invading virus, fungi, or bacteria, is presented to the T-cell by the appropriately termed APC (which is usually a dendritic cell or monocyte in this context).20–22 In addition to presenting the antigen, APCs also produce cytokines, which are broadly determined by the type of antigen and the type of pathogen recognition receptor (PRR) to which the antigen is bound on the APC.23, 24 Well known PRRs include toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nod-like receptors (NLRs). T-cells will differentiation in this milieu into specific terminally differentiated subsets typified by characteristic “master” transcription factors (TFs) and cytokines. Well known T-cell subsets include Th1, Th2, Th17, and T regulatory (Treg) cells. Th1 cells are induced by IL-12, express the master TF T-box protein expressed in T-cells (TBET), and produce the cytokine IFNγ.25 Similarly, IL-4 is the lineage driving cytokine for Th2 cells, which are characterized by expression of GATA3 and production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.26 Once differentiated, these T-cell subsets then traffic to sites of pathogen invasion including end organs such as the intestine by expressing organ-homing receptors (such as α4β7) to execute “effector” functions.27

TH17 CELL DIFFERENTIATION

The link between IBD and Th17 cells is predicated on the pathways that induce and maintain Th17 cells.

Similar to Th1 and Th2 cells, Th17 cells are terminally differentiated cells. Th17 differentiation and stabilization seems to be more complex than that of Th1 or Th2 cells.28, 29 In addition, the conditions for differentiation of human Th17 cells may be different than that of murine Th17 cells; thus murine Th17 cell biology may not be congruent with that of humans.8–10, 30 Specifically, the exact combination of cytokines necessary for human Th17 cell differentiation (both in vitro and in vivo) have not been irrefutably elucidated. Avoiding the grueling details, much of this controversy rests whether transforming growth factor (TGF)β is required for human Th17 cell differentiation.9, 30

Murine Th17 cells can be differentiated in vitro with the combination of TGFβ and IL-6.31–33 Interleukin-23 is dispensable for differentiation but absolutely necessary for murine Th17 stabilization.34, 35 The case in humans is more controversial. Initial studies using human T-cells reported differentiation of Th17 cells with IL-1β or the combination of IL-1β and IL-23 without TGFβ.36–39 This controversy seemed to close when it was noted that the in vitro culture media in those reports contained serum and was potentially contaminated with platelets, both of which are sources of TGFβ. Furthermore, the purported naïve T-cells in those studies could have included differentiated T-cells due to the technicalities of how the naïve T-cells were obtained. When these studies were repeated with rigorous removal of TGFβ and with truly naïve T-cells derived from umbilical cord blood, it seemed that TGFβ is indeed necessary for Th17 cell differentiation.40 Moreover, optimal induction of Th17 cells occurred with the combination of TGFβ, IL-1β, and IL-23. High concentrations of TGFβ impaired induction of RORC, which encodes the master transcription factor for Th17 cells, RORγt, suggesting there is an optimal range of TGFβ for induction of Th17 cells.40

However, more recent data have once again called into question the requirement of TGFβ, indicating that TGFβ-dependent pathways generate so-called “nonpathogenic” Th17 cells that produce the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, whereas TGFβ-independent pathways generate “pathogenic” Th17 cells typified by production of IL-17A, IFNγ, and Gram-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF).41 TGFβ-independent Th17 cells can be generated by various combinations of IL-1β, IL-23 and IL-6 and exhibit a distinct gene profile and are more pathogenic in vivo relative to their TGFβ-dependent counterparts.41 Adding one more layer to all this, it seems that IL-21 can promote Th17 cell differentiation via autocrine mechanisms and it may act as an alternative pathway in the absence of IL-6.42–44 What the relevance all of this to humans is unclear. Interestingly however, humans with IL-6R deficiency have normal numbers of Th17 cells, while those with IL-21R deficiency have marked reductions, indicating that IL-21 is more important for Th17 cell differentiation in humans than IL-6.45, 46

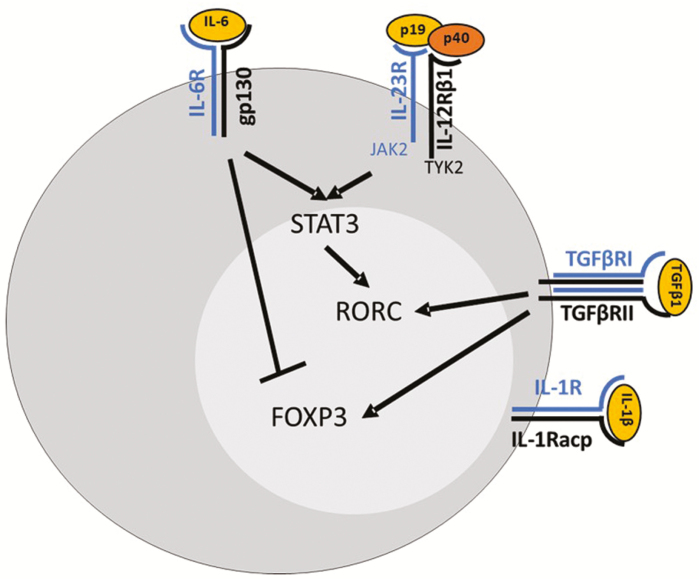

Transforming growth factor β is required for RORC induction but also potently induces FOXP3, the master TF for Treg cells. Interleukin-6 is thus thought to function by suppressing FOXP3 generation and activating the transcription factor, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3, which strongly tips the balance toward Th17 cell generation.8, 10 Indeed, this node between Th17/Treg differentiation is one reason these cells are often considered together. The STAT3 then further induces RORC with subsequent production of IL-17A and upregulation of the IL-23 receptor (IL-23R), thus defining Th17 cells.8, 10

The exact role and function(s) of IL-23 in Th17 cells biology is likely to be multifaceted. Interleukin-23 is a member of the IL-12 cytokine family and is a heterodimer of the p40 subunit (which is shared with IL-12) and the p19 subunit which is unique to IL-23. It was long held that CD was a Th1-IFNγ-mediated disease based on evidence of high amounts of IFNγ-producing T-cells in patients with CD and because blockade of the p40 subunit of IL-12 (which drives Th1 differentiation) ameliorated murine models of autoimmune disease. This paradigm was upended with the discovery that the p40 subunit is shared by both IL-12 and IL-23. Murine models then made it clear that isolated blockade of p19 (and thus IL-23) ameliorated disease in autoimmune models (collagen-induced arthritis, experimental auto-immune encephalomyelitis [EAE], T-cell transfer colitis, IL-10-/- colitis), whereas mice were largely susceptible to disease with p35 blockade (and thus IL-12), proving that the pathogenic component in these models was IL-23 rather than IL-12.35, 47, 48 Consistent with this, anti-IFNγ therapies have had modest results in CD.7

Naïve mouse T-cells do not express the IL-23R, but the IL-23R is induced by RORC. It is clear that IL-23 is required for the maintenance of Th17 cells, as IL-23R-/- mice have substantial loss of Th17 cells long-term.34 However in contrast to mice, it seems that IL-23 (in combination with other cytokines) can indeed drive the differentiation of naïve human T-cells toward a Th17 lineage.41, 49 The receptor for IL-23 is a heterodimer composed of the IL-12RB1 chain (which is shared with the IL-12R) and the IL-23R. Signaling downstream of the IL-23R is via janus kinase (JAK)2 and tyrosine kinase (TYK)2 and culminates in the activation of STAT3.8 Thus, it plausibly functions in a positive feedback loop for stabilizing Th17 cells.10 One other critical feature of IL-23R signaling is that it seems to promote the formation of a particularly pathogenic subset termed of Th17 cells characterized by coproduction of IL-17A and IFNγ.8, 10 Exactly how IL-23 drives pathogenic Th17 cells is uncertain. Moreover, how TBET promotes pathogenic Th17 cells is also unknown. However, IL-17A+IFNg+ Th17 are more pathogenic in mouse models compared to IL-17A+ Th17 cells alone.50–53

Broadly speaking then, a (vastly) simplified theory of Th17 differentiation is that specific pathogens preferentially promote the production of Th17-driving cytokines (eg, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23) when they bind to PRRs in APCs. Antigen-laden APCs then skew naïve T-cells toward Th17 differentiation and suppress differentiation of other T-cell subsets in an inflammatory milieu that is already rich in TGFβ. The combination of TGFβ and IL-6 (or IL-21, IL-23, and IL-1β) then results in activation of STAT3 in naïve T-cells, with sequential induction of RORC and IL-17A and IL-23R (Fig. 1). Signaling through the IL-23R then creates a positive feedback loop wherein IL-23R-induced STAT3 further stabilizes RORC induction and the Th17 phenotype. Given our clinical focus, we have limited our summary of Th17 cell differentiation to pathways clearly implicated in human IBD. Genetic regulation of Th17 cell differentiation is very complex, and there are a myriad of important issues that have been glossed over; for a more extensive and detained analysis on this, we refer the reader to some primary papers.28, 29

FIGURE 1.

Th17 cell differentiation. Differentiation of Th17 cells depends on stimulation with IL-6 and TGFβ with induction of RORC and suppression of FOXP3. IL-23R signaling then reinforces Th17 commitment by via-STAT3.

PLASTICITY OF TH17 CELLS

Antigen-experienced T-cells are considered to be “committed,” meaning that once they specialize in to distinct Th –lineages, they and their progeny remain within that lineage. Evidence for this paradigm is strong for the earliest discovered Th lineages, Th1, and Th2 cells. However, this paradigm may not hold for Th17 cells (or T regulatory cells). Th17 cells in vivo exhibit a propensity to shift over time to a Th17/Th1 phenotype characterized by coproduction of IL-17A and IFNγ—or solely to a Th1 phenotype with cessation of IL-17A production.54 This feature of Th17 cells is termed “plasticity.” Increasing evidence, largely from in vitro and in vivo murine models of multiple sclerosis and colitis, indicates that these “ex-Th17” cells are especially pathogenic relative to their purely Th17 or Th1 counterparts.52, 55 Moreover, in murine models, it seems that IL-23 is a key regulator of this division and that Th17 cell plasticity is dependent on contextual cues (such as locally produced IL-23).55 Genetic regulation of Th17 plasticity is complex, is incompletely understood, and may be contextual. Broadly however, plasticity may be related to stability of RORγt expression and epigenetic marks regulating accessibility of TBET, the master TF for Th1 cells.56 The exact function and role of Th17 plasticity in humans in vivo is not definitively known. However, Th17/Th1 cells are enriched in human autoimmune conditions including multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease, which corroborates murine data linking Th17 plasticity to human IBD.57–59

TH17 CELLS AND THE ENTERIC MICROBIOME

There is a strong link between the microbiome and Th17 cells. Th17 cells are enriched in the ileum under homeostatic conditions in humans and in certain strains of mice.60–64 Homeostatic induction of ileal Th17 cells in mice is dependent on the microbiota and, in particular, is dependent on strains of bacteria (segmented filamentous bacteria [SFB]) or fungi (Candida albicans) that can make contact with the epithelium.60, 61, 64 In addition, pathogenic strains of bacteria, such as Citrobacter rodentium (the murine equivalent of Escherichia coli), can also induce Th17 cells in an epithelial contact-dependent manner.63, 64 Adding to this link, mice raised under germ-free conditions are immune to colitis in many Th17-dependent murine models including IL-10-/- and T-cell transfer colitis.65, 66 Dysbiosis of enteric flora is well known to be a central feature in IBD. Although there is now a substantial body of work linking changes in the enteric microbiome with disease induction, progression, and response to therapy, there is a relative sparsity on of work on the host drivers of this relationship—at least in humans. In this regard, Th17 cells offer a potential link between dysbiosis in IBD and the pro-inflammatory host response.67 Though this topic is of considerable theoretical importance, given the paucity of treatments targeting the microbiome, we will not discuss it further here. Instead, we refer those interested to the important primary publications already referenced in this section.

THE LINK BETWEEN TH17 CELLS AND IBD

Th17 cells are strongly linked to IBD based on murine model—but perhaps more convincingly by genetic and functional studies in humans.

Genome-wide Association Studies

Over 160 alleles that confer risk for IBD have been identified by GWAS studies. Despite the success of these studies, it is critical to bear in mind when interpreting GWAS studies that they do not in general identify directly causal alleles.2, 5 Instead, they identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at loci encompassing a potential target gene or, in some cases, genes. Moreover, distinct SNPs in gene regions can have distinct correlation patterns, and it is not uncommon to have multiple protective and risk variants in the same gene region.68

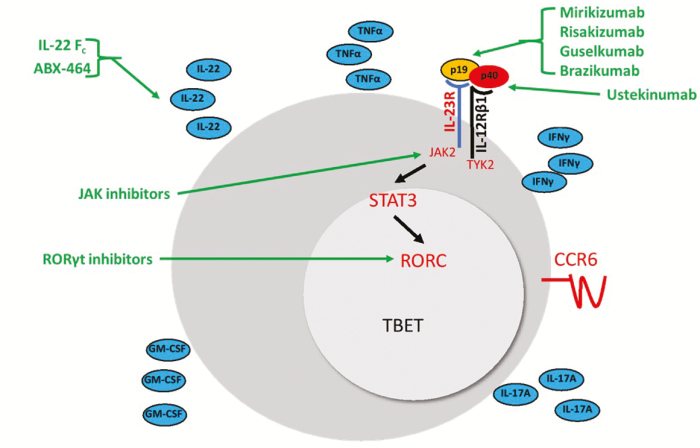

Given this caveat, GWAS studies in IBD have nonetheless provided strong evidence linking IBD to Th17 pathways. Risk alleles in genes specifically in Th17 pathways include CARD9, IL12B, STAT3, RORC, IL23R, JAK2, TYK2, and CCR6. Thus, SNPs in Th17 pathways genes would be expected to impact Th17 cell generation (CARD9, IL12B) and intra-cellular events important for Th17 lineage commitment and maintenance (STAT3, RORC, IL23R, JAK2, TYK2) or Th17 cell function (CCR6)2 (Fig. 2). Of these, SNPs in CARD9 and IL23R are of particular importance, as they are in coding regions, and there are multiple risk- and protective-alleles for each gene.4

FIGURE 2.

Th17 cells and inflammatory bowel disease risk alleles and treatments. Based on animal models, pathogenic Th17 cells are thought to express RORC and TBET and coproduce IL-17A and IFNγ. Independent of coproduction of IL-17A and IFNγ, differentiated Th17 cells produce IL-22, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and TNFα and express the receptor CCR6. Differentiated Th17 cells also express IL-23R, which is a heterodimer composed of IL-23R and IL-12Rβ and recognizes the cytokine IL-23. IL-23 is itself a heterodimer composed of the p40 subunit shared with IL-12 and p19. Several IBD risk alleles are in Th17 cell pathways (in red; p40, JAK2, TYK2, IL-23R, STAT3, RORC, CCR6) and several approved or pipeline agents for IBD target Th17 cell pathways (in green).

CARD9 is a critical convergence point downstream of fungal PRRs and is necessary to induce C. albicans–specific Th17 responses. Humans with CARD9 deficiency have substantially reduced Th17 cells with commensurate susceptibility to C. albicans infections.69 As we have already discussed, IL-23R is expressed by Th17 cells and is critical for Th17 cell physiology. The risk alleles in CARD9 are thought to either affect the level of functional CARD9 protein or to enhance downstream signaling and thus promote Th17 cells.70 Similarly, IL23R risk alleles are thought to augment IL-23R signaling, thereby promoting Th17 cells. In contrast, protective alleles of both CARD9 and IL-23R exhibit reduced downstream signaling with a commensurate dampening of Th17 cells.71, 72 The exact functional consequence of SNPs in the other alleles is not clear, but there is some suggestion that the STAT3 risk alleles cause increased signaling with augmented Th17 cell responses relative to controls.73

In addition, there are risk alleles in loci that are potentially involved in Th17 cell pathways including IL1R1/IL18RAP, IL2/IL21, PTGER4, and IL27.2 Loci at IL1R1/IL18RAP encode the receptors for IL-1β (IL-1R1) or IL-18 (IL18RAP), and the loci at IL2/IL21 encodes the cytokines IL-2 or IL-21. PTGER4 encodes a receptor for prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and IL27 encodes the cytokine IL-27. Given that IL-1β, IL-21, PGE2, and IL-27 have all been shown to play a role in the differentiation and function of human Th17 cells, it is possible that SNPs in these genes may produce disease-associating alternations in Th17 cells.8, 74, 75

Finally, though largely not specific to Th17 cells, risk alleles have also been found in a variety of genes that are necessary for the genetic regulation Th17 differentiation (at least in mice) including, PTPN22, KIF21B, GPR65, IL10, IL2RA, and TRIB1.2 Although these gene products have pleotropic functions affecting multiple cell types, all these genes are activated at some stage in the differentiation of Th17 cells.28 Thus, GWAS studies not only link pathways specifically expressed in Th17 cells to IBD but also implicate a broader array of pathways that may have functional consequences on Th17 cells.

Functional Studies in IBD

Genome-wide association studies provide a strong link between Th17 cells and disease susceptibility but do not completely explain variance in IBD, suggesting other factors besides risk alleles are at play in initiating and propagating IBD. In this regard, functional studies of changes in mucosal gene expression and of immune cells populations in IBD reinforce the like between IBD and Th17 cell biology and provide clues to other drivers of IBD.

Numerous studies have reported elevated expression of Th17 pathway cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-23, and IL-22 in the intestinal mucosal in active UC and CD relative to inactive regions and healthy controls.76–79 Moreover, several studies, although from single centers and small, have shown correlations between normalization of mucosal IL17A expression with treatment and short- and long-term clinical remission and endoscopic healing.78, 79 However, elevated expression of these cytokines does not definitively implicate Th17 cells since these cytokines can be produced by non-Th17 cells.

More specifically than gene induction data, Th17 cells are enriched in the intestinal mucosal in IBD and are more responsive to IL-23 in IBD relative to healthy control Th17 cells, suggesting they are more pro-inflammatory relative to their healthy control counterparts.80 Moreover, at least some Th17 cells in intestine in IBD patients coproduce IFNγ, consistent with a “pathogenic” Th1/Th17 phenotype.57–59 This collectively argues that pro-inflammatory, pathogenic Th17 cells are enriched in the mucosa in IBD relative to healthy controls. Consistent with this, we recently reported that CD4+ TRM cells, which are a subset of tissue-restricted CD4+ T-cells, are enriched in patients with CD exhibit a Th17 phenotype and are the major memory T-cell source of TNFα in active CD (and healthy controls).17 Similar to the data regarding intestinal CD4+ T-cells, peripherally circulating microbial antigen-reactive T-cells in patients with CD skew to a Th17 or Th1/Th17 phenotype relative to healthy controls that exhibit a Th1 phenotype.81

Consistent with this paradigm, inflammatory monocytes are enriched in CD and more avidly produce IL-23 when stimulated with enteric bacteria relative to healthy controls with resultant skewing of T-cells to a Th17 phenotype in CD.80, 82 Indeed, humanized gnotobiotic mice with dysbiotic enteric flora from IBD patients have a propensity to develop Th1/Th17 cells that are more colitogenic relative to Th17 cells from mice colonized with enteric flora from healthy controls.67

These data are strongest for CD relative to UC, but it collectively indicates a plausible mechanistic link between IBD and Th17 cell biology. These data also broadly raise the possibility that dysbiotic enteric flora in IBD shift APCs to an inflammatory, pro-Th17 phenotype with commensurate induction of pathogenic IBD promoting Th17 cells.

CAVEAT TO TH17 THERAPIES IN IBD

It is important to remember that although IL-23R is expressed on Th17 cells and, conversely, Th17 cells are considered important targets (and perhaps the primary target) of anti-IL-23 agents, many cell types express IL-23R.83 Notable IL-23R-expressing cells include ILCs and epithelial cells.84 Thus, IL-23 biology is explicitly not the same as Th17 biology.9 Despite this, one could make an excellent argument that the primary targets of therapeutic consequence for anti-IL-23 therapies are Th17 cells. This is because (1) IL-23R signaling in epithelial cells is considered to have a protective rather than pathogenic role for epithelial host defense and restitution, and (2) there isno clear evidence, as yet, that ILCs are pathogenic in IBD (although there are data correlating changes in disease state and ILC subsets).84, 85 Adding to the latter, there is intriguing data suggesting ILCs are redundant for host defense in humans.86 Collectively, this suggests that ILCs are critical for murine physiology but may be redundant in humans.

We should also discuss anti-IL-17A therapies, which failed in CD. These trials were halted early due to either higher rates of adverse events or worsening CD in the treatment arms.87, 88 These results were surprising given the link between Th17 cells and IBD and the good efficacy of anti-IL-17 agents in psoriasis. Although trials fail for many reasons, new studies indicate that many of the pathogenic effects of Th17 cells are IL-17-independent. Indeed, 2 murine studies using distinct models of colitis have shown that IL-17 signaling in epithelial cells is critical for epithelial cell production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and for maintaining tight-junctions, thus promoting epithelial barrier integrity. Moreover, in at least 1 of these studies, IL-23 was pathogenic, whereas IL-17 was protective. Furthermore, though IL-17A is the signature cytokine of Th17 cells, it is not necessarily what promotes the pathogenicity of these cells. Th17 cells produce a variety of other cytokines, including TNFα and GM-CSF, which are pathogenic in many models.35, 89 Consistent with this, it has been demonstrated using GM-CSF fate mapping mice that tissue damage in EAE is specifically due to GM-CSF-producing Th17 cells, which recruit neutrophil influx.89 Conversely, IL-17A is produced by multiple cells besides Th17 cells including ILCs, CD8+ T-cells, and NK-cells.8, 10

Another distinct possibility for the failure of anti-IL-17 agents in IBD is the effect of IL-17 on the enteric microbiome. As noted earlier, SFB promote the formation of Th17 cells. However, Th17 cells in turn negatively regulate enteric SFB via IL-17-dependent production of epithelial AMPs.90 Blocking epithelial cell IL-17 signaling in this system leads to the expansion of enteric SFB, which promotes the formation of pathogenic Th17 cells. Thus, this system of reciprocal regulation of Th17 cells by SFB, followed by Th17-produced IL-17-dependent regulation of SFB functions as a negative feedback loop restraining pathogenic Th17 cells.90 These data therefore suggest that Th17 cells may be pathogenic independent of IL-17 and that IL-17 blockade both worsens epithelial restitution after injury and promotes the expansion of pathogenic enteric microbiota. Therefore, these data collectively provide plausible reasons for the discordant efficacy of anti-IL-17 and anti-IL-23 therapies in IBD. Thus, it is collectively clear that Th17, IL-23, and IL-17 may overlap but are also all distinct, which impacts drug development and efficacy in IBD.

TH17 TARGETING THERAPIES

Given what we know about the link between Th17 cells and IBD, the rise of anti-IL-23 therapies, either targeting the shared p40 subunit between IL-12 and IL-23 or targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23 alone, have a sound biological background. In addition, given that IL-23R signaling is via JAK/STATs, it is very likely that JAK-inhibitors, specifically JAK2 inhibitors, will also impact Th17 cell pathways. Because JAKs are ubiquitously expressed in multiple cell types, we focus here on therapies that specifically impact Th17 pathways, namely anti-IL-23, anti-IL-23R, and pro-IL-22 agents in the IBD pipeline.

Anti-IL-23 Agents: Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody that binds to and neutralizes p40, the shared subunit of IL-12 and IL-23 (Fig. 2). Ustekinumab is currently the only FDA-approved anti-IL-23 therapy for IBD, having gained approval for CD in 2016. The clinical trial data are published, and much has been written about the real-world efficacy, including therapeutic drug monitoring and safety data. Phase 3 studies in UC are currently underway and the complete data sets have not been published. However, early results report efficacy for induction, with ~16 % of patients reporting clinical remission at week 8 in the treatment arms (130 mg IV or 6 mg/kg IV) compared with 5% in the placebo group. Moreover, statistically significant fractions of patients who achieve remission with IV induction also maintained remission at week 44 with maintenance therapy of 90 mg SQ every 12 weeks (38%) or every 8 weeks (44%) compared with 24% of those receiving placebo maintenance. Most importantly, ~20% of patients achieved mucosal healing, defined as Mayo endoscopic subscore of ≤1 and histologic healing at week 8 relative to 9% receiving placebo induction, whereas endoscopic healing (Mayo ≤1 alone) was achieved in substantial fraction at week 44 (44% and 51% in maintenance very 12 or 8 weeks, respectively) compared with placebo maintenance (29%).91

Mirikizumab

Mirikizumab is a monoclonal IgG4 that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23 and thus only blocks IL-23 (Fig. 2). A phase 2 study in CD randomizing patients with placebo, 200 mg, 600 mg, or 1000 mg of IV induction followed by open-label treatment was just completed. The primary outcome of endoscopic response, defined as a reduction in the CD simple endoscopic score (SES-CD), was achieved in 11% in the placebo induction group and in 26%, 38%, and 44% of the 200 mg, 600 mg, and 1000 mg induction arms respectively (all significant). Moreover, endoscopic remission, defined as SES-CD of <4 for ileo-colonic disease or <2 for ileal disease without a subscore >1, was achieved in 2% of placebo-treated patients followed by, 7%, 16%, and 20% of drug-treated patients in a dose-dependent manner.92 Although this seems promising, the numbers in this phase 2 study were largely limited to 30 to 60 patients per arm, and phase 3 studies are actively recruiting.

Data from induction and maintenance portions of a phase 2 study in UC have recently been reported.93 The induction study compared clinical remission at week 12 with either IV mirikizumab induction of 50 mg or 200 mg with the possibility of exposure-based increases or fixed dosing of 600 mg at weeks 0, 4 and 8. The exactitudes of the variable dosing were not reported in detail, but 23% of patients in the 200 mg exposure-based dosing groups achieved the primary outcome of clinical remission at week 12 relative to 5% of placebo treated patients. Interestingly, there were no statistically significant differences between other groups and placebo despite higher mean doses in the 600 mg arm compared with the 200 mg arm (600 mg vs 260 mg, respectively).93 Endoscopic healing (Mayo ≤1) was significantly different at lower doses (24% and 31% for 50 mg and 200 mg, respectively) compared with placebo (6%). Similar to clinical remission, however, endoscopic remission in the high dose group (13%) did not did not separate from placebo.93

Responders to mirikizumab induction were then rerandomized to either placebo or 200 mg SQ every 4 or every 12 weeks; these results were recently reported. Maintenance dosing every 4 or 12 weeks effectively achieved endoscopic remission (Mayo ≤ 1) in 57% and 48%, respectively. Although this sounds promising, it is incomplete as placebo response rates have not yet been reported.94 Phase 3 studies in UC are ongoing.

Risankizumab

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 anti-p19 antibody that recently reported results of a phase 2 induction study in CD (Fig. 2). Patients were randomized to placebo vs 200 mg or 600 mg IV at weeks 0, 4, and 8, with assessment of the primary outcome of clinical remission (CDAI <150) at week 12. Clinical remission was significantly different between placebo (15%) and 600 mg dosing (37%), but not for 200 mg dosing (24%). There were also significant differences in endoscopic remission between placebo (3%) and the 200 mg (15%) and 600 mg (20%) groups.95 This study was followed by an open-label extension (OLE) of 600 mg IV every 4 weeks in those who did not achieve deep remission to induction, followed by 180 mg SQ maintenance every 8 weeks for 26 additional weeks in those in clinical remission in the prior group. This redosing strategy resulted in remission in 53% of those not in deep remission after induction and was maintained in 71% at week 52. Additionally, 35% achieved endoscopic remission at week 52.96 Because this was an OLE, placebo rates were not reported. Phase 3 studies in CD are ongoing. Data from phase 2 studies in UC have not been reported, but phase 3 studies are underway nonetheless.

Guselkumab

Guselkumab is a human IgG1 targeting the p19 subunit; it is currently recruiting for UC for a phase 2a comparing guselkumab monotherapy with guselkumab and golimumab dual therapy and a phase 2 comparing active drug to placebo (Fig. 2). Phase 2 and 3 studies in CD are currently recruiting. Data have not been reported for UC or CD.

Brazikumab

Brazikumab, formerly known as MEDI2070, is a recombinant human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23A. A phase 2a study in CD was completed, and current recruiting for phase 3 in CD and a phase 2 study in UC is planned (Fig. 2). In contrast to many other studies, patients in the phase 2a CD study are likely skewed to more refractory disease, as failure to at least 1 anti-TNF was an entry criterion. Though the broader study included a blinded 12-week induction period followed by a 100-week OLE, the reported data only cover the first 12 weeks of the OLE. Patients were randomized to brazikumab 700 mg IV at weeks 0 and 4 or to placebo, and assessments of the primary outcome of clinical response (decline in CDAI ≤0) followed at week 8 (induction). All patients then received 210 mg SQ every 4 weeks for the OLE. There were significant differences in the clinical response between groups at week 12 (49% vs 27% for drug and placebo arms, respectively). Furthermore, response and remission were robust in all groups after open label drug, raising the possibility that drug rescued those previously in placebo arms. Endoscopic data were not presented, and there were not differences in safety between groups.92

UTTR1147A

UTTR1147A is a recombinant fusion protein of human IL-22 fused with IgG4 Fc.97 Mechanistically, the IL-22-Fc fusion protein exhibits a long half-life and signals in epithelial cells (and presumably other IL-22R-expressing cells) to augment epithelial protective factors including AMPs. Preclinical testing has demonstrated efficacy in murine models and safety in healthy volunteers.97, 98 Recruitment for phase 1 trials in UC and CD and a phase 2 placebo-controlled comparative efficacy trial against vedolizumab in UC are ongoing.

ABX464

ABX464 is a small molecule that promotes the initial interaction with transcription and processing machinery by binding to a complex at the 5′-end of the pre-mRNA transcript. ABX464 is thought to exert its therapeutic effects in UC via this novel mechanism, ultimately resulting in upregulation of macrophage-produced IL-22, with subsequent mucosal protection (Fig. 2).99, 100 A small but placebo-controlled proof of concept study in UC demonstrated promising results, with clinical remission of 35% with treatment compared with 11% with placebo at 8 weeks.101 Phase 2 studies are planned.

RORgt Antagonists

Finally, there are several RORgt antagonists that have shown promise in preclinical murine models (Fig. 2).102–105 As expected based on the central role of RORgt in the regulation and maintenance of the Th17 lineage, these agents broadly inhibit Th17 cell transcriptional networks to destabilize Th17 cells.102–105 At least some of these agents seem to specifically inhibit Th17 cells rather than ILCs (which also express RORgt).102 Moreover, the inhibition of Th17 cells improved murine models of colitis and suppressed Th17 cells in vitro in human intestinal tissues.102

Supported by: Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award

Contributor Information

Guoqing Hou, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Michigan, MI, USA.

Shrinivas Bishu, Crohn’s and Colitis Center, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Michigan, MI, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nell S, Suerbaum S, Josenhans C. The impact of the microbiota on the pathogenesis of IBD: lessons from mouse infection models. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. ; International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) . Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strober W, Fuss IJ, Blumberg RS. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:495–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang H, Fang M, Jostins L, et al. ; International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium . Fine-mapping inflammatory bowel disease loci to single-variant resolution. Nature. 2017;547:173–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moschen AR, Tilg H, Raine T. IL-12, IL-23 and IL-17 in IBD: immunobiology and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abraham C, Dulai PS, Vermeire S, et al. Lessons learned from trials targeting cytokine pathways in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:374–388.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, et al. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patel DD, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cell pathway in human immunity: lessons from genetics and therapeutic interventions. Immunity. 2015;43:1040–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhaumik S, Basu R. Cellular and molecular dynamics of Th17 differentiation and its developmental plasticity in the intestinal immune response. Front Immunol. 2017;8:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blander JM, Longman RS, Iliev ID, et al. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:851–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:667–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma H, Tao W, Zhu S. T lymphocytes in the intestinal mucosa: defense and tolerance. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16:216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lutter L, Hoytema van Konijnenburg DP, Brand EC, et al. The elusive case of human intraepithelial T cells in gut homeostasis and inflammation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:637–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Senda T, Dogra P, Granot T, et al. Microanatomical dissection of human intestinal T-cell immunity reveals site-specific changes in gut-associated lymphoid tissues over life. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12:378–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Yudanin N, et al. Distribution and compartmentalization of human circulating and tissue-resident memory T cell subsets. Immunity. 2013;38:187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bishu S, El Zaatari M, Hayashi A, et al. CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells expand and are a major source of mucosal tumour necrosis factor α in active Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bishu S, Hou G, El Zaatari M, et al. Citrobacter rodentium induces tissue-resident memory CD4(+) T cells. Infect Immun. 2019;87. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00295-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rossjohn J, Gras S, Miles JJ, et al. T cell antigen receptor recognition of antigen-presenting molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:169–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chang JT, Palanivel VR, Kinjyo I, et al. Asymmetric T lymphocyte division in the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Science. 2007;315:1687–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, et al. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, et al. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:621–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zielinski CE, Mele F, Aschenbrenner D, et al. Pathogen-induced human TH17 cells produce IFN-γ or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1β. Nature. 2012;484:514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Masopust D, Schenkel JM. The integration of T cell migration, differentiation and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ciofani M, Madar A, Galan C, et al. A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell. 2012;151:289–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yosef N, Shalek AK, Gaublomme JT, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013;496:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mcgeachy MJ, Cua DJ. Th17 cell differentiation: the long and winding road. Immunity. 2008;28:445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, et al. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Beelen AJ, Zelinkova Z, Taanman-Kueter EW, et al. Stimulation of the intracellular bacterial sensor NOD2 programs dendritic cells to promote interleukin-17 production in human memory T cells. Immunity. 2007;27:660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Z, Tato CM, Muul L, et al. Distinct regulation of interleukin-17 in human T helper lymphocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2936–2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human T(H)-17 cells requires transforming growth factor-beta and induction of the nuclear receptor rorgammat. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:641–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-β signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, et al. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, et al. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, et al. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kotlarz D, Ziętara N, Uzel G, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the IL-21 receptor gene cause a primary immunodeficiency syndrome. J Exp Med. 2013;210:433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spencer S, Köstel Bal S, Egner W, et al. Loss of the interleukin-6 receptor causes immunodeficiency, atopy, and abnormal inflammatory responses. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1986–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen Y, Langrish CL, McKenzie B, et al. Anti-IL-23 therapy inhibits multiple inflammatory pathways and ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Murphy CA, Langrish CL, Chen Y, et al. Divergent pro- and antiinflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1951–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Revu S, Wu J, Henkel M, et al. IL-23 and IL-1β drive human Th17 cell differentiation and metabolic reprogramming in absence of CD28 costimulation. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2642–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang Y, Weiner J, Liu Y, et al. T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1549–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jain R, Chen Y, Kanno Y, et al. Interleukin-23-induced transcription factor blimp-1 promotes pathogenicity of T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2016;44:131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harbour SN, Maynard CL, Zindl CL, et al. Th17 cells give rise to Th1 cells that are required for the pathogenesis of colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:7061–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity. 2009;30:92–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Muranski P, Restifo NP. Essentials of Th17 cell commitment and plasticity. Blood. 2013;121:2402–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hirota K, Duarte JH, Veldhoen M, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wei G, Wei L, Zhu J, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Maggi L, Santarlasci V, Capone M, et al. CD161 is a marker of all human IL-17-producing T-cell subsets and is induced by RORC. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2174–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kleinschek MA, Boniface K, Sadekova S, et al. Circulating and gut-resident human Th17 cells express CD161 and promote intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cosmi L, De Palma R, Santarlasci V, et al. Human interleukin 17-producing cells originate from a CD161+CD4+ T cell precursor. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1903–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ladinsky MS, Araujo LP, Zhang X, et al. Endocytosis of commensal antigens by intestinal epithelial cells regulates mucosal T cell homeostasis. Science. 2019;363. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shaw MH, Kamada N, Kim YG, et al. Microbiota-induced IL-1β, but not IL-6, is critical for the development of steady-state TH17 cells in the intestine. J Exp Med. 2012;209:251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kamada N, Sakamoto K, Seo SU, et al. Humoral immunity in the gut selectively targets phenotypically virulent attaching-and-effacing bacteria for intraluminal elimination. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Ando M, et al. Th17 cell induction by adhesion of microbes to intestinal epithelial cells. Cell. 2015;163:367–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Asseman C, Read S, Powrie F. Colitogenic Th1 cells are present in the antigen-experienced T cell pool in normal mice: control by CD4+ regulatory T cells and IL-10. J Immunol. 2003;171:971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Feng T, Wang L, Schoeb TR, et al. Microbiota innate stimulation is a prerequisite for T cell spontaneous proliferation and induction of experimental colitis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1321–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Britton GJ, Contijoch EJ, Mogno I, et al. Microbiotas from humans with inflammatory bowel disease alter the balance of gut Th17 and RORγt+ regulatory T cells and exacerbate colitis in mice. Immunity. 2019;50:212–224.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rivas MA, Beaudoin M, Gardet A, et al. ; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium (NIDDK IBDGC); United Kingdom Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium; International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium . Deep resequencing of GWAS loci identifies independent rare variants associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1066–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lanternier F, Pathan S, Vincent QB, et al. Deep dermatophytosis and inherited CARD9 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1704–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cao Z, Conway KL, Heath RJ, et al. Ubiquitin ligase TRIM62 regulates CARD9-mediated anti-fungal immunity and intestinal inflammation. Immunity. 2015;43:715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Leshchiner ES, Rush JS, Durney MA, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors directly target CARD9 and mimic its protective variant in inflammatory bowel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:11392–11397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sarin R, Wu X, Abraham C. Inflammatory disease protective R381Q IL23 receptor polymorphism results in decreased primary CD4+ and CD8+ human T-cell functional responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9560–9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Willson TA, Kuhn BR, Jurickova I, et al. STAT3 genotypic variation and cellular STAT3 activation and colon leukocyte recruitment in pediatric Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lee J, Aoki T, Thumkeo D, et al. T cell-intrinsic prostaglandin E2-EP2/EP4 signaling is critical in pathogenic TH17 cell-driven inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:631–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Diveu C, McGeachy MJ, Boniface K, et al. IL-27 blocks RORc expression to inhibit lineage commitment of Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5748–5756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Leal RF, Planell N, Kajekar R, et al. Identification of inflammatory mediators in patients with Crohn’s disease unresponsive to anti-TNFα therapy. Gut. 2015;64:233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Arijs I, Li K, Toedter G, et al. Mucosal gene signatures to predict response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2009;58:1612–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rismo R, Olsen T, Cui G, et al. Normalization of mucosal cytokine gene expression levels predicts long-term remission after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rismo R, Olsen T, Cui G, et al. Mucosal cytokine gene expression profiles as biomarkers of response to infliximab in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:538–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kobayashi T, Okamoto S, Hisamatsu T, et al. IL-23 differentially regulates the Th1/Th17 balance in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2008;57:1682–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Calderón-Gómez E, Bassolas-Molina H, Mora-Buch R, et al. Commensal-specific CD4(+) cells from patients with Crohn’s disease have a T-helper 17 inflammatory profile. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:489–500.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kamada N, Hisamatsu T, Okamoto S, et al. Unique CD14 intestinal macrophages contribute to the pathogenesis of Crohn disease via IL-23/IFN-gamma axis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2269–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Awasthi A, Riol-Blanco L, Jäger A, et al. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor gfp reporter mice reveal distinct populations of IL-17-producing cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5904–5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Aden K, Rehman A, Falk-Paulsen M, et al. Epithelial IL-23R signaling licenses protective IL-22 responses in intestinal inflammation. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2208–2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Peters CP, Mjösberg JM, Bernink JH, et al. Innate lymphoid cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Immunol Lett. 2016;172:124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Vély F, Barlogis V, Vallentin B, et al. Evidence of innate lymphoid cell redundancy in humans. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1291–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Targan SR, Feagan B, Vermeire S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of AMG 827 in subjects with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143, E26. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, et al. ; Secukinumab in Crohn’s Disease Study Group . Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61:1693–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Komuczki J, Tuzlak S, Friebel E, et al. Fate-mapping of GM-CSF expression identifies a discrete subset of inflammation-driving T helper cells regulated by cytokines IL-23 and IL-1β. Immunity. 2019;50:1289–1304.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kumar P, Monin L, Castillo P, et al. Intestinal interleukin-17 receptor signaling mediates reciprocal control of the gut microbiota and autoimmune inflammation. Immunity. 2016;44:659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Panaccione R, et al. OP37 efficacy and safety of ustekinumab as maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis: week 44 results from UNIFI. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13, S025–S026. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. 1003—Efficacy and safety of mirikizumab (LY3074828) in a phase 2 study of patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:S–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sandborn WJ, Ferrante M, Bhandari BR, et al. 882 - Efficacy and safety of anti-interleukin-23 therapy with mirikizumab (LY3074828) in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in a phase 2 study. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:S1360–S1361. [Google Scholar]

- 94. D’Haens GGR, et al. OP38 Maintenance treatment with mirikizumab, a p19-directed IL-23 antibody: 52-week results in patients with moderately-to-severely active ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13, S026–S027. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens G, et al. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23 inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2017;389:1699–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Feagan BG, Panés J, Ferrante M, et al. Risankizumab in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: an open-label extension study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Stefanich EG, Rae J, Sukumaran S, et al. Pre-clinical and translational pharmacology of a human interleukin-22 IgG fusion protein for potential treatment of infectious or inflammatory diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;152:224–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Rothenberg ME, Wang Y, Lekkerkerker A, et al. Randomized phase I healthy volunteer study of UTTR1147A (IL-22Fc): a potential therapy for epithelial injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105:177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Chebli K, Papon L, Paul C, et al. The anti-HIV candidate Abx464 dampens intestinal inflammation by triggering Il-22 production in activated macrophages. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Manchon L, Chebli K, Papon L, et al. RNA sequencing analysis of activated macrophages treated with the anti-HIV ABX464 in intestinal inflammation. Sci Data. 2017;4:170150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Vermeire S, Hébuterne X, Napora P, et al. OP21 ABX464 is safe and efficacious in a proof-of-concept study in ulcerative colitis patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13, S014–S015. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Withers DR, Hepworth MR, Wang X, et al. Transient inhibition of ROR-γt therapeutically limits intestinal inflammation by reducing TH17 cells and preserving group 3 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Med. 2016;22:319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Xiao S, Yosef N, Yang J, et al. Small-molecule RORγt antagonists inhibit T helper 17 cell transcriptional network by divergent mechanisms. Immunity. 2014;40:477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tang L, Yang X, Liang Y, et al. Transcription factor retinoid-related orphan receptor gammat: a promising target for the treatment of psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Guendisch U, Weiss J, Ecoeur F, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of RORγt suppresses the Th17 pathway and alleviates arthritis in vivo. Plos One. 2017;12:e0188391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]