Abstract

Background

An enhanced understanding of renal outcomes in persons with chronic HBV, HIV, and HBV/HIV coinfection is needed to mitigate chronic kidney disease in regions where HBV and HIV are endemic.

Objectives

To investigate changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in adults with HBV, HIV or HBV/HIV enrolled in a 3 year prospective cohort study of liver outcomes in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and initiated on antiviral therapy.

Methods

We compared eGFR between and within groups over time using mixed-effects models.

Results

Four hundred and ninety-nine participants were included in the analysis (HBV: 164; HIV: 271; HBV/HIV: 64). Mean baseline eGFRs were 106.88, 106.03 and 107.18 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. From baseline to Year 3, mean eGFR declined by 4.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI −9.3 to 0.7) and 3.7 (−7.8 to 0.5) in participants with HBV and HIV, respectively, and increased by 5.1 (−4.7 to 14.9) in those with HBV/HIV. In multivariable models, participants with HBV had lower eGFRs compared with those with HIV or HBV/HIV and, after adjusting for HBV DNA level and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) status, significantly lower eGFRs than those with HBV/HIV at all follow-up visits.

Conclusions

In this Tanzanian cohort, coinfection with HBV/HIV did not appear to exacerbate renal dysfunction compared with those with either infection alone. Although overall changes in eGFR were small, persons with HBV experienced lower eGFRs throughout follow-up despite their younger age and similar baseline values. Longer-term studies are needed to evaluate continuing changes in eGFR and contributions from infection duration and other comorbidities.

Introduction

HIV continues to be a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), affecting 25.6 million people in 2021.1 Due to shared routes of transmission, chronic HBV is also highly prevalent, affecting approximately 9% of the general population and 15% of people with HIV (PWH).2,3 Both HIV and HBV have been associated with a wide range of renal pathologies, and HBV/HIV coinfection may confer a greater risk of renal dysfunction than either infection alone.4–7 In non-Tanzanian countries in SSA, the prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 2 or greater, i.e. estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and CKD stage 3 or greater, i.e. eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, have been estimated to be between 15.5% and 76.6% and 0.5% and 38.8%, respectively, in PWH.8–15 Higher burdens of CKD have been reported in populations where HIV immunosuppression is more profound (e.g. treatment naive) or other competing risks for renal disease (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, schistosomiasis) exist.16–18 In Tanzania, the prevalence of CKD stage 2 or greater and CKD stage 3 or greater have ranged from 29.2% (on ART) to 76.6% (not on ART) and 1.1% (on ART) to 21.1% (not on ART), respectively, in PWH.19–21 The prevalence of CKD in persons with HBV in SSA and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has been less well characterized. A cross-sectional study of adults with chronic HBV in Cameroon found that 11.8% and 2.9% of participants had at least CKD stage 2 and 3, respectively, similar to reported rates from high-income countries (HICs).22–25

Causes of CKD in PWH include HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), HIV immune complex kidney disease and comorbid conditions.7 Genetic polymorphisms in the APOL1 gene and ART-related nephrotoxicity such as proximal renal tubulopathy from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or intratubular precipitation of PIs may further contribute to incident renal dysfunction.26–31 HBV-related renal disease is largely attributed to the development of membranous nephropathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis or polyarteritis nodosa, also reported in persons with HBV/HIV coinfection.4,32 Although mechanisms of HBV-related glomerulopathy remain poorly understood, age at HBV acquisition has been identified as a major driver of HBV-associated glomerulonephritis.33,34 HBV-related advanced liver disease may exacerbate renal dysfunction via haemodynamic changes and hepatorenal syndrome.35 Additional epidemiological studies comparing renal outcomes in persons with HBV, HIV and HBV/HIV are needed to better understand the development and prevention of CKD in these populations.

In this study we examined changes in eGFR over 3 years in a longitudinal cohort of Tanzanian adults with HIV, HBV or HBV/HIV coinfection, and assessed differences across the three groups. We hypothesized that eGFR would be lower in persons with HBV/HIV due to more advanced immunosuppression and other virus-specific factors.

Methods

Study design and population

The analysis was conducted using longitudinal data collected from adults with HIV, HBV or HBV/HIV enrolled in a prospective cohort study of liver outcomes between September 2013 and December 2015 following written informed consent, which was subject to ethical reviews by the National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Northwestern University.36,37 Study participants were recruited from eight HIV Care and Treatment Clinics (CTCs) and an HBV clinic in Dar es Salaam. Study sites were supported by the Management and Development for Health (MDH) under the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Inclusion criteria were: (i) adults at least 18 years of age; (ii) known HIV and HBV status; and (iii) antiretroviral (HIV, HBV/HIV) or antiviral (HBV) treatment naive. Chronic HBV was defined as hepatitis B surface antigen seropositivity on at least one occasion within the past 6 months. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or had active TB, positive anti-hepatitis C antibody, known history of hepatocellular carcinoma, or clinical evidence of advanced liver disease (jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, abnormal bleeding).36

Clinical protocols and participant follow-up

Participants were followed for 3 years after enrolment with annual study visits. Comprehensive history, examination and laboratory testing were performed at each visit. At the time of this study, clinical care of all PWH and HBV/HIV coinfection followed the 2013 WHO guidelines, and 2012 and revised 2015 Tanzanian National ART guidelines.38–40 As part of routine clinical care, PWH and HBV/HIV were evaluated in the clinic monthly and received free refills and treatment-adherence counselling. PWH received semiannual clinical, immunological and virological monitoring and prophylaxis and treatment for opportunistic infections. Criteria for ART initiation included: (i) WHO HIV-related stages 3 (chronic HIV infection) and 4 (severely symptomatic HIV infection), regardless of CD4+ T cell count; (ii) CD4+ T cell count < 500 cells/mm3, regardless of WHO stage.38–40 ART containing at least two anti-HBV agents, such as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and lamivudine or emtricitabine, was recommended in all participants with HBV/HIV, regardless of CD4+ T cell count or WHO stage.38–40 The recommended first-line ART regimen was the fixed-dose combination efavirenz/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; alternative regimens included zidovudine/lamivudine/efavirenz, zidovudine/lamivudine/nevirapine and abacavir/lamivudine/lopinavir/ritonavir. Patients with chronic HBV were all initiated on lamivudine at enrolment according to local clinic protocols, as no national guidelines on HBV were available at the time. HBV DNA, HBeAg/anti-HBe and often ALT were also not routinely available and therefore not used to make any treatment decisions. Participants were followed monthly in clinic, and offered the option to switch to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine when it became more widely available in Tanzania after 2014.

Laboratory tests performed for the study included: CD4+ T cell count (baseline only); HIV RNA quantification [Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 monitor test v2.0 (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN, USA; lower limit of detection 20 copies/mL)]; haemoglobin; platelets; AST; ALT; creatinine (Roche Cobas Integra 400+ Analyser); HBsAg (ABON HBsAg rapid test); HBeAg/anti-HBe (EIA assay Cobas e411); and HBV DNA (COBAS AmpliPrep TaqMan 96, v2.0; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany; lower limit of detection 20 IU/mL). Testing was conducted at the MDH-supported Temeke Research Laboratory.

Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcome (eGFR) was determined using the CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (2021) without race factor, as has been validated in similar studies.41–43 For this analysis, we included any individual with at least one measure of serum creatinine at any point during four (baseline plus three follow-up) data collection visits from September 2013 to December 2018. CKD stages were defined using National Kidney Foundation eGFR thresholds.41 Liver fibrosis was assessed using AST to platelet ratio index (APRI).44 HIV and HBV virologic suppression were defined as HIV RNA <20 copies/mL and HBV DNA <20 IU/mL, the lower limits of detection, respectively. Deaths were recorded after notification by family members, friends or the participant-tracking team. Data collected to the point of withdrawal or last visit were included in analysis: by the study end, 47 participants had died (HBV: 4; HIV: 30; HBV/HIV: 13), 38 had withdrawn or moved away (HBV: 4; HIV: 26; HBV/HIV: 8) and 73 were lost to follow-up (HBV: 51; HIV: 18; HBV/HIV: 4).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to compare groups according to potential confounders. The nephro package was used for determination of CKD stages.45 Mixed-effects models with random intercept for person were created to model eGFR over time and across groups and adjusted for potential confounders.46 Models did not adjust for baseline eGFR as the primary goal was to detect any differences in eGFR over time across groups (Figure S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). All models used second-degree polynomial terms for time, which was interacted with the group variable. In sensitivity analyses, we repeated models comparing eGFR across groups to include a random slope term for time. To facilitate comparisons, the emmeans package was used to calculate the marginal means per group at each timepoint and the differences across or within groups.47 Multivariable analyses were conducted with complete cases then repeated with multiple imputation for missing values using the mice package48 (see Supplementary Methods). HIV RNA and HBV DNA values <20 were imputed as 20 for the purpose of the analysis. Analyses were performed using R 4.3/RStudio.

Results

Five hundred and three participants were enrolled during the study period; four were missing all creatinine measures and excluded from final analysis. Of the remaining 499 participants, 164 (32.9%) had HBV, 271 (54.3%) had HIV and 64 (12.8%) had HBV/HIV (Table 1). All participants with HBV were initiated on lamivudine and 266 (98.2%) and 62 (96.9%) of participants with HIV and HBV/HIV, respectively, on a tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-containing regimen. Participants were followed for a median of 36.0 months (IQR 18.0–36.0) [(HBV: 35.0 (12.8–36.0); HIV: 36.0 (26.0–37.0); HIV/HBV: 34.5 (8.0–36.0); P = 0.009]. Participants with HBV were younger [HBV: 33.16 years (SD 8.98); HIV: 38.73 (10.01); HBV/HIV: 37.14 (12.38); P < 0.001], more likely to be male (HBV: 65.9%; HIV: 28.8%; HBV/HIV: 48.4%; P < 0.001) and had a higher baseline BMI [HBV: 25.15 kg/m2 (SD 4.81); HIV 22.73 (4.96); HBV/HIV 22.24 (4.23); P < 0.001]. Baseline mean eGFR values were similar across groups [HBV: 106.88 mL/min/1.73 m2 (SD 19.64); HIV: 106.03 (23.17); HBV/HIV: 107.18 (28.76); P = 0.898]. Baseline mean APRI was highest in participants with HBV/HIV [HBV: 0.77 (SD 2.47), HIV: 0.35 (0.50), HBV/HIV: 1.00 (2.60); P = 0.008].

Table 1.

Characteristics over 3 years by group

| Characteristic | All participants (N = 499) | HBV (n = 164) | HIV (n = 271) | HBV/HIV (n = 64) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at baseline, mean (SD) | 36.70 (10.32) | 33.16 (8.98) | 38.73 (10.01) | 37.14 (12.38) | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 217 (43.5) | 108 (65.9) | 78 (28.8) | 31 (48.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 23.47 (4.96) | 25.15 (4.81) | 22.73 (4.96) | 22.24 (4.23) | <0.001 |

| Year 1 | 25.37 (5.04) | 26.19 (4.88) | 25.02 (5.14) | 24.50 (4.76) | 0.058 |

| Year 2 | 25.68 (5.33) | 25.88 (4.82) | 25.83 (5.70) | 24.16 (4.94) | 0.236 |

| Year 3 | 25.70 (5.07) | 25.63 (4.59) | 25.76 (5.32) | 25.53 (5.27) | 0.962 |

| Estimates of renal function | |||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 0.83 (0.36) | 0.88 (0.23) | 0.79 (0.40) | 0.84 (0.44) | 0.033 |

| Year 1 | 0.81 (0.23) | 0.91 (0.21) | 0.76 (0.22) | 0.71 (0.23) | <0.001 |

| Year 2 | 0.79 (0.23) | 0.88 (0.21) | 0.74 (0.22) | 0.75 (0.27) | <0.001 |

| Year 3 | 0.84 (0.21) | 0.93 (0.20) | 0.80 (0.21) | 0.75 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| CKD-EPI (2021) eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 106.45 (22.85) | 106.88 (19.64) | 106.03 (23.17) | 107.18 (28.76) | 0.898 |

| Year 1 | 105.43 (20.90) | 102.43 (19.26) | 105.12 (21.19) | 115.71 (21.52) | 0.001 |

| Year 2 | 105.82 (21.02) | 104.35 (20.24) | 105.78 (21.57) | 110.73 (20.62) | 0.282 |

| Year 3 | 100.97 (19.63) | 100.01 (18.91) | 100.36 (20.66) | 108.45 (13.55) | 0.106 |

| CKD stage at baseline, n (%) | |||||

| 1 | 397 (79.7) | 133 (81.1) | 214 (79.3) | 50 (78.1) | 0.324a |

| 2 | 82 (16.5) | 29 (17.7) | 45 (16.7) | 8 (12.5) | |

| 3a | 11 (2.2) | 2 (1.2) | 5 (1.9) | 4 (6.2) | |

| 3b | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.6) | |

| 4 | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.6) | |

| 5 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| APRI score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.56 (1.71) | 0.77 (2.47) | 0.35 (0.50) | 1.00 (2.60) | 0.008 |

| Year 1 | 0.33 (0.22) | 0.34 (0.16) | 0.32 (0.25) | 0.33 (0.25) | 0.657 |

| Year 2 | 0.32 (0.26) | 0.36 (0.32) | 0.30 (0.23) | 0.29 (0.18) | 0.098 |

| Year 3 | 0.31 (0.19) | 0.33 (0.17) | 0.30 (0.21) | 0.29 (0.17) | 0.271 |

| HIV parameters | |||||

| HIV RNA (copies/mL), median (IQR) | |||||

| Baseline | 90163.00 (27961.50–266943.00) | NA | 96536.50 (35717.25–275191.75) | 57035.00 (5689.00–249926.00) | 0.026 |

| Year 1 | 20.00 (20.00–58.00) | NA | 20.00 (20.00–65.00) | 20.00 (20.00–20.25) | 0.217 |

| Year 2 | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | NA | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 0.350 |

| Year 3 | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | NA | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 0.552 |

| HIV suppressed (≤20 copies/mL), n (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 4 (1.3) | NA | 1 (0.4) | 3 (5.3) | 0.024a |

| Year 1 | 155 (64.3) | NA | 122 (61.9) | 33 (75.0) | 0.144 |

| Year 2 | 170 (82.1) | NA | 142 (81.1) | 28 (87.5) | 0.540 |

| Year 3 | 172 (85.1) | NA | 148 (84.6) | 24 (88.9) | 0.767a |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) at baseline, mean (SD) | 240.53 (177.33) | NA | 237.16 (170.63) | 256.65 (207.41) | 0.459 |

| HBV parameters | |||||

| HBV DNA (IU/mL), median (IQR) | |||||

| Baseline | 634.00 (38.25–10217.50) | 613.00 (61.00–4567.00) | NA | 655.00 (20.00–580006.50) | 0.254 |

| Year 1 | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | NA | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 0.902 |

| Year 2 | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | NA | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 0.806 |

| Year 3 | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | NA | 20.00 (20.00–20.00) | 0.056 |

| HBV suppressed (≤20 IU/mL), n (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 50 (22.1) | 33 (20.2) | NA | 17 (27.0) | 0.360 |

| Year 1 | 138 (79.3) | 104 (79.4) | NA | 34 (79.1) | 1 |

| Year 2 | 120 (82.8) | 91 (82.7) | NA | 29 (82.9) | 1 |

| Year 3 | 115 (89.8) | 89 (87.3) | NA | 26 (100.0) | 0.120a |

| HBeAg positive, n (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 38 (16.7) | 16 (9.8) | NA | 22 (34.4) | <0.001 |

| Year 1 | 15 (8.6) | 4 (3.1) | NA | 11 (25.0) | <0.001a |

| Year 2 | 12 (8.0) | 6 (5.3) | NA | 6 (16.2) | 0.076a |

| Year 3 | 7 (5.3) | 4 (3.8) | NA | 3 (10.7) | 0.335a |

| HBeAb positive, n (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 213 (93.4) | 162 (98.8) | NA | 51 (79.7) | <0.001a |

| Year 1 | 161 (92.0) | 127 (96.9) | NA | 34 (77.3) | <0.001a |

| Year 2 | 144 (96.0) | 113 (100.0) | NA | 31 (83.8) | <0.001a |

| Year 3 | 124 (93.9) | 104 (100.0) | NA | 20 (71.4) | <0.001 |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-containing regimen, n (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 328 (65.7) | 0 (0) | 266 (98.2) | 62 (96.9) | <0.001 |

| Year 3 | 335 (98.2) | 105 (100.0) | 197 (97.0) | 39 (100.0) | 0.107a |

NA = not applicable. Additional data on CKD stages by group at Years 1, 2 and 3 visits are available in Table S3.

aThe chi-squared approximation may be incorrect due to missing data.

Among participants with HIV (without or with HBV), baseline mean CD4 counts were similar [HIV: 237.16 cells/mm3 (SD 170.63); HBV/HIV: 256.65 (207.41); P = 0.459]. Participants with HIV alone had a higher baseline median HIV RNA [HIV: 5.0 log10 copies/mL (IQR 4.6–5.4); HBV/HIV: 4.8 (3.8–5.4); P = 0.026]. By Year 3, 148 (84.6%) and 24 (88.9%) of participants with HIV and HBV/HIV achieved HIV virological suppression, respectively. Among participants with HBV (without or with HIV), baseline median HBV DNA levels were similar [HBV: 2.8 log10 copies/mL (IQR 1.8–3.7); HBV/HIV 2.8 (1.3–5.8); P = 0.254]. By Year 3, 89 (87.3%) and 26 (100.0%) of participants with HBV and HBV/HIV achieved HBV virological suppression. Participants with HBV had lower HBeAg and higher anti-HBe positivity rates than those with coinfection at baseline and follow-up visits.

Comparison of eGFR across and within participant groups over time

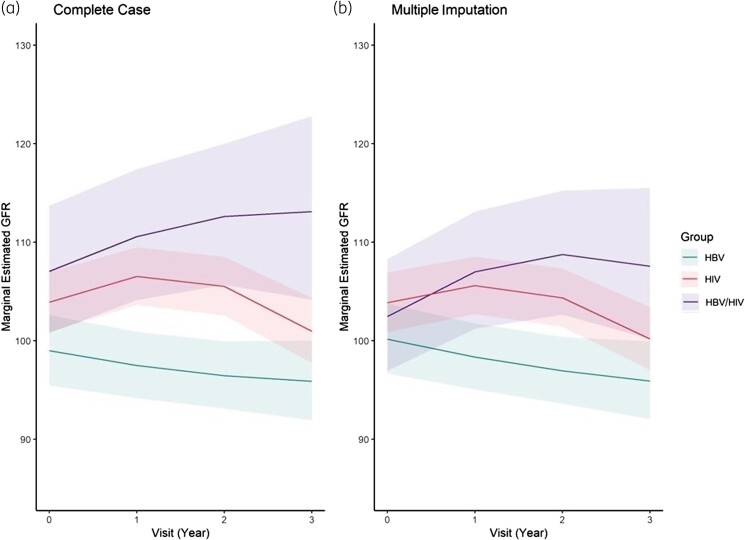

Using mixed-effects models, we compared eGFR across groups at each timepoint, adjusting for baseline age, sex, BMI at time of visit, and baseline APRI (Figure 1). Participants with HBV had lower eGFR measures than those with HIV or HBV/HIV at all three follow-up visits; differences were statistically significant except at Year 3 when comparing participants with HIV with those with HBV (Table 2). Findings were similar using multiple imputation and complete case analysis, as well as with inclusion of a random slope term for time using multiple imputation (Table S1 and Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Mixed-effects models of eGFR over time by group (HBV, HIV and HBV/HIV) using complete case analysis (left) and multiple imputation (right). x-axis = time (years); y-axis = eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2). Lines (with ribbons) represent mean eGFR (with 95% CI) for the group and time after multivariable adjustment.

Table 2.

Mixed-effects models of eGFR and differences (compared with participants with HBV) using multiple imputation (n = 499)

| Unadjusted eGFR (95% CI) | Adjusted eGFR (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| HBV | 104.4 (100.4–108.5) | 100.2 (96.7–103.8) | reference | |

| HIV | 102.3 (99.2–105.4) | 103.9 (100.9–106.9) | 3.7 (−2.1 to 9.5) | 0.296 |

| HBV/HIV | 102.6 (96.4–109.2) | 102.5 (96.9–108.3) | 2.3 (−5.7 to 10.3) | 0.779 |

| Year 1 | ||||

| HBV | 102.1 (98.3–106.0) | 98.3 (95.0–101.8) | reference | |

| HIV | 103.2 (100.1–106.3) | 105.6 (102.7–108.6) | 7.3 (1.7–12.8) | 0.006 |

| HBV/HIV | 107.0 (100.4–114.1) | 107.0 (101.2–113.1) | 8.7 (0.5–16.8) | 0.035 |

| Year 2 | ||||

| HBV | 100.5 (96.7–104.5) | 96.9 (93.6–100.4) | reference | |

| HIV | 101.6 (98.5–104.8) | 104.3 (101.4–107.3) | 7.4 (1.8–13.0) | 0.005 |

| HBV/HIV | 108.3 (101.4–115.7) | 108.8 (102.6–115.2) | 11.8 (3.3–20.4) | 0.004 |

| Year 3 | ||||

| HBV | 99.5 (95.2–104.1) | 95.9 (92.0–99.9) | reference | |

| HIV | 97.6 (94.4–101.0) | 100.2 (97.0–103.4) | 4.3 (−2 to 10.5) | 0.243 |

| HBV/HIV | 106.3 (98.1–115.1) | 107.6 (100.2–115.5) | 11.7 (1.4–22.0) | 0.022 |

Unadjusted model adjusts for time, group and random intercept for person. Adjusted model additionally adjusts for age (baseline), sex (baseline), BMI (at time of visit) and APRI (baseline). Similar findings were observed using complete case analysis (n = 440).

Using similar methods, we compared eGFR within groups over time, adjusting for baseline age, sex, BMI at time of visit, and baseline APRI. From baseline to Year 3, mean eGFR declined by 4.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI −9.3 to 0.7) and 3.7 (−7.8 to 0.5) in participants with HBV and HIV, respectively, and increased by 5.1 (−4.7 to 14.9) in those with HBV/HIV; however, none of these changes were statistically significant (Table S2). Analogously, the proportion of participants with CKD stage 2 (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) increased in the HBV and HIV groups (17.7%–25.0% and 16.7%–26.8%, respectively) and decreased in the HBV/HIV group (12.5%–10.7%) from baseline to Year 3 (Table S3). In multivariable analyses of risk factors associated with eGFR, only older age was also associated with lower eGFR (beta −0.11; 95% CI −0.13 to −0.092; P < 0.0001). Male sex (0.02; −0.01 to 0.058; P = 0.2298), BMI (−0.02; −0.03 to 0; P = 0.0552) and APRI (−0.01; −0.02 to 0; P = 0.0624) were not associated with eGFR.

Subgroup analyses

We conducted further subgroup analyses to examine whether coinfection with HIV or HBV was associated with greater eGFR declines compared with either infection alone after adjusting for viral factors. In mixed-effect models comparing participants with HIV and HBV/HIV there were no significant differences in eGFR at any visit, adjusting for baseline HIV RNA (log-transformed), CD4 (square root), age, sex, BMI and APRI (Table S4). In the multivariable model using multiple imputation, older age was associated with lower eGFR (beta −0.12; 95% CI −0.14 to −0.10; P < 0.0001) and higher CD4 count with higher eGFR (beta 0.00; 95% CI 0.00–0.01; P = 0.0479). HIV RNA was not associated with eGFR.

When comparing participants with HBV and HBV/HIV, we observed significantly lower eGFRs among persons with HBV monoinfection at all visits, adjusting for baseline HBV DNA (log-transformed), HBeAg status, age, sex, BMI and APRI, corroborating findings in the overall model (Table S4). In the multivariable model using multiple imputation, older age was again associated with lower eGFR; HBV DNA and HBeAg status were not associated with eGFR.

Discussion

In this large Tanzanian cohort of adults with HIV, HBV or HBV/HIV, renal dysfunction was uncommon in all three groups and only small changes in eGFR were observed over the three years following antiviral initiation. Fewer than 4% had CKD stage 3 or greater at either baseline or Year 3 visits (Table S3). Contrary to expectations, HBV/HIV coinfection was not associated with any worsening of eGFR; in fact, slight improvements in eGFR were observed in persons with HIV and HBV/HIV, whereas continued declines were seen in those with HBV. These changes over time were not significant. Notably, persons with HBV had lower eGFRs compared with persons with HIV and HBV/HIV throughout follow-up.

In both persons with HIV and HBV/HIV, early improvements in eGFR were observed, followed by a return to baseline levels in those with HIV. We hypothesize that these initial improvements, also observed in other studies conducted in SSA,19,49–52 were caused by decreased HIV viraemia and infection of renal epithelial cells, thereby reducing systemic and renal interstitial (as is present in HIVAN) inflammation.53–58 Simultaneous declines in APRI following ART initiation, particularly among persons with HBV/HIV, suggest that decreased inflammation through HIV viraemia reduction may galvanize (some) recovery in organ function.59,60 Some studies have observed progressive declines in eGFR despite ART; however, these may be indicative of more chronic damage from comorbidities, nephrotoxic drugs and intermittent viraemia.26,61 Other explanations for the divergent results include differences in patient populations (LMIC versus HIC) and type of study (increased representation of HIVAN in prospective cohorts initiating ART versus CKD due to other comorbidities in retrospective cohorts).29

Several studies have reported inverse associations between HIV viraemia and eGFR;55,56,62,63 however, we did not observe an independent effect of HIV RNA level on eGFR in subgroup analysis of participants with HIV and HBV/HIV. A longitudinal cohort study conducted in the USA (Choi et al.61) similarly reported no association between viral load and eGFR in mixed-effects models adjusted for baseline age, sex, race, time-updated viral load, CD4 count, ART use and comorbidities. A consistent relationship between CD4 count and eGFR has also not been established across studies; although Choi et al. found no association between CD4 and eGFR, Reid et al.49 and Mocroft et al.5 observed greater increases in eGFR in participants with higher baseline CD4 and lower odds of CKD progression in participants with higher CD4 nadir, respectively. We identified a similar positive association between CD4 and eGFR in participants with HIV and HBV/HIV.

In contrast to previous reports where coinfection with HBV has been associated with greater risk of renal dysfunction than HIV alone, we found no significant differences in eGFR between persons with HIV and HBV/HIV. In a Zambian study of 6789 PWH (11.8% with HBV/HIV), coinfection with HBV was associated with greater odds of eGFR < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 [adjusted OR (AOR) 1.96; 95% CI 1.34–2.86] than HIV alone, adjusting for age, sex, CD4 count and WHO clinical stage.6 Due to its cross-sectional design, the study was unable to assess changes in eGFR following ART initiation; data on viral load, infection duration and antiviral duration were also not available. Similarly, in a secondary analysis of 3441 PWH (3.3% with HBV/HIV) in Denmark, England and Australia, coinfection with HBV was associated with greater odds of progressive CKD (defined as end-stage renal disease, renal death, or 25% eGFR decline to a level or from a baseline of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) (AOR 2.26; 95% CI 1.15–4.44), adjusting for HIV parameters and antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapies.5 Due to a relatively small number of participants with HBV/HIV, however, they were unable to further investigate the role of HBV viraemia during follow-up (median 16 months and 7 years in the SMART and ESPRIT trials, respectively). Other prospective cohort studies of persons with HBV/HIV have also identified age (younger and older), male sex, higher BMI and previous AIDS-defining illness as risk factors for eGFR decline; in one of these studies, undetectable HBV DNA on treatment was found to be protective.64,65

Somewhat unexpectedly, in our study, participants with HBV had the largest, albeit small, declines in eGFR and significantly lower eGFRs at all follow-up visits compared with other groups, despite their younger age, higher baseline BMI and relatively short exposure to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [median 18.7 months (IQR 15.1–22.6)]. Large cohort studies of persons with chronic HBV in HICs have observed comparable declines in eGFR following tenofovir disoproxil fumarate initiation,66–71 and others comparing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with no treatment reported no differences in rates of renal dysfunction over time.24,25 Risk of eGFR loss despite HBV treatment has been associated with baseline renal dysfunction, age, diabetes, hypertension and diuretic use.66,68–71 We similarly observed a significant inverse association between age and eGFR in participants with HBV monoinfection. HBV duration (which we were unable to measure) may be an important contributor to eGFR declines. Early childhood acquisition is the most common route of HBV transmission in SSA, therefore it is likely that participants in our study had been living with HBV for some time and eGFR declines were more age-related. In a Cameroonian cross-sectional study of persons with chronic HBV (1.8% had HBV/HIV), in addition to older age and use of traditional herbs, longer duration of HBV was associated with eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (AOR 2.00; 95% CI 1.04–3.88); coinfection with HIV was not included in multivariable analysis.22

Few studies (and to our knowledge none in SSA) have compared eGFR in persons with HBV monoinfection with those with HBV/HIV or HIV. In an Italian cohort of 34 participants with HBV and 44 with HBV/HIV who initiated tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and were followed for 5 years, a larger decline in eGFR (104–81 mL/min/1.73 m2) was observed in those with HBV using generalized linear mixed models adjusted for exposure to nephrotoxic drugs (ACE inhibitors, cyclosporine and diuretics) and comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, cirrhosis).72 Age was not included in the model and may have been a confounder as median age was higher in the HBV group. In a French cohort of 50 participants with HBV, 194 with HIV, and 85 with HBV/HIV who initiated tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and were followed for 2.7 years, participants with HBV had lower eGFRs at baseline and last follow-up (93–87 mL/min/1.73 m2).73 Declines in eGFR were associated with older age, non-African origin, higher baseline eGFR and longer tenofovir disoproxil fumarate administration—but not type of infection. In subgroup analysis of participants with HBV and HBV/HIV, HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL was associated with eGFR decline. In our study, HBV DNA level and HBeAg positivity were not independently associated with changes in eGFR in participants with HBV and HBV/HIV, perhaps due to lack of power in the setting of study attrition over time.

To our knowledge, this is the largest longitudinal cohort study comparing renal outcomes among persons with HBV, HIV and HBV/HIV. As with other studies, we observed an inverse association between age and eGFR. In fact, this was the only risk factor that was independently associated with eGFR in our cohort across all models after adjusting for other confounders. Older age is a well-known risk factor for renal dysfunction observed in both LMICs and HICs and in populations with and without HIV.6,13,30,52,74,75 Due to a lack of available data, we were unable to examine the role of other comorbidities associated with renal dysfunction (e.g. duration of HIV or HBV infection, diabetes, hypertension, hepatitis C coinfection, nephrotoxic medications and area deprivation index).28,61,76,77 Treatment adherence was not measured in this study but was unlikely to have explained differences in eGFR between participants with HBV and HBV/HIV at follow-up due to comparable rates of HBV virological suppression (Table 1), even at Year 1, and adjustment for HBV DNA level in subgroup analysis (Table S4). We were unable to account for the effect of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate exposure on eGFR in HBV participants, as almost all switched to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine by Year 3. Thus, not enough participants remained on a non-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-containing regimen to serve as a control. In addition, we were unable to model eGFR before and after switch to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HBV participants using an interrupted time-series approach as this requires multiple pre-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate measurements, which were not available in our data. Longer-term assessments are needed to examine the effects of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and comorbidities on changes in renal function. Finally, we caution that changes in renal function may not be accurately reflected by serum creatinine and eGFR, especially in PWH.78 Future studies including 24 h urine collection for creatinine clearance are needed to help differentiate clinically insignificant changes in serum creatinine and eGFR from true renal dysfunction.

Conclusions

In this Tanzanian cohort of persons with HIV, HBV and HBV/HIV, we observed no significant changes in eGFR following treatment initiation; furthermore, HBV/HIV coinfection did not adversely impact eGFR compared with either infection alone. The relatively lower eGFRs among persons with HBV monoinfection highlight a need for closer monitoring of renal function, as well as HBV parameters in this population, in addition to longer-term studies examining risk factors associated with renal dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff and clients at the MDH-supported HIV Care and Treatment clinics in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. We are also grateful for the valuable contributions made by the late Guerino Chalamilla, founding CEO of MDH, to the design and conduct of this study.

Contributor Information

En-Ling Wu, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA; Section of Infectious Diseases and Global Health, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Beatrice Christian, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Adovich S Rivera, Institute for Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA; Division of Epidemiologic Research, Department of Research and Evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA, USA.

Emanuel Fabian, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Irene Macha, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Eric Aris, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Shida Mpangala, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Nzovu Ulenga, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Ferdinand Mugusi, Management and Development for Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Robert L Murphy, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA; Havey Institute for Global Health, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Claudia A Hawkins, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA; Havey Institute for Global Health, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Funding

The work was supported by grant K23 DK095707 from the National Institute of National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), the Robert J. Havey, MD Institute for Global Health at Northwestern University, and the Richard and Susan Kiphart Northwestern Global Health Research Fund. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the funding institutions.

Transparency declarations

C.H. has received honoraria from Janssen Pharmaceutica. For the remaining authors, no conflicts of interest were declared.

Supplementary data

Figures S1 and S2 and Tables S1 to S4 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. 2022. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update-summary_en.pdf.

- 2. Barth RE, Huijgen Q, Taljaard J et al. Hepatitis B/C and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: an association between highly prevalent infectious diseases. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14: e1024–31. 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT et al. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 1546–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson RJ, Couser WG. Hepatitis B infection and renal disease: clinical, immunopathogenetic and therapeutic considerations. Kidney Int 1990; 37: 663–76. 10.1038/ki.1990.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mocroft A, Neuhaus J, Peters L et al. Hepatitis B and C co-infection are independent predictors of progressive kidney disease in HIV-positive, antiretroviral-treated adults. PLoS One 2012; 7: e40245. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mweemba A, Zanolini A, Mulenga L et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus coinfection is associated with renal impairment among Zambian HIV-infected adults. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59: 1757–60. 10.1093/cid/ciu734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Naicker S, Rahmanian S, Kopp JB. HIV and chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol 2015; 83: 32–8. 10.5414/CNP83S032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mulenga LB, Kruse G, Lakhi S et al. Baseline renal insufficiency and risk of death among HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS 2008; 22: 1821–7. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328307a051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Msango L, Downs JA, Kalluvya SE et al. Renal dysfunction among HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2011; 25: 1421–5. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328348a4b1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cailhol J, Nkurunziza B, Izzedine H et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease among people living with HIV/AIDS in Burundi: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2011; 12: 40. 10.1186/1471-2369-12-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarfo FS, Keegan R, Appiah L et al. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and association with risk of death amongst HIV-infected Ghanaians. J Infect 2013; 67: 43–50. 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anyabolu EN, Chukwuonye II, Arodiwe E et al. Prevalence and predictors of chronic kidney disease in newly diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus patients in Owerri, Nigeria. Indian J Nephrol 2016; 26: 10–5. 10.4103/0971-4065.156115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ekrikpo UE, Kengne AP, Akpan EE et al. Prevalence and correlates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among ART-naive HIV patients in the Niger-Delta region of Nigeria. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e0380. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaboré NF, Poda A, Zoungrana J et al. Chronic kidney disease and HIV in the era of antiretroviral treatment: findings from a 10-year cohort study in a west African setting. BMC Nephrol 2019; 20: 155. 10.1186/s12882-019-1335-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anabire NG, Tetteh WJ, Obiri-Yaboah D et al. Evaluation of hepatic and kidney dysfunction among newly diagnosed HIV patients with viral hepatitis infection in Cape Coast, Ghana. BMC Res Notes 2019; 12: 466. 10.1186/s13104-019-4513-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stanifer JW, Jing B, Tolan S et al. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2: e174–81. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ekrikpo UE, Kengne AP, Bello AK et al. Chronic kidney disease in the global adult HIV-infected population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0195443. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. George JA, Brandenburg JT, Fabian J et al. Kidney damage and associated risk factors in rural and urban sub-Saharan Africa (AWI-Gen): a cross-sectional population study. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e1632–43. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30443-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mpondo BC, Kalluvya SE, Peck RN et al. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on renal function among HIV-infected Tanzanian adults: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e89573. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stanifer JW, Maro V, Egger J et al. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in Northern Tanzania: a population-based survey. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0124506. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mwemezi O, Ruggajo P, Mngumi J et al. Renal dysfunction among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nephrol 2020; 2020: 8378947. 10.1155/2020/8378947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patrice HM, Albert EBS, Jean Pierre NM et al. Chronic kidney disease amongst patients with chronic hepatitis B virus in a low income country setting. J Nephrol Ther 2019; 9: 2. 10.37421/jnt.2019.9.325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen Y-C, Su Y-C, Li C-Y et al. 13-Year nationwide cohort study of chronic kidney disease risk among treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B in Taiwan. BMC Nephrol 2015; 16: 110. 10.1186/s12882-015-0106-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong GL-H, Chan HL-Y, Tse Y-K et al. Chronic kidney disease progression in patients with chronic hepatitis B on tenofovir, entecavir, or no treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48: 984–92. 10.1111/apt.14945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang T, Smith DA, Campbell C et al. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) viral load, liver and renal function in adults treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. untreated: a retrospective longitudinal UK cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 610. 10.1186/s12879-021-06226-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV-positive patients. AIDS 2010; 24: 1667–78. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339fe53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scherzer R, Estrella M, Li Y et al. Association of tenofovir exposure with kidney disease risk in HIV infection. AIDS 2012; 26: 867–75. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351f68f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ryom L, Mocroft A, Kirk O et al. Association between antiretroviral exposure and renal impairment among HIV-positive persons with normal baseline renal function: the D:A:D study. J Infect Dis 2013; 207: 1359–69. 10.1093/infdis/jit043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tourret J, Deray G, Isnard-Bagnis C. Tenofovir effect on the kidneys of HIV-infected patients: a double-edged sword? J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1519–27. 10.1681/ASN.2012080857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hamzah L, Jose S, Booth JW et al. Treatment-limiting renal tubulopathy in patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J Infect 2017; 74: 492–500. 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kabore NF, Cournil A, Poda A et al. APOL1 renal risk variants and kidney function in HIV-1-infected people from sub-Saharan Africa. Kidney Int Rep 2022; 7: 483–93. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lai KN, Li PK, Lui SF et al. Membranous nephropathy related to hepatitis B virus in adults. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1457–63. 10.1056/NEJM199105233242103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levy M, Chen N. Worldwide perspective of hepatitis B-associated glomerulonephritis in the 80s. Kidney Int Suppl 1991; 35: S24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang R, Wu Y, Zheng B et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of hepatitis B associated membranous nephropathy and idiopathic membranous nephropathy complicated with hepatitis B virus infection. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 18407. 10.1038/s41598-021-98010-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang D, Yan X, Zhang M et al. Association between liver cirrhosis and estimated glomerular filtration rates in patients with chronic HBV infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e21387. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hawkins C, Christian B, Fabian E et al. Brief report: HIV/HBV coinfection is a significant risk factor for liver fibrosis in Tanzanian HIV-infected adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 76: 298–302. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Christian B, Fabian E, Macha I et al. Hepatitis B virus coinfection is associated with high early mortality in HIV-infected Tanzanians on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2019; 33: 465–73. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. The United Republic of Tanzania, National AIDS Control Programme . National Guidelines for the Management of HIV and AIDS. 2012.

- 39. WHO . Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241505727.

- 40. The United Republic of Tanzania, National AIDS Control Programme. National Guidelines for the Management of HIV and AIDS. 2015. https://www.childrenandaids.org/sites/default/files/2017-04/Tanzania_National-HIV-Guidelines_2015.pdf.

- 41. National Kidney Foundation . K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39: S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levey AS, Stevens LA. Estimating GFR using the CKD epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation: more accurate GFR estimates, lower CKD prevalence estimates, and better risk predictions. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 55: 622–7. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.02.337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cristelli MP, Cofán F, Rico N et al. Estimation of renal function by CKD-EPI versus MDRD in a cohort of HIV-infected patients: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 58. 10.1186/s12882-017-0470-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin Z-H, Xin Y-N, Dong Q-J et al. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology 2011; 53: 726–36. 10.1002/hep.24105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pattaro C, Fujii R, Herold J. nephro: Utilities for Nephrology. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nephro/index.html.

- 46. Leffondre K, Boucquemont J, Tripepi G et al. Analysis of risk factors associated with renal function trajectory over time: a comparison of different statistical approaches. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1237–43. 10.1093/ndt/gfu320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lenth RV, Bolker B, Buerkner P et al. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html.

- 48. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011; 45: 1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reid A, Stöhr W, Walker AS et al. Severe renal dysfunction and risk factors associated with renal impairment in HIV-infected adults in Africa initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46: 1271–81. 10.1086/533468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stöhr W, Reid A, Walker AS et al. Glomerular dysfunction and associated risk factors over 4–5 years following antiretroviral therapy initiation in Africa. Antivir Ther 2011; 16: 1011–20. 10.3851/IMP1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mulenga L, Musonda P, Mwango A et al. Effect of baseline renal function on tenofovir-containing antiretroviral therapy outcomes in Zambia. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 1473–80. 10.1093/cid/ciu117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kamkuemah M, Kaplan R, Bekker LG et al. Renal impairment in HIV-infected patients initiating tenofovir-containing antiretroviral therapy regimens in a primary healthcare setting in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2015; 20: 518–26. 10.1111/tmi.12446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Atta MG, Gallant JE, Rahman MH et al. Antiretroviral therapy in the treatment of HIV-associated nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21: 2809–13. 10.1093/ndt/gfl337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wyatt CM, Klotman PE, D’Agati VD. HIV-associated nephropathy: clinical presentation, pathology, and epidemiology in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Semin Nephrol 2008; 28: 513–22. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kalayjian RC, Franceschini N, Gupta SK et al. Suppression of HIV-1 replication by antiretroviral therapy improves renal function in persons with low CD4 cell counts and chronic kidney disease. AIDS 2008; 22: 481–7. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4706d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Longenecker CT, Scherzer R, Bacchetti P et al. HIV viremia and changes in kidney function. AIDS 2009; 23: 1089–96. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832a3f24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Estrella MM, Moosa MR, Nachega JB. Editorial commentary: risks and benefits of tenofovir in the context of kidney dysfunction in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 1481–3. 10.1093/cid/ciu123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hileman CO, Funderburg NT. Inflammation, immune activation, and antiretroviral therapy in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2017; 14: 93–100. 10.1007/s11904-017-0356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tadesse BT, Foster BA, Kabeta A et al. Hepatic and renal toxicity and associated factors among HIV-infected children on antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort study. HIV Med 2019; 20: 147–56. 10.1111/hiv.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zerbato JM, Avihingsanon A, Singh KP et al. HIV DNA persists in hepatocytes in people with HIV-hepatitis B co-infection on antiretroviral therapy. EBioMedicine 2023; 87: 104391. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Choi AI, Shlipak MG, Hunt PW et al. HIV-infected persons continue to lose kidney function despite successful antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2009; 23: 2143–9. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283313c91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Szczech LA, Gange SJ, van der Horst C et al. Predictors of proteinuria and renal failure among women with HIV infection. Kidney Int 2002; 61: 195–202. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Medapalli RK, Parikh CR, Gordon K et al. Comorbid diabetes and the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected adults: data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 60: 393–9. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825b70d9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Boyd A, Miailhes P, Lascoux-Combe C et al. Renal outcomes after up to 8 years of tenofovir exposure in HIV-HBV-coinfected patients. Antivir Ther 2017; 22: 31–42. 10.3851/IMP3076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gizaw A, King WC, Hinerman AS et al. A prospective cohort study of renal function and bone turnover in adults with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-HIV co-infection with high prevalence of tenofovir-based antiretroviral therapy use. HIV Med 2023; 24: 55–74. 10.1111/hiv.13322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shin J-H, Kwon HJ, Jang HR et al. Risk factors for renal functional decline in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving oral antiviral agents. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e2400. 10.1097/MD.0000000000002400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Marcellin P, Zoulim F, Hézode C et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in chronic hepatitis B: a 3-year, prospective, real-world study in France. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61: 3072–83. 10.1007/s10620-015-4027-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jung WJ, Jang JY, Park WY et al. Effect of tenofovir on renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e9756. 10.1097/MD.0000000000009756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Min IS, Lee CH, Shin IS et al. Treatment outcome and renal safety of 3-year tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with preserved glomerular filtration rate. Gut Liver 2019; 13: 93–103. 10.5009/gnl18183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zheng S, Liu L, Lu J et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a 2-year prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98: e17590. 10.1097/MD.0000000000017590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lim TS, Lee JS, Kim BK et al. An observational study on long-term renal outcome in patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J Viral Hepat 2020; 27: 316–22. 10.1111/jvh.13222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Milazzo L, Gervasoni C, Falvella FS et al. Renal function in HIV/HBV co-infected and HBV mono-infected patients on a long-term treatment with tenofovir in real life setting. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2017; 44: 191–6. 10.1111/1440-1681.12691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pradat P, Le Pogam MA, Okon JB et al. Evolution of glomerular filtration rate in HIV-infected, HIV-HBV-coinfected and HBV-infected patients receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J Viral Hepat 2013; 20: 650–7. 10.1111/jvh.12088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Woolnough EL, Hoy JF, Cheng AC et al. Predictors of chronic kidney disease and utility of risk prediction scores in HIV-positive individuals. AIDS 2018; 32: 1829–35. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rasmussen LD, May MT, Kronborg G et al. Time trends for risk of severe age-related diseases in individuals with and without HIV infection in Denmark: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Lancet HIV 2015; 2: e288–98. 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00077-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kalayjian RC, Lau B, Mechekano RN et al. Risk factors for chronic kidney disease in a large cohort of HIV-1 infected individuals initiating antiretroviral therapy in routine care. AIDS 2012; 26: 1907–15. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357f5ed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McGettigan P, Morales DR, Moreno-Martos D et al. Changing co-morbidity and increasing deprivation among people living with HIV: UK population-based cross-sectional study. HIV Med 2023; 24: 311–24. 10.1111/hiv.13389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yilma D, Abdissa A, Kæstel P et al. Serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rates in HIV positive and negative adults in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0211630. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.