Abstract

The structural integrity of the sperm flagellum is essential for proper sperm function. Flagellar defects can result in male infertility, yet the precise mechanisms underlying this relationship are not fully understood. CCDC181, a coiled-coil domain-containing protein, is known to localize on sperm flagella and at the basal regions of motile cilia. Despite this knowledge, the specific functions of CCDC181 in flagellum biogenesis remain unclear. In this study, Ccdc181 knockout mice were generated. The absence of CCDC181 led to defective sperm head shaping and flagellum formation. Furthermore, the Ccdc181 knockout mice exhibited extremely low sperm counts, grossly aberrant sperm morphologies, markedly diminished sperm motility, and typical multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella (MMAF). Additionally, an interaction between CCDC181 and the MMAF-related protein LRRC46 was identified, with CCDC181 regulating the localization of LRRC46 within sperm flagella. These findings suggest that CCDC181 plays a crucial role in both manchette formation and sperm flagellum biogenesis.

Keywords: Male infertility, CCDC181, MMAF, Spermiogenesis, Flagellum biogenesis

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of male infertility in the general population ranges from 9% to 15% (Barratt et al., 2017). Genetic anomalies, particularly mutations in structural proteins of the sperm flagella, are frequently implicated in male infertility (Touré et al., 2021). The manchette, a transient structure that surrounds the head of elongating spermatids, is essential for head shaping and protein delivery during spermatid elongation (O'Donnell & O'Bryan, 2014). The processes of head shaping and tail assembly in sperm deformation rely on intramanchette transport (IMT) and intraflagellar transport (IFT) (Nakayama & Katoh, 2020). IMT facilitates the transport of cargo proteins through the manchette to the base of the sperm flagellum, while IFT directs these proteins into the developing sperm flagellum (Lehti & Sironen, 2016).

Multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella (MMAF), characterized by coiled, short, bent, absent, and irregular flagella, are severe deformities leading to infertility in affected individuals (Ma et al., 2021, 2022, 2023; Zhang et al., 2020). Recent studies have identified 44 genes associated with MMAF (Ma et al., 2024), primarily encompassing the dynein axonemal heavy chain protein family, coiled-coil domain-containing (CCDC) protein family, cilia- and flagella-associated protein family, and other flagellum biogenesis- and morphogenesis-related proteins. Over the past decade, CCDC proteins have been extensively investigated for their multifunctional roles in male reproductive physiology. Notably, various genes, such as CCDC9, Ccdc33, Ccdc38, CCDC39, Ccdc40, Ccdc42, Ccdc62, Ccdc63, CCDC65, Ccdc87, Ccdc136, Ccdc146, Ccdc159, Ccdc172, and Ccdc189, have been implicated in spermatogenesis (Becker-Heck et al., 2011; Blanchon et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2021; Ge et al., 2024; Geng et al., 2016; Jreijiri et al., 2024; Kaczmarek et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2024; Sha et al., 2019; Tapia Contreras & Hoyer-Fender, 2019; Wang et al., 2018, 2023, 2024; Yamaguchi et al., 2014; Young et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022a). Previous research has reported that coiled-coil domain-containing protein 181 (CCDC181) is localized to the sperm flagella and basal regions of motile cilia, where it interacts with the manchette-associated protein HOOK1 for intramanchette transport to the axoneme of the developing sperm flagellum (Schwarz et al., 2017). At present, however, the role of CCDC181 in flagellum biogenesis remains unclear.

In the present study, Ccdc181 knockout mice exhibited abnormal manchette structures and characteristic manifestations of MMAF. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry identified the interacting proteins of CCDC181. Collectively, these findings highlight the specific role of CCDC181 in regulating spermatogenesis, with genetic deficiency leading to MMAF and male infertility in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse model

Ccdc181−/− mice were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, as reported in previous research (Liu et al., 2022). Briefly, guide RNAs (gRNA1 and gRNA2) targeting exon 2 to generate Ccdc181 knockout mice were transcribed in vitro (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AM1908, USA). These gRNAs were co-injected with Cas9 mRNAs into C57BL/6J zygotes. Genomic DNA samples were extracted from toe biopsies of the founder mice and analyzed for mutations by Sanger sequencing. Founder mice (F0 generation) heterozygous for the mutation of interest were backcrossed with wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice for at least one generation, with the resulting heterozygous offspring (F1 generation and beyond) intercrossed to produce biallelic Ccdc181 mutant mice (F2 generation and beyond) for experimental use. The mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the laboratory animal center of USTC. All animal experiments were performed following the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of USTC (approval No. USTCACUC25090122076). The sequences of the gRNAs and genotyping primers were: gRNA1, 5’-TGTCCCAAGTATTCAGCCGT-3’ and gRNA2, 5’-GGATCCAACGGCTGAATACT-3’; and Ccdc181−/− mouse genotyping, forward 5’-TCTCCAAAGGATGAGGCCTT-3’ and reverse 5’-TGGTTTGGAATCCTGGAAGG -3’.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA from tissue was extracted using TRIzol reagent, followed by cDNA synthesis using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, RR047A, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. PCR amplification was conducted using Phanta Flash Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, #P510, China). The PCR protocols were performed under the following conditions: 30 s at 98°C, 38 cycles of 10 s at 98°C, 3 s at 55°C, and 10 s at 72°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel, then subjected to Sanger sequencing. Beta-actin (Actb) was used as an internal control. The primers used were: Ccdc181, forward 5’-GGACTTGGAGTGGTTGATCA-3’ and reverse 5’-GCCTCATCCTTTGGAGAGTT-3’; and Actb, forward 5’-ACCAACTGGGACGACATGGAGAA-3’ and reverse 5’-TACGACCAGAGGCATACAGGGAC-3’.

Fertility test

A fertility test was conducted by mating one 8-week-old Ccdc181−/− male mouse with two 8-week-old WT female mice (C57BL/6J) for two months, as previously reported (Shi et al., 2023). A total of three Ccdc181−/− and three WT male mice were tested. The females were monitored for pregnancy, and litter dates and number of pups were recorded.

Mouse sperm counts, morphology, and motility

Sperm counts in 8-week-old mice were assessed by dissecting the epididymis in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubating the pieces at 37°C for 30 min to release the sperm, as reported in earlier research (Ma et al., 2022). Sperm released from the epididymis were counted using a hemocytometer under a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Japan). Sperm motility was determined by placing the epididymis in human tubal fluid containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, 16000-044, USA) at 37°C for 15 min, collecting the sperm-containing liquid, and applying computer-assisted semen analysis to assess motility, as described previously (Zhang et al., 2020). To assess sperm morphology, slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 5 min, washed with PBS, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). At least 200 spermatozoa from each mouse were examined to determine the percentage of morphologically abnormal spermatozoa, following previously described protocols (Ma et al., 2023).

Histological analyses of testicular and epididymal tissues

Testicular and epididymal tissues were prepared, as described previously (Liu et al., 2023). Fresh testicular and epididymal tissues were fixed in Bouin's solution or 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. Following paraffin embedding, tissues were sectioned at 5 µm and subjected to H&E staining for histological analysis. Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Japan) equipped with a Nikon DS-Ri1digital camera (Nikon, Japan).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis

Samples were prepared as reported in our previous study (Ma et al., 2021). Briefly, fresh semen samples were obtained and centrifuged at 400 ×g for 3 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS three times, spermatozoa were fixed in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) containing 4% PFA, 8% glutaraldehyde, and 0.2% picric acid at 4°C overnight. After four washes with 0.1 mol/L PB, the samples were post-fixed with 1% OsO4, dehydrated, and then infiltrated with an acetone and Epon resin mixture. Samples were embedded and sectioned into ultrathin slices (70 nm) before staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The ultrastructure of the samples was examined and imaged using a Tecnai 10 or 12 microscope (Philips, Netherlands) at 100 kV or 120 kV, or an H-7650 microscope (Hitachi, Japan) at 100 kV.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was conducted according to previously described protocols (Gong et al., 2022). Briefly, mouse sperm were collected from the epididymis, washed three times in PBS, and spread onto glass slides. The slides were air dried, fixed with 4% PFA, and stored at −80°C until use. For immunofluorescence staining, slides were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with 3% skim milk. They were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, followed by secondary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h, and mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, H-1000, USA) containing Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, H21492, USA). The primary antibodies included anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, F2168, 1:200, USA), anti-CCDC181 (Sigma, HPA027281, 1:100, USA), anti-DNAH6 (Abcam, ab122333, 1:100, USA), anti-CFAP61 (Sigma, HPA009079, 1:100, USA), anti-SPAG6 (Proteintech, 12462-1-AP, 1:100, USA), anti-LRRC46 (NOVUS, NBP2-62692, 1:200, USA), anti-DNAH17 (ABclonal Biotechnology, 1:200, China), and anti-SOX9 (Sigma-Aldrich, AB5535, 1:100, USA). Fluorescence images were captured using an Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus, Japan) equipped with a scientific complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor camera (Prime BSI, Teledyne Photometrics, USA) and processed with Olympus cellSens imaging software (v.1.16).

TUNEL assay

The TUNEL assay was conducted according to previously described protocols (Xu et al., 2022). Testis sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (100%, 95%, 90%, 80%, 70%, 50% ethanol, and sterile water), and permeabilized with proteinase K (20 mg/mL) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 20 min at room temperature. After two PBS washes, TUNEL reagent mix (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein, Roche, 11684795910, Switzerland) was applied to each slide, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The sections were then washed with PBST three times and mounted in VECTASHIELD mounting medium (H-1000, Vector Laboratories, USA) containing Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, H21492, USA). Images were captured using an Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus, Japan) equipped with a scientific complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor camera (Prime BSI, Teledyne Photometrics, USA) and processed with Olympus cellSens imaging software (v.1.16).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were cultured as described in previous research (Xie et al., 2022) and transfected with P-N1 plasmids expressing CCDC181 protein tagged with Flag using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, L3000015, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested for immunoblotting at 36 h after transfection.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed, as described previously (Zhang et al., 2020). Briefly, cultured cells were lysed using Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, B0008, USA) with NuPAGE Antioxidant (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, NP0005, USA) and boiled for 10 min. The proteins extracted from the testes and sperm were prepared using lysis buffer (50 m mol/L Tris, 150 m mol/L NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 5 m mol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 7.5) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Solarbio, P6730, China). After tissue grinding and ultrasonication, the protein lysates were centrifuged at 16 000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant of the extracts was used for immunoblotting. The proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk overnight and incubated with corresponding primary and secondary antibodies.

Transfection and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) in cultured cells

HEK293T cells were plated in six-well plates and transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), as described previously (Zhang et al., 2021b). After 48 h of culture, proteins were isolated from harvested cells lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCL pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% TritonX-100, and 2.5 mmol/L EDTA) supplemented with 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 36978, USA) and 2 mmol/L protease inhibitor cocktail (Solarbio, P6730, USA). Proteins were then incubated with anti-GFP Nanobody-Magarose (Alpalifebio, KTSM1334, China) for 8 h at 4°C with gentle rotation. After three washes with IP buffer, the captured protein complexes were lysed in 1×SDS sample buffer (100 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 2% SDS, 15% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 5 mmol/L dithiothreitol), then denatured with boiling beads for 10 min. Finally, co-IP protein complexes were detected via western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry

Immunoprecipitation was conducted following previously described protocols (Gao et al., 2020). Testes were lysed in cold immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCL pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% TritonX-100, and 2.5 mmol/L EDTA) supplemented with 1 mmol/L PMSF (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 36978, USA). The lysates were sonicated for 10 cycles (2 s on/off) with 8% pulses and centrifuged at 17 000 ×g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was divided into two aliquots, which were each incubated with pre-cleared protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz, sc-2003, B23202, USA) and 1.5 μL of anti-CCDC181 antibody (Sigma, HPA027281, 1:200, USA) or anti-rabbit IgG (ABclonal, AC005, USA). Following overnight incubation at 4°C, the agarose beads were washed six times in IP buffer, with the immunocomplexes then dissociated from the beads with elution buffer (0.2 mol/L glycine, 0.15% NP-40, pH 2.3). The eluted samples were validated by silver staining and subsequently analyzed by mass spectrometry at the National Center for Protein Science Shanghai (China). Candidate interacting proteins of CCDC181 are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Homology and phylogenetic analysis

Homologous nucleotide and protein sequences were identified using the BLASTn and BLASTx search algorithms in NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/blast). Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences were performed using MUSCLE and refined with GBLOCKS. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the maximum-likelihood algorithm in MEGA (v.6.0) using a WAG model based on the MUSCLE-analyzed amino acid sequences.

Domain and conserved motif analysis

The NCBI Conserved Domain Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) was used to predict protein domains of CCDC181. MEME (Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation) motif discovery tools (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) were employed to predict conserved motifs of CCDC181 across 12 species, including Homo sapiens (NP_001287898.1), Mus musculus (NP_083391.2), Sus scrofa (NP_001231725.1), Bos taurus (NP_001192730.1), Oryctolagus cuniculus (XP_008262298.1), Capra hircus (XP_005690674.1), Cebus imitator (XP_017389591.1), Alligator sinensis (XP_006029511.1), Anas platyrhynchos (XP_027305367.1), Columba livia (PKK32404.1), Danio rerio (NP_001122012.1), and Xenopus tropicalis (XP_017947041.1). Each motif was required to be recognized in at least two sequences.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times, with error bars presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism v.9.0.0 using Student's t-test with paired two-tailed distribution. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05 (*), 0.01 (**), 0.001 (***), or 0.0001 (****).

RESULTS

CCDC181 is predominantly expressed in the testis

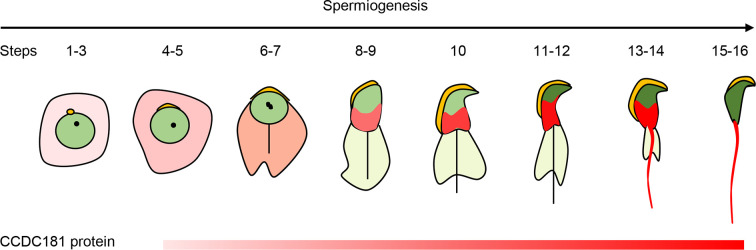

To explore the molecular functions of CCDC181 in spermatogenesis, we first investigated its expression and localization. Analysis of various tissues revealed that CCDC181 was predominantly expressed in the testes (Supplementary Figure S1A). Immunoblotting of mouse testicular lysates at different postnatal days showed CCDC181 expression from postnatal day 20 (PD20) to PD56 (Supplementary Figure S1B). This period coincides with the onset of spermiogenesis, suggesting a potential role for CCDC181 in this process. Furthermore, immunofluorescence was conducted to examine the expression and localization of CCDC181 in developing mouse spermatids. From steps 1 to 7 of spermatid development, CCDC181 exhibited diffuse cytoplasmic staining. As the spermatids elongated from steps 8 to 14, CCDC181 localized to the manchette. During the final steps of male germ cell development, CCDC181 was concentrated in the sperm flagella (Supplementary Figure S1C), persisting along the entire sperm flagellum and accumulating at the midpiece of the cauda epididymis (Supplementary Figure S1D). These findings suggest that CCDC181 is necessary for spermatid elongation and sperm flagellum development.

Next, to investigate the conservation of CCDC181, its sequence and structural characteristics were analyzed. Orthologs of CCDC181 were obtained from various species, including mammals, reptiles, birds, amphibians, and fish. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA, which demonstrated that CCDC181 was evolutionarily conserved from bony fish to humans (Supplementary Figure S2A). Based on the NCBI Conserved Domain Database, only one potential functional domain of CCDC181 (amino acids 337–494) was predicted (Supplementary Figure S2B), while the functions of the remaining regions of the protein remained unknown. Using MEME, 10 conserved motifs were identified in CCDC181 across 12 species, showing high pairwise similarities (Supplementary Figure S2C). Previous findings have suggested that a region of murine CCDC181 (amino acids 393–448) interacts with HOOK1 (Schwarz et al., 2017). Notably, motif 6 (amino acids 404–444), corresponding to the interacting region, is highly conserved among species. Overall, CCDC181 exhibits high conservation in vertebrates, implying that its function may be similarly conserved across these species.

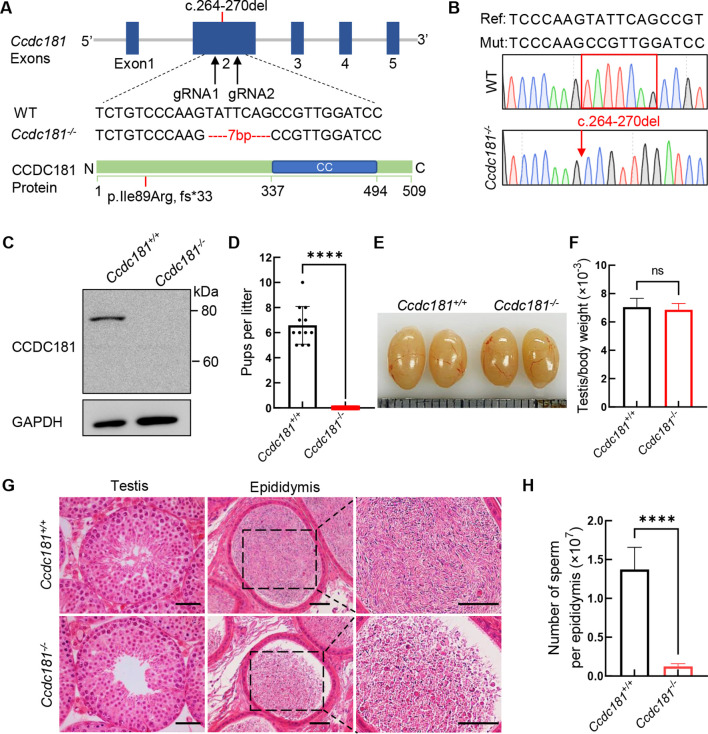

Ccdc181 knockout leads to male infertility

To elucidate the role of CCDC181 during spermiogenesis, Ccdc181 knockout mice were generated using CRISPR/Cas9. The mutation did not affect Ccdc181 transcription (Supplementary Figure S3). Sanger sequencing of cDNA from mutant mice revealed a 7 bp deletion (c.264_270del) in exon 2 of Ccdc181, leading to premature termination of translation (p. Ile89Arg, fs*33) (Figure 1A, B). The absence of the full-length CCDC181 protein in the mutant testes confirmed the successful generation of Ccdc181−/− mice (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Generation and reproduction of Ccdc181 knockout mice

A: Schematic of generation of Ccdc181−/− mice using CRISPR/Cas9. The gRNAs were designed to target exon 2 of the Ccdc181, and a mouse line with a 7 bp deletion was obtained. Illustration of CCDC181 protein structure shows mutation position. CC, coiled-coil domain. B: cDNA sequencing chromatograms verified the homozygous c.264_270del mutation in Ccdc181−/− mice. C: CCDC181 protein was depleted in testis of Ccdc181−/− mice. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Image is representative of three experiments. D: Ccdc181−/− male mice were infertile (n=5). ****: P<0.0001 by Student’s t-test. E: Testis size and weight were comparable between Ccdc181+/+ (left) and Ccdc181−/− mice (right) at 2 months of age. F: Testes from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice showed no obvious differences in weight (n=5). ns: Not significant by Student’s t-test. G: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of testis and cauda epididymis sections from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. H: Sperm counts per epididymis in Ccdc181−/− mice were markedly reduced compared with those in control mice (n=5). ****: P<0.0001 by Student’s t-test.

Subsequent fertility assessments of Ccdc181 knockout mice indicated that male mice lacking CCDC181 exhibited normal mounting behaviors and produced coital plugs but failed to produce offspring when mated with WT female mice (Figure 1D). In contrast, Ccdc181−/− female mice produced normal-sized litters when mated with WT males. Thus, the disruption of Ccdc181 specifically resulted in male infertility without affecting female fertility. To determine the cause of male infertility, adult Ccdc181−/− testes were grossly and histologically examined. Ccdc181−/− mice showed normal growth and development, with testicular sizes and testis/body weight ratios comparable to those of Ccdc181+/+ mice (Figure 1E, F). However, sperm counts from the cauda epididymis were markedly reduced in Ccdc181−/− mice (Figure 1G, H).

Although CCDC181 was detected in motile cilia (Schwarz et al., 2017), homozygous-null mice did not display any obvious signs of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Examination of lung and tracheal cilia in Ccdc181−/− mice revealed structures similar to those in Ccdc181+/+ mice (Supplementary Figure S4), indicating a specific requirement for CCDC181 in spermatogenesis.

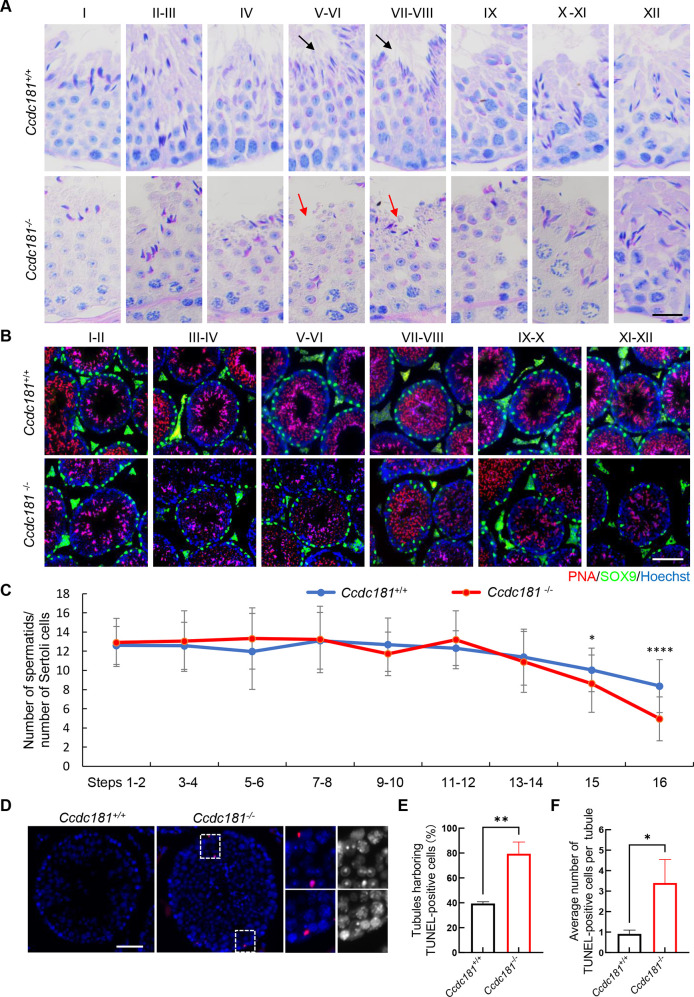

Increased loss and apoptosis of late spermatids in Ccdc181−/− mice

To investigate the causes of reduced sperm counts in Ccdc181−/− mice, Periodic Acid-Schiff staining was employed to compare the seminiferous tubules of Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice at various stages. Compared to Ccdc181+/+ mice, there was a marked decrease in the number of elongating and elongated spermatids within the seminiferous tubules of Ccdc181−/− mice. Histological analysis revealed a significant decrease in the number of elongated spermatids at steps 15 and 16 (stages V–VIII) in the seminiferous tubules of Ccdc181−/− mice, indicating abnormalities during spermiogenesis (Figure 2A). Additionally, spermatids and Sertoli cells were labeled by immunofluorescence staining with peanut agglutinin and anti-SRY-Box transcription factor 9, markers of acrosomes and Sertoli cells, respectively (Figure 2B). Analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in the ratios of spermatids to Sertoli cells from steps 15 to 16 in Ccdc181−/− mice (Figure 2C). Specifically, the number of step 16 spermatids was markedly decreased in Ccdc181−/− mice compared to Ccdc181+/+ mice. To determine whether the elimination of late spermatids was associated with apoptosis, a TUNEL assay was conducted on testicular sections (Figure 2D). The assay showed an overall increase in the proportion of seminiferous tubules containing TUNEL-positive cells and a higher average number of apoptotic cells per tubule in Ccdc181−/− testis sections compared to controls (Figure 2E, F). These findings suggest that defective late spermatids in Ccdc181−/− mice undergo apoptosis, leading to a significant decline in sperm counts in the epididymis.

Figure 2.

CCDC181 deficiency causes a significant decrease in elongated spermatids

A: Periodic acid-Schiff staining of testis sections from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Black arrows indicate normal spermatid counts in stage V–VIII seminiferous tubules of Ccdc181+/+ mice, red arrows indicate decrease of spermatids in Ccdc181−/− mice. Scale bar=20 µm. B: Representative images of testis sections from Ccdc181−/− and Ccdc181+/+ mice co-stained with peanut agglutinin (PNA, red) and anti- SRY-Box transcription factor 9 (SOX9, marker of Sertoli cells, green). Scale bar: 100 µm. C: Statistical analysis of the ratio of spermatids to Sertoli cells during spermiogenesis. A significant decrease in step 15 to 16 spermatids occurred in Ccdc181−/− mice during the final phase of spermiogenesis. n=3. *: P<0.05; ****: P<0.0001 by Student’s t-test. D: TUNEL assay of testicular sections from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Red signals indicate apoptotic spermatids. Boxed regions are magnified to the right. Scale bar: 100 µm. E, F: Frequencies of TUNEL-positive tubules and average number of TUNEL-positive cells per tubule in Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Data are mean±SEM, n=3. *: P<0.05; **: P<0.01 by Student’s t-test.

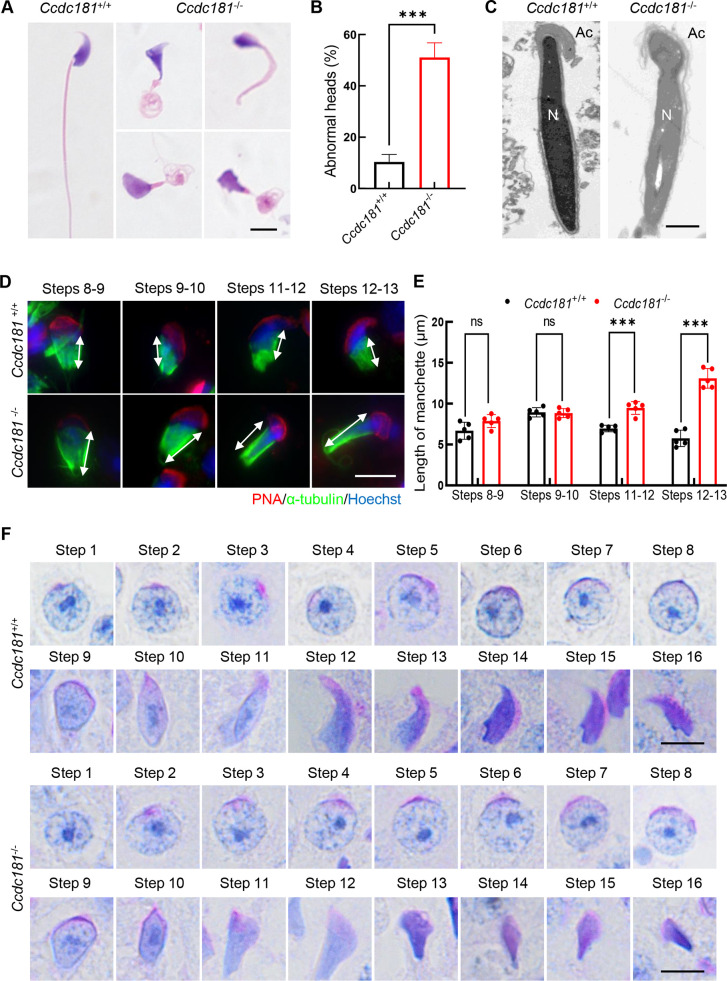

CCDC181 deficiency leads to abnormal manchette and acrosome detachment

To further investigate the defects in spermatogenesis in Ccdc181−/− mice, H&E staining was performed on semen smears from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Results indicated that 50% of the spermatozoa in the cauda epididymis of Ccdc181−/− mice exhibited abnormal head shapes (Figure 3A, B), as confirmed by TEM (Figure 3C). Abnormal sperm head morphology is often associated with defects in acrosome and manchette formation (de Boer et al., 2015). Therefore, the acrosome structure and manchette formation during spermiogenesis were examined in Ccdc181−/− mice.

Figure 3.

CCDC181 deficiency impairs manchette formation and sperm head shaping

A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of spermatozoa from cauda epididymis of Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Abnormal sperm heads were observed in Ccdc181−/− mice. Scale bar: 5 µm. B: Percentage of abnormal sperm heads in Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice (n=3). At least 200 spermatozoa were examined per mouse. ***: P<0.001 by Student’s t-test. C: Representative TEM micrographs of sperm heads from cauda epididymis of Ccdc181−/− and Ccdc181+/+ mice. N, nucleus; Ac, acrosome. Scale bar: 1 µm. D: Abnormal manchette elongation in Ccdc181−/− spermatids. Spermatids from step 8 to 13 in Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice were co-stained with peanut agglutinin (PNA, red) and anti-α-tubulin (green) antibodies to observe elongation of manchette structures. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. Manchette structures are noted by double-head arrows. Scale bar: 10 µm. E: Statistical analysis of manchette length from steps 8 to 13. Red columns indicate manchette length of Ccdc181−/− spermatids in different steps, while black columns indicate manchette length of Ccdc181+/+ spermatids (n=5). ns: Not significant; ***: P<0.001 by Student’s t-test. F: Periodic acid-Schiff staining of spermatids at different steps in Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Scale bar: 5 µm.

TEM and immunofluorescence analyses were used to evaluate the acrosomal morphologies in Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. The elongated nucleus of Ccdc181+/+ sperm was tightly covered with a cap-like acrosome, whereas Ccdc181−/− sperm exhibited detachment of the acrosome from the nucleus (Supplementary Figure S5A). Peanut agglutinin staining showed that sperm from Ccdc181−/− mice had more absent or aberrant acrosomes compared to Ccdc181+/+ mice (Supplementary Figure S5B, C). Thus, these findings suggest that CCDC181 deficiency may lead to acrosome detachment. The acroplaxome, consisting of a filamentous actin (F-actin) and keratin-containing plate, is thought to anchor the acrosome to the nucleus during sperm head shaping (Kierszenbaum et al., 2003). Distribution of the acroplaxome was disturbed in Ccdc181−/− mice, showing detached, irregular, and fragmented F-actin distribution (Supplementary Figure S5D). These findings indicate that CCDC181 deficiency causes significant loosening of the acroplaxome structure and acrosome detachment in spermatids.

Manchette abnormalities are closely related to failures in sperm head shaping. The manchette emerges in step 8 spermatids, coinciding with the initiation of sperm nucleus elongation, and disintegrates at steps 13 to 14 when nuclear remodeling is complete. Immunofluorescence staining for α-tubulin and peanut agglutinin showed normal manchette formation in step 8 to 10 spermatids in Ccdc181−/− mice. However, Ccdc181−/− mice displayed significantly longer manchettes compared to controls in step 11 to 13 spermatids (Figure 3D, E). This defective manchette formation led to the presence of abnormal spermatid heads. During steps 11 to 13, Ccdc181−/− spermatids displayed an abnormal club-shaped head morphology, while Ccdc181+/+ spermatids displayed normal hook-shaped heads, as confirmed by Periodic Acid-Schiff staining (Figure 3F). These findings indicate that the absence of CCDC181 leads to acrosome detachment and impaired manchette formation, resulting in severe defects in sperm head shaping.

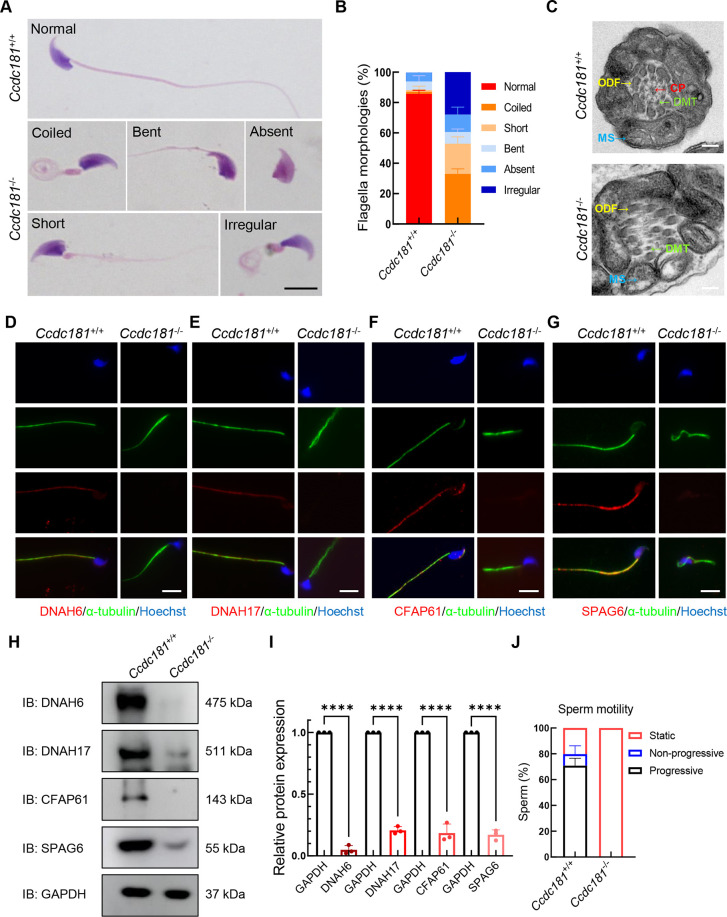

Ccdc181 knockout results in typical MMAF phenotype in male mice

In addition to abnormal head morphology, H&E staining of semen smears revealed that spermatozoa from the cauda epididymis of Ccdc181−/− mice displayed malformed flagella, including coiled, short, bent, absent, and irregular forms, which are typical features of MMAF (Figure 4A, B). Further TEM analysis indicated that the axoneme structure in Ccdc181−/− sperm flagella was severely disorganized, suggesting significant impairment of the ultrastructure (Figure 4C). To validate these findings, immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine several structural components of the flagella, such as DNAH6, DNAH17, CFAP61, and SPAG6, representing the inner dynein arms, outer dynein arms, radial spokes, and central pairs, respectively. Compared to the continuous signals along the entire flagella of Ccdc181+/+ sperm, the signals of DNAH6, DNAH17, CFAP61, and SPAG6 were absent in Ccdc181−/− sperm flagella (Figure 4D–G). Protein levels of these components were also dramatically reduced in Ccdc181−/− sperm (Figure 4H, I). Computer-assisted semen analysis demonstrated markedly decreased motility in Ccdc181−/− sperm (Figure 4J), likely due to the abnormal morphologies and structures of their flagella. Thus, deletion of Ccdc181 induces severe defects in sperm flagellum biogenesis, ultimately leading to a typical MMAF phenotype.

Figure 4.

CCDC181 deficiency results in typical multiple morphological abnormalities of flagella phenotype in male mice

A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of sperm flagella in Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. Sperm showed coiled, bent, absent, short, and irregular flagella in Ccdc181−/− mice. Scale bar: 10 µm. B: Frequencies of morphologically coiled, bent, absent, short, and irregular sperm flagella. Each spermatozoon was classified as having only one type of flagellar morphology according to its major abnormality (n=5). At least 200 spermatozoa were examined per mouse. C: Representative TEM micrographs showing cross-sections of sperm flagella from Ccdc181−/− and Ccdc181+/+ mice. CP, central pair of microtubules (red arrow); DMT, doublets of microtubules (green arrow); ODF, outer dense fiber (yellow arrow); MS, mitochondrial sheath (blue arrow). Scale bar: 200 nm. D–G: Representative images of spermatozoa from Ccdc181−/− and Ccdc181+/+ mice co-stained with anti-α-tubulin, anti-DNAH6 (D) or anti-DNAH17 (E), anti-CFAP61 (F), and anti-SPAG6 antibodies (G), representing inner dynein arms, outer dynein arms, radial spokes and central pairs, respectively. Scale bar: 10 µm. H: Western blotting of DNAH6, DNAH17, CFAP61, and SPAG6 protein levels in sperm lysates from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice. GAPDH served as a loading control. DNAH6, DNAH17, CFAP61, and SPAG6 protein levels were reduced in Ccdc181−/− sperm compared to Ccdc181+/+ sperm. I: Quantitative results of western blotting. Protein levels were normalized against GAPDH levels. Data are mean±SEM. ****: P<0.0001 by Student’s t-test. J: Sperm motility was markedly reduced in Ccdc181−/− mice compared to that in control mice (n=3).

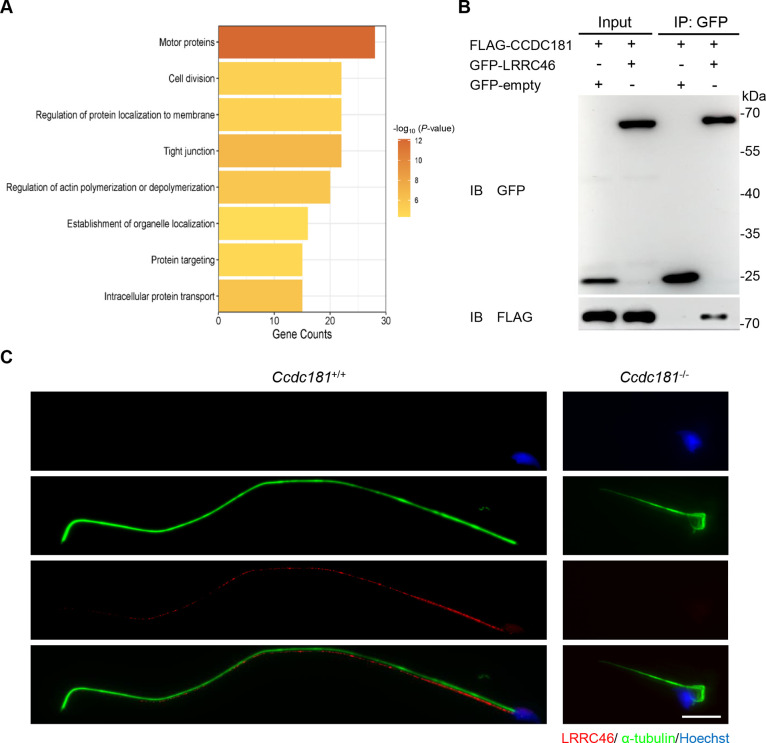

CCDC181 is required for LRRC46 localization along flagella

To further investigate the role of CCDC181 during spermatogenesis, anti-CCDC181 immunoprecipitation coupled with quantitative mass spectrometry was performed on testicular lysates from Ccdc181+/+ mice. A total of 1 934 proteins were quantified, including 113 CCDC181-associated proteins (IP/IgG>1.5-fold and IP-IgG>3). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of these proteins revealed significant enrichment in terms related to intracellular protein transport and motor proteins (Figure 5A). These findings are consistent with the above results on defective intramanchette transport and decreased motility in Ccdc181−/− mouse sperm. Among the candidate interacting proteins, 11 were initially screened based on their function and localization (Supplementary Table S1). LRRC46 was particularly noteworthy, as it has been linked to male infertility and MMAF phenotypes (Yin et al., 2022). The phenotypes of Lrrc46 knockout mice closely resemble those observed in Ccdc181−/− mice, suggesting that LRRC46 and CCDC181 function within the same pathway. Therefore, we hypothesized that CCDC181 interacts with LRRC46. Despite the specificity and sensitivity limitations of the anti-CCDC181 and anti-LRRC46 antibodies, co-IP assays of testicular lysates did not detect the interaction (Supplementary Figure S6A, B). However, the interaction between CCDC181 (fused with a FLAG tag) and LRRC46 (fused with a GFP tag) was successfully confirmed in HEK293T cells, with GFP-empty serving as a negative control (Figure 5B; Supplementary Figure S6C). To determine whether CCDC181 deficiency impacts LRRC46 function, immunofluorescence analysis was conducted, which showed that the LRRC46 signals were severely disrupted in Ccdc181−/− mouse sperm (Figure 5C). These results suggest that CCDC181 interacts with LRRC46 and is essential for the proper localization of LRRC46.

Figure 5.

LRRC46 interacts with CCDC181 and its localization along flagella is dependent on CCDC181

A: GO analysis of most enriched CCDC181-associated proteins identified in adult mouse testes, ranked by gene counts. Only proteins with IP/IgG>1.5-fold and IP-IgG>3 were considered CCDC181-associated proteins. B: Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay showed that CCDC181 interacts with LRRC46, with GFP-empty serving as a relevant negative control. M, mouse. C: Representative images of spermatozoa from Ccdc181+/+ and Ccdc181−/− mice co-stained with anti-α-tubulin (green) and anti-LRRC46 (red) antibodies. Scale bar: 10 µm.

DISCUSSION

Although MMAF is considered the most severe form of asthenoteratozoospermia, its genetic underpinnings remain unclear. It is well-documented that many CCDC family proteins are essential for the proper development and function of spermatozoa (Becker-Heck et al., 2011; Blanchon et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2021; Ge et al., 2024; Geng et al., 2016; Jreijiri et al., 2024; Kaczmarek et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2024; Sha et al., 2019; Tapia Contreras & Hoyer-Fender, 2019; Wang et al., 2018, 2023, 2024; Yamaguchi et al., 2014; Young et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022a). This study is the first to elucidate the effects of CCDC181 deficiency on spermatogenesis. CCDC181 showed dynamic localizations in adult mouse testes during spermiogenesis (Figure 6). Knockout of Ccdc181 resulted in a typical MMAF phenotype in male mice, primarily presenting with coiled, curved, short, or absent flagella and complete sperm immobility (Supplementary Figure S7). Furthermore, CCDC181 was implicated in manchette formation and sperm head shaping. LRRC46, an MMAF-related protein (Yin et al., 2022), was identified as an interacting protein of CCDC181 based on immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry analysis. These findings suggest that CCDC181 is essential for spermatogenesis and male fertility in mice, potentially playing a role in human male infertility.

Figure 6.

Schematic showing localization of CCDC181 protein

Dynamic localization of CCDC181 protein in adult mouse testes during spermiogenesis, based on immunofluorescence staining results.

During spermiogenesis, targeted protein trafficking to specific cellular regions is crucial for sperm development (Teves et al., 2020). The manchette, composed of microtubules and actin filaments, assists with nuclear remodeling and participates in protein trafficking via intramanchette transport (O'Donnell & O'Bryan, 2014). HOOK1, involved in vesicle cargo transport, is sequentially localized from the acroplaxome to the manchette and the head-tail coupling apparatus (Kierszenbaum et al., 2011). Loss of HOOK1 function disrupts the connection between the manchette and nuclear envelope, leading to abnormal microtubule positioning and sperm head shape (Mendoza-Lujambio et al., 2002). The cargo-specific binding properties of HOOK1 and its ability to bind to motor proteins facilitate the transport of cargos toward specific locations within the elongating spermatids (Maldonado-Báez et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown an interaction between HOOK1 and CCDC181, suggesting HOOK1 as a carrier for CCDC181 transport (Schwarz et al., 2017). It has been hypothesized that CCDC181 does not directly bind to the manchette microtubules but is linked via HOOK1 for intramanchette transport to the axoneme of developing sperm flagella. Our study found that CCDC181 was localized to the manchette in spermatids from steps 8 to 14. Ccdc181−/− mice displayed markedly longer manchettes in step 11 spermatids and abnormal club-shaped head morphology compared to the controls. These observations indicate that CCDC181 may facilitate protein transport from the Golgi complex to the sperm tail through the manchette and function via its interaction with HOOK1.

Several proteins have been identified that bridge the acrosome and nucleus via acroplaxome-manchette structures, playing an important role in anchoring the acrosome to the nucleus (Kazarian et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2015; Mendoza-Lujambio et al., 2002; O'Donnell et al., 2012). The acroplaxome attaches the developing acrosome to the nucleus during sperm head shaping (Kierszenbaum et al., 2003). This connection is established through the marginal or perinuclear ring, both of which are involved in sperm head shaping (Kierszenbaum & Tres, 2004). The perinuclear ring assembles adjacent to the marginal ring of the acroplaxome. Both HOOK1 and CCDC181 have been observed to localize in the nuclear ring between the manchette and nucleus (Mendoza-Lujambio et al., 2002; Schwarz et al., 2017), suggesting that their interaction may occur at this site. Our findings indicated that CCDC181 deficiency impaired sperm head shaping and induced acrosome detachment.

CCDC181 may also play a role in flagellum protein transport. Immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry and co-IP indicated that CCDC181 interacted with the MMAF-related protein LRRC46. LRRC46 is specifically expressed in the testes of adult mice, with its knockout resulting in typical MMAF phenotypes and severe axonemal disorganization, similar to those observed in Ccdc181−/− mice (Yin et al., 2022). Both the CCDC181 and LRRC46 proteins accumulate at the midpiece of the spermatozoon tail (Yin et al., 2022). Immunofluorescence results demonstrated a deficiency in LRRC46 signals along the flagella of Ccdc181−/− mice, indicating that CCDC181 is essential for the proper localization of LRRC46. These findings indicate that CCDC181 and LRRC46 function in a common pathway during spermiogenesis, with their interaction likely occurring at the midpiece.

Although CCDC181 is localized on motile cilia (Schwarz et al., 2017), our mutant mice did not exhibit primary ciliary dyskinesia. Previous studies have shown that sperm flagellar damage is often more severe than ciliary damage following mutations in certain genes (Zhang et al., 2021a, 2022b). This suggests that CCDC181 may play a more critical role in sperm flagella compared to respiratory cilia. Additionally, the distinct phenotypes observed may be due to different mechanisms of axonemal assembly between sperm flagella and respiratory cilia.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that CCDC181 is essential for the assembly of sperm tails during spermatogenesis and contributes to sperm head shaping. These findings highlight the potential roles of CCDC181 in both sperm flagellum biogenesis and manchette formation. Given that CCDC181 is an evolutionarily conserved component of the flagellar proteome across diverse species, mutations in CCDC181 could potentially be present in infertile patients with MMAF. Thus, further studies are needed to determine whether and how CCDC181 mutations affect disease presentation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.

Acknowledgments

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Q.H.S. and L.M.W. designed and supervised the study. X.J.Z. and X.N.H. performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. Q.H.S., L.M.W., B.L.S., X.H.J., and B.X. revised the manuscript. J.T.Z., J.W.Y., and M.L.Y. analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all participants for their cooperation. We thank Professor Hong-Bin Liu (Shandong University, China) for sharing antibodies. We thank Li Wang at the Center of Cryo-Electron Microscopy, Zhejiang University, for technical assistance with TEM. We also thank the Bioinformatics Center of the USTC, School of Life Sciences, for providing supercomputing resources, and the Laboratory Animal Center of the University of Science and Technology of China.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071709, 81971446, 82171599, 82374212), Global Select Project (DJK-LX-2022010) of the Institute of Health and Medicine, Hefei Comprehensive National Science Center, and Joint Fund for New Medicine of USTC (YD9100002034)

Contributor Information

Li-Min Wu, Email: wlm@ustc.edu.cn.

Qing-Hua Shi, Email: qshi@ustc.edu.cn.

References

- Barratt CLR, Björndahl L, De Jonge CJ, et al The diagnosis of male infertility: an analysis of the evidence to support the development of global WHO guidance-challenges and future research opportunities. Human Reproduction Update. 2017;23(6):660–680. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Heck A, Zohn IE, Okabe N, et al The coiled-coil domain containing protein CCDC40 is essential for motile cilia function and left-right axis formation. Nature Genetics. 2011;43(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchon S, Legendre M, Copin B, et al Delineation of CCDC39/CCDC40 mutation spectrum and associated phenotypes in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2012;49(6):410–416. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DJ, Liang Y, Li J, et al A novel CCDC39 mutation causes multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella in a primary ciliary dyskinesia patient. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2021;43(5):920–930. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer P, de Vries M, Ramos L A mutation study of sperm head shape and motility in the mouse: lessons for the clinic. Andrology. 2015;3(2):174–202. doi: 10.1111/andr.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Khan R, Yu CP, et al The testis-specific LINC component SUN3 is essential for sperm head shaping during mouse spermiogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2020;295(19):6289–6298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.012375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge TT, Yuan L, Xu LW, et al Coiled-coil domain containing 159 is required for spermatid head and tail assembly in mice. Biology of Reproduction. 2024;110(5):877–894. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioae012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Q, Ni LW, Ouyang B, et al A novel testis-specific gene, Ccdc136, is required for acrosome formation and fertilization in mice. Reproductive Sciences. 2016;23(10):1387–1396. doi: 10.1177/1933719116641762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CJ, Abbas T, Muhammad Z, et al A homozygous loss-of-function mutation in MSH5 abolishes MutSγ axial loading and causes meiotic arrest in NOA-affected individuals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(12):6522. doi: 10.3390/ijms23126522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jreijiri F, Cavarocchi E, Amiri-Yekta A, et al CCDC65, encoding a component of the axonemal Nexin-Dynein regulatory complex, is required for sperm flagellum structure in humans. Clinical Genetics. 2024;105(3):317–322. doi: 10.1111/cge.14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek K, Niedzialkowska E, Studencka M, et al Ccdc33, a predominantly testis-expressed gene, encodes a putative peroxisomal protein. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2009;126(3):243–252. doi: 10.1159/000251961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazarian E, Son H, Sapao P, et al SPAG17 is required for male germ cell differentiation and fertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(4):1252. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum AL, Rivkin E, Tres LL Acroplaxome, an F-actin-keratin-containing plate, anchors the acrosome to the nucleus during shaping of the spermatid head. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2003;14(11):4628–4640. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-04-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum AL, Rivkin E, Tres LL Cytoskeletal track selection during cargo transport in spermatids is relevant to male fertility. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1(3):221–230. doi: 10.4161/spmg.1.3.18018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL The acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex and the shaping of the spermatid head. Archives of Histology and Cytology. 2004;67(4):271–284. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehti MS, Sironen A Formation and function of the manchette and flagellum during spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2016;151(4):R43–R54. doi: 10.1530/REP-15-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Li CL, Lin SR, et al A nonsense mutation in Ccdc62 gene is responsible for spermiogenesis defects and male infertility in repro29/repro29 mice. Biology of Reproduction. 2017;96(3):587–597. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.141408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JY, Rahim F, Zhou JT, et al Loss-of-function variants in KCTD19 cause non-obstructive azoospermia in humans. iScience. 2023;26(7):107193. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Wang YW, Zhang H, et al Computationally predicted pathogenic USP9X mutation identified in infertile men does not affect spermatogenesis in mice. Zoological Research. 2022;42(2):225–228. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2021.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, DeBoer K, de Kretser DM, et al LRGUK-1 is required for basal body and manchette function during spermatogenesis and male fertility. PLoS Genetics. 2015;11(3):e1005090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma A, Zeb A, Ali I, et al Biallelic variants in CFAP61 cause multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella and male infertility. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2022;9:803818. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.803818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma A, Zhou JT, Ali H, et al Loss-of-function mutations in CFAP57 cause multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella in humans and mice. JCI Insight. 2023;8(3):e166869. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.166869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Zhang BB, Khan A, et al Novel frameshift mutation in STK33 is associated with asthenozoospermia and multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella. Human Molecular Genetics. 2021;30(21):1977–1984. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YJ, Wu BB, Chen YH, et al CCDC146 is required for sperm flagellum biogenesis and male fertility in mice. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2024;81(1):1. doi: 10.1007/s00018-023-05025-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Báez L, Cole NB, Krämer H, et al Microtubule-dependent endosomal sorting of clathrin-independent cargo by Hook1. Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;201(2):233–247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201208172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Lujambio I, Burfeind P, Dixkens C, et al The Hook1 gene is non-functional in the abnormal spermatozoon head shape (azh) mutant mouse. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11(14):1647–1658. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.14.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Katoh Y Architecture of the IFT ciliary trafficking machinery and interplay between its components. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2020;55(2):179–196. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2020.1768206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, O'Bryan MK Microtubules and spermatogenesis. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2014;30:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, Rhodes D, Smith SJ, et al An essential role for katanin p80 and microtubule severing in male gamete production. PLoS Genetics. 2012;8(5):e1002698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz T, Prieler B, Schmid JA, et al Ccdc181 is a microtubule-binding protein that interacts with Hook1 in haploid male germ cells and localizes to the sperm tail and motile cilia. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2017;96(3):276–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha YW, Xu YK, Wei XL, et al CCDC9 is identified as a novel candidate gene of severe asthenozoospermia. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine. 2019;65(6):465–473. doi: 10.1080/19396368.2019.1655812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi BL, Shah W, Liu L, et al Biallelic mutations in RNA-binding protein ADAD2 cause spermiogenic failure and non-obstructive azoospermia in humans. Human Reproduction Open. 2023;2023(3):hoad022. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoad022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia Contreras C, Hoyer-Fender S CCDC42 localizes to manchette, HTCA and tail and interacts with ODF1 and ODF2 in the formation of the male germ cell cytoskeleton. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2019;7:151. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teves M, Roldan E, Krapf D, et al Sperm differentiation: the role of trafficking of proteins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(10):3702. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touré A, Martinez G, Kherraf ZE, et al The genetic architecture of morphological abnormalities of the sperm tail. Human Genetics. 2021;140(1):21–42. doi: 10.1007/s00439-020-02113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MY, Kang JY, Shen ZM, et al CCDC189 affects sperm flagellum formation by interacting with CABCOCO1. National Science Review. 2023;10(9):nwad181. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwad181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TT, Yin QQ, Ma XH, et al Ccdc87 is critical for sperm function and male fertility. Biology of Reproduction. 2018;99(4):817–827. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Huang XY, Sun GY, et al Coiled-coil domain-containing 38 is required for acrosome biogenesis and fibrous sheath assembly in mice. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2024;51(4):407–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2023.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie XF, Murtaza G, Li Y, et al Biallelic HFM1 variants cause non-obstructive azoospermia with meiotic arrest in humans by impairing crossover formation to varying degrees. Human Reproduction. 2022;37(7):1664–1677. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deac092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JZ, Gao JN, Liu JY, et al ZFP541 maintains the repression of pre-pachytene transcriptional programs and promotes male meiosis progression. Cell Reports. 2022;38(12):110540. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A, Kaneko T, Inai T, et al Molecular cloning and subcellular localization of Tektin2-binding protein 1 (Ccdc 172) in rat spermatozoa. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 2014;62(4):286–297. doi: 10.1369/0022155413520607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin YY, Mu WY, Yu XC, et al LRRC46 accumulates at the midpiece of sperm flagella and is essential for spermiogenesis and male fertility in mouse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(15):8525. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SAM, Miyata H, Satouh Y, et al CRISPR/Cas9-mediated rapid generation of multiple mouse lines identified Ccdc63 as essential for spermiogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16(10):24732–24750. doi: 10.3390/ijms161024732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BB, Ma H, Khan T, et al A DNAH17 missense variant causes flagella destabilization and asthenozoospermia. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2020;217(2):e20182365. doi: 10.1084/jem.20182365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JT, He XJ, Wu H, et al Loss of DRC1 function leads to multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella and male infertility in human and mouse. Human Molecular Genetics. 2021a;30(21):1996–2011. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RD, Wu BB, Liu C, et al CCDC38 is required for sperm flagellum biogenesis and male fertility in mice. Development. 2022a;149(11):dev200516. doi: 10.1242/dev.200516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Xiao Z, Zhang JT, et al Differential requirements of IQUB for the assembly of radial spoke 1 and the motility of mouse cilia and flagella. Cell Reports. 2022b;41(8):111683. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XX, Li M, Jiang XH, et al Nuclear translocation of MTL5 from cytoplasm requires its direct interaction with LIN9 and is essential for male meiosis and fertility. PLoS Genetics. 2021b;17(8):e1009753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.